Abstract

Anemia of inflammation develops in settings of chronic inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic disease. In this highly prevalent form of anemia, inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, stimulate hepatic expression of hepcidin, which negatively regulates iron bioavailability by inactivating ferroportin. Hepcidin is transcriptionally regulated by IL-6 and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling. We hypothesized that inhibiting BMP signaling can reduce hepcidin expression and ameliorate hypoferremia and anemia associated with inflammation. In human hepatoma cells, IL-6–induced hepcidin expression, an effect that was inhibited by treatment with a BMP type I receptor inhibitor, LDN-193189, or BMP ligand antagonists noggin and ALK3-Fc. In zebrafish, the induction of hepcidin expression by transgenic expression of IL-6 was also reduced by LDN-193189. In mice, treatment with IL-6 or turpentine increased hepcidin expression and reduced serum iron, effects that were inhibited by LDN-193189 or ALK3-Fc. Chronic turpentine treatment led to microcytic anemia, which was prevented by concurrent administration of LDN-193189 or attenuated when LDN-193189 was administered after anemia was established. Our studies support the concept that BMP and IL-6 act together to regulate iron homeostasis and suggest that inhibition of BMP signaling may be an effective strategy for the treatment of anemia of inflammation.

Introduction

Anemia of inflammation (AI), also known as anemia of chronic disease (ACD), is the most prevalent form of anemia after iron-deficient anemia (IDA).1,2 AI frequently occurs in patients with a broad array of infectious, autoimmune, or inflammatory disorders, as well as cancer and kidney disease, and can contribute to the morbidity associated with these conditions.3 In contrast to IDA, AI is typically normochromic and normocytic with hemoglobin (Hb) levels greater than 8 g/dL; however, severe AI can lead to microcytosis.1,2 Patients with AI have diminished serum iron levels and transferrin saturations, whereas ferritin levels are normal or elevated.3 Erythropoietin levels are typically elevated, but lower than those seen in patients with a similar degree of anemia attributable to iron deficiency. While a mild degree of anemia may be tolerated in patients who are otherwise healthy, anemia in patients with cardiovascular or pulmonary disease can impair systemic oxygen delivery, thereby worsening angina or dyspnea, or reducing exercise tolerance. Moreover, anemia is associated with worsened prognosis in cancer,4 chronic kidney disease,5–7 and congestive heart failure.5,8,9 When treatment of the underlying disease is incomplete or not feasible, blood transfusions, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), and iron supplementation have been used to increase Hb levels in AI. However, there are known risks associated with blood transfusion, and iron supplementation in AI requires intravenous (IV) administration. Moreover, aggressive treatment with ESAs can increase the cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with kidney disease10 and may accelerate tumor progression in patients with cancer.11 Thus, additional therapeutic options are needed for patients with AI.

A common feature of the disorders associated with AI is immune activation and production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IFNγ. IL-6 is especially potent in regulating the expression of the peptide hormone hepcidin, a central regulator of systemic iron balance.12–15 Hepcidin binds to and initiates degradation of ferroportin-1, the sole elemental iron exporter in vertebrates. Loss of ferroportin-1 activity prevents mobilization of iron to the bloodstream from intracellular stores in enterocytes and reticuloendothelial macrophages, leading to hypoferremia and anemia,16,17 even in the presence of sufficient dietary iron.

BMP signaling has been demonstrated to have important roles in the regulation of hepatic hepcidin expression and serum iron levels.18–22 We previously used dorsomorphin, a small molecule inhibitor of BMP type I receptor kinases, to show that BMP signaling contributes to both iron- and IL-6–induced hepcidin expression and that BMP inhibition reduces hepcidin expression and increases serum iron levels in vivo.23 These observations were complemented by the finding that the hepcidin promoter contains both BMP-responsive SMAD-binding and IL-6–responsive STAT3-binding elements, which act cooperatively to regulate hepcidin gene expression.24,25

Based on these concepts, we hypothesized that BMP signaling has a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of AI and sought to further define the relationship between BMP signaling and IL-6 in the regulation of hepcidin expression. We used cultured hepatoma cells, transgenic zebrafish, and mouse models, as well as a small molecule inhibitor of BMP type I receptors (LDN-193189),26 to elucidate the role of BMP signaling. We also examined the direct effect of BMP signaling on numbers and function of bone marrow (BM)–derived hematopoietic stem cells. Our studies in these complementary models support the concept that targeting BMP signaling might be effective for the treatment of AI.

Methods

Materials

Human recombinant IL-6 was obtained from R&D Systems. LDN-193189 (4-(6-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)quinoline) was synthesized as a hydrochloride salt, as previously described26 (with > 98% purity as demonstrated by HPLC and 1H-NMR); dissolved in sterile, endotoxin-free water at 1.5 mg/mL; and neutralized to pH 6.8. Oil of turpentine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Human recombinant ALK3 extracellular domain expressed as an Fc fusion protein (ALK3-Fc) was obtained for in vitro experiments from R&D Systems and for in vivo experiments from Acceleron Inc. Human recombinant noggin protein was purchased from PeproTech.

Cells and media

Human hepatoma cells (HepG2; ATCC) were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine. Cells were transferred to 12-well dishes and starved with EMEM containing 0.1% FBS for at least 6 hours before IL-6 stimulation.

Quantitation of mRNA levels

RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized using MMLV-RT (Invitrogen). RNA was extracted from mouse livers using RNeasy (QIAGEN). Real-time amplification of transcripts was detected using a Mastercycler ep Realplex (Eppendorf). The relative expression of target transcripts was normalized to levels of 18S rRNA for mouse and human RNA and to levels of ribosomal protein rpl13a RNA for zebrafish. The sequences of primers used in these experiments are listed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Measurement of phosphorylated and total SMAD proteins

Cells or tissue were harvested in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Extracts were fractionated using 10% Tris-SDS polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with primary antibodies for total SMAD1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and phosphorylated forms of SMAD1/5/8 (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by HRP-linked anti–rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology). Bound antibodies were detected using ECL-Plus (GE Healthcare) and chemifluorescence with a Versadoc 4000MP imager (Bio-Rad).

IL-6 over-expression in zebrafish

Zebrafish over-expressing human IL-6 (hIL-6) were generated using the GAL4-UAS system.27 Briefly, the coding sequence of a hIL-6 cDNA was subcloned into a modified UAS-expression vector (pBH-UAS-Gtwy). A transgenic zebrafish line (pBH-UAS-IL6) was established by microinjecting this construct into fertilized oocytes and out-crossing the founders to wild-type (WT) fish. To achieve cardiac-specific hIL-6 expression, the pBH-UAS-IL6 fish were mated with fish expressing the GAL4 protein under the control of cardiac myosin light chain 2 (cmlc2) promoter (pCH-cmlc2-G4VP16) to produce double transgenic fish (cmlc-Gal4::UAS-IL6 or “cmlc-IL-6”). Expression of the hIL-6 transgene in cmlc-IL-6 zebrafish hearts was confirmed by in situ hybridization and immunoblot analysis using a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against hIL-6 (MAB2061; R&D Systems). All experiments using zebrafish were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care.

Murine models of AI

All experiments were performed using 10-week-old C57BL/6 female mice (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) maintained on a standard iron-replete diet (Prolab Isopro 3000 5P75; Labdiet).

In short-term studies examining the role of IL-6 in the regulation of hepcidin and iron, mice were challenged with a single intravenous injection of recombinant IL-6 (16 μg) or vehicle. To examine the role of turpentine-induced inflammation, mice received a single subcutaneous intrascapular injection of turpentine (5 mL/kg)28 under anesthesia with ketamine (0.1 mg/g body weight intraperitoneally [IP]) and xylazine (0.01 mg/g body weight IP). To test the overlay of BMP signaling on hepcidin expression and hypoferremia, LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP) or vehicle was administered 1 hour before challenge with turpentine, IL-6, or vehicle, and every 12 hours thereafter for up to 96 hours. Alternatively, ALK3-Fc (2 mg/kg IP) or vehicle was administered 1 hour before challenge with turpentine and every 24 hours thereafter.

In longer-term studies testing the contribution of BMP signaling to anemia induced by turpentine, LDN-193189 was administered every 24 hours during 3 weeks of concurrent turpentine administration. At the completion of the protocol, blood was drawn by cardiac puncture after administration of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg IP) for the measurement of serum iron levels (Fe/UIBC kit; Thermo Scientific), IL-6 (Mouse IL-6 ELISA Kit; R&D Systems) and peripheral blood counts. Liver tissues were obtained to measure levels of hepcidin mRNA as well as SMAD1 and phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 protein. All experiments using mice were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care.

Flow cytometric analysis of hematopoietic and erythroid progenitor cell lineages

To immunophenotypically enumerate hematopoietic stem cells and various lineages of erythroid progenitor cells, single-cell suspensions of BM-derived mononuclear cells were obtained by lysis of BM with ACK Lysing Buffer (Lonza). Cells were stained with biotinylated lineage antibodies (anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti–Ter-119, anti–Gr-1, anti–Mac-1, and anti-B220; BD Biosciences), and anti CD19 (ebioscience) and then labeled with streptavidin linked to Pe-Cy7 (BioLegend). Staining was performed with anti–c-Kit linked to APC-eFluor 780 (ebioscience), anti–Sca-1 linked to Pacific blue, anti-CD48 linked to FITC and anti-CD150 linked to phycoerythrin (BioLegend). Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were defined by the surface phenotype Lin− CD48− c-Kit+ Sca+ CD150+ within the population of mononuclear BM cells defined by forward (FSC) versus side scatter (SSC), as previously described.29 Megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) were defined by the surface phenotype Lin− c-Kit+ Sca− CD34− CD16/32−. Common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) were defined by the surface phenotype Lin− c-Kit+ Sca− CD34+ CD16/32−, and unrelated granulocyte monocyte progenitors (GMPs) were defined by the surface phenotype Lin− c-Kit+ Sca− CD34+ CD16/32+, as previously described.30 Flow cytometry was performed on the LSR-II tabletop flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

HSC competitive transplantation

For in vivo quantification of hematopoietic stem cells after LDN-193189 administration, 5 × 105 BM mononuclear cells from CD45.1+ B6.SJL mice (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) were mixed with 5 × 105 cells from vehicle- or LDN-193189-injected CD45.2+ C57BL/6 mice. Cells were injected in recipient CD45.2+ C57BL/6 mice, which were lethally irradiated 24 hours previously with 9.5 Gy of radiation from a 131Cesium source. The relative contribution of engraftment from the different cell sources was assessed in peripheral blood obtained from the tail vein by flow cytometry of BM mononuclear cells using anti-CD45.1 antibody linked to PE-Cy5.5 and anti-CD45.2 antibody linked to APC-Cy7 (BioLegend). Mice were killed at 16 weeks, and the BM mononuclear fraction was stained with anti-CD45.1 and anti-CD45.2 to assess the relative contribution to the BM of the competing input populations.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean (± SEM) unless otherwise noted. Data were analyzed using the Student t test, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test for multiple comparisons, or 2-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons including Bonferroni posthoc test. Statistical significance was considered for P values ≤ 0.05.

Results

BMP signaling is pivotal for the induction of hepcidin expression by IL-6 in hepatoma cells

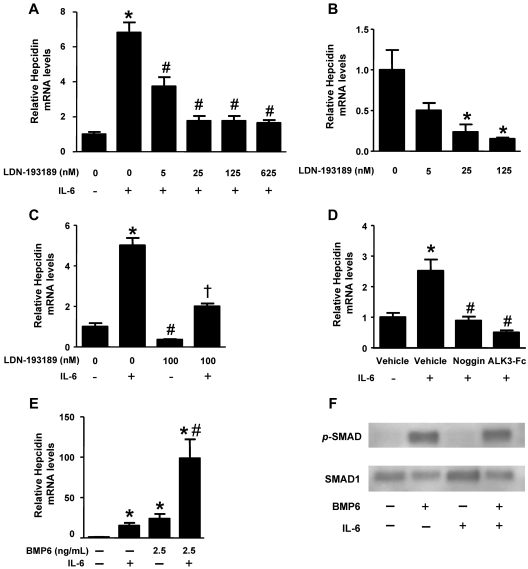

We examined the relationship between BMP signaling and IL-6–mediated hepcidin expression in HepG2 hepatoma cells. We found that IL-6 increased hepcidin mRNA levels within 60 minutes with peak levels achieved after 90 minutes (supplemental Figure 1A). Pretreatment of HepG2 cells with LDN-193189 reduced the IL-6–mediated induction of hepcidin gene expression in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 ∼ 5nM; Figure 1A). Incubation of HepG2 cells with LDN-193189 in the absence of IL-6 reduced basal hepcidin mRNA levels with similar potency (Figure 1B). Although LDN-193189 decreased basal and IL-6–mediated expression of hepcidin, some induction of hepcidin by IL-6 was observed in the presence of LDN-193189 (Figure 1C). To confirm that the effect of LDN-193189 on hepcidin expression was attributable to its effects on BMP signaling rather than an off-target effect, HepG2 cells were pretreated with recombinant BMP antagonists, noggin (1 μg/mL), or ALK3-Fc (1 μg/mL), which prevent receptor-mediated signaling by sequestering BMP ligands. Noggin and ALK3-Fc also reduced the ability of IL-6 to induce hepcidin gene expression (Figure 1D). These results demonstrate that BMP inhibitors can markedly attenuate the induction of hepcidin expression by IL-6.

Figure 1.

Impact of BMP signaling on IL-6–mediated regulation of hepcidin. HepG2 cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of LDN-193189 for 30 minutes and (A) stimulated with IL-6 (100 ng/mL) or (B) vehicle for 90 minutes. Hepcidin mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR (values are mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3, 1-way ANOVA P < .05, *P < .05 vs untreated control, #P < .05 vs IL-6–treated control). (C) HepG2 cells were pretreated with and without LDN-193189 (100nM) for 30 minutes and stimulated with or without IL-6 (100 ng/mL). Hepcidin mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR (1-way ANOVA P = .01, *P = .01 vs control, #P < .05 vs control, and †P < .02 vs IL-6–stimulated cells). (D) HepG2 cells were pretreated with noggin (1 μg/mL), ALK3-Fc (1 μg/mL), or vehicle for 30 minutes and incubated with IL-6 (100 ng/mL) or vehicle for 90 minutes, and hepcidin mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR (n = 3, 1-way ANOVA P < .0001, *P < .04 vs vehicle-treated controls, #P < .05 vs IL-6–treated controls). (E) HepG2 cells were treated with either vehicle, BMP6 (2.5 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL), or BMP6 and IL-6, and hepcidin mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR (n = 3, 1-way ANOVA P = .003, *P < .05 vs untreated control, #P < .05 vs IL-6–treated control). (F) Protein extracts were prepared from HepG2 cells treated either with vehicle, BMP6 (10 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL), or BMP6 and IL-6 for 30 minutes. Phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 and total SMAD1 were detected by immunoblot techniques.

The relationship between BMP and IL-6 signaling in hepcidin regulation

To investigate the potential synergy between BMP and IL-6 signaling pathways in the regulation of hepcidin gene expression, we tested the effect of IL-6 in HepG2 cells incubated in the presence of varying concentrations of BMP6. Treatment of HepG2 cells with BMP6 modestly increased hepcidin gene expression, whereas the combination of BMP6 and IL-6 markedly increased hepcidin mRNA levels to a degree that appeared greater than the additive effects of the 2 molecules (Figure 1E and supplemental Figure 1B-C).

The observation that the induction of hepcidin gene expression by IL-6 could be blunted by BMP inhibitors and that IL-6 and BMP6 could induce hepcidin gene expression synergistically raised the possibility that IL-6 might itself activate BMP signaling. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of IL-6 to induce SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation in HepG2 cells in the presence and absence of BMP6. Incubation of HepG2 cells with IL-6 did not induce phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8. Incubation with BMP6 (10 ng/mL) induced SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation, and this effect was not modulated by coincubation with IL-6 (Figure 1F). Taken together, these findings suggest that the observed synergy between IL-6 and BMP signaling in regulating hepcidin was not attributable to the direct activation of the canonical BMP signaling pathway (ie, SMAD-dependent) by IL-6.

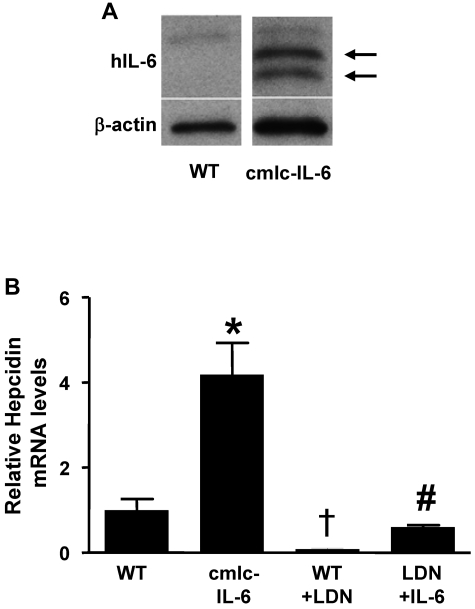

BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces the ability of IL-6 to induce hepcidin expression in zebrafish

Although a zebrafish orthologue for IL-6 has yet to be identified, the zebrafish genome contains an orthologue of the IL-6 receptor, suggesting that it might be feasible to test the ability of IL-6 to induce hepcidin gene expression in zebrafish. To express IL-6 in zebrafish, double-transgenic zebrafish were generated in which the GAL4-UAS system and a cardiac myosin light chain (cmlc2) promoter were used to direct the expression of human IL-6 (hIL-6) in the heart (“cmlc-IL-6” transgenic fish). Expression of hIL-6 in the double-transgenic fish was confirmed by immunoblot and in situ hybridization (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure 2A). Transgenic expression of hIL-6 resulted in a 4-fold increase in hepcidin mRNA levels in transgenic larvae (7 days postfertilization; Figure 2B). Markedly elevated hepcidin mRNA levels were also found in the livers of adult cmlc-IL-6 transgenic fish (supplemental Figure 2B). Incubation of WT larvae with LDN-193189 reduced basal hepcidin mRNA levels and attenuated the induction of hepcidin in IL-6 transgenic animals (Figure 2B). Moreover, LDN-193189 decreased baseline hepcidin mRNA levels in adult WT zebrafish (supplemental Figure 2C). Taken together, these results suggest that expression of IL-6 in zebrafish stimulates hepcidin gene expression that can be attenuated by an inhibitor of BMP signaling.

Figure 2.

LDN-193189 inhibits the induction of hepcidin by inflammation in zebrafish. (A) Human IL-6 protein was detected in homogenates of double transgenic (cmlc-IL-6) but not in those of WT zebrafish hearts (arrows). β-actin was used to control for protein loading. (B) Hepcidin mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR in the livers of 7-day-old WT and cmlc-IL-6 zebrafish treated with vehicle or LDN-193189 (6μM) for 16 hours. (n = 3, *,†P < .05 vs WT, #P < .05 vs cmlc-IL-6).

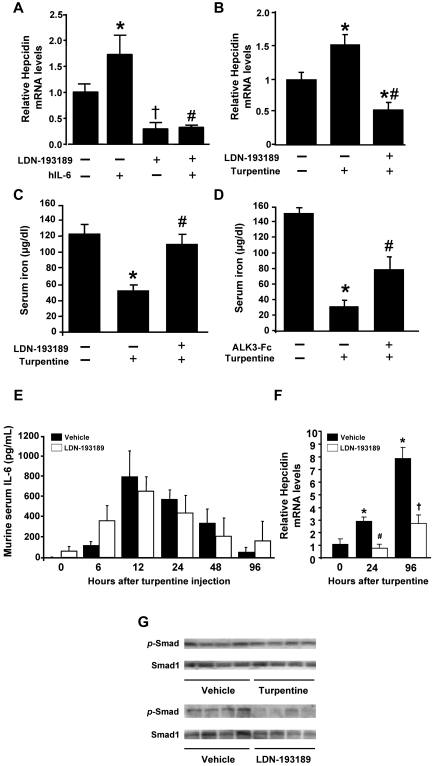

Impact of BMP inhibition on IL-6–induced hepcidin expression in mice

To evaluate the role of BMP signaling in regulating hepcidin gene expression because of inflammatory mediators in vivo, we studied IL-6–induced hepcidin expression in intact mice. Similar to previous reports, intravenous injection of IL-6 (16 μg) into adult C57BL/6 mice increased hepatic hepcidin mRNA levels within 2 hours (Figure 3A). Treatment of mice with LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP) reduced basal hepcidin mRNA levels. The ability of IL-6 to increase hepcidin gene expression was reduced by pretreatment with LDN-193189.

Figure 3.

LDN-193189 inhibits short-term IL-6– and turpentine-induced hypoferremia and hepcidin expression. (A) IL-6 (16 μg) or vehicle were injected IV into 10-week-old mice pretreated with or without LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP) or vehicle. After 2 hours, livers were harvested, and hepcidin mRNA levels were measured using qRT-PCR (n ≥ 3 each group, 1-way ANOVA P < .005, *P < .05 vs control, †P < .05 vs saline, #P < .05 vs IL-6–stimulated mice). (B-C) Mice were pretreated with LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP repeated each 12 hours) or drug vehicle, followed by a single intrascapular injection with turpentine (5 mL/kg) or saline. Twenty-four hours after the turpentine injection, hepcidin mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR (B), and serum iron levels were assayed (C; n ≥ 4, *P ≤ .01 vs untreated controls, #P < .05 vs turpentine). (D) Mice were pretreated with ALK3-Fc (2 mg/kg IP) or vehicle, followed by intrascapular injection with turpentine or saline, and serum iron levels measured (n ≥ 5, *P < .000 01 vs untreated control, #P < .05 vs turpentine). Serum IL-6 levels (E) were determined by ELISA before and 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 hours after turpentine injection with or without LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg) administered every 12 hours (n = 5 mice per time point and treatment). Hepcidin gene expression in the livers of treated mice was measured by qRT-PCR at 0, 24 and 96 hours (F; n = 5, 1-way ANOVA P = .003, *P < .05 vs 0 hours, #P < .01 vs vehicle at 24 hours, †P = .01 vs vehicle at 96 hours). Levels of phosphorylated-SMAD1/5/8 (p-SMAD) and SMAD1 proteins (G) in the livers of mice treated with vehicle, turpentine, or LDN-193189 were measured by immunoblot (n = 4 mice each).

Impact of BMP inhibition on turpentine-induced hepcidin expression and hypoferremia in mice

We used turpentine administration in mice to study the contribution of BMP signaling to short- and long-term effects of inflammation on hepcidin and iron metabolism. A single subcutaneous injection of turpentine (5 mL/kg) increased levels of hepcidin mRNA between 50% and 200% within 24 hours and by nearly 700% at 96 hours (Figure 3B and F). The turpentine-induced increases in hepcidin mRNA levels at 24 hours and 96 hours could be inhibited by cotreatment with LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP every 12 hours; Figure 3B and F). Consistent with the elevated hepcidin gene expression, serum iron levels decreased to less than 40% of basal levels 24 hours after a single turpentine injection. Treatment with LDN-193189 prevented turpentine-induced hypoferremia (Figure 3C). Similar increases in serum iron levels were observed when mice were treated with LDN-193189 for 6 days after turpentine administration (supplemental Figure 3). To confirm that the effects of LDN-193189 on serum iron levels in turpentine-treated mice were because of the inhibition of BMP signaling, we tested the impact of ALK3-Fc on the hypoferremia induced by turpentine. Pretreatment with ALK3-Fc attenuated the turpentine-induced hypoferremia at 24 hours (Figure 3D). Consistent with the notion that turpentine induces hepcidinemia and anemia in an IL-6–dependent fashion, we found that turpentine injection markedly increased IL-6 levels (Figure 3E). LDN-193189 did not modulate the turpentine-induced increases in IL-6 levels. Similar to our findings in HepG2 cells and zebrafish that IL-6 does not directly activate BMP signaling, turpentine injection did not induce phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 in hepatic tissues (Figure 3G top panel). However, LDN-193189 markedly reduced levels of phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 in livers of mice that did not receive turpentine (Figure 3G bottom panel).

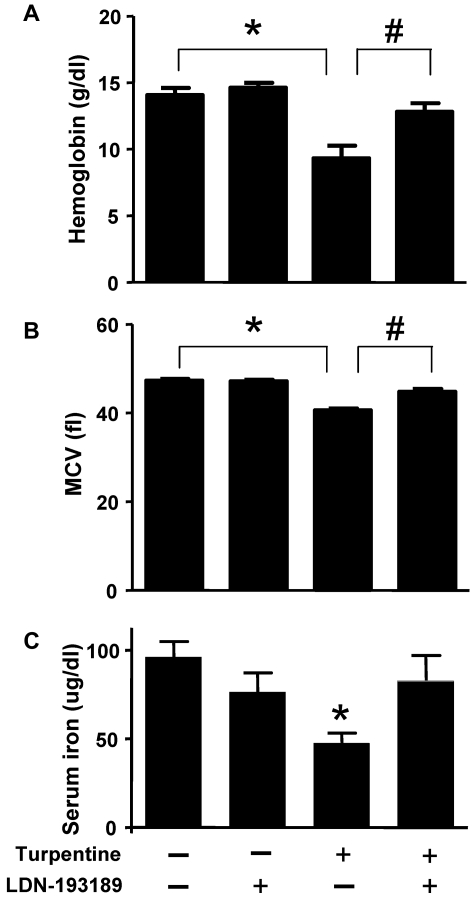

BMP inhibition attenuates turpentine-induced anemia in mice

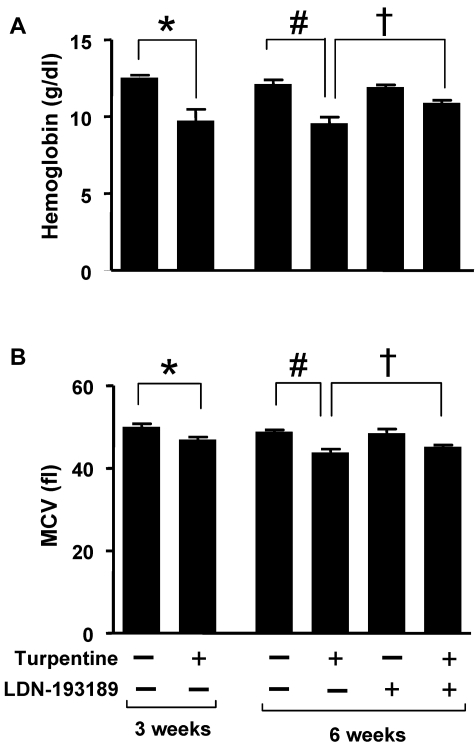

To model AI, mice were injected once a week with turpentine for 3 weeks. Turpentine-challenged mice developed anemia and microcytosis consistent with severe AI (Figure 4A and B). Treatment with LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP every 24 hours, starting concurrently with the initiation of turpentine injections) increased hemoglobin to levels seen in mice that did not receive turpentine. Similarly, LDN-193189 normalized MCV in turpentine-treated mice. Treatment of saline-challenged mice with LDN-193189 did not affect Hb or MCV levels. LDN-193189 did not influence the turpentine-mediated induction of neutrophilia (18% ± 4% neutrophils in vehicle-injected animals, and 61% ± 28% in turpentine-challenged mice versus 65% ± 16% in turpentine-challenged mice that were treated with LDN-193189). Turpentine injections decreased serum iron levels, which were nearly normalized by treatment with LDN-193189 (Figure 4 C).

Figure 4.

LDN-193189 prevents the development of turpentine-induced anemia. C57BL/6 mice were injected once a week with turpentine (5 mL/kg intrascapularly) or saline for 3 weeks, while receiving daily injections of LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP) or vehicle. Blood Hb levels (A) were reduced by repeated turpentine injection, not affected by LDN-193189 treatment alone, and were increased to levels of untreated mice in turpentine-injected mice treated with LDN-193189 (n = 7 mice each, *,#P < .0001 turpentine-injected vs saline-injected controls, and turpentine-injected vs turpentine-injected treated with LDN-193189). (B) Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was decreased as a result of repeated turpentine injection, and normalized when LDN-193189 was administered in combination with turpentine (*P < .0001 turpentine-injected vs saline-injected controls, #P = .01 turpentine-injected vs turpentine-injected treated with LDN-193189). Serum iron levels (C) were similarly decreased as a result of turpentine-injection, and partially normalized by the concurrent administration of LDN-193189 (*P < .05 turpentine-injected vs saline-injected animals). Data shown are representative of 5 independent experiments.

BMP inhibition ameliorates established turpentine-induced anemia

To determine whether inhibition of BMP signaling can mitigate established AI, mice were challenged with turpentine weekly for 6 weeks. Beginning after 3 weeks, when microcytic anemia was established, mice were treated with LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP every 24 hours) or vehicle. After 6 weeks of turpentine administration, Hb levels were 1.3 g/dL greater in mice treated with LDN-193189 for 3 weeks than in animals that received vehicle (P < .05, Figure 5). Treatment with LDN-193189 also tended to increase mean corpuscular volume (MCV, P = .10). These results suggest that inhibition of BMP signaling can partially reverse established anemia associated with chronic inflammation.

Figure 5.

LDN-193189 increases Hb levels in established turpentine-induced anemia. (A-B) Mice were injected with turpentine (5 mL/kg intrascapularly) or saline weekly for 3 weeks resulting in microcytic anemia in turpentine-injected mice (left panels; n = 5 per group, *P < .05 turpentine-injected vs saline-injected controls). After 3 weeks, turpentine-treated mice were treated daily with LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP) or vehicle, while intrascapular turpentine or saline injections continued for an additional 3 weeks. At 6 weeks, Hb levels (A) in turpentine-injected mice were less than those in saline-injected mice, while administration of LDN-193189 by itself had no significant effect, and administration of LDN-193189 in turpentine-injected mice increased Hb levels to a significant degree (right panel; n = 5 per group, 1-way ANOVA P = .005, #P < .05 turpentine-injected vs saline-injected controls, †P < .05 turpentine-injected vs turpentine-injected mice treated with LDN-193189). MCV (B) was persistently decreased as a result of turpentine injections after 6 weeks, and tended to improve with LDN-193189 treatment (right panel; n = 5 per group, 1-way ANOVA P = .0002, #P < .01 turpentine-injected vs saline-injected controls, †P = .1 turpentine-injected vs turpentine-injected treated with LDN-193189). Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Influence of BMP inhibition on cellular blood count and numbers of early and late BM progenitor cells

Because BMP signals are known to influence the differentiation and growth of diverse progenitor cell populations, we tested the possibility that BMP inhibition might attenuate anemia of inflammation by directly modulating hematopoietic cell progenitors. Treatment of mice with LDN-193189 for 28 days did not alter circulating numbers of mature red blood cells, granulocytes, lymphocytes, or platelets (supplemental Table 2). To elucidate the possible effects of LDN-193189 on HSCs, we measured the frequency of a mononuclear BM cell population known to be highly enriched for functional HSCs with reconstitution potential in mice that had been injected daily with vehicle or LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg IP for 14 or 28 days; supplemental Figure 4A-B). Treatment with LDN-193189, in a manner sufficient to suppress hepcidin expression at 14 (data not shown) and 28 days (supplemental Figure 5), did not affect the frequency of BM-derived HSCs.

To evaluate the impact of BMP signaling inhibition on erythropoiesis, we analyzed the maturation of several erythroid progenitor cell populations in the BM, including the MEPs and the CMPs from which they are derived, as well as GMPs. After 14 or 28 days of treatment, we found no impact of BMP inhibition on the numbers of MEPs, CMPs, or GMPs (supplemental Figure 6 A-C). In addition, LDN-193189 did not alter the number of mature T cells, mature B cells and granulocytes in the BM (supplemental Figure 6 D-F).

To determine whether the function of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells might be impacted by treatment with LDN-193189, CD45.1+ BM cells were mixed with BM harvested from CD45.2+ mice treated with vehicle or LDN-193189 in a 1:1 ratio. One million cells were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.2+ recipient mice. In this competitive transplant experiment, no difference in numbers of CD45.2+ cells was noted between the cohorts engrafted with vehicle- or LDN-193189–treated CD45.2+ BM at 12 (supplemental Figure 7) and 16 (data not shown) weeks after BM transplantation. In conclusion, we found that LDN-193189 did not exert direct effects on the numbers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations and did not alter the engraftment potential of BM-derived hematopoietic progenitors.

Discussion

In the present study, we report that BMP signaling contributes to the induction of hepatic hepcidin expression by inflammatory signals in vitro and in vivo. Studies in cultured hepatoma cells and experiments in zebrafish and mice demonstrated that IL-6 does not directly activate BMP signaling (SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation), but rather IL-6 activates hepcidin gene expression in a manner that is synergistic with BMP signaling. As previously described, we found that IL-6 and turpentine potently induce hepcidin expression in mice and that chronic turpentine administration leads to anemia.28,31 We demonstrated that the hypoferremia and hepcidin expression induced by turpentine administration, known to require IL-6,28,32 can be attenuated by the administration of small molecule BMP inhibitor LDN-193189 or the recombinant BMP ligand antagonist ALK3-Fc. We found that that pharmacologic BMP inhibition prevented the development of microcytic anemia in a model of AI when administered prophylactically and could increase hemoglobin levels even after anemia was established. The effects of inhibiting BMP signaling on turpentine-induced anemia did not appear to depend on modifying the inflammatory response to turpentine, as treatment with LDN-193189 did not prevent the increase in circulating IL-6 levels or neutrophilia induced by turpentine. Moreover, inhibiting BMP signaling did not have direct effects on the abundance or function of hematopoietic or erythroid progenitor populations.

We and others have used hepatocyte-derived cell lines to model the hepatic regulation of hepcidin expression in response to BMP ligand or IL-6 stimulation in vitro.20,23,33,34 In the current studies, we tested BMP6, known to be a critical BMP signaling ligand for the regulation of hepcidin in vivo.18,35 Our observations in hepatocyte-derived lines confirm the previously described connection between BMP signaling- and IL-6–mediated regulation of hepcidin gene expression.24,28,36–38 Neither IL-6 nor turpentine directly activated the BMP signaling pathway, as assessed by measuring phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8. Rather, the synergy between BMP signaling and IL-6 in regulating hepcidin is likely mediated by the previously described interaction of their respective promoter elements upstream of the hepcidin gene.24,36,39,40 Our studies in zebrafish and mice corroborate the mechanistic link in vivo between inflammation- and BMP-mediated regulation of hepcidin gene expression.

Using the small molecule BMP inhibitor, dorsomorphin, we previously reported that hepatic BMP signaling is critical for basal regulation of hepcidin expression in zebrafish and mice and contributes to the induction of hepcidin expression in response to increased serum iron levels.23 In the current study, we used LDN-193189, a dorsomorphin derivative with greater potency and specificity than the parent compound,23,26 to inhibit hepcidin gene expression. LDN-193189 inhibited hepcidin expression in HepG2 cells in a dose-dependent manner with a similar potency to its inhibition of BMP4-induced activation of SMAD1/5/8 (IC50 ∼ 5nM).41 To confirm that LDN-193189 exerted its effects by inhibiting BMP signaling, rather than another target, we used 2 recombinant protein inhibitors of BMP signaling, noggin and ALK3-Fc. We found that IL-6–mediated induction of hepcidin gene expression in HepG2 cells could be reduced by recombinant noggin or ALK3-Fc as potently as by LDN-193189. Similarly, treatment with ALK3-Fc was effective in preventing hypoferremia induced by turpentine administration in mice. Taken together, these studies further support the concept that BMP signaling is a critical regulator of hepcidin expression and that inhibition of BMP signaling attenuates IL-6- and turpentine-induced hepcidin gene expression and hypoferremia and, by extension, the anemia that results from chronic inflammation. It is important to note that both BMP and IL-6 signals can signal via pathways other than SMADs and STAT3, respectively, including MAP kinase cascades, particularly ERK1/2 for IL-6 and p38 for BMP signaling.42–44 It is possible that IL-6 may interact with BMP signaling to regulate hepcidin expression via pathways that were not directly tested in our studies.

The turpentine-induced model of chronic inflammation has been used widely to assess the impact of inflammation on iron handling and erythropoiesis in mammals.13,32 This model recapitulates several features of the AI that have been observed in human subjects including hepcidinemia,13,32,45 hypoferremia, hyperferritinemia, suppression of erythropoiesis, and decreased erythrocyte survival. It has been demonstrated that IL-6 is required for the induction of hepcidin expression and hypoferremia in turpentine-challenged mice.32 Moreover, inducible over-expression of hepcidin induces anemia and microcytosis in mice.46 We report that treatment of turpentine-challenged mice with LDN-193189 decreases hepcidin gene expression, increases iron availability for erythropoiesis, and increases hemoglobin. While LDN-193189 may not modulate every pathway that contributes to anemia in turpentine-challenged mice, we found that LDN-193189 treatment increases hemoglobin concentration when administered concurrently or after anemia was established. It is acknowledged that the relatively brief period of observation of 3 to 6 weeks might tend to underestimate the full degree of anemia caused by inflammation. However, in this model, we did not observe progression in the degree of anemia with continued turpentine treatment (at 3 versus 6 weeks). These observations are consistent with recent findings that treatment with anti–IL-6 antibodies can reduce hepcidin levels and increase hemoglobin levels in patients with Castleman disease.47 Moreover, in a Brucella abortus–induced model of AI, it was shown that administration of a hepcidin-neutralizing antibody can increase hematocrit.2 These reports, along with our current data, provide compelling evidence in several distinct contexts that inhibiting hepcidin or its upstream regulatory signals may be useful for the treatment of AI. Importantly, our study is the first to report the application of a small molecule inhibitor of the BMP/IL-6/hepcidin axis to ameliorate anemia in an animal model of AI. It is acknowledged, however, that mediators other than IL-6 may regulate hepcidin expression in some inflammatory states associated with AI,17 and it is possible that some of these mediators may not require BMP signaling to induce hypoferremia and anemia. If observations in mice may be extrapolated to patients, we suggest LDN-193189 and other BMP inhibitors may increase hemoglobin concentrations in individuals with elevated hepcidin levels in the context of chronic inflammation associated with increased IL-6 levels.

While hepcidin has many properties of a classic acute phase reactant,17 recent reports have suggested that the relationship between hepcidin, inflammation, and BMP signaling may be more complex than previously thought. De Domenico and colleagues reported that hepcidin can inhibit lipopolysaccharide-, poly(I:C)-, and turpentine-induced inflammation and can prevent lipopolysaccharide-induced shock.48 In contrast, Wang et al found in 2 murine colitis models (infectious and noninfectious), that inflammation could be inhibited by blocking BMP-induced hepcidin expression using several different BMP inhibitors (dorsomorphin, LDN-193189, and HJV-Fc).49 In our AI model, BMP inhibition did not appear to modulate the inflammatory response to turpentine based on the induction of IL-6 or neutrophilia.

Previous reports have suggested that the fate and proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells is specified in part by the presence or absence of BMP4-mediated signaling.50 Thus, we considered the possibility that LDN-193189 acts to increase erythrocyte counts or induce polycythemia via direct effects on the turnover or proliferation of early hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Phenotypic analysis of BM cells demonstrated that prolonged administration of LDN-193189 to mice did not elicit changes in early hematopoietic or erythroid progenitor lineages. The hematopoietic stem cells present in the BM of mice treated with LDN-193189 retained functionality, as measured by their reconstitution potential in competitive BM transplants, and showed no evidence of enhanced function. Our data appear to be consistent with a recent report that abrogation of canonical BMP signaling via the bone-marrow specific ablation of Smad1 and Smad5 does not impact the normal function and engraftment potential of HSCs.48 While our findings demonstrate that LDN-193189 does not directly impact hematopoietic progenitor populations in normal mice, it is conceivable that LDN-193189 might affect the proliferation or induction of immature hematopoietic lineages in mice chronically challenged with turpentine.

The current studies demonstrate that inhibition of BMP signaling attenuates the induction of hepcidin gene expression in the context of IL-6–mediated inflammation in vitro and in 2 animal models. To the extent that AI of diverse etiologies in man requires hepcidin and IL-6 signaling, our results suggest that the inhibition of BMP signaling may be an effective strategy for treating AI. The approach of inhibiting BMP signaling joins a growing list of pharmacologic strategies that target hepcidin synthesis or function to treat AI. Additional work will be needed to determine whether these strategies, including BMP signaling inhibition, can be extended to AI associated with diverse etiologies of chronic inflammation or disease and whether the hematologic benefits lead to improved clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Nonet for providing the modified UAS-expression vector, pBH UAS Gtwy (http://www.dbbs.wustl.edu/RIB/NonetMicL); and Peter Schlueter for sharing the pCH-cmlc2-G4VP16 transgenic fish.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG SW 119/3-1 (A.U.S.), NHLBI 1R01HL097794 (D.T.S.), Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research and NIDDK 1R01DK082971 (R.T.P. and K.D.B.), and NHLBI 5K08HL079943, Harvard Stem Cell Institute Seed Grant and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Physician-Scientist Award (P.B.Y.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: In vitro experiments were designed and performed by A.U.S., A.J.V., K.M.R., K.D.B., and P.B.Y.; zebrafish experiments were designed and performed by C.S. and R.T.P.; experiments involving mouse anemia models were designed and performed by A.J.V., A.U.S., D.Y.D., C.S.L., C.N.R., K.D.B., and P.B.Y.; studies analyzing hematopoietic progenitors and BM transplantation were designed and performed by R.Z.Y., J.C.W., B.S., C.M.C., B.A.S., D.T.S., K.D.B., and P.B.Y.; data were analyzed by A.U.S., A.J.V., C.S., R.Z.Y., K.D.B., and P.B.Y.; J.S.S. and G.D.C. provided critical experimental reagents and experimental advice; and the manuscript was written by A.U.S., C.S., R.Z.Y., K.D.B., and P.B.Y.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital have applied for patents related to dorsomorphin and its derivatives, and G.D.C., R.T.P., K.D.B., and P.B.Y. may be entitled to royalties. J.S.S. owns stock in Acceleron Pharma Inc, and may benefit financially from patents related to ALK3-Fc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation of A.U.S. is Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Muenster University, Muenster, Germany. The current affiliation of C.S. is Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (IGIB), Delhi, India.

Correspondence: Dr Paul B. Yu, Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Thier 505, 50 Blossom St, 02114 Boston, MA; e-mail: pbyu@partners.org.

References

- 1.Nicolas G, Bennoun M, Porteu A, et al. Severe iron deficiency anemia in transgenic mice expressing liver hepcidin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(7):4596–4601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072632499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasu BJ, Cooke KS, Arvedson TL, et al. Antihepcidin antibody treatment modulates iron metabolism and is effective in a mouse model of inflammation-induced anemia. Blood. 2010;115(17):3616–3624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):1011–1023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutel G, Ganser A. Risks and benefits of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in cancer management. Semin Hematol. 2007;44(3):157–165. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Ahmad A, Rand WM, Manjunath G, et al. Reduced kidney function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(4):955–962. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckardt KU. Anaemia in end-stage renal disease: pathophysiological considerations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(suppl 7):2–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.suppl_7.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann JF. What are the short-term and long-term consequences of anaemia in CRF patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(suppl 2):29–36. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.suppl_2.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Go AS, Yang J, Ackerson LM, et al. Hemoglobin level, chronic kidney disease, and the risks of death and hospitalization in adults with chronic heart failure: the Anemia in Chronic Heart Failure: Outcomes and Resource Utilization (ANCHOR) Study. Circulation. 2006;113(23):2713–2723. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang WH, Tong W, Jain A, Francis GS, Harris CM, Young JB. Evaluation and long-term prognosis of new-onset, transient, and persistent anemia in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(5):569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strippoli GF, Tognoni G, Navaneethan SD, Nicolucci A, Craig JC. Haemoglobin targets: we were wrong, time to move on. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):346–350. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sytkowski AJ. Does erythropoietin have a dark side? Epo signaling and cancer cells. Sci STKE. 2007;2007(395):38. doi: 10.1126/stke.3952007pe38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraenkel PG, Traver D, Donovan A, Zahrieh D, Zon LI. Ferroportin1 is required for normal iron cycling in zebrafish. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1532–1541. doi: 10.1172/JCI23780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolas G, Chauvet C, Viatte L, et al. The gene encoding the iron regulatory peptide hepcidin is regulated by anemia, hypoxia, and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(7):1037–1044. doi: 10.1172/JCI15686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolas G, Viatte L, Lou DQ, et al. Constitutive hepcidin expression prevents iron overload in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pigeon C, Ilyin G, Courselaud B, et al. A new mouse liver-specific gene, encoding a protein homologous to human antimicrobial peptide hepcidin, is overexpressed during iron overload. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(11):7811–7819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306(5704):2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemeth E, Valore EV, Territo M, Schiller G, Lichtenstein A, Ganz T. Hepcidin, a putative mediator of anemia of inflammation, is a type II acute-phase protein. Blood. 2003;101(7):2461–2463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andriopoulos B, Jr, Corradini E, Xia Y, et al. BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nat Genet. 2009;41(4):482–487. doi: 10.1038/ng.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):531–539. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Andrews NC, Lin HY. Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in vivo regulates systemic iron balance. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(7):1933–1939. doi: 10.1172/JCI31342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L, Valore EV, Nemeth E, Goodnough JB, Gabayan V, Ganz T. Iron transferrin regulates hepcidin synthesis in primary hepatocyte culture through hemojuvelin and BMP2/4. Blood. 2007;110(6):2182–2189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang RH, Li C, Xu X, et al. A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2005;2(6):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu PB, Hong CC, Sachidanandan C, et al. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4(1):33–41. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verga Falzacappa MV, Casanovas G, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. A bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)–responsive element in the hepcidin promoter controls HFE2-mediated hepatic hepcidin expression and its response to IL-6 in cultured cells. J Mol Med. 2008;86(5):531–540. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verga Falzacappa MV, Vujic Spasic M, Kessler R, Stolte J, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood. 2007;109(1):353–358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuny GD, Yu PB, Laha JK, et al. Structure-activity relationship study of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(15):4388–4392. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpern ME, Rhee J, Goll MG, Akitake CM, Parsons M, Leach SD. Gal4/UAS transgenic tools and their application to zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2008;5(2):97–110. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakamori R, Takehara T, Tatsumi T, et al. STAT3 signaling within hepatocytes is required for anemia of inflammation in vivo. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(2):244–248. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo Celso C, Fleming HE, Wu JW, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457(7225):92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404(6774):193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee P, Peng H, Gelbart T, Beutler E. The IL-6- and lipopolysaccharide-induced transcription of hepcidin in HFE-, transferrin receptor 2-, and beta 2-microglobulin-deficient hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(25):9263–9265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403108101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheikh N, Dudas J, Ramadori G. Changes of gene expression of iron regulatory proteins during turpentine oil-induced acute-phase response in the rat. Lab Invest. 2007;87(7):713–725. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma S, Nemeth E, Chen YH, et al. Involvement of hepcidin in the anemia of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(11):3262–3267. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, Beutler E. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4, and 9 stimulate murine hepcidin 1 expression independently of Hfe, transferrin receptor 2 (Tfr2), and IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(27):10289–10293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603124103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camaschella C, Silvestri L. New and old players in the hepcidin pathway. Haematologica. 2008;93(10):1441–1444. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maes K, Nemeth E, Roodman GD, et al. In anemia of multiple myeloma, hepcidin is induced by increased bone morphogenetic protein 2. Blood. 2010;116(18):3635–3644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truksa J, Lee P, Beutler E. The role of STAT, AP-1, E-box and TIEG motifs in the regulation of hepcidin by IL-6 and BMP-9: lessons from human HAMP and murine Hamp1 and Hamp2 gene promoters. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007;39(3):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truksa J, Lee P, Beutler E. Two BMP responsive elements, STAT, and bZIP/HNF4/COUP motifs of the hepcidin promoter are critical for BMP, SMAD1, and HJV responsiveness. Blood. 2009;113(3):688–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muckenthaler MU. Fine tuning of hepcidin expression by positive and negative regulators. Cell Metab. 2008;8(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood. 2006;108(9):3204–3209. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu PB, Deng DY, Lai CS, et al. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic [corrected] ossification. Nat Med. 2008;14(12):1363–1369. doi: 10.1038/nm.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knaus P, Sebald W. Cooperativity of binding epitopes and receptor chains in the BMP/TGFbeta superfamily. Biol Chem. 2001;382(8):1189–1195. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyazono K. Signal transduction by bone morphogenetic protein receptors: functional roles of Smad proteins. Bone. 1999;25(1):91–93. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puthier D, Bataille R, Amiot M. IL-6 up-regulates mcl-1 in human myeloma cells through JAK / STAT rather than ras / MAP kinase pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(12):3945–3950. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<3945::AID-IMMU3945>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(9):1271–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy CN, Mak HH, Akpan I, Losyev G, Zurakowski D, Andrews NC. Hepcidin antimicrobial peptide transgenic mice exhibit features of the anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2007;109(9):4038–4044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song SN, Tomosugi N, Kawabata H, Ishikawa T, Nishikawa T, Yoshizaki K. Downregulation of hepcidin resulting from long-term treatment with an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) improves anemia of inflammation in multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD). Blood. 2010;116(18):3627–3634. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-271791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Domenico I, Zhang TY, Koening CL, et al. Hepcidin mediates transcriptional changes that modulate acute cytokine-induced inflammatory responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2395–2405. doi: 10.1172/JCI42011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Harrington L, Trebicka E, et al. Selective modulation of TLR4-activated inflammatory responses by altered iron homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(11):3322–3328. doi: 10.1172/JCI39939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harandi OF, Hedge S, Wu DC, McKeone D, Paulson RF. Murine erythroid short-term radioprotection requires a BMP4-dependent, self-renewing population of stress erythroid progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4507–4519. doi: 10.1172/JCI41291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.