Abstract

Background

Geriatric adults represent an increasing proportion of emergency department (ED) users, and can be particularly vulnerable to acute illnesses. Health care providers have recently begun to focus upon the development of quality indicators to define a minimal standard of care.

Objectives

The original objective of this project was to develop additional ED-specific quality indicators for older patients within the domains of medication management, screening and prevention, and functional assessment, but the quantity and quality of evidence was insufficient to justify unequivocal minimal standards of care for these three domains. Accordingly, the authors modified the project objectives to identify key research opportunities within these three domains that can be used to develop quality indicators in the future.

Methods

Each domain was assigned one or two content experts who created potential quality indicators (QI) based on a systematic review of the literature, supplemented by expert opinion. Candidate quality indicators were then reviewed by four groups: the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Geriatric Task Force, the SAEM Geriatric Interest Group, and audiences at the 2008 SAEM Annual Meeting and the 2009 American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting, using anonymous audience response system technology as well as verbal and written feedback.

Results

High-quality evidence based on patient-oriented outcomes was insufficient or non-existent for all three domains. The participatory audiences did not reach a consensus on any of the proposed QIs. Key research questions for medication management (3), screening and prevention (2), and functional assessment (3) are presented based upon proposed QIs that the majority of participants accepted.

Conclusions

In assessing a minimal standard of care by which to systematically derive geriatric QIs for medication management, screening and prevention, and functional assessment, compelling clinical research evidence is lacking. Patient-oriented research questions that are essential to justify and characterize future quality indicators within these domains are described.

INTRODUCTION

The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM), with participation from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), created the SAEM Geriatric Task Force in 2005 largely to improve the care delivered to geriatric emergency department (ED) patients. The task force identified topics in the ED management of older adults (i.e., those aged 65 years and older) that are essential to their health and well-being, and for which there are important gaps in the quality of care that they receive. With the understanding that there are many areas for which quality must be improved, the goal was to select a small number of important areas to initiate the identification of quality indicators (QIs) for the emergency care of older adults.

In various medical settings, patients frequently receive inadequate health care.1 The ED is no exception, and errors of omission and commission have been reported.2,3 Emergency medicine (EM) occurs in a unique milieu of time-pressured diagnostic uncertainty within a frequently crowded space.4,5 Despite a constellation of problems, including nursing shortages, information overload, liability concerns, increasing ambulance diversions, uncompensated care, and bioterrorism preparedness, EM must focus on quality improvement because patients deserve competent care and the public demands it. Within the ED environment, older adults more often fail to receive appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic interventions compared to younger populations.6–10 Aging adults were recognized as a disproportionate challenge to EM physicians two decades ago, but changes within graduate medical education have been slow to evolve.11–13 Because the proportion of patients receiving care in U.S. EDs who are older will continue to increase for decades, age-specific quality improvements specifically designed to mitigate these deficits are essential and long overdue.14–17

The Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) investigators recently developed a comprehensive set of primary care focused quality assessment tools for high-risk community-dwelling adults over age 65 years. They used the RAND appropriateness method to develop evidence-based, patient-centric quality of care indicators using systematic literature reviews and expert group consensus.18 ACOVE investigators reported that vulnerable community-dwelling older adults do not routinely receive acceptable levels of care in inpatient and outpatient settings, even though higher quality care is associated with improved survival.19,20 Investigators have since expanded the list of QIs for primary care to 26 conditions with 392 QIs covering 14 different interventions, ranging from history, physical exam, screening, and diagnostic testing to referrals, surgery, and physician visits.18,21 Terrell et al. used similar methods to develop EM-specific QIs for cognitive assessment, pain management, and transitional care.22 Although the original objective of this project was to develop additional ED-specific QIs for older patients within the domains of medication management, screening and prevention, and functional assessment, the quantity and quality of evidence was insufficient to justify unequivocal minimal standards of care within these domains. We therefore modified the project objectives to identify key research questions within these three domains that are necessary to answer before evidence-based QIs can be offered to the practicing community.

METHODS

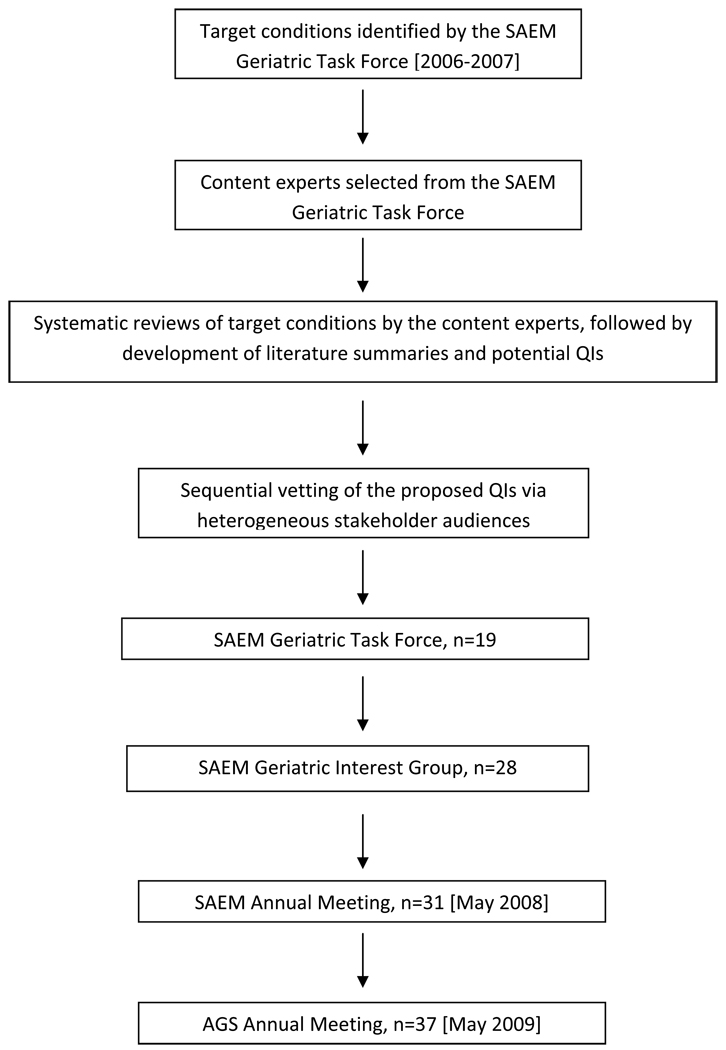

This project occurred over a three-year period from 2006 through 2009 (Figure). The task force first conducted literature reviews and Delphi-type surveys among its members to identify major deficiencies in the emergency care of geriatric adults involving conditions that are important for the seniors’ health and well-being. Six target conditions were identified by this process (described below). The next step was to construct QIs to address these deficiencies, which then were vetted across multiple groups of heterogeneous geriatric health care providers. The initial set of QIs was published for three conditions: cognitive assessment, pain management, and transitional care.22 A similar process (described in detail below) was conducted for the remaining three conditions: medication management, screening and prevention, and functional assessment. However, the quantity and quality of evidence to support proposed QIs for these three conditions was found to be low. Further, feedback from the audiences that vetted the proposed QIs indicated that some of the proposed QIs seemed unreasonable, and that the others were not yet validated to the extent that they could be used in quality-improvement projects. For these reasons, the task force determined that recommending QIs in these three areas was premature. However, both the task force and the vetting audiences believed that work to establish evidence-based QIs was worthwhile, based on clear evidence of inadequate care in these areas. Therefore, the final step was to transform the QIs that the vetting audiences felt were reasonable into research priorities that could provide validated QIs for subsequent quality improvement efforts.

Figure.

Geriatric Emergency Medicine Quality Indicator (QI) Research Question Development

Process for developing possible Quality Indicators (see Figure)

The task force identified content experts for each target condition (medication management, KH and AG; screening and prevention, CRC; and functional assessment, STW and KS). The content experts created potential QIs using IF-THEN statements, following the ACOVE quality indicator approach.18 The “IF” statement determines whether a patient is eligible for the QI, and “THEN” describes the care process that should or should not be performed. A QI is considered to have been satisfied if the medical record indicates that a patient is offered or receives the care required by the QI (e.g., timely administration of aspirin for an acute myocardial infarction). The QI is excluded from application to the patient if the patient has a documented contraindication to the indicator (e.g., allergy to aspirin). The QI is not met if the medical record 1) demonstrates that the patient meets inclusion criteria, AND 2) does not indicate that the patient was offered the care required by the indicator, AND 3) has no documentation that the care item was contraindicated or refused by the patient. The QIs in this project were designed to be used with ED medical records as the data source.

The five content experts conducted systematic reviews for their target conditions. They searched for relevant English language articles in MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and The Cochrane Library using appropriate subject headings and text words for each condition. Search terms are provided in Data Supplement 1. For each search, all titles and abstracts (if available) were reviewed to screen for potentially relevant articles. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were examined for possible inclusion. Content experts examined all references within relevant articles for studies that might meet inclusion criteria. After critically reviewing all applicable articles, each content expert developed a critical summary of the literature and a preliminary list of QIs. For the medication management indicators, the authors also performed a limited analysis of the ED component of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) to identify the medications most commonly prescribed to older patients discharged from the ED (see DS 1 for details).

Four groups sequentially evaluated the proposed QIs: the full SAEM/ACEP Geriatric Task Force (n = 19), the SAEM Geriatric Interest Group (unique n = 28), an audience at the 2008 SAEM annual meeting (n = 31), and audience members at a workshop at the 2009 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) annual scientific meeting (n = 37). The meeting programs described the workshops as interactive. Audience members were informed that they would help contribute to developing the QI agenda. The QIs were modified after each evaluation, based on consideration of each group’s responses. First, the literature summaries and proposed QIs were distributed to the 19 members of the 2007–2008 Task Force. Recipients were instructed to critically review the preliminary QIs and provide feedback to the task force chair (LWG) or the appropriate content expert, but to avoid replying to all of the task force members so that all comments would be independent. All feedback received by the chair was forwarded to the appropriate content experts.

The content experts revised the QIs in response to task force members’ suggestions. In the second stage of development, the revised indicators were distributed to the members of the SAEM Geriatric Interest Group. Again, recipients were asked to reply only to the chair or the content expert. The indicators were revised based on the new comments.

Third, the revised working set of medication management, screening, and functional assessment QIs were presented at an interactive didactic session at the 2008 SAEM annual meeting using individualized electronic response cards for all members of the audience.23 The 31 participants included physicians (89% of group, including 13% residents), nurses (3%), and social workers (3%). The majority of participants practiced in the United States (81%) or Canada (8%). The session’s goal was to draw on the expertise of this group to refine the QIs for use by clinicians, researchers, educators, and administrators. The session began with a background presentation on the nature of QIs. The content experts presented their sets of proposed QIs and the basis for inclusion of each. A discussion with the audience occurred after each presentation followed by anonymous electronic voting for each QI with three options: accept, reject, or modify. The QIs were revised based on these discussions. Further discussion followed the anonymous voting.

The next step was to present the three sets of QIs at a workshop during the 2009 AGS annual meeting. There were 37 consenting participants in the audience, including physicians (80%), nurses (3%), social workers (3%), and non-physician gerontologists (14%). The majority of participants practiced in the United States (76%) or Canada (9%). Similar to the SAEM meeting, each set of QIs was presented separately and feedback from the audience was elicited. The group discussion informed modification of QIs, resulting in the final version presented in this article. The description of the QIs in Data Supplement 2 represents the original wording as presented to the various audiences, whereas the QIs presented in the body of the manuscript represent the final wording.

Audience members at each meeting were asked to use their Turning Point (Turning Technologies LLC, Youngstown, OH) handheld devices to approve, reject, or modify the proposed QI. The voting results (DS 2) were presented on the screen and further discussion followed.

The evidence for improved patient-centric outcomes was non-existent or of low quality for each domain. In addition, the diverse participatory audiences failed to achieve a consensus for most of these proposed measures. Therefore, rather than present QIs without sufficient supporting evidence, we decided to use results from this multi-stage process to identify key research questions that could be used to construct validated QIs for use in subsequent quality improvement initiatives.

RESULTS

In the sections that follow, the key research questions for the three domains are reported separately. For each condition, we provide a brief description of the pertinent literature, the proposed research questions that will inform the development of future QIs, and the rationale for each research recommendation.

Medication Management

Adverse drug events are a common cause of ED visits and hospitalizations.24–26 As older patients take more medications, they are at increased risk to suffer from these events.27 While some adverse events cannot be prevented, many can be avoided.28 As over 50% of patients over the age of 65 years who are seen in an ED receive a prescription for a new medication,27 decreasing adverse drug events due to prescriptions provided in the ED is a reasonable objective that is likely to improve patient outcomes.

We sought to suggest QIs that would be relevant to EM by targeting medications that are frequently prescribed to patients discharged from the ED, and that are common causes of adverse drug events. We selected four medications that were commonly prescribed (based on NHAMCS data), and that are frequent cases of adverse drug events (based on the literature review).24,25,29 For these medications, we identified an intervention (such as monitoring, checking for interactions, or adding a protective agent) that would be expected to decrease the rate of adverse events from that medication. One of these interventions (early follow-up renal function monitoring following prescription of loop diuretics) was not accepted during the SAEM presentation, so it is not included in the research questions listed below.

Key Research Questions for Medication Management

Research Question # 1: Can efficient ED systems be developed to identify potential interactions with warfarin when new medications are prescribed?

Rationale: Warfarin is one of the most common causes of adverse drug events.25,26 At least 13 of the top 20 medications that are most commonly prescribed to older patients discharged from the ED have an interaction that potentially inhibits or potentiates the anticoagulant effects of warfarin30 (details available from the authors on request).

Research Question # 2: Can systems be developed to enhance appropriate benzodiazepine prescribing from the ED and minimize adverse effects like falls?

Rationale: Lorazepam is the 28th most commonly prescribed medication to patients older than age 65 years who are discharged from the ED. Benzodiazepines are a common cause of adverse drug events,25,26 and several studies have reported an increased risk of falling in older patients who are prescribed short- and long-acting benzodiazepines.31–34 Furthermore, benzodiazepines are frequently prescribed for conditions where there are little data for efficacy (such as vertigo, muscle spasm, and acute anxiety), or for conditions where the need for emergent treatment is questionable (insomnia).35–38 The one condition where benzodiazepines are clearly the drug of choice is alcohol withdrawal, and it is likely that older patients with alcohol withdrawal will require admission to the hospital. As the use of benzodiazepines is questionable for most other conditions, a careful assessment of risks and benefits will help assure that the medications are used appropriately.

Research Question # 3: Do gastroprotective agents reduce short-term gastrointestinal (GI) complications when prescribed concurrently with NSAIDS in the ED?

Rationale : Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are the fourth most common category of medications prescribed to patients older than 65 years who are discharged from the ED, and account for approximately 12% of adverse drug event admissions.25,26 The relative risk of GI complications increases dramatically in patients older than 70 years.39 Several studies have shown that gastroprotective agents (proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol) decrease the risk of GI bleeding, and a Cochrane review recommends the use of these gastroprotective agents with NSAIDS for high risk patients.40,41

Screening and Prevention

Compared with younger populations, older adults use emergency services more frequently with greater illness-related urgency and ED recidivism.42 Age-associated pathology such as cognitive dysfunction, fall risk, and frailty is prevalent and often unrecognized.33,43,44 ED-based case-finding has demonstrated no effect on overall service use, but does reduce nursing home admissions while improving patient satisfaction and increasing the recognition of occult cognitive impairment.45–47 Several tools have been validated to identify a subset of older adults at risk for short-term functional decline including the Triage Risk Screening Tool (TRST), Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR), and the Brief Risk Identification for Geriatric Health Tool (BRIGHT).47–49

The SAEM Preventive Services working group had previously identified falls prevention and pneumococcal vaccination for individuals over age 65 years as geriatric-specific interventions of potential value to older ED patients.50 Because 27% of geriatric adults fall at least once every year, emergency physicians will be evaluating many fall-related injuries.33 However, in the United States, fall patients frequently fail to prompt ED-based risk assessment or secondary prevention.51 In a similar fashion pneumococcal vaccination is a simple intervention, but non-immunized patients rarely receive the vaccine while in the ED.52,53 Furthermore, discharged patients do not routinely obtain outpatient vaccinations, nor do admitted patients.54,55

Key Research Questions for Screening and Prevention

Research Question #1: Will etiology-specific ED interventions following evaluation of a standing-level fall reduce subsequent fall rates, injurious falls, fear of falling, or functional decline?

Rationale: Falls are the leading cause of traumatic mortality in older adults, costing the United States alone $19 billion annually.56,57 The AGS/British Geriatrics Society “Prevention of Falls in Older Persons” guidelines provide eleven summary recommendations for screening and assessment, including routine questions about the presence and frequency of falls, ambulation difficulties, and a multifactorial fall risk assessment for those who perform poorly on standardized gait testing.58 Although these guidelines represent the initial stages of enhancing fall-prevention efforts by decreasing variability, they are not well-suited for emergency care for several reasons. First, ED-specific fall risk stratification instruments have yet to be validated.59,60 Many of the individual risk factors and functional assessment screens that are associated with increased fall risk in other settings are either impractical or inaccurate for ED populations to identify older adults most likely to fall.60 Second, the guidelines suggest that “the health professional or team conducting the fall risk assessment should directly implement the intervention, or should assure that the interventions are carried out by other qualified health care professionals.” This is impractical in the crowded ED without round-the-clock access to traditional falls prevention support services. More importantly, very little high-quality evidence exists to demonstrate effectiveness for ED-initiated falls interventions.61 In addition, complicated interventions that span multiple specialties and entail home- or lifestyle-based modifications are difficult to initiate and sustain from the ED. Therefore, emergency clinicians cannot be confident that even if high-risk fallers were identified, fall-risk programs can be implemented and falls can be reduced.

The effect of ED-based falls prevention initiatives will need to assess a variety of outcomes at the patient, family, and community levels in evaluating cost-benefit trade-offs. The diminished quality of life resulting from fear of falling is less apparent than the medical expense and physical deterioration associated with injurious falls, but are also important to study.62 Some ED-based multidisciplinary secondary prevention interventions have reduced fall rates, but results were inconsistent and fall-related injuries were not reduced.63–66

Research Question #2: Can ED-based influenza or pneumococcal immunization programs safely, efficiently, and cost-effectively vaccinate at-risk geriatric adults without impeding patient throughput?

Rationale: One-half of pneumonia patients discharged from the hospital are re-hospitalized or die from a vaccine-preventable infection within five years.67 Nonetheless, the majority of geriatric ED patients are not immunized against seasonal influenza.53,68 In older adults, widespread influenza vaccination practices can reduce all-cause mortality by 40% to 50% annually, with the most marked impact on the 65 to 69 years age-group.69,70 The American College of Physicians Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that all persons over age 65 years should receive an annual influenza vaccination.71 Similarly, vaccination against pneumococcal bacteremia in older adults is cost-effective,72,73 but most older patients in the ED remain unvaccinated for pneumococcus.68,74–76 However, evidence suggests that ED-based pneumococcal vaccinations are feasible, desirable, and acceptable for both health care providers and patients.54,68,73,75–78

The reasons why older adults are not routinely vaccinated against pneumococcal or influenza infections in the ED are likely related to perceptions of effectiveness, risk aversion, and the limits of emergency care.53 Whereas tetanus vaccination effectiveness approaches 100%, lower-quality evidence suggests that pneumococcal vaccination does not prevent pneumonia, but may reduce illness severity and bacteremia.67,79–81 On the other hand, influenza vaccination is 70% to 90% effective in preventing influenza-like illness related death.82 Another barrier to ED-based vaccinations for pneumococcus is that it needs be administered only once, and emergency staff may be wary about the risks and costs of duplicate administration.53 This impediment would not apply to influenza, though, and would not explain why most EDs do not screen for immunization status. As regards to the scope of emergency practice in comparing exemplary tetanus vaccination rates with less stellar influenza and pneumococcus rates, clinicians probably view tetanus boosters for high-risk wounds as secondary prevention, whereas influenza or pneumococcal vaccines are primary prevention and therefore beyond the role of the ED.53

Key Research Questions for Functional Assessment

Functional assessment of older adults has been recognized as an important aspect of the Geriatric Emergency Care Model described by the SAEM Geriatric Emergency Medicine Task Force in the early 1990s.83 Those authors recommended assessment of activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, and direct evaluation of function using performance tests.83–85 The AGS’s research agenda setting process recommended development and testing of feasible and valid methods of functional assessment in older ED patients, followed by clinical trials to determine whether detection and management of the functional decline improves patients’ outcomes.86–88

General themes identified from review of these articles, book chapters, and expert opinion included the following: functional decline may be the only presenting symptom for numerous serious diseases;89–92 older patients with subacute medical conditions often present when their medical symptoms affect their function;90 injuries commonly result in functional decline;93–97 emergency physicians often do not address function in their evaluation of older ED patients;89,95,98 and the minimum functional abilities needed for discharge are the ability to transfer and ambulate, unless 24 hour care is available.84,85 For these reasons, we consider functional assessment a necessary portion of the history, examination, and disposition of older patients with acute illness and injury, rather than a case-finding or screening process.

Research Question #1: Can key steps in the ED evaluation of older adults presenting with functional decline be delineated to efficiently identify serious medical conditions that alter acute management decisions?

Rationale: Rutschmann and colleagues found that older ED patients with functional decline and no specific medical complaint (referred to as presenting for “home care impossible”) had an acute medical problem in 51% of cases. All of those with acute medical problems were not triaged to a level commensurate with their illness severity, often due to poor recognition of neurological symptoms and atypical clinical presentations.89

Research Question #2: To develop and validate algorithms to optimize functional assessment of older adults presenting with subacute illnesses not otherwise requiring hospitalization or management changes, including the setting and personnel to conduct such screening

Rationale: Wilber and colleagues found that older patients with subacute medical symptoms have poor baseline functional status (only 22% were completely independent), commonly have functional decline as a result of their illness (74%), and this functional decline often contributes to their reason for the ED visit (79%).90

Research Question #3: Can generalizable ED care models to ensure reliable and sustainable assessment of minimal functional status capabilities, such as the capability to transfer and ambulate prior to discharge home, be developed?

Rationale: Functional decline is common in older ED patients with acute injuries, occurring in 23% to 51%.93,95,99 These studies show that the rate of functional decline is highest in the immediate post-injury period.93,95,99 The “Get Up and Go” test, whereby the clinician observes a patient arising from a chair, taking several steps, and sitting down, is recommended and easily performed in the ED.84 The ability to transfer and ambulate is crucial for the performance of other critical activities of daily living, including eating and drinking, and toileting.

DISCUSSION

Emergency providers have an obligation to provide the very best care that they can and to remedy care deficiencies whenever possible. Older patients and other vulnerable populations present issues that pose additional challenges to EM professionals delivering care. Additionally, health care quality has become an overarching focus for government, third party payers, and regulatory agencies. However, the ED is a high stress, high acuity, decision-dense environment with finite resources, in conjunction with limited ability to control patient volume. Further, high variability in the quality of care is the norm in today’s medical environment, and EM is no exception.100–102 Improving quality in such an environment is challenging, and focusing energy and resources on high-yield quality improvement efforts is essential. QIs offer one approach to improve the average quality of care, but QIs must be based on the highest quality evidence, and engender broad-based multidisciplinary support.103,104 The QIs proposed by Terrell et al.22 had, for the most part, reasonable evidence backing them and reasonable agreement at the end of the process. The QIs in this article did not achieve this level of agreement, and we identified the research questions that developed from the process. While the majority of EM quality measures use time-based metrics, the indicators described by both Terrell et al. and our group focus on processes rather than specific structures or outcomes.105

Some of the proposed QIs were rejected by our expert audiences (summarized in DS 2). These audiences represented a broad spectrum of physician and non-physician health care providers in emergency and geriatric settings across academic and community-based settings. Rejected QIs included assessment of prognostic risk using validated tools such as ISAR or TRST,47–49,106,107 comprehensive geriatric assessment in the ED,108 and depression screening.109–112 The various audiences also rejected the concept of EDs that only care for geriatric adults modeled after the pediatric ED.14

If subsequent trials demonstrate efficacy, then future studies will also need to ascertain if these measures are cost-effective and what unintended consequences result from their implementation.113,114 We expect that research on our identified priorities will likely identify further refinements to these and future QIs to enhance their external validity and universal feasibility.113,115,116 For example, no single practitioner could or should be expected to accomplish all of these quality measures during a typical ED encounter. Atypical approaches such as non-physician, non-nurse personnel (volunteers, pre-medical students) trained to administer simple screening tools can be used to perform some of these processes during prolonged ED evaluations.117

LIMITATIONS

The initial set of indicators was developed by emergency physicians with interest and expertise in these domains. Potential biases in developing these research priorities were minimized by using the broad opinion base of the SAEM Geriatric Task Force and Interest Group, SAEM annual meeting attendees, and AGS annual meeting attendees. Nonetheless, our consensus process may have underrepresented practicing community physicians. An additional limitation of our process was that we excluded potential QIs based upon consensus voting without ascertaining specific reasons why certain proposals were rejected. Despite our rigorous methods and divergent audiences, there is a lack of high-quality research to support the originally proposed QIs. Future research will enhance the applicability of QIs for these conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

Three domains for potential quality indicators in the emergency medical care of geriatric adults were evaluated by diverse audiences in a systematic fashion. Participants concluded that these three domains had insufficient high-quality evidence to support quality indicators. High-priority research questions that require an analysis of patient-oriented outcomes are described to shape and prioritize future research as minimal standards of care are shaped for geriatric ED quality indicators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The SAEM Geriatric Task Force included experts in geriatric emergency care from either or both the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine and the American College of Emergency Physicians. Task Force Members included Jeanne M. Basior, MD, University at Buffalo, KaleidaHealth Buffalo General Hospital; Christopher R. Carpenter, MD, MS, Washington University; Michael Cassara, DO, North Shore University Hospital; Jeffrey Caterino, MD, Ohio State University; Kathleen J. Clem, MD, Loma Linda University; James A. Espinosa, MD, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey; Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; Lowell W. Gerson, PhD (Chair), Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Summa Health System; Adit A. Ginde, MD, MPH, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine; Theresa M. Gunnarson, MD, Regions Hospital; Kennon Heard, MD, University of Colorado School of Medicine; Teresita M. Hogan, MD, Resurrection Medical Center; Fredric M. Hustey, MD, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine; Jason A. Hughes, MD, University of Iowa; Ula Hwang, MD, MPH, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Sean P. Kelly, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; C. Eve D. Losman, MD, University of Michigan; Heather M. Prendergast, MD, University of Illinois at Chicago; Arthur B. Sanders, MD, University of Arizona; Manish N. Shah, MD, MPH, University of Rochester; Kirk A. Stiffler, MD, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Summa Health System; Jeffrey Tabas, MD, San Francisco General Hospital; Kevin M. Terrell, DO, MS, Indiana University; Scott Wilber, MD, MPH, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Summa Health System; and Robert Woolard, MD, Texas Tech University HSC SOM, El Paso. Seth Landefeld, MD, University of California, San Francisco, and Douglas K. Miller, MD, Indiana University were American Geriatric Society liaisons with the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

This project was funded by an award from the American Geriatrics Society as part of the Geriatrics for Specialists Initiative, which is supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation.

Drs. Carpenter, Ginde, Heard, and Wilber were supported by Dennis W. Jahnigen Career Development Awards, which are funded by the American Geriatrics Society, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and Atlantic Philanthropies.

Dr. Carpenter was supported by the Washington University Goldfarb Patient Safety award.

Dr. Heard was supported by Award Number K08DA020573 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting societies and foundations or the funding agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fordyce J, Blank FSJ, Pekow P, et al. Errors in a busy emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(3):324–333. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(03)00398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosby KS, Croskerry P. The Nature of Emergency Medicine. In: Croskerry P, Cosby KS, Schenkel SM, et al., editors. Patient Safety in Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croskerry P, Sinclair D. Emergency medicine: a practice prone to error? Can J Emerg Med. 2001;3(4):271–276. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Pracucci G, et al. Stroke in the very old. Clinical presentation and determination of 3-month functional outcome: a European perspective. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2313–2319. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohrenwend PB, Fiesseler FW, Cochrane DG, Allegra JR. Very young and elderly patients are less likely to receive narcotic prescriptions for clavicle fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(6):651–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giugliano RP, Camargo CA, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Elderly patients receive less aggressive medical and invasive management of unstable angina. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(10):1113–1120. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Chen J, Marciniak TA. Early β-blocker therapy for acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(9):648–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-9-199911020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathore SS, Mehta RH, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Effects of age on the quality of care provided to older patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2003;114:307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNamara RM, Rousseau E, Sanders AB. Geriatric Emergency Medicine: A Survey of Practicing Emergency Physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(7):796–801. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumacher JG, Deimling GT, Meldon SW, Woolard B. Older adults in the emergency department: predicting physicians' burden levels. J Emerg Med. 2006;30(4):455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogan TM, Losman ED, Carpenter CR, et al. Development of geriatric competencies for emergency medicine residents using an expert consensus process. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang U, Morrison RS. The geriatric emergency department. J Am Geratr Soc. 2007;55(11):1873–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts DC, McKay MP, Shaffer A. Increasing rates of emergency department visits for elderly patients in the United States, 1993 to 2003. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(6):769–774. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolinsky FD, Liu L, Miller TR, et al. Emergency department utilization patterns among older adults. J Geront Med Sci. 2008;63(2):204–209. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, Gold G. Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekelle PG, MacLean CH, Morton SC, Wenger NS. Assessing care of vulnerable elders: methods for developing quality indicators. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8):647–652. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_2-200110161-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(9):740–747. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higashi T, Shekelle PG, Adams JL, et al. Quality of care is associated with survival in vulnerable older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(4):274–281. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-4-200508160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle PG. Introduction to assessing care of vulnerable elders-- 3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(52):S247–S252. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terrell KM, Hustey FM, Hwang U, et al. Quality indicators for geriatric emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(5):441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turning Point Technologies. Audience Response Systems. Youngstown, OH: 2011. [Accessed Apr 4]. Available at: http://www.turningtechnologies.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, et al. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):755–765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard RL, Avery AJ, Slavenburg S, et al. Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(2):136–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804–807. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1107–1116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y, et al. Is inappropriate medication use a major cause of adverse drug reactions in the elderly? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(2):177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson Micromedex. [Accessed Apr 4, 2011];DRUG-REAX System (electronic version) Available at: http://www.thomsonhc.com.

- 31.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly person living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luukinen H, Koski K, Laippala P, Kivela SL. Predictors for recurrent falls among the home-dwelling elderly. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1995;13(4):294–299. doi: 10.3109/02813439508996778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein LZ. Will my patient fall? JAMA. 2007;297(1):77–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Souchet E, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Drug related falls: a study in the French pharmacovigilance database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(1):11–16. doi: 10.1002/pds.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shorr RI, Robin DW. Rational use of benzodiazepines in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1994;4(1):9–20. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199404010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meehan KM, Wang H, David SR, et al. Comparison of rapidly acting intramuscular olanzapine, lorazepam, and placebo: a double-blind, randomized study in acutely agitated patients with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(4):494–504. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martel M, Sterzinger A, Miner J, et al. Management of acute undifferentiated agitation in the emergency department: a randomized double-blind trial of droperidol, ziprasidone, and midazolam. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1167–1172. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM. Muscle relaxants for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004252. CD004252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2093–2099. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leontiadis GI, Sreedharan A, Dorward S, et al. Systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(51):iii–vi. 1–164. doi: 10.3310/hta11510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rostom A, Dube C, Wells GA, et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002296. CD002296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):238–247. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):248–253. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hastings SN, Purser JL, Johnson KS, Sloane RJ, Whitson HE. Frailty predicts some but not all adverse outcomes in older adults discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1651–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mion LC, Palmer RM, Meldon SW, et al. Case finding and referral model for emergency department elders: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(1):57–68. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerson LW, Counsell SR, Fontanarosa PB, Smucker WS. Case finding for cognitive impairment in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(4):813–817. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyd M, Koziol-McLain J, Yates K, et al. Emergency department case-finding for high-risk older adults: the Brief Risk Identification for Geriatric Health Tool (BRIGHT) Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:598–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meldon SW, Mion LC, Palmer RM, et al. A brief risk-stratification tool to predict repeat emergency department visits and hospitalizations in older patients discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Trepanier S, Verdon J, Ardman O. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(10):1229–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irvin CB, Wyer PC, Gerson LW. Preventive care in the emergency department, part II: clinical preventive services-an emergency medicine evidence based review. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1042–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donaldson MG, Khan KM, Davis JC, et al. Emergency department fall-related presentations do not trigger fall risk assessment: a gap in care of high-risk outpatient fallers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(3):311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudis MI, Stone SC, Goad JA, Lee VW, Chitchyan A, Newton KI. Pneumococcal vaccination in the emergency department: an assessment of need. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pallin DJ, Muennig PA, Emond JA, Kim S, Camargo CA., Jr Vaccination practices in U.S. emergency departments, 1992–2000. Vaccine. 2005;23:1048–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manthey DE, Stopyra J, Askew K. Referral of emergency department patients for pneumococcal vaccination. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bratzler DW, Houck PM, Jiang H, et al. Failure to vaccinate Medicare inpatients: a missed opportunity. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2349–2356. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spaite DW, Criss EA, Valenzuela TD, Meislin HW, Ross J. Geriatric injury: an analysis of prehospital demographics, mechanisms, and patterns. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(12):1418–1421. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev. 2006;12:290–295. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society. [Accessed Apr 4, 2011];Prevention of falls in older persons. Available at: http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/health_care_pros/Falls.Summary.Guide.pdf.

- 59.Carpenter CR. Evidence based emergency medicine/rational clinical examination Abstract: Will my patient fall? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(3):398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carpenter CR, Scheatzle MD, D'Antonio JA, Ricci PT, Coben JH. Identification of fall risk factors in older adult emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carpenter CR. Preventing falls in community-dwelling older adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(3):296–298. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carpenter CR, Shah MN, Hustey FM, et al. High yield research opportunities in geriatric emergency medicine research: prehospital care, delirium, adverse drug events, and falls. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr040. in publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):93–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gates S, Lamb SE, Fisher JD, Carter YH, Lamb SE. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brit Med J. 2008;336:130–133. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hendriks MRC, Bleijlevens MHC, van Haastregt JCM, et al. Lack of effectiveness of multidisciplinary fall-prevention program in elderly people at risk: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geratr Soc. 2008;56(8):1390–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. CD007146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnstone J, Eurich DT, Minhas JK, Marrie TJ, Majumdar SR. Impact of the pneumococcal vaccine on long-term morbidity and mortality of adults at high risk for pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(1):15–22. doi: 10.1086/653114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodriguez RM, Baraff LJ. Emergency department immunization of the elderly with pneumococcal and influenza vaccines. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(11):1729–1732. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ortqvist A, Granath F, Askling J, Hedlund J. Influenza vaccination and mortality: prospective cohort study of the elderly in a large geographical area. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(3):414–422. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00135306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jansen AG, Sanders EA, Nichol KL, van Loon AM, Hoes AW, Hak E. Decline in influenza-associated mortality among Dutch elderly following the introduction of a nationwide vaccination program. Vaccine. 2008;26(44):5567–5574. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Friedman C. Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):36–39. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sisk JE, Moskowitz AJ, Whang W, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against pneumoccoccal bacteremia among elderly people. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1333–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stack SJ, Martin DR, Plouffe JF. An emergency department-based pneumococcal vaccination program could save money and lives. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(3):299–303. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Polis MA, Smith JP, Sainer D, Brenneman MN, Kaslow RA. Prospects for an emergency department-based adult immunization program. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(11):1999–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Polis MA, Davey VJ, Collins ED, Smith JP, Rosenthal RE, Kaslow RA. The emergency department as part of a successful strategy for increasing adult immunization. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(10):1016–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80437-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wrenn K, Zeldin M, Miller O. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in the emergency department: is it feasible? J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(8):425–429. doi: 10.1007/BF02599056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodriguez RM, Kreider WJ, Baraff LJ. Need and desire for preventive care measures in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(5):615–620. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Slobodkin D, Kitlas JL, Zielske PG. A test of the feasibility of pneumococcal vaccination in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:724–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jackson LA, Neuzil KM, Yu O, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(18):1747–1755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vila-Corcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Llor C, Hospital I, Rodriguez T, Gomez A. Protective effect of pneumococcal vaccine against death by pneumonia in elderly subjects. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(6):1086–1091. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00030205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moberley S, Holden J, Tatham DP, et al. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000422.pub2. CD000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Al-Ansary LA, et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub4. CD001269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sanders AB, Witzke DB, Jones JS, et al. Principles of care and application of the geriatric emergency care model. In: Sanders AB, editor. Emergency Care of the Elder Person. St. Louis, MO: Beverly-Cracom Publications; 1996. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bernstein E. Functional assessment, mental status and case finding. In: Sanders AB, editor. Emergency Care of the Elder Person. St. Louis, MO: Beverly-Cracom Publications; 1996. pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lachs MS. Functional decline. In: Sanders AB, editor. Emergency Care of the Elder Person. St. Louis, MO: Beverly-Cracom Publications; 1996. pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wilber ST, Gerson LW. A research agenda for geriatric emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:251–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wilber ST. Geriatric emergency medicine. In: Solomon DH, LoCicero J, Rosenthal RA, editors. New Frontiers in Geriatrics Research. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2004. pp. 53–83. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carpenter CR, Gerson L. Geriatric emergency medicine. In: LoCicero J, Rosenthal RA, Katic M, et al., editors. A Supplment to New Frontiers in Geriatrics Research: An Agenda for Surgical and Related Medical Specialties. 2nd ed. New York: The American Geriatrics Society; 2008. pp. 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rutschmann OT, Chevalley T, Zumwald C, Luthy C, Vermeulen B, Sarasin FP. Pitfalls in the emergency department triage of frail elderly patients without specific complaints. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:145–150. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.10888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilber ST, Blanda MP, Gerson LW. Does functional decline prompt emergency department visits and admission in older patients? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:680–682. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nemac M, Koller MT, Nickel CH, et al. Patients presenting to the emergency department with non-specific complaints: the Basel Non-specific Complaints (BANC) study. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:284–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.LaMantia MA, Platts-Mills TF, Biese K, et al. Predicting hospital admission and returns to the emergency department for elderly patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:252–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Russell MA, Hill KD, Blackberry I, Day LL, Dharmage SC. Falls risk and functional decline in older fallers discharged directly from emergency departments. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(10):1090–1095. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grossman MD, Scaff DW, Miller D, Reed J, 3rd, Hoey B, Anderson HL., 3rd Functional outcomes in octogenarian trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55(1):26–32. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000072109.52351.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hendriksen H, Harrison RA. Occupational therapy in accident and emergency departments: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(6):727–732. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ferrera PC, Bartfield JM, D'Andrea CC. Geriatric trauma: outcomes of elderly patients discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(7):629–632. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shapiro MJ, Partridge RA, Jenouri I, Micalone M, Gifford D. Functional decline in independent elders after minor traumatic injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:78–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rodriguez-Molinero A, López-Diéguez M, Tabuenca AI, de la Cruz JJ, Banegas JR. Functional assessment of older patients in the emergency department: comparison between standard instruments, medical records and physicians' perceptions. BMC Geriatrics. 2006;6:e13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gerson LW, Blanda MP, Dhingra P, Davis JM, Diaz SR. Do elder emergency department patients and their informants agree about the elder's functioning? Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:721–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289(15):1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Welch WP, Miller ME, Welch HG, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Geographic variation in expenditures for physicians' services in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(9):648–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303043280906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baker LC, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Variations in hospital resource use for Medicare and privately insured populations in California. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):w123–w134. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wennberg JE. Practice variations and health care reform: connecting the dots. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 Suppl Web Exclusives doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.140. VAR140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Welch S, Jensen K. The concept of reliability in emergency medicine. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(1):50–58. doi: 10.1177/1062860606296385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Adams JG, Biros MH. The elusive nature of quality. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1067–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rowland K, Maitra AK, Richardson DA, et al. The discharge of elderly patients from an accident and emergency department: functional changes and risk of readmission. Age Ageing. 1990;19(6):415–418. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.6.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Runciman P, Currie CT, Nicol M, Green L, McKay V. Discharge of elderly people from an accident and emergency department: evaluation of health visitor follow-up. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24(4):711–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department--The DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1417–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Meldon SW, Emerman CL, Schubert DS, Moffa DA, Etheart RG. Depression in geriatric ED patients: prevalence and recognition. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Meldon SW, Emerman CL, Schubert DS. Recognition of depression in geriatric ED patients by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(4):442–447. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fabacher DA, Raccio-Robak N, McErlean MA, Milano PM, Verdile VP. Validation of a brief screening tool to detect depression in elderly ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(2):99–102. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.30103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hustey FM. The use of a brief depression screen in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:905–908. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE: going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7652):1049–1051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Guyatt GH, Meade MO, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Practitioners of evidence based care. Not all clinicians need to appraise evidence from scratch but all need some skills. BMJ. 2000;320(7240):954–955. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: what is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995–998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Stark S, et al. Geriatric syndrome screening in emergency medicine: a geriatric technician acceptability analysis [Abstract] Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):S82. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.