Abstract

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying voltage-dependent gating in voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs) has been a major effort over the last decades. In recent years, changes in the gating process have emerged as common denominators for several genetically determined channelopathies affecting heart rhythm (arrhythmias), neuronal excitability (epilepsy, pain), or skeletal muscle contraction (periodic paralysis). Moreover, gating changes appear as the main molecular mechanism by which several natural toxins from a variety of species affect ion channel function. In this work, we describe the pathophysiological and pharmacological relevance of the gating process in voltage-gated K+ channels encoded by the Kv7 gene family. After reviewing the current knowledge on the molecular mechanisms and on the structural models of voltage-dependent gating in VGICs, we describe the physiological relevance of these channels, with particular emphasis on those formed by Kv7.2–Kv7.5 subunits having a well-established role in controlling neuronal excitability in humans. In fact, genetically determined alterations in Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 genes are responsible for benign familial neonatal convulsions, a rare seizure disorder affecting newborns, and the pharmacological activation of Kv7.2/3 channels can exert antiepileptic activity in humans. Both mutation-triggered channel dysfunction and drug-induced channel activation can occur by impeding or facilitating, respectively, channel sensitivity to membrane voltage and can affect overlapping molecular sites within the voltage-sensing domain of these channels. Thus, understanding the molecular steps involved in voltage-sensing in Kv7 channels will allow to better define the pathogenesis of rare human epilepsy, and to design innovative pharmacological strategies for the treatment of epilepsies and, possibly, other human diseases characterized by neuronal hyperexcitability.

Keywords: potassium channels, Kv7 channels, epilepsy, neuronal excitability, voltage-sensing, retigabine, gating, anticonvulsant drugs

An Historical Introduction to Voltage-Dependent Gating

Signaling via changes in membrane potential and transmembrane ion fluxes is essential to life in all biological organisms, from bacteria to humans. Most cellular functions are properly executed only within a narrow range of intracellular and extracellular concentration for each ion species; thus, evolution has spent a tremendous effort in overcoming the thermodynamic cost required to translocate charges across low dielectric media such as the lipid membranes and selecting the appropriate means to perform such delicate regulation. Ion channel proteins, by allowing highly regulated ion fluxes across cellular compartments separated by a lipid membrane, provide a solution to this problem. Schematically speaking, two main properties characterize ion channel function: the first one is the gating mechanism, namely their ability to sense the appropriate stimulus, the other being selectivity, namely their capacity to discriminate the ion species allowed to permeate. These two properties, although conceptually separate, are clearly linked in the operation cycle of ion channels, as the structural rearrangement accompanying gating are tightly coupled to ion permeation (Hille, 2001).

In voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs), the third largest group of signal-transduction proteins (Wulff et al., 2009), the gating mechanism is triggered by transmembrane voltage changes. Differences of only a few millivolts can dramatically modify the opening probability of VGICs, leading to the massive ion fluxes responsible for electrical signaling in excitable cells; depending on the specific cell type involved, electrical signaling is then translated in mechanical force (as in muscle contraction or cell movement) or chemical signal generation (hormone and neurotransmitter release). Additional gating triggers for ion channels are changes in the chemical composition of the extracellular or intracellular environment (ligand-gated ion channels), in the mechanical force applied (mechanosensitive channels), or of the environmental temperature (temperature-sensitive channels). Noteworthy, such representation is overly schematic, as diverse gating mechanisms often synergize in ion channels under physiological or pathological conditions, as in Ca2+-dependent K+ channels, some of which are also sensitive to membrane potential changes, in voltage-gated channels also affected by the osmotic pressure, and in ligand-gated channels, also acting as temperature sensors.

In VGICs, it has long been hypothesized, much before their molecular architecture was defined, that movement of charged particles (termed “gating charges”) within the membrane electric field was responsible for voltage-dependent activation of the conductance (Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952). In the squid axon, gating current experiments allowed a direct measurement of gating charge translocation in the membrane dielectric field during voltage-sensing for voltage-gated Na+ (VGNCs; Armstrong and Bezanilla, 1973) and K+ (VGKCs; Bezanilla et al., 1982) channels.

Although these studies established the basic biophysical and theoretical principles underlying voltage-sensing in VGICs, a major breakthrough toward the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms involved came from the identification of the primary sequence of the first VGIC, namely the VGNCs from the electroplax of the Electrophorus electricus (Noda et al., 1984), soon followed by that for a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCCs) from rabbit skeletal muscle (Tanabe et al., 1987) and for a VGKCs channel from Drosophila (Papazian et al., 1987). These earlier studies revealed the existence of an amino acid stretch within the fourth putative transmembrane segment (S4), where from four to eight positively charged residues (K, lysines; R, arginines) were present at each third position, mostly separated by uncharged residues; such peculiar arrangement allowed to hypothesize that the charged elements located within the electric field along the transmembrane S4 segment represented the main gating charges of VGICs. In the following decade, extensive testing and refinement of this original hypothesis by a wide variety of experimental approaches, mainly including mutagenesis, fluorescence spectroscopy, and electrophysiology, confirmed the role of the S4 positive charges in voltage-sensing, and allowed to elaborate a more complex picture of the gating process which also involved negatively charged residues in neighboring segments, protein regions translating gating charge movement into pore opening, interacting lipids, cooperativity among different gating elements, and modulation by drugs and toxins (Bosmans and Swartz, 2010).

In the last years, mainly due to structural work on the voltage-sensing region of several VGKCs performed by Roderick MacKinnon and his group, some of the molecular intimacies of voltage-sensing have been uncovered. Although these achievements have definitively provided a clearer mechanistic view of this process, several controversies are yet to be resolved and gaps in our molecular understanding are waiting to be filled-in. Moreover, the last decade has witnessed an explosion of interest in genetically inherited diseases caused by mutations occurring in ion channel genes (channelopathies); these studies have revealed that phenotypically heterogeneous diseases affecting heart rhythm (arrhythmias), neuronal excitability (epilepsy, pain), or skeletal muscle contraction (periodic paralysis) have an altered gating process of the VGICs affected as a common denominator.

Molecular Architecture of Voltage-Dependent K+ Channels

Classification and overall structure

Among the VGIC extended super-family of genes, those encoding for K+ channels constitute more than half, with over 78 genes encoding for K+ channel subunits in humans (Wulff et al., 2009). According to primary sequence homology of their protein products and their ability to assemble into heteromeric channels, VGKCs can be divided in 12 subfamilies, from Kv1 to Kv12 in the official IUPHAR channel name terminology (Gutman et al., 2003; Harmar et al., 2009). VGKCs are important regulators of cellular electrical excitability; indeed, an increase in the membrane conductance for K+ ions causes, in most cases, membrane hyperpolarization and reduces excitability.

Most Kv channels assemble as tetramers of subunits, each corresponding to a single domain of VGNCs and Ca2+ channels (VGNCs and VGCCs, respectively). Each Kv channel subunit is characterized by the presence of six transmembrane segments (form S1 to S6) and intracellular N- and C-terminal regions of variable length which contain important regions controlling fast inactivation, tetramerization, association with accessory proteins, and post-translational regulation of the channels.

Within each subunit, helices S5 and S6 and their interconnecting loop form the conduction pore which contains the K+ selectivity filter and the internal gate localized at the C-terminal region of S6, while segments from S1 to S4 form the so-called voltage-sensing domains (VSD) arranged symmetrically around the pore.

The structural basis of permeation

Structural work performed on bacterial non-voltage-gated “inward rectifier” K+ (KIR) channels KcsA (Doyle et al., 1998), MthK (Jiang et al., 2002a,b), and KirBac1.1 (Kuo et al., 2003), whose membrane core of each subunit only contains the regions corresponding to the S5–S6 domain and the intervening linker, has provided a valuable structural model to explain the molecular mechanisms of ion permeation, selectivity, and pore opening/closing behavior. Structural work on a Kir chimera formed by joining the transmembrane portion of a bacterial Kir to the cytoplasmic portion of eukaryotic Kir3.1 (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002), have revealed further details on the pore structure in KIR channels, with particular reference to the presence of a long cytoplasmic pore (Nishida et al., 2007) and its voltage-dependent block by intracellular cations (Xu et al., 2009). Indeed, the comparison of structural data from the MthK channel trapped in the open conformation, and channels crystallized in the closed conformation (KcsA and KirBac1.1) revealed possible structural changes that underlie pore opening in K+ channels. In KcsA and Kirbac1.1 the second transmembrane helices (TM2), corresponding to the S6 transmembrane segments in Kv channels, are almost parallel to the membrane plane and form a four-helix bundle near the intracellular membrane surface that occludes the ion conduction pathway; by contrast, in open MthK channels, the TM2 helices are bent at a glycine residue, highly conserved in bacterial K+ channels and some eukaryotic Kv channels. This glycine residue has been proposed to serve as a gating hinge that allows TM2 to fluctuate between a closed and an opened conformation. However, this structure-based gating model, although appealing in its simplicity, does not entirely fit with the details of functional experiments in most VGKCs; to account for some of these discrepancies, it has been more recently proposed that a conserved PXP motif (where X is any amino acid), not present in bacterial K+ channels and located in S6 downstream of the glycine residue, acts as a flexible hinge that keeps the upper portion of S6 relatively still, but allows the lower half of S6 to move, opening the pore by swiveling the blocking residues away from the central axis (Webster et al., 2004). Differences in the magnitude of movement of the lower end of S6 would also explain the large conductance difference between eukaryotic and prokaryotic K+ channels; in fact, larger movements would be required to sustain the high single-channel conductance of the MthK channels (about 220 pS), whereas the smaller size of the pore formed at the PXP gating hinge in Kv1.1 channels would be responsible for their 10 times lower conductance (about 20 pS).

The structural basis of voltage-sensing

In Kv channels, pore opening is regulated by the VSD. The first crystal structure of a K+ channel containing a VSD was that of bacterial KvAP (Jiang et al., 2003a); soon after this landmark result, the crystal structures of the mammalian Kv1.2 channel was described (Long et al., 2005a,b, 2007). As previously mentioned, within each VSD, the S4 segment contains several (in most cases from 4 to 8) positively charged arginines (Rs) or lysine (Ks) residues. The first four of these residues are believed to be the most important voltage-sensing elements and their movement during voltage-sensing is thought to represent a major part of the gating charges giving rise to gating currents (Aggarwal and MacKinnon, 1996; Seoh et al., 1996). In Kv1.1 channels, the number of elementary charges per channel crossing the electric field is estimated to be about 13, corresponding to about three elementary charges per subunit (Schoppa et al., 1992). Positively charged amino acids in S4 are separated by 2–3 uncharged residues, so that the positive charges are mostly localized on the same side of an α-helix, and interact with highly conserved negatively charged residues in the S1–S3 region within the membrane, while the lipid head groups stabilize the interactions with charged residues located at the membrane surface (Schmidt et al., 2006; Long et al., 2007). In particular, negatively charged residues in S1 (E247), S2 (E283 and E293 in Shaker), and S3 (D316) seem to play a key role in the stabilization of positively charged residues in S4 (Delemotte et al., 2010), also contributing to gating charge movements (Seoh et al., 1996).

The VSD can be considered as an independent functional domain that can be transplanted onto other proteins to confer voltage sensitivity (Tombola et al., 2006); indeed, the voltage-sensing phosphatase from Ciona intestinalis (Ci-VSP; Murata et al., 2005) is formed by a VSD linked to a phosphatase: this protein directly translates changes in membrane potential into changes of phosphoinositides turnover. Moreover, the proton-selective channel Hv1 has been shown to be formed by subunits containing only an isolated VSD, without a canonical S5–S6 pore (Ramsey et al., 2006; Sasaki et al., 2006); this astonishing result provided definitive evidence for the ability of the VSD to also function as an ion conduction pathway in native channels, a result in line with previous mutagenesis experiments showing the existence of so-called gating-pore currents (ω-currents) flowing through the voltage sensors of VGKCs (Starace et al., 1997; Starace and Bezanilla, 2004; Tombola et al., 2005, 2007).

Coupling voltage-sensing to pore opening

Efficient coupling of the VSD movement to pore opening appears to involve the S4–S5 linker which, when the VSD is in the resting state, is believed to be positioned close to the internal end of S6, below the highly conserved PVP motif of the neighboring subunit in Shaker and similar eukaryotic Kv channels; as previously mentioned, this regions represents the gating hinge for pore opening. On the basis of these observations, it has been proposed that, upon membrane depolarization, S4 outward movement (see below), by pulling onto the S4–S5 linker, causes the bending of the S6 gating hinge to open the S6 intracellular helix bundle, leading to pore opening (Long et al., 2005a,b). A second contact interface between the S1 region of the VSD and the extracellular surface of the pore has been recently proposed to act as an anchor point for efficient transmission of VSD conformational changes to the pore's gate (Lee et al., 2009).

Molecular Models of VSD Movement During Gating

The structural and functional advancements briefly reviewed have converged onto the concept that charged and uncharged residues in the VSD act as crucial gating elements; however, the exact structural rearrangements within the VSD upon voltage-sensing are not completely understood. In particular, current controversies revolve around the extent and direction of these rearrangements with respect to the transmembrane electric field, their precise coordination in time among each other (Catterall, 2010), and the position of the field with respect to the membrane (Ahern and Horn, 2004; Bezanilla, 2008). In general terms, three main conceptual models have been proposed (Borjesson and Elinder, 2008):

The helical screw or sliding helix model was originally proposed soon after the first primary sequences of ion channel proteins were available, and following mutagenesis studies revealing that the first four Rs in S4 carry most of the gating charge (Aggarwal and MacKinnon, 1996; Seoh et al., 1996). In this model, under resting (hyperpolarized) conditions S4 Rs are drawn toward the intracellular side of the membrane by the electrostatic potential, and form ion pairs with negatively charged residues in neighboring S1, S2, and S3 segments. When the membrane is depolarized, the S4 helix rotates along its length (by 60°–180°) and, at the same time, translates along its axis by 5–15 Å to allow the transfer of the three arginine charges per subunit across the electric field (that is to say, the S4 moves outwardly by a length corresponding to about three α-helical turns). This model has been largely supported by the results from accessibility studies of cysteines positioned at various locations along the S4 segment to membrane impermeable reagents (cysteine accessibility method; Larsson et al., 1996; Yusaf et al., 1996); these experiments revealed that the top S4 arginines are only accessible to intracellularly applied reagents when the VSD occupies its resting position, but become accessible to extracellularly applied reagents upon VSD activation. Noteworthy, only a narrow region of S4 appears protected from cysteine-reacting compounds when the VSD is in its resting or activated configurations.

In this model, to allow outward movement of the gating charges, several ion pairs involving positively charged and negatively charged residues would be formed and rearranged in a stepwise fashion during VSD activation. These interactions would be also favored by the fact that the S4 segments assumes a 310 α-helical conformation, in which hydrogen bonding would be formed between the N-H group of an amino acid and the C = O group of the amino acid three (rather than four as in conventional α-helical conformations) earlier residues (Long et al., 2007; Khalili-Araghi et al., 2010); thus, it seems as the role of the neighboring negative charges is not only to reduce the energetic cost of moving the gating charges across the bilayer, but also to shape the S4 segment to achieve its optimal positioning in a partially stretched and unwinded configuration.

The transporter model, an evolved version of two previous models of charge translocation, the “rotation in place” (Cha et al., 1999) and the “moving orifice” (Yang et al., 1996), is mainly based on results from mutagenesis experiments (histidine- or cysteine-scanning mutagenesis), fluorescent resonance energy transfer, spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography. In fact, the previously mentioned results obtained with the cysteine accessibility technique suggest that most S4 arginines are easily accessible to intracellularly or extracellularly applied water-soluble reagents, arguing in favor of their location in water-filled protein crevices. The X-ray structures of Kv1.2 (Long et al., 2005a) and of a chimeric channel in which the voltage-sensor paddle (corresponding to the S3b–S4 region) of Kv2.1 was transferred into the Kv1.2 subunit (Long et al., 2007) provided structural support to this hypothesis. According to this model, during activation S4 would mainly undergo rotational movements without significant translational movements (2–4 Å); upon membrane depolarization, S4 arginines would move from a crevice in contact with the intracellular solution into another crevice in contact with the extracellular solution. A corollary to this model is the fact that the membrane electric field would be focused within a region of the protein of approximately 5–10 Å, considerably thinner than the lipid membrane (∼30Å). The resting and activated positions of the VSD would be stabilized by ionized hydrogen bonds between the S4 arginines and two negatively charged clusters: one facing the extracellular side of the membrane and provided by the S1 and S2 helices, and another closer to the intracellular membrane surface, involving the S2 and the S3a helices. These two clusters would be separated by a highly conserved phenylalanine residue positioned in the middle of S2 (the so-called “phenylalanine gap or cap”), which would therefore act as a gating charge transfer center across which the S4 segment rotates during activation (Tao et al., 2010). The existence of water-filled crevices in the VSD is also consistent with the notion that, under specific circumstances, gating-pore currents (ω-currents) can flow through the voltage sensors of VGKCs (Starace et al., 1997; Starace and Bezanilla, 2004; Tombola et al., 2005, 2007).

The paddle model is mainly based on the crystal structure of the bacterial channel KvAP (Jiang et al., 2003a,b). In this structure, the VSD was found to be positioned parallel to the intracellular side of the membrane, assuming a conformation likely representing the resting state of the sensor; however, the channel pore appeared to be in the open configuration. Despite such discrepancy, the model suggested that S4 and part of S3 (S3b) form an helical hairpin, or paddle, that freely moves by a large extent (15–20 Å) across the lipidic bilayer during each gating cycle. Avidin accessibility to biotin tethered to different VSD positions confirmed the notion that the paddle undergoes large movements within the membrane (Jiang et al., 2003b; Ruta et al., 2005). More recently, structural and functional data have led to the proposal that the highly conserved phenylalanine residue in S2 is close to R1 in the resting VSD configuration and to R5 in the active configuration; given that the distance between the α carbons of R1 and R5 is about 21 Å along and 18 Å perpendicular to the membrane, and assuming that the S2 segment is rather rigid and poorly mobile, these data would argue in favor of a large movement of the paddle relative to the rest of the VSD during activation (Tao et al., 2010). When comparing the structural data from KvAP with those of mammalian channels, some difference are evident, particularly regarding the tighter association of S3 with S4 possibly caused by the shorter length of the S3–S4 linker in the KvAP channel. Thus, the paddle model appears to specifically capture some features of KvAP gating, but appears by no means to be applicable to all VGKCs (Tombola et al., 2005). Moreover, it has also been pointed out that the paddle model appears incompatible with a number of experimental evidence obtained in other VGKCs, leading to the hypothesis that the KvAP structure may represent a non-native state of the channel, possibly resulting from distortions caused by the crystallization procedure (Catterall, 2010).

Voltage-Dependent K+ Channels of the Kv7 Subfamily

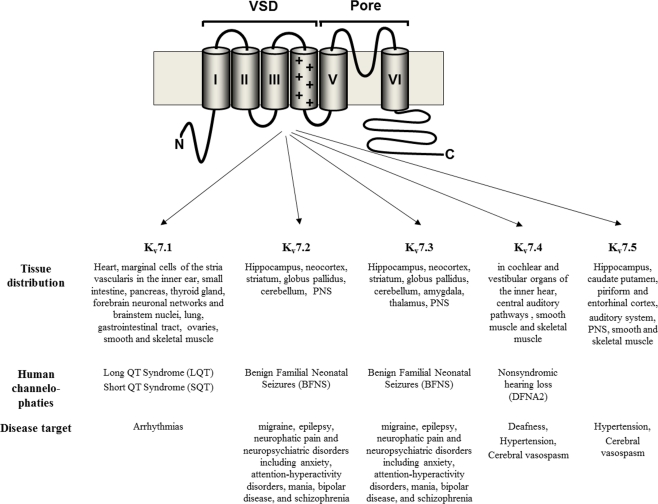

Among Kv channels, the Kv7 family encompasses five members (from Kv7.1 to Kv7.5), each showing a different tissue distribution and physiological role (Miceli et al., 2008a; Figure 1). Indeed, Kv7.1 is manly expressed in the heart, pancreas, thyroid gland, brain, gastrointestinal tract, portal vein, and the inner ear. In cardiac myocytes, in association with KCNE1, Kv7.1 underlies the slow component of IKs, a K+-selective current involved in the late phase of action potential repolarization. Kv7.2, Kv7.3, Kv7.4, and Kv7.5 show prevalently neuronal localization; homo- or hetero-tetrameric assembly of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits, with possible additional contribution from Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 subunits at specific neuronal sites, represents the molecular basis of the M-current (IKM), a slowly activating and deactivating K+ current highly regulated by Gq/11-coupled receptors (Delmas and Brown, 2005). IKM regulates membrane excitability in the sub-threshold range for action potential generation, acting as a brake for neuronal firing; indeed, reduction of this current is often sufficient to increase neuronal excitability. Kv7.4 subunits are mainly expressed in cochlear and vestibular organs of the inner hear, as well as in central auditory pathways (Kubisch et al., 1999); more recent work has revealed expression of Kv7.4 subunits also in skeletal muscle (Iannotti et al., 2010), as well as in visceral and vascular smooth muscle (Greenwood and Ohya, 2009). Kv7.5 expression, in addition to the brain, has been also detected in human adult skeletal muscle (Lerche et al., 2000; Schroeder et al., 2000), and, together with Kv7.1 and Kv7.4, in vascular smooth muscle cells (Yeung et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Kv7 channels structure, tissue distribution, human channelopathies, and disease target.

The pathophysiological importance of these channels is emphasized by the fact that mutations in four of the five Kv7 genes are associated to different hereditary channelopathies in humans. In particular, mutations in Kv7.1 have been found in families affected by arrhythmogenic diseases such as dominant (the Romano–Ward syndrome) and recessive (the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome) chromosome 11-linked form of the Long QT syndrome (Wang et al., 1996), and the short QT syndrome (Bellocq et al., 2004). More recently, single nucleotide polymorphisms in Kv7.1 have been suggested to confer susceptibility to type two diabetes (Unoki et al., 2008). Mutations in Kv7.4 underlie a rare form of deafness (DFNA2), characterized by symmetric, predominantly high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss that is slowly progressive across all frequencies (Kubisch et al., 1999).

Mutations in the genes encoding for Kv7.2 (Biervert et al., 1998; Singh et al., 1998) or Kv7.3 (Charlier et al., 1998) are responsible for benign familial neonatal seizures (BFNS), a rare autosomal-dominant idiopathic epilepsy of the newborn (Bellini et al., 2010). BFNS is characterized by the occurrence of focal, multifocal, or generalized unprovoked tonic–clonic convulsions starting around day 3 of post-natal life and spontaneously disappearing after few weeks or months (Plouin, 1994). Although neurocognitive development is normal in most BFNS-affected individuals, follow-up studies have revealed that seizures or other neurological or neuropsychiatric abnormalities can occur in up to 15% of the patients (Ronen et al., 1993; Dedek et al., 2001; Coppola et al., 2003; Wuttke et al., 2007). BFNS-causing mutations are 10 times more likely to be found in Kv7.2 than in Kv7.3; all Kv7.3 mutations described to date are missense, whereas Kv7.2 mutations consist of truncations, splice site defects, or missense, non-sense, and frame-shift mutations, as well as sub-microscopic deletions or duplications (Heron et al., 2007; Soldovieri et al., 2007a). Kv7.2 mutations have been also detected in sporadic cases of benign neonatal seizures (Sadewa et al., 2008; Ishii et al., 2009; Miceli et al., 2009a).

Gating Changes are Major Pathogenetic Mechanisms for BFNS

A mild decrease of IKM function appears sufficient to cause BFNS, and haploinsufficiency seems to be the primary pathogenetic mechanism for both familial and sporadic forms of the diseases. In Kv7.2, most BFNS-causing mutations are localized either in the large C-terminal domain, a critical region for subunit assembly and channel regulation by intracellular molecules, and in the VSD. Functional analysis of Kv7 channel subunits carrying mutations causing BFNS has revealed several mechanisms by which these genetic alterations impair IKM function (Soldovieri et al., 2007a). Some mutations drastically decrease channel subunit expression, while others affect the intracellular trafficking (Soldovieri et al., 2006) and polarized targeting of Kv7.2 subunits (Chung et al., 2006). Other mutations, instead, alter the function of Kv7.2 subunits normally inserted into the plasmamembrane; among these, changes in gating properties have been suggested to play a major role in BFNS pathogenesis (Dedek et al., 2001; Castaldo et al., 2002; Soldovieri et al., 2007b), a result consistent with these mutations affecting residues located within the VSD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Benign familial neonatal seizures-causing mutations localized in Kv7.2 VSD: overview of the available genetic, clinical, and functional data.

| Amino acid change | Localization | Additional clinical data (beside BFNS) | Functional effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.E119G | S1–S2 linker | Generalized clonic seizures | Slight rightward shift in current voltage dependence in the sub-threshold region; Slight decrease in current activation kinetics | Wuttke et al. (2008) |

| p.S122L | Febrile seizures in later life; seizures until 7 years | Rightward shift in current voltage dependence in the sub-threshold region; decrease in current activation kinetics | Hunter et al. (2006) | |

| p.A196V | S4 | – | Rightward shift in current voltage dependence; decrease in current activation kinetics; novel pre-pulse-dependence of current activation kinetics | Soldovieri et al. (2007b) |

| p.A196V;L197P | – | Rightward shift in current voltage-dependence; decrease in current activation kinetics | Soldovieri et al. (2007b), Moulard et al. (2001) | |

| p.R207W | Myokymia | Marked rightward shift in current voltage dependence; dramatic decrease in current activation kinetics | Dedek et al. (2001) | |

| p.R207Q | Myokymia (no BFNS) | Rightward shift in current voltage dependence; decrease in current activation kinetics | Wuttke et al. (2007) | |

| p.M208V | Generalized seizures between 4 and 7 years | Small decrease in maximal current; increased rate of channel deactivation | Singh et al. (2003) | |

| p.D212G | Rightward shift in current voltage dependence; increased rate of channel deactivation | Miceli et al. (2009a) | ||

| p.R213W | – | – | Sadewa et al. (2008) | |

| p.R214W | – | Slight rightward shift in current voltage dependence; no effect on maximal current amplitude | Miraglia del Giudice et al. (2000), Castaldo et al. (2002) | |

| p.H228Q | S4–S5 linker | – | – | Singh et al. (2003) |

The fact that IKM gating changes can be responsible for human epilepsies provides strong support for the hypothesis that this current is a crucial regulator of neuronal excitability in humans; to achieve such delicate functional role, a fine control of IKM gating properties within a precise range of membrane potential values is required. In general, small changes in the channels’ voltage dependence, particularly at sub-threshold voltages (between −60 and −30 mV), can profoundly affect neuronal excitability; it has been estimated that a 4-mV negative or positive shift of the conductance versus voltage (G/V curves) can increase or decrease, respectively, the current size by two-folds (Borjesson and Elinder, 2008). As a matter of fact, despite variability among expression systems and electrophysiological protocols used in different studies, quantitative analysis of the effects on IKM gating has revealed that even slight (∼5 mV) decreases in voltage sensitivity of the steady-state activation process of the macroscopic currents, as it occurs in the Kv7.2 mutants E119G (in the S1–S2 linker; Wuttke et al., 2008) and S122L (in the S2 segment; Hunter et al., 2006), is sufficient to cause BFNS. Gating changes are also a hallmark of the functional consequences of mutations affecting residues positioned within the S4 transmembrane segment. Among these, three BFNS-causing mutations involve positively charged residues: R207W (Wuttke et al., 2007), R213W (Sadewa et al., 2008), and R214W (Castaldo et al., 2002). These positions correspond to the third (R3), fifth (R5), and sixth (R6) positively charged residues along the Kv7.2 primary sequence; it is worth noticing that, similarly to all other Kv7 subunits, Kv7.2 lacks of the positively charged residue corresponding to R3 in Kv1 channels, which is instead replaced by a glutamine. These substitutions cause functional changes of different extent; while no functional data is yet available on the R5W substitution, neutralization of the charge at R3 (R207W) was associated with a marked reduction of channel voltage sensitivity; on the other hand, milder effects were observed with the R6 (R214W) substitution. These data, consistent with the previously discussed models in which gating charges corresponded to the first four S4 Rs, suggested that R3 in Kv7.2 (corresponding to R4 in Kv1.1) has a more central role in voltage-sensing when compared to R6; noteworthy, R6 appears the least-conserved of the six S4 Rs among VGKCs (Miceli et al., 2008b). Moreover, at the R3 position, very different functional effects were revealed when comparing the properties of the glutamine (Q, which has a size similar to R, but is missing the charge) versus tryptophan (W, a bulkier uncharged amino acid) substitution; in fact, Kv7.2 R3W channels displayed a more marked positive shift in the half-activation potential when compared to R3Q channels, together with a marked slowing in current activation kinetics; these data allowed to conclude that, in addition to charge, steric bulkiness also plays a relevant role at position R3; by contrast, at the R6 position, no significant functional difference was noted between homomeric channel carrying the R6Q or the R6W substitution.

In order to assess the contribution of each R residue in S4 to Kv7.2 channels voltage-sensing, neutral glutamines (Q) were introduced to substitute each R individually (Miceli et al., 2008b). The results obtained suggest that, in Kv7.2 channels, neutralization of the positive charges at the N-terminal end of S4 stabilized the activated state of the voltage sensor, whereas positive charge neutralization at the C-terminal end of S4 favored the resting conformation. Interesting, neutralization of R2 (R201) was sufficient to cause a complete loss of voltage dependence, suggesting that this R residue is indispensable to stabilize the resting configuration of the VSD in Kv7.2.

One striking structural characteristic of Kv7 channels is the presence of a negatively charged residue (D212) located between R4 and R5 in S4. Recently, a mutation affecting this residue has been identified in a sporadic case of BFNS (D212G; Miceli et al., 2009a). Electrophysiological results revealed that homomeric and heteromeric channels incorporating Kv7.2 subunits carrying the D212G mutation displayed a positive shift in their steady-state voltage dependence of activation, requiring larger depolarizations to become activated; these effects were not accompanied by significant changes in plasma membrane expression, selectivity for K+ over Na+ ions, and pharmacological blockade by TEA. Moreover, the quantitative effect of the mutation appeared linearly related to the number of mutant subunits incorporated into the channels. Kinetic analysis in homomeric channels formed by subunits carrying the D212G substitution revealed that the mutation failed to interfere with either the fast or the slow time constants of activation, or with their amplitude ratio, but rather increased the rate of channel closing, indicative of a marked stabilization of the closed state, an effect responsible for the decreased sensitivity to voltage of the steady-state activation process.

In addition to charged residues, hydrophobic residues in S4 are also known to be involved in voltage-dependent gating of VGKCs (Lopez et al., 1991; McCormack et al., 1991); noteworthy, the gating differences between Shaker (Kv1) and Shaw (Kv3) channels have been attributed to sequence differences with respect to S4 uncharged amino acids (Smith-Maxwell et al., 1998). Consistent with this, uncharged residues in S4 are also targets for BFNS-causing mutations (Moulard et al., 2001; Singh et al., 2003; Soldovieri et al., 2007b). Some intriguing features have been recently revealed upon investigation of the functional consequences of the A196V substitution (Soldovieri et al., 2007b), involving a residue located at the N-terminal end of the S4 and conserved among all Kv7 members except for Kv7.3. Electrophysiological analysis of the functional changes prompted the A196V mutation by macroscopic and single-channel current recordings, revealed that channels incorporating Kv7.2 A/V mutant subunits showed a decreased sensitivity to voltage. Intriguingly, the A196V mutation introduced an unusual dependence of the macroscopic current activation kinetics upon the pre-pulse voltage, showing an acceleration of gating kinetics by pre-pulses at hyperpolarizing voltages. This phenomenon, which is opposite to that described over 50 years ago in the squid axon by Cole and Moore (1960), who observed that K+ current activation kinetics were delayed by pre-pulses to more negative membrane potentials, has been interpreted by postulating that more depolarized pre-pulse potentials would allow mutant channels to preferentially populate an energetically favorable conformation in which the voltage sensors would be trapped in the inactive position, thus delaying its displacement to the active state, and, consequently, channel opening. Given that the alanine residue is smaller and more polar that valine, it appears as the mutation interferes with hydrophobic interactions occurring in the membrane bilayer or in other protein regions.

Finally, it should be mentioned that most functional studies have been performed by means of macroscopic current measurements; these, although providing important information about disease pathogenesis, are clearly unfit to reveal detailed structural changes occurring during VSD movements. Gating current measurements, although technically very challenging, are beginning to be used to characterize more precisely wild-type and mutant Kv7 channels gating behavior (Miceli et al., 2009b).

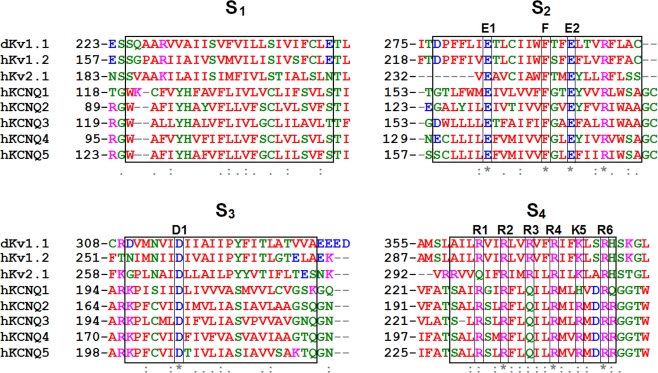

An Homology Model of Kv7.2

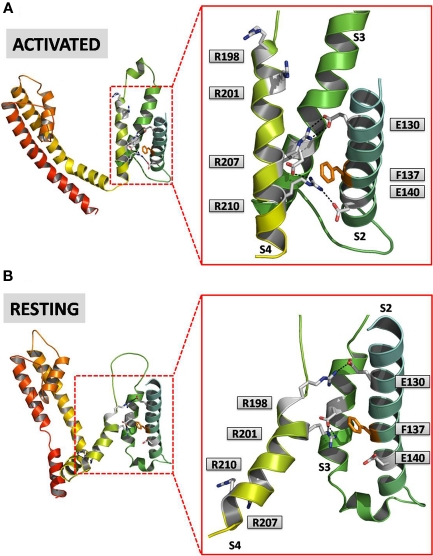

Sequence identity between Kv7.2 and the Kv1.2/2.1 chimera is 29%, and sequence similarity is 49%; these values are even higher when analysis is restricted to the VSD domain (see alignments in Figure 2). Based on this high degree of sequence homology, it seems plausible to predict an overall similar structural arrangement of the charged residues within the VSD between the two channels, although one important difference is the lack of the positively charged residue corresponding to R3 in all members of the Kv7 family, in which the R is replaced by a neutral glutamine (Q). Therefore, to provide insight into the possible structural consequences of the described mutations in the VSD causing BFNS, we built a homology model of the Kv7.2 subunit using the crystal coordinates of the Kv1.2/Kv2.1 chimera (Long et al., 2007). As previously discussed, the original crystal structure was obtained in the absence of transmembrane potential; thus, the model captures the VSD in the activated configuration (“up state”; Figure 3A). According to the previously discussed models, the VSD position is stabilized by ionized hydrogen bonds between the charged S4 Rs and the two clusters of negative charges. In particular, in the activated state, the positively charged residue at position 207 (corresponding to R4 in Figure 2) forms ionized hydrogen bonds with a negatively charged residue belonging to the external cluster (E130, E1 in Figure 2), whereas that at position 210 (corresponding to R5 in Figure 2) is predicted to interact with negative charges of the inner cluster (E140 in S2; D172 in S3 according to Kv7.2 numbering; respectively E2 and D1 in Figure 2). The two clusters are separated by the S2 phenylalanine gap (Phe 137 in Kv7.2).

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of the relevant VSD regions of VGKCs (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/align/); residues are colored according to the following scheme: magenta, basic; blue, acid; red, non-polar; green, polar.

Figure 3.

An homology model for Kv7.2 channels. Both panels show side views of a single Kv7.2 subunit at lower (left) and higher (right) magnification. (A) Shows the activated configuration of the subunit and the corresponding VSD, whereas (B) shows the resting state. Amino acids involved in intra-subunit ion pairs in either resting and activated VSD configurations are shown. The homology model of the activated VSD of the Kv7.2 channel was generated as previously described (Miceli et al., 2008b); the resting state was derived from the corresponding model of the Kv1.2 channel described by Pathak et al. (2007).

Despite the intrinsic uncertainty related to the lack of crystal coordinates for Kv channels VSDs captured in the resting (“down state”) configurations, we also attempted to built an homology model of the resting state configuration of Kv7.2 VSD based on the available literature data (Pathak et al., 2007). According to this model (Figure 3B), and as also hypothesized on the basis of biochemical experiments using functional rescue complementation by coupled mutations (Papazian et al., 1995), response to cysteine-reacting methanethiosulfonate reagents in mutant Shaker channels (Larsson et al., 1996) and, more recently, functional analysis of gating-pore currents in VSD mutants (Tombola et al., 2005), in the resting VSD configuration the negatively charged E1 residue in S2 would preferentially interact with the R1 in S4, rather than with R4 as previously described in the activated VSD configuration; moreover, the R2 residue would establish a novel interaction with the D1 residue in S3. These data suggest that, during the activation process, the S4 segment would slide upwardly because of the loss of the interaction of E1 and D1 with the positively charged residues at R1 and R2, respectively, which would instead be replaced by the R4 and R5 residues. As a consequence, the R207 residue (R4) would flip up around the Phe 137 residue on its way toward the extracellular side of the membrane. The role of this Phe residue (Phe233 in the Kv2.1 paddle-Kv1.2 chimera) in forming the extracellular lid of an occluded binding site in voltage sensors into which S4 positive charges bind has been recently revealed (Tao et al., 2010).

Analysis of the model suggests that in Kv7.2 the replacement of R207 with a neutral amino acid such as Q or W hampers its interaction with the external cluster of negative charges (E130), destabilizing the activated configuration of the VSD, and providing a plausible explanation for the positive shift in the steady-state voltage dependence of activations observed in these mutants. Furthermore, it seems possible to speculate that the presence of a bulkier W at this position would delay the movement of R207 across the phenylalanine gap more than the smaller Q residue, leading to a substantial slowing of R207W channels opening kinetics when compared to the R207Q mutant.

Moreover, within the S4–S5 linker of Kv7.2, two ionized hydrogen bonds are formed between the side chain of the D212 residue and the lysine residue at position 219 (K219); in fact, the carboxyl end of D212 closely interacts with the aminic group of the K219 side chain (2.18 Å distance), as well as with the aminic group of the protein backbone (2.87 Å distance); furthermore, the carboxyl group on the protein backbone of the D212 residue can form a third polar interaction with the aminic group of the K219 side chain (3.15 Å distance). Analysis of our homology model suggests that the substitution of the D212 residue with a glycine would loosen the previously described interactions involving its lateral chain carboxyl group, preserving only the interaction between the backbone carboxyl group and the aminic group in the K219 residue. If these interactions are essential in keeping the VSD in its activated configuration, it seems therefore not surprising that their absence would cause the Kv7.2 channels carrying the D212G mutations to display a reduced opening probability and a decreased sensitivity to voltage (Miceli et al., 2009a).

Kv7 Channel Modulators: Molecular Heterogeneity and Molecular Sites of Action

Pharmacological relevance of Kv7 channels

Given the described functional relevance of IKM/Kv7 channels in a wide range of physiological processes, it is not surprising that they are currently considered as relevant targets for the pharmacological treatment of several human diseases.

In particular, Kv7.1 blockers might be of help in treating arrhythmias (chromanol-293B or L-768673; Salata et al., 2004), whereas blockers of neuronal IKM formed by Kv7.2–Kv7.5 subunits, such as linopiridine, have been proposed to ameliorate the cognitive decline occurring in neurodegenerative diseases (Fontana et al., 1994); however, these drugs have either not been tested or have generated inconclusive results in humans. Therefore, in the last few years, research on most of Kv7 blockers has progressed rather slowly.

By contrast, considerable interest has recently grown around neuronal IKM/Kv7 channel activators, given the extensive preclinical results showing that they might be effective tools against migraine, epilepsy, neuropathic pain, and neuropsychiatric disorders including anxiety, attention-hyperactivity disorders, mania (Andreasen and Redrobe, 2009), bipolar disease, and schizophrenia (Hansen et al., 2008). In all these diseases, hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential and decreased action potential generation prompted by the activation of neuronal K+ currents in excitatory neurons, may result in an effective therapeutic strategy. Moreover, since Kv7 subunit expression has been also found in non-neuronal tissues such as the smooth muscle of blood vessels and several visceral organs, as well as in skeletal muscle, IKM/Kv7 channel activators may be of benefit in the treatment of other diseases such as urinary incontinence (Rode et al., 2010), systemic or pulmonary arterial hypertension (Morecroft et al., 2009), and skeletal muscle diseases (Iannotti et al., 2010).

Retigabine

Retigabine is the prototype IKM opener, and is currently under clinical scrutiny as an anticonvulsant. Retigabine is a structural analog of Flupirtine (D-9998; trade name Katadolon®), a triaminopyridine successfully used in clinical practice in some European countries since 1984 as a centrally acting non-opioid analgesic also provided with muscle-relaxing and neuroprotective actions, but devoid of appreciable anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activity. Retigabine's efficacy as an anticonvulsant has been assessed in several preclinical models as well as in phase I, II, and III clinical studies (reviewed in Barrese et al., 2010). Retigabine activates Kv7.2–Kv7.5 channels at concentrations 10–30 times lower than those affecting other ion channels. Activation of Kv7 channels by retigabine is consequent to a complex combination of two distinct biophysical effects: an hyperpolarization shift of the voltage dependence of channel activation, and an increase of the channel maximal opening probability which leads to an enhancement of the macroscopic currents (Tatulian et al., 2001). Noteworthy, retigabine does not affect Kv7.1 channels, an important issue when considering the cardiac safety profile of this novel antiepileptic compound.

The entity of the hyperpolarizing shift induced by retigabine on the Kv7 current activation varies among channels formed by different Kv7 subunits: it is maximal for Kv7.3 (−43 mV), intermediate for Kv7.2 (−24 mV), and smaller for Kv7.4 (−14 mV) homomeric channel (Tatulian et al., 2001). Moreover, in Kv7.5 homomeric channels, retigabine fails to alter the voltage dependence, but markedly increased the maximal amount of current irrespectively on the membrane potential (Dupuis et al., 2002). Kv7.4 channels show both the shift in voltage dependence opening probability, and the increase of the maximal conductance; by contrast, in the maximal amount of current elicited by strong depolarization Kv7.2 and Kv7.2/Kv7.3 channels was not affected by retigabine.

These changes were accompanied by a variable degree of drug-induced delay in channel closure (deactivation), suggesting that the primary molecular consequence of the interaction of retigabine with the channel protein was a stabilization of the channel pore in the open conformation.

The potency of retigabine in causing the activation of channels formed by distinct Kv7 subunits appears slightly different; in most instance, Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 show higher (EC50 < 1 μM) and Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 lower (EC50 > 1 μM) sensitivity to the drug. Nevertheless, since these differences are quantitatively rather small, retigabine is currently regarded as an IKM opener poorly selective for channels composed of Kv7.2–Kv7.5 subunits.

Noteworthy, both retigabine and flupirtine show a small but consistent inhibitory effect on native voltage-dependent K+ currents in both neurons (Rundfeldt, 1997) and smooth muscle cells (Yeung et al., 2008), particularly evident at higher drug concentrations (>10 μM), and more depolarized potentials (>0 mV). Although the pharmacological relevance of these observations is still undefined, these results are consistent with a “bimodal” mechanism of action for these drugs.

Other IKM activators

The demonstration that retigabine, by activating neuronal IKM, can exert anticonvulsant activity, have led to an explosion of interest toward the identification of additional congeners acting as IKM activators (Miceli et al., 2008a). Among these, zinc pyrithione (ZnPy), a compound used for dandruff control and psoriasis treatment, has been demonstrated to enhance the activity of all Kv7 channels, except those formed by Kv7.3 subunits (Xiong et al., 2007). In sensitive channels, ZnPy causes an increase of maximal open probability, a significant hyperpolarization shift of voltage dependence, and a marked deactivation rate reduction. Noteworthy, its agonistic action was non-competitive with that exerted by retigabine, giving rise to combinatorial effects when the two molecules were applied together (Xiong et al., 2008). In Kv7.1 channels, activation by ZnPy is occluded by the co-expression of the auxiliary subunit KCNE1 (Xiong et al., 2008), a result suggestive of a mechanistic overlap between ZnPy- and KCNE1-induced Kv7.1 current potentiation.

Phenamates such as meclofenamic acid and diclofenac are well-known and widely used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs acting as non-selective inhibitors of the cyclooxygenase COX-1 and COX-2. These compounds have been described to also act as openers of Kv7 channels and to show robust antiepileptic properties in vivo: indeed, similarly to retigabine, they shift leftward the voltage dependence of Kv7.2/3 channel activation, decrease deactivation kinetics, and hyperpolarize the resting membrane potential in cultured cortical neurons (Peretz et al., 2005). Both compounds did not affect Kv7.1 or Kv7.1 + KCNE1 channels activity. Kv7.2/3 channel activation by meclofenamic acid and diclofenac showed an EC50 of about 3 μM. Based on these findings, new diphenylamine carboxylate derivatives have been designed to dissociate the IKM-opening property from COX inhibition. Indeed, diclofenac derivatives with poor (NH6; Peretz et al., 2007b) or absent (NH29; Peretz et al., 2007a) COX-blocking activity were synthesized; these molecules reduced neuronal excitability and/or showed anticonvulsant effects in murine models of seizures. Similarly to meclofenamic acid and diclofenac, NH29 increased Kv7.2 macroscopic currents, produced an hyperpolarizing shift of the activation curve and significantly reduced both activation and deactivation rates of Kv7.2 channels, while it failed to affect homomeric Kv7.1 and Kv7.1/KCNE1 channels. Electrophysiological recordings from hippocampal neurons showed that NH29 powerfully depressed synaptic transmission and inhibited glutamate and GABA release (Peretz et al., 2010), a result similar to that observed with retigabine (Martire et al., 2004). Noteworthy, diclofenac has been recently shown to act also as an activator of homomeric Kv7.4 channels with an EC50 ∼ 100 μM, and an inhibitor of homomeric Kv7.5 channels with an intermediate IC50 (∼20 μM), being therefore the first compound to allow functional discrimination between these two channels subtypes (Brueggemann et al., 2011).

ICA-27243 is a compound belonging to the chemical class of substituted benzamides which, in contrast to retigabine which only shows poor discrimination among channels formed by different Kv7 subunits, selectively increased the maximal conductance and shifted the steady-state activation curve toward more hyperpolarized potentials in Kv7.2/Kv7.3 heterotetramers (EC50 of 0.4 μM). ICA-27243 exhibited little activity against Kv7.1 channels, while its potency on Kv7.4 or Kv7.3/Kv7.5 channels was 20-fold and >100-fold lower than that on Kv7.2/Kv7.3 heterotetramers, respectively (Wickenden et al., 2008); moreover, ICA-27243 exhibited anticonvulsant properties in preclinical models of seizures in rodents (Roeloffs et al., 2008).

Other enhancers of Kv7-mediated currents include BMS-204352, originally developed as an opener of Ca2+- and VGKCs (Schrøder et al., 2001; Korsgaard et al., 2005), and the acrylamide compounds defined as (S)-1 (Bentzen et al., 2006) and (S)-2 (Blom et al., 2009). Although these molecules can activate channels formed by all neural Kv7 subunits (except Kv7.1, with or without KCNE1), they display a noticeably stronger action on channels formed by Kv7.4 subunits (BMS-204352), or on Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 subunits [(S)-1 and (S)-2]. At variance with ZyPn, no additive effect on Kv7.4 current amplitude was observed when both retigabine and (S)-1 or BMS204352 were applied simultaneously (Bentzen et al., 2006).

Finally, the cysteine-alkylating agent N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) also has been shown to increase the currents carried by native and heterologously expressed Kv7 channels (Roche et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004), being active on Kv7.2, 7.4, or 7.5, but not on Kv7.1 and Kv7.3 channels. In sensitive channels, NEM-induced augmentation of the macroscopic current was mainly due to an increase in single-channel open probability. Similarly, currents carried by Kv7.2, Kv7.4, and Kv7.5 channels (but not by Kv7.1 or Kv7.3 channels) were strongly potentiated by oxidative modification caused by H2O2 exposure (Gamper et al., 2006).

Some IKM activators bind to the pore and the intracellular gate regions of Kv7 channels

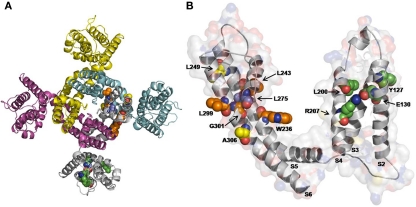

Mutagenesis and modeling experiments have suggested that, in channels formed by drug-sensitive Kv7 subunits, retigabine binds to a hydrophobic pocket located between the cytoplasmic parts of S5 and S6 in the open channel configuration. Within this cavity, a tryptophan residue in the intracellular end of the S5 helix (W236 in the Kv7.2 sequence) seems to play a crucial role (Schenzer et al., 2005; Wuttke et al., 2005; Figure 4A); replacement of W236 with a smaller and less hydrophobic leucine residue (naturally present at the corresponding position in retigabine-insensitive Kv7.1 subunits) largely prevents retigabine-induced IKM activation. Using a refined chimeric strategy, other residues crucial for retigabine-induced channel activation of Kv7.2 have been identified: in particular, L243 in S5, L275 in the pore, L299 and Gly301 (corresponding to the putative gating hinge in Long et al., 2005a,b) in the S6 segments of the neighboring subunit (according to Kv7.2 numbering; Lange et al., 2009; Figure 1; Table 1). Except for Leu275, all these amino acids are conserved among neural Kv7 subunits but are missing in cardiac Kv7.1 subunits. The conserved tryptophan residue within S5 is also a crucial structural element of the binding site for BMS-204352 and (S)-1 in Kv7.2–Kv7.5 channels (Bentzen et al., 2006; Blom et al., 2009), a result consistent with the lack of functional additivity observed when these compounds are applied together with retigabine.

Figure 4.

An homology model for drug binding to Kv7.2 channels. Top view of the overall structure of the channel formed by four identical Kv7.2 subunits (A), and enlarged view of a single Kv7.2 subunit (B) captured in the activated configuration. The residues involved in binding of retigabine (indicated in orange), zinc pyrithione (indicated in yellow), and NH29 (indicated in green) highlighted. The L275 residue in the pore, common to both retigabine and zinc pyrithione binding, is indicated in violet. The S1 region has been removed for clarity. The homology model of the Kv7.2 channel was generated as previously described (Miceli et al., 2008b).

Electrophysiological and mutagenesis experiments identified a binding site for ZnPy partially distinct from that of retigabine; in fact, ZnPy binds the extracellular side of the S5–S6 region: in particular, residues L249, L275, and A306 seem to be involved in the formation of binding site (Xiong et al., 2007). Residue L249 is localized in the S5 segment, while L275 in the pore loop, near to the selectivity filter; the position of the two residues may explain the increase of the open probability caused by the interaction of ZnPy with Kv7 channels. Moreover, residue A306 is localized between G301 and the conserved Pro-Ala-Gly sequence in the S6 domain. The location of these residues in the channel structure is consistent with the hypothesis that ZnPy stabilizes the open conformation.

The ability of retigabine and other IKM activators to bind to an hydrophobic pocket contributed by S5 and S6 and accessible from the cytoplasm in the open channel configuration is reminiscent of the high affinity use-dependent binding site for local anesthetics and antiarrhythmic drugs in VGNCs (Sheets et al., 2010), as well as of the Ca2+-antagonists of the phenylalkylamine and dihydropyridine chemical group on VGCCs (Mitterdorfer et al., 1998).

A novel binding site in the vsd for Kv7 activators

In addition to sites in S5 and S6, the VSD has also been identified as a receptor site for compounds acting as gating modifiers. As recently reviewed (Catterall et al., 2007; Swartz, 2007; Borjesson and Elinder, 2008), six distinct neurotoxin receptor sites have been identified in VGNCs. Toxins acting at receptor sites within the VSD (S3–S4 loop and N-terminal end of S4) in VGNCs are presumed to act by a voltage-sensor trapping mechanism to alter channel gating; more specifically, site 3-acting toxins (α-scorpion toxins, sea-anemone toxins, and some spider toxins known to slow or block sodium channel inactivation) would stabilize the resting configuration of the VSD, whereas toxins acting at site 4 (β-scorpion toxins and some spider toxins, both shifting the voltage dependence of sodium channel activation in the hyperpolarizing direction and reducing the peak sodium current amplitude) would enhance activation by holding the S4 segment in domain II in its activated configuration.

In more general terms, it has been proposed that a voltage-sensor trapping mechanism may explain the actions of polypeptide toxins that alter the voltage dependence of gating in most voltage-gated channels. In fact, toxin-induced channel activation by a sensor trapping mechanism can also occur in VGCCs (agatoxins from spiders), and in VGKCs of the Kv2 and Kv4 (hanatoxins from tarantula; Swartz and MacKinnon, 1997), or Kv3 and Kv11 (sea-anemone toxins; Diochot and Lazdunski, 2009) subclasses. It has been reported that a conserved structural motif in VGCCs and VGKCs can account for the “promiscuity” of both hanatoxin and grammotoxin (another tarantula toxin) to interact with both channel classes (Li-Smerin and Swartz, 1998), and, possibly, with non-voltage-gated channels of the TRPV1 subfamily (Siemens et al., 2006).

The existence in Kv7 channels of a molecular site of action for IKM activators distinct from that of retigabine was first hinted by the results from structure-function experiments showing that the replacement of the tryptophan residue at position 236 in Kv7.2 channels, while largely abolishing the effect of retigabine, failed to affect current potentiation by phenamates (meclofenamic acid and diclofenac; Miceli et al., 2008a). The fact that phenamates acted at sites distinct from those occupied by retigabine was also consistent with the additivity shown by phenamates and retigabine in functional experiments on Kv7.2/Kv7.3 channels (Peretz et al., 2005). More recently, the diphenylamine carboxylate derivative NH29 (Peretz et al., 2007a), an analog of diclofenac, has been shown to activate Kv7.2 channels in both closed and open states by targeting the extracellular region of the VSD at the interface of helices S1, S2, and S4 (Peretz et al., 2010). In particular, within this region, NH29 interacts with residues L197, R198, R207, and R214 localized in the S4 segment (Figure 4B). In addition to site-specific mutagenesis and electrophysiological experiments, docking data suggested that, in the open state, NH29 stabilizes the salt bridge between the guanidinium group of the third arginine residue of the S4 segment and the carboxylate group of E130 (in S2), a feature similar to that described for tarantula toxins in the capsaicin receptor TRPV1 (Siemens et al., 2006) and in other Kv channels (Swartz, 2007); by stabilizing the interaction between E130 in S2 and R207 in S4, NH29 would favor the activated VSD configuration, thus leading to the described activation of Kv7.2 channels. On the other hand, in the closed state the compound would preferentially interact with the first arginine (R198) of the S4 segment.

Finally, the S1–S4 VSD also seems to represent the molecular site of action for ICA-27243 (Wickenden et al., 2008), another rather selective Kv7.2/3 activator exhibiting little activity against either Kv7.4 or Kv7.1 channels. However, within this region, specific amino acids involved in drug binding have not yet been identified (Padilla et al., 2009).

A summary of the residues involved in binding distinct IKM activators is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Residues presumably involved in binding different IKM activators.

| Drugs | Binding site | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| R198 (S4), L200 (S4), R207 (S4), and R214 (S4)Retigabine | W236 (S5), L243 (S5), L275 (pore), L299 (S6 of the neighboring subunit), and G301 (S6) | Wuttke et al. (2005), Schenzer et al. (2005), Lange et al. (2009) |

| Zinc pyrithione | L249 (S5), L275 (pore), and A306 (S6) | Xiong et al. (2007) |

| Diphenylamine carboxylate derivate NH29 | K120 (loop S1–S2), Y127 (S2), E130 (S2), L197 (S4), R198 (S4), L200 (S4), R207 (S4), and R214 (S4) | Peretz et al. (2010) |

| ICA-27243 | S1-S4 transmembrane domain | Padilla et al. (2009) |

| Acrylamide derivate (S)-1 | W242 (S5; according to Kv7.4 numbering) | Bentzen et al. (2006) |

| BMS-204354 | W242 (S5; according to Kv7.4 numbering) | Bentzen et al. (2006) |

| NEM (N-ethylmaleimide) | C242 (S5); C519 (C-terminal; according to Kv7.4 numbering) | Li et al. (2004), Roche et al. (2002) |

| H2O2 | C150 to C153 | Gamper et al. (2006) |

Conclusion

When compared to voltage-dependent K channels of the Kv1–4 subclasses which have been in the spotlight for over 20 years, Kv7 channels have only recently gained centre-stage attention. Although voltage-dependent currents having peculiar biophysical and neurochemical properties (slow activation and deactivation kinetics, lack of inactivation, regulation by Gq-linked neurotransmitter receptors) have been known for quite some time and variably named and classified in various tissues (IKs in the heart, IKM in neurons, IKx in photoreceptors, IKn in hair cells), their molecular basis have remained elusive until the genetic basis of monogenic channelopathies such as the long and short QT syndromes, BFNS, and some rare forms of dominantly inherited deafness had been successfully identified. A solid (yet incomplete) description has followed showing that subunits encoded by distinct members of the Kv7 gene subfamily represent the molecular basis of each of these currents. Based on such seminal discoveries, Kv7 channels are currently considered as relevant targets for drugs currently being developed to dissect the functional relevance of each of the five Kv7 channel genes in distinct tissues, and to treat a wide array of human diseases, ranging from arrhythmias to pain states.

In this scene, understanding the distinct molecular sites on Kv7 channels responsible for the action of modulators and for the effects of disease-causing mutations will unveil the molecular pathogenesis of these channelopathies, identify other pharmacophoric structures, and lead to a better picture of the complex structural rearrangements accompanying channel function. In particular, the fact that, in the VSD of Kv7.2, some of the residues affecting drug-induced IKM activation also represent crucial gating residues targeted by BFNS-causing mutations suggests that this region acts not only as a major molecular determinant for disease pathogenesis, but also for potential pharmacological intervention against epilepsy. Since BFNS is a rather benign disease, most affected neonates do not require pharmacological intervention; nevertheless, the fact that the same mutations responsible for BFNS can cause resistance to IKM activators should be taken into account. In fact, the role of IKM in neuronal excitability control appears particularly relevant in the early phases of life (Okada et al., 2003; reviewed in Barrese et al., 2010), and it has been proposed that IKM openers can overcome some of the limitations associated to anticonvulsants commonly used as first-line drugs in neonates (usually phenobarbital and phenytoin; Olney et al., 2004). Thus, the ability of different drugs to activate IKM by binding to different regions of the Kv7.2 molecule might, at least in principle, allow an individually tailored and genotype-specific pharmacological treatment for BFNS.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest

Acknowledgments

Work on KCNQ/IKM channels in the Author's laboratories is currently supported by grants from: the European Union (E-Rare 2007, EUROBFNS); Fondazione Telethon Italy (GGP07125); the Fondazione San Polo – IMI (Project Neuroscience); and Regione Molise (Convenzione AIFA/Regione Molise).

References

- Aggarwal S. K., MacKinnon R. (1996). Contribution of the S4 segment to gating charge in the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron 16, 1169–1177 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern C. A., Horn R. (2004). Stirring up controversy with a voltage sensor paddle. Trends Neurosci. 27, 303–307 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen J. T., Redrobe J. P. (2009). Antidepressant-like effects of nicotine and mecamylamine in the mouse forced swim and tail suspension tests: role of strain, test and sex. Behav. Pharmacol. 20, 286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C. M., Bezanilla F. (1973). Currents related to movement of the gating particles of the sodium channels. Nature 242, 459–461 10.1038/242459a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrese V., Miceli F., Soldovieri M. V., Ambrosino P., Iannotti F. A., Cilio M. R., Taglialatela M. (2010). Neuronal potassium channel openers in the management of epilepsy-role and potential of retigabine. Clin. Pharmacol. Adv. Appl. 2, 225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini G., Miceli F., Soldovieri M. V., Miraglia del Giudice E., Pascotto A., Taglialatela M. (2010). “Benign familial neonatal seizures,” in GeneReviews [Internet], eds Pagon R. A., Bird T. C., Dolan C. R., Stephens K. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington; ). [Google Scholar]

- Bellocq C., van Ginneken A. C., Bezzina C. R., Alders M., Escande D., Mannens M. M., Baró I., Wilde A. A. (2004). Mutation in the KCNQ1 gene leading to the short QT-interval syndrome. Circulation 109, 2394–2397 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130409.72142.FE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen B. H., Schmitt N., Calloe K., Dalby Brown W., Grunnet M., Olesen S. P. (2006). The acrylamide (S)-1 differentially affects Kv7 (KCNQ) potassium channels. Neuropharmacology 51, 1068–1077 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. (2008). How membrane proteins sense voltage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F., White M. M., Taylor R. E. (1982). Gating currents associated with potassium channel activation. Nature 296, 657–659 10.1038/296657a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biervert C., Schroeder B. C., Kubisch C., Berkovic S. F., Propping P., Jentsch T. J., Steinlein O. K. (1998). A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science 279, 403–406 10.1126/science.279.5349.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom S. M., Schmitt N., Jensen H. S. (2009). The acrylamide (S)-2 as a positive and negative modulator of Kv7 channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. PLoS ONE 4, e8251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjesson S. I., Elinder F. (2008). Structure, function, and modification of the voltage sensor in voltage-gated ion channels. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 52, 149–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans F., Swartz K. J. (2010). Targeting voltage sensors in sodium channels with spider toxins. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 175–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueggemann L. I., Mackie A. R., Martin J. L., Cribbs L. L., Byron K. L. (2011). Diclofenac distinguishes among homomeric and heteromeric potassium channels composed of KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 subunits. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 10–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo P., del Giudice E. M., Coppola G., Pascotto A., Annunziato L., Taglialatela M. (2002). Benign familial neonatal convulsions caused by altered gating of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 22, RC199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A. (2010). Ion channel voltage sensors: structure, function, and pathophysiology. Neuron 67, 915–928 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A., Cestèle S., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Yu F. H., Konoki K., Scheuer T. (2007). Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon 49, 124–141 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha A., Snyder G. E., Selvin P. R., Bezanilla F. (1999). Atomic scale movement of the voltage-sensing region in a potassium channel measured via spectroscopy. Nature 402, 809–813 10.1038/45552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier C., Singh N. A., Ryan S. G., Lewis T. B., Reus B. E., Leach R. J., Leppert M. (1998). A pore mutation in a novel KQT-like potassium channel gene in an idiopathic epilepsy family. Nat. Genet. 18, 53–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H. J., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (2006). Polarized axonal surface expression of neuronal KCNQ channels is mediated by multiple signals in the KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 C-terminal domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8870–8875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole K. S., Moore J. W. (1960). Potassium ion current in the squid giant axon: dynamic characteristic. Biophys. J. 1, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G., Castaldo P., Miraglia del Giudice E., Bellini G., Galasso F., Soldovieri M. V., Anzalone L., Sferro C., Annunziato L., Pascotto A., Tagliatatela M. (2003). A novel KCNQ2 K+ channel mutation in benign neonatal convulsions and centrotemporal spikes. Neurology 61, 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedek K., Kunath B., Kananura C., Reuner U., Jentsch T. J., Steinlein O. K. (2001). Myokymia and neonatal epilepsy caused by a mutation in the voltage sensor of the KCNQ2 K+ channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12272–12277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delemotte L., Treptow W., Klein M. L., Tarek M. (2010). Effect of sensor domain mutations on the properties of voltage-gated ion channels: molecular dynamics studies of the potassium channel Kv1.2. Biophys J. 99, L72–L74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P., Brown D. A. (2005). Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 850–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diochot S., Lazdunski M. (2009). Sea anemone toxins affecting potassium channels. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 46, 99–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle D. A., Morais Cabral J., Pfuetzner R. A., Kuo A., Gulbis J. M., Cohen S. L., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (1998). The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 280, 69–77 10.1126/science.280.5360.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis D. S., Schroder R. L., Jespersen T., Christensen J. K., Christophersen P., Jensen B. S., Olesen S. P. (2002). Activation of KCNQ5 channels stably expressed in HEK293 cells by BMS-204352. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 437, 129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana D. J., Inouye G. T., Johnson R. M. (1994). Linopirdine (DuP 996) improves performance in several tests of learning and memory by modulation of cholinergic neurotransmission. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 49, 1075–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N., Zaika O., Li Y., Martin P., Hernandez C. C., Perez M. R., Wang A. Y., Jaffe D. B., Shapiro M. S. (2006). Oxidative modification of M-type K(+) channels as a mechanism of cytoprotective neuronal silencing. EMBO J. 25, 4996–5004 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood I. A., Ohya S. (2009). New tricks for old dogs: KCNQ expression and role in smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 156, 1196–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman G. A., Chandy K. G., Adelman J. P., Aiyar J., Bayliss D. A., Clapham D. E., Covarriubias M., Desir G. V., Furuichi K., Ganetzky B., Garcia M. L., Grissmer S., Jan L. Y., Karschin A., Kim D., Kuperschmidt S., Kurachi Y., Lazdunski M., Lesage F., Lester H. A., McKinnon D., Nichols C. G., O'Kelly I., Robbins J., Robertson G. A., Rudy B., Sanguinetti M., Seino S., Stuehmer W., Tamkun M. M., Vandenberg C. A., Wei A., Wulff H., Wymore R. S. (2003). International Union of Pharmacology. XLI. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: potassium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 55, 583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H. H., Waroux O., Seutin V., Jentsch T. J., Aznar S., Mikkelsen J. D. (2008). Kv7 channels: interaction with dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission in the CNS. J. Physiol. 586, 1823–1832 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmar A. J., Hills R. A., Rosser E. M., Jones M., Buneman O. P., Dunbar D. R., Greenhill S. D., Hale V. A., Sharman J. L., Bonner T. I., Catterall W. A., Davenport A. P., Delagrange P., Dollery C. T., Foord S. M., Gutman G. A., Laudet V., Neubig R. R., Ohlstein E. H., Olsen R. W., Peters J., Pin J. P., Ruffolo R. R., Searls D. B., Wright M. W., Spedding M. (2009). IUPHAR-DB: the IUPHAR database of G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D680–D685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron S. E., Cox K., Grinton B. E., Zuberi S. M., Kivity S., Afawi Z., Straussberg R., Berkovic S. F., Scheffer I. E., Mulley J. C. (2007). Deletions or duplications in KCNQ2 can cause benign familial neonatal seizures. J. Med. Genet. 44, 791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. (2001). Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd Edn. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin A. L., Huxley A. F. (1952). A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 117, 500–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J., Maljevic S., Shankar A., Siegel A., Weissman B., Holt P., Olson L., Lerche H., Escayg A. (2006). Subthreshold changes of voltage-dependent activation of the K(V)7.2 channel in neonatal epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 24, 194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti F. A., Panza E., Barrese V., Viggiano D., Soldovieri M. V., Taglialatela M. (2010). Expression, localization, and pharmacological role of Kv7 potassium channels in skeletal muscle proliferation, differentiation, and survival after myotoxic insults. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 332, 811–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A., Fukuma G., Uehara A., Miyajima T., Makita Y., Hamachi A., Yasukochi M., Inoue T., Yasumoto S., Okada M., Kaneko S., Mitsudome A., Hirose S. (2009). A de novo KCNQ2 mutation detected in non-familial benign neonatal convulsions. Brain Dev. 31, 27–33 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (2002a). Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature 417, 515–522 10.1038/417515a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (2002b). The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature 417, 523–526 10.1038/417523a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Ruta V., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (2003a). X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 423, 33–41 10.1038/nature01580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Ruta V., Chen J., Lee A., MacKinnon R. (2003b). The principle of gating charge movement in a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 423, 42–48 10.1038/nature01581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili-Araghi F., Jogini V., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Tajkhorshid E., Roux B., Schulten K. (2010). Calculation of the gating charge for the Kv1.2 voltage-activated potassium channel. Biophys. J. 98, 2189–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsgaard M. P., Hartz B. P., Brown W. D., Ahring P. K., Strobaek D., Mirza N. R. (2005). Anxiolytic effects of maxipost (BMS-204352) and retigabine via activation of neuronal Kv7 channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 282–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubisch C., Schroeder B. C., Friedrich T., Lutjohann B., El-Amraoui A., Marlin S., Petit C., Jentsch T. J. (1999). KCNQ4, a novel potassium channel expressed in sensory outer hair cells, is mutated in dominant deafness. Cell 96, 437–446 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80556-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo A., Gulbis J. M., Antcliff J. F., Rahman T., Lowe E. D., Zimmer J., Cuthbertson J., Ashcroft F. M., Ezaki T., Doyle D. A. (2003). Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science 300, 1922–1926 10.1126/science.1085028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]