Abstract

Thermostable DNA polymerases isolated from archaeal organisms have not been completely characterized kinetically and require further study to understand both their dNTP binding mechanism and their role within the organism. Here, we demonstrate that the thermostable Family B DNA polymerase from Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu Pol) contains sensitive determinants of both dNTP binding and replicational fidelity within the highly conserved Motif A. Site-directed mutagenesis of the Motif A SYLP region revealed that small shifts in side chain volume result in significant changes in dNTP binding affinity, steady state kinetics, and fidelity of the enzyme. Mutants of Y410 show high fidelity in both misincorporation assays and forward mutation assays, but display a substantially higher Km than WT. In contrast, mutations of the upstream residue L409 result in drastically reduced affinity for the correct dNTP, a much higher efficiency of both misincorporation and mismatch extension, and substantially lower fidelity as demonstrated by a PCR-based forward mutation assay. The A408S mutant, however, displayed a significant increase in both dNTP binding affinity and fidelity. In summary, these data show that modulation of Motif A can greatly shift both the steady and pre-steady state kinetics of the enzyme as well as fidelity of Pfu Pol.

Keywords: Pyrococcus furiosus, Thermostable DNA Polymerase, dNTP binding, Motif A, fidelity

DNA polymerases, which are conserved throughout Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya, are responsible for replication and maintenance of their respective organism’s genomes. These polymerases have been organized into broad families by sequence similarity, and most DNA polymerases responsible for chromosomal replication are grouped into Families B and C with prominent examples being the eukaryotic δ and ε polymerases and E. coli Polymerase III α subunit, respectively (1). Family B also contains many virus, phage, and archaeal DNA polymerases including the well-studied RB69 gp43 polymerase (2).

Many archaeal DNA polymerases from hyperthermophilic organisms, which are uniquely capable of synthesizing DNA at extremely high temperatures, have been isolated but have yet to be studied in mechanistic detail. In addition to Thermus aquaticus Polymerase (Taq Pol) (3), several thermostable archaeal Y family DNA polymerases such as DinB homolog (Dbh) and DNA Polymerase IV (dpo4), thought to be involved in DNA repair, have been kinetically characterized (4, 5). The thermostable B family polymerase Vent polymerase has been characterized for its ability to incorporate nucleotide analogs (6), but a detailed study of dNTP binding, kinetics and replicational fidelity of this and other thermostable B Family polymerases remains to be conducted.

The thermostable Pfu DNA polymerase (Pfu Pol) is an archaeal Family B or human pol α-like DNA polymerase isolated from Pyrococcus furiosus (7). Pfu Pol has superior fidelity compared to thermostable Taq DNA polymerase due to 3′ to 5′ proofreading exonuclease activity (8). Pfu Pol, like other Family B DNA polymerases, contains the conserved domains Motif A and Motif C. These domains form the core molecular surface of the active site in the palm domain and coordinate the two metal ions necessary for catalysis (9). Specifically, Motif A contains two of the aspartate residues which participate in coordination of these metals, and it also contains a central SLYP motif which is solvent exposed in the prototypical RB69 gp43 polymerase. In crystal structures of RB69 gp43 polymerase and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) containing both template/primer (T/P) and substrate, the side chain of the Motif A tyrosine (SLYP) has been shown to stack with the ribose of the incoming dNTP (Fig. 1A). This residue is also known to participate in substrate selection and is thought to sterically clash with the rNTP 2′OH. This prevents incorporation of rNTPs by both DNA-dependent and RNA-dependent DNA polymerases such as φ29, RB69 gp43, Vent, and MuLV RT (10–13). Similarly, Pfu Pol Motif A contains Y410, which is analogous to the well studied aromatic residues described above. In this manuscript, we have experimentally tested the hypothesis that this amino acid of Pfu Pol Motif A and its surrounding residues may be essential for optimal dNTP binding affinity and replicational fidelity by modifying the conserved central tyrosine and its surrounding residues. The results of this analysis provide an understanding of the role of Motif A in dNTP binding, discrimination, and incorporation in a thermostable Family B polymerase.

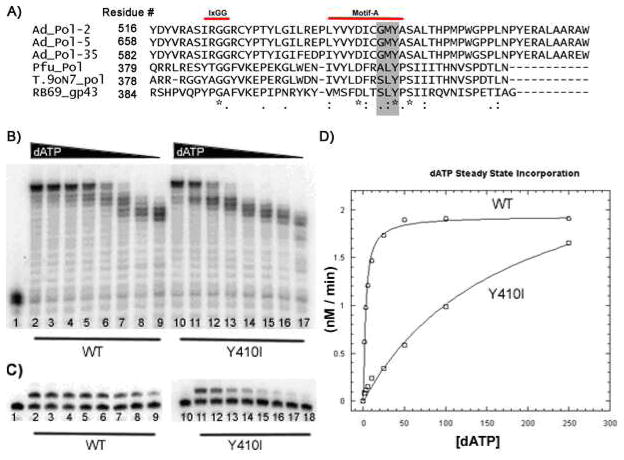

Figure 1. PFU Steady State Kinetics and dNTP Utilization.

A) Clustal-W multialignment of Adenovirus (serotypes 2,5,35), Pfu Pol, Thermococcus species 9oN7° Pol, and RB69 gp43 phage polymerase Motif-A. The specific area of interest to this study is highlighted in grey. “*” represents identical residues, “:” represents conserved substitutions, and “.” Represents semi-conserved substitutions B) Multiple nucleotide incorporation reactions were carried out with a 5′ end 32P-labeled 23-mer primer annealed to a 40-mer DNA template at 55° C for 5 minutes with varying amounts of all four dNTPs. No enzyme control (lane 1) indicates the position of the 23-mer unextended primer. A representative multi-nucleotide dNTP titration for WT Pfu Pol 3′–5′ exo - (lanes 2–9) and Pfu Pol Mutant Y410I (lanes 10–17) is shown; concentrations of dNTP for each set of eight reactions was as follows: (in μM) 250,100, 50, 25, 10, 5, 2.5, 1. C) Representative single nucleotide (dATP) titrations for WT Pfu Pol (lanes 2–9) and Y410I (lanes 11–18) were carried out at 55°C as described in B) except using only dATP. D) Nonlinear regression fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the single nucleotide extension performed in duplicate for WT (circles) and Y410I (squares).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Pfu Pol Mutants

Overlap extension PCR was used to generate mutant Pfu Pol exonuclease-inactive (D215A) derivatives, which were then inserted into pET28a plasmids (Novagen) for bacterial expression. The Motif A mutations were then created by PCR-based site directed mutagenesis.

Purification of Pfu Pol

Pfu Pol proteins were overexpressed in E. coli BL21 pLysS (Invitrogen) from pET28a plasmids containing the Pfu Pol genes, which are fused to six histidine residues at their N-terminal ends. Following lysis and centrifugation, the hexahistidine-tagged polymerases were purified using Ni2+ chelation chromatography as described previously. (14–16). Following two dialysis steps in Pfu dialysis buffer (50% glycerol, 50mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8), the protein was compared to .5 – 4ug of 98% pure Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA; Biorad) by 10% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and Coomassie blue staining. This analysis was used to estimate protein concentration (at ~ 2mg per liter of protein of interest) to approximate protein purity (which was similar to the 98% pure BSA).

Steady State Kinetic Assays

DNA 40mer template was annealed to 23mer 32P 5′ end- labeled primer as described (15). 20nM of the template/primer complex (T/P) was extended with Pfu Pol in the following conditions for all reactions at 55° C for 5 minutes and quenched with stop dye (10 μl of 40 mM EDTA, 99% formamide) and incubated for 5 minutes at 95° C. First, protein dilution reactions were conducted with 250μM dATP to normalize the activities of the Pfu Pol proteins displaying ~50% extension (equal fully extend and unextended products) in single dATP extension reactions. Then, these protein concentrations displaying the 50% primer extension were used for subsequent dATP (Amersham Biosciences) single nucleotide extension titrations at defined substrate concentrations 250, 100, 50, 25, 10, 5, 2.5, and 1 μM. The Michaelis-Menten constant was obtained from nonlinear regression fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation, and values obtained were subsequently verified with Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plots.

Pre-Steady State Kinetic Assays

First, single turnover burst assays were performed to assess the active site concentrations of WT and mutant Pfu Pol proteins on a 5′ end 32P-labeled DNA 23-mer annealed to the DNA 40-mer. 800μM TTP was mixed rapidly with 100nM Pfu Pol protein pre-complexed with100nM 32P-labeled T/P and 200nM cold T/P in a Rapid Quencher (Kintek RFQ3). Subsequent quenching with 0.5M EDTA at a set range of time points was then performed, and the product formation at each time point was analyzed and fitted to Equation 1, which determined the active site concentration of each Pfu Pol protein. Second, the presteady state reactions with 200nM active protein and 100nM T/P 100nM were performed to assess the observed rates of product formation (kobs) at 6–7 time points in duplicate per dTTP concentration. The kobs values were then fitted to Equation 2 as described below to obtain Kd and kpol.

Data Analysis

For the pre-steady state assays, data were curve-fitted with nonlinear regression to Equations 1 and 2 with the software package KaleidaGraph as described (17, 18).

| (1) |

Equation 1 was used to obtain the amplitude of the burst (A) from a burst assay time course. This allowed calculation of the percentage of active Pfu Pol molecules in an individual protein preparation. Resulting kobs values from dNTP titration experiments were then fitted with Equation 2 to obtain Kd and kpol.

| (2) |

PCR-based lacZα Forward Mutation Assay

Both WT exo+, exo−, and mutant thermostable Pfu Pol (all exo−), purified as described above, were diluted serially to determine optimal protein concentration for inverse PCR of the entire pUC18 (3,218 bp) DNA by analyzing reaction product on a 0.7% agarose gel. These concentrations were then used in a 100μl PCR reaction with a starting template of AflIII-linearized pUC18 template at a concentration of 50ng. These reactions were sampled every 5 cycles, and copy number was subsequently determined after a 106 dilution via QT-PCR with the TaqMan probe (5′-TAM TCTTCCGCTTCCTCGCTCACTGA-FAM-3′) with the amplification oligomers: (5′–AGAGGCGGTTTGCGTATT–3′) and (5′–TGTTCTTTCCTGCGTTATCC– 3′). The PCRs were then terminated at the cycles giving very similar copy numbers of the amplified products by the Pfu Pol proteins. These amplified entire pUC18 DNA products were purified via Qiagen column, digested with BglII, ligated and transformed via electroporation into the α-complemented E. coli strain XL-1 blue (Stratagene) and plated on IPTG, carbenicillin, and Xgal containing 2X-YT agar plates. Note that the BglII restriction site lies in the non-essential region of pUC18. Blue (wild-type) and white/pale blue (mutant) colonies were then counted at a sample size greater than 500 for the entire experiment; this analysis was performed in triplicate for each Pfu Pol derivative. This entire procedure was also performed with no enzyme, and the value obtained was subtracted from values obtained for the Pfu Pol derivatives. Though the white/blue value obtained for the no enzyme experiment ranged from .09 to .11, which was higher than expected, it was consistent throughout all experiments and was substantially lower than any values obtained for Pfu Pol experiments. The mutant colonies from the reactions with WT and L409M proteins were also randomly selected for sequencing, and these were then compared to an overall consensus to determine the mutational spectrum. Little or no founder mutations were evident in subsequent alignments of sequenced mutants, indicating that template doublings were effectively minimized and mutations above background were indeed due to mutation synthesis during DNA synthesis.

Terminal Transferase Assay

A 19-mer DNA template annealed to an 18-mer 5′ end 32P labeled DNA primer was prepared as previously described (19). Reactions were completed with dATP or dCTP at 250μM with an equal activity under conditions as described above

Visualization and Quantification of Biochemical Assays

All reactions completed in the steady or pre-steady state with Pfu Pol were processed similarly. 4 μl of the final reaction products were quantified by phosphorimaging analysis (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) of 16% acrylamide-urea denaturing gels (SequaGel, National Diagnostics; model S2 sequencing gel electrophoresis apparatus, Labrepco). Signal was quantified with the Optiquant or Quailty One (Biorad) software packages by comparing the amount of extended product to the total signal per reaction.

RESULTS

Kinetic Analysis of Pfu Pol Motif A Mutants

The central “steric gate” tyrosine (Tyr) or phenylalanine (Phe) in the well-conserved Motif A is responsible for the selective utilization of dNTP versus rNTP substrates by many Pol α family polymerases and reverse transcriptases. This Tyr or Phe residue is presumed to sterically clash with the rNTP 2′ OH and likely participates in a Van der Waals stacking interaction with the sugar moiety of the incoming dNTP substrate. To investigate the role of the corresponding residue in the functional activity of the Pfu DNA polymerase, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on the Tyr 410 (Y410) residue of Pfu DNA polymerase and its two preceding residues, L409 and A408. To minimize the gross structural effects of these substitutions, we mutated these targeted residues of Motif A to amino acids with physicochemical characteristics similar to the wild type residues. We therefore created the following mutants: Y410L, Y410I, Y410V, L409I, L409V, L409M, L409F, and A408S. Initially, we employed a steady state kinetic screening assay at 55° C to evaluate the overall impact of the Motif A mutations on the dNTP concentration-dependent product formation in the polymerase background without 3′–5′ exonuclease activity (D215A substitution). Subsequent pre-steady state kinetic analysis and steady state fidelity assays were then performed with Pfu Pol WT and select mutants to investigate the specific effects of Motif A mutations.

First, in both steady state single and multiple nucleotide incorporation analyses, we observed that mutations at residues 410, 409, and 408 altered incorporation kinetics. Y410I displayed the most significant reductions in dNTP concentration-dependent activity among the mutants tested in both multiple (Fig. 1B) and single (Fig. 1C) incorporation reactions. Quantifying the products of a similar single nucleotide extension reaction and fitting them to the Michaelis-Menten equation allowed us to obtain Km and kcat (Fig. 1D and Table 1). Although steady-state kinetics assays do not reveal the specific mechanistic effects resulting from active site mutations, they are useful to screen many mutants and may indicate overall enzyme function or disfunction (i.e. they report the sum of the entire deoxynucleotide incorporation equilibrium reviewed in (20)). Comparison of Pfu Pol WT exo− to Y410 mutants revealed a profound defect in dNTP utilization at lower substrate concentrations in both multiple nucleotide and single nucleotide extension. We observed a 20 to 61 fold difference in Km when comparing WT to the Y410 mutants, representing the largest kinetic defect. Mutation of the L409 residue resulted in a more subtle steady state defect relative to WT, with an approximate 5 fold difference between the WT enzyme versus L409I or L409V (Table 1). Possibly, alterations of Y410 itself or the neighboring side chains to a less bulky hydrophobic residue reduce or shift the molecular surface available for a Van der Waals interaction with the ribose moiety of an incoming dNTP. In contrast, a conservative substitution of the A408 residue with serine had little effect on steady state kinetic parameters (reflected by only a slight reduction in Km), although it did result in increased affinity for the incoming dNTP as measured by the presteady state kinetics (see blow and Table 1). We also constructed and examined additional residue A408 mutants (G, C, and V), and surprisingly found that these mutants had either grossly impaired activity or were completely inactive (data not shown) in contrast to the more conservative A408S mutant (Table 1). This demonstrates that A408 plays an important structural role in the function of the Motif A loop and is essential for polymerase function.

Table 1.

Motif-A Mutant Steady State Kinetic Parameters (55°C)

| Pfu Pol * | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (μM−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.022 ± 0.003 | 0.009 |

| Y410L | 69 ± 16 | 0.31 ± 0.043 | 0.004 |

| y410i | 130 ± 7.3 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.002 |

| y410v | 46 ± 7.7 | 0.029 ± 0.006 | 0.001 |

| l409i | 14 ± 6.5 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.002 |

| L409M | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 0.028 ± 0.001 | 0.014 |

| l409v | 12 ± 0.4 | 0.034 ± 0.006 | 0.003 |

| A408s | 10 ± 1.2 | 0.037 ± 0.001 | 0.004 |

all are 3′–5′ exonuclease inactive D215A mutation.

Pre-steady State Kinetics of Pfu Pol Motif A Mutants

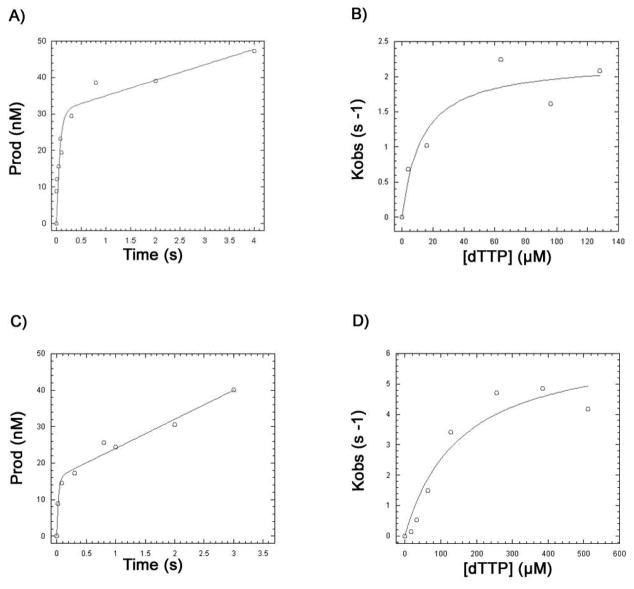

Steady state kinetics can indicate general changes in enzyme function, but to fully understand Pfu Pol kinetics we conducted pre-steady state quench flow analysis. To further characterize the mechanistic alterations made by the Pfu Pol Motif A mutants, we chose WT and three mutants, A408S, L409M, and Y410V, and performed pre-steady state analysis of incorporation of the template cognate nucleotide (dTTP). First, we determined the active site concentration of each of the Pfu Pol proteins in burst reactions (Fig. 2A and 2C for WT and L409M, respectively). We observed approximately 20–60% activity amongst the Pfu Pol proteins. Next, a single round pre-steady state dTTP titration for each protein was performed (Fig. 2B and 2D for WT and L409M, respectively). Similar to the trend observed in the steady state assays, we observed a decrease in binding affinity for all mutants involving residues 409 and 410 (Table 2). Indeed, both L409M and Y410V mutants had a higher Kd than WT, with the defect exhibited by L409M being most substantial at 21 fold (Table 2). Our pre-steady state analyses indicate that very small side chain volume shifts in the Pfu Pol Motif A residues can significantly alter not only the dNTP affinity but also its maximum rate of conformational change and catalysis (kpol).

Figure 2. Pre-steady State Active Site Titrations and dNTP Titration Curve for WT and L409M.

The burst kinetic study was conducted in duplicate for all mutants as well as WT Pol at 37° C, and the mean product formation per time was used to assess the occurrence of the burst, and the activate site concentrations were determined by Equation 1. Template/Primer (T/P) was used in 3 fold excess of enzyme allowing both presteady and steady state incorporation to be examined. A) WT Pfu Pol active site titration; this preparation was 29% active. B) WT Pfu Pol pre-steady state dNTP titration using 100nM active protein with 25nM T/P. C) L409M active site titration; this preparation was 20% active. D) L409M pre-steady state dNTP titration using 100nM active protein with 25nM T/P.

Table 2.

Motif-A Mutant Pre-steady State Kinetic parameters (37°C)

| Pfu Pol * | Kd (μM) ** | kpol (s−1) | kpol/Kd |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 14 ± 2.8 | 2.2 ± 0.01 | 0.15 |

| Y410V | 38 ± 27 (3X) | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.10 |

| L409M | 310 ± 8.5 (22X) | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 0.03 |

| A408S | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.42 |

all are 3′–5′ exonuclease inactivD215A mutation.

reactions were performed at 37°C

Impact of Motif A Mutations on Pfu Pol Fidelity

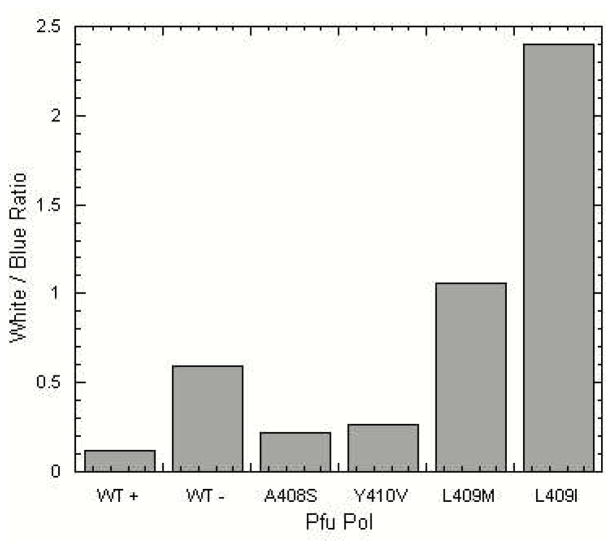

Next, we investigated whether Motif A mutations also affect enzyme fidelity. First, we established a new PCR-based lacZα forward mutation assay. In this assay, the entire pUC18 plasmid was amplified to an equivalent extent by each of the Pfu Pol protein mutants, as determined by quantitative PCR (see Methods and Materials). The amplified linear pUC18 DNAs were then digested, ligated, and transformed to XL-1 Blue E. coli host cells, and the cells were plated on IPTG/X-gal agar. The numbers of mutant (pale blue and white) colonies and wild-type (dark blue) colonies were counted and used to determine the mutant rate for each Pfu Pol protein. As a test of this assay system, we performed control reactions using WT Pfu Pol with and without 3′ to 5′ proofreading exonuclease activity. As shown in Figure 5, we observed that the exo+ Pfu Pol showed 26 times lower mutation frequency than the exo− Pfu Pol. The extent of this fidelity difference is comparable with the fold difference previously reported in reversion-based mutation assays, thus validating our PCR-based fidelity assay (8). Next, we determined the mutation rate of four Motif A mutants, Y410V, A408S, L409M and L409I. As shown in Fig. 4, the Y410V and A408S mutants displayed slightly lower mutation rates than WT exo− Pfu Pol, whereas the two L409 mutant proteins showed an increased mutation frequency.

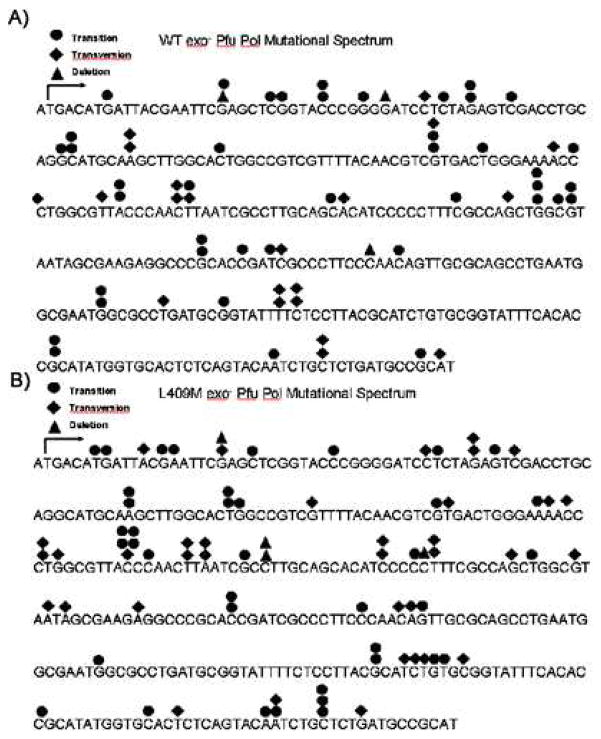

Figure 5. WT (A) and L409M (B) Pfu Pol Mutational Spectrum.

The types ofmutation produced by WT or L409M exo- polymerases are overlaid upon the lacZα sequence for WT (A) and L409M (B).

Figure 4. Mutant Frequency of Pfu DNA Polymerase Motif-A Mutants.

The mean ratios of (Pale Blue + White)/Blue colonies (grey bars) are displayed for the lacZα forward mutation assay performed in triplicate as described in Experimental Procedures. The columns display data for WT +: WT Pfu Pol with 3′–5′ exonuclease, WT −: Pfu Pol without the exonuclease, A408S, Y410V, L409M, and L409I, (note that all mutant enzymes were 3′–5′ exonuclease deficient, unless otherwise indicated). A No Enzyme control was performed to assess the background frequency of lacZα mutation; these background values were subtracted from the values calculated for each of the Pfu DNA polymerase Motif-A mutants. Results shown represent mean mutant frequencies and standard deviations are as follows: WT+ 0.026, WT− 0.063, A408S 0.049, Y410V 0.081, L409M 0.292, and L409I 1.362.

Next, we employed primer-extension-based polymerase fidelity assays that monitor misinsertion and mismatch extension, which are two key steps involved in the synthesis of a single mutation during the enzymatic DNA polymerization reaction. First, we normalized the input activity for our WT and L409 mutant polymerases (Fig 3A); we then performed multiple nucleotide primer extension reactions in the presence of only three dNTPs (dATP, dTTP and dCTP). In biased dNTP pool conditions such as these polymerization pauses one nucleotide before sites where the missing dNTP (dGTP in this case) should be incorporated; these pause sites are commonly termed stop sites (see the intense bands immediately before the “+” in Fig. 3B). Low fidelity polymerases tend to add incorrect dNTPs at stop sites and thus generate a higher level of primer extension product following a stop site. Indeed, the L409F Pfu Pol mutant showed higher amounts of primer extension beyond the stop sites, indicating that it is a low fidelity Pfu mutant.

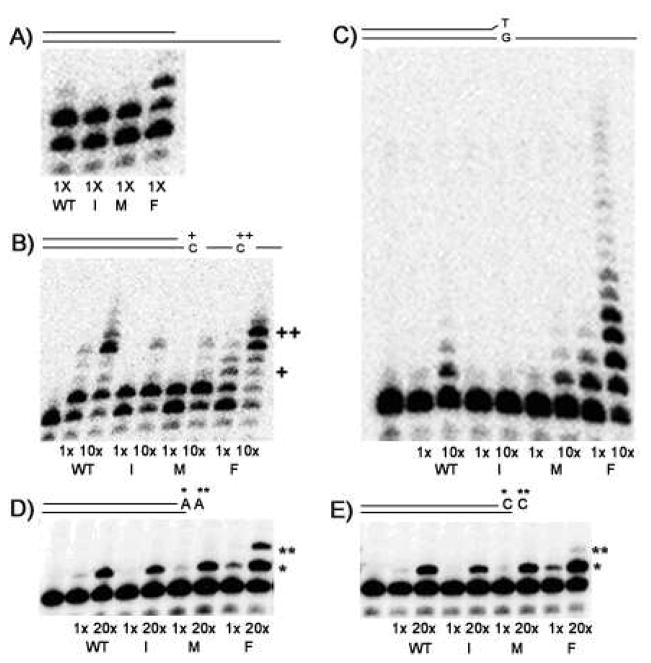

Figure 3. L409 Mutant Misinsertion, Mismatch Extension, TNTase Activity.

In A) reactions were first conducted with matched template/primer and 250 μM dTTP at 55°C to demonstrate that equal activity (1x) was used for each Pfu Pol protein (I: L409I, M: L409M, F: L409F). In B) matched template primer was used in a misincorporation assay with two equal activities (1x and 10x) of each Pfu Pol protein and 250 μM of only three dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dTTP)_without dGTP. Shown are the sites of the first (+) and second (++) templated cytosines respectively. C) Extension of a G/T mismatched T/P by WT and L409 mutants in the presence of 250 μM four dNTP’s. D) ) Extension of a 18-mer/19-mer T/P (T templated) by two equal activities and 20x) by Pfu Pol Wt and L409 mutants in the presence of 250 μM dATP. “*”: the first dATP incorporation, “**”: the second untemplated dATP incorporation. E) Extension of a 18-mer/9-mer T/P (G templated) by two equal activities (1x and 20x) by Pfu Pol WT and L409 mutants in the presence of 250 μM dCTP.

We also simulated the second step of mutation synthesis, mismatch extension, by performing a similar primer extension reaction using a mismatched primer and all four dNTPs (Fig. 3C). In this reaction, the L409F mutant displayed extensive mismatch extension activity. It is important to note that this mutant obligatorily appends additional nucleotides, even at very low levels of input activity (Fig. 3C and 3A respectively). Taken together, both the PCR-based forward lacZα mutation assay and the gel-based fidelity assays confirmed that mutations in the L409 residue lower the fidelity of Pfu Polymerase. Interestingly, similar steady state characterization of mutants of the analogous residue (L868) in human polymerase α also showed an elevated ability to bypass aberrant DNA lesions and a higher error frequency than WT, as shown by both reversion and forward mutation assays (21).

Untemplated Nucleotide Addition Activity of Pfu L409F Mutants

From the data discussed above, the L409 residue appears to be essential for maintaining the fidelity of Pfu Pol. Pfu Pol L409F exhibits the highest efficiency of misincorporation and mismatch extension in the qualitative gel extension assays (Fig. 3), even though this mutant was unable to complete a PCR reaction under the conditions used in our forward mutation assay described below. To further analyze the low fidelity of the L409F mutant, we tested whether this mutant was able to polymerize DNA in the absence of the template. This test was based on the notion that low fidelity enzymes may incorporate dNTPs even in the absence of proper base pairing with template nucleotides and/or without the need for the enzyme active site to be occupied by a template DNA.

For this test, we employed a 5′ end-labeled 18mer primer annealed to 19mer templates, generating 5′ end single nucleotide overhangs (T for Fig. 3C and G for Fig. 3D). These 18mer/19mer T/Ps were incubated with an equal amount of active polymerase (WT and L409F proteins; see Fig 3A). As shown in the reactions with dATP (Fig. 3C) or dCTP (Fig. 3D), L409F was able to incorporate a second untemplated dATP or (dCTP), whereas WT enzyme did not show any significant incorporation of an untemplated dNTP. This ability to incorporate a second dATP/dCTP could be due to primer-template slippage. However, we designed a template sequence that is unlikely to form slippage intermediates (see Methods and Materials). Thus, we conclude that the L409F mutant displays high untemplated dNTP incorporation capability, which is mechanistically similar to the incorporation of mispaired or unpaired dNTPs.

Mutation Spectrum Effect of the L409 Mutant

Finally, we tested whether the error-prone L409 mutants produce a distinct mutational spectrum when compared to WT Pfu DNA polymerase. For this test, we selected mutant colonies from the PCR-based forward mutation assay for the WT and L409 mutants and sequenced the lacZα region of the plasmid recovered from the mutant colonies. The L409F mutant was a logical choice for this analysis because of its profound effect on enzyme fidelity in our other assays. However, this mutant was insufficiently active to generate a PCR product in our novel lacZ forward mutation assay. We therefore selected the L409M mutant for analysis. As shown in Table 2, the L409M mutant showed more transversions and fewer transitions than WT exo−. Similar active site architecture changes have been shown to produce equivalent mutator phenotypes, with a bias toward transversion, in thermostable Taq Pol (22). In addition, the WT and L409M polymerases displayed significantly different mutational hot spots (Fig. 5), indicating that the L409M mutation affects the mutation spectrum specificity as well as the mutation rate, as summarized in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

We present here a detailed kinetic characterization of Pfu Pol, which provides a more complete understanding of the interaction of a thermostable DNA polymerase with its dNTP substrate. These studies shed light on the role of the conserved Motif A in Pfu Pol, which is not only informative from a biochemical perspective, but may also aid in the development of therapeutics targeting related viral DNA polymerases that are insoluble or otherwise difficult to study/characterize (i.e. Adenovirus DNA polymerase). Moreover, the details of thermostable Pfu Pol kinetics and fidelity are of interest both to the biotechnology community and to those studying archaeal DNA replication machinery.

As indicated by both steady state and pre-steady state kinetics, conservative substitutions of the Y410 residue in Motif A of the polymerase impacts the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate, suggesting that the Pfu polymerase likely interacts with the incoming dNTP in a way similar to other Family B polymerases (10, 12, 13). Subtle shifts in residue L409 adjacent to Y410 produce drastic changes in Pfu Pol fidelity, assessed both biochemically and by the newly established PCR-based forward mutation assay. Interestingly, among the conservative L409 mutants that we studied, L409M may be unique, as demonstrated by the subtle defect in Km and drastic defect in Kd when compared to WT. The relatively higher kpol and possibly a faster overall product release step may compensate for the low relative affinity L409M has for the incoming dNTP, though this requires further study.

Pfu Pol can serve as a tractable model for insoluble or otherwise recalcitrant α-like viral polymerases that may be medically or therapeutically important. We therefore conducted our reactions at 37°C in order to assess dNTP binding at a biologically relevant temperature. Thermostable enzymes are thought to be more rigid than mesophilic ones and are known to function poorly at mesophilic ranges from 20°–37°C (reviewed in (23)). Comparison of mesophilic to thermostable adenylate kinase revealed a lower turnover number at low temperatures due to a slower rate of conformational change required for catalysis to occur (24).

DNA polymerases have previously been shown to undergo substantial dNTP-binding conformational change before catalysis and Pfu Pol may be similarly impacted at mesophilic temperatures. When compared to Vent polymerase and RB69 gp43 polymerase, the amplitude of our burst occurs at a later time point (100ms), which can easily be explained by our suboptimal reaction temperature of 37°C relative to the optimal temperature of 72°C. Similarly, Pfu Pol kpol values are likely lower than their maximal value due to reaction temperature. Overall temperature-dependent differences in kinetic parameters are intriguing and indicate there are substantial differences in function at higher optimal temperatures. We did not measure KD or the disassociation constant of Pfu Pol for dsDNA template/primer which to our knowledge has not been measured, and temperature may also impact it. However, the final concentration of T/P in our burst assays (300nM) is well above the KD reported for Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase (10nM), RB69 gp43 DNA polymerase (<100nM), and T4 DNA polymerase (70nM) and Pfu Pol is likely saturated (3, 25, 26). Furthermore we have observed an increase in percent activity (measured by active site titration) with temperature of at least 2 fold reactions were completed at 30°C versus 60° (data not shown) which indicates that template/primer binding improves with temperature. Both template/primer binding and dNTP incorporation may shift at high temperature conditions due to the high diffusion rate and an increase in the rate of conformational change, and collectively this may explain the low activity observed in our burst assays conducted at 37°.

The kinetics of selection of dNTP versus rNTP substrates has been well characterized for both Family A (e.g., Klenow Fragment) and for Family B DNA polymerases such as Vent, φ29, and RB69, and both MuLV and HIV-1 reverse transcriptases (10–13, 27, 28). Exclusion of rNTPs by Klenow Fragment is mediated by residue E710 and the nearby F762 residue, through a presumed direct steric clash with the incoming nucleotide 2′ OH. In Family B DNA polymerases a similar effect is mediated by a single Tyr residue which is functionally analogous to these Klenow residues (29). Specifically, it has been suggested that a central Tyrosine ring may sterically clash with the 2′ OH of the rNTP substrate, and it has been shown that mutations that disrupt this moiety permit an enhanced steady state incorporation of rNTPs (10, 12, 30). Although no pre-steady state kinetics have been determined for similar mutants of reverse transcriptases, MuLV RT exhibits a slight decrease in Km upon substitution of F155V (11).

Both φ29 (Y254) and Vent (Y412) polymerases have a subtle steady state defect upon permutation of the conserved central Y to V, L, or F (10, 12). More interesting, however, is the pre-steady state characterization of the Y416A and Y416F mutants of RB69 polymerase. The Y416A substitution exhibits a similar Kd (dNTP) to WT, relative to the 3 fold increase shown by Y416F (13). This implies the hydroxyl moiety may play a role in the ring orientation that is favorable for binding and that Y416A, though greatly decreasing the Kd for rNTP substrate, does not impact polymerase affinity for dNTPs. Thus, the bulky hydrophobic side chains (I,V,L) used to replace the key tyrosine (Y410) in this study of Pfu Pol are likely in a distinct conformation relative to the WT Tyr residue. These mutations may disrupt the WT molecular surface and reduce dNTP binding affinity in a similar fashion to Y416F in RB69 Polymerase. Kinetic properties of Family B polymerases containing mutants at L409 or analogous residues have not been previously reported in the literature, although a mutator phenotype similar to that identified in this study in Pfu Pol has been documented in Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase α; this directly supports our both our forward mutation and biochemical assay data (21). Overall, L409 mutants with increasing side chain volume have successively more drastic fidelity defects, culminating with L409F, which misincorporates with exceptional efficiency. This suggests that L409 participates architecturally in overall polymerase function with respect to base selection, and that its replacement with large hydrophobic side chains may bias the active site towards misincorporation over incorporation.

In conclusion, our results clearly demonstrate that Motif A contains crucial determinants of WT fidelity (L409), and, that conservative modification of specific residues can directly affect dNTP binding kinetics and fidelity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erin Noble for helpful suggestions. This research was supported by CA122213 (BK, SD), DOD W81XWH-07-10376 (BK, SD) and training grant T32 AI00736 (EK).

References

- 1.Ito J, Braithwaite DK. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4045–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braithwaite DK, Ito J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:787–802. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.4.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandis JW, Edwards SG, Johnson KA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2189–200. doi: 10.1021/bi951682j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiala KA, Suo Z. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2106–15. doi: 10.1021/bi0357457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer J, Restle T. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40552–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner AF, Joyce CM, Jack WE. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11834–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uemori T, Ishino Y, Toh H, Asada K, Kato I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:259–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cline J, Braman JC, Hogrefe HH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3546–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.18.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sousa R. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnin A, Lazaro JM, Blanco L, Salas M. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:241–51. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao G, Orlova M, Georgiadis MM, Hendrickson WA, Goff SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:407–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner AF, Jack WE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2545–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang G, Franklin M, Li J, Lin TC, Konigsberg W. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10256–61. doi: 10.1021/bi0202171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss KK, Isaacs SJ, Tran NH, Adman ET, Kim B. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10684–94. doi: 10.1021/bi000788y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malboeuf CM, Isaacs SJ, Tran NH, Kim B. Biotechniques. 2001;30:1074–8. 1080, 1082. doi: 10.2144/01305rr06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim B. Methods. 1997;12:318–24. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skasko M, Weiss KK, Reynolds HM, Jamburuthugoda V, Lee K, Kim B. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12190–200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412859200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss KK, Chen R, Skasko M, Reynolds HM, Lee K, Bambara RA, Mansky LM, Kim B. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4490–500. doi: 10.1021/bi035258r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond TL, Roshal M, Jamburuthugoda VK, Reynolds HM, Merriam AR, Lee KY, Balakrishnan M, Bambara RA, Planelles V, Dewhurst S, Kim B. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51545–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joyce CM, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14317–24. doi: 10.1021/bi048422z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niimi A, Limsirichaikul S, Yoshida S, Iwai S, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Kool ET, Nishiyama Y, Suzuki M. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2734–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2734-2746.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki M, Yoshida S, Adman ET, Blank A, Loeb LA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32728–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vieille C, Zeikus GJ. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.1-43.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf-Watz M, Thai V, Henzler-Wildman K, Hadjipavlou G, Eisenmesser EZ, Kern D. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:945–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capson TL, Peliska JA, Kaboord BF, Frey MW, Lively C, Dahlberg M, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10984–94. doi: 10.1021/bi00160a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Cao W, Zakharova E, Konigsberg W, De La Cruz EM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6052–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Astatke M, Grindley ND, Joyce CM. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:147–65. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyer PL, Sarafianos SG, Arnold E, Hughes SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3056–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astatke M, Ng K, Grindley ND, Joyce CM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3402–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang G, Franklin M, Li J, Lin TC, Konigsberg W. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2526–34. doi: 10.1021/bi0119924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]