Abstract

Background

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) are common and difficult to treat.

Aim

To investigate the effectiveness of adding five-element acupuncture to usual care in ‘frequent attenders’ with MUPS.

Design and setting

Randomised controlled trial in four London general practices.

Method

Participants were 80 adults with MUPS, consulting GPs ≥8 times/year. The intervention was individualised five-element acupuncture, ≥12 sessions, immediately (acupuncture group) and after 26 weeks (control group). The primary outcome was 26-week Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP); secondary outcomes were wellbeing (W-BQ12), EQ-5D, and GP consultation rate. Intention-to-treat analysis was used, adjusting for baseline outcomes.

Results

Participants (80% female, mean age 50 years, mixed ethnicity) had high health-resource use. Problems were 59% musculoskeletal; 65% >1 year duration. The 26-week questionnaire response rate was 89%. Compared to baseline, the mean 26-week MYMOP improved by 1.0 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.4 to 1.5) in the acupuncture group and 0.6 (95% CI = 0.3 to 0.9) in the control group (adjusted mean difference: acupuncture versus control –0.6 [95% CI = –1.1 to 0] P = 0.05). Other between-group adjusted mean differences were: W-BQ12 4.4 (95% CI = 1.6 to 7.2) P = 0.002; EQ-5D index 0.03 (95% CI = –0.11 to 0.16) P = 0.70; consultation rate ratio 0.90 (95% CI = 0.70 to 1.15) P = 0.4; and number of medications 0.56 (95% CI = 0.47 to 1.6) P = 0.28. All differences favoured the acupuncture group. Imputation for missing values reduced the MYMOP adjusted mean difference to –0.4 (95% CI = –0.9 to 0.1) P = 0.12. Improvements in MYMOP and W-BQ12 were maintained at 52 weeks.

Conclusion

The addition of 12 sessions of five-element acupuncture to usual care resulted in improved health status and wellbeing that was sustained for 12 months.

Keywords: acupuncture, chronic disease, medically unexplained symptoms, primary care, randomised controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

People who have persistent physical symptoms that cannot be explained by current medical knowledge (‘medically unexplained physical symptoms’ [MUPS]) make up 11–19% of UK GP consultations,1,2 and up to 50% of new referrals to outpatient clinics.3 These people are often ‘frequent attenders’ in primary care,4 and are costly both to the NHS,4,5 and as recipients of long-term sick leave.6,7 In addition to their physical symptoms, such patients, and their doctors, are distressed and frustrated by the lack of explanation, credibility, and acceptable treatment options.8–12

Intervention studies have often focused on people with both medically unexplained symptoms and anxiety and depression (‘somatisers’), a combination that constitutes about 40% of the group overall.13,14 These studies include the work of Morriss and colleagues,15–17 who have developed and tested a ‘reattribution model’ for use by GPs, as well as evaluations of a wide range of approaches directed at the patients, including medication, patient education, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), and counselling.18–21 These approaches have been shown to be effective for some patients but to be limited by low acceptability among both GPs and patients. Other complex interventions that pragmatic trials have shown to have some benefits for people with unexplained symptoms, whether or not they have anxiety and/or depression, include exercise training,6 multidisciplinary clinics,13 and nurse practitioner clinics aimed at improving social and communication skills and rationalising medication.22 These resources are, however, rarely available.

Reviews of this complex evidence base about what people with unexplained symptoms find helpful have highlighted the importance of actively involving patients in explanations, and providing treatments that link physical and psychological problems.23–25 The present authors’ previous work, and that of others, suggests that a series of traditional acupuncture consultations constitutes a complex intervention that may have these characteristics,26,27 and may therefore provide an effective treatment option. This hypothesis is supported by evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in functional conditions that overlap with ‘unexplained symptoms’, including fibromyalgia,28,29 headache,30–32 and back pain.33–35 In designing an initial evaluation of this complex intervention, the authors considered the relative merits and limitations of a sham-acupuncture or attention-controlled design versus a pragmatic ‘black box’ trial.36 Hypotheses directed at the effect of the needling component of acupuncture consultations require sham-acupuncture controls which, while appropriate for formulaic needling for single well-defined conditions, have been shown to be problematic when dealing with multiple or complex conditions, because they interfere with the participative patient–therapist interaction on which the individualised treatment plan is developed.37–39 Pragmatic trials, on the other hand, are appropriate for testing hypotheses that are directed at the effect of the complex intervention as a whole, while providing no information about the relative effect of different components. The evidence quoted above led to the hypothesis that the whole complex intervention of traditional acupuncture consultations would be most likely to benefit this patient group and, consequently, like the investigators of other complex interventions in this area (quoted above), the authors of the present study chose a pragmatic trial design. Additionally, a nested qualitative study was included to begin to investigate the roles of the different components of the complex intervention and their relationships to contextual issues such as time — questions that would need further study if the initial trial indicated possible benefits.

How this fits in

Successful management of people with persistent medically unexplained symptoms includes actively involving them in explanations and treatments that link physical and psychological problems. These processes are integral to most traditional acupuncture treatment. The results of this trial indicate that up to 12 sessions of five-element acupuncture, a type of traditional acupuncture, improved patients’ wellbeing and individualised health status but did not change their high consultation rates over a 6-month period. A course of traditional acupuncture consultations is therefore a safe and potentially helpful referral option, although its cost-effectiveness is unknown.

This paper reports on a pragmatic randomised trial to investigate the effect of adding a type of traditional acupuncture — five-element acupuncture — to usual care. The study aimed to answer the question ‘In patients who attend frequently in primary care with MUPS that have persisted for more than 3 months, does the addition of classical five-element acupuncture to usual GP care, compared to usual care alone, improve self-reported health and reduce conventional medication and general practice consultation rates?’.

METHOD

Participants

Between March and December 2008, four general practices serving London communities that included some with considerable socioeconomic disadvantage recruited patients and hosted the acupuncture treatment (Index of Multiple Deprivation for the four practices = 41.87; 39.14; 37.18; 30.18). During their day-to-day practice, supplemented by searches of electronic records, GPs identified patients who had recently consulted and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 1).

Box 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Criteria for ‘persistent medically unexplained physical symptoms’1,40,41

The presentation of a physical symptom

The symptom had existed for at least 3 months

It had caused clinically significant distress or impairment

It could not be explained by physical disease, that is; ‘physical symptoms for which no clear or consistent organic pathology can be demonstrated’

Other inclusion criteria (from electronic record search)

Had consulted GPs (clinic, telephone or home consultations) 8 or more times in previous 12 months

Exclusion criteria

Pregnancy

Unable to attend the surgery for treatment

Insufficient English to complete the questionnaires

Additional severe physical or mental frailty

Procedure

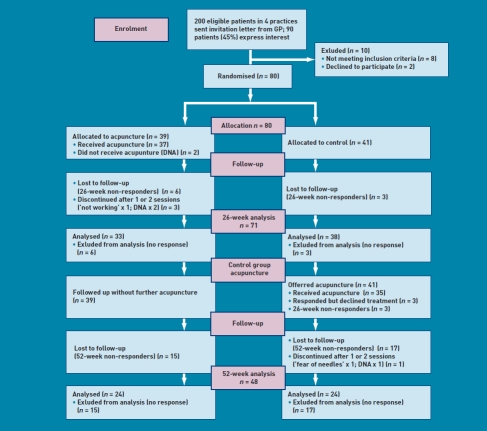

A pragmatic42 randomised trial design with a waiting list control43 was used, in order that all patients would have the opportunity to have acupuncture treatment. Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT flow chart.

Patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 1) were sent an invitation letter and information booklet; potential participants returned their contact details to the research team, who checked the inclusion criteria; and an initial recruitment interview was held at the GP surgery. At this interview, researchers obtained informed written consent and baseline data, and then randomly allocated patients. Group allocation was undertaken by the Institute of Psychiatry Clinical Trials Unit, using their web-based service. Simple randomisation was used for the first 20 patients, and then minimisation (with a random component of 80%) was applied to ensure balance across the three variables: baseline Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP) score (<4.5 versus ≥4.5); number of GP consultations in the previous 6 months (<12 versus ≥13); and age (≤50 years and >50 years). Group allocation was known by trial researchers, practitioners, and patients, but the statistician who carried out data analysis was blinded.

Intervention and control

Patients were randomised on a 1:1 basis to receive 12 sessions of acupuncture starting immediately (acupuncture group) or starting in 6 months’ time (control group), with both groups continuing to receive usual care. Individualised classical five-element acupuncture was delivered in the GP surgeries by eight five-element acupuncture practitioners who were members of the British Acupuncture Council. Twelve sessions, on average 60 minutes in length, were provided over a 6-month period at approximately weekly, then fortnightly and monthly intervals. These timings were adjusted to individual patients’ needs.

All aspects of treatment, including discussion and advice, were individualised as per normal five-element acupuncture practice. In this approach, the acupuncturist takes an in-depth account of the patient’s current symptoms and medical history, as well as general health and lifestyle issues. The patient’s condition is explained in terms of an imbalance in one of the five elements, which then causes an imbalance in the whole person. Based on this elemental diagnosis, appropriate points are used to rebalance this element and address not only the presenting conditions, but the person as a whole. Points were needled to elicit deqi (needling sensation), and moxibustion (a process using moxa, a therapeutic herb, to warm and prepare the points) was used as appropriate to the individual treatment.44,45 Treatment sheets were completed at each visit with acupuncture details as per acupuncture STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) reporting recommendations,46 including needle numbers, gauge, depth, position, and style of insertion (available from the authors). Members of the control group were offered exactly the same intervention, but delayed until after the return of their 26-week outcome questionnaires.

Outcome measures

The following self-report health questionnaires, chosen on the basis of previous acupuncture research,47 were completed with the researcher at baseline (immediately pre-randomisation), and by post at 12, 26, and 52 weeks after randomisation; non-responders were reminded by post, telephone, text, or email, according to prior consent:

the primary outcome measure was MYMOP: a brief individualised questionnaire that measures change in each of two symptoms, activity of daily living and wellbeing, with items measured on a seven-point scale, and combined to give a single MYMOP profile score.48,49 MYMOP-qual, used in this study, has an additional single open question ‘what has been most important to you?’, which has been used elsewhere to collect written qualitative data;50

the Wellbeing Questionnaire, W-BQ12, which has 12 questions within three dimensions: energy, negative wellbeing (anxiety and depression), and positive wellbeing;51

EuroQol-5D: a brief generic outcome questionnaire;52

the Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI): six questions that provide a retrospective measure of enablement; and53

the Medication Change Questionnaire, a detailed measure of medication in a weekly diary format, completed prospectively for 1 week at each time point.54

The questionnaire booklet also contained questions on demographics; healthcare resource use over the previous 3 months; and a checklist of adverse effects,55 scored with a scale of ‘bothersomeness’. The numbers of consultations with GPs (surgery, home, and telephone) were extracted from GP electronic records: for the preceding 12 months at baseline and the preceding 6 months, at 26 and 52 weeks.

A nested qualitative interview study will be reported elsewhere.56

Sample size

The study was powered on the basis of anticipated between-group differences at 26 weeks in MYMOP scores, derived from previous studies in other chronic-illness populations.48 Fifty patients would be required to detect a between-group difference in MYMOP of 1.0, assuming a common standard deviation (SD) of 1.4 to achieve 95% power at a two-tailed 5% significance level, or a between-group difference of 0.8 at 80% power allowing for a dropout of 20%. As recruitment was much slower than anticipated, the trial statistician undertook descriptive analysis of the baseline MYMOP scores for the first 40 patients recruited (not prespecified in the study protocol). Given that this analysis was aggregated across both groups, it was not subject to the bias of unblinding or the need for P-value adjustment, because of an interim comparison of groups. As descriptive analysis showed an outcome variance that was more favourable than initially planned (SD = 1.04), the total trial sample size was revised downwards to 40 participants per arm to maintain 95% power to detect the same difference of one unit. As treatments were individualised, there was no need to inflate the standard error of the treatment comparison for potential clustering.

Data analysis

Data were double entered onto a customised database. All analyses were conducted according to the principle of intention to treat (ITT), using Stata (version10). Primary analysis consisted of a between-group comparison (control versus acupuncture groups) of primary and secondary outcomes at 26 weeks. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to adjust for baseline outcome values. Regression-based analysis was used for both continuous outcomes (overall MYMOP score, overall EQ-5D index score, and overall W-BQ 12 score) and counts (primary care consultations). Given the highly skewed distribution of primary care consultations, a negative binomial model was used. Regression models were adjusted for baseline outcome values. As no between-group differences in any other patient characteristics were seen at baseline, no other patient-level covariates were added to models. Nominal and ordinal subcategory scores were compared using non-parametric c2 and Mann–Whitney tests respectively. Missing total score outcomes at 26 weeks were imputed using values at last observation brought forward, and results compared to complete case analyses. This article reports those cases where the complete case and imputed analyses give differing inferences. Results are reported as group mean differences (or equivalent), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical tests were two-sided, and deemed to be statistically significant if P≤0.05. No adjustments for multiplicity were made: because the outcome variables are interrelated, simple adjustment for the number of comparisons would be overly conservative.57 To assess if intervention effects were maintained over the longer term, a within-group analysis was conducted to compare outcome values at 52 weeks’ follow-up to baseline in the acupuncture group.

The written qualitative data were transcribed and analysed thematically by an experienced qualitative researcher.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the recruitment, randomisation, and follow-up response rates. Eighty participants were recruited, and acupuncture was started with 37 out of 39 of the acupuncture group and 35 out of 41 of the control group (after 26 weeks’ wait). Questionnaire response rates were 71 (89%) at 26 weeks; 63 (79%) at 12 weeks; and 48 (60%) at 52 weeks. Participants attended for a mean of nine (out of maximum 12) acupuncture sessions, and 32 (44%) attended all 12 sessions. At 12 weeks, 33 (85%) of those randomised to the acupuncture group were still attending for treatment. There was no difference in age, sex, baseline MYMOP score, or primary care consultation rate in the 12 months before baseline in the nine patients with missing 6-month data compared to those with full data.

Baseline characteristics

Demographic and health-problem data (Table 1) show very little difference between the groups. The study population was 80% female, with a mean age of 50 years (range 25–81 years), mixed ethnicity and social class and a range of educational backgrounds; 42% were in paid employment. The most common types of problem (categorised by International Classification of Primary Care55 from MYMOP symptom 1) were musculoskeletal, mainly chronic pain (59%); fatigue (14%); psychological/emotional problems (12%); and headache (12%).Two-thirds (65%) of participants had had their presenting complaint for over a year, and one-quarter (26%) for over 5 years. Self-reported health-resource use in the 3 months preceding randomisation was very high (Table 2), and baseline self-reported health on all questionnaires was very poor (Table 3). There was no evidence of between-group difference in baseline outcome values, except for the EQ-5D anxiety/depression subcategory and W-BQ12 negative wellbeing, where controls appeared to have poorer rating than the acupuncture group (Table 4).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Total study population, n = 80 | Acupuncture group, n = 39 | Control group, n = 41 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (range) | 51 (25–81) | 51 (29–81) | 50 (25–76) |

| Sex, female n (%) | 64 (80) | 32 (82) | 32 (78) |

| Ethnicity, white n (%) | 57 (71) | 30 (77) | 27 (66) |

| Education, % | |||

| No formal qualifications | 25 | 23 | 27 |

| School-age qualifications | 50 | 51 | 49 |

| Degree or higher qualifications | 25 | 26 | 24 |

| Social class, n (%) | |||

| 0 (never worked) | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) |

| 1 | 3 (4) | 1(3) | 2 (5) |

| 2 | 25 (31) | 15 (38) | 10 (24) |

| 3M | 8 (10) | 5 (13) | 3 (8) |

| 3N | 22 (28) | 8 (20) | 14 (34) |

| 4 | 18 (22) | 8 (20) | 10 (24) |

| 5 | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Duration of complaint, n (%) | |||

| 4–12 weeks | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| 3 months to 1 year | 13 (16) | 6 (15) | 7 (17) |

| 1–5 years | 39 (49) | 15 (38) | 24 (59) |

| Over 5 years | 26 (33) | 17 (46) | 9 (22) |

| Type of problema | |||

| Musculoskeletal | 47 (60) | 20 (51) | 27 (66) |

| Psychological/emotional | 10 (12.5) | 5 (13) | 5 (12) |

| Headache and neurological | 10 (12.5) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) |

| Fatigue | 5 (6) | 4 (10) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 7 (9) | 6 (16) | 2 (5) |

Categorised by International Classification of Primary Care58 from MYMOP symptom 1.

Table 2.

Self-reported baseline secondary care use, during the 3 months prior to recruitmenta

| Total number of days/visits | Number of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| NHS hospital inpatient days | 21 | 6 |

| NHS hospital outpatient clinic visits (‘to see a doctor’) | 106 | 41 |

| NHS hospital clinic visits with professions allied to medicine (for example, physiotherapy, chiropody, audiology, counselling) | 52 | 13 |

| NHS hospital visits for investigations (including 10 MRI scans) | 44 | 31 |

| Non-NHS total visits (complementary therapies, optician, dentist) | 75 | 16 |

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

55 of 80 participants (69%) had accessed secondary care.

Table 3.

Changes in outcomes from baseline to 26 weeks in acupuncture and control groups

| Acupuncture group |

Control group |

Between-group difference at 26 weeks |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, mean (SD), n = 39 | 26 weeks, mean (SD), n = 33 | Within group change, mean (95% CI) | Baseline, mean (SD), n = 41 | 26 weeks, mean (SD), n = 38 | Within group change, mean (95% CI) | Unadjusted mean (95% CI) | Adjusted for baseline scorea, mean (95% CI), Pvalue | |

| MYMOP | 4.3 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.3), n = 33 | −1.0 (−0.4 to −1.5) | 4.6 (0.9) | 4.0 (1.2), n = 38 | −0.6 (−0.3 to −0.9) | −0.8 (−1.4 to −0.2) | −0.6 (0 to −1.1), P = 0.05 |

| Adjusted for missing data | 3.5 (1.3), n = 33b | 4.0 (1.2), n = 41b | −0.4 (−0.9 to 0.1), P = 0.12 | |||||

| EQ-5D index | 0.47 (0.33) | 0.53 (0.33), n = 32 | 0.06 (−0.04 to 0.16) | 0.42 (0.35) | 0.47 (0.37), n = 32 | 0.05 (−0.06 to 0.16) | 0.06 (−0.11 to 0.24) | 0.03 (−0.11 to 0.16), P = 0.70 |

| Adjusted for missing data | 0.52 (0.32), n = 39b | 0.46 (0.35), n = 41b | 0.02 (−0.13 to 0.08), P = 0.66 | |||||

| W-BQ12 | 15.6 (6.8) | 20.3 (7.0), n = 32 | 4.3 (2.1 to 6.5) | 15.3 (7.1) | 15.4 (8.4), n = 36 | 0.0 (−1.9 to 1.8) | 4.8 (1.1 to 8.6) | 4.4 (1.6 to 7.2), P = 0.002 |

| Adjusted for missing data | 18.5 (7.7), n = 39b | 14.8 (8.4), n = 41b | 3.4 (0.5 to 6.3), P = 0.02b | |||||

| Totalc, n = 39, rate/year | Totald, n = 39, rate/year | Within-group rate ratio (95% CI) | Totalc, n = 41, rate/year | Totald, n = 40, rate/year | Within-group rate ratio (95% CI) | Unadjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusteda, rate ratio (95% CI) | |

| Consultations | 653, 16.7 | 258, 13.2 | 0.79 [0.67 to 0.93] | 615, 15.4 | 233, 11.9 | 0.76 [0.64 to 0.90] | 1.13, (0.84 to 1.53) | 0.90, (0.70 to 1.15), P = 0.40 |

SD = standard deviation.

Adjusted for baseline score differences.

Imputed values (baseline value carried forward): adjustment formissing data.

Over previous 12 months.

Over previous 6 months.

Table 4.

Outcome measure subscale scores at baseline and 26 weeks

| Acupuncture group |

Control group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale or subscale | Baseline, n = 39 | 26 weeks, n = 33 | Baseline, n = 41 | 26 weeks, n = 38 |

| MYMOP, median (IQR) | ||||

| Symptom 1 | 5 (4–6) | 4 (2–5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (3.25–5) |

| Symptom 2 | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) | 5 (3.75–6) | 4 (3–5) |

| Activity | 5 (4–6) | 3.5 (2–5) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (3–5) |

| Wellbeing | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–5) |

| W-BQ12, mean (SD) | ||||

| Negative W-B | 5.0 (3.5) | 3 (2.9) | 6.2 (2.8) | 5.4 (3.5) |

| Energy | 8.6 (2.5) | 6.9 (2.8) | 8.2 (2.6) | 8.2 (2.7) |

| Positive W-B | 5.3 (2.8) | 5.8 (2.7) | 5.8 (3.2) | 5.3 (3.5) |

| EQ-5D index | ||||

| Mobility, n (%) | ||||

| No problems in walking about | 13 (33) | 14 (42) | 17 (41) | 16 (44) |

| Some problems in walking about | 26 (67 | 18 (55) | 24 (59) | 20 (56) |

| Confined to bed | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Self-care, n (%) | ||||

| No problems with self-care | 27 (69) | 24 (73) | 33 (80) | 26 (76) |

| Some problems washing or dressing | 11 (28) | 8 (24) | 8 (20) | 8 (24) |

| Unable to wash or dress | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Usual activities, n (%) | ||||

| No problems | 11 (28) | 13 (39) | 11 (27) | 7 (20) |

| Some problems | 26 (67) | 18 (55) | 28 (68) | 26 (74) |

| Unable to perform | 2 (5) | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Pain/discomfort, n (%) | ||||

| No pain or discomfort | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) |

| Moderate pain or discomfort | 25 (64) | 23 (72) | 27 (66) | 22 (61) |

| Extreme pain or discomfort | 11 (28) | 7 (22) | 12 (29) | 11 (31) |

| Anxiety/depression, n (%) | ||||

| Not anxious or depressed | 12 (31) | 12 (36) | 8 (20) | 10 (28) |

| Moderately anxious or depressed | 24 (61) | 10 (31) | 26 (63) | 17 (47) |

| Extremely anxious or depressed | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 10 (18) | 9 (25) |

IQR = interquartile range. SD = standard deviation.

Main quantitative findings

26 weeks’ follow-up

The change in outcomes from baseline to 26 weeks in the acupuncture and control groups, with and without imputation for missing data, is shown in Table 3. The PEI is omitted because it did not perform well as a repeated measure (many control group patients checked ‘not applicable’ because they thought the questions related only to acupuncture treatment).

After 6 months, the group receiving acupuncture improved their MYMOP profile score by 1.0 (95% CI = 0.4 to 1.5) compared to the control group, who improved by 0.6 (95% CI = 0.3 to 0.9). After adjustment for baseline differences, the adjusted mean difference between the groups in favour of acupuncture was 0.6 (95% CI = 0 to 1.1), P = 0.05. However, when missing values were imputed, the groups were no longer significantly different: 0.4 (95% CI = –0.1 to –0.9), P = 0.12. An adjusted mean difference, in favour of acupuncture, was seen with wellbeing (W-BQ12): 4.4 (95% CI = 1.6 to 7.2), P = 0.002 and this remained significant after missing values were imputed: 3.4 (95% CI = 0.5 to 6.3), P = 0.02. The difference appears most marked in the negative wellbeing (anxiety and depression) subscale (Table 4).

In both groups, the EuroQol-5D scores improved and GP consultation rates and medication reduced, with no significant difference between the groups. The adjusted difference between the groups was: EuroQol-5D 0.03 (95% CI = –0.11 to 0.16), P = 0.40; consultation rate/year 0.90 (95% CI = 0.70 to 1.15), P = 0.70; current number of medications 0.56 (95% CI = 0.47 to 1.6), P = 0.28. The EuroQol anxiety and depression dimension showed the largest improvement (Table 4).

52 weeks’ follow-up

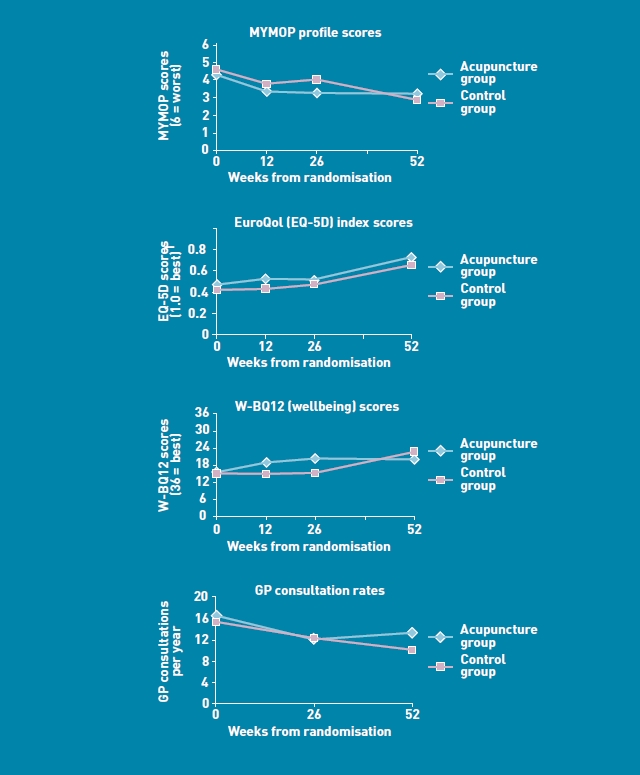

At 52 weeks (Figure 2, Table 5), the improvements in the members of the acupuncture group who had finished their acupuncture at 6 months were maintained. Adjusted mean differences within the acupuncture group (baseline to 52 weeks) were: MYMOP 0.8 (95% CI = 0.2 to 1.4), P = 0.017; wellbeing (W-BQ12) 3.8 (95% CI = 1.5 to 6.1), P = 0.022; EQ-5D index 0.13 (95% CI = 0.02 to 0.24), P = 0.03. The control group, who had now also received 6 months of acupuncture, appeared to show a ‘catch up’ improvement in all outcome measures.

Figure 2.

Outcome data over 52 weeks (acupuncture group received acupuncture weeks 0–26, control group received acupuncture weeks 26–52).

Table 5.

Outcome measures mean (SD) scores at all time points 5 (these values are shown graphically in Figure 2)

| Acupuncture group (received acupuncture between 0 and 26 weeks) |

Control group (received acupuncture between 26 and 52 weeks) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, n = 39 | 12 weeks, n = 29 | 26 weeks, n = 33 | 52 weeks, n = 24 | Baseline, n = 41 | 12 weeks, n = 34 | 26 weeks, n = 38 | 52 weeks, n = 24 | |

| MYMOPa | 4.3 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.5) | 4.6 (0.9) | 3.8 (1.6) | 4.0 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.4 |

| EQ-5Db Index | 0.47 (0.33) | 0.53 (0.28), n = 23 | 0.53 (0.33) | 0.73 (0.10) | 0.42 (0.35) | 0.43 (0.37), n = 31 | 0.47 (0.37) | 0.66 (0.27) |

| W-BQ12b | 15.6 (6.8) | 19.1 (6.6), n = 28 | 20.3 (7.0) | 20.0 (5.9) | 15.3 (7.1) | 15.8 (8.0), n = 31 | 15.4 (8.4) | 20 (5.9) |

| GP consultation rate/year | 16.7 | Not collected | 13.2 | 13.5 | 15.4 | Not collected | 11.9 | 10.1 |

Higher score = worse health.

Higher score = better health.

Adverse events

Six hundred and ninety-two treatment sessions were delivered and no serious adverse events were reported. Of the 74 participants who responded to the question at one time point or more, 37 (50%) reported one or more bothersome responses to treatment, and the degree of bother was ‘a bit’ for 21; ‘quite a lot’ for 13; and ‘a great deal’ for 3. All three responses that were scored as ‘a great deal’ bothersome were in the category of ‘a temporary worsening of symptoms’, and other responses comprised ‘tiredness or drowsiness’, ‘dizziness or light-headedness’, ‘pain or tingling of the needling’, and ‘feeling more emotional’.

Written qualitative data

At the end of their 6 months of acupuncture, the optional open question on MYMOP-qual ‘What has been most important to you?’ was answered by 82% of the acupuncture group at 26 weeks and 80% of the control group at 52 weeks. The most common theme was ‘rapport with practitioner’, which included talking to a friendly/empathic practitioner who listened, understood, provided explanations, and sometimes gave advice and ‘treated me as a whole’. The responses also included treatment effects such as generally ‘feeling better’, increased relaxation, sleep, and energy, and symptom improvement. The few negative comments constituted a lack of symptom improvement, temporary improvement, or a recurrence of symptoms on stopping acupuncture. Other responses related to improved self-awareness, self-confidence and self-help, such as ‘a greater awareness of my own needs’ and ‘able to slow down my thought process to help me think things through’, which were linked to making ‘important changes in my personal life’ or starting ‘working on a temporary basis’.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Study participants had long-term unexplained symptoms, poor self-reported health, and high healthcare resource use, and came from a wide range of socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. The addition of up to 12 five-element acupuncture consultations to their usual care was feasible and acceptable (few dropouts and high uptake of sessions), and resulted in improved wellbeing and individualised health status (MYMOP) that was sustained up to 12 months. The statistical significance of the improvement in MYMOP score was sensitive to the imputation of missing case data. However, the method of data imputation employed biased against the intervention, as it involved carrying forward baseline values, and therefore assuming no improvement from baseline to 6 months in those individuals with missing follow-up data in either the acupuncture or control groups. There was no evidence that the very high GP consultation rates or their medication use decreased during the 6 months of treatment.

Strengths and limitations

The ‘black box’ study design precludes assigning the benefits of this complex intervention to any one component of the acupuncture consultations, such as the needling or the amount of time spent with a healthcare professional. In addition, the waiting list design brings limitations to the analysis because it does not allow a between-group analysis beyond the 26 weeks. This design was chosen because, without a promise of accessing the acupuncture treatment, major practical and ethical problems with recruitment and retention of participants were anticipated. This is because these patients have very poor self-reported health (Table 3), have not been helped by conventional treatment, and are particularly desperate for alternative treatment options. However, within these limitations, the authors believe the randomised design provides robust evidence, and a 26-week questionnaire response rate of 89% was achieved. The within-group analysis does suggest that the treatment effect is sustained in the acupuncture group for 6 months after the end of treatment. The sustained nature of the change militates against it being purely a function of a good relationship and attention to the whole person, although the written qualitative data indicate that both these aspects were important.

Comparison with existing literature

This is the first trial of acupuncture for people with unexplained symptoms. However, the study population included patient groups for whom acupuncture has previously been shown to be cost-effective, including those with headache30–32 and back pain,33–35 and so adds to the evidence base in this area. The written qualitative data also confirm previous reviews23,24 concerning the value of participation and its link to self-efficacy — themes that are also evident in the interview data to be reported elsewhere.56 The lack of serious adverse effects in this study is in accordance with data from large-scale surveys of acupuncture, which demonstrate its safety.55,59

Implications for research and practice

This study has begun the process of developing an evidence base for traditional acupuncture as an additional treatment option for these ‘difficult-to-help’ patients, and also provides generalisable data on outcomes and baseline resource use on which to base a longer term cost-effectiveness trial. In view of the complexity, severity, and chronicity of the health problems presented, and the high take-up of 12 treatment sessions, the addition of ‘maintenance’ monthly acupuncture treatments beyond 6 months is likely to increase effectiveness, self-efficacy, and self-care. In keeping with the reviews of successful management of this condition,23–25 this study has found that an individualised approach that is based on an explanatory theory that links physical and psychological problems appears effective. While further studies are required to understand the detailed contributions of the ‘black box’ of traditional acupuncture consultations, GPs may recommend five-element acupuncture to these patients, as a safe and potentially effective intervention.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to other members of the CACTUS study group: Mary Coales, Helen Gardner-Thorpe, Peter Harvey, David Misselbrook, and Jennifer Record. Nicky Britten was partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Thanks also to the practices and patients who participated, to the acupuncture practitioners, and to Laura Stabb for the database. Many thanks to the reviewers for their detailed comments.

Funding body

We thank the King’s Fund for funding the project.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN99754128

Ethics committee

Ethical approval was given by Lewisham LREC (07/H0810/54).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Peveler R, Kilkenny L, Kinmonth AL. Medically unexplained physical symptoms in primary care: a comparison of self-report screening questionnaires and clinical opinion. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmon P, Dowrick C, Ring A, Humphris GM. Voiced but unheard agendas: qualitative analysis of the psychosocial cues that patients with unexplained symptoms present to general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(500):171–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speckens AEM, van Hemert AM, Spinhoven P, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for medically unexplained physical symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1995;311(7016):1328–1332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7016.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, Hotopf M. Frequent attenders with medically unexplained symptoms: service use and costs in secondary care. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:248–253. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart P, O’Dowd T. Clinically inexplicable frequent attenders in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(485):1000–1001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters S, Stanley I, Rose M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of group aerobic exercise in primary care patients with persistent, unexplained physical symptoms. Fam Pract. 2002;19(6):665–674. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woivalin T, Krantz G, Mantyranta T, Ringsberg KC. Medically unexplained symptoms: perceptions of physicians in primary health care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(2):199–203. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nettleton S, Watt I, O’Malley L, Duffey P. Understanding the narratives of people who live with medically unexplained illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werner A, Malterud K. It is hard work behaving as a credible patient: encounters between women with chronic pain and their doctors. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(8):1409–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salmon P, Peters S, Stanley I. Patients’ perceptions of medical explanations for somatisation disorders: qualitative analysis. BMJ. 1999;318(7180):372–376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7180.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ring A, Dowrick C, Humphris GM, Salmon P. Do patients with unexplained physical symptoms pressurise general practitioners for somatic treatment? A qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7447):1057–1063. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38057.622639.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zantinge EM, Verhaak PFM, Kerssens JJ, Bensing JM. The workload of GPs: consultations of patients with psychological and somatic problems compared. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(517):609–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matalon A, Nahmani T, Rabin S, et al. A short-term intervention in a multidisciplinary referral clinic for primary care frequent attenders: description of the model, patient characteristics and their use of medical resources. Fam Pract. 2002;19(3):251–256. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dirkzwager AJE, Verhaak PFM. Patients with persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: characteristics and quality of care. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morriss R, Gask L, Ronalds C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a new treatment for somatized mental disorder taught to GPs. Fam Pract. 1998;15(2):119–125. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morriss RK, Gask L, Ronalds C, et al. Clinical and patient satisfaction outcomes of a new treatment for somatized mental disorder taught to general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(441):263–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morriss R, Dowrick C, Salmon P, et al. Turning theory into practice: rationale, feasibility and external validity of an exploratory randomized controlled trial of training family practitioners in reattribution to manage patients with medically unexplained symptoms (the MUST) Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(4):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Swindle R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization and symptom syndromes: a critical review of controlled clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(4):205–215. doi: 10.1159/000012395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold IA, Speckens AEM, van Hemert AM. Medically unexplained physical symptoms. The feasibility of group cognitive-behavioural therapy in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(6):517–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.04.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsky AJ, Ahern DK. Cognitive Behavior therapy for hypochondriasis. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(12):1464–1470. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.12.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):980–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):671–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet. 2007;369(9565):946–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatcher S, Arroll B. Assessment and management of medically unexplained symptoms. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1124–1128. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39554.592014.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowrick C, Katona C, Peveler R, Lloyd H. Somatic symptoms and depression: diagnostic confusion and clinical neglect. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(520):829–830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterson C, Britten N. The patients experience of holistic care: insights from acupuncture research. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(4):264–277. doi: 10.1177/1742395308100648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cassidy C. Chinese medicine users in the United States. Part II: preferred aspects of care. J Altern Complement Med. 1998;4(2):189–202. doi: 10.1089/acm.1998.4.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holdcraft LC, Assefi N, Buchwald D. Complementary and alternative medicine in fibromyalgia and related syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17(4):667–683. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2388–2395. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wonderling D, Vickers AJ, Grieve R, McCarney R. Cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised trial of acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care. BMJ. 2004;328(7442):747. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38033.896505.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickers AJ, Rees RW, Zollman CE, et al. Acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care: large, pragmatic, randomised trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7442):744–747. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38029.421863.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD007587. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Ratcliffe J, et al. Longer term clinical and economic benefits of offering acupuncture care to patients with chronic low back pain. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(32):iii–iv. ix–x, 1–109. doi: 10.3310/hta9320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manheimer E, White A, Berman BM, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):651–663. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Low back pain. early management of persistent non-specific low back pain. NICE clinical guideline 88. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2009. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mason S, Tovey P, Long AF. Evaluating complementary medicine: methodological challenges of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2002;325(7368):832–834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7368.832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paterson C, Dieppe P. Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture. BMJ. 2005;330(7501):1202–1205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7501.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McManus CA, Kaptchuk TJ, Schnyer RN, et al. Experiences of acupuncturists in a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(5):533–538. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.6309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paterson C, Zheng Z, Xue C, Wang Y. ‘Playing their parts’: the experiences of participants in a randomized sham-controlled acupuncture trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(2):199–208. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dowrick C, Ring A, Humphris GM, Salmon P. Normalisation of unexplained symptoms by general practitioners: a functional typology. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(500):165–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burton C. Beyond somatisation: a review of the understanding and treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(488):233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roland M, Torgerson DJ. What are pragmatic trials? BMJ. 1998;316(7127):285–286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7127.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Worsley JR. Florida: The Worsley Institute of Classical Acupuncture; 1998. Classical five-element acupuncture volume III — the five elements and the officials. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hicks A, Hicks J, Mole P. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. Five element constitutional acupuncture. [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacPherson H, White A, Cummings M, et al. Standards for reporting interventions in controlled trials of acupuncture: the STRICTA recommendations. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9(4):246–249. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson C. Patient-centred outcome measurement. In: MacPherson H, Hammerschlag R, Lewith G, Schnyer RN, editors. Acupuncture research: strategies for establishing an Evidence Base. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2007. pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paterson C. Measuring outcome in primary care: a patient-generated measure, MYMOP, compared to the SF-36 health survey. BMJ. 1996;312(7037):1016–1020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paterson C, Britten N. In pursuit of patient-centred outcomes: a qualitative evaluation of the ‘Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile’. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2000;5(1):27–36. doi: 10.1177/135581960000500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polley M, Seers H, Cooke H, et al. How to summarise and report written qualitative data from patients: a method for use in cancer support care. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(8):963–971. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradley C. The 12-item Well-being Questionnaire. Origins, current stage of development, and availability. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(6):875. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The EuroQol group. EuroQol — a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howie JGR, Heaney DJ, Maxwell M, Walker JJ. A comparison of the Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI) against two established satisfaction scales as an outcome measure of primary care consultations. Fam Pract. 1998;15(2):165–171. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paterson C, Symons L, Britten N, Bargh J. Developing the Medication Change Questionnaire. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2004;29(4):339–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacPherson H, Scullion A, Thomas KJ, Walters S. Patient reports of adverse events associated with acupuncture treatment: a prospective national survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(5):349–355. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.009134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rugg S, Paterson C, Britten N, et al. Traditional acupuncture for people with medically unexplained symptoms: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ experiences. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X577972. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp11X577972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown B, Russell K. Methods correcting for multiple testing: operating characteristics. Stat Med. 1997;16(22):2511–2528. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971130)16:22<2511::aid-sim693>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.WONCA International Classification Committee. International classification of primary care. ICPC-2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 59.White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, Ernst E. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001;323(7311):485–486. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]