Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine whether there were long-term (between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008) and recent (between 2001–2004 and 2005–2008) changes in blood pressure (BP) levels among U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Using data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), we examined changes in BP distributions, mean BPs, and proportion with BP <140/90 mmHg.

RESULTS

Between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008, for adults with diabetes, mean BPs decreased from 135/72 mmHg to 131/69 mmHg (P < 0.01) and the proportion with BP <140/90 mmHg increased from 64 to 69% (P = 0.01). Although hypertension prevalence increased, hypertension awareness, treatment, and control improved. However, there was no evidence of improvement for adults 20–44 years old. Between 2001–2004 and 2005–2008, there were no significant changes in BP levels.

CONCLUSIONS

BP levels among adults with diabetes improved between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008, but the progress stalled between 2001–2004 and 2005–2008. The lack of improvement among young adults is concerning.

Hypertension is particularly deleterious for people with diabetes because it confers 2 ∼3 times the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality as for people without diabetes (1,2). Studies demonstrated that blood pressure (BP) control is crucial to reduce vascular complications and improve survival for people with diabetes (3,4). The proportion of people with diabetes with poorly controlled BP declined considerably between the 1970s and the 1990s (5). However, in recent studies using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) data, no improvements in BP levels among adults with diabetes were observed from 1988–1994 to early 2000s (6) or from 1999 to 2006 (7). We updated prior studies with the most recent NHANES 2007–2008 data to examine long-term (between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008) and recent (between 2001–2004 and 2005–2008) changes in BP levels among U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We analyzed data from the NHANES 1988–1994 and 2001–2008. Our study included adults aged 20 years or older with self-reported diagnosed diabetes (regardless of hypertension status). We used an average of up to three BP readings to determine an individual’s BP level. After excluding people with missing BP values (n = 192), 3,255 people were included in final analysis.

Our outcome measures included BP distributions, mean systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP), and the proportion with SBP <140 and DBP <90 mmHg. To define categories for BP distributions, we adopted a method applied by Cheng et al. (8). Using combined NHANES 1988–1994 and 2001–2008 data, we first identified the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the BP distribution of the study population; next, we equally divided the BP values between the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles into nine intervals; we then conducted multiple categorical logistic regression to obtain the predicted percentage in each BP category for each study period adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg, or self-reporting of taking antihypertensive medications. Among those with hypertension, participants were considered aware of hypertension status if they answered that they had been told that they had hypertension; those who reported taking antihypertensive medications were considered under treatment, and those with SBP <140 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg were considered to have BP in control.

Data analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.3 and SUDAAN 9.0. Mean BPs, the proportion with BP <140/90 mmHg, and hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rate were age-adjusted to the NHANES 2005–2008 diabetic population. We used t tests to assess differences in means and rates between time periods. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

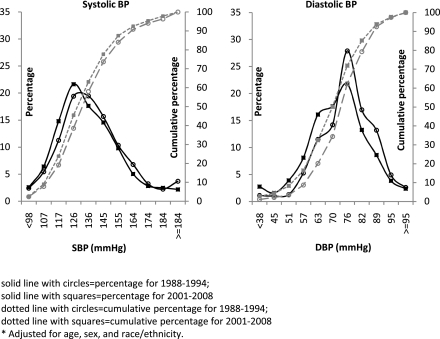

Figure 1 depicts shifts in both SBP and DBP distributions toward lower levels between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008. However, only a small percentage in either period had DBP ≥90 mmHg.

Figure 1.

Adjusted (*) BP distributions for U.S. adults with diabetes, 1988–1994 vs. 2001–2008.

Between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008, overall mean BPs decreased from 135/72 mmHg to 131/69 mmHg (P value < 0.01). Mean BPs decreased in all subgroups except for adults aged 20–44 years (Supplementary Table 1). The overall age-adjusted proportion with BP <140/90 mmHg increased from 63.8 to 69.2% (P = 0.01). The increase was significant for adults aged 45–64 years, women, non-Hispanic blacks, and Mexican Americans, but not for other subgroups.

Between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008, age-adjusted hypertension prevalence increased from 56.0 to 67.3% (P < 0.01) overall, but did not increase significantly among women, Mexican Americans, and adults aged 20–44 years (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, improvements were seen in age-adjusted hypertension awareness (84.1 to 92.3%), treatment (75.0 to 88.4%), and control (38.1 to 54.0%) (all P < 0.01). Adults aged 20–44 years experienced no significant increase in any of these measures, and Mexican Americans had no significant improvement in awareness of hypertension.

Between 2001–2004 and 2005–2008, there was no significant change for overall mean BP (SBP, 131.7 vs. 131.3 mmHg, P = 0.7; DBP, 68.3 vs. 68.9 mmHg, P = 0.6) and for the age-adjusted proportion with BP <140/90 mmHg (69.7 vs. 68.7%, P = 0.7) (Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, no significant changes were found for any subgroups analyzed. There were also no significant changes in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control for all groups except for hypertension prevalence increasing for young adults (P = 0.02) (Supplementary Table 4).

CONCLUSIONS

BP levels among U.S. adults with diabetes improved between 1988–1994 and 2001–2008. There was no evidence of any improvement among adults aged 20–44 years. Virtually all of the improvements were limited to the 1990s, and no significant improvements were seen in the 2000s.

The improvement in BP levels, in conjunction with prior reported improvement in A1C levels (9), may indicate encouraging trends in diabetes management. Indeed, despite upward hypertension prevalence, which may be driven in part by rising obesity (10), BP levels improved, indicating probably more effective hypertension management. During our study period, landmark clinical trials showed that BP control reduced vascular complications (3,4) and new clinical guidelines lowered BP targets to <130/80 mmHg (11,12). Awareness of the benefits of BP control may have increased and treatment intensified. Furthermore, the lowered BP target might have resulted in earlier diagnosis and treatment at lower BP levels, contributing not only to the observed increase in hypertension prevalence but also to increased awareness, treatment, and control rates.

The lack of improvement among young adults is concerning because of their future risk of developing vascular complications at younger ages. Several factors could explain the poor levels of control in younger patients, including a lower adherence to medications (13); a lower tendency to receive treatment intensification (14); and less optimal care for hypertension, i.e., delayed initiation of pharmacotherapy when lifestyle intervention fails (15).

Limitations of our study include the relative small sample sizes for young adults, which may limit our ability to detect small changes. BP measurement errors may also exist since BP was measured at a single occasion in the NHANES. However, the methods were consistent across all NHANES and BP levels were based on averaged readings.

Finally, we found that the progress in BP levels in the adult population with diabetes may have stalled in 2000s. Although hypertension awareness and treatment rates are now high (∼90%), hypertension prevalence remains high and control rates are suboptimal, indicating need for effective prevention and control strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

J.W. and L.S.G. researched data, contributed to discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y.J.C. researched data, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. G.I. and S.H.S. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.J. researched data. E.W.G. researched data, contributed to discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The authors thank Dr. Lawrence Barker of the Division of Diabetes Translation, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc11-0178/-/DC1.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. ; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies [retracted in Lancet 2010;376:958]. Lancet 2010;375:2215–2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care 1993;16:434–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. ; HOT Study Group Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998;351:1755–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner R, Holman R, Stratton I, et al. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998;317:703–713 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imperatore G, Cadwell BL, Geiss L, et al. Thirty-year trends in cardiovascular risk factor levels among US adults with diabetes: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1971-2000. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA 2004;291:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung BMY, Ong KL, Cherny SS, Sham PC, Tso AWK, Lam KSL. Diabetes prevalence and therapeutic target achievement in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Am J Med 2009;122:443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng YJ, Kahn HS, Gregg EW, Imperatore G, Geiss LS. Recent population changes in HbA(1c) and fasting insulin concentrations among US adults with preserved glucose homeostasis. Diabetologia 2010;53:1890–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoerger TJ, Segel JE, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB. Is glycemic control improving in U.S. adults? Diabetes Care 2008;31:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, Thom T, Fields LE, Roccella EJ. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Hypertension 2008;52:818–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. ; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes for patient with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2001;24(Suppl. 1):S33–S43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vawter L, Tong X, Gemilyan M, Yoon PW. Barriers to antihypertensive medication adherence among adults—United States, 2005. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:922–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subramanian U, Schmittdiel JA, Gavin N, et al. The association of patient age with cardiovascular disease risk factor treatment and control in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1049–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hiatt L, et al. Quality of care for hypertension in the United States. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2005;5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.