Abstract

During Xenopus oocyte maturation, the Mos protein kinase is synthesized and activates the MAP kinase cascade. In this report, we demonstrate that the synthesis and activation of Mos are two separable processes. We find that Hsp90 function is required for activation and phosphorylation of Mos and full activation of the MAP kinase cascade. Once Mos is activated, Hsp90 function is no longer required. We show that Mos interacts with both Hsp90 and Hsp70, and that there is an inverse relationship between association of Mos with these two chaperones. We propose that Mos protein kinase is activated by a novel mechanism involving sequential association with Hsp70 and Hsp90 as well as phosphorylation. We also present evidence for a two-phase activation of MAP kinase in Xenopus oocytes.

Keywords: Hsp90/MAP kinase/maturation/Mos/Xenopus oocyte

Introduction

The Mos proto-oncogene protein kinase activates the MAP kinase cascade in vertebrate oocytes by phosphorylation of the MAP kinase-activating kinase MEK. Mos function controls MAP kinase activation during a short window of development, the meiotic maturation of oocytes. MAP kinase activation is required for efficient Cdc2 activation during Xenopus oocyte maturation (for a review, see Sagata, 1997; Ferrell, 1999; Fisher et al., 1999a), which represses DNA replication between meiosis I and meiosis II (Furuno et al., 1994; Picard et al., 1996), and to maintain a stable metaphase arrest necessary for fertilization (Haccard et al., 1993; Colledge et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al., 1994). Mos is inactivated after exit from meiosis (Lorca et al., 1991; Watanabe et al., 1991; Roy et al., 1996) and this inactivation is required to allow entry into first mitosis (Abrieu et al., 1997; Walter et al., 1997; Bitangcol et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 1998) or, possibly, the first round of DNA replication in some species (Tachibana et al., 1997). The activation and inactivation of Mos thus control the cell cycle at a crucial period of development. To ensure the correct timing, Mos is regulated at several levels, including mRNA polyadenylation and translation (Gebauer et al., 1994; Sheets et al., 1995), and stabilization by phosphorylation from degradation by the ubiquitin pathway (Nishizawa et al., 1992). Polyadenylation of Mos mRNA is dependent on MAP kinase (Howard et al., 1999). The Mos–MEK–MAP kinase cascade is thus thought to constitute a positive feedback loop (Matten et al., 1996; Howard et al., 1999), although how the loop is triggered remains unclear. Mos also seems to be controlled at a further level, since its dephosphorylation, and the inactivation of MAP kinase at the end of meiosis, precedes its proteolysis (Roy et al., 1996). To what extent and by what mechanism Mos protein kinase activity is controlled is unknown.

The role of phosphorylation in the regulation of Mos is uncertain. Recombinant Mos can be phosphorylated, at least to some extent, by a pre-existing protein kinase in unstimulated Xenopus oocytes (Freeman et al., 1992), and Mos translated during meiotic maturation undergoes phosphorylation (Watanabe et al., 1989; Nishizawa et al., 1992) on several residues. One of these is Ser3, and phosphorylation of this site (Nishizawa et al., 1992) as well as Ser16 (Pham et al., 1999) stabilizes the protein. Ser3 may well be a target for autophosphorylation (Nishizawa et al., 1992), although kinase-dead Mos is also phosphorylated on Ser3 (Freeman et al., 1992) and MAP kinase can phosphorylate Mos on Ser3 in vitro (Matten et al., 1996). Nevertheless, Ser3 phosphorylation is apparently dispensable for the biological activity of Mos since expression of the non-phosphorylatable mutant S3A can still induce germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) (Freeman et al., 1992), although this mutant probably does not possess cytostatic factor (CSF) activity (Nishizawa et al., 1992). However, the S3A mutant exhibits reduced interaction with its substrate MEK and does not activate endogenous MAP kinases when expressed in reticulocyte lysates (Chen and Cooper, 1995), unlike wild-type Mos. Furthermore, in mammalian v–Mos, mutation of the equivalent residue Ser34 to alanine inhibits v–Mos activity (Yang et al., 1998). Mos has recently been shown to interact with the chaperone Hsp70, an interaction that probably requires Ser3 (Liu et al., 1999). The role of this interaction in Mos regulation is not clear.

We have recently demonstrated that interference with the function of Hsp90 prevents activation of MAP kinase in Xenopus oocyte maturation (Fisher et al., 1999a), but how prevention of MAP kinase activation is mediated was not analysed. Here we show that Mos interacts with Hsp90 in the oocyte and that this interaction is necessary for Mos activation, and thus for Mos-mediated MAP kinase activation. This defines for the first time an activation step in the regulation of Mos. We also demonstrate a biphasic activation of MAP kinase in progesterone-stimulated oocytes.

Results

Mos can be translated but is underphosphorylated and does not activate the MAP kinase cascade if Hsp90 is inhibited

We have recently reported that the specific Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin (GA) blocks sustained activation of MAP kinase in Xenopus oocytes (Fisher et al., 1999a), although we did not define the molecular target of Hsp90 inhibition.

Mos translation is part of a positive feedback loop in which MAP kinase stimulates, and is apparently required for, Mos synthesis (Matten et al., 1996; Howard et al., 1999). Since Mos is required for MAP kinase activation in Xenopus and mouse oocytes, we hypothesized that the target for Hsp90 inhibition may be Mos synthesis.

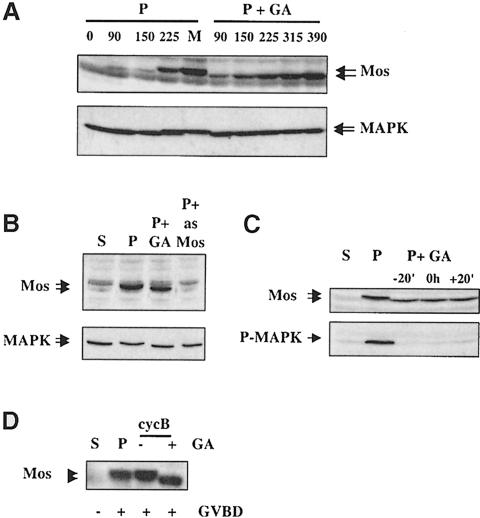

We therefore analysed the time course and dependence on Hsp90 function of Mos accumulation. Mos normally only accumulates to low levels before GVBD and undergoes a dramatic increase in accumulation at GVBD, along with a shift in mobility (Figure 1A, lanes 1–5). To allow initiation events potentially dependent on Hsp90, in this experiment GA was added after 20 min of progesterone treatment. In the absence of subsequent Hsp90 function, Mos can still attain approximately the same level, but MAP kinase does not undergo the stoichiometric electrophoretic mobility shift reflecting phosphorylation and activation (Figure 1A, lanes 6–10). We in fact found the same profile of Mos mobility/accumulation even if GA was added 2 h before progesterone (data not shown). That the antigen recognized is indeed Mos is demonstrated in Figure 1B: prior injection of antisense oligonucleotides to Mos prevented the progesterone-induced accumulation of this antigen and shift in mobility of MAP kinase, while inhibiting Hsp90 2 h before progesterone addition again did not prevent Mos accumulation although it did prevent the mobility shift of both Mos and MAP kinase. An independently isolated Mos antibody gave the same results (data not shown). To show that GA was not added too early, we examined what would happen if we added the inhibitor just before, at the same time as or just after progesterone addition, and examined Mos accumulation and mobility, as well as the ability of GA to maintain MAP kinase inactive, 6 h later (Figure 1C). We did not detect any differences due to the timing of GA addition, suggesting that Mos is first synthesized in an unphosphorylated state, that this does not require Hsp90 and that there is a reasonable time window in which Hsp90 inhibition prevents subsequent phosphorylation of Mos.

Fig. 1. Mos accumulation in progesterone-stimulated oocytes with geldanamycin. (A) P: progesterone-treated (10 μg/ml in MMR) oocytes with 5 μM GA (+GA) added after 20 min were homogenized (10 oocytes/time point) in buffer A (see Materials and methods) and frozen in liquid nitrogen at the times indicated (min) after progesterone treatment. M: matured oocytes (360 min). Samples were resuspended in Laemmli buffer, run on SDS–PAGE (equivalent of three oocytes/lane) and Western blotted with anti–Mos antibody. None of the GA-treated oocytes underwent GVBD. (B) Stage VI (S), progesterone-treated (P) oocytes either with (+GA) or without GA treatment from 2 h before and onwards (GA+) or injected with antisense Mos oligos (+ as Mos) were homogenized in buffer A at 4 h after progesterone when controls (P) had undergone GVBD. Samples were analysed by Western blotting (two oocytes/lane) for Mos and MAP kinase. (C) A similar experiment to those in (A) and (B), but in which GA was either added 20 min before (–20′), at the same time as (0 h) or 20 min after (+20′) progesterone. P-MAPK: Western blot using anti-active MAP kinase antibody. Loading was the equivalent of two oocytes/lane. (D) Recombinant GST–sea urchin cyclin B protein (cycB) was microinjected into either untreated (–) oocytes or oocytes pre-treated (for 2 h) and maintained in GA (+GA) to compare induction of Mos translation and phosphorylation, and dependence on Hsp90 function, with control stage VI (S) and progesterone-matured (P) oocytes. All cyclin B-injected oocytes underwent GVBD and were homogenized in buffer A and analysed as above.

We reasoned that induction of Cdc2 kinase, other than by progesterone, should also lead to phosphorylation of Mos in an Hsp90-dependent fashion. We have previously reported that MAP kinase is not activated on microinjection of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–cyclin B in the presence of GA (Fisher et al., 1999a). In this experiment (Figure 1D), cyclin B injection, like progesterone treatment, provoked accumulation and mobility shift of Mos, but pre-treatment with GA prevented the mobility shift. This confirms the dependence of Mos phosphorylation on Hsp90 function.

Mobility shift of Mos has previously been demonstrated to be abolished by the mutation Ser3Ala (Nishizawa et al., 1992), and we confirmed by injection of in vitro synthesized 35S–labelled proteins that indeed the wild type but not the Ala3 mutant was phosphorylated rapidly and electrophoretically retarded on injection into mature but not stage VI oocytes (data not shown). The missing phosphorylation on Mos synthesized in the presence of GA is thus probably either Ser3 or a site or sites dependent on prior Ser3 phosphorylation. These results suggest that phosphorylation of Mos on Ser3 is a step in Mos activation, and that Hsp90-dependent Mos phosphorylation is required for Mos activation.

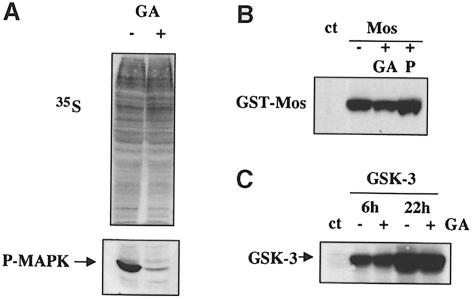

These results also suggested that Mos activation, rather than accumulation, may be inhibited by blocking Hsp90, a result consistent with our report that recombinant Mos protein does not activate MAP kinase on microinjection into oocytes in the presence of GA (Fisher et al., 1999a). Nevertheless, we wished to eliminate the possibility that GA has general effects on protein synthesis. We therefore examined the ability of GA-treated oocytes to incorporate 35S–labelled methionine into newly synthesized proteins (Figure 2A). Oocytes were either pre-treated with and maintained in 5 μM GA (+) or left untreated (–), and subsequently injected with 50 nl (0.5 μCi) of 35S–labelled methionine. One hour later, oocytes were lysed in Laemmli buffer, run on SDS–PAGE and incorporated label was analysed by autoradiography. GA treatment had no effect on this basal protein synthesis, although in the same batch of oocytes treated at the same time GA still inhibited progesterone-induced MAP kinase activation (Figure 2A, lower panel). Secondly, we analysed the ability of GA-treated oocytes to translate mRNA. Again oocytes were pre-treated and maintained in GA (+GA) or not (–), injected with RNA encoding kinase-dead GST–Mos, which does not induce GVBD, left to express for 6 h, and lysed and analysed by Western blot. GA had no effect on translation of injected mRNA (Figure 2B). We confirmed that this was a general phenomenon by analysing expression of mRNA for an unrelated kinase, GSK–3β, in the absence and presence of GA (Figure 2C), and a non-degradable version of the transcription factor β–catenin (data not shown). Thus, GA treatment does not affect general protein synthesis. In contrast, stimulation of injected oocytes to mature with progesterone did cause an increase in translation of injected mRNA in the same period of time (Figure 2B, +P), which was also a general effect (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Geldanamycin does not inhibit protein synthesis. (A) Upper panel: oocytes were treated (+) or not (–) with GA, and 2 h after GA addition were injected with 50 nl (0.5 μCi) of [35S]methionine. GA was maintained during a 1 h pulse, and label incorporation was analysed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography (two oocytes/lane). Lower panel: in the same experiment, instead of microinjection with label, oocytes were treated with progesterone (left-hand lane, without GA; right-hand lane, treated with GA as in upper panel), homogenized after 3 h when non-GA-treated samples had undergone GVBD, and analysed by Western blotting for active MAP kinase. (B) Control oocytes (ct) or oocytes injected with capped mRNA (∼25 ng) for kinase-dead GST–Mos, either pre-treated and maintained in GA (+GA) or subsequently treated with progesterone (+P), were homogenized after 6 h expression, and two oocytes/lane were analysed by Western blotting for Mos expression. (C) A similar experiment to that in (B) except that the mRNA injected (∼5 ng/oocyte) encoded GSK–3β, and two time points were taken at 6 and 22 h after mRNA injection.

Mos interacts with Hsp90 as well as Hsp70 in the oocyte

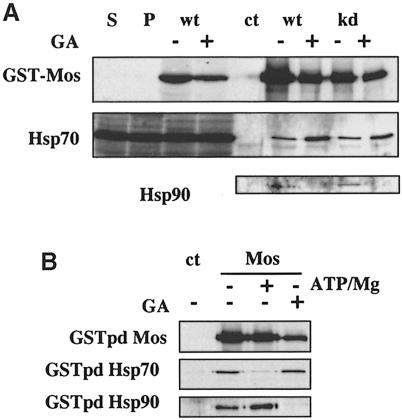

A recent report has found that Mos interacts with Hsp70 in Xenopus oocytes, although the function of this interaction is not clear and interaction with Hsp90 was not seen (Liu et al., 1999), implying that if such an interaction exists it is either labile, transient or of low abundance. Nevertheless, our results show that inhibition of Hsp90 interferes with Mos function. We therefore re-examined the possibility that Mos may associate with Hsp90 in vivo. We took advantage of a new system to detect protein–protein interations in Xenopus by GST pull-down of in vivo synthesized proteins (MacNicol et al., 1997). Mos expressed in this way indeed interacted with Hsp70, and we also found that Hsp90 is present in the Mos complexes (Figure 3A), although its presence is hard to detect. The Mos–Hsp90–Hsp70 complex did not depend on kinase activity of Mos since the kinase-dead version interacted to the same extent. Hsp90 was no longer present in the complex when oocytes were treated with GA, but Hsp70 was not only still present, but it actually interacted to a greater extent when interaction with Hsp90 was blocked (Figure 3A). This suggests that Mos interacts sequentially with Hsp70 and Hsp90 during its activation, that interaction with Hsp90 may well be transient and that interaction with Hsp90 leads to reduced binding of Hsp70. The S3E mutation, which mimics phosphorylation of Mos Ser3, did not increase the level of complexed Hsp90 over that of the kinase-dead version, and this interaction was also abolished in the presence of GA (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Mos interaction with Hsp90 in oocytes. Oocytes were microinjected with ∼25 ng of capped mRNA for GST–Mos, either wild type (wt) or kinase-dead (kd) mutant versions; oocytes were incubated overnight and homogenized in buffer A. GST pull-downs (GSTpd) were performed as described in Materials and methods, and total extracts or GST pull-downs were run on SDS–PAGE and Western blotted with either anti–Mos, anti-Hsp70 or anti-Hsp90 antibodies as indicated. (A) Lanes 1–4, total homogenates; lanes 5–8, GST pull-downs. S, stage VI oocytes; P, progesterone-treated mature oocytes; Mos, oocytes injected with wild-type GST–Mos mRNA; two oocytes/lane; GSTpd, GST pull-downs, the equivalent of 10 oocytes/lane; ct, control GST pull-down from progesterone-treated but non-injected mature oocytes. (B) A similar experiment to that in (A) using kinase-dead GST–Mos mRNA injection, but oocytes were either lysed normally or with 10 mM EDTA (lane 2) or 10 mM ATP + 20 mM MgCl2 (lane 3) added to the buffer. Additionally, 10% glycerol was added to the bead-washing steps to minimize labile complex disruption.

To try and find independent evidence for an inverse relationship between the association of Mos with Hsp70 and with Hsp90, we expressed kinase-dead Mos (to avoid possible confusion due to events potentially due to the activity of Mos) in oocytes and lysed them after overnight expression either in the presence of EDTA, to chelate magnesium and therefore potentially reduce Hsp90 function, or in the presence of high concentrations of ATP and magnesium (10 and 20 mM, respectively), potentially to stabilize an interaction with Hsp90. Although EDTA does not inhibit Hsp90 association, ATP/Mg does promote this interaction, and when the interaction with Hsp90 is stabilized a reduced interaction with Hsp70 is seen, to only just above background levels (Figure 3B). As before, if we inhibit Hsp90 function with GA, it no longer interacts with Mos, although Hsp70 can still interact (Figure 3B).

Mos-E3 still requires Hsp90 function to induce MAPK activation and GVBD

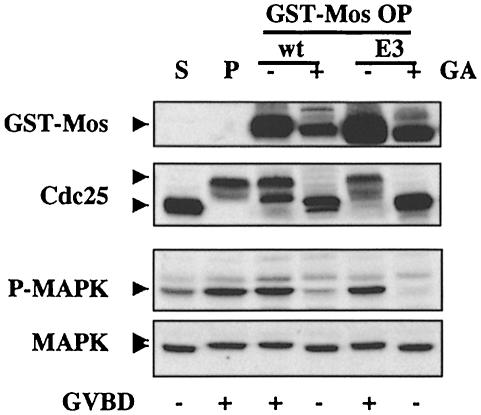

Since phosphorylation of Mos and the activation of MAPK by Mos are inhibited by interfering with Hsp90, and some reports suggest that phosphorylation of Mos Ser3 may be required for full activity, we wondered whether Mos activation might be due solely to this phosphorylation step. If so, the mutant S3E should no longer require functional Hsp90 to induce activation of MAP kinase. This was not the case (Figure 4). Even though Mos–E3 was as highly overexpressed as the wild type (Mos–WT), neither could induce GVBD (associated with Cdc25 hyperphosphorylation) nor activate MAP kinase in the presence of GA, although both were equally efficient in normal circumstances. Because, in the presence of GA, expression of the two Mos proteins could not induce GVBD and the associated increase in protein translation that occurs on oocyte maturation, Mos did not accumulate to the same extent as in non-treated samples. GA does not in itself inhibit the expression of these mRNAs (Figure 2B and data not shown).

Fig. 4. Mos S3E still requires Hsp90 function. Stage VI (S) and progesterone-matured (P) oocytes, and oocytes injected with capped mRNA for GST–Mos wild type (wt) and GST–Mos Glu (E3) and left overnight to overexpress (OP) the proteins, either incubated (+) or not (–) during expression in 5 μM GA (GA), were homogenized and processed as before, and Western blotted with Mos (GST–Mos), Cdc25, active MAP kinase (P–MAPK) and MAP kinase (MAPK) antibodies. Extracts equivalent to three oocytes were loaded per lane. In this experiment, a small but significant activation of MAP kinase was detected in non-hormone-stimulated oocytes. Such a small activation, not associated with a detectable shift of ERK2 electrophoretic mobility, although not observed systematically, is not unusual in stage VI oocytes.

These results imply that an Hsp90-dependent event subsequent to Mos-S3 phosphorylation is important for Mos activation.

Mos is not activated without functional Hsp90

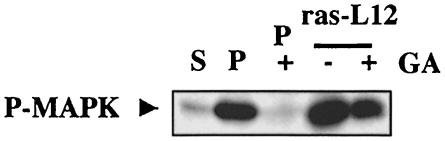

The above results demonstrate that Mos-induced activation of MAP kinase requires Hsp90 function but do not allow us to define the target of Hsp90 in this cascade of events. Moreover, MAP kinase activation has been reported to require both Mos kinase (Roy et al., 1996) and Raf–1 kinase in Xenopus (Fabian et al., 1993; Muslin et al., 1993). Raf–1 has been shown not to be required for Mos-dependent MAP kinase activation in Xenopus oocytes (Shibuya et al., 1996), while MAP kinase activation has been reported to control Mos activity positively on the basis of in vitro experiments (Huang and Ferrell, 1996). To examine whether MAP kinase itself could require Hsp90 function in order to be activated, we sought to activate a MAP kinase-activating pathway that does not require Mos. In Xenopus oocytes, oncogenic ras-induced GVBD does not require Mos synthesis (Daar et al., 1991) nor, apparently, any other protein synthesis (Allende et al., 1988; Nebreda et al., 1993). We therefore examined whether oncogenic ras-mediated activation of MAP kinase requires Hsp90 function, by injecting recombinant Ras–Lys12, a constitutively active form of ras, in the absence and presence of GA. If Mos is indeed a target of Hsp90 inhibition, we might expect that Ras–Lys12 may activate MAP kinase in the absence of Hsp90 function. This was indeed the case: ras–Lys12 protein injection induced GVBD and MAPK activation (Figure 5) whether or not GA, which as usual inhibited progesterone-induced MAPK activation, was present. This demonstrates that Hsp90 function is not essential for activation of MAP kinase per se, and reinforces the idea that Hsp90 inhibition specifically targets Mos.

Fig. 5. Oncogenic ras activates the MAP kinase cascade in the absence of Hsp90 function. Stage VI (S), progesterone-treated matured (P) or non-mature oocytes, treated with 5 μM GA after 1 h, and oocytes either incubated (+) or not (–) in 5 μM GA, injected with recombinant GST–Ras-Lys12 protein, were processed as described in legend to Figure 4 (equivalent of three oocytes per lane except for the last lane, equivalent to 1.5 oocytes) and Western blotted with an active MAP kinase antibody.

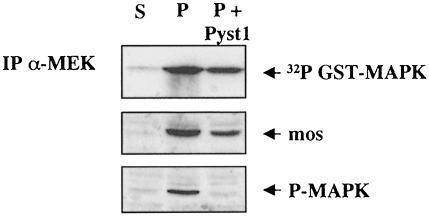

These results point to a requirement for Hsp90 in progesterone-stimulated activation of MEK by Mos. We tested this hypothesis directly by measuring MEK activity using recombinant GST–MAP kinase as a substrate, either in total lysates (Figure 6A, first four lanes) or on immunoprecipitation of endogenous MEK from the lysates (Figure 6A, right-hand five lanes). MEK was inactive in stage VI oocytes (S), active in progesterone-treated mature oocytes (P), but not if treated with GA during the window in which Mos phosphorylation can be prevented (P + GA). Thus, the underphosphorylated Mos that accumulates (Figure 6B) is incapable of activating MEK in the absence of Hsp90 function.

Fig. 6. MEK is not activated by newly translated Mos in the absence of Hsp90 function. Stage VI (S), progesterone-treated mature oocytes (P) or oocytes treated with progesterone to which 5 μM GA was added after 1 h (P + GA) were homogenized in buffer A and frozen in liquid nitrogen. (A) An aliquot of each sample (equivalent to one oocyte) was incubated in a total MEK kinase assay using recombinant GST–MAP kinase as described in Materials and methods (–, the control kinase assay in the absence of oocyte extract demonstrates that the low intensity band is due to background autophosphorylation or fixation of ATP by the substrate GST–MAP kinase), while most of the remainder of each sample (equivalent to 20 oocytes) was used to immunoprecipitate MEK, with either a pre-immune (Pr) or immune (Im) serum, and the washed pellet was used in a MEK kinase assay using recombinant GST–MAP kinase. Kinase assays were stopped by heating in Laemmli buffer, resolved on SDS–PAGE and the dried gel was autoradiographed to reveal phosphorylated GST–MAP kinase. (B) Another aliquot of each sample was resuspended in Laemmli buffer for total Western blots using the antibodies indicated.

Since MAP kinase can phosphorylate Mos on Ser3, we wished to determine whether the lack of activation of MEK is indirect, due to a lack of MAP kinase, or whether GA has a direct effect on Mos kinase. To achieve this, we overexpressed the MAP kinase phosphatase Pyst1, which blocks MAP kinase activation in Xenopus oocytes (Fisher et al., 1999a). No MAP kinase activity could be detected, but Mos accumulates (albeit to a lower level in oocytes that do not undergo GVBD, due to the suppression of MAP kinase activity) and migrates at the same mobility as fully active Mos, and MEK is activated (Figure 7). This suggests, but still does not prove directly, that Mos enzymatic activity is targeted directly by inhibition of Hsp90.

Fig. 7. Active MAP kinase is not required for MEK activation by newly translated Mos. Stage VI (S), progesterone-matured (P) and progesterone-treated oocytes pre-injected with ∼10 ng of capped mRNA for Pyst1 and incubated overnight before progesterone treatment were subjected to total Western blots for Mos and active MAP kinase, and MEK immunoprecipitation kinase assays as described in Figure 6.

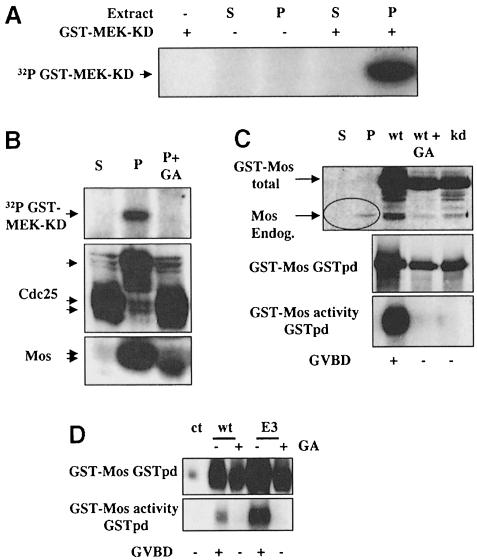

Measurement of Mos kinase activity by immuno– precipitation from Xenopus oocytes is notoriously difficult (e.g. see Liu et al., 1999). It is theoretically possible that underphosphorylated Mos could phosphorylate MEK without activating its kinase activity. We therefore assayed total kinase activity against kinase-dead GST–MEK in extracts of Xenopus oocytes in normal circumstances or circumstances in which Mos is underphosphorylated and may be inactive. The results exclude the possibility that Mos phosphorylates MEK without activating it: control progesterone-treated oocytes contained abundant activity able to phosphorylate MEK (Figure 8A and B, upper panel), while treatment of oocytes with GA abolished this activity, and accumulated Mos remained in its underphosphorylated form (Figure 8B, upper and lower panels). In these oocytes, GA suppressed hyperphosphorylation of Cdc25 and GVBD (Figure 8B, middle panel).

Fig. 8. In vivo translated Mos requires Hsp90 function for expression of its kinase activity. (A) Preparatory experiment in which total stage VI (S) or progesterone-matured (P) oocyte extracts (one oocyte/lane) were incubated in a kinase assay using kinase-dead GST–MEK as described in Materials and methods. (–) and (+) indicate the absence or presence of kinase-dead GST–MEK substrate or (lane 1 only) extract. (B) The experiment was then repeated (lower three panels) with stage VI (S), progesterone-matured (P) or progesterone and GA-treated (5 μM, 1 h after progesterone) oocytes. An aliquot of the total extract was Western blotted for Cdc25 and Mos (lower two panels). (C) Capped mRNA for wild-type (wt) or kinase-dead (kd) GST–Mos was injected into oocytes (25 ng/oocyte), a subset of which were incubated in 5 μM GA (wt + GA), and oocytes were incubated overnight and homogenized in buffer A. In vivo translated Mos was recovered from the extracts by pull-down from 100 μl of extract on glutathione–Sepharose beads (GSTpd) and either run on SDS–PAGE and Western blotted to estimate recovery (middle panel, equivalent of 10 oocytes/lane) or incubated in a Mos kinase assay (lower panel, equivalent of 10 oocytes/assay) followed by resolution and auto- radiography on SDS–PAGE. The upper panel shows Western blots of total oocyte extracts (three oocytes per lane) from this experiment, as well as control stage VI (S) and progesterone-treated (P) oocytes not overexpressing GST–Mos, in which synthesized endogenous Mos is indicated. Slightly less Mos protein is synthesized in GA-treated or kinase-dead Mos-injected oocytes since they did not undergo GVBD, which enhances general protein translation. (D) A similar experiment to that in (B) was performed using mRNA for wild-type (wt) and S3E Mos–GST; ct, GST pull-down from progesterone-matured oocytes not injected with Mos mRNA.

To test further whether activation of in vivo translated Mos requires Hsp90 function, we overexpressed GST–Mos in vivo and assayed its intrinsic kinase activity by autophosphorylation of GST pull-downs. We overexpressed either GST–Xenopus Mos wild-type (WT), S3E or kinase-dead (KD) proteins by injection of the corresponding mRNAs. Only GST–Mos–WT and Mos–E3 in the absence of GA activated the MAP kinase cascade, caused GVBD and possessed intrinsic autophosphorylation activity (Figure 8C and D), even though in the presence of GA the Mos proteins were expressed at a much higher level (Figure 8C, upper panel) than the endogenous Mos, which accumulates on progesterone-induced maturation. This directly demonstrates that GST–Mos requires Hsp90 function in order to acquire activity as a kinase.

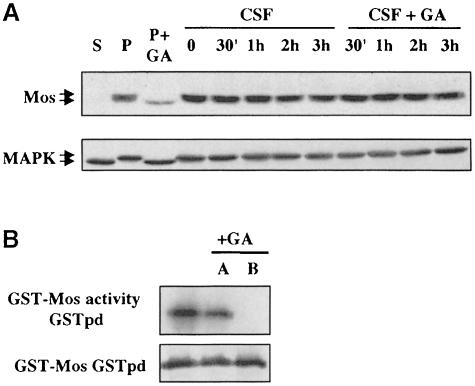

Hsp90 is not required for maintenance of Mos kinase activity

We wished to know whether Hsp90 is required continually for Mos activity, or only for Mos activation. Circumstantial evidence suggested that Hsp90 is only required for Mos activation: first, the abundance of Hsp90 in Mos complexes is low or unstable; secondly, GA treatment cannot mimic calcium treatment and induce dephosphorylation of Mos, inactivation of MAP kinase and exit from a CSF extract (data not shown). Thirdly, on progesterone stimulation, there is a time window in which GA addition inhibits Mos and MAP kinase activation, but after which Mos and MAP kinase go on to be phosphorylated and activated in spite of the presence of GA (data not shown). Also, as shown in Figure 9A, incubation of oocytes arrested in meiosis II in GA does not lead to dephosphor– ylation and inactivation of Mos and MAP kinase. Thus, GA inhibits only the step in which Mos activation occurs, and cannot inactivate Mos that has already passed this step. To analyse directly whether Hsp90 is still required for kinase activity once Mos has already been activated, we analysed kinase activity of GST–Mos expressed in oocytes by GST pull-down kinase assays (Figure 9B). In this experiment, GA was either absent, present in the oocyte medium before (B) expression to block activation of Mos or present afterwards (A) during the GST pull-down and throughout the kinase assay, to assess the requirement for maintenance of Mos activity. While it completely blocks activation of GST–Mos, GA no longer prevents Mos kinase activity once Mos is active.

Fig. 9. Activated Mos no longer requires Hsp90 function for maintenance of kinase activity. (A) CSF-arrested oocytes (CSF) were treated with GA during a 3 h time course (+GA) or left untreated. The phosphorylation status of Mos and MAP kinase was analysed by Western blotting and compared with stage VI (S) and progesterone-treated (P) oocytes either additionally treated (+GA) or not with GA (2 h before progesterone addition). (B) A similar experiment to that shown in Figure 8B: all oocytes were injected with capped mRNA for wild-type GST–Mos, and Mos autophosphorylation was measured on GST pull-down (GSTpd) from oocytes not treated at all with GA (lane 1) or treated with GA after (A) expression of Mos, GVBD and homogenization, prior to GST pull-down and during the kinase assay, or before (B) microinjection and in vivo expression.

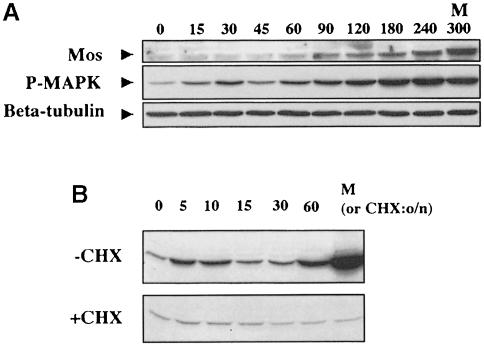

Two-phase MAP kinase activation in Xenopus oocytes

The above results show that Mos is inactive in the absence of an Hsp90-dependent event, coincident with Mos phosphorylation. However, we have recently reported that MAP kinase is activated to a low level early in response to progesterone. This infers that activation of MAP kinase may be a coordinate response to Mos-dependent and -independent activation steps. To define the activation curve of MAP kinase more precisely, we performed a detailed time course, as shown in Figure 10A. This shows first that an increase in MAP kinase phosphorylation is detectable as early as 15 min after progesterone addition, in advance of a detectable increase in Mos protein level. Secondly, surprisingly, there is apparently an early peak in MAP kinase phosphorylation, at 30 min in this experiment, before a later large-scale increase. This is not an artefact of inaccurate gel loading since β–tubulin is constant throughout (lower panel). An alternative explanation, which we cannot yet rule out, is that there are two MAP kinases in which the active form migrates at the same size, and one is activated early while the other is activated later.

Fig. 10. Biphasic MAP kinase activation: dependence on Mos function. (A) A progesterone time course (in minutes after Pg addition) was analysed by Western blotting for the proteins indicated; three oocytes were loaded per lane. (B) Experiment in which oocytes were treated with progesterone with (+CHX) or without (–CHX) prior and continued presence of 20 μg/ml cycloheximide, and fixed at the times indicated (in minutes after progesterone addition) for analysis with active MAP kinase antibody by Western blotting.

We then tested the requirement for protein synthesis in early activation of MAP kinase. Figure 10B demonstrates that 20 μg/ml cycloheximide treatment prior to and during the progesterone time course abolishes both phases of MAP kinase activation; thus, even if the early peak of MAP kinase is independent of Mos, it requires synthesis of an as yet unidentified protein.

Discussion

It has been known for some time that Mos activates the MAP kinase cascade during meiosis in vertebrate oocytes and it has recently become clear that Mos-mediated control of MAP kinase is critical for the correct ordering and timing of events at the beginning of development, including suppression of DNA replication in meiosis and prevention of parthenogenetic activation (see Sagata, 1997). Nevertheless, the mechanism of activation of Mos itself has not been determined. Here we describe a system that allows investigation of the mechanism of activation of the Mos protein kinase by uncoupling its synthesis and activation.

Although a recent report has demonstrated an interaction between Mos and Hsp70, the functional significance of this interaction is unknown (Liu et al., 1999). We demonstrate here that Mos interacts with another chaperone, Hsp90, and that this interaction is essential for its activation. Furthermore, we show an inverse relationship between the association of Mos with Hsp90 and its association with Hsp70.

Hsp90 has recently been described as a cofactor for several protein kinases, including casein kinase II, the cell cycle kinases Wee1 and Cdk4, and the proto-oncogenes Raf–1 and Src, as well as a modulator for a variety of other proteins including the heat-shock transcription factor HSF1, the steroid receptors for glucocorticoid and progesterone, and the centrosomal protein centrin (for a review, see Caplan, 1999). Hsp90 is inhibited efficiently by the anti-tumour agent GA, which binds to a region involved in ATP binding. This agent is extremely potent in prevention of activation of MAP kinase in Xenopus oocytes (Fisher et al., 1999a), and we show here that this inhibition can be explained by an inhibition of the mechanism that activates Mos kinase.

We find that prevention of Mos association with Hsp90 by GA abolishes not only its kinase activity but also its phosphorylation-induced SDS–PAGE mobility shift, due to Ser3 phosphorylation (Nishizawa et al., 1992). This correlation suggests that Ser3 phosphorylation may be required for c–Mos activation in Xenopus oocytes, and indeed the S3A mutant does not interact efficiently with MEK in vitro, and fails to activate endogenous ERK1 and ERK2 when expressed in reticulocyte lysates, in contrast to wild-type c–Mos (Chen et al., 1995). The view that Ser3 phosphorylation is required for c–Mos activity has been challenged because S3A mutants readily induce GVBD when microinjected into G2-arrested oocytes (Freeman et al., 1992; Nishizawa et al., 1992), although protein kinase activity of this mutant was not documented directly in these experiments. Mos S3A possesses either no, or very low kinase activity (Yang et al., 1998), and it is likely that microinjection of S3A leads to translation and activation of endogenous c–Mos, possibly by activation of MAP kinase to a low but sufficient level to stimulate endogenous Mos translation, and/or by titration of an inhibitor. Putative inhibitors of c–Mos include the β–subunit of casein kinase II, which, when ectopically expressed, has been shown to inhibit c–Mos activation and meiotic maturation, and a complex between this protein and endogenous c–Mos has been detected (Chen et al., 1997). Ser3 has been reported to be important for the interaction with Hsp70 (Liu et al., 1999), although we show here that binding of Hsp70, while not impaired by GA, is not sufficient to allow Ser3 phosphorylation and c–Mos activation.

Although Ser3 phosphorylation is almost certainly required for c–Mos activity, Hsp90 function is not only required for this event. S3E, which, in contrast to S3A, readily induces cleavage arrest when microinjected into the blastomere of a two-cell embryo (Nishizawa et al., 1992), still requires Hsp90 function for expression of its protein kinase activity. Mos possesses an autoinhibitory loop, near the active site, which must be repositioned in order to allow expression of the kinase activity (Robertson and Donoghue, 1996). Interaction with Hsp90 may well mediate the repositioning of this region. It is also possible that subsequent phosphorylation could stabilize this conformation change, eliminating a further requirement for Hsp90 in maintenance of Mos activity.

Translation of c–Mos in progesterone-stimulated oocytes requires unmasking and polyadenylation of stored mRNA (Sheets et al., 1995). A surprising aspect of this translational control is that it apparently requires MAP kinase activation (Howard et al., 1999) even though MAP kinase activation is supposedly downstream of Mos. We nevertheless show that Mos accumulation does not require Hsp90 activity and occurs even if we can no longer detect MAP kinase activity.

Although we have been unable to provide supporting evidence, it is possible that the early low level of MAP kinase activation after progesterone stimulation (Fisher et al., 1999a) could be due to Raf–1. Hsp90 could also be required for Raf–1 function, as is the case in mammalian cells, as well as Mos, and Raf–1 might be activated early while Mos is activated later. Indeed, we have shown that if Hsp90 is inhibited at the same time as progesterone stimulation, no MAPK activation is observed (Fisher et al., 1999a; this study). Another possibility is that B-raf, rather than Raf–1, is responsible, since a ras-dependent activator of MAP kinase from Xenopus eggs has been purified and identified as B–raf (Kuroda et al., 1995; Yamamori et al., 1995). A model could place Raf–1 or B-raf at the cortex where it would be activated early after the binding of progesterone to its receptor. This would permit the early low level of MAP kinase activation.

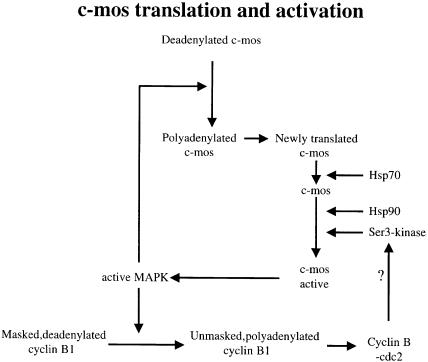

Newly synthesized non-phosphorylated Mos is degraded (Watanabe et al., 1989; Nishizawa et al., 1992), while association with Hsp70 may stabilize the protein (Liu et al., 1999), perhaps by preventing its proteolysis. Binding of Hsp90 probably occurs after that of Hsp70, since GA does not prevent (and may increase) Hsp70 binding while ATP promotes Hsp70 dissociation and Hsp90 binding. Binding of Hsp90 fulfils two roles in the process of c–Mos activation. One is to allow Ser3 phosphorylation. Several Ser3 kinases have been proposed, including MAP kinase and Cdc2–cyclin B, for which Mos Ser3 fulfils consensus site requirements. We demonstrate here that MAP kinase cannot be the only kinase responsible for Mos Ser3 phosphorylation, since phosphorylation and activation of Mos occur even if MAP kinase is maintained inactive by expression of Pyst1. Cdc2–cyclin B kinase is therefore the best candidate. In both vertebrate and invertebrate oocytes, translation of cyclin B dramatically increases after GVBD, leading to increased Cdc2 kinase activity, and this requires MAP kinase activation. We show here that cyclin B microinjection-induced GVBD causes a shift in mobility of Mos, i.e. Mos phosphorylation, while this does not occur, and MAP kinase is not activated, if Hsp90 is inhibited. We therefore speculate that the kinase which phosphorylates and activates Mos may be Cdc2–cyclin. In agreement with this view, dominant-negative Cdc2 mutants or inactivating Cdc2 antibodies prevent activation of at least the majority of MAP kinase activation (Nebreda et al., 1995). Furthermore, MAP kinase activation is downstream of Cdc2 activation in starfish and mouse oocytes. Still, MAP kinase activation is required for high-level Cdc2 activation in Xenopus oocytes (Fisher et al., 1999a). This, along with a two-phase MAP kinase activation (early low level, late high level due to Mos activation) provides a conceptual basis for the feedback loop of MAP kinase and Cdc2 activation (Figure 11). The missing link is the step at which MAP kinase promotes Cdc2 activation; on the basis of other reports (Ballantyne et al., 1997), we have suggested that the low and even transient early level could stimulate cyclin synthesis (Fisher et al., 1999a), or possibly cyclin relocalization in the cytoplasm, while the late high level could act by inhibiting Myt1 via activation of p90rsk (Palmer et al., 1998). In conclusion, chaperone-mediated activation of Mos is a key step in the feedback loops controlling MAP kinase and MPF activation in Xenopus oocytes.

Fig. 11. Model for the control of MAP kinase and Cdc2 activation in Xenopus oocytes and the role of chaperone proteins. See text for details.

Materials and methods

Recombinant mRNAs and proteins

The GST–sea urchin cyclin B and pSG5-Pyst1 constructs and antibodies have been described previously (Abrieu et al., 1996; Groom et al., 1996). The vectors encoding GST–MAP kinase and kinase-dead GST–MEK were kindly provided by Chris Marshall and Daniel Donoghue, respectively, and the recombinant proteins were produced using the published protocol (Alessi et al., 1995). Mos wild-type, S3E and kinase-dead genes were cloned into the Xenopus expression vector pXen1 (MacNicol et al., 1997) to allow production of GST-tagged Mos mRNA by SP6 in vitro transcription. Capped mRNAs were transcribed by standard procedures (Promega).

Xenopus oocytes

Oocyte manipulations, in MMR (5 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 1.1 M NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2), and extracts in buffer A [20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM β–glycerophosphate, 5 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM benzamidine] were performed as described (Fisher et al., 1999b). GA was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 5 μmol/ml and diluted in MMR to the concentration indicated (usually 5 μM).

Immunological procedures

The Xenopus anti–Mos, anti-ERK and anti-active ERK antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz (sc–086, sc–94 and sc–7383, respectively). Other antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal antisera against Xenopus full-length recombinant Cdc25, anti-Xenopus MEK C–terminal peptide, the polyclonal anti-pleurodeles Hsp90 antibody kindly provided by Patrick Coumailleau (Coumailleau et al., 1995), and monoclonal anti-chicken Hsp70 antibody BB70 and Hsp90 antibody 4F3 (Uzawa et al., 1995), both kindly provided by David Toft. Immunoprecipitations for kinase assays were performed as described (Fisher et al., 1999b). Protein A–Sepharose immune complexes were washed twice in buffer A and once in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT.

Western blots were probed with primary antibody at 50 ng/ml and the appropriate secondary antibody–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate diluted according to recommendations (Sigma) and revealed by ECL.

Kinase assays

Total MAPKKK activity in oocyte extracts was determined using 5 μl of extract per assay (equivalent to one oocyte) in 25 μl of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 200 μM ATP, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 5 μCi of [32P]ATP) containing 5 μg of GST–MAP kinase for 30 min at 25°C; total and immunoprecipitated MEK activity was assayed using the same reaction but with 1 μg of kinase-dead GST–MEK. GST–Mos was recovered from diluted oocyte extracts (usually 20 oocytes/500 μl) in buffer A with 20 μl (for 500 μl) of 50% glutathione–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia), washed twice in buffer A with 0.25 M NaCl, rinsed in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 150 mM NaCl and assayed for 30 min at 25°C in 25 μl of reaction buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM MnCl2, 2 mM DTT, 50 μM ATP, 5 μCi of [32P]ATP). Assays were stopped by heating to 100°C for 5 min in Laemmli buffer, and half the reaction was loaded on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel.

Antisense Mos oligonucleotides

Antisense oligonucleotides were based on those already tested in Xenopus oocytes (Sagata et al., 1988), in this case CATATCCTTGCTTGTATTTTCAGTGC. Oligonucleotides were dissolved in water at 2 μg/μl, and 50 nl were microinjected into stage VI oocytes, which were left for 30 min before progesterone treatment.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank those scientists who kindly provided us with reagents (see Materials and methods). D.L.F. was supported by a TMR Marie Curie fellowship of the European Commission and is currently funded by INSERM. E.M. is supported by the CNRS and ARC (grant no. 9827).

References

- Abrieu A., Lorca,T., Labbé,J.C., Morin,N., Keyse,S. and Dorée,M. (1996) MAP kinase does not inactivate, but rather prevents the cyclin degradation pathway from being turned on in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Sci., 109, 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrieu A., Fisher,D., Simon,M.N., Dorée,M. and Picard,A. (1997) MAPK inactivation is required for the G2 to M-phase transition of the first mitotic cell-cycle. EMBO J., 16, 6407–6413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi D.R., Cohen,P., Ashworth,A., Cowley,S., Leevers,S.J. and Marshall,C.J. (1995) Assay and expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase, MAP kinase kinase and raf. Methods Enzymol., 255, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende C.C., Hinrichs,M.V., Santos,E. and Allende,J.E. (1988) Oncogenic ras protein induces meiotic maturation of amphibian oocytes in the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors. FEBS Lett., 234, 426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne S., Daniel,D.L.J. and Wickens,M. (1997) A dependent pathway of cytoplasmic polyadenylation reactions linked to cell cycle control by c-mos and CDK1 activation. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 1633–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitangcol J.C., Chau,A.S., Stadnick,E., Lohka,M.J., Dicken,B. and Shibuya,E.K. (1998) Activation of the p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibits Cdc2 activation and entry into M-phase in cycling Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 451–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan A.J. (1999) Hsp90's secrets unfold: new insights from structural and functional studies. Trends Cell Biol., 9, 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. and Cooper,J.A. (1995) Ser-3 is important for regulating Mos interaction with and stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 4727–4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Li,D., Krebs,E.G. and Cooper,J.A. (1997) The casein kinase II β subunit binds to Mos and inhibits Mos activity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 1904–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge W.H., Carlton,M.B., Udy,G.B. and Evans,M.J. (1994) Disruption of c-mos causes parthenogenetic development of unfertilized mouse eggs. Nature, 370, 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumailleau P., Billoud,B., Sourrouille,P., Moreau,N. and Angelier,N. (1995) Evidence for a 90 kDa heat-shock protein gene expression in the amphibian oocyte. Dev. Biol., 168, 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar I., Nebreda,A.R., Yew,N., Sass,P., Paules,R., Santos,E., Wigler,M. and Vande Woude,G.F. (1991) The ras oncoprotein and M-phase activity. Science, 253, 74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian J.R., Morrison,D.K. and Daar,I.O. (1993) Requirement for Raf and MAP kinase function during the meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes. J. Cell Biol., 122, 645–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell J.E. Jr (1999) Xenopus oocyte maturation: new lessons from a good egg. BioEssays, 21, 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D.L., Abrieu,A., Simon,M.N., Keyse,S., Vergé,V., Dorée,M. and Picard,A. (1998) MAP kinase inactivation is required only for G2–M phase transition in early embryogenesis cell cycles of the starfishes Marthasterias glacialis and Astropectens aranciacus. Dev. Biol., 202, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D.L., Brassac,T., Galas,S. and Dorée,M. (1999a) Dissociation of MAP kinase activation and MPF activation in hormone-stimulated maturation of Xenopus oocytes. Development, 126, 4537–4546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D.L., Morin,N. and Dorée,M. (1999b) A novel role for glycogen synthase kinase-3 in Xenopus development: maintenance of oocyte cell cycle arrest by a β-catenin-independent mechanism. Development, 126, 567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R.S., Meyer,A.N., Li,J. and Donoghue,D.J. (1992) Phosphorylation of conserved serine residues does not regulate the ability of mosxe protein kinase to induce oocyte maturation or function as cytostatic factor. J. Cell Biol., 116, 725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno N., Nishizawa,M., Okazaki,K., Tanaka,H., Iwashita,J., Nakajo,N., Ogawa,Y. and Sagata,N. (1994) Suppression of DNA replication via Mos function during meiotic divisions in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 13, 2399–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer F., Xu,W., Cooper,G.M. and Richter,J.D. (1994) Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA is necessary for oocyte maturation in the mouse. EMBO J., 13, 5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groom L.A., Sneddon,A.A., Alessi,D.R., Dowd,S. and Keyse,S.M. (1996) Differential regulation of the MAP, SAP and RK/p38 kinases by Pyst1, a novel cytosolic dual-specificity phosphatase. EMBO J., 15, 3621–3632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haccard O., Sarcevic,B., Lewellyn,A., Hartley,R., Roy,L., Izumi,T. and Maller,J.L. (1993) Induction of metaphase arrest in cleaving Xenopus embryos by MAP kinase. Science, 262, 1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N. et al. (1994) Parthenogenetic activation of oocytes in c–mos-deficient mice. Nature, 370, 68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard E.L., Charlesworth,A., Welk,J. and MacNicol,A.M. (1999) The mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway stimulates mos mRNA cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1990–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.Y.F. and Ferrell,J.E. (1996) Dependence of Mos-induced Cdc2 activation on MAP kinase function in a cell-free system. EMBO J., 15, 2169–2173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda S., Shimizu,K., Yamamori,B., Matsuda,S., Imazumi,K., Kaibuchi,K. and Takai,Y. (1995) Purification and characterization of REKS from Xenopus eggs. Identification of REKS as a Ras-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 2460–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Vuyyuru,V.B., Pham,C.D., Yang,Y. and Singh,B. (1999) Evidence of an interaction between Mos and Hsp70: a role of the Mos residue serine 3 in mediating Hsp70 association. Oncogene, 18, 3461–3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorca T., Galas,S., Fesquet,D., Devault,A., Cavadore,J.C. and Dorée,M. (1991) Degradation of the proto-oncogene product p39mos is not necessary for cyclin proteolysis and exit from meiotic metaphase: requirement for a Ca2+–calmodulin dependent event. EMBO J., 10, 2087–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNicol M.C., Pot,D. and MacNicol,A. (1997) pXen, a utility vector for the expression of GST-fusion proteins in Xenopus laevis oocytes and embryos. Gene, 196, 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matten W.T., Copeland,T.D., Ahn,N.G. and Vande Woude,G.F. (1996) Positive feedback between MAP kinase and Mos during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Dev. Biol., 179, 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslin A.J., MacNicol,A.M. and Williams,L.T. (1993) Raf–1 protein kinase is important for progesterone-induced Xenopus oocyte maturation and acts downstream of mos. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 4197–4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebreda A.R., Porras,A. and Santos,E. (1993) p21ras-induced meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes in the absence of protein synthesis: MPF activation is preceded by activation of MAP and S6 kinases. Oncogene, 8, 467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebreda A.R., Gannon,J.V. and Hunt,T. (1995) Newly synthesized protein(s) must associate with p34cdc2 to activate MAP kinase and MPF during progesterone-induced maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 14, 5597–5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa M., Okazaki,K., Furuno,N., Watanabe,N. and Sagata,N. (1992) The ‘second-codon rule’ and autophosphorylation govern the stability and activity of Mos during the meiotic cell cycle in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 11, 2433–2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A., Gavin,A.C. and Nebreda,A.R. (1998) A link between MAP kinase and p34 (cdc2)/cyclin B during oocyte maturation: p90 (rsk) phosphorylates and inactivates the p34 (cdc2) inhibitory kinase Myt1. EMBO J., 17, 5037–5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham C.D., Vuyyuru,V.B., Yang,Y., Bai,W. and Singh,B. (1999) Evidence for an important role of serine 16 and its phosphorylation in the stabilization of c–Mos. Oncogene, 18, 4287–4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard A., Galas,S., Peaucellier,G. and Dorée,M. (1996) Newly assembled cyclin B–cdc2 kinase is required to suppress DNA replication between meiosis I and meiosis II in starfish oocytes. EMBO J., 15, 3590–3598. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S.C. and Donoghue,D.J. (1996) Identification of an autoinhibitory region in the activation loop of the Mos protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3472–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy L.M., Haccard,O., Izumi,T., Lattes,B.G., Lewellyn,A.L. and Maller,J.L. (1996) Mos proto-oncogene function during oocyte maturation in Xenopus. Oncogene, 12, 2203–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N. (1997) What does Mos do in oocytes and somatic cells? BioEssays, 19, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N., Oskarsson,M., Copeland,T., Brumbaugh,J. and Vande Woude,G.F. (1988) Function of c-mos proto-oncogene product in meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes. Nature, 335, 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets M.D., Wu,M. and Wickens,M. (1995) Polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA as a control point in Xenopus meiotic maturation. Nature, 374, 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya E.K., Morris,J., Rapp,U.R. and Ruderman,J.V. (1996) Activation of the Xenopus oocyte mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by Mos is independent of Raf. Cell Growth Differ., 7, 235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana K., Machida,T., Nomura,Y. and Kishimoto,T. (1997) MAP kinase links the fertilization signal transduction pathway to the G1/S-phase transition in starfish eggs. EMBO J., 16, 4333–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa M., Grams,J., Madden,B., Toft,D. and Salisbury,J.L. (1995) Identification of a complex between centrin and heat shock proteins in CSF-arrested Xenopus oocytes and dissociation of the complex following oocyte activation. Dev. Biol., 171, 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S.A., Guadagno,T.M. and Ferrell,J.E.J. (1997) Induction of a G2-phase arrest in Xenopus egg extracts by activation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 2157–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N., Vande Woude,G.F., Ikawa,Y. and Sagata,N. (1989) Specific proteolysis of the c-mos proto-oncogene product by calpain on fertilization of Xenopus eggs. Nature, 342, 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N., Hunt,T., Ikawa,Y. and Sagata,N. (1991) Independent inactivation of MPF and cytostatic factor (Mos) upon fertilization of Xenopus eggs. Nature, 352, 247–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamori B., Kuroda,S., Shimizu,K., Fukui,K., Ohtsuka,T. and Takai,Y. (1995) Purification of a Ras-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase from bovine brain cytosol and its identification as a complex of B-Raf and 14-3-3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 11723–11726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Pham,C.D., Vuyyuru,V.B., Liu,H., Arlinghaus,R. and Singh,B. (1998) Evidence of a functional interaction between serine 3 and serine 25 Mos phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 15946–15953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]