Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the incidence and predictors of initiating methamphetamine injection among a cohort of injection drug users (IDU). We conducted a longitudinal analysis of IDU participating in a prospective study between June 2001 and May 2008 in Vancouver, Canada. IDU who had never reported injecting methamphetamine at the study's commencement were eligible. We used Cox proportional hazards models to identify the predictors of initiating methamphetamine injection. The outcome was time to first report of methamphetamine injection. Time-updated independent variables of interest included sociodemo-graphic characteristics, drug use patterns, and social, economic and environmental factors. Of 1317 eligible individuals, the median age was 39.9 and 522 (39.6%) were female. At the study's conclusion, 200 (15.2%) participants had initiated injecting methamphetamine (incidence density: 4.3 per 100 person-years). In multivariate analysis, age (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 0.96 per year older, 95%CI: 0.95–0.98), female sex (aHR: 0.58, 95%CI: 0.41–0.82), sexual abuse (aHR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.18–2.23), using drugs in Vancouver's drug scene epicentre (aHR: 2.15 95%CI: 1.49–3.10), homelessness (aHR: 1.43, 95%CI: 1.01–2.04), non-injection crack cocaine use (aHR: 2.06, 95%CI: 1.36–3.14), and non-injection methamphetamine use (aHR: 3.69, 95%CI: 2.03–6.70) were associated with initiating methamphetamine injection. We observed a high incidence of methamphetamine initiation, particularly among young IDU, stimulant users, homeless individuals, and those involved in the city's open drug scene. These data should be useful for the development of a broad set of interventions aimed at reducing initiation into methamphetamine injection among IDU.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, Injection drug use, Risk behavior, Initiation, HIV

Introduction

The use of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) including methamphetamines (MA) is a growing global health problem (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2009). ATS now rank second only to cannabis as the most common illicit drugs used worldwide, representing approximately 34 million users (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008). In North America, household surveys indicate that past year prevalence of MA use is approximately 0.3%–0.8% (Maxwell & Rutkowski, 2008). MA use and dependence are generally more common among young people (Iritani et al., 2007; Springer et al., 2007), homeless and marginally housed persons (Das-Douglas et al., 2008), and men who have sex with men (MSM) (Reback et al., 2008; Shoptaw & Reback, 2007). Less is known about the use of MA among people who inject drugs (IDU), although its use is particularly common among subpopulations of young IDU (Inglez-Dias et al., 2008) and MSM-IDU (Ibañez et al., 2005; Kral et al., 2005).

Chronic MA use has been associated with various physical and psychological harms (Buxton & Dove, 2008; Darke et al., 2008). The literature demonstrating a link between MA use and high-risk sexual behavior among MSM is substantial (Halkitis et al., 2001; Prestage et al., 2007; Semple et al., 2002), with several studies showing associations between MA use and HIV seroconversion (Buchacz et al., 2005; Plankey et al., 2007). A growing literature has demonstrated how injecting MA (versus non-injection modes of consumption) is associated with more severe symptoms of dependence and a greater number of health and social problems (McKetin et al., 2008; Semple et al., 2004). Evidence suggests that among IDU, transitioning to MA use increases HIV risk and has other important negative health implications. For example, compared to persons who inject other drugs, MA injectors are more likely to report sexual risk behaviors including sex work and unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse (Lorvick et al., 2006; Molitor et al., 1999). Furthermore, IDU who inject MA are more likely to engage in injection-related risk behavior including syringe sharing (Fairbairn et al., 2007), experience non-fatal overdose (Fairbairn et al., 2008), and in some settings, test positive for HIV (Buavirat et al., 2003). A recent systematic review also concluded that MA injectors experience an increased risk of mortality compared to other IDU (Singleton et al., 2009).

Given the adverse health outcomes noted above, interventions to prevent transitions to injecting MA should be a public health priority. However, few studies have been conducted to examine MA initiation among IDU and thus little evidence base exists to inform the development of prevention strategies. Limited evidence indicates that the majority of MA users consume other drugs prior to the initiation of use (Brecht et al., 2007). Qualitative work suggests that social factors play an important role in MA initiation; for example, several studies have found that sex partners and friends often offer MA to new users and prepare the drug for administration (Sheridan et al., 2009; Sherman et al., 2008). Very little research has examined transitions to MA injection, although coping style and sensation seeking are often given as primary motivations for initiation among younger MA injectors, while substitution for other drugs is more commonly reported among older IDU (Brecht et al., 2007; Nakamura et al., 2009). In response to the lack of evidence to inform effective prevention interventions, we conducted this study to determine the incidence of initiating MA injection and to examine the individual, social, environmental, and economic predictors of initiation among a prospective cohort of adult IDU.

Methods

The Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) is an ongoing open prospective cohort of adult IDU in Vancouver, Canada. Recruitment occurred through self-referral, word of mouth, and street outreach. Persons were eligible to participate in the study if she/he had injected drugs at least once in the previous 6 months, were greater than 14 years of age, resided in the greater Vancouver region, and provided informed consent. At baseline and semi-annually, participants completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire eliciting sociodemographic data as well as information pertaining to drug use patterns, risk behaviors, and health care utilization. Nurses collected blood samples for HIV and hepatitis C serology and also provided basic medical care and referrals to appropriate health care services. Participants received $20 for each study visit. Other recruitment and follow-up methods have been published elsewhere (Tyndall et al., 2003). The study has been approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

All participants who completed a baseline survey and at least one interview during the study period (June 2001 to May 2008) were eligible for inclusion. We constructed a study sample of MA injection-naïve individuals by excluding all participants who reported ever injecting MA at first study visit. The outcome of interest was ascertained by examining responses to the question, “In the last 6 months, which of the following drugs did you inject? We defined an event as the first instance of answering “amphetamine (e.g., speed),”, “methamphetamine,”,or “crystal meth.”

Rhodes’ risk environment framework (2002) was used to inform the selection of potential predictors of MA injection initiation. In accordance with this framework, we hypothesized that a broad set of individual, social, environmental, and economic factors act to increase the likelihood of transitions in drug use and subsequent risk behavior. We also included as potential confounders sociodemographic and other individual characteristics that have been found in previous literature to be associated with MA initiation and use (Brecht et al., 2004; Hayatbakhsh et al., 2009; Inglez-Dias et al., 2008). We included variables such as age (per year older), sex (female vs. male), sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual [LGBT] vs. heterosexual), age at first injection (per year older), and childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Due to the small number of individuals representing ethnic minorities in the sample, we dichotomized ethnicity as Caucasian (white) vs. other. We also included drug use variables, including non-injection crack cocaine use, injection heroin use, injection cocaine use, and non-injection methamphetamine use. Social, economic, and environmental variables considered included: relationship status (married or common law vs. single or casually dating); syringe sharing; injecting with a sex partner or friends, respectively; current enrolment in a methadone maintenance therapy program; homelessness; buying or using drugs in the downtown eastside (DTES) area of Vancouver (i.e., the city's open drug scene epicentre), respectively; currently having an area restriction or outstanding warrant; and injecting drugs while incarcerated (e.g., detention, prison, or jail). Unless otherwise indicated, all variables refer to the 6-month period preceding the date of the interview.

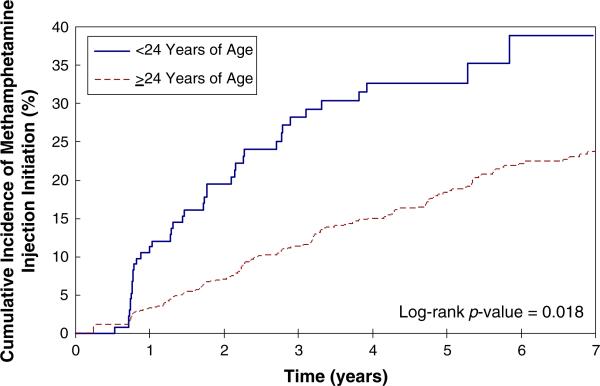

We compared the sociodemographic characteristics of those who initiated MA injection versus those who did not using the Pearson chi-square test and the Wilcoxon rank sum test. We then used the Kaplan-Meier method to generate the survival function and cumulative incidence of MA injection initiation over the study period. Based on previous research from our setting demonstrating increased rates of MA use among street-involved youth (Wood et al., 2008), we stratified the survival function by age at baseline (i.e., <24 versus ≥24). The time to initiating MA injection was estimated by taking the midpoint between the date of the first interview during which MA injection was reported and the preceding interview in which the participant was MA-injection naïve. To examine changes in the values of the explanatory variables over time, Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate the unadjusted hazard ratio for each variable. We used a lagged method to estimate the association between each independent variable and the outcome of interest. Specifically, to avoid associations attributable to reverse causation, the information recorded at the last follow-up prior to the estimated date of MA injection initiation was used for these analyses.

Since the primary objective of this study was to determine the set of individual, social, environmental, and economic factors which best predicted MA injection initiation, we chose to construct an explanatory multivariate model. A modified backward stepwise regression was used to select covariates based on two criteria: the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and p-values (Harrell, 2001). Lower AIC values indicate a better overall fit and lower p-values indicate higher variable significance. Starting with a full model containing all candidate variables, covariates were removed sequentially in order of decreasing p-values. At each step, the p-values of each variable and the overall AIC were recorded, with the final model having the lowest AIC. This model building procedure has been justified elsewhere (Lima et al., 2008). Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and all p-values are two-sided.

Results

Between June 2001 and May 2008, 1,878 participants completed a baseline and at least one follow-up interview and were eligible for this analysis. We excluded 541 (28.8%) individuals who reported injecting MA prior to the beginning of the study period, as well as 20 (1.5%) for whom MA use data were not available; therefore, 1317 MA-injection naïve participants were included in the final study sample. Participants who had already initiated and were thus excluded did not differ with respect to age but were more likely to be male and of Caucasian ethnicity (both p<0.001). The median age at first interview during the study period was 39.9 (IQR: 32.2–46.1), 522 (39.6%) were female, and the majority (n = 716, 54.5%) were of Caucasian ethnicity. Detailed sociodemographic information of the study sample is provided in Table 1. To investigate potential loss to follow up bias, we compared the sociodemographic characteristics of the 177 (13.4%) participants who never returned for follow-up with those who remained in the study. Participants lost to follow up did not vary with respect to age (p=0.809), sex (p=0.493), ethnicity (p=0.807), sexual abuse (p=0.993), or baseline crack use (p=0.396) and non-injection MA use (p=0.253). However, those lost to follow-up were more likely be homeless at baseline (26.7% vs. 19.3%, p=0.023).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of injection drug users who did and who did not initiate methamphetamine injection, 2001–2008 (n = 1317)

| Characteristic | Initiated MA Injection n=200 | Did Not Initiate MA Injection n=1117 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age† (median, IQR) | 36 (28–43) | 40 (33–46) | <0.001 |

| Age of First Injection (median, IQR) | 18 (15–23) | 19 (16–25) | 0.002 |

| Sex (n, %) | |||

| Female | 75 (37.5) | 447 (40.0) | 0.503 |

| Male | 125 (62.5) | 670 (60.0) | |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | |||

| Caucasian | 114 (57.0) | 602 (53.9) | 0.308 |

| Aboriginal* | 74 (37.0) | 394 (35.3) | |

| Asian | 5 (2.5) | 52 (4.7) | |

| Black | 5 (2.5) | 35 (3.1) | |

| Other | 2 (1.0) | 34 (3.0) | |

| Sexual Orientation (n, %) | |||

| LGBTa | 16 (9.2) | 81 (10.2) | 0.678 |

| Heterosexual | 158 (90.8) | 710 (89.8) |

age at first interview during study period

Aboriginal includes self-identified First Nation, Inuit, or Métis ancestry

LGBT=lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual

During the 7-year study period, eligible participants contributed 4,638 person-years of follow-up over 8,955 interviews. Thus, the average amount of time between follow-up interviews was 6.2 months. In total, 200 individuals reported initiating MA injection, resulting in an overall incidence density of 4.3 per 100 person-years (95%CI: 3.7–4.9 per 100 person-years). The Kaplan-Meier curve and cumulative incidence of MA injection initiation stratified by age at study entry are shown in Fig. 1. Among young injectors (i.e., less than 24 years of age), the cumulative incidence of MA injection reached almost 40% over the 7-year study period.

Fig. 1.

Younger age is associated with methamphetamine injection initiation among a cohort of injection drug users, 2001–2008 (n=1317)

The results of the Cox proportional hazards analyses are shown in Table 2. The results of the bivariate analyses are shown in the first two columns, and all variables retained in the final multivariate model are displayed in the last two columns of Table 2. Factors that remained significant in multivariate analysis and were positively associated with an increased hazard of MA injection initiation included: CSA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=1.63, 95%CI: 1.18–2.23, p=0.004), using drugs in the DTES (aHR=2.15, 95% CI: 1.49–3.10, p<0.001), homelessness (aHR=1.43, 95% CI: 1.01–2.04, p=0.047), non-injection crack use (aHR=2.06, 95%CI: 1.36–3.14, p=0.001) and non-injection MA use (aHR=3.69, 95%CI: 2.03–6.70, p<0.001). Older age (aHR=0.96 per year, 95%CI: 0.95–0.98, p<0.001) and female sex (AOR=0.58, 95%CI: 0.41–0.82, p=0.002) were protective for MA injection initiation. We note that while gender was not associated with initiation in bivariate analysis, the adjusted estimate was highly significant. Further investigation revealed that the protective effect of female gender not seen in bivariate analysis was due to the higher prevalence of CSA among women.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards model of time to initiating methamphetamine injection among a cohort of injection drug users (n = 1317)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted HR* (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per year older) | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.86 (0.64–1.14) | 0.291 | 0.58 (0.41–0.82) | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian vs. other) | 1.22 (0.92–1.61) | 0.173 | ||

| Relationship Status (married vs. single/dating) | 0.63 (0.42–0.93) | 0.019 | ||

| Sexual Orientation (LGBTa vs. heterosexual) | 0.86 (0.52–1.44) | 0.576 | ||

| Sexual Abuse‡ (yes vs. no) | 1.44 (1.08–1.90) | 0.012 | 1.63 (1.18–2.23) | 0.004 |

| Age of First Injection (per year older) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.016 | ||

| Buy Drugs in DTESc† (yes vs. no) | 2.40 (1.71–3.36) | <0.001 | ||

| Use Drugs in DTESc† (yes vs. no) | 2.78 (1.97–3.92) | <0.001 | 2.15 (1.49–3.10) | <0.001 |

| Homeless† (yes vs. no) | 2.34 (1.68–3.25) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.01–2.04) | 0.047 |

| Non-injection Crack Use† (yes vs. no) | 3.14 (2.11–4.67) | <0.001 | 2.06 (1.36–3.14) | 0.001 |

| Non-injection MAb Use† (yes vs. no) | 4.54 (2.52–8.16) | <0.001 | 3.69 (2.03–6.70) | <0.001 |

| Injection Heroin Use† (yes vs. no) | 2.15 (1.59–2.89) | <0.001 | ||

| Injection Cocaine Use† (yes vs. no) | 1.71 (1.24–2.35) | 0.001 | ||

| Inject with a Sex Partner† (yes vs. no) | 1.17 (0.77–1.76) | 0.463 | ||

| Inject with a Friend† (yes vs. no) | 1.82 (1.35–2.44) | <0.001 | ||

| Syringe Sharing† (yes vs. no) | 1.75 (1.07–2.85) | 0.025 | ||

| Warrant or Area Restriction¶ (yes vs. no) | 2.02 (1.35–3.00) | 0.001 | ||

| Methadone Maintenance Therapy¶ (yes vs. no) | 0.89 (0.66–1.21) | 0.463 | ||

| Inject while Incarcerated† (yes vs. no) | 3.93 (0.97–15.91) | 0.055 |

HR=Hazard Ratio

LGBT=lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual

MA=methamphetamine

DTES=Downtown Eastside

refers to activities in the past 6 months

refers to lifetime experiences

refers to current experiences.

Note: Variable selection based on AIC and type III p-values as described in (Lima et al., 2008).

As a sub-analysis, we sought to determine whether a different model-building protocol other than an AIC-based approach significantly altered the interpretation of our results. To do so, we fit a multivariate model consisting of all variables significant at p<0.05 in bivariate analyses. The two modeling strategies produced the same set of predictors (data not shown), thus suggesting that the results displayed in Table 2 are robust and not an artifact of predictor selection procedure.

Discussion

The present study revealed a high incidence of MA injection initiation, particularly among young IDU, stimulant users, the homeless, and among those involved in the city's open drug scene. These results indicate that a variety of individual, social, and environmental factors increase the likelihood of initiating MA use among established injectors, and suggest that a broad set of interventions based on a risk environment framework are required to prevent MA injection initiation and resultant harms.

This analysis demonstrates that several individual-level factors were independently associated with MA injection initiation among a cohort of adult IDU. For example, our results support previous research showing that young people are at high risk of MA injection initiation (Wood et al., 2008); therefore, young IDU should be a major focus of interventions that seek to prevent MA injection initiation. However, given that many participants initiated MA injection relatively late in their drug use careers, we argue that preventive interventions should also include strategies for older IDU in addition to programs targeted to younger populations and new injectors. Our finding that childhood sexual abuse was independently associated with MA injection initiation is not surprising given previous research demonstrating a high prevalence of CSA among MA treatment samples (Messina et al., 2008) and the existence of a dose-response relationship between frequency of CSA and likelihood of MA initiation in young adulthood (Hayatbakhsh et al., 2009). Although more research is required to establish the causal relationship between CSA and MA use, one possible explanation is that individuals with psychopathology arising from traumatic childhood experiences gravitate towards MA use as a coping strategy and form of self-medication (Halkitis & Shrem, 2006; Jaffe et al., 2005). CSA has also been shown to predict engagement in other adverse health behaviors including injection drug use initiation and sex work (Ompad et al., 2005; Stoltz et al., 2007); therefore, tailored and targeted programs that provide support and services to drug users who have experienced CSA are recommended.

Transitions from non-injection to injection heroin use have been relatively well-described (Des Jarlais et al., 2007; Neaigus et al., 2001, 2006); furthermore, extensive poly-drug use (including the concurrent use of amphetamine-type substances) and transitions to MA injection have also been observed among heroin users (Darke et al., 1999). We found that the non-injection use of MA was a strong and independent predictor of initiating MA injection, which supports previous studies demonstrating that transitions from non-injection to injection modes of MA consumption are common (Darke et al., 1994; Wood et al., 2008). Crack cocaine use was also found to predict MA injection initiation, which complements previous research demonstrating that crack smoking is a major predictor of initiation into injection drug use among youth (Fuller et al., 2001; Roy et al., 2003). Preliminary work also suggests that MA use is less persistent and has shorter periods of regular use over the life course as compared to heroin and cocaine (Hser et al., 2008). Further research is required to fully elucidate the typologies and trajectories of MA use in this setting.

Macro-level factors including drug market conditions are also believed to play an important role in drug use transitions (Des Jarlais et al., 2007). For example, although precursor regulations in the United States have resulted in substantial but transient reductions in MA purity and MA-related hospital admissions (Cunningham & Liu, 2003), a recently published study examining the effect of Canadian MA precursor regulations suggested that these policies were associated with increases in MA-related hospital admissions (Callaghan et al., 2009). Clearly, conventional supply reduction strategies, particularly those operating in the absence of other “demand reduction” interventions, have failed to reduce MA supply and use in Canada. It is for these reasons that a comprehensive approach, including programs that seek to reduce the demand for MA, have been strongly endorsed by organizations including the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2009).

Consistent with the risk environment framework, social and environmental factors that facilitate exposure to broader drug use scenes are also found to predict MA injection initiation. For example, we observed a strong relationship between involvement in the city's open drug scene and an increased incidence of MA injection. Further research is required to investigate the impact of these environments on drug use initiation and transitions; however, a recent network analysis of IDU living in Winnipeg, Canada identified a strong relationship between a higher connectedness to communal injection drug use settings and HIV risk behavior and polydrug use (Wylie et al., 2007). It may be that an open drug scene represents one such setting in which individuals are more likely to be introduced to novel drugs and modes of use. Future studies should investigate how interventions that alter or prevent exposure to open drug scenes mitigate the risk of initiating MA injection. For example, supervised injecting facilities have been shown to be effective micro-environmental interventions that modify the drug using environment and thus reduce risk behavior and other drug-related harms (Kerr et al., 2007). Finally, our finding that homelessness was independently associated with MA injection initiation supports other studies demonstrating a strong link between unstable housing status and engagement in HIV risk behaviour among IDU (Coady et al., 2007;Corneil et al., 2006).

Although increased resources are required to reduce the risks associated with injection drug use broadly, the results of this study have important implications for interventions which aim to prevent transitions to MA injection and avert MA-specific risks and harms. Given that factors both endogenous (e.g., age) and exogenous (e.g., involvement in open drug scenes) to the individual were independently associated with initiating MA injection, we argue that comprehensive programs that address a broad set of individual, social, structural, and environmental factors are required to prevent MA initiation among IDU. Since limited evidence exists to suggest the long-term effectiveness of supply reduction strategies (Borders et al., 2008; Callaghan et al., 2009) alternative interventions that address economic and social inequities are recommended. A growing literature has demonstrated that structural interventions based on a risk environment approach effectively reduce HIV risk among marginalized populations (Blankenship et al., 2006; Des Jarlais, 2000). We argue that a similar framework may be equally appropriate for implementing programs that aim to prevent MA injection initiation. For example, the expansion of stable and low-threshold housing programs for active drug users has been posited as a highly effective structural HIV prevention strategy (Shubert & Bernstine, 2007). Our results suggest that low-threshold housing may also prevent transitions to other modes and types of drug use by way of reducing exposure to chronic homelessness and open drug scenes among substance-using populations. We also point to research demonstrating that efficacious treatment modalities are available for patients with MA dependence (Hser et al., 2005; Rawson et al., 2004). Although psychosocial approaches are the mainstay of MA treatment, some substitution therapies are promising (Rose & Grant, 2008). While further research in this area is needed, the immediate expansion of evidence-based treatment for MA dependence among IDU populations as a means of preventing the transition to MA injection should be a public health priority.

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted. We were unable to obtain a random sample of injectors; therefore, the findings cannot necessarily be generalized to the entire IDU community or to other populations. However, we note that the sociodemographic characteristics of our sample are similar to those of other studies conducted in British Columbia (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2006). Furthermore, the geographic patterns of MA production and availability vary across North America (Maxwell & Rutkowski, 2008). In this manner, the observed incidence and predictors of MA initiation in this study may not be representative of other urban centers in North America or elsewhere. The study is also susceptible to recall bias and socially desirable reporting, although we have no reason to believe that the magnitude of these biases would differ between MA initiates and non-initiates. Since a question ascertaining lifetime history of MA injecting was not added until the second round of baseline interviews, we were not able to obtain this information for 268 (14.3%) participants. However, since methamphetamines were uncommon in Vancouver prior to 2001 (Buxton, 2005), few of these individuals would have initiated MA injecting before enrolment; thus, we expect the magnitude of this bias to be acceptably small. Finally, as in other survival analyses of observational data, noninformative censoring may have biased the results. However, we did not observe any sociodemographic differences between those lost to follow-up and those who remained in the study.

In summary, we observed a high incidence of methamphetamine injection initiation among a cohort of established injectors. An important limitation of many previous studies investigating the relationship between MA use and HIV risk behavior among IDU is the cross-sectional nature of the analyses, precluding conclusions regarding temporal relationships. We report here a longitudinal analysis demonstrating that several factors amenable to public health intervention preceded the initiation of MA injection. Given the risks and harms associated with MA use among IDU populations, the development, implementation and evaluation of these programs should be a public health priority.

Acknowledgements

We would particularly like to thank the VIDUS participants for their willingness to be included in the study as well as current and past VIDUS investigators and staff. We would specifically like to thank Dr. Thomas Patterson, Deborah Graham, Peter Vann, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) [R01 DA011591] and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [RAA-79918]. Thomas Kerr is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) and the CIHR. Brandon Marshall is supported by senior graduate trainee awards from MSFHR and CIHR.

Contributor Information

Brandon DL. Marshall, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6 School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, 2206 East Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z3.

Evan Wood, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6; Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6.

Jean A. Shoveller, School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, 2206 East Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z3

Jane A. Buxton, School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, 2206 East Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z3 Division of Epidemiology, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, 655 West 12th Ave, Vancouver, BC, Canada V5Z 4R4.

Julio SG. Montaner, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6 Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6.

Thomas Kerr, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6; Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, St. Paul's Hospital, 608-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 1Y6.

References

- Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders TF, Booth BM, Han X, Wright P, Leukefeld C, Falck RS, et al. Longitudinal changes in methamphetamine and cocaine use in untreated rural stimulant users: Racial differences and the impact of methamphetamine legislation. Addiction. 2008;103:800–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht ML, Greenwell L, Anglin MD. Substance use pathways to methamphetamine use among treated users. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht ML, O'Brien A, Von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Methamphetamine use behaviors and gender differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:89–106. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buavirat A, Page-Shafer K, van Griensven GJ, Mandel JS, Evans J, Chuaratanaphong J, et al. Risk of prevalent HIV infection associated with incarceration among injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand: Case-control study. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7384.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchacz K, McFarland W, Kellogg TA, Loeb L, Holmberg SD, Dilley J, et al. Amphetamine use is associated with increased HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS. 2005;19:1423–1424. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180794.27896.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton JA. Vancouver drug use epidemiology: Vancouver site report for the Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use. 2005 Retrieved from http://vancouver.ca/fourpillars/pdf/report_vancouver_2005.pdf.

- Buxton JA, Dove NA. The burden and management of crystal meth use. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;178:1537–1539. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Cunningham JK, Victor JC, Liu LM. Impact of Canadian federal methamphetamine precursor and essential chemical regulations on methamphetamine-related acute-care hospital admissions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coady MH, Latka MH, Thiede H, Golub ET, Ouellet L, Hudson SM, et al. Housing status and associated differences in HIV risk behaviors among young injection drug users (IDUs). AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:854–863. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneil TA, Kuyper LM, Shoveller JA, Hogg RS, Li K, Spittal PM, et al. Unstable housing, associated risk behaviour, and increased risk for HIV infection among injection drug users. Health & Place. 2006;12:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JK, Liu LM. Impacts of federal ephedrine and pseudoephedrine regulations on methamphetamine-related hospital admissions. Addiction. 2003;98:1229–1237. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Cohen J, Ross J, Hando J, Hall W. Transitions between routes of administration of regular amphetamine users. Addiction. 1994;89:1077–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb02784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:253–262. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, Ross J. Transitions between the injection of heroin and amphetamines. Addiction. 1999;94:1795–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das-Douglas M, Colfax G, Moss AR, Bangsberg DR, Hahn JA. Tripling of methamphetamine/amphetamine use among homeless and marginally housed persons, 1996-2003. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9249-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC. Structural interventions to reduce HIV transmission among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2000;14:S41–S46. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Perlis T, Hagan H, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, et al. The transition from injection to non-injection drug use: Long-term outcomes among heroin and cocaine users in New York City. Addiction. 2007;102:778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Buxton JA, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Increasing use and associated harms of crystal methamphetamine injection in a Canadian setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Wood E, Stoltz JA, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Crystal methamphetamine use associated with non-fatal overdose among a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver. Public Health. 2008;122:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(Suppl 1):136–145. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Stirratt MJ. A double epidemic: Crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41:17–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Shrem MT. Psychological differences between binge and chronic methamphetamine using gay and bisexual men. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Bor W, Williams GM. Predictors of young adults’ amphetamine use and disorders: A prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Evans E, Huang YC. Treatment outcomes among women and men methamphetamine abusers in California. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Huang D, Brecht ML, Li L, Evans E. Contrasting trajectories of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2008;27:13–21. doi: 10.1080/10550880802122554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez GE, Purcell DW, Stall R, Parsons JT, Gomez CA. Sexual risk, substance use, and psychological distress in HIV-positive gay and bisexual men who also inject drugs. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 1):S49–S55. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167351.00503.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglez-Dias A, Hahn JA, Lum PJ, Evans J, Davidson P, Page-Shafer K. Trends in methamphetamine use in young injection drug users in San Francisco from 1998 to 2004: The UFO Study. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:286–291. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iritani BJ, Hallfors DD, Bauer DJ. Crystal methamphetamine use among young adults in the USA. Addiction. 2007;102:1102–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe C, Bush KR, Straits-Troster K, Meredith C, Romwall L, Rosenbaum G, et al. A comparison of methamphetamine-dependent inpatients with and without childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptomatology. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2005;24:133–152. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n03_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Moore D, Wood E. A micro-environmental intervention to reduce the harms associated with drug-related overdose: Evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver's safer injection facility. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Lorvick J, Ciccarone D, Wenger L, Gee L, Martinez A, et al. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among men who have sex with men and inject drugs in San Francisco. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 1):i43–50. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Harrigan R, Murray M, Moore DM, Wood E, Hogg RS, et al. Differential impact of adherence on long-term treatment response among naive HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2008;22:2371–2380. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328315cdd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorvick J, Martinez A, Gee L, Kral AH. Sexual and injection risk among women who inject methamphetamine in San Francisco. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9039-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JC, Rutkowski BA. The prevalence of methamphetamine and amphetamine abuse in North America: A review of the indicators, 1992-2007. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:229–235. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKetin R, Ross J, Kelly E, Baker A, Lee N, Lubman DI, et al. Characteristics and harms associated with injecting versus smoking methamphetamine among methamphetamine treatment entrants. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:277–285. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Marinelli-Casey P, Hillhouse M, Rawson R, Hunter J, Ang A. Childhood adverse events and methamphetamine use among men and women. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;5:399–409. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitor F, Ruiz JD, Flynn N, Mikanda JN, Sun RK, Anderson R. Methamphetamine use and sexual and injection risk behaviors among out-of-treatment injection drug users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:475–493. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Patterson TL. Methamphetamine initiation among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1176–1184. doi: 10.1080/09540120902729999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neaigus A, Gyarmathy VA, Miller M, Frajzyngier VM, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC. Transitions to injecting drug use among noninjecting heroin users: Social network influence and individual susceptibility. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41:493–503. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000186391.49205.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neaigus A, Miller M, Friedman SR, Hagen DL, Sifaneck SJ, Ildefonso G, et al. Potential risk factors for the transition to injecting among non-injecting heroin users: A comparison of former injectors and never injectors. Addiction. 2001;96:847–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9668476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ompad DC, Ikeda RM, Shah N, Fuller CM, Bailey S, Morse E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and age at initiation of injection drug use. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:703–709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plankey MW, Ostrow DG, Stall R, Cox C, Li X, Peck JA, et al. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;45:85–92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestage G, Degenhardt L, Jin F, Grulich A, Imrie J, Kaldor J, et al. Predictors of frequent use of amphetamine type stimulants among HIV-negative gay men in Sydney, Australia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada I-Track: Enhanced surveillance of risk behaviours among people who inject drugs. 2006 Phase I Report, August 2006. Retrieved from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/i-track/sr-re-1/pdf/itrack06_e.pdf.

- Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, Dickow A, Frazier Y, Gallagher C, et al. A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2004;99:708–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback CJ, Shoptaw S, Grella CE. Methamphetamine use trends among street-recruited gay and bisexual males, from 1999 to 2007. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:874–879. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rose ME, Grant JE. Pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine dependence: A review of the pathophysiology of methamphetamine addiction and the theoretical basis and efficacy of pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;20:145–155. doi: 10.1080/10401230802177656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Cedras L, Blais L, Boivin JF. Drug injection among street youths in Montreal: Predictors of initiation. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80:92–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV + men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. A comparison of injection and non-injection methamphetamine-using HIV positive men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan J, Butler R, Wheeler A. Initiation into methamphetamine use: Qualitative findings from an exploration of first time use among a group of New Zealand users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2009;41:11–17. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2009.10400670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, German D, Sirirojn B, Thompson N, Aramrattana A, Celentano DD. Initiation of methamphetamine use among young Thai drug users: A qualitative study. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. Methamphetamine use and infectious disease-related behaviors in men who have sex with men: Implications for interventions. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):130–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubert V, Bernstine N. Moving from fact to policy: Housing is HIV prevention and health care. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S172–S181. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Zabransky T. Mortality among amphetamine users: A systematic review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer AE, Peters RJ, Shegog R, White DL, Kelder SH. Methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in U.S. high school students: Findings from a national risk behavior survey. Prevention Science. 2007;8:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz JA, Shannon K, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner JS, Wood E. Associations between childhood maltreatment and sex work in a cohort of drug-using youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P, Li K, Wood E, O'Shaughnessy MV, et al. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003;17:887–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Amphetamines and Ecstasy - 2008 Global ATS Assessment. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/ATS/Global-ATS-Assessment-2008-Web.pdf.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2009. 2009 Retrieved from www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/...2009/WDR2009_eng_web.pdf.

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Zhang R, Strathdee SA, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Circumstances of first crystal methamphetamine use and initiation of injection drug use among high-risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:270–276. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie JL, Shah L, Jolly A. Incorporating geographic settings into a social network analysis of injection drug use and bloodborne pathogen prevalence. Health & Place. 2007;13:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]