Abstract

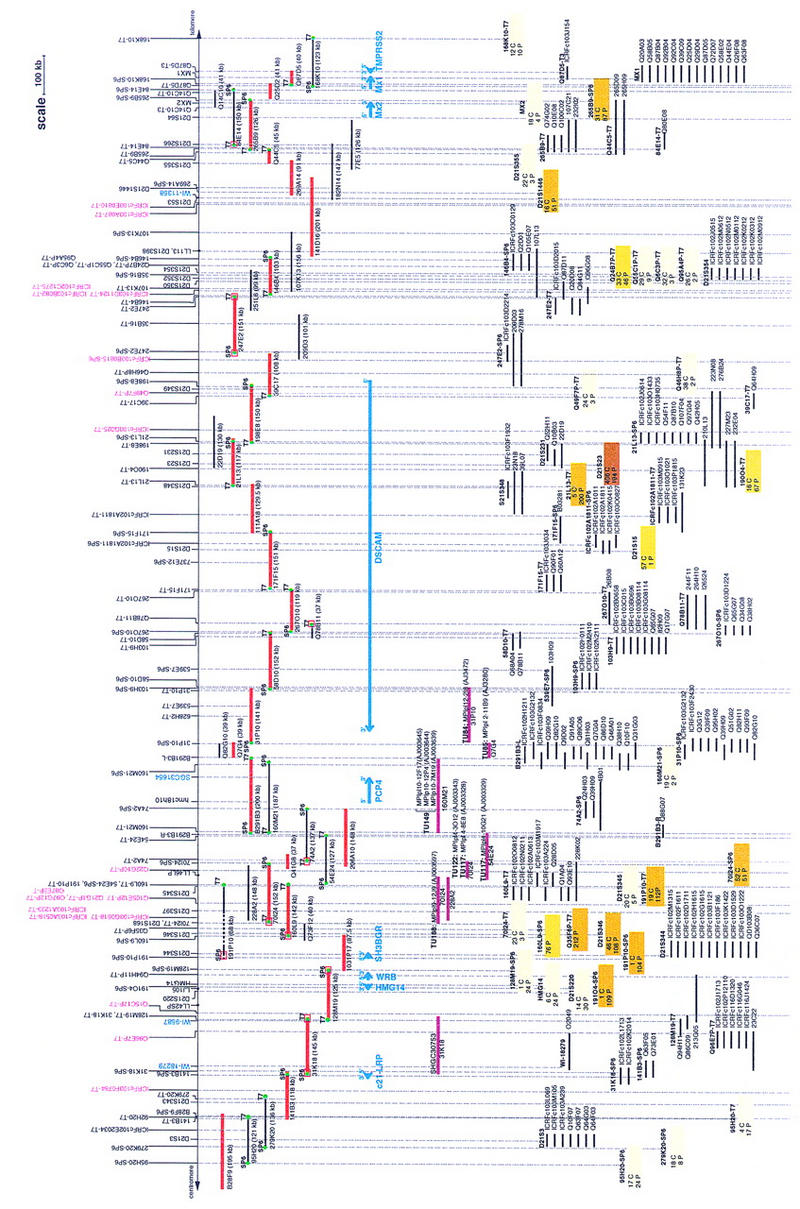

Progress in complete genomic sequencing of human chromosome 21 relies on the construction of high-quality bacterial clone maps spanning large chromosomal regions. To achieve this goal, we have applied a strategy based on nonradioactive hybridizations to contig building. A contiguous sequence-ready map was constructed in the Down syndrome congenital heart disease (DS-CHD) region in 21q22.2, as a framework for large-scale genomic sequencing and positional candidate gene approach. Contig assembly was performed essentially by high throughput nonisotopic screenings of genomic libraries, prior to clone validation by (1) restriction digest fingerprinting, (2) STS analysis, (3) Southern hybridizations, and (4) FISH analysis. The contig contains a total of 50 STSs, of which 13 were newly isolated. A minimum tiling path (MTP) was subsequently defined that consists of 20 PACs, 2 BACs, and 5 cosmids covering 3 Mb between D21S3 and MX1. Gene distribution in the region includes 9 known genes (c21–LRP, WRB, SH3BGR, HMG14, PCP4, DSCAM, MX2, MX1, and TMPRSS2) and 14 new additional gene signatures consisting of cDNA selection products and ESTs. Forthcoming genomic sequence information will unravel the structural organization of potential candidate genes involved in specific features of Down syndrome pathogenesis.

Research on Down syndrome (DS) has been the driving force behind molecular genetics analysis of human chromosome 21. A tremendous mapping effort was put forward, and YAC maps spanning most of 21q were established (Chumakov et al. 1992; Nizetic et al. 1994; Gardiner et al. 1995). Down syndrome is caused by trisomy 21, and the characteristic phenotype reflects the consequences of dosage imbalance for a set of genes localized on chromosome 21 (Epstein et al. 1991). The disease affects 1 in 700 live births and is the major cause of mental retardation and congenital heart disease. Rare documented cases of partial trisomy 21 allowed the mapping of specific DS phenotypic features into discrete chromosomal segments (Delabar et al. 1993; Korenberg et al. 1994). One of these candidate regions, the so-called DCR (DS critical region) that is associated with characteristic mental retardation and skeletal dysmorphies (Rahmani et al. 1989), has been a popular focus of investigation (Dahmane et al. 1995; Ohira et al. 1996, 1997; Osoegawa et al. 1996). However, the DCR boundaries are difficult to assess, owing in part to the variable and incomplete penetrance of most DS traits (Hernandez and Fisher 1996). Furthermore, there is significant evidence that other regions contribute to the complex phenotype (Korenberg et al. 1994). Congenital heart defects of the endocardial cushion (DS-CHD) and congenital gut conditions have been associated with a 5-Mb region in 21q22.2 encompassing D21S55 to MX (Korenberg et al. 1992). DS-CHD affects >40% of the DS patients. Genotype–phenotype correlation has prompted further mapping initiatives (Hubert et al. 1997) as a step toward candidate gene identification in the DS-CHD region.

Selection of positional candidates in large chromosomal regions requires extensive isolation of gene signatures. Gene discovery on chromosome 21 has taken a new turn in 1997 with the launching of a genomic sequencing program shared by a consortium of laboratories in Japan and Germany (Gardiner and Yaspo 1998). The whole long arm of chromosome 21 is scheduled to be sequenced by year 2000. Within this framework, construction of physical maps that achieve contiguity yet with minimum clone overlaps is a critical issue. To build long-range contigs adequate for genomic sequencing, we have applied a strategy based on high throughput nonisotopic screening of arrayed genomic libraries. We describe here a gapless sequence-ready map spanning 3 Mb between D21S3 and TMPRSS2 that is currently in the sequencing phase.

RESULTS

Strategy Used for Contig Assembly

Large-scale nonisotopic screenings of genomic libraries were used as a means to build contigs by hybridization. The strategy that we have applied was the following: (1) assembling primary contigs by high throughput hybridization of high-density grids; (2) gap-filling by multipoint walkings; and (3) clone fingerprinting by restriction digest.

Primary Contig Assembly

In a first step, a raw primary contig was assembled by multipoint high throughput screening of arrayed PAC (Ioannou et al. 1994) and cosmid libraries (Nizetic et al. 1991) using available markers and anchors previously localized in the targeted region (see Methods). We initially used 24 known STS markers for screening the genomic libraries. Although STSs provided one marker per 125 kb (24 STSs for 3 Mb) on average, the marker distribution across the region was uneven. In particular, the sole STS localized between D21S345 and D21S15, namely D21S347, was in fact mapping to 21q21 (data not shown), leaving a 700-kb gap between the flanking STSs. In an attempt to compensate for the STS distribution bias, we generated novel anchor points from ends of cosmids previously reported in this region: 25 cosmids from the YAC pocket map (pockets 125–132) (Nizetic et al. 1994) and 16 cosmids binned to YACs 767D6 and 784H7 (Soeda et al. 1995). All together, initial library screenings performed with 65 anchor probes derived from STSs and cosmid riboprobes identified a total of 1023 PACs and 956 cosmids. Filters were scored semiautomatically using the Xdigitize program keeping record of the relative signal intensity, referred to as either high, medium, or faint. A typical riboprobe hybridization on a PAC high-density grid is illustrated in Figure 1, showing in this case two positives. After the scoring of multiple hybridization experiments, data files were processed with the well2clone program. The well2clone package was designed for managing large hybridization data sets, providing also a dedicated database (Mott et al. 1993). These algorithms were applied previously in several mapping initiatives using high-density grids (Hoheisel et al. 1993; Nizetic et al. 1994). The initial function of well2clone is to merge the results of all single hybridization experiments held in separate files (each containing data of a given probe) into a large flat file. Then, the “probeorder” function allowed the ordering of probe and positive clones from the whole data set using simulated annealing, with the assumption that all probes are single copy. Finally, given an order of probes initially imposed by the user according to known STSs, the “reorder” function gave the best fitting order of clones. As a result, a contig file was calculated, containing all the positive hits that were, in practice, arranged in a series of stacks below their corresponding probes. Connections between clones were showed by “annealed clone groups,” hence suggesting possible contigs. Hybridization along the whole S3–MX region indicated that the number of hits per probe was clearly locus and probe dependent (Fig. 2), which may reflect the uneven representation of a given locus in the genomic libraries. For constructing the whole map (see below), we used a total of 112 probes. Out of these, 21 probes (19%) identified >50 clones in the PAC library (Table 1), possibly owing to low-copy repeats or paralogous sequences. This effect was particularly pronounced in the PAC library that is not chromosome specific. We identified a set of ∼250 PAC clones recurrently hit by nonrelated probes. Table 1 indicates that filtering out these nonspecific PACs was effective only for half of the probes, arguing in favor of the occurrence of paralogous hits for the other half. However, nonspecific hits were not a serious flaw in our approach because well2clone displays those hits as “singletons” that do not anneal with other clones from the nascent contig.

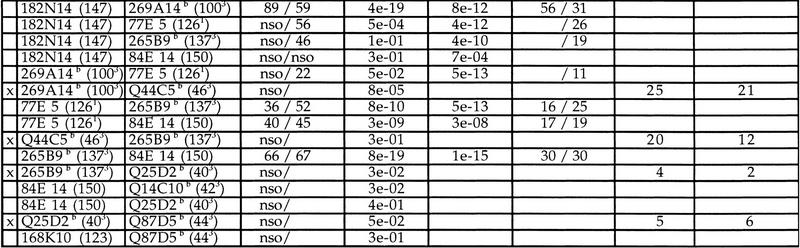

Figure 1.

Example of nonradioactive hybridization (DIG labeled) of a PAC filter containing 27,648 clones with riboprobe 54E24-SP6. Filter is bar-coded (at left). Image was captured by a CCD camera and analyzed with the Xdigitize program. A grid was automatically superimposed on the filter, that is, 48 × 48 squares placed around guide dots (black ink spotted on the filter). Each of the squares contains 12 different clones, spotted in duplicate around the central guide dot, according to the pattern shown in the Classification’s window. Each pair of numbers represents a clone pair (guide dot is noted by −9). Levels of relative intensities are indicated as follows: 3 = high, 2 = medium, and 1 = faint. Two positive clones were scored on this filter; the arrow indicates clone 228A2.

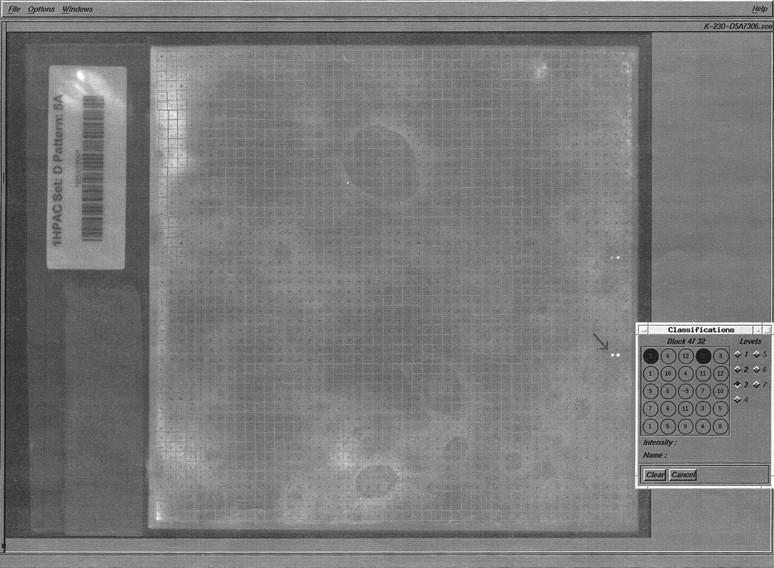

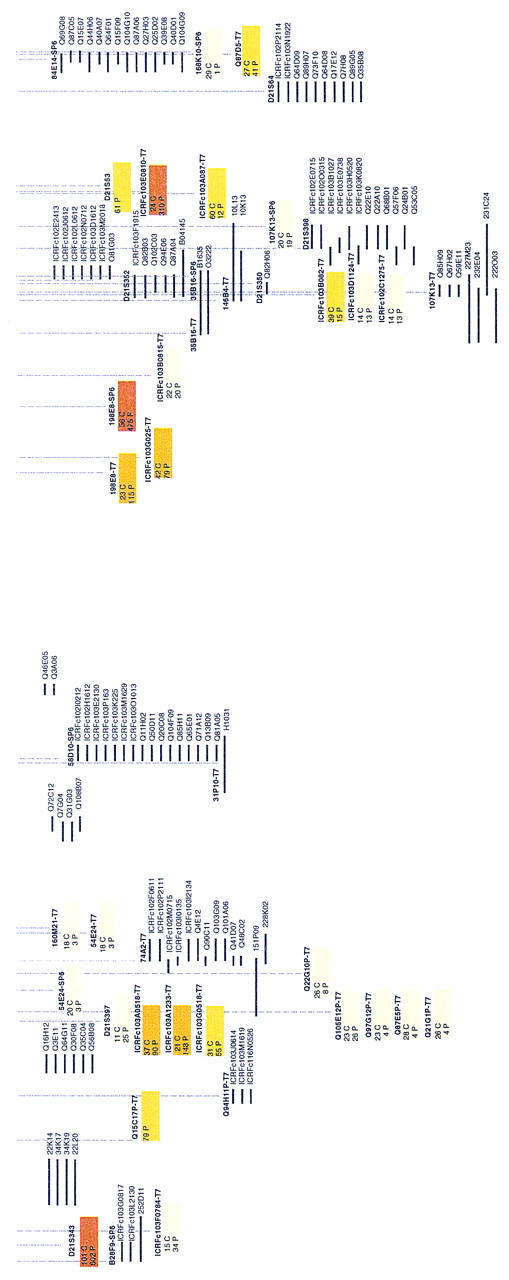

Figure 2.

Contig and gene map between D21S3 and TMPRSS2. The sequenced MTP consists of two BACs, 20 PACs, and five cosmids depicted in red. Sizes of clones are indicated in parentheses. Markers are shown above the clone map: STSs are displayed in the lower layer; EST markers are in blue. NotI linking clones are marked with a dot. Riboprobes are shown in the upper layer; riboprobes in magenta correspond to the initial cosmid anchors (pockets are prefixed by ICRF and Soeda’s bins by Q). Riboprobes used for Southern hybridizations to confirm the contig are shown as follows: DIG riboprobes are marked by a green dot and 32P-labeled riboprobes by a red square at the end of corresponding clones. Known genes are depicted by blue lines below the clones. Transcription units (TUs) are indicated below the PACs in magenta. The raw primary data are shown below the actual MTP and gene map. Positive clone names are given for probes showing <20 hits. Color boxes correspond to probes identifying >20 clones for which only numbers are given (cosmids are indicated by a C and PACs by a P). Box color shadings are as follows: 20–50 hits are light yellow, 50–100 hits are yellow, 100–200 hits are dark yellow, and >200 hits are brown. Each probe is indicated above the clone stack.

Table 1.

Hits for Probes Hybridizing to a Large Number of PACs

| Probe name | No. of positives before filtering | No. of positives after filtering |

|---|---|---|

| D21S343 | 602 | 602 |

| 191O4-SP6 | 109 | 60 |

| 191P10-SP6 | 104 | 13 |

| 160L9-SP6 | 76 | 76 |

| D21S346 | 108 | 107 |

| Q35F6P-T7 | 212 | 212 |

| ICRFc103G0518-T7 | 55 | 46 |

| ICRFc103A0518-T7 | 90 | 65 |

| ICRFc103A1233-T7 | 148 | 68 |

| 191P10-T7 | 112 | 14 |

| 70I24-SP6 | 51 | 51 |

| 21L13-T7 | 200 | 89 |

| 190O4-T7 | 67 | 5 |

| D21S23 | 194 | 194 |

| 198E8-T7 | 115 | 24 |

| ICRFc103G025-T7 | 79 | 74 |

| 198E8-SP6 | 475 | 475 |

| ICRFc103E0810-T7 | 310 | 258 |

| D21S53 | 61 | 6 |

| D21S1446 | 51 | 0 |

| 265B9-SP6 | 87 | 84 |

Numbers are given before and after filtering against a set of 200 clones recurrently identified by nonrelated probes.

After fitting the relative order of probes suggested by well2clone with the position of known markers, we constructed a raw primary contig covering 2.2 Mb. Remaining gaps were detected by the program in regions of the contig that were not annealed. The largest gap located between D21S345 and D21S15 indicated that cosmid anchors did not compensate for the lack of STSs, because they were located on either side of the gap (Fig. 2). Only 20 of 41 cosmids identified PACs that could be annealed within the contig (11 of 25 cosmids from the pocket map and 9 of 16 cosmids from Soeda, respectively). Other cosmids appeared to map elsewhere on chromosome 21.

Gap Closure and STS Analysis

A subset of ∼200 clones was chosen from the primary contig, considering mainly strong positive clones that were part of an annealed contig as defined by hybridization data. The STS content of the selected clones was tested by PCR for all markers lying within 500 kb of the estimated clone position. Between 30% and 90% of PACs were confirmed to be real positives, reflecting the relative specificity of the initial probe. Clone overlaps were primarily determined from shared STSs, from which we deduced intervals between markers. At this stage, further rounds of hybridizations were performed with riboprobes derived from PCR-validated clones to (1) identify overlaps, (2) orient clones, and (3) fill the gaps. The 700-kb gap between D21S15 and D21S345 was filled by a walking strategy using riboprobes located at the outer edge of existing contigs, 70I24-SP6 and 171F15-T7 (Fig. 2). PAC 267O10, identified by 171F15-T7, was used as a probe and did hit PAC 58D10. A further walk with 58D10-SP6 identified PAC 31P10. Walking steps from the centromeric side of the gap (70I24-SP6) identified a path of clones confirmed by Southern blot hybridization (not shown) where finally the cosmids Q7G4 and Q82G10 did bridge BAC 291B3 and PAC 31P10 (Fig. 2). Another gap of ∼100 kb was detected between HMG14 and D21S346. Two riboprobes derived from clones flanking this gap (128M19-SP6 and 191P1O-SP6) simultaneously identified a single PAC (1031P17); the bridge was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting (not shown).

In summary, a total of 112 nonisotopic screenings (88 riboprobes and 24 STSs) were used for constructing the whole map. Data are summarized in Figure 2, showing the clone coverage at each locus. PAC coverage along the whole region was 21 times on average (431 clones with a mean size of 150 kb), excluding from this figure the 21 probes that gave noisy hybridization (shown in Table 1). Coverage with cosmid clones was 11 times.

Thirteen new STSs were generated from end sequences derived from one BAC, five PACs, and two cosmids (Table 2). Additional markers were also tested on the contig: four ESTs (SGC31654, WI-18279, WI-9587, and WI-11358), PCP4 (Chen et al. 1996), and seven recently published STSs (28F9-SP6, 31P10-SP6, 31P10-T7, 737E2-SP6, 628H2-T7, 539E7-SP6, and 539E7-T7) (Hubert et al. 1997). Table 3 summarizes all STS screening data corresponding to the map shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Amplimers Derived from Direct Sequencing of PAC, BAC, or Cosmid Ends

| STS | P1 (5′ → 3′) | P2 (5′ → 3′) | STS size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 141B3-T7 | GGGGGTTTGGTGTTATTGAC | ATCCTTCCTGATGGCAACTA | 246 |

| 141B3-SP6 | TGTCAGGTGTGTACCTGTGA | CAGCATACCTACTTAAGGGG | 150 |

| 128M19-SP6 | GTGAGGTCCTGAATCATCC | ACTCCCAAGAGCTGAAGGT | 160 |

| 70I24-T7 | GGGTAAGCTCGTTTCTGG | AGGGAGAGATGCTAGAAGC | 230 |

| 70I24-SP6 | AGGAACTAGTGCTCAGCTGG | GCACTCTAAGACTGCCACC | 235 |

| B291B3R | CCAACAACCATCGGTTAATCTTCT | TAATAGAGATGTGACTACAGATTG | 165 |

| B291B3L | TGACATGCATAACTCACGA | CTCATTGTAATACCTTCGC | 117 |

| 171F15-T7 | GGAGTACCATTAGGTGTTTTC | CTGCACATAATTATAAATCG | 255 |

| 269A14-SP6 | GGCTAGGAGGCAGCATCG | TAATACCCTTGGGACGGG | 339 |

| Q14C10- T3 | TGCTGCTCACTCAGCATG | ACAAAGGTCTTGAGCGCC | 170 |

| Q14C10- T7 | GAGTTCAGGCCTGGGACG | TCTTACCCTCTGATATGCGG | 320 |

| Q87D5-T7 | GGATTTGGAGCCATTGCC | AACCTCCACAGAACCGCC | 251 |

| Q87D5-T3 | GGTTTCTTGGCTGTGTGGTT | ATACTTCTGTGTGACAACCG | 146 |

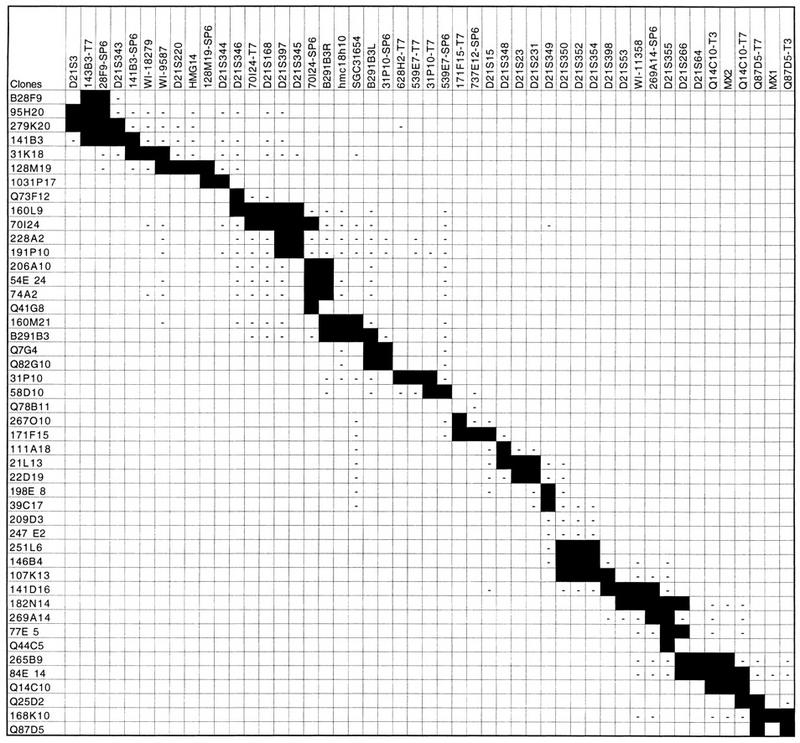

Table 3.

Summary of the STS Screenings

|

Solid boxes indicate positive PCR results; negative sign (−) indicates a negative PCR result for the STS tested.

FISH

Sixty-three clones were analyzed by FISH on metaphase chromosomes during the course of this study (data not shown); 55 clones (87%) mapped to chromosome 21 at a single locus. Six clones mapped to different chromosomes and two clones were localized to a proximal location on chromosome 21.

Restriction Fingerprinting Analysis

Contig construction using the well2clone software has the inherent limitation that sizes of clones and overlaps cannot be displayed. Fingerprinting was thus performed for the 55 fished clones, using EcoRI or HindIII, as illustrated in Figure 3A. Gel images were digitized and processed with the Image 3 and FPC programs (Sulston et al. 1989; Soderlund et al. 1997) to estimate the clone sizes and overlaps by analysis of the fingerprinting patterns. We observed that clone sizes were generally underestimated by 8% in EcoRI gels and by 18% in HindIII gels, as compared with the size determined by genomic sequencing (data not shown). This was owing in part to the fact that restriction fragments <500 bp were not included in the FPC analysis. Also, fragments comigrating with other insert bands or with vector fragments (two fragments for EcoRI and four for HindIII) may be omitted. Different vector–insert junctions obtained with these enzymes also contribute to the size discrepancy seen between EcoRI and HindIII patterns. Clone sizing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after NotI digestion was the most accurate, with a variation of only 4% from sequencing data (not shown). The estimation of clone overlaps calculated by FPC is presented in Table 4. Discrepancies observed in clone sizes are reflected in the estimation of overlaps. For the 12 pairs of clones that were digested with both enzymes, the overlap may vary from 10% to 50% between EcoRI and HindIII estimations. For the 26 pairs of clones representing the final sequenced MTP (marked with an “x” in Table 4), only three overlaps were found by FPC, whose sizes were consistent with genomic sequence data. For the other clones, evidence of overlaps was confirmed independently by Southern hybridization or PCR. Data indicate that when using only EcoRI or HindIII and under the parameters used (cutoff probability of 10−7), FPC failed to detect clone overlap <30 kb. The large 65-kb overlap for pair 31P10–58D10 was detected by FPC but above the threshold of 10−7 (Table 4). Overlaps determined by genomic sequencing ranged from 4 kb to 80 kb but was generally below 20 kb.

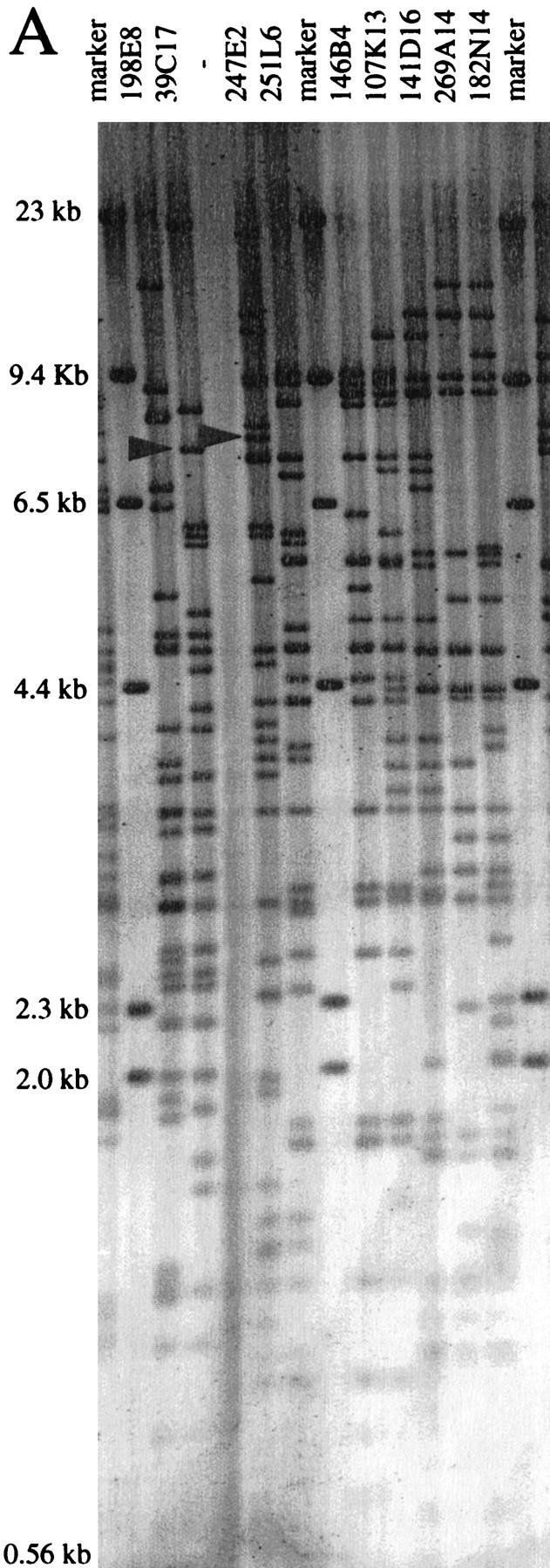

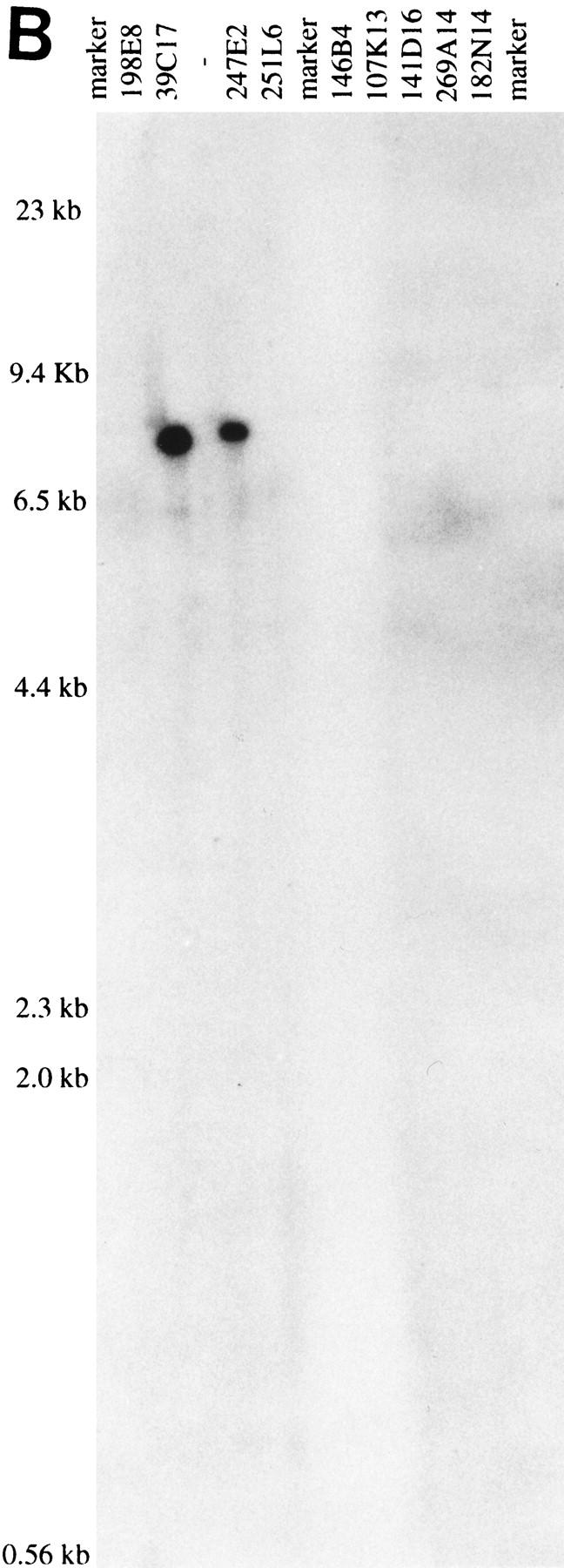

Figure 3.

(A) Vistra green-stained agarose gel of HindIII digest patterns of nine PACs. Marker lanes correspond to λ HindIII. Arrows in lanes 39C17 and 247E2 indicate the position of the restriction fragments identified by 247E2-SP6 riboprobe in B. (B) Autoradiograph from a Southern hybridization of the gel shown in A confirming the overlap between PACs 247E2 and 39C17. Radiolabeled 247E2-SP6 riboprobe identified a single HindIII fragment in PACs 39C17 and 247E2.

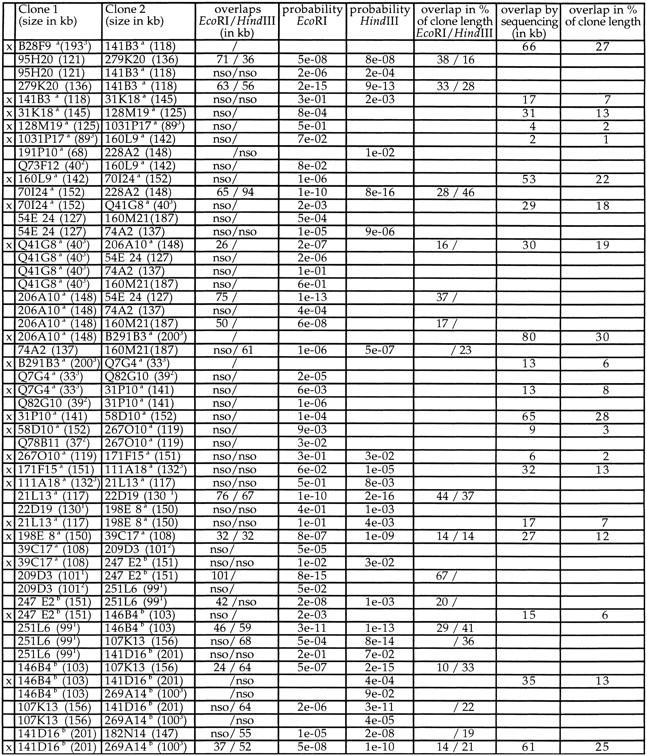

Table 4.

Summary of Clone Sizes and Overlap for All Clones Analyzed by Fingerprinting

Clone sizes (kb) indicated in brackets were generally estimated by PFGE, or by the mean FPC value form EcoRI and HindIII patterns(1) by the FPC value from EcoRI pattern(2) or from genomic sequencing(3). Overlaps (in kb) between clones estimated by FPC after EcoRI or HindIII digestion are shown with the corresponding probability value: (nso) no significant overlap; (/) no FPC data available. When available, overlaps calculated from genomic sequence are given (in kb). Clone to clone overlaps were also calculated in percent of the actual length spanned by a given pair of clones. Cosmids are prefixed with a Q and BACs with a B. The sequenced clones are indicated with an x in the first column. Sequences are available at ahttp://genome.imb-jena.de (Note: cosmids are displayed in 384-well format on this server; Q73F12 = 19K23, Q41G8 = M1511, Q7G4 = 2N7, Q82G10 = 21M20, and Q78B7-20C22) or at bhttp://seq.mpimg-berlin-dahlem.mpg.de (identical names).

Only four of the PACs analyzed by restriction digest were found grossly deleted, as detected by abnormal restriction pattern. STS content and riboprobe hybridization data indicated that PAC 191P10 had suffered an internal deletion.

Transcript Map

Localization and orientation of nine known genes reported previously in this region are shown in Figure 2. We have also localized nine additional potential transcripts grouped in six transcriptional units (TU84, TU85, TU117, TU122, TU149, and TU188) that were isolated previously in the course of constructing a whole chromosome 21 transcript map (Yaspo et al. 1995; M.L. Yaspo, unpubl.). Essentially, the transcript map consists of gene fragments originating from cDNA selection (Parimoo et al. 1991; Korn et al. 1992) and exon trapping (Church et al. 1994) that have been systematically mapped to human genomic libraries (Yaspo et al. 1995). TU188 (EMBL accession no. AJ003597) shows 60% homology and 42% identity with β-1,3-galactosyltransferases. cDNA MPIpl12-2I8 (EMBL accession no. AJ003472, 355 bp) shows 50% homology over its whole length with Titin genes and is likely to be part of DSCAM, also displaying a regional homology with Titin (Yamakawa et al. 1998). We have also remapped and ordered five STSs from the Unigene EST set (Schuler et al. 1996). It is worth mentioning that no additional transcripts were mapped in the 700-kb region spanned by DSCAM (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

A nonisotopic hybridization-based strategy was applied for building a contiguous contig spanning 3 Mb from D21S3 to MX. Semiautomated hybridization and detection procedures enabled the managing of high throughput screenings and data processing. The well2clone program was compulsory for the efficient managing of this large data set and for establishing relationships between clones forming tentative contigs. The initial screenings were performed with 65 probes corresponding to a marker density of  kb. After gap closure achieved by walking steps, a total of 112 nonradioactive probes (STSs, riboprobes, cDNAs) appeared necessary for constructing the 3-Mb gapless map (1 probe per 27 kb). Noisy hybridizations were observed for 19% of the probes, in particular in the PAC library. Because the PAC library is not chromosome specific, one explanation for this phenomenon is the relatively frequent occurrence of interchromosomal paralogous regions that lead to the identification of clones mapping to other chromosomes (Eichler et al. 1997; Lauer et al. 1997). The presence of low-copy repetitive sequences that are not blocked efficiently at the Cot used during probe competition may also account for this observation. From our experience, those hits are not attributable to the nonisotopic hybridization technique but, rather, are inherent to filter grid screenings. This drawback has been reported previously in another study, using radioactively labeled probes for constructing a large PAC contig (Niederfuehr et al. 1998). However, identification of spurious paralogs or repeats did not represent a serious flaw in the later stages of contig construction. The clone depth was >20 times over the whole region with a dense distribution of probes, thus giving a prospect for choosing suitable clones.

kb. After gap closure achieved by walking steps, a total of 112 nonradioactive probes (STSs, riboprobes, cDNAs) appeared necessary for constructing the 3-Mb gapless map (1 probe per 27 kb). Noisy hybridizations were observed for 19% of the probes, in particular in the PAC library. Because the PAC library is not chromosome specific, one explanation for this phenomenon is the relatively frequent occurrence of interchromosomal paralogous regions that lead to the identification of clones mapping to other chromosomes (Eichler et al. 1997; Lauer et al. 1997). The presence of low-copy repetitive sequences that are not blocked efficiently at the Cot used during probe competition may also account for this observation. From our experience, those hits are not attributable to the nonisotopic hybridization technique but, rather, are inherent to filter grid screenings. This drawback has been reported previously in another study, using radioactively labeled probes for constructing a large PAC contig (Niederfuehr et al. 1998). However, identification of spurious paralogs or repeats did not represent a serious flaw in the later stages of contig construction. The clone depth was >20 times over the whole region with a dense distribution of probes, thus giving a prospect for choosing suitable clones.

Nonisotopic screenings represent a substantial advance in the setup of high throughput mapping. The contig built by hybridization was then confirmed by applying independent analysis methods to define a minimum tiling path (MTP) for genomic sequencing. Clones were anchored to their neighbors on the basis of shared STSs, fingerprinting, and Southern blot hybridizations. Thirteen novel STSs have been generated, and the contig contains a total of 50 STSs including NotI linking clones, hence anchoring the contig to the NotI physical map (Ichikawa et al. 1992). This provides a valuable backbone allowing the estimation of real distances between markers. However, hybridization-based contig construction does not give the size of clones and overlaps, which were estimated here by fingerprinting. Using FPC as a means to calculate whether a pattern of fragments common to two clones is significant or not, we set the probability cutoff to <10−7. Discrepancies between values obtained for EcoRI and HindIII patterns were seen in 6 of 12 pairs of clones for which data could be compared. Besides, only 3 overlaps were found significant among the 26 pairs of overlapping clones chosen for the MTP. When compared with sequencing data available for 23 of 26 pairs, overlaps ranged from 2 to 32 kb, except for 5 pairs showing larger values. Actual overlaps range between 1% and 30% of the clone length, with a mean clone to clone overlap of 13% over the whole map. As a conclusion, analyzing patterns from only one enzyme, either EcoRI or HindIII, was not an adequate choice for detecting overlaps <30 kb. Also, the parameters set for FPC may have been too stringent; when considering a probability cutoff <10−5, nine additional overlaps are detected (Table 4). A more complex restriction pattern would be an advantage, for instance, using these two enzymes in combination. In contrast to other studies (Mara et al. 1997), the contribution of FPC in our hybridization-based approach as not used as a means to define tentative contigs, thus limiting the impact of nondetected overlaps. The overall strategy was proven adequate to construct a sequence-ready map consisting of 20 PACs, 2 BACs, and 5 cosmids. The use of two cloning systems, PAC and cosmids, gave a chance to identify three “cosmid bridges” between PACs, hence minimizing sequencing redundancy. The average clone to clone overlap is 13% over the whole region.

As compared with an STS-based BAC contig published previously and encompassing the same region (Hubert et al. 1997), we have closed two large gaps and produced a dense map with precise marker distances integrated with gene position and orientation. Few clones were found in common in the two maps, because we used PACs and cosmids instead of BACs. In this region thought to be associated to DS congenital heart and gut diseases (Korenberg et al. 1992), only nine genes are known to date: c21–LRP (Vidal-Taboada et al. 1998); HMG14 (Petersen et al. 1990); WRB (Egeo et al. 1998); SH3BGR (Scartezzini et al. 1997); PCP4 (Chen et al. 1996; Hubert and Korenberg 1997); DSCAM (Yamakawa et al. 1998); MX2, MX1 (Horisberger et al. 1988); and TMPRSS2 (Paoloni-Giacobino 1997). DSCAM, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily potentially involved in neural differentiation, spans a previous 800-kb gap in the map. No EST has been mapped in the region spanned by DSCAM, and it will be interesting to see if another gene will be predicted there by genomic sequencing. We have isolated 14 anonymous potential transcripts between S3 and MX. It is difficult to estimate how many genes they represent since some may cluster within the same gene. Interestingly, a partial cDNA from TU188 (accession no. AJ003597) shows 60% homology with β-1,3-galactosyltransferases. β-Galactosyltransferases belong to a gene family of wide structural diversity, playing a role in cell adhesion and cell proliferation processes (Shur 1993; Hathaway and Shur 1996). These gene signatures will assist experimental confirmation of novel gene models predicted in silico from genomic sequence. We can estimate that the S3–TMPRSS2 contig contains ∼20 genes, thus representing a gene density of  kb.

kb.

Large-scale genomic sequencing projects rely on the concomitant development of bacterial clone-based maps. Establishing the basic clone resource is often a trade-off between coverage and contiguity. We have shown here that nonisotopic hybridization technology can be successfully applied to build maps fulfilling these criteria. To the best of our knowledge, the contig shown in this study is gapless between S3 and TMPRSS2, although we cannot rule out small rearrangements such as internal deletions of the chosen clones. The corresponding sequence is freely available (http://genome.imb-jena.de/ and http://seq.mpimg-berlin-dahlem.mpg.de). Importantly, the sequenced map will provide essential molecular tools for diagnostic purposes, positional candidate gene approach, and in-depth analysis of all genes and associated regulatory elements in the DS-CHD region.

METHODS

Nonradioactive Screening of Arrayed Genomic Libraries

Three cosmid libraries have been used, constructed from flow-sorted chromosome 21. The LL21NCO2 “Q” library constructed at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory contains 10,464 clones, representing a sevenfold chromosome coverage. The ICRFc102 and ICRFc103 libraries were constructed at the Imperial Cancer Research Foundation (ICRF) (Nizetic et al. 1991) and contain together 16,896 clones representing 11 equivalents of chromosome 21.

We have used a part of the PAC RPCI-1 library (Ioannou et al. 1994), representing 2.5 times human genome equivalents.

All libraries were gridded at high density onto Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham). Clones were spotted in duplicate using a 5 × 5 pattern with guide dots to facilitate scoring of positives. This spotting pattern allows more than 55,000 clones to be spotted onto one 22 × 22-cm nylon membrane. Filters were laminated onto a plastic support (Bancroft et al. 1997) and bar-coded to facilitate data tracking and high throughput handling.

All probes were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG-11–dUTP) (Boehringer Mannheim). STSs and cDNAs were labeled by incorporating DIG-11–dUTP by PCR substituting part of the dTTP in the reaction (0.2 mm dATP, dCTP, and dGTP; 0.19 mm dTTP/0.01 mm DIG-11–dUTP). Riboprobes were prepared from 1–2 μg of template DNA and synthesized by in vitro transcription using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerases according to the manufacturer recommendations (Boehringer Mannheim). To block repetitive sequences, probes were competed with 100 μg of sheared human placental DNA (Sigma) at 65°C for 1.5 hr.

DIG-labeled probes were denatured for 10 min and diluted in 2.5 ml of Church buffer for each filter (Church buffer consists of 0.25 m Na2HPO4 at pH 7.2, 1.25 mm EDTA, and 5% SDS and is warmed to 65°C before hybridization). The probe solution was evenly sprayed onto each filter using an air-spray gun (air pressure 3,5-4 bar), and laminated filters were stacked on top of each other in a plastic bag. Generally, we placed 40 large filters per bag, and all of the washing solution volumes are given for 40 filters. Hybridizations were performed overnight at 65°C. Filters were washed in 2 liters of 20 mm Na2HPO4, 0.1% SDS, for 15 min at room temperature, followed by a second wash for 20 min in the same solution at 65°C.

Detection was performed using the Attophos system (Maier et al. 1994). Prior to detection, filters were washed in a 2-liter blocking solution (5% milk powder/PBS) solution for 45 min at room temperature. Each filter was sprayed with 2.5 ml of anti-digoxygenin–alkaline phosphatase antibody solution (Boehringer Mannheim; diluted 1:5000 in 5% milk powder/PBS), using the air-spray gun. Excess of antibody was removed by washing the filters two times each for 30 min in 2-liter volumes of PBS at room temperature. Filters were washed two times in 2-liter volumes of 0.1 m Tris, 1 mm MgCl2 (pH 9.5) at room temperature for 10 min. Then, filters were sprayed with a 2.5-ml solution containing the fluorescent substrate Attophos (JBL Scientific) (0.08 m Tris/0.8 mm MgCl2 at pH 9.5, 0.48 m diethanolamine/0.046 mm MgCl2/0.001% NaN3, and 1 mm Attophos). After incubation at 37°C for 4 hr, positive signals were visualized under long-wave UV light. Images were captured with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera and saved as a TIFF format file.

Images were processed and scored semiautomatically using the Xdigitize program developed in our department. Xdigitize converts the position of positives on the gridded filter to the actual clone name in the library. Data were transferred automatically to a dedicated database, and analysis proceeded with the well2clone program for primary contig assembly (Mott et al. 1993). Well2clone is a dedicated suite of programs written for building contigs from hybridization data. It serves a dual purpose, providing a database managing all hybridization data (listing probes and matching positives) and allowing the building of contigs using the related functions probeorder or reorder. well2clone is freely available by ftp at (ftp://ftp.mpimg-berlin-dahlem.mpg.de/pub/lehrach/users/andy/icrf_contigv2.6.tar.Z). Xdigitize is freely available upon request.

Restriction Digest Fingerprinting

DNAs (8 μg/reaction) were digested with either EcoRI or HindIII restriction enzymes. DNA fragments were separated onto agarose gels (25.5 cm, cast in 0.8% agarose), electrophoresed in 1× TAE buffer for 24 hr at 1.6 V/cm. DNA staining was performed with Vistra Green (0.01%) (Amersham), and images were captured with the Fluor-Imager 575 (Molecular Dynamics). Gel images were analyzed with the program Image3 (Sulston et al. 1989). The data from Image3 was exported to the FPC program (Soderlund et al. 1997). FPC is an interactive program used for building contigs from fingerprinted clones. Analysis was performed setting the following parameters: tolerance = 7, cutoff = 10e−07, diff = 0.3, diffbury = 0.1, minimal bands = 3, and minimal ends = 8. Restriction patterns were compared for shared fragments, and overlapping clones were clustered automatically. In all cases, overlaps were verified manually by the user.

For Southern blotting, DNAs were transferred onto Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham) using standard conditions. Radioactive riboprobes were labeled with 50 μCi [α-32P]CTP. Radioactive riboprobes were competed as for DIG-labeled probes. Hybridizations were performed in (5× SSPE, 5× Denhardt’s, 50% formamide, 1% SDS, and 5 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA) overnight at 42°C. Filters were washed to (2× SSC/0.1% SDS) at 65°C. Filters were exposed onto X-ray films (Kodak, X-OMAT-AR).

PFGE

PAC DNAs (1–2 μg) were digested with NotI restriction enzyme (Biolabs) for 2 hr at 37°C in the appropriate buffer. PFGE was performed in 0.5× TBE and 1% agarose gels (Seakem GTG; FMC), using the CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad). Electrophoresis was performed at 6 V/cm for 20 hr at 14°C with a 4- to 20-sec ramp. DNA markers were long-range λ-ladder (multimers of 48.5 kb; Bio-Rad) and mid-range λ DNA (mono-cut mix; Biolabs).

STS Content

PCRs were performed in PCR buffer [10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.3, 50 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.001% (wt/vol) gelatin], with 10 pmoles of each primer, 0.2 mm dNTPs, and 1.25 unit of Taq polymerase (AmpliTaq) (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) in a total volume of 25 μl. Amplifications were performed with a denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of amplification (94°C for 45 sec, annealing at primer-specific temperatures for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 1 min) and a final extension at 72°C for 4 min.

FISH

Metaphase chromosomes were prepared from human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Standard FISH protocols were followed (Ward et al.1995). Briefly, the slides were treated with 100 μg/ml RNase A in 2× SSC at 37°C for at least 30 min and with 0.01% pepsin in 10 mm HCl at 37°C for 10 min and then dehydrated in an ethanol series (70%, 85%, and 100%). Slides were denatured at 95°C in 70% formamide and 2× SSC (pH 7.0) and again dehydrated in a cold alcohol series. Probes were labeled by standard nick translation procedures with either biotin-16–dUTP or digoxigenin-11–dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim). Labeled DNA was coprecipitated with human Cot-1 competitor DNA (GIBCO-BRL) and herring sperm carrier DNA and redissolved in 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 2× SSC. After a 10-min denaturation at 80°C, 10 μl of hybridization mixture was applied to each slide and sealed under a coverslip. Slides were left to hybridize in a moist chamber at 37°C for 1–3 days. Slides were washed to 0.1× SSC for 5 min at 60°C. Biotinylated probes were detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated avidin (Vector) and digoxigenated probes by Cy3-conjugated anti-digoxygenin antibody (Dianova). Chromosomes were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were taken with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope equipped with a thermoelectronically cooled CCD camera (Photometrics CH250).

Acknowledgments

We thank the RZPD Resource Center for supplying filters and clones. Jörn Steiger and Beatrix Roehrdanz are thanked for excellent technical assistance. We thank Huw Griffith for the Xdigitize program, Dr. Juliane Ramser and Dr. Stefan Taudien for sharing genomic sequence information, Dr. Thomas Haaf for providing the FISH facilities, Dr Peter de Jong for the LL21NCO2 “Q” and PAC libraries, and Dr. Julie Korenberg for supplying BACs 28F9 and 291B3. This work was supported by the Deutsches Humangenomeprojekt (DMBF grant 01KW 9608).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

NOTE

Clone names that are not given in Figure 2 owing to space limitations are freely available upon request and on the primary database of the RZPD server (http://www.rzpd.de/).

Footnotes

E-MAIL yaspo@mpimg-berlin-dahlem.mpg.de; FAX 49-30-8413-1128.

REFERENCES

- Bancroft DR, O’Brien JK, Guerasimova A, Lehrach H. Simplified handling of high density genetic filters using rigid plastic laminates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4160–4161. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.20.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HM, Bouras C, Antonarakis SE. Cloning of the cDNA for a human homolog of the rat pep-19 gene and mapping to chromosome 21q22.2-q22.3. Hum Genet. 1996;98:672–677. doi: 10.1007/s004390050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov I, Rigault P, Guillou S, Ougen P, Billaut A, Guasconi G, Gervy P, LeGall I, Soularue P, Grinas L, et al. Continuum of overlapping clones spanning the entire human chromosome 21q. Nature. 1992;359:380–387. doi: 10.1038/359380a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church DM, Stotler CJ, Rutter JL, Murrell JR, Trofatter JA, Buckler AJ. Isolation of genes from complex sources of mammalian genomic DNA using exon amplification. Nature Genet. 1994;6:98–105. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmane N, Charron G, Lopes C, Yaspo ML, Maunoury C, Decorte L, Sinet PM, Bloch B, Delabar JM. Down syndrome critical region contains a gene homologous to drosophila sim expressed during rat and human central nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:9191–9195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delabar JM, Creau N, Sinet PM, Ritter O, Antonarakis SE, Burmeister M, Chakravarti A, Nizetic D, Ohki M, Patterson D, et al. Report of the Fourth International Workshop on Human Chromosome 21. Genomics. 1993;18:735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeo A, Sotgia F, Arrigo P, Oliva R, Bergonon R, Nizetic D, Rasore-Quartino A, Scartezzini P. Identification and characterization of a new human cDNA from chromosome 21q22.3 encoding a basic nuclear protein. Hum Genet. 1998;102:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s004390050693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE, Budarf ML, Rocchi M, Deaven LL, Doggett NA, Baldini A, Nelson DL, Mohrenweiser HW. Interchromosomal duplications of the adrenoleukodystrophy locus: A phenomenon of pericentromeric plasticity. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:991–1002. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein CJ, Korenberg JR, Anneren G, Antonarakis SE, Ayme S, Courchesne E, Epstein LB, Fowler A, Groner Y, Huret JL, et al. Protocols to establish genotype-phenotype correlations in Down syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49:207–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner K, Yaspo M-L. Report of the Seventh International Workshop on Human Chromosome 21 Mapping. 1997. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;82:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000015055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner K, Graw S, Ichikawa H, Ohki M, Joetham A, Gervy P, Chumakov I, Patterson D. YAC analysis and minimal tiling path construction for chromosome 21q. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1995;21:399–414. doi: 10.1007/BF02310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway HJ, Shur BD. Mammary gland morphogenesis is inhibited in transgenic mice that overexpress cell surface beta1,4-galactosyltransferase. Development. 1996;122:2859–2872. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D, Fisher EMC. Down syndrome genetics—Unravelling a multifactorial disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1411–1416. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.supplement_1.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoheisel JD, Maier E, Mott R, McCarthy L, Grigoriev AV, Schalkwyk LC, Nizetic D, Francis F, Lehrach H. High resolution cosmid and P1 maps spanning the 14 Mb genome of the fission yeast S. pombe. Cell. 1993;73:109–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90164-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horisberger MA, Wathelet M, Szpirer J, Szpirer C, Islam Q, Levan G, Huez G, Content J. cDNA cloning and assignment to chromosome 21 of IFI-78K gene, the human equivalent of murine Mx gene. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1988;14:123–131. doi: 10.1007/BF01534397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert RS, Korenberg JR. PCP4 maps between D21S345 and P31P10SP6 on chromosome 21q22.2 → q22.3. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;78:44–45. doi: 10.1159/000134623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert RS, Mitchell S, Chen XN, Ekmekji K, Gadomski C, Sun Z, Noya D, Kim UJ, Chen C, Shizuya H, et al. BAC and PAC contigs covering 3.5 Mb of the Down syndrome congenital heart disease region between D21S55 and MX1 on chromosome 21. Genomics. 1997;41:218–226. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Shimizu K, Saito A, Wang DN, Oliva R, Kobayashi H, Kaneko Y, Miyoshi H, Smith CL, Cantor CR, et al. Long-distance restriction mapping of the proximal long arm of human chromosome 21 with Not I linking clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:23–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou PA, Amemiya CT, Garnes J, Kroisel PM, Shizuya H, Chen C, Batzer MA, de Jong PJ. A new bacteriophage P1-derived vector for the propagation of large human DNA fragments. Nature Genet. 1994;6:84–89. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenberg JR, Bradley C, Disteche CM. Down syndrome: Molecular mapping of the congenital heart disease and duodenal stenosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50:294–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenberg JR, Chen XN, Schipper R, Sun Z, Gonsky R, Gerwehr S, Carpenter N, Daumer C, Dignan P, Disteche C, et al. Down syndrome phenotypes: The consequences of chromosomal imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:4997–5001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn B, Sedlacek Z, Manca A, Kioschis P, Konecki D, Lehrach H, Poustka A. A strategy for the selection of transcribed sequences in the Xq28 region. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:235–242. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.4.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer P, Meyer NC, Prass CE, Starnes SM, Wolff RK, Gnirke A. Clone-contig and STS maps of the hereditary hemochromatosis region on human chromosome 6p21.3-p22. Genome Res. 1997;7:457–470. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier E, Crollius HR, Lehrach H. Hybridisation techniques on gridded high density DNA and in situ colony filters based on fluorescence detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3423–3424. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.16.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mara MA, Kucaba TA, Dietrich NL, Green ED, Browstein B, Wilson RK, Mc Donald KM, LaDeana WH, McPherson JD, Waterston RH. High thoughput fingerprinting analysis of large-insert clones. Genome Res. 1997;7:1072–1084. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott R, Grigoriev A, Maier E, Hoheisel J, Lehrach H. Algorithms and software tools for ordering clone libraries: Application to the mapping of the genome of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1965–1974. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.8.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederfuehr A, Hummerich H, Gawin B, Boyle S, Little PFR, Gessler M. A sequence-ready 3 Mb PAC contig covering 16 breakpoints of the Wilm’s Tumor/Aniridia region of human chromosome 11p13. Genomics. 1998;53:155–163. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizetic D, Zehetner G, Monaco AP, Gellen L, Young BD, Lehrach H. Construction, arraying, and high-density screening of large insert libraries of human chromosomes X and 21: Their potential use as reference libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:3233–3237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizetic D, Gellen L, Hamvas RM, Mott R, Grigoriev A, Vatcheva R, Zehetner G, Yaspo ML, Dutriaux A, Lopes C, et al. An integrated YAC-overlap and “cosmid-pocket” map of the human chromosome 21. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:759–770. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.5.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira M, Ichikawa H, Suzuki E, Iwaki M, Suzuki K, Saitoohara F, Ikeuchi T, Chumakov I, Tanahashi H, Tashiro K, et al. A 1.6-Mb p1-based physical map of the down syndrome region on chromosome 21. Genomics. 1996;33:65–74. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira M, Seki N, Nagase T, Suzuki E, Nomura N, Ohara O, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Eki T, Murakami Y, et al. Gene identification in 1.6-Mb region of the Down syndrome region on chromosome 21. Genome Res. 1997;7:47–58. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoegawa K, Susukida R, Okano S, Kudoh J, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Dejong PJ, Groet J, Ives J, Lehrach H, et al. An integrated map with cosmid/pac contigs of a 4-Mb Down syndrome critical region. Genomics. 1996;32:375–387. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoloni-Giacobino A, Chen H, Peitsch MC, Rossier C, Antonarakis SE. Cloning of the TMPRSS2 gene, which encodes a novel serine protease with transmembrane, LDLRA, and SRCR domains and maps to 21q22.3. Genomics. 1997;44:309–320. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parimoo S, Patanjali SR, Shukla H, Chaplin DD, Weissman SM. cDNA selection: Efficient PCR approach for the selection of cDNAs encoded in large chromosomal DNA fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:9623–9627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen MB, Economou EP, Slaugenhaupt SA, Chakravarti A, Antonarakis SE. Linkage analysis of the human HMG14 gene on chromosome 21 using a GT dinucleotide repeat as polymorphic marker. Genomics. 1990;7:136–138. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani Z, Blouin JL, Creau-Goldberg N, Watkins PC, Mattei JF, Poissonnier M, Prieur M, Chettouh Z, Nicole A, Aurias A, et al. Critical role of the D21S55 region on chromosome 21 in the pathogenesis of Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:5958–5962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scartezzini P, Egeo A, Colella S, Fumagalli P, Arrigo P, Nizetic D, Taramelli R, Rasore-Quartino A. Cloning a new human gene from chromosome 21q22.3 encoding a glutamic acid-rich protein expressed in heart and skeletal muscle. Hum Genet. 1997;99:387–392. doi: 10.1007/s004390050377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler GD, Boguski MS, Stewart EA, Stein LD, Gyapay G, Rice K, White RE, Rodriguez-Tome P, Aggarwal A, Bajorek E, et al. Genome maps. The human transcript map. Science. 1996;274:547–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shur BD. Glycosyltransferases as cell adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:854–863. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90035-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund C, Longden I, Mott R. FPC: A system for building contigs from restriction fingerprinted clones. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:523–535. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeda E, Hou DX, Osoegawa K, Atsuchi Y, Yamagata T, Shimokawa T, Kishida H, Soeda E, Okano S, Chumakov I, et al. Cosmid assembly and anchoring to human chromosome 21. Genomics. 1995;25:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Mallett F, Durbin R, Horsnell T. Image analysis of restriction enzyme fingerprint autoradiograms. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:101–106. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Taboada JM, Sanz S, Egeo A, Scartezzini P, Oliva R. Identification and characterization of a new gene from human chromosome 21 between markers D21S343 and D21S268 encoding a leucine-rich protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:547–554. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DC, Boyle A, Haaf T. Fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques. Metaphase chromosomes, interphase nuclei, and extended chromatin fibers. In: Verma RS, Babu A, editors. Human chromosomes. Principles and techniques. New York, NY: MacGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 184–192. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa K, Haendel MA, Hubert R, Chen X-N, Lyons GE, Korenberg JR. DSCAM: A novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily maps in a Down syndrome region and is involved in the development of the nervous system. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:227–237. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaspo ML, Gellen L, Mott R, Korn B, Nizetic D, Poustka AM, Lehrach H. Model for a transcript map of human chromosome 21—Isolation of new coding sequences from exon and enriched cDNA libraries. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1291–1304. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.8.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]