Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Acute and chronic gastric volvulus usually present with different symptoms and affect patients primarily after the fourth decade of life. Volvulus can be diagnosed by an upper gastrointestinal contrast study or by esophagogastroduodenoscopy. There are three types of gastric volvulus: 1) organoaxial (most common type); 2) mesenteroaxial; and 3) a combination of the two. If undetected or if a delay in diagnosis and treatment occurs, serious complications can develop.

Methods:

We present four cases of surgical repair of organoaxial volvulus consisting of laparoscopic reduction of the volvulus with excision of the hernia sac and reapproximation of the diaphragmatic crura. A Nissen fundoplication, to prevent reflux, was performed, and the stomach was pexed to the anterior abdominal wall by laparoscopic placement of a gastrostomy tube, thus preventing recurrent volvulus.

Results:

There were no operative complications, and all four patients tolerated the procedure well. The patients were discharged one to three days postoperatively and were asymptomatic within two months.

Conclusion:

With the advancement of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal and hiatal hernias, minimally invasive surgical repair is possible. Based on our experience, we advocate the laparoscopic technique to repair gastric volvulus.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Volvulus, Gastric volvulus

INTRODUCTION

Gastric volvulus affects patients of all ages but most often occurs after the fourth decade of life. If undetected, gastric volvulus can lead to ulceration, perforation, hemorrhage or ischemia and full-thickness necrosis. Symptoms are variable and can range from anemia and weight loss to severe epigastric and/or chest pain sometimes associated with unproductive vomiting or upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Suspicion is heightened by a large air fluid level in the lower chest seen on chest x-ray; diagnosis is made with an upper gastrointestinal contrast study or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). With the advancement of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal and hiatal hernias, minimally invasive surgical repair is possible. We describe four cases of organoaxial volvulus that were repaired laparoscopically.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 40-year-old woman was hospitalized with recurrent symptoms of left chest pain and emesis and was found to be anemic. Cardiac work-up was negative. A chest radiograph showed a large paraesophageal hernia. Endoscopy revealed Cameron erosions as a probable source of her anemia. Her symptoms were believed to result from a chronic intermittent gastric volvulus, since more than half of her stomach was within the left hemithorax. Intraoperative findings revealed a large left-sided paraesophageal hernia with the esophagogastric junction at the diaphragmatic hiatus and an organoaxial volvulus. The volvulus was reduced, the hernia sac was excised, and the crura were reapproximated. A floppy Nissen fundoplication was performed along with laparoscopic placement of a gastrostomy tube. There were no operative or postoperative complications. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 1, tolerating a full liquid diet; and she was asymptomatic after six weeks, at which time the gastrostomy tube was removed, and she was discharged from further folllow-up.

Case 2

A 71-year-old man presented to us after a brief episode of acute left chest pain associated with dyspnea. The cardiac work-up was negative. A chest radiograph showed a large hiatal hernia, and an upper GI showed an intrathoracic stomach with an organoaxial volvulus. The hernia and volvulus were reduced laparoscopically with complete excision of the hernia sac, and a standard floppy Nissen fundoplication with concomitant gastrostomy tube placement was performed. There were no operative or postoperative complications, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 2, tolerating a full liquid diet. The gastrostomy tube was removed eight weeks after surgery at which time he was asymptomatic and discharged from follow-up.

Case 3

An 84-year-old man with significant coronary artery disease had been admitted several times for evaluation of atypical left-sided chest pain. Upper GI and CT scan of the lower chest and abdomen showed a paraesophageal hernia. An esophageal manometry study was normal, but the lower esophageal sphincter could not be evaluated secondary to an organoaxial volvulus. The volvulus was reduced via a laparoscopic approach with complete excision of the hernia sac, and a floppy Nissen fundoplication was performed. A redundant gastrosplenic ligament was noted at the time of surgery. There were no intraoperative complications. However, the postoperative course was complicated by new onset cardiac dysrhythmia, which was controlled by medication but prolonged his postoperative stay. He was discharged on postoperative day 7, tolerating a full liquid diet. The patient was asymptomatic at his 8-week follow-up visit and was, thus, discharged from care.

Case 4

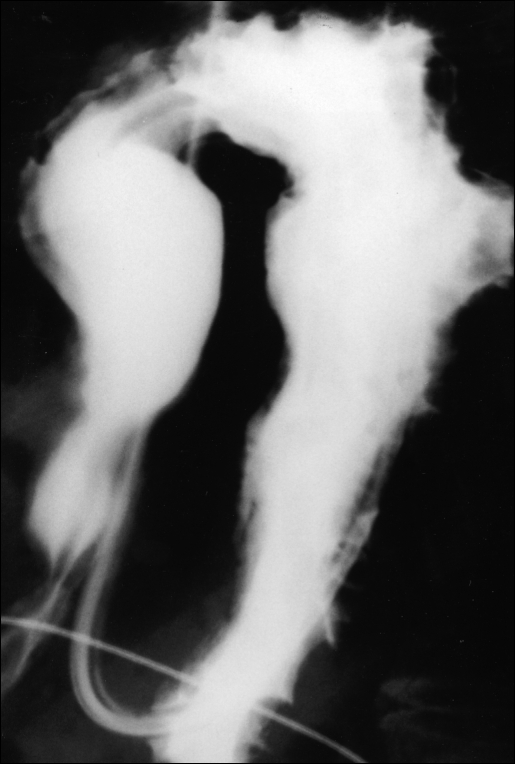

A 61-year-old man was transferred from an outlying hospital with an upper GI bleed. He also complained of left-sided chest pain; after a negative cardiac work-up, a chest radiograph showed a markedly elevated left hemidiaphragm. The patient underwent an EGD evaluation that revealed an organoaxial volvulus. The volvulus was reduced endoscopically, and further evaluation with endoscopy revealed ischemic ulceration of the stomach. A follow-up upper GI study showed that the stomach had re-volvulized in the organoaxial position (Figure 1). Laparoscopic reduction and Nissen fundoplication with concomitant laparoscopic gastrostomy tube placement were performed. A postoperative upper GI confirmed normal gastric position (Figure 2). There were no operative or postoperative complications, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 3, tolerating a full liquid diet. The patient was asymptomatic at his eight-week follow-up examination, at which time the gastrostomy tube was removed, and he was discharged from follow-up.

Figure 1.

Organoaxial volvulus as shown by upper GI contrast study following reduction by endoscopy. Note position of the nasogastric tube as it courses through the esophagus and makes a 180° turn back into the thoracic cavity.

Figure 2.

The stomach as shown with upper GI contrast study after laparoscopic reduction, Nissen fundoplication and gastrostomy tube placement. The balloon of the G-tube can be visualized within the gastric lumen, and the fundal wrap can be seen in its superior position.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

Using standard laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication port placement, all four cases of organoaxial gastric volvulus were reduced without difficulty. The etiologies of these four cases were 1) left diaphragmatic eventration, 2) massive hiatal hernia, and 3) two paraesophageal hernias. The hernia sac was carefully dissected out of the mediastinum and excised completely. The short gastric vessels and any adhesions were divided with a harmonic scalpel (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson Corp., Somerville, NJ). The diaphragmatic crura were reapproximated posteriorly. The Nissen fundoplication was wrapped over a combination of a 40 french lighted bougie and an 18 french nasogastric orogastric tube for a total of 58 french. The stomach was evaluated intraoperatively and, if it would continue to volvulize, a gastrostomy tube was placed laparoscopically to fix the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall. Gastrostomy tube placement was performed in three of the four patients and was fastened using T-fasteners (Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH).

The average operative time was 171 minutes (2 hours, 51 minutes), with a range of 138-210 minutes. The average blood loss was 113 cc with a range of 0-200 cc. The patients were started on a clear, non-carbonated liquid diet as soon as they were able to tolerate a diet, usually 6-12 hours postoperatively. They were then quickly advanced to a full liquid diet and maintained on this for 2-3 weeks after discharge, at the discretion of the attending surgeon (P.D.P.). This was done to avoid the postoperative dysphagia seen frequently after fundoplication and to eliminate the possibility of food bolus impaction during the early postoperative period. We hoped this would help prevent retching and/or vomiting that could potentially disrupt the repair, which by its very nature is under more tension than routine laparoscopic fundoplication. There were no intraoperative complications, and three of the four patients were discharged within 1-3 days postoperatively. As mentioned previously, one patient had a cardiac dysrhythmia that precluded an early discharge.

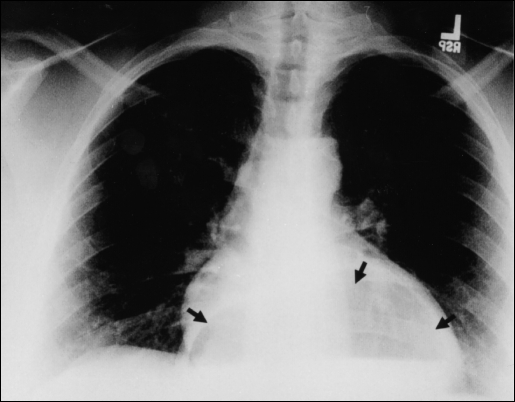

DISCUSSION

Adults with acute gastric volvulus typically present with severe epigastric pain and distention, unproductive vomiting and difficulty with nasogastric tube insertion. This triad of symptoms is known as Borchardt's triad.1 Carter et al2 added additional clinical features that include the following: 1) minimal abdominal findings when volvulus is intrathoracic; 2) gas-filled viscus in the lower chest or upper abdomen as seen on chest radiograph (Figures 3 and 4); and 3) obstruction seen on upper GI contrast studies at the site of the volvulus.

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph showing air-filled viscus in an intrathoracic position behind the cardiac silhouette (black arrows).

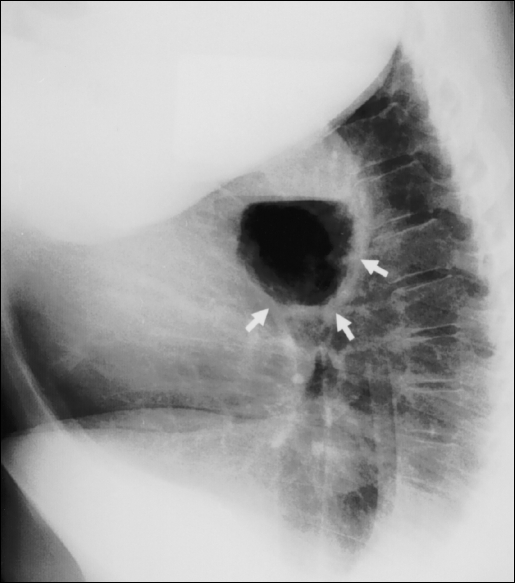

Figure 4.

Lateral chest radiograph showing the same air-filled radiograph showing the same air-filled viscus in an intrathoracic position behind the heart (white arrows).

A chronic gastric volvulus can present with atypical chest pain, anemia (most likely due to Cameron erosions), weight loss, dyspnea and reflux. When the stomach is in the normal anatomic position, it is anchored by the gastrocolic, gastrosplenic, gastrohepatic and gastroduodenal ligaments. The gastrosplenic and/or gastrocolic ligaments can become stretched, attenuated, and redundant and, following certain operative procedures, transected. When this occurs, the stomach can then rotate more than 180° and form a volvulus.3

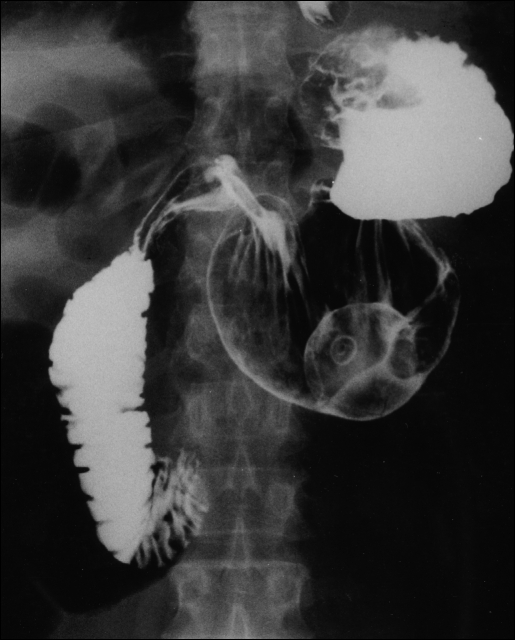

A primary gastric volvulus occurs spontaneously as a result of ligamentous lengthening. More commonly, secondary volvulus occurs due to diaphragmatic defects or other intra-abdominal factors such as left diaphragmatic eventration, adhesions, gastric ulceration and gastric or duodenal carcinoma. The three types of gastric volvulus are organoaxial, mesenteroaxial and a combination of these two. The most common type, organoaxial volvulus, rotates along the cardiopyloric axis with two sites of obstruction. When associated with a large diaphragmatic defect, the greater curvature rotates upward into the defect, creating an “upside down” stomach (Figure 5). This type is most commonly associated with a large hiatal hernia and left diaphragmatic eventration. The mesenteroaxial volvulus, accounting for approximately one-third of gastric volvuli, occurs when the stomach rotates around a transverse axis at the pyloroantral area resulting in the pyloric/antral portions becoming anterior to the stomach. The combination volvulus is rarely encountered.

Figure 5.

The stomach as it appears after upper GI contrast study showing an organoaxial volvulus (“upside-down stomach”). Note position of the nasogastric tube as it courses through the gastroesophageal junction below the diaphragm and turns 180° back into the thoracic cavity.

The basic surgical dictum for the treatment of gastric volvulus includes decompression of the stomach with reduction of the volvulus, gastropexy and correction of the intra-abdominal factors predisposing to volvulus. Sometimes decompression of the stomach with a nasogastric tube will result in reduction of the volvulus, as reported by Llaneza and Salt.4 Reduction of the volvulus can be performed by endoscopy or by gentle traction on the stomach during surgery. Gastric resection would be necessary only if full-thickness necrosis were present.

Many variations of gastropexy, some with multiple points of fixation, have been reported in the literature. Simple gastric fixation to the anterior abdominal wall, gastrostomy tube placement or suturing the lesser curvature to the ligamentum teres or the free edge of the liver can accomplish gastropexy. Other variations include posterior fixation of the greater curvature to the parietal peritoneum and colonic mesentery or fixation of the fundus to the undersurface of the diaphragm. Definitive procedures include gastropexy with colonic displacement (Tanner's procedure),5 fundoantral gastrostomy (Oozler's operation), gastrojejunostomy and gastrocolic disconnection.

There has been debate in the literature concerning the indications of an additional anti-reflux procedure when repairing a diaphragmatic defect. Paraesophageal hernias, which have a normally located esophagus and functioning esophagogastric junction, are often thought to be the common diaphragmatic defect associated with gastric volvulus. On the contrary, Pearson observed that only 1 of 53 patients with massive incarcerated hiatal hernias at laparotomy actually had a true paraesophageal hernia, and 43 of 53 had symptomatic reflux.6 Pearson believes an anti-reflux procedure should be performed routinely in such cases. We agree with this, since Nissen fundoplication usually stops recurrent volvulus secondary to the wrap and pexy of the wrap and/or stomach.

Endoscopic treatment of chronic and acute gastric volvulus is well documented in the literature. Until Tsang and Walker described the alpha-loop maneuver, the J-type maneuver was the most commonly described in the endoscopy literature.7 The newer maneuver involves forming an alpha-loop in the proximal stomach, then advancing the tip of the endoscope into the antrum and duodenum. The endoscope is then torqued in a clockwise manner to uncoil the alpha-loop and reduce the gastric volvulus. Tsang and Walker reduced seven of the eight cases of acute gastric volvulus using the alpha-loop maneuver, followed by surgical repair 1 to 38 days later.7

Gastrostomy tube placement can be employed to pex the stomach and decrease the incidence of recurrent volvulus. Eckhauser and Ferron used dual percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes placed anteriorly in the antrum and anterolaterally in the body of the stomach for a patient with idiopathic mesenteroaxial gastric volvulus.8 A solitary PEG tube could potentially create a new point of fixation for a recurrent volvulus. Bhasin endoscopically reduced the volvulus in 10 patients with chronic gastric volvulus without performing any PEG placement.9 With follow-up from 5 to 26 months, three cases eventually recurred and required surgical treatment. This experience led Bhasin to recommend surgical treatment for secondary volvulus, failed endoscopic reduction and recurrent volvulus.

Laparoscopic and endoscopic techniques have also been combined. Koger and Stone10 reported laparoscopic reduction of an acute organoaxial gastric volvulus due to a paraesophageal hernia. This was followed by broad gastropexy using three pull-type PEG tubes along the greater curvature of the fundus, body and antrum.10 The PEG tubes were removed two months postoperatively, and a follow-up upper GI showed adequate fixation of the stomach. Other variations of laparoscopic gastropexy have been performed using T-fasteners (Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, Ohio),11 as well as intracorporeal suturing.12 The natural progression in the treatment of gastric volvulus has led to a total laparoscopic approach without compromising the basic tenets of the standard laparotomy repair.

CONCLUSION

Experience from our four cases of gastric volvulus has shown that a laparoscopic approach with excision of the hernia sac, reapproximation of the diaphragmatic crura, an anti-reflux procedure and laparoscopic gastrostomy tube placement, when indicated, has been tolerated by all of our patients. The laparoscopic gastrostomy tube secures the stomach intra-abdominally and helps prevent migration of the stomach to an intrathoracic position. Complete excision of the hernia sac can help eliminate one cause for recurrence, as described by Williamson and Ellis.13 As the advancement of laparoscopic techniques continues, there will be less need for a combined endoscopic reduction and laparoscopic gastropexy, which remains a viable option in the high-risk patient. This combined approach ignores one of the basic tenets in the treatment of gastric volvulus by failing to repair the diaphragmatic defect, leaving the potential for recurrent hernia as well as recurrent volvulus. Certainly, endoscopic maneuvers to reduce an acute volvulus, such as the alpha-loop or J-type techniques, are vital in the treatment of these patients. We strongly recommend repair of the diaphragmatic defect along with an anti-reflux procedure. Care should be taken to evaluate the stomach in its intra-abdominal position. If it is likely that recurrent volvulus will occur, the stomach should be pexed to the anterior abdominal wall with a gastrostomy tube. Since there is a low morbidity associated with a minimally invasive surgical approach to gastric volvulus, we advocate laparoscopic reduction and repair of this rare clinical condition.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank Janet L. Tremaine, ELS, for editorial assistance and Christine Merrill for preparation of the photographs.

References:

- 1. Borchardt M. Zun pathologie and therapy des magnevolvulus. Arch Klin Chir. 1904;74:243–248 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carter R, Rewer LA, Hinshaw DB. Acute gastric volvulus. Am J Surg. 1980;140:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dalgaard JB. Volvulus of the stomach. Acta Clin Scand. 1952;103:131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llaneza PP, Salt WB. Gastric volvulus more common than previously thought. Postgrad Med. 1986;80:279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanner CA. Chronic and recurrent volvulus of the stomach. Am J Surg. 1968;115:505–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pearson FG. Massive hiatal hernia with incarceration: a report of 53 cases. Ann Thoracic Surg. 1983;35:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsang TK, Walker R. Endoscopic reduction of gastric volvulus: the alpha-loop maneuver. Gastro Endosc. 1985;42(3):244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eckhauser ML, Ferron JP. The use of dual percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (DPEG) in the management of chronic intermittent gastric volvulus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31(5):340–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhasin DK. Endoscopic management of chronic organoaxial volvulus of the stomach. Am J Gastro. 1990;85(11):1486–1488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koger KE, Stone JM. Laparoscopic reduction of acute gastric volvulus. Am Surg. 1993;59(5):325–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beqiri A, Vanderkolk WE. Combined endoscopic and laparoscopic management of chronic gastric volvulus. Gastro Endosc. 1997;46(5):450–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Umehara Y, Kimura T, Okubo T, et al. Laparoscopic gastropexy in a patient with chronic gastric volvulus. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2:261–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williamson WA, Ellis FH. Paraesophageal hiatal hernia: Is an antireflux procedure necessary? Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]