Abstract

Gastropexy via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy has been used for fixation of the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall in patients with hiatal hernias who are poor candidates for more extensive procedures. Altered anatomic relationship of the stomach to other intra-abdominal organs and the abdominal wall may prevent safe placement endoscopically. Visualizing and manipulating the stomach with laparoscopy enables the surgeon to complete the procedure and diminishes the risk of injury to the adjacent organs without compromising the minimally invasive approach.

Keywords: Hiatal hernia, Laparoscopy, Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

INTRODUCTION

Type II and III hiatal hernias are associated with dysphagia, regurgitation, chronic blood loss and can be complicated by gastric volvulus, strangulation and perfo-ration. For these reasons, type II hernias with an upside-down stomach and type III hernias should be repaired.1 Debilitated patients who are poor candidates for surgical repair may still require nutritional support via the enteral route. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in these patients can provide access for feeding as well as fixation of the stomach to the abdominal wall, possibly preventing further migration into the chest.2 In patients with adhesion formation or altered anatomic position of the stomach, safe PEG placement may be impossible. We report a patient with a large paraesophageal hernia who had a significant portion of the stomach herniating into the chest and a history of previous abdominal surgery. Visualizing the peritoneal cavity with laparoscopy allowed safe placement of a PEG tube in this patient.

CASE REPORT

An 85-year-old male with a past medical history of seizure disorder, stroke, gout and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted with dysphagia and malnutrition. He was a nursing home resident with depressed level of consciousness and a history of heartburn in the distant past, which according to relatives was relieved with antacids. There were no episodes of aspiration. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and an upper gastrointestinal series revealed a type III hiatal hernia (Figure 1). A large portion of the stomach was in the left hemithorax. The patient had a jejunostomy tube in 1997 that was accidentally dislodged several weeks prior to his admission and was never replaced. He had also undergone open cholecystectomy in 1994. After discussing the potential treatment options and in view of his poor medical condition, the patient and his family requested placement of a feeding tube for nutritional support without repair of the paraesophageal hernia. The patient was taken to the operating room, placed supine on the table under general endotracheal anesthesia, and two pillows were placed under his left shoulder and flank. The abdomen was prepped, and the gastroscope was inserted. The room lights were dimmed but transillumination throughout the abdominal wall was not possible. Finger pressure produced no distinct indentation of the gastric wall. At that point, laparoscopy was performed using the open technique for port insertion through an incision at the umbilicus. A 0-degree scope was used. There were adhesions in the upper abdomen. A 12-mm port was inserted under direct vision along the left anterior axillary line, slightly below the level of the umbilicus. The adhesions were divided using ultrasonically activated shears. The stomach was visualized herniating through an enlarged hiatus into the thoracic cavity. Using an atraumatic grasper, the body of the stomach was partially reduced and retracted in a caudad direction. Maintaining traction on the stomach, transillumination of the gastroscope light was possible through the abdominal wall. Under laparoscopic and gastroscopic visualization, a needle with a sheath was inserted into the stomach (Figures 2 and 3); a wire was passed through the sheath and grasped with a snare placed through the endoscope. The wire was pulled out through the mouth and attached to the tapered end of the PEG tube. The tube was then pulled through the mouth, the stomach wall and the anterior abdominal wall. The gastric and anterior abdominal wall were apposed without tension (Figure 4); the position of the mushroom appeared satisfactory through the gastroscope, and the catheter was secured in place. Feedings were initiated on postoperative day one. There were no postoperative complications, and the PEG is functioning well six months after the procedure. The patient has minimal intake by mouth, and his nutritional needs are meet entirely through tube feedings.

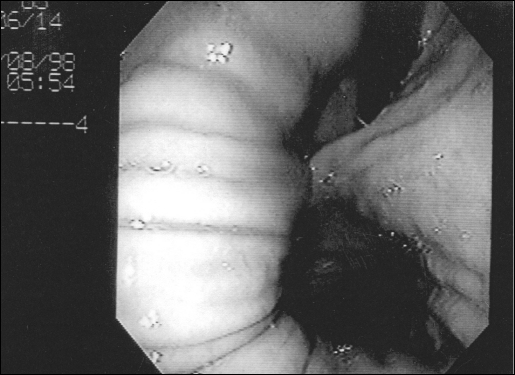

Figure 1.

The gastroscope is retroflexed, and part of the stomach is visualized herniating through the hiatus.

Figure 2.

Puncture of the gastric wall under direct vision through the laparoscope.

Figure 3.

The needle is observed entering the gastric lumen; the transillumination of the laparoscope light is visible through the wall of the stomach.

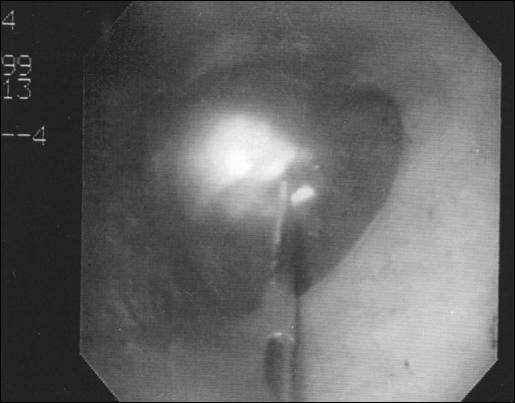

Figure 4.

The stomach and the anterior abdominal wall are in apposition.

DISCUSSION

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy as described by Ponsky and Gauderer3 achieves feeding access without the need for laparotomy. It is necessary to have direct apposition of the anterior gastric wall to the parietal peritoneum prior to proceeding with needle puncture. Transillumination of the endoscope light through the abdominal wall and indentation of the gastric wall with external pressure help the endoscopist identify the insertion site. When this is not possible, it is unsafe to proceed. Intra-abdominal adhesions, interposition of the colon between the stomach and the abdominal wall or migration of the stomach into a hiatal hernia sac, as was the case in our patient, can prevent PEG placement. The use of laparoscopy permits visualization and manipulation of the stomach and division of adhesions, minimizing the possibility of colonic injury.4,5 Especially in patients with paraesophageal hernias, a small portion of the stomach is in the abdominal cavity so the gastric wall cannot be brought into apposition with the parietal peritoneum by insufflating the stomach. Visualizing the stomach through the laparoscope and using traction to reduce it, then bringing it back into the abdomen, allows the needle puncture to be made under direct vision, both through the gastroscope and the laparoscope. The stomach tends to migrate back into the hernia sac if no traction is exerted on it. After placement of the gastrostomy tube, it is anchored to the anterior abdominal wall, diminishing the risk of volvulus6–9 without, of course, correcting the pathology of a paraesophageal hernia. Although two or three percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomies have been used for fixation,2,7 gastropexy with a single gastrostomy tube has been reported to be sufficient in the management of gastric volvulus.8,10 This is a simple and safe means of providing feeding access in patients who cannot undergo a PEG or who can potentially benefit from tethering the stomach to the abdominal wall and are not candidates for formal repair of a paraesophageal hernia. Since it does not address the pathology at the hiatus, symptoms of dysphagia or reflux may not improve, although the gastropexy should prevent further migration of intra-abdominal organs in the chest.

References:

- 1. Duranceau A, Jamieson GG. Hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux. In Sabiston DC, ed. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, Fifteenth Edition. Philadephia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1997:767–784 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Januschowski R. Endoscopic repositioning of the upside-down stomach and its fixation by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1996;11:121(41):1261–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ponsky JL, Gauderer MW. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a nonoperative technique for feeding gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:9–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scheer MF, Miedema BW. Laparoscopic-assisted percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995:5(6):4830–486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paaf JH, Manney M, Okafor E, Gray L, Chari V. Laparoscopic placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3(4):411–4142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ghosh S, Palmer KR. Double percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy fixation: an effective treatment for recurrent gastric volvulus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(8):1271–1272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Altenwerth FL. Treatment of an intermittent stomach volvulus using gastropexy via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1994;119(48):1658–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tang TK, Johnson YL, Pollack J, Gore RM. Use of single percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in management of gastric volvulus in three patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(12):2659–2665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baudet JJ, Armegol-Miro JR, Medina C, Accarino AM, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy as a treatment for chronic gastric volvulus. Endoscopy. 1997;29(2):147–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newman RM, Newman E, Kogan Z, Stien D, Falkenstein D, Gouge TH. A combined laparoscopic and endoscopic approach to acute primary gastric volvulus. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1997;7(3):177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]