Abstract

The hippocampus is involved in anxiety as well as spatial memory formation and is sexually dimorphic. Female rats typically show less anxiety in elevated plus maze procedure (EPM), a standard animal model of anxiety. Many intracellular proteins, including α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunit GluR1 and the cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB), in hippocampus contribute to memory formation. However, less is known about the roles for hippocampal GluR1 and CREB in anxiety. We examined behavior in EPM in male and female rats and obtained hippocampal tissue samples to determine levels of GluR1 and CREB with western blots. EPM results showed that female rats exhibited less anxiety-like behaviors than male rats. Further, behaviors in EPM were significantly correlated with hippocampal GluR1 levels, but not with CREB. Yet, both proteins showed sex differences with lower levels in female rats. These data not only suggest some potential bases for sex differences in behaviors to which the hippocampus contributes but demonstrate that there is a strong association between hippocampal GluR1 levels and anxiety as assessed with EPM.

Keywords: CREB, AMPA, anxiety, female, rat

1. Introduction1

The hippocampus is widely known for its importance in the formation and consolidation of spatial/relational memories and for its high degree of synaptic plasticity (McGaugh, 2000; Scoville and Milner, 1957). Hippocampal synaptic plasticity involves, in part, the calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) intracellular pathway and the signal-transducing enzyme protein kinase A (PKA). CaMKII phosphorylates α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunit GluR1. CaMKII and PKA regulate and phosphorylate the transcription factor cyclic-AMP response element binding protein (CREB) that is linked to synaptic plasticity in hippocampus (Guzowski and McGaugh, 1997; Kudo et al, 2004; Lonze and Ginty, 2002; Restivo et al, 2009; Silva et al, 1998; Viosca et al, 2009).

The hippocampus also contributes to anxiety (Barkus et al, 2010; Gray, 1982; McHugh et al, 2004). Anxiety-like behavior in rodents is assessed with elevated plus maze (EPM) (Pellow et al, 1985; Walf and Frye, 2007). Animals explore open and closed arms of a raised maze; increased time in open arms reflects decreased anxiety and vice versa. Although an extensive literature on anxiety and glutamate exists, it focuses on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) or metabotropic receptors (Barkus et al, 2010). Involvement of AMPA receptors, specifically GluR1 subunits, has been studied less and the data are contradictory. For example, GluR1 subunit deletion enhances anxiety (Bannerman et al, 2004; Mead et al, 2006) but other studies suggest the opposite (Alt et al, 2006; Das et al, 2008; Kapus et al, 2008). The relationship of CREB activation in hippocampus to anxiety is also unclear. CREB deletion enhances (Graves et al, 2002; Hebda-Bauer et al, 2004; Valverde et al, 2004) but CaMKIV deletion reduces anxiety (Shum et al, 2005). Increasing CREB reduces (Li et al, 2009), enhances (Rubino et al, 2008), or has no effect on anxiety (Restivo et al, 2009). To directly test the relationships of hippocampal GluR1 and CREB levels to anxiety, we examined EPM behavior and levels of these proteins in the same animals.

Sex differences are seen in anxiety. Females spend more time in open arms of EPM than male rats indicating they are less anxious (Ferguson and Gray, 2005; Johnston and File, 1990; Zimmerberg and Farley, 1993). However, no sex differences in EPM have been reported as well (Vaglenova et al, 2008). Ovarian hormones interact with illumination and affect EPM performance (Marcondes et al, 2001; Mora et al, 1996; Zimmerberg et al, 1993). Females show lower anxiety-like behavior during proestrus or metestrus (Marcondes et al, 2001; Mora et al, 1996) although this finding is not consistent across studies (Nomikos and Spyraki, 1988). Estrogen enhances hippocampal pCREB levels in rats of both sexes (Abraham and Herbison, 2005) but only males show CREB activation after context conditioning (Kudo et al, 2004). AMPA receptor density is lower in female vs. male hippocampus (Palomero-Gallagher et al, 2003). Estrogen increases hippocampal GluR1 levels in females (Waters et al, 2009) but does not affect AMPA receptors (Cyr et al, 2000; Weiland, 1992).

Previously, we found a trend for female vs male rats to show lower GluR1 protein levels in hippocampal dendritic fields although we saw no sex differences in inhibitory avoidance or object recognition memory (Kosten et al, 2007). The purpose of the present study is to test whether hippocampal levels of GluR1 and CREB are lower in female vs. male rats and to extend our prior behavioral tests to EPM. We examined EPM under low illumination during diestrus in females to minimize potential circulating ovarian hormone effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects and setting

Adult (70–90 days) male (n=11) and female (n=10) rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were used in the elevated plus maze (EPM) experiment. Brain tissue samples were obtained from 9 male and 8 female rats of the original group of 21 rats. Rats were group-housed (2–3 per cage) in polypropylene cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room maintained on a 12:12 light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00). Food and water were available ad libitum. Protocols were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No.85-23, revised 1996).

2.2 Vaginal cytology characterization

Estrous cycle phase was determined by vaginal cytology performed in the early afternoon as described previously (Kosten et al, 2005). Once the female exhibited at least two regular 4-day cycles, she was monitored for the diestrus stage, the stage during which testing was conducted. We chose the diestrus stage of the estrous cycle to standarize the effects of ovarian hormones on behaviors and protein levels.

2.3 Elevated plus maze apparatus and testing procedure

The elevated plus maze (EPM) consisted of two open arms (45-cm long ×10-cm wide), two closed arms (45-cm long X 10-cm wide X 30-cm high), and a middle compartment (4-cm long X 4-cm wide) forming the shape of a plus. The EPM was elevated 50-cm above the ground. The floor of the EPM and the walls of the enclosed were made of black acrylic. Rats were habituated to the testing room for 30-min before testing and the room was under dim light, with no experimenter present in the room. Each rat was placed in the middle compartment (head facing an open arm) and allowed to freely explore the apparatus for 5-min. The apparatus was cleaned with disinfectant after each 5-min run. The movements of each rat were recorded by a digital video camera mounted at a height of 130-cm and connected to a computer. Data were analyzed by an automated software program (ANY-maze; Stoellting Co.; Wood Dale, IL) installed on the computer. We measured times spent (sec) in the open and closed arms of the EPM and as well as time spent in the center zone and total distance traveled.

2.4 Tissue preparation and procedure

Approximately 30-min after EPM testing, rats were decapitated and the left and right hippocampi were rapidly dissected in slices of 1.5-mm using a Rodent Brain Matrix (RBM-4000C, ASI Instruments, Warren, MI) then immediately placed on dry ice. Samples were stored at −80°C until they were process for western blot analysis. Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold equal EMSA buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPE, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, and the appropriate concentration of the following protease inhibitors: 10-µg/ml leupeptin, 0.1 M P-aminobenzamidine, 1-µg/ml pepstain, 1 mM PMSF and 5 mM DTT. Samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 X g for 30-min at 4°C. The supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Total protein was determined with BCA protein assay kit (BCA, Pierce Protein, Rockford, IL). Samples were diluted to equal protein concentration in sample loading buffer, boiled for 5-min at 98°C and loaded onto 7% Tris-HCL SDS-polyacrylamide gel (50% Glycerol 2.8=ml, H2O 2.85ml, 1.5 M Tris pH 8.8 2.55-ml,10% SDS 50-µl,40% A/B 1.75-ml,10% APS 37.5-µl, TEMED 3.75-µl). Thirty and 20-µg of total protein were loaded for GluR1 and CREB, respectively and gels run at 100 V. Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Bioscience, Sweden). Membranes were blocked in 5% TBS-T milk for 1-hr (TBS, Bio-Rad; Copenhagen, Denmark). Primary antibodies were diluted in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk, 1×TBS, 0.1% Tween 20 as follows: Anti-GluR1-NT (N-terminus), clone RH95 mouse mono-clone (Mill-pore, Temecula, CA) 1:500; anti-CREB (86B10) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) 1:1000; anti-β-actin (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) 1:10000. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4° C with gentle shaking. After three 5-min washes in TBS with 0.1% Tween 20, the blots were then incubated for 2-hrs at room temperature with goat anti-mouse (for GluR1 1:10000, CREB 1:2000; or β-actin 1:10000) secondary antibodies (Pierce Protein, Rockford, IL) in 1×TBS with 5% w/v nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20. Blots were washed again four times for 20-min in TBS-T. Immunodectection was accomplished by enhanced chemiluminescence using SuperSignal west Pico enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce). Membranes were then imaged using 100 Plus Film Processor (All-Pro Imaging Corp.,Melville, NY). Quantification of the bands was performed with UVP Vision Works LS image Acquisition and Analysis software (version 6.8). Background was subtracted from each band density reading then normalized with that of β-actin.

2.5 Data analysis

Data on times spent in the open and closed arms as well as in the center of the elevated plus maze (EPM) and total distance (m) traveled across the entire maze were analyzed using t-tests for independent samples to test for sex differences. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Data on densitometry units representing levels of GluR1 and CREB were analyzed using a 2 X 2 ANOVA representing the between group factor of Sex with repeated measures on Side (right vs. left hippocampus). Data obtained from the subset of rats tested in the EPM and examined for protein levels in hippocampus were analyzed with multiple regression in order to determine if the behavioral measures could be predicted by levels of GluR1 or CREB. Significant multiple regressions (P<0.05) were followed by tests on single correlations with these significance levels set at P<0.01 in order to accommodate the use of multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1 Behavior in Elevated Plus-Maze

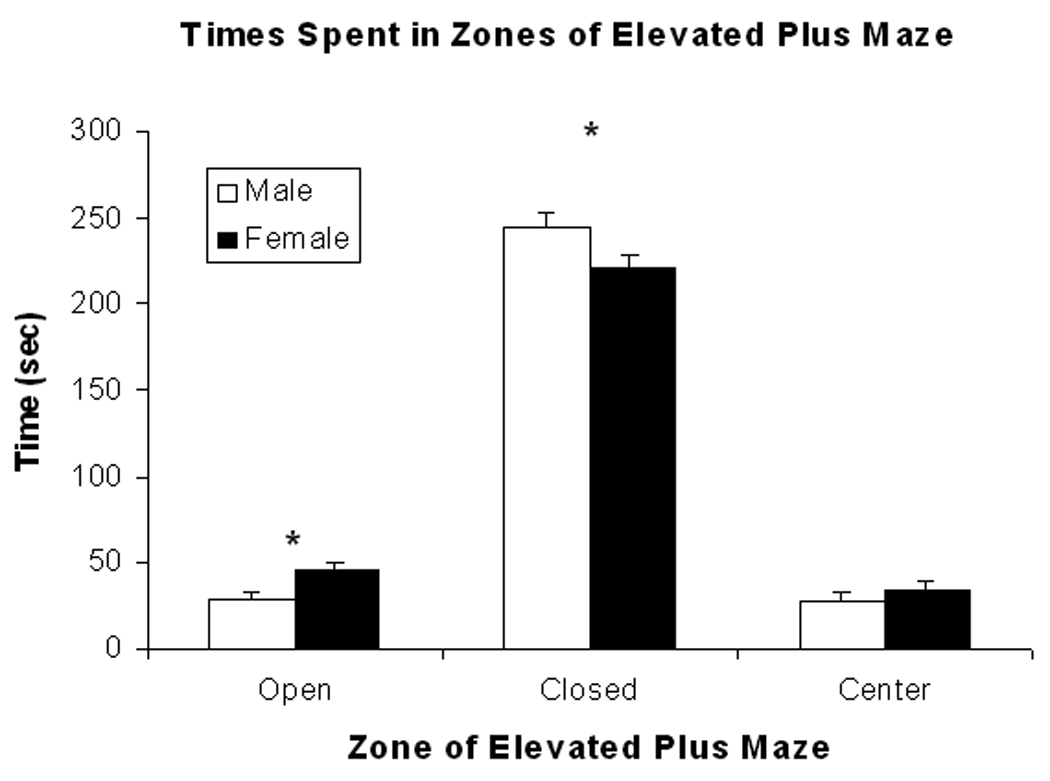

The amounts of time (sec) spent in the open and closed arms as well as in the center of the elevated plus maze (EPM) were determined for female and male rats. Both female and male rats spend more time in the closed arms than in the open arms of the maze as shown in Fig. 1. Female rats spend less time in the closed arms, t (19) = 2.18; P<0.05, and more time in the open arms, t (19) = 2.39; P<0.05, than male rats. Times spent in the center are low and do not show Sex differences (P>0.10). Total distance traveled (m) was greater in female rats (10.0 ± 0.6; Mean ± S.E.M.) compared to male rats (7.9 ± 0.7). This statement is supported by the significant Sex difference, t(15)=2.28; P<0.05.

Figure 1.

Mean (± S.E.M.) times (sec) spent in the open and closed arms as well as center zone of the elevated plus maze are shown for female (closed bars) and male (open bars) rats in the figure. Female rats spend more time in the open arm and less time in the closed arm than male rats but do not differ in time spent in the center zone. (see text for statistics). * represents significant sex differences.

3.2 Hippocampal GluR1 and CREB levels

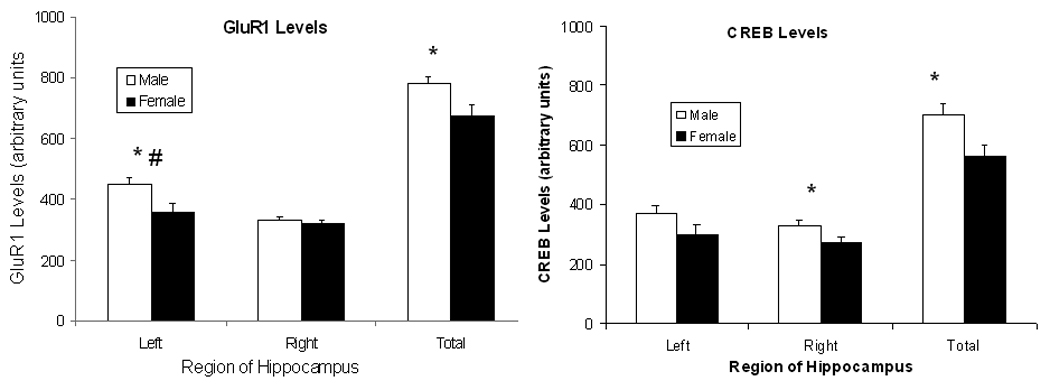

Total GluR1 levels in hippocampus are lower in female rats compared to male rats as supported by the significant main effect of Sex, F(1,15) = 7.39; P<0.02. These data are shown in the left panel of Fig. 2. GluR1 levels are higher in left hippocampus compared to right hippocampus as supported by the significant main effect of Side, F(1,15) = 12.08; P<0.005. The differential levels by side tend to be stronger for male rats as supported by the trend towards significance of the interaction of Sex X Side, F(1,15) = P<0.10. Post-hoc comparisons of sex differences in GluR1 levels by region show that GluR1 levels are lower in female vs. male rats in left hippocampus and in the total amounts for this brain region (P’s<0.05).

Figure 2.

Mean (± S.E.M.) arbitrary densitometry units reflecting GluR1 levels for left, right, and total hippocampus are shown for female (closed symbols) and male (open symbols) rats in the left figure. Mean (± S.E.M.) arbitrary densitometry units reflecting CREB levels for left, right, and total hippocampus are shown in the right figure. Female rats show lower GluR1 levels than male rats in the left hippocampus and in total hippocampus but do no differ in GluR1 levels in right hippocampus. There is also a trend for male, but not female rats, to have higher GluR1 levels in left vs. right hippocampus. Female rats show lower CREB levels than male rats in the right hippocampus and in total hippocampus but do no differ in CREB levels in left hippocampus (see text for statistics). * represents significant sex differences and # represents significant side differences for male rats.

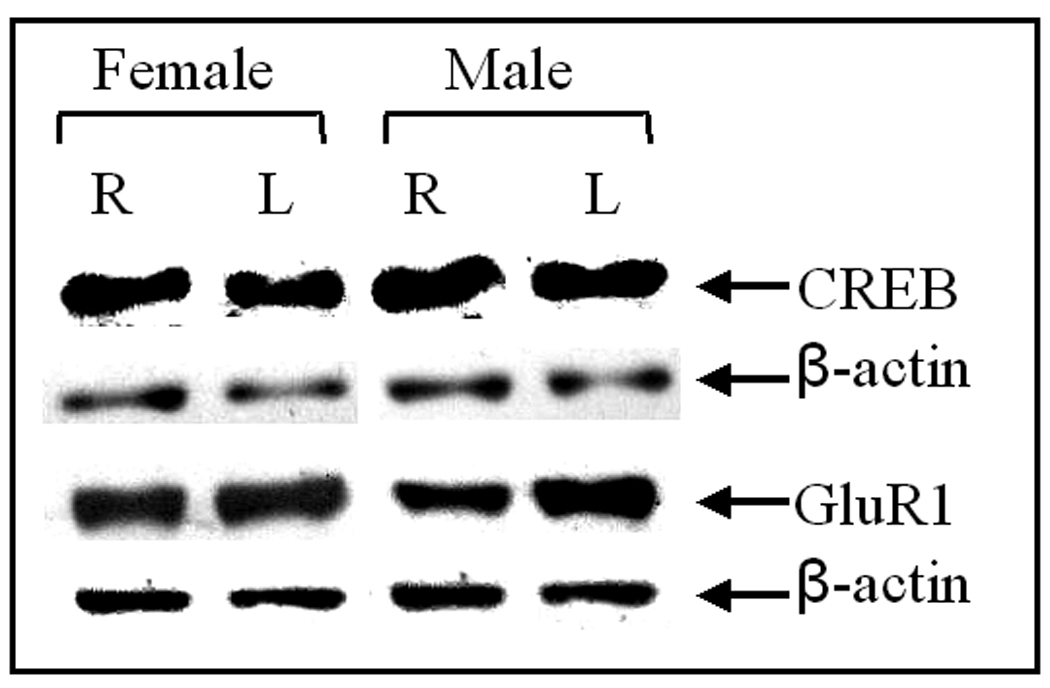

Total CREB levels in hippocampus are also lower in female rats compared to male rats as supported by the significant main effect of Sex, F(1,15) = 7.37; P<0.05. These data are shown in the right panel of Fig. 2. Unlike GluR1 levels, there is no difference in CREB levels between left and right hippocampus (P> 0.10). Post-hoc comparisons of sex differences in CREB levels by region show that CREB levels are lower in female vs. male rats in right hippocampus and in the total amounts for this brain region, P’s<0.05. As determined by two-way ANOVA, there were significant main effects of the factors Sex, F (1, 68) =9.50, P<0.01 and Side, F(1,68)=11.74, P<0.01. Representative blots for CREB and GluR1 as well as β-actin from right and left hippocampi of male and female rats are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Representative bands of GluR1 and CREB from right and left hippocampi of male and female rats are shown.

3.3 Correlations of behavior in EPM and hippocampal protein levels

Some female (n=8) and male (n=9) rats run in the EPM procedure were sacrificed to remove hippocampal tissue samples. For these rats, we examined the correlations (Pearson r) between times spent in the open and closed arms as well as in the center of the EPM with hippocampal protein levels and show these values in Table 1. The corresponding R2 values reflect the proportion of variability accounted for in the model and these are seen in Table 1. There are significant negative correlations between times spent in the open arms of the EPM with GluR1 levels in left hippocampus and with total GluR1hippocampal levels. That is, lower GluR1 levels are associated with a greater amount of time spent in the open arms. Significant positive correlations are shown for times spent in the closed arms of the maze with GluR1 levels in left hippocampus and total hippocampal GluR1levels. In these cases, lower GluR1 levels are associated with less time spent in the open arms. There are also significant negative correlations between GluR1 levels in left hippocampus and total hippocampal GluR1 levels with times spent in the center of the maze. These indicate lower GluR1 levels associate with greater times spent in the center. Multiple regression analysis with times spent in all three areas of the EPM and with total distance traveled were run and demonstrate that GluR1 levels in left hippocampus and total hippocampus are significantly associated with anxiety measures obtained from the EPM procedure as seen in Table 1. Overall, lower hippocampal GluR1 levels are significantly correlated with measures that reflect lower anxiety (i.e., less time in closed arms and greater time in open arms).

Table 1.

Correlations, (R2 values), and P values between GluR1 levels in left, right, and total hippocampus with times (sec) spent in zones of elevated plus maze.

| Side | Open Arm | Closed Arm | Center | Multiple Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | −0.62 (0.38); p<0.01 | 0.70 (0.49); p<0.005 | −0.48 (0.23); p<0.05 | 0.71 (0.50); p<0.01 |

| Right | −0.28 (0.08); n.s. | 0.25 (0.06); n.s. | 0.12 (0.01); n.s. | 0.28 (0.08); n.s |

| Total | −0.70 (0.49); p<0.005 | 0.76 (0.58); p<0.0005 | −0.51 (0.26); p<0.05 | 0.78 (0.61); p<0.005 |

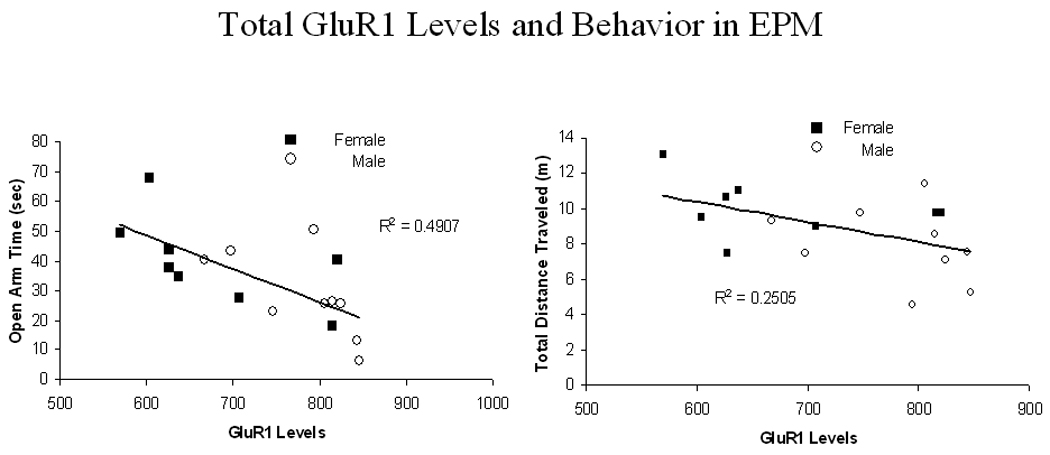

The relationship of total GluR1 levels to time spent in the open arms of the EPM is shown on the left side of Fig. 4 and to distance traveled on the right side of Fig. 4. The R2 values on the figure indicate that 49% of the variability in open arm is accounted for by a model of total GluR1 levels whereas a little over 25% of the variability in distance traveled is accounted for by total GluR1 levels. Note that these scatterplots indicate individual female and male rats. Correlations (and R2 values) between total distance traveled and hippocampal GluR1 levels are not significant for left or right hippocampus (P’s>0.05) but showed a significant negative correlation with total hippocampal GluR1 levels (r=−0.50; p<0.05). None of the EPM measures correlate significantly with CREB levels (P’s >0.10) as shown in Table 2.

Figure 4.

The correlation of time (min) spent in the open arm with total hippocampal levels of GluR1 is plotted in the left figure. The data show a significant negative association with an R2 greater than 0.49. The correlation of total distance traveled (m) with total hippocampal levels of GluR1 is plotted in the right figure. The data show a significant positive association with an R2 greater than 0.25. Closed symbols represent individual female rats and open symbols represent individual male rats.

Table 2.

Correlations and (R2 values) between levels of CREB in left, right, and total hippocampus with times (sec) spent in zones of elevated plus maze. None of these correlations was significant (P’s>0.10).

| Side | Open Arm | Closed Arm | Center |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left | −0.24 (0.06) | 0.07 (0.00) | 0.11 (0.01) |

| Right | −0.14 (0.02) | 0.24 (0.06) | −0.24 (0.06) |

| Total | −0.23 (0.05) | 0.16 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.00) |

Multiple regression for total hippocampal GluR1 levels with the variables of total distance traveled and times spent in the open and closed arms shows an adjusted R2 of 0.65. This model is significant, F(3,13)=10.90; P< 0.001, and indicates that 65% of the variability in total GluR1 levels is accounted for by this model. Multiple regression for GluR1 levels in left hippocampus with the same EPM variables shows and adjusted R2 of 0.57 which is significant, F(3,13)=5.66; P<0.05.

Separate analyses by sex demonstrate that GluR1 levels in left hippocampus are significantly associated with times in the closed arm and center zone for male rats (r’s=0.69 and −0.68 respectively; P’s<0.05) and that total hippocampal GluR1 levels are significantly associated with times in the closed arm for both male and female rats (r’s=0.78 and 0.72 respectively; P’s<0.05). Total distance traveled is not significantly associated with GluR1 levels for either sex (P’s>0.10).

4. Discussion

Results support our hypothesis that female rats had lower hippocampal GluR1 and CREB levels than male rats. Female rats also showed less anxiety-like behavior than male rats; they spent more time in open arms and less time in closed arms of the EPM compared to male rats. We now add to the limited literature linking GluR1 or CREB to anxiety by demonstrating significant associations between hippocampal GluR1 levels and behavior in the EPM assay; lower hippocampal GluR1 levels significantly associated with greater times in open arms and lower times in closed arms as well as with greater distance traveled. It is unlikely that these significant correlations are simply a reflection of significant sex differences in the behaviors and protein levels. First of all, separate analyses by sex were still able to uncover significant associations with GluR1 levels and time in the closed arm despite the reduction in sample size and power. Notably, total distance traveled, a measure that shows sex differences, did not correlate significantly with GluR1 levels in the separate analyses by sex. Finally, no such associations were seen with CREB levels and any of the EPM measures.

Despite the lack of significant associations between hippocampal CREB levels and anxiety-like behaviors, these measures all showed sex differences. Estrogen phosphorylates CREB in CA1 region in both female and male mice (Abraham et al, 2005). Yet, training in hippocampal-dependent tasks phosphorylated CREB in CA1 of male rats but had no such effect in female rats (Kudo et al, 2004). Our finding of lower GluR1 levels in female rats is consistent with our prior study using immunohistochemistry (Kosten et al, 2007) and with a prior autoradiography study of AMPA receptors in various hippocampal regions of female vs. male rats (Palomero-Gallagher et al, 2003). Further, AMPA receptor levels are greater in female rats in diestrus vs. estrus stage. In one study, estrogen receptor agonists increased GluR1 levels in dorsal hippocampus (Waters et al, 2009) although other studies report no effect of estradiol or estradiol plus progesterone treatment on hippocampal AMPA receptor density. The former study employed immunohistochemistry techniques and examined the specific subunit type whereas the latter study used autoradiography (Cyr et al, 2000; Weiland, 1992).

The hippocampus is implicated in anxiety (Barkus et al, 2010; Gray, 1982). Ventral hippocampal lesions reduce anxiety as measured in EPM (McHugh et al, 2004). Anxiety levels relate to CREB activation in hippocampus but the data are inconsistent. Various forms of CREB deletion in mice associate with enhanced anxiety (Graves et al, 2002; Hebda-Bauer et al, 2004; Valverde et al, 2004) and increasing CREB via administration of a phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor reduces anxiety (Li et al, 2009). However, overexpressing CREB in hippocampus with a viral vector has no effect on anxiety (Restivo et al, 2009). On the other hand, reduced anxiety occurs with deletion of CaMKIV, an upstream regulator of CREB, (Shum et al, 2005) and increased CREB activation induced by THC enhances the anxiolytic effects of THC (Rubino et al, 2008). These latter effects are more in line with the present study; female rats have both lower hippocampal CREB levels and less anxiety compared to male rats. Yet, CREB levels do not correlate with anxiety levels. These results suggest that the relationship between anxiety and hippocampal CREB activation is not linear as proposed for spatial memory (Viosca et al, 2009).

In contrast to the lack of relationship between hippocampal CREB and anxiety, anxiety-like behaviors are highly correlated with hippocampal GluR1 expression. That is, lower hippocampal GluR1 levels predict greater times in open arms of the EPM and lower times in closed arms indicating that higher GluR1 levels are associated with decreased anxiety. Together, these associations explain about 60% of the variability the data. Our findings are consistent with prior studies that show that GluR1 antagonists have anxiolytic effects in EPM (Kapus et al, 2008) or on punished responding (Alt et al, 2006). Further, anxiety produced by withdrawal from chronic benzodiazepine heightens GluR1 subunit incorporation into hippocampal CA1 synapses (Das et al, 2008). Data from knockout mice (gria1 or GluR-A subunit deletion) suggest a modest increased anxiety in EPM; results with another procedure (e.g., light-dark box) show no differences in the same mice (Bannerman et al, 2004; Mead et al, 2006). Since there are a limited number of studies that have investigated the role of GluR1 subunit receptor activation in anxiety models, it is difficult to explain these discrepancies except that deletion of the gene likely leads to compensation in other systems or brain regions or in another part of the GluR1 pathway. Nevertheless, data from the present study show a highly significant association between hippocampal GluR1 levels and anxiety-like behavior.

Consistent with prior studies (Ferguson et al, 2005; Johnston et al, 1990; Zimmerberg et al, 1993), female rats spend more time in open arms and less time in closed arms of the EPM compared to male rats indicating less anxiety. Female rats in the present study were tested during diestrus stage of the estrous cycle when estrogen levels are low. We chose this stage to minimize potential differences due to circulating ovarian hormone levels. Indeed, previous studies show times spent in open arms of EPM are lowest during diestrus compared to other estrous stages (Marcondes et al, 2001; Mora et al, 1996). Further, estrogen administered subcutaneously or into hippocampus has anxiolytic effects (Walf and Frye, 2006). That diestrus stage female rats demonstrate lower anxiety in EPM compared to male rats suggest that factors other than circulating estrogen levels contribute to this sex difference. However, the sex difference may reflect differences in motor activity not anxiety levels per se (e.g., see (Walf et al, 2006). In fact, female rats show greater locomotor activity (i.e., distance traveled) in EPM.

Sex differences in laterality of hippocampal GluR1 levels are seen in the present study. Male rats have higher GluR1 levels in left compared to right hippocampus whereas no side difference occurs in female rats. Laterality of GluR1 mRNA levels in CA1 and dentate gyrus is observed in rats exposed to enriched environment during periadolescence or in offspring of high licking-grooming dams relative to their comparison groups (Bredy et al, 2004). Sexual dimorphism in the dentate granule layer volume of rats and mice has been shown. This sexual dimorphism is altered in females by testosterone, correlates significantly with water maze performance (Roof and Havens, 1992), and relates to presence of androgen receptors (Tabibnia et al, 1999). Androgen receptor immunoreactivity in CA1 region shows laterality in intact male rats and in female rats treated with testosterone but not in castrated male rats (Xiao and Jordan, 2002). The functional relevance of this laterality effect can be seen by effects of TTX inactivation of right hippocampus on spatial memory. Impairment is greater in female vs. male rats (Cimadevilla and Arias, 2008). According to our data, we predict that male rats would be less impaired because they have higher levels of GluR1 in the intact (left) hippocampus compared to the inactivated (right) hippocampus and relative to female rats.

In summary, we demonstrate lower GluR1 and CREB levels in hippocampus in female vs. male rats. Further, GluR1, but not CREB levels, in hippocampus directly associate with anxiety-like behavior in EPM such that lower GluR1 levels are associated with less anxiety-like behaviors. These data suggest that agents acting at GluR1 receptors may be potential treatments for anxiety disorders and that the focus on NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptor agents (Barkus et al, 2010) be expanded to include agents that act on AMPA receptors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse grant to TAK (DA 020117). XX was supported by a fellowship from the Chinese government. We thank Dr. Alicia Walf for her expert guidance in the elevated plus maze procedure and its analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; CaMKII, calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; CaMKIV, calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV; CREB, cyclic-AMP response element binding protein; EPM, elevated plus maze; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; pCREB, phosphorylated CREB; PDE4, phosphodiesterase-4; PKA, protein kinase A

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Abraham IM, Herbison AE. Major sex differences in non-genomic estrogen actions on intracellular signaling in mouse brain in vivo. Neuroscience. 2005;131:945–951. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt A, Weiss B, Ogden AM, Li X, Gleason SD, Calligaro DO, et al. In vitro and in vivo studies in rats with LY293558 suggest AMPA/kainate receptor blockade as a novel potential mechanism for the therapeutic treatment of anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2006;185:240–247. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Deacon RMJ, Brady S, Bruce A, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, et al. A comparison of GluR-A-deficient and wild-type mice on a test battery assessing sensorimotor, affective, and cognitive behaviors. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:643–647. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkus C, McHugh SB, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Rawlins JNP, Bannerman DM. Hippocampal NMDA receptors and anxiety: At the interface between cognition and emotion. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;626:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy TW, Zhang TY, Grant RJ, Diorio J, Meaney MJ. Perpubertal environmental enrichment reverses the effects of maternal care on hippocampal development and glutamate receptor subunit expression. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;20:1355–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimadevilla JM, Arias JL. Different vulnerability in female's spatial behaviour after unilateral hippocampal inactivation. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;439:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, Ghribi O, DiPaolo T. Regional and selective effects of oestradiol and progesterone on NMDA and AMPA receptors in the rat brain. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2000;12:445–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Lilly SM, Zerda R, Gunning WT, Alvarez FJ, Teitz EI. Increased AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit incorporation in rat hippocampal CA1 synapses during benzodiazepine withdrawal. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;511:832–846. doi: 10.1002/cne.21866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SA, Gray EP. Aging effects on elevated plus maze behavior in spontaneously hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto and Sprague-Dawley male and female rats. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;85:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves L, Dalvi A, Lucki I, Blendy JA, Abel T. Behavioral analysis of CREB αδ mutation on a B6/129, F1 hybrid background. Hippocampus. 2002;12:18–26. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo-Hippocampal System. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, McGaugh JL. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide-mediated disruption of hippocampal cAMP response element binding protein levels impairs consolidation of memory for water maze training. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 1997;94:2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebda-Bauer EK, Watson SJ, Akil H. CREBαδ- deficient mice show inhibition and low activity in novel environments without changes in stress reactivity. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;20:503–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston AL, File SE. Sex differences in animal tests of anxiety. Physiology & Behavior. 1990;49:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90039-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapus GL, Gacsaly I, Vegh M, Kompagne J, Hegedus E, Leveleki C, et al. Antagonism of AMPA receptors produces anxiolytic-like behavior in rodents: Effects of GYKI 52466 and its novel analogues. Psychopharmacology. 2008;198:231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1121-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Karanian DA, Haile CN, Yeh J, Kim JJ, Kehoe P, et al. Memory impairments and hippocampal modifications in adult rats with neonatal isolation stress experience. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2007;88:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Sanchez H, Jatlow PI, Kehoe P. Neonatal isolation alters estrous cycle interaction on acute behavioral effects of cocaine. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo K, Qiao C-X, Kanba S, Arita J. A selective increase in phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein in hippocampal CA1 region of male, but not female, rats following contextual fear and passive avoidance conditioning. Brain Research. 2004;1024:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-F, Huang Y, Amsdell SL, Xiao L, O'Donnell JM, Zhang H-T. Antidepressant- and anxiolytic-like effects of the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor rolipram on behavior depend on cyclic AMP response element binding protein-mediated neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2404–2419. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes FK, Miguel KJ, Melo LL, Spadari-Bratfisch RC. Estrous cycle influences the response of female rats in the elevated plus-maze test. Physiology & Behavior. 2001;74:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory--a century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh SB, Deacon RM, Rawlins HN, Bannerman DM. Amygdala and ventral hippocampus contribute differentially to mechanisms of fear and anxiety. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:63–78. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead AN, Morris HV, Dixon CI, Rulten SL, Mayne LV, Zamanillo D, et al. AMPA receptor GluR2, but not GluR1, subunit deletion impairs emotional response conditioning in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:241–248. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora S, Dussaubat N, Diaz-Veliz G. Effects of the estrous cycle and ovarian hormones on behavioral indices of anxiety in female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(96)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos GG, Spyraki C. Influence of oestrogen on spontaneous and diazepam-induced exploration of rats in an elevated plus maze. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:691–696. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomero-Gallagher N, Bidmon H-J, Zilles K. AMPA, kainate, and NMDA receptor densities in the hippocampus of untreated male rats and females in estrus and diestrus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2003;459:468–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.10638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE, Briley M. Validation of open:closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1985;14:149–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restivo L, Tafi E, Ammassari-Teule M, H M. Viral-mediated expression of a constitutively active form of CREB in hippocampal neurons increases memory. Hippocampus. 2009;19:228–234. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof RL, Havens MD. Testosterone improves maze performance and induces development of a male hippocampus in females. Brain Research. 1992;572:310–313. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90491-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Guidali C, Vigano D, Realini N, Valenti M, Massi P, et al. CB1 receptor stimulation in specific brain areas differently modulate anxiety-related behavior. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgerical Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum FWF, Ko SW, Lee Y-S, Kaang B-K, Zhuo M. Genetic alteration of anxiety and stress-like behavior in mice lacking CaMKIV. Molecular Pain. 2005;1:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AJ, Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Kida S. CREB and memory. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1998;21:127–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabibnia G, Cooke BM, Breedlove SM. Sex difference and laterality in the volume of mouse dentate gyrus granule cell layer. Brain Research. 1999;827:41–45. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglenova J, Parameshwaran K, Suppiramaniam V, Breese CR, Pandiella N, Birru S. Long-lasting teratogenic effects of nicotine on cognition: gender specificity and role of AMPA receptor function. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2008;90:527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde O, Mantamadiotis T, Torrecilla M, Ugedo L, Pineda J, Bleckmann S, et al. Modulation of anxiety-like behavior and morphine dependence in CREB-deficient mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1122–1133. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viosca J, Malleret G, Bourtchouladze R, Benito E, Vronskava S, Kandel ER, et al. Chronic enhancement of CREB activity in the hippocampus interferes with the retrieval of spatial information. Learning and Memory. 2009;16:198–209. doi: 10.1101/lm.1220309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA. A review and update of mechanisms of estrogen in the hippocampus and amygdala for anxiety and depression behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1097–1111. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:322–328. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters EM, Mitterling K, Spencer JL, Mazid S, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta specific agonists regulate expression of synaptic proteins in rat hippocampus. Brain Research. 2009;1290:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland NG. Estradiol selectively regulates agonist binding sites on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Endocrinology. 1992;131:662–668. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1353442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Jordan CL. Sex differences, laterality, and hormonal regulation of androgen immunoreactivity in rat hippocampus. Hormones and Behavior. 2002;42:327–336. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerberg B, Farley MJ. Sex differences in anxiety behavior in rats: role of gonadal hormones. Physiology & Behavior. 1993;54:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90335-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]