Abstract

Cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) is caused by haploinsufficiency in RUNX2 function. We have previously identified a series of RUNX2 mutations in Korean CCD patients, including a novel R131G missense mutation in the Runt-homology domain. Here, we examine the functional consequences of the RUNX2R131G mutation, which could potentially affect DNA binding, nuclear localization signal, and/or heterodimerization with core binding factor-β (CBF-β). Immunofluorescence microscopy and western blot analysis with subcellular fractions show that RUNX2R131G is localized in the nucleus. Immunoprecipitation analysis reveals that heterodimerization with CBF-β is retained. However, precipitation assays with biotinylated oligonucleotides and reporter gene assays with RUNX2 responsive promoters together reveal that DNA binding activity and consequently the trans-activation of potential of RUNX2R131G is abrogated. We conclude that loss of DNA binding, but not nuclear localization or CBF-β heterodimerization, causes RUNX2 haploinsufficiency in patients with the RUNX2R131G mutation. Retention of specific functions including nuclear localization and binding to CBF-β of the RUNX2R131G mutation may render the mutant protein an effective competitor that interferes with wild type function.

Keywords: RUNX2, RUNX2R131G, Core binding factor-β (CBF-β), Cledocranial dysplasia (CCD), subcellular localization, heterodimerization, DNA binding activity, Trans-activation

INTRODUCTION

Runt-related transcription factor RUNX2 (van Wijnen et al., 2004) controls normal bone formation by regulating growth and maturation of osteoblasts (Komori et al., 1997; Otto et al., 1997; Ducy et al., 1997; Banerjee et al., 1997; Choi et al., 2001; Pratap et al., 2003; Galindo et al., 2005; Young et al., 2007; Lou et al., 2009). RUNX2 has several functional domains, including the N-terminal runt-domain that is responsible for both DNA binding and heterodimerization with CBF-β (Bae S-C et al., 1994; Crute BE et al., 1996) and an immediately adjacent nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Kagoshima et al., 1993; Thirunavukkarasu et al., 1998). The C-terminus of RUNX2 contains a transactivation domain (Thirunavukkarasu et al., 1998; Yagi et al., 1999), a nuclear matrix targeting signal (Zaidi et al., 2001), and a VWRPY peptide that supports transcriptional repression (Javed et al., 2000), as well as interacting domains for a number of co-regulatory proteins that transduce cell signaling pathways and support activation of RUNX2 target genes (Lian et al., 2006). The C-terminal domain is essential for Runx2 function as evidenced by studies showing that loss of the Runx2 C-terminus causes complete loss of bone (Choi et al., 2001), a phenotype that is virtually indistinguishable from that of Runx2 null mice (Komori et al., 1997; Otto et al., 1997). Mutations in both the N-terminal DNA binding domain and C-terminal transcriptional regulatory domains have been linked to cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD; MIM 119600) indicating that RUNX2 is essential for early patterning and post-natal formation of the human skeleton (Mundlos et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1999: Zhang et al., 2000; Otto et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2006).

CCD is an autosomal dominant inherited human bone dysplasia that is characterized by absent or hypoplastic clavicles, persistently open or delayed closure of sutures, supernumerary teeth, and short stature (Lee et al., 1997; Mundlos et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2006). Although many RUNX2 mutations from CCD patients have been identified (Mundlos et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2000; Nagata et al., 2001; Tahirov et al., 2001; Otto et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2003; Puppin et al., 2005; Cunningham et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006; Matheny et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Ryoo et al., 2009), genotype-phenotype relationships and the molecular pathology of RUNX2 mutations that cause CCD have remained unclear. Rigorous functional studies are required with distinct CCD-related RUNX2 mutations to validate postulated pathological effects on the osteogenic activity of RUNX2. Furthermore, natural amino acid variations that yield skeletal phenotypes characteristic of human CCD represent clinically validated RUNX2 mutants that will enable structure-function analysis of its multiple molecular activities.

Previously, we characterized eleven CCD patients with characteristic dental and skeletal abnormalities that were linked to mutations in the coding sequence of the RUNX2 (Kim et al., 2006). Four novel mutations were identified including a splice donor site mutation (IVS1 + 1G>A) that produced an internal deletion of RUNX2 (RUNX2Δe1) resulting in partial loss of nuclear localization, as well as dysfunctions in DNA binding and trans-activation (Kim et al., 2006). In this study, we analyzed the functional consequences of a previously identified missense mutation of RUNX2 (RUNX2R131G) in the Runt domain. We show that this mutation abolishes sequence-specific DNA binding and transcriptional enhancement. However, RUNX2R131G retains nuclear localization and heterodimerization with CBF-β, suggesting that the CCD phenotype may result from competitive inhibition with wild type RUNX2 for CBF-β and other transcriptional co-regulators in chromatin-related subnuclear micro-environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

LipofectAMINE™, α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent was acquired from PIERCE Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, USA). Nitrocellulose membrane and ECL™ Western Blotting Detection Reagents were obtained from GE healthcare (Bucks, U.K.). Mouse IgG monoclonal antibodies for hemagglutinin (HA) (BAbCO, Richmond, CA, USA), Myc (Invitrogen), Lamin B1 (Santa Cruz, City, CA USA), β-actin, as well as anti-mouse IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 555 (Invitrogen), goat anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz), Protein G sepharose (Santa Cruz) and Streptavidin-conjugated agarose CL4B (Sigma, Springfield, Missouri, USA) were acquired from the indicated suppliers. A chemiluminescence assay kit was obtained from Tropix (Bedford, MA, USA).

Construction of HA-tagged RUNX2R131G

Amino acid substitution mutation of RUNX2R131G was generated by a two-step PCR approach (Kim HJ et al., 2006) using the forward primer 5′- GCC CTC GCA CTG GGG CTG CAA CAA GAC CCT GCC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′- CCG TCC CAG AAC AAC GTC GGG GTC ACG CTC CCG-3′. PCR products and the RUNX2R131G mutation were verified by sequencing using T7 promoter primer 5′- TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG-3′ and BGH reverse primer 5′- TAG AAG GCA CAG TCG AGG-3′.

Recombinant proteins were expressed using pcDNA3.1-HA-RUNX2, pcDNA3.1-HA-RUNX2R131G, and pCMV-Myc-Cbf-β vectors. For transactivation studies, pOC1050-Luciferase and pGL3-6XRUNX2-Luc reporter gene constructs were used as previously descrived (Kim HJ et al., 2006).

Cell culture and transient transfection

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100U/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. HeLa cells and HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100U/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin. For transient transfections, we seeded CHO, HeLa or HEK293T cells at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well of a 8-well-chamber slide or 4 × 105 cells a well of 6-well-culture plate. Plasmids were transfected using LipofectAMINE™ according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 3 h post-transfection, complete growth medium was added to each transfected well and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 18 h.

Western blot analysis

HeLa or HEK293T cells were seeded and transiently transfected with HA-RUNX2 or HA-RUNX2R131G expression vectors with LipofectAMINE™ as described above. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (PIERCE Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts (20 μg each) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Blocking of transferred nitrocellulose membrane was performed in 5% nonfat dried milk in TBS-T (1xTBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Membrane were incubated for 1 h at RT or overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-HA IgG (diluted 1:2000 in TBS-T), and then incubated for 1 h at RT with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodiy (diluted 1:4000 in TBS-T). The blot was developed with Amersham ECL™ reagent. Goat anti-Lamin B1 or mouse anti-β-actin antibodies were used as internal controls on the same membrane after deprobing of the membrane.

In situ immunofluorescence microscopy

HA-RUNX2 and HA-RUNX2R131G expression vectors were transfected into HeLa cells. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS and treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. After fixation of cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min, cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody to final concentration of 1: 100 for 1 h at RT. Cells were then washed with PBS three times and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 for 1 h at RT. Cover slides were mounted with Prolong® Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) after three rinses with PBS. Immunofluorescent signals were captured using a Nikon light microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Co-Immunoprecipitation analysis

HeLa or HEK293T cells were seeded and transiently transfected with HA-RUNX2 and Myc-Cbf-β or HA-RUNX2R131G and Myc-Cbf-β expression vectors. Protein G bead slurry was added to 200 μg of nuclear extracts and incubated at 4°C for 1 hr with rotation to eliminate non-specific binding protein. After spin down, supernatant was incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-HA IgG or mouse monoclonal anti-Myc IgG at 4°C for 1 hr with rotation. Newly prepared protein G bead slurry was added to the reacted supernatant and incubated at 4°C for overnight with rotation. After centrifugation, Protein G beads were rinsed four times using wash buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40). 6X SDS-sample loading buffer (30 μl) was added to washed protein G beads and samples were heated to 100°C for 5 min. Boiled samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blocking of transferred nitrocellulose membrane was performed in 5% nonfat dried milk in TBS-T for 1 h at RT, incubated for 1 h at RT. As above, blots were incubated for 1 h at RT or overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-HA IgG or anti-Myc IgG (diluted 1:2000 in TBS-T). Membranes were then incubated for 1 h at RT with the peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (diluted 1:3000 in TBS-T). The blot was developed with Amersham ECL™ Reagents. Antibodies for Lamin B1 or β-actin antibodies were used as internal controls on the same membrane after deprobing of the membrane.

DNA affinity protein-binding assay (DAPA)

HeLa or HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-HA-RUNX2 or pcDNA3.1-HA-RUNX2R131G expression vectors. Biotinylated wild type- or mutant RUNX2 binding site oligonucleotides (20 μg) corresponding to the −156/−112 segment of the mouse osteocalcin promoter (Kim et al., 2003) were added to 100 μg of nuclear extracts and incubated at RT for 1 hr with rotation. Streptavidin immobilized on agarose CL-4B slurry (50%, 30 μl) was added to binding reactions with nuclear extracts and oligonucleotides and the mixtures were incubated at RT for 1 hr with rotation and the beads were recovered by micro-centrifugation. After three rinses with cold PBS, 30 μl of 6X SDS-sample loading buffer was added to protein/DNA complexes attached to the sepharose CL-4B. Samples were boiled for 5 min, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blocking of transferred nitrocellulose membrane was performed in 5% nonfat dried milk in TBS-T for 1 h at RT, incubated for 1 h at RT or overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-HA IgG or mouse monoclonal anti-Runx2 serum (Pratap et al., 2003) (diluted 1:2000 in TBS-T), and then the membrane was incubated for 1 h at RT with the peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (diluted 1:3000 in TBS-T).

The RUNX2 binding site nucleotides sequences used in this study were as follows: Wild type RUNX2; Forward 5′-GAT CCG CTG CAA TCA CCA ACC ACA GCA-3′, Reverse 5′- GCG ACG TTA GTG GTT GGT GTC GTC TAG-3′; Mutant RUNX2; Forward 5′-GAT CCG CTG CAA TCA CCA AGA AC AGC A-3′, Reverse 5′-GCG ACG TTA GTG GTT CTT GT CGT CTA G-3′.

Promoter activity assay

HeLa Cells were transiently transfected with the pcDNA3.1-HA-RUNX2 or pcDNA3.1-HA-RUNX2R131G expression plasmids (0.5μg) plus either the osteocalcin gene pOC1050-Luciferase or pGL3-6XRUNX2-Luciferase reporters using LipofectAMINE PLUS reagent as previously described (Kim HJ et al., 2006). The pSV-βgal plasmid expressing β-galactosidase was also co-transfected as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase activity was measured using D-luciferin as substrate in luciferase reaction buffer (15 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 15 mM MgSO4, 25 mM glycine, 4 mM EGTA, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and normalized relative to β-galactosidase activity measured using a chemiluminescent assay kit (Tropix, Bedford, MA). Luminescence was measured by an AutoLumat LB953 instrument (EG&G Berthold, Walloc, Finland).

RESULTS

Nuclear localization of RUNX2R131G

The RUNX2R131G mutation, which converts arginine 131 to glycine due to a dC to dG basepair substitution at nucleotide 391, was previously identified in a 13-year-old female Korean CCD patient (Kim et al., 2006) with supernumerary teeth and open fontanelle (data not shown). The location of this mutation within the conserved Runt homology domain predicts that the RUNX2R131G mutation may affect one or more essential functions of RUNX2.

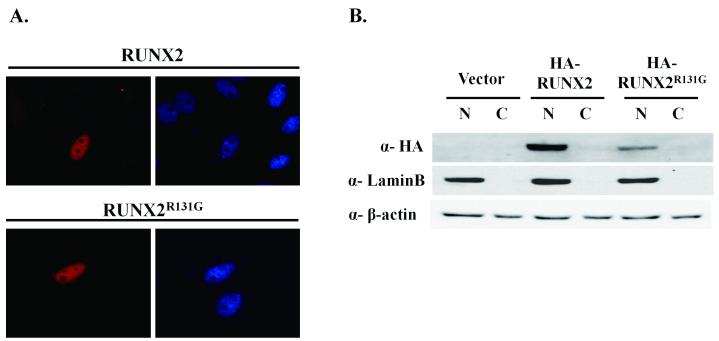

RUNX2 as well as RUNX1 and RUNX3 contain a NLS that is located immediately carboxyl-terminal to the runt domain (amino acids 218-234 in RUNX2) (Thirunavukkarasu et al., 1998). RUNX2 is localized in the nucleus and organized in subnuclear foci throughout the nucleus, as well as the peri-nucleolar region (Javed et al., 2000; Zaidi et al., 2001; Zaidi et al., 2004; Young et al., 2007). Some RUNX2 mutations cause CCD by perturbing nuclear localization (Quack et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1999; Otto et al., 2002; Sakai et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2003). Interestingly, the mutation in RUNX2R131G is localized in a putative nuclear localization signal (-HWRCNKTLP-) and a RUNX2 N-terminal deletion mutant RUNX2Δe1 is localized in the cytoplasm (Kim et al., 2006). To determine the localization of RUNX2R131G at the single cell level, we expressed an epitope tagged HA-RUNX2 wild type protein and the R131G mutant protein in HeLa, CHO or HEK293 cells (Fig. 1 and data not shown). The subcellular location of the two proteins was examined by in situ immunofluorescence microscopy and western blotting of subcellular fractions with HA- or RUNX2-antibody. The results show that both RUNX2R131G and wild type RUNX2 are localized in nuclei of HeLa cells (Fig. 1A), as well as CHO or HEK293 cells (data not shown). Biochemically, both RUNX2R131G and the wild type protein are predominantly present in the nuclear fraction (Figure 2B). Thus, the subcellular compartmentalization of RUNX2 in the nucleus is not perturbed by the CCD related mutation.

Figure 1. Subcellular localization of RUNX2 and RUNX2R131G.

HA tagged RUNX2 and RUNX2R131G plasmids were transiently transfected in HeLa cells and the expression of the encoded proteins was observed by immunofluorescence microscopy. In situ immunofluorescence staining was performed with Alexa Fluor 555 labeled primary HA antibody. The DAPI panel shows staining of nucleus in whole-cell preparations (A). Nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) extracts from CHO cells transfected with HA tagged RUNX2 or RUNX2R131G plasmid were used for western blot analysis with an HA antibody. Antibodies for Lamin B and β-actin were used as markers, for respectively, nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments, and internal loading controls (B).

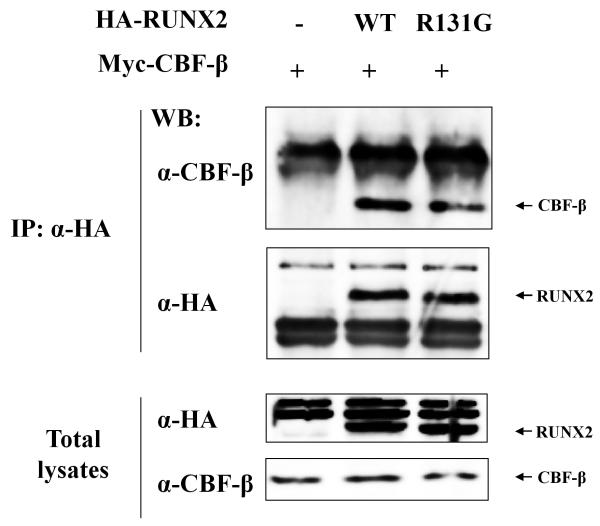

Figure 2. Heterodimerization of RUNX2R131G with CBF-β.

HA tagged RUNX2 or RUNX2R131G and Myc tagged CBF-β plasmid were co-transfected in HEK293 cells and proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to HA. Immunoprecipitated proteins or total lysates were separated in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred, and immunoblotted with antibodies to either CBF-β or HA. -: Mock Plasmid; WT: HA tagged Wild Type RUNX2 plasmid; R131G: HA tagged RUNX2R131G plasmid.

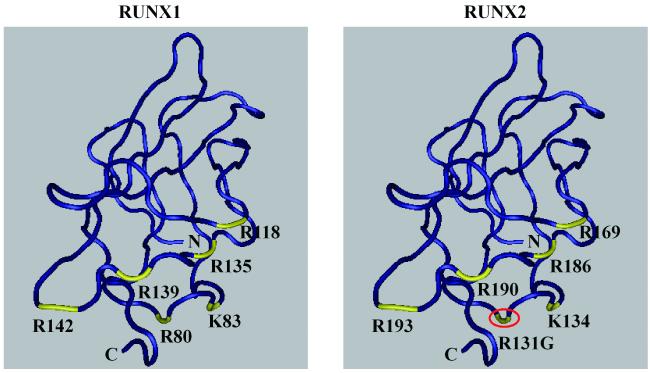

The RUNX2R131G mutant does not bind to the RUNX recognition motif but heterodimerizes with CBF-β

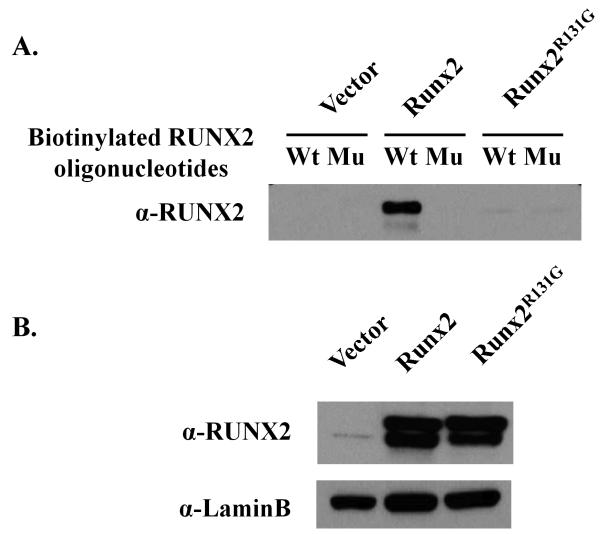

According to the three-dimensional structure of the runt domain, the R131G site is located in β3 strand which contacts the DNA at the consensus sequence 5′-TGTGGTT-3′ (Tahirov et al., 2001). This location is structurally analogous to the R80C mutation in RUNX1 that has been observed in one acute myelogenous leukemia patient (Osato et al., 1999). The RUNX1R80C mutant shows abrogation of DNA binding activity without affecting heterodimerization with CBF-β. Therefore, we performed immunoprecipitation analysis and DNA binding assays (DAPA) to assess whether the RUNX2R131G mutation affects either heterodimerization with CBF-β or binding to a RUNX binding consensus site in a target gene promoter. Immunoprecipitates with either wild type RUNX2 and RUNX2R131G but not samples obtained from untransfected control cells, clearly contain CBF-β (Figure 2). CBF-β was not detected in RUNX2 untransfected control cells. With respect to DNA binding activity, the wild type RUNX2 but not the RUNX2R131G mutant interact with the RUNX2 consensus binding site oligonucleotide in DAPA assays (Figure 3A), yet both proteins were each robustly expressed in the nucleus (Figure 3B). These results indicate that RUNX2R131G has the ability to heterodimerize with CBF-β, but is incapable of DNA binding to the RUNX consensus motif.

Figure 3. DNA binding activity of RUNX2 or RUNX2R131G.

HA tagged RUNX2 or RUNX2R131G proteins were expressed in HeLa cells. Nuclear extracts from transfected HeLa cells were incubated with biotinylated wild type (Wt) or mutant (Mu) RUNX2 binding oligonucleotides for 1h at RT. Streptavidin coated Sepharose CL4B beads were added to nuclear protein/DNA complexes and incubated at RT for 1 hr with rotation. Reacted (A) or non-reacted (B) nuclear extracts were separated in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred, and immunoblotted with antibodies to RUNX2. Lamin B antibody was used as internal loading control.

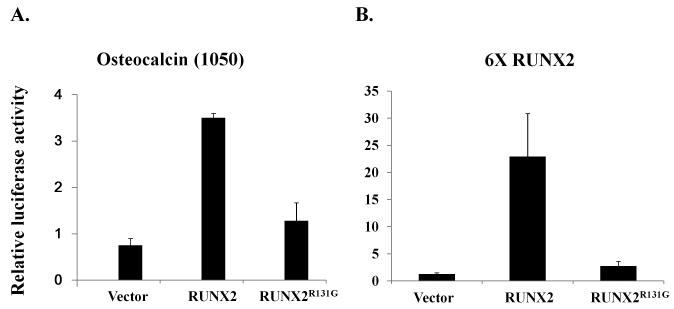

Transactivation of RUNX2R131G for target genes

The loss of DNA binding activity but retention of heterodimerization potential with CBF-β observed for the RUNX2R131G mutant predicts that the trans-activation function of RUNX2R131G on RUNX target gene promoters is abrogated. We tested this prediction using a natural promoter of the osteocalcin gene or a chimeric reporter with six tandemly linked RUNX2 sites (6XRUNX2 promoter; also referred to as 6XOSE reporter). In transient transfection assays, wild type RUNX2 increases promoter activity of the osteocalcin gene and 6XRUNX2 promoter (Figure 4). However, the RUNX2R131G mutant does not have trans-activation potential on either the osteocalcin or 6XRUNX2 promoters (Figure 4). These results demonstrate that the trans-activation function of RUNX2R131G is abrogated consistent with the defect in DNA binding activity.

Figure 4. Trans-activation of RUNX2 or RUNX2R131G.

HeLa cells were co-transfected with HA-RUNX2 or HA-RUNX2R131G and the osteocalcin gene promoter derived pOC1050-luciferase (A) or 6XRUNX2-luciferase (B) reporters. The pSV-βgal plasmid expressing β-galactosidase was also co-transfected as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Total lysates were extracted from transfected HeLa cells and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were assayed. Bars represent the average ratios of luciferase to β-galactosidase activity. The standard deviations obtained from three independent transfections of one representative experiment are represented by error bars. The values of relative luciferase activity represent the means ±S.D.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that loss of DNA binding activity is the primary molecular mechanism by which a novel RUNX2R131G mutation causes CCD, based on examination of the molecular and cellular properties of the mutant protein. Mutation of arginine 131 in RUNX2R131G is expected to perturb putative NLS within the Runt domain of RUNX2 (Kim HJ et al., 2006). However, our results show that the RUNX2R131G is not aberrantly localized in the cytoplasm, but rather shows normal nuclear localization of RUNX2R131G. Functional analysis of RUNX2R131G revealed that heterodimerization with CBF-β is not perturbed, but that DNA binding and trans-activation are abrogated in RUNX2R131G.

The Runt domain encodes the evolutionarily conserved protein structure that defines the RUNX family (Bae S-C et al., 1994; Tahirov et al., 2001). CCD mutations have clearly shown that natural amino acid substitutions in the Runt domain can affect sequence-specific DNA binding and /or heterodimerization with CBF-β and target DNA (Otto et al., 2002). Our observation that the RUNX2R131G mutant is capable of heterodimerizing with CBF-β in co-immunoprecipitation assays but does not bind the RUNX2 recognition motif is consistent with structural models for the Runt domain that predict that R131 is in proximity to DNA and not directly at the protein/protein interaction surface with CBF-β. CCD mutations have been correlated with three main DNA binding peptides in the RUNX2 runt domain: the βA’-B loop (V125-V138) that includes R131, the βE’-F loop (R190-S196), and three arginine residues that are part of the nuclear localization signal (R225, R228, and R229) (Otto et al., 2002). Specific mutations (R176W, F183S, K204N, T206I, R211W, and R211Q) in RUNX2 are postulated to perturb DNA binding without affecting heterodimerization with CBF-β (Yoshida et al., 2003). Our present results establish that the RUNX2R131G mutation also distinguishes between DNA binding activity and CBF-β heterodimerization.

Most hematopoietic missense mutations in RUNX1 involve DNA-contacting residues in the runt domain. For instance, Osato et al., (1999) reported a missense mutation resulting in conversion of arginine 80 to cysteine in RUNX1 (RUNX1R80C), which corresponds to arginine 131 of RUNX2, in a blastic phase patient with chronic myeloid leukemia. Similar to our results, this RUNX1R80C is active in heterodimerization with CBF-β, but shows neither DNA binding nor trans-activation. According to genotype-phenotype correlation studies of RUNX1 mutations in AML patients, RUNX1R80C has been classified as a strong dominant negative mutation (Yoshida et al., 2003). In contrast, CCD mutations exhibit haploinsufficiency effects instead of dominant negative effects. For this reason, it has been hypothesized that the CCD and hematopoietic disease mutations in RUNX2 and RUNX1, respectively, are functionally distinct (Matheny et al., 2007). Our data suggest that the RUNX2R131G mutant may act as a functionally defective competitive inhibitor consistent with dosage insufficiency rather than dominant negative interference with wild type function. Because RUNX1R80C and RUNX2R131G have similar structural and biochemical properties (i.e., loss of DNA binding and retention of heterodimerization), the molecular basis for the clinical outcomes in leukemia (for RUNX1 mutations) or CCD (for RUNX2) may perhaps be fundamentally similar and be due to dosage insufficiency. However, the different clinical phenotypes observed for distinct RUNX2 mutants in CCD could be directly due to differences in functional properties of the mutants. We propose that differences in the competency to bind DNA or co-regulators, as well as sequestration in subnuclear or cytoplasmic compartments, may each contribute to the effectiveness of distinct mutants as competitive inhibitors and the phenotypic penetrance of RUNX2 mutations in the clinical manifestation of CCD.

Figure 5. Three-dimensional structure of RUNX1 and RUNX2 runt domain.

The three-dimensional structures of runt domains from RUNX1 and RUNX2 were annotated based on amino acid numbering for each protein. Red circle indicates the novel missense mutation site (R131G) and yellow color points to DNA binding residues. The three-dimensional structures were obtained from NCBI (CDD pfam00853).

ACKOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the grants of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project (Ministry of health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea, A010252 and A030003) and Brain Korea 21 Project in 2006. This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AR49069 (to A. v. W.), as well as R01 AR39588, P01 AR48818 and P01 CA82834 (to G. S. S. and J. B. L.).

REFERENCES

- Bae S-C, Ogawa E, Mauyama M, Oka H, Satake M, Shigesada K, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJm, Copeland NG, Ito Y. PEBP2αB/Mouse AML1 consists of multiple isoforms that possess differential transactivation potentials. Mol cell Biol. 1994;14:3242–3252. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee C, McCabe LR, Choi JY, Hiebert SW, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. Runt homology domain proteins in osteoblast differentiation: AML3/CBFA1 is a major component of a bone-specific complex. J Cell Biochem. 1997;66:1–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19970701)66:1<1::aid-jcb1>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J-Y, Pratap J, Javed A, Zaidi SK, Xing L, Balint E, Dalamangas S, Boyce B, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein JL, Jones SN, Stein GS. Subnuclear targeting of Runx/Cbfa/AML factors is essential for tissue-specific differentiation during embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8650–8655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151236498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crute BE, Lewis AF, Wu Z, Bushweller JH, Speck NA. Biochemical and biophysical proterties of the core-binding factor alpha2 (AML1) DNA-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26251–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ML, Seto ML, Hing AV, Bull MJ, Hopkin RJ, Leppig KA. Cleidocranial dysplasia with severe parietal bone dysplasia: C-terminal RUNX2 mutations. Birth Defects Research (Part A) 2006;76:78–85. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Karsenty G. Missense mutations abolishing DNA binding of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor OSF2/CBFA1 in cleidocranial dysplasia. Nature Genet. 1997;16:307–310. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:747–754. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Karsenty G. Genetic control of cell differentiation in the skeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:614–619. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed A, Guo B, Hiebert S, Choi J-Y, Green J, Zhao SC, Osborne MA, Stifani S, Stein JL, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Groucho/TLE/R-esp proteins associate with the nuclear matrix and repress RUNX (CBF(alpha))/AML/PEBP2(alpha)) dependent activation of tissue-specific gene transcription. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2221–2231. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed A, Barnes GL, Jasanya BO, Stein JL, Gerstenfeld L, Lian JB, Stein GS. runt homology domain transcription factors (Runx, Cbfa, and AML) mediate repression of the bone sialoprotein promoter: evidence for promoter context-dependent activity of Cbfa proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2891–2905. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2891-2905.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagoshima H, Shigesada K, Satake M, Ito Y, Miyoshi H, Ohki M, Pepling M, Gergen P. The Runt domain identifies a new family of heteromeric transcriptional regulators. Trend Genet. 1993;9:338–341. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90026-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Kim JH, Bae SC, Choi J-Y, Kim HJ, Ryoo HM. The protein kinase C pathway plays a central role in the fibroblast growth factor-stimulated expression and transactivation activity of Runx2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:319–326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Nam SH, Kim HJ, Park HS, Ryoo HM, Kim SY, Cho TJ, Kim SG, Bae SC, Kim IS, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Lian JB, Choi JY. Four novel RUNX2 mutations including a splice donor site result in the cleidocranial dysplasia phenotype. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:114–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Lee HJ, Hwang KS, Lee M, Kim JW, Bang Y-J, Kang GH. Methylation of RUNX3 in various types of human cancers and premalignant stages of gastric carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2004;84:479–84. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamato R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Thirunavukkarasu K, Zhou L, Pastore L, Baldini A, Hecht J, Geoffroy V, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Missense mutations abolishing DNA binding of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor OSF2/CBFA1 in cleidocranial dysplasia. Nat Genet. 1997;16:307–310. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q-L, Ito K, Skakura C, Fukamachi H, Inoue K-i, Chi X-Z, Lee K-Y, Nomura S, Lee C-W, Han S-B, et al. Bae-C S, Ito Y. Causal relationship between the loss of RUNX3 expression and gastric cancer. Cell. 2002;109:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Pan W, Xu W, He N, Chen X, Liu H, Quarles L Darryl, Zhou H, Xiao Z. RUNX2 mutations in Chinese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Mutagenesis. 2009;24:425–31. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gep025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian JB, Stein GS, Javed A, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Montecino M, Hassan MQ, Gaur T, Lengner CJ, Young DW. Networks and hubs for the transcriptional control of osteoblastogenesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Javed A, Hussain S, Colby J, Frederick D, Pratap J, Xie R, Gaur T, van Wijnen AJ, Jones SN, Stein GS, Lian JB, Stein JL. A Runx2 threshold for the cleidocranial dysplasia phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:556–68. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny CJ, Speck ME, Cushing PR, Zhou Y, Corpora T, Regan M, Newman M, Roudaia L, Speck CL, Gu T-L, Griffey SM, Bushweller JH, Speck NA. Disease mutations in RUNX1 and RUNX2 create nonfunctional, dominant-negative, or hypomorphic alleles. EMBO J. 2007;26:1163–1175. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundlos S, Otto F, Mundlos C, Mulliken JB, Aylsworth AS, Albright S, Lindhout D, Cole WG, Henn W, Knoll JHM, Owen MJ, Mertelsmann R, Zabel BU, Olsen BR. Mutations involving the transcription factor CBFA1 cause cleidocranial dysplasia. Cell. 1997;89:773–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Werner MH. Functional mutagenesis of AML1/RUNX1 and PEBP2 beta/CBF beta define distinct, non-overlapping sites for DNA recognition and heterodimerization by the Runt domain. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:191–203. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osato M, Asou N, Abdalla E, Hoshino K, Yamasaki H, Okubo T, Suzushima H, Takatsuki K, Kanno T, Shigesada K, Ito Y. Biallelic and heterozygous point mutations in the Runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2αB gene associated with myeloblastic leukemias. Blood. 1999;93:1817–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, Denzel A, Gilmour KC, Rosewell IR, Stamp GWH, Beddington RSP, Mundlos S, Olsen BR, Selby PB, Owen MJ. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell. 1997;89:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto F, Kanegane H, Mundlos S. Mutations in the RUNX2 gene in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:209–216. doi: 10.1002/humu.10043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratap J, Galindo M, Zaidi SK, Vradii D, Bhat BM, Robinson JA, Choi J-Y, Komori T, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ. Cell growth regulatory role of Runx2 during proliferative expansion of pre-osteoblasts. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5357–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppin C, Pellizzari L, Fabbro D, Fogolari F, Tell G, Tessa A, Santorelli FM, Damante G. Functional analysis of a novel RUNX2 missense mutation found in a family with cleidocranial dysplasia. J Hum Genet. 2005;50:679–683. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quack I, Vonderstrass B, Stock M, Aylsworth AS, Becker A, Brueton L, Lee PJ, Majewski F, Mulliken JB, Suri M, Zenker M, Mundlos S, Otto F. Mutation analysis of core binding factor A1 in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1268–1278. doi: 10.1086/302622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo HM, Kang HY, Lee SK, Lee KE, Kim JW. RUNX2 mutations in cleidocranial dysplasia patients. Oral Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01623.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai N, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Ui K, Tokunaga K, Hirose R, Uchinuma E, Susami T, Takato T. A case of a Japanese patient with cleidocranial dysplasia possessing a mutation of CBFA1 gene. Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:31–34. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Mori E, Komori T, Kawahata H, Sugimoto M, Terai K, Shimizu H, Yasui TL, Ogihara H, Yasui N, Ochi T, Kitamura Y, Ito Y, Nomura S. Transcriptional regulation of osteopontin gene in vivo by PEBP2alphaA/CBFA1 and ETS1 in the skeletal tissues. Oncogene. 1998;17:1517–1525. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahirov TH, Inoue-Bungo T, Morii H, Fujikawa A, Sasaki M, Kimura K, Shiina M, Sato K, Kumasaka T, Yamamoto M, Ishii S, Ogata K. Structural analyses of DNA recognition by the AML1/Runx-1 Runt domain and its allosteric control by CBF-β. Cell. 2001;104:755–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukkarasu K, Magajaan M, McLarren KW, Stifani S, Karsenty G. Two domains unique to osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osf2/Cbfa1 contribute to its transactivation function and its inability to heterodimerize with Cbf-β. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4197–4208. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Gergen JP, Groner Y, Hiebert SW, Ito Y, Liu P, Neil JC, Ohki M, Speck N. Nomenclature for Runt-related (RUNX) proteins. Oncogene. 2004;23:4209–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi R, Chen LF, Shigesada K, Murakami Y, Ito Y. A WW domain-containing yes-associated protein (YAP) is a novel transcriptional co-activator. EMBO J. 1999;18:2551–62. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Kanegane H, Osato M, Yanagida M, Miyawaki T, Ito Y, Shigesada K. Functional analysis of RUNX2 mutations in Japanese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia demonstrates novel genotype-phenotype correlations. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:724–738. doi: 10.1086/342717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Kanegane H, Osato M, Yanagida M, Miyawaki T, Ito Y, Shigesada K. Functional analysis of RUNX2 mutations in cleidocranial dysplasia: novel insights into genotype-phenotype correlations. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003;30:184–93. doi: 10.1016/s1079-9796(03)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DW, Hassan MQ, Pratap J, Galindo M, Zaidi SK, Lee SH, Yang X, Xie R, Javed A, Underwood JM, Furcinitti P, Imbalzano AN, Penman S, Nickerson JA, Montecino MA, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Mitotic occupancy and lineage-specific transcriptional control of rRNA genes by Runx2. Nature. 2007;445:442–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SK, Javed A, Choi JY, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS. A specific targeting signal directs Runx2/Cbfa1 to subnuclear domains and contributes to transactivation of the osteocalcin gene. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3093–3102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.17.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SK, Young DW, Choi J-Y, Pratap J, Javed A, Montecino M, Stein JL, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Tyrosine phosphorylation controls Runx2-mediated subnuclear targeting of YAP to repress transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43363–43366. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Yasui N, Ito K, Huang G, Fujii M, Hanai J, Nogami H, Ochi T, Miyazono K, Ito Y. A RUNX2/PEBP2alpha A/CBFA1 mutation displaying impaired transactivation and Smad interaction in cleidocranial dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10549–10554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180309597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Chen Y, Zhou L, Thirunavukkarasu K, Hecht J, Chitayat D, Gelb BD, Pirinen S, Berry SA, Greenberg CR, Karsenty G, Lee B. CBFA1 mutation analysis and functional correlation with phenotypic variability in cleidocranial dysplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2311–2316. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]