Abstract

Despite the accumulation of sequence information sampling from a broad spectrum of phyla, newly sequenced genomes continue to reveal a high proportion (50%–30%) of “uncharacterized” genes, including a significant number of strictly “orphan” genes, i.e., putative open reading frames (ORFs) without any resemblance to previously determined protein-coding sequences. Most genes found in databases have only been predicted by computer methods and have never been experimentally validated. Although theoretical evolutionary arguments support the reality of genes when homologs are found in a variety of distant species, this is not the case for orphan genes. Here, we report the direct reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay of 25 strictly orphan ORFs of Escherichia coli. Two growth conditions, exponential and stationary phases, were tested. Transcripts were identified for a total of 19 orphan genes, with 2 genes found to be expressed in only one of the two growth conditions. Our results suggest that a vast majority of E. coli ORFs presently annotated as “hypothetical” correspond to bona fide genes. By extension, this implies that randomly occurring “junk” ORFs have been actively counter selected during the evolution of the dense E. coli genome.

Following the pioneering whole genome shotgun sequencing of Haemophilus influenzae (Fleischmann et al. 1995), bacterial genomes have accumulated steadily in public databases (see www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/). The sequence universe of gram-proteobacteria is well represented with two complete genomes for the gamma subdivision (H. influenzae. and Escherichia coli (Blattner et al. 1997)), one for the alpha subdivision (Rickettsia prowazekii (Andersson et al. 1998)), one for the beta subdivision (Neisseria meningitidis [Parkhill et al. 2000a; Tettelin et al. 2000]), and two for the epsilon subdivision (Helicobacter pylori [Tomb et al. 1997; Alm et al. 1999] and Campylobacter jejuni [Parkhill et al. 2000b]).

Gram-positive bacteria are also well sampled by four complete firmicute genomes (Bacillus subtilis, [Kunst et al. 1997] Mycobacterium tuberculosis, [Cole et al. 1998] Mycoplasma genitalium, [Fraser et al. 1995] and Mycoplasma pneumoniae [Himmelreich et al. 1996]), two spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi [Fraser et al. 1997] and Treponema pallidum [Fraser et al. 1998]), and several Chlamydia species and strains (Stephens et al. 1998; Kalman et al. 1999; Read et al. 2000).

The whole genomic sequences of Deinococcus radiodurans (White et al. 1999), of the cyanobacteria Synechocystis (Kaneko et al. 1996), and of the two hyperthermophilic bacteria Aquifex aeolicus (Deckert et al. 1998) and thermotoga maritima (Nelson et al. 1999) complete an already broad survey of the eubacteria sequence universe. The two other kingdoms of life are represented, on one hand, by five completed genomes of hyperthermophilic archebacteria (Methanococcus, Methanobacterium, Archaeoglobus, Pyrococcus, and Aeropyrum ) (Bult et al. 1996; Klenk et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1997; Kawarabayasi et al. 1998; Kawarabayasi et al. 1999) and, on the other hand, by three eukaryote genomes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Mewes et al. 1997), Caenorhabditis elegans (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998), and Drosophila melanogaster (Adams et al. 2000).

Given this large body of sequence data sampling from the three main phyla and a wide variety of lifestyles (aerobic, anaerobic, intracellular, mesophilic, hyperthermophilic, etc.), it seems paradoxical that each newly sequenced genome continues to reveal a significant fraction of unknown genes. At the time of publication, the fraction of completely unassigned open reading frames (ORFs) (Blattner et al. 1997) were, for instance, 37% for E. coli, 43% for H. influenzae, 45% for Synechocystis, and 32% for M. genitalium. The corresponding figure for yeast is about 40% (Dujon et al. 1994). This trend is persisting in the latest deciphered genome of T. maritima where 46% of the ORFs are of unknown function (Nelson et al. 1999). Those numbers are close to the predicted 50% proportion of phylum specific genes made a while ago when the concept of ancient conserved regions was introduced on the basis of statistical arguments (Claverie 1993; Green et al. 1993).

The notion of “uncharacterized” genes is not simple, and depends on the details of the different protocols used to annotate the genomic sequence. In a first step, a computer analysis of the genomic sequence is used to delineate ORFs. There is no accepted standard protocol for the processing of genomic sequence into ORFs (“ORFing”). Different programs (Audic and Claverie 1998; Lukashin and Borodovsky 1998; Salzberg et al. 1999) can be used; different significance, size, or overlapping threshold can be applied; and variable levels of human supervision can be given. Once selected, ORFs are translated into putative protein sequences that are used to query available public databases for homology. Uncharacterized ORFs are those (1) bearing a significant similarity only with proteins of unknown function, or (2) exhibiting no significant similarity to any other real or hypothetical protein. Throughout this article, the latter category will be referred to as “orphan” genes. Like ORFing, homology searches and functional assignments also involve different programs, target databases, and empirical significance thresholds. The classification of genes into the uncharacterized and orphan categories is thus subject to change (Casari et al. 1995; Ouzounis et al. 1995; Fisher and Eisenberg 1999; Mackiewicz et al. 1999).

Although a large fraction of putative ORFs is not associated to any demonstrated protein or function, the fact that some of them could simply arise by chance is rarely, if ever, discussed. The average protein length is above 350 amino acids (1050 nucleotide-long ORF), and proteins shorter than 100 amino acids are rare. A minimal ORF size cutoff of 300 nucleotides is thus often used during genomic annotation. However, even if the probability for a 300-nucleotide-long random sequence to contain an ORF is low, this is yet expected to happen frequently (Fickett 1995; Claverie et al. 1997) within the two strands of a 4.6 million-bp genome such as E. coli. According to a simple Bernoulli model (with equal frequencies of A,T, C, and G), the numbers of expected random ORFs (starting with ATG) are about 200 with sizes ≥ 300, about 35 with sizes ≥ 400, and about 4 with sizes ≥ 500. Those numbers might become even higher for random models with more realistic (e.g. order 2– or 3– Markov models) nucleotide distributions (Fickett 1995). Potentially, nonphysiological random ORFs could thus represent 5% or more of the 4290 annotated ORFs in E. coli.

In the absence of a functional assignment, the identification of a homologous ORF (using its putative translation) in another organism is still a good support for the reality of a gene because the chance is small for a nonphysiological ORF to be conserved throughout evolution. The evidence is of course better if homologous sequences are found across evolutionary distant organisms or in several of them. Finding homologs only within the same bacterial genome (putative paralogs) is also positive evidence, albeit much weaker, because even random ORFs may get duplicated during evolution. However, the best candidates for being the result of chance (i.e., “junk” ORFs) are the truly orphan ORFs, the putative products of which do not exhibit any significant similarity to any other known sequences.

By using all sequence data currently available, we have reanalyzed the current annotation of the E. coli genome (Blattner et al. 1997) and identified 25 orphan ORFs in a very conservative manner (i.e., eliminating ORFs exhibiting even poorly significant similarity within the databases). The presence of a cognate transcript for each of these highly hypothetical ORFs was then tested by using a sensitive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay on mRNA extracted during the exponential and stationary phase of E. coli K-12 MG1655 growth on a rich medium. Reproducible evidence of transcription was found for 19 of these 25 orphan ORFs, 2 of them exhibiting differential expression. This experimental validation of strictly orphan ORFs strongly suggests that most of them are indeed biologically relevant and, by extension, that randomly occurring junk ORFs are virtually absent from the E. coli genome.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nineteen Orphan Genes Exhibit Evidence of Transcription

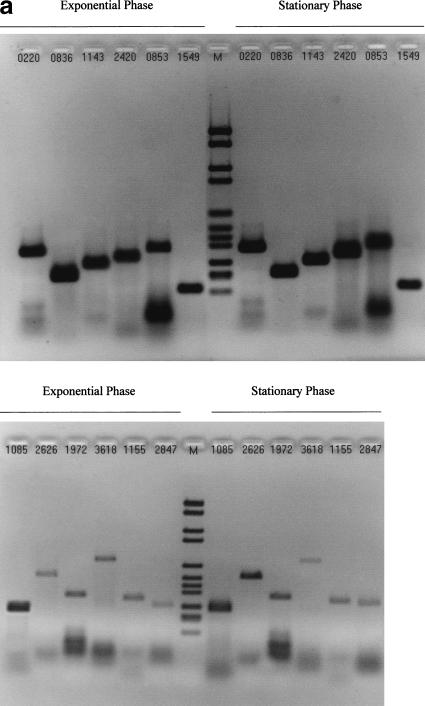

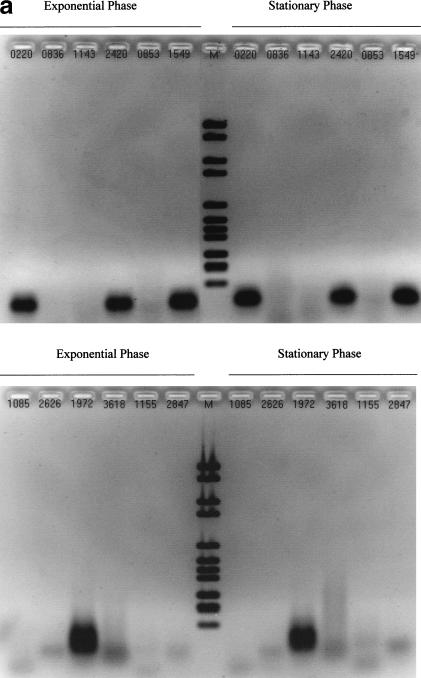

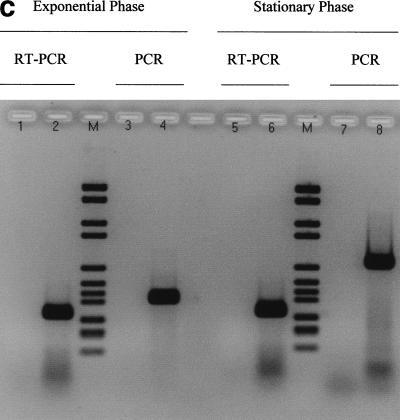

Figure 1 shows that amplicons were detected for 19 of the 25 orphan ORFs assayed by RT-PCR, by using the primer pairs listed in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the results of each control PCR experiment, as well as typical generic RT-PCR and PCR controls (Fig. 2c). The results are summarized in Table 1. Two ORFs, B0645 and B1668, showed qualitative evidence of differential expression. A B0645 transcript was detected only within total RNA from the exponential phase of growth, whereas B1668 mRNA was only detected in stationary phase. The 6 negative ORFs did not display any systematic difference in terms of their size, nucleotide composition, or amino-acid and repeat content of their putative translations.

Figure 1.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) experiments. The experiments have been replicated many times, allowing the tested open reading frames (ORFs) to be approximately ordered according to band intensities. (a) ORFs with high-intensity RT-PCR signals. (b) Top: ORFs with lower intensity signals, including differentially expressed B0645 and B1668; bottom: negative ORFs.

Table 1.

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Results and Primer Sequences

| ORFs | Amplicon size (bp) | RT-PCR | Sense primer | Antisense primer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.P. | E.P. | ||||

| B0220 | 381 | + | + | 45U21: GACAGTCGCCGCTCTGGTCAT | 405L21: GCCGCGAACAACACCGTTTTA |

| B0279 | 481 | − | − | 305U21: GCATCAATCGAAGCCGAGGTA | 766L20: TCTGTTTTGCGGAGCACTGG |

| B0358 | 445 | + | + | 17U21: TATTAGCGGCGGCCATTTTTA | 441L21: GTGATCACCGGGCCAGTATAG |

| B0364 | 270 | + | + | 14U21: CCGGCAACTCTGGCACAGATG | 263L21: TTCGGCAGGCAACCATTGAAG |

| B0558 | 276 | + | + | 75U20: CGATCAAGTGCGAAAAGATT | 332L19: CATCGGAAAACTCCTGCTT |

| B0645 | 438 | − | + | 244U21: TGTGAATGGCGTGACTATCTT | 661L21: TTCCGGGCATGCAGAATAGTA |

| B0648 | 620 | + | + | 66U21: TTGCAAACCCGCGCATGACTC | 664L22: GCGTTACCGGGCATTCAGACTG |

| B0836 | 234 | + | + | 107U21: TCAGCGAAAGCAATCATCTAC | 320L21: TCAGCGTTAAGCTCATCAGAC |

| B0853 | 376 | + | + | 46U21: CTCGATGACCTGGGGATGAGT | 401L21: ACAGCAGTTGATGGGCATTAG |

| B1085 | 282 | + | + | 5U18: CTAGTCGCGTCGCCAACC | 270L17: AGGCCGTTTCCGTGTCC |

| B1143 | 292 | + | + | 84U20: CACAGCCGAACAGACCAAAA | 356L20: CTTGATGGGCTTAGGCGTAA |

| B1155 | 346 | + | + | 60U21: TCCGCCAGATTCTAAAGAAAT | 385L21: CTGAACTGCCGGAGGCGTAGG |

| B1549 | 165 | + | + | 182U21: TAAAGGGCCTAAAAAACATTG | 326L21: TTTGTTCGTGGATATTTGTAA |

| B1668 | 502 | + | − | 966U21: ACAACGCGACCCATTTGACTG | 1449L19: CGCTACGCGCCCACGAATA |

| B1751 | 792 | + | + | 46U20: GCCTGGCGCTGTTTATTCTC | 818L20: TTCGGCGATTTTAAAGGTAA |

| B1972 | 367 | + | + | 165U20: GCTGGCGACCTTGTTAATCA | 512L20: GAGCGGCTGCGGTGAAATAA |

| B2420 | 327 | + | + | 394U21: AAAGAGCCGGATCTGGACTGT | 700L21: AAACGCCGTAAGGTCATCAAT |

| B2625 | 410 | − | − | 634U21: AGGAAAAACGAGCCCGAGAAA | 1023L21: GCCATGTTCTCCGCCATTTTA |

| B2626 | 536 | + | + | 64U21: ATTGATGACTCCCTAAACGAA | 581L19: TCTCCGTCACCGACTATTT |

| B2630 | 834 | − | − | 188U20: ACGGGGACGGTTCGACTACA | 1000L22: TCAACCGGGCCATATCAGAAAT |

| B2760 | 1123 | − | − | 114U21: GCCCCGTGACGATATGGAACT | 1214L23: TCCGGCCCCTTTGAAGTCTTTAT |

| B2847 S.P. | 331 | + | N.A. | 66U23: TAACGCCGATCTTAACGTCGTTC | 642L23: TCCCCGAATCCAGTATCCGTGTT |

| B2847 E.P. | 294 | N.A. | + | 371U23: ATGCCCCACCTGCCATAAAAGTT | 642L23: TCCCCGAATCCAGTATCCGTGTT |

| B3618 | 705 | + | + | 141U21: TCTGGCCGCACTTGAAAATGA | 825L21: GCCTGCATTTTTGCCCCTAAA |

| B3875 | 324 | − | − | 99U21: CTCCGATCAGGGCGAGGTTAT | 402L21: TCCAGTTCCCCGCTCAAATCT |

| B4215 | 455 | − | − | 33U23: TGGTGCGGTGGAGTTATTTGTAA | 465L23: CCAATCGCCTGGTGAATATAACC |

(ORF) Open reading frame; (E.P.) exponential phase; (S.P.) stationary phase.

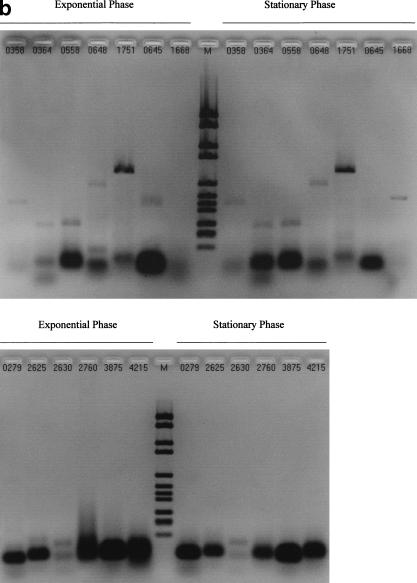

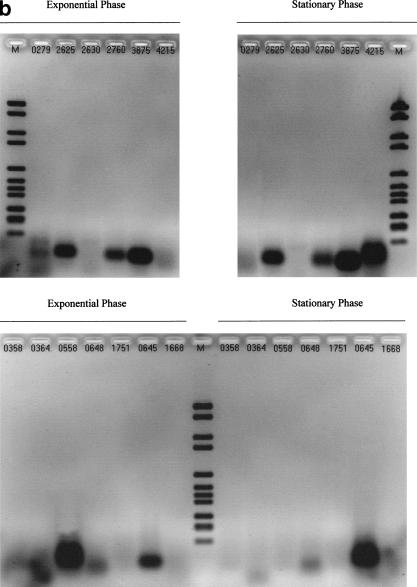

Figure 2.

Control experiments required to validate each of the results in Table 1. (a, b) Series of experiments corresponding to Figure 1, in absence of reverse transcriptase (RT) (no band expected). (c) Other RT-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and PCR reaction controls. (M) Molecular Weight Marker VI (Boehringer Mannheim). Validation of RT reactions using kanamycin mRNA (kit control): water instead of matrix with kanamycin primers (lanes 1 and 5) (no band expected), with kanamycin mRNA (lanes 2 and 6) (band expected). Validation of PCR reaction using MG1655 E. coli genomic DNA: water instead of matrix with rpoD primers (lane 3), or rpoS primers (lane 7) (no band expected), genomic DNA with rpoD primers (lane 4), or rpoS primers (lane 8) (band expected).

Among the negative ORFs, B2625, B2630, and B4215 belong to single-gene operons (as predicted in Thieffry et al. 1998). B0279 is the second ORF behind the putative DNA-binding protein (of unknown function) YagL, in a two-gene operon. B2760 is the first ORF of a seven-gene operon, all other ORFs of which are of unknown function. B3875 is the last ORF of a four-gene operon involving YihQ (a putative glycosidase), YihP, and YihO (two putative permeases). Among the 19 orphan ORFs for which transcription was detected, 11 are part of single-gene operons, and 8 are in different multi-gene operons. ORF B1085 is an interesting case. A putative Salmonella typhi (the sequencing of which is in progress; see NCBI unfinished microbial database) homolog of this ORF (85% identical at the amino-acid level) was revealed after the completion of this work. However, this apparent homolog has no valid start codon and exhibits an in-frame STOP codon. We can think of three hypotheses that might account for this situation: (1) We are looking at sequencing errors in the unfinished S. typhi sequence, (2) This B1085 homolog (perhaps not orthologous) is being lost in S. typhi, or (3) This ORF in fact corresponds to a functional RNA.

In a recent article, Richmond et al. (1999) used high-density arrays composed of full-length ORF-specific PCR products to examine the whole E. coli transcriptome response to isopropyl β-thio galactoside (IPTG) induction (as a control) or heat-shock treatment. None of the orphan genes tested here were mentioned as significantly involved in any of those responses. The data reported by Richmond et al. provided reliable measure of expression for only 25% of E. coli ORFs in batch culture at 37°C and consist of expression ratios that cannot easily be compared to our results. More recently, while our report was being prepared, Tao et al. (1999) published another study that used commercially available gene arrays. These results have been made available on a web site and consist of expression values in arbitrary units reflecting the mRNA level for each gene expressed in E. coli growing on minimal and/or rich media. The results of Tao et al. agree with our finding that a vast majority of the orphan genes selected are indeed expressed. Of the 25 ORFs listed in Table 1, 21 (84%) are detected in at least one of their growth conditions. In between the two studies, 23 of the 25 (92%) orphan genes that we selected (Table 1) are seen expressed in at least one of the tested condition (rich/minimal media, exponential/stationary phase). Finally, two of the ORFs (B0279 and B2760) that we failed to detect here also correspond to undetectable mRNA level according to Tao et al. data.

Promoter Sequence of the Stationary Phase-Specific ORF B1668

A central regulator of gene expression in stationary phase is the RNA polymerase ς38 factor encoded by the rpoS gene (Tanaka et al. 1993). This alternate sigma factor is thought to recognize a different subset of promoter sequences, although no clear consensus has been found associated to ς38-dependent genes. Site-directed mutagenesis has suggested that DNA sequence in the -35 region is involved in the discrimination between ς70- and ς38-dependent transcription. To analyze the upstream region of ORF B1668, we first collected the promoter sequences (encompassing the -10 and -35 regions) of 11 rpoS-dependent genes: osmY, osmB, fic, proP, aldB, bolA, xthA, glgS, poxB, cfa, and pexB (Wise et al. 1996). We generated optimal multiple alignments of these sequences by using ClustalW (Higgins et al. 1996). From this multiple alignment, a position-weight matrix (PWM) (defined over 38 positions) was generated by using the NMksite (Claverie and Audic 1996) program. This ς38 PWM was then used to scan the upstream region of ORF B1668. A statistically significant match (Claverie and Audic 1996) (P score < 0.01) was found, encompassing the −35 and −10 region of the putative promoter. In a control computer experiment, no significant match of the ς38 PWM was found in the upstream region of a selection of experimentally proven ς70-dependent promoters (alaS, dnaQ, leuX, rnaII, rnh, rplJ, rpsA, rrnE, tufB)(Tanaka et al. 1993). The ς38 recognition motif that we designed from genes previously known to be specific to the stationary phase is thus in agreement with the promoter sequence and expression behavior of ORF B1668.

Nonphysiological (Random) ORFs Are Rare

The present survey of all E. coli strictly orphan ORFs indicates that 19 of 25 (76%) (our study) belong to bona fide transcripts when tested in exponential growth and stationary phase. Merging our results with those of Tao et al. (1999) increases that estimate to 92%. This high rate of mRNA detection suggests that a large majority of ORFs of unknown function is of biological relevance. Indeed, this statement will remain speculative until evidence of protein products are given for all of these orphan ORFs, a work now being initiated in a structural genomic context. This also might come as a surprise if we think that the “normal” habitat of E. coli is anaerobic, whereas all of the tests described earlier were performed in aerobic conditions. This would indicate that only a small fraction of genes are specific for anaerobic growth.

However, our results are confirmed by a statistical survey of Tao et al. expression data as available on their web site (http://bomi.ou.edu/faculty/tconway/global.html). According to their database, 1352 ORFs are classified as hypothetical (including the 25 considered orphan by using our very relaxed similarity criteria; see Methods). Of these, we computed that 80% exhibited detectable mRNA levels in at least one of the two conditions tested. This figure becomes 86% when computed on all 4290 E. coli ORFs. This already indicates that hypothetical ORFs behave not much differently than genes for which functional attributes have been recognized. Our experimental results on orphan ORFs now indicate that hypothetical ORFs with no recognized similarity are not less likely to be transcribed than those with orthologs in other microbial genomes.

The fact that almost all ORFs annotated in the E. coli genome sequence appear to be real is, first, a tribute to the high-quality sequencing and annotation work of Blattner's laboratory (Blattner et al. 1997) as well as to that of Collado-Vides (Thieffry et al. 1998). In the current state of annotation, very little room is left for potentially unrecognized ORFs, and our analysis of orphans can in fact be considered comprehensive. We can thus conclude from our work that random ORFs (of which about 200 are expected of sizes ≥ 300 nucleotides) are virtually absent, and must have been actively selected against throughout the evolution of the E. coli genome. A strong selection pressure would then exist against the maintenance of nonphysiological ORFs in the genome of proteobacteria (with the exception of intracellular parasites such a R. prowazekii (Andersson et al. 1998)). The situation appears to be different in a unicellular eukaryote such as yeast, where up to 76% of annotated ORFs might not be expressed (Mackiewicz et al. 1999). The intolerance for fake ORFs in prokaryote genomes might be related to the direct coupling between transcription and translation that is characteristic of these organisms. It might also be related to a mode of evolution where horizontal gene transfer—allowing the acquisition at once of already functional genes—is important. In this context, orphan ORFs would simply have been acquired from yet unsequenced organisms or would have diverged beyond recognition. Eukaryotes, in contrast, seem to evolve new functions by gene duplication, followed by rapid pseudo-gene evolution and reactivation. Such an evolutionary pathway is clearly making junk ORFs a necessity.

METHODS

Sequence Analysis: Selection of Orphan ORFs

1393 E. coli ORF sequences annotated as unknown (as of January 1997) were selected from the genome site maintained by Blattner's laboratory (ftp.genetic.wisc.edu). Our purpose was not to validate this annotation but to estimate the percentage of likely junk ORFs among them. To select out the ultimate orphan genes, these hypothetical ORF sequences were further submitted to a comprehensive similarity search survey according to a very low stringency protocol. In the first step, all available complete bacteria and archebacteria genomes (downloaded locally) were scanned by using WU-BLAST 2.0 tblastx (Warren Gish, unpublished; Gish and States 1993). Default scoring matrix, filtering, and significance level (E=10) were used. The use of the similarity search program tblastx (putative translation of the query vs. putative translation of the target sequences in all reading frames) eliminated the risk of not recognizing a match due to ORF annotation errors in the query or target genomes. All ORFs with similarity matches were eliminated, including partial matches with interrupted ORFs in other bacteria. The remaining ORFs were further compared to the complete yeast genome by using the same protocol, and the matching ORFs were eliminated. Finally, the remaining ORFs were compared against the NR-protein database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by using BLAST 2.0 (Altschul et al. 1997). This succession of database searches resulted into an ultimate set of 31 orphan ORFs. None of the 181 ORFs shorter than 300 nucleotides that were present in the original set of 1393 unknown ORFs made it into the ultimate orphan ORF category. While this work was in progress, 6 of the 31 orphan candidates were further eliminated because of their similarity to newly available genomic sequences from S. typhi, S. Typhimurium,, Klebsiella pneumoniae,, and Clostridium perfringens. The list of the 25 orphan ORFs used in the experimental validation is given in Table 1, according to their original nomenclature (Blattner et al. 1997). These ORFs exhibit the same statistical bias (fifth-order Markov model) as do other protein-coding genes in E. coli and are indeed detected by the SelfID genome annotation program (Audic and Claverie, 1998).

Bacterial Growth, Isolation of Total RNA and DNAse I Treatment

E. coli K-12 (MG1655, obtained from Blattner's group) was grown in sterile Luria-Bertani (LB10) in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks, on a shaker (at 81 rpm and 150 rpm for the exponential and stationary phases, respectively) at 37°C. Cells were harvested after 5H (exponential phase) or 27H (stationary phase). For the exponential phase culture only, 25 mM of sodium azide and 192 μg/ml of chloramphenicol were added (Mahbubani et al. 1991), followed by a 10-min incubation at 37°C and 81-rpm shaking. Cultures were stopped by dropping the temperature to 0°C. Cells were pelleted (20 min, 4000 rpm) once, then resuspended twice in YM90 (1X) medium. Final pellets were finally resuspended in YM90 1X, aliquoted, and pelleted (10 min, 6500 rpm). After discarding the supernatant, the tubes were rapidly frozen at −80°C. For each experiment, total RNA from 5.108 bacteria (quantified on LB agar petri dishes) was isolated by using Qiagen RNeasy columns, strictly following the manufacturer's protocol. Nucleic acids were quantified by 260 nm/280 nm spectrophotometry. Contaminant bacterial DNA was eliminated by using the DNAse I kit from Gibco BRL. The total elution volume was digested by DNAse I at the concentration of 2UK/μg of total RNA. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the digestion was stopped by adding 2mM EDTA followed by incubation at 65°C for 10 min. A final purification with Qiagen RNeasy column was then performed.

Reverse Transcriptase and PCR Primer Design

PCR primer pairs were designed with the OLIGO 5.0 software (Medprobe) to amplify the transcript corresponding to each of the selected 25 orphan ORFs. The primers were chosen to be entirely contained within the putative protein-coding region. Primer pair sequences (from 19 to 23 nucleotides long) are given in Table 1, as well as their positions relative to the beginning of each ORF sequence. For instance, the sense primer for B0220 starts at position 45, is 21 nucleotides long, and is denoted 45U21. The reverse primer, denoted 405L21, is also 21 nucleotides long and starts at position 405. For each ORF, the antisense primer was used for the initial RT reaction, as well as for the following PCR cDNA amplification. In the case of ORF B2847, a different sense primer was required to remove the presence of a nonspecific band when using exponential phase total RNA. All primer pairs produced amplicons of the expected sizes when tested on E. coli K-12 (MG1655) genomic DNA.

RT-PCR Assay and Control PCR

RT-PCR assays were performed by using the one-step protocol (Aatsinki et al. 1994) as implemented in the Access kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions and optimizing the number of cycles to 35. Higher numbers of cycles (40, 45, and 60) led to nonreproducible results, most likely due to residual genomic DNA contamination. We used an MJ Research PTC 200 thermocycler. Each ORF was tested at least twice on the same total RNA batch. Contaminant DNA was removed by treatment with DNAse 1 as described earlier. RNA samples (0.1 μg of total RNA each) were simultaneously amplified with 35-cycle PCR, in presence versus absence of RT. The latter protocol tested for the eventual amplification of contaminant genomic DNA (see Fig. 2a,b). All of the results summarized in Table 1 correspond to experiments where amplicons were not observed in the absence of RT. In addition, a series of PCR control experiments that used independent primers was performed as shown in Figure 2c.

Amplicon Detection

Amplicons were detected by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels (2 hr, 100 V, in TAE [1X] buffer), followed by ethidium bromide (0.5 ug/ml) staining for 15 min at room temperature. Gels were then washed for 5 min in TAE buffer. Results were then visualized and recorded by using the Seikosha VP1500 Imager (Appligene). All amplicon sequences were verified by direct sequencing (Qiagen) by using the cognate RT-PCR primers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. V. Roux for precious technical advice and Prof. D. Raoult for kindly giving us access to its ‘contamination-free’ PCR laboratory. We thank Dr. P. Moreau for helpful discussions at the beginning of the project and Dr. C. Bartoli for her help with gel reading. Thanks are also due to Dr. C. Abergel, Prof. A. Lazdunski, Prof. D. Gautheret, and Dr. R.J. Roberts for helping improving the manuscript. This work was supported by the CNRS genome program.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL secr@igs.cnrs-mrs.fr ; FAX 33 4 91 16 45 49.

REFERENCES

- Aatsinki JT, Lakkakorpi JT, Pietila EM, Rajaniemi HJ. A coupled one-step reverse transcription PCR procedure for generation of full-length open reading frames. Biotechniques. 1994;16:282–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alm RA, Ling LS, Moir DT, King BL, Brown ED, Doig PC, Smith DR, Noonan B, Guild BC, deJonge BL, et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson SG, Zomorodipour A, Andersson JO, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Alsmark UC, Podowski RM, Naslund AK, Eriksson AS, Winkler HH, Kurland CG. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature. 1998;396:133–140. doi: 10.1038/24094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic S, Claverie JM. Self-identification of protein-coding regions in microbial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:10026–10031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G, 3rd, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, White O, Olsen GJ, Zhou L, Fleischmann RD, Sutton GG, Blake A, FitzGerald LM, Clayton RA, Gocayne JD, et al. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casari G, Andrade MA, Bork P, Boyle J, Daruvar A, Ouzounis C, Schneider R, Tamames J, Valencia A, Sander C. Challenging times for bioinformatics. Nature. 1995;376:647–648. doi: 10.1038/376647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie JM. A database of ancient protein sequences. Nature. 1993;364:19–20. doi: 10.1038/364019b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie JM, Audic S. The statistical significance of nucleotide position-weight matrix matches. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:431–439. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie JM, Poirot O, Lopez F. The difficulty of identifying genes in anonymous vertebrate sequences. Comput Chem. 1997;21:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0097-8485(96)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckert G, Warren PV, Gaasterland T, Young WG, Lenox AL, Graham DE, Overbeek R, Snead MA, Keller M, Aujay M, et al. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature. 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B, Alexandraki D, Andre B, Ansorge W, Baladron V, Ballesta JP, Banrevi A, Bolle PA, Bolotin-Fukuhara M, Bossier P, et al. Complete DNA sequence of yeast chromosome XI. Nature. 1994;369:371–378. doi: 10.1038/369371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickett JW. ORFs and genes: How strong a connection? J Comput Biol. 1995;2:117–123. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1995.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D, Eisenberg D. Finding families for genomic ORFans. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:759–762. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.9.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, Bult CJ, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Merrick JM, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, Adams MD, Clayton RA, Fleischmann RD, Bult CJ, Kerlavage AR, Sutton G, Kelley JM, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum KA, Dodson R, Hickey EK, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Norris SJ, Weinstock GM, White O, Sutton GG, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey EK, Clayton R, Ketchum KA, et al. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–388. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gish W, States DJ. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat Genet. 1993;3:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P, Lipman DJ, Hillier L, Waterston R, States D, Claverie JM. Ancient conserved regions in new gene sequences and the protein databases. Science. 1993;259:1711–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.8456298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li BC, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman S, Mitchell W, Marathe R, Lammel C, Fan J, Hyman RW, Olinger L, Grimwood J, Davis RW, Stephens RS. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Nat Genet. 1999;21:385–389. doi: 10.1038/7716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, et al. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayasi Y, Sawada M, Horikawa H, Haikawa Y, Hino Y, Yamamoto S, Sekine M, Baba S, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, et al. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyper-thermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 1998;5:55–76. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.2.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayasi Y, Hino Y, Horikawa H, Yamazaki S, Haikawa Y, Jin-no K, Takahashi M, Sekine M, Baba S, Ankai A, et al. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper- thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernix K1. DNA Res. 1999;6:83–101. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk HP, Clayton RA, Tomb JF, White O, Nelson KE, Ketchum KA, Dodson RJ, Gwinn M, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, et al. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini AM, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero MG, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashin AV, Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: New solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackiewicz P, Kowalczuk M, Gierlik A, Dudek MR, Cebrat S. Origin and properties of non-coding ORFs in the yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3503–3509. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.17.3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahbubani MH, Bej AK, Miller RD, Atlas RM, DiCesare JL, Haff LA. Detection of bacterial mRNA using polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques. 1991;10:48–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewes HW, Albermann K, Bahr M, Frishman D, Gleissner A, Hani J, Heumann K, Kleine K, Maierl A, Oliver SG, et al. Overview of the yeast genome. Nature. 1997;387(6632 Suppl):7–65. doi: 10.1038/42755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Clayton RA, Gill SR, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Nelson WC, Ketchum KA, et al. Evidence for lateral gene transfer between Archaea and bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature. 1999;399:323–329. doi: 10.1038/20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounis C, Bork P, Casari G, Sander C. New protein functions in yeast chromosome VIII. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2424–2428. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Achtman M, James KD, Bentley SD, Churcher C, Klee SR, Morelli G, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, et al. Complete DNA sequence of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis Z2491. Nature. 2000a;404:502–506. doi: 10.1038/35006655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Wren BW, Mungall K, Ketley JM, Churcher C, Basham D, Chillingworth T, Davies RM, Feltwell T, Holroyd S, et al. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature. 2000b;403:665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, Hickey EK, Peterson J, Utterback T, Berry K, et al. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond CS, Glasner JD, Mau R, Jin H, Blattner FR. Genome-wide expression profiling in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3821–3835. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg SL, Pertea M, Delcher AL, Gardner MJ, Tettelin H. Interpolated Markov models for eukaryotic gene finding. Genomics. 1999;59:24–31. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Doucette-Stamm LA, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, et al. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum deltaH: Functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, et al. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Takayanagi Y, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Takahashi H. Heterogeneity of the principal sigma factor in Escherichia coli: The rpoS gene product, sigma 38, is a second principal sigma factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:3511–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H, Bausch C, Richmond C, Blattner FR, Conway T. Functional genomics: Expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6425–6440. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6425-6440.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, Saunders NJ, Heidelberg J, Jeffries AC, Nelson KE, Eisen JA, Ketchum KA, Hood DW, Peden JF, Dodson RJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287:1809–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieffry D, Salgado H, Araceli MH, Collado-Vides J. Prediction of transcriptional regulatory sites in the complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:391–400. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White O, Eisen JA, Heidelberg JF, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Gwinn ML, Nelson WC, Richardson DL, et al. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Science. 1999;286:1571–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A, Brems R, Ramakrishnan V, Villarejo M. Sequences in the -35 region of Escherichia coli rpoS-dependent genes promote transcription by E sigma S. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2785–2793. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2785-2793.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]