Abstract

An increasing number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the Y chromosome are being identified. To utilize the full potential of the SNP markers in population genetic studies, new genotyping methods with high throughput are required. We describe a microarray system based on the minisequencing single nucleotide primer extension principle for multiplex genotyping of Y-chromosomal SNP markers. The system was applied for screening a panel of 25 Y-chromosomal SNPs in a unique collection of samples representing five Finno–Ugric populations. The specific minisequencing reaction provides 5-fold to infinite discrimination between the Y-chromosomal genotypes, and the microarray format of the system allows parallel and simultaneous analysis of large numbers of SNPs and samples. In addition to the SNP markers, five Y-chromosomal microsatellite loci were typed. Altogether 10,000 genotypes were generated to assess the genetic diversity in these population samples. Six of the 25 SNP markers (M9, Tat, SRY10831, M17, M12, 92R7) were polymorphic in the analyzed populations, yielding six distinct SNP haplotypes. The microsatellite data were used to study the genetic structure of two major SNP haplotypes in the Finns and the Saami in more detail. We found that the most common haplotypes are shared between the Finns and the Saami, and that the SNP haplotypes show regional differences within the Finns and the Saami, which supports the hypothesis of two separate settlement waves to Finland.

The sequence variation on the Y chromosome has appeared to be low, and until recently only a modest number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were known (for references, see Table 1). By screening 18 kb of coding sequence in four genes in the nonrecombining parts of the Y chromosome in samples from the five continents, ∼100 new Y-chromosomal SNPs were recently discovered (Shen et al. 2000). The frequency of SNPs was found to be lower than that of autosomal SNPs (Shen et al. 2000), in accordance with the four-times-lower effective population size of the Y chromosome and a recent common ancestor for the Y chromosome (Hammer 1995; Thomson et al. 2000). The Y-chromosomal SNPs are useful biallelic markers for following paternal lineages as a complement to the widely analyzed sequence variation of the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (DiRienzo and Wilson 1991; Sajantila et al. 1995; Sigurðardóttir et al. 2000). Because SNPs in the nonrecombining parts of the Y chromosome can be considered as the results of unique events during evolution, they can be used in combination with the more rapidly evolving microsatellite markers to construct well-defined haplotypes to improve the power of the statistical analysis of the results (Jobling et al. 1997).

Table 1.

PCR and Minisequencing Primers for the Y-Chromosomal SNP Markers

| Locus | Primerbc | Sequence, 5′ to 3′d | Size of PCR product (bp) | Nucleotide variatione | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DYS271a | 5′ PCR primer | GCT CCC CTG TTT AAA AAT GTA GG | 136 | A/G | Seielstad et al. 1994 |

| (M2) | 3′ PCR primer | TAC AGC TCC CCC TTT ATC CTC C | |||

| ms primer | CCT TTA TCC TCC ACA GAT CTC A | ||||

| 92R7a | 5′ PCR primer | TGC ATG AAC ACA AAA GAC GTA | 100 | C/T | Mathias et al. 1994 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GCA TTG TTA AAT ATG ACC AGC | Hurles et al. 1999 | |||

| ms primer | TTA AAT ATG ACC AGC AAA GAC AA | ||||

| SRY4064a | 5′ PCR primer | CCA GCC CTT CGA GAG GTC AA | 106 | G/A | Whitfield et al. 1995 |

| 3′ PCR primer | CAG GAT GGT CTC AAT CTC TTC | ||||

| ms primer | CTC TTC ACC CTG TGA TCC GCT | ||||

| SRY9138 | 5′ PCR primer | GTT GAT ATG ATA TTA TAG AGG C | 118 | C/T | Whitfield et al. 1995 |

| 3′ PCR primer | ACC TAC ATG CAA AAA TAA GGA TG | ||||

| ms primer | GAG GCA AAT TTA ATG CTC TCG G | ||||

| SRY10831a | 5′ PCR primer | TGG CCT CTT GTA TCT GAC TTT TT | 112 | A/G | Whitfield et al. 1995 |

| (SRY-1532) | 3′ PCR primer | CAA GGC ACC ACA TAG GTG AAC | Kwok et al. 1996 | ||

| ms primer | CAT AGG TGA ACC TTG AAA ATG TTA | Veitia et al. 1997 | |||

| DYS199 | 5′ PCR primer | AAT AGG TTG ACC TGA CAA TGG | 113 | C/T | Underhill et al. 1996 |

| (M3) | 3′ PCR primer | TCA TTT TAG GTA CCA GCT CTT | |||

| ms primer | AAT GGG TCA CCT CTG GGA CTG A | ||||

| PN1 | 5′ PCR primer | AGG AAC AAG GGT CTT GAG AGG | 98 | C/T | Hammer et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | TAT CTC TTC CCC TTT AAG ACA A | ||||

| ms primer | AAG GGT CTT GAG AGG GAG AGC | ||||

| PN2a | 5′ PCR primer | CTT CAT GCT GGT TAA AGG AGC A | 145 | C/T | Hammer et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | ACC TCA GAA TCA GCT CCA | ||||

| ms primer | AGG TGC CCC TAG GAG GAG AA | ||||

| PN3 | 5′ PCR primer | AGC ATC TGA GAA AAC TGC CTC | 104 | A/G | Hammer et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | CAA TGC TCC TAA CTC TAA TTT AC | ||||

| ms primer | TCT GAG AAA ACT GCC TCT GCT TGA | ||||

| Tata | 5′ PCR primer | CTC TGA GTG TAG ACT TGT GA | 146 | T/C | Zerjal et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GAA GGT GCC GTA AAA GTG TGA A | ||||

| ms primer | CTC TGA AAT ATT AAA TTA AAA CAA C | ||||

| SRY2627 | 5′ PCR primer | CGC AGT TTG GCT TCC GGG CC | 121 | C/T | Veitia et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | TTC ACC CTG TAG GGC ATG GG | Bianchi et al. 1997 | |||

| ms primer | CCA AGG AAG CCC CAC AGG GTG C | ||||

| M4a | 5′ PCR primer | TCC TAG GTT ATG ATT ACA GAG CG | 319 | A/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| (DYS234) | 3′ PCR primer | GCA GAA CAT TTG TAC TGT TCC | |||

| ms primer | ACT AGA TAT AGA TCT TAG ATA TGA TTA | ||||

| M6 | 5′ PCR primer | ACC ACA TTT CTG GTT GGC TTG T | 132 | C/T | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | CCC TAC TTT GAT GGC TAA TAC TA | ||||

| ms primer | TGG TTG GCT TGT AGT TCT TTC T | ||||

| M7 | 5′ PCR primer | GCA TCA CCA AAG GGC ATG TAA TC | 116 | C/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | TGA GTT ACT GTT CTT CTT GTT GTT | ||||

| ms primer | AAA GGG CAT GTA ATC ATT CCT CT | ||||

| M8a | 5′ PCR primer | CCC ACC CAC TTC AGT ATG AA | 318 | G/T | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | ACT CGA GGC TGA CAG AC | ||||

| ms primer | GAC CAA TAG AAG AAC TGC CCA A | ||||

| M9 | 5′ PCR primer | GTA AGA CAT TGA ACG TTT GAA CA | 154 | C/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GCA GCA TAT AAA ACT TTC AGG A | ||||

| ms primer | GAA ACG GCC TAA GAT GGT TGA AT | ||||

| M11 | 5′ PCR primer | GCA TAA ACA AGA ACT TAC TGA G | 270 | A/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | TAT CTC TCT GTC TGT CTC TC | ||||

| ms primer | CCC TCT CTC CTT GTA TTC TAA C | ||||

| M12a | 5′ PCR primer | CTC CCG AGT AGC TGG GAA | 155 | G/T | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| DYS260 | 3′ PCR primer | AGC AGT CCA AGA CTA GCC TGA G | |||

| ms primer | TGA GCA ACA TAG TGA CCC CCA T | ||||

| M13 | 5′ PCR primer | GCC ATG ATT TTA TCC AAC C | 142 | C/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GGG CAG TAG GTA GGT TAA GGG | ||||

| ms primer | GTA GGT TAA GGG CAA GAC GGT TA | ||||

| M14 | 5′ PCR primer | TGT TAA AAC TGA GCT TCA TTA AC | 204 | T/C | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GGT TGG ATA AAA TCA TGG CT | ||||

| ms primer | ATT ATA AAT GAA AAA ATC AGT AAC ATG | ||||

| M17 | 5′ PCR primer | CAA ACT GAT GTA GAG ACA TCT | 175 | G/Tf | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | ACT CAC CAG AGT TTG TGG TTG | ||||

| ms primer | GTG GTT GCT GGT TGT TAC GGG | ||||

| M19 | 5′ PCR primer | CAA ACT GAT GTA GAG ACA TCT | 175 | A/T | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | ACT CAC CAG AGT TTG TGG TTG | ||||

| ms primer | AAA CTA TTT TTG TGA AGA CTG TTG TA | ||||

| M20 | 5′ PCR primer | TCT ACA TGT TCA GTG CAA ATG CA | 211 | A/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GAT TGG GTG TCT TCA GTG CT | ||||

| ms primer | GTC AAC CAA CTG TGG ATT GAA AAT | ||||

| M21a | 5′ PCR primer | ATT TGA GCA GGC AGA AGA ATC A | 197 | A/T | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | TTG TGG GTA ATA GGC ATG TCT | ||||

| ms primer | CTG GAA GCT AAG TCA ACT GAA AC | ||||

| M22a | 5′ PCR primer | TCC CTA TTT GTT TTA AGG TGC CA | 121 | A/G | Underhill et al. 1997 |

| 3′ PCR primer | GCA GAC TAA GGC CCA TAT GGG | ||||

| ms primer | TAT GGG CAC TGG GGG AAG GAG G |

Detection from complementary DNA strand compared to reference.

PCR primers contained the nonspecific universal sequences TTC TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GA and GCG GTC CCA AAA GGG TCA GT in the 5′ end of either the forward or the reverse primers. The minisequencing primers contained a spacer-sequence of 15 T-residues in their 5′ ends.

ms = Minisequencing.

Primer sequences shown in bold were designed for this study; unbolded primer sequences are from the reference.

The nucleotide variation is given as in the reference.

M17 is a deletion of G; T is the next nucleotide detected in the minisequencing reaction.

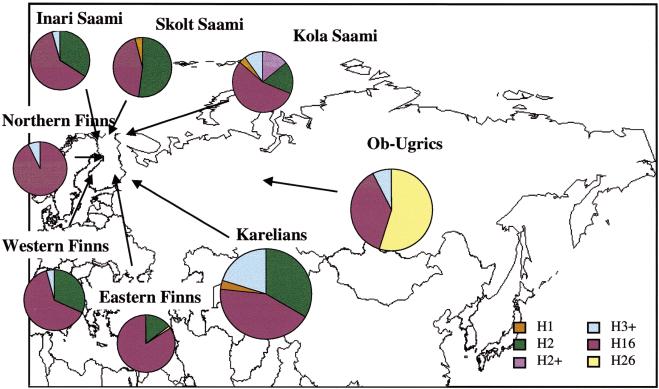

A variety of techniques have been applied for discovering and genotyping Y-chromosomal SNPs; of these, heteroduplex analysis using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) has been the most successful approach (Underhill et al. 1997). DHPLC has proven to be particularly efficient for discovering new SNPs, but the technique is useful also for scoring previously known ones (Underhill et al. 1997; Shen et al. 2000). As the number of known SNPs on the Y chromosome increases, methods with higher throughput than those currently available will be required to utilize the potential of known SNP markers in population studies effectively. Microarray-based genotyping technology is a promising alternative for parallel and simultaneous analysis of many SNPs in large sample sets (Hacia 1999; Pastinen et al. 2000). In the present study we describe a microarray system based on the minisequencing single nucleotide primer extension principle (Syvänen et al. 1990; Pastinen et al. 1997) to facilitate rapid and reliable multiplex genotyping of Y-chromosomal SNPs. Using this newly developed genotyping system we screened a panel of 25 human Y-chromosomal SNPs in a unique collection of 300 samples representing five Finno–Ugric-speaking populations. The samples were from Finns originating from various geographical locations in Finland, three different Saami groups, Karelians from Russia, and Ob-Ugric Mansi and Khantyi speakers (Fig. 1). In addition to the Y-chromosomal SNPs, we typed five Y-chromosomal microsatellite loci in these samples. Altogether, 10,000 genotypes were generated to assess the genetic diversity in these population samples.

Figure 1.

The geographic origin of the sampled Finno–Ugric-speaking populations and the frequencies of Y-chromosomal haplotypes formed by SNPs in these populations. For haplotype designation and nomenclature as well as the population frequencies of the observed haplotypes, see Table 5.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Genotyping System

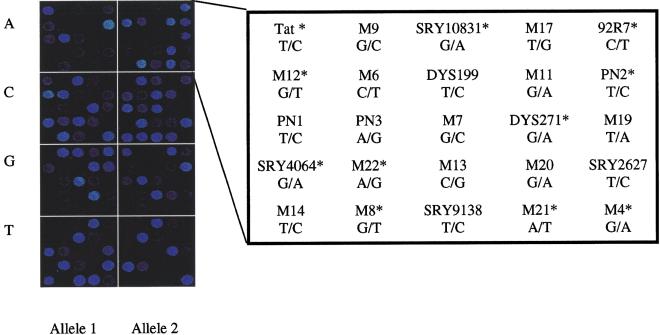

A method based on minisequencing single nucleotide primer extension (Syvänen 1999) in a micorarray format was developed for multiplex genotyping of 25 Y-chromosomal SNPs. The 25 SNPs to be included in the panel were selected from the literature, and minisequencing primers for each SNP were designed to anneal to the DNA region immediately adjacent to the site of the SNP (Table 1). The primers were immobilized covalently on glass microscope slides as 5 × 5 arrays (Fig. 2). The genotyping procedure involves (1) multiplex PCR amplification of the Y-chromosomal DNA regions spanning the SNPs; (2) extension of the immobilized primers with labeled ddNTPs using a DNA polymerase with the multiplex PCR products as templates; (3) measurement of the incorporated label on the microarrays; and (4) interpretation of the results.

Figure 2.

Result from validation of the microarray-based genotyping system. Two mixtures of 25 synthetic oligonucleotide templates corresponding to one of the alleles at each SNP site were analyzed in minisequencing reactions on the microarrays to verify that both alleles of each SNP marker would be detected. (Left panel) The fluorescence image obtained from four detection reactions (A, C, G, T) with TAMRA-labeled ddNTPs. (Right panel) Order of the SNP markers on the array with the nucleotide variation at each site. The asterisk indicates those alleles that are detected from complementary DNA strands compared to earlier published literature.

Performing multiplex PCR amplification is a major rate-limiting step in all currently applied genotyping procedures. Amplification of more than 10 fragments reproducibly and successfully from multiple samples has proven to be difficult (Hacia et al. 1998; Pastinen et al. 2000). In the present study a touchdown PCR procedure (Don et al. 1991) was used to circumvent differences in amplification efficiency arising from differences in melting temperatures between the PCR primers in combination with universal 5′ sequences on the primers (Shuber et al. 1995). This procedure allowed us to unify the reaction kinetics of the primer annealing and amplify 24 Y-chromosomal SNPs as two sets of multiplex PCRs with 17 and 6 primer pairs, respectively. Although the success rate of the optimized multiplex PCRs was 100% for six of the SNPs, in 4% of the samples one or more SNP sites failed to amplify in the multiplex PCR (Table 2). These failures were recognized as absence of signal in the reactions on the microarrays, and these genotypes were obtained after reamplification of the first PCR product, followed by retyping using microarrays. The marker 92R7 was amplified and genotyped individually by minisequencing in the microtiter plate format (Syvänen 1997) because the SNP is located in one out of several repetitive segments (C. Tyler-Smith, pers. comm.), and our initial experiments showed that it was difficult to genotype on the arrays. The minisequencing reactions were optimized with respect to concentration of detection primers during their immobilization to the microarrays, and with respect to concentration of ddNTPs and DNA polymerase during the reactions on the microarrays. The high reaction temperature and short reaction time were found to be critical for avoiding false positive signals caused by template-independent extension of some of the primers. The protocol given in the Methods section is the result of these optimization experiments.

Table 2.

Success Rate of Multiplex PCRs

| SNP-marker | Success rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 17 plex PCRa | |

| Tat | 100 |

| PN3 | 100 |

| M19 | 100 |

| SRY4064 | 100 |

| M4 | 100 |

| SRY10831 | 98 |

| M17 | 98 |

| M20 | 98 |

| SRY2627 | 96 |

| M9 | 94 |

| M6 | 94 |

| M14 | 90 |

| DYS199 | 88 |

| M11 | 85 |

| SRY9138 | 85 |

| M8 | 83 |

| M7 | 60 |

| DYS271 | 46 |

| 6 plex PCR | |

| PN2 | 100 |

| M12 | 96 |

| M21 | 96 |

| Pn1 | 88 |

| M22 | 87 |

| M13 | 81 |

The M17 and M19 SNP sites are amplified within one PCR fragment.

To validate that the microarray-based system would detect either allele of all 25 Y-chromosomal SNPs correctly, two mixtures of artificial single-stranded oligonucleotide templates representing one of the alleles at each site were analyzed. Figure 2 shows the fluorescence image from this analysis. Table 3 gives the corresponding numeric values measured by the fluorescence scanner and the calculated signal ratios defining the haploid Y-chromosomal genotypes. As can be seen, the 5-fold to infinite differences in signal ratios (R values) between the two genotypes provide unequivocal results at all sites. Unequivocal discrimination between genotypes is achieved also when multiplex PCR fragments amplified from the genomic DNA samples are analyzed. The range of R values for the monomorphic markers was 0.005–0.070 with an average of 0.03, or 0.98–1.0 with an average of 0.99, respectively. Table 4 illustrates the genotyping results when 5 or 10 samples of each genotype at the polymorphic Tat, M9, SRY10831, and M17 SNP sites were analyzed using both radioactive (33P) and fluorescence (TAMRA) detection. Both the detection systems perform well, with the largest difference in fluorescent and radioactive signal ratios for the marker M9. The microarray-based minisequencing system allows genotyping of diploid SNPs both using 33P as label as shown in a previous study (Pastinen et al. 1998) and using fluorescence based on our more recent work (K. Lindroos et al., unpubl.). The major advantage of the fluorescence detection system is the higher resolution of the fluorescence scanner, which allows measurement of an extremely large number of data points on a miniaturized area.

Table 3.

Results from Fluorescent Detection of Both Alleles of 25 Y-Chromosomal SNPs in Artificial Single Stranded Templates

| Mixture of alleles 1 | Mixture of alleles 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP (Allele1/Allele2) | signalb | R-valuec | signalb | R-valuec | Power of genotype discriminationd | ||

| allele 1 | allele 2 | allele 1 | allele 2 | ||||

| Tata (T/C) | 1808 | 4 | 1.0 | 0 | 1415 | 0 | ∞ |

| M9 (G/C) | 4673 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 3643 | 0 | ∞ |

| SRY10831a (G/A) | 3436 | 5 | 1.0 | 496 | 3481 | 0.13 | 7.7 |

| M17 (T/G) | 4592 | 339 | 0.93 | 32 | 4094 | 0.0078 | 120 |

| 92R7a (C/T) | 4882 | 175 | 0.97 | 162 | 6584 | 0.024 | 40 |

| M12a (G/T) | 7305 | 162 | 0.98 | 654 | 5937 | 0.099 | 9.9 |

| M6 (C/T) | 3871 | 0 | 1.0 | 45 | 2964 | 0.015 | 67 |

| DYS199 (T/C) | 3497 | 11 | 1.0 | 22 | 3950 | 0.0055 | 180 |

| M11 (G/A) | 4689 | 0 | 1.0 | 45 | 7835 | 0.0057 | 170 |

| PN2a (T/C) | 9905 | 1028 | 0.91 | 1440 | 6348 | 0.19 | 4.8 |

| PN1 (T/C) | 3779 | 4 | 1.0 | 0 | 5473 | 0 | ∞ |

| PN3 (A/G) | 3236 | 34 | 1.0 | 0 | 2890 | 0 | ∞ |

| M7 (G/C) | 6559 | 0 | 1.0 | 112 | 3357 | 0.032 | 31 |

| DYS271a (G/A) | 3528 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 3454 | 0 | ∞ |

| M19 (T/A) | 1011 | 0 | 1.0 | 31 | 1879 | 0.016 | 63 |

| SRY4064a (G/A) | 4803 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 3622 | 0 | ∞ |

| M22a (A/G) | 3872 | 669 | 0.85 | 382 | 5113 | 0.070 | 12 |

| M13 (C/G) | 3470 | 0 | 1.0 | 96 | 4397 | 0.021 | 48 |

| M20 (G/A) | 7076 | 5 | 1.0 | 422 | 4619 | 0.084 | 12 |

| SRY2627 (T/C) | 3939 | 4 | 1.0 | 0 | 4779 | 0 | ∞ |

| M14 (T/C) | 1815 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 2354 | 0 | ∞ |

| M8a (G/T) | 6553 | 83 | 0.99 | 2104 | 9072 | 0.19 | 5.2 |

| SRY9138 (T/C) | 3131 | 141 | 0.96 | 0 | 3817 | 0 | ∞ |

| M21a (A/T) | 4080 | 4 | 1.0 | 0 | 6681 | 0 | ∞ |

| M4a (G/A) | 5187 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 3018 | 0 | ∞ |

Detection from complementary strand.

Arbitrary fluorescence units.

R-value = Allele1/(Allele 1 + Allele 2).

Rmix. of alleles 1/Rmix. of alleles 2.

Table 4.

Accuracy of Genotype Discrimination and Comparison of Radioactive and Fluorescent Detection in Minisequencing on Microarrays for Four Polymorphic Y-Chromosomal SNPs

| Tat (T/C) R = T/(T+C)a | M9 (G/C) R = G/(G+C) | SRY10831 (G/A) R = G/(G+A)a | M17 (T/G) R = T/(T+G) | |||||

| Sample genotypeb | T | C | G | C | G | A | T | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent detection | ||||||||

| Variationc | 0.90–0.93 | 0–0.07 | 0.91–1.0 | 0.06–0.40 | 0.75–1.0 | 0–0.04 | 0.70–0.80 | 0–0.08 |

| Average | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.16 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 0.04 |

| Power of genotype discriminationd | 23 | 6.1 | 44 | 19 | ||||

| Radioactive detection | ||||||||

| Variation | 0.99–1.00 | 0.00–0.05 | 0.93–0.99 | 0–0.09 | 0.94–1.0 | 0–0.04 | 0.92–0.99 | 0–0.05 |

| Average | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.02 |

| Power of genotype discriminationd | 50 | 32 | 48 | 49 | ||||

Detection from complementary strand.

Data from ten samples of each genotype was used, except for the fluorometric measurements of M9 C allele, SRY10831 G allele and M17 T allele where only five samples were used.

The range of variation between the lowest and highest R values.

Raverage of alleles1/Raverage of alleles2.

Y-Chromosomal SNP and Haplotype Frequencies

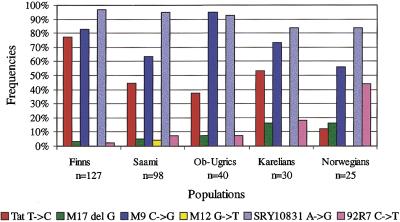

Our analysis of the Finnish, Saami, Karelian, Mansi, and Khantyi samples for the 25 Y-chromosomal SNP markers included in the panel revealed that five of them (M9, Tat, SRY10831, M17, and 92R7) were polymorphic in all our population samples. The SNP M12 (DYS260), with a G → T transversion, was also polymorphic to some extent in the Kola-Saami samples (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the M12 T allele has also been found in other European populations as well as in subcontinent Indians (Underhill et al. 1997). The rest of the 19 markers were monomorphic, which agrees well with the earlier published literature (Bianchi et al. 1997; Hammer et al. 1997; Karafet et al. 1999). The genotypes of the polymorphic markers were confirmed by solid-phase minisequencing in a microtiter format (data not shown; Syvänen 1997).

Figure 3.

Allele frequencies of six polymorphic Y-chromosomal SNP markers.

Thus, we found six polymorphic Y-chromosomal SNPs in our population samples, and six different haplotypes could be constructed from these (see Table 5 for the haplotype nomenclature). The most striking difference in haplotype frequencies between the populations is that the haplotype H26 is present at high frequency in the Ob-Ugric sample (55%, Fig. 1), whereas it is absent in other groups, with the exception of the Finns, where it was found once in the subgroup of Eastern Finns (Fig. 1; Table 5). On the other hand, haplotype H2, which occurs with high frequency in other population samples (15%–52%), is absent in our Ob-Ugric sample. Haplotype H16, which has earlier been reported to be present in several Northern Eurasian samples, was represented in our study with high frequency in all samples at a frequency varying from 38% in Ob-Ugrics to 77% in the Finns. Figure 1 and Table 5 summarize the haplotype frequencies in the analyzed populations.

Table 5.

| Haplotype frequency (%) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus | Population | |||||||||||||||||

| Haplotype | Tat (T/C)c | M9 (G/C) | SRY10831 (G/A)c | M17 (del G) | M12 (G/T)c | 92R7 (C/T) | Eastern Finns (n = 66) | Western Finns (n = 47) | Northern Finns (n = 14) | All Finns (n = 127) | Inari Saami (n = 46) | Kola Saami (n = 29) | Skolt Saami (n = 23) | All Saami (n = 98) | Karelians (n = 30) | Mansi (n = 19) | Khantyi (n = 21) | All Ob-Ugric (n = 40) |

| H2+ | T | C | G | G | T | C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 4.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H2 | T | C | G | G | G | C | 15 | 32 | 0 | 19 | 34 | 17 | 52 | 33 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H26 | T | G | G | G | G | C | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79 | 33 | 55 |

| H16 | C | G | G | G | G | C | 84 | 64 | 93 | 77 | 61 | 55 | 44 | 55 | 43 | 16 | 57 | 38 |

| H1 | T | G | G | G | G | T | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H3+ | T | G | A | T | G | T | 0 | 4.3 | 7.1 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 10 | 0 | 5.2 | 20 | 5.3 | 9.5 | 7.5 |

| Nucleotide diversity | 0.087 | 0.194 | 0.187 | 0.202 | 0.305 | 0.187 | 0.339 | 0.117 | 0.192 | |||||||||

| Mean pairwise difference | 0.53 | 1.16 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 1.83 | 1.12 | 2.04 | 0.70 | 1.15 | |||||||||

The nomenclature used in this study is according to published literature (Jobling and Tyler-Smith 1997; Tyler-Smith 1999).

The substitutions from ancestral state are shown bolded. The A-allele at SRY 10831 site is revertant on an M9-G background (Hammer et al. 1998).

Detection from complementary strand.

Many of the SNPs analyzed in our panel seem to be restricted to specific populations. The DYS199 C → T transition, for instance, has so far been shown to be polymorphic only among AmerIndians and in the Chukchan populations in Northeastern Siberia (Underhill et al. 1996; Karafet et al. 1997; Lell et al. 1997; Ruiz-Linarez et al. 1999). Only the C allele was identified in our sample collection. Similarly, the SNP M19, with a T → A transversion, has been found only in some South American populations (Underhill et al. 1997; Ruiz-Linarez et al. 1999). The Tat T → C transition is also geographically restricted and has so far been observed only in Northern Eurasian populations (Zerjal et al. 1997; Lahermo et al. 1999). In our samples the Finns had the highest frequency (78%) of the C allele, but this variant also appeared in all the other populations, including the Norwegians (which were used as a reference population) with a frequency of 12% (Fig. 3). In an earlier study the frequency in Norwegians was found to be 4% (Zerjal et al. 1997). However, the C → G substitution at the M9 locus appears to be an old mutation because it is frequent worldwide with the exception of Africa. Its absence in Africa might suggest that it occurred initially outside Africa during an early divergence out of Africa. The G allele has been shown to be prevalent in Eurasia, which is consistent with our data (Underhill et al. 1997). It is highly frequent in the Finns and in the Saami, and usually occurs on the same chromosome as the Tat C allele. Assuming that the order of mutation is correct, and that no back mutations have occurred at these sites, the two major haplogroups are divided by two mutation steps.

One of the major haplotypes (H2) carries a chromosome pool with the M9 C allele together with the Tat T allele, whereas the other major haplotype (H16) is the result of two subsequent mutations, wherein first the M9 C has been substituted with G after which the Tat T has been substituted with C. The latter has been shown to be the most frequent allele in Finland (Zerjal et al. 1997; Lahermo et al. 1999). This haplotype is highly frequent, especially in the Northern and Eastern parts of Finland, where its frequency reaches 93% and 84%, respectively (Fig. 1; Table 5). These regional differences between the Eastern and Northern parts compared to Western Finland support the earlier archeological and genetic evidence for two separate settlement waves to Finland (Kittles et al. 1998; Lahermo et al 1999). Even though YAP+ is supposed to have an equal time depth as the M9, and is present in different European populations as well as Asian populations it, has not been found in the Finns and Saami (Lahermo et al. 1999; Altheide and Hammer 1997). This is consistent with our data, as the YAP+ and DYS271 G allele are associated, and only the A allele of DYS271 was found in our samples. In earlier studies the PN2 C → T transition was reported to occur after the SRY4064 G → A transition (Altheide and Hammer 1997) and also after the DYS271 A → G transition in a YAP+ haplotype lineage (Hammer et al. 1997). Our data also support this finding, because our samples only contained the ancestral allele of these three markers.

To further characterize the genetic hierarchy of the Finno–Ugric-speaking populations we applied an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) by grouping the populations according to linguistics into Finnish speakers, Saami speakers, and Ob-Ugric speakers. This division also corresponds to their geographical localities, and thus no further division according to geography could be made. According to the AMOVA analysis, the vast majority (83%) of the sequence variation on the Y chromosome based on the analyzed SNPs occurs within different populations, whereas 10% occurs among the linguistic subgroups, and only 6.5% occurs between populations among linguistic subgroups. Also earlier studies based on autosomal markers have indicated that 80%–90% of the genetic variation in humans occurs within populations (Barbujani et al. 1997). Our study confirms this finding, although a large variation owing to geographical distances is not expected, since our study populations are from areas relatively close to each other. Obviously, more populations with large number of individuals should be studied to further characterize the underlying demographic or cultural factors that have played a role in forming the genetic structure of these rather isolated populations.

Y-Chromosomal Microvariation in the Finnish and the Saami Subgroups

We further studied the genetic structure of the Finns and the Saami, who have proved to be genetically distinct based on mitochondrial DNA sequences (Sajantila et al. 1995) and autosomal markers (Sajantila and Pääbo 1995), but similar based on Y-chromosomal microsatellites (Lahermo et al. 1999). For this analysis, we genotyped five Y-chromosomal microsatellite markers, DYS389-I, DYS389-II, DYS391, DYS393, and DYS19, and assigned the microsatellite alleles to the SNP haplotypes in our population samples. We found that within the major haplotypes H2 and H16 in the Finns and Saami, the most frequent microsatellite allele was identical, with the exception of the DYS19 locus in haplotype H2 and the DYS389-1 locus in haplotype H16 (Table 6). In addition, shared microsatellite haplotypes were observed within the haplotypes formed by the SNPs, but not between them. Therefore, the most common Y-chromosomal haplotypes are shared between the Finns and the Saami, indicating that there have been at least two founding Y-chromosomal lineages in these populations. This finding is in accordance with the archeological data that indicates a dual origin for the Finns, and also with the earlier Y-chromosomal data from the Finns and the Saami (Kittles et al. 1999; Lahermo et al. 1999; Kittles et al. 1999; Semino et al. 2000). However, our data also indicate that within the Finns and the Saami there might be significant subpopulations with regional differences. This is not only seen in the variation of the haplogroup frequencies, but also in the genetic diversity values. For example, the nucleotide diversity in the eastern and northern Finns is strikingly low compared to that of other study populations and the western Finns in particular (Table 5).

Table 6.

Microsatellite Allele Frequencies within The Major Y-Chromosomal Haplotypes H2 and H16 in the Finns and Saamia

| Allele Frequency (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsatellite locus | Allele | H2 | H16 | ||

| Finns | Saami | Finns | Saami | ||

| DYS389-1 | 9 | 77 | 84 | 1 | 55 |

| 10 | 14 | 6 | 28 | 39 | |

| 11 | 9 | 10 | 65 | 4 | |

| 12 | — | — | 5 | 2 | |

| DYS389-2 | 25 | 5 | 3 | — | — |

| 26 | 64 | 83 | 4 | 2 | |

| 27 | 18 | — | 30 | 57 | |

| 28 | 5 | — | 62 | 37 | |

| 29 | 5 | — | 5 | 6 | |

| 30 | 5 | 3 | — | 2 | |

| 31 | — | 3 | — | — | |

| 32 | — | 7 | — | — | |

| DYS391 | 10 | 95 | 87 | 20 | 19 |

| 11 | 5 | 13 | 80 | 81 | |

| DYS393 | 12 | — | — | 1 | — |

| 13 | 95 | 98 | 5 | 30 | |

| 14 | 5 | 3 | 88 | 70 | |

| 15 | — | — | 7 | — | |

| DYS19 | 14 | 73 | 3 | 98 | 92 |

| 15 | 23 | 57 | 2 | 8 | |

| 16 | 5 | 13 | — | — | |

The most frequent alleles are shown in bold.

METHODS

Population Samples

The Finnish samples originated from two sources. One part of the samples had been collected for a cross-sectional survey on coronary heart disease risk factors in Finland (Vartiainen et al. 1994). The second part of the samples was collected from healthy, unrelated male blood donors (Finnish Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, Helsinki, Finland). The birthplace of each individual sample donor as well as that of his parents and grandparents were known. The Ob-Ugric and Kola Saami samples were collected by one of the authors (A. Sajantila) during anthropological field surveys to West Siberia in 1995 and the Kola Peninsula in 1996 (see Fig. 1). The collection of the Inari and Skolt Saami and Karelian samples has been described earlier (Lahermo et al. 1999); these were provided by M.-L. Savontaus (University of Turku, Finland). The samples from Norwegian males were provided by M. Stenersen (University of Oslo, Norway). DNA was extracted from the blood samples by standard procedures.

Preparation of Oligonucleotide Arrays

The primer arrays were prepared on microscope glass slides with Teflon lining forming 8 wells of 11 mm in diameter or 12 wells of 5 mm in diameter (Erie Scientific). The slides were prewashed with a 1% Alconox (Aldrich) solution, and rinsed several times with distilled water and ethanol. The minisequencing detection primers with 5′-amino groups (Table 1) were immobilized to isothiocyanate-activated glass surfaces essentially as described by Guo et al. (1994), except that 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (Sigma) was used for silanization instead of the methoxy-derivative. The detection primers were dissolved in 400 mM sodium carbonate buffer at pH 9.0 to a final concentration of 25 μM prior to spotting. Immediately after spotting, the slides were exposed to vaporized ammonia for 1 h, followed by three washes in distilled water. The arrays were stored at −70°C for up to 8 weeks.

A custom-built, modified industrial robot (Isel) with two TeleChem CPH-2 printing pins controlled by an MCM-310 operating system and NUMO-6.0 software (Merval) was used to print the oligonucleotide detection primers onto the coated slides. For radioactive detection, two adjacent spots 125–150 μm in diameter of each detection primer at a 400-μm distance from each other were printed to increase the signal intensities. The distance from the middle of the double spot to the next one was 1000 μm. The primer order was the same as for the fluorescent detection system, for which the detection primers were applied as spots 125–150 μm in diameter at a center-to-center distance of 250 μm (Fig. 2).

PCR Amplification of SNPs

The PCR primers were synthesized by Interactiva Biotechnologie GmbH (Ulm). Their sequences are listed in Table 1. DNA fragments spanning the SNP sites were amplified using a touchdown thermocycling profile in a Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Tetrad Research). The parameters were: Initial activation of the polymerase at 95°C for 11 min, then 95°C for 30 sec, and 65°C − °C per cycle for 4 min for 5 cycles; 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C − 0.5°C per cycle for 2 min, and 68°C for 2 min for 15 cycles; 95°C for 30 sec, 53°C for 30 sec, and 68°C for 2 min for 14 cycles; 68°C for 2 min. One multiplex PCR containing primers for the 18 markers DYS271 (M2), DYS199 (M3), SRY4064, SRY9138, SRY10831, SRY2627, PN3, M4, M6, M7, M8, M9, M11, M14, M17, M19, M20, and Tat, and a second multiplex PCR with the 6 markers PN1, PN2, M12, M13, M21, and M22 were performed using 10–50 ng of genomic DNA, 3.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), and 200 μM dNTPs in 100 μL of DNA polymerase buffer supplied with the enzyme (N808-0244). The primer concentrations ranged from 0.1 to 1.2 μM, and they had initially been adjusted to yield similar amounts of each DNA fragment and to minimize primer–dimer formation. For occasional reamplification of individual fragments 1 μL of a 1/100 dilution of the multiplex PCR product was used under the conditions given above. The marker 92R7 was amplified individually under the same conditions as the multiplex PCRs.

SNP Genotyping on Oligonucleotide Arrays

The combined PCR products were precipitated by ethanol, followed by suspension into 80 μL of 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.5 and 5 mM MgCl2 buffer containing 0.002 U/μL DNase (Ampliscribe T7 Transcription Kit, Epicentre Technologies) and 0.01 U/μL shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min, followed by inactivation of the enzymes at 95°C for 20 min. Then 20 μL of a buffer containing 500 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 250 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl, and 1% Triton X 100 was added, and the mixture was preheated together with the arrays at 95°C for 1.5 min. Next 10 μL of this mixture was applied to the arrays to four reaction wells 5 mm in diameter. In case of the larger 11-mm wells, 20 μL of the mixture was used. The annealing reaction was allowed to proceed in a humid chamber at 37°C for 15 min. The arrays were briefly washed with a solution of 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 25 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton-X 100.

Each minisequencing reaction mixture contained one of the four 33P-labeled ddNTPs (AP Biotech) at a 0.01 μM concentration or TAMRA-labeled ddATP, ddGTP, or ddTTP at a 0.05 μM concentration or ddCTP at a 0.2 μM concentration (NEN Life Science Products), together with the other three unlabeled ddNTPs at a concentration of 0.1 μM in 26 mM Tris-HCl at pH 9.5, 6.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.2% Triton X-100 buffer with 0.05 U/μL DynaSeq DNA polymerase (a kind gift from Finnzymes, Helsinki, Finland) or ThermoSequenase (AP Biotech). The reaction mixture and the arrays carrying the annealed templates were preheated to 68°C for 2 min. The reaction volume for the 5-mm wells was 10 μL, and for the 11-mm wells it was 20 μL. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 68°C for 5 min in a humid chamber, after which the slides were washed three times for 15 min at room temperature in a solution of 90 mM Na-citrate, 900 mM NaCl, and 0.05% N-lauroyl-sarcosine. The slides were further washed twice with dH2O for 15 min, once with 50 mM NaOH for 5 min, and finally with dH2O for 15 min.

Radioactive signals were detected after an overnight exposure to imaging plates (Fuji, Kanawaga, Japan) using a phosphorimager instrument (Fuji BAS 1500 Bioimaging Analyzer). The signal intensities were measured with the Tina 2.10 software (Raytest). Fluorescence signals were detected using an array scanner (ScanArray 4000, GSI Lumonics), and the signal intensities were measured with the QuantArray analysis software (GSI Lumonics). The ratio between the signal from the reaction for one allele divided by the total signals from the reactions for both alleles was calculated.

Minisequencing in a Microtiter Format

The SNP marker 92R7 was genotyped, and the genotypes of the polymorphic SNP markers M17, SRY10831, M12, Tat, and M9 were confirmed by solid-phase minisequencing in a microtiter plate (Syvänen 1997). For amplification of the individual fragments, the PCR primers were those given in Table 1, except that the 3′ PCR primers for markers 92R7 and SRY10831 were biotinylated in their 5′ end. The 92R7 and SRY10381 sites were amplified individually from 25 ng of genomic DNA using 1.75 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) with a 0.2 μM PCR primer concentration in a 50-μL volume, except that for the SRY10831 marker the biotinylated 3′ PCR primer was used at a 0.04 μM concentration. The PCR parameters were the same as for the multiplex PCR given above. The markers Tat, M9, M17, and M12 were amplified individually with both primers at a 0.2 μM concentration under the conditions given above. Of this first amplification product, 1 μL of a 1/100 dilution was subjected to a second amplification with a biotinylated universal primer 5′-GCGGTCCCAAAAGGGTCAGT to introduce a biotin residue to the PCR products for affinity capture for the minisequencing reaction. The concentration of the biotinylated universal primer was 0.04–0.08 μM, depending on the marker, and it was used together with one of the unbiotinylated primers used in the first amplification at a 0.2 μM concentration under the PCR conditions given above.

The minisequencing primers for the markers M12 and M17 were those given in Table 1. For 92R7, the minisequencing primer was 5′-ATGAACACAAAAGACGTAGAAG; for SRY10831 it was 5′-GTATCTGACTTTTTCACACAGT; for M9 it was 5′-GTCTAAATTAAAAGAAAAATAAAGAG; and for Tat it was T(15) TGAGTGTAGACTTGTGAATTCA from the complementary DNA strand.

Genotyping of Microsatellite Markers

The PCR primer sequences for the microsatellite markers DYS19, DYS389-I, DYS389-II, DYS391, and DYS393 were obtained from the Genome Database (http://www.gdb.org/). The forward primers were fluorescently labeled (DYS 19-TET, DYS 389-FAM, DYS 391-FAM, and DYS 393-TET). The microsatellite markers were amplified using 20 ng of genomic DNA with 1.2 U AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase and 200 μM of dNTPs in 100 μL of DNA polymerase buffer supplied with the enzyme (N808-0244). Two separate multiplex PCRs were performed. One of the reactions contained primers for the markers DYS19, DYS389-I, and DYS389-II at 0.3 μM and 0.2 μM concentrations (DYS389-1 and DYS389-II are in one fragment). The cycling parameters were 95°C for 10 min, 94°C for 45 sec for 30 cycles, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

The other multiplex PCR mixture contained primers for the markers DYS391 and DYS393 at 0.3 μM and 0.1 μM concentrations. The cycling parameters were 95°C for 10 min, 94°C for 1 min for 30 cycles, 51°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

The PCR products were combined and run in an ABI 377 DNA Sequencer according to the manuals supplied with the sequencer (PE Biosystems). The allelic fragments were detected and sized by the GeneScan 3.1 and ABI-Genotyper 2.0 programs. The fragment sizes were converted into number of repeats using five previously sequenced samples (kindly provided by Manfred Kayser, Leipzig, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

The population genetic analyses of the Y-chromosomal SNP, microsatellite, and haplotype data were performed using the ARLEQUIN (ver 2.0) software package (Schneider et al. 1997). The hierarchic distribution of Y-chromosome diversity was computed using the analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) software.

Acknowledgments

We thank Auli Bengs, Minttu Hedman, Kirsti Höök, Liisa Kauppi, Minna Levander, and Päivi Tainola for assistance with laboratory work, and Paavo Niini for technical expertise with the arrayer. We are grateful to Michael Hammer, Chris Tyler-Smith, and Peter Underhill for unpublished sequences, and to Manfred Kayser for the control microsatellite sequences. We thank Finnzymes for providing the DynaSeq DNA polymerase free of charge. This work was funded by EC Biomed2, Contract no. BMH4-CT97-2013, the Instrumentarium Foundation, and the Academy of Finland (project no. 42183).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Ann-Christine.Syvanen@medsci.uu.se; FAX 46-18-6112519.

Article and publication are at www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.156301 .

REFERENCES

- Altheide TK, Hammer MF. Evidence for possible Asian origin of YAP+ Y chromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:462–466. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbujani G, Magagni A, Minch E, Cavalli-Sforza LL. An apportionment of human DNA diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:4516–4519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi NO, Bailliet G, Bravi CM, Carnese RF, Rothhammer F, Martinez-Marignac VL, Pena SD. Origin of Amerindian Y-chromosomes as inferred by the analysis of six polymorphic markers. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;102:79–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199701)102:1<79::AID-AJPA7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRienzo A, Wilson AC. Branching pattern in the evolutionary tree for human mitochondrial DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:1597–1601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Don RH, Cox PT, Wainwright BJ, Baker K, Mattick JS. 'Touchdown' PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4008. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Guilfoyle RA, Thiel AJ, Wang R, Smith LM. Direct fluorescence analysis of genetic polymorphisms by hybridization with oligonucleotide arrays on glass supports. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5456–5465. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.24.5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacia JG. Resequencing and mutational analysis using oligonucleotide microarrays. Nat Genet. 1999;21:42–47. doi: 10.1038/4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacia JG, Sun B, Hunt N, Edgemon K, Mosbrook D, Robbins C, Fodor SPA, Tagle D, Collins FS. Strategies for mutational analysis of the large multiexon ATM gene using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Genome Res. 1998;8:1245–1258. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer MF. A recent common ancestry for human Y chromosomes. Nature. 1995;378:376–378. doi: 10.1038/378376a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer MF, Spurdle AB, Karafet T, Bonner MR, Wood ET, Novelletto A, Malaspina P, Mitchell RJ, Horai S, Jenkins T, et al. The geographic distribution of human Y chromosome variation. Genetics. 1997;145:787–805. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer MF, Karafet T, Rasanayagam A, Wood ET, Altheide TK, Jenkins T, Griffiths RC, Templeton AR, Zegura SL. Out of Africa and back again: Nested cladistic analysis of human Y chromosome variation. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:427–441. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurles ME, Veitia R, Arroyo E, Armerentos M, Bertranpetit J, Pérez-Lezaun A, Bosch E, Shlumukova M, Cambon-Thomsen A, McElreavey K, et al. Recent male-mediated gene flow over a linguistic barrier in Iberia, suggested by analysis of a Y-chromosomal DNA polymorphism. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1437–1448. doi: 10.1086/302617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling MA, Pandya A, Tyler-Smith C. The Y chromosome in forensic analysis and paternity testing. Int J Leg Med. 1997;110:118–124. doi: 10.1007/s004140050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafet T, Zegura SL, Vuturo-Brady J, Posukh O, Osipova L, Weibe V, Romero F, Long LC, Harihara S, Jin F, et al. Y chromosome markers and trans-Bering Strait dispersals. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;102:301–314. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199703)102:3<301::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafet TM, Zegura SL, Posukh O, Osipova L, Bergen A, Long J, Goldman D, Klitz W, Harihara S, de Kniff P, et al. Ancestral Asian source(s) of New World Y-chromosome founder haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:817–831. doi: 10.1086/302282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittles RA, Perola M, Peltonen L, Bergen AW, Aragon RA, Virkkunen M, Linnoila M, Goldman D, Long JC. Dual origins of Finns revealed by Y chromosome haplotype variation. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1171–1179. doi: 10.1086/301831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittles RA, Bergen AW, Urbanek M, Virkkunen M, Linnoila M, Goldman D, Long JC. Autosomal, mitochondrial, and Y chromosome DNA variation in Finland: Evidence for a male-specific bottleneck. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1999;108:381–399. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199904)108:4<381::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok W, Tyler-Smith C, Mendonca BB, Hughes I, Berkovitz GD, Goodfellow PN, Hawkins JR. Mutation analysis of the 2 kb 5′ to SRY in XY females and XY intersex subjects. J Med Genet. 1996;33:465–468. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.6.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahermo P, Savontaus ML, Sistonen P, Beres J, de Knijff P, Aula P, Sajantila A. Y chromosomal polymorphisms reveal founding lineages in the Finns and the Saami. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:447–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lell JT, Brown MD, Schurr TG, Sukernik RI, Starikovskaya YB, Torroni A, Moore LG, Troup GM, Wallace DC. Y chromosome polymorphisms in native American and Siberian populations: Identification of native American Y chromosome haplotypes. Hum Genet. 1997;100:536–543. doi: 10.1007/s004390050548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias N, Bayes M, Tyler-Smith C. Highly informative compound haplotypes for the human Y chromosome. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:115–123. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastinen T, Kurg A, Metspalu A, Peltonen L, Syvänen A-C. Minisequencing: A specific tool for DNA analysis and diagnostics on oligonucleotide arrays. Genome Res. 1997;7:606–614. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.6.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastinen T, Perola M, Niini P, Terwilliger J, Salomaa V, Vartiainen E, Peltonen L, Syvänen A-C. Array-based multiplex analysis of candidate genes reveals two independent and additive genetic risk factors for myocardial infarction in the Finnish population. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1453–1462. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastinen T, Raitio M, Lindroos K, Tainola P, Peltonen L, Syvänen A-C. A system for specific, high-throughput genotyping by allele-specific primer extension on microarrays. Genome Res. 2000;10:1031–1042. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Linares A, Ortiz-Barrientos D, Figueroa M, Mesa N, Munera JG, Bedoya G, Velez ID, Garcia LF, Perez-Lezaun A, Bertranpetit J, et al. Microsatellites provide evidence for Y chromosome diversity among the founders of the New World. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6312–6317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajantila A, Pääbo S. Language replacement in Scandinavia. Nat Genet. 1995;11:359–360. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajantila A, Lahermo P, Anttinen T, Lukka M, Sistonen P, Savontaus ML, Aula P, Beckman L, Tranebjaerg T, Gedde-Dahl T, et al. Genes and languages in Europe: An analysis of mitochondrial lineages. Genome Res. 1995;5:42–52. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Kueffer J-M, Roessli D, Excoffier L. Arlequin ver 1.1: A software for population genetic data analysis. Switzerland: Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Seielstad MT, Hebert JM, Lin AA, Underhill PA, Ibrahim M, Vollrath D, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Construction of human Y-chromosomal haplotypes using a new polymorphic A to G transition. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:2159–2161. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.12.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semino O, Passarino G, Oefner PJ, Lin AA, Arbuzova S, Beckman LE, De Benedictis G, Francalacci P, Kouvatsi A, Limborska S, et al. The genetic legacy of paleolitic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: A Y chromosome perspective. Science. 2000;290:1155–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen P, Wang F, Underhill PA, Franco C, Yang W-H, Roxas A, Sung R, Lin AA, Hyman RW, Vollrath D, et al. Population genetic implications from sequence variation in four Y chromosome genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:7354–7359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuber AP, Grondin VJ, Klinger KW. A simplified procedure for developing multiplex PCRs. Genome Res. 1995;5:488–493. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.5.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurðardóttir S, Helgason A, Gulcher JR, Stefansson K, Donnelly P. The mutation rate in the human mtDNA control region. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1599–1609. doi: 10.1086/302902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvänen A-C. Solid-phase minisequencing. In: Miller GR, editor. Laboratory methods for the detection of mutations and polymorphisms in DNA. Florida: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Syvänen A-C. From gels to chips: “Minisequencing” primer extension for analysis of point mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:1–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:1<1::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvänen A-C, Aalto-Setälä K, Harju L, Kontula K, Söderlund H. A primer-guided nucleotide incorporation assay in the genotyping of apolipoprotein E. Genomics. 1990;8:684–692. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90255-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson R, Pritchard JK, Shen P, Oefner PJ, Feldman MW. Recent common ancestry of human Y chromosomes: Evidence from DNA sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:7360–7365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler-Smith C. Y-chromosomal DNA markers. In: Papiha SS, et al., editors. Genomic diversity: Applications in human population genetics. New York: Plenum; 1999. pp. 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill PA, Jin L, Zemans R, Oefner PJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL. A pre-Columbian Y chromosome-specific transition and its implications for human evolutionary history. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:196–200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill PA, Jin L, Lin AA, Mehdi SQ, Jenkins T, Vollrath D, Davis RW, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Oefner PJ. Detection of numerous Y chromosome biallelic polymorphisms by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Genome Res. 1997;7:996–1005. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen E, Puska P, Jousilahti P, Korhonen HJ, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Twenty-year trends in coronary risk factors in North Karelia and in other areas of Finland. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:495–504. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitia R, Ion A, Barbaux S, Jobling MA, Souleyreau N, Ennis K, Ostrer H, Tosi M, Meo T, Chibani J, et al. Mutations and sequence variants in the testis-determining region of the Y chromosome in individuals with a 46,XY female phenotype. Hum Genet. 1997;99:648–652. doi: 10.1007/s004390050422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield LS, Sulston JE, Goodfellow PN. Sequence variation of the human Y chromosome. Nature. 1995;378:379–380. doi: 10.1038/378379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerjal T, Dashnyam B, Pandya A, Kayser M, Roewer L, Santos FR, Schiefenhovel W, Fretwell N, Jobling MA, Harihara S, et al. Genetic relationships of Asians and Northern Europeans, revealed by Y-chromosomal DNA analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:1174–1183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]