Abstract

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), which is caused by inactivating mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, is characterized by loss of lower motor neurons in the spinal cord. The gene encoding SMN is very highly conserved in evolution, allowing the disease to be modeled in a range of species. The similarities in anatomy and physiology to the human neuromuscular system, coupled with the ease of genetic manipulation, make the mouse the most suitable model for exploring the basic pathogenesis of motor neuron loss and for testing potential treatments. Therapies that increase SMN levels, either through direct viral delivery or by enhancing full-length SMN protein expression from the SMN1 paralog, SMN2, are approaching the translational stage of development. It is therefore timely to consider the role of mouse models in addressing aspects of disease pathogenesis that are most relevant to SMA therapy. Here, we review evidence suggesting that the apparent selective vulnerability of motor neurons to SMN deficiency is relative rather than absolute, signifying that therapies will need to be delivered systemically. We also consider evidence from mouse models suggesting that SMN has its predominant action on the neuromuscular system in early postnatal life, during a discrete phase of development. Data from these experiments suggest that the timing of therapy to increase SMN levels might be crucial. The extent to which SMN is required for the maintenance of motor neurons in later life and whether augmenting its levels could treat degenerative motor neuron diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), requires further exploration.

Introduction: spinal muscular atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), which is characterized by degeneration of spinal cord lower motor neurons that leads to proximal muscle wasting and paralysis, is a common autosomal recessive disease affecting 1 in 6000 live births (Pearn, 1978; Lefebvre et al., 1995). The disease is classified into four types (Type I–IV) based on the age of onset and clinical symptoms. Although there is a wide spectrum of clinical severity, in its commonest and most severe form (Type I), SMA leads to death in infancy from respiratory muscle weakness. Even patients with non-fatal forms of SMA (Types III and IV) are considerably disabled and there is an urgent need for treatments that slow or arrest progression of the disease.

The complex molecular genetic basis of SMA raises challenges for modeling the disease in other species. Owing to an intrachromosomal duplication event on chromosome 5q13, humans possess two copies of the gene encoding ‘survival motor neuron’ (SMN) – SMN1 and SMN2 (Lefebvre et al., 1995). Deletion or gene conversion events render SMA patients homozygously null for SMN1, whereas they retain a variable number of SMN2 copies. A critical C-to-T transition six base pairs into exon 7, present in all copies of the SMN2 gene described in humans to date, causes aberrant splicing of 80–90% of SMN2 transcripts, causing them to lack exon 7 (SMNΔ7) and therefore produce a protein product with reduced stability (Lorson et al., 1999; Monani et al., 1999; Lorson and Androphy, 2000). SMN levels generally correlate with disease severity (Coovert et al., 1997; Lefebvre et al., 1997) and, because complete loss of SMN is lethal, SMA only arises as a disease in humans owing to the presence of SMN2, which provides sufficient residual full-length protein for cellular viability (McAndrew et al., 1997; Feldkötter et al., 2002; Mailman et al., 2002). SMA is therefore a disease of low levels of protein and not total ablation, a situation that any model system, either in vitro or in vivo, must reproduce in order to provide meaningful insights.

SMN is widely and constitutively expressed, and has been implicated in a range of cellular processes, of which small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) assembly is currently the best characterized (Fischer et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1997; Meister et al., 2001; Pellizzoni et al., 2002). Owing to the high degree of evolutionary conservation of the gene encoding SMN, the effects of SMN protein depletion have been modeled in diverse organisms, including in the invertebrates Caenorhabditis elegans (Briese et al., 2009; Sleigh et al., 2011) and Drosophila melanogaster (Chan et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2008), and the vertebrates Danio rerio (McWhorter et al., 2003; Boon et al., 2009) and Mus musculus (Hsieh-Li et al., 2000; Monani et al., 2000; Le et al., 2005). Zebrafish and the invertebrate models are well suited to large-scale screening of drug or genetic-knockdown libraries prior to mammalian validation (Westlund et al., 2004; Dimitriadi et al., 2010; Sleigh and Sattelle, 2010). However, given that the essential elements of the organization of neuromuscular function are conserved across 50 million years of evolution between mice and humans, mouse models are probably best placed to answer fundamental questions about SMN biology in the nervous system and the pathogenesis of SMA.

Mouse models of SMA

Mouse models not only allow the dissection of biological processes and assessment of gene and protein function in a mammalian context, but are a useful preclinical tool for testing potential therapies. Thus, an ideal mouse model of SMA should faithfully recapitulate the cellular levels of SMN protein seen in patients in order to preserve the relative selectivity for motor neuron degeneration. Levels that are too low, such as can be found in models involving tissue-specific ablation of SMN (Frugier et al., 2000), simply induce cell death through disrupting the constitutive cellular function of SMN, providing limited insight into motor neuron vulnerability. The level of SMN expressed should also ideally be titrated to ensure that the mouse lives long enough for phenotypic analysis and therapeutic trials.

SMN2 transgenic mice

Mice possess a single Smn gene, which has 82% amino acid identity with its human homolog and a similar expression pattern (Bergin et al., 1997; DiDonato et al., 1997; Viollet et al., 1997). Homozygous Smn deletion results in massive embryonic cell death before implantation (Schrank et al., 1997). Heterozygous null mice lack a marked clinical phenotype, although some reports suggest that there is histologically detectable age-dependent loss of neuromuscular integrity (Schrank et al., 1997; Jablonka et al., 2000; Balabanian et al., 2007). A number of different strategies have been employed to produce models that recapitulate the human genotype (summarized in Table 1, with further information at http://jaxmice.jax.org/list/ra1733.html). Two groups showed that expression of a human SMN2 transgene on the Smn-null background rescues lethality, and that transgene copy number modifies severity (Hsieh-Li et al., 2000; Monani et al., 2000). Mice carrying one or two copies of SMN2 (Smn−/−; SMN2+/+) are indistinguishable from controls at birth but die before postnatal day 7 (P7), and so are often referred to as the ‘severe’ model (and will be referred to as such in the remainder of this review article). Mice with four or more copies of SMN2 show complete rescue and a normal lifespan, indicating that modestly enhanced expression of full-length SMN from the SMN2 gene can prevent SMA, confirming the idea that enhancing SMN2 expression is a potential therapeutic strategy.

Table 1.

Mouse models of SMA

| Genotype | Severity of phenotypea | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smn−/− | ++++ | Death of embryo occurs prior to uterine implantation. | (Schrank et al., 1997) |

| Smn+/− | + | Early acute loss of lumbar spinal cord motor neurons (∼28% within 5 weeks), with subsequent slowly progressive reduction over an extended time scale. | (Jablonka et al., 2000; Balabanian et al., 2007) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2(2Hung)+/+ | + to +++ | Transgene including human SMN2, SERF1 and part of NAIP; rescues embryonic lethality of Smn−/−. Transgene copy number correlates with disease severity, which ranges from death within 1 week to normal survival. |

(Hsieh-Li et al., 2000) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2(89Ahmb)+/+ | + to +++ | Transgene containing only the SMN2 locus, rescues Smn−/− embryonic lethality. 42/56 mice with one or two transgene copies were stillborn or died before 6 hours, with the remainder dying between 4–6 days. Mice with eight copies of the transgene reach adulthood. |

(Monani et al., 2000) |

| SmnF7/Δ7; NSE-Cre+ | ++ |

SmnF7/Δ7 mice with Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of Smn exon 7 in neuronal tissue. Mean lifespan: 25 days. |

(Frugier et al., 2000; Cifuentes-Diaz et al., 2002) |

| SmnF7/Δ7; HSA-Cre+ | ++ |

SmnF7/Δ7 mice with Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of Smn exon 7 in myoblasts and post-mitotic fused myotubes of skeletal muscle. Mean lifespan: 33 days. |

(Cifuentes-Diaz et al., 2001) |

| Smn+/−; Gemin2+/− | + | Mice with heterozygous deletion of Smn and Gemin2 display an accelerated loss of motor neurons compared with Smn+/− mice. | (Jablonka et al., 2002) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2(89Ahmb)+/−; SMN1(A2G)+/− | + | Mean survival of mice with a single A2G transgene and one copy of SMN2 is 227 days, whereas mice homozygous for A2G are relatively indistinguishable from controls. | (Monani et al., 2003) |

| SmnF7/F7; HSA-Cre+ | + |

SmnF7/F7 mice with Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of Smn exon 7 in post-mitotic fused myotubes of skeletal muscle. Without heterozygous deletion of Smn exon 7 in all somatic cells, animals live for a median of 8 months. |

(Nicole et al., 2003) |

| SmnF7/F7; NSE-Cre+ | ++ |

SmnF7/F7mice with Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of Smn exon 7 in neuronal tissue. Mean lifespan: 31±2 days. |

(Ferri et al., 2004) |

| SmnF7/F7; Alfp-Cre+ | ++++ |

SmnF7/F7 mice with Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of Smn exon 7 in hepatocytes. Causes late embryonic lethality at E18. Heterozygous deletion has no obvious effect. |

(Vitte et al., 2004) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2(89Ahmb)+/+; SMNΔ7+/+ | +++ | Transgene containing human SMNΔ7, the predominant isoform produced by SMN2; improves the phenotype of Smn−/−; SMN2+/+. Mean lifespan: 13.3±0.3 days. |

(Le et al., 2005) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2+/+; SMN1(A111G)+/− | + | Transgene containing the SMN1 allele seen in Type I and II patients; improves survival to over 1 year with no obvious phenotype. | (Workman et al., 2009) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2+/+; SMN1(VDQNQKE)+/− | +++ | Transgene containing SMN1 exons 1–6 with an additional motif; has little effect on lifespan extension. | (Workman et al., 2009) |

| Smn2B/− | ++ |

Smn transgene harboring three nucleotide substitutions within the exonic splicing enhancer of exon 7. Mean lifespan: 28 days. |

(Bowerman et al., 2009) |

| Smn−/−; SMN2(N11)+/−; SMN2(N46)+/− | +++ | Mice with three copies of SMN2 were generated by crossing strains with two (N11) and four (N46) copies. Mean lifespan: 15.2±0.4 days. |

(Michaud et al., 2010) |

| SmnF7/−; SMN2(89Ahmb)+/+; Olig2-Cre+ | + |

SmnF7/−; SMN2+/+ mice (i.e. Smn+/−; SMN2+/+) with Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of Smn exon 7 in spinal cord motor neuron progenitor cells. ∼70% of mutants survived to 12 months, yet were clearly distinguishable from controls. |

(Park et al., 2010) |

| Smn1tm1Cdid/tm1Cdid; CreEsr1 and Smn1tm2Cdid/tm2Cdid; CreEsr1 | ++++ | Inducible Smn alleles that mimic SMN2 splicing are homozygous embryonic lethal (E12.5–E15.5) and normal when heterozygous. In the presence of Cre recombinase, loxP-flanked neomycin (Neo) gene resistance cassettes situated in Smn intron 7 are excised, producing full-length Smn. When crossed with a tamoxifen-inducible Cre allele (CreEsr1), early embryonic induction of full-length Smn by tamoxifen can rescue embryonic lethality. |

(Hammond et al., 2010) |

+, mild; ++, moderate; +++, severe; ++++, embryonic lethal.

SmnF7/Δ7 mice are Smn+/Δ7, and SmnF7/F7 mice are Smn+/+.

Modifications to the severe SMN2 mouse

Introduction of a second transgene, containing human SMNΔ7 cDNA, into the severe model extends the lifespan from 6 to 13 days (Le et al., 2005). Initially generated to assess potential SMNΔ7 toxicity (Kerr et al., 2000), the ‘SMNΔ7’ model (Smn−/−; SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+), which is still in effect a model of severe postnatal SMA, is thought to be milder owing to the formation of heterologous complexes between full-length SMN and SMNΔ7, which might stabilize SMN and affect its turnover. A number of other transgenes containing point mutations in SMN1 (A2G, A111G) have also been introduced into the severe model, resulting in increased lifespan (Monani et al., 2003; Workman et al., 2009). However, unlike SMN2, which generates a small amount of full-length protein, none of the other transgenes rescue the embryonic lethality caused by Smn deletion, indicating that some full-length SMN is an absolute requirement for normal cellular function. Using a slightly different approach to reduce Smn levels, a knock-in allele that disturbs endogenous Smn splicing (Smn2B/−), similar to human SMN2, was shown to result in more moderate severity, with a few animals living longer than 1 month (Bowerman et al., 2009).

Cre-loxP models

Targeting of genomic DNA using the Cre-loxP recombination system to perform deletion of Smn exon 7 from a conditional (floxed) allele (SmnF7) should theoretically result in the sole production of SmnΔ7 and complete absence of full-length Smn in the presence of Cre recombinase. Indeed, crossing these mice with tissue-specific Cre mouse lines effectively produces complete cellular knockdown of Smn in target tissues (Frugier et al., 2000; Cifuentes-Diaz et al., 2001; Cifuentes-Diaz et al., 2002; Nicole et al., 2003; Vitte et al., 2004). The complete absence of functional Smn, which never occurs in patients, suggests that these models provide only limited insights into the pathogenesis of SMA; however, the absence of convincing data regarding whether complete ablation of full-length Smn is achieved at a range of time points precludes a definitive judgment. A more recently published study in which endogenous Smn was conditionally depleted in motor neuron progenitor cells, but importantly was not totally ablated owing to the presence of transgenic human SMN2, provides a potentially better model of the disease (Park et al., 2010). However, the presence of normal levels of Smn in tissues other than motor neurons seems to result in an unexpectedly mild phenotype, hinting that the SMA phenotype might be more dependent on systemic effects than previously appreciated.

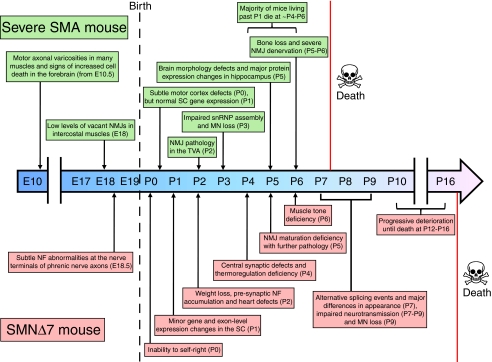

The severe (SMN2 transgenic) mouse and its modification, the SMNΔ7 mouse, have become the most widely used SMA models (Fig. 1). In the remainder of this Perspective, we discuss how these and other mouse mutants have been used to address important outstanding biological questions about SMA. We begin by examining whether SMA is neurodegenerative or neurodevelopmental in its essential character, and then move on to discuss the evidence for absolute or relative motor neuronal specificity in SMA, as well as the timing of SMN protein action during development. Finally, we examine the controversy about whether SMA is a disorder of splicing regulation or whether SMN has a distinct neuronal function.

Fig. 1.

Timeline illustrating the major cellular and symptomatic events during the embryonic and postnatal development of severe (Smn−/−; SMN2+/+) and SMNΔ7 (Smn−/−; SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+) mouse models of SMA. MN, motor neuron; NF, neurofilament; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; SC, spinal cord; snRNP, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; TVA, transversus abdominis.

The nature of SMA: neurodegeneration or failure of normal development?

The commonest and most severe form of SMA (Type I; previously known as Werdnig-Hoffmann disease) begins prenatally or in the early postnatal period, during a time of maturation and stabilization of the neuromuscular system, the basic pattern of which is laid down earlier in development. By contrast, the onset of muscle weakness in at least some cases of other forms of SMA (late-childhood and adult-onset SMA) occurs after the neuromuscular system has developed. Nevertheless, in these later-onset patients it remains possible that the foundation for subsequent loss of neuromuscular integrity and subsequent age-dependent motor neuron degeneration is established in earlier development.

Primary motor neurons isolated from the lumbar spinal cord of severe SMA mouse embryos at embryonic day 14 (E14) do not show reduced survival in culture, but axon elongation, growth-cone size, β-actin dynamics and spontaneous excitability are all significantly impaired (Rossoll et al., 2003; Jablonka et al., 2007). A similar phenotype has also been observed in cultured sensory neurons (Jablonka et al., 2006). Moreover, differentiation and neuritogenesis, but not survival or growth, of neurospheres from the brains of severe SMA mouse embryos is abnormal (Shafey et al., 2008). However, direct neurophysiological recording from Smn-deficient mouse motor neurons in culture does not show a functional deficit (Zhang et al., 2010).

In contrast to the above observations from in vitro systems showing abnormalities in embryonic motor neurons, the available SMA mouse models have similar numbers of motor neurons in the spinal cord at birth compared with their control littermates, and are visibly indistinguishable from these mice, suggesting that gross prenatal development is largely unaffected by Smn depletion (Hsieh-Li et al., 2000; Monani et al., 2000; Le et al., 2005). No major defects in axonal morphology or outgrowth were seen at various embryonic stages in multiple different tissues of severe mutants expressing GFP in motor neurons (Hb9-SMA mice) (McGovern et al., 2008). There was, however, a significant increase in the number of vacant synapses lacking motor axon input at E18 in intercostal muscles (McGovern et al., 2008), and neuromuscular junction (NMJ) neurofilament accumulation and an increased length of axon terminals was observed in the phrenic nerve of SMNΔ7 mice at E18.5 (Kariya et al., 2009). Nonetheless, in a detailed study of the NMJ in severe SMA mice at a pre-symptomatic stage (P1), there were no detectable defects in motor axon patterning and branching, NMJs were formed normally, and there were no significant changes in gene expression in the spinal cord (Murray et al., 2010b).

Disruption of the NMJ is known to occur in a range of different muscles during early and late symptomatic stages in postnatal severe SMA mice (Murray et al., 2010a). Neuromuscular pathology was found to be more pronounced in the predominantly slow-twitch transversus abdominis muscle as well as the caudal band of the fast-twitch levator auris longus in these mice (Murray et al., 2008; Ruiz et al., 2010), suggesting differential vulnerability of NMJs, which has also been observed between the diaphragm and soleus (Voigt et al., 2010). Similar progressive postnatal neuromuscular pathology has been observed in a new SMA model that carries three copies of SMN2 (Michaud et al., 2010) and in the SMNΔ7 mouse (Kariya et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2009), although the majority of pathology observed in SMNΔ7 mice resulted in modified neurofilament accumulation and functional disruption at the NMJ rather than loss of presynaptic motor nerve terminals. These presynaptic changes occurred in tandem with a delay in developmental maturation of postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors (Biondi et al., 2008; Kariya et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2009). Alongside these morphological and functional changes at the NMJ, longitudinal exon-level gene-expression studies in the spinal cord of the SMNΔ7 model showed an apparent failure of expression of genes that cluster in postnatal developmental pathways (Bäumer et al., 2009).

If SMN has distinct functions during the period of postnatal neuromuscular development, this would have profound implications for the timing of SMN replacement therapy. Observations in mouse models of SMA suggest that NMJs can form and function normally prior to the postnatal onset of disease (Murray et al., 2010b), and that NMJ denervation precedes motor neuron loss (Fig. 1) (Kariya et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2009). Thus, the high levels of SMN seen during early postnatal development, the window of developmental vulnerability to SMN depletion and the perinatal onset of severe SMA all suggest that the disease is related to postnatal maturation events in the neuromuscular system (Bäumer et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2010b).

Is motor neuron specificity in SMA absolute or relative?

In contrast to evidence from mouse models of severe SMA, severe infantile SMA in patients carrying only one or two copies of SMN2 can begin in utero and can be associated with extended involvement of the peripheral nervous system, including demyelination, inexcitability and axonal degeneration in sensory neurons (Korinthenberg et al., 1997; Omran et al., 1998; Rudnik-Schöneborn et al., 2003; Anagnostou et al., 2005). Moreover, it has been recognized by neuropathologists for many years that specific regions of the brain such as the thalamus show neuronal loss in severe SMA patients, although this has been assumed to be subclinical (Shishikura et al., 1983; Yohannan et al., 1991; Oka et al., 1995; Hayashi et al., 1998; Araki et al., 2003; Ito et al., 2004).

The first major study of the involvement of non-motor nervous tissue in SMA in mice reported that cell body size and number in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were normal, even at the late symptomatic stage (P5) in the severe model, but that sensory neurons cultured from E14 embryos showed reduced neurite length and growth-cone size (Jablonka et al., 2006). Nerve endings from E14 SMA mouse embryo footpads were much thinner than those of controls and failed to reach their target destination in the outer epidermal layer, although without displaying a difference in number. Consistent with this, the latency to paw withdrawal in a hot plate test was increased more than twofold in a new severe model (Michaud et al., 2010). In the SMNΔ7 mouse, no defect in tactile sensory behavior was seen at early to mid disease stages, as assessed by the clasping of paws in response to gentle stimulation (Butchbach et al., 2007). Recently, sensory and motor synapses were examined in Olig2-Cre mice (mild SMA model), which have selectively depleted Smn levels in motor neuron progenitor cells (Park et al., 2010). By staining sensory nerve terminals of the DRG, the authors showed that adult mutant mice had a reduction in the number and the mean area of synaptic boutons positioned against cholinergic motor neurons. These defects were present by P7, indicating that dysfunction in sensory neuronal projection onto ventral horn cells develops at early stages of the disease. Central synaptic defects that precede motor neuron loss have also recently been reported in the spinal cord of SMNΔ7 mice by P4 (Ling et al., 2010; Mentis et al., 2011), which were more severe in proprioceptive inputs onto motor neurons innervating proximal muscles (Mentis et al., 2011). Olig2 expression is confined to spinal motor neurons and oligodendrocytes, so the sensory neuron defects seen in this Cre-loxP mouse model are unlikely to be caused by Smn depletion in DRG proprioceptive neurons, and are perhaps a direct consequence of pathological mechanisms triggered within the motor neurons (Park et al., 2010). In addition to affecting motor and sensory neurons, it appears that Smn reduction also affects neuritogenesis and neurogenesis in the retinal neurons of Smn2B/−mice (Liu et al., 2011).

Pathological changes in the brain have also been studied in severe SMA mice. Increased cell death was observed in the forebrain of E14.5 mutant embryos, with the telencephalon being the most severely affected (Liu et al., 2010). This cell death was independent of genetic background and was associated with a greater than 70-fold increase in the amount of irregular nuclei. Striking pathological foci of hyperchromatic cells containing cell debris and condensed or shrinking nuclei were also observed. As expected, cell death in the telencephalon was less severe at earlier embryonic stages. Reduced Smn expression has also been shown to affect perinatal development of the mouse brain, with a lower brain weight and size at late symptomatic but not pre-symptomatic stages (Wishart et al., 2010). Interestingly, morphology varied between different brain regions, suggesting a gradient of susceptibility to Smn deficiency and not merely an overall reduction in brain volume as a reflection of smaller body size. The primary motor cortex displayed a subtle progressive decline in size from birth, whereas the primary somatosensory cortex remained unaffected at all stages studied. The most striking defects were observed in the hippocampus: a 50% reduction in the size of the dentate gyrus in late-symptomatic SMA mice compared with controls was associated with a reduction in cell density, cell proliferation and postnatal neurogenesis (Wishart et al., 2010). Proteomic analysis of the hippocampus of SMA mice revealed numerous changes in the expression of proteins involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, growth, migration and development (Wishart et al., 2010). Notably, a microarray study has also identified deficits in normal proliferative pathways in the spinal cord of severe SMA mice, perhaps accounting for the reduced number of proliferating cells in the central canal of the spinal cord (Bäumer et al., 2009). Together, these studies implicate cellular proliferation and postnatal developmental pathways in the pathogenesis of SMA in both motor and non-motor regions of the nervous system.

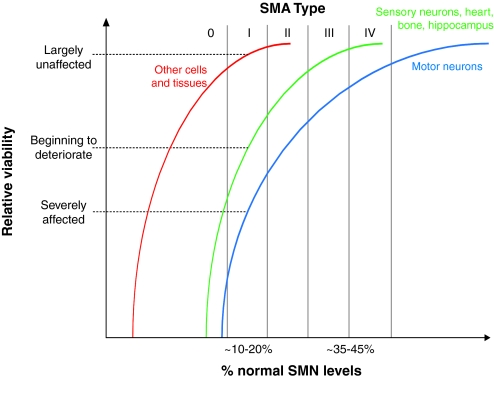

The presence of non-motor abnormalities in severe forms of SMA suggests that there is a gradient of susceptibility to SMN reduction in the nervous system, with motor neurons at one end of a spectrum (Fig. 2). These observations, coupled with evidence from mouse models indicating that dysfunction in non-neuromuscular tissue might also contribute to the overall pathology of SMA, have led to the development of the threshold hypothesis (Box 1). An important consequence of this work is that it clearly indicates that therapies aimed at replacing SMN, either by gene delivery or by oligonucleotide-mediated alterations in SMN2 splicing, should be delivered systemically. Although it is currently only a theoretical concern, it is possible that the correction of motor neuron loss and subsequent improved survival would reveal effects on other regions of the central nervous system (CNS) and other organs in the long term, with major clinical consequences.

Fig. 2.

The threshold hypothesis of SMA. There seems to be a differential susceptibility of cell types and tissues to SMN reduction. Motor neurons are most severely affected by SMN depletion and are thus at one end of a vulnerability-resistance spectrum. As protein levels are further reduced, additional tissues such as bone, heart and sensory neurons become affected, while other cells and tissues remain unaffected. For example, at approximately 10–20% of normal SMN levels, as seen in Type I SMA patients, motor neurons are severely affected, the heart and brain CNS show partial involvement, whereas many organs remain relatively unaffected. See Box 1 for details.

Is SMN a general survival factor for motor neurons?

Complete absence of SMN is lethal to all cells, but it remains unclear whether SMN is required at the same levels, and at all stages of development, in different cell types. Similarly, it remains unknown whether SMN levels are required to be above a critical threshold for motor neuron survival in adult life. If replacing SMN levels after a specific developmental time point would have little or no effect on the trajectory of disability, this has major implications for the optimization of SMA therapy. Similarly, it is important to understand whether therapies must achieve a maintenance level of SMN into adulthood to preserve neuromuscular integrity in the face of normal aging. Furthermore, if SMN can act as a survival factor for motor neurons in adult life, it might serve as a therapeutic target for other neuromuscular diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The onset of SMA is not infrequently reported to be rather sudden, occurring over a period of days to weeks. Rapid decline in motor function is then followed by a long period in which disease progression is relatively slow (Sumner, 2007). A similar phenomenon has been reported in the Olig2-Cre SMA mice, in which Smn is selectively depleted in motor neurons (Park et al., 2010). Although at birth these mice are indistinguishable from controls, mutants rapidly develop functional defects in the first week of life, some of which seemed to stabilize with age. These periods of rapid, progressive decline with subsequent relative stability suggest that there is a specific period of development during which SMN depletion is most detrimental to motor function. Consistent with this, Smn in the mouse is most highly expressed in spinal cord and brain during embryonic and neonatal development, after which time the levels are rapidly reduced and then maintained at a residual level throughout life (Gabanella et al., 2005). This mimics the situation in humans, in which expression levels of SMN are high in fetal tissue compared with in postnatal periods (Burlet et al., 1998).

Delivery of SMN using self-complementary adeno-associated virus 9 (scAAV9) at different developmental stages in SMNΔ7 mice had little effect when administered at P10, and only marginally increased survival when administered at P5. However, when administered at P1, there was an unprecedented improvement in lifespan to over 250 days at the time that the study was submitted for publication, indicating that earlier Smn replacement leads to better survival (Foust et al., 2010). This could be explained either by a higher level of motor neuron transduction efficiency in P1 mice compared with older mice (Foust et al., 2009) or by the effect of increased Smn levels being heavily dependent on the stage of development. Other studies in which compounds have been delivered at different stages support the latter view (Narver et al., 2008; Butchbach et al., 2010), as does the recent finding that early but not late embryonic restoration of Smn using two inducible Smn alleles can rescue lethality (Hammond et al., 2010).

Interestingly, mouse models of differing severities show similar degrees of motor neuron loss, perhaps indicating that the developmental stage at which degeneration occurs is a key determinant of disease progression. For instance, compared with controls, severe SMA mice display an approximate 40% reduction in spinal cord motor neuron number at P5, the late-symptomatic stage (Monani et al., 2000), whereas Smn heterozygotes display a 40% loss at 6 months and a 54% loss at 1 year (Jablonka et al., 2000). In a subsequent study of the heterozygous mice, a reduction of lumbar motor neurons by 28% was reported at 5 weeks and by 30% at 3 months, suggesting once again that there is an early period of susceptibility in which there is greater degeneration of motor neurons, followed by a period of relative stability (Balabanian et al., 2007).

The comparatively high SMN protein levels in the spinal cord during development and the apparent onset of SMA during a restricted perinatal period suggest that the requirement for SMN is temporally regulated in the nervous system. Nevertheless, there is also evidence that SMN might exert positive effects on survival later in life. Significant loss of facial and spinal motor neurons in Smn-null heterozygotes has been observed to occur between 6 and 12 months (Jablonka et al., 2000). However, this seems to be subclinical motor neuron loss, in keeping with the lack of a phenotype in 1 in 40 SMA carriers (those who only carry one copy of SMN1) in the general human population (Pearn, 1978).

A reduction in Smn levels by 50% has also been shown to worsen motor performance and survival of the SODG93A mouse model of ALS, suggesting that SMN might indeed be constitutively required throughout life (Turner et al., 2009). Furthermore, increasing SMN levels to rescue the severe phenotype in early life has not consistently prevented the ultimate development of a phenotype and a reduced overall lifespan (Meyer et al., 2009; Passini et al., 2010; Valori et al., 2010; Dominguez et al., 2011; Passini et al., 2011).

Is SMA a disorder of splicing regulation?

The best-characterized function of SMN is the assembly and processing of snRNPs. The SMN complex, which includes Gemins 2–8 and Unrip, ensures the specific and efficient assembly of a stable heptameric ring of Sm proteins (forming the Sm core) onto newly exported small nuclear ribonucleic acids (snRNAs) (Pellizzoni, 2007). After further maturation steps, the resulting snRNPs are exported into the nucleus and function in the removal of introns from pre-mRNA transcripts in the process of splicing (Pellizzoni et al., 2002). Depending on the class of intron removed, there are two principal types of spliceosomal snRNP that are assembled by the SMN complex: those found in the major spliceosome, which processes almost all eukaryotic introns, and those that splice all other introns as part of the minor spliceosome (Patel and Steitz, 2003). Mouse models provide an opportunity to address the hypothesis, developed from in vitro studies, that snRNP assembly is the crucial function of SMN that is relevant to the pathogenesis of SMA.

The central role of SMN in such a fundamental cellular process provides an adequate explanation as to why complete absence of the protein is universally lethal. Why reduced SMN levels cause such a specific effect on lower motor neurons remains the central conundrum of SMA research. It is possible that motor neurons have a greater constitutive requirement for snRNP assembly and are thus more susceptible to defects in splicing, or that disturbed splicing of a subset of neuron-specific genes triggers motor neuron loss. Alternatively, SMN might have a distinct motor-neuron-specific function, as suggested by the presence of SMN in protein complexes in the axon that have a different makeup than the canonical SMN complex that is involved in snRNP assembly (Briese et al., 2005; Rossoll and Bassell, 2009).

The evidence for a tight linkage between SMA and functional impairment of snRNP assembly is significant but as-yet incomplete. SMA-causing SMN1 mutations have been shown to affect the interaction of SMN with Sm proteins (Bühler et al., 1999; Pellizzoni et al., 1999), and snRNP assembly activity is reduced in SMA patient cells to an extent that is proportional to SMN levels (Wan et al., 2005; Gabanella et al., 2007). The first study to demonstrate a direct link between snRNP biogenesis and SMA pathology showed that defects in Xenopus laevis or zebrafish embryos that were caused by a reduction of SMN or Gemin2 can be rescued by injection of purified snRNPs (Winkler et al., 2005). However, a number of SMA-causing SMN1 mutations, including one found in a Type I SMA patient, display no defect in snRNP assembly activity (Shpargel and Matera, 2005) and, despite impairment of snRNP synthesis, endogenous snRNP and snRNA levels were found to be unaltered in patient-derived (Type I SMA) fibroblasts, a chicken cell line and a severe Drosophila mutant, all of which had severely reduced SMN levels (Wan et al., 2005; Gabanella et al., 2007; Rajendra et al., 2007). Moreover, despite a significant difference in lifespan between the severe and SMNΔ7 models (∼9 days), there is no difference in snRNP assembly activity (Gabanella et al., 2007), suggesting that the difference in disease severity is caused by differential effects on an additional function of the Smn protein. It should be noted that snRNAs that are not associated with Sm cores are unstable (Sauterer et al., 1988), so snRNA levels are similar to snRNP levels.

Box 1. The involvement of non-neuromuscular tissue in SMA and the threshold hypothesis.

There is evidence that cells and tissues outside of the nervous system are also affected in SMA. Bone and heart complications have been reported in numerous patients (Finsterer and Stöllberger, 1999; Kelly et al., 1999; Felderhoff-Mueser et al., 2002; Khawaja et al., 2004; Bach, 2007; Khatri et al., 2008; Rudnik-Schöneborn et al., 2008). Poor perfusion and autonomic dysfunction have also been observed (Arai et al., 2005; Hachiya et al., 2005; Araujo Ade et al., 2009). A similar picture is beginning to emerge in mouse models. SMN has recently been implicated in bone remodeling and skeletal pathogenesis in the severe model (Shanmugarajan et al., 2007; Shanmugarajan et al., 2009), which, along with the SMNΔ7 mouse, also displays cardiac defects including bradycardia and arrhythmia (Bevan et al., 2010; Heier et al., 2010; Shababi et al., 2010). Furthermore, numerous models display a vascular necrosis of the extremities (Hsieh-Li et al., 2000; Meyer et al., 2009; Gogliotti et al., 2010; Hua et al., 2010; Michaud et al., 2010; Riessland et al., 2010), and the vagus cranial nerve in the severe mouse appears defasciculated, with less distinct morphological boundaries (Liu et al., 2010). The pathological findings in cells other than motor neurons, which are predominantly seen in more severe cases, have led to the development of the threshold hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that there is a differential susceptibility of cells to SMN depletion (Fig. 2), and that different cell types and tissues fall in different positions within a vulnerability-resistance spectrum. At one extreme, motor neurons seem to be the most sensitive cell type to reduced SMN levels. As SMN levels are further reduced, the range of affected cells becomes greater, to a point at which there is insufficient protein for survival of any cell type. It is thus important that protein levels in animal models of SMA do not reach the threshold at which there is universal cell degeneration, because such a model will not be useful for dissecting the reasons why motor neurons are particularly vulnerable. Together, these findings suggest that SMA is a multisystem disorder; this has great significance for the development of new treatments, because therapies will need to be delivered systemically for the greatest chance of success. Moreover, improved understanding of this differential susceptibility is likely to offer further insights into the function of SMN in neurons.

Steady-state snRNA levels in spinal cord extracts of 3-day-old severe SMA mice are also only marginally reduced in spite of a tenfold decrease in snRNP assembly activity (Gabanella et al., 2007). This apparent contradiction indicates that cells possess an excess capacity to assemble snRNPs, such that reducing SMN levels has only a modest effect. However, levels of a subset of snRNAs belonging to the minor splicing pathway (U11 and U12) were significantly reduced in the brain and spinal cord of severe SMA mice (Gabanella et al., 2007). U11 snRNA levels were also lowered in the kidney, suggesting that reduced SMN levels can unevenly affect the profile of snRNPs in a tissue-specific manner. This preferential reduction in minor snRNAs in the context of reduced SMN levels has since been confirmed in a number of different models and tissues (Zhang et al., 2008; Workman et al., 2009).

The correlation between disease severity and snRNP assembly activity has been shown in a range of mouse models (Gabanella et al., 2007; Workman et al., 2009). In mouse spinal cord, snRNP biogenesis is most prominent in the CNS during embryogenesis and early postnatal development, correlating with levels of Smn (Gabanella et al., 2005). The spatiotemporal expression patterns of Smn and Gemin2 are closely co-regulated, and the subclinical motor neuron loss seen in Smn heterozygous mice is accelerated in Smn+/−; Gemin2+/− heterozygotes, which is associated with a reduction in snRNP assembly (Jablonka et al., 2001; Jablonka et al., 2002).

It is clear that the formation of snRNPs is affected by SMN reduction. However, the functional consequences of this disturbed assembly and how this contributes to SMA pathology are much less clear. If a failure of snRNP assembly is the pathological lesion that leads to selective motor neuron death, this would be predicted to cause dysfunctional splicing across a wide range of pre-mRNA transcripts at or before disease onset, and also to result in ‘aberrant’ transcripts that are not normally seen in tissues in physiological states. However, there is only an approximately twofold increase in the error rate of splice-site pairing in phenotypically normal fibroblasts from severe Type I SMA patients (Fox-Walsh and Hertel, 2009). In end-stage (P13) SMNΔ7 mice, Zhang et al. used exon-level microarrays to identify widespread tissue-specific splicing abnormalities, even in histologically normal tissues such as the kidney (Zhang et al., 2008). This curious finding suggests a lack of congruence between splicing abnormalities and cellular pathology, and, given that the mice assayed were moribund, might simply reflect a non-specific response to tissue injury. A longitudinal study of exon-level changes in the spinal cord of both severe and SMNΔ7 mice at pre-symptomatic (P1), early-symptomatic (P7) and late-symptomatic (P13) stages suggests that the vast majority of alternative splicing events are actually a late feature of disease and are thus unlikely to play a causative role in SMA pathology (Bäumer et al., 2009). Only a small number of transcripts were altered compared with control mice at the pre-symptomatic stage, and all alterations involved a shift to known isoforms. Additionally, the introns processed by the minor spliceosome were not preferentially affected, as might be expected if the specific reduction of minor spliceosomal snRNPs had a direct effect on splicing. The role of the small number of genes that are alternatively spliced early on in the disease, and a possible axon-specific function for SMN, should be further assessed in SMA mouse models.

Conclusions

SMA is a devastating disorder of the nervous system that predominantly affects very young children and has no available treatment. A number of key questions about causative pathways and disease pathology remain unresolved, and their clarification will help both to improve our general understanding of the disease mechanism but also crucially inform the development and optimization of novel therapeutic strategies. An abundance of studies have demonstrated that multiple mouse SMA models that mimic the broad spectrum of disease seen in patients and that allow conditional SMN expression are required to fully explore these complex issues. Owing to the great progress in furthering our basic biological understanding of SMA and the availability of appropriate preclinical models, this disease has been highlighted by the NIH and other funding bodies as being one of the neurogenetic diseases that is closest to being cured. A wide range of different therapeutic approaches – including viral-mediated gene delivery, small molecules that upregulate SMN expression, and oligonucleotide-mediated splicing modification – are now close to entering clinical trials. As these therapies approach clinical translation there will still be much to learn from mouse models about how to best apply these therapies for the benefit of patients.

Acknowledgments

Work in the K.T. laboratory is supported by grants from the SMA Trust and the Motor Neurone Disease Association. J.N.S. is funded by a Medical Research Council PhD Studentship. T.H.G. receives research funding from the Welcome Trust and the SMA Trust.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they do not have any competing or financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Anagnostou E., Miller S. P., Guiot M. C., Karpati G., Simard L., Dilenge M. E., Shevell M. I. (2005). Type I spinal muscular atrophy can mimic sensory-motor axonal neuropathy. J. Child Neurol. 20, 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Tanabe Y., Hachiya Y., Otsuka E., Kumada S., Furushima W., Kohyama J., Yamashita S., Takanashi J., Kohno Y. (2005). Finger cold-induced vasodilatation, sympathetic skin response, and R-R interval variation in patients with progressive spinal muscular atrophy. J. Child Neurol. 20, 871–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki S., Hayashi M., Tamagawa K., Saito M., Kato S., Komori T., Sakakihara Y., Mizutani T., Oda M. (2003). Neuropathological analysis in spinal muscular atrophy type II. Acta Neuropathol. 106, 441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo Ade Q., Araujo M., Swoboda K. J. (2009). Vascular perfusion abnormalities in infants with spinal muscular atrophy. J. Pediatr. 155, 292–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach J. R. (2007). Medical considerations of long-term survival of Werdnig-Hoffmann disease. Am J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86, 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanian S., Gendron N. H., MacKenzie A. E. (2007). Histologic and transcriptional assessment of a mild SMA model. Neurol. Res. 29, 413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäumer D., Lee S., Nicholson G., Davies J. L., Parkinson N. J., Murray L. M., Gillingwater T. H., Ansorge O., Davies K. E., Talbot K. (2009). Alternative splicing events are a late feature of pathology in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin A., Kim G., Price D. L., Sisodia S. S., Lee M. K., Rabin B. A. (1997). Identification and characterization of a mouse homologue of the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene, survival motor neuron. Gene 204, 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan A. K., Hutchinson K. R., Foust K. D., Braun L., McGovern V. L., Schmelzer L., Ward J. G., Petruska J. C., Lucchesi P. A., Burghes A. H., et al. (2010). Early heart failure in the SMNDelta7 model of spinal muscular atrophy and correction by postnatal scAAV9-SMN delivery. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 3895–3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi O., Grondard C., Lecolle S., Deforges S., Pariset C., Lopes P., Cifuentes-Diaz C., Li H., della Gaspera B., Chanoine C., et al. (2008). Exercise-induced activation of NMDA receptor promotes motor unit development and survival in a type 2 spinal muscular atrophy model mouse. J. Neurosci. 28, 953–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon K. L., Xiao S., McWhorter M. L., Donn T., Wolf-Saxon E., Bohnsack M. T., Moens C. B., Beattie C. E. (2009). Zebrafish survival motor neuron mutants exhibit presynaptic neuromuscular junction defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 3615–3625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman M., Anderson C. L., Beauvais A., Boyl P. P., Witke W., Kothary R. (2009). SMN, profilin IIa and plastin 3, a link between the deregulation of actin dynamics and SMA pathogenesis. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 42, 66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briese M., Esmaeili B., Sattelle D. B. (2005). Is spinal muscular atrophy the result of defects in motor neuron processes? BioEssays 27, 946–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briese M., Esmaeili B., Fraboulet S., Burt E. C., Christodoulou S., Towers P. R., Davies K. E., Sattelle D. B. (2009). Deletion of smn-1, the Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of the spinal muscular atrophy gene, results in locomotor dysfunction and reduced lifespan. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 97–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühler D., Raker V., Lührmann R., Fischer U. (1999). Essential role for the tudor domain of SMN in spliceosomal U snRNP assembly: implications for spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2351–2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlet P., Huber C., Bertrandy S., Ludosky M. A., Zwaenepoel I., Clermont O., Roume J., Delezoide A. L., Cartaud J., Munnich A., et al. (1998). The distribution of SMN protein complex in human fetal tissues and its alteration in spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol. Genet.. 7, 1927–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butchbach M. E., Edwards J. D., Burghes A. H. (2007). Abnormal motor phenotype in the SMNDelta7 mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 27, 207–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butchbach M. E., Singh J., Thorsteinsdottir M., Saieva L., Slominski E., Thurmond J., Andresson T., Zhang J., Edwards J. D., Simard L. R., et al. (2010). Effects of 2,4-diaminoquinazoline derivatives on SMN expression and phenotype in a mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 454–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. B., Miguel-Aliaga I., Franks C., Thomas N., Trülzsch B., Sattelle D. B., Davies K. E., van den Heuvel M. (2003). Neuromuscular defects in a Drosophila survival motor neuron gene mutant. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1367–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. C., Dimlich D. N., Yokokura T., Mukherjee A., Kankel M. W., Sen A., Sridhar V., Fulga T. A., Hart A. C., Van Vactor D., et al. (2008). Modeling spinal muscular atrophy in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 3, e3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Diaz C., Frugier T., Tiziano F. D., Lacene E., Roblot N., Joshi V., Moreau M. H., Melki J. (2001). Deletion of murine SMN exon 7 directed to skeletal muscle leads to severe muscular dystrophy. J. Cell. Biol. 152, 1107–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Diaz C., Nicole S., Velasco M. E., Borra-Cebrian C., Panozzo C., Frugier T., Millet G., Roblot N., Joshi V., Melki J. (2002). Neurofilament accumulation at the motor endplate and lack of axonal sprouting in a spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1439–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coovert D. D., Le T. T., McAndrew P. E., Strasswimmer J., Crawford T. O., Mendell J. R., Coulson S. E., Androphy E. J., Prior T. W., Burghes A. H. (1997). The survival motor neuron protein in spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 1205–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato C. J., Chen X. N., Noya D., Korenberg J. R., Nadeau J. H., Simard L. R. (1997). Cloning, characterization, and copy number of the murine survival motor neuron gene: homolog of the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Genome Res. 7, 339–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadi M., Sleigh J. N., Walker A., Chang H. C., Sen A., Kalloo G., Harris J., Barsby T., Walsh M. B., Satterlee J. S., et al. (2010). Conserved genes act as modifiers of invertebrate SMN loss of function defects. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez E., Marais T., Chatauret N., Benkhelifa-Ziyyat S., Duque S., Ravassard P., Carcenac R., Astord S., de Moura A. P., Voit T., et al. (2011). Intravenous scAAV9 delivery of a codon-optimized SMN1 sequence rescues SMA mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 681–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felderhoff-Mueser U., Grohmann K., Harder A., Stadelmann C., Zerres K., Bührer C., Obladen M. (2002). Severe spinal muscular atrophy variant associated with congenital bone fractures. J. Child Neurol. 17, 718–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldkötter M., Schwarzer V., Wirth R., Wienker T. F., Wirth B. (2002). Quantitative analyses of SMN1 and SMN2 based on real-time LightCycler PCR: fast and highly reliable carrier testing and prediction of severity of spinal muscular atrophy. Am J. Hum. Genet. 70, 358–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri A., Melki J., Kato A. C. (2004). Progressive and selective degeneration of motoneurons in a mouse model of SMA. NeuroReport 15, 275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J., Stöllberger C. (1999). Cardiac involvement in Werdnig-Hoffmann’s spinal muscular atrophy. Cardiology 92, 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer U., Liu Q., Dreyfuss G. (1997). The SMN-SIP1 complex has an essential role in spliceosomal snRNP biogenesis. Cell 90, 1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust K. D., Nurre E., Montgomery C. L., Hernandez A., Chan C. M., Kaspar B. K. (2009). Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust K. D., Wang X., McGovern V. L., Braun L., Bevan A. K., Haidet A. M., Le T. T., Morales P. R., Rich M. M., Burghes A. H., et al. (2010). Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 271–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Fox-Walsh K. L., Hertel K. J. (2009). Splice-site pairing is an intrinsically high fidelity process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1766–1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frugier T., Tiziano F. D., Cifuentes-Diaz C., Miniou P., Roblot N., Dierich A., Le Meur M., Melki J. (2000). Nuclear targeting defect of SMN lacking the C-terminus in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 849–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabanella F., Carissimi C., Usiello A., Pellizzoni L. (2005). The activity of the spinal muscular atrophy protein is regulated during development and cellular differentiation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 3629–3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabanella F., Butchbach M. E., Saieva L., Carissimi C., Burghes A. H., Pellizzoni L. (2007). Ribonucleoprotein assembly defects correlate with spinal muscular atrophy severity and preferentially affect a subset of spliceosomal snRNPs. PLoS ONE 2, e921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogliotti R. G., Hammond S. M., Lutz C., Didonato C. J. (2010). Molecular and phenotypic reassessment of an infrequently used mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachiya Y., Arai H., Hayashi M., Kumada S., Furushima W., Ohtsuka E., Ito Y., Uchiyama A., Kurata K. (2005). Autonomic dysfunction in cases of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 with long survival. Brain Dev. 27, 574–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. M., Gogliotti R. G., Rao V., Beauvais A., Kothary R., Didonato C. J. (2010). Mouse survival motor neuron alleles that mimic SMN2 splicing and are inducible rescue embryonic lethality early in development but not late. PLoS ONE 5, e15887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M., Arai N., Murakami T., Yoshio M., Oda M., Matsuyama H. (1998). A study of cell death in Werdnig Hoffmann disease brain. Neurosci. Lett. 243, 117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heier C. R., Satta R., Lutz C., DiDonato C. J. (2010). Arrhythmia and cardiac defects are a feature of spinal muscular atrophy model mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 3906–3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh-Li H. M., Chang J. G., Jong Y. J., Wu M. H., Wang N. M., Tsai C. H., Li H. (2000). A mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Genet. 24, 66–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y., Sahashi K., Hung G., Rigo F., Passini M. A., Bennett C. F., Krainer A. R. (2010). Antisense correction of SMN2 splicing in the CNS rescues necrosis in a type III SMA mouse model. Genes Dev. 24, 1634–1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Kumada S., Uchiyama A., Saito K., Osawa M., Yagishita A., Kurata K., Hayashi M. (2004). Thalamic lesions in a long-surviving child with spinal muscular atrophy type I: MRI and EEG findings. Brain Dev. 26, 53–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka S., Schrank B., Kralewski M., Rossoll W., Sendtner M. (2000). Reduced survival motor neuron (Smn) gene dose in mice leads to motor neuron degeneration: an animal model for spinal muscular atrophy type III. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka S., Bandilla M., Wiese S., Bühler D., Wirth B., Sendtner M., Fischer U. (2001). Co-regulation of survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein and its interactor SIP1 during development and in spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 10, 497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka S., Holtmann B., Meister G., Bandilla M., Rossoll W., Fischer U., Sendtner M. (2002). Gene targeting of Gemin2 in mice reveals a correlation between defects in the biogenesis of U snRNPs and motoneuron cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10126–10131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka S., Karle K., Sandner B., Andreassi C., von Au K., Sendtner M. (2006). Distinct and overlapping alterations in motor and sensory neurons in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka S., Beck M., Lechner B. D., Mayer C., Sendtner M. (2007). Defective Ca2+ channel clustering in axon terminals disturbs excitability in motoneurons in spinal muscular atrophy. J. Cell. Biol. 179, 139–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya S., Park G. H., Maeno-Hikichi Y., Leykekhman O., Lutz C., Arkovitz M. S., Landmesser L. T., Monani U. R. (2008). Reduced SMN protein impairs maturation of the neuromuscular junctions in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2552–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya S., Mauricio R., Dai Y., Monani U. R. (2009). The neuroprotective factor Wld(s) fails to mitigate distal axonal and neuromuscular junction (NMJ) defects in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurosci. Lett. 449, 246–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly T. E., Amoroso K., Ferre M., Blanco J., Allinson P., Prior T. W. (1999). Spinal muscular atrophy variant with congenital fractures. Am J. Med. Genet.. 87, 65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D. A., Nery J. P., Traystman R. J., Chau B. N., Hardwick J. M. (2000). Survival motor neuron protein modulates neuron-specific apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13312–13317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri I. A., Chaudhry U. S., Seikaly M. G., Browne R. H., Iannaccone S. T. (2008). Low bone mineral density in spinal muscular atrophy. J Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 10, 11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja K., Houlsby W. T., Watson S., Bushby K., Cheetham T. (2004). Hypercalcaemia in infancy; a presenting feature of spinal muscular atrophy. Arch. Dis. Child. 89, 384–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Wang X., Choe D. W., Polley M., Burnett B. G., Bosch-Marcé M., Griffin J. W., Rich M. M., Sumner C. J. (2009). Impaired synaptic vesicle release and immaturity of neuromuscular junctions in spinal muscular atrophy mice. J. Neurosci. 29, 842–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinthenberg R., Sauer M., Ketelsen U. P., Hanemann C. O., Stoll G., Graf M., Baborie A., Volk B., Wirth B., Rudnik-Schöneborn S., et al. (1997). Congenital axonal neuropathy caused by deletions in the spinal muscular atrophy region. Ann. Neurol.. 42, 364–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T. T., Pham L. T., Butchbach M. E., Zhang H. L., Monani U. R., Coovert D. D., Gavrilina T. O., Xing L., Bassell G. J., Burghes A. H. (2005). SMNDelta7, the major product of the centromeric survival motor neuron (SMN2) gene, extends survival in mice with spinal muscular atrophy and associates with full-length SMN. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 14, 845–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S., Burglen L., Reboullet S., Clermont O., Burlet P., Viollet L., Benichou B., Cruaud C., Millasseau P., Zeviani M., et al. (1995). Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell 80, 155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S., Burlet P., Liu Q., Bertrandy S., Clermont O., Munnich A., Dreyfuss G., Melki J. (1997). Correlation between severity and SMN protein level in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Genet. 16, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling K. K., Lin M. Y., Zingg B., Feng Z., Ko C. P. (2010). Synaptic defects in the spinal and neuromuscular circuitry in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS ONE 5, e15457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Shafey D., Moores J. N., Kothary R. (2010). Neurodevelopmental consequences of Smn depletion in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Beauvais A., Baker A. N., Tsilfidis C., Kothary R. (2011). Smn deficiency causes neuritogenesis and neurogenesis defects in the retinal neurons of a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Dev. Neurobiol. 71, 153–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Fischer U., Wang F., Dreyfuss G. (1997). The spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, SMN, and its associated protein SIP1 are in a complex with spliceosomal snRNP proteins. Cell 90, 1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorson C. L., Androphy E. J. (2000). An exonic enhancer is required for inclusion of an essential exon in the SMA-determining gene SMN Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorson C. L., Hahnen E., Androphy E. J., Wirth B. (1999). A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6307–6311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailman M. D., Heinz J. W., Papp A. C., Snyder P. J., Sedra M. S., Wirth B., Burghes A. H., Prior T. W. (2002). Molecular analysis of spinal muscular atrophy and modification of the phenotype by SMN2 Genet. Med. 4, 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew P. E., Parsons D. W., Simard L. R., Rochette C., Ray P. N., Mendell J. R., Prior T. W., Burghes A. H. (1997). Identification of proximal spinal muscular atrophy carriers and patients by analysis of SMNT and SMNC gene copy number. Am J. Hum. Genet. 60, 1411–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern V. L., Gavrilina T. O., Beattie C. E., Burghes A. H. (2008). Embryonic motor axon development in the severe SMA mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2900–2909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWhorter M. L., Monani U. R., Burghes A. H., Beattie C. E. (2003). Knockdown of the survival motor neuron (Smn) protein in zebrafish causes defects in motor axon outgrowth and pathfinding. J. Cell Biol. 162, 919–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G., Bühler D., Pillai R., Lottspeich F., Fischer U. (2001). A multiprotein complex mediates the ATP-dependent assembly of spliceosomal U snRNPs. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 945–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentis G. Z., Blivis D., Liu W., Drobac E., Crowder M. E., Kong L., Alvarez F. J., Sumner C. J., O’Donovan M. J. (2011). Early functional impairment of sensory-motor connectivity in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neuron 69, 453–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K., Marquis J., Trub J., Nlend Nlend R., Verp S., Ruepp M. D., Imboden H., Barde I., Trono D., Schümperli D. (2009). Rescue of a severe mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy by U7 snRNA-mediated splicing modulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 546–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud M., Arnoux T., Bielli S., Durand E., Rotrou Y., Jablonka S., Robert F., Giraudon-Paoli M., Riessland M., Mattei M. G., et al. (2010). Neuromuscular defects and breathing disorders in a new mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 38, 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monani U. R., Lorson C. L., Parsons D. W., Prior T. W., Androphy E. J., Burghes A. H., McPherson J. D. (1999). A single nucleotide difference that alters splicing patterns distinguishes the SMA gene SMN1 from the copy gene SMN2. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 8, 1177–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monani U. R., Sendtner M., Coovert D. D., Parsons D. W., Andreassi C., Le T. T., Jablonka S., Schrank B., Rossoll W., Prior T. W., et al. (2000). The human centromeric survival motor neuron gene (SMN2) rescues embryonic lethality in Smn−/− mice and results in a mouse with spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 9, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monani U. R., Pastore M. T., Gavrilina T. O., Jablonka S., Le T. T., Andreassi C., DiCocco J. M., Lorson C., Androphy E. J., Sendtner M., et al. (2003). A transgene carrying an A2G missense mutation in the SMN gene modulates phenotypic severity in mice with severe (type I) spinal muscular atrophy. J. Cell Biol. 160, 41–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. M., Comley L. H., Thomson D., Parkinson N., Talbot K., Gillingwater T. H. (2008). Selective vulnerability of motor neurons and dissociation of pre- and post-synaptic pathology at the neuromuscular junction in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 17, 949–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. M., Talbot K., Gillingwater T. H. (2010a). Neuromuscular synaptic vulnerability in motor neurone disease: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and spinal muscular atrophy. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol.. 36, 133–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. M., Lee S., Bäumer D., Parson S. H., Talbot K., Gillingwater T. H. (2010b). Pre-symptomatic development of lower motor neuron connectivity in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 19, 420–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narver H. L., Kong L., Burnett B. G., Choe D. W., Bosch-Marcé M., Taye A. A., Eckhaus M. A., Sumner C. J. (2008). Sustained improvement of spinal muscular atrophy mice treated with trichostatin A plus nutrition. Ann. Neurol.. 64, 465–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicole S., Desforges B., Millet G., Lesbordes J., Cifuentes-Diaz C., Vertes D., Cao M. L., De Backer F., Languille L., Roblot N., et al. (2003). Intact satellite cells lead to remarkable protection against Smn gene defect in differentiated skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 161, 571–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka A., Matsushita Y., Sakakihara Y., Momose T., Yanaginasawa M. (1995). Spinal muscular atrophy with oculomotor palsy, epilepsy, and cerebellar hypoperfusion. Pediatr. Neurol. 12, 365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omran H., Ketelsen U. P., Heinen F., Sauer M., Rudnik-Schöneborn S., Wirth B., Zerres K., Kratzer W., Korinthenberg R. (1998). Axonal neuropathy and predominance of type II myofibers in infantile spinal muscular atrophy. J. Child Neurol. 13, 327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park G. H., Maeno-Hikichi Y., Awano T., Landmesser L. T., Monani U. R. (2010). Reduced survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein in motor neuronal progenitors functions cell autonomously to cause spinal muscular atrophy in model mice expressing the human centromeric (SMN2) gene. J. Neurosci. 30, 12005–12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passini M. A., Bu J., Roskelley E. M., Richards A. M., Sardi S. P., O’Riordan C. R., Klinger K. W., Shihabuddin L. S., Cheng S. H. (2010). CNS-targeted gene therapy improves survival and motor function in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 1253–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passini M. A., Bu J., Richards A. M., Kinnecom C., Sardi S. P., Stanek L. M., Hua Y., Rigo F., Matson J., Hung G., et al. (2011). Antisense oligonucleotides delivered to the mouse CNS ameliorate symptoms of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 72ra18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A. A., Steitz J. A. (2003). Splicing double: insights from the second spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 960–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearn J. (1978). Incidence, prevalence, and gene frequency studies of chronic childhood spinal muscular atrophy. J. Med. Genet. 15, 409–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L. (2007). Chaperoning ribonucleoprotein biogenesis in health and disease. EMBO Rep. 8, 340–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L., Charroux B., Dreyfuss G. (1999). SMN mutants of spinal muscular atrophy patients are defective in binding to snRNP proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11167–11172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L., Yong J., Dreyfuss G. (2002). Essential role for the SMN complex in the specificity of snRNP assembly. Science 298, 1775–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendra T. K., Gonsalvez G. B., Walker M. P., Shpargel K. B., Salz H. K., Matera A. G. (2007). A Drosophila melanogaster model of spinal muscular atrophy reveals a function for SMN in striated muscle. J. Cell Biol. 176, 831–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riessland M., Ackermann B., Forster A., Jakubik M., Hauke J., Garbes L., Fritzsche I., Mende Y., Blumcke I., Hahnen E., et al. (2010). SAHA ameliorates the SMA phenotype in two mouse models for spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 19, 1492–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossoll W., Bassell G. J. (2009). Spinal muscular atrophy and a model for survival of motor neuron protein function in axonal ribonucleoprotein complexes. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 48, 289–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossoll W., Jablonka S., Andreassi C., Kroning A. K., Karle K., Monani U. R., Sendtner M. (2003). Smn, the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene product, modulates axon growth and localization of beta-actin mRNA in growth cones of motoneurons. J. Cell Biol. 163, 801–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnik-Schöneborn S., Goebel H. H., Schlote W., Molaian S., Omran H., Ketelsen U., Korinthenberg R., Wenzel D., Lauffer H., Kreiss-Nachtsheim M., et al. (2003). Classical infantile spinal muscular atrophy with SMN deficiency causes sensory neuronopathy. Neurology 60, 983–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnik-Schöneborn S., Heller R., Berg C., Betzler C., Grimm T., Eggermann T., Eggermann K., Wirth R., Wirth B., Zerres K. (2008). Congenital heart disease is a feature of severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy. J. Med. Genet. 45, 635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz R., Casanas J. J., Torres-Benito L., Cano R., Tabares L. (2010). Altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in nerve terminals of severe spinal muscular atrophy mice. J. Neurosci. 30, 849–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauterer R. A., Feeney R. J., Zieve G. W. (1988). Cytoplasmic assembly of snRNP particles from stored proteins and newly transcribed snRNA’s in L929 mouse fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 176, 344–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrank B., Götz R., Gunnersen J. M., Ure J. M., Toyka K. V., Smith A. G., Sendtner M. (1997). Inactivation of the survival motor neuron gene, a candidate gene for human spinal muscular atrophy, leads to massive cell death in early mouse embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9920–9925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shababi M., Habibi J., Yang H. T., Vale S. M., Sewell W. A., Lorson C. L. (2010). Cardiac defects contribute to the pathology of spinal muscular atrophy models. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 19, 4059–4071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafey D., MacKenzie A. E., Kothary R. (2008). Neurodevelopmental abnormalities in neurosphere-derived neural stem cells from SMN-depleted mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 86, 2839–2847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugarajan S., Swoboda K. J., Iannaccone S. T., Ries W. L., Maria B. L., Reddy S. V. (2007). Congenital bone fractures in spinal muscular atrophy: functional role for SMN protein in bone remodeling. J. Child Neurol. 22, 967–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugarajan S., Tsuruga E., Swoboda K. J., Maria B. L., Ries W. L., Reddy S. V. (2009). Bone loss in survival motor neuron (Smn−/−SMN2) genetic mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J. Pathol. 219, 52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishikura K., Hara M., Sasaki Y., Misugi K. (1983). A neuropathologic study of Werdnig-Hoffmann disease with special reference to the thalamus and posterior roots. Acta. Neuropathol. 60, 99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpargel K. B., Matera A. G. (2005). Gemin proteins are required for efficient assembly of Sm-class ribonucleoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 17372–17377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleigh J. N., Sattelle D. B. (2010). C. elegans models of neuromuscular diseases expedite translational research. Transl. Neurosci. 1, 214–227 [Google Scholar]

- Sleigh J. N., Buckingham S. D., Esmaeili B., Viswanathan M., Cuppen E., Westlund B. M., Sattelle D. B. (2011). A novel Caenorhabditis elegans allele, smn-1(cb131), mimicking a mild form of spinal muscular atrophy, provides a convenient drug screening platform highlighting new and pre-approved compounds. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 20, 245–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner C. J. (2007). Molecular mechanisms of spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 22, 979–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B. J., Parkinson N. J., Davies K. E., Talbot K. (2009). Survival motor neuron deficiency enhances progression in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 511–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valori C. F., Ning K., Wyles M., Mead R. J., Grierson A. J., Shaw P. J., Azzouz M. (2010). Systemic delivery of scAAV9 expressing SMN prolongs survival in a model of spinal muscular atrophy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 35ra42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viollet L., Bertrandy S., Bueno Brunialti A. L., Lefebvre S., Burlet P., Clermont O., Cruaud C., Guenet J. L., Munnich A., Melki J. (1997). cDNA isolation, expression, and chromosomal localization of the mouse survival motor neuron gene (Smn). Genomics 40, 185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitte J. M., Davoult B., Roblot N., Mayer M., Joshi V., Courageot S., Tronche F., Vadrot J., Moreau M. H., Kemeny F., et al. (2004). Deletion of murine Smn exon 7 directed to liver leads to severe defect of liver development associated with iron overload. Am J. Pathol. 165, 1731–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt T., Meyer K., Baum O., Schümperli D. (2010). Ultrastructural changes in diaphragm neuromuscular junctions in a severe mouse model for Spinal Muscular Atrophy and their prevention by bifunctional U7 snRNA correcting SMN2 splicing. Neuromuscul. Disord. 20, 744–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L., Battle D. J., Yong J., Gubitz A. K., Kolb S. J., Wang J., Dreyfuss G. (2005). The survival of motor neurons protein determines the capacity for snRNP assembly: biochemical deficiency in spinal muscular atrophy. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 5543–5551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund B., Stilwell G., Sluder A. (2004). Invertebrate disease models in neurotherapeutic discovery. Curr. Opin. Drug. Discov. Devel. 7, 169–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C., Eggert C., Gradl D., Meister G., Giegerich M., Wedlich D., Laggerbauer B., Fischer U. (2005). Reduced U snRNP assembly causes motor axon degeneration in an animal model for spinal muscular atrophy. Genes Dev. 19, 2320–2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart T. M., Huang J. P., Murray L. M., Lamont D. J., Mutsaers C. A., Ross J., Geldsetzer P., Ansorge O., Talbot K., Parson S. H., et al. (2010). SMN deficiency disrupts brain development in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 19, 4216–4228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman E., Saieva L., Carrel T. L., Crawford T. O., Liu D., Lutz C., Beattie C. E., Pellizzoni L., Burghes A. H. (2009). A SMN missense mutation complements SMN2 restoring snRNPs and rescuing SMA mice. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 18, 2215–2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannan M., Patel P., Kolawole T., Malabarey T., Mahdi A. (1991). Brain atrophy in Werdnig-Hoffmann disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 84, 426–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Robinson N., Wu C., Wang W., Harrington M. A. (2010). Electrophysiological properties of motor neurons in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy: in vitro versus in vivo development. PLoS ONE 5, e11696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Lotti F., Dittmar K., Younis I., Wan L., Kasim M., Dreyfuss G. (2008). SMN deficiency causes tissue-specific perturbations in the repertoire of snRNAs and widespread defects in splicing. Cell 133, 585–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]