Abstract

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) produced via the enzyme myeloperoxidase is a major antibacterial oxidant produced by neutrophils, and Met residues are considered primary amino acid targets of HOCl damage via conversion to Met sulfoxide. Met sulfoxide can be repaired back to Met by methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr). Catalase is an important antioxidant enzyme; we show it constitutes 4–5% of the total Helicobacter pylori protein levels. msr and katA strains were about 14- and 4-fold, respectively, more susceptible than the parent to killing by the neutrophil cell line HL-60 cells. Catalase activity of an msr strain was much more reduced by HOCl exposure than for the parental strain. Treatment of pure catalase with HOCl caused oxidation of specific MS-identified Met residues, as well as structural changes and activity loss depending on the oxidant dose. Treatment of catalase with HOCl at a level to limit structural perturbation (at a catalase/HOCl molar ratio of 1:60) resulted in oxidation of six identified Met residues. Msr repaired these residues in an in vitro reconstituted system, but no enzyme activity could be recovered. However, addition of GroEL to the Msr repair mixture significantly enhanced catalase activity recovery. Neutrophils produce large amounts of HOCl at inflammation sites, and bacterial catalase may be a prime target of the host inflammatory response; at high concentrations of HOCl (1:100), we observed loss of catalase secondary structure, oligomerization, and carbonylation. The same HOCl-sensitive Met residue oxidation targets in catalase were detected using chloramine-T as a milder oxidant.

Keywords: Amino Acid, Inflammation, Methionine, Oxidative Stress, Protein Stability, Gastric Survival, Hypochlorous Acid, Neutrophil, Pathogen, Ulcer

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori colonizes over one-half of the human population, and it is the leading cause of gastric ulcers and many types of gastric cancers (1). In the epithelium, this bacterium induces an intense inflammatory response, including oxidative toxic molecule production. In response to H. pylori infection, activated neutrophils are the primary sources of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (2). These cells respond to H. pylori antigens like NapA and CagA by expressing NADPH oxidases that catalyze the formation of superoxides. Dismutation of superoxides generates hydrogen peroxide (H2O2),2 while inducible nitric-oxide synthase produces nitric oxide. The combination of H2O2 with nitric oxide results in the formation of highly toxic peroxynitrite (ONOO−). In addition, H2O2 is the substrate for production of other reactive oxygen species; these include highly reactive hydroxyl radicals and HOCl. HOCl is reported to be 100-fold more toxic than H2O2 (2), and its concentration can reach up to 5 mm at inflammatory sites (3). The battery of oxidants described above are able to oxidize virtually all large molecules, including DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids (4, 5). To combat these potent oxidants, H. pylori is equipped with an array of antioxidant and macromolecule repair enzymes (5).

Because of their abundance and reactivity, proteins are a primary target for oxidative damage. Two types of oxidative protein modifications have been described, covalent modifications of amino acids and loss of secondary structure. Although a variety of covalent modifications to amino acids have been reported, Met and Cys residues are known to be primary oxidative targets under physiological conditions (6). Met residues in particular have high reactivity to HOCl, with a second-order rate constant reported to be 3.8 × 107 m−1 s−1 (6). Oxidation of Met leads to formation of Met-SO, and further oxidation results in Met sulfone (7). In some instances, Met-SO formation was found to be associated with changes in surface polarity and subsequent unfolding of proteins (8, 9). The peptide repair enzyme Msr can reductively repair Met-SO to Met (10). Two roles for Msr-mediated repair have been described. First, continual oxidation and reduction of surface Met residues in proteins are thought to act as a turnover sink to quench oxidants (11, 12). Second, Msr-mediated repair results in return of enzyme function (13, 14).

In bacteria, two types of Msrs (MsrA and -B) have been described that use S and R epimers of Met-SO as substrates, respectively (15). In H. pylori, MsrA and -B are fused and constitute a single protein. An H. pylori msr strain is highly sensitive to oxidative stress and is deficient in stomach colonization (16). Moreover, using a cross-linking approach, site-specific recombinase, GroEL, and catalase were identified as Msr-interacting proteins in H. pylori (17). In addition, a tripartite complex formed of catalase, Msr, and GroEL was observed (17). Catalase is a key antioxidant protein that dissipates H2O2 by decomposing it to H2O and O2. H2O2 itself is not highly toxic, but as it is produced in large amounts during the inflammatory cell respiratory burst and is a precursor for hydroxyl radical and HOCl formation, catalase enhances survival of nearly all animal pathogens. In H. pylori, catalase is one of the most abundant proteins (constitutes ∼4–5% of the total proteins, described herein), and it has some unique properties. Its unusual characteristics include a high pI (>9.0) (18) and high resistance to H2O2 (19). Although an H. pylori catalase mutant (katA) strain is viable in vitro under nonoxidative stress conditions, catalase activity has been shown to be associated with the resistance of the bacterium to professional phagocytes and macrophages (20, 21). Notably, an H. pylori catalase-deficient mutant strain is compromised in persistent mouse stomach colonization ability (22).

In this study, we sought to evaluate the role of Msr in repairing HOCl-oxidized Met residues in catalase and to further assess its functional significance. By using tandem MS/MS along with other biochemical techniques, we show that HOCl damages H. pylori catalase by oxidation of specific Met residues, leading to structural changes and loss of catalytic activity. However, Msr and GroEL function in a cooperative manner to repair oxidatively damaged catalase and restore some enzyme activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

msr and catalase gene deletion mutant strains (msr and katA strains) were constructed in H. pylori strain SS1 (SS1) background. The genes were inactivated by inserting antibiotic resistance cassettes (kanamycin and chloramphenicol for Msr and catalase, respectively) as described previously (16, 19). H. pylori strains were grown in Brucella agar (BD Biosciences) plates containing 10% defibrinated sheep blood (Quad Five, Ryegate, MT). Plates were incubated microaerobically in a humidified chamber at 37 °C under 5% CO2, 2% O2 with the balance as N2. Escherichia coli cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani broth or agar. Ampicillin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol were included in the media at final concentrations of 100, 30, and 30 μg/ml, respectively, for selection purposes (when needed). H. pylori cells were harvested from the plates as described earlier (19).

Protein Purification

Native catalase was purified by sequential use of cation and size exclusion chromatography from extracts of less than 2-day plate-grown SS1 cultures. H. pylori Msr, thioredoxin1 (trx), and thioredoxin reductase (trxR) were expressed and isolated from E. coli according to previously published protocols (17). Recombinant GroEL/GroES were purchased from Sigma. Purity and concentrations of the proteins were determined by SDS-PAGE (23), and a total protein estimation kit (Pierce® BCA protein assay kit). All proteins were stored at −80 °C in aliquots until analysis.

Estimation of Catalase Activity

Catalase activity was determined spectrophotometrically by following the dissipation of H2O2 at 240 nm as described previously (19).

Sensitivity of SS1, msr, and katA Strains to HL-60 Cells

Promyelocytic HL-60 cells were procured from ATCC (catalogue no. CCL-240TM) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (obtained from various sources, HyClone and Invitrogen) and 1% each of penicillin and streptomycin (HyClone). Cells were propagated in T-75 flasks (Falcon) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2, 20% O2 with balance as N2. Cell density was maintained between 105 and 106/ml by propagating cells into fresh media as required (typically every 5–7 days). For differentiation into neutrophil-like cells, cultures were incubated in the media containing 1.75% dimethyl sulfoxide for 3 days. For infection, differentiated cells were washed and seeded in 12-well tissue culture plates (at the rate of 5 × 106 cells/well in a 500-μl volume) in the same media without antibiotics and incubated overnight in the controlled gas incubator. To these cells, less than 2-day grown SS1, msr, or katA strain cultures were added in 500 μl of the same cell culture media (RPMI) at a multiplicity of infection of 1:50 (cell/bacteria). Infection was initiated by centrifugation of the cell mixture at 250 × g for 10 min, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C in the 2% O2 atmosphere described above. At various time points, the supernatant solution was collected and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min. Saponin (0.1% w/v in PBS) was used to lyse HL-60 cells to obtain surviving H. pylori (21). It was added to the cell pellet and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. Bacterial suspensions were serially diluted and plated on blood agar plates (24). Colonies were enumerated after 5–7 days of incubation (24).

Exposure of SS1 and msr Strains to HOCl and Measurement of Catalase Activity

Less than 2-day grown SS1 and msr strain cultures were suspended in MHB (+ 6% FBS) and adjusted to 108 colony-forming units/ml. The cultures were then exposed to 2.5 mm HOCl in sealed serum bottles at 2% O2, 10% H2, 5% CO2, and the balance of gas was N2. After incubation for 4 h at 37 °C, cells were lysed, and catalase activity was determined.

Oxidation of Purified Catalase

Many studies have employed H2O2 (9, 13, 25) to oxidize Met residues in proteins, and to study subsequent Msr-mediated repair, we previously observed that H. pylori catalase can tolerate huge amount of H2O2 without activity loss (19). Therefore, we used HOCl, ChT, and ONOO− to oxidize catalase. HOCl (available as sodium salt-free chlorine ≤4%) and ChT were purchased from Sigma. ONOO− was procured from EMD Biosciences. Stocks of HOCl and ONOO− were diluted in 0.1 n NaOH, and concentrations were determined by monitoring absorbance at 290 and 302 nm, respectively (molar extinction coefficient 350 and 1670 liter mol−1 cm−1 for −OCl and ONOO−, respectively) (26, 27). The oxidation treatment was carried out in Buffer A (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 50 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2), and 10 μm of catalase was mixed with various fold excess of oxidants as indicated in the figures. Following 15 (HOCl) or 30 (ONOO−/ChT) min of incubation at room temperature, oxidants were quenched by excess Met (5 mm final) for 10 min (14). To address possible ONOO− breakdown over the 30 min, catalase was also treated with a total of 200-fold excess of ONOO− in 10 equal aliquots (20-fold excess each time) injected at 3-min intervals (28). Other control experiments were conducted whereby catalase was incubated with various fold excesses of H2O2 or sodium nitrite as indicated in the figures.

Repair of Catalase

DTT was procured from Pierce. ATP and NADPH were obtained from Sigma. HOCl-treated samples were repaired with Msr (1-fold molar excess relative to catalase) and/or GroEL/ES (2-fold molar excess relative to catalase) or buffer in the presence of 400 μm NADPH, 5 μm trx, 100 nm trxR, 5 mm ATP, and 100 μm DTT at 37 °C for 1 h.

Mass Spectrophotometry-Trypsin or Asp-N Endoproteinase (Asp-N) Digestion

Catalase was incubated in trypsin (50 mm ammonium bicarbonate, 5 mm DTT, pH 7.8, at 80 °C for 30 min) or Asp-N (50 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 mm zinc acetate, pH 8.0, 10 mm DTT, at 60 °C for 45 min) digestion buffer. The samples were then cooled to room temperature and digested with sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega) or Asp-N (Pierce) overnight at 37 °C. Proteases were used at a ratio of 1:100 (protease/catalase). After digestion, samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

MS Pseudo-MRM

Digested catalase samples were analyzed using the LTQ front end of an LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an Agilent 1100 HPLC system with CaptiveSpray ionization using an Advance Ion Source for Thermo MS (Michrom Bioresources Inc.) Reversed phase LC was performed using an in-line C18 trapping cartridge to desalt, followed by separation on a capillary C18 column (Michrom Bioresources, 0.2 × 50 mm, 3 μm, 200 Å) using a linear gradient from 95% Buffer A (water, 0.1% formic acid) and 5% Buffer B (acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) to 40% Buffer A, 60% Buffer B. The flow rate was 3 μl/min for 70 min. Transitions for quantitation by pseudo-MRM analysis were determined by multiple runs of data-dependent LC-MS/MS (nine MS/MS events per survey scan, a maximum of four fragmentation events per precursor mass, and an exclusion window of 5 min), followed by screening with MASCOT (Matrix Science) to detect catalase peptides, manual interpretation of tandem MS/MS spectra, and manual selection of transitions to maximize selectivity and sensitivity in the pseudo-MRM experiments.

For pseudo-MRM analysis, the precursor ions for each transition were entered into an include list for data-dependent acquisition in Xcalibur. The LTQ was configured to continue scanning in MS mode until it detected a precursor ion on the include list with a normalized signal level of at least 500 counts/spectrum, at which point the LTQ would isolate and fragment up to nine such precursor ions before performing another MS survey scan. The normalized collision energy for all MS/MS acquisitions was set at 35 V. Post-acquisition, the data were filtered by precursor scan for each transition, and the selected ion chromatogram for the appropriate product ion for the selected precursor was plotted to generate the pseudo-MRM chromatograms. To analyze for the percent of oxidation for a specific methionine residue, the area of the oxidized peak in a base peak chromatogram was divided by the total area of the oxidized and unoxidized peaks. In all cases, the full MS/MS spectra were manually inspected to ensure that the quantitated peak represented the appropriate peptide, as well as to verify the site of oxidation to the suspected methionine residue.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

CD spectra were acquired on a Jasco J-715 circular dichroism spectrophotometer using a 1-mm path length quartz cuvette (Starna Cells, Inc.). Spectra were obtained at room temperature in an O2-free environment (chamber was continuously flushed with N2). After oxidation and quenching, catalase samples were dialyzed against 5 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, and adjusted to 200 μg/ml. Blank spectra were obtained using the 5 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. Samples were scanned from 190 to 250 nm (far-UV CD) at a speed of 100 nm/min and analyzed by manual comparison of CD spectra using the Jasco Spectra Manager software.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Catalase samples were loaded onto a HiLoadTM 16/60 SuperdexTM 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). The column was developed at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min; chromatograms were integrated and analyzed using Unicorn 5.01 software. Molecular weights were determined by running a standard molecular weight determination kit (Sigma).

Detection of Carbonyl Groups

Carbonyl groups were detected by OxyBlotTM protein oxidation detection kit (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) with slight modifications. Briefly, carbonyls in the catalase were derivatized with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine. About 0.6 μg of derivatized catalase was separated on an SDS gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Following blocking, the membranes were incubated in rabbit anti-dinitrophenyl antibody (1:150 in PBS-T). After several washes, membranes were incubated in goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Bio-Rad). After 2 h of incubation, blots were washed extensively and developed with nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (29).

Quantitation of Catalase in H. pylori Crude Lysate

Less than 2-day grown SS1 cultures were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed by sonication. Ten micrograms of protein lysates (determined by Pierce BCA assay kit) containing all cell proteins were loaded onto SDS gels. Relative quantity of the catalase band was calculated by loading known amounts of pure enzyme to adjacent lanes and comparing bands by densitometry after staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

RESULTS

Combating oxidative stress is important to H. pylori survival both in vivo and in vitro. Consistent with this, we found that catalase composed about 4–5% of total cell proteins. Also, studies on gene deletion mutants indicate that both Msr and catalase are important for mouse stomach colonization by H. pylori (16, 22).

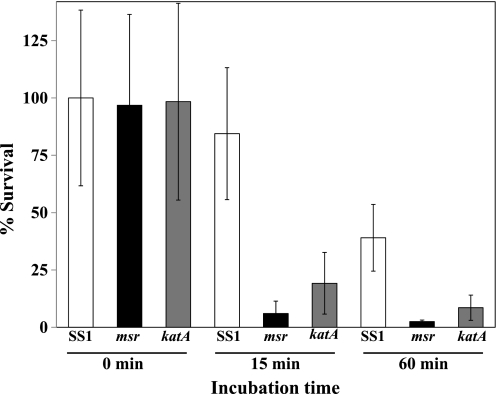

Sensitivity of msr and katA Strains to HL-60 Cells

Neutrophils are the primary phagocytes recruited in response to H. pylori infection (2), and they produce HOCl as a principal anti-microbial oxidant (3, 30). Because of a deficiency in the ability to repair Met-SO in proteins, including catalase, an msr strain might show hypersensitivity to neutrophil-mediated killing. Differentiated HL-60 cells were used as the source of oxidant in the killing assays. These cell lines are rich in the key HOCl-generating enzyme, myeloperoxidase, which constitutes about 5% of the total HL-60 cellular proteins (31). Moreover, in terms of physical characteristics as well as in biological activities, myeloperoxidase from these cells is similar to human neutrophils (31). To determine the relative contribution of catalase versus its repair enzyme Msr, we included both a katA and an msr strain to compare with the parent, in these killing assays. As presented in Fig. 1, HL-60 cells killed most of the msr strain (∼94%) and likewise the bulk of the katA strain (∼81%) within 15 min, whereas ∼16% of parent SS1 died by the same HL-60 exposure. After 60 min of incubation, most of the mutant bacteria were not viable (∼98% of msr and ∼92% of katA), whereas ∼61% of parent SS1 was not viable. However, both msr and katA strains were more susceptible (p < 0.001, Student's t test) to killing by HL-60 cells than the parent SS1; still the difference in sensitivity between the two mutant strains (msr versus katA) was statistically significant (p < 0.04). Therefore, Msr plays some other roles in aiding H. pylori survival in addition to catalase repair. This is expected as other repair targets should be present in H. pylori (17).

FIGURE 1.

Survivability of SS1, msr, and katA derivative strains from SS1 to differentiated HL-60 cells. Cells were infected with bacteria at a multiplicity of infection of 1:50. At the times indicated, the HL-60 cells were lysed, and the suspensions were serially diluted and plated onto blood agar plates. Colonies were enumerated after incubation of the plates at 2% O2 for 5–7 days. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). The two mutant strains were significantly less viable than SS1 at both 15 and 60 min post-exposure (p < 0.001), although the mutant strains differed from each other at p < 0.04.

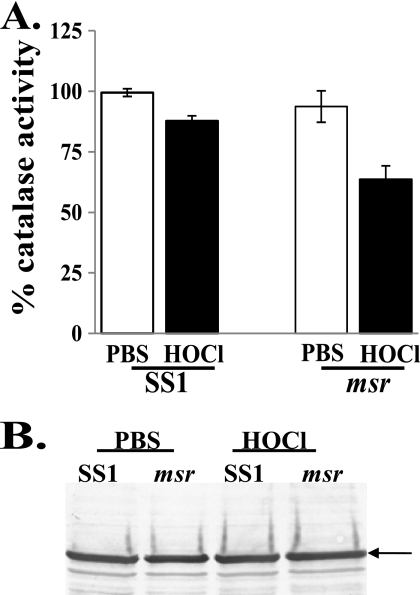

Catalase Activity in SS1 and msr Strains following HOCl Treatment

We previously observed that catalase activity of an msr strain is more susceptible to O2-related damage (17). We speculated that Msr might play an important role in maintaining catalase activity when H. pylori is under HOCl stress. Thus, we incubated SS1 and msr strains with HOCl (in a low O2 atmosphere) and then measured the resulting catalase activities from crude extracts. The activity of the msr strain was significantly decreased (to ∼60%) following HOCl treatment, whereas catalase activity was not damaged in the parent SS1 strain (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Catalase activity and expression in SS1/msr strains following HOCl treatment. A, parent strain SS1 or the msr derivative from SS1 was incubated with HOCl for 4 h at 2% O2, and catalase activities were determined in crude lysates. Catalase activity of SS1 + PBS was considered as 100%. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 4). B, expression of catalase following 4 h of HOCl treatment. Lysates (10 μg of protein each) were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using anti-catalase antibodies. The immunoreactive band is indicated by the arrow.

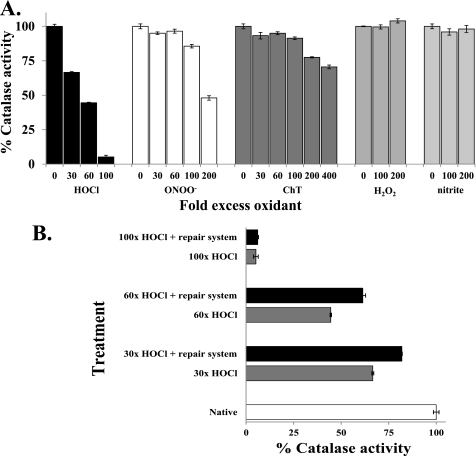

Catalase Activities in Oxidized and Repaired Samples

Various oxidants were tested for their ability to damage H. pylori catalase. First, we evaluated the effect of HOCl on purified catalase. As presented in Fig. 3A, HOCl destroyed catalase activity in a dose-dependent fashion. After incubation of 10 μm catalase with 30-, 60-, and 100-fold (i.e. 300, 600, and 1000 μm) molar excess of HOCl for 15 min, the remaining catalase activities were ∼66, 44, and 5%, respectively, compared with untreated samples. ONOO− is another key nitrosative stress agent produced by inflammatory cells, and ChT is a milder oxidant but one that preferentially oxidizes Met residues (32). As shown in Fig. 3A, these oxidants were not as effective at inhibiting catalase as HOCl; a higher molar excess of ONOO− or ChT as well as a longer incubation were required to adversely affect catalase activity. After 30 min of incubation with 200- and 400-fold molar excess of ONOO− and ChT, the remaining catalase activities were ∼48 and 70%, respectively, compared with untreated enzyme. ONOO− is unstable at neutral pH, so stock solutions were maintained in NaOH. After 30 min of catalase incubation with 200-fold excess ONOO−, the pH was 9.2. Nevertheless, possible oxidant breakdown was addressed; sequential multiple aliquot (as described under “Experimental Procedures”) injections of the oxidant to ensure that “fresh” ONOO− was continuously present were done, similar to the procedure of Lancellotti et al. (28). Under this regime, treatment of catalase with ONOO− gave almost the same levels of catalase inactivation as the single shot method (data not shown). Therefore, breakdown of ONOO− is not the reason for the original observation of lower catalase sensitivity. Commercial ONOO− is often contaminated with peroxide and nitrite, so controls are important to interpret oxidation effects of these potential contaminants (33). However, treatment of catalase with H2O2 or sodium nitrite did not affect enzyme activity (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

A, oxidant destruction of H. pylori catalase activity in a dose-dependent fashion. 10 μm catalase was incubated with the indicated fold excess of oxidant for 15 (HOCl) or 30 min (ONOO−, ChT, H2O2, and nitrite), and excess oxidants were quenched by adding excess l-Met. Catalase activities were measured spectrophotometrically by dissipation of H2O2 and presented as % of nonoxidized samples. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. from four independent assays. B, role of Msr and GroEL in repairing HOCl-damaged catalase. HOCl-treated samples were repaired with Msr (1-fold molar excess relative to catalase) and GroEL/ES (2-fold molar excess to catalase) or with buffer only but in the presence of 400 μm NADPH, 5 μm trx, 100 nm trxR, 5 mm ATP, and 100 μm DTT at 37 °C for 1 h. Addition of GroEL/ES components or Msr components alone resulted in not more than 5% activity recovery. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 4).

As we observed the largest damaging effect on catalase activity by HOCl, and Met residues are the primary targets of this oxidant, we investigated a role of Msr in repair of HOCl-damaged catalase. We examined the potential role of Msr in conjunction with GroEL/ES (in the presence of trx-trxR system) to reactivate HOCl-damaged catalase (Fig. 3B). Incubation of oxidized catalase with Msr components (Msr, NADPH, trx, trxR, and DTT) or GroEL/ES components (GroEL/ES, ATP, and DTT) alone had little ability to recover enzyme activity (from many experiments less than 5% activity recovered compared with the oxidant-damaged enzyme, data not shown). However, Msr components in combination with GroEL/ES augmented the activity recovery (Fig. 3B). Compared with the unoxidized sample (but still containing the repair mixture of all the Msr and GroEL/ES components, taken as 100%), the activity recoveries were ∼82 and 62%, respectively, in the case of 30- (30×) and 60-fold (60×) HOCl treatments, respectively. These values represent modest but significant (24 and 41%, respectively) activity recovery compared with the oxidant-damaged enzyme. However, the Msr plus GroEL components were not able to restore activity of the most damaged (100-fold excess HOCl treated) catalase.

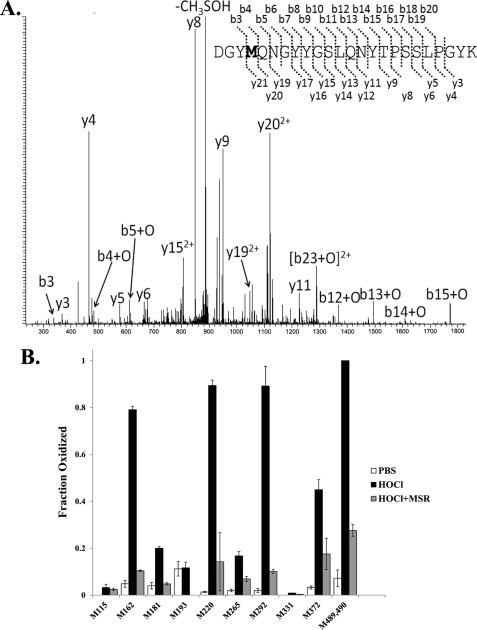

MS/MS Identification of Met Residues in Catalase

Catalase samples were digested with trypsin or separately with Asp-N, and the resulting peptide mix was then subjected to LC-MS/MS. A representative MS/MS spectrum is displayed in Fig. 4A; it shows b- and y-type product ions of the tryptic peptide 369–392 of 60× HOCl-treated catalase. Fragment ions shifted by the mass of one oxygen are indicated by a +O annotation, which can be mapped to a single oxidation event on Met372. Individual Met residues on each peptide were analyzed for their native or oxidized (+O) status, and percent oxidations were quantitated by calculating the peak area from pseudo-MRM transitions specific to the peptide. Although many Met residues (Met181, Met265, Met292, and Met372) were detected in both enzymatic digests (Table 1), several residues were detected specifically in Asp-N (Met115, Met331, Met489, and Met490) or trypsin (Met162, Met193, and Met220) digestions. Therefore, the use of these two enzymes augmented Met-containing peptide detection, enhancing overall sequence coverage. At the same time, we were able to rigorously assess the oxidation status of Met residues that were recovered by both proteases.

FIGURE 4.

A, MS/MS spectrum of peptide 369–392 following trypsin digestion of previously 60× HOCl-treated catalase. Fragmentation pattern of peptide 369–392 is displayed. The designation +O on b- and y-ions represents addition of 16 Da to the predicted product ion of the unoxidized peptide, consistent with the addition of one oxygen atom to Met372. B, identification of Met residues after oxidation and repair of catalase. 10 μm catalase was incubated with 60× HOCl for 15 min, and excess oxidant was quenched by adding excess l-Met. Following dialysis-based removal, oxidized samples were incubated with Msr in the presence of DTT. Samples were digested separately with trypsin or Asp-N, and Met residues were identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS.

TABLE 1.

MS/MS sequence coverage of Met residues in catalase following trypsin and Asp-N digestion

Met residue number is the location of Met in the catalase sequence, and + means that particular Met was observed from the corresponding enzymatic digestion.

| Met residue | Trypsin | Asp-N | Met residue | Trypsin | Asp-N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met-1 | − | − | Met-292 | + | + |

| Met-115 | − | + | Met-331 | − | + |

| Met-162 | + | − | Met-372 | + | + |

| Met-181 | + | + | Met-489 | − | + |

| Met-193 | + | − | Met-490 | − | + |

| Met-220 | + | − | Met-493 | − | − |

| Met-265 | + | + | Met-498 | − | − |

Out of 14 Met residues in catalase, we detected 11 residues. We were not able to identify N-terminal Met (possibly because of post-translational processing) and the two most C-terminal Met residues (Met493 and Met498) (probably because of the very small size of the peptides in both tryptic and Asp-N digests). Fractional oxidations for individual Met residues are presented in Fig. 4B. In native “as purified” catalase, oxidations of these Met residues were negligible (near to base line). Following 60× HOCl treatment, oxidations of Met162, Met220, Met292, Met489, and Met490 reached to ∼90–100%. Met372 was ∼50% oxidized, and other Met residues were not heavily oxidized. All identified Met residues were either distributed on different peptides or distinguishable by prominent fragmentation ions between the two Met residues except for Met489 and Met490; these were located on the same peptide (amino acid 472–491) in the Asp-N digest, and the product ion spectra of this peptide revealed no abundant fragmentation product occurring in the one peptide bond between the two Met residues, so only their collective oxidation status could be measured. Incubation of oxidized catalase with the Msr in the presence of 10 mm DTT (DTT can act as an in vitro reductant for Msr) (34) reduced most of the oxidized Met residues close to the base-line nonoxidant treated levels (Fig. 4B). In the case of 400× ChT treatment, we observed the oxidation and repair of the same Met residues that were oxidized by HOCl, but their overall oxidation was about 20–40% less than with HOCl (data not shown). In the ONOO−-treated sample, we did not observe significant Met oxidation (data not shown).

Next, we attempted to explore the correlation between surface exposure of Met residues in catalase and their susceptibility to oxidation. We calculated surface accessibility of the sulfur center of all of the Met residues based on the x-ray crystal structure of H. pylori catalase (Protein Data Bank code 1QWL) (35). We observed that Met162, Met292, Met372, Met489, and Met490 are calculated to be the most surface-exposed Met residues in catalase (Table 2) as well as the ones most vulnerable to oxidation (Fig. 4B). Nonexposed Met residues showed little or no oxidation. The only exception was Met220, as this residue was oxidized but not predicted to be localized on the catalase surface. This apparent discrepancy may be due to protein dynamics in the region of Met220, which are not probed by a static crystal structure, causing Met220 to be more solvent-exposed than the crystal structure would indicate.

TABLE 2.

Solvent accessibility of individual catalase Met residues

All solvent accessibility measurements are based on the average of the two subunits in the x-ray crystal structure, Protein Data Bank code 1QWL. SASA means solvent-accessible surface area. Average oxidation is the fraction of oxidized Met residues as identified by MS/MS following incubation of catalase with 60× HOCl.

| Met residue | Average sulfur SASA (Å2) | Average oxidation | Met residue | Average sulfur SASA (Å2) | Average oxidation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met-115 | 0 | 0.03 | Met-292 | 14.25 | 0.89 |

| Met-162 | 1.59 | 0.79 | Met-331 | 0.165 | 0.01 |

| Met-181 | 0.47 | 0.2 | Met-372 | 38.55 | 0.45 |

| Met-193 | 0 | 0.12 | Met-489 + Met-490 | 7.81 | 1 |

| Met-220 | 0 | 0.89 | |||

| Met-265 | 0 | 0.17 |

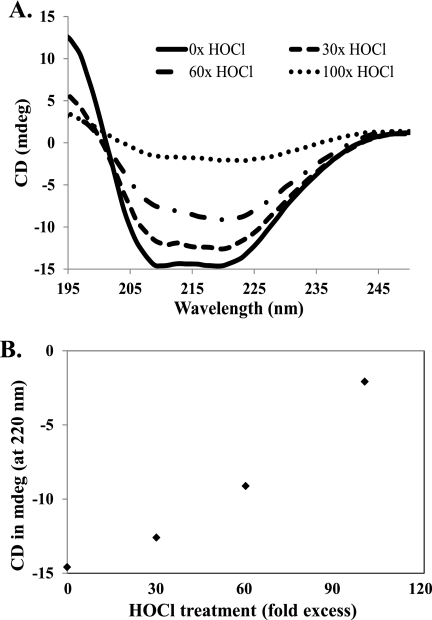

Structural Changes in Catalase following HOCl Treatment

Several studies have demonstrated unfolding (36, 37) or oligomerization (38–40) of proteins following oxidant treatment. For example, a recent study described secondary structure destabilization and unfolding of apolipoprotein A-I as a consequence of Met oxidation (9). CD spectra of catalase following HOCl treatment is presented in Fig. 5A. Our deconvoluted secondary structure composition of nonoxidized (not HOCl treated) catalase was 29% α-helix and 21% β-sheet. The observed secondary structure pattern is in good agreement with the reported x-ray crystal structure of H. pylori catalase (Protein Data Bank code 1QWL), which has 32% helical and 16% β-sheet. For protein stability assessments, CD is typically followed at 220 nm, whereby an increase in ellipticity (millidegree) indicates loss of secondary structure. After treatment with increasing concentrations of HOCl, we observed an increase in the ellipticity at 220 nm, which is near a local minimum for both α-helix and β-sheet but near a maximum for random coil (Fig. 5A). This progressive increase in ellipticity at 220 nm nicely correlated with the added HOCl amount (Fig. 5B), suggesting a dose-dependent loss of catalase structure. Furthermore, we have noticed a strong positive correlation between secondary structure content as measured by negative CD values at 220 nm (Fig. 5B) and catalase activity (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 5.

Far-UV CD spectra of catalase treated with various fold excesses of HOCl. A, catalase was incubated with the indicated molar fold excess of HOCl for 15 min, and oxidant was quenched by addition of excess l-Met. Following dialysis, samples were adjusted to 200 μg of protein/ml (see text) and scanned from 195 to 250 nm. B, correlation between HOCl concentrations and CD ellipticity values (millidegree) at 220 nm.

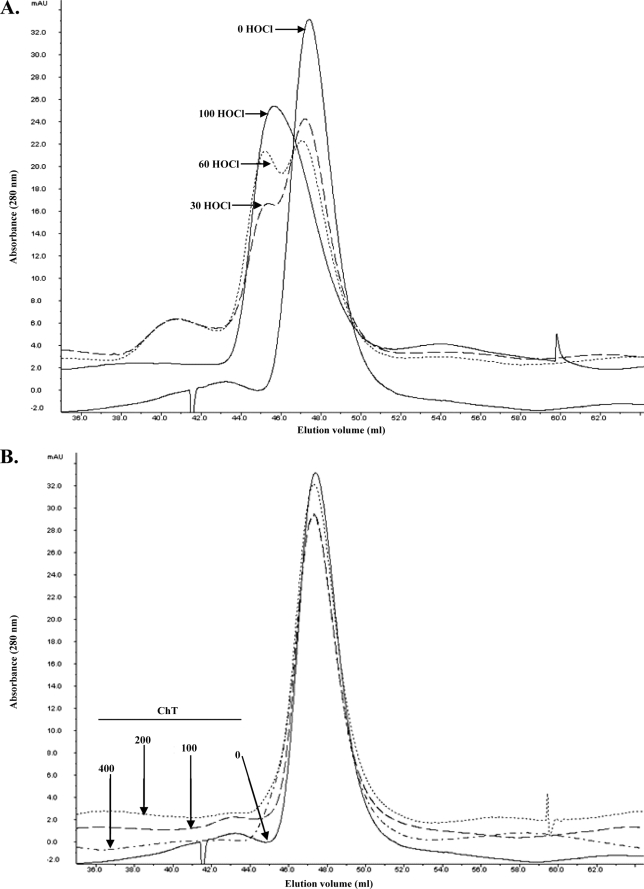

We used gel permeation chromatography to estimate the size of catalase protein fractions upon oxidation. As presented in Fig. 6A, HOCl induced oligomerization of catalase in a dose-dependent manner. Native as purified catalase gave one peak with a molecular mass of ∼190–200 kDa. This observed molecular mass represents the catalase tetramer and is in agreement with an earlier reported mass of H. pylori catalase (18). HOCl treatment gave an additional peak at ∼400 kDa. In addition, after 30 and 60× HOCl treatments, about 8% of the total catalase eluted at a size of >2000 kDa. Following 30, 60, and 100× HOCl treatments, the remaining native catalase tetramer (∼190–200 kDa) was sequentially diminished to ∼68, 54, and 0%, respectively, of the nonoxidized samples. Interestingly, ChT did not induce oligomerization of catalase (Fig. 6B). We also ran the oxidized samples on SDS gels under reducing conditions. In nonoxidized samples, catalase migrated at about 55 kDa. Treatment of catalase with increasing concentrations of HOCl led to its progressive oligomerization (i.e. loss of 55-kDa species). In 100× HOCl-treated samples the 55-kDa monomeric band was nearly absent, and large molecular weight species appeared (data not shown). These results indicate that the HOCl-induced oligomerization of catalase is probably due to a noncovalent cross-linking event that does not solely consist of disulfide bond formation.

FIGURE 6.

HOCl treatment causes oligomerization of catalase. Gel filtration chromatography of catalase following HOCl (A) or ChT (B) treatments. After oxidation and quenching, catalase samples were subjected to gel filtration chromatography. Chromatograms were integrated and analyzed using Unicorn 5.01 software.

HOCl treatment of catalase also produced carbonylation that was detected by OxyBlot stains of SDS gels. 60 and 100× HOCl-treated catalase yielded about equal total carbonylation that was evident among all the separated species (i.e. 55 kDa and oligomers, data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Successful colonization by H. pylori depends in part upon the ability of the bacterium to combat oxidative stress. The repertoire of antioxidant proteins together constitutes a significant proportion of the total H. pylori protein profile (5). Mutant strains in most of the antioxidant genes are viable in vitro under nonoxidative conditions but are defective in mouse stomach colonization abilities (5). Among the possible macromolecule targets, proteins are a primary one for oxidative damage (6). Although degradation followed by replacement via new synthesis (protein turnover) is an obvious direct approach to replenish oxidatively damaged proteins, repair of damaged proteins is expected be less energetically expensive and a more rapid approach than de novo synthesis. Thus protein repair systems can provide a means to survive under stress conditions, and pathogens in particular are adept at repair processes.

Met residues are considered to be primary targets of many oxidants, including the oxidants produced by host inflammatory cells (6). The role of Msr in higher organisms in repairing Met-rich proteins (13, 41–44) is well established, but few Msr targets have been reported in bacteria. They include GroEL and Ffh (12, 14, 25). Interestingly, we have observed up-regulation of Msr following subjection of H. pylori to oxidative stress, and three proteins that interact with Msr are catalase, GroEL, and SSR (17). A peptide repair system is especially important in some pathogens such as H. pylori as the bacterium is known both for its persistence and ability to elicit a robust inflammatory response.

Catalase is a key antioxidant protein that degrades H2O2. For example, we have observed much more carbonylation of H. pylori proteins (data not shown) as well as DNA damage (45) in a katA strain versus its parent upon exposure of both strains to oxidative stress. In H. pylori, catalase is expressed in relatively large amounts (4–5% of total protein), and the enzyme does not undergo up-regulation during oxidative stress (Fig. 2B). H. pylori has two described mechanisms devoted to maintaining catalase activity; in addition to the Msr-mediated repair described herein, we previously reported a role for the peroxiredoxin AhpC in protecting catalase against organic hydroperoxide-mediated inactivation (19). Our previously reported interaction of catalase with Msr was found to be dependent on the oxidation state of catalase, whereby previously oxidized enzyme (Met residues likely converted to Met-SO) interacted more readily with Msr (17). The Met content in catalase is unusually high (14 out of 505 residues, representing ∼3%) thus making it a good target for Met repair. We identified (Fig. 4B) six Met residues susceptible to HOCl oxidation and subsequent Msr-mediated repair. Interestingly, almost all (five out of these six) heavily oxidized Met residues are predicted to be exposed on the catalase surface (Table 2), consistent with previous data indicating that the rate of reaction of Met residues with various reactive oxygen species is directly dependent upon solvent accessibility of the reactive site (11, 46, 47). For other Msr repair targets, 12 (14) and 4 (25) Met residues were shown to undergo repair within the bacterial proteins GroEL and Ffh (a component of signal recognition particle), respectively.

At inflammatory sites, neutrophils produce high levels (up to 5 mm) of HOCl (3). Among the oxidants tested, HOCl caused the most damaging effect on catalase activity (Fig. 3A). The second-order rate constants (m−1 s−1) of HOCl for Met and Cys residues are ∼3.8 × 107 and 3.0 × 107, respectively (6). This high reactivity may explain the dramatic effect of HOCl on catalase activity and likely makes this oxidant a potent antibacterial agent generated by phagocytes. The high amounts of both catalases made by H. pylori and likewise the HOCl produced by the host may illustrate the evolving struggle between host and pathogen.

Although ONOO− destroyed catalase activity (Fig. 3A), much higher oxidants and a longer exposure time were required to achieve levels of inactivation (∼50%) similar to that achieved by HOCl (Fig. 3A). The second-order rate constant (m−1 s−1) of ONOO− is ∼102 and 103 for Met and Cys residues (48) and is lower than of HOCl by a magnitude of ∼105. Interestingly, we did not observe any significant Met-SO in ONOO−-treated catalase. Cys and Tyr residues were found to be modified in several ONOO−-inactivated enzymes (48). Nitration of Tyr predominates over Met oxidation following exposure of proteins to ONOO− under physiological conditions (49, 50). Sequence analysis revealed that H. pylori catalase has 25 Tyr and 2 Cys residues, so the major result of ONOO−-mediated catalase inactivation would be expected to be via Tyr nitration. In comparison with the parent strain SS1, the msr strain was much more susceptible to killing by HOCl than by ONOO− (data not shown), also indicating that Met residue oxidation may not be a primary ONOO− stress target in H. pylori.

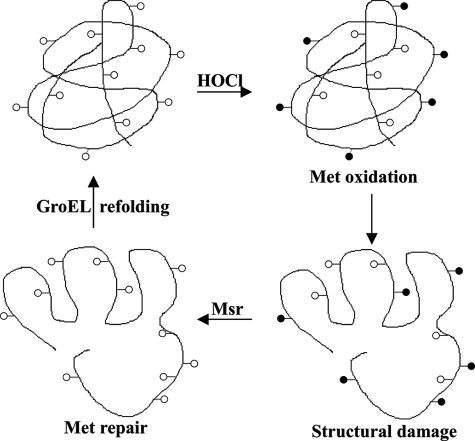

Loss of catalase secondary structure was associated with catalase activity damage. This likely explains the requirement of GroEL in recovering the activity of Msr-repaired oxidized catalase (Fig. 3B). Other studies reported oxidation-induced loss of secondary structure in several proteins (9, 36, 51, 52). A recent study suggested oxidative unfolding and consequent aggregation as a major mechanism of HOCl-mediated protein inactivation (40). As sulfoxides are more hydrophilic than Met residues, their formation can change the overall surface charge of a protein (8, 38). This destabilizing effect can lead to unfolding of the protein. Unless a chaperone for refolding comes into play, the damaged Met-SO-rich protein would be expected to be subject to aggregation and subsequent degradation. It is likely that Met-SO in catalase first needs to be repaired before the process of chaperone-mediated refolding can be accomplished; thus the three component system is required (see Fig. 7). GroEL/ES and DnaK/DnaJ are primary chaperones dedicated to protection against stress-induced protein aggregation (53). GroEL has been shown to protect bovine catalase against thermal stress (54). When plant catalase was expressed in E. coli, its activity level was augmented when accompanied with GroEL/ES coexpression (55). GroEL interacts with an estimated 300 E. coli proteins; many are essential ones for survival (56). Interestingly, GroEL is also a target of Met oxidation and Msr-mediated repair (14). Therefore, Msr apparently serves to protect catalase directly as well as indirectly via repair of the chaperone.

FIGURE 7.

Proposed model indicating roles of Msr and GroEL in repairing HOCl-damaged catalase. Host-generated oxidants such as HOCl oxidize Met residues in catalase that leads to unfolding. However, Msr converts Met-SO to Met residues, but GroEL is required for proper folding to aid activity recovery.

We observed a significant number of Met-SO residues that undergo repair (Fig. 4B) and a significant activity recovery of 30 and 60× HOCl-treated catalase by adding a combination of both the Msr and GroEL systems (Fig. 3B). Still the activity recovery was partial suggesting some other (severe) modifications of catalase as a result of HOCl treatment. Although we observed HOCl-mediated carbonyl formation (data not shown) and oligomerization of catalase (Fig. 6), we did not observe any significant heme modification based on spectral assays (data not shown). HOCl-induced protein radicals, carbonyl formation, and subsequent oligomerization of eukaryotic catalase was reported (39); although heme was postulated to be a primary site to promote oxidative damage, the heme group itself was not significantly modified following prolonged exposure of catalase to HOCl (39). A separate study observed severe carbonylation and oligomerization of heme-depleted apomyoglobin following HOCl treatment (38), indicating that the heme group may not be necessary for HOCl-mediated carbonylation and oligomerization.

Our data demonstrate that HOCl rapidly oxidized six Met residues in catalase, introduced structural changes, and subsequently caused activity loss (Figs. 3A, 4B, 5, and 6). Msr repaired these Met-SO residues, but activity recovery required the GroEL system (Figs. 3B, 4B, and 7). Our experiments also suggest that both Msr and catalase enhance survival of H. pylori against HOCl-producing neutrophils. Although Msr aids H. pylori survival by protecting catalase, it plays additional protective roles that aid bacterial survival in the presence of neutrophils. Identifying the importance of these repair targets in comparison with the catalase target will help us to further understand the roles of Msr.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Benoit for help in protein purification and G. Wang for providing katA strain. We also thank Dr. Jeffrey Urbauer for use of the circular dichroism spectrophotometer. J. S. S. acknowledges support for analytical instrumentation used in this study from National Institutes of Health Grant RR005351 from the NCRR.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 AI077569.

- H2O2

- hydrogen peroxide

- HOCl

- hypochlorous acid

- Met-SO

- methionine sulfoxide

- Msr

- methionine sulfoxide reductase

- ChT

- chloramine-T

- ONOO−

- peroxynitrite

- trx

- thioredoxin1

- trxR

- thioredoxin reductase

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring.

REFERENCES

- 1. Algood H. M., Cover T. L. (2006) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 597–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Handa O., Naito Y., Yoshikawa T. (2010) Inflamm. Res. 59, 997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss S. J. (1989) N. Engl. J. Med. 320, 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanaka M., Chock P. B., Stadtman E. R. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 66–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang G., Alamuri P., Maier R. J. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 61, 847–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hawkins C. L., Pattison D. I., Davies M. J. (2003) Amino Acids 25, 259–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weissbach H., Etienne F., Hoshi T., Heinemann S. H., Lowther W. T., Matthews B., St, John G., Nathan C., Brot N. (2002) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397, 172–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chao C. C., Ma Y. S., Stadtman E. R. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2969–2974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong Y. Q., Binger K. J., Howlett G. J., Griffin M. D. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1977–1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boschi-Muller S., Gand A., Branlant G. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 474, 266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luo S., Levine R. L. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 464–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abulimiti A., Qiu X., Chen J., Liu Y., Chang Z. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cao G., Lee K. P., van der Wijst J., de Graaf M., van der Kemp A., Bindels R. J., Hoenderop J. G. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26081–26087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khor H. K., Fisher M. T., Schöneich C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19486–19493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ezraty B., Aussel L., Barras F. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1703, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alamuri P., Maier R. J. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1397–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alamuri P., Maier R. J. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188, 5839–5850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hazell S. L., Evans D. J., Jr., Graham D. Y. (1991) J. Gen. Microbiol. 137, 57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang G., Conover R. C., Benoit S., Olczak A. A., Olson J. W., Johnson M. K., Maier R. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51908–51914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramarao N., Gray-Owen S. D., Meyer T. F. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 38, 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basu M., Czinn S. J., Blanchard T. G. (2004) Helicobacter 9, 211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harris A. G., Wilson J. E., Danon S. J., Dixon M. F., Donegan K., Hazell S. L. (2003) Microbiology 149, 665–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang G., Maier S. E., Lo L. F., Maier G., Dosi S., Maier R. J. (2010) Infect. Immun. 78, 4660–4666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ezraty B., Grimaud R., El Hassouni M., Moinier D., Barras F. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 1868–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morris J. C. (1966) J. Phys. Chem. 70, 3798–3805 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes M. N., Nicklin H. G. (1968) J. Chem. Soc. Series A, 450–452 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lancellotti S., De Filippis V., Pozzi N., Peyvandi F., Palla R., Rocca B., Rutella S., Pitocco D., Mannucci P. M., De Cristofaro R. (2010) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 446–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harlow E., Lane D. (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual, p. 598, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rosen H., Klebanoff S. J., Wang Y., Brot N., Heinecke J. W., Fu X. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18686–18691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hope H. R., Remsen E. E., Lewis C., Jr., Heuvelman D. M., Walker M. C., Jennings M., Connolly D. T. (2000) Protein Expr. Purif. 18, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Su Z., Limberis J., Martin R. L., Xu R., Kolbe K., Heinemann S. H., Hoshi T., Cox B. F., Gintant G. A. (2007) Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 702–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McLean S., Bowman L. A., Sanguinetti G., Read R. C., Poole R. K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20724–20731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lowther W. T., Weissbach H., Etienne F., Brot N., Matthews B. W. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loewen P. C., Carpena X., Rovira C., Ivancich A., Perez-Luque R., Haas R., Odenbreit S., Nicholls P., Fita I. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 3089–3103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Melkani G. C., Zardeneta G., Mendoza J. A. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294, 893–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hawkins C. L., Davies M. J. (2005) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18, 1600–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chapman A. L., Winterbourn C. C., Brennan S. O., Jordan T. W., Kettle A. J. (2003) Biochem. J. 375, 33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonini M. G., Siraki A. G., Atanassov B. S., Mason R. P. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42, 530–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Winter J., Ilbert M., Graf P. C., Ozcelik D., Jakob U. (2008) Cell 135, 691–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moskovitz J. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1703, 213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tsvetkov P. O., Ezraty B., Mitchell J. K., Devred F., Peyrot V., Derrick P. J., Barras F., Makarov A. A., Lafitte D. (2005) Biochimie 87, 473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brennan L. A., Lee W., Giblin F. J., David L. L., Kantorow M. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790, 1665–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grimaud R., Ezraty B., Mitchell J. K., Lafitte D., Briand C., Derrick P. J., Barras F. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48915–48920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang G., Conover R. C., Olczak A. A., Alamuri P., Johnson M. K., Maier R. J. (2005) Free Radic. Res. 39, 1183–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vogt W. (1995) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18, 93–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levine R. L., Mosoni L., Berlett B. S., Stadtman E. R. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 15036–15040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alvarez B., Radi R. (2003) Amino Acids 25, 295–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Berlett B. S., Levine R. L., Stadtman E. R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2784–2789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tien M., Berlett B. S., Levine R. L., Chock P. B., Stadtman E. R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7809–7814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sharp J. S., Sullivan D. M., Cavanagh J., Tomer K. B. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 6260–6266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Venkatesh S., Tomer K. B., Sharp J. S. (2007) Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 21, 3927–3936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Georgopoulos C. (2006) Genetics 174, 1699–1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hook D. W., Harding J. J. (1997) Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 380–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mondal P., Ray M., Sahu S., Sabat S. C. (2008) Protein Pept. Lett. 15, 1075–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lund P. A. (2009) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 785–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]