Abstract

A requisite step in the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is the insertion of the viral genome into that of the host cell, a process catalyzed by the 288-amino-acid (32-kDa) viral integrase (IN). IN recognizes and cleaves the ends of reverse-transcribed viral DNA and directs its insertion into the chromosomal DNA of the target cell. IN function, however, is not limited to integration, as the protein is required for other aspects of viral replication, including assembly, virion maturation, and reverse transcription. Previous studies demonstrated that IN is comprised of three domains: the N-terminal domain (NTD), catalytic core domain (CCD), and C-terminal domain (CTD). Whereas the CCD is mainly responsible for providing the structural framework for catalysis, the roles of the other two domains remain enigmatic. This study aimed to elucidate the primary and subsidiary roles that the CTD has in protein function. To this end, we generated and tested a nested set of IN C-terminal deletion mutants in measurable assays of virologic function. We discovered that removal of up to 15 residues (IN 273) resulted in incremental diminution of enzymatic function and infectivity and that removal of the next three residues resulted in a loss of infectivity. However, replication competency was surprisingly reestablished with one further truncation, corresponding to IN 269 and coinciding with partial restoration of integration activity, but it was lost permanently for all truncations extending N terminal to this position. Our analyses of these replication-competent and -incompetent truncation mutants suggest potential roles for the IN CTD in precursor protein processing, reverse transcription, integration, and IN multimerization.

INTRODUCTION

The defining hallmarks of retroviruses are reverse transcription of the viral genomic information as encoded in polyadenylated RNA and the subsequent integration of the copied DNA genome into that of a host cell. The latter is an essential and irreversible event which is mediated by the catalytic activities of the viral integrase protein (IN), the recent target of successful chemotherapeutic intervention against HIV-1 infection (1). HIV-1 IN is a 288-amino-acid, 32-kDa protein that is cleaved from the C terminus of the Gag-Pol polyprotein (Pr160Gag-Pol) via viral proteolytic activity. The biochemical mechanisms that lead to retroviral integration, which have been extensively studied in vitro, are defined by two catalytically related and sequentially dependent steps (18) which may be distinguished by their respective sensitivities to current inhibitors of IN function (39). Following the completion of reverse transcription of the viral RNA into its DNA copy, IN removes two nucleotides from the 3′ end of each strand of the viral DNA. This step, termed 3′ processing, generates a chemically reactive 3′-hydroxyl group (CAOH-3′) at the 3′ ends of the DNA molecule, effectively activating the termini for the subsequent reaction (strand transfer). This enzymatic step is the target of all IN inhibitors currently in clinical use. During strand transfer, IN catalyzes a concerted cleavage-ligation reaction in which the previously activated CAOH-3′ groups attack the host chromosome on opposite sides of the DNA helix, producing for HIV-1 a characteristic 5-base-pair staggered cut while simultaneously forming stable covalent bonds between the inserted viral DNA and that of the host cell. The resulting product consists of chromosomal DNA covalently linked to the 3′ ends of viral DNA. Single-stranded gaps and unpaired viral 5′ ends at the recombinant joints are repaired by host factors that restore the integrity of chromosomal DNA. The viral DNA thus becomes contiguous with and indistinguishable from host DNA, with the chromosome serving as a sanctuary for the expression of viral information as well as providing a mechanism for the generational perpetuation of viral genetic information.

Investigation of HIV-1 IN during infection has presented an especially difficult challenge due in part to the multifunctionality of the protein. Apart from its unique role in integration, IN is required for a diverse cohort of processes during several stages of the viral life cycle (27). IN has been found to affect the precision both of the proteolytic processing of viral polyprotein precursors in producer cells and of viral particle morphogenesis (6), as well as the efficiency of reverse transcription in recipient target cells (20, 47, 58, 71, 79, 82). For descriptive purposes, a standardized nomenclature has been adopted to categorize IN mutant phenotypes based on the viral processes affected. For class I IN mutations, viruses are efficiently produced and are otherwise infectious, as they proceed through all stages of the life cycle, including reverse transcription and viral DNA nuclear import. However, the IN-dependent catalytic functions of 3′ processing and strand transfer are absent or attenuated, and thus class I mutants produce unprocessed, blunt-ended linear viral DNA intermediates that, when transported into the nuclear compartment, are expeditiously self-ligated to produce circularized viral DNA molecules (two-long terminal-repeat [2-LTR] circles). The accumulation of 2-LTR circles is a signature feature of this mutant phenotypic class, and because the host DNA ligation activity responsible for their formation is resident in the nuclear compartment, the synthesis of 2-LTR circles is used as a surrogate marker for successful nuclear import of viral DNA. In contrast, class II (24a) IN mutants, a broader phenotypic designation, manifest a range of pleiotropic effects, the most obvious being loss of efficient reverse transcription of the viral genome during viral infection. Class II mutants also can exhibit defective polyprotein processing and aberrant virion maturation profiles, resulting in inefficient egress from producer cells with the potential for concomitant effects during the infection of target recipient cells.

Evidence for a three-domain structural model of HIV-1 IN has been corroborated via several methodologies, including comparison of retroelement phylogeny (26), limited proteolysis (26), intragenic complementation studies (25, 31, 73), and structural data (8, 12, 22–24, 33, 51, 73, 76). The N-terminal domain (NTD) encompasses residues 1 to 50 and contains a conserved HHCC zinc finger motif that has been demonstrated in vitro to coordinate zinc ions (7, 81). This motif is requisite for proper NTD folding and IN multimerization and contributes to integrase-mediated catalytic activity (81). Residues 50 to 212 comprise the catalytic core domain (CCD), a region specifying a constellation of invariant acidic residues (D64, D116, and E152), a catalytic triad that is indispensable for integrase-mediated enzymatic activity. Mutation of any of these residues abrogates the catalytic functions of IN both in vitro (21, 26, 46, 72) and in the context of viral replication (27, 47, 78), and the mutant viruses thus elicited are characterized as paradigmatic class I mutants. The C-terminal domain (CTD), demarcated by residues 212 to 288, is the least conserved of the three domains, even among HIV-1 viral isolates. Of note is the presence of an SH3-like structural motif (amino acids 220 to 270) within this domain; the folding topology of the monomeric unit is a five-stranded beta-barrel existing in solution as an isolated homodimer (23, 24). This element is also maintained within the context of a two-domain CCD-CTD crystallographic structure (12). Structural data for the CTD end at this outer margin, with the remaining 18 residues (amino acids 271 to 288) proving recalcitrant to structural determination due a higher level of disorder; this region is referred to here as the IN CTD “tail”.

There is evidence to suggest that the IN CTD exhibits conformational flexibility and undergoes a detectable structural rearrangement during both CCD-coordinated divalent metal binding (discriminating monoclonal antibody reactivity) (3, 4) and DNA binding (subunit-specific protein footprinting) (80). Functions attributed to the IN CTD include enhancement of IN multimerization (43), nonspecific and, presumptively, specific DNA binding capabilities (19, 28, 29, 38, 41, 44, 55, 56, 74), and facilitation of host factor binding (2, 10, 35, 54, 63, 75). Reports also highlight a direct and apparently functional interaction between IN and reverse transcriptase (RT) (40, 69, 77, 79, 82), with recent evidence suggesting that this association is mediated through the CTD (40, 77). Further illustration of the significant role played by the CTD in orchestrating secondary IN activities has been demonstrated by a study of the mutagenic substitution of the highly conserved CTD residues shared between HIV-1 isolates (53). This analysis revealed that an overwhelming majority of the generated mutants had a class II phenotype (53). Taken together, the above observations highlight the potentially significant role of the CTD in orchestrating secondary IN activities and implicate this domain in coordinating a wide range of IN activities throughout the viral life cycle.

It has recently been shown that the HIV-1 IN CTD is a potent substrate for p300-mediated histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity (10, 70) at three lysine residues (K264, K266, and K273), a phenomenon subsequently demonstrated to be nonessential for sustained viral replication through an immortalized T cell line (70). Interestingly, K273 may also be targeted for posttranslational ubiquitinylation (61). Modification by polyubiquitin addition is required for manifestation of the exquisite sensitivity of HIV-1 IN to proteasomal degradation (64, 68). To accelerate our further investigation of these posttranslational modifications, we created a series of IN truncations. We report here our investigation of IN C-terminal truncations within a mutagenic window of 28 amino acids (IN deletions 260 to 288), with the aim of gradually removing the tail region and several subsequent residues encroaching into the SH3 fold and observing the effect on a variety of measurable processes during viral replication. We found that stepwise removal of 15 residues from the C terminus of IN, up to K273, resulted in a gradual attenuation of infectivity. Truncations of the CTD beyond this point, corresponding to IN lengths of 272, 271, and 270 residues, resulted in a sudden loss of infectivity. Remarkably, it was discovered that viral infectivity was rescued with the removal of a single, consecutive residue to form IN 269. Further truncation in the N-terminal direction after the 269 residue resulted again in a loss of infectivity, with the IN mutants exhibiting more deleterious defects. The examination and characterization of these mutants move forward our understanding of the contributions made by the IN CTD to IN structure and function and, in a broader sense, to HIV-1 replication itself.

Such a carboxyl-terminal truncation scheme for HIV-1 IN has been independently reported (17). Much of the data involved in vitro characterization of IN protein mutants each possessing a residual foreign 4-amino-acid tag at the C terminus to facilitate protein purification. However, in the earlier study the mutagenic resolution was sequential deletion of three amino acids instead of the set of single-amino-acid deletion mutants described here. As such, certain significant attributes of tail function, which could have been revealed by a more comprehensive truncation analyses, were missed. As our data suggest, viral dynamics become particularly sensitive to perturbation at a short enough length of the tail region, and thus the appendage of any number of amino acid residues can certainly influence the biochemical behavior of a particular IN mutant. We do, however, concur from our analyses that the integrity of the SH3 fold appears to be important for the precision of polyprotein processing and viral assembly in the late stage of infection. Our conclusions show that the IN tail is not required for secondary IN functions but instead appears to play a role during the 3′ processing reaction and/or perhaps to facilitate the functional assembly of the intasome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of integrase mutants.

The HXB2-related virus R7/3(X/S) (52, 70) was used as the reference, wild-type virus for the studies presented here. Its cognate proviral molecular clone, plasmid pR7/3(X/S) (Fig. 1), contains an XbaI restriction site at the 5′ end of the integrase-coding region and a SacII restriction site near its 3′ end, with the sites being silent with respect to the overlapping viral coding frames and allowing for a cloning strategy that provides unbiased comparisons to be made against an otherwise isogenic background. Thus, using overlap PCR mutagenesis [with a pR7/3(X/S) template and outside oligonucleotide primers specifying XbaI and SacII sites], a series of translational nonsense mutations (amber) were introduced at sequential codon positions to create a nested set of single-amino-acid deletions originating from the IN C terminus. All mutant proviral clones were verified by DNA sequence analysis of the entire XbaI/SacII recombinant joint. Wild-type and mutant XbaI/SacII inserts were also reconstructed into pR7/3(X/S)Bsd (52, 70), an env− proviral derivative in which the amino terminus of nef is replaced with bsd, a gene conferring resistance to the microbial antibiotic blasticidin S. Single-step infectious, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped viral stocks were prepared by cotransfection of the pR7/3(X/S)Bsd variants with pCI-VSV-G, a VSV-G expression vector.

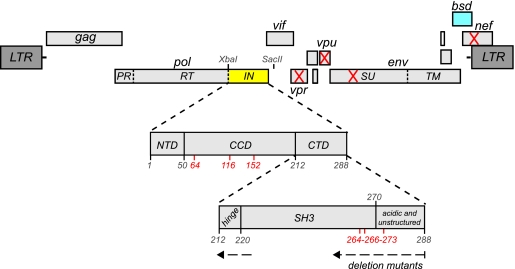

Fig. 1.

Context of the IN CTD within the HIV-1 genome. The genetic organization of HIV-1 is shown, with open reading frames of the nine viral genes presented as light gray boxes. The HXB2-derived parental clone R7/3 (X/S) contains engineered XbaI and SacII sites flanking the IN region. The single-step viruses were made in a vpr− vpu− env− nef− background, with the blasticidin S deaminase cassette (bsd) (blue) in the nef position. The C-terminal end of the Pol protein (yellow box) containing IN is expanded to reveal its three domains, with the IN CTD further magnified to highlight the organization of main structural elements and the span of the IN truncation panel. Amino acid residues of note are shown in red, i.e., the catalytic triad in the CCD (D64, D116, and E152) and the cluster of lysines in the CTD acetylated by p300 (K264, K266, and K273).

Tissue culture and viral stock preparation.

HEK293T, GHOST(3)X4/R5 (60), and HeLaP4R5 (11) cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 100 U/ml penicillin–100 μg/ml streptomycin (P/S); CEM cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and P/S. Viral stocks were generated in one of two ways. For multicycle, replication-competent (env+) virus, stocks were made by mixing 2 μg of proviral plasmid DNA with 12 μg polyethylenimine (PEI) and adding the mixture to a subconfluent monolayer of HEK293T cells cultured in a six-well plate format. Single-step viruses were made by mixing 1.5 μg viral plasmid DNA and 0.5 μg of the pCI-VSV-G expression vector with 12 μg PEI and adding this to HEK293T cells. For both methods, the medium was changed the following day and the viral stocks harvested at 48 h postinfection (hpi) by filtration of cell-free medium through a 0.45-μm nylon filter. The viral titer was determined using data provided by p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences).

Western blot analyses. (i) Intracellular protein.

Transfected HEK293T cells were disrupted by lysis in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) supplemented with “cOmplete” protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 20,817 × g for 15 min at 4°C.

(ii) Virion protein.

Viral stocks, generated by proviral DNA transfection of HEK293T cells, were normalized for p24 content (250 ng) and pelleted through a 25% sucrose cushion at 20,817 × g for 3 h at 4°C, and the pelleted virions were lysed in protease inhibitor cocktail-supplemented RIPA buffer. Samples were normalized for protein content (5), and 25 μg protein (intracellular) or 15 μg protein (virion) was loaded onto 4 to 12% polyacrylamide NuPage Bis-Tris gels (Novex) and, using reducing conditions, resolved by electrophoresis in MOPS (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) buffer. Proteins were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), which was subsequently blocked, washed, and incubated with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against the amino terminus of IN (6G5) (65), capsid (CA) (183-H12-5C) (14), or RT (11B7 and 33D5) (67). Blots were then incubated with rabbit anti-mouse MAb-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and detected using the Immobilon chemiluminescent AP substrate detection kit (Millipore).

Qualitative assay for viral replication competency.

Detection of syncytium formation in the highly fusogenic CEM cell line after infection is indicative of successful proviral DNA integration and efficient env gene expression; the rate and extent of syncytium recruitment and expansion over time constitute a qualitative measure of viral replication competency or fitness over several cycles of growth. Wild-type or mutant virus stocks were normalized for equal p24 content and used to infect CEM cells (103) with viral inocula of 5 ng p24 antigen in 200 μl of medium in 96-well round-bottom plate format, or cells were mock infected with medium alone. All infections were performed in duplicate. The cells were microscopically monitored daily for syncytium formation over the span of a 10- to 12-day observational period. At 7 days postinfection (dpi), the cultures were split 1:40 and again examined daily for an additional 7 days.

Genetic integration assay (bsd transduction).

HeLaP4R5 cells were seeded to approximately 30% confluence (24-well plate format) and inoculated overnight with a normalized amount of single-cycle viral stock (5 ng p24). Twenty-four hours later, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fed with fresh DMEM for an additional 24-h growth period, after which the cells were split into selection medium containing 5 μg/ml blasticidin S. Selection was imposed for an additional 14 days, and then resistant colonies were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and scored macroscopically for the number of resistant colonies.

qPCR analyses. (i) Late RT and 2-LTR circles.

Viral stocks were pretreated with Turbo DNase (Ambion) at a concentration of 40 U/ml at 37°C for 1 h before confluent GHOST(3)X4/R5 cells were infected with 50 ng p24 per well in a 24-well plate format in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene. Infected cells were spinoculated for 2 h at 15°C and 2,400 rpm (1,160 × g), allowing viral adsorption but at a temperature that prevents virus-host membrane fusion. The cultures were then shifted to 37°C within a humidified incubator for 8 h. Total cellular DNA was then prepared for late RT product determinations, or identical paired infected cell cultures were incubated for another 16 h (24 hpi) before total DNA was harvested for quantification of the amount of accumulated 2-LTR circular DNA. The QIAamp DNA blood minikit (Qiagen) was used for all isolations, and the extents of late RT and 2-LTR circle formation were determined by molecular beacon-mediated quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis using primers specific for each type of amplification (for late RT, forward primer 5′-AGATCCCTCAGACCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGG-3′ with reverse primer 5′-GCCGCCCCTCGCCTCTTG-3′ and beacon 5′-56-FAM-ccgacccTCTCGACGCAGGACTCGGCTTgggtcgg-3DAB-3′; for 2-LTR circles, forward primer 5′-CTCAGACCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCTA-3′ with reverse primer 5′-TGACCCCTGGCCCTGGTGTGTAG-3′ and beacon 5′-56-FAM-ccgcacCTACCACACACAAGGCTACTTCgtgcgg-3DAB-3′; lowercase letters represent those complementary base pairs that form a double-stranded “stem” for each molecular beacon).

(ii) Alu PCR integration assay.

Infections and DNA extractions (24 hpi) were performed identically as for 2-LTR quantitative PCR analyses. Using a modification of the twin-PCR amplification protocol designed by Chun et al (16), extracts were normalized for DNA content and then subjected to two rounds of PCR, the first of which uses a forward primer specific to the Alu repetitive element (5′-TCCCAGCTACTCGGGAGGCTGAGG-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-AGGCAAGCTTTATTGAGGCTTAAGC-3′) localized to the U3 region of the HIV-1 LTR. The reaction conditions for the first-round PCR were as follows: 94°C for 3 min and then 22 cycles of 30 s for 94°C, 30 s for 66°C, and a 5-min extension reaction at 72°C, followed by a final 10-min extension at 72°C. A 1/120 fraction of the first-round reaction product was then subjected to a second round of PCR, here modified for beacon-mediated quantitative PCR analysis using a nested set of primers (5′-GAAGGGCTAATTCACTCCCA-3′ and 5′-CTTGAAGTACTCCGGATGCAG-3′) in the LTR in conjunction with a molecular beacon (5′-56-FAM-ccgcacCTACCACACACAAGGCTACTTCgtgcgg-3DAB-3′). The second-round PCR used the following reaction conditions: 10 min at 94°C and then 50 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 33 s at 63°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Integration standards for qPCR analysis were produced by infecting HeLa P4R5 or GHOST(3)X4/R5 cells at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) with BSD (wild-type IN) virus, subjecting cells to a week-long selection at low density, and extracting total DNA at 8 dpi. DNA from these cells was subjected to the first-round PCR and diluted 40-fold. A dilution series of this 40-fold-diluted first-round PCR product was used as the standard by which the tested viruses were compared for quantification.

(iii) LMqPCR assay for 3′ processing.

A schematic of the procedure for the ligation-mediated (62) quantitative PCR (LMqPCR) assay for 3′ processing is shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Infections and DNA extractions (8 hpi) were carried out under conditions identical to those used for PCR analyses of late RT. Here, extracts were normalized for DNA content and then incubated for 12 to 16 h at 16°C in a 15-μl reaction mixture containing 500 to 750 ng total viral/cellular DNA and an equimolar amount of two oligonucleotide primers (each at a 2 μM final concentration), LMqPCR-shortGT (5′-OH-GTACTCATGTA-OH-3′) and LMqPCR-long (5′-OH-GTCTAGAGCTCAGCTGTACATGAGT-OH-3′). LMqPCR-shortGT (11 base pairs) is complementary to LMqPCR-long over nine contiguous nucleotides (LMqPCR-shortGT nucleotides 3 to 11) such that when annealed, the double-stranded oligonucleotide produces a 2-base-pair 5′ overhang (nucleotides G1 and T2), the exact complement to the two base pairs left unpaired after integrase-mediated 3′ processing at each end of proviral DNA (5′-AC-3′), with the rest of LMqPCR-long remaining single stranded and used to anchor a subsequent quantitative PCR assay. Upon ligation, the single phosphate group at each of the 5′ ends of linear proviral DNA is covalently linked to the 3′ end of the LMqPCR-long primer DNA. Ligation reactions were performed with 10 U of Escherichia coli ligase (Takara) in 1× E. coli DNA ligase buffer (New England BioLabs). Since both LMqPCR-shortGT and LMqPCR-long are unphosphorylated, the oligonucleotide pair is relatively inert with respect to promiscuous ligation events, being incapable of individual oligomerization or formation of multiple concatemers upon the ends of the proviral DNA. After ligation, the reaction mixture was incubated at 65°C for 20 min to inactivate the enzymatic activity of the ligase, and then one-third of the ligation reaction product (5 μl) was supplemented with the LMqPCR-long primer and subjected to qPCR analysis. The ligated DNA products were quantified using beacon-mediated qPCR analysis with LMPCR-long and an HIV-1 LTR primer/beacon oligonucleotide set specific for monitoring the efficiency of 3′ processing events at either the 5′ or 3′ LTR (5′ LTR primer/beacon pair, 5′-CTTGCTCAACTGGTACTAGCTTGTAG-3′ used in conjunction with 5′-56-FAM-ccgcacCTACCACACACAAGGCTACTTCgtgcgg-3DAB-3′; 3′ LTR primer/beacon pair, 5′-GGGAGCTCTCTGGCTAACTAGG-3′ used with 5′-56-FAM-ccgaaccaGTAGTGTGTGCCCGTCTGTTGTGtggttcgg-3DAB-3′). Controls for all quantitative PCRs described above included IN D116A virus (with no IN enzymatic activity) and an RT mutant virus (D185A/D186A) (70) with no polymerization activity; the latter is a control for bacterial contaminant DNA left over from the preparation of viral stocks. An additional ligation specificity control was included for LMqPCR analyses. Here, an oligonucleotide (LMqPCR-shortTG, 5′-OH-TGACTCATGTA-OH-3′) complementary to LMqPCR-long and identical to LMqPCR-shortGT except for the first two nucleotides, where G1 and T2 have been reversed (T1 and G2), was used. As a result of this modification, LMqPCR-shortTG is mismatched with the unpaired 5′-AC-3′ dinucleotide left after integrase-mediated 3′ processing, and the LMqPCR-long/LMqPCR-shortTG oligonucleotide pair is unable to be efficiently ligated during the first step of the procedure.

RESULTS

Replication competencies of IN-truncated viruses.

Microscopic examination of syncytium formation is a convenient way to monitor the extent of viral replication through cell culture in vitro, as both viral integration and proviral gene expression of the viral envelope glycoprotein (gp120) are required for syncytium appearance. Using this assay, our panel of C-terminal IN (Gag-Pol) truncation mutants was initially tested to determine which were capable of sustained viral replication in the susceptible host human T cell line CEM-SS. This particular CEM strain is Vif permissive (66) and was chosen for the initial characterization of the deletion mutants since a portion of the IN coding frame overlaps with the 5′ end of the vif gene (integrase codons 271 to 288) (Fig. 1). Therefore, any possible influence that the associated mutagenesis of the Vif protein might have among the panel of IN mutants was removed from consideration and made irrelevant to the interpretation of the results obtained. Qualitatively, the rate of syncytium formation appears to be in positive correlation with increasing length of IN. The wild-type virus (288 amino acids) produced detectable syncytia within 3 days and resulted in cell death of the entire culture within 7 days (Table 1 ). Intriguingly, although sustained viral replication competency is lost after removal of the terminal 16, 17, and 18 amino acids of the protein (i.e., mutants IN 272, 271, and 270), it is partially regained with IN 269 but is lost again for all further truncations N terminal to this position. The same results were obtained across a wide range of multiplicities of infection (data not shown).

Table 1.

Phenotypic classification of a nested set of IN carboxyl-terminal single-amino-acid truncation mutants based on a comparison of sustained replication, integration frequency, 3′ processing efficiency, and accumulation of viral DNA species for the wild-type and mutant viruses

| IN | Sustained replicationa | %b |

Phenotypic classd | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration frequency determined by: |

3′ processingc | Late RT | 2-LTR | 2-LTR/RT | ||||

| BSD | Alu PCR | |||||||

| ΔIN | − | 0 | ND | ND | 7 | 19 | 271 | II |

| IN 212 | − | 0 | ND | ND | 12 | 16 | 133 | II |

| IN 260 | − | 0 | ND | ND | 9 | 19 | 211 | II |

| IN 265 | − | 0 | ND | ND | 22 | 37 | 168 | II |

| IN 266 | − | 0 | ND | ND | 9 | 29 | 322 | II |

| IN 267 | − | 0 | <1 | 1 | 10 | 31 | 310 | II |

| IN 268 | − | 0 | <1 | 0 | 26 | 36 | 138 | II |

| IN 269 | + | 11 | 13 | 12 | 325 | 1,324 | 407 | RC |

| IN 270 | − | 1 | 3 | 1 | 116 | 1,274 | 1,098 | I |

| IN 271 | − | 1 | 5 | 2 | 332 | 886 | 267 | I |

| IN 272 | − | 2 | 6 | 3 | 203 | 1,138 | 561 | I |

| IN 273 | + | 14 | 27 | 17 | 231 | 789 | 342 | RC |

| IN 274 | + | 39 | 34 | 49 | 223 | 474 | 213 | RC |

| IN 275 | + | 30 | 36 | 72 | 178 | 522 | 293 | RC |

| IN 276 | + | 36 | 39 | 37 | 138 | 371 | 269 | RC |

| IN 277 | + | 57 | 45 | 83 | 176 | 432 | 245 | RC |

| IN 282 | + | 79 | 111 | 106 | 90 | 124 | 138 | RC |

| Wild type | + | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | RC |

| IN D116A | − | 0 | 2 | 1 | 248 | 3,649 | 1471 | I |

| RT− | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Wild type (GT) | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| Wild type (TG) | 0.1 | 100 | ||||||

CEM-SS cells were monitored daily for the formation of multinucleated syncytia in culture and passaged accordingly. +, syncytia detected at 4 to 5 days postinfection; −, no syncytia detected after 14 days of culture.

Percentage relative to values obtained for the wild-type IN virus, which were set at 100. ND, not determined. Results are typical of at least two independent experiments.

Relative values for 3′ processing at the U3 (5′-LTR) terminus are presented. Similar results were obtained for the U5 (3′-LTR) viral DNA end (data not shown). Processed DNA species were quantified using the LMqPCR protocol (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and results are presented for each mutant as a percentage of wild-type levels. The results for wild type (GT) and wild type (TG) are those obtained from a ligation specificity control for the 3′ processing LMqPCR analyses. Here, an oligonucleotide (LMqPCR-shortTG) complementary to LMqPCR-long and identical to LMqPCR-shortGT except for the first two nucleotides, where G1 and T2 have been reversed (TG), was used. As a result of this modification, LMqPCR-shortTG is mismatched with the unpaired 5′-AC-3′ dinucleotide left after integrase-mediated 3′ processing, with the oligonucleotide pair being unable to be efficiently ligated during the first step of the procedure.

RC, replication-competent; NA, not applicable.

Integration frequencies of IN-truncated viruses.

It has been established by previous research that successful ongoing viral replication in culture is contingent on an integration rate of at least 10 to 15% of that of the wild-type virus (78). In order to determine whether changes in integration rate were responsible for the pattern of replication competency observed in the syncytium formation assay, we next assessed the integrative capacities of our truncated IN mutants. Rates of integration for each mutant virus were measured in two distinct but corroborating assays, one genetic and one biochemical. First, in the BSD assay, we examined the ability of the viruses to stably transduce a susceptible cell line with a dominant selectable marker for blasticidin resistance (bsd). In order to specifically gauge integration and not viral replication dynamics, we limited infection to a single round by pseudotyping HIV-1 env− bsd+ viruses with the pan-tropic vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein (VSV-G). We included as an integration negative control the IN D116A catalytic mutant. This is a well-characterized class I mutant with virtually no capacity for integration (78) but retaining the ability to efficiently perform other IN-mediated or -facilitated processes. For each virus, blasticidin-resistant colonies, each one of which is indicative of a successful integration event, were scored and, for each virus, expressed as a percentage of the wild-type integration frequency (Table 1). The second method used to measure integration frequency is an adaptation of the Alu PCR integration assay described by Chun et al (16). This technique, in contrast to the BSD assay, is not contingent upon proviral gene expression and therefore permits direct quantification of integrated viral DNA. The results of this assay, listed in Table 1, unmistakably substantiate those of the genetic transduction assay. Taken together, these data establish a positive correlation between IN length and integration frequency, with the exception of those mutants (IN 260, IN 265 to 268, and IN 270 to 272) that failed to replicate in CEM cells. The replication-negative status of the latter mutants is likely due to a reduced integration frequency which is below the minimum boundary necessary for sustained replication in CEM cell culture.

Categorization of nonreplicating IN truncations into class I and II phenotypes.

Some IN mutations can potentially disrupt steps of the viral life cycle apart from the catalytic steps required for integration. Therefore, the absent or low transduction efficiencies of a subset of IN truncation mutant viruses (IN 260, IN 265 to 268, and IN 270 to 272) prompted further investigation to determine the nature of these IN-mediated defects. As mentioned above, replication-defective viruses with deficits specific to the process of integration often possess normal amounts of reverse-transcribed viral DNA. However, without the potential for host genome integration, these free viral DNA species are imported to the nucleus and subsequently self-ligated to form 2-LTR circles. To examine which stages of the viral life cycle were affected, we aimed to investigate the stages of viral replication prior to integration. Initially, we evaluated the efficiency of reverse transcription and then determined of the extent of 2-LTR circle formation, a surrogate marker for viral DNA nuclear import. DNA was extracted from GHOST cells at 8 and 24 hpi, corresponding to the peaks of late RT and 2-LTR product accumulation, respectively. The individual DNA species were then quantified by beacon-assisted qPCR analysis (Table 1). Additionally, to remove any possible influence that differential or aberrant catalytic activity might have on reverse transcription and/or other downstream viral DNA product formation, viruses were engineered in which each truncation mutation was recombined with D116A, a prototypic class I mutation. Using this scheme, each member of the mutant set could be evaluated for reverse transcription and viral DNA import without regard to its catalytic potential (Table 2). Both assays were in general agreement, and the results were used to classify the replication-defective IN truncation mutants as either class I or class II mutants based on their relative levels of synthesized late RT and 2-LTR circle product formation, growth potential through CEM-SS cells, and integration frequency compared to these same parameters for the wild-type and IN D116A derivative viral infections (Tables 1 and 2). IN mutants truncated past IN 269 (IN 260 and IN 265 to 268) were classified as class II mutants due to their inability to produce significant levels of reverse-transcribed DNA. In contrast, replication-defective IN 270, 271, and 272 viruses generated near-wild-type levels of late RT product with significantly elevated levels of 2-LTR circles, though, notably, not to the extent produced by the catalytically inactive IN D116A virus. Thus, these viruses were classified as class I IN mutants, as they efficiently progress through the viral life cycle, successfully accomplishing IN-mediated secondary activities, but are defective in one or both steps of catalysis as evidenced by the severe attenuation of provirus formation.

Table 2.

Evaluation of reverse transcription and viral DNA import in a subset of IN carboxyl-terminal truncation mutants without regard to catalytic potentiala

| IN | %b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Late RT | 2-LTR | 2-LTR/late RT | |

| IN D116A 268 | 7 | 1 | 14 |

| IN D116A 269 | 88 | 42 | 48 |

| IN D116A 270 | 67 | 27 | 40 |

| IN D116A 271 | 64 | 20 | 31 |

| IN D116A 272 | 59 | 22 | 37 |

| IN D116A 273 | 61 | 23 | 38 |

| IN D116A 274 | 76 | 35 | 46 |

| IN D116A 275 | 77 | 37 | 48 |

| IN D116A 276 | 85 | 40 | 47 |

| IN D116A 277 | 89 | 54 | 61 |

| IN D116A 282 | 131 | 106 | 81 |

| IN D116A | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| IN D116A ΔH | <0.1 | <0.002 | |

Viruses in which each truncation mutation was recombined with D116A, a prototypic class I mutation, were engineered in an effort to remove any possible influence that differential or aberrant catalytic activity might have on reverse transcription and/or other downstream viral DNA product formation. Instructively, when examined for these parameters, the results obtained for the mutants are in general agreement even in the absence of IN catalytic function (compare Tables 1 and 2). These results corroborate the classification of the replication-defective IN truncation mutants as either class I or class II (Table 1) and provide further evidence that these truncations differentially affect reverse transcription of viral DNA and/or its subsequent nuclear import.

Percentage relative to values obtained for IN D116A, which were set at 100.

3′ processing of class I mutants.

Though IN 270, 271, and 272 were classified as class I mutants with elevated levels of 2-LTR circles compared to the wild type (yet significantly lower than that for the paradigmatic IN D116A mutation), the level of viral extrachromosomal DNA in this subset was not appreciably different from that in the flanking, partially replication-competent viruses IN 269 and IN 273 (Table 1). This led us to question the fate of IN 270 to 272 viral DNAs, as they are reverse transcribed at wild-type levels. For example, what is the explanation for the efficient synthesis of viral DNAs without concomitant accumulation of the very high levels of 2-LTR circles seen in a true catalytic mutant (i.e., D116A)? These observations might be accounted for by a delay in the nuclear import of mutant viral DNA, or alternatively, these particular mutants might be capable of 3′ processing of the viral DNA ends but blocked at the subsequent catalytic step of strand transfer. In the latter scenario, creation of non-blunt-ended linear substrates by active 3′ processing would ostensibly produce DNA substrates less readily converted into 2-LTR circles. On the other hand, defective 3′ processing in mutants lacking all catalytic functions (i.e., IN D116A) would produce blunt-ended viral DNAs that would be expected to be preferential substrates for nuclear ligases.

To help distinguish between the above possibilities, we developed a kinetic, ligation-mediated quantitative PCR assay (LMqPCR) capable of providing precise measurement of the number of processed viral DNA ends in extracts of infected cells. This assay utilizes the unpaired 5′-AC-3′ dinucleotide product left at the ends of reacted viral DNA as a surrogate marker for successful 3′ processing and has the ability to monitor the extent of the reaction at either the U3 or U5 terminus independently (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As a control for the catalytic specificity of this assay, we compared IN D116A with the wild-type virus under identical experimental conditions. In accord with established in vitro data and as expected, IN D116A exhibits robust reverse transcription yet does not process either LTR terminus (Table 1). The addition of a potent strand transfer inhibitor (MK-0518; 50% inhibitory concentration [IC50], 10 nM) to 1 μM did not inhibit the 3′ processing reaction for the wild-type virus, indicating that the assay can differentiate between the two IN-mediated catalytic activities (data not shown). Finally, further evidence for the precision of the assay was provided by replacement of the normal 11-oligonucleotide primer LMqPCR-shortGT (GT) with LMqPCR-shortTG (TG); the latter is an identical primer except for the reversal of the first two 5′ bases, which are in mismatch with the unpaired 5′-AC-3′ overhang left after 3′ processing and incapable of DNA ligation due to noncomplementarity. Thus, total DNA harvested from wild-type-infected cultures was assayed for the extent of 3′ processing using either the GT or TG oligonucleotide. In this experiment, natural complement pairing with GT resulted in robust signal output, while its replacement with the TG oligonucleotide did not yield a significant signal (Table 1). This indicates that the assay functions to detect only authentic end processing and not other kinds of frayed linear DNA substrates that might exist within preparations of total cellular DNA. Utilizing the LMqPCR methodology, we found that among the panel of IN truncation mutants, the level of 3′ processing per virus closely follows the trend of integration frequency as determined by both genetic and biochemical assay (Table 1). This result reveals a direct relationship between successful integration and 3′ processing activity even for those replication-incompetent mutant viruses (IN 270 to 272) that are capable of robust reverse transcription activity. Importantly, both U3 and U5 LTR termini are processed with nearly the same efficiency in these mutants, a value that mirrors the respective integration activity as measured by transduction of the bsd marker for each mutant (Table 1). Since the strand transfer reaction is contingent on 3′ processing of both ends of the same DNA molecule and given the barely detectable integration activity of IN 270 to 272, 3′ processing is apparently the rate-limiting step for successful integration of the IN 270 to 272 mutant DNAs. Thus, when indexed with wild-type values, the relative efficiencies of 3′ processing are directly proportional to the frequencies of integration for the IN 270 to 272 mutant set. In other words, mutant DNAs that are fully processed are likely competent substrates for IN-mediated strand transfer. Alternatively, if 3′ processing and strand transfer both require formation of the tetrameric intasome in contact with viral DNA, then a plausible explanation for diminished 3′ processing yet efficient strand transfer for those viral DNA ends that have undergone processing may be that the assembly of the intasome is the step that is affected by mutation. Since assembly of the intasome appears to be a prerequisite for both 3′ processing and strand transfer (48), once assembled, both these catalytic steps can proceed normally.

Mapping the defect of class II mutants.

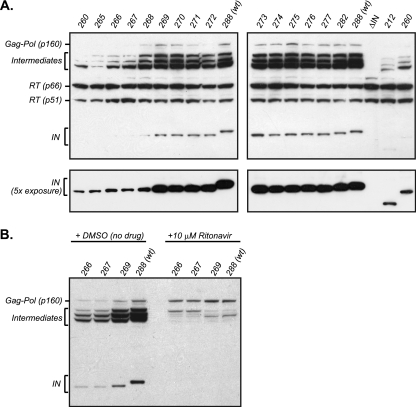

Having identified IN truncations shorter than 269 residues as class II mutants, we then tested these viral mutants to discern the viral process or processes thus affected. Integrase is known to influence the precision of virion assembly and egress from the plasma membrane of producer cells. Perturbation of this process can influence the efficiency by which viral components such as Gag-Pol can be packaged into newly formed virions, thus inducing downstream effects on the processes of reverse transcription and integration during the next cycle of infection. To examine this process, we aimed to ascertain whether defects in either viral polyprotein precursor (Pr55Gag and Pr160Gag-Pol) packaging and/or processing were present. To this end, we used Western blot analysis to first assess the protein content of viral particles produced by the mutant virus panel. We discovered that IN 260 and IN 265 to 267 virions contain diminished levels of both RT and IN (Gag-Pol products) on a per-virion basis, whereas the similarly grouped class II mutant IN 268 possessed wild-type levels of virion-associated RT and IN (Fig. 2). The remaining IN truncations of greater length (IN 269 to IN 282) exhibited the same pattern as the wild-type virus. Previous studies (6) have demonstrated that assembly defects observed within producer cells of some IN mutant viruses can be caused by early activation of the viral protease, thereby resulting in the generation of prematurely processed Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins and/or their derivatives. Thus, we looked for evidence of this phenomenon in the class II mutants by Western blot analysis of the intracellular viral protein content of transfected, virus-producing cells. Intracellular RT blots gave no indication of processing defects, as the p66RT and p51RT species were found at similar levels across the viral panel (Fig. 3 A). We did, however, observe a significant reduction of intracellular IN protein levels in class II mutants (inclusive of IN 268). Probing with anti-IN and anti-RT antibodies allowed the detection of unprocessed Pr160Gag-Pol polyprotein as well as its intermediate products (Fig. 3A and B). Intermediate-size proteolytic products are produced by the action of the viral protease, and their formation is sensitive to the HIV-1 protease inhibitor ritonavir as evidenced by a significant reduction of these metabolites along with a concomitant increase in the level of the unprocessed Pr160Gag-Pol precursor upon treatment (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the pattern of cleavage products is abnormal in the IN 260 and IN 265 to 267 viruses; however, C-terminal truncations extending up to and including IN 268 exhibit a processing pattern commensurate with that of the wild-type virus (Fig. 3A). Previous work has demonstrated that Gag-Pol can be packaged into virions independently of the N-terminal Gag domains, and thus the high levels of partially processed Gag-Pol present in the cytoplasm of IN 268-transfected cells could account for the efficient packaging of RT and IN into these mutant virions (9, 15, 49).

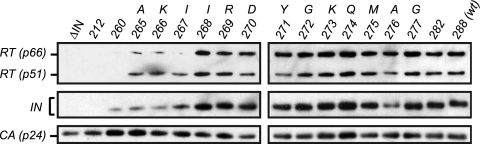

Fig. 2.

Gag-Pol protein compositions of IN-truncated virions. Viral supernatants containing equivalent amounts of p24 antigen were pelleted through a sucrose cushion, lysed, and subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies to RT, IN, and CA. ΔIN has a dual stop codon placed precisely at the end of the RT-coding frame, preventing the expression of IN.

Fig. 3.

Intracellular processing profiles of Gag-Pol products. HEK293T cells were lysed at 48 to 52 h posttransfection with the panel of IN truncation plasmid constructs, and the cleared cell lysate was analyzed by Western blot analysis for the presence of intracellular Pol products RT and IN. (A) Intracellular Pol protein profile of the entire panel of IN truncations, indicating free RT (p66 and p51) and IN (p32) and the Gag-Pol processed intermediates. (B) A subset of IN truncations were transfected in the presence of 10 μM ritonavir to inhibit HIV-1 protease activity or with an equivalent concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as negative control.

Paradoxically, the low intracellular IN levels in the IN 260 and IN 265 to 268 truncation mutants may be explained by premature precursor processing. IN, when cleaved from Gag-Pol, possesses at its N terminus a phenylalanine residue that in conjunction with still-undefined internal signals targets IN for rapid proteasomal degradation via the N-end rule pathway (50, 64; for a review of the N-end rule, see reference 59). To distinguish between this phenomenon and degradation via a more conventional proteasome-mediated misfolded-protein degradation pathway, we tested the steady-state levels of ectopically expressed recombinant Met-initiated IN truncation (not subject to N-end rule degradation) in transient transfections (64, 68). Using a transcriptionally linked system for producing both Met-initiated IN and green fluorescent protein (GFP) for normalization (Met-IN-internal ribosome entry site [IRES]-GFP), we found that with the exceptions of IN 260 and 266, the truncations tested were expressed at levels comparable to that of full-length IN (data not shown). This result is consistent with an interpretation that the low levels of IN 212 to 268 in virus-producing cells are most likely due to N-end rule-specific degradation. Thus, the high intracellular levels of IN observed for IN 269 to 288 (wild type) likely represent fully processed IN that is protected from degradation as it progresses through the virion egress pathway or as a result of its sequestration within the protected environment of fully formed virions still associated with the cell.

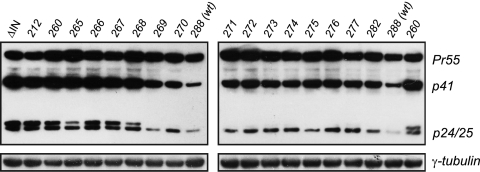

Next, we investigated processing of intracellular Gag using an anti-CA antibody (Fig. 4). This analysis revealed that levels of the Pr55Gag precursor are similar throughout the panel of IN truncations. However, the class II IN truncation mutants (IN 260 and IN 265 to 268) display both a detectable increase in the p41 intermediate species (relative to the class I mutants, IN 270 to 272) and an irregular p24/p25 ratio which mirrors that for a previously documented processing-defective class II mutant (6) possessing a gross deletion of the entire IN region (ΔIN) (Fig. 4). Thus, with the exception of IN 268, for which the only defect found was an irregular p24/p25 ratio, the remaining class II IN truncation mutants appear to be impaired primarily at virion assembly. This is likely due to an abnormality of intracellular polyprotein processing ostensibly caused by dysregulation of viral protease activation.

Fig. 4.

Intracellular p55 Gag processing. HEK293T cells were lysed at 12 h posttransfection with the panel of IN truncation plasmid constructs, and the cleared cell lysate was analyzed by Western blot analysis using an anti-CA monoclonal antibody to detect the intact Gag precursor (p55), its intermediate forms (p41 and p25), and the fully processed p24 CA protein.

D116A complementation of IN truncations.

A possible explanation for the observed phenotypes of the progressively deleted IN CTD mutants is that the enzyme becomes increasingly unstructured and misfolded as it is gradually shortened. This is especially relevant when removing residues past IN 270, the outer margin of the single structural element of the CTD, the SH3-like fold. Indeed, in our panel of mutants, IN 268 and shorter truncations are the only mutants that exhibit multiple defects during viral growth. Does gross protein misfolding cause these defects, or might interruption of a requisite interaction made with a structurally intact IN CTD result in the loss of one or more of its functions? If the latter was the case, then another IN protein possessing an intact CTD could potentially complement those activities in trans. We tested this hypothesis in a reciprocal rescue scheme with the D116A IN mutant, which contains a mutation in the CCD but has an intact and unmutated CTD. Interdomain complementation is possible because assembly of monomeric IN subunits into higher-order multimeric IN complexes is required for interactions between viral DNA and the IN protein. Therefore, defective domains in a single IN monomer may be compensated for by a functional domain in another monomer component of the complex. In principle, the IN truncation mutants possessing a properly folded CCD should be able to complement D116A IN and restore catalytic activity of the multimer. In reciprocal fashion, the D116A IN mutant with an intact and full-length CTD should complement the replication-defective CTD truncation mutants. Hybrid IN viruses made by cotransfection of mutant plasmids were tested for 3′ processing efficiency (relative to their respective late RT values) as well as the frequency of integration. The results (Table 3) demonstrate that although the full subset of class I truncations (IN 270 to 272) are efficiently rescued by IN D116A, the class II mutants cannot be substantially restored by IN D116A, with the exception of IN 268, which behaves more like a class I truncation in these experiments. This result indicates that amino acid residues near the carboxyl-terminal boundary of the SH3 domain functionally define an endpoint beyond which active complementation is lost.

Table 3.

Restoration of 3′ processing and integration in CTD truncation mutants by reciprocal, interdomain complementation with D116Aa

| IN | 3′ processing (%)b |

Integration frequency (%)c |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without complementa- tion | With complementa- tion | Without complementa- tion | With complementa- tion | |

| IN 266 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 2 |

| IN 267 | 1 | 28 | 0 | 11 |

| IN 268 | 1 | 83 | 0 | 60 |

| IN 269 | 17 | 85 | 41 | 51 |

| IN 270 | 1 | 79 | 4 | 37 |

| IN 271 | 2 | 90 | 9 | 59 |

| IN 272 | 4 | 74 | 3 | 41 |

| IN 273 | 16 | 89 | 37 | 49 |

| Wild type | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| IN D116A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Hybrid IN viruses were produced by cotransfection of equivalent amounts of proviral plasmid DNAs of the indicated IN truncation mutant and IN D116A and evaluated for 3′ processing and integration frequency. Results for each mutant infection are presented as their proportion relative to the value for the wild-type viral infections and are representative of duplicate experiments. Although the full subset of class I truncations (IN 270 to 272) are efficiently rescued by IN D116A, the class II mutants cannot be substantially rescued by IN D116A (with the exception of IN 268 [see the text]). These results indicate that amino acid residues near the carboxyl-terminal boundary of the SH3 domain define a functional endpoint beyond which active complementation is lost.

Determined by LMqPCR analysis, with each value normalized to the amount of viral DNA synthesized (late RT product).

Determined by BSD transduction assay.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing a panel of single-amino-acid deletion mutants, we have precisely mapped the minimal number of C-terminal amino acids of Gag-Pol required for sustained replication competency through an immortalized human T cell line. This mapping exercise allowed us to define IN 269 as the necessary and sufficient C-terminal endpoint. Importantly, although mutant IN 269 only just achieves a rate of integration that allows its continued maintenance in culture (11 to 13% of the wild-type level), truncation at residue 269 is a valid, operational endpoint. Indeed, the ability to sustain multiple de novo rounds of replication signifies in itself that this IN length sufficiently accommodates IN functionality not just in integration but also in the ancillary roles of IN during assembly and reverse transcription. Thus, although IN is one of the most conserved proteins of the virus, removal of several amino acids from its carboxyl terminus does not abolish viral replication in various cell lines. In the current study we summarize the data from a variety of assays in order to characterize the nature of defects associated with mutations in this region.

Structural information for the IN CTD abruptly ends at aspartic acid 270. This residue coincides with the carboxyl-terminal endpoint of an interwoven mesh of five interconnected β-sheets spanning 48 amino acids, the IN CTD SH3 motif. A natural concern and possible consequence of sequential removal of residues past the boundary at position 270 and into the structured region outlined above is the potential for disruption of intimate inter-β-sheet interactions that sustain the three-dimensional structure of the SH3 element. Our observations of the mixed phenotypic display of precursor protein processing of the IN 268 truncation (Fig. 3 and 4) and the fact that it is one residue short of IN 269 (required for all enzymatic and ancillary functions of IN) suggests that the isoleucine at position 268 could represent the final “nail” holding together and maintaining the SH3 fold. Indeed, IN truncations past isoleucine 268 (i.e., mutants IN 260 and IN 265 to 267), in terms of the patterns of both intracellular and intravirion proteins (Fig. 2 to 4), resemble to a great extent an IN mutant that is completely devoid of the CTD (IN 212). The structural data show that the isoleucine residue at position 268 is the last residue of the fifth and final β-sheet (residues 265 to 268) of the SH3 fold (13, 22, 23). I268 engages in intimate hydrophobic contact with tyrosine 226 in an adjacent β-sheet, together contributing to the establishment of a bridge of hydrophobic interactions encompassing the three sheets (β1, β2, and β5) across one face of the fold (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Substantial D116A rescue of IN 268, but not of IN 267 (or shorter deletion mutants), provides proof of the productive association and cooperation of the two IN subunits and gives further evidence of correct IN 268 CTD folding that is lost by further truncation of the protein.

Recently, the structure of the prototypic foamy virus (PFV) intasome has been solved, imparting unprecedented insight into the molecular mechanism of retroviral integration (36, 57). Though PFV and HIV-1 are divergent members of the retroviral family lineage, HIV-1 strand transfer inhibitors also inhibit PFV IN (37), suggesting that similar catalytic mechanisms are employed by these INs (13, 36, 45). Thus, with the PFV structure in mind, the structural and mechanical bases for the behavior of HIV-1 IN CTD truncations might be extrapolated. The PFV intasome structures are snapshots of events just prior to, during, and after strand transfer, and they reveal the strand transfer functional unit as an IN tetramer (57). Within this tetramer, only the inner subunits establish contacts required for tetramerization and viral and target DNA binding; the outer subunits, for which only the CCDs were determined (the NTD and CTD remained unresolved), were speculated to provide a supporting function or to engage target nucleosomal DNA or the histone octamer (57). The CTDs of the inner subunits, and indeed each domain, make multiple DNA and protein-protein contacts and bridge the two halves of the intasome. Severe disruption of the CTD, as we propose for IN 260 and IN 265 to 267, would be expected to affect the assembly of the intasome and hence integration. Indeed, complementation with full-length IN D116A only minimally rescued integration of these mutants (Table 3). In contrast, the IN 268 to 273 truncations were significantly rescued for integration. In these experiments, successful integration by necessity requires the catalytically active truncated IN protomer to be positioned as the inner subunits of the intasome, their foreshortened CTDs facilitating the required interactions for strand transfer. In this context, the truncated “tail-less” CTDs (IN 268 and 269) accommodate over half of the wild-type levels of strand transfer (Table 3), suggesting that at least for strand transfer, the IN tail is nonessential when located to the inner intasomal subunits. Indeed, for the D116A-complemented viruses (IN 268 to 273), we do not observe significantly diminished integration or incremental enhancement of integration frequency with increasing tail length, as observed with the uncomplemented mutants. Unfortunately, the PFV structure does not illuminate any role for the tail during strand transfer, since here too, this element is unresolved. Instead it appears that this last portion of IN may exert its effect(s) in the context of those subunits located on the outside face of the intasome.

Although the PFV structure suggests a minimal role for the outer IN subunits during strand transfer, these subunits and their domains may be critical during 3′ processing. HIV-1 IN forms dimers and tetramers in solution, and it has been demonstrated that 3′ processing is conducted by an IN dimer (30, 34). The crystal structure of a two-domain HIV-1 IN CCD-CTD fragment (12) reveals a Y-shaped dimer formed via a CCD-CCD interface that is also conserved between the CCDs of the inner and outer subunits of the PFV intasome (13, 36, 45, 57). Cross-linking (32, 42) and complementation (25, 73) studies of HIV-1 IN support a model in which the CTD of one subunit (analogous to the unresolved CTD of an outer PFV intasome subunit) binds subterminal viral LTR DNA, stabilizing the viral DNA terminus in the active site of the opposing subunit (the inner PFV intasome subunit) (36, 57). In the complementation studies presented here, it is the intact CTD of the IN D116A protomer that would necessarily assume this purported DNA binding role, positioning the viral end in the active site of the truncated subunit and thus allowing the processing reaction to occur at wild-type levels. While we observe that the tail on the inner intasome subunit does not significantly influence strand transfer, we do observe a direct correlation between tail length and efficiency of 3′ processing (Table 1, IN 273 to 288). This suggests that the tail's function maybe critical exclusively on the outer IN subunit, putatively enhancing the efficiency with which the CTD stabilizes the viral DNA end for processing to occur. Alternatively, we cannot discount that the tail may be involved in the recruitment of a factor that facilitates integration or that it may somehow be involved in promoting the assembly of the tetrameric intasome, in which both processing and strand transfer occur. Some biochemical evidence does suggest that processing might in fact occur in tetrameric assemblies of IN (48).

The addition of a single amino acid at residue 273, an invariant residue subject to acetylation (10, 70) and possibly ubiquitinylation (61), is sufficient to significantly rescue integration activity (Table 1). Though it has been suggested that the K273 residue plays a significant role in IN functionality, including specific DNA binding (19), substitution of alanine (K273A Stop) or arginine (K273R Stop) instead of the natural lysine residue in the truncated protein is nonetheless able to rescue integration capability that is absent in the IN 270 to 272 truncations (data not shown). This result suggests a degree of promiscuity in amino acid identity for the ability of residue 273 to restore catalytic function to the three more proximal truncations. One possibility is that residue 273 acts as a structural scaffold, restricting the ability of residues 270, 271, and 272 to interfere with DNA binding. Further biochemical analysis is required to determine the exact mechanism by which catalytic activity is lost by the further addition to the IN 269 truncation of one to three amino acid residues and then how a further addition of one residue restores activity.

Such analyses of IN truncations have previously been reported, but not with the single-amino-acid resolution conducted here. A recent study aimed to characterize IN CTD truncations (17), but this mutagenic survey was conducted at expanded intervals of three to four residues. Thus, description of the IN 269 mutant was overlooked. In addition, our grouping of IN 270 as a class I mutant is in discord with the class II phenotype previously reported for this particular mutant (17). We do, however, observe and concur that the CTD tail is not critical for viral replication but enhances both primary and secondary IN functions with increasing efficacy concordant with its length. We conclude that the 18-amino-acid tail of IN is not required for ancillary IN activity, as the IN 269 truncation, which is completely devoid of the tail, supports wild-type precursor protein processing (Fig. 3 and 4) and RT activity (Tables 1 and 2). The IN tail can, however, exert an effect on 3′ processing, initially by hindering the reaction at short lengths (IN 270 to 272) and then by enhancing processing efficiency with increasing tail length from IN 273 through 288. Furthermore, the tail appears to be most important during 3′ processing and less so for strand transfer.

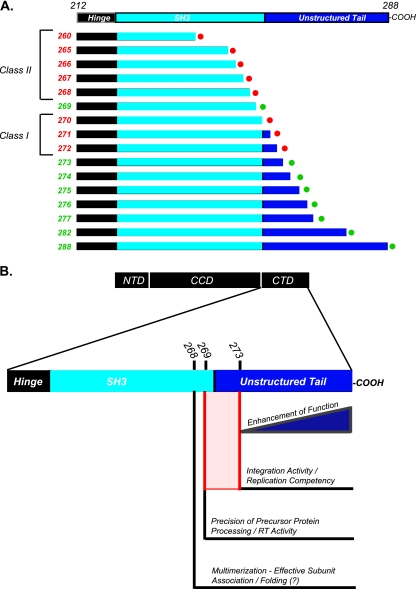

The functional boundaries within the CTD for specific IN activities and contributions to viral dynamics in the context of infection have been identified (Fig. 5) and may be used as a foundation to further characterize IN for both its primary and secondary functions. Studies directed to the IN 268/269 boundary, for instance, may provide insight into the poorly understood mechanisms by which IN prevents premature proteolytic processing of viral precursors in the producer cell. Also, by virtue of its complete lack of the unstructured tail, the enzymatically active IN 269 mutant should be more amenable to structural analyses of IN-DNA interactions. These studies, in conjunction with determination of the specific defects of IN 270 to 272, would illuminate the role of the CTD in integrase catalysis. Such research would help develop a more comprehensive picture of IN and its roles in viral replication and may lead to the development of multipronged therapeutic interventions capable of neutralizing IN activity, not only during the strand transfer step as targeted by the current anti-IN drug repertoire but also in its ancillary, yet significant, roles in other aspects of the viral life cycle.

Fig. 5.

Properties of IN bestowed by increasing CTD length. A summary of the reported findings about the properties of IN at various CTD lengths is shown. (A) Schematic of IN truncation series, with each mutant labeled according to IN phenotypic class (I or II). Replication-defective mutants are labeled with red circles and replication-competent mutants with green circles. (B) Individual properties bestowed by various CTD lengths. IN mutants between IN 269 and IN 273 (red) do not acquire a sufficient amount of integration activity to confer replication competency (IN 270, 271, and 272).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dag Helland for the anti-IN and anti-RT antibodies, Bruce Chesebro and Kathy Wehrly via the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for the anti-CA monoclonal antibody, Merck and Company, Inc., for integrase inhibitor MK-0518, Paul Bieniasz, Magda Konarska, and Charles Rice for helpful scientific advice, and Christopher Plescia for editorial contributions.

The Merck and Company Investigator-Initiated Award Program (grant 36211) (M.A.M.) and the NIH (grants R01 AI065321 and R21 AI062369) (M.A.M.) supported this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 2 March 2011.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Al-Mawsawi L. Q., Al-Safi R. I., Neamati N. 2008. Anti-infectives: clinical progress of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 13:213–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ao Z., et al. 2007. Interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase with cellular nuclear import receptor importin 7 and its impact on viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 282:13456–13467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asante-Appiah E., Seeholzer S. H., Skalka A. M. 1998. Structural determinants of metal-induced conformational changes in HIV-1 integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:35078–35087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asante-Appiah E., Skalka A. M. 1997. A metal-induced conformational change and activation of HIV-1 integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16196–16205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradford M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bukovsky A., Gottlinger H. 1996. Lack of integrase can markedly affect human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle production in the presence of an active viral protease. J. Virol. 70:6820–6825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burke C. J., et al. 1992. Structural implications of spectroscopic characterization of a putative zinc finger peptide from HIV-1 integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 267:9639–9644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai M., et al. 1997. Solution structure of the N-terminal zinc binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:567–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cen S., et al. 2004. Incorporation of Pol into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag virus-like particles occurs independently of the upstream Gag domain in Gag-Pol. J. Virol. 78:1042–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cereseto A., et al. 2005. Acetylation of HIV-1 integrase by p300 regulates viral integration. EMBO J. 24:3070–3081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charneau P., et al. 1994. HIV-1 reverse transcription. A termination step at the center of the genome. J. Mol. Biol. 241:651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen J. C., et al. 2000. Crystal structure of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic core and C-terminal domains: a model for viral DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:8233–8238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cherepanov P. 2010. Integrase illuminated. EMBO Rep. 11:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chesebro B., Wehrly K., Nishio J., Perryman S. 1992. Macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus isolates from different patients exhibit unusual V3 envelope sequence homogeneity in comparison with T-cell-tropic isolates: definition of critical amino acids involved in cell tropism. J. Virol. 66:6547–6554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiu H. C., Yao S. Y., Wang C. T. 2002. Coding sequences upstream of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase domain in Gag-Pol are not essential for incorporation of the Pr160(gag-pol) into virus particles. J. Virol. 76:3221–3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chun T. W., et al. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:13193–13197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dar M. J., et al. 2009. Biochemical and virological analysis of the 18-residue C-terminal tail of HIV-1 integrase. Retrovirology 6:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delelis O., Carayon K., Saib A., Deprez E., Mouscadet J. F. 2008. Integrase and integration: biochemical activities of HIV-1 integrase. Retrovirology 5:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dirac A. M., Kjems J. 2001. Mapping DNA-binding sites of HIV-1 integrase by protein footprinting. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:743–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dobard C. W., Briones M. S., Chow S. A. 2007. Molecular mechanisms by which human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase stimulates the early steps of reverse transcription. J. Virol. 81:10037–10046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drelich M., Wilhelm R., Mous J. 1992. Identification of amino acid residues critical for endonuclease and integration activities of HIV-1 IN protein in vitro. Virology 188:459–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyda F., et al. 1994. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science 266:1981–1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eijkelenboom A. P., et al. 1995. The DNA-binding domain of HIV-1 integrase has an SH3-like fold. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:807–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eijkelenboom A. P., et al. 1999. Refined solution structure of the C-terminal DNA-binding domain of human immunovirus-1 integrase. Proteins 36:556–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a. Engelman A. 1999. In vivo analysis of retroviral integrase structure and function. Adv. Virus Res. 52:411–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Engelman A., Bushman F. D., Craigie R. 1993. Identification of discrete functional domains of HIV-1 integrase and their organization within an active multimeric complex. EMBO J. 12:3269–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Engelman A., Craigie R. 1992. Identification of conserved amino acid residues critical for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase function in vitro. J. Virol. 66:6361–6369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Engelman A., Englund G., Orenstein J. M., Martin M. A., Craigie R. 1995. Multiple effects of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase on viral replication. J. Virol. 69:2729–2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Engelman A., Hickman A. B., Craigie R. 1994. The core and carboxyl-terminal domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 each contribute to nonspecific DNA binding. J. Virol. 68:5911–5917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Esposito D., Craigie R. 1998. Sequence specificity of viral end DNA binding by HIV-1 integrase reveals critical regions for protein-DNA interaction. EMBO J. 17:5832–5843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faure A., et al. 2005. HIV-1 integrase crosslinked oligomers are active in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:977–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fletcher T. M., III, et al. 1997. Complementation of integrase function in HIV-1 virions. EMBO J. 16:5123–5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gao K., Butler S. L., Bushman F. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: arrangement of protein domains in active cDNA complexes. EMBO J. 20:3565–3576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldgur Y., et al. 1998. Three new structures of the core domain of HIV-1 integrase: an active site that binds magnesium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:9150–9154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guiot E., et al. 2006. Relationship between the oligomeric status of HIV-1 integrase on DNA and enzymatic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 281:22707–22719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hamamoto S., Nishitsuji H., Amagasa T., Kannagi M., Masuda T. 2006. Identification of a novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase interactor, Gemin2, that facilitates efficient viral cDNA synthesis in vivo. J. Virol. 80:5670–5677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hare S., Gupta S. S., Valkov E., Engelman A., Cherepanov P. 2010. Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature 464:232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hare S., et al. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of retroviral integrase inhibition and the evolution of viral resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:20057–20062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haugan I. R., Nilsen B. M., Worland S., Olsen L., Helland D. E. 1995. Characterization of the DNA-binding activity of HIV-1 integrase using a filter binding assay. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 217:802–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hazuda D. J., et al. 2000. Inhibitors of strand transfer that prevent integration and inhibit HIV-1 replication in cells. Science 287:646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hehl E. A., Joshi P., Kalpana G. V., Prasad V. R. 2004. Interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and integrase proteins. J. Virol. 78:5056–5067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heuer T. S., Brown P. O. 1997. Mapping features of HIV-1 integrase near selected sites on viral and target DNA molecules in an active enzyme-DNA complex by photo-cross-linking. Biochemistry 36:10655–10665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heuer T. S., Brown P. O. 1998. Photo-cross-linking studies suggest a model for the architecture of an active human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase-DNA complex. Biochemistry 37:6667–6678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jenkins T. M., Engelman A., Ghirlando R., Craigie R. 1996. A soluble active mutant of HIV-1 integrase: involvement of both the core and carboxyl-terminal domains in multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7712–7718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jenkins T. M., Esposito D., Engelman A., Craigie R. 1997. Critical contacts between HIV-1 integrase and viral DNA identified by structure-based analysis and photo-crosslinking. EMBO J. 16:6849–6859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krishnan L., et al. 2010. Structure-based modeling of the functional HIV-1 intasome and its inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15910–15915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kulkosky J., Jones K. S., Katz R. A., Mack J. P., Skalka A. M. 1992. Residues critical for retroviral integrative recombination in a region that is highly conserved among retroviral/retrotransposon integrases and bacterial insertion sequence transposases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2331–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leavitt A. D., Robles G., Alesandro N., Varmus H. E. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutants retain in vitro integrase activity yet fail to integrate viral DNA efficiently during infection. J. Virol. 70:721–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li M., Mizuuchi M., Burke T. R., Jr., Craigie R. 2006. Retroviral DNA integration: reaction pathway and critical intermediates. EMBO J. 25:1295–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liao W. H., et al. 2007. Incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase into virus-like particles. J. Virol. 81:5155–5165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lloyd A. G., Ng Y. S., Muesing M. A., Simon V., Mulder L. C. 2007. Characterization of HIV-1 integrase N-terminal mutant viruses. Virology 360:129–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lodi P. J., et al. 1995. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Biochemistry 34:9826–9833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Low A., et al. 2009. Natural polymorphisms of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and inherent susceptibilities to a panel of integrase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4275–4282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lu R., Ghory H. Z., Engelman A. 2005. Genetic analyses of conserved residues in the carboxyl-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J. Virol. 79:10356–10368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luo K., et al. 2007. Cytidine deaminases APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F interact with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and inhibit proviral DNA formation. J. Virol. 81:7238–7248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lutzke R. A., Plasterk R. H. 1998. Structure-based mutational analysis of the C-terminal DNA-binding domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: critical residues for protein oligomerization and DNA binding. J. Virol. 72:4841–4848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lutzke R. A., Vink C., Plasterk R. H. 1994. Characterization of the minimal DNA-binding domain of the HIV integrase protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4125–4131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Maertens G. N., Hare S., Cherepanov P. 2010. The mechanism of retroviral integration from X-ray structures of its key intermediates. Nature 468:326–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Masuda T., Planelles V., Krogstad P., Chen I. S. 1995. Genetic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and the U3 att site: unusual phenotype of mutants in the zinc finger-like domain. J. Virol. 69:6687–6696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]