Abstract

This study evaluated biodegradation of the insecticide deltamethrin (1 μg l−1) by pure cultures of neustonic (n = 25) and epiphytic (n = 25) bacteria and by mixed cultures (n = 1), which consisted of a mixture of 25 bacterial strains isolated from the surface microlayer (SM ≈ 250 μm) and epidermis of the Common Reed (Phragmites australis, (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud.) growing in the littoral zone of eutrophic lake Chełmżyńskie. Results indicate that neustonic and epiphytic bacteria are characterized by a similar average capacity to degrade deltamethrin. After a 15-day incubation, bacteria isolated from the surface microlayer reduced the initial concentration of deltamethrin by 60%, while the average effectiveness of the bacteria found on the Common Reed equaled 47%.

Keywords: Biodegradation, Deltamethrin, Epiphytic bacteria, Neustonic bacteria, Lake, Pesticides

Introduction

Pesticides are pollutants that commonly occur in surface waters. They have been found in drinking water, underground water, troposphere, or even in water and ice of the Polar Regions. Organic phosphate compounds, carbamates, and pyrethroids are the most common pesticides used in agriculture.

A layer separating the atmosphere from the water, called the surface microlayer is a specific type of environment, differing clearly from subsurface water both in physical properties and in the chemical and biological composition. Organisms like bacteria, algae and small animals living there are called neuston. This layer contains naturally occurring organic compounds, such as: lipids, proteins, and polysaccharides (Hardy 1982; Garabetian et al. 1993). Because of the high concentration of organic substances occurring in the microlayer, both autotrophic and heterotrophic bacteria find optimal conditions for growth there. Sedimentation and fallout of various aerosols, including pesticides, dust and gases occurring in the atmosphere, play an important role increasing the concentration of chemical substances in the surface microlayer (Norkrans 1980). Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) of anthropogenic origin, such as: pesticides, polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), or polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs) tend to hyperaccumulate in that zone (Wurl and Obbard 2005; Manadori et al. 2006).

Epiphytic bacteria grow on aquatic macrophytes with their greatest numbers occurring in littoral zones of water bodies; this zone is particularly affected by pesticides due to the proximity of farmland. It was demonstrated that only 1-3% of the applied dose of pesticide reaches its target (Plimmer 1990). The majority of the applied compound is wasted and reaches surface waters through runoff.

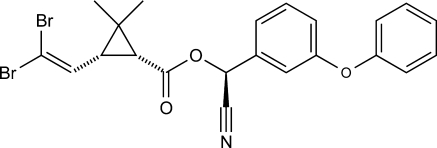

Deltamethrin (Fig. 1) is a pyrethroid insecticide used widely in agriculture, including vegetable, fruit, and ornamental plant farming, and in forestry to control gnawing and sucking pest. It is a contact and systemic neurotoxin that strongly affects neurotransmitters in the central and peripheral nervous system (Narahashi 1996). Deltamethrin is characterized by advanced toxic properties, which means that it can be used in very small doses in comparison to the previously used active substances. Concentrations of this insecticide found in surface waters range from 0.04 to 24.0 μg l−1 (Pawlish et al. 1998). The half-life of deltamethrin in water ranges from 2 to 4 h. In laboratory condition, this substance shows high toxicity to fish, aquatic arthropods, and bees (Różański 1992). In the aquatic environment, pyrethroids undergo spontaneous hydrolysis, particularly in the environment with high pH (Sogorb and Vilanova 2002) and are subject to enzymatic degradation by enzymes produced by microorganisms (Demoute 2006).

Fig. 1.

Deltamethrin—structural formula

Decomposition of pesticides by microorganisms is an essential process in affecting the fate of these pollutants in the environment, finding applications in bioremediation (Gianfreda and Rao 2004). Microorganisms are highly effective in transforming organic pollutants and modifying their structure and toxic properties; furthermore, they can completely mineralize organic compounds to non-organic products (Zipper et al. 1996).

Due to the fact that the research on pesticide biodegradation has been largely limited to the soil environment, our knowledge about capability of aquatic bacteria to break down these xenobiotics is still minimal. The purpose of this study is to determine whether any of the neustonic or epiphytic bacteria inhabiting the described environments are capable of decomposing deltamethrin and which ecological group, genus, and species of bacteria is the most effective in advancing this process.

Experimental methods

Isolation of strains

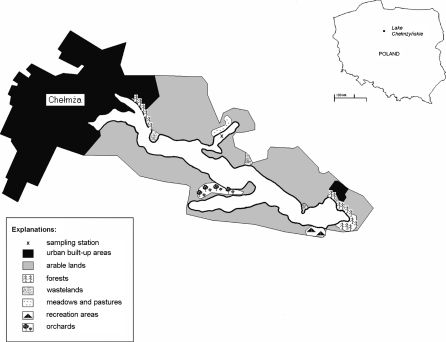

The analyzed strains of bacteria were isolated from the samples of epidermis of the Common Reed (Phragmites australis, (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud.) and surface microlayer (≈250 μm), which were collected in the extra-urban section of lake Chełmżyńskie surrounded by farmland (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Outlook of lake Chełmżyńskie

Lake Chełmżyńskie is located in central Poland (central Europe), ca. 20 km from Toruń, belongs to the Fryba-Vistula river basin, and is a typical eutrophic water body. The watershed of the lake primarily includes arable lands, which constitutes 72% of the immediate watershed. The urbanized areas of Chełmża are located in the northwestern section of the lake.

A sample of epidermis was collected with a sterile scalpel. Samples of surface microlayer were collected with a nylon Garret net with a pore diameter of 65μm and an active surface of 50 × 50 cm, which allowed us to collect 250 ± 50 μm thick samples (Garret 1965). The nylon net was rinsed with ethyl alcohol and sterile distilled water prior to sampling.

The samples of water (n = 1) and epidermis (n = 1) were placed in sterile glass jars and transported to a laboratory in a cold container at a temperature below +4°C. The time between the sample collection and the beginning of the microbiological analyses did not exceed 4 h.

Ten grams of epidermis of the Common Reed was placed in 90 ml of a sterile buffer (Daubner 1967) and was homogenized (Unipan 329) for 2 min at 4,000 rpm.

Both the homogenate of the Common Reed epidermis and a sample of surface microlayer were diluted with sterile buffer water according to Daubner (1967), inoculated on peptone-iron agar (IPA), according to Ferrer et al. (1963), and incubated at 20°C in order to isolate bacterial colonies for further analyses. Twenty-five bacterial strains were randomly isolated from the sample of the Common Reed epidermis and 25 strains were isolated from surface water microlayer.

Effect on deltamethrin on bacterial growth

Bacterial strains isolated from individual samples (streake plate method) and cultured on peptone-iron agar slants (IPA) were tested for purity (colony morphology, Gram staining, and cell morphology) and then used for preparation of preliminary cultures. Subsequently, bacterial inoculum for the analyses of deltamethrin degradation was obtained from these preliminary cultures. Five ml of sterile mineral medium, containing (g l−1 of distilled water) KH2PO4—1, KNO3—0.5, MgSO4 7H2O—0.4, CaCl2—0.2, NaCl—0.1, FeCl3—0.1, glucose—1, was poured into test tubes, inoculated with pure bacterial cultures, and incubated at 20°C for 168 h in a rotary shaker (WL—2000, JW Electronic). Bacterial inoculum was retrieved from the culture with 2 inoculation loops. The medium contained deltamethrin (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, purity of deltamethrin 99.8%) with the final concentration of 1 μg l−1. For each bacterial strain, we also carried out control analyses, which involved culturing bacteria on a mineral medium without the pesticide.

In order to prepare the inoculum, the preliminary cultures were brought to identical optical density A = 0.2 ± 0.05. The spectrophotometric measurements of the culture absorbance was conducted with a spectrophotometer “Marcel s 330 Pro” at a wavelength of λ = 560 nm.

In addition to bacterial inocula containing pure bacterial cultures, mixed bacterial cultures, containing 25 strains of pure strains, were prepared for each of the analyzed ecological groups of lacustrine microorganisms. The cultures were brought to the appropriate optical density with the same method as the pure cultures.

In order to determine the adaptability of the microorganisms to growth in the presence of the xenobiotic, we measured the optical density of preliminary cultures in a medium with and without deltamethrin after 168 h of incubation in accordance with the above method.

Screening for the biodegradation of deltamethrin

Hundred micro liter samples of bacterial inocula were poured into Erlenmeyer flasks containing 75 ml of sterile mineral medium with the above composition. The final concentration of deltamethrin in cultures equaled 1 μg l−1. Sterile mineral medium without pesticide was used to dilute the samples. All samples were analyzed in triplicates. Simultaneously, control analyses were conducted for each bacterial strain. These analyses involved culturing bacteria in 75 ml of mineral medium without the addition of the xenobiotic. There were also controls for abiotic degradation of deltamethrin (75 ml of sterile medium plus insecticide).

Bacterial cultures and controls for abiotic degradation were incubated for 15 days at 20°C in the dark in the rotary shaker (WL—2000, JW Electronic). Purity of the bacterial cultures were tested after 5, 10, and 15-day incubation.

Degradation of deltamethrin was monitored with a gas chromatography (GC). The analyses were conducted with a Shimazu GC set with ECD detector. In order to determine the concentration of the pesticide, 2 ml samples of cultures were collected after 5, 10, and 15-day incubation. Then samples were extracted three times with 2-ml portions of hexane (POCH). Before the extraction step 50 μl of the internal standard (decachlorobiphenyl, Sigma-Aldrich) in acetone (10 μg l−1) was added to each sample. The extracts were combined and evaporated under a gentle stream of ultra pure nitrogen at ambient temperature. The remains after evaporating were dissolved in 50 μl of methanol (POCH). The obtained extracts were stored at −4°C in glass vials for later analysis by gas chromatography.

The chromatographic analyses were conducted with a capillary column: Equity-5 (Perkin Elmer) 30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 mm d.f. The size of analyzed samples equaled 5 μl. the carrier gas was N2; the rate of flow was 60 ml min−1. The temperature program was as following: 150°C (1 min), 35°C min−1–200°C, 15°C min−1–280°C. Detector’s temperature was 320°C, injector’s temperature 260°C. The calibration curve was prepared using decachlorobiphenyl (Sigma-Aldrich, purity of decachlorobiphenyl 99.0%) as the internal standard. All plots were linear with a correlation coefficient of 0.99 or higher (least squared method).

The level of deltamethrin biodegradation [%] was calculated from the equation:

|

where, B is the biodegradation [%], a is the concentration of deltamethrin in a culture after t 0, b is the concentration of deltamethrin in a culture after t 5, 10, 15.

Identification of strains

Strains of bacteria which were the most efficient in reducing the concentration of deltamethrin were identified with the analytical profile index (API 20NE, API 50CH, API 20E, API Staph, API Strep test kit, BioMeriéux). Tests were conducted in three replicates as recommended by the manufacturing company.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in STATISTICA 6.0, 2001. In order to determine the statistically significant differences in ability of the analyzed bacteria to break down deltamethrin after 5, 10, and 15 days of incubation t-test was used.

Results and discussion

Deltamethrin is among those pyrethroid insecticides that are decomposed in the natural environment relatively easily as a result of photodegradation and biodegradation; the latter is thought to be the primary process responsible for decomposition of this compound in waters with alkaline or neutral pH and limited amount of light. The principal mode of pyrethroid decomposition includes hydrolysis of ester bonds and oxidation of acid and alcohol functional groups (Demoute 2006).

Table 1 presents basic descriptive statistics that characterize the optical density in epiphytic and neustonic bacterial cultures on medium with and without deltamethrin. According to these results culture optical density on medium with deltamethrin in neustonic and epiphytic cultures equalled adequately 0.338 and 0.280 and without deltamethrin 0.318 (epiphytic) and 0.185 (neustonic). In that case we can affirm that the development of both ecological groups of lacustrine bacteria was not hindered by the presence of deltamethrin. No significant differences between absorbance in cultures with (Ad) and without (A0) deltamethrin were found during the first 168 h of incubation. Optical density of epiphytic bacterial cultures containing deltamethrin was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of cultures without this xenobiotic. Thus, the 1μg l−1 concentration of deltamethrin was found to have a stimulating effect on the majority of bacterial strains. Zhang et al. (1984) observed an increase in bacterial and actinomycete populations in soil containing deltamethrin during a 180-day experiment on degradation of deltamethrin in organic soil. However, certain organic micropollutants may be toxic to populations of microorganisms, inhibiting their metabolism; as a result, degradation of these compounds is possible only to a small degree (Warren et al. 2003).

Table 1.

Culture optical density in the medium with (Ad) and without (A0) deltamethrin

| Group of bacteria | Statistics | Ad | A0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| t 168 | |||

| Neustonic | Averagea | 0.338 | 0.318 |

| SD | 0.181 | 0.160 | |

| Epiphytic | Average | 0.280 | 0.185 |

| SD | 0.132 | 0.092 | |

aAverage (N = 26)

SD standard deviation

In order to confirm the priority of biodegradation over abiotic modes of transformation in decomposing pyrethroids, Chapman et al. (1981) investigated stability of permethrin, cypermethrin, deltamethrin, fenpropathrin, and fenvelaret in sterile and non-sterile soil samples. The initial concentration of pesticides equaled 1 ppm. The remaining percentages of pesticides after 8-week incubation were as follows: fenpropathrin—2%, permethrin—6%, cypermethrin—4%, fenvelaret—12%, and deltamethrin—52%. In sterile soil samples, the content of pesticides exceeded 90%, which suggests that biodegradation plays a key role in decomposing these compounds in soil. In biodegradation tests with deltamethrin as the only source of carbon and energy conducted on bacterial inoculants isolated from soils and, between 35.7 and 44.4% of the initial concentration of insecticide was broken down within a week, and between 59.7 and 72.5% within two weeks. In samples without microorganisms, the initial concentration of this compound was reduced by 3–10% (Khan et al. 1988).

Table 2 presents data on reduction of deltamethrin concentration in pure and mixed cultures of epiphytic and neustonic bacteria. According to these results, discrepancies in rates of concentration reduction by different ecological groups of lacustrine microorganisms were not significant (Table 3). Neustonic and epiphytic bacteria decomposed the analyzed xenobiotic with similar rates.

Table 2.

Biodegradation of deltamethrin in pure and mixed cultures of neustonic and epiphytic bacteria

| No. | Neustonic bacteria | Epiphytic bacteria | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (ng/l) | Biodegradation (%) | Concentration (ng/l) | Biodegradation (%) | |||||||||

| t 5 | t 10 | t 15 | t 5 | t 10 | t 15 | t 5 | t 10 | t 15 | t 5 | t 10 | t 15 | |

| 1 | 1,004 | 1,002 | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 734 | 372 | 362 | 27 | 63 | 64 |

| 2 | 289 | 271 | 259 | 71 | 73 | 74 | 872 | 502 | 894 | 13 | 50 | 11 |

| 3 | 1,005 | 909 | 460 | 0 | 9 | 54 | 340 | 239 | 204 | 66 | 76 | 80 |

| 4 | 1,002 | 659 | 461 | 0 | 34 | 54 | 1,001 | 899 | 409 | 0 | 10 | 59 |

| 5 | 926 | 517 | 386 | 7 | 48 | 61 | 286 | 261 | 192 | 71 | 74 | 81 |

| 6 | 1,002 | 784 | 712 | 0 | 22 | 29 | 111 | 103 | 99 | 89 | 90 | 90 |

| 7 | 407 | 256 | 212 | 59 | 74 | 79 | 931 | 606 | 345 | 7 | 39 | 66 |

| 8 | 980 | 725 | 330 | 2 | 27 | 67 | 1,000 | 805 | 517 | 0 | 19 | 48 |

| 9 | 1,004 | 901 | 570 | 0 | 10 | 43 | 813 | 268 | 244 | 19 | 73 | 76 |

| 10 | 1,008 | 808 | 515 | 0 | 19 | 49 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 1,000 | 611 | 276 | 14 | 39 | 72 | 951 | 547 | 310 | 5 | 45 | 69 |

| 12 | 513 | 438 | 367 | 49 | 56 | 63 | 1,002 | 1,001 | 1,006 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 926 | 686 | 323 | 7 | 31 | 68 | 803 | 520 | 426 | 20 | 48 | 57 |

| 14 | 734 | 338 | 308 | 27 | 66 | 69 | 1,002 | 1,001 | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 761 | 565 | 468 | 24 | 43 | 53 | 1,005 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 603 | 468 | 315 | 40 | 53 | 68 | 1,010 | 1,003 | 872 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 17 | 837 | 501 | 223 | 16 | 50 | 78 | 392 | 298 | 219 | 61 | 70 | 78 |

| 18 | 342 | 296 | 280 | 66 | 70 | 72 | 547 | 490 | 325 | 45 | 51 | 67 |

| 19 | 576 | 439 | 416 | 42 | 56 | 58 | 256 | 244 | 197 | 74 | 76 | 80 |

| 20 | 306 | 296 | 297 | 69 | 70 | 70 | 929 | 874 | 404 | 7 | 13 | 60 |

| 21 | 618 | 409 | 318 | 38 | 59 | 68 | 352 | 217 | 148 | 65 | 78 | 85 |

| 22 | 515 | 394 | 337 | 49 | 61 | 66 | 660 | 512 | 421 | 34 | 49 | 58 |

| 23 | 581 | 307 | 156 | 42 | 69 | 84 | 1,001 | 712 | 933 | 0 | 29 | 7 |

| 24 | 665 | 544 | 465 | 33 | 46 | 54 | 1,004 | 1,001 | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 1,002 | 1,000 | 837 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 887 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 26* | 127 | 126 | 125 | 87 | 87 | 88 | 924 | 623 | 394 | 8 | 38 | 61 |

Table 3.

Differences between the biodegradation of deltamethrin in 5, 10 and 15-day cultures of neustonic (N) and epiphytic (E) bacteria

| Variable | N5 | N10 | N15 | E5 | E10 | E15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N5 | * | * | ns | ns | * | |

| N10 | * | * | ns | ns | ||

| N15 | * | * | ns | |||

| E5 | ns | * | ||||

| E10 | ns | |||||

| E15 |

*Difference statistically significant (P < 0.05)

ns Difference not significant

After 15 days of incubation, concentration of the pesticide in cultures of neustonic bacteria ranged from125 to 1,000 ng l−1 with the average of 401 ng l−1 (Table 2). Bacteria occurring in the surface microlayer decomposed deltamethrin with the effectiveness ranging from 0 to 87% with the average of 60%. All analyzed bacterial strains, with an exception of one strain, were capable of degrading deltamethrin. In 15-day cultures of epiphytic bacteria, concentration of deltamethrin ranged from 99 to 1,006 ng l−1 with an average of 534 ng l−1, while bacteria growing on reed epidermis decomposed this pesticide to 0–90% of its initial concentration. After a 15-day incubation, the average reduction of insecticide concentration equaled 47%. Twenty strains of epiphytic bacteria were found capable of decomposing deltamethrin.

According to available literature data regarding decomposition of deltamethrin in soil, this insecticide undergoes microbiological degradation in 1–2 weeks (Kidd and James 1991). Research on degradation of the following pyrethroids: biosmerin, permethrin, cypermethrin, deltamethrin, fenvalerate, chlorpyrifos, and pesticide Nurelle D 550 EC (mixture of 50 g cypemethrin and 500 g of chlorpyrifos in 1 liter) on a model of an aquatic ecosystem show that, among the analyzed compounds, deltamethrin had the highest rate of degradation with decomposition time amounting to 21 days (Lutnicka et al. 1999).

Table 2 presents results of analyses of deltamethrin biodegradation by pure strains of epiphytic and neustonic bacteria and by mixed cultures, containing 25 strains. According to these results, after 5, 10, and 15 days of incubation, the rate of deltamethrin biodegradation in mixed cultures of neustonic bacteria was higher than that in pure cultures. In the case of epiphytic bacteria, 5-day cultures, had higher capacity for decomposing the insecticide than 15-day cultures, the rate of deltamethrin biodegradation in mixed cultures was higher than the mean rate of biodegradation in pure cultures. More effective biodegradation of the analyzed insecticide in mixed cultures than in pure ones could be attributed to the prevalence of stimulating interactions over antagonistic interactions that occur among organisms from different genera and species in neustonic and epiphytic (after 15 days of incubation) bacterial cultures. Chodyniecki (1968) analyzed mixed cultures with various combinations of bacterial genera and found that 12% of bacterial interactions had antagonistic character and 8%, stimulating. This latter type of interactions and, most probably, also bacterial synergism occurred in mixed mixtures of bacteria, and as a result, these cultures decomposed deltamethrin more effectively than single strains of bacteria. Cooperation of microorganisms in feeding and growing processes enables rapid development of mixed cultures of bacteria. In consequence, this cooperation facilitates decomposition of many hard-to-biodegrade substances (Kołwzan et al. 2005).

Screening microorganisms with particularly high capacities for decomposing deltamethrin is very important in bioremediation of this type of pollutants. In spite of this, reports regarding isolation and identification of pure bacterial cultures capable of degrading deltamethrin are scarce and primarily describe soil environments.

According to Maloney et al. (1988), pure cultures of the Bacillus cereus and Pseudomons fluorescens species and bacteria from the Achromobacter genus are capable of decomposing deltamethrin with the concentration of 50 mg l−1 in the presence of Tween 80. The half-time of deltamethrin in oxygen cultures of these microorganisms ranged from 21 to 28 days. Grant et al. (2002) discovered that Pseudomonas sp. and Serratia sp. genera isolated from soil are useful in breaking down synthetic pyrethroids. Lee et al. (2004) isolated as many as 56 bacterial strains capable of decomposing synthetic perythroids from bottom sediments polluted with pesticides. According to Tellur et al. (2007), deltamethrin is degradable by bacteria from the Microccocus sp. genera.

Table 4 presents results of identification of the most efficient strains able to decompose deltamethrin.

Table 4.

Identification of the most efficient strains of neustonic and epiphytic bacteria used for the study on biodegradation of deltamethrin

| Neustonic bacteria | B (%) | Epiphytic bacteria | B (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 0 | E1 | 64 |

| N2 | 74 | E2 | 11 |

| N3 | 54 | E3 | 80 |

| N4 | 54 | E4 | 59 |

| N5 | 61 | E5 | 81 |

| N6 | 29 | E6 | 90 |

| N7 | 79 | E7 | 66 |

| N8 | 67 | E8 | 48 |

| N9 | 43 | E9 | 76 |

| N10 | 49 | E10 | 0 |

| N11 | 72 | E11 | 69 |

| N12 | 63 | E12 | 0 |

| N13 | 68 | E13 | 57 |

| N14 | 69 | E14 | 0 |

| N15 | 53 | E15 | 0 |

| N16 | 68 | E16 | 13 |

| N17 | 78 | E17 | 78 |

| N18 | 72 | E18 | 67 |

| N19 | 58 | E19 Pseudomonas luteola | 80 |

| N20 | 70 | E20 | 60 |

| N21 | 68 | E21 Aeromonas hydrophila | 85 |

| N22 | 66 | E22 | 58 |

| N23 Burkholderia cepacia | 84 | E23 | 7 |

| N24 | 54 | E24 | 0 |

| N25 | 16 | E25 | 11 |

B biodegradation in 15-day culture

It was demonstrated that among neustonic bacteria, strain no. 23 identified as Burkholderia cepacia was the most efficient microorganism in reducing the concentration of deltamethrin. Among the analyzed epiphytic bacteria, deltamethrin was degraded most effectively by the strain no. 19 identified as Pseudomonas luteola and by the strain no. 21 recognized as Aeromonas hydrophila.

Considering the results on generic composition of neustonic and epiphytic bacteria used for the study on biodegradation of deltamethrin one must realize that identification of strains using API systems may lead to biases in the interpretation of results hence we should treat them with a proper distance.

Bacterial species Burkholderia cepacia, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Aeromonas hydrophila, characterized by ability to decompose a wide spectrum of organic pollutants, including pesticides, are useful in bioremediation. The Burkholderia cepacia species demonstrates exceptional capability to decompose many structurally complex organic compounds. The abilities of this microorganism to decompose 2,4,5-trichloroacetic acid (Daubras et al. 1996), benzo(a)pyrene, dibenz(a,h)anthracene, coronene (Juhasz et al. 1997), p-nitrophenol (Bhushan et al. 2000), and other polyaromatic hydrocarbons (Kim et al. 2003) have been confirmed. Microorganisms from the Pseudomonadaceae family are particularly productive and decompose biotic and xenobiotic hydrocarbon substrates. Microorganisms from the Pseudomonas genus are characterized by an unprecedented tolerance for toxic compounds. The P. fluorescens grows in soils polluted with petroleum (Barathi and Vasudevan 2001) and is able to grow on a substrate containing polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (Soroka et al. 2001), while Pseudomonas sp. P166 grows in the presence of biphenyl (Jung et al. 2001). Aeromonas hydrophila, which is common in surface water (Szewczyk et al. 2000) has a wide spectrum of exoenzymes (amylase, protease, lipase, nuclease, and others), which are active in breaking down numerous organic compounds (Pemberton et al. 1997); it is also capable of decomposing a common herbicide, propanil (Dilek et al. 1996) and textile dyes (Chen et al. 2003) among other agents.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by KBN grant no. 2PO4G05229.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Barathi S, Vasudevan N. Utilization of petroleum hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas fluorescens isolated from a petroleum-contaminated soil. Environ Int. 2001;26:413–427. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(01)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B, Chauhan A, Samanta SK, Jain RK. Kinetics of biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by different bacteria. Biochem Biophis Res Commun. 2000;274:626–632. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RA, Tu CM, Harris CR, Cole C. Persistence of five pyrethroid insecticides in sterile and natural, mineral and organic soil. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1981;26:513–519. doi: 10.1007/BF01622129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K-H, Wu J-Y, Liou D-J, Hwang SZ-CHJ. Decolorization of the textile dyes by newly isolated bacterial strains. J Biotechnol. 2003;101:57–68. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(02)00303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodyniecki A (1968) Antibiosis and symbiosis among freshwater bacteria. Szczecin

- Daubner I. Water microbiology. Bratislava: Slov Akad Vied; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Daubras DL, Danganan CE, Hübner A, Ye RW, Hendrickson W, Chakrabarty AM. Biodegradation of 2, 4, 5-trichlorophenoxyacetoc acid by Burkholderia cepacia strain AC1100: evolutionary insight. Gene. 1996;179:1–16. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demoute JP. A brief review of the environmental fate and metabolism of pyrethroids. Pest Sci. 2006;27:375–385. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780270406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dilek FB, Anderson GK, Bloor J. Investigation into the microbiology of the rate jet-loop activated sludge reactor treating brewery wastewater. Wat Sci Tech. 1996;43:107–121. doi: 10.1016/0273-1223(96)00635-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer EB, Stapert EM, Sokolski WT. A medium for improved recovery of bacteria from water. Can J Microbiol. 1963;9:420–421. doi: 10.1139/m63-052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garabetian F, Romano JC, Paul R. Organic matter composition and pollutant enrichment of sea surface microlayer inside and outside slicks. Mar Environ Res. 1993;35:323–339. doi: 10.1016/0141-1136(93)90100-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garret WD. Collection of slick-forming materials from sea surface. Limnol Oceanogr. 1965;10:602–605. doi: 10.4319/lo.1965.10.4.0602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfreda L, Rao MA. Potential of extracellular enzymes in remediation of polluted soils: a review. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2004;35:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2004.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JT. The sea-surface microlayer: biology, chemistry, and anthropogenic enrichment. Prog Oceanogr. 1982;11:307–328. doi: 10.1016/0079-6611(82)90001-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz AL, Britz ML, Stanley GA. Degradation of benso(a)pyrene, dibenz(a, h)anthracene and coronene by Burkholderia cepacia. Wat Sci Tech. 1997;36:45–49. doi: 10.1016/S0273-1223(97)00641-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K-J, Kim E, So J-S, Koh S-CH. Specific biodegradation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) facilitated by plant terpenoids. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng. 2001;6:61–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02942252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SU, Behki RM, Tapping RI, Akhtar MH. Deltamethrin residues in an organic soil under laboratory conditions and its degradation by a bacterial strain. J Agric Food Chem. 1988;36:636–638. doi: 10.1021/jf00081a057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd H, James DR, editors. The agrochemicals handbook. 3. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry Information Services; 1991. pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kim TJ, Lee EY, Kim YJ, Cho K-S, Ryu HW. Degradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons by Burkholderia cepacia 2A–12. World J Microb Biotechnol. 2003;19:411–419. doi: 10.1023/A:1023998719787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kołwzan B, Adamiak W, Grabas K, Pawełczyk A. Podstawy mikrobiologii w ochronie środowiska. Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Gan, Kim J-S, Kabashima JN, Crowley DE. Microbial transformation of pyrethroid insecticides in aqueous and sediment phases. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2004;23:1–6. doi: 10.1897/03-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutnicka H, Bogacka T, Wolska L. Degradation of pyrethroids in an aquatic ecosystem model. Water Res. 1999;33:3441–3446. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(99)00054-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney SE, Maule A, Smith ARW. Microbial transformation of the pyretroid insecticides: permethrin, deltamethrin, fastac, and fluvalinate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2874–2876. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.11.2874-2876.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manadori L, Gambaro A, Piazza R, Ferrari S, Stortini AM, Moret, Capotaglio G. PCBs and PAHs in sea-surface microlayer and sub-surface water samples of the Venice Lagoon (Italy) Mar Pollut Bull. 2006;52:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. Neuronal ion channels as the targets sites of insecticides. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;79:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1996.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkrans B. Surface microlayers in aquatic environments. In: Alexander M, editor. Advances in microbial ecology. New York and London: Plenum Press; 1980. pp. 51–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlish V, Busharda J, McLauchlin A, Caux P-Y, Kent RA. Canadian water quality guidelines for deltamethrn. Environ Toxicol Wat Qual. 1998;13:175–210. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2256(1998)13:3<175::AID-TOX1>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton JM, Kidd SP, Schmidt R. Secreted enzymes of Aeromonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plimmer IR. Pesticide loss to atomosphere. Am Ind Med. 1990;18:461–466. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700180418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Różański L. Przemiany pestycydów w organizmach żywych i w środowisku. Warszawa: PWRiL; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sogorb MA, Vilanova E. Enzymes involved in the detoxification of organophosphorus, carbamate and pyrethroid insecticides through hydrolysis. Toxicol Lett. 2002;128:215–228. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4274(01)00543-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soroka YM, Samoilenko LS, Gvozdyak PI. Strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens 3 and Atrhrobacter sp. 2 degrading polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Microbiol Zh. 2001;63:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk U, Szewczyk R, Manz W, Schleifer KH. Microbial safety of drinking water. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:81–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellur PN, Megadi V B, Ninnekar HZ (2007) Biodegradation of cypermethrin by Micrococcus sp. strain CPN 1. Biodegradation. http://www.springerlink.com/content/m071432200687520. Accessed 10 September 2007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Warren N, Allan IJ, Carter JE, House WA, Parker A. Pesticides and other micro-organic contaminants in freshwater sedimentary environments-a review. Appl Geochem. 2003;18:159–167. doi: 10.1016/S0883-2927(02)00159-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wurl O, Obbard JP. Chlorinated pesticides and PCBs in the sea-surface microlayer and seawater samples of Singapore. Mar Pollut Bull. 2005;50:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GSH, Jia XM, Cheng TF, Ma XH, Zhao YH. Isolation and characterization of new carbendazim-degrading Ralstonia sp. strain. World J Microb Biotechnol. 2005;21:256–269. [Google Scholar]

- Zipper Ch, Nickel K, Angst W, Kohler HP. Complete microbial degradation of both enantiomers of the chiral herbicide mecoprop [(RS)-2-(chloro-2-methylphenoxy) propionic acid] in an Enantioselective Manner by Sphingomonas herbicidovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;12:4318–4322. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4318-4322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]