Abstract

CD20 expression is associated with early recurrence and inferior survival in precursor-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with chemotherapy. Whether CD20 influences outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is unknown. We analyzed CD20 expression on blasts at diagnosis in 157 patients who underwent allo-HSCT in the first complete remission (57%) or the second complete remission (43%). Of 125 evaluable patients, 71 were ≥ 20 years of age. CD20 expression was observed in 58 patients (46%; 52% of children, 39% of adults). There was no association between age, Ph+ status, white blood cell count at diagnosis, and CD20 positivity. After allo-HSCT, disease-free survival at 5 years was 48% for all patients, 55% (95% confidence interval 40%-67%) for CD20+ patients, and 43% (95% confidence interval 30%-54%) for CD20− patients (P = .15). Relapse did not differ between the groups. These results can serve as a reference to evaluate incorporation of anti-CD20 therapeutics to HSCT for the CD20+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia subset. Clinical trial numbers for www.clinicaltrials.gov are NCT00365287, NCT00305682, and NCT00303719.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is often used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1 For most adult ALL, allo-HSCT is considered as part of postremission consolidation. As shown in the landmark prospective clinical trial by Goldstone et al,2 allo-HSCT performed in the first complete remission (CR1) for standard and high-risk ALL reduced the relapse rate by 50% compared with chemotherapy, yielding a 40%-50% survival rate. Conversely, for pediatric ALL, chemotherapy alone has increased the cure rate to nearly 80%.3 Allo-HSCT is performed in children with very high risk in CR1 (severe hypodiploidy and primary induction failure) and is mainly reserved for patients with early recurrence who achieve a second complete remission (CR2).4 To further improve outcomes, the investigators are exploring targeted chemotherapeutics and monoclonal antibodies.5,6 In this context, approximately 40% of precursor-B ALL (pre-B ALL) cases express CD20.7 CD20 expression has prognostic implications because adult patients with CD20+ ALL have a shorter duration of complete remission and inferior 3-year overall survival (OS) compared with CD20− patients (49% versus 61%) when treated with hyper-cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone (HyperCVAD) or VAD chemotherapy.7 Similarly, the Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL)8 demonstrated CD20 expression to be an independent negative prognostic factor for relapse (1.9-fold increase), resulting in shorter disease-free survival (DFS) in Ph− ALL patients with high white blood cell counts. That study also suggested that relapses remained frequent in CD20+ patients despite HSCT; however, patient numbers were small. Some nontransplantation studies in childhood leukemia have yielded similar worrisome findings; the largest report on > 1000 cases noted an inferior event-free survival for CD20+ ALL.9,10

To date, it is unknown whether CD20 expression at diagnosis influences allo-HSCT results. We therefore investigated the impact of CD20 expression on outcomes after allo-HSCT in adult and pediatric pre-B ALL. Similar data have not been reported, and our findings are of value in planning future trials incorporating CD20-directed therapy into HSCT strategies.

Methods

Using prospectively collected data from the University of Minnesota Blood and Marrow Transplantation Database, we identified 157 consecutive pre-B ALL patients who underwent allo-HSCT in CR1 (high-risk patients with Ph+, MLL-AF4, white blood cell count > 30 000/μL, age ≥ 35 years) or CR2 between 1999 and 2009. CD20 expression did not influence patient selection for transplantation. One hundred twenty-five evaluable patients had diagnostic flow cytometry files available for review. CD20 expression was assessed by multiparameter flow cytometry with 4- or 8-color analysis with anti-CD20 clone L27 (Becton Dickinson) labeled with PE or APC-H7. The blast population was identified by CD45 gating, and analysis was performed with FCS Express software (De Novo Software). Thirty-two patients without CD20 staining were excluded. In accordance with prior studies, a predetermined cutoff of 20% CD20 expression was used to classify positive and negative cases.7 Median post-HSCT follow-up among survivors was 1473 (range 145-4035) days.

Transplantation protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota institutional review board, and all patients gave written informed consent for treatment and prospective data collection in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The myeloablative conditioning regimen included cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg × 2 days) and total body irradiation (TBI 165 centigray twice a day for 4 days) followed by cyclosporine and a short course of methotrexate.11 For umbilical cord blood HSCT, cyclophosphamide/TBI plus fludarabine 25 mg/m2 × 3 days was used.12 Reduced-intensity conditioning consisted of TBI (200 cGy)/fludarabine (40 mg/m2 × 5 days) plus cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg × 1 day) or busulfan (n = 1).13 All reduced-intensity conditioning and all umbilical cord blood HSCT patients received cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil as reported previously.12,13

Comparisons between CD20+ and CD20− ALL cases were performed with a nonparametric Wilcoxon test for continuous factors and Pearson χ2 test for categorical factors. All patients were followed up longitudinally until death or last follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier procedure was used to estimate OS and DFS, which were compared by log-rank test.14 Cumulative incidence was used to estimate relapse, transplant-related mortality, and GVHD.15 The proportional hazards model of Fine and Gray was used to assess factors associated with relapse.

Results and discussion

The median age of all patients was 27 (range 0.6-66) years; 52 (42%) were children < 20 years of age. All patients were in complete remission at allo-HSCT (53% in CR1, 47% in CR2; Table 1). Fifty-eight patients had > 20% CD20 expression (CD20+ group) compared with 67 with < 20% CD20 expression (CD20− group). Approximately half of the children (52%) and adults (39%) were CD20+, and the distribution of CD20+ cases was similar for patients in CR1 and CR2. There was no significant association between CD20+ and other high-risk features such as age, Ph+ status, or white blood cell count at diagnosis. Consistent with prior reports, none of the patients with MLL-AF4 gene rearrangements expressed CD20.10

Table 1.

Patients and transplant characteristics according to CD20 expression

| Factors | No. of patients (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD20-negative | CD20-positive | ||

| Total | 67 | 58 | |

| Age group, y | .37 | ||

| Younger than 10 | 15 (22) | 22 (38) | |

| 10 < 20 | 9 (13) | 8 (14) | |

| 20 < 40 | 20 (30) | 13 (23) | |

| 40 < 50 | 12 (18) | 6 (10) | |

| Older than 50 | 11 (16) | 9 (16) | |

| Year of transplant | .62 | ||

| 1999-2002 | 17 (25) | 19 (33) | |

| 2003-2009 | 50 (75) | 39 (67) | |

| Gender | .36 | ||

| Male | 39 (58) | 29 (50) | |

| Female | 28 (42) | 29 (50) | |

| Remission status at HSCT | .45 | ||

| CR1 | 38 (57) | 29 (50) | |

| CR2 | 29 (43) | 29 (50) | |

| Patient CMV serostatus | .12 | ||

| Negative | 28 (43) | 32 (57) | |

| Positive | 37 (57) | 24 (43) | |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| BCR/ABL–positive | 29 (43) | 25 (43) | .90 |

| MLL-AF4–positive | 10 (14) | 0 | .01 |

| Other cytogenetic groups | .13 | ||

| Complex | 5 (8) | 5 (9) | |

| Hyperdiploid | 5 (8) | 3 (5) | |

| Hypodiploid | 4 (6) | 3 (5) | |

| Normal karyotype | 6 (9) | 11 (19) | |

| del 9p | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Other | 4 (6) | 4 (7) | |

| Not available | 3 (4) | 5 (9) | |

| White blood cell count | |||

| Less than 30 000/μL | 32 (51) | 25 (48) | .77 |

| More than or equal to 30 000/μL | 31 (43) | 27 (52) | |

| Donor source | .45 | ||

| HLA matched, related | 22 (33) | 24 (41) | |

| Umbilical cord blood | 43 (64) | 31 (53) | |

| HLA matched, unrelated | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | |

| Conditioning intensity | .40 | ||

| Myeloablative | 54 (81) | 50 (86) | |

| Reduced intensity | 13 (19) | 8 (14) | |

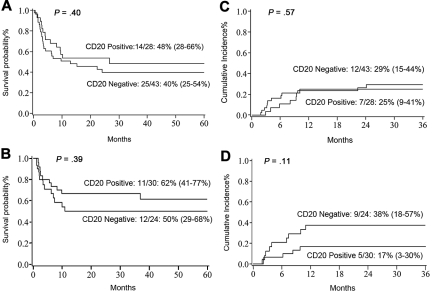

At 5 years, DFS and OS for all patients were 48% (95% confidence interval [CI] 39%-57%) and 47% (95% CI 37%-56%), respectively. For CD20+ patients, DFS was 55% (95% CI 40%-67%), and for CD20− patients, it was 43% (95% CI 30%-54%; P = .15). For adults, the 5-year DFS was not impacted by CD20 expression (CD20+ 48% [95% CI 28%-66%] versus CD20− 40% [95% CI 25%-54%]; P = .4; Figure 1A). Five-year DFS in childhood ALL (n = 54) was also equivalent between CD20+ (62% [95% CI 41%-77%]) and CD20− (50% [95% CI 29%-68%]; P = .39; Figure 1B) cohorts. The cumulative incidence of leukemia relapse was 27% (95% CI 19%-35%) and was nearly identical in adult and pediatric ALL (28% and 26%, respectively). We observed no statistically significant difference in relapse by CD20+ expression in adults (CD20+ 25% [95% CI 9%-41%] versus CD20− 29% [95% CI 15%-44%]; P = .57; Figure 1C). For children, the 3-year relapse rate was not affected by CD20 expression (CD20+ 17% [95% CI 3%-30%] versus CD20− 38% [95% CI 18%-57%]; P = .11; Figure 1D). For children with the MLL-AF4 rearrangement, the relapse rate was 60% [95% CI 21%-99%]. Notably, the median time to relapse in CD20− patients was 4 months (1.94-24.11 months) compared with 7 months (2.13-10.15 months; P = .47) in the CD20+ cohort. The cumulative incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD at day 100 in CD20− and CD20+ cohorts was similar (43% versus 38%, respectively), as were 1-year chronic GVHD rates (21% versus 24%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Transplant outcomes. (A) Five-year DFS in adults with pre-B ALL. (B) Five-year DFS in pediatric patients with pre-B ALL. (C) Three-year relapse rate in adults. (D) Three-year relapse rate in pediatric patients.

In adjusted multivariate regression, the most significant factor associated with inferior survival was remission status at HSCT. Patients in CR2 had a 2.8-fold higher risk of relapse (95% CI 1.2-6.53; P = .02) and lower OS (relative risk 4.4 [95% CI 1.74-11.16]; P = .01), particularly when CR1 duration was < 1 year. Neither CD20 expression, conditioning intensity, recipient CMV serostatus, donor type, or presence of BCR-ABL1 translocation significantly influenced DFS or OS. There was no difference in transplant-related mortality by CD20 expression (CD20+ 18% [95% CI 9%-27%] versus 19% [95% CI 9%-29%; P = 0.9). Adults had a 2.42-fold (95% CI 0.86-6.77; P = .09) higher risk of transplant-related mortality compared with children.

Because CD20 expression in ALL blasts has been reported to be an important prognostic indicator, we examined a uniformly treated cohort of high-risk pre-B ALL allo-HSCT recipients. We found that CD20 expression was not associated with known adverse risk features, nor did CD20 expression impact the post-HSCT relapse rate or OS. Irrespective of CD20 expression, allo-HSCT yielded promising long-term DFS.

The results suggest that transplantation may overcome the adverse prognostic impact of CD20 expression in both adult and pediatric ALL. For patients with CD20+ ALL with or without other high-risk features, a treatment strategy that incorporates rituximab-containing induction chemotherapy may be of benefit.6 The present data offer a reference for outcomes according to CD20 expression, specifically to compare future HSCT trials that may incorporate anti-CD20 strategies. Analogous to tyrosine-kinase inhibitors in Ph+ ALL, the incorporation of monoclonal antibodies that target CD20 may further improve HSCT outcomes in CD20+ ALL.16

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health P30 CA77598 using the Biostatistics and Informatics Core, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota shared resource. The authors thank Michael Franklin and Carol Taubert for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: V.B. designed the study, collected and verified patient information, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; K.S. collected clinical and immunophenotypic data; S.Y. reviewed flow cytometry files and collected information on CD20 expression; Q.C. collected and analyzed data and performed statistical analysis; M.J.B. and M.R.V. contributed to the data collection for pediatric patients, assisted with interpretation, and assisted in writing the manuscript; and D.W. designed research, interpreted data, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Veronika Bachanova, MD, Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, University of Minnesota, Mayo Mail Code 480, 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: bach0173@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Weisdorf D, Forman S. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;144:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78580-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008;111(4):1827–1833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Kaatsch P, Burkhardt-Hammer T, Harms DO, Schrappe M, Michaelis J. Long-term survival of children with leukemia achieved by the end of the second millennium. Cancer. 2001;92(7):1977–1983. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011001)92:7<1977::aid-cncr1717>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn T, Wall D, Camitta B, et al. The role of cytotoxic therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children: an evidence-based review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(11):823–861. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claviez A, Eckert C, Seeger K, et al. Rituximab plus chemotherapy in children with relapsed or refractory CD20-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2006;91(2):272–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas DA, O'Brien S, Faderl S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with a modified hyper-CVAD and rituximab regimen improves outcome in de novo Philadelphia chromosome-negative precursor B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(24):3880–3889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas DA, O'Brien S, Jorgensen JL, et al. Prognostic significance of CD20 expression in adults with de novo precursor B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(25):6330–6337. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maury S, Huguet F, Leguay T, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of CD20 expression in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95(2):324–328. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.010306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borowitz MJ, Shuster J, Carroll AJ, et al. Prognostic significance of fluorescence intensity of surface marker expression in childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Blood. 1997;89(11):3960–3966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworzak MN, Gaipa G, Schumich A, et al. Modulation of antigen expression in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction therapy is partly transient: evidence for a drug-induced regulatory phenomenon: results of the AIEOP-BFM-ALL-FLOW-MRD-Study Group. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2010;78(3):147–153. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomblyn MB, Arora M, Baker KS, et al. Myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: analysis of graft sources and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3634–3641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verneris MR, Brunstein CG, Barker J, et al. Relapse risk after umbilical cord blood transplantation: enhanced graft versus leukemia effect in recipients of two units. Blood. 2009;114(9):4293–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachanova V, Verneris MR, DeFor T, Brunstein CG, Weisdorf DJ. Prolonged survival in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after reduced-intensity conditioning with cord blood or sibling donor transplantation. Blood. 2009;113(13):2902–2905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin DY. Non-parametric inference for cumulative incidence functions in competing risks studies. Stat Med. 1997;16(8):901–910. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970430)16:8<901::aid-sim543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratanatharathorn V, Pavletic S, Uberti JP. Clinical applications of rituximab in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: anti-tumor and immunomodulatory effects. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35(8):653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]