Abstract

The strain theory of suicide postulates that suicide is usually preceded by psychological strains. A strain can be a consequence of any of four conflicts: differential values, aspiration and reality, relative deprivation, and lack of coping skills for a crisis. This study, with a blend of psychiatric and social predictors of suicide, identified correlates of suicide that are relevant to Chinese culture and tested the strain theory of suicide with Chinese data. We sampled 392 suicides and 416 living controls (both aged 15–34 years) from 16 rural counties in China in 2008 and interviewed two informants for each suicide and each control. We found that marriage and religion/religiosity did not distinguish the suicides from the living controls among Chinese rural young women. Religion/religiosity tended to be stronger for suicides than for controls. Psychological strains in the forms of relative deprivation, unrealized aspiration, and lack of coping skills were significantly associated with suicide, even after accounting for the role of mental illness. The strain theory of suicide forms a challenge to the psychiatric model popular in the West, at least in explaining the Chinese suicide.

Keywords: China, Psychological Autopsy, Psychological Strains, Suicide, Culture, Mental Disorder, youth, gender

Suicide is a world-wide public health problem and a leading cause of death in the world, claiming approximately 30,000 lives in the United States each year (NCIPC, 2000) and almost 1 million annually world-wide (WHO, 1999). In China, although in a process of declination (Wang et al., 2008), suicide was the fifth leading cause of death of all ages with a mean annual rate of 23/100,000, or a total of 287,000 suicide deaths per year (3.6% of all deaths), and among young adults 15–34 years of age, suicide was the leading cause of death, accounting for 19% of all deaths in this age group (Phillips, Li, & Zhang, 2002).

Although much has been learned about risk factors contributing to suicide, a fundamental understanding of the suicide process remains unknown, and prevention efforts have been less than fully successful (IOM, 2002). Most previous studies of suicide have been restricted to one domain of possible risk factors, and comprehensive studies on both social and personal (psychological and psychiatric) risk factors are rare. Most of those studies are generally from medical perspectives and are exploratory in nature and therefore lack theoretical generalization. Mann and colleagues (1999) developed and tested a stress-diathesis theory of suicide, but this is only a clinical model based on and for psychiatric patients. Heeringen's (2003) psychobiological model of suicidal behavior, which focuses on the process of the state-trait interaction, seems more generalizable but, again, is neurobiological in nature. Through overcoming such deficiencies, this paper attempts to conceptualize a basic paradigm that incorporates the available theories, hypotheses, and findings explaining suicide in the world today.

In the United States, the factors most consistently associated with suicide, affecting over 90% of all people who die by suicide, are mental illness, substance use disorders (SUD) and alcohol use disorders (AUD). However, the fact that only a small proportion of persons with these disorders actually die by suicide and only approximately half of the Chinese suicides have been diagnosed with any mental problems (Phillips et al., 2002) raises important questions that challenge the psychiatric model of suicide (NIMH, 2003). On the other hand, sociological studies of suicide tend to overestimate the importance of social variables by failing to measure psychiatric disorders with such a rigorous instrument as the SCID (the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1988).

Durkheim's (1951) classical theory of social integration and regulation explaining egoistic, altruistic, anomic, and fatalistic suicide is in theoretical and practical conflict with the psychopathological theories prevalent in today's world (Durkheim, 1951; Heeringen, 2003; Mann, Waternaux, Haas, & Malone, 1999). Suicide rates and patterns vary greatly among different geographic areas and different racial and ethnic groups around the world, and the radical differences in demography of suicide reflect cultural influences. Society and culture play enormous roles in dictating how people respond to and view mental health and suicide, and cultural variables have a far-ranging impact on suicide. Therefore, suicide prevention requires an understanding of how suicide varies with social and cultural forces and how it relates to individual, group and contextual experiences (IOM, 2002).

Theoretical Background

Strain theory of deviance has been present in sociological considerations of crimes for over a century, from Emile Durkheim to Robert Merton and Robert Agnew. The basis for strain theory is Durkheim's theory of anomie (Agnew, 1992). Based on this notion, Robert Merton developed his anomie theory of deviance. According to Merton, society pressures individuals to commit deviant behaviors by creating strain in the life of the individuals. For Merton, strain occurs when one is expected to be as successful as all others but legitimate means are not as available (Merton, 1957). With this encouragement of high aspirations and denial of success opportunities, a society, in effect, pressures people to commit deviance. As a matter of fact, in Merton's original formulation, strain is in the social structure, not within the individual. However, previous strain theories of deviance have failed to directly address suicide as a target for explanation.

Agnew's General Strain Theory (GST) of deviance is based on the conceptualization that “when people are treated badly they may get upset and engage in crime” (Agnew, 2000). There are three major types of strain postulated by Agnew (1992): (1) The blockage of personal goals (actual or anticipated failure to achieve positively valued goals); (2) the removal of positive (valued) stimuli; and (3) the presentation of negative (noxious) stimuli. An example of the personal goal blockage is the gap. Examples of the second strain include the loss of a boyfriend/girlfriend, and the death or serious illness of a family member or close friend. The third type of strain can be exemplified by unpleasant experiences such as child abuse and neglect, and criminal victimization. These strains are argued by Agnew to cause depression, anger, and frustration, which in turn lead to deviant actions such as theft, aggression, and drug use (Agnew, 1992; Jang & Johnson, 2003).

However, as in Merton's anomie theory, suicide is not included in Agnew's theorem, albeit frustration or anger can be inner directed. One previous study has tried to apply Agnew's strain theory to suicide as an “analogous behavior.” Through an analysis of medical examiner case files of suicide data in Detroit, Stack and Wasserman (2007) identified all three of Agnew's strain dimensions (blockage of goals, loss, and unfair outcomes) among the suicides. They found that, for example, Agnew's loss dimension of strain corresponded with unemployment, and the gap between outcomes and expectations was witnessed in declining sales in family-owned small businesses and indebtedness (Stack & Wasserman, 2007).

The Strain Theory of Suicide

While crime usually involves outward acts of violence with physical victims, suicide is an inward violence without other physical victims, and both crime and suicide could result from strain that has brought about negative emotions, such as anger, depression, resentment, and dissatisfaction. However, the strains that precede suicidal behavior may not only be economically-based as exemplified in Agnew's three strains. There are other intellectual observations that help us conceptualize the current strain theory of suicide.

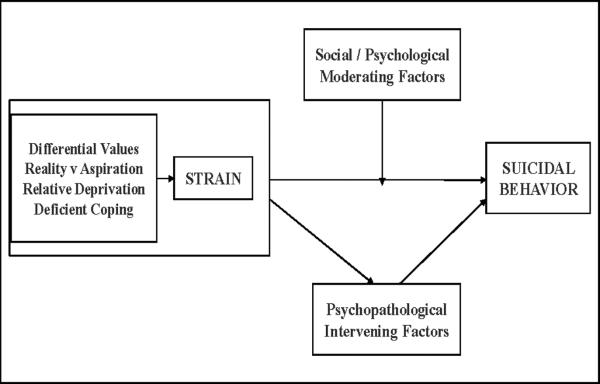

Strain cannot be equivalent to simple pressure or stress. People may frequently have stress but not necessarily strain in their lifetime. While a pressure or stress in daily life is a single variable phenomenon, a strain is made up of at least two pressures or two variables. Examples include at least two differential cultural values, aspiration and reality, one's own status and that of others, and a crisis and coping ability. The extreme solution for a strain is suicide. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed diagram for the relationship between strain and suicide.

Figure 1.

Psychological Strains and Suicide: A Theoretical Model

Strain may lead to negative emotions and/or mental disorders, including substance abuse and alcohol abuse, and may precede other deviant behaviors, such as property crimes and personal assaults (Merton, 1957). In the relationship between strain and suicide, negative emotions and mental disorders may be mediators that provide a mechanism, in addition to the direct link between strain and suicide. On the other hand, the relationship between strain and suicide may be moderated by social integration, social regulation, and psychological factors, such as personality. An individual well integrated into a social institution, such as family, religion, school, and employment, may be at lower risk of suicide, even when confronting a major strain (Durkheim, 1951). The moderators and interveners in the model should play very important roles in determining the probability of suicide resulting from strain. They could be the factors that help distinguish individuals who experience any type of strain and commit suicide from those who experience the same type of strain but do not commit suicide.

There could be four types of strain that precede a suicide, and each can be derived from specific sources. A source of strain must consist of at least two conflicting social facts. If the two social facts are non-contradictory, there would be no strain.

Strain Source 1: Differential Values

When two conflicting social values or beliefs are competing in an individual's daily life, the person experiences value strain. The two conflicting social facts are competing personal beliefs internalized in the person's value system. A cult member may experience strain if the mainstream culture and the cult religion are both considered important in the cult member's daily life. Other examples include second generation immigrants in the United States who have to abide by the ethnic and cultural rules enforced in the family while simultaneously adapting to the American culture with peers and at school. In China, rural young women appreciate gender egalitarianism advocated by the communist government, but at the same time, they are trapped in cultural sexual discrimination as traditionally cultivated by Confucianism. Another example that might be found in developing countries is the differential values of traditional collectivism and modern individualism. When the two conflicting values are taken as equally important in a person's daily life, the person experiences great strain. When one value is more important than the other, there is then little or no strain.

Strain Source 2: Reality vs. Aspiration

If there is a discrepancy between an individual's aspiration or highest goal and the reality with which the person has to live, the person experiences aspiration strain. The two conflicting social facts are one's splendid ideal or goal and the reality that may prevent one from achieving it. An individual living in the United States may expect to be very wealthy or at least as moderately successful as other Americans, but, in reality, the means to achieve the goal may not be equally available to the person because of his/her social status or any other reasons. Aspirations or goals can include attending a particular college, marrying a certain woman, or attainment of a social or political goal. If the reality is far from the aspiration, the person experiences strain. Another example might be from rural China. A young woman aspiring to equal opportunity and equal treatment may have to live within the traditional and Confucian reality exemplified by her family and village, which interferes with that goal. The larger the discrepancy between aspiration and reality, the greater the strain will be.

Strain Source 3: Relative Deprivation

In the situation in which an extremely economically poor individual realizes some other people of the same or similar background are leading a much better life, the person experiences deprivation strain. The two conflicting social facts are one's own miserable life and the perceived richness of comparative others. A person living in absolute poverty, where there is no comparison with others, does not necessarily feel bad, miserable, or deprived. On the other hand, if the same poor person understands that other people like him/her live a better life, he or she may feel deprived because of these circumstances. In an economically polarized society where the rich and poor live geographically close to each other, people are more likely to feel this discrepancy. In today's rural China, television, newspaper, magazines, and radio have brought home to rural youths the relative affluence of urban life. Additionally, those young people who went to work in the cities (dagong) and returned to the village during holidays with luxury materials and exciting stories make the relative deprivation even more realistically perceived. Increased perception of deprivation indicates relatively greater strain for individuals.

Strain Source 4: Deficient Coping

Facing a life crisis, some individuals are not able to cope with it, and then they experience coping strain. The two conflicting social facts are life crisis and the appropriate coping capacity. All people who have experienced crises do not experience strain. A crisis may be a pressure or stress in daily life, and those individuals who are not able to cope with the crisis have strain. Crises such as loss of money, loss of status, loss of face, divorce, or death of a loved one may lead to serious strain in the person who does not know how to cope with these negative life events. A high school boy who is constantly bullied and ridiculed by peers may experience great strain if he does not know how to deal with the situation. Likewise, a Chinese rural young woman who is frequently wronged by her mother-in-law may have strain if she is not psychologically ready to cope with a different situation by seeking support from other family members and the village. The less capable the coping skills, the stronger the strain when a crisis takes place.

The Strain Theory of Suicide and Agnew's General Strain Theory

The conceptualization of the strain theory of suicide is derived from and built on the previous work by Durkheim (1951), Merton (1957), and Agnew (1992, 2006). While the concepts of “reality vs. aspiration” and “relative deprivation” existed in previous literature, “value strain” due to contradictory cultural values is an additional component of the theory. “Deficient coping” measures the lack of positive coping skills and is regarded as a pre-existent behavior of an individual, while in Agnew's analyses, coping is usually treated as a mediator or an outcome (Agnew, 2006). As a pre-existent individual condition, lack of positive coping skills may also moderate the paths from other strains to suicidal behaviors. However, it is critical to keep deficient coping as one of the four sources of strain in the strain theory of suicide. For example, in many of the impulsive suicide cases by rural young men and women in China, no clues of values conflict, failed aspiration, or relative deprivation were found in our previous studies (Zhang, Dong, Delprino, & Zhou, 2009). The four types of strains are not mutually exclusive. Four previous studies with American and Chinese data have validated the strain measures and found that a suicide may have two or more types of strains preceding the suicide behavior (Zhang, 2010; Zhang, et al., 2009; Zhang & Lester, 2008).

As reviewed above, the strain theory of suicide attributes suicidal behavior to social factors and influence. Similar theoretical framework can be found in the frustration- aggression theory of deviance, which says that frustration – the perception that a person is being prevented from obtaining a goal – will increase the probability of an aggressive response (Barker, Dembo, & Lewin, 1941). In another classical study of aggression, social class and status can turn out to be important variables in determining the direction of lethal violence, either outward (homicide) or inward (suicide) (Henry & Short, 1954). Those classical sociological thoughts have also laid a foundation for the current strain theory of suicide.

Integrating Strain in the Model of Suicide Risks

Demographic and social factors that may moderate the association between psychological strains and suicide include education, marital status, and religion and religiosity. Durkheim's social integration theory of suicide has been frequently supported by Western data. In an overview of the European socio-economic inequalities in suicide mortality among men and women, Lorant et al. (2005) found a low level of educational attainment to be a risk factor for male suicide in eight out of ten countries (Lorant et al., 2005). With an American longitudinal data set, Kposowa (2000) found higher risks of suicide in divorced than in married persons (Kposowa, 2000). Divorced and separated persons were over twice as likely to commit suicide as married persons. Being single or widowed had no significant effect on suicide risk. When data were stratified by gender, it was observed that the risk of suicide among divorced men was over twice that of married men. Among women, however, there were no statistically significant differences in the risk of suicide by marital status categories (Stack, 2000). To accurately assess the impact of religion on suicidality, Gearing and Zilardi (2008) searched the PsycINFO and MEDLINE databases for published articles on religion and suicide between 1980 and 2008 (Gearing & Lizardi, 2008). Epidemiological data on suicidality across four religions (Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam) and the influence of religion on suicidality were presented. Suicide rates and risk and protective factors for suicide varied across religions, although one's degree of religiosity could potentially serve as a protective factor against suicidal behavior (Koenig, McGue, Krueger, & Bouchard, 2005).

Psychopathological factors are the intervening variables in our theoretical model. Mental disorders, including substance use disorders (SUD) and alcohol use disorders (AUD), affect over 90% of all people who die by suicide in the United States (NIMH, 2009). The strong covariance existing between mental disorder and suicidality may imply that they are co-morbidities. The strain theory of suicide hypothesizes that the upstream cause for both mental disorders and suicidality is psychological strain resulting from social interactions, including those involved with cultural values.

METHOD

Psychological Autopsy

The method of psychological autopsy (PA), established by Robins and colleagues in 1959, is a data collection approach in suicide research and is well established in the West as the means for obtaining comprehensive retrospective information about victims of completed suicide (Beskow, Runeson, & Asgard, 1990; Robin, Murphy, Wilkinson, Gassner, & Kayes, 1959). A variety of sources of information are used in PA studies, including evidence presented at inquest, medical records, and information from general practitioners and hospital clinicians. The most important source, however, is interview of relatives and other key informants. Although in the past years there has been a developing consensus on the essential ingredients of rigorous PA studies (Beskow, et al., 1990; Younger, Clark, Oehmig-Lindroth, & Stein, 1990), questions remain about the method's reliability and validity. A major concern of the method is the validity of the proxy responses that are supposed to accurately represent what the dead would have responded. However, the best indicator of the reliability and validity of the method is provided by the consistency of findings across PA studies (Brent, Perper, Kolko, & Zelenak, 1988). Kraemer and colleagues (2003) developed a model of informant selection that chooses the right informants by conceptualizing the most relevant contexts and perspectives (Kraemer et al., 2003).

Samples

The samples for the study included rural young men and women aged 15–34. We study this age cohort because of its high risk of suicide in rural China. We used established psychological autopsy methods and a case-control design to investigate the environments and factors of rural young suicides. Samples were from three provinces in China. Liaoning is an industrial province located in Northeast China, Hunan is an agricultural province in the Central South China, and Shandong is a province with economic prosperity in both industry and agriculture and is located on the east coast of China midway between Liaoning and Hunan. The three provinces have been selected for study because of their geographical locations and the comparative representation of the Chinese populations. Sixteen rural counties were randomly selected from the three provinces (6 from Liaoning, 5 from Hunan, and 5 from Shandong). In each of the 16 counties, suicides aged 15–34 were consecutively recruited from the county health administrations from October 2005 through June 2008. Similar numbers of community living controls were recruited in the same counties during about the same time periods. After successful interviews with the informants of the suicides, a total number of 392 suicide cases were entered for study. Among the 392 suicides, 178 were female and 214 male.

The community living control group was a random sample stratified by age range and county. In each province, we used the 2005 census database of the counties in our research. For each suicide, we utilized the database of the county where the deceased lived to randomly select a living control in the same age range (i.e., 15–34). As to gender, the random selection of controls aged 15–34 from each county database yielded approximately 50% of males and 50% of females, which also approximated the gender distribution of suicide cases in the study. The control sample did not exclude individuals who had been diagnosed with mental disorders or previous suicide attempts. This way, the prevalence of mental diseases and suicidal attempts could be assessed in the rural general populations aged 15–34, and more important, the effects (direct, moderating, and intervening) of mental disorders on completed suicide could be studied.

The research protocol was approved by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH), the funding agency for this study. The research methods and the questionnaire for interview were approved by State University of New York Buffalo State Institutional Review Board (IRB), where the principal investigator of the project is affiliated. IRB approvals were also obtained from the three provinces in China.

Information sources

For each suicide and each control, we tried to interview at least two informants. To obtain some parallel data as from the suicide cases, we also used proxy information from the controls. However, we noticed that the type of informants, rather than the number of informants, used in psychological autopsy studies was an extremely important and complex consideration (Kraemer, et al., 2003). Each carefully selected informant was supposed to report reliable information about the specific characteristic, recognizing that it is likely no one informant has all the pertinent information (Zhang et al., 2010).

Inter-rater reliability was established and maintained by limiting the principle data gathering role to 24 trained clinical interviewers and by comparison of duplicate ratings of the interviewers on a regular basis. The same interviewers participated in data collection for both case and control samples, promoting inter-rater reliability across that study boundary.

Measurements

The study used a case-control design. The dependent variable of the analyses was dichotomous for the case-control status: suicide and living control. The risk factors in this study included gender, age, education, marital status, religiosity, mental disorder, and the four aspects of psychological strain respectively in differential values, reality versus aspiration, relative deprivation, and deficient coping.

Both age and education were measured by the number of years. Marital status was recoded into never married and ever-married. The category of “ever-married” included currently married and living together, currently married but separated because of work, remarried, divorced, widowed and those non-married couples who lived together. We did not further identify subgroups for the ever-married people because of the lack of observations in the divorced and widowed classifications. There were four items in the protocol to assess religion and religiosity of the cases and controls. The first asked what religion the target person believed in, and the choices were Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, other, and none. The second item asked about how many times in an average month the target person attended religious events. The third and fourth questions asked if the target person believed in God and an afterlife. The variable of religiosity was the sum total of the four items, and it is a dichotomous variable with Yes=1 with any of the four items being positive and No=0 for all other responses or no response.

We used the Chinese version of SCID (Spitzer, et al., 1988) to generate diagnoses for both suicides and living controls. Because a target person's circumstances were generally assessed through two informants interviewed by researchers, discrepancies between informants might occur, due to different information available to each of them. Nonetheless, we should have one and only one assessment for each target person on an item. Consensus meetings were held every evening by the interviewers at the interview site to provide a chance for the interviewers to put the information together so as to reach a single assessment. This is particularly critical for mental health diagnoses assessed by the SCID. The psychiatrists on the team made a diagnosis decision for each suicide and control with the interview forms and discussions.

To apply a set of differential values to the study, we chose the conflicting values between communist gender equalitarianism and Confucian gender discrimination. We proposed that when both values were highly scored by an individual, value strain could be observed for the individual.

Both communist gender equalitarianism (modern scale) and Confucian sexism against women (traditional scale) were measured on Likert categories (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree). For the modern scale, respondents were asked to what extent the target person agrees with the following statements: (1) “going out to work,” (2) “equality for men and women,” (3) “marriage based on self choice,” (4) “a woman to receive education,” (5) “equal pay for equal work,” (6) “women can uphold half the sky,” (7) “women can do all that men can do,” and (8) “men and women are equally important.” The eight items were highly consistent to indicate a very good reliability, and the alpha values were 0.83 for the suicide cases, 0.89 for the controls, and 0.83 for the total.

For the traditional scale, respondents were asked to what extent the target person agrees with the following statements: (1) “women should stay and work only at home,” (2) “caring for her husband,” (3) “bearing a son,” (4) “keeping marriage without divorce,” (5) “arranged marriage,” (6) “obedience to men,” (7) “no education for women,” (8) “no social life,” (9) “women at home and men outside,” (10) “a woman should not exceed her husband in education,” (11) “a man is more important than a woman,” and (12) “a woman should be with only one man, live or dead.” Both scales have been validated in previous studies with rural Chinese populations (Zhang & Song, 2006). The reliability alphas for the 12 items were 0.81 for the cases, 0.81 for the controls, and 0.82 for the total sample.

As expected, for both case and control groups, responses to the modern scale skewed to the high end of the measurement. Approximately 90% of the responses were between 4 and 5, and the remaining responses were between 3 and 4. Therefore, we assumed that the communist gender equalitarianism was a social value in the samples we obtained from rural China. Those in the samples who also scored high on Confucian traditional scale must have experienced value strain. Thus, we used the traditional scale to represent the strain measure for differential values.

The aspiration strain was assessed with two questions. We first asked what the biggest wish the target person might have, and then we asked whether the aspiration was realized by the target person either before the death (for suicides) or prior to the interview (for controls). Those individuals who had experienced failed aspiration were supposed to have a psychological strain. Relative deprivation was assessed by the perception of the economic status of the family of the target person in comparison with people in the same village. There were five categories of choice: 1=excellent, 2=good, 3=average, 4=bad, and 5=worst. Psychological strains were assumed to occur when people experienced relative poverty rather than absolute poverty. Lack of coping skills in response to a life crisis created a psychological strain on the individual. Therefore, the level of coping skills could be the measure of coping strain. Moos's (Moos, Brennan, Fondacaro, & Moos, 1990) Coping Responses Inventory (CRI) asked subjects to evaluate the frequency in responding to 48 items as 0 (never), 1 (occasionally), 2 (sometimes) or 3 (often). The scale had 24 positive (approach) coping skill items and 24 negative (avoidance) ones. We used the 24 positive coping skills for the current study. Examples of the positive coping skills included “talk with your spouse or other relative about the problem,” and “think about how this event could change your life in a positive way.” The reliability alphas of the 24 positive coping items were 0.91 for the cases, 0.85 for the controls, and 0.93 for the total sample.

Integrating the information from different sources

There were two proxy interviews for each suicide case and each living control. Majority of the responses for the target person were same or similar. For the different responses on the target person, data were integrated with the following three principles. For the demographic information, we relied on the answers by the informant who should know it best. For example, a family member should be able to tell the target person's age and birth date more accurately than does a friend. Second, in estimating the cultural values of the target person, we used the average of the two informants' responses if they are different. Finally, to determine a diagnosis with the SCID, we always selected the positive response (e.g., existence of a symptom) on a measurement. These three guidelines were applied in integrating responses of both cases and controls.

MPlus (Muthen & Muthen, 2006) and logistic Structural Equation Model (SEM) were employed for the mediation analyses. We used alpha = .05 to identify statistically significant results because the analyses were used to examine a priori hypotheses pertaining to the risk factors that were measured.

RESULTS

The final sample from the three provinces consisted of 392 suicides (178 females and 214 males) and 416 living controls (214 females and 202 males). They were all from rural China and aged between 15 and 34 years at the time of death or interview. Of the 392 suicides, 299 (76%) died by swallowing pesticides, other poison, or overdose of sleeping pills, 41 (11%) died by hanging, 20 (5%) died by drowning, and 7 (2%) died by jumping from a high place. The remainder (6%) died of other methods. All deaths were confirmed to be suicide by consensus from the family members, village doctors, local medical agencies, and the police.

Table 1 presents the case-control differences in the means and percentages of the major variables by gender. The suicide group and the control group differed significantly on all factors but the marital status. The age ranged from 15 to 34 years with a mean of 26.9 years (SD=6.3) for the suicide sample and 25.9 years (SD=6.2) for the controls. Combined male and female, suicides were older than living controls. However, the difference was not significant for females in the study. The number of years of formal education ranged from 0 to 16 with a mean of 7.4 (SD=2.8) for the suicides and from 2 to 18 with a mean of 9.2 (SD=2.4) for the living controls. The number of education years was lower for the suicides than for the controls for both men and women. There was no marital status (never married vs. ever-married) difference between the suicides and controls. Among those ever married, the groups of divorced and widowed were so small that statistical comparisons were not feasible. About 28.8 percent (n=113) of the suicides believed in any religion, but only 16.8 percent (n=70) of the living controls believed in any religion. The case-control difference in religion was larger for men than for women. While 47.7 percent (n=187) of the suicides were diagnosed with at least one mental disorder, including alcohol and substance abuse, only 2.6 percent (n=11) of the living controls were with any kind of mental disease, including alcohol and substance abuse. Table 1 also shows that suicides scored significantly higher than controls on the Confucian traditional gender value, failed aspiration, economic deprivation, and lack of coping skills. The case-control differences in all four strain measures were significant for both men and women.

Table 1.

Distribution (Means and Percentages) of the Major Variables for Analyses

| Variable | Males |

Females |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicides (n=214) | Controls (n=202) | Suicides (n=178) | Controls (n=214) | Suicides (n=392) | Controls (n=414) | |

| Age (Year) | 26.87* | 25.48 | 26.83 | 25.87 | 26.85** | 25.86 |

| Education (Year) | 7.40*** | 9.36 | 7.36*** | 8.94 | 7.38*** | 9.15 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Never Married | 52.34% | 43.56% | 27.53% | 26.17% | 41.07% | 34.78% |

| Ever-Married | 47.66% | 56.44% | 72.47% | 73.83% | 58.93% | 65.22% |

| Living Together | 37.85% | 54.95% | 62.92% | 71.96% | 49.23% | 64.01% |

| Separated/Work | 3.74% | 0 | 1.69% | 4.67% | 2.81% | 0.24% |

| Remarried | 0.47% | 0.50% | 2.25% | 0 | 1.28% | 0.24% |

| Divorced | 3.74% | 0.99% | 3.37% | 0.93% | 3.57% | 0.97% |

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | 0.56% | 0 | 0.26% | 0 |

| Cohabitation | 1.87% | 0 | 1.69% | 0.47% | 1.79% | 0.24% |

| Religion | ||||||

| Believing in Any | 24.77%*** | 9.90% | 33.71%* | 23.58% | 28.83%*** | 16.83% |

| Not at All | 75.23%*** | 90.10% | 66.29%* | 76.42% | 71.17%*** | 83.17% |

| Psychiatric Diagnosis | ||||||

| Any Mental Illness | 54.21%*** | 2.97% | 38.76%*** | 2.34% | 47.70%*** | 2.64% |

| No | 45.79%*** | 97.03% | 61.24%*** | 97.66% | 52.30%*** | 97.36% |

| Confucianism | 36.66*** | 32.59 | 34.66*** | 32.35 | 35.75*** | 32.47 |

| Aspiration (Failed) | 95.56%*** | 81.61% | 93.23%*** | 75.00% | 94.57%*** | 78.40% |

| Relative Poverty | 3.73*** | 3.03 | 3.49*** | 3.02 | 3.62*** | 3.03 |

| Coping Skills | 20.36*** | 39.58 | 20.15*** | 38.38 | 20.27*** | 38.95 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

The risk factors for suicide were estimated by multiple logistic regressions with alpha = .05 to identify statistically significant results because the analyses were used to examine a priori hypotheses pertaining to the risk factors that were measured. Table 2 presents the results separately for men and women.

Table 2.

Logistic Multiple Regressions Estimating the Major Risk Factors for Rural Young Male and Female Suicide in China

| Predicting Variables | Males (n=416) | Females (n=392) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Sig. | Coefficient | Sig. | |

| Constant | 0.87 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.90 |

| Age (Year) | −0.01 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| Education (Year) | −0.26 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.39 |

| Religion (Yes) | 0.62 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 0.22 |

| Psychiatric Diagnosis (Yes) | 3.34 | <0.01 | 2.50 | <0.01 |

| Confucianism | 0.01 | 0.71 | −0.02 | 0.57 |

| Aspiration (Failed) | 1.67 | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.08 |

| Relative Poverty | 0.60 | 0.01 | 0.82 | <0.01 |

| Coping Skills | −0.11 | <0.01 | −0.14 | <0.01 |

Nagelkerke R Square for men' model is 0.72. Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi-Square is 11.75 and P is 0.16.

Nagelkerke R Square for women' model is 0.66. Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi-Square is 1.87 and P is 0.98.

Marital status was not entered in the logistic multiple regression model, as it did not distinguish the case-control status for either men or women. In the regression model, the strongest predictor of suicide was psychiatric diagnosis. For rural young men and women in China, the diagnosed mental disorder is highly correlated with suicide risk. The second strongest predictor of suicide was coping skills. For both rural young men and rural young women, the higher the level of coping skills, the lower the risk of suicide. More years of education reduced suicide risk for men but not for women, and age was not related to suicide risk in the regression analyses. The tendency that suicides were more religious than controls evidenced in the bivariate analysis failed to reach a significant level in the multiple regression analyses.

The score on Confucianism was not associated with suicide risk in the multiple regression analyses. Failed aspiration was related to suicide risk for men but not necessarily for women. As expected, both economic deprivation and lack of coping skills were significantly associated with suicide risk for both men and women. Economic deprivation was directly associated with suicide, while coping skills were inversely associated with suicide.

To assess the association between strain and suicide and the role of mental illness in the association, we performed mediation analyses with MPlus (Muthen & Muthen, 2006) using a logistic Structural Equation Model (SEM) with a binary endogenous variable (1=suicide; 0=living control) and a mediator (1=any mental illness; 0=no mental illness). We assumed multi-normality of the error terms.

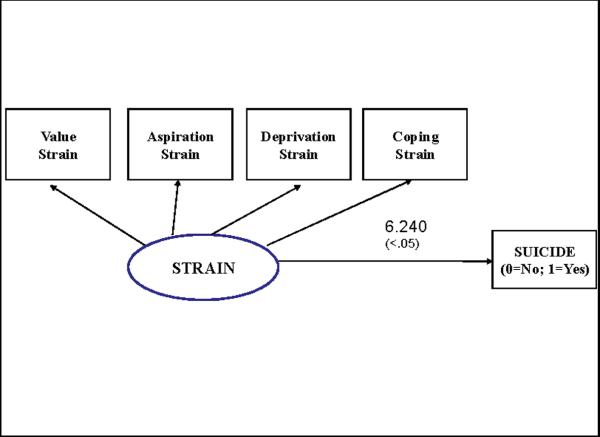

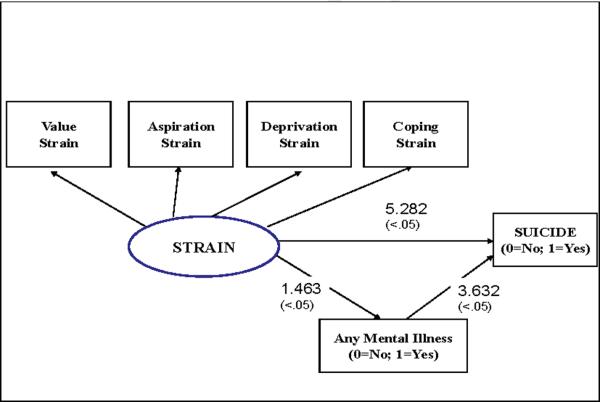

First, a path diagram was drawn to clarify the relationship. Strain as a latent construct was formed from the four strain measures: value strain, aspiration strain, deprivation strain, and coping strain using confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) in MPlus, fixing the factor variance to one. Gender and age were controlled for in the analyses.

The direct relationship regressing suicide status on strain was examined using logistic regression with maximum likelihood estimation. Because this relationship was significant, we tested for the meditational models with maximum likelihood estimation. Mental illness was found to be a partial mediator, since the estimate for strain decreases when mental illness was included in the model. There are significant relationships between strain and mental illness and between mental illness and suicide. See Figures 2 and 3 for the estimates.

Figure 2.

Logistic Model for Strain to Suicide in Rural China with Gender and Age as Covariates

Figure 3.

Path Diagram from Strain to Suicide with Mental Illness as a Mediator in Rural China (Gender and Age as Covariates)

DISCUSSION

The central findings are that all four types of strain are associated with suicide, although the association for the value strain is not significantly observed in the multiple regression model. The aspiration strain, deprivation strain, and coping strain are all strong predictors of suicide even after controlling for psychiatric diagnosis, age, education, and religion. Strain is a psychological frustration resulting from at least two conflicting stressors. A single stressor does not necessarily lead to frustration, such as absolute poverty, high expectation for future, a personal crisis, and an extreme cultural value. Frustration or strain occurs only if the stressor confronts a competing stressor.

When everyone is living in poverty, poverty is not a stressor. With everything else being held equal, a person's miserable living condition is perceived in relation to others, and the person feels frustrated. Relative poverty or deprivation may be objectively measured, but must be subjectively perceived by the individual who is at suicide risk. Agnew (1992) derived much of his strain theory from the justice literature and linked the psychological frustration resulting from the perceived injustice to deviant behaviors.

High aspiration for future can also become frustration and strain if the reality does not allow the individual to move to or to reach the goal the individual aspired. We divided the subjects who had an aspiration into those who realized their wishes and those who did not realize their wishes and confirmed that a failed aspiration is a strain that leads to suicide. For the suicides in the current sample, the top four failed aspirations were (1) making more money, (2) harmonious family, (3) love and marriage, and (4) job security. Most people should have experienced a crisis in life, but few people in crisis situation were so frustrated as to kill themselves.

Only those who do not have a coping ability become extremely frustrated and seek death as a solution to solve the problems inflicted by the crisis. We measured the coping skills with a standardized instrument and confirmed that those individuals who have better coping skills have lower suicide risk.

Mental illness is a mediator in Chinese suicide. Psychological strains increased the level of mental illness, and mental illness then increased the risk of suicide. However, approximately half of the Chinese suicides in this study were not diagnosed with any psychiatric problems. Psychological strain by itself can also be a strong predictor of suicide in Chinese culture.

The effect of religion/religiosity is reversed in the Chinese culture -- it tends to be detrimental for Chinese rural young people in terms of suicidality. Because of beliefs and social integration, sociologists since Durkheim have argued that religion protected people from suicide (Stack, 2000). Previous studies noted suicide rates are lower in religious countries than in the secular ones (Breault, 1986; Stack, 1983) and low religiosity is associated with suicidal ideation, as well as suicidal behaviors (Cook, Pearson, Thompson, Black, & Rabins, 2002), although no studies have established an association between specific religious denomination (i.e., Catholic versus Protestant) and suicidal behavior (Dervic et al., 2004). In China, Buddhism and Taoism, foundations of traditional Chinese culture, are different from Western religions in terms of supernatural being, afterlife, rituals, and organization (Zhang & Xu, 2007). In Chinese religions, there is not a single God to worship, and there is a lack of social support system and coping mechanisms, as the majority of the religious people do not meet regularly. Compared with an institutionalized religion, social interaction and social support are absent in private worships (Pescosolido & Georgiana, 1989). Different from all the mainstream religions in the West, Chinese religions are often associated with superstition as the saying of zongjiao mixin (religious superstition). To some Chinese individuals, being religious is equivalent to being superstitious, and death is a solution to all the problems and the beginning of a new life (incarnation). Therefore, it is possible that those who take religion to the extreme are likely to think about starting a new life by ending this current one quickly.

We should also understand the finding that religiosity is related to Chinese suicide, in line with the strain theory of suicide. As an atheist country, China now has less than 10 percent of its population claiming themselves religious, and this percentage has reflected the rapid growth in the past 30 or so years since China opened its door to the West (Badham, 2008; Yao & Badham, 2008). Church and prayer are still considered to be deviant to the majority of the Chinese (Zhang, et al., 2010). Additionally, those churchgoers in China may also experience the psychological frustration caused by their religious beliefs that conflict with the mainstream culture in the larger society. The value conflict strain increases when the two conflicting values are both internalized in an individual. In sum, three differences between the Western and Chinese religious practices account for the different effects of religion on suicidality between the two cultures: (1) the lower level of institutionalization of religions in China offers less social support to believers than in the West; (2) the Buddhist incarnation may encourage the superstitious believers to gloriously end their own life; (3) the Chinese religious believers are treated as a minority group, both due to its small percentage and political disadvantage. Value strains can be experienced between the main stream values in society and their subcultural values.

Psychological strains are presumed to be the up-stream reason that leads to both mental problem and suicidality. Further studies in various populations and more sophisticated measures should be conducted to improve and refine this strain theory of suicide, as this knowledge may be critical for reducing suicides at all three levels of prevention. For first degree prevention (universal), the government needs to carry out and reinforce the policies that help reduce economic polarizations in society so as to bring down certain individuals' anger and frustration caused by the aspiration strain, as well as the relative deprivation strain. At the behavioral level, efforts to reduce strain include increasing coping skills through early childhood education interventions. For second degree prevention (selective), for support reasons, we need to identify individuals who are outliers socially in a village or community (relatively poorer than their peers), and social welfare systems should work for those people in need. For third degree prevention (indicated), we have to develop some psychological counseling strategies (strain reduction through cognitive therapy) to care those individuals at the suicidal edge, or screen and refer for treatment people who develop mental illness.

One unique contribution of this study to sociological research of suicide is that it employed a rare blend between psychiatric and social predictors of suicide, where the Chinese version of the SCID was administered to measure psychiatric disorders of both suicides and living controls. The study shows that social factors influence suicide risk independent of the dominant risk factor for suicide, psychiatric illness. Further, the strain theory is first tested in Chinese culture. Hopefully, the present paper will stimulate work in other cultures to test the strain theory of suicide and in a variety of fields beyond just suicide studies.

One limitation of the study is the measurement through the psychological autopsy process. People could question the validity of the responses from proxy informants on behalf of the target persons. It may be difficult, if not impossible, for a proxy to understand the psychological process of a suicide. Recall bias could be another concern. It is noted that, for aspiration strain, family members of the suicide could be more likely to report that the wish of the deceased was not fulfilled to justify the suicidal incident. Another weakness of the proxy method is shown in the measure of value conflicts of the suicides. This may account for the insignificant fit of value conflicts strain in the comprehensive model predicting Chinese rural youth suicide. Future studies may interview suicide attempters to directly obtain the information for the targets' personal values. Nonetheless, psychological autopsy may be the only cost-effective way to assess the background and experiences of the deceased before the suicide incident (Hawton et al., 1998).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of US NIMH: R01 MH068560. We thank our research collaborators in Liaoning, Hunan, and Shandong of China. We also thank all the interviewees for their unique contribution to the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30(1):47–87. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. General Strain Theory: Current Status and Directions for Further Research. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins K, editors. Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory-Advances in Criminological Theory. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 2006. pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R, editor. An overview of general strain theory. LA: Roxbury: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Badham P. Religion in Britain and China: Similarities and Differences. Modern Believing. 2008;49(1):50. [Google Scholar]

- Barker R, Dembo T, Lewin K. Frustration and aggression: An experiment with young children. University of Iowa Studies in Child Welfare. 1941;18:1–314. [Google Scholar]

- Beskow J, Runeson B, Asgard U. Psychological autopsies: Methods and ethics. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1990;20:307–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breault KD. Suicide in America: A Test of Durkheim's Theory of Religious and Family Integration, 1933–1980. American Journal of Sociology. 1986;92(3):628–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Kolko DJ, Zelenak JP. The psychological autopsy: Methodological considerations for the study of adolescent suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:362–366. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198805000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JM, Pearson JL, Thompson R, Black BS, Rabins PV. Suicidality in older African Americans: findings from the EPOCH study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):437–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervic K, Oquendo MA, Grunebaum MF, Ellis S, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Religious affiliation and suicide attempt. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2303–2308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Free Press; New York: 1951. Original work published in 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Gearing R, Lizardi D. Religion and Suicide. Journal of Religion and Health. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9181-2. Published online( http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-008-9181-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Appleby L, Platt S, Foster S, Cooper J, Malmberg A, et al. The psychological autopsy approach to studying suicide: A review of methodological issues. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;50:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringen KV. The neurobiology of suicide and suicidality. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;48(5):292–300. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry AF, Short J. Suicide and Homicide: Some Economic, Sociological and Psychological Aspects of Aggression. Free Press; Glencoe, IL: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- IOM, I. o. M. Reducing suicide: An American imperative. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jang SJ, Johnson BR. Strain, negative emotions, and deviant coping among African Americans: A test of general strain theory. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2003;19:79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig L, McGue M, Krueger R, Bouchard T. Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kposowa AJ. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2000;54(4):254–261. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Kupfer DJ. A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1566–1577. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Costa G, Mackenbach J, Health, E. U. W. G. o. S.-E. I. i. Socio-economic inequalities in suicide: a European comparative study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187(1):49–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):181–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social Theory and Social Structure. rev. ed. Free Press; New York: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Brennan PL, Fondacaro MR, Moos BS. Approach and avoidance coping responses among older problem and nonproblem drinkers. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5(1):31–40. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen LK. Mplus User's Guide. 4th Edition Muthen & Muthen; CA: Los Angeles: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- NCIPC . Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH . Research on Reduction and Prevention of Suicidality. National Institute of Mental Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH Suicide in the US: Statistics and Prevention. 2009 Retrieved Feb, 3, 2009, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/harmsway.cfm.

- Pescosolido B, Georgiana S. Durkheim, suicide and religion. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, Li X, Zhang Y. Suicide rates in China, 1995–99. The Lancet. 2002;359(9359):835–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. The Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin E, Murphy GE, Wilkinson RH, Gassner S, Kayes J. Some clinical considerations in the prevention of suicide based on a study of 134 successful suicides. American Journal of Public Health. 1959;49:888–889. doi: 10.2105/ajph.49.7.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First AB. Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID, 6/1/88 Revision) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. The Effect of Religious Commitment on Suicide: A Cross-National Analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):362–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. Suicide: A 15-Year Review of the Sociological Literature, Part II: Modernization and Social Integration. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30(2):163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S, Wasserman I. Economic Strain and Suicide Risk: A Qualitative Analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37(1):103–112. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Li Y, Chi G, Xiao S, Ozanne-Smith J, Stevenson M, et al. Injury-related fatalities in China: an under-recognised public-health problem. The Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1765–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . The World Health Report. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Badham P. Religious Experience in Contemporary China. University of Wales Press; Banglor: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Younger SC, Clark DC, Oehmig-Lindroth R, Stein RJ. Availability of knowledgeable informants for a psychological autopsy study of suicides committed by elderly people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38(11):1169–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Marriage and Suicide among Chinese Rural Young Women. Social Forces. 2010;89(1):311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Dong N, Delprino R, Zhou L. Psychological Strains Found From In-Depth Interviews With 105 Chinese Rural Youth Suicides. Archives of Suicide Research. 2009;13(2):185–194. doi: 10.1080/13811110902835155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lester D. Psychological Tensions Found in Suicide Notes: A Test for the Strain Theory of Suicide. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12(1):67–73. doi: 10.1080/13811110701800962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Song Z. A Preliminary Test of the Strain Theory of Suicide. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2006;15(6):487–489. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wieczorek WF, Conwell Y, Tu XM, Wu BYW, Xiao S, et al. Characteristics of young rural Chinese suicides: a psychological autopsy study. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(4):581–589. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xu H. The effects of religion, superstition, and perceived gender inequality on the degree of suicide intent: A study of serious attempters in China. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 2007;55(3):185–197. doi: 10.2190/OM.55.3.b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]