Abstract

We utilized data from patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) to assess the risk of new onset diabetes (NOD) with beta-blockers, and to determine whether angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition would modify this risk. The Prevention of Events with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibition (PEACE) trial randomized 8290 patients with stable CAD to trandolapril or placebo. The presence of NOD was assessed at each study visit over a median follow-up time of 4.8 years. We examined the risk of NOD associated with beta-blockers use with Cox regression models, adjusting for 25 baseline covariates, and tested whether this risk was modified by randomization to the ACE inhibitor. Of 6910 patients without diabetes mellitus at enrollment (1179 females/5731 males, mean age 64 ± 8 years), 4147 (60%) were taking beta blockers, and 733 (8.8%) developed NOD. We observed a significant interaction between beta-blocker use and randomization to ACE inhibitor with respect to new onset diabetes (p = 0.028). Participants taking beta-blockers assigned to the placebo group (N=2090) were at increased risk for NOD adjusting for baseline covariates (HR 1.63, 95% confidence interval 1.29, 2.05, p<0.001, while this risk was attenuated in those assigned to trandolapril (N=2057) (HR 1.11, 95% confidence interval 0.87, 1.42; p=0.39). Beta blocker use was associated with increased risk for NOD in patients with stable CAD, and this risk was reduced in patients treated concurrently with an ACE inhibitor. In conclusion, these data suggest that ACE inhibition may attenuate the risk for glucose abnormalities observed in patients taking beta blockers.

Keywords: ACE inhibitors, Beta-Blockers, Clinical Trials, Diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Several classes of common cardiovascular medications have been shown in clinical trials to have disparate effects on blood glucose and the risk for development of new onset diabetes mellitus (NOD). Beta blockers (BB) have been associated with an increased risk for development of NOD.1,2 Beta-blockers may negatively affect glucose homeostasis through increased hepatic glucose production, blockade of insulin release, and may worsen insulin resistance through reduced peripheral glucose ulitization.3,4 The effect of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors on diabetes risk has been more varied. Post-hoc analyses in large trials originally suggested that ACE inhibition might delay or prevent the onset of DM,2,5,6 while the DREAM trial did not show a benefit on frank development of diabetes, although did show some improvement in glycemic control with ACE inhibitors.7 Mechanistically, ACE inhibitors may improve insulin sensitivity secondary to kinin accumulation and increased peripheral blood flow.8–11 The Prevention of Events with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibition (PEACE) trial was designed to test the hypothesis that an ACE inhibitor would reduce cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary artery disease.12 Trandolapril therapy did not reduce the primary endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, or coronary revascularization, but was associated with a 17% reduction in NOD. We utilized data from PEACE to assess the influence of beta blockers on risk for NOD, and whether this risk was modified by randomization to ACE inhibition.

METHODS

PEACE included patients at least 50 years old, with stable coronary artery disease, defined as history of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or stenosis greater than 50% on angiography, and with normal or mildly reduced left ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction > 40%). Patients were excluded from PEACE if at the time of screening coronary artery disease was not stable (i.e. hospitalized for unstable angina in the preceding 2 months, had coronary revascularization within the prior 3 months), had a planned elective coronary revascularization, a serum creatinine value >2.0 mg/dL (177 > μmol/L), or a serum potassium > 5.5 mEq/L. Patients were randomly assigned to receive the ACE inhibitor trandolapril (titrated to a target dose of 4mg daily) or to placebo and followed for a median of 4.8 years, as previously described13. The PEACE study protocol was approved by each participating site’s institutional review board. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with established guidelines for the protection of human subjects.

Of the 8290 patients randomized, we included in this analysis 6910 patients who did not have diabetes at baseline, assessed by patient report. The primary outcome variable for this analysis was NOD; diabetic status (i.e. the presence of a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus), which was assessed by study personnel via patient history at each study visit every 6 months and marked on the case report forms. No other information about the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was available, including laboratory measurements. Medications were also recorded at baseline and at each visit. Specific beta blockers were not recorded.

Baseline demographics between participants taking or not taking beta blockers were compared to identify potential differences. Between group assessments were performed using t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical variables. The risk for NOD associated with beta-blocker use at baseline was examined with Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for baseline covariates as well as randomized treatment interactions. Beta blocker use was also explored as a time dependent covariate. Model covariates, chosen a priori, included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), tobacco use, systolic & diastolic blood pressure, glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, baseline cholesterol and potassium concentrations, history of coronary disease on angiography, myocardial infarction, angina, percutanous transluminal coronary arterioplasty, coronary artery bypass graft, stroke, transient ischemic attack, intermittent claudication, Canadian Cardiovascular Society Functional Class and use of lipid lowering agents, digoxin, aspirin or antiplatelets. To test the robustness of multivariable models, we performed a propensity adjusted analysis in which we generated a propensity score for baseline beta-blocker use in a logistic regression of baseline covariates, and then adjusted for this propensity score in the Cox regressions. Since the determination of DM status was assessed every 6 months, we additionally utilized discrete-time proportional hazards models, taking into account the discrete nature of the NOD information captured in the study. The authors had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

RESULTS

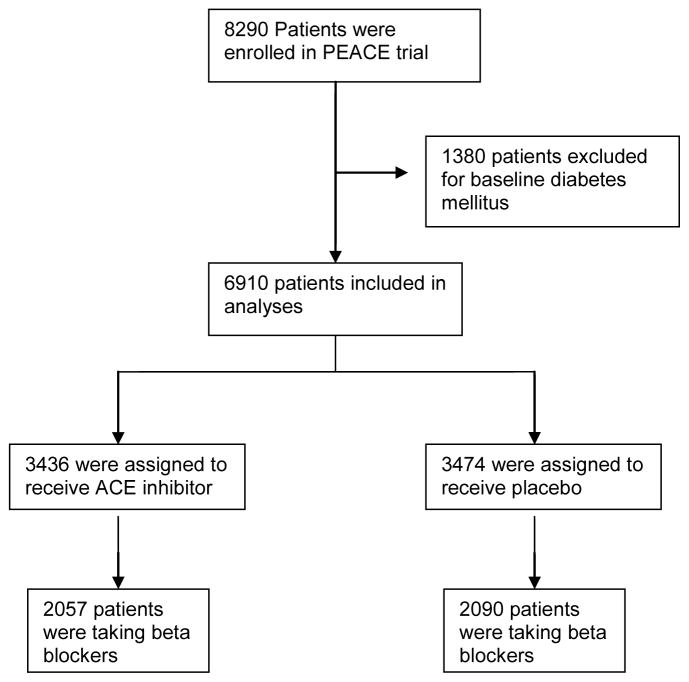

Out of 6910 patients without diabetes included in these analyses, 4147 (60%) were taking beta blockers (figure 1) at baseline. Of 4147 taking beta blockers, 2090 were assigned to the treatment group and 2057 were assigned to the placebo group. Baseline characteristics of all the analyzed subjects, broken down by beta blocker use, are shown in Table 1. Participants taking beta blockers were more likely to be younger in age, have a higher BMI, a history of coronary disease, documented myocardial infarction (MI), and were more likely to have undergone coronary interventions, compared with patients not taking beta-blockers.

Figure 1.

Study subjects included in analyses

Table I.

Subject Characteristics

| Beta Blocker | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All subjects (N=6910) | YES (N=4147) | NO (N=2763) | P value |

| Age (years) (± SD) | 64 ± 8 | 64 ± 8 | 65 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Women | 17% | 18% | 16% | 0.05 |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) | 28.1 | 28.4 | 27.6 | <0.001 |

| Current tobacco use | 14% | 14% | 15% | 0.49 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 58 ± 9 | 58 ± 9 | 58 ± 9 | 0.31 |

| Hypertension | 44% | 49% | 36% | <0.001 |

| Documented myocardial infarction | 56% | 58% | 52% | <0.001 |

| Coronary disease on angiography | 60% | 65% | 54% | <0.001 |

| Angina pectoris | 69% | 71% | 65% | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 37% | 35% | 41% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0.44 |

| Medicines | ||||

| Calcium channel blocker therapy | 35% | 28% | 44% | <0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 60% | 100% | 0% | N/A |

| Diuretic | 12% | 12% | 12% | 0.97 |

| Aspirin/antiplatelet | 91% | 92% | 90% | 0.008 |

| Lipid lowering agent | 71% | 74% | 66% | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulant | 5% | 4% | 5% | 0.05 |

| Digoxin | 3% | 3% | 4% | 0.97 |

| Antiarrhythmic | 2% | 1% | 3% | <0.001 |

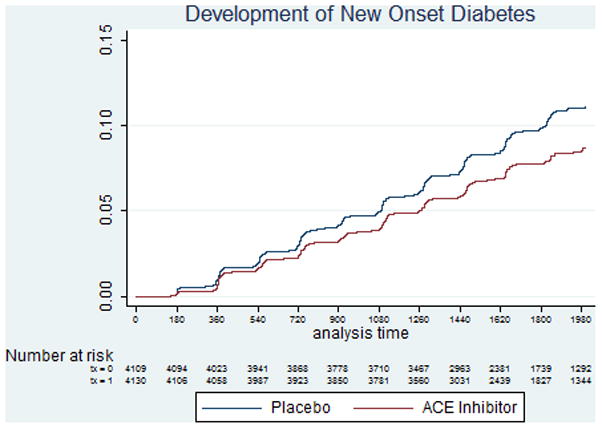

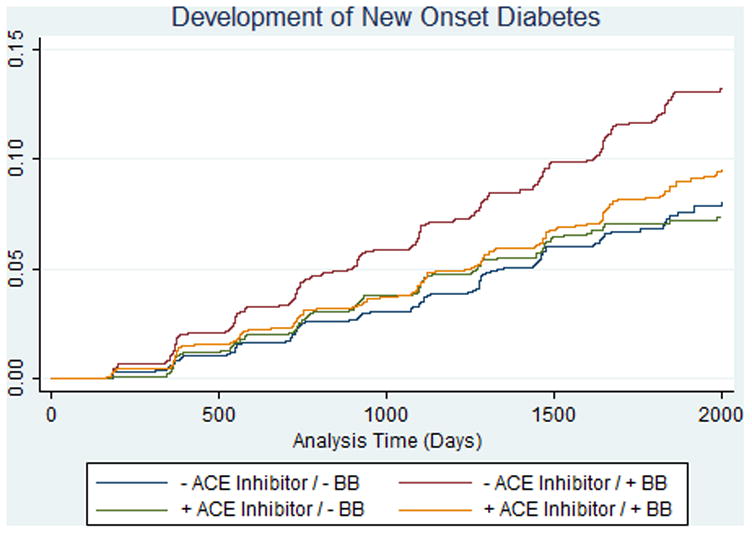

There were 733 cases of NOD reported over the trial follow-up time of 4.8 years (event rate 2.0%/year). Randomization to trandolapril was associated with a 17% reduction of the risk for development of NOD (Hazard ratio 0.83, 95% confidence interval 0.71, 0.95, p=0.009) as previously reported (Figure 2). In univariate analyses, beta-blocker use was associated with a 44% increased overall risk for development of NOD (HR 1.44, 95% confidence interval 1.23, 1.68; p<0.001), and remained associated with an increased risk for NOD after adjustment for baseline covariates and randomized treatment (HR 1.36, 95% confidence interval 1.15, 1.61). We observed a significant interaction between treatment assignment to trandolapril and the use of beta blockers on NOD in both univariate (p-interaction = 0.021) and multivariable adjusted models (p-interaction = 0.028); participants taking beta-blockers assigned to the placebo group (N=2090) had an adjusted increased risk for NOD (HR 1.63, 95% confidence interval 1.29, 2.05, p<0.001, figure 3), while this risk was attenuated in those assigned to trandolapril (N=2057) (HR 1.11, 95% confidence interval 0.87, 1.42; p=0.39). Adjusted analyses in which beta-blocker use throughout the trial were included as time-dependent covariates yielded qualitatively similar results (placebo group: HR 1.40, 95% confidence interval 1.12, 1.75; trandolapril group: HR 1.02, 95% confidence interval 0.81, 1.29). Propensity adjusted analyses yielded similar results (trandolapril group, HR 1.59, 95% confidence interval 1.26, 2.00; placebo group, HR 1.06, 95% confidence interval 0.83, 1.34). Additional predictors of NOD in adjusted models are shown in Table 2. The results from discrete-time proportional hazards models (not shown) were similar to those from the standard Cox’s regression models reported above.

Figure 2.

Development of New Onset Diabetes (NOD) in patients assigned to trandolapril and placebo.

Figure 3.

Risk for new onset diabetes (NOD) by beta-blocker and randomization to ACE inhibitor. Interaction p-value = 0.03.

Table II.

Other confounders that predict New Onset Diabetes, ordered by strength of multivariable association.

| Variable | Univariate HR (95% confidence interval) | Multivariable HR (95% confidence interval) | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index (per kg/m2) | 1.1 (1.09, 1.11) | 1.1 (1.08, 1.09) | 13.3 |

| Beta blocker | 1.44 (1.24, 1.68) | 1.56 (1.24, 1.95) | 3.83 |

| Seated systolic blood pressure (per mmHg) | 1.01 (1.0, 1.01) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.01) | 2.96 |

| Use of lipid lowering agents | 0.8 (0.67, 0.94) | 0.81 (0.69, 0.97) | 2.26 |

| Use of potassium sparing diuretics | 1.8 (1.29, 2.54) | 1.51 (1.06, 2.18) | 2.25 |

| Use of other diuretics | 1.52 (1.22, 1.9) | 1.24 (0.98, 1.57) | 1.8 |

| Seated diastolic blood pressure (per mmHg) | 1.0 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.0) | 1.74 |

| History of Coronary Disease on Angiography | 1.32 (1.13, 1.54) | 1.16 (0.98, 1.37) | 1.73 |

| Use of aspirin or antiplatelet | 0.94 (0.73, 1.2) | 0.81 (0.6, 1.07) | 1.46 |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society functional class | 1.18 (1.07, 1.3) | 1.08 (0.97, 1.2) | 1.43 |

| History of percutaneous transluminal coronary arterioplasty | 0.98 (0.84, 1.13) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.05) | 1.36 |

| Use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 0.83 (0.72, 0.96) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.34) | 1.34 |

DISCUSSION

We found that in patients with stable coronary artery disease, use of beta blockers was associated with an increased risk for development of NOD in traditional, propensity adjusted, and time-dependent analyses. Moreover, we observed a significant interaction between ACE inhibitor treatment assignment and beta blocker use with respect to NOD risk, such that the risk for NOD associated with beta-blockers was attenuated in participants randomized to ACE inhibitor.

Prior studies have raised concern that beta blockers contribute to the risk of NOD.1,2,14–17 We found that beta blocker use was associated with increased risk of NOD in univariate analyses, an effect that was minimally changed following traditional multivariable or propensity score adjustment. These results are similar to those observed in other studies, including the ASCOT-BPLA study1 comparing combination of beta blocker (atenolol) plus a thiazide diuretic to an ACE inhibitor plus dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker in high risk hypertensive individuals, in which the atenolol-based regimen was associated with a 30% higher incidence of development of diabetes compared to the amlodipine-based regimen. Similarly, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study reported a 28% increased likelihood of developing diabetes in patients taking a beta blocker.14 Nonselective (β1/β2) blockade by conventional beta blockers leads to unopposed α1-mediated vasoconstriction, thereby reducing blood flow to muscles and glucose uptake in peripheral tissues.18 Beta blockers also interfere with β2 mediated pancreatic insulin release.3,19,20 Additionally, reduced insulin release and blockade of hepatic β2 adrenergic receptors elevates glucose production following meals.4 Beta-blockers have also been shown to increase weight,21 which is associated with development of diabetes.

Several studies have shown that not all beta blockers negatively affect glucose metabolism. Carvedilol is thought to have neutral or even beneficial effects on insulin resistance. The GEMINI study randomized patients with diabetes and hypertension to receive metoprolol tartrate or carvedilol.22 Carvedilol did not worsen HbA1c, improved insulin resistance, and slowed the development of microalbuminuria compared with metoprolol. In a post-hoc analysis of the COMET trial, a study in heart failure patients that examined the effect of metoprolol tartrate and carvedilol on mortality, metoprolol was associated with a 20% increased risk for new onset diabetes compared to carvedilol.23 We do not have data about specific beta blocker use in the PEACE trial, and as such cannot comment on whether certain beta blockers conferred a higher risk for NOD in this cohort.

Numerous post-hoc analyses of clinical trials data have suggested that inhibitors of the RAAS may have beneficial effects on glycemic control. These include the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) 24, in which captopril therapy was associated with a 14% reduction in development of diabetes compared with conventional therapies, and the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study25 in which ramipril was associated with a 34% risk reduction in the development of diabetes.5 In contrast, the DREAM trial,7 which was prospectively designed to test this hypothesis, showed minimal difference in new onset diabetes between patients receiving ramipril versus placebo, although patients receiving ramipril were more likely to have regression to normoglycemia. Of note, the use of beta-blockers in the DREAM population was only 17%, which was substantially lower than in PEACE and HOPE. That ACE inhibitors might demonstrate some benefit with regard to glycemic control is not inconsistent with the results of DREAM, which did show a benefit with respect to glycemic control. ACE inhibitors may reduce vasoconstrictive and pro-fibrotic actions of angiotensin II in the pancreas, thus protecting pancreatic vasculature and beta cells,26 and may also improve insulin sensitivity through increased blood flow to skeletal muscle, while kinin accumulation resulting from ACE inhibition may also improve hemodynamics and augment glucose utilization.27

While our data suggest that ACE inhibitors may attenuate the increased risk of NOD associated with beta-blockers, in PEACE the benefit of the ACE inhibitor with respect to NOD appears essentially limited to those patients taking beta-blockers. Prior studies that have demonstrated a reduction in NOD associated with ACE inhibitors have not reported whether this benefit was limited to patients taking beta-blockers. We cannot determine from these hypothesis-generating data whether this attenuation is simply due to opposing effects or indicates a more complex interaction between beta-blocker and ACE inhibitor use. Nevertheless, these disparate effects of beta blockers and ACE inhibitors may provide a compelling rationale for combination use in patients with coronary disease requiring beta-blocker therapy. Similarly, trials of angiotensin receptor blockers have also reported a reduction in NOD,28,29 but whether ARBs attenuate the effects of beta blockers on NOD has not been reported. These data may be relevant in a high risk population of patients taking multiple medications who are potentially at risk for development of diabetes.

This study has several limitations. The determination of NOD was made only on the basis of patient report at baseline and 6-month visits, and not confirmed with laboratory testing, a limitation of the data collected in this multicenter clinical trial. Unfortunately, the PEACE study consent forms do not allow for contact with study participants or for collecting additional data in retrospect. Nevertheless, this endpoint was assessed prospectively at study visits, an advantage over other studies in which the identification of NOD was made only if reported. Moreover, fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels were not available and we thus could not adjust our statistical models for this variable, which has been shown to be associated with development of NOD.30

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Dr. Vardeny was supported by NIH-NCRR 1KL2RR025012; The PEACE Trial was funded by the NHLBI.

Industry disclosures: None

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers DG, Caulfield M, Collins R, Kjeldsen SE, Kristinsson A, McInnes GT, Mehlsen J, Nieminen M, O’Brien E, Ostergren J. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barzilay JI, Davis BR, Cutler JA, Pressel SL, Whelton PK, Basile J, Margolis KL, Ong ST, Sadler LS, Summerson J. Fasting glucose levels and incident diabetes mellitus in older nondiabetic adults randomized to receive 3 different classes of antihypertensive treatment: a report from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(20):2191–2201. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudbjornsdottir S, Fowelin J, Elam M, Attvall S, Bengtsson BA, Marin P, Lonnroth P. The effect of metoprolol treatment on insulin sensitivity and diurnal plasma hormone levels in hypertensive subjects. European journal of clinical investigation. 1997;27(1):29–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.670617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groop LC, Bonadonna RC, DelPrato S, Ratheiser K, Zyck K, Ferrannini E, DeFronzo RA. Glucose and free fatty acid metabolism in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Evidence for multiple sites of insulin resistance. J Clin Investl. 1989;84(1):205–213. doi: 10.1172/JCI114142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S, Gerstein H, Hoogwerf B, Pogue J, Bosch J, Wolffenbuttel BH, Zinman B. Ramipril and the development of diabetes. Jama. 2001;286(15):1882–1885. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vermes E, Tardif JC, Bourassa MG, Racine N, Levesque S, White M, Guerra PG, Ducharme A. Enalapril decreases the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: insight from the Studies Of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trials. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2926–2931. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072793.81076.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosch J, Yusuf S, Gerstein HC, Pogue J, Sheridan P, Dagenais G, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lanas F, Probstfield J, Fodor G, Holman RR. Effect of ramipril on the incidence of diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355(15):1551–1562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uehara M, Kishikawa H, Isami S, Kisanuki K, Ohkubo Y, Miyamura N, Miyata T, Yano T, Shichiri M. Effect on insulin sensitivity of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors with or without a sulphydryl group: bradykinin may improve insulin resistance in dogs and humans. Diabetologia. 1994;37(3):300–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00398058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Corradi L, Lazzari P, Mugellini A, Lusardi P. Comparative effects of lisinopril and losartan on insulin sensitivity in the treatment of non diabetic hypertensive patients. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1998;46(5):467–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind L, Berne C, Pollare T, Lithell H. Metabolic effects of anti-hypertensive treatment with nifedipine or furosemide: a double-blind, cross-over study. Journal of human hypertension. 1995;9(2):137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giugliano D, Acampora R, Marfella R, De Rosa N, Ziccardi P, Ragone R, De Angelis L, D’Onofrio F. Metabolic and cardiovascular effects of carvedilol and atenolol in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and hypertension. A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine. 1997;126(12):955–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braunwald E, Domanski MJ, Fowler SE, Geller NL, Gersh BJ, Hsia J, Pfeffer MA, Rice MM, Rosenberg YD, Rouleau JL. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351(20):2058–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer MA, Domanski M, Rosenberg Y, Verter J, Geller N, Albert P, Hsia J, Braunwald E. Prevention of events with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition (the PEACE study design). Prevention of Events with Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition. The American journal of cardiology. 1998;82(3A):25H–30H. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gress TW, Nieto FJ, Shahar E, Wofford MR, Brancati FL. Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;342(13):905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH. A meta-analysis of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with beta blockers to determine the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus. The American journal of cardiology. 2007;100(8):1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornley-Brown D, Wang X, Wright JT, Jr, Randall OS, Miller ER, Lash JP, Gassman J, Contreras G, Appel LJ, Agodoa LY, Cheek D. Differing effects of antihypertensive drugs on the incidence of diabetes mellitus among patients with hypertensive kidney disease. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(7):797–805. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.7.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott WJ, Meyer PM. Incident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369(9557):201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lithell H, Pollare T, Berne C, Saltin B. The metabolic and circulatory response to beta-blockade in hypertensive men is correlated to muscle capillary density. Blood pressure. 1992;1(1):20–26. doi: 10.3109/08037059209065120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nonogaki K. New insights into sympathetic regulation of glucose and fat metabolism. Diabetologia. 2000;43(5):533–549. doi: 10.1007/s001250051341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Struthers AD, Murphy MB, Dollery CT. Glucose tolerance during antihypertensive therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 1985;7(6 Pt 2):II95–101. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.6_pt_2.ii95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messerli FH, Bell DS, Fonseca V, Katholi RE, McGill JB, Phillips RA, Raskin P, Wright JT, Jr, Bangalore S, Holdbrook FK, Lukas MA, Anderson KM, Bakris GL. Body weight changes with beta-blocker use: results from GEMINI. The American journal of medicine. 2007;120(7):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakris GL, Fonseca V, Katholi RE, McGill JB, Messerli FH, Phillips RA, Raskin P, Wright JT, Jr, Oakes R, Lukas MA, Anderson KM, Bell DS. Metabolic effects of carvedilol vs metoprolol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;292(18):2227–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torp-Pedersen C, Metra M, Charlesworth A, Spark P, Lukas MA, Poole-Wilson PA, Swedberg K, Cleland JG, Di Lenarda A, Remme W, Scherhaug A. Effects of metoprolol and carvedilol on preexisting and new on-set diabetes in patients with chronic heart failure {inverted exclamation}V data from the Carvedilol or metoprolol European Trial (COMET) Heart. 2007 doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.092379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Niskanen L, Lanke J, Hedner T, Niklason A, Luomanmaki K, Dahlof B, de Faire U, Morlin C, Karlberg BE, Wester PO, Bjorck JE. Effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition compared with conventional therapy on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension: the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9153):611–616. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;342(3):145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tikellis C, Wookey PJ, Candido R, Andrikopoulos S, Thomas MC, Cooper ME. Improved islet morphology after blockade of the renin- angiotensin system in the ZDF rat. Diabetes. 2004;53(4):989–997. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henriksen EJ, Jacob S. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and modulation of skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2003;5(4):214–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Ibsen H, Kristiansson K, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359(9311):995–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusuf S, Ostergren JB, Gerstein HC, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Olofsson B, Probstfield J, McMurray JV. Effects of candesartan on the development of a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112(1):48–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.528166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haffner SM. The prediabetic problem: development of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and related abnormalities. Journal of diabetes and its complications. 1997;11(2):69–76. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(96)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]