Abstract

MAPK kinase (MEK)1 and MEK2 were deleted from Leydig cells by crossing Mek1f/f;Mek2−/− and Cyp17iCre mice. Primary cultures of Leydig cell from mice of the appropriate genotype (Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+) show decreased, but still detectable, MEK1 expression and decreased or absent ERK1/2 phosphorylation when stimulated with epidermal growth factor, Kit ligand, cAMP, or human choriogonadotropin (hCG). The body or testicular weights of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice are not significantly affected, but the testis have fewer Leydig cells. The Leydig cell hypoplasia is paralleled by decreased testicular expression of several Leydig cell markers, such as the lutropin receptor, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme, 17α-hydroxylase, and estrogen sulfotransferase. The expression of Sertoli or germ cell markers, as well as the shape, size, and cellular composition of the seminiferous tubules, are not affected. cAMP accumulation in response to hCG stimulation in primary cultures of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice is normal, but basal testosterone and testosterone syntheses provoked by addition of hCG or a cAMP analog, or by addition of substrates such as 22-hydroxycholesterol or pregnenolone, are barely detectable. The Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ males show decreased intratesticular testosterone and display several signs of hypoandrogenemia, such as elevated serum LH, decreased expression of two renal androgen-responsive genes, and decreased seminal vesicle weight. Also, in spite of normal sperm number and motility, the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice show reduced fertility. These studies show that deletion of MEK1/2 in Leydig cells results in Leydig cell hypoplasia, hypoandrogenemia, and reduced fertility.

The development and maintenance of the male phenotype and fertility in adults are highly dependent on androgens, which are synthesized by two distinct populations of testicular Leydig cells. In mice, fetal Leydig cells arise at 12.5 d after coitum, and the androgens they produce masculinize the fetus and contribute to testicular descent (1–3). Around postnatal d 7, a second population of Leydig cells starts to proliferate and differentiate, and they become responsible for the synthesis of testosterone that is required for puberty and for fertility during adulthood (3, 4). The proliferation and differentiation of fetal Leydig cells are independent of the pituitary-derived LH but are dependent on intratesticular hormones, such as desert hedgehog and platelet-derived growth factor (1–3, 5–8). In contrast, the proliferation and differentiation of postnatal Leydig cells is highly dependent on LH, and adult mice that are gonadotropin deficient or null for the LH receptor (LHR) display Leydig cell hypoplasia, high gonadotropin levels, hypoandrogenemia, and infertility (3, 5–7, 9). The fate of fetal Leydig cells is unclear. They may atrophy and disappear in the first few days after birth or they may persist but eventually become outnumbered by the population of Leydig cells that arises postnatally.

Although cAMP is the most important proximal mediator of the actions of LH (10), downstream pathways that may regulate the proliferation and differentiation of the postnatal population of Leydig cells are not completely understood. It has become recently clear, however, that one of the consequences of the activation of the LHR in immortalized Leydig cell lines or primary cultures of postnatal Leydig cells is the activation of the MAPK kinase (MEK)/ERK cascade (11–14), and this pathway has been implicated as a modulator of steroid synthesis (12, 13, 15), as well as a critical component of their proliferation and/or survival (14, 16). Because all of these studies have been done in cell culture, we set out to test for the role of the Leydig cell MEK/ERK cascade in a more physiological setting. Here, we report that a Leydig cell-specific deletion of MEK1/2 in mice does not affect prenatal sexual development but leads to Leydig cell hypoplasia, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, and loss of fertility in adult mice.

Results

Conditional deletion of MEK1/2 in mouse Leydig cells

A conditional deletion of MEK1/2 in Leydig cells was accomplished by crossing Mek1f/f;Mek2−/− (17–20) with Cyp17iCre mice (21). This strategy was chosen because a global deletion of Mek1 results in embryonic lethality, whereas a global deletion of Mek2 has not overt reproductive phenotype (17, 18). The Cyp17 promoter allows for Cre expression in fetal and adult Leydig cells as well as adrenocortical and ovarian theca cells (7, 21, 22). Cre expression in ovarian theca cells is not relevant to our studies, because we used only male mice. The presumed recombination of the Mek1f/f allele in the adrenal cortex could have resulted in adrenal insufficiency of the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice, but we did not observe such effects.

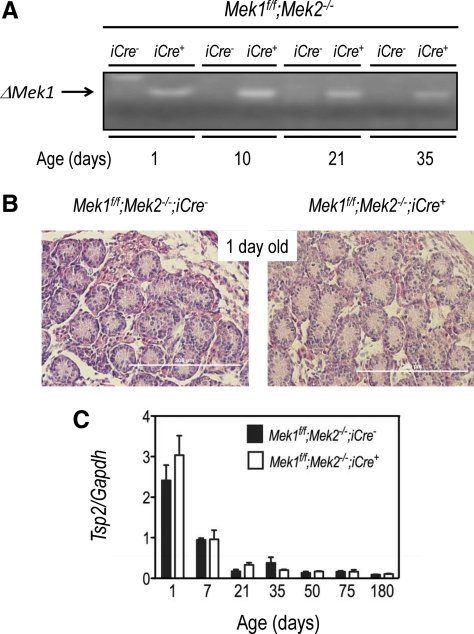

Although we did not test for recombination of the Mek1f/f allele in fetal Leydig cells, the expression of Cyp17iCre in this cell population has been previously documented (21). Recombination of the Mek1f/f allele in the postnatal testes could be readily detected 1 d after birth (Fig. 1A), when postnatal Leydig cells have not begun to actively proliferate and before the onset of the expression of Cyp17 in the postnatal testes (see figure 4B and Ref. 22). In addition, the histology of 1-d-old testis (Fig. 1B) and the postnatal pattern of expression of Tsp2, a fetal Leydig cell marker (22), were indistinguishable in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− and Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Normal prenatal development in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. A, The recombined Mek1f/f allele (ΔMek1) was amplified from genomic DNA isolated from the testes of mice of the indicated ages. Results of a representative experiment (repeated three times) are shown. B, Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the testes of 1-d-old mice. Results of a representative experiment (repeated three times) are shown. C, The expression of Tsp2 was assessed by real-time PCR using RNA isolated from the testes of mice of the indicated ages. Each bar represents the mean ± sem of three different mice.

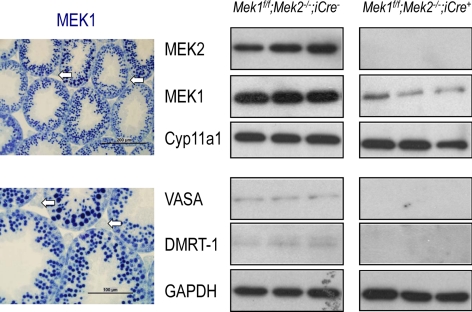

We did not attempt to detect recombination of the Mek1f/f allele in postnatal Leydig cells by immunohistochemical staining of testicular sections, because the high levels of expression of MEK1 in germ cells obscures the detection of MEK1 in Leydig cells (Fig. 2A). However, we could readily document decreased, but still detectable, expression of MEK1 using primary cultures of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (Fig. 2B). The relative purity of these primary cultures was demonstrated by the robust expression of Cyp11a1, a Leydig cell marker (22) coupled with minimal expression of VASA, a germ cell marker (23), and doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor 1, a Sertoli cell and spermatogonia marker (24). A reduction in the activity of the MEK/ERK pathway was also documented in the primary cell cultures of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (Fig. 3). The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 provoked by activation of the LHR with human choriogonadotropin (hCG) (an LH surrogate), by addition of a cAMP analog, or by activation of c-kit, was undetectable in Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (Fig. 3). In contrast, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 provoked by epidermal growth factor (EGF) was only reduced by approximately 60% (Fig. 3). These results clearly show that the reduction in stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation, although variable in magnitude, is not unique to the hCG stimulus.

Fig. 2.

Lack of expression of MEK2 and reduced expression of MEK1 in primary cultures of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Left panels, Testicular sections of 35-d-old wt mice were stained with an antibody to MEK1, which was subsequently visualized using an alkaline phosphatase-based ABC kit from Vector Labs and the Vector blue substrate. Some lightly stained Leydig cells are highlighted with arrows. These show minimal staining because of the intense staining detected in the seminiferous epithelium. Results of a representative experiment (repeated three times) are shown. Right panels, Western blottings were prepared using equal amounts of protein obtained from lysates of primary cultures of Leydig cells of 35-d-old wt or Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice and tested for MEK1, MEK2, Cyp11a1 (a Leydig cell marker), VASA (a germ cell marker), and doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor 1 (DMRT-1) (a Sertoli and spermatogonia marker). GAPDH is also shown as a loading control. Each lane shown represents a different mouse.

Fig. 3.

Decreased stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Primary cultures of Leydig cells prepared from 35-d-old mice were incubated without or with hCG (100 ng/ml, 30 min), Bt2cAMP (1 mm, 30 min), Kit ligand (KitL) (100 ng/ml, 15 min), or EGF (0.1 ng/ml, 5 min). Western blots were prepared using equal amounts of protein and tested for P-ERK1/2. Total ERK1/2 was subsequently detected in the same blots after stripping them. Leydig cells from different mice were used for each of the four stimuli shown. The results are from a representative experiment that was repeated three to six times.

Taken together, these results show that the postnatal population of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice lacks MEK2, displays reduced expression of MEK1, and displays a reduction in ERK1/2 phosphorylation when stimulated by endocrine or paracrine stimuli.

Characterization of Leydig cell functions in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice

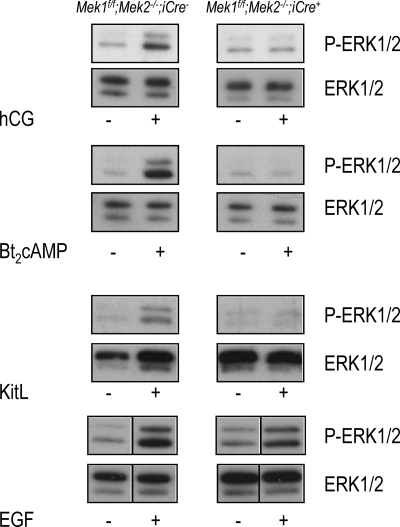

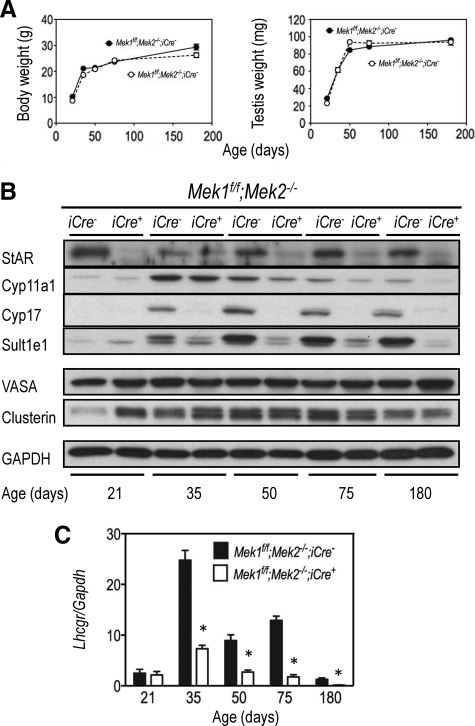

Postnatal body and testicular weights were unaffected in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (Fig. 4A), but the expression of several Leydig cell markers was dramatically reduced (Fig. 4, B and C). Leydig cell markers that were reduced include steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), a cytosolic/mitochondrial protein involved in cholesterol transport (25); Cyp11a1, the mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone (P5) (26); Cyp17a1, a microsomal enzyme that metabolizes progesterone (26); Sult1e1, a cytosolic enzyme that conjugates estrogens to sulfate (27); and the Lhcgr, the seven-transmembrane receptor for LH, the main endocrine regulator of Leydig cell functions (3, 5, 10). StAR, Cyp11a1, Cyp17a1, and the Lhcgr are expressed in fetal and adult Leydig cells, but in the postnatal period, their expression increases with puberty and peaks at adulthood (22). Sult1e1, on the other hand, is expressed only in adult Leydig cells (22). Decreased expression of Sult1e1 and the Lhcgr in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice was first noticeable as the mice went through puberty (∼35 d), whereas decreased expression of Cyp11a1 in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice was not detectable until adulthood (50 d and beyond). StAR expression was already reduced in 21-d-old Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice and remained low through their life span. The expression of Cyp17a1 was not detectable until 35 d of age in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− mice, but at this age, it was already decreased in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Lastly, the expression of VASA, a germ cell marker (23), was unchanged, whereas the expression of clusterin, a Sertoli cell marker (28), was increased in 21-d-old mice and unchanged afterwards. We did not seek an explanation for the increase in clusterin expression in 21-d-old mice.

Fig. 4.

Decreased expression of Leydig cell markers in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. A, The body and testicular weight of mice were recorded at different ages. Each point is the mean ± sem of three to four animals. If error bars are not visible is because they fall within the symbols. B, Whole testicular lysates were prepared from three mice of the indicated ages. The protein concentration of the lysates was equalized, and equal amounts of lysates from three different mice were combined. Western blottings were prepared using equal amounts of protein and tested for several Leydig cell markers (StAR, Cyp11a1, Cyp17, and Sult1e1), a germ cell marker (VASA), and a Sertoli cell marker (clusterin). GAPDH is shown as a loading control. C, The expression of the Lhcgr (another Leydig cell marker) was assessed by real-time PCR using RNA isolated from the testes of mice of the indicated ages. Each bar represents the mean ± sem of three different mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) at each age.

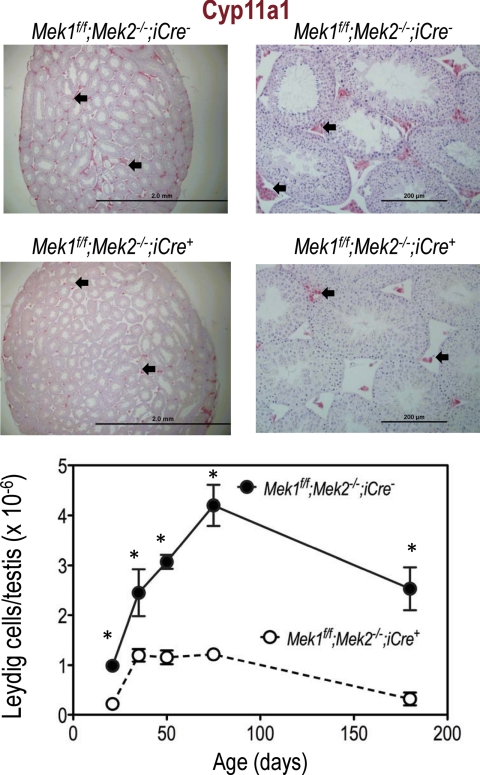

The number of Leydig cells (defined as Cyp11a1 positive cells) per testis was also reduced in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice at all ages examined, but the diameter of the seminiferous tubules and the appearance of the seminiferous epithelium were similar in both genotypes (Fig. 5). The data on the number of Leydig cells/testis suggest that there is an increase in Leydig cell numbers up to about postnatal d 35 in the testis of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. After postnatal d 35, however, the number of Leydig cells/testis continued to increase for another month or so in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− mice (as expected from data obtained with wild-type mice, see Refs. 9, 29) but remained constant in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Similar results were obtained when all interstitial cells (instead of only Cyp11a1 positive cells) were counted (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Leydig cell hypoplasia in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Top panels, Testicular sections of 75-d-old Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− and Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice were stained with an antibody to Cyp11a1, which was subsequently visualized using an alkaline phosphatase-based ABC kit from Vector Labs and Vector red substrate. Some Leydig cells are highlighted with the arrows. Results of a representative experiment (repeated three times) are shown. Bottom panel, Leydig cells (defined as Cyp11a1 positive cells) were counted in testicular sections of mice of the indicated ages stained with Cyp11a1 as shown in the top panels. The total number of Leydig cells/testis was calculated as described as described in Materials and Methods. Each point is the mean ± sem of three different mice. Some error bars are not visible because they fall within the symbols. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

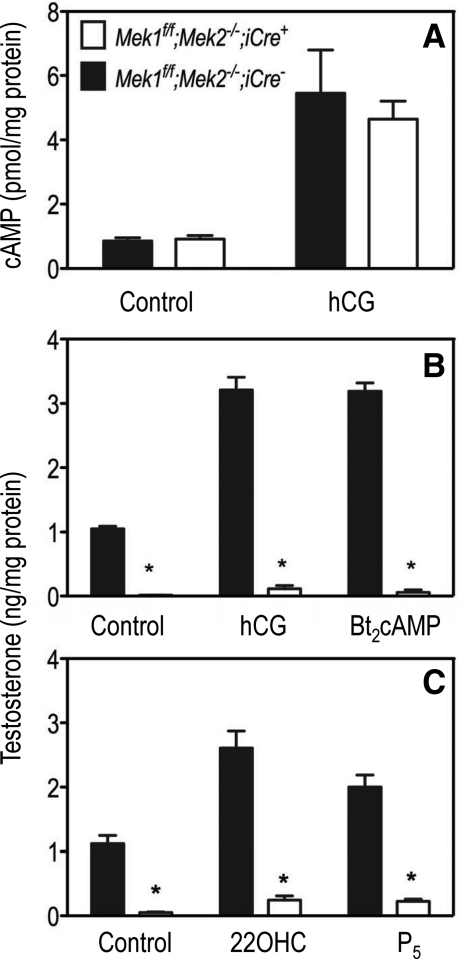

The functional properties of Leydig cells were examined using primary cultures prepared from adult (50-d-old) mice. The ability of hCG to stimulate cAMP synthesis was the same in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− and Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ Leydig cells (Fig. 6A), but testosterone synthesis was drastically impaired in the Leydig cells of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice incubated with hCG (Fig. 6B). Testosterone synthesis was also severely reduced when Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ Leydig cells were incubated with dibutyryl (Bt2)cAMP (Fig. 6B), 22-hydroxycholesterol (22OHC), a soluble cholesterol substrate that bypasses the rate-limiting step of steroidogenesis, or with P5, which bypasses not only cholesterol transport but also the first step of steroidogenesis (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice have a normal cAMP response but reduced steroidogenic responses. A, cAMP accumulation was measured in primary cultures of Leydig cells (prepared from 50-d-old mice) incubated without or with hCG (100 ng/ml) in the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor for 30 min at 34 C. Results are the mean ± sem of four mice. B, Testosterone accumulation was measured in primary cultures of Leydig cells (prepared from 50-d-old mice) incubated without or with hCG (100 ng/ml) or Bt2cAMP (1 mm) for 4 h at 34 C. Results are the mean ± sem of five mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). C, Testosterone accumulation was measured in primary cultures of Leydig cells (prepared from 50-d-old mice) incubated without or with 22OHC (10 μm) or P5 (10 μm) for 4 h at 34 C. Results are the mean ± sem of five mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

These results show that, in the postnatal period, the number of Leydig cells per testes and their functional properties is dependent on the MEK/ERK cascade.

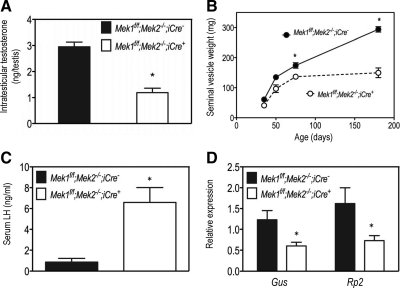

Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice have reduced testosterone levels and impaired fertility

The results presented above predict low androgen levels in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Because serum testosterone levels can be highly variable and thus obscure small changes, we measured intratesticular testosterone instead and found that these levels are reduced by approximately 40% in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ when compared with Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− mice (Fig. 7A). Three other readouts of androgen action, decreased seminal vesicle weight (Fig. 7B), increased serum LH (Fig. 7C), and decreased expression of two classical androgen-responsive genes (Fig. 7D) expressed in the kidney (30), all support the conclusion that Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice have hypoandrogenemia.

Fig. 7.

Male Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice have hypoandrogenemia. A, Testosterone was measured in testicular extracts of 180-d-old mice as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± sem of four to five mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). B, The seminal vesicle weights were recorded at different ages. Each point is the mean ± sem of three to four animals of a given age. If an error bar is not visible is because it falls within the symbol. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). C, Serum LH levels were measured in 180-d-old mice as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± sem of five to seven mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). D, The expression of the two androgen-responsive genes was assessed by real-time PCR using RNA isolated from the kidneys of 180-d-old mice. Each bar represents the mean ± sem of six different mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

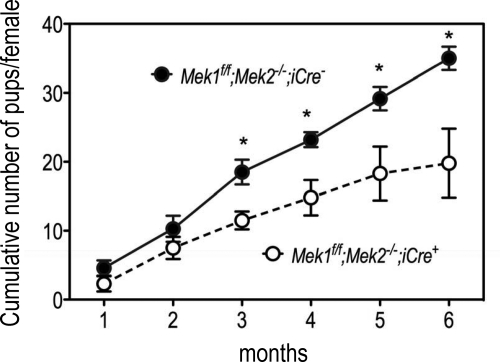

When paired with fertile Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− females, the fertility of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ males is normal for about 2 months but then starts to decline on the third month, and by 6 months, the cumulative number of pups sired by Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ males is only approximately 50% of those sired by Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− males (Fig. 8). At the end of the 6-month observation period, the number of litters and the number of pups/litter were also reduced in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice from 5.7 ± 0.2 to 3.8 ± 0.6 (P < 0.05) and from 6.2 ± 0.3 to 4.8 ± 0.5 (P < 0.05), respectively. Conversely, the number of days between litters was increased from 27 ± 1 to 31 ± 1 (P < 0.05) in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−; iCre+ mice.

Fig. 8.

Reduced fertility in male Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Thirty-five-day-old male Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− or Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice were housed with 2- to 3-month-old Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− females (one pair per cage) and the number of pups born recorded on a monthly basis. Each point is the mean ± sem of four pairs. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

The reduced fertility of the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ males is not due to low sperm counts or motility (Table 1). However, the number of vaginal plugs detected when Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− females are paired with Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ males is much lower than when they are paired with Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− males (Table 1). The pregnancy rate and the average number of pups/littler are also reduced when Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ males are paired with Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− females (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fertility assessment in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice

| Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− | Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ | |

|---|---|---|

| Total epididymal sperm | 7.2 ± 0.7 × 106 | 8.5 ± 0.6 × 106 |

| Motile epididymal sperm | 5.0 ± 0.5 × 106 | 5.1 ± 0.3 × 106 |

| % motility | 70 ± 0.5 | 61 ± 2.9 |

| % vaginal plugs | 100% (12/12) | 40% (7/18)a |

| % pregnancy | 92% (11/12) | 17% (3/18)a |

| Pups/litter | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 1.9a |

Total and motile epididymal sperm were counted in 180-d-old mice as described in Materials and Methods. Each point is the mean ± sem of eight animals. To detect vaginal plugs and pregnancies, individual (150–180 d old) males (Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− or Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+) were placed in the same cage with three Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− females (60–90 d old) of known fertility in the afternoon. Starting the next morning, the females were examined for the presence of vaginal plugs, and those with a vaginal plug were placed in individual cages and kept there for 1 month to determine whether they were successfully impregnated and to determine the number of pups born. Females without a vaginal plug were kept together with the males for another 4 d and examined each morning and separated as described above if plugs were present. If no vaginal plugs were observed after a total of 5 d, the females were still separated and kept alone for 1 month and scored for pregnancy and the number of pups born. This experiment was done using a total of four (Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre−) or six (Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+) males each housed with three Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− females of known fertility.

Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

We conclude that the Leydig cell MEK/ERK cascade is important for postnatal androgen production and for male fertility but not for spermatogenesis.

Discussion

The proliferation and differentiation of the adult population of Leydig cells is uniquely dependent on the LHR (3, 5–7, 9), a seven-transmembrane receptor that utilizes cAMP as its principal second messenger (10). The LHR-dependent accumulation of cAMP, as well as the LHR-induced transactivation of the EGF receptor (EGFR), results in the coordinate activation of Ras and the MEK/ERK pathway in Leydig cell cultures (11, 31–34). The involvement of the MEK/ERK pathway as a mediator of the actions of LH on steroid synthesis, as well as on the proliferation and survival of adult Leydig cells, has been recently emphasized in a number of cell culture studies (11–16). The experiments presented here show for the first time that the MEK/ERK cascade is critical for the maintenance of a functional population of adult Leydig cells and for fertility in mice.

Conditional deletion of the Mek1 allele in Leydig cells in the context of a global Mek2 deletion was accomplished by crossing Mek1f/f;Mek2−/− and Cyp17iCre mice. Although the Cyp17 promoter allows for Cre expression in both fetal and adult Leydig cells (21, 22, 35), recombination of the Mek1 allele in the fetal Leydig cells appeared to be inconsequential, because there were no defects in fetal masculinization, testicular morphology on the day after birth, or the postnatal pattern of expression of a fetal Leydig cell marker. These findings are interesting, because there is increasing recognition that fetal and adult Leydig cells are regulated by different hormones (2, 8, 36), and our data suggest that they are also dependent on different intracellular pathways.

Recombination of the Mek1 allele in the postnatal population of Leydig cells is clearly detectable but not complete. In the context of the global Mek2 deletion, the extent of recombination of the Mek1 allele in Leydig cells is enough to prevent the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 when stimulated by hCG, a cAMP analog or Kit ligand. In contrast, however, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 stimulated by a more efficacious stimulus, such as EGF, is only partially reduced. These results obtained with hCG, cAMP, and EGF are in agreement with the finding that cAMP is quantitatively more important than EGF-like growth factors as a mediator of the hCG-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (34).

The MEK/ERK cascade clearly influences the number and functional properties of adult Leydig cells. The Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−; iCre+ mice display Leydig cell hypoplasia and the loss of some Leydig cell markers as early as 21 d of age (the onset of puberty). Other Leydig cell markers decrease later, but all of the markers tested were decreased in 50-d-old mice. In addition, the Leydig cells that remain in the testes at this age are deficient in testosterone synthesis even when cholesterol or P5 are provided as substrates. Our data on the number of Leydig cells/testis suggest that there is an initial increase in Leydig cell numbers only up to about postnatal d 35 in the testis of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+. This could be due to a differential effect of MEK1/2 on the Leydig cells that populate the testes before and after puberty. Alternatively, because the mice express Cre from the Cyp17 promoter, expression is expected to increase around puberty (Fig. 4B and Ref. 22), and this may result in more efficient deletion of the floxed Mek1 allele in the adult mice. The latter appears more likely, because the expression of Srd5a1, a marker of immature Leydig cells (22, 29, 37), was similar in the testis of adultMek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− and Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (data not shown).

The MEK/ERK pathway affects the proliferation and survival of primary cultures of Leydig cells (14, 16), and further studies will be required to determine whether only one or both of these contribute to the Leydig cell hypoplasia in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. The impairment in testosterone synthesis in the remaining Leydig cells is not due to a decrease in the LHR-dependent stimulation of cAMP synthesis. Instead, it appears to be due to decreased expression of several of the proteins and enzymes that participate in testosterone synthesis. MEK inhibitors decrease the expression of StAR in Leydig cells in culture (12, 15). The involvement of the MEK/ERK cascade on the expression of Cyp11a1 and Cyp17 in Leydig cells has not been investigated, but MEK inhibitors have been shown to decrease the expression of these two genes in granulosa and theca cells (38, 39). Moreover, the MEK/ERK cascade may also regulate the activity and/or expression of transcription factors, such as steroidogenic factor 1, which is known to coordinately regulate the expression of many steroidogenic enzymes (40). The decreased expression or activity of one or more of these could be responsible for the low testosterone response of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f; Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. A decrease in the expression or activity of the enzymes that participate in the conversion of P5 to testosterone seems to be particularly important, however, because testosterone synthesis is decreased even when primary cultures of Leydig cells are incubated with P5. Among these enzymes, the decreased expression of Cyp17 is likely to be particularly important, because progesterone synthesis is not reduced as much as testosterone synthesis in the primary cultures of Leydig cells of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ stimulated with cAMP analogs (data not shown).

The normal LHR-provoked cAMP response of Leydig cells from Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice is also interesting, because it shows that not all Leydig cell properties are modulated by the MEK/ERK cascade. This finding agrees well with the parallel decreases in the expression of the Lhcgr (Fig. 4C) and Leydig cell numbers in the testes of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice (Figs. 4C and 5B, respectively). When the expression of the Lhcgr in the testes is corrected for the number of Leydig cells in the 50-d-old testes (the age used for the functional studies in primary cultures), this ratio is 2.98 in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− and 2.21 in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. It should also be noted, however, that rodent Leydig cells have a large excess of spare LHR and that the LHR density can be substantially reduced without a corresponding decrease in LHR-provoked cAMP accumulation (41).

The Leydig cell hypoplasia and decreased functionality of the remaining Leydig cells in Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice ultimately result in hypoandrogenemia, but the manifestations of this change occur later in life. A decrease in seminal vesicle weight, one of the most sensitive indexes of hypoandrogenemia (42), is not evident until about 3 months of age. A decrease in intratesticular testosterone and in the expression of two androgen-responsive genes, as well as an increase in serum LH, were not detectable at 2–3 months of age (data not shown), but these changes were clearly evident at 6 months of age as shown here. We note that the approximately 40% reduction in intratesticular testosterone in the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−; iCre+ mice is low compared with the approximately 70% reduction in the number of Leydig cells in the testis and the almost complete loss of acute steroidogenic potential of the isolated Leydig cells. This could be due to a long half-life of intratesticular testosterone or to a slow conversion of precursors to testosterone. This finding is not entirely unexpected, however, because even the IGF-I or LHR null mice have measurable levels of intratesticular testosterone in spite of much more substantial reductions in Leydig cell numbers and responsiveness (5, 29) than those reported here.

Reduced fertility is also detectable starting at about 3 months of age but is not due to low sperm counts or decreased sperm motility. It is associated with a reduction in seminal plug occurrence, which may be secondary to the hypoandrogenemia-induced atrophy of the seminal vesicles (43, 44) and/or changes in copulatory behavior (45). Ultimately, the ablation of the MEK/ERK pathway in Leydig cells results in Leydig cell hypoplasia and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism.

The main physiological stimulator of the MEK/ERK cascade in adult Leydig cells is not known, but there are four candidates worth considering, EGFR ligands, Kit ligand, IGF-I, and LH. Engagement of the EGFR results in robust activation of the MEK/ERK cascade in Leydig cells in culture (11, 14, 16, 31, 33), and EGF-like growth factors are partial mediators of the LHR-provoked activation of the MEK/ERK cascade in Leydig cells (13, 14, 31–33). At least one member of the EGF family of ligands, TGFα, has been identified as an intratesticular factor that affects Leydig cells (46), but several mouse models with disruptions in the EGFR or TGFα are fertile and do not have overt abnormalities in testicular functions (47–50). We also show here that the EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is only partially reduced in the Leydig cells of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Kit ligand is a product of Sertoli cells, and it acts on c-kit present in Leydig cells and spermatogonia (51). Although the engagement of c-kit has been traditionally associated with activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/serine-threonine kinase (AKT) pathway (51, 52), it also results in activation of the MEK/ERK cascade in Leydig cells as shown here. Our data also show that the stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation provoked by engagement of c-kit is absent in the Leydig cells of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice. Kit ligand influences the proliferation and/or survival of the adult population of Leydig cells (53), but it is not known if its actions are mediated by the MEK/ERK or the PI3K/AKT pathways. Likewise, mice harboring a knock-in mutation of c-kit that prevents PI3K/AKT activation have several testicular abnormalities, but these are more likely to be mediated by changes in the germ cells (that also express c-kit) rather than in the Leydig cells (54–56). IGF-I induces a robust stimulation of PI3K/AKT and a relatively weak stimulation of the MEK/ERK cascade in Leydig cells (16). Like Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice, IGF-I null mice display a reduced expression of several Leydig cell markers, Leydig cell hypoplasia, and impaired testosterone synthesis (29, 57). In contrast to the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice, however, the IGF-I null mice are completely infertile, show a substantial reduction in testicular weight and sperm counts (58), and their testes have increased expression of Srd5a1, a marker of immature Leydig cells (29). Like the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice, the prenatal development of Leydig cells in the LHR null mice is normal, but the adults display reduced expression of many Leydig cell steroidogenic enzymes, and they develop Leydig cell hypoplasia, hypoandrogenemia, and high gonadotropin levels (5, 59, 60). In contrast to the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice, however, the LHR null mice are cryptorchid, and they have a pronounced reduction in testicular weight, arrested spermatogenesis, and complete infertility (5, 59, 60). The phenotype of the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ mice is thus unique, and a comparison with the phenotype of the LHR null mice suggests that not only the proliferative responses but also some the effects of the LHR on the expression of steroidogenic enzymes in the adult Leydig cells are mediated by the MEK/ERK cascade.

There are two other recent reports on the effects of the MEK/ERK cascade on reproduction. A deletion of ERK1/2 from granulosa cells completely prevents the LH-induced ovulatory response (61), whereas a deletion of ERK1/2 from the anterior pituitary preferentially inhibits LHb biosynthesis in females and prevents ovulation but does not affect fertility or other testicular functions in males (62). Together with the data presented here, it thus appears that the MEK/ERK cascade is essential for fertility in females in at least two aspects, the synthesis and actions of LH, whereas in the male, it is more involved in LH actions than LH synthesis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mek1f/f;Mek2−/− mice are in a 129Sv background (17–20), and Cyp17iCre are in a C57Bl/6 background (21). The mixed background colony of Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ was maintained by crossing Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre+ females with Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− males. Although a few experiments used 129Sv wt mice as controls (see figure legends), most of them used the Mek1f/f;Mek2−/−;iCre− littermates as controls. All animals were genotyped using tail genomic DNA and PCR amplification as described (17–21). All animal procedures used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for the University of Iowa.

LH assays

These were done by the University of Virginia Ligand Core Facility, which is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through a U54 Center Grant (U54-HD28934).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Testes were fixed in formaldehyde (63) and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard conditions or incubated with antibodies against MEK1 (no. 1518-1; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) or Cyp11a1 (no. AB1244; Chemicon, Bedford, MA). These were eventually visualized using the Vectastain ABC-alkaline phosphatase kits from Vector Labs (Burlingame, CA) and either the Vector blue (MEK1) or Vector red (Cyp11a1) substrates.

Testicular lysates, RNA, and genomic DNA

Lysates were prepared by placing one decapsulated testis in 300–400 μl of a buffer containing 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 1 mm NaF (pH 7.4) supplemented with a commercial mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and homogenized by hand with a Teflon/glass homogenizer. The homogenates were kept in ice for 30 min, clarified by centrifugation, and used immediately or stored at −80 C until used. In some experiments, the clarified lysates from three testes were combined. This was done by first measuring the protein content, equalizing it in all extracts, and then mixing equal volumes of each extract.

Testicular and renal RNA was prepared from decapsulated testis or kidney that had been homogenized in 2 ml of Trizol using a Polytron homogenizer. Testicular genomic DNA was also prepared from decapsulated testes using a kit from ViaGen (Austin, TX) according to their instructions.

Primary cultures of Leydig cells

Testicular interstitial cells were isolated basically as described by O'Shaughnessy et al. (64). The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm filter, the cells were recovered by centrifugation, resuspended in DMEM/F12 without phenol red but containing 10 mm HEPES, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, insulin (10 μg/ml), transferrin (5.5 μg/ml), and selenium (5 ng/ml) (pH 7.4), plated in fibronectin-coated 48-well plates, and maintained at 34 C. Residual germ cells were removed by vigorously washing the wells on the first and second day after plating. The cells were vigorously washed with the medium described above three times. After the washes, on the second day, the cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 without phenol red but containing 20 mm HEPES, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 1 mg/ml BSA (pH 7.4) (Assay Medium) for 18–24 h before starting an experiment.

The cells from one mouse were always plated into four wells. Two of the wells were used for the cAMP or steroid assays (one control and one stimulated), and the other two were used to measure protein to normalize the data obtained.

For the cAMP assays, the wells were washed twice with 200 μl of Assay Medium and then preincubated in 200 μl of Assay Medium containing 1 mm methyl-isobutyl xanthine (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor) for 15 min at 34 C. Buffer or hCG was then added, and the incubation was continued for another 30 min at 34 C. The reaction was stopped by adding 200 μl of 2 n perchloric acid containing 1 mm theophylline. cAMP was measured in the neutralized extracts by RIA as described elsewhere (14). For the testosterone assays, the wells were washed twice with 200 μl of Assay Medium and then incubated in 500 μl of Assay Medium containing buffer, hCG, or Bt2cAMP (generally added as 25 μl aliquots) for 4 h at 34 C or in 500 μl of Assay Medium containing ethyl alcohol, 22OHC, or P5 (added as 5 μl aliquots) for 4 h at 34 C. Testosterone and progesterone were then measured by RIA in suitable aliquots of incubation medium (14). For the ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays, the cells were washed twice with 200 μl of Assay Medium and then incubated in 500 μl of Assay Medium with the different stimuli as detailed in the figure legends. At the end of the incubation, the medium was aspirated, the cells were washed twice with cold buffer [20 mm HEPES and 150 mm NaCl (pH 7.4)], lysed, and used to measure total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 in Western blottings as described elsewhere (14).

Intratesticular testosterone

One decapsulated testes was homogenized in 1.5 ml of 70% ethanol using a Polytron homogenizer, the homogenate was allowed to sit overnight at room temperature and clarified by centrifugation. Residual methanol in the supernatant was evaporated in a fume hood, and the remaining aqueous solution was extracted twice with 2 ml of ethyl ether. The ether extracts were evaporated, dissolved by vigorous vortexing in 10 mm sodium phosphate and 150 mm NaCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mg/ml BSA, and used to measure testosterone by RIA as described above.

Western blottings

These were done as described earlier (14) using 2–15 μg of lysate protein (depending on the use of Leydig cell culture or testicular lysates and the antigen being detected). The solutions used to block and wash the membranes and perform the primary and secondary antibody incubations contained either 5% milk or 1–5% BSA depending on the antigen being detected. The length (1–18 h) and temperature (4 C or ambient) of the incubation and the dilutions of the primary antibodies also varied depending on the antigen being detected. The secondary antibody dilution (1/3000) and length and temperature of incubation (1 h at room temperature) was constant, however, and was done using antimouse or antirabbit antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (catalog no. 170-6515; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The immune complexes in the Western blottings were eventually visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) and exposed to film. The source of antibodies was as follows: pERK1/2 (no. 9122; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), ERK1/2 (no. 06-182; Millipore, Bedford, MA), MEK1 and MEK2 (nos. 1518-1 and 1236-1, respectively; Epitomics), VASA (no. 13840; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Cyp11a1 (no. AB1244; Chemicon), DMRT (kindly provided by Leslie Heckert of the Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS), clusterin (no. 6420; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), StAR (kindly provided by Doug Stocco of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX), Sult1e1 (kindly provided by Wen-Chao Song of The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), Cyp17 (kindly provided by Buck Hales of Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (no. 2118; Cell Signaling).

Real-time PCR

Detection of specific mRNA was done and quantitated using real-time PCR as previously described (65). Primers used were as follows. Tsp2: forward, GTC CGG ACT CTA TGG CAT GAC and reverse, TGT GAA TCA GGT GCC ACC TG. Lhcgr: forward, CCT TGT GGG TGT CAG CAG TTA and reverse, TTG TGA CAG AGT GGA TTC CAC AT. Gus: forward, GGC TGG TGA CCT ACT GGA TTT and reverse, GGC ACT GGG AAC CTG AAG T. Rp2: forward, TAG ACT GCA CGC CTG ACA TCT and reverse, TGA TGG GGA CAA CCA CTG GTA. Gapdh: forward, GAC GGC CGC ATC TTC TTG T and reverse, ACC GAC CTT CAC CAT TTT GTC T.

Testicular Leydig cell counts

These were basically determined as described by others (9, 29, 66), with some modifications as follows. The fixed testes were cut in thirds, and each third was cut in 5-μm sections. Three randomly chosen, nonadjacent sections from each testicular third were selected and stained with Cyp11a1 antibody (see above) to identify the Leydig cells. Four randomly selected fields form each section were captured at a ×200 magnification using an Olympus BX21 microscope equipped with a digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The number of Leydig cells in each field was counted (this number ranged from ∼5 to ∼120 cells, depending on genotype and age), thus giving 12 different values for each testis analyzed. The number of Leydig cells/mm3 was calculated based on the known area of the fields analyzed (0.3522 mm2) and the thickness of the sections (5 μm). The number of Leydig cells/testis was then calculated from the known average weight of the testis of a given genotype and age (see Fig. 4B) and assuming a testicular density of 1 g/ml.

Sperm counts and motility

All procedures were done at room temperature. The epididymes were placed in mineral oil, trimmed of excess fat, transferred to a 500 ml aliquot of M2 medium supplemented with 3 mg/ml BSA, and covered with mineral oil. The cauda was punctured several times with a 25 gauge hypodermic needle under a dissecting microscope, and the sperm were expressed by gentle pressure. After removing the epididymis, the expressed sperm were mixed by repeated pipeting. A 10 μl aliquot was placed in a Makler chamber, and immotile sperm were counted under a microscope at ×200 magnification. The Makler chamber was subsequently heated at 50–55 C for 2 min to immobilize all motile sperm and counted again. Motile sperm concentration was calculated by subtracting the immotile sperm counted before heating from the immotile sperm counted after heating.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Sparks for help with the sperm counting and Nebojsa Andric and Debbie Segaloff for helpful comments and for reading the manuscript. M.A. would like to dedicate this publication to the memory of Anita Payne, a friend and a pioneer in the study of Leydig cells.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant CA-40629 (to M.A.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AKT

- Serine-threonine kinase

- Bt2

- dibutyryl

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- hCG

- human choriogonadotropin

- LHR

- LH receptor

- MEK

- MAPK kinase

- 22OHC

- 22-hydroxycholesterol

- P5

- pregnenolone

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- StAR

- steroidogenic acute regulatory protein.

References

- 1. Yao HH-C, Barsoum I. 2007. Fetal Leydig cells: origin, regulation, and functions. In: Payne AH, Hardy MP. eds. The Leydig cell in health and disease. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 47–54 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scott HM, Mason JI, Sharpe RM. 2009. Steroidogenesis in the fetal testis and its susceptibility to disruption by exogenous compounds. Endocr Rev 30:883–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Morris ID, Huhtaniemi I, Baker PJ, Abel MH. 2009. Role of androgen and gonadotrophins in the development and function of the Sertoli cells and Leydig cells: data from mutant and genetically modified mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol 306:2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ge R, Hardy MP. 2007. Regulation of Leydig cells during pubertal development. In: Payne AH, Hardy MP. eds. The Leydig cell in health and disease. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 55–70 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang FP, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I. 2001. Normal prenatal but arrested postnatal sexual development of luteinizing hormone receptor knockout (LuRKO) mice. Mol Endocrinol 15:172–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lei ZM, Mishra S, Zou W, Xu B, Foltz M, Li X, Rao CV. 2001. Targeted disruption of luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin receptor gene. Mol Endocrinol 15:184–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Baker P, Sohnius U, Haavisto AM, Charlton HM, Huhtaniemi I. 1998. Fetal development of Leydig cell activity in the mouse is independent of pituitary gonadotroph function. Endocrinology 139:1141–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basciani S, Mariani S, Spera G, Gnessi L. 2010. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in the testis. Endocr Rev 31:916–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baker PJ, O'Shaughnessy PJ. 2001. Role of gonadotropins in regulating numbers of Leydig and Sertoli cells during fetal and postnatal development in mice. Reproduction 122:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. 2002. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor. A 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev 23:141–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirakawa T, Ascoli M. 2003. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR)-induced phosphorylation of the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) in Leydig cells is mediated by a protein kinase A-dependent activation of Ras. Mol Endocrinol 17:2189–2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martinelle N, Holst M, Söder O, Svechnikov K. 2004. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology 145:4629–4634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Evaul K, Hammes SR. 2008. Cross-talk between G protein-coupled and epidermal growth factor receptors regulates gonadotropin-mediated steroidogenesis in Leydig cells. J Biol Chem 283:27525–27533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shiraishi K, Ascoli M. 2007. Lutropin/choriogonadotropin (LH/CG) stimulate the proliferation of primary cultures of rat Leydig cells through a pathway that involves activation of the ERK1/2 cascade. Endocrinology 148:3214–3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manna PR, Huhtaniemi IT, Stocco DM. 2009. Mechanisms of protein kinase C signaling in the modulation of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated steroidogenesis in mouse gonadal cells. Endocrinology 150:3308–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tai P, Shiraishi K, Ascoli M. 2009. Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) inhibits apoptosis of immature leydig cells in primary culture. Endocrinology 150:3766–3773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bélanger LF, Roy S, Tremblay M, Brott B, Steff AM, Mourad W, Hugo P, Erikson R, Charron J. 2003. Mek2 is dispensable for mouse growth and development. Mol Cell Biol 23:4778–4787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bissonauth V, Roy S, Gravel M, Guillemette S, Charron J. 2006. Requirement for Map2k1 (Mek1) in extra-embryonic ectoderm during placentogenesis. Development 133:3429–3440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scholl FA, Dumesic PA, Barragan DI, Harada K, Bissonauth V, Charron J, Khavari PA. 2007. Mek1/2 MAPK kinases are essential for mammalian development, homeostasis and Raf-induced hyperplasia. Dev Cell 12:615–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scholl FA, Dumesic PA, Barragan DI, Charron J, Khavari PA. 2009. Mek1/2 gene dosage determines tissue response to oncogenic Ras signaling in the skin. Oncogene 28:1485–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bridges PJ, Koo Y, Kang DW, Hudgins-Spivey S, Lan ZJ, Xu X, DeMayo F, Cooney A, Ko C. 2008. Generation of Cyp17iCre transgenic mice and their application to conditionally delete estrogen receptor α (Esr1) from the ovary and testis. Genesis 46:499–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Willerton L, Baker PJ. 2002. Changes in Leydig cell gene expression during development in the mouse. Biol Reprod 66:966–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Castrillon DH, Quade BJ, Wang TY, Quigley C, Crum CP. 2000. The human VASA gene is specifically expressed in the germ cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:9585–9590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raymond CS, Murphy MW, O'Sullivan MG, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. 2000. Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Genes Dev 14:2587–2595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stocco DM. 2007. The role of StAR in Leydig cell steroidogenesis. In: Payne AH, Hardy MP. eds. The Leydig cell in health and disease. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 149–155 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Payne AH. 2007. Steroidogenic enzymes in Leydig cells. In: Payne AH, Hardy MH. eds. The Leydig cell in health and disease. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 157–171 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song WC, Moore R, McLachlan JA, Negishi M. 1995. Molecular characterization of a testis-specific estrogen sulfotransferase and aberrant liver expression in obese and diabetogenic C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Endocrinology 136:2477–2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mattmueller DR, Hinton BT. 1991. In vivo secretion and association of clusterin (SGP-2) in luminal fluid with spermatozoa in the rat testis and epididymis. Mol Reprod Dev 30:62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hu GX, Lin H, Chen GR, Chen BB, Lian QQ, Hardy DO, Zirkin BR, Ge RS. 2010. Deletion of the Igf1 gene: suppressive effects on adult Leydig cell development. J Androl 31:379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berger FG, Watson G. 1989. Androgen-regulated gene expression. Annu Rev Physiol 51:51–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shiraishi K, Ascoli M. 2008. A co-culture system reveals the involvement of intercellular pathways as mediators of the lutropin receptor (LHR)-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in Leydig cells. Exp Cell Res 314:25–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Galet C, Ascoli M. 2008. Arrestin-3 is essential for the activation of Fyn by the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells. Cell Signal 20:1822–1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shiraishi K, Ascoli M. 2006. Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells stimulates tyrosine kinase cascades that activate Ras and the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK1/2). Endocrinology 147:3419–3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tai P, Ascoli M. 17 February 2011. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a critical role in the cAMP-induced activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in Leydig cells. Mol Endocrinol 10.1210/me.2010-0489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Greco TL, Payne AH. 1994. Ontogeny of expression of the genes for steroidogenic enzymes P450 side- chain cleavage, 3 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, P450 17 α-hydroxylase/C17–20 lyase, and P450 aromatase in fetal mouse gonads. Endocrinology 135:262–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Fowler PA. 2011. Endocrinology of the mammalian fetal testis. Reproduction 141:37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coonce MM, Rabideau AC, McGee S, Smith K, Narayan P. 2009. Impact of a constitutively active luteinizing hormone receptor on testicular gene expression and postnatal Leydig cell development. Mol Cell Endocrinol 298:33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Denner L, Bodenburg YH, Jiang J, Pagès G, Urban RJ. 2010. Insulin-like growth factor-I activates extracellularly regulated kinase to regulate the P450 side-chain cleavage insulin-like response element in granulosa cells. Endocrinology 151:2819–2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tajima K, Yoshii K, Fukuda S, Orisaka M, Miyamoto K, Amsterdam A, Kotsuji F. 2005. Luteinizing hormone-induced extracellular-signal regulated kinase activation differently modulates progesterone and androstenedione production in bovine theca cells. Endocrinology 146:2903–2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin LJ, Tremblay JJ. 2010. Nuclear receptors in Leydig cell gene expression and function. Biol Reprod 83:3–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mendelson C, Dufau M, Catt K. 1975. Gonadotropin binding and stimulation of cyclic adenosine 3′:5′-monosphosphate and testosterone production in isolated Leydig cells. J Biol Chem 250:8818–8823 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cunha GR, Alarid ET, Turner T, Donjacour AA, Boutin EL, Foster BA. 1992. Normal and abnormal development of the male urogenital tract. Role of androgens, mesenchymal-epithelial interactions, and growth factors. J Androl 13:465–475 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peitz B, Olds-Clarke P. 1986. Effects of seminal vesicle removal on fertility and uterine sperm motility in the house mouse. Biol Reprod 35:608–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pang SF, Chow PH, Wong TM. 1979. The role of the seminal vesicles, coagulating glands and prostate glands on the fertility and fecundity of mice. J Reprod Fertil 56:129–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. James PJ, Nyby JG. 2002. Testosterone rapidly affects the expression of copulatory behavior in house mice (Mus musculus). Physiol Behav 75:287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Teerds KJ, Rommerts FF, Dorrington JH. 1990. Immunohistochemical detection of transforming growth factor-α in Leydig cells during the development of the rat testis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 69:R1–R6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Luetteke NC, Phillips HK, Qiu TH, Copeland NG, Earp HS, Jenkins NA, Lee DC. 1994. The mouse waved-2 phenotype results from a point mutation in the EGF receptor tyrosine kinase. Gene Dev 8:399–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Du X, Tabeta K, Hoebe K, Liu H, Mann N, Mudd S, Crozat K, Sovath S, Gong X, Beutler B. 2004. Velvet, a dominant Egfr mutation that causes wavy hair and defective eyelid development in mice. Genetics 166:331–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luetteke NC, Qiu TH, Peiffer RL, Oliver P, Smithies O, Lee DC. 1993. TGFα deficiency results in hair follicle and eye abnormalities in targeted and waved-1 mice. Cell 73:263–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mann GB, Fowler KJ, Gabriel A, Nice EC, Williams RL, Dunn AR. 1993. Mice with a null mutation of the TGFα gene have abnormal skin architecture, wavy hair, and curly whiskers and often develop corneal inflammation. Cell 73:249–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Loveland KL, Schlatt S. 1997. Stem cell factor and c-kit in the mammalian testis: lessons originating from mother nature's gene knockouts. J Endocrinol 153:337–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bedell MA, Mahakali Zama A. 2004. Genetic analysis of Kit ligand functions during mouse spermatogenesis. J Androl 25:188–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yan W, Kero J, Huhtaniemi I, Toppari J. 2000. Stem cell factor functions as a survival factor for mature Leydig cells and growth factor for precursor Leydig cells after dimethane sulfonate treatment: implication of a role of the stem cell factor/c-kit system in Leydig cell development. Dev Biol 227:169–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kissel H, Timokhina I, Hardy MP, Rothschild G, Tajima Y, Soares V, Angeles M, Whitlow SR, Manova K, Besmer P. 2000. Point mutation in Kit receptor tyrosine kinase reveals essential roles for Kit signaling in spermatogenesis and oogenesis without affecting other Kit responses. EMBO J 19:1312–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Blume-Jensen P, Jiang G, Hyman R, Lee KF, O'Gorman S, Hunter T. 2000. Kit/stem cell factor receptor-induced activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase is essential for male fertility. Nat Genet 24:157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rothschild G, Sottas CM, Kissel H, Agosti V, Manova K, Hardy MP, Besmer P. 2003. A role for Kit receptor signaling in Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Biol Reprod 69:925–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang G, Hardy MP. 2004. Development of Leydig cells in the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) knockout mouse: effects of IGF-I replacement and gonadotropic stimulation. Biol Reprod 70:632–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Baker J, Hardy MP, Zhou J, Bondy C, Lupu F, Bellvé AR, Efstratiadis A. 1996. Effects of an Igf1 gene null mutation on mouse reproduction. Mol Endocrinol 10:903–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang FP, Pakarainen T, Zhu F, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I. 2004. Molecular characterization of postnatal development of testicular steroidogenesis in luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mice. Endocrinology 145:1453–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pakarainen T, Zhang FP, Mäkelä S, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I. 2005. Testosterone replacement therapy induces spermatogenesis and partially restores fertility in luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mice. Endocrinology 146:596–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fan HY, Liu Z, Shimada M, Sterneck E, Johnson PF, Hedrick SM, Richards JS. 2009. MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2) in ovarian granulosa cells are essential for female fertility. Science 324:938–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bliss SP, Miller A, Navratil AM, Xie J, McDonough SP, Fisher PJ, Landreth GE, Roberson MS. 2009. ERK signaling in the pituitary is required for female but not male fertility. Mol Endocrinol 23:1092–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Latendresse JR, Warbrittion AR, Jonassen H, Creasy DM. 2002. Fixation of testes and eyes using a modified Davidson's fluid: comparison with Bouin's fluid and conventional Davidson's fluid. Toxicol Pathol 30:524–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Baker PJ, Heikkilä M, Vainio S, McMahon AP. 2000. Localization of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/17-ketosteroid reductase isoform expression in the developing mouse testis—androstenedione is the major androgen secreted by fetal/neonatal Leydig cells. Endocrinology 141:2631–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Donadeu FX, Ascoli M. 2005. The differential effects of the gonadotropin receptors on aromatase expression in primary cultures of immature rat granulosa cells are highly dependent on the density of receptors expressed and the activation of the inositol phosphate cascade. Endocrinology 146:3907–3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hardy MP, Zirkin BR, Ewing LL. 1989. Kinetic studies on the development of the adult population of Leydig cells in testes of the pubertal rat. Endocrinology 124:762–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]