Abstract

A negative phototransduction feedback in rods and cones is critical for the timely termination of their light responses and for extending their function to a wide range of light intensities. The calcium feedback mechanisms that modulate phototransduction in rods have been studied extensively. However, the corresponding modulation mechanisms that enable cones to terminate rapidly their light responses and to adapt in bright light, properties critical for our daytime vision, are still not understood. In cones, calcium feedback to guanylyl cyclase is potentially a key step in phototransduction modulation. The guanylyl cyclase activity is modulated by the calcium-binding guanylyl cyclase activating proteins (GCAP1 and GCAP2). Here, we used single-cell and transretinal recordings from mouse to determine how GCAPs modulate dark-adapted responses as well as light adaptation in mammalian cones. Deletion of GCAPs increased threefold the amplitude and dramatically prolonged the light responses in dark-adapted mouse cones. It also reduced the operating range of mouse cones in background illumination and severely impaired their light adaptation. Thus, GCAPs exert powerful modulation on the mammalian cone phototransduction cascade and play an important role in setting the functional properties of cones in darkness and during light adaptation. Surprisingly, despite their better adaptation capacity and wider calcium dynamic range, mammalian cones were modulated by GCAPs to a lesser extent than mammalian rods. We conclude that a disparity in the strength of GCAP modulation cannot explain the differences in the dark-adapted properties or in the operating ranges of mammalian rods and cones.

Introduction

Rod and cone photoreceptors respond to >10 logarithmic units of light intensities. Our ability to see over this enormous range can be explained, in part, by adaptation within rods and cones. Although the adaptation mechanisms that modulate rod phototransduction have been studied extensively (Burns and Arshavsky, 2005), the mechanisms that enable cones to adapt are poorly understood. Cone transduction proteins are homologous or identical to the ones found in rods, and the cone phototransduction cascade is believed to function similarly to the one in rods (Ebrey and Koutalos, 2001). Remarkably, whereas rods saturate in moderately bright light (Green, 1971), cones can adjust their sensitivity and remain photosensitive even in bright light (Boynton and Whitten, 1970).

In both rods and cones, adaptation is modulated by changes in intracellular Ca2+. In darkness, the continuous current entering the outer segment through the cGMP-gated channels is carried in part by Ca2+, which is returned to the extracellular space via a Na+/(Ca2+, K+) exchanger. After photoactivation and the closure of cGMP channels, the concentration of Ca2+ in the outer segment declines. This triggers a Ca2+-mediated negative feedback on phototransduction, which in rods mediates response shutoff and adaptation (Fain et al., 2001; Nakatani et al., 2002). Interestingly, Ca2+ constitutes a larger fraction of the total outer segment ionic flux in cones (20–35%) compared with rods (10–20%) (Korenbrot, 1995; Korenbrot and Rebrik, 2002). This attribute, in combination with the smaller outer segments of cones, allows their intracellular Ca2+ to decline several times faster during light stimulation than that in rods (Sampath et al., 1999). In addition, the dynamic range of Ca2+ in cones is threefold larger than that in rods (Korenbrot, 1995; Sampath et al., 1998, 1999). Although these quantitative differences create the potential for stronger phototransduction modulation by Ca2+ in cones compared with rods, this issue has not been examined experimentally.

A key mechanism by which Ca2+ modulates phototransduction in rods involves the synthesis of cGMP by guanylyl cyclase (GC), regulated by a pair of Ca2+-binding guanylyl cyclase activating proteins (GCAP1 and GCAP2) (Koch and Stryer, 1988; Burns et al., 2002). In rods, GCAPs modulate GC up to 20-fold, inhibiting it at high Ca2+ and activating it at low Ca2+ levels (Palczewski et al., 2000). The deletion of GCAPs in mouse rods abolishes the Ca2+ feedback on GC and results in slowed photoresponse shutoff and impaired light adaptation (Mendez et al., 2001; Burns et al., 2002). Electroretinogram (ERG) recordings have provided an initial evidence for modulation of cone-driven bipolar cell responses by GCAPs (Pennesi et al., 2003). However, the effectiveness of GCAPs in modulating light response kinetics and sensitivity or their effect on light adaptation in mammalian cones has not been assessed. Here we addressed these questions by comparing the flash responses from control and GCAPs−/− mouse cones. Surprisingly, we found that, whereas GCAPs strongly modulate cone sensitivity and response kinetics, the Ca2+ modulation on guanylyl cyclase is weaker in cones than in rods both in darkness and during light adaptation.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

GCAP knock-out mice (GCAPs−/−) (Mendez et al., 2001) of either sex were used after at least 12 h dark adaptation. To facilitate suction recordings and to remove the rod component in the response of transretinal electroretinogram, all recordings for cones were done from mice in rod transducin α (rTα) knock-out (Gnat1−/−) background (Calvert et al., 2000), generously provided by Janis Lem, Tufts University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Western blot analysis.

Retinas were dissected from mice at P30, homogenized in buffer [80 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mm MgCl2, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics), and 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], and incubated with DNase I (Roche Diagnostics) for 30–45 min at room temperature. Equal volume of protein sample loading buffer (100 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 0.2 m dithiothreitol, 8% SDS, 20% glycerol, and a dash of bromophenol blue) was added, and the equivalent amounts of protein were loaded and separated in Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen). The protein samples then were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman Schleicher & Schuell) and were incubated with polyclonal antibodies against GCAP1, GCAP2, mouse green opsin (mGO), and rod transducin. The signal was detected using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System from LI-COR Biosciences.

Immunofluorescence.

All mice were killed at P30. Before enucleation, the superior pole for each mouse eye was cauterized for orientation. The mouse eye was placed in fixative solution (4.0% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2). The cornea and lens were removed, and the remaining eyecup was further fixed for 2 h and rinsed free of fixative with 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2. The tissues were infiltrated with 30% sucrose in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer for 14–18 h at 4°C and embedded in Tissue Tek O.C.T. (Sakura Kinetek), and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ten micrometer frozen sections were obtained with a Jung CM 3000 cryostat machine (Leica). The retinal sections were incubated for 1 h in blocking solution (2.0% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 2% goat serum in PBS). This blocking solution was also used in all subsequent antibody incubation steps. Some sections were incubated with mouse cone arrestin antibody (LUMI-J) (Zhu et al., 2002). After washing with blocking solution, the sections were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories). Other sections were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated peanut agglutinin (Vector Laboratories). After a series of washing and a short fix (5 min in 4.0% paraformaldehyde in PBS), the sections were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories), coverslipped, and analyzed with an AxioPlan 2 imaging microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Electrophysiology.

We performed single-cell suction recordings from individual cones and transretinal ERG recordings from isolated whole retina. Mice were maintained in 12/12 h light/dark cycle and dark adapted overnight before experiments. After the animals were killed, eyes were marked for orientation, removed under dim red light, and hemisected, and retinas were isolated under infrared light. For single-cell recordings, the dorsal part of retina was isolated, sliced with a razor blade, and stored in Locke solution at 4°C. Recordings were done from small pieces of retina placed in a recording chamber fit to an inverted microscope and perfused at ∼37°C. The perfusion Locke solution contained 112 mm NaCl, 3.6 mm KCl, 2.4 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 20 mm NaHCO3, 3 mm Na2-succinate, 0.5 mm Na-glutamate, and 10 mm glucose and was equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4. For cones, recordings were done by drawing the cell body of a single photoreceptor into the recording electrode as described previously (Nikonov et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2007). The suction electrode was filled with solution containing 140 mm NaCl, 3.6 mm KCl, 2.4 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm CaCl2, 3 mm HEPES, and 10 mm glucose, pH 7.4. Responses were amplified by a current-to-voltage converter (Axopatch 200B; Molecular Devices), low-pass filtered by an eight-pole Bessel filter (Krohn-Hite) with a cutoff frequency of 30 Hz, digitized at 1 kHz, and stored on a computer using pClamp 8.2 acquisition software (Molecular Devices). For BAPTA experiments, the retina was treated with Locke solution containing 100 μm BAPTA-AM for 20 min at room temperature.

For transretinal recordings, a quarter of the isolated dorsal retina was mounted on filter paper, photoreceptor-side up, and placed on the recording chamber with an electrode connected to the bottom. A second electrode was placed above the retina. To increase retina stability and the duration of recordings, the perfusion solution was kept at slightly lower temperature, ∼34°C, than for single-cell recordings. The perfusion Locke solution contained 2 mm l-glutamic acid to block higher-order components of photoresponse (Sillman et al., 1969). The electrode solution under the retina contained, in addition, 10 mm BaCl2 to suppress the glial component (Bolnick et al., 1979; Nymark et al., 2005). Responses were amplified by a differential amplifier (DP-311; Warner Instruments). Saturated M-cone transretinal photoresponses were obtained using white light through a long-pass filter (>410 nm; Edmund GG455).

For all recordings and for all figures, test flashes were given at t = 0. Normalized flash sensitivity, SF, was calculated as the ratio of dim-flash response amplitude and flash intensity normalized by the saturated dark-adapted response for each retina. Intensity–response data were fit by the following equation:

where R is the transient-peak amplitude of response, Rmax is maximal response amplitude, I is flash intensity, and Io is the flash intensity to generate half-maximal response.

The fractional amplitude of residual response in background illumination was fitted with Hill equation as follows:

where Rmax is a maximal response amplitude in background illumination, Rmax,dark is the maximal response amplitude in darkness, IB (photons μm−2 s−1) is the background light intensity, IR (photons μm−2 s−1) is the background light intensity required to reduce the amplitude twofold, and k is the Hill coefficient.

The decline in photoreceptor sensitivity in background light was fit by the Weber–Fechner equation:

where SF is photoreceptor sensitivity in background light, SFD is photoreceptor sensitivity in darkness, IB (photons μm−2 s−1) is the background light intensity, and IS (photons μm−2 s−1) is the background light intensity required to reduce sensitivity twofold.

The expected exponential decline in sensitivity or residual maximal response in background, IB, in the absence of adaptation was described as follows:

where Ti (s) is the integration time of the dark-adapted response.

Estimation of collecting areas of cones.

For suction recordings, as described previously (Baylor et al., 1979; Nikonov et al., 2005), the effective collecting area ac(λ) of the mouse cone for a flash of λ nm is given by the following equation:

where f is a factor allowing for the use of unpolarized light entering the outer segment perpendicular to its axis (f = 0.75), ε(λ)(m−1 cm−1) is the extinction coefficient of M-opsin at a given wavelength λ (nm) of the pigment in solution, γ is the quantum efficiency of photoisomerization, C(M) is the pigment concentration in the outer segment, and d (μm) and lcone (μm) are the diameter and length of the outer segment. For M-opsin, ε(500) and γ of M-opsin are 43,900 m−1 cm−1 and 0.61 (Sakurai et al., 2007), and the pigment concentration, C, is 3.2 × 10−3 m (Hárosi, 1982). The cone outer segment has a base of 1.2 μm diameter, a tip of 0.8 μm diameter, and a length of 13.4 μm (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979). Thus, the estimated cone outer segment volume is 10.5 μm3 assuming that its shape is equivalent to a cylinder with a diameter of 1.0 μm. Combining these values, the collection area, ac(500), of M-cones in our recording configuration is calculated as 0.16 μm2.

For transretinal recordings, the effective collecting area Ac(λ) of mouse M-cone for flash of λ nm is given by the following equation:

where d (μm) and lcone (μm) are the diameter and length of the outer segments, respectively, kf is a coefficient of funneling light effect (kf = 1), and kshadow denotes a coefficient, which represents the shadow effect of rod outer segments (Heikkinen et al., 2008). Because the retina was placed on the chamber with photoreceptor-side up, the shadow coefficient can be defined as kshadow = 10−(lrod−lcone)εrod(500)C×10−4, where lrod (23.6 μm) and lcone (13.4 μm) are the lengths of rod and cone outer segment, respectively. The molar extinction coefficient of mouse rhodopsin at 500 nm, εrod(500), is 40,200 m−1 cm−1 (Imai et al., 2007). Thus, kshadow can be estimated as 0.74 at 500 nm light. Our experiments were done using dorsal mouse retina, in which M cones are dominant (Applebury et al., 2000). Assuming that transretinal photoresponses to green monochromatic light (500 nm) are derived from M-cones, we estimated Ac(500) to be 0.12 μm2.

Results

GCAPs−/−, Gnat1−/− retina contains a normal complement of cones

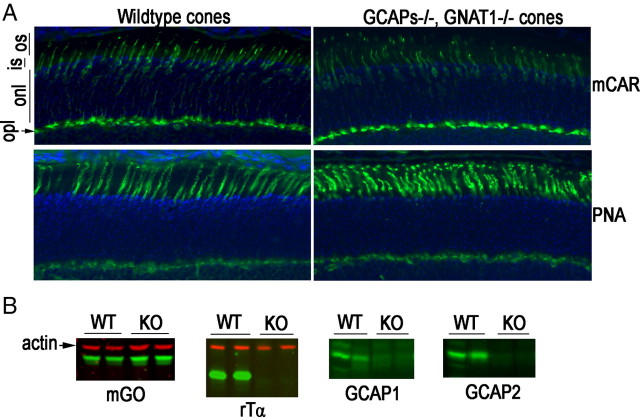

GCAPs−/− mice (Mendez et al., 2001) were crossed with the Gnat1−/− mice lacking the α-subunit of rod transducin to facilitate the isolation of cone responses. The deletion of transducin renders the rods unable to respond to light but preserves the structure of rods and the morphology of the retina (Calvert et al., 2000). Because both transducin and GCAPs are abundantly expressed in rod photoreceptors, we performed light microscopy on plastic-embedded sections to evaluate whether the absence of these proteins affected retinal morphology. No changes were detected in the thickness of retinal layers and outer segment length (data not shown). We then performed immunocytochemistry on frozen sections to determine whether the knock-outs had a deleterious effect on cones. Retinal sections from wild-type and knock-out mice were reacted with mouse cone arrestin antibody (Nikonov et al., 2005) or peanut agglutinin, both of which label cones specifically (Fig. 1A). The labeled cones showed similar density and outer segment morphology, and no difference was observed with respect to the number of cones counted in retinal sections that contain the entire span of retina along the vertical meridian (wild type, 670 ± 10, n = 3; knock-out, 650 ± 10, n = 3; mean ± SEM). In addition, the level of mGO, another cone marker, was similar in retinal extracts from wild-type and knock-out mice (Fig. 1B). The absence of rTα and the GCAP proteins in the knock-out mice was confirmed by Western blots (Fig. 1B). Thus, removal of GCAPs and rod transducin had no discernable effect on cone morphology and on the expression of cone markers. This allowed us to use animals of rod transducin knock-out background (Gnat1−/−) to perform cone recordings as described previously (Nikonov et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2007) from control and GCAPs-deficient (GCAPs−/−) animals.

Figure 1.

Cone density and expression of transduction proteins in wild-type and GCAPs−/−,Gnat1−/− retina. Cones were visualized by immunofluorescence (green) (A) of mouse cone arrestin (mCAR, top) and peanut agglutinin (PNA, bottom). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). os, Outer segment; is, inner segment; onl, outer nuclear layer; opl, outer plexiform layer. B, Representative Western blots of whole retinal homogenate from wild-type (WT) and GCAPs−/−, Gnat1−/− (KO) mice probed with antibodies against the indicated transduction protein (mGO, rTα, GCAP1, and GCAP2). Actin served as a loading control. Each lane contains retinal homogenate from a different mouse. No changes in expression level of mouse green opsin were observed.

GCAPs modulate the kinetics and sensitivity of single-cell cone responses

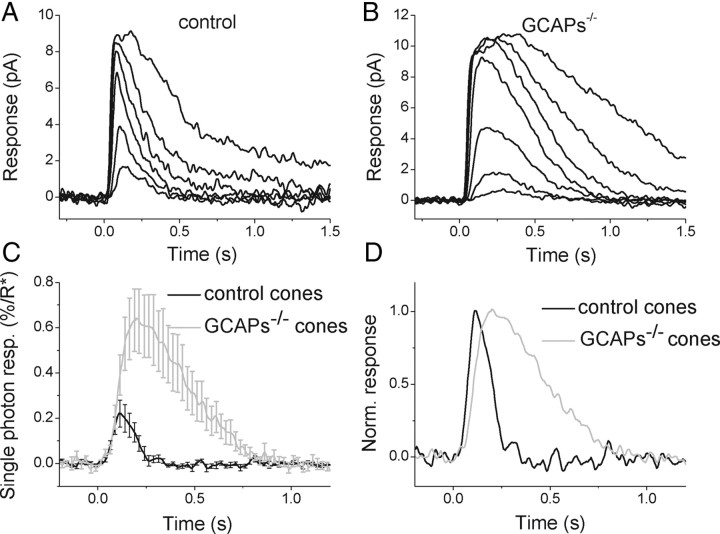

We began characterizing the role of GCAPs in mammalian cone phototransduction by investigating how their deletion affects the responses of mouse cones in dark-adapted conditions. To do that, we recorded suction electrode photoresponses to 500 nm test flashes from single M-cones selected from the dorsal retina in Gnat1−/− mice (control cones) and in Gnat1−/− mice also lacking GCAPs (GCAPs−/− cones). Typical flash response families from control and GCAPs−/− cones are shown in Figure 2, A and B. The rising phase of the dim flash response in GCAPs−/− cones was not noticeably different from that in control cones (Fig. 2C), suggesting that GCAPs do not modulate the activation steps of cone phototransduction. However, the deletion of GCAPs had a dramatic effect on the kinetics of response shutoff. The lack of GCAPs delayed the onset of recovery (Fig. 2C,D) and increased the time-to-peak of mouse cone dim-flash responses by twofold, from 112 ± 4 ms in control cones to 221 ± 9 ms in GCAPs−/− cones, respectively (Table 1). The effect of GCAPs deletion on the dim-flash integration time was even more dramatic because this parameter increased 3.3-fold, from 112 ± 10 ms in control cones to 374 ± 23 ms in GCAPs−/− cones, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flash response families of dark-adapted control (A) and GCAPs−/− (B) M-cones recorded with a suction electrode. Cone responses were evoked by a series of 500 nm test flashes (10 ms in duration). The test flash intensities (in photons μm−2) were 500, 1.4 × 103, 5.7 × 103, 1.9 × 104, 5.2 × 104, and 1.7 × 105 for control cones and 180, 500, 1.4 × 103, 5.7 × 103, 1.9 × 104, 5.2 × 104, and 1.7 × 105 for GCAPs−/− cones. C, Averaged single-photon responses of control (black, n = 12) and GCAPs−/− (gray, n = 16) cones. Error bars show SEM. To calculate the number of R*, the collecting area of cones was estimated to be 0.16 μm2 (for details, see Eq. 5 and Materials and Methods). D, The responses from C replotted normalized to unity to demonstrate the slower response kinetics of the GCAPs−/− cones (gray) compared with control cones (black).

Table 1.

Parameters of cone suction recordings

| Control | Control + BAPTA | GCAPs−/− | GCAPs−/− + BAPTA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Io (photons μm−2) | 3415 ± 857 (12) | 3035 ± 851 (10) | 1248 ± 178 (16) | 2390 ± 1173 (8) |

| Rmax (pA) | 4.5 ± 0.7 (12) | 4.2 ± 0.6 (10) | 6.2 ± 0.8 (16) | 7.7 ± 1.1 (8) |

| Time-to-peak (ms) | 112 ± 4 (12) | 152 ± 17 (10) | 221 ± 9 (16) | 207 ± 24 (8) |

| Integration time (ms) | 112 ± 10 (12) | 258 ± 67 (10) | 374 ± 23 (16) | 382 ± 36 (8) |

Mean ± SEM (n). Io is the flash strength that generates half-maximal response.

The fractional response to a single-cone pigment activation was 0.22 ± 0.06% (n = 12) of the total circulating current in control cones (Fig. 2C). This value is consistent with the ∼0.2% obtained in previous studies (Nikonov et al., 2006; Heikkinen et al., 2008). In the absence of GCAPs, the fractional response increased approximately threefold, to 0.63 ± 0.14% (n = 16) of the total circulating current in GCAPs−/− cones (Fig. 2C). Consistent with this increase in the single-photon response, cone sensitivity also increased approximately threefold in GCAPs−/− cones compared with control cones as indicated by the corresponding decrease in half-saturating flash intensity (Io) (Table 1). Together, these results indicate that the negative feedback on phototransduction by GCAPs strongly modulates the timely shutoff of the light response in mammalian cones and affects dramatically their response kinetics and sensitivity. Notably, the slower response recovery and increased single-photon response in GCAPs−/− cones are qualitatively similar to the effects observed in GCAPs−/− rods (Burns et al., 2002). These results are also consistent with in vivo studies of cone function in GCAPs-deficient mice (Pennesi et al., 2003).

BAPTA has no effect on GCAPs−/− cones

To investigate whether other components, such as recoverin and calmodulin, modulate cone dim flash response kinetics in a calcium-dependent manner, we pretreated control and GCAPs−/− mouse retinas with 100 μm BAPTA-AM to increase the buffering capacity of cone outer segments for Ca2+. BAPTA treatment slowed down substantially the kinetics of responses in control cones compared with untreated cones (Fig. 3A, Table 1) and often resulted in overshoot or oscillation during their inactivation, indicating that BAPTA-AM was successfully incorporated into cone outer segments. This result is consistent with the deceleration of response shutoff in GCAPs−/− cones and indicates that Ca2+-sensing proteins in cones are involved in modulating their dim flash response kinetics. In contrast, for GCAPs−/− cones, the kinesics of BAPTA-treated responses did not differ from those of untreated GCAPs−/− cones (Fig. 3B, Table 1). Thus, in the dim flash regimen, GCAPs appear to be the only calcium-dependent modulator of response kinetics in mouse cones.

Figure 3.

Lack of effect by BAPTA on GCAP−/− cone response kinetics. Normalized dim flash responses from control (A) and GCAP−/− (B) cones. Black traces show responses in control solution, and gray traces show responses from cones treated with 100 μm BAPTA-AM.

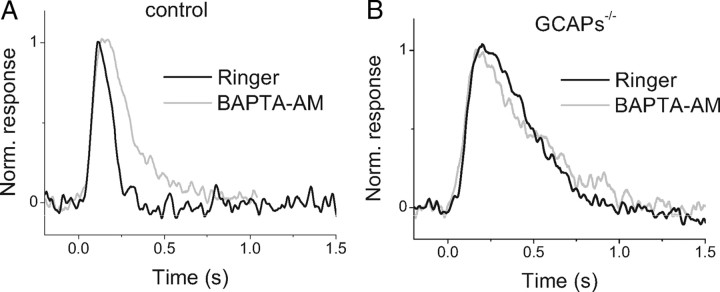

GCAPs modulate the kinetics and sensitivity of transretinal cone responses

To characterize further the role of GCAPs in mammalian cone phototransduction, we next investigated how their deletion affects light adaptation of mouse cones. To do that, we performed transretinal cone recordings from isolated retinas of Gnat1−/− mice (control retinas) and Gnat1−/− mice also lacking GCAPs (GCAPs−/− retinas). Although this method produces responses with a waveform similar to that of single-cell responses (Heikkinen et al., 2008; Wang and Kefalov, 2010), its major advantage over suction electrode recordings is that it provides stable and long-lasting recordings without significant deterioration of the responses for up to 2 h. The glutamate in the perfusion solution (for details, see Materials and Methods) saturated synaptic transmission to second-order neurons and enabled us to observe the isolated response produced by photoreceptors without interference from second-order neuron responses. We began by comparing the amplitudes and waveforms of flash responses from control and GCAPs−/− retinas under dark-adapted conditions (Fig. 4A,B) in experiments similar to the suction recordings described above. To avoid complications in the analysis, we used the dorsal part of the retina, populated predominantly with M-cones (Applebury et al., 2000; Haverkamp et al., 2005). Because we used 500 nm light for stimulation, any response from S-cones would be expected to contribute to the overall response only at high enough intensities that overcome their low sensitivity in this part of the spectrum. This, in turn, would be expected to result in shallower and wider than normal intensity–response function (Eq. 1). However, the intensity–response measurements for both control and GCAPs−/− retinas were well fitted with Equation 1 (Fig. 4D), indicating the negligible contribution of S-opsin and S-cones to the photoresponses.

Figure 4.

Flash response families of dark-adapted control cones (A) and GCAPs−/− cones (B) from transretinal recordings. Cone responses were evoked by a series of 500 nm test flashes (10 ms in duration) with intensities (photons μm−2) 36, 1.2 × 102, 3.9 × 102, 1.1 × 103, and 3.6 × 103. The largest response in each case was triggered by unattenuated white flash. C, Fractional single-photon responses of control (black) and GCAPs−/− (gray) cones. Error bars show SEM. The cone collecting area was estimated to be 0.12 μm2 (for details, see Eq. 6 and Materials and Methods). D, Intensity–response relations of cone transretinal responses to estimate sensitivity in control (filled circles) and GCAPs−/− (open circles) retinas. The solid curves represent the corresponding intensity–response functions (Eq. 1) with Io of 2180 and 918 photons μm−2, respectively. Error bars show SEM.

Similar to our findings from single-cell recordings above, the cone response kinetics of GCAPs−/− retinas were slower than those of control retinas (Fig. 4, compare A, B). The cone response time-to-peak was increased twofold, from 121 ± 4 ms in control retinas to 211 ± 5 ms in GCAPs−/− retinas (Table 2). The cone response integration time was also increased by >2.3-fold, from 183 ± 28 ms in controls retinas to 423 ± 21 ms in GCAPs−/− retinas (Table 2). Notably, the changes in cone response kinetics upon the deletions of GCAPs in transretinal (Table 2) and single-cell (Table 1) recordings were comparable. Furthermore, the fractional response by single-cone pigment activation was 0.30 ± 0.06% (n = 13) of the maximum response in control retinas and approximately threefold higher in GCAPs−/− retinas at 0.83 ± 0.12% (n = 13) (Fig. 4C). These values are also comparable with the ones obtained with single-cell recordings. Consistent with the increase in the single-photon response, the sensitivity of cones from GCAPs−/− retinas was also increased compared with that of cones from control retinas (Fig. 4D, Table 2). Together, these results indicate that the transretinal recordings from GCAPs-deficient cones yielded results essentially identical to the ones obtained using suction recordings. This validated our use of transretinal recordings to investigate the adaptation properties of control and GCAPs−/− cones described below.

Table 2.

Parameters of cone ERG recordings

| Control cones | GCAPs−/− cones | |

|---|---|---|

| Io (photons μm−2) | 2180 ± 380 (13) | 918 ± 110 (13)* |

| Rmax (μV) | 13.5 ± 0.6 (13) | 16.2 ± 1.0 (13)* |

| Time-to-peak (ms) | 121 ± 4 (13) | 211 ± 5 (13)** |

| Integration time (ms) | 183 ± 28 (13) | 423 ± 21 (13)** |

| SFD (photons−1 μm2) | 3.7E-04 ± 6.5E-05 (13) | 1.0E-03 ± 1.4E-04 (13)** |

| IS (photons μm−2 s−1) | 12,900 ± 3100 (7) | 1100 ± 280 (7)* |

| IR (photons μm−2 s−1) | 94,300 ± 26,100 (7) | 3900 ± 770 (7)* |

| k, Hill coefficient | 0.47 ± 0.04 (7) | 0.70 ± 0.03 (7)** |

Mean ± SEM (n). Student's t test determined significant differences:

*p < 0.05,

**p < 0.005. IS is parameter of Weber–Fechner function in Figure 6C. IR and k are parameters obtained from the fit with Equation 2 in Figure 5C.

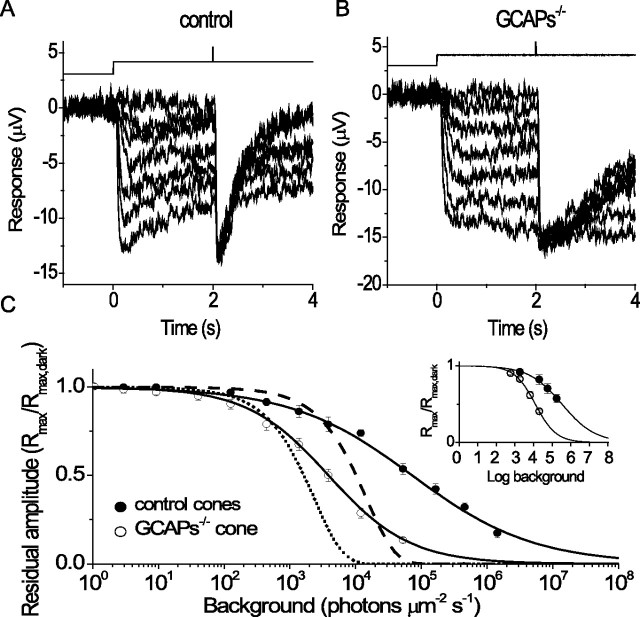

GCAPs modulate the operating range of background illumination for cones

A key manifestation of light adaptation is the extension of the range of intensities over which the sensory cell can operate (Torre et al., 1995). In the absence of adaptation, the maximum photoreceptor response declines exponentially with increasing background light and the cells rapidly saturate (Matthews et al., 1988). To determine the role of GCAPs in mammalian cone adaptation, we first investigated how their deletion affects the operating range of mouse cones. Figure 5, A and B, shows typical cone responses from control and GCAPs−/− retinas, respectively, to steps of background light of increasing intensities. The background light caused a rapid response followed by a partial relaxation attributable to adaptation. The residual cone response in steady state was measured with a saturating test flash delivered 2 s after the onset of the background. As expected, the maximum response declined with increasing background light for both control and GCAPs−/− retinas (Fig. 5C). From Equation 2, the background intensity that reduced the maximum cone response twofold (IR) was 94,300 photons μm−2 s−1 in control retinas and 3900 photons μm−2 s−1 in GCAPs−/− retinas (Table 2). Part of this 24-fold reduction could be attributed to the product of larger amplitude (2.7-fold) and longer integration time (2.3-fold) of the single-photon responses of GCAPs−/− cones compared with controls, giving a total of 6.2-fold shift in the position of the operating range. The remaining 3.9-fold could be explained by compromised background adaptation of mouse cones in the absence of GCAPs. Notably, the decline of the maximum cone response amplitude with increasing background light was steeper in the absence of GCAPs (Fig. 5C), producing a change in the Hill coefficient of Equation 2 from 0.47 in control retinas to 0.70 in GCAPs−/− retinas (Table 2). The operating range of mouse cones, defined as the ratio of the background intensity at which the residual amplitude is 95% of its dark-adapted value and the intensity at which it is 5%, decreased from 2.8 × 105-fold to 4.5 × 103-fold upon deletion of GCAPs.

Figure 5.

Effect of background light on cone operating range in control and GCAPs−/− retinas. Maximum cone response amplitudes under a series of background lights were measured 2 s after the onset of step light illumination in control (A) and GCAPs−/− (B) retinas by a test flash of unattenuated white light. The time course of light stimulation is shown on the top of each panel. The step light intensities (photons μm−2 s−1) were 0, 440, 1.3 × 103, 3.9 × 103, 1.2 × 104, 5.2 × 104, and 1.7 × 105 for control retina and 0, 130, 440, 1.3 × 103, 3.9 × 103, 1.2 × 104, and 5.2 × 104 for GCAPs−/− retina. C, Normalized maximum cone responses as a function of background intensity for control (filled circles) and GCAPs−/− (open circles) retina. The smooth curves represent best-fitted Hill equation (Eq. 2) with k = 0.47 and 0.70, IR = 94,300 and 3900 photons μm−2 s−1 for control and GCAPs−/−, respectively. Error bars show SEM. The dashed and dotted curves represent the expected change in maximum response of control and GCAPs−/− cones, respectively, in the absence of adaptation (Eq. 4). (Inset) Normalized maximum cone response as a function of background intensity for control (n = 5) and GCAPs−/− (n = 5) cones obtained with single-cell recordings. The curves represent best-fitted Hill equations with k = 0.49 and 0.78, IR = 3.4 × 105 and 1.2 × 104 photons μm−2 s−1 for control and GCAPs−/− cones, respectively.

To confirm our findings from transretinal recordings, we performed limited background adaptation experiments from individual cones using a suction electrode. The response kinetics from single-cell recordings were somewhat faster than those from transretinal recordings, producing a slight shift of their adaptation curves (Fig. 5, inset) to the right compared with those from transretinal recordings. This was most likely attributable to the difference in recording temperature: the single-cell recordings were done at 37°C versus 34°C for the transretinal recordings (this lower temperature was used to improve the stability and length of the transretinal recordings). Notably, however, the shift in the single-cell adaptation curve induced by GCAPs deletion was 28-fold, comparable with that measured with transretinal recordings. In addition, the values for the Hill coefficient, k, measured from these recordings, 0.49 and 0.78 for control and GCAPs−/− cones, respectively, were comparable with those measured from transretinal recordings (Table 2). Together, these results demonstrate that Ca2+ modulation of GC activity via GCAPs plays an important role in shifting the operating range of mammalian cones to brighter light and in widening their adaptation curve.

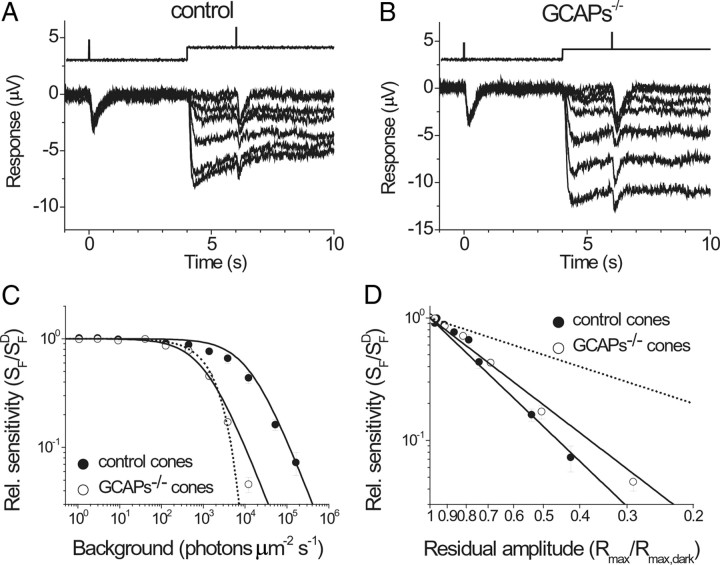

Deletion of GCAPs impairs cone light adaptation

To further characterize the role of GCAPs in mammalian cone adaptation, we next investigated how their deletion affects the light sensitivity of mouse cones. We used an experimental protocol similar to the one described above but now measured sensitivity by recording the cone dim flash responses 2 s after the onset of step light of various intensity in control (Fig. 6A) and GCAPs−/− (Fig. 6B) retinas. In both cases, the cone dim flash response amplitude gradually decreased with increasing background light intensity. Cone flash sensitivity (SF) decline in control and GCAPs−/− retinas could be fitted with the Weber–Fechner function (Eq. 3) (Fig. 6C). The background light required to reduce cone sensitivity twofold (IS) declined by 12-fold, from 12,900 photons μm−2 s−1 for control retina to 1100 photons μm−2 s−1 for GCAPs−/− retina (Table 2). The dim flash response used to estimate cone sensitivity was not >30% of the maximum for all backgrounds in both genotypes except for the two brightest backgrounds in GCAPs−/− retinas. There, the responses to dimmer flashes would have been too small to measure reliably due to response compression, and we were forced to use slightly higher flash intensity, producing 35 and 42% fractional responses. This likely explains the underestimation of GCAPs−/− cone sensitivity at backgrounds >2 × 103 photons μm−2 s−1 (Fig. 6C). Notably, the initial desensitization of GCAPs−/− cones in background light followed the expected change in sensitivity in the absence of adaptation (Eq. 4) (Fig. 6C, dotted line). Thus, the calcium modulation of GC is the dominant mechanism for mammalian cone adaptation in dim-to-moderate background light conditions.

Figure 6.

Effect of background light on cone sensitivity in control and GCAPs−/− retinas. Sensitivity under a series of background lights was measured from dim flash responses delivered 2 s after the onset of step light illumination in control (A) and GCAPs−/− (B) retinas. The time course of light stimulation is shown on the top of each panel. The flash intensities (photons μm−2) delivered in darkness for control and GCAPs−/− retinas were 1.6 × 103 and 120, respectively. The flash intensities (photons μm−2) delivered on the step light for control retina were 1.6 × 103 for the first five traces, 4.5 × 103, and 1.5 × 104. The flash intensities (photons μm−2) delivered on the step light for GCAPs−/− retina were 120 for first five traces, 500, and 1.6 × 103. The step light intensities in A and B are the same as in Figure 5, A and B, respectively. C, Fractional sensitivity (SF/SFD) as a function of background intensity. Flash sensitivity (SF) was determined by dividing the peak amplitude of dim flash response by the flash intensity and the maximal response amplitude for each retina. SFD is the flash sensitivity in darkness. Averages of control (filled circles) and GCAPs−/− (open circles) retinas. Solid curves are best-fitting Weber–Fechner functions with Is = 12,900 (control) and 1100 (GCAPs−/−) photons μm−2 s−1. The dotted curve represents the expected change in sensitivity of GCAPs−/− cones in the absence of adaptation (Eq. 4). D, Relative sensitivity (SF/SFD) as a function of the residual amplitude (Rmax/Rmax,dark) for control and GCAPs−/− cones. Combined data from C and Figure 5C. Residual amplitude determines the internal calcium concentration; as the residual amplitude declines, the internal calcium concentration becomes low. The decline in sensitivity against the reduction of calcium concentration was substantially shallower in GCAPs−/− retinas than in control retinas, demonstrating the impaired cone adaptation in the absence of GCAPs. The parameters of the best-fitting power functions (solid lines) are 2.94 for control cones and 2.35 for GCAPs−/− cones. The dotted line represents the expected change in sensitivity in the absence of Ca2+ modulation (Eq. 4) in GCAPs−/− cones. Error bars show SEM.

One complication of our analysis was the larger single-photon response amplitude and larger integration time of GCAPs−/− cones, which increased the effective activation by steady light in GCAPs−/− compared with control retinas (Fig. 5C). To exclude this effect on the flash sensitivity change, we plotted the normalized cone sensitivity (SF/SFD) against the normalized maximal residual amplitude (Fig. 6D). Considering that the internal calcium concentration declines proportionally to the residual photoreceptor dark current (Sampath et al., 1999; Matthews and Fain, 2003), the normalized residual response, Rmax/Rmax,dark, must be proportional to the relative change in calcium (Ca2+/Ca2+dark). Notably, GCAPs−/− cones desensitized less than control cones for equal decline in calcium levels (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that the deletion of GCAPs compromises the ability of cones to lower their sensitivity in adaptation to background light.

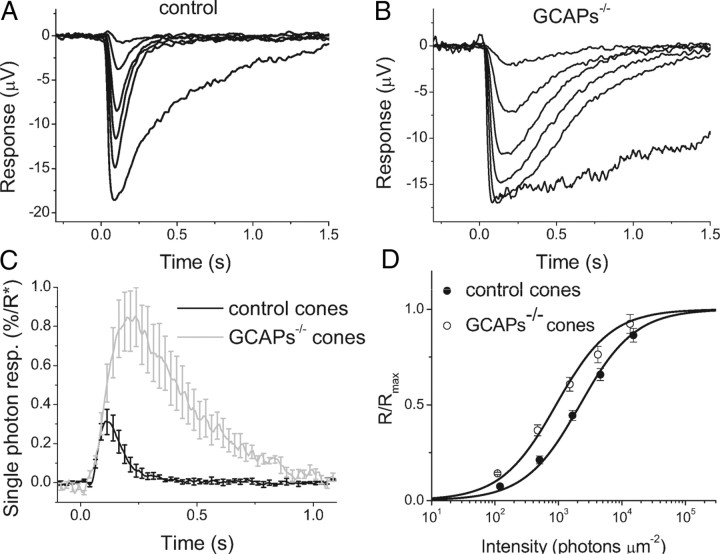

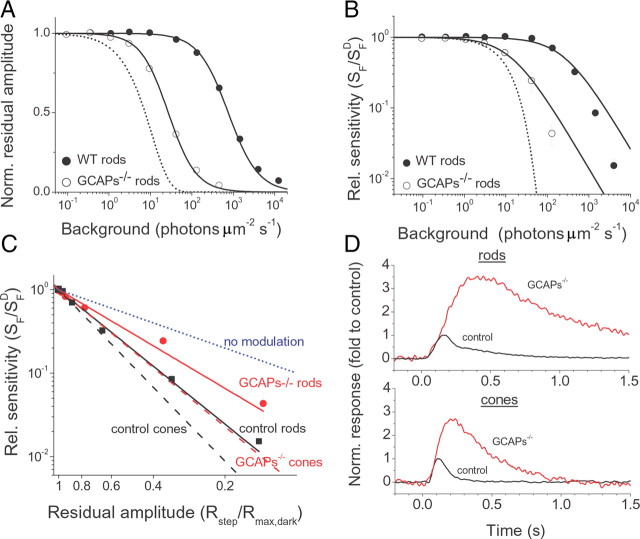

GCAPs and light adaptation in rods versus cones

The effects of GCAPs deletion on light adaptation in mouse rods has been characterized previously (Mendez et al., 2001). To compare the roles of GCAPs in adaptation in rods versus cones, we repeated and extended these rod experiments using the same transretinal recording protocols described above for cones. Similar to the case of cones, the maximum response of light-adapted rods declined with increasing background light for both wild-type control and GCAPs−/− retinas (Fig. 7A). The operating range of mouse rods spanned 140-fold of background light (Fig. 7A). This is 2000-fold less than the corresponding 2.8 × 105-fold operating range of cones (Fig. 5C). The background intensity that reduced the maximum rod response twofold from its dark-adapted level (IR) was 756 photons μm−2 s−1 in control rods and 27 photons μm−2 s−1 in GCAPs−/− rods (Table 3), indicating that 28-fold shift was induced by the deletion of GCAPs in rods. As in cones, part of this shift could be attributed to the increase in dark-adapted sensitivity (3.5-fold) and integration time (3.1-fold) upon the deletion of GCAPs in rods, giving a total of 11-fold difference (also larger than the corresponding 6.2-fold difference in cones). The remaining 2.5-fold (28/11) shift in the operating range to lower intensities could be explained by impaired rod adaptation. Notably, in contrast to the case in cones, the deletion of GCAPs in rods did not affect the Hill coefficient of their Weber–Fechner curve (Fig. 7A, Table 3). Thus, unlike in cones, in rods the Ca2+ modulation of GC activity via GCAPs does not widen their adaptation curve, and its effect is restricted to shifting the operating range of rods to brighter light.

Figure 7.

A, Normalized maximum rod responses as a function of background intensity for control (black circles, n = 10) and GCAPs−/− (open circles, n = 7) retina. The smooth curves represent best–fitted Hill equation with k = 1.20 and 1.29, IR = 756 and 27 photons μm−2 s−1 for control and GCAPs−/− rods, respectively. Error bars show SEM. The dotted curve represents the expected change in maximum response of GCAPs−/− rods in the absence of adaptation (Eq. 4). B, Relative sensitivity as a function of background intensity. Flash sensitivity (SF) was determined for each retina by dividing the peak amplitude of dim flash response by the flash intensity and the maximal amplitude for each retina. SFD is flash sensitivity in darkness. Averages of control (filled circles, n = 10) and GCAPs−/− (open circles, n = 7) retinas. Solid lines are best-fitting Weber–Fechner functions with IS = 272 [wild type (WT)] and 14 (GCAPs−/−) photons μm−2 s−1. The dotted curve represents the expected change in sensitivity of GCAPs−/− rods in the absence of adaptation (Eq. 4). C, Relative sensitivity (SF/SFD) as a function of residual amplitude (Rmax/Rmax,dark). The decline in sensitivity against the reduction of residual amplitude (indicative of calcium level) for both rods and cones was substantially shallower in GCAPs−/− retinas than in control retinas. The parameters of the best-fitting power functions are 2.30 for control rods (solid black line) and 1.69 for GCAPs−/− rods (solid red line). The dashed lines are the fitting functions for control cones (black) and GCAPs−/− cones (red) from Figure 6D. The blue dotted line represents the expected change in sensitivity in the absence of Ca2+ modulation. Error bars show SEM. D, Single-photon responses of rods (top) and cones (bottom) normalized by dividing them by their respective control peak amplitudes. The time of divergence of the GCAPs−/− (red) responses from control (black) responses was 120 ms for rods and 85 ms for cones.

Table 3.

Parameters of rod ERG recordings

| Control rods (n = 10) | GCAPs−/− rods (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Io (photons μm−2) | 19 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 |

| Rmax (μV) | 89 ± 9 | 83 ± 9 |

| Time-to-peak (ms) | 163 ± 5 | 389 ± 11 |

| Integration time (ms) | 336 ± 33 | 1025 ± 39 |

| SFD (photons−1 μm2) | 2.6E-02 ± 3.1E-03 | 9.1E-02 ± 2.0E-02 |

| IS (photons μm−2 s−1) | 272 ± 30 | 14 ± 3 |

| IR (photons μm−2 s−1) | 756 ± 92 | 27 ± 10 |

| k | 1.20 ± 0.07 | 1.29 ± 0.20 |

Mean ± SEM. SFD is a flash sensitivity in darkness. IS is a background intensity, which gives half the flash sensitivity in Figure 7B. IR and k are parameters obtained from the fit with Equation 2 in Figure 7A.

The impaired adaptation of GCAPs-deficient rods could also be observed from the shift in normalized flash sensitivity (SF/SFD) in GCAP−/− retinas (Fig. 7B). The background light required to reduce rod sensitivity twofold (IS) in control retinas was 272 photons μm−2 s−1 (Table 3). Taking into account the ∼30% smaller photoreceptor collecting area for transretinal recordings compared with single-cell recordings (for details, see Materials and Methods), this value is comparable with the 159 photons μm−2 s−1 value, measured from single-cell recordings (Mendez et al., 2001). The deletion of GCAPs resulted in 18-fold reduction of rod IS to 14 photons μm−2 s−1 (Fig. 7B, Table 3). To determine the effect of background on flash sensitivity independent of the change in maximum response amplitude, we again plotted the normalized sensitivity against the residual maximal amplitude for control and GCAPs−/− rods (Fig. 7C, solid lines). We then compared the adaptation in rods with the results obtained from cones, replotted from Figure 6D (Fig. 7C, dashed lines). For comparison, we also included the expected decline in relative sensitivity in the absence of any Ca2+ modulation (Fig. 7C, blue dotted line). The extent of Ca2+ modulation for each photoreceptor could be quantified by the shift in the slope of the corresponding fitting power functions. Thus, the contribution of GCAPs to Ca2+ modulation in rods could be estimated as 0.7 by dividing the power function of GCAPs−/− rods (solid red line) by the power function of control rods (solid black line). This ratio, 1.7/2.3, indicated that 30% of the flash sensitivity decline in rods could be attributed to GCAPs feedback. Notably, the contribution of GCAPs to Ca2+ modulation in cones, estimated by dividing the corresponding power functions of GCAPs−/− cones (dashed red line) and control cones (dashed black line), was 0.8 (2.4/2.9), indicating that only 20% of the flash sensitivity decline in cones could be attributed to GCAP feedback. Thus, the extent of Ca2+-dependent modulation on adaptation by GCAPs appears to be larger in mammalian rods than that in cones.

Discussion

Our analysis of the function of GCAPs-deficient mouse cones demonstrates that the Ca2+ feedback to guanylyl cyclase regulates mammalian cone flash response sensitivity and kinetics in darkness and during light adaptation. Block of this modulation in mouse cones by the deletion of GCAP1 and GCAP2 increased the fractional flash response threefold compared with control cones. Although the rising phase of the dim flash response was not affected by the lack of GCAPs modulation, the shutoff of the response was severely delayed, with a twofold longer time-to-peak and threefold longer integration time. Block of the Ca2+ feedback mediated by GCAPs also shifted by 24-fold the operating range of cones to lower background lights and narrowed their adaptation curve. Most (6.2-fold) of the reduction in the cone operating range could be explained by the increase in single-photon response amplitude and integration time of GCAPs-deficient cones compared with controls. Comparison of the effects of GCAPs deletion in mammalian rods and cones revealed that, surprisingly, the Ca2+ modulation on guanylyl cyclase is weaker in cones than in rods both in darkness and during light adaptation.

GCAPs are required for the timely response shutoff in mammalian cones

The decline in calcium induced by light could modulate phototransduction through at least three different feedback mechanisms affecting shutoff of the photoactivated pigment, the conductance of the cGMP channels, and the synthesis of cGMP. For rods, the Ca2+-dependent modulation of cGMP synthesis by GC is dominant in dim light conditions (Koutalos and Yau, 1996; Burns et al., 2002; Makino et al., 2004). In contrast, modulation of the photoactivated pigment (Burns et al., 2002; Makino et al., 2004) and the cGMP-gated channels (Chen et al., 2010) play no detectable role in rod background light adaptation. Our finding that BAPTA fails to slow down the response of GCAPs−/− cones (Fig. 3B) indicates that, similar to the case in rods, GCAP modulation on the synthesis of cGMP is the major mechanism controlling the timely shutoff of dim flash responses in mammalian cones.

Comparison of dim flash transretinal responses from control and GCAPs-deficient photoreceptors allowed us to estimate and compare the times of onset of the calcium modulation of GC after a flash in rods and cones. In rods, the GCAPs-deficient responses began deviating from control responses ∼120 ms after the flash (Fig. 7D). In cones, the two responses deviated at ∼80 ms. Thus, consistent with the expected faster decline of calcium in cones compared with rods (Sampath et al., 1999), the onset of their GCAPs modulation was also faster. Interestingly, this 1.4-fold (120/80) slower onset of the GCAPs feedback in rods versus cones was comparable with the 1.5-fold (163/121) larger time-to-peak of rods versus cones (Tables 2 and 3). Thus, the difference in time-to-peak between rods and cones could possibly be attributable to the slower onset of the GCAPs feedback in rods compared with cones.

Weaker GCAPs modulation in cones than in rods

Our study clearly demonstrates that Ca2+-dependent modulation of cGMP synthesis by GCAPs affects the dark-adapted response kinetics and sensitivity as well as the adaptation capacity of mammalian cones. Considering the wider functional range of cones compared with rods, we expected that Ca2+-dependent modulation of GCAPs in cones will be stronger than that in rods. However, surprisingly, the strength of the modulation by GCAPs in dark-adapted state appears to be lower in cones than in rods. Thus, deletion of GCAPs resulted in only twofold to threefold increase in single-photon response amplitude in mouse cones (Figs. 2C, 4C) compared with a corresponding fivefold to sixfold increase in mouse rods (Mendez et al., 2001). Another way of comparing the strength of GCAPs modulation in rods and cones is by estimating the feedback loop gain, gL, as described previously (Burns et al., 2002). For small responses that cause linear perturbations in the loop, γL = 1 + gL, where γL is the ratio of time integrals of single-photon response in GCAPs−/− and control cones. The ratio of single-photon responses in GCAPs−/− and control cones was 2.9 (0.63/0.22; see Results) and the corresponding ratio of integration times was 3.3 (374/112; Table 2). Thus, the time integral of the GCAPs−/− cone responses was 9.6-fold larger than that of control cone responses. This gave a value for γL of 9.6, and a cone feedback loop gain of 8.6. Notably, this value is lower than the corresponding strength of the feedback loop in rods, previously estimated to be 11 (Burns et al., 2002). Together, these results rule out differences in the strength of feedback on cGMP synthesis as a possible mechanism contributing to the lower sensitivity of mammalian cones compared with rods.

The strength of the modulation by GCAPs was comparable or perhaps even slightly lower in mouse cones than in rods during background adaptation. The deletion of GCAPs induced a 24-fold shift to lower intensities in the operating range in mouse cones (Fig. 5C, Table 2) compared with a corresponding 28-fold shift in mouse rods (Fig. 7B, Table 3). The relatively weak contribution of GCAPs modulation to light adaptation in cones compared with rods was confirmed by the smaller shift in the relative sensitivity versus residual maximal response function during the deletion of GCAPs (Fig. 7C) for cones (20%) compared with rods (30%). These results also indicate that, although the Ca2+ feedback on GC is the main mechanism for mammalian cone background adaptation for dim-to-moderate light intensities (Fig. 6C), other mechanisms dominate adaptation in brighter light conditions.

One notable difference between rods and cones was how the deletion of GCAPs affected their operating range. In rods, the deletion of GCAPs resulted in a simple shift of the adaptation curve without affecting its Hill coefficient (Fig. 7A, Table 3). In contrast, in cones, the deletion of GCAPs not only shifted their adaptation curve but also accelerated cone saturation as demonstrated by the higher Hill coefficient of adaptation (Fig. 5C, Table 2). Thus, GC modulation by GCAPs hinders saturation and widens the operating range in mammalian cones but not in rods.

Rod versus cone isoforms of GC and GCAPs

A possible explanation for the differences in strength of the Ca2+ feedback on cGMP synthesis in rods and cones could be the expression of rod/cone-specific isoforms of GC and GCAPs or the coexpression of their isoforms with different ratios in rods and cones. For instance, carp rods and cones express different isoforms of GC (GC-R1 and GC-R2 in rods vs GC-C in cones) and GCAPs (GCAP1 and GCAP2 in rods vs GCAP3 in cones) (Takemoto et al., 2009). This would allow for photoreceptor-specific tuning of the modulation of cGMP synthesis in rods versus cones. In contrast, rods and cones in the mouse share the same isoforms of GC and GCAPs (Howes et al., 1998). However, mouse cones primarily express GC1 and GCAP1 (Cuenca et al., 1998), whereas mouse rods express both isoforms of GC (GC1 and GC2) and GCAP (GCAP1 and GCAP2) (Cuenca et al., 1998; Baehr and Palczewski, 2007). It is possible, therefore, that differences in the Ca2+ sensitivities of GCAP1 and GCAP2 and in the way that they modulate GC1 and GC2 (Peshenko and Dizhoor, 2004) account for the rod/cone differences in modulation of cGMP synthesis. Notably, the GCAP2 modulation of guanylyl cyclase in rods becomes more prominent at higher intensities of background light (Makino et al., 2008). This observation is consistent with our finding that the overall modulation of guanylyl cyclase is weaker in mouse cones, which express primarily GCAP1, than in mouse rods, in which GCAP2 is expressed more abundantly.

Another possibility is that the expression levels of GC and GCAPs differ in rods and cones. Indeed, in the case of carp retina, the expression of both GC and GCAPs is significantly higher in cones compared with rods (Takemoto et al., 2009) and the basal activity of GC in cones is 36-fold higher than that in rods. In addition to the rod/cone differences in GC and GCAPs expression, this higher activity of GC in dark-adapted cones might be attributable to a lower level of dark-adapted Ca2+ in cones compared with rods (Sampath et al., 1998, 1999). A higher dark-adapted activity of GC (and concomitant higher dark phosphodiesterase activity) would restrict the range of upregulation of cGMP synthesis during illumination in cones compared with rods. Consistent with this notion, the incremental GC activity in carp rods at a low Ca2+ concentration, namely in light-adapted conditions, increases by a factor of 7 compared with that at a high Ca2+ concentration, namely in darkness, whereas the GC activity in cones in light-adapted conditions is raised by only twofold compared with that in darkness (Takemoto et al., 2009). This observation is consistent with our results indicating a smaller contribution of GCAPs modulation to light adaptation in cones compared with that in rods. Thus, the wide range of adaptation in cones could be accomplished by the Ca2+-mediated modulation of photoactivated pigment lifetime, cGMP channel conductance, or by additional, yet unknown mechanisms.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants, EY19543 and EY19312 (V.J.K.), EY12703 and EY12155 (J.C.), and EY02687 (Department Ophthalmology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO), a Career Development Award from Research to Prevent Blindness, the Karl Kirchgessner Foundation (V.J.K.), and a grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation, Japan (K.S.). We thank Janis Lem for the Gnat1−/− animals and Cheryl Craft for the cone arrestin antibody.

References

- Applebury ML, Antoch MP, Baxter LC, Chun LL, Falk JD, Farhangfar F, Kage K, Krzystolik MG, Lyass LA, Robbins JT. The murine cone photoreceptor: a single cone type expresses both S and M opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron. 2000;27:513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehr W, Palczewski K. Guanylate cyclase-activating proteins and retina disease. Subcell Biochem. 2007;45:71–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW. Responses of retinal rods to single photons. J Physiol. 1979;288:613–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolnick DA, Walter AE, Sillman AJ. Barium suppresses slow PIII in perfused bullfrog retina. Vision Res. 1979;19:1117–1119. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton RM, Whitten DN. Visual adaptation in monkey cones: recordings of late receptor potentials. Science. 1970;170:1423–1426. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3965.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ME, Arshavsky VY. Beyond counting photons: trials and trends in vertebrate visual transduction. Neuron. 2005;48:387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ME, Mendez A, Chen J, Baylor DA. Dynamics of cyclic GMP synthesis in retinal rods. Neuron. 2002;36:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert PD, Krasnoperova NV, Lyubarsky AL, Isayama T, Nicoló M, Kosaras B, Wong G, Gannon KS, Margolskee RF, Sidman RL, Pugh EN, Jr, Makino CL, Lem J. Phototransduction in transgenic mice after targeted deletion of the rod transducin alpha -subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13913–13918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250478897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM. Rods and cones in the mouse retina. I. Structural analysis using light and electron microscopy. J Comp Neurol. 1979;188:245–262. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Woodruff ML, Wang T, Concepcion FA, Tranchina D, Fain GL. Channel modulation and the mechanism of light adaptation in mouse rods. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16232–16440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2868-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca N, Lopez S, Howes K, Kolb H. The localization of guanylyl cyclase-activating proteins in the mammalian retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1243–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrey T, Koutalos Y. Vertebrate photoreceptors. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:49–94. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(00)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain GL, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Koutalos Y. Adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:117–151. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DG. Light adaptation in the rat retina: evidence for two receptor mechanisms. Science. 1971;174:598–600. doi: 10.1126/science.174.4009.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hárosi FI. Polarized microspectrophotometry for pigment orientation and concentration. Methods Enzymol. 1982;81:642–647. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)81088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Wässle H, Duebel J, Kuner T, Augustine GJ, Feng G, Euler T. The primordial, blue-cone color system of the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5438–5445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1117-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen H, Nymark S, Koskelainen A. Mouse cone photoresponses obtained with electroretinogram from the isolated retina. Vision Res. 2008;48:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes K, Bronson JD, Dang YL, Li N, Zhang K, Ruiz C, Helekar B, Lee M, Subbaraya I, Kolb H, Chen J, Baehr W. Gene array and expression of mouse retina guanylate cyclase activating proteins 1 and 2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:867–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Kefalov V, Sakurai K, Chisaka O, Ueda Y, Onishi A, Morizumi T, Fu Y, Ichikawa K, Nakatani K, Honda Y, Chen J, Yau KW, Shichida Y. Molecular properties of rhodopsin and rod function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6677–6684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610086200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KW, Stryer L. Highly cooperative feedback control of retinal rod guanylate cyclase by calcium ions. Nature. 1988;334:64–66. doi: 10.1038/334064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenbrot JI. Ca2+ flux in retinal rod and cone outer segments: differences in Ca2+ selectivity of the cGMP-gated ion channels and Ca2+ clearance rates. Cell Calcium. 1995;18:285–300. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenbrot JI, Rebrik TI. Tuning outer segment Ca2+ homeostasis to phototransduction in rods and cones. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;514:179–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0121-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutalos Y, Yau KW. Regulation of sensitivity in vertebrate rod photoreceptors by calcium. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)89624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino CL, Dodd RL, Chen J, Burns ME, Roca A, Simon MI, Baylor DA. Recoverin regulates light-dependent phosphodiesterase activity in retinal rods. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:729–741. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino CL, Peshenko IV, Wen XH, Olshevskaya EV, Barrett R, Dizhoor AM. A role for GCAP2 in regulating the photoresponse. Guanylyl cyclase activation and rod electrophysiology in GUCA1B knock-out mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29135–29143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804445200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews HR, Fain GL. The effect of light on outer segment calcium in salamander rods. J Physiol. 2003;552:763–776. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews HR, Murphy RL, Fain GL, Lamb TD. Photoreceptor light adaptation is mediated by cytoplasmic calcium concentration. Nature. 1988;334:67–69. doi: 10.1038/334067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez A, Burns ME, Sokal I, Dizhoor AM, Baehr W, Palczewski K, Baylor DA, Chen J. Role of guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) in setting the flash sensitivity of rod photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9948–9953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171308998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani K, Chen C, Yau KW, Koutalos Y. Calcium and phototransduction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;514:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0121-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonov SS, Daniele LL, Zhu X, Craft CM, Swaroop A, Pugh EN., Jr Photoreceptors of Nrl−/− mice coexpress functional S- and M-cone opsins having distinct inactivation mechanisms. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:287–304. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonov SS, Kholodenko R, Lem J, Pugh EN., Jr Physiological features of the S- and M-cone photoreceptors of wild-type mice from single-cell recordings. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:359–374. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nymark S, Heikkinen H, Haldin C, Donner K, Koskelainen A. Light responses and light adaptation in rat retinal rods at different temperatures. J Physiol. 2005;567:923–938. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Polans AS, Baehr W, Ames JB. Ca(2+)-binding proteins in the retina: structure, function, and the etiology of human visual diseases. Bioessays. 2000;22:337–350. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200004)22:4<337::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennesi ME, Howes KA, Baehr W, Wu SM. Guanylate cyclase-activating protein (GCAP) 1 rescues cone recovery kinetics in GCAP1/GCAP2 knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6783–6788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1130102100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshenko IV, Dizhoor AM. Guanylyl cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) are Ca2+/Mg2+ sensors: implications for photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase (RetGC) regulation in mammalian photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16903–16906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai K, Onishi A, Imai H, Chisaka O, Ueda Y, Usukura J, Nakatani K, Shichida Y. Physiological properties of rod photoreceptor cells in green-sensitive cone pigment knock-in mice. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:21–40. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath AP, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Fain GL. Bleached pigment produces a maintained decrease in outer segment Ca2+ in salamander rods. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:53–64. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath AP, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Bandarchi J, Fain GL. Light-dependent changes in outer segment free-Ca2+ concentration in salamander cone photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:267–277. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G, Yau KW, Chen J, Kefalov VJ. Signaling properties of a short-wave cone visual pigment and its role in phototransduction. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10084–10093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillman AJ, Ito H, Tomita T. Studies on the mass receptor potential of the isolated frog retina. I. General properties of the response. Vision Res. 1969;9:1435–1442. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(69)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto N, Tachibanaki S, Kawamura S. High cGMP synthetic activity in carp cones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11788–11793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812781106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre V, Ashmore JF, Lamb TD, Menini A. Transduction and adaptation in sensory receptor cells. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7757–7768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07757.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Kefalov VJ. Single-cell suction recordings from mouse cone photoreceptors. J Vis Exp. 2010;pii:1681. doi: 10.3791/1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Li A, Brown B, Weiss ER, Osawa S, Craft CM. Mouse cone arrestin expression pattern: light induced translocation in cone photoreceptors. Mol Vis. 2002;8:462–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]