Abstract

The voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.3 has been reported to regulate transmitter release in select central and peripheral neurons. In this study, we evaluated its role at the synapse between visceral sensory afferents and secondary neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). We identified mRNA and protein for Kv1.3 in rat nodose ganglia using RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. In immunohistochemical experiments, anti-Kv1.3 immunoreactivity was very strong in internal organelles in the soma of nodose neurons with a weaker distribution near the plasma membrane. Anti-Kv1.3 was also identified in the axonal branches that project centrally, including their presynaptic terminals in the medial and commissural NTS. In current-clamp experiments, margatoxin (MgTx), a high-affinity blocker of Kv1.3, produced an increase in action potential duration in C-type but not A- or Ah-type neurons. To evaluate the role of Kv1.3 at the presynaptic terminal, we examined the effect of MgTx on tract evoked monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in brain slices of the NTS. MgTx increased the amplitude of evoked EPSCs in a subset of neurons, with the major increase occurring during the first stimuli in a 20-Hz train. These data, together with the results from somal recordings, support the hypothesis that Kv1.3 regulates the duration of the action potential in the presynaptic terminal of C fibers, limiting transmitter release to the postsynaptic cell.

Keywords: nodose, margatoxin, potassium channels, cumulative inactivation

the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.3, best known for its role in immunological responses in lymphocytes, is also present in select populations of central and peripheral neurons. Kv1.3 has been reported to be targeted primarily to axons (Veh et al. 1995; Rivera et al. 2005) and to be involved in the regulation of transmitter release (Ohno-Shosaku 1996, Shoudai et al. 2007; Doczi et al. 2008). A recent study (Gazula et al. 2010) has identified Kv1.3 in presynaptic terminals in the calyx of Held. In nodose ganglia (NG) visceral sensory neurons, a variety of voltage-gated K+ channels contribute to excitability, including the members of the Kv1 family Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.6 (Glazebrook et al. 2002), the KCNQ family (Wladyka and Kunze 2006), and Kv2.1 (unpublished observations). While we find that these currents collectively account for the majority (>80%) of delayed rectifying and slowly inactivating outward K+ currents in these neurons, a component of this K+ current remains unblocked in the presence of α-dendrotoxin (DTx) to block Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.6, XE-991 to block KCNQ2, KCNQ3, and KCNQ5, and an intracellular Kv2.1 blocking antibody. In surveying the mRNA expression of the K+ channels in NG neurons, we detected the presence of another member of the Kv1 family, Kv1.3. In this study, we asked where Kv1.3 protein is expressed in NG neurons and their axons and whether it plays a role in excitability at central terminals. Specifically, we asked whether Kv1.3 might regulate the duration of the action potential and, thus, potentially alter transmitter release at a presynaptic terminal.

Visceral sensory neurons have been subdivided according to various criteria. Historically, the population was divided into three groups based on the conduction velocity of the axons, action potential duration, and the resistance of voltage-gated Na+ current to TTX (Belmonte and Gallego 1983; Bossu and Feltz 1984; Stansfeld and Wallis 1985). The first group of neurons (A-type neurons) has axons that conduct in the range of fast myelinated fibers and have narrow action potentials, and their Na+ currents are blocked by TTX. The second group (Ah-type neurons) displays broader action potentials than A-type neurons, exhibits a small hump on the falling phase of the action potential, and have axons that conduct in the slow myelinated fiber range (Stansfeld and Wallis 1985, Li and Schild 2007b). Whereas the Ah-type group has not been examined specifically in NG neurons for TTX sensitivity, a comparable group of Ah-type neurons in dorsal root ganglion expresses TTX-resistant Na+ current as well as TTX-sensitive current (Villière and McLachlan 1996). These first two cell groups with myelinated fibers are estimated to make up only 10–25% of the total population based on anatomic and physiological studies (Evans and Murray 1954; Agostoni et al. 1957; Mei et al. 1980; Higashi and Nishi 1982; Yamasaki et al. 2004; Li and Schild 2007b). Finally, the third group (C-type neurons) has the longest duration action potentials, and their voltage-gated Na+ currents are poorly blocked by TTX (Stansfeld and Wallis 1985; Bossu and Feltz 1984; Schild and Kunze 1997). These neurons have axons conducting in the range of unmyelinated fibers. In the present study, we classified the response of nodose neurons to margatoxin (MgTx), a blocker of Kv1.3, based on the duration of the action potential and the presence or absence of TTX-resistant current.

METHODS

Animal protocols.

Animal protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Case Western Reserve University and the University of Missouri, and animals were handled according to their guidelines. With the exception of the postnatal day 1 animals included in the Western blot analysis, all animals were male Sprague-Dawley rats between 4 and 7 wk of age. Postnatal day 1 Sprague-Dawley rats were of mixed sex.

Antibodies.

Two commercial antibodies against Kv1.3 were used in these experiments. The polyclonal antibody (APC-002, lot AN-03, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) generated against a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein corresponding to residues 471–523 of human Kv1.3 protein recognizes a single band (∼65 kDa) on a Western blot (Fig. 1). The antibody preabsorbed with the immunizing peptide was tested in NTS sections and gave no signal. We also used a monoclonal antibody [75-009, lot no. 413–5RR-07, clone L23.27IgG2a, NeuroMab, University of California (Davis, CA)/National Institutes of Health NeuroMab Facility (Davis, CA)] generated against a synthetic peptide corresponding to rat sequence 485–506. This antibody recognizes a band of ∼70 kDa and has been tested in Kv1.3 knockout mice for specificity (NeuroMab). In addition, we used a monoclonal anti-vesicular glutamate transporter antibody (clone N29/29, fusion protein amino acids 501–582, NeuroMab), a goat polyclonal anti-actin antibody (sc-1616; lot no. H0608, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and a mouse monoclonal anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) antibody (MAB 381, amino acids 119–131, Chemicon, Millipore, Billerica, MA).

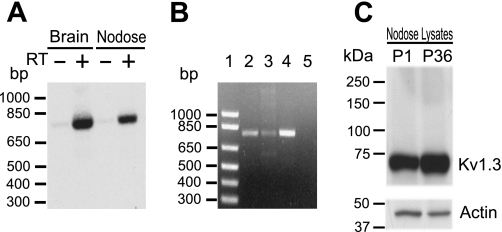

Fig. 1.

Detection of Kv1.3 α-subunits. A: PCR products resulting from the amplification of first-strand cDNA prepared with (+) or without (−) reverse transcriptase (RT) from the rat nodose ganglia (NG) or brain poly-A+ RNA with Kv1.3-specific oligonucleotides were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nylon membranes. After Southern blot hybridization with 32P-labeled specific internal oligomers, the autoradiogram showed positive signals from the rat nodose and brain in +RT lanes and no signals in the control −RT lane. The oligonucleotide probes amplify cDNA of 792 bp. B: the specificity of the primers was tested using a sample of Kv1.3 cDNA. A single band of the predicted size (792 bp) was amplified from NG cDNA (lane 2), Kv1.3 cDNA (lane 3), and nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) cDNA (lane 4). No PCR products were detected in the negative control lane (H2O; lane 5). Lane 1 is a 1-kb DNA ladder. C: Western blot analysis of Kv1.3 protein from the NG. The Kv1.3 receptor was identified in protein lysates from the NG dissected from postnatal day 1 (P1; 50 μg) and postnatal day 36 (P36; 20 μg) rats. A band of ∼65 kDa was detected in both lysates. Mobility of the protein correlated with the molecular size already reported for the Kv1.3 α-subunit (∼65 kDa). Western blot analysis also showed that Kv1.3 protein in neonates is less abundant than that in older animals.

PCR amplification of Kv1.3 α-subunit cDNA fragments.

mRNA from the adult rat NG and brain was isolated using the microPoly (A+) Pure Kit (Ambion). Poly-(A+) mRNA was quantitated by spectrophotometric absorbance at 260 nm and stored at −80°C until use. Primers used to amplify the cDNA fragment corresponding to a region of the rat Kv1.3 gene (Accession No. RATRGK5) by RT-PCR were as follows: sense 5′-AGGACGTGTTTGAGGCTGCCAACAAC-3′ (695–721 bp) and antisense 5′-CCTCTTCGATCACCATATACTCCGAC-3′ (1,487–1,463 bp). RT-PCR was performed as previously described (Glazebrook et al. 2002). Channel-specific PCR products were identified by hybridization using a radiolabeled internal oligonucleotide specific for the Kv1.3 channel. The internal oligonucleotide was 5′-GACAACTGTCGGTTATGGTGATATGC-3′ (nucleotides 1,209–1,235). Southern blots were performed as previously described (Glazebrook et al. 2002; Doan et al. 2004).

Western blot analysis.

Rat pups were anesthetized in a saturated CO2 chamber before the collection of the ganglia. NGs from 10 newborn (postnatal day 1) rats were pooled and frozen at −80°C. Adult rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and decapitated. NGs were isolated, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C. The experiment was repeated in two separate groups of animals. Frozen NGs were homogenized in RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl, and 2.5 mM EDTA) complemented with protease inhibitors (Complete, mini-EDTA-free tablets, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitors (sets I and II, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Samples were incubated on ice for 2 h and then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured by the BCA method (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein were separated on 4–20% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Western blot analyses were performed as previously described (Kline et al. 2007). Anti-Kv1.3 (1:500, rabbit polyclonal, Alomone) and anti-actin (1:2,000) primary antibodies were used for the immunoblot analysis.

Immunocytochemistry.

Adult rats were deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and decapitated. The NG, medulla, and aortic depressor nerve (ADN) were isolated, quick frozen, and cryosectioned. Serial sections of the NG, ADN, and medulla (8 μm thick) were collected on glass slides and fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Sections were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA, 10% normal donkey serum, and 0.3% Triton X-100 for at least 30 min followed by an incubation in the presence of primary antibody for 3 h at room temperature. Slides were rinsed in PBS, and secondary antibodies were added for 90 min. Control sections were incubated with PBS and the appropriate secondary antibodies. Sections were rinsed, mounted in Vectashield (Vector laboratories) with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and acquired using a Nikon E600 microscope and a Spot camera or a Leica TCS confocal microscope. Anti-Kv1.3-labeled neurons were counted in one entire ganglion sectioned at 8 μm. DAPI-labeled nuclei used to identify neurons in each section were followed in adjacent sections to minimize double counting of cells. DAPI staining of neuronal nuclei was distinct from glial cell nuclei based on intensity and shape. Metamorph (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was used for the analysis of Kv1.3 immunoreactivity and measuring NG soma. Sections from an additional ganglion were colabeled with anti-Kv1.3 and anti-MBP antibodies. Horizontal NTS sections (8 μm) containing the solitary tract and the medial NTS from four animals were examined for colabeling of Kv1.3 and vesicular glutamate transporter 2 using confocal microscopy. ADN sections were labeled for Kv1.3 and MBP. For all immunohistochemistry, photomicrographs were imported into Photoshop and only adjusted for brightness and contrast for clarity.

Electrophysiology.

Adult rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and decapitated. The ganglia were dissected and placed in cold nodose complete media, which consisted of DMEM-F-12, 5% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), and 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The ganglia were subsequently treated in a 37°C solution of Earl's balanced salt solution containing 0.1% collagenase type 2 (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) for 70 min. After incubation, the enzyme solution was discarded, and 1.5 ml of nodose complete medium plus 0.15% BSA (Sigma) were added to the tissue and manually dissociated with a fire-bored Pasteur pipette. Cells were plated on poly-l-lysine (0.5 mg/ml aqueous solution)-coated coverslips for electrophysiology experiments. To isolate K+ currents from Na+ and Ca2+ currents, cultured neurons (24–72 h) were superfused with extracellular solution containing (in mM) 140 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG), 5.4 KCl, 0.3 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES. Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were performed with glass electrodes of 2- to 5-MΩ resistance filled with (in mM) 145 K-aspartate, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose, 0.3 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, and 2.2 EGTA (pH adjusted to 7.1). For recordings of somatic action potentials, the extracellular solution consisted of (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 2.0 CaCl2, 10.0 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4) and the pipette solution consisted of 145 K-aspartate, 10 HEPES, 0.3 CaCl2, and 2.2 EGTA (pH 7.1). Only cells with a resting membrane potential more negative than −50 mV were included for study. All experiments were performed at room temperature. At the end of each experiment, neurons were tested for the presence of TTX-resistant Na+ current in a voltage-clamp protocol consisting of a series of 10-mV depolarizing voltage steps from −40 to +10 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. TTX (1 μM) was added to the extracellular solution with Ca2+ removed to eliminate interference from Ca2+ currents. MgTx (Alomone), a 39-amino acid peptide toxin blocker of Kv1.3 originally isolated from the venom of the scorpion Centruroides margaritatus (Garcia-Calvos et al. 1993; Knaus et al. 1995), was used in the range of 50–1,000 pM. We selected 500 pM for full block based on the concentration-response curve in the original study by Garcia-Calvo et al. (1993) and Rb+ flux studies in HEK or CHO cells transfected with Kv1.3 reporting IC50 values of 230 and 110 pM, respectively (Koschak et al. 1998; Helms et al. 1997). To confirm the specificity of MgTx for Kv1.3 in NG neurons, DTx (10 nM) was added to the bathing solution in a subset of experiments to block Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.6 also present in these neurons followed by 500 pM MgTx. Membrane current and voltage were recorded using a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch-200B, Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA), digitized online (10 kHz) with an analog-to-digital interface (DigiData 1200, Axon Instruments), and filtered at 1.0 kHz. Data were analyzed using pCLAMP (version 8.0, Axon instruments).

Brain stem NTS slices.

Brain stem NTS slices were prepared from animals anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and decapitated. The brain stem was removed and placed in ice-cold low-Ca2+/high-Mg2+ artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) containing the following (in mM): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 d-glucose, 0.4 l-ascorbic acid, 2 MgCl2, and 1 CaCl2 saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.4, 300 mosM). Horizontal slices (∼290 μm) were cut with a vibrating microtome (Leica VT 1000S). The submerged sections were secured with a nylon mesh and superfused at a flow rate of 3–4 ml/min with standard recording aCSF [containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 d-glucose, 0.4 l-ascorbic acid, and 2 CaCl2 saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.4, 300 mosM)] at 31–33°C. NTS neurons were visualized using an Olympus BX-51WI microscope (×40 magnification) equipped with differential interface contrast and an infrared-sensitive camera. The pipette was guided using a piezoelectric micromanipulator (PCS-6000, Burleigh, Victor, NY). Recording electrodes (3.5–5.0 MΩ, 8250 glass, King Precision Glass, Claremont, CA) were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 10 NaCl, 130 K+-gluconate, 11 EGTA, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, and 0.2 NaGTP (pH 7.3, 295–300 mosM). Recordings were made from cells in the medial and commissural NTS medial to the solitary tract (TS). Cells with holding currents greater than −50 pA and a resting membrane potential less than −50 mV upon initial membrane rupture were not considered for further analysis. Sensory afferent evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were generated by placing a concentric bipolar stimulating electrode (200-μm outer diameter, 50-μm inner diameter, FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) on the TS containing chemosensory and other visceral afferents (Andresen and Kunze 1994) and stimulating with a negative current pulse (0.01–0.3 mA, 0.1-ms duration) with an isolated programmable stimulator (AMPI, Jerusalem, Israel). Recordings were made in voltage-clamp mode while the TS was stimulated at 20 Hz. MgTx (20 nM) was dissolved in aCSF and perfused for 7 min after 5 min of stable baseline recording. The MgTx concentration for brain slice experiments was based on previous studies (Greffrath et al. 1998; Southan and Robertson 1998; McKay et al. 2005; Casassus et al. 2005; Korngreen et al. 2005; Nakamura and Takahashi 2007). Data were recorded using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier, filtered at 2 kHz, and sampled at 10 kHz using pCLAMP (version 10, Axon Instruments).

Data analysis.

Second-order NTS neurons were identified by jitter analysis, defined as the SD of the latency (Doyle and Andresen 2001). Neurons with jitter values of <250 μs were considered to be monosynaptic and directly connected to sensory TS neurons. In protocols involving a 20-Hz stimulus train, the percentage of synaptic depression in evoked current from the first event was determined. EPSC data points for a given trial were an average of five to eight EPSC sweeps at 20 Hz. Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaStat (version 3.5, Systat Software, San Jose, CA) or Origin software (Origin Labs). All data are presented as means ± SE. Electrophysiological data were compared by Student's t-test and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Cumulative probability plots of spontaneous EPSCs were compared by a Kolmogorov-Smirov two-sample test (SPSS).

RESULTS

Kv1.3 is expressed in the NG.

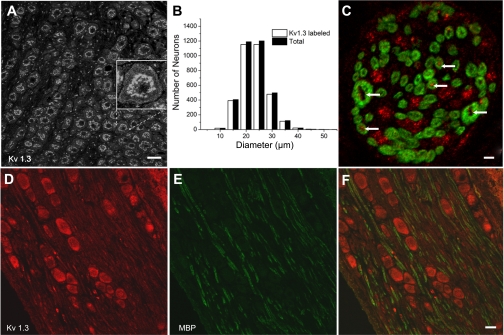

We examined the NG for the presence of the Kv1.3 channel. cDNA of the expected size, 792 bp, was amplified in samples of poly-(A+)-RNA isolated from the nodose and brain. Samples run in parallel without reverse transcriptase gave no amplification (Fig. 1A). Western blots confirmed the protein expression of Kv1.3 in the NG. The anti-Kv1.3 antibody (Alomone) recognized a prominent band with the apparent molecular mass of ∼65 kDa in both postnatal day 1 and 36 tissue (Fig. 1B). We next explored the distribution of the Kv1.3 α-subunit in the soma of the NG. Kv1.3 immunostaining of the NG was present throughout the neuronal population and strongly labeled internal organelles (Fig. 2A). Immunoreactivity was weaker at/near the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A, inset). Ninety-six percent of the neurons (3,339/3,475) counted in one ganglion were labeled with anti-Kv1.3. Small, medium, and large neurons labeled with anti-Kv1.3 (Fig. 2B). Myelinated axons within the ganglion identified with anti-MBP colabeled with anti-Kv1.3 (Fig. 2, D–F). Axons lightly labeled with anti-Kv1.3 but unlabeled with anti-MBP can also be seen in this image coursing parallel to the myelinated fibers. In cross sections of the ADN afferent sensory nerve with soma in the NG, Kv1.3 was identified in MBP-immunoreactive axons as well as clusters of presumed MBP-immunonegative axons (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of Kv1.3 in the NG and aortic depressor nerve (ADN). A: anti-Kv1.3 (Neuromab) immunolabeling in postnatal day 30 Spraque-Dawley rat nodose slices. The image is a mass z-projection of five confocal sections acquired at 0.69-μm intervals. Calibration bar = 30 μm. The inset shows a zoomed image to illustrate weaker labeling near/at the membrane. B: histograms showing the broad distribution of anti-Kv1.3 labeling with the respective neuron diameter compared with the distribution of diameters in the total population. C: section of the ADN colabeled with anti-Kv1.3 (Alomone; red) and anti-myelin basic protein (MBP; green) to illustrate the presence of Kv1.3 in myelinated axons. Arrows indicate examples of the anti-Kv1.3 label. These results were obtained in the ADN from two animals. Note the presence of only two large-diameter axons. Similar results (2–3 large axons with diameters > 2 μm) were obtained in five other ADNs. Scale bar = 2 μm. D and E: images of 8-μm nodose sections colabeled with anti-Kv1.3 (red; D) and anti-MBP (green; E). The overlay (F) shows the presence of Kv1.3 antibody in myelinated and unmyelinated axons in the ganglion. Scale bar = 20 μm.

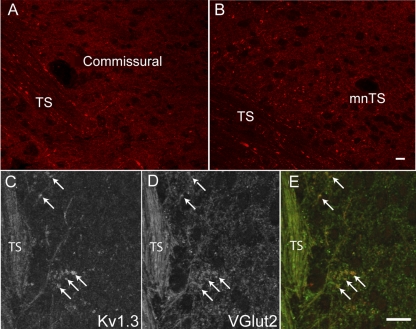

Kv1.3 immunoreactivity is present in the presynaptic terminals in the NTS.

Primary afferent fibers from visceral sensory fibers enter the brain stem NTS as part of the TS and, after exiting the tract, form a synapse with cells in this nucleus. We obtained Kv1.3 immunostaining within the tract and in the medial and commissural nuclei regions of the NTS where afferents from arterial baroreceptors and chemoreceptors terminate (Fig. 3, A and B). Much of this was punctate labeling surrounding the neurons close to the tract. To demonstrate localization to presynaptic terminals, the NTS region was labeled with both anti-Kv1.3 and anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 2, the primary glutamate vesicular transporter in the NTS (Lachamp et al. 2006) (Fig. 3, C–E). Colabeling was observed in structures of ∼2 μm in diameter, consistent with our previously reported size of presynaptic terminals on NTS soma (Drewe et al. 1988). Anti-Kv1.3 immunoreactivity was not present in neuron cell bodies in the region near the tract.

Fig. 3.

Confocal images of the NTS labeled with Kv1.3. A: confocal image of a horizontal NTS section in the commissural region. Fine fibers in the solitary tract (TS) exit the tract and innervate neurons medial to the tract. B: confocal image of a horizontal section of the NTS showing the medial nucleus of the NTS (mNTS), the site of termination of baroreceptor axons. Immunostaining of both sections with anti-Kv1.3 antibodies (red) showed the presence of the protein in the fibers in the tract and in the neuropile but not in cell bodies. Images are stacks of 12–15 z-sections taken at 0.3-μm intervals. Scale bars = 15 μm. C–E: confocal images of anti-Kv1.3 and anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2) in the TS and medial NTS. C: anti-Kv1.3 was present in the afferent sensory fiber tract (TS) and in discrete bouton-like structures (arrows). D: vGlut2 immunoreactivity was present in the same structures. E: merged image of Kv1.3 (red) and vGlut2 (green). Each image is a stack of four z-sections. Scale bars = 20 μm. Similar anti-Kv1.3 labeling was obtained in the NTS from four other animals.

MgTx blocks a component of the somal outward K+ current.

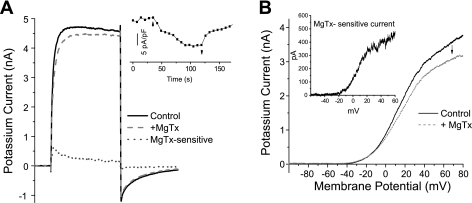

We next asked whether Kv1.3 is expressed in the surface membrane of the NG soma using a functional assay. We isolated whole cell K+ currents from Na+ and Ca2+ currents by replacing Na+ in the external solution with equimolar NMDG+ and reducing extracellular Ca2+ to 0.03 mM. In initial experiments, a depolarizing voltage step to +40 mV was applied at 20- to 30-s intervals from a holding potential of −80 mV. When the outward K+ current was stable for at least 2 min, 500 pM MgTx was added to the bath solution to block Kv1.3 (Garcia-Calvo et al. 1993; Helms et al. 1997) (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4, MgTx blocked a portion of the whole cell K+ current. In eight of eight neurons, the current decreased: 14.0 ± 3.8 pA/pF (range: 3–33 pA/pF) at the peak and 8.4 ± 2.2 pA/pF (range: 4–21 pA/pF) at the end of the 100- to 150-ms step. The former corresponded to 10.1 ± 1.8% and the latter to 5.6 ± 1.1% of the total K+ current at those time points. The inset shows the time course of the MgTx block. Increasing the concentration of MgTx to 1.0 nM had no further effect (n = 3). In a second set of experiments, a 900-ms ramp stimulus delivered every 30 s from −100 to +80 mV was used to obtain a current-voltage relationship, which showed the MgTx-sensitive current activated more positive than −30 mV (Fig. 4B). Under current clamp, we observed no effect on the resting membrane potential upon the addition of MgTx (0.5–1 nM) (control: −62.0 ± 1.7 mV vs. MgTx: −61.8 ± 1.6 mV, n = 23, P > 0.3, paired t-test), consistent with the lack of MgTx block under voltage clamp at potentials in this voltage range.

Fig. 4.

Margatoxin (MgTx) produces a partial block of total K+ current in the soma of nodose neurons A: example of total outward K+ current recorded from a neuron depolarized for 100 ms from −80 to +40 mV every 20 s. When control traces (solid black line) were stable for at least 2 min, 500 pM MgTx was applied and the current was decreased to the value shown (dashed red line). The difference (MgTx-sensitive) current is shown as a dotted blue line. The inset show the time course of the MgTx block (↑) and recovery (↓) in another neuron. B: 900-ms ramp stimulus applied to another nodose neuron in the absence of MgTx followed by the application of 500 pM MgTx (↓). The subtracted MgTx-sensitive current activated more positive than −30 mV (inset).

MgTx alters action potential duration in C-type but not A-type neurons.

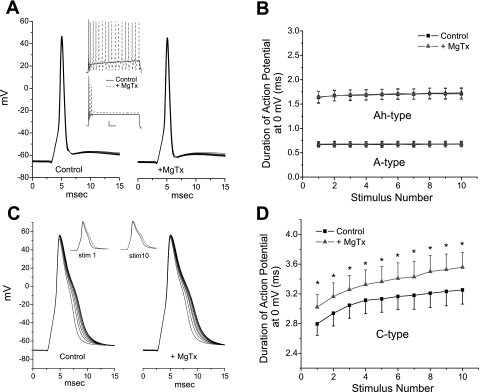

Somal recordings are used to gain insight into function in regions that are less accessible, such as the central presynaptic terminal. In the present study, we focused on the contribution of Kv1.3 to action potential duration under current-clamp conditions as an indicator of a potential role in central transmitter release. The natural stimulus received by sensory neurons from their peripheral terminals is a series of action potentials whose frequency is dependent on stimulus intensity at the peripheral receptor terminal. Thus, an appropriate stimulus to evaluate the role of Kv1.3 is a short-duration stimulus designed to elicit single action potentials. Neurons were stimulated at 0.5 Hz (0.35–1.5 ms) in current-clamp mode. When MgTx was applied to the rare cells subsequently shown to express only TTX-sensitive Na+ current (A-type neurons) (Stansfeld and Wallis 1985; Schild and Kunze 1997; Li and Schild 2007b), there was no change in the duration of the action potential measured at 0 mV (0.74 ± 0.09 vs. 0.76 ± 0.1 ms, n = 3, P > 0.4, paired t-test). In addition, in three neurons, there were no changes in the duration of the action potential in response to 20-Hz repetitive stimulation either in the control solution or in the presence of MgTx (Fig. 5, A and B). To verify that Kv1.3 was, however, functionally expressed in these neurons, we applied a longer-duration constant current depolarizing stimulus (150 or 400 ms) at a threshold level for eliciting at least one action potential. Application of MgTx either increased the number of action potentials in response to the stimulus (2 of 3 neurons; Fig. 5A, top inset) and/or increased the amount of depolarization produced by the current injection (1 of 3 neurons; Fig. 5A, bottom inset), with the latter indicative of a decrease in membrane conductance upon block of Kv1.3.

Fig. 5.

Effects of MgTx on neuronal discharge. A: example of an A-type neuron (Na+ current blocked by TTX) responding to 10 brief (0.35–1.5 ms) stimuli delivered at 20 Hz. There was no change in the duration of the action potential with frequency, nor did MgTx (1 nM) have an effect on duration. However, a longer-duration stimulus (top inset) increased discharge from one action potential in the control solution (solid black line) to repetitive firing in the presence of MgTx (dashed red line) or increased the amplitude of the depolarization to the constant current stimulus (bottom inset). Scale bars in insets = 50 ms, 10 mV. B: mean duration of the action potential at 0 mV plotted for 3 A-type neurons for each of the 10 stimuli in control solution and in the presence of MgTx. A group of six Ah-type neurons also did not respond MgTx. C: MgTx broadened the C-type action potential but did not eliminate the stimulation-dependent lengthening of the action potential (20-Hz stimulation), as shown in control solution and in the presence of 1.0 nM MgTx. Left inset, the first action potential in the 20-Hz train in the control solution (black) compared with the first action potential in the presence of MgTx (red); right inset, the 10th (last) action potential of the series without (black) and with (red) MgTx. D: mean duration of the action potential of eight C-types neurons in the absence and presence of MgTx plotted for each of the 10 stimuli. Four of these neurons had been previously incubated in α-dendrotoxin to eliminate any effect of MgTx on Kv1.1, Kv1.2, or Kv1.6. *P < 0.05 (paired t-test).

A second group of neurons (n = 6) with intermediate-duration action potentials did not respond to MgTx (action potential duration: 1.64 ± 0.12 vs. 1.65 ± 0.11 ms in MgTx, n = 6, P > 0.05) when stimulated at 0.5 Hz and showed no change in duration at 20 Hz (P > 0.05, paired t-test; Fig. 5B). The Na+ current in this group was incompletely blocked by TTX. We considered these to represent the Ah class of neurons with more slowly conducting myelinated fibers and an action potential duration of >1.0 ms, as described by Stansfeld and Wallis (1985) and, more recently, by Li et al. (2007b). As with the previous group, these Ah-type neurons responded to MgTx during a sustained depolarization with an increase in the number of action potentials to the current injection (4 of 7 cells) or a larger depolarization (3 of 7 cells, range: 2–5 mV).

The last group of NG neurons, C-type neurons, have broader initial action potentials (>2.0 ms) and express TTX-resistant current. These C-type responded to MgTx with an increase in the duration of the action potential from 2.19 ± 0.24 to 2.31 ± 0.23 ms at 0 mV (n = 13, P < 0.01, paired t-test) in response to a 0.5-Hz stimulus. This group was also subjected to a 20-Hz stimulation protocol in the absence and presence of MgTx (Fig. 5, C and D). MgTx has shown a high selectivity for Kv1.3 over other K+ channels, such as Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Leonard et al. 1992) and Kv3.1, Kv1.5, and IsK channels (Calvo-Garcia et al. 1993). The latter group reported has a weak effect on Kv1.6. Comparable studies have not been done for Kv1.1 and Kv1.2, which are both present in nodose neurons (Glazebrook et al. 2002). Thus, before the addition of MgTx, four C-type neurons were incubated with DTx (50 nM) to block Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.6 currents. While this increased the duration of their action potentials, as expected (Glazebrook et al. 2002), all four neurons subsequently responded to MgTx with a further increase in action potential duration and are included in the grouped 20-Hz data (Fig. 5D). The MgTx effect was superimposed on an increase in action potential duration in response to 20-Hz repetitive stimuli (Fig. 5, C and D), a characteristic of C-type neurons, as previously reported by Li and Schild (2007a).

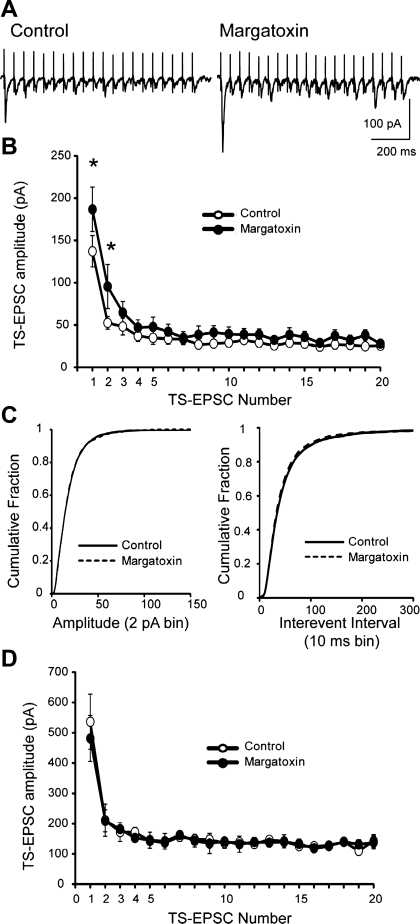

MgTx augments synaptic transmission in the NTS.

We asked whether the inhibition of Kv1.3 by MgTx observed in sensory afferents alters central neurotransmitter release in NTS brain slices. We recorded EPSCs from 18 NTS neurons in the medial and commissural NTS within the region of Kv1.3 immunoreactivity. EPSC synaptic latency was 3.7 ± 0.4 ms, and its SD (i.e., jitter) was 135 ± 14 μs, suggesting that EPSCs were generated from a monosynaptic connection (Doyle and Andresen 2001). Overall, the initial event of a 20-Hz EPSC train in the control solution ranged from 48 to 681 pA, with 15 of 18 cells exhibiting amplitudes of <300 pA (average: 137 ± 19 pA) with the remainder of cells averaging 536 ± 91 pA (3 of 18 cells, P < 0.05 vs. smaller events). The neurons with smaller EPSCs exhibited sensitivity to MgTx compared with those that exhibited larger initial EPSCs. A representative example of a MgTx-sensitive NTS cell is shown in Fig. 6A. In this cell, MgTx increased the amplitude of TS-evoked EPSCs that were elicited at 20 Hz. Mean data for the group of 15 smaller event, MgTx-sensitive cells is shown in Fig. 6B. Bath application of MgTx (20 nM, 6–7 min) increased the amplitude of the initial TS-evoked EPSCs. The amplitude of the first EPSC averaged 137 ± 19 pA in control recordings and increased to 187 ± 26 pA in MgTx (P = 0.016, paired t-test). Across the TS-EPSC event train, the MgTx-sensitive TS-EPSC amplitude was significantly greater at the beginning of the train and reduced at the end (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA; Fig. 6B). Spontaneous EPSCs in these 15 smaller event, MgTx-sensitive cells were also evaluated. Cumulative probability plots of spontaneous EPSC amplitudes and interevent intervals were generated to analyze distribution. MgTx did not alter the amplitude of spontaneous events (P = 0.295, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Fig. 6C, left) but did reduce the interevent interval, indicating a small increase in event frequency (P = 0.02, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Fig. 6C, right). The second group of larger EPSC amplitude monosynaptic neurons did not respond to MgTx (Fig. 6D). Note that the amplitudes of TS-EPSCs that were sensitive to MgTx were significantly smaller across the stimulus train than MgTx-insensitive NTS neurons (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA).

Fig. 6.

MgTx augments TS-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). A: representative tracings of TS evoked EPSCs that were recorded under control conditions (in artficial cerebrospinal fluid) and after MgTx (20 nM). The TS was stimulated at 20 Hz. Note the increase in the TS-EPSC amplitude, especially the first event. Shown is an average of five current sweeps. B: synaptic events were grouped according to their initial current amplitude. Data shown are the mean TS-EPSC amplitudes for 20 events whose initial amplitudes were <300 pA during control and MgTx application. n = 15. *P < 0.05 (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). MgTx elevated EPSCs primarily at the beginning of the stimulus train. C: spontaneous EPSC frequency was also elevated in MgTx-sensitive currents. The cumulative probability of sEPSC amplitude distribution (2-pA bin, left) was not altered in MgTx. On the other hand, the cumulative fraction of spontaneous EPSC interevent intervals (10-ms bin) illustrated a small leftward shift in the presence of MgTx (right). The analysis was performed on the entire sample of events. D: mean TS-EPSC amplitude for 20 events during control and MgTx application for three cells whose initial TS-EPSCs were >300 pA and did not respond to MgTx application. Note that the amplitudes of the EPSCs that were sensitive to MgTx (B) were significantly smaller than those of MgTx-insensitive NTS neurons.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show a functional role for Kv1.3 at the first synapse in visceral afferent pathways in the NTS. Our results support a role for Kv1.3 modulating transmitter release from presynaptic terminals of C-fibers through effects on the duration of the action potential.

Kv1.3 as a presynaptic modulator of transmitter release.

Consistent with reports of an axonal distribution for Kv1.3 (Veh et al. 2005; Rivera et al. 2005), we found immunoreactivity in the central axonal branches in the tract extending to presynaptic terminals. Localization of anti-Kv1.3 with vesicular glutamate transporter 2 along with the fact that Kv1.3 immunoreactivity was not present in NTS neurons in this region supports a presynaptic site for the actions of MgTx. Presynaptic localization has also been reported recently in the calyx of Held (Gazula et al. 2010).

Kv1.3 modulates transmitter release at presynaptic terminals.

We assessed the role of Kv1.3 at the central terminals by monitoring EPSCs in second-order NTS neurons in the medial and commissural NTS receiving monosynaptic sensory input. In response to tract stimulation, the EPSC amplitude was increased in the presence of MgTx in a subset of neurons. Extrapolating from our data in the nodose soma, where the C-fiber population (but not A- or Ah-type neurons) responds to MgTx with an increase in the duration of the action potential, we propose that the responding NTS neurons are innervated by C-type fibers and that the increase in the duration of the presynaptic action potential in the presence of MgTx augments transmitter release, leading to an increased amplitude of the synaptic potential (Wheeler et al. 1996; Raffaelli et al. 2004; Stephens and Mochida 2005). A role for Kv1.3 in transmitter release has been reported in other neuronal studies (Ohno-Shosaku et al. 1996; Shoudai et al. 2007; Doczi et al. 2008). Our data suggest that Kv1.3 in presynaptic terminals, presumably from C-type fibers, plays a significant role in modulating neurotransmitter release at the NTS.

A second group of EPSCs in NTS neurons was not altered by MgTx. This is consistent with innervation by fibers from A- and Ah-type neurons with short duration action potentials, where Kv1.3 would not play a role unless there were sustained depolarization of the terminal. We cannot rule out, however, the possibility that Kv1.3 is not present in the presynaptic terminals of the myelinated fibers, although it is present in their soma and axons. Interestingly, the evoked EPSCs that were not altered by MgTx were significantly larger in amplitude than those that were. Data from Andresen and Peters (2008) support the conclusion that the larger nonresponsive EPSCs in our study were present in neurons innervated by A- or Ah-type fibers. Those authors compared the peak amplitudes of capsaicin-resistant tract evoked EPSCs, presumably innervated by myelinated fibers, with capsaicin-sensitive EPSCs, innervated by C-type unmyelinated fibers. The former were 50% larger than the latter.

Frequency-dependent depression persists in the presence of MgTx.

Frequency dependent depression (FDD) is a hallmark characteristic of the NTS synapse, was first described by Miles (1986), and is readily demonstrated the results shown in Fig. 6. FDD has been proposed to result from a reduction in the availability of a readily releasable pool of vesicles at the presynaptic site (Schild et al. 1995), and it remains even in the presence of MgTx (Fig. 6). Superimposed on FDD is another factor that could potentially alter transmitter release during repetitive stimulation. This arises from the presence of presynaptic K+ channels that would limit action potential duration but that undergo cumulative inactivation in response to stimulation. These include the Kv1.3 channel (Cahalan et al. 1985; Maron and Levitan 1994, Grissmer et al. 1994), the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel KCNMA1 (Shao et al. 1999), and the Kv2.1 channel (Klemic et al. 1998), all channels that are present in the NG. One would expect that the broader action potentials toward the end of a stimulus train would lead to an increase in transmitter release. However, it appears that as FDD develops at the central synapse, it overrides the postulated effect of the broader action potentials that we observed during the 20-Hz stimulation in the soma of C-type neurons.

Physiological significance of presynaptic Kv1.3 in C-type axons.

At the presynaptic site in the NTS, most of the effect of Kv1.3 on transmitter release would occur early in a stimulus train before FDD develops. In our study, MgTx was most effective on the amplitude of the ESPC in response to the first stimuli in the 20-Hz series, where the hyperpolarizing effect of Kv1.3 is expected to play a stronger role at a time when competing FDD is still developing. Miles (1986) reported that the amplitude of the EPSC was reduced to 91% of its control value at a stimulation frequency of 1 Hz, to 63% at 5 Hz and 39% at 10 Hz. Thus, at low frequencies, there is minimum depression. This is important because the visceral sensory C-fiber population tends to fire at low frequencies (<1–5 Hz). For instance, C-fiber chemoreceptors generally fire from ≤ 2 to 4–5 Hz, although at very strong stimulation of their sensory terminals discharge can reach 20 Hz (Sato and Fidone 1969). The same study showed arterial baroreceptor C-fibers responded to a natural stimulus with only 1–2 spikes per arterial pressure pulse at a rate of 2–3 Hz, although under extreme stimulus conditions this can can reach 15–20 Hz. Other studies have confirmed these results (Coleridge et al. 1987; Seagard et al. 1990; Thoren et al. 1999).

Conclusions.

In summary, this is the first study to implicate a specific K+ channel, Kv1.3, in the evoked release of transmitter at second-order neurons receiving sensory input in the NTS. The data support the contention that Kv1.3 plays a role in limiting the duration of C-fiber action potentials, which is most effective during brief bursts of two to three action potentials with minimal cumulative inactivation and FDD, well within the range of the in vivo activity of C-fiber populations.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-090886 and HL-061436 (to D. L. Kunze) and HL-085108 (to D. D. Kline).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Agostoni et al., 1957. Agostoni E, Chinnock JE, DeBurgh Daly M, Murray JG. Functional, and histological studies of the vagus nerve and its branches to the heart, lungs and abdominal viscera in the cat. J Physiol 135: 182–205, 1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen and Kunze, 1994. Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Nucleus tractus solitarius–gateway to neural circulatory control. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 93–116, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen and Peters, 2008. Andresen MC, Peters JH. Comparison of baroreceptive to other afferent synaptic transmission to the medial solitary tract nucleus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2032–H2042, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte and Gallego, 1983. Belmonte C, Gallego R. Membrane properties of cat sensory neurones with chemoreceptor and baroreceptor endings. J Physiol 342: 603–614, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu and Feltz, 1984. Bossu JL, Feltz A. Patch-clamp study of the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium current in group C sensory neurones. Neurosci Lett 51: 241–246, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan et al., 1985. Cahalan MD, Chandy KG, DeCoursey TE, Gupta S. A voltage-gated potassium channel in human T lymphocytes. J Physiol 58: 197–237, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casassus et al., 2005. Casassus G, Blanchet C, Mulle C. Short-term regulation of information processing at the corticoaccumbens synapse. J Neurosci 25: 11504–11512, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge et al., 1987. Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC, Schultz HD. Characteristics of C fibre baroreceptors in the carotid sinus of dogs. J Physiol 394: 291–313, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan et al., 2004. Doan T, Stephans K, Glazebrook PA, Ramirez A, Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Differential distribution and function of hyperpolarization-activated channels (IH) in sensory neurons and mechanosensitive fibers. J Neurosci 24: 3335–343, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doczi et al., 2008. Doczi MA, Morielli AD, Damon DH. Kv1.3 Channels in postganglionic sympathetic neurons: expression, function, and modulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R733–R740, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle and Andresen, 2001. Doyle MW, Andresen MC. Reliability of monosynaptic sensory transmission in brain stem neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 85: 2213–2223, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewe et al., 1988. Drewe JA, Childs GV, Kunze DL. Synaptic innervation of isolated neurons from mNTS. Science 241: 1810–1813, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans and Murray, 1954. Evans DHL, Murray JG. Histological and functional studies on the fibre composition of the vagus nerve of the rabbit. J Anat 88: 320–337, 1954 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidone and Sato, 1969. Fidone SJ, Sato A. A study of chemoreceptor and baroreceptor A and C-fibres in the cat carotid nerve. J Physiol 205: 527–548, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Calvo et al., 1993. Garcia-Calvo M, Leanoard RJ, Novic J, Stevens SP, Schmalhofer W, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML. Purification, characterization, and biosynthesis of margatoxin, a component of Centruroides margaritatus venom that selectively inhibits voltage-dependent potassium channels. J Biol Chem 268: 18866–18874, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazula et al., 2010. Gazula VR, Strumbos JG, Mei X, Chen H, Rahner C, Kaczmarek LK. Localization of Kv1.3 channels in presynaptic terminals of brainstem auditory neurons. J Comp Neurol 518: 3205–2032, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook et al., 2002. Glazebrook PA, Ramirez AN, Schild JH, Shieh CC, Doan T, Wible BA, Kunze DL. Potassium channels Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.6 influence excitability of rat visceral sensory neurons. J Physiol 541: 467–482, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greffrath et al., 1998. Greffrath W, Martin E, Reuss S, Boehmer G. Components of after-hyperpolarization in magnocellular neurones of the rat supraoptic nucleus in vitro. J Physiol 513: 493–506, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer et al., 1994. Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol 45: 1227–1234, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms et al., 1997. Helms LM, Felix JP, Bugianesi RM, Garcia ML, Stevens S, Leonard RJ, Knaus HG, Koch R, Wanner SG, Kaczorowski GJ, Slaughter RS. Margatoxin binds to a homomultimer of Kv1.3 channels in Jurkat cells. Comparison with Kv1.3 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry 36: 3737–3744, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi and Nishi, 1982. Higashi H, Nishi S. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors of visceral primary afferent neurones on rabbit nodose ganglia. J Physiol 323: 543–567, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemic et al., 1998. Klemic KG, Shieh CC, Kirsch GE, Jones SW. Inactivation of Kv2.1 potassium channels. Biophys J 74: 1779–1789, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline et al., 2007. Kline DD, Rameriz-Navarro A, Kunze DL. Adaptive depression in synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract following in vivo chronic intermittent hypoxia: evidence for homeostatic plasticity. J Neurosci 27: 4663–4673, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus et al., 1995. Knaus HG, Koch RO, Eberhart A, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML, Slaughter RS. [125I]margatoxin, an extraordinarily high affinity ligand for voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. Biochemistry 34: 13627–13634, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korngreen et al., 2005. Korngreen A, Kaiser KM, Zilberter Y. Subthreshold inactivation of voltage-gated K+ channels modulates action potentials in neocortical bitufted interneurones from rats. J Physiol 562: 421–437, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschak et al., 1998. Koschak A, Bugianesi RM, Mitterdorfer J, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML, Knaus HG. Subunit composition of brain voltage-gated potassium channels determined by hongotoxin-1, a novel peptide derived from Centruroides limbatus venom. J Biol Chem 273: 2639–2644, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachamp et al., 2006. Lachamp P, Crest M, Kessler JP. Vesicular glutamate transporters type 1 and 2 expression in axon terminals of the rat nucleus of the solitary tract. Neuroscience 137: 73–81, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard et al., 1997. Leonard RJ, Knaus HG, Koch R, Wanner SG, Kaczorowski GJ, Slaughter RS. Margatoxin binds to a homomultimer of Kv1.3 channels in Jurkat cells. Comparison with Kv1.3 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry 36: 3737–3744 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al., 2007a. Li BY, Feng B, Tsu HY, Schild JH. Unmyelinated visceral afferents exhibit frequency dependent action potential broadening while myelinated visceral afferents do not. Neurosci Lett 421: 62–66, 2007a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li and Schild, 2007b. Li BY, Schild JH. Electrophysiological and pharmacological validation of vagal afferent fiber type of neurons enzymatically isolated from rat nodose ganglia. J Neurosci Methods 164: 75–85, 2007b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom and Levitan, 1994. Marom S, Levitan IB. State-dependent inactivation of the Kv3 potassium channel. Biophys J 67: 579–589, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay et al., 2005. McKay BE, Molineux ML, Mehaffey WH, Turner RW. Kv1 K+ channels control Purkinje cell output to facilitate postsynaptic rebound discharge in deep cerebellar neurons. J Neurosci 25: 1481–1492, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei et al., 1980. Mei N, Condamin M, Boyer A. The composition of the vagus nerve of the cat. Cell Tissue Res 209: 423–431, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, 1986. Miles R. Frequency dependence of synaptic transmission in nucleus of the solitary tract in vitro. J Neurophysiol 55: 1076–1090, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura and Takahashi, 2007. Nakamura Y, Takahashi T. Developmental changes in potassium currents at the rat calyx of Held presynaptic terminal. J Physiol 581: 1101–1112, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku et al., 1996. Ohno-Shosaku T, Kim I, Sawada S, Yamamoto C. Presence of the voltage-gated potassium channels sensitive to charybdotoxin in inhibitory presynaptic terminals of cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett 207: 195–198, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli et al., 2004. Raffaelli G, Saviane C, Mohajerani MH, Pedarzani P, Cherubini E. BK potassium channels control transmitter release at CA3-CA3 synapses in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol 557: 147–157, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera et al., 2005. Rivera JF, Chu PJ, Arnold DB. The T1 domain of Kv1.3 mediates intracellular targeting to axons. Eur J Neurosci 22: 1853–1862, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild and Kunze, 1997. Schild JH, Kunze DL. Experimental and modeling study of Na+ current heterogeneity in rat nodose neurons and its impact on neuronal discharge. J Neurophysiol 78: 3198–3209, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild et al., 1995. Schild JH, Clark JW, Canavier CC, Kunze DL, Andresen MC. Afferent synaptic drive of rat medial nucleus tractus solitarius neurons: dynamic simulation of graded vesicular mobilization, release, and non-NMDA receptor kinetics. J Neurophysiol 74: 1529–1548, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seagard et al., 1990. Seagard JL, van Brederode JF, Dean C, Hopp FA, Gallenberg LA, Kampine JP. Firing characteristics of single-fiber carotid sinus baroreceptors. Circ Res 66: 1499–1509, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao et al., 1999. Shao LR, Halvorsrud R, Borg-Graham L, Storm JF. The role of BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels in spike broadening during repetitive firing in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol 521: 135–146, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoudai et al., 2007. Shoudai K, Nonaka K, Maeda M, Wang ZM, Jeong HJ, Higashi H, Murayama N, Akaike N. Effects of various K+ channel blockers on spontaneous glycine release at rat spinal neurons. Brain Res 1157: 11–22, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan and Robertson, 1998. Southan AP, Robertson B. Modulation of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in mouse cerebellar Purkinje and basket cells by snake and scorpion toxin K+ channel blockers. Br J Pharmacol 125: 1375–1381, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld and Wallis, 1985. Stansfeld CE, Wallis DI. Properties of visceral primary afferent neurons in the nodose ganglion of the rabbit. J Neurophysiol 54: 245–260, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens and Mochida, 2005. Stephens GJ, Mochida S. G protein βγ-subunits mediate presynaptic inhibition of transmitter release from rat superior cervical ganglion neurones in culture. J Physiol 563: 765–776, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoren et al., 1999. Thoren P, Munch PA, Brown AM. Mechanisms for activation of aortic baroreceptor C-fibres in rabbits and rats. Acta Physiol Scand 166: 167–174, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki et al., 2004. Yamasaki M, Shimizu T, Miyake M, Miyamoto Y, Katsuda S, OIshi H, Nagayama T, Waki H, Katahira K, Wago H, Okouchi T, Nagaoka S, Mukai C. Effects of space flight on the histological characteristics of the aortic depressor nerve in the adult rat: electron microscopic analysis. Biol Sci Space 18: 45–51, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veh et al., 1995. Veh RW, Lichtinghagen R, Sewing S, Wunder F, Grumbach IM, Pongs O. Immunohistochemical localization of five members of the Kv1 channel subunits: contrasting subcellular locations and neuron-specific co-localizations in rat brain. Eur J Neurosci 7: 2189–2205, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villière and McLachlan, 1996. Villière V, McLachlan EM. Electrophysiological properties of neurons in intact rat dorsal root ganglia classified by conduction velocity and action potential duration. J Neurophys 76: 1924–1941, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler et al., 1996. Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Changes in action potential duration alter reliance of excitatory synaptic transmission on multiple types of Ca2+ channels in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 16: 2226–2237, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wladyka and Kunze, 2006. Wladyka CL, Kunze DL. KCNQ/M currents contribute to the resting membrane potential in rat nodose sensory neurons. J Physiol 575: 175–189, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]