Abstract

Background

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are common complications following surgery and anaesthesia. Drugs to prevent PONV are only partially effective. An alternative approach is to stimulate the P6 acupoint on the wrist. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2004.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of P6 acupoint stimulation in preventing PONV.

Search strategy

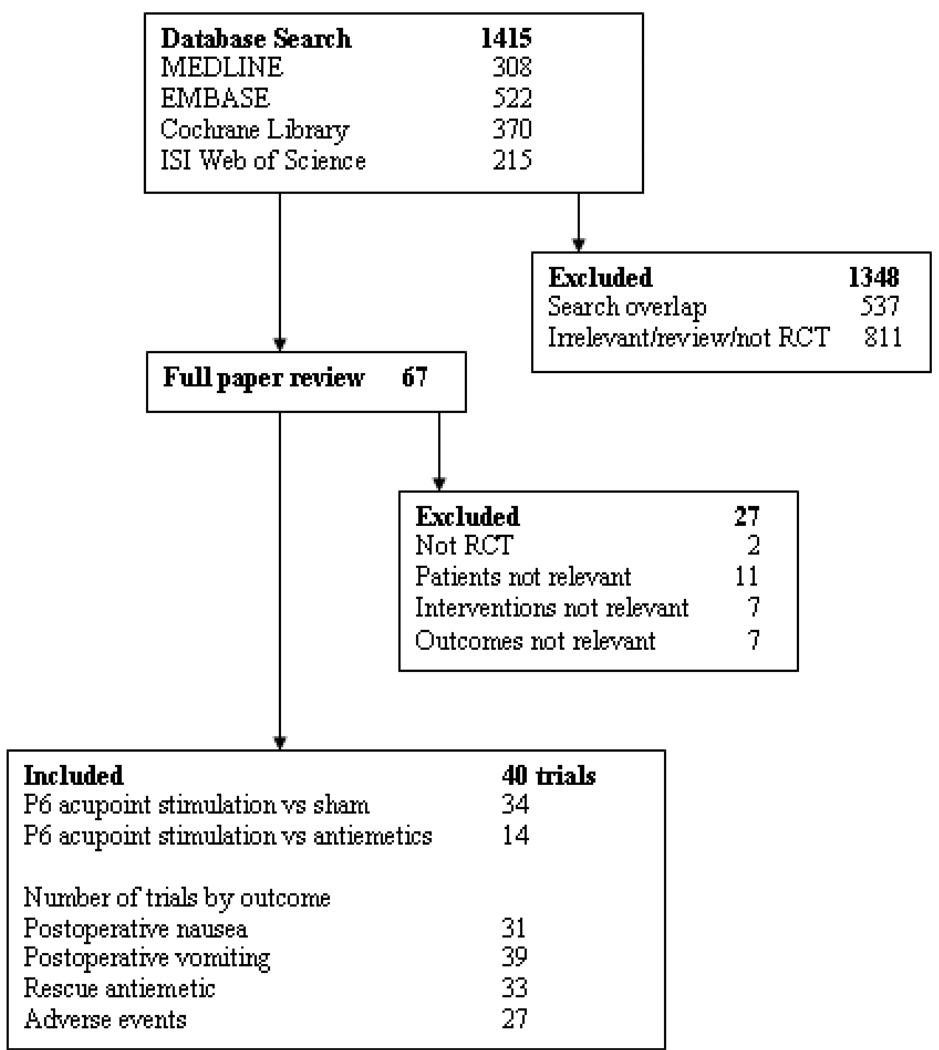

We searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2008), MEDLINE (January 1966 to September 2008), EMBASE (January 1988 to September 2008), ISI Web of Science (January 1965 to September 2008), the National Library of Medicine publication list of acupuncture studies, and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

All randomized trials of techniques that stimulated the P6 acupoint compared with sham treatment or drug therapy for the prevention of PONV. Interventions used in these trials included acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, transcutaneous nerve stimulation, laser stimulation, capsicum plaster, an acu-stimulation device, and acupressure in patients undergoing surgery. Primary outcomes were the risks of nausea and vomiting. Secondary outcomes were the need for rescue antiemetic therapy and adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted the data. We collected adverse effect information from the trials. We used a random-effects model and reported relative risk (RR) with associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Main results

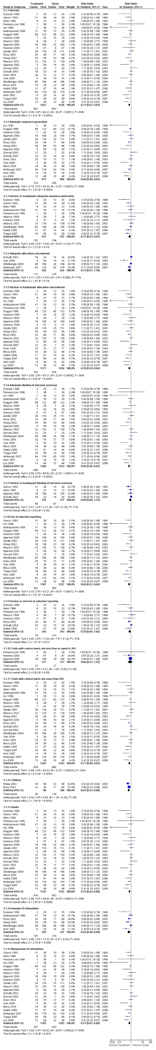

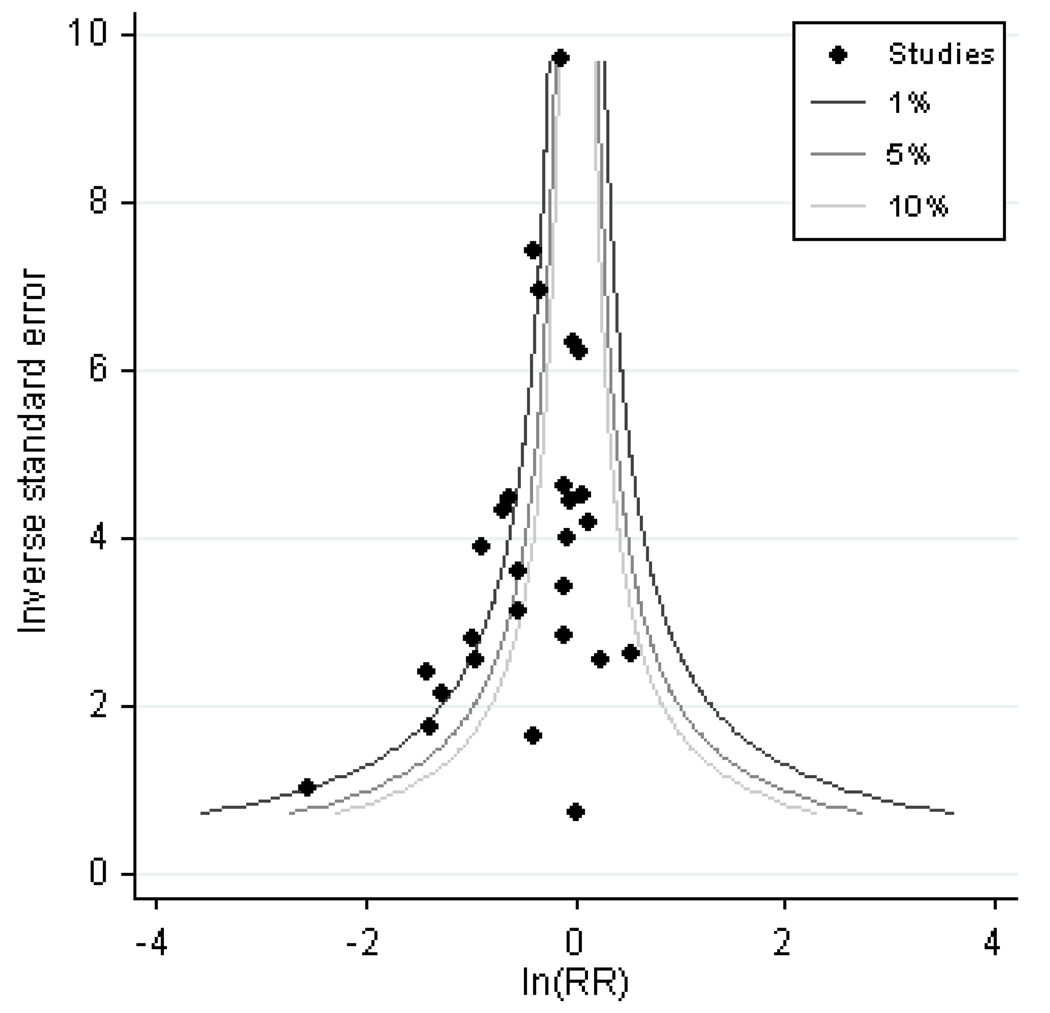

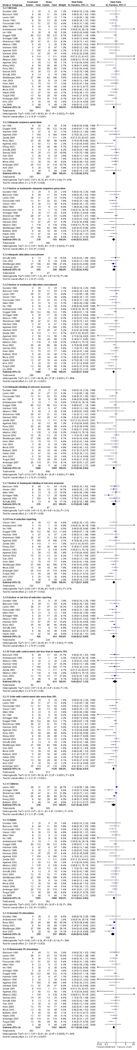

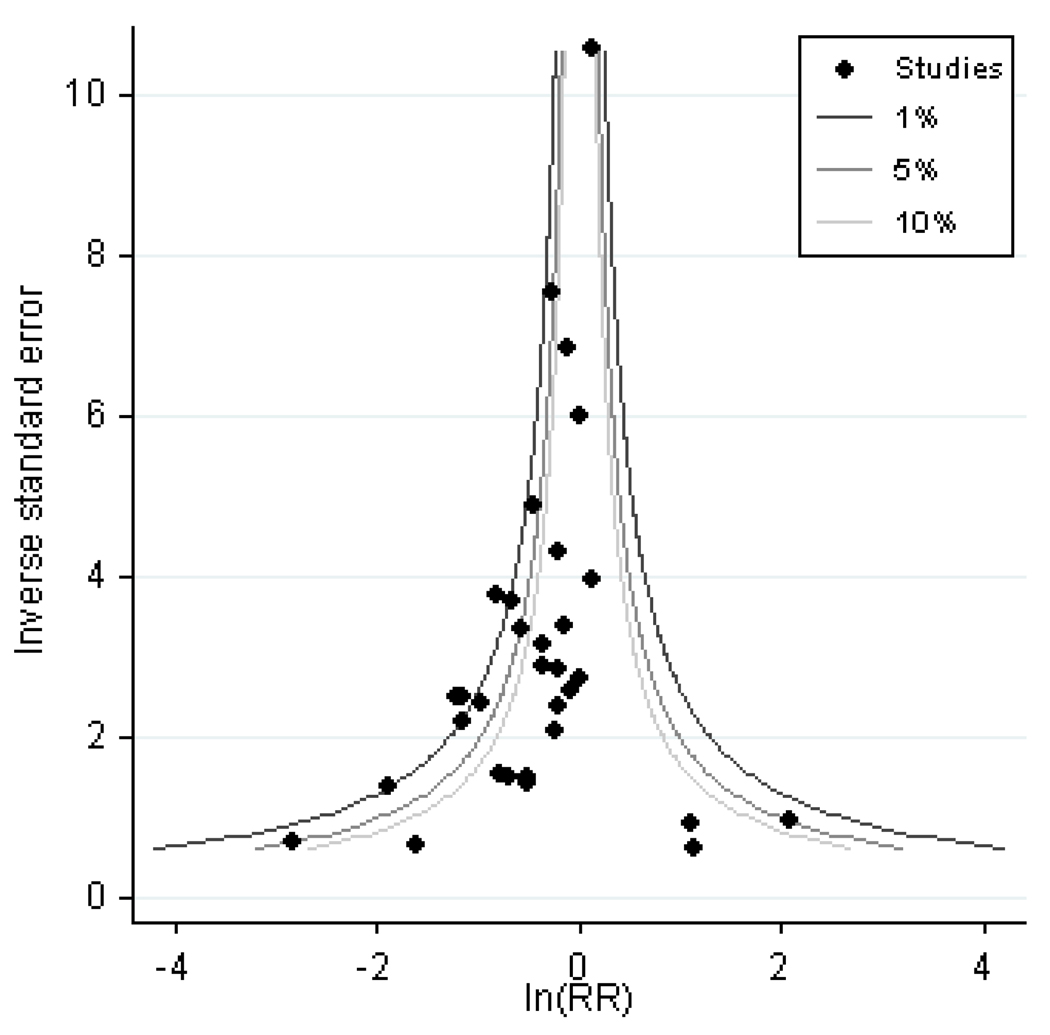

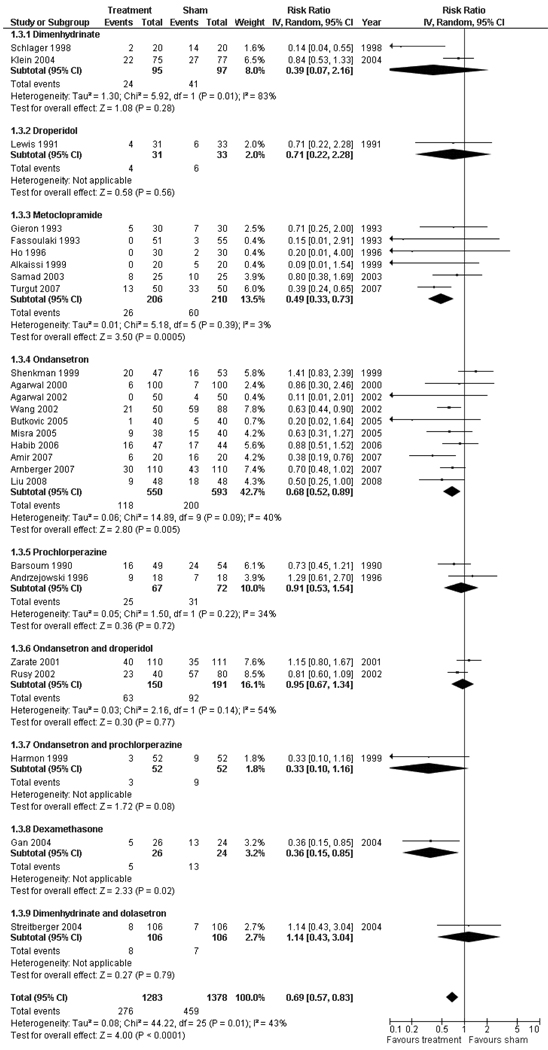

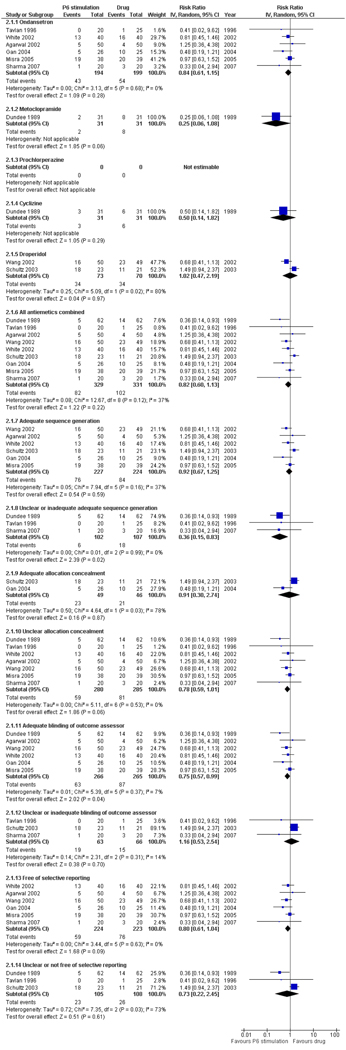

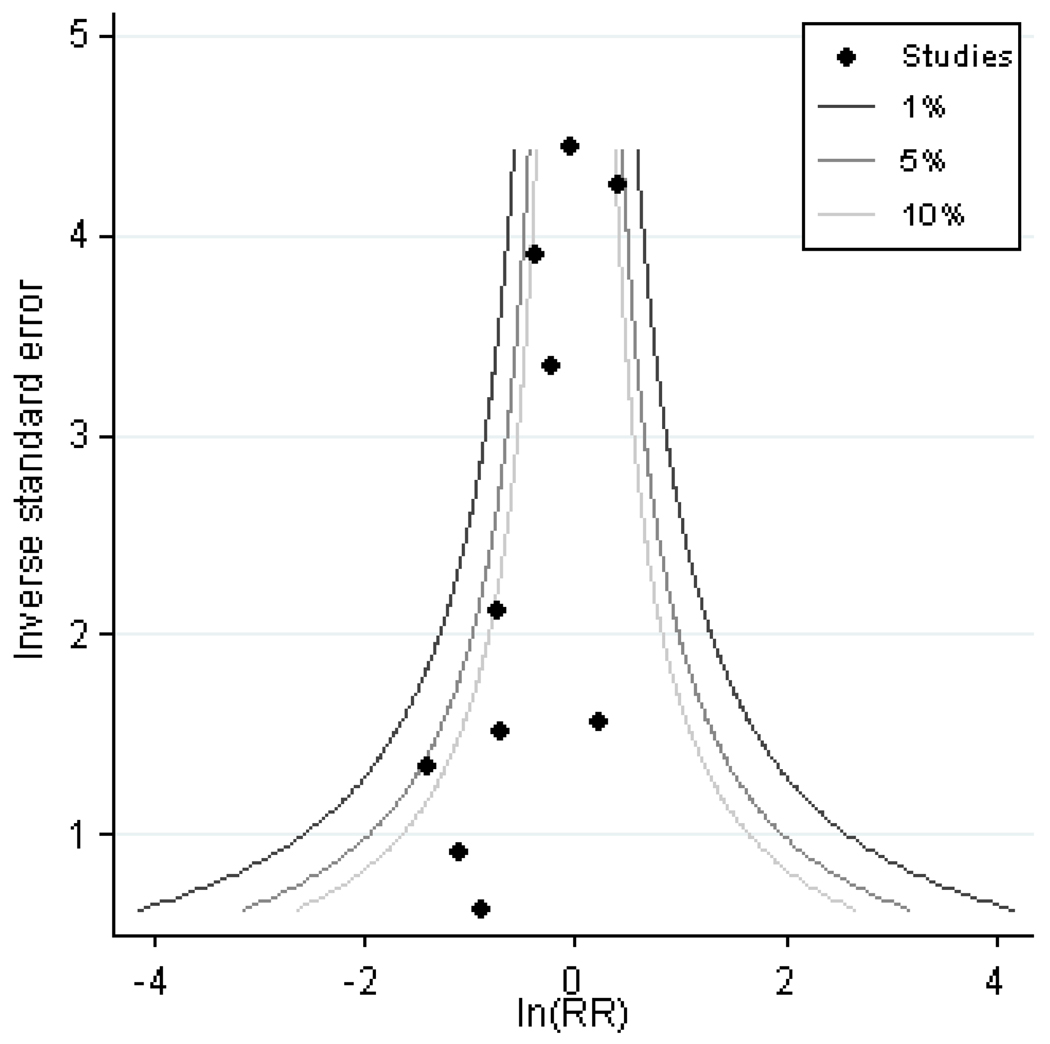

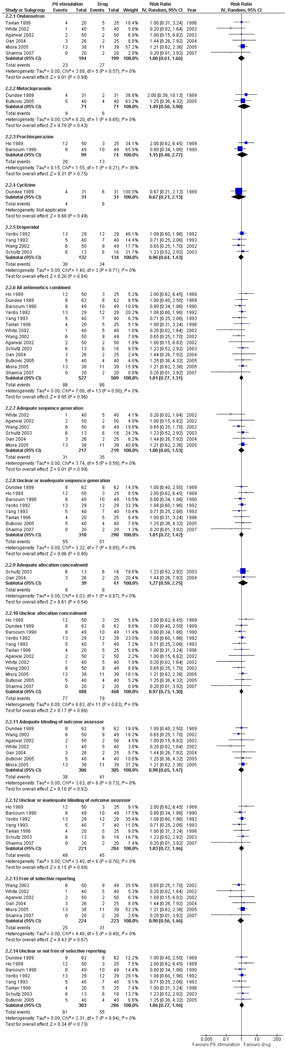

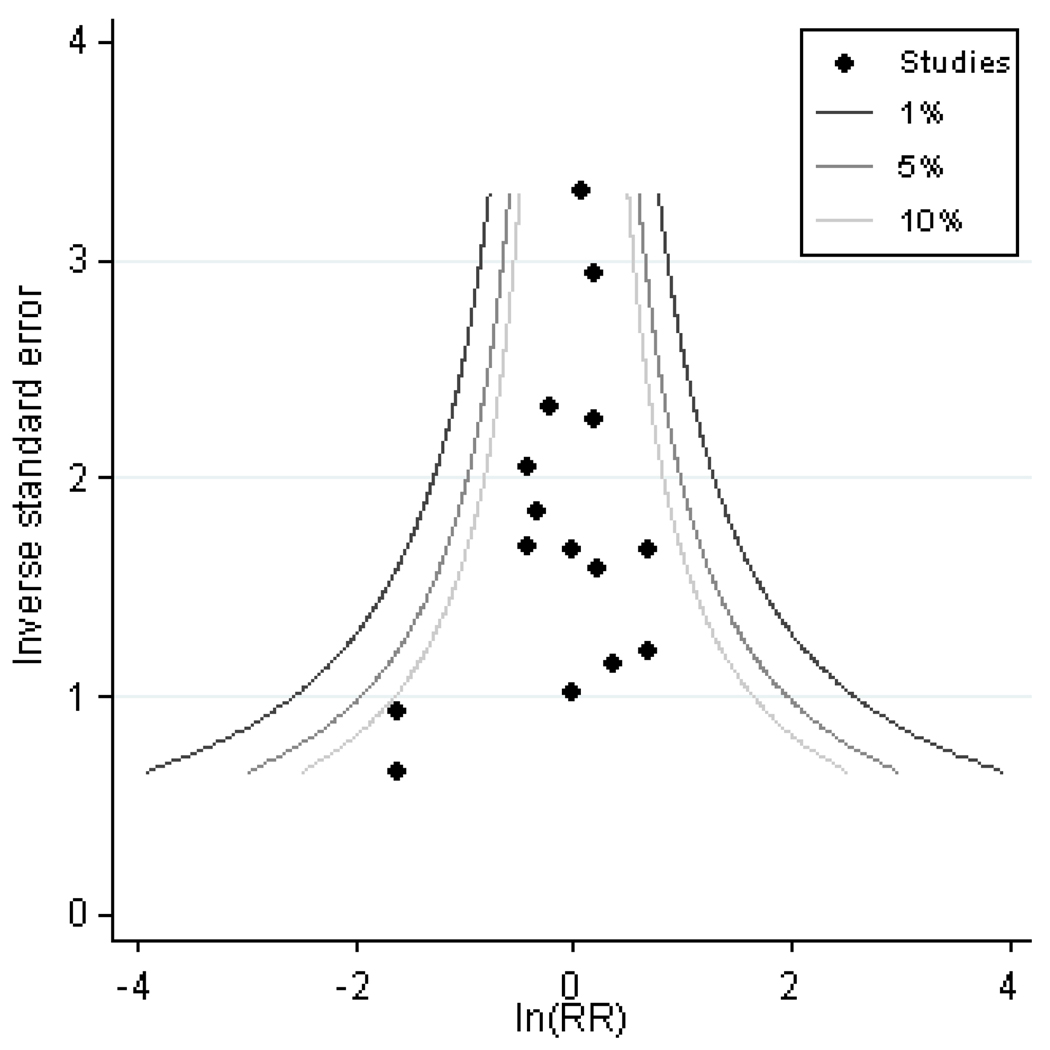

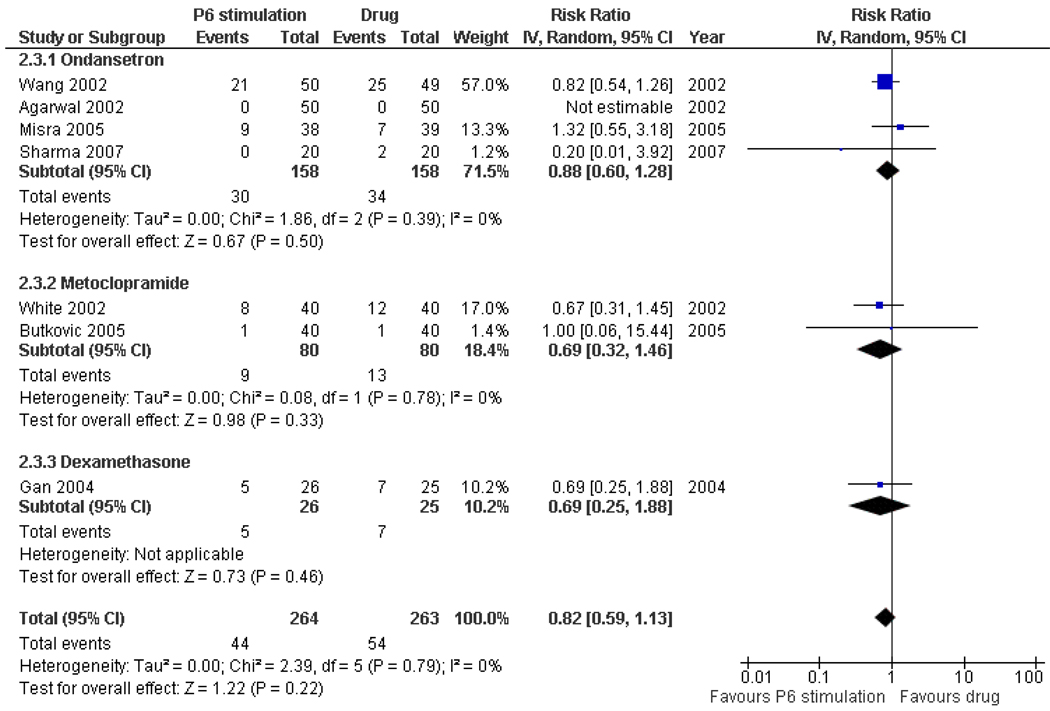

We included 40 trials involving 4858 participants; four trials reported adequate allocation concealment. Twelve trials did not report all outcomes. Compared with sham treatment P6 acupoint stimulation significantly reduced: nausea (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.83); vomiting (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.83), and the need for rescue antiemetics (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.83). Heterogeneity among trials was moderate. There was no clear difference in the effectiveness of P6 acupoint stimulation for adults and children; or for invasive and noninvasive acupoint stimulation. There was no evidence of difference between P6 acupoint stimulation and antiemetic drugs in the risk of nausea (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.13), vomiting (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.31), or the need for rescue antiemetics (RR 0.82, 95%CI 0.59 to 1.13). The side effects associated with P6 acupoint stimulation were minor. There was no evidence of publication bias from contour-enhanced funnel plots.

Authors’ conclusions

P6 acupoint stimulation prevented PONV. There was no reliable evidence for differences in risks of postoperative nausea or vomiting after P6 acupoint stimulation compared to antiemetic drugs.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Acupuncture Points, *Wrist, Antiemetics [therapeutic use], Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting [*prevention & control], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Humans

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

P6 acupoint stimulation prevents postoperative nausea and vomiting with few side effects

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are two of the most common complications after anaesthesia and surgery. Drugs are only partially effective in preventing PONV and may cause adverse effects. Alternative methods, such as stimulating an acupuncture point on the wrist (P6 acupoint stimulation), have been studied in many trials. The use of P6 acupoint stimulation can reduce the risk of nausea and vomiting after surgery, with minimal side effects. The risks of postoperative nausea and vomiting were similar after P6 acupoint stimulation and antiemetic drugs.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON [Explanation]

| Acupoint P6 stimulation versus sham to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with a desire to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Settings: Surgery | ||||||

| Intervention: Acupoint P6 stimulation versus sham | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Acupoint P6 stimulation versus sham | |||||

| Nausea - All trials | Low risk population1 |

RR 0.71 (0.61 to 0.83) |

2962 (27) |

⊕⊕⊕○ moderate2 |

||

| 100 per 1000 |

71 per 1000 (61 to 83) |

|||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 |

284 per 1000 (244 to 332) |

|||||

| Vomiting - All trials | Low risk population1 |

RR 0.7 (0.59 to 0.83) |

3385 (32) |

⊕⊕⊕○ moderate2 |

||

| 100 per 1000 |

70 per 1000 (59 to 83) |

|||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 |

280 per 1000 (236 to 332) |

|||||

| Rescue antiemetics | Medium risk population |

RR 0.69 (0.57 to 0.83) |

2661 (26) |

⊕⊕⊕○ moderate2 |

||

| 363 per 1000 |

250 per 1000 (207 to 301) |

|||||

| Adverse effects3 | See comment | See comment | Not estimable3 | - | See comment | |

The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio;

GRADE Working Group grades of evidance

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

No risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting typically have control rates of 10%; most studies in this systematic review had high risk patients with two or more risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting, therefore we assumed a risk of 40%.

Unexplained moderate heterogeneity among trials even after subgroup analyses.

The tolerability of P6 acupoint stimulation was good with no complaints of side effects in 12 studies (1328 participants). Other self-limiting minor side effects in a few patients from other studies were: redness, irritation and haematoma at puncture site with acupuncture; swollen wrists, red indentation, itching and blistering at the site of the wristband stud; fatigue with electro-acupuncture; mild irritation at the site of capsicum plaster application.

BACKGROUND

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are common complaints after general, regional, or local anaesthesia (Watcha 1992), with incidences up to 80% (Sadhasivam 1999). Drug therapy is only partially effective in preventing or treating PONV (Gin 1994). A systematic review of antiemetic drugs for PONV (Carlisle 2006) showed that eight drugs effectively prevented PONV when compared to placebo: droperidol, metoclopramide, ondansetron, tropisetron, dolasetron, dexamethasone, cyclizine, and granisetron. The relative risks varied between 0.60 and 0.80, depending on the drug and the outcome (Carlisle 2006). Evidence for side effects was sparse: droperidol was sedative (RR 1.32) and headache was more common after ondansetron (RR 1.16) (Carlisle 2006). More recently, a multidisciplinary panel of experts produced guidelines for the prevention or minimization of PONV using prophylactic or rescue therapy, either separately or in combination (Gan 2007).

As anaesthetists continue to search for more cost-effective approaches to improving patient outcomes, attention has focused on simple, inexpensive, and non-invasive methods to prevent PONV. Concern about the cost and side effects of drugs has led to interest in the use of alternative approaches to preventing emesis.

Various non-pharmacological techniques have been examined in trials as alternatives to antiemetic drugs; these include acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, laser acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupoint stimulation, acupressure, and capsicum plaster. Most non-pharmacological studies have focused on stimulation of the wrist at the ’Pericardium (P6) acupuncture point’ to reduce nausea and vomiting. The P6 acupoint lies between the tendons of the palmaris longus and flexor carpi radialis muscles, 4 cm proximal to the wrist crease (Yang 1993). The mechanism by which P6 acupoint stimulation prevents PONV has not been established. Other acupoints believed to prevent PONVinclude Shenmen (H7) (Ming 2002) and Shang Wen (CV13) (Somri 2001).

Both the role and efficacy of P6 acupoint stimulation in the prevention of PONV are unclear. For example, P6 acupoint stimulation significantly reduced the risk of PONV in some studies (Amir 2007; Butkovic 2005; Ho 1996; Rusy 2002; Turgut 2007; Wang 2002) but not in others (Agarwal 2000; Allen 1994; Barsoum 1990; Misra 2005; Shenkman 1999). One systematic review (Vickers 1996), using a ’vote counting’ approach, suggested that acupuncture may not be effective in the prevention of PONV. However, the vote counting approach is not considered an acceptable method of summarizing the results of a systematic review (Petitti 1994).

Our previous systematic review of trials (Lee 1999), including trials published up to 1997, showed no difference between P6 acupoint stimulation and commonly used antiemetic drugs in preventing PONV after surgery. This review also indicated that the technique was more effective than placebo (sham treatment or no treatment) in preventing PONV in adults but not in children. However, these results in children were questionable as they were based largely on trials in which P6 acupoint stimulation occurred while the central nervous system was depressed by general anaesthesia (White 1999). Another major limitation of our earlier review was that we included both no treatment and sham treatment groups. Therefore, we may have overestimated the treatment effect of P6 acupoint stimulation.

In the earlier version of this Cochrane review (Lee 2004) of 26 trials (n = 3347), we showed that there were significant reductions in the risks of nausea (RR 0.72, 95%CI 0.59 to 0.89), vomiting (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.91), and the need for rescue antiemetics (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.00) in the P6 acupoint stimulation group compared with the sham treatment group. Publication bias may have affected the RR estimated for postoperative nausea but not for vomiting (Lee 2006).

OBJECTIVES

To assess the prevention of nausea, vomiting, or requirement for rescue antiemesis (PONV) by acupoint stimulation.

We assessed whether the risks of PONV were different:

after P6 acupoint stimulation compared to sham treatment, where ’sham treatment’ was defined as either a device applied in a non-P6 location, or any attempt to imitate (give the illusion of) P6 acupoint stimulation;

after P6 acupoint stimulation for adults compared with children;

for invasive P6 acupoint stimulation compared with noninvasive stimulation, where ’invasive P6 acupoint stimulation’ was defined as penetration of the skin at P6 acupoint (with manual rotation of acupuncture needle, electrical stimulation of acupuncture needle) and ’noninvasive P6 acupoint stimulation’ was defined as techniques that did not require skin penetration at the P6 acupoint (acupressure, transcutaneous electrical stimulation, laser directed at P6 acupoint, capsicum plaster at P6 acupoint);

after P6 acupoint stimulation in trials with low risk of bias compared with unclear or high risk of bias;

after P6 acupoint stimulation compared with antiemetic drugs;

after a combination of P6 acupoint stimulation and antiemetic drug compared with sham treatment.

We assessed these effects because the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a statement that ’acupuncture may be useful as an adjunct treatment or an acceptable alternative or included in a comprehensive management program for many medical conditions’ (NIH 1997).

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of techniques intended to stimulate the P6 acupoint, compared with either sham treatment or antiemetic drugs, for the prevention of PONV. ’Sham treatment’ was defined as a device applied in a non-P6 location, or any attempt to imitate (give the illusion of) P6 acupoint stimulation. Therefore, for trials that assessed acupressure wristbands, wristbands without studs placed at the P6 acupoint were considered as adequate sham treatment and these trials were included in the review.

Types of participants

All surgical patients without age limitation. The age limits for children were defined by each study.

Types of interventions

Techniques intended to stimulate the P6 acupoint: acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, laser acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical stimulation, an acu-stimulation device, acupressure, and capsicum plaster; versus sham treatment or drug therapy for the prevention of PONV. These diverse techniques were considered as one entity in the main analysis, consistent with the concept that stimulating the correct acupuncture point is more important than the nature of the stimulus (Mann 1987). There was no restriction on the duration of P6 acupoint stimulation or when it was applied.

Types of outcome measures

We did separate meta-analyses for each of the following primary and secondary outcomes. Trials could report more than one primary or secondary outcome.

Primary outcomes

Risk of postoperative nausea.

Risks of postoperative vomiting. This was defined as either retching or vomiting, or both.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting were not combined as we could not be certain that patients who vomited were also nauseated. If the authors reported several incidences of the outcome measure (for example 0 to 6 hours, 6 to 24 hours, 0 to 24 hours), the longest cumulative follow-up data from the end of surgery were used (in this case, 0 to 24 hours).

Secondary outcomes

Risk of patients requiring a rescue antiemetic drug.

Risk of side effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following for relevant trials.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2008), in Appendix 1.

Electronic databases: MEDLINE (January 1966 to September 2008), in Appendix 2; EMBASE (January 1988 to September 2008), in Appendix 3; ISI Web of Science (January 1965 to September 2008), in Appendix 4; and National Library of Medicine publication list of acupuncture studies (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/cbm/acupuncture.html).

Reference lists of relevant articles, reviews, and trials.

We combined the following MeSH and text words with the filters for identifying randomized controlled trials: ’postoperative complications’, ’nausea and vomiting’, ’acupuncture’, ’acupuncture therapy’, ’acupuncture points’, ’acupressure’, ’transcutaneous electric nerve stimulator’, and ’electro-acupuncture’.

There was no language restriction. We excluded studies of P6 acupoint stimulation to treat established PONV, or to prevent intraoperative nausea or vomiting.

Searching other resources

We did not search for conference proceedings or seek unpublished trials. Grey literature has not been peer-reviewed and there is some evidence that it is of lower quality than published studies (McAuley 2000).

Data collection and analysis

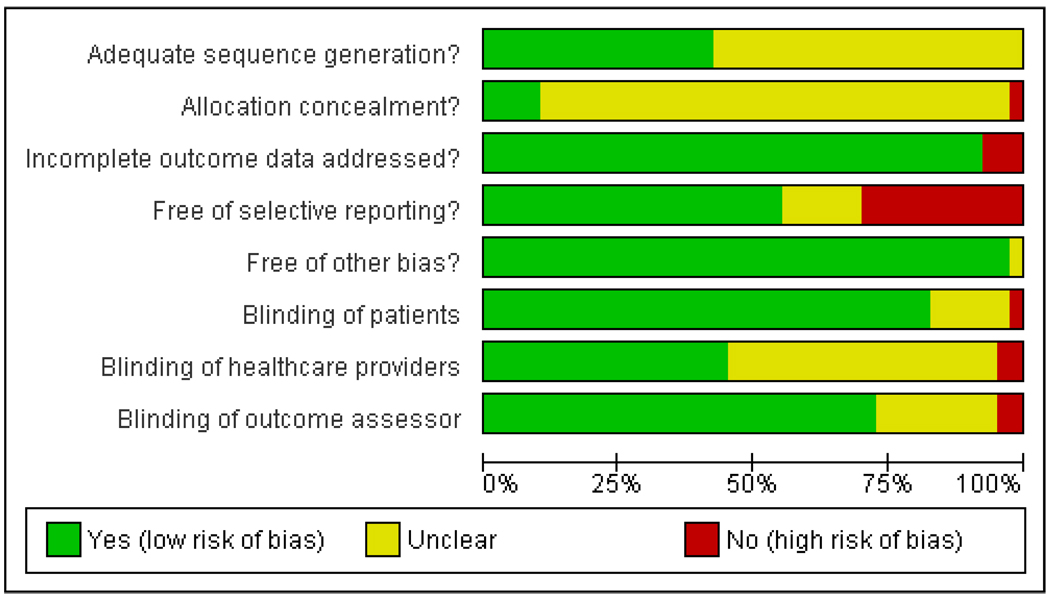

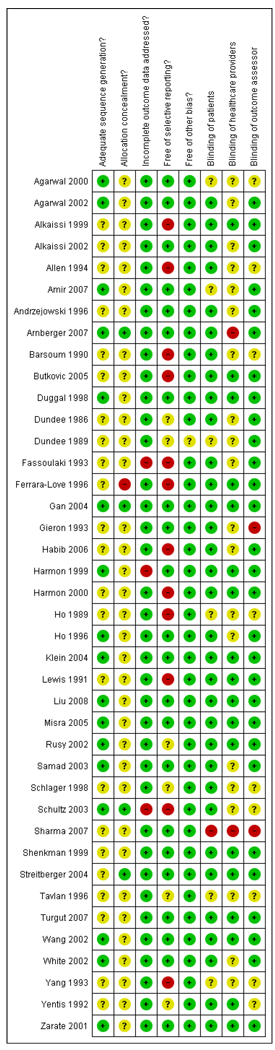

We selected trials identified by our search that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. There was no disagreement between authors about inclusion and exclusion of studies for this review. We examined all selected trials for duplicate data; where we found duplication, we used the results of the main trial report. We extracted data independently, using a standardized data collection form, and we resolved any discrepancies in data extraction by discussion. We assessed the quality of the included trials independently, under open conditions. We graded the risk of bias for each study in the domains of sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, healthcare providers, and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and comparison of baseline characteristics for each group in a ’Risk of bias’ table (Higgins 2008). We graded each domain as yes (low risk of bias), no (high risk of bias), or unclear (uncertain risk of bias) according to the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

We collected data on the type, duration, and timing of P6 acupoint stimulation, as well as the type and dose of prophylactic antiemetic drug. We recorded details of the patient population and type of surgery. We did not consider factors such as the severity of PONV or the number of episodes of vomiting.

We used the random-effects model to combine data, as we expected that the treatments and conditions in these trials would be heterogeneous. This model incorporates both between-study (different treatment effects) and within-study (sampling error) variability (Mosteller 1996). We calculated the pooled relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI), and analysed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic as a measure of the proportion of total variation in the estimates of treatment effect that is due to heterogeneity between studies. We conducted sensitivity analyses to estimate the robustness of results according to sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessor (adequate versus inadequate or unclear), selective reporting (adequate versus inadequate or unclear), and control event rate (≤ 20%, > 20%). We undertook exploratory a priori subgroup analyses, which included trials in adults versus trials in children and trials according to type of P6 acupoint stimulation (invasive versus noninvasive). To test whether the subgroups were different from one another, we tested the interaction using the technique outlined by Altman and Bland (Altman 2003).

We used the contour-enhanced funnel plot to differentiate asymmetry due to publication bias from that due to other factors (Peters 2008), using STATA statistical software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, version 10). Contour-enhanced funnel plots display the area of statistical significance on a funnel plot (Peters 2008) to improve the correct identification of the presence or absence of publication bias. This was used in conjunction with the ’trim and fill’ method (Duval 2000) to inform the likely location of missing studies, using STATA statistical software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, version 10), as suggested by Peters (Peters 2008). Publication bias would be expected when the usual funnel plot is asymmetrical but assessment of the contour-enhanced funnel plot indicates that missing studies are located where nonsignificant studies would be plotted (Peters 2008).

We estimated the number needed to treat (NNT) for different baseline risk for nausea and vomiting using the RR (Smeeth 1999) to assess whether P6 acupoint stimulation is worthwhile for individuals. We estimated the 95% CI around the number needed to treat using the method outlined by Altman (Altman 1998).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Agarwal 2000 | ||

| Methods | Patients assigned to groups by a computer-generated table of random numbers. All acupressure wristbands were covered with gauze and tape. Outcome assessor blinded to treatment groups. | |

| Participants | 200 patients undergoing endoscopic urological surgery. Exclusion: patient refusal to participate in study, previous history of PONV and motion sickness, impaired renal function with increased urea and creatinine concentrations, diabetes mellitus, obesity, patients receiving antiemetic medication, histamine H2-receptor antagonist within 72 hours of surgery. No patient withdrew from the study. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristband placed at P6 points on both forearms, applied 30 min before induction of anaesthesia and removed after 6 hours following surgery. Sham group was the spherical bead of acupressure wristbands placed on posterior surface, applied 30 min before induction of anaesthesia and removed 6 hours after surgery. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), side effects of acupressure, risk of rescue antiemetic drug. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV. No side effects or complications noted in either group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Patients were assigned to two different groups according to a computer-generated table of random numbers”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | “No patient was excluded after admission to the study”. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable: “Patients were comparable in both the groups as regards to age, sex, height and weight”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Agarwal 2002 | ||

| Methods | Patients assigned using a table of random numbers. Outcome assessor blinded to treatment groups. Acupressure and sham group received normal saline IV before induction to maintain blinding of the treatment groups. | |

| Participants | 150 adults undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Exclusion: patient refusal to participate in study, previous history of PONV and motion sickness, impaired renal function with increased urea and creatinine concentrations, diabetes mellitus, obesity, patients receiving antiemetic medication, histamine H2-receptor antagonist within 72 hours of surgery. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristband placed at P6 points on both forearms, applied 30 min before induction of anaesthesia and removed after 6 hours following surgery (plus normal saline 1 mL IV just before induction of anaesthesia). Sham group was the spherical bead of acupressure wristbands placed on posterior surface, applied 30 min before induction of anaesthesia and removed 6 hours after surgery (plus normal saline 1 mL IV just before induction of anaesthesia). Antiemetic group was ondansetron 4 mg IV just before induction of anaesthesia (plus sham treatment outlined above). |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV if patient vomited more than once. No side effects or complications noted in any of the groups. Data for outcome (0–24h) obtained by correspondence with author. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Patients were randomized into three groups of 50 each using a table of random numbers..”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for 150 patients randomized. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable: “Patients were comparable in both the groups as regards to age, sex, height, weight and duration of surgery”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “The incidence of PONV was evaluated by a blinded observer”. |

| Alkaissi 1999 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Patients were asked to record nausea and vomiting during their stay in hospital and after discharge. Nurses who asked the patients about nausea and administered antiemetics on the postoperative ward were not aware of treatment allocation or where the P6 acupoint was located. | |

| Participants | 60 women undergoing day case minor gynaecological surgery. Exclusion: patients undergoing local anaesthesia and those given prophylactic antiemetic during anaesthesia (n = 10, replaced by randomising another 10 patients at the end of the study). | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristband placed at P6 point on both forearms. Applied before surgery and left on for 24 hours. Draped with a dressing during the stay in the hospital. Sham acupressure applied to dorsal side of forearms. Applied before surgery and left on for 24 hours. Draped with a dressing during the stay in the hospital. Reference group were informed and anaesthetised in the same way as the other two groups. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drugs. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetics were metoclopramide 10 mg IV at patient’s request; if not effective, then given droperidol 1.25 mg IV. Reference group received no treatment and was not included in data analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons were given for 10 dropouts, who were replaced by randomising another 10 patients at the end of the study. “The dropouts were evenly distributed between the groups.” No missing data reported for 60 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Primary outcome (PONV) reported. Description of side effects not given. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Demographic data appeared to be comparable in Table 1. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “The nurses who asked the patients about nausea, and administered antiemetics on the postoperative ward were not aware of which treatment the patient received or where the P6 acupoint is located”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “The nurses who asked the patients about nausea, and administered antiemetics on the postoperative ward were not aware of which treatment the patient received or where the P6 acupoint is located”. These nurses also noted vomiting episodes. |

| Alkaissi 2002 | ||

| Methods | Patients randomized by sealed envelope (not opaque). Patients were asked to record nausea and vomiting. Multicentre trial. Wrists were wrapped with dressing to maintain blinding (but patients may have unwrapped the dressing). | |

| Participants | 410 women undergoing elective gynaecological surgery. No exclusion criteria specified. Thirty patients were withdrawn because they were: given local anaesthesia (n=12), or an antiemetic was given without the criteria for treatment of PONV being met (n=14), malignant hyperthermia (n=1), allergy to latex (n=2), and could not read Swedish (n=1). These 30 patients were replaced by another 30 at the end of the study period. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristband placed on P6 point on both forearms just before start of anaesthesia, left on for 24 hours. Sham group included acupressure wristbands at non-acupoint on both forearms just before start of anaesthesia, left on for 24 hours. Reference group received no prophylactic treatment and was not blinded. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), side effects of acupressure, risk of rescue antiemetic (type of drug not described) | |

| Notes | Reference group received no treatment and was not included in data analysis. Adverse effects: wristbands felt uncomfortable, produced red indentation, or caused itching, headache and dizziness, or wrists hurt and tightness of wristband caused swelling or deep marks or blistering at site of stud. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons were given for 30 dropouts, who were replaced by randomizing another 30 patients at the end of the study. “Withdrawals were evenly distributed between the groups.” No missing data reported for 410 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Demographic data appeared to be comparable in Table 2. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | “The wrists were wrapped for blinding”. Patients reported outcomes. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “The wrists were wrapped for blinding”. Patients reported outcomes. |

| Allen 1994 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Outcome assessor was anaesthetist. Blinding not mentioned. No patient withdrew from study. | |

| Participants | 46 women undergoing gynaecological surgery. Exclusions: previous exposure to elasticised wristbands for the prevention of motion sickness. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristband placed on P6 point of dominant arm before premedication (90 min before surgery). Duration of treatment not given. Sham acupressure wristband placed on dorsum of dominant wrist before premedication. Duration of treatment not given. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h). | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was prochlorperazine 12.5 mg IM 4 hourly when necessary. More than one dose of prochlorperazine data given (not included in data analysis). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | “No patient refused to participate in the study, nor were there any withdrawals”. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Risk of rescue antiemetic drug (one or more dose) was not given in the results. Description of side effects not reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The ages and weights of the patients in the two groups were comparable..”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar in patients with no previous experience with this form of acupressure. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Amir 2007 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment was not given. Subjects were randomly assigned to groups using computer-generated random number table. Outcome assessor was blinded but no details about blinding for subjects and attending anaesthetist. | |

| Participants | 40 children and adults undergoing middle ear surgery. Patients with cardiovascular disease, central nervous system problems, previous history of PONV and/or motion sickness, and smokers were excluded. No details about withdrawals or loss to follow up. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: electro-acupuncture at frequency of 4 Hz and current intensity increased to a degree just less than what caused discomfort, given 20 min before induction for duration of surgery. Group 2: sham electro-acupuncture. No details given except that patients experienced needle pricks. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug (0–24h), risk of adverse effects. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV after first episode of PONV and repeated when necessary at 6 hourly intervals. No side effects in sham electro-acupuncture group. Erythema occurred in 3 patients in the electro-acupuncture group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Informed consent was taken from the selected patients and they were divided into two groups of twenty each using a computer-generated table of random numbers”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for the 20 patients randomized. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “Differences in mean age, weight, sex and duration of surgery were statistically insignificant”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “A blinded observed collected postoperative data of PONV”. |

| Andrzejowski 1996 | ||

| Methods | Randomization by sealed envelope (not opaque). Patients asked to record nausea and vomiting. | |

| Participants | 36 women undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Exclusions: metal or elastoplast allergy, anticoagulant therapy, local skin disease at P6 acupoint or sham point, or chronic treatment with antiemetics. | |

| Interventions | Semipermanent acupuncture needle inserted at P6 acupoint on both wrists 20 min before induction, left in place until second postoperative day. Sham semipermanent acupuncture needle inserted in sham point 20 min before induction, left in place until second postoperative day. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–8h), vomiting (0–8h), risk of antiemetic rescue drug, side effects. | |

| Notes | Antiemetic rescue was prochlorperazine 12.5 mg IM when necessary. No side effects reported with interventions. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. “Patients were allocated randomly into one of two groups”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. “This was achieved by concealing the assignment schedule in sealed envelopes which were opened by the investigator just before inserting the needles”. Comment: not sure if envelopes were sequentially numbered and opaque. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for 36 patients randomized. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “There was no significant difference between the two groups in age, weight, total morphine consumed, or duration of anaesthesia”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | The assessments were made by the patients, who were blinded to their treatment“. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | The assessments were made by the patients, who were blinded to their treatment”. |

| Arnberger 2007 | ||

| Methods | Patients were assigned to groups using a set of computer-generated random numbers. The assignments were kept in sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes. Patients and outcome assessors were unaware of group assignment. The attending anaesthetist could not be blinded to the group assignment but was not involved in outcome assessments. | |

| Participants | 220 females undergoing elective gynaecological and abdominal laparoscopic surgery of more than 1 hour duration. Exclusion: pregnant and breast-feeding women, and patients with eating disorders, obesity (body mass index > 35kg/m2), severe renal or liver impairment, central nervous system injury, vertebrobasilar artery insufficiency, vestibular disease, cytostatic therapy, and preoperative vomiting or antiemetic therapy. No patient withdrew from study. | |

| Interventions | P6 group: during anaesthesia, neuromuscular blockade was monitored by a conventional nerve stimulator at a frequency of 1Hz over the median nerve (first electrode 1 cm proximal to P6 acupoint and second electrode placed 2 cm distal to the P6 acupoint) on the dominant hand. Sham group: during anaesthesia, neuromuscular blockade was monitored by a conventional nerve stimulator at a frequency of 1Hz over the ulnar nerve (first electrode 1 cm proximal to the point at which the proximal flexion crease of the wrist crosses the radial side of the tendon to the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle at the volar side of the wrist and second electrode placed 3 cm proximal to the distal electrode) on the dominant hand. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug (0–24h), risk of adverse effects. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV if 2 or more episodes of vomiting or persistent nausea; with repetition after 2 hours. No local irritation, redness, contact dermatitis or muscle ache (side effects) were recorded. Nausea (0–6h), vomiting (0–6h), and incidence of rescue antiemetic (0–6h) also reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “After induction of anaesthesia, patients were assigned to one of two groups using a set of computer-generated random numbers”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “The assignments were kept in sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes until used, and the envelope numbers with the assignment were recorded”. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | “Two hundred twenty patients were recruited for this study without any dropout over the observation period”. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “Demographic and morphometric characteristics and factors likely to influence PONV were similar in the two groups (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | “Patients and PONV evaluators were not informed of the group assignments”. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | No | “The attending anaesthesiologist could not be blinded to the group assignment, but he or she was not involved with the PONV assessment”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “Patients and PONV evaluators were not informed of the group assignments”. |

| Barsoum 1990 | ||

| Methods | Randomization by ’envelope system’. No details about whether outcome assessor was blinded or not. Active and inactive acupressure wristbands were worn in the recovery room until discharge from hospital, or for seven days if that was sooner (exact duration of intervention in hours not reported). | |

| Participants | 162 patients undergoing general surgery. Ten patients withdrew because of language or age difficulty with completing analogue score, premature removal of wristbands, and incomplete follow-up data. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristbands placed on P6 acupoint of both wrists in the recovery room. Sham acupressure wristbands (no studs) were applied to both wrists in the recovery room and antiemetics given only if clinically required. Antiemetic group was given prochlorperazine 12.5 mg IM with each postoperative opiate injection and when clinically required, and wore an acupressure band without stud on both wrists in the recovery room. |

|

| Outcomes | Vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic (prochlorperazine). | |

| Notes | Nausea scores were reported for those patients who could not eat. Number of patients who were free of nausea was not given. Vomiting on postoperative day 2 and 3 also reported. Four patients reported some local tightness and discomfort (one of these experienced carpal tunnel like symptoms). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons for withdrawals were given. No missing data reported for the 152 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Severity of nausea was reported but risk of nausea was not. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics appeared to be comparable. “It can be seen that the groups were comparable with regard to the range of operation and anaesthetic agents used”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar and all patients were told that they were wearing wristbands to try to prevent PONV. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Butkovic 2005 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. “Researchers were double-blinded” but no specific details about how blinding was achieved. | |

| Participants | 120 children (5–14 years) undergoing hernia repair, circumcision, or orchidopexy. Exclusion: patients predisposed to nausea and vomiting secondary to gastroesophageal reflux, motion sickness, and inner ear or central nervious system disorders. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: laser acupuncture on P6 acupoint bilaterally for 1 min, 15 min before induction of anaesthesia and IV infusion of saline. Group 2: metoclopramide 0.15mg/kg IV and sham laser on P6 acupoint bilaterally for 1 min, 15 min before induction of anaesthesia. Group 3: sham laser stimulation on P6 acupoint bilaterally for 1 min, 15 min before induction of anaesthesia and saline infusion. |

|

| Outcomes | Vomiting (0–2h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg IV if vomiting was severe. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for the 120 children analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Description of side effects not included. Nausea not reported because it may be difficult to assess in children. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “Demographic data showed no significant difference among groups”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make intervention appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “Researchers were double-blinded” but no specific details about how blinding was achieved. Comment: probably done. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “Researchers were double-blinded” but no specific details about how blinding was achieved. Comment: probably done. |

| Duggal 1998 | ||

| Methods | A table of random numbers was used to allocate patients into treatment groups. Patient, anaesthetist, and investigators were unaware of treatment groups during the study. Patients recorded outcome measures on a questionnaire. | |

| Participants | 263 patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia for elective Caesarean delivery. Excluded: patients with a history of hyperemesis gravidarum or if they had received antiemetic medication during the 48h before surgery. Eight women excluded for failing to wear wristbands for 10 hours, three had received prophylactic antiemetics, and eight were not given standard combination of intrathecal drugs (total 19 withdrawals). | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristbands were applied to both wrists just before induction of spinal anaesthesia and worn for 10 hours. Sham acupressure wristbands were applied at P6 acupoint (but stud missing) on both wrists just before induction of spinal anaesthesia and worn for 10 hours. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–10h), vomiting (0–10h), risk of rescue antiemetic (type of drug not given), side effects of acupressure. | |

| Notes | Adverse effects of acupressure wristbands: tightness, swollen hands, problems with infusion, itching wrists. Intraoperative nausea and vomiting reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “A table of random numbers was used to allocate patients to one of two groups”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons for withdrawals were given. No missing data reported for the 244 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “Demographic analysis revealed no statistically significant difference between subjects in the two groups (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | “The nature of the bands was therefore unknown to the patient, anaesthetist and investigators for the duration of the study”. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “The nature of the bands was therefore unknown to the patient, anaesthetist and investigators for the duration of the study”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “The nature of the bands was therefore unknown to the patient, anaesthetist and investigators for the duration of the study”. |

| Dundee 1986 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Outcome assessor was blinded to treatment groups. | |

| Participants | 75 women undergoing minor gynaecological surgery. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: acupuncture at P6 acupoint with 5 min manual stimulation (1.2 cm 30 gauge needle) after premedication with nalbuphine 10 mg. Group 2: sham acupuncture at a dummy point on lateral elbow crease with 5 min manual stimulation (1.2 cm 30 gauge needle) after premedication with nalbuphine 10 mg. Group 3: no further treatment after premedication with nalbuphine 10 mg. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–6h), vomiting (0–6h), side effects of treatment. | |

| Notes | No side effects noted in either group. Group 3 data were excluded from data-analysis. Presence or absence of needle marks and its location may have been observed by the outcome assessor. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for 75 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | No details about the use of rescue antiemetic in anaesthetic protocol. The risk of rescue antiemetic drug not reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | “The groups were comparable in average age, weight, and duration of anaesthesia”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | The authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “Their assessments were performed by an observer who was unaware of which patients had undergone acupuncture”. |

| Dundee 1989 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Outcome assessor was blinded to treatment group, except where the patient pointed to the P6 acupoint site. | |

| Participants | 155 women undergoing minor gynaecological surgery. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture at P6 acupoint with 5 min manual stimulation after premedication. Electroacupuncture at P6 acupoint for 5 min after premedication. Antiemetic group 1 had cyclizine 50 mg IM after premedication. Antiemetic group 2 had metoclopramide 10 mg IM after premedication. Reference group had no treatment. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–6h), vomiting (0–6h), side effects of treatment. | |

| Notes | For data analysis purposes, manual acupuncture and electro-acupuncture were combined. Reference group received no treatment and was not included in data analysis. This paper reported both controlled and uncontrolled studies of P6 stimulation. Used original data from Dundee JW, Fitzpatrick KTJ, Ghaly RG. Is there a role for acupuncture in the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting? Anesthesiology 1987; 67: 3A P165. This trial appears to be a duplicate of a previous published study: Ghaly RG, Fitzpatrick KTJ, Dundee JW. Antiemetic studies with traditional Chinese acupuncture-a comparison of manual needling with electrical stimulation and commonly used antiemetics. Anaesthesia 1987; 42:1108–10 (note that metoclopramide group was not included in this trial, but the results of other groups are the same). According to the authors, there were no side effects associated with acupuncture groups but some patients complained of drowsiness following antiemetic drug administration. For data analyses, manual acupuncture group was compared with cyclizine, and electroacupuncture group was compared with metoclopramide. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for 155 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | No details about the use of rescue antiemetic in anaesthetic protocol. The riisk of rescue antiemetic drug not reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Demographic comparisons between groups were not given. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “Patients were visited at 1 h and 6 h after operation by a person who was unaware of the preoperative treatment”. |

| Fassoulaki 1993 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator, active or inactive, was covered with dark plastic bags. Outcome assessor was blinded to treatment allocation. | |

| Participants | 106 women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Three patients in the sham group were excluded because they were given metoclopramide in the postoperative period for persistent vomiting (but this data was included for risk of rescue antiemetic given analysis). | |

| Interventions | Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on the P6 acupoint was applied 30–45 min before induction and continued for 6 hours postoperatively. Sham group was treated the same way but with the electrical stimulator turned off. |

|

| Outcomes | Vomiting (0–2h) without antiemetic rescue, risk of rescue antiemetic (metoclopramide). | |

| Notes | Potential bias if outcome assessor removed plastic bag covering the stimulator. Reported vomiting 2–4h, 4–6h, 6–8h intervals. No data on vomiting (0–8h). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | No | “Three patients, originally assigned to the control groups, who received postoperatively metoclopramide because of persistent vomiting were eliminated from further vomiting evaluation and consequently from the study”. Comment: may introduce clinically relevant bias in summary effect measure. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Nausea and side effects were not reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The two groups did not differ in age, body weight, duration of anaesthesia, and duration of surgery (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | “The stimulator, active or inactive, was covered with dark plastic bags, not allowing distinction between active and inactive stimulators”. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | Vomiting was assessed by “an independent observer who was unaware of the patient randomization and of TENS treatment”. |

| Ferrara-Love 1996 | ||

| Methods | Allocation was done by birth date with even numbered months and days assigned to the treatment group, odd months and days assigned to the sham acupressure group, and combinations of even/odd months and days assigned to the no treatment group. Recovery room nurses were blinded to patients with acupressure and sham acupressure wristbands. | |

| Participants | 136 adults undergoing orthopaedic, general, plastic, and ’other’ surgery. Forty-six patients excluded after randomisation for failure to meet inclusion criteria. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: acupressure wristbands placed on P6 acupoint during surgery until hospital discharge. Group 2: sham acupressure wristbands without studs placed on P6 acupoint during surgery until hospital discharge. Group 3: reference group had no acupressure treatment. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea in the operating room after surgery, risk of rescue antiemetic drugs in the operating room if nausea persisted and/or emesis occurred. | |

| Notes | No treatment group excluded from data analysis. No cumulative outcome data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | No | “Randomization was done by birth date with even numbered months and days assigned to the treatment group, odd months and days assigned to the placebo group and combinations of even/odd months and days assigned to the control group”. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for the 90 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Risk of vomiting and side effects were not reported in the results. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “There were no differences between groups in demographic and perioperative variables” as tested using appropriate univariate statistical tests. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | PACU staff were blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting was documented by the PACU staff who were blinded as to treatment and placebo group”. |

| Gan 2004 | ||

| Methods | Randomization by random number generator in a sealed envelope technique. To maintain patient blinding, sham surface electrodes placed on P6 bilaterally but electrical stimulation unit not turned on. Electrical stimulation unit screen was covered with an opaque tape in all groups so that clinicians, research personnel, and patients were unaware if the unit was on or off. Study medication prepared by pharmacists, not involved in study. Postoperative data collected by research nurse not involved in management of patients. | |

| Participants | 77 patients undergoing major breast surgery. Exclusion: pregnancy, using permanent cardiac pacemaker, previous experience of acupuncture therapies, received any antiemetic medication or had nausea, vomiting or retching within 24 hours of surgery. Two patients withdrew from study. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: ondansetron 4 mg IV given at induction of anaesthesia and sham electro-acupoint stimulation at P6 acupoints (30 to 60 min before induction and continued to the end of surgery). Group 2: electro-acupoint stimulation at P6 bilaterally (30 to 60 min before induction and continued to the end of surgery) and saline IV given at induction of anaesthesia. Group 3: sham electro-acupoint stimulation at P6 bilaterally (30 to 60 min before induction and continued to the end of surgery) and saline IV given at induction of anaesthesia. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–2h), vomiting (0–2h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug, adverse effects. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was dexamethasone 8 mg IV when patient’s nausea score > 5 out of 10 for 15 min or longer, 2 emetic episodes within 15 min, or at patient’s request. No redness residue on acupoint site in any groups. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Randomization was achieved using a random number generator..”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “…In a sealed envelope technique”. “Study drugs were prepared by the pharmacists not directly involved in the study..”. Comments: the authors appeared to take steps to minimize inadequate allocation concealment. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons for withdrawals were given. No missing data reported for the 75 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “There was no difference in patient demographics among the groups (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | “All patients were also told that the device produced an electrical current that they may or may not feel. The screen on the unit (measuring 4 × 2 cm) was covered with an opaque tape in all groups so that the clinicians and research personnel were unaware if the unit was on or off ”. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “All patients were also told that the device produced an electrical current that they may or may not feel. The screen on the unit (measuring 4 × 2 cm) was covered with an opaque tape in all groups so that the clinicians and research personnel were unaware if the unit was on or off ”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “Postoperative data were collected by a separate research nurse not involved in the preoperative or intraoperative management of patients”. |

| Gieron 1993 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Outcome assessor knew what treatment group the patient belonged to. | |

| Participants | 90 Women undergoing gynaecological operations (6–8h). | |

| Interventions | Group 1: acupressure was carried out by fastening small metal bullets at the P6 acupoint to each wrist by an elastic bandage on the morning of the operation and left on for 24h. Group 2: sham acupressure carried out by applying elastic bandage to P6 acupoint on the morning of the operation and left on for 24h. Group 3: no treatment. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–6h), vomiting (0–6h), risk of rescue antiemetic (metoclopramide). | |

| Notes | No treatment data were excluded from analysis. Also reported separate incidences of nausea and vomiting (0–1h) and (6–24h). No side effects identified in the trial. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for 90 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes were reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The anthropometric data, the duration of surgery and the amount of postoperative analgesia were comparable between the three groups”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | No | The outcome assessor was not blinded. |

| Habib 2006 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment unclear. For blinding, the transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation was covered with opaque gauze that was taped to the wrist. Outcome assessor blinded. | |

| Participants | 94 Women undergoing Caesarean delivery under spinal anaesthesia. Exclusion: previous experience of acupuncture or acu-stimulation, had experienced vomiting or retching within 24 h before surgery, had taken on antiemetic or a glucocorticoid within 24 h before surgery, or had an implanted pacemaker or defibrillator device. Three patients withdrew from study because of protocol violations. | |

| Interventions | Transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation device on P6 acupoint of the dominant hand 30 to 60 min before surgery. Patients asked to wear wristband for 24 h after surgery. Sham transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation device on dorsum of wrist of the dominant hand 30 to 60 min before surgery. Patients asked to wear wristband for 24 h after surgery. | |

| Outcomes | Postoperative nausea (0–24h), postoperative vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic. | |

| Notes | Intraoperative nausea and vomiting data reported in the paper. Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV if nausea score was 6 or more, or at patient’s request. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficent information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons for withdrawals given. No missing data reported for 91 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Side effects not reported |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The two groups were similar with respect to demographics, parity, history of PONV or motion sickness, smoking status, duration of surgery, blood loss, intraoperative fluids, intraoperative IV fentanyl, intraoperative IV ephedrine, treatment for pruritus, and consumption of oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. “For blinding, the ReliefBand was covered with opaque gauze that was taped to the wrist”. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “A separate researcher who was unaware of the patient’s randomisation collected that data…”. |

| Harmon 1999 | ||

| Methods | Randomization was conducted by computer and the code was sealed (not opaque) until arrival of patient in the operating theatre. Outcome assessor was blinded to treatment groups. | |

| Participants | 104 Women undergoing laparoscopy and dye investigation. Exclusions: obesity, diabetes mellitus, and previous history of PONV. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure on P6 acupoint of right wrist, applied immediately before induction for 20 min, removed before end of surgery. Placebo acupressure on non-acupoint site, applied before induction for 20 min and removed before end of surgery. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drugs. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV and prochlorperazine 12.5 mg IM. No side effects in either group noted. Some patients did not have outcome data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Randomization was conducted by computer..”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | “…And the code was sealed until arrival of the patient in the operating theatre”. Comment: not sure whether envelopes were sequentially numbered and opaque. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | No | In acupressure group (n=52), missing nausea and vomiting data in 8 and 5 patients respectively. In sham group (n=52), missing nausea and vomiting data in 13 and 5 patients respectively. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The groups were comparable in age, weight and duration of surgical procedure (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | “Both patients and nurses were unaware of patient group allocation”. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “Both patients and nurses were unaware of patient group allocation”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “..An anaesthetist blinded to the therapy registered whether nausea, retching or vomiting had occurred”. |

| Harmon 2000 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment was not given. Acupressure wristbands and placebo acupressure wristbands were covered with surgical drapes to prevent anaesthetist from identifying which group the patient was allocated to. Patients might have guessed which group they were in as there was no attempt to conceal the wristband. Authors claimed that the outcome assessor was blinded to treatment group. | |

| Participants | 94 Healthy women (18 to 40 years) undergoing elective Caesarean section. Excluded: previous history of PONV, nausea and vomiting in previous 24 hours, obesity (body mass index > 35), diabetes mellitus, or previous experience of acupuncture or acupressure. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure on P6 acupoint on right wrist, applied 5 min before administration of spinal anaesthesia, removed just before assessment 6 hours after discharge to the ward. Placebo acupressure on non-acupoint site, applied 5 min before administration of spinal anaesthesia, removed just before assessment 6 hours after discharge to the ward. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h). | |

| Notes | Reported separate incidence of intraoperative nausea and vomiting. Rescue antiemetic was ondansetron 4 mg IV during operations, or cyclizine 50 mg IM 8 hourly after operations. Rescue antiemetic use reported as mean dose (no data for risk of rescue cyclizine use). Side effect of acupressure bands was “some localized discomfort in a small number of women”. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Reasons for withdrawals were given. No missing data reported for 94 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Risk of rescue cyclizine not reported separately for nausea and vomiting outcomes. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The groups were comparable with respect to age, weight, height and bupivacaine dose (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “Bands were not visible to the assessing anaesthetist during operations, as patients’ arms were covered with surgical drapes”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “After 6 and 24h, an anaesthetist blinded to the therapy noted whether nausea, retching or vomiting had occurred”. |

| Ho 1989 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. No details about whether the outcome assessor was blinded to treatment groups or not. | |

| Participants | 100 Women undergoing laparoscopy. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: electro-acupuncture applied at P6 acupoint on right wrist for 15 min in the recovery room. Group 2: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at P6 acupoint on right wrist for 15 min in the recovery room. Group 3: antiemetic group was given prochlorperazine 5 mg IV. Group 4: no treatment. |

|

| Outcomes | Vomiting (0–3h), side effects of treatment groups. | |

| Notes | Reference group received no treatment and was not included in data analysis. Groups 1 and 2 were combined for data analysis. Side effect of electro-acupuncture were sleepiness and feeling tired. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data was reported for the 100 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Only vomiting was reported. Authors should have assessed nausea in women and the risk of rescue antiemetic drugs. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “The age, weight, and duration of anaesthesia did not differ significantly among the groups (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Ho 1996 | ||

| Methods | Randomization conducted by computer, with each code sealed in an envelope (not opaque) to be opened before induction of spinal anaesthesia. Outcome assessor was blinded to treatment groups. | |

| Participants | 60 Women receiving epidural morphine for post-Caesarean section pain relief. Excluded: previous carpal tunnel syndrome, or those who had experienced nausea or vomiting within 24 h before Caesarean section. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: acupressure wristbands on P6 acupoint of both wrists before administration of spinal anaesthesia. Worn for 48 hours. Group 2: sham acupressure wristbands on both wrists but plastic button was blunted in order not to exert pressure on P6 acupoint. Worn for 48 hours. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–48h), vomiting (0–48h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug, side effects of acupressure wristbands. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was metoclopramide. No side effects were noted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Randomization was conducted by computer..”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | “…With each code sealed in an envelope to be opened upon the parturient’s arrival in the operating room”. Comment: not sure if envelopes were sequentially numbered and opaque. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | “All parturients completed the trial and tolerated the bands well”. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All expected outcomes reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “There were no statistically significant difference with respect to age, weight, height, duration of operation, intraoperative blood loss, duration of pain relief, total epidural morphine dosage, percentage of parturients requiring additional analgesics and total time spent wearing bands between the two groups”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “An independent anaesthesiologist blinded to the parturient groups followed up all parturients”. |

| Klein 2004 | ||

| Methods | Patients randomized by computer-generated random number tables to either acupressure or sham groups. Both groups had acupressure bands covered by a soft cotton roll to ensure blinding. Anaesthetist caring for the patient was not aware of the group allocation. Outcome assessor blinded to treatment allocation. | |

| Participants | 152 Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft or valvular surgery. Exclusion: past history of hiatus hernia, heartburn, or previous gastric surgery, morbid obesity, taking antiemetic medications, H2 receptor antagonist, or proton pump inhibitors. No details about withdrawals or loss to follow up. | |

| Interventions | Acupressure wristbands on P6 acupoint on both wrists before induction of anaesthesia, removed 24 h after extubation. Sham acupressure wristbands on P6 acupoint of both wrists before induction of anaesthesia, removed 24 h after extubation. Sham group had band without a bead placed on P6 acupoint. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug, risk of adverse effects. | |

| Notes | Rescue antiemetic was dimenhydrinate 50 mg IV for patients who reported moderate or severe nausea, or who experienced retching or vomiting. No significant adverse effects reported in either group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Patients were randomized by computer-generated random number tables to either acupressure or placebo control groups”. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | No missing data reported for the 152 patients analysed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Reported all expected outcomes. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “There were no differences between the 2 groups with regard to demographic data and surgical characteristics (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | “The anaesthesiologist caring for the patient was not aware of group allocation”. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “All patients were assessed for nausea and vomiting by nursing staff in the intensive care unit, who were unaware of treatment allocation”. |

| Lewis 1991 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment was not given. Outcome assessor was blinded. Acupressure wristbands were worn for approximately 4 hours. | |

| Participants | 66 Children undergoing strabismus correction surgery. Excluded: children with anatomical or neurological abnormalities of the upper limbs. Two children lost to follow up. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: acupressure wristbands placed on P6 acupoints 1 hour before surgery and worn until discharge from hospital. Group 2: sham acupressure wristbands without studs placed on P6 acupoints 1 hour before surgery and worn until discharge from hospital. |

|

| Outcomes | Vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug, side effects. | |

| Notes | Both types of wristbands were identical unless turned inside out. Rescue antiemetic was droperidol 0.02 mg/kg IV for vomiting. No side effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Insufficient information. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Yes | Two patients in acupressure group had incomplete data. Comment: unlikely to have a clinically relevant impact on summary estimate. |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Although nausea was an outcome collected in the methods section it was not reported in the results because nausea may be difficult to assess in children. |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | Baseline characteristics were comparable. “There were no significant differences between the two groups in their patient characteristics (Table 1)”. |

| Blinding of patients? All outcomes | Yes | Authors took adequate steps to make interventions appear similar. |

| Blinding of healthcare providers? All outcomes | Yes | The anaesthetic staff were blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessor? All outcomes | Yes | “A second blinded investigator recorded all other perioperative data, including the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in the recovery areas”. |

| Liu 2008 | ||

| Methods | Method of allocation concealment not given. Anaesthetist and the outcome assessor were blinded. | |

| Participants | 96 Patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy who were aged 18 to 60 years. Exclusions: pregnancy, women experiencing menstrual symptoms, patients with permanent cardiac pace-maker, previous experience with acupuncture therapies before surgery, received antiemetics or experienced nausea, vomiting, or retching within 24 h of surgery. No patients withdrew from study. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: transcutaneous electro-acupoint stimulation using a peripheral nerve stimulator at P6 (2–100 Hz, 50 ms, 0.5–4mA) applied 30 to 60 min before induction of anaesthesia, and continued to the end of surgery. Group 2: inactive device with similar electrode for transcutaneous electro-acupoint stimulation using a peripheral nerve stimulator at P6 applied 30 to 60 min before induction of anaesthesia, and continued to the end of surgery. |

|

| Outcomes | Nausea (0–24h), vomiting (0–24h), risk of rescue antiemetic drug (0–24h), adverse effects of transcutaneous electro-acupoint stimulation. | |