Abstract

The near-completion of the sequence for chromosome 22q revolutionizes map integration. We describe a sequence-based integrated map containing 968 loci including 516 known or predicted gene sequences, 317 STSs not included in these sequences, and 135 nonexpressed multinucleotide polymorphisms. The published sequence spans 34.6 Mb, inclusive of gaps estimated to total 1.1 Mb, compared with a top-down estimate of 43 Mb. This discrepancy is discussed, but will not be resolved until more of the genome is analyzed. The radiation hybrid map has 5% error in order and 34% error in location exceeding 1 Mb. The utility of a composite location based on evidence other than sequence is limited to regions not yet sequenced. A genetic map conditional on sequence order was constructed from pairwise lods. Its length of 74.8 cM in males and 80.2 cM in females is slightly less than the previous estimate not constrained by sequence order. Five recombination hot spots are detected, with differences in location between the sexes. Male recombination correlates with repetitive DNA, whereas female recombination does not. It remains to be seen whether this is true for other human chromosomes. An algorithm to improve the fit of cytogenetic bands sequence location reduces the discrepancies in cytogenetic assignment from 61 to 38. This sequence-based integrated map is represented in the genetic location database (LDB2000), which is available at http://cedar.genetics.soton.ac.uk/public_html/LDB2000.html.

The genetic location database (LDB) presents integrated maps of the human genome, which are now being updated to sequence-based integrated maps (LDB2000, http://cedar.genetics.soton.ac.uk/public_html/LDB2000.html). Map integration is the process whereby locations on different scales (genetic, physical, radiation hybrid, and cytogenetic), derived from a number of sources, are represented in a summary map. Missing genetic, radiation hybrid, and cytogenetic locations are inferred by interpolation resulting in a fully integrated map. All locations are given relative to the telomere of the short arm (pter). Radiation hybrid locations are from the Genebridge 4 panel (cR3000) (Deloukas et al. 1998), whereas genetic locations are in centimorgans (cM) for sex-specific recombination with allowance for interference and typing error (Shields et al. 1991).

In LDB2000 cytogenetic, genetic and radiation hybrid maps do not contribute to the sequence-based physical map, but give evidence of chiasma interference and biological properties of chromosome location such as areas of radiation sensitivity, sex-specific intervals of atypical recombination, and relationship between gene density, recombination, and chromosome bands. These properties have been examined at the cytogenetic band level using integrated maps (Collins et al. 1996a), but such analyzes lack the precision offered by sequence-based map integration.

Recent developments in both sequencing technology and private sector initiatives have encouraged an acceleration of the program to sequence the entire human genome. Phase one of the human genome project to produce a “working draft” covering 85% of the euchromatic portion of human DNA is now complete (Pennisi 2000; Lander et al. 2001). The final phase to produce a “finished” sequence of the human genome by filling gaps and increasing accuracy to 99.9% has begun and is likely to be complete by 2003 or earlier. One of the first major results of this effort was the release of the near-complete sequence of chromosome 22q (Dunham et al. 1999), representing a finished sequence although small gaps remain unsequenced. This demonstrates that good coverage can be achieved using clone-by-clone approaches (11 gaps spanning ∼1076 kb in total length are recognized in 22q) and that connectivity of sequenced clones can be achieved with existing maps. More recently the near-complete euchromatic finished sequence of chromosome 21 has also been released (Hattori et al. 2000). An alternative approach of whole genome shotgun has also yielded impressive results in the form of a draft sequence of the entire genome (Venter et al. 2001).

Chromosome 22q is the first sequence-based integrated map to be represented in LDB2000. Previously, the physical scale for integrated maps was constructed using cytogenetic assignments of markers to bands by assuming that measured band width is proportional to DNA content. This is now replaced by sequence locations on the assumption that the 11 sequence gaps are accurately measured. Morton (1991) gives 43 Mb as the physical length of 22q estimated by a top-down approach from autoradiography, image cytometry, and flow cytometry. The published sequence (Dunham et al. 1999) spans 34.49 Mb of which 1.03 Mb is not sequenced and is estimated by DNA fiber fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and long-range restriction mapping. This has been revised to 34.55 Mb of which 1.08 Mb is estimated (available from the Sanger Centre ftp site, version Chr_22_01–12–1999.fa). Very little of the heterochromatic band q11.1 has been sequenced and is estimated at 2.61 Mb (Collins et al. 1996a), giving a total length of 37.16 Mb, which is 5.84 Mb less than expected. We assume for the present that the p arm occupies 13 Mb (Morton 1991), giving a total length of 50.16 Mb for chromosome 22. There are a number of possible explanations for the discrepancy in chromosome length estimates. One is that the total genome length of 3200 Mb (Tiersch et al. 1989) or that the fraction of the DNA total attributed to 22q are overestimates. Other possibilities are that the heterochromatic band q11.1 or p-arm contribute more DNA or that gaps and deletions have been underestimated or unrecognized.

Metaphase and DNA fiber FISH experiments performed during construction of the sequence ready clone map do not suggest that significant deletions have been overlooked. Although smaller deletions may have been missed by this method, their contribution to the total sequence length must be minimal. Perhaps the most likely explanation for the discrepancy is that the p arm or centromeric heterochromatin contains more tightly coiled DNA, therefore, its contribution to the total sequence length is underestimated. The p-arm length is also known to vary greatly among individuals (Reeves 2000). However, a definitive explanation awaits study of other chromosomes. Therefore, we scale lengths of chromosome arms and bands to correspond to the sequence evidence and retain the existing estimates for the p-arm and centromeric heterochromatin, arguably underestimated, giving a total chromosome length of 50.16 Mb.

We present here a map of chromosome 22q that integrates sequence, radiation hybrid, genetic, and cytogenetic data.

RESULTS

A total of 968 loci were identified in the 22q sequence (Table 1) leaving 44 that could not be located using BLAST searches against the chromosome 22q sequence of which 17 gave nonsignificant matches and 27 resulted in multiple hits of equal probability. Of the 17 nonsignificant matches, 11 contained repetitive elements whereas 10 of the 27 markers causing multiple hits contained repetitive elements. Among the small number of loci that could not be located in sequence, some may map to other chromosomes, the heterochromatic band 22q11.1, or known gaps, suggesting that the reported 97% coverage of the euchromatic portion of 22q is tolerably accurate (Dunham et al. 1999).

Table 1.

Classification of Loci

| Type | Class | Description | No. | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G | Gene: Transcribed region of the genome | 252 | Hugo > UniGene > GDB |

| g | Predicted gene based on UniGene clusters (n = 229) or sequence analysis (n = 35) | 264 | GenBank accession no. | |

| 2 | P | Polymorphic: Multiple polymorphisms* | 15 | D-number |

| V | Variable Number of Tandem Repeats (VNTR) | 2 | ||

| Q | Tetra-nucleotide repeat | 20 | ||

| T | Tri-nucleotide repeat | 7 | ||

| D | Di-nucleotide repeat | 83 | ||

| R | Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) | 1 | ||

| U | Unknown polymorphism | 7 | ||

| 3 | N | Nucleic acid** | 317 | GenBank accession no. |

| Total | 968 |

1, Genes; 2, polymorphisms; 3, DNA sequence.

Multiple polymorphisms with the same D-number.

Nucleic acid sequences that may include ESTs not yet associated with predicted genes and sequence-tagged sites.

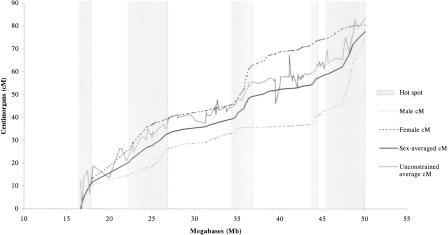

In the genetic map we estimated the interference parameter p in the Rao (1977) mapping function at 0.28 and typing error frequency E at 0.004 (Shields et al. 1991) for the sequence order constrained map. The sex-averaged map length (Fig. 1) was 77.6 cM compared to 83.4 cM in the unconstrained map. The male map length at 74.8 cM and the female at 80.2 cM is somewhat shorter than the unconstrained map lengths of 78 and 89 cM published by Collins (1996a) and the male map length is now closer to that of the chiasma map at 70 cM. Comparison of order inversions in the unconstrained map compared to the sequence-based map reveals an error rate of 4%. Both maps are illustrated in Figure 1. Location errors were further examined by estimating a physical location for each locus in the unconstrained genetic map by interpolating between shared flanking markers in the sequence-based genetic map. The difference between this location and the location obtained for the sequence-based map approximates the location error. Of the loci 42% were found to map within 1 Mb of the correct location, 71% were within 2 Mb, and 93% were within 4 Mb. The maximum discrepancy was 6.4 Mb.

Figure 1.

The relationship between recombination and the sequence-based physical map. Recombination hot spots in either sex are shaded.

As the order of polymorphic markers is now known it is possible to have more confidence in the location of recombination hotspots (Fig. 1). Five broad regions of elevated recombination are identified in approximately the locations noted in a sex-averaged map (Dunham et al. 1999), but a sex difference is now apparent. In these regions a sex-averaged maximum of 9.72 cM/Mb is observed between markers D22S1266 and D22S57 at locations 16.622 and 17.666 megabases, respectively. For acrocentric chromosomes it has been noted (Collins et al. 1996a) that there is a high recombination rate immediately distal to the centromeric heterochromatin, and is evident in both sexes here with a region of high recombination originating from the first marker in the genetic map located 1.011 Mb from the heterochromatic band 22q11.1.

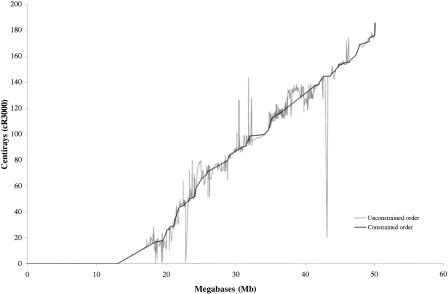

The relationship between the radiation hybrid and physical map is rather linear (Fig. 2), but there are some regions of apparently increased breakage, particularly close to the telomere. There may be increased breakage in R bands (Holmquist 1992), but a larger sample of bands would be required to demonstrate this. Calculation of order inversions between the sequence ordered and original radiation hybrid map gives an error frequency of 5%. The majority of loci (66%) map to within 1 Mb of the correct location, 87% to within 2 Mb, and 97% to within 4 Mb. Therefore, the resolution offered by this panel is limited to the approximate region for a locus. Higher resolution may be achieved by using larger radiation doses, but connectivity then becomes a much greater problem. The potential for gross errors is also evident as 15 (2.5%) show an error greater than 4 Mb, and 5 show an error greater than 8 Mb. Sources of error are numerous but include false-positive and false-negative reactions, homologous sequences giving strong reactions, errors in EST cluster assignments, and perhaps further nomenclature problems.

Figure 2.

Observed centirays and smoothed centirays against sequence-based distance.

The effect of revising the cytogenetic band sizes on the basis of cytogenetic assignment is primarily to decrease the width of band q13.31 from 5.2 to 1.9 Mb and increase the width of band q13.33 (from 1.4 to 5.1 Mb). These revisions are on the basis of cytogenetic assignments that have limited resolution close to band borders and therefore should be treated with caution. Published idiograms, however, are also highly variable (see, for example, Francke 1994; Harnden and Klinger 1985), particularly in the appearance of this terminal band. The borders of the four major bands are virtually unchanged, suggesting that higher resolution banding and band assignments are less reliable. The revision of the band sizes reduces the cytogenetic assignment errors in the map from 61 to 38. Despite revision of cytogenetic band sizes, no relationships between band shading, sequence motifs, radiation sensitivity, recombination, and gene density were identified. It remains to be seen whether such relationships become apparent when a larger sample of bands is analyzed.

When nonoverlapping 500-kb windows are examined (Tables 2 and 3) male recombination increases with increasing levels of repeat sequences (REP, LINE, and EL) particularly tandemly repeated DNA with element sizes between 10 and 100 bp (REP). Female recombination is related only to location (L) reflecting reduced female recombination near the telomere and relatively higher levels proximally. There are, however, a number of recombination hot spots in the female but these do not show a relationship to the variables examined. It is not clear, on the basis of one chromosome arm, that this is a general finding; more of the genome must be examined before a greater understanding of the differences between male and female recombination patterns emerges. Gene density (GD), as reported previously, is highly correlated with CpG islands and negatively associated with repetitive sequences.

Table 2.

Definition of Variables

| Variable name | Definition (kb/Mb unless otherwise stated) |

|---|---|

| L | Ordinal location of 500-kb segment from q11.21 |

| MD | Male cM/Mb |

| FD | Female cM/Mb |

| AD | Sex average cM/Mb |

| GD | Confirmed and predicted genes No./Mb |

| RD | Centri-ray 3000 rads/Mb |

| CpG | CpG island counts/Mb |

| GC | G + C content |

| REP | Length of tandem repeats (10–100bp element, 0.03–5 kb total size) |

| RAT | Length of tandem repeats (10–100bp element, 0.03–5kb total size) >60% AT |

| RGC | Length of tandem repeats (10–100bp element, 0.03–5 kb total size) >60% GC |

| SINE | (Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements) Length of ALUs + MIRs |

| LINE | (Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements) Length of LINE repeats |

| LTR | (Long Terminal Repeats) Length of MaLRs, Retrovires and Mer 4 group repeats |

| EL | DNA elements Lengths of MER1 + MER2 + Mariners repeats |

| SI | Length of simple repeats |

Table 3.

Regression Models for 500-kb Windows (Dependent Variables MD, FD, and GD)

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Coefficient | SE | R2 | Single variable correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | INTERCEPT | −4.556 | 0.965 | 0.553 | — |

| REP | 0.147 | 0.019 | 0.594** | ||

| SI | −0.188 | 0.061 | 0.007 | ||

| LINE | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.203 | ||

| EL | 0.137 | 0.048 | 0.283* | ||

| FD | INTERCEPT | 4.238 | 0.617 | 0.149 | — |

| L | −0.051 | 0.015 | −0.386** | ||

| GD | INTERCEPT | −2.061 | 3.709 | 0.499 | — |

| CPG | 1.190 | 0.206 | 0.251** | ||

| REP | −0.387 | 0.064 | −0.359** | ||

| LTR | 0.194 | 0.044 | 0.341** |

P <0.05.

P <0.01

P <0.001

DISCUSSION

It is evident that the genetic, radiation hybrid, and perhaps cytogenetic maps can be substantially improved by integration with sequence and, with the sequencing nearing completion, the integrated map has a continuing role in disease gene mapping and the understanding of chromosome organization, recombination, and disease processes. The relationship of the sequence to the genetic linkage map and eventually to cytogenetic bands can now be examined with some confidence as the order of markers and genes is known. Specific DNA sequences are known to influence recombination in many organisms (Purandare and Patel 1997). In particular, variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), which have 9–24 bp repeat elements and a total size of 0.1–2 kb and GT/CA dinucleotide repeats have been shown to be hot spots for homologous recombination (Wahls et al. 1990; Majewski and Ott 2000). The REP variable (Table 2) most closely resembles VNTRs and is associated with male recombination (Table 3). Alu sequences are a subclass of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) consisting of ∼280-bp repetitive units and have been suggested as promoting recombination due to mis-pairing between repeats (Lehrman et al. 1987). Analysis suggests that SINE sequences are not associated with recombination in chromosome 22. However, long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) are considered retrotransposable and are thought to have played an important role in generating recombination hot spots (Leib-Mosch and Seifarth 1995) and are associated with male recombination (Table 3).

Homologous recombination between region-specific, low copy repeats, or duplicons (Eichler 1998) during meiosis has been identified as a source of chromosomal rearrangements such as deletions, duplications, inversions, and inverted duplications depending on the orientation of the recombining repeats. Several low copy repeats have been mapped to 22q11 (LCR22) and their close proximity to each other makes this region susceptible to rearrangements (Dunham et al. 1999). Cat eye syndrome (CES) and velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS)/DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) are associated with 22q11 rearrangements (Edelmann et al. 1999; Shaikh et al. 2000). VCFS/DGS is the most common microdeletion disorder in humans, occurring with an estimated frequency of 1/4000 live births (Goodship et al. 1996). Haplotype analysis of VCFS/DGS individuals reveals common breakpoints between D22S1638 and D22S1709 located within LCR22–2 and 75 kb distal to LCR22–4, respectively, that mediate a 3-Mb deletion. The deleted region itself is not associated with especially elevated recombination (1.97 sex averaged cM/Mb). This and other regions of the genome may be susceptible to recombination-related rearrangements but this would not necessarily require a regionally high recombination rate. However, genetic maps constructed from case families might be expected to show relatively higher recombination in the region. Bass et al. (1999) examined a region on 15q11-q13 implicated in autistic disorder. In the sample of 63 families, significantly higher recombination was observed within these families in comparison to the CEPH reference map. Recombination might also interfere with transcription of critical genes through slippage and introduction of repeat sequences, although this mechanism is not yet established.

The difference between male and female recombination patterns is considerable. Wallace and Hulten (1985) observe that human female pachytene chromosomes are 50% longer than males. Purandare and Patel (1997) suggest that the overall lower recombination rate in males reflects the more condensed state of male chromosomes. This more condensed state must limit the available sites for recombination and perhaps these sites are restricted to certain repetitive structures as suggested by this analysis.

To identify genes contributing to complex traits, single nucleotide polymorphisms are now the markers of choice, particularly for mapping by allelic association. Although estimates of the numbers required for complete genome coverage are highly variable (500,000, Kruglyak 1999; 30,000, Collins et al. 1999), an important consideration is that markers should be spaced on the genetic rather than physical (sequence) map. Linkage disequilibrium relies on exploiting the pattern of decline in association with distance between a disease gene and a series of markers linked to it. This decline is determined by recombination (although mutation, drift, and other factors complicate this relationship). Lonjou (1998) have shown the effect of the different scales on the mapping of the hemochromatosis (HFE) gene. Low recombination in the nearby HLA region places this gene at only 0.75 cM from HLA-A, whereas, physically it is located at 4.6 Mb. Modeling the decline of disequilibrium with physical distance gives a very poor fit and location for the gene, whereas the genetic map gives a much better result. The pattern of disequilibrium around a single SNP can be represented using the Malecot model (Collins and Morton 1998) in which the parameter ε represents the product of recombination and time. Thus, ε is closely related to the recombination rate in the region of the SNP and should mirror the genetic map. Comparison of the genetic map constructed in this way will reveal how closely the relationship holds.

The analysis presented here shows the expected substantial improvement of the integrated map, which has until now relied on techniques with relatively low resolution that are subject to various kinds of error. The vast majority of loci assigned to chromosome 22q have been identified in the sequence and most of the remainder refer either to loci without an associated sequence or a small number of failed or multiple sequence matches. It is quite likely that the DNA content of the euchromatic portion of 22 has been overestimated by top-down approaches, although as yet the contribution of 22p and q11.1 is not known. Reliable fine-scale mapping could not be achieved by any of the techniques of linkage, radiation hybrids, and cytogenetical assignment, but knowledge of the precise order gives greater confidence in the comparison of these alternative scales. This sequence-based integrated map should be a useful tool in both disease gene mapping and understanding chromosome properties.

METHODS

Clusters, Symbols, and Nomenclature

We define a locus as a gene or DNA sequence that can be amplified by PCR. Large regions that do not have short sequences associated with them such as syndromes associated with a regional deletion or duplication (CECR, BCRL3, BCRL2, DGCR, DGCR6, and MGCR), or gene families (IGLC@) and putative loci (SCZD4) are not represented. Loci might be STSs or ESTs placed on the map through radiation hybrids or polymorphisms that can also be mapped by linkage, and all can be identified in a covering sequence map. A single point (their approximate mid-point location) represents loci in a summary map in the sequence. As a single gene sequence might contain multiple polymorphisms and a larger number of ESTs (hence clustering developments like UniGene), we have clustered map objects apparently derived from the same expressed sequence. Clusters are formed by cross-referencing loci in LDB with GDB (http://gdbwww.gdb.org/) and UniGene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/Hs.Home.html). Associated with each symbol in a cluster are radiation hybrid locations from GeneMap'99, cytogenetic locations from GDB and UniGene, sequence locations from GDB ePCR, the Sanger Centre and BLAST searches performed against the 22q sequence, and genetic, physical, and mouse homology data from LDB. Clusters are cross-referenced through name comparisons and matching clusters combined. The clustering process is checked by calculating the variance for each location data type in a cluster, clusters with large variances are examined, and erroneous clusters prevented from forming. A single “primary” name is used to represent each cluster in the map. Primary names for genes are chosen using the following hierarchy: Hugo nomenclature committee > UniGene symbol > GDB primary name. Table 1 gives a classification of loci. Genes may contain different classes of polymorphism and are labeled in the map through combination of class identifiers. Thus, GD reflects a gene containing a dinucleotide repeat and GP implies a gene with multiple polymorphisms. Single nucleotide polymorphisms are excluded from this classification. D-numbers are chosen as primary names for polymorphisms that are not located within named genes, whereas GenBank accession numbers are used to represent STSs and other nucleic acid sequences, some of which are ESTs not yet associated with a predicted gene. Higher resolution maps of individual loci or regions represent the location of intragenic polymorphisms including SNPs, exonic structure, and other features. This depends on a high level of sequence annotation and will be improved as more is known about the sequence.

Genetic Linkage and Radiation Hybrid Maps

Sex-specific pairwise lods derived from the CEPH version 8.2 database and disease lods from GENATLAS (http://bisance.citi2.fr/GENATLAS/) were entered into the map+ program (Collins et al. 1996b). A total of 177 loci with lods were identified, of which 136 were located and ordered from the sequence and used in mapping. The remaining loci were either clones not associated with a sequence or could not be definitively located using BLAST searches. The final map contained a number of loci assigned to the same location reflecting the relatively small number of meioses and typing error. We improved the resolution of this map by repositioning clustered markers in proportion to their spacing in the sequence by interpolating between flanking markers at non-zero genetic distance. An unconstrained genetic map was also constructed for estimation of the error in multiple pairwise linkage mapping (Fig. 1).

Radiation hybrids (RH) have been useful for the localization of monomorphic sequences such as ESTs. There is a possibility of some gross errors in order because the number of informative clones is small and false signals are quite frequent (Teague et al. 1996). Locations for discrepant loci were recalculated by interpolation between flanking markers. The method for interpolation follows Morton et al. (1992). If a, b represent ordered flanking loci with locations Sa, Sb and Ra, Rb in the sequence-based and radiation hybrid maps and Sx the sequence-based location for the locus with a discrepant radiation hybrid location, and Sa < Sx < Sb, then the revised radiation hybrid location (Rx) is Rx = Ra + (Rb − Ra) (Sx − Sa) / (Sb − Sa). This is achieved by an iterative ranking algorithm that first resolves the most discrepant loci then reranks and resolves the next most discrepant loci until the orders agree. The original and resolved RH map are illustrated in Figure 2.

Comparison of the order (and distance) discrepancy between two maps can be achieved by evaluating all n(n − 1)/2 pairwise comparisons and obtaining the frequency of those with an order inversion (Kendall and Stuart et al. 1961). Thus, if the order in the sequence-based map is 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, but the unconstrained map gives 1, 3, 2, 4, 5, then all possible comparisons are made 1–3, 1–2, 1–4, 1–5, 3–2, 3–4, …, and so on, and the frequency of order inversions evaluated (10% in this example).

Refining Cytogenetic Bands

To examine properties of the chromosome at the 850-band resolution, band widths/border locations must be determined. Many loci have been assigned to cytogenetic bands by direct cytologic methods such as FISH, although a proportion have been inferred from map location evidence. Although assignments are inaccurate, especially near band borders, knowledge of the precise order from sequence allows refinement of the band widths/border locations that are otherwise based on observation (Francke 1994) and not on DNA content. Errors in assignment to each band are counted by taking the current best estimates of band border locations and enumerating the loci that do not map within the band cytogenetically. For a pair of adjacent bands the distribution of errors in band assignment varies as a step function as the location of the border (μ) is moved. To improve the correspondence between the cytogenetic and sequence maps we take R = ∑e−di for errors to the right of μ and L = ∑e−di for errors to the left, where di = δ (wi − μ) and wi is the sequence-based location of the locus with an error and δ is −1 if wi < μ and +1 otherwise. To resolve errors we iteratively minimize the function f = (R − L)2/2 with distance in Mb. In this way gross assignment errors are discounted but smaller errors close to a boundary are resolved.

Sequence Analysis

There are only 11 cytogenetic bands in the sample, which are insufficient for analysis of cytogenetic band properties. However, relationships between sequence motifs, recombination, and radiation sensitivity were investigated in nonoverlapping 500-kb windows. Determination of CpG content and number of tandem repeats with element sizes from 10 to 100 bp (REP, RAT, RGC; Table 2) was performed using the EMBOSS suite of sequence analysis programs (Rice, Bleasby and Williams at http://sanger.ac.uk/Software/EMBOSS/), whereas Repeat Masker (Smit and Green, unpubl. software, http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/RM/RepeatMasker.html) was used to identify other repeats (SINE, LINE, LTR, EL, SI; Table 2). Definition of variables and results of stepwise regression and correlation analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

EMAIL wjt@soton.ac.uk; FAX 023-807-94264.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.161301.

REFERENCES

- Bass MP, Menold MM, Wolpert CM, Donnelly SL, Ravan SA, Hauser ER, Maddox LO, Vance JM, Abramson RK, Wright HH. Genetic studies in autistic disorder and chromosome 15. Neurogenetics. 1999;2:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s100489900081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn J, Goodship J. Congenital heart disease. In: Rimoin DL, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, editors. Emery and Rimoin's principals and practice of medical genetics. 3rd ed. UK: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. pp. 767–828. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Morton NE. Mapping a disease locus by allelic association. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:1741–1745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Frezal J, Teague J, Morton NE. A metric map of humans: 23,500 loci in 850 bands. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996a;93:14771–14775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Teague J, Keats BJ, Morton NE. Linkage map integration. Genomics. 1996b;36:157–162. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Lonjou C, Morton NE. Genetic epidemiology of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:15173–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloukas P, Schuler GD, Gyapay G, Beasley EM, Soderlund C, Rodriguez-Tome P, Hui L, Matise TC, McKusick KB, Beckmann JS, et al. A physical map of 30,000 human genes. Science. 1998;282:744–746. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham I, Shimizu N, Roe BA, Chissoe S, Hunt AR, Collins JE, Bruskiewich R, Beare DM, Clamp M, et al. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22. Nature. 1999;402:489–495. doi: 10.1038/990031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE. Masquerading repeats: Paralogous pitfalls of the human genome. Genome Res. 1998;8:758–762. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.8.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann L, Pandila RK, Morrow BE. Low copy repeats mediate the common 3 Mb deletion in velo-cardio-facial syndrome patients on 22q11. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1076–1086. doi: 10.1086/302343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francke U. Digitized and differentially shaded human-chromosome ideograms for genomic applications. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;65:206–218. doi: 10.1159/000133633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnden DG, Klinger HP, editors. ISCN. An international system for Human Cytogenetic nomenclature. Basel/New York: Karger, S.; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, Fujiyama A, Taylor T D, Watanabe H, Yada T, Park H S, Toyoda A, Ishii K, Totoki Y, Choi D, K, et al. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 21. Nature. 2000;405:311–319. doi: 10.1038/35012518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist GP. Chromosome bands, their chromatin flavors, and their functional features. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:17–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall MG, Stuart A. The advanced theory of statistics. New York: Mantger Publishing Company; 1961. . Chapter 2, pp. 476–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak L. Prospects for whole-genome linkage disequilibrium mapping of common disease genes. Nature Genet. 1999;22:139–144. doi: 10.1038/9642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leib-Mosch C, Seifarth W. Evolution and biological significance of human retro elements. Virus Genes. 1995;11:133–145. doi: 10.1007/BF01728654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrman MA, Russell DW, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Alu–Alu recombination deletes splice acceptor sites and produces secreted low density lipoprotein receptor in a subject with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3354–3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonjou C, Collins A, Ajioka RS, Jorde LB, Kushner JP, Morton NE. Allelic association under map error and recombinational heterogeneity: A tale of two sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:11366–11370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski J, Ott J. GT repeats are associated with recombination on human chromosome 22. Genome Res. 2000;10:1108–1114. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton NE. Parameters of the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:7474–7476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton NE, Collins A, Lawrence S, Shields DC. Algorithms for a location database. Ann Hum Genet. 1992;56:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1992.tb01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi E. Finally, the book of life and instructions for navigating it. Science. 2000;288:2304–2307. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purandare SM, Patel PI. Recombination hot spots and human disease. Genome Res. 1997;7:773–786. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.8.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao DC, Morton NE, Lindsten J, Hulten M, Yee S. A mapping function for man. Hum Hered. 1977;27:99–104. doi: 10.1159/000152856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves RH. Recounting a genetic story. Nature. 2000;405:283–284. doi: 10.1038/35012790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh HT, Kurahashi H, Saitta SC, O'Hare AM, Hu P, Roe BA, Driscoll DA, McDonals-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Budarf ML, et al. Chromosome 22-specific low copy repeats and 22q11.2 deletion syndromes: Genomic organization and deletion endpoint analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:489–501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields DC, Collins A, Buetow KH, Morton NE. Error filtration, interference and the human linkage map. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:6501–6505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague JW, Collins A, Morton NE. Studies on locus content mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:11814–11818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiersch TR, Chandler RW, Wachtel SS, Elias S. Reference-standards for flow-cytometry and application in comparative studies of nuclear-DNA content. Cytometry. 1989;10:706–710. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990100606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahls WP, Wallace LJ, Moore PD. Hypervariable minisatellite DNA is a hotspot for homologous recombination in human cells. Cell. 1990;60:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90719-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BMK, Hulten MA. Meiotic chromosome pairing in the normal female. Annu Hum Genet. 1985;49:215–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1985.tb01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]