Abstract

The mechanism by which viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp) specifically amplify viral genomes is still unclear. In the case of flaviviruses, a model has been proposed that involves the recognition of an RNA element present at the viral 5′ untranslated region, stem-loop A (SLA), that serves as a promoter for NS5 polymerase binding and activity. Here, we investigated requirements for specific promoter-dependent RNA synthesis of the dengue virus NS5 protein. Using mutated purified NS5 recombinant proteins and infectious viral RNAs, we analyzed the requirement of specific amino acids of the RdRp domain on polymerase activity and viral replication. A battery of 19 mutants was designed and analyzed. By measuring polymerase activity using nonspecific poly(rC) templates or specific viral RNA molecules, we identified four mutants with impaired polymerase activity. Viral full-length RNAs carrying these mutations were found to be unable to replicate in cell culture. Interestingly, one recombinant NS5 protein carrying the mutations K456A and K457A located in the F1 motif lacked RNA synthesis dependent on the SLA promoter but displayed high activity using a poly(rC) template. Promoter RNA binding of this NS5 mutant was unaffected while de novo RNA synthesis was abolished. Furthermore, the mutant maintained RNA elongation activity, indicating a role of the F1 region in promoter-dependent initiation. In addition, four NS5 mutants were selected to have polymerase activity in the recombinant protein but delayed or impaired virus replication when introduced into an infectious clone, suggesting a role of these amino acids in other functions of NS5. This work provides new molecular insights on the specific RNA synthesis activity of the dengue virus NS5 polymerase.

INTRODUCTION

Dengue virus (DENV) is the single most significant arthropod-borne virus pathogen in humans. It belongs to the Flaviviridae family together with other important pathogens such as yellow fever virus (YFV), West Nile virus (WNV), Saint Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV). The World Health Organization continues reporting dengue outbreaks every year in the Americas and Asia. In spite of the urgent medical need to control DENV infections, vaccines and antivirals are still unavailable. Although a model for DENV RNA synthesis was previously proposed (17), molecular aspects of the mechanism by which the polymerase specifically amplifies the viral genome are still unclear for DENV and other flaviviruses. To further understand this viral process, we investigated functional properties of the viral polymerase NS5.

NS5 is the largest of the flavivirus proteins (105 kDa); it contains an N-terminal methyltransferase domain (MTase) and a C-terminal RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain. The MTase is responsible for methylation of the cap structure present at the 5′ end of the viral genome. This process involves methylation in two positions, guanine N-7 and ribose 2′-O (12, 13, 28, 38). The RdRp domain has primer independent (de novo) RNA synthesis activity (1, 26). Interaction of NS5 with a promoter element present at the 5′ end of the genome is necessary for specific RNA synthesis (17, 21). This promoter element is known as stem-loop A (SLA) and corresponds to one of the two RNA structures present at the viral 5′ untranslated region (UTR) (for a review, see reference 34). The other element, stem-loop B (SLB), contains a sequence that is complementary to a region present at the 3′ UTR, which is involved in long-range RNA-RNA interactions and cyclization of the viral RNA (3, 4). Previous studies have demonstrated that DENV genome cyclization is necessary for relocating the promoter-NS5 complex, formed at the 5′ end, to the 3′ end initiation site (17).

The crystal structure of the DENV type 3 (DENV3) RdRp has been recently solved (35). Similar to other template-dependent polymerases, the DENV RdRp resembles a right hand containing fingers, palm, and thumb subdomains. In contrast to DNA polymerases, the DENV RdRp contains an encircled active site with extensive interactions between the fingers and thumb subdomains (named fingertips), resulting in a protein that adopts a closed conformation (35). A similar closed conformation was observed for different RdRps such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), bacteriophage φ6, foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), and reovirus (2, 7, 10, 11, 15, 20, 31). The general fold of the DENV RdRp is similar to that of the reported structure of the WNV protein (22, 35). In the thumb subdomain, a priming loop was identified which differentiates primer-independent RdRps (HCV, BVDV, WNV, and DENV) from primer-dependent enzymes (FMDV and rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus [RHDV]) (14). The priming loop is thought to provide the initiation platform stabilizing the de novo initiation complex (7, 10). Furthermore, as shown for other RdRps, the template tunnel in the DENV protein has dimensions that would permit access only to single-stranded RNA, suggesting a conformational change associated to duplex RNA formation during RNA synthesis (35). Based on biochemical and structural studies, a model was proposed in which the DENV RdRp has a closed conformation during initiation, and after a short oligonucleotide is synthesized, a switch to an open conformation occurs, allowing elongation to proceed (1).

DENV RdRp activity was observed using viral RNAs 160 nucleotides long carrying the SLA promoter (17). Longer RNAs were also active as templates; however, this activity was dependent on complementary sequences at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the RNA, indicating that a circular conformation of the template was necessary (17). It has been reported that poly(rC) homopolymers, but not nonviral heteropolymeric RNAs, were active as templates for DENV RdRp activity (17, 29). Nevertheless, it is unclear how specific viral RNA elements facilitate flavivirus RNA synthesis.

In this work, we used recombinant DENV NS5 and genetically modified full-length DENV clones to investigate the requirement of positive-charged amino acids in the RdRp domain for SLA promoter-dependent RNA polymerase activity. A battery of 19 mutations in NS5 was designed, and polymerase activity was evaluated using nonspecific poly(rC) or specific viral RNA templates. Four mutants were found that lacked polymerase activity with both templates. Interestingly, we identified one mutant carrying a 2-amino-acid substitution (K456A and K457A, located in the F1 motif) that lacked RNA synthesis dependent on the SLA while displaying high activity using the poly(rC) template. This mutant was able to elongate a primer but was unable to initiate de novo RNA synthesis using the natural viral RNA. All the inactive NS5 mutants identified retained the ability to interact with the viral RNA with high affinity. In addition, these mutations impaired viral replication when introduced into a DENV2 infectious clone. Our results provide new information about amino acids in the DENV RdRp involved in specific promoter-dependent initiation of RNA synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification.

Nucleotide fragments containing the coding region of full-length NS5 and the RdRp domain were PCR amplified from the infectious clone of DENV2 strain 16681 (GenBank accession number U87411) and cloned into the plasmid pQE-30 at BamHI and HindIII sites, adding a six-histidine tag at the N terminus of the proteins. The proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta(pLacI) overnight at 20°C after induction with 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Lysis of the cells was carried out using a French press in binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 10% glycerol) in the presence of DNase I and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded on a His-Trap nickel Sepharose affinity column (GE Healthcare) and washed twice with binding buffer plus 100 mM imidazole, and the proteins were eluted with binding buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. The proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. The dialyzed protein solution was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 column. Proteins were stored at −20°C in dialysis buffer containing 40% glycerol.

For mutant recombinant proteins, the oligonucleotides used to introduce each mutation are given in Table 1. Overlapping PCRs were performed with the external primers AVG611 (GCGCATGGATCCGGAACTGGCAACATAGGAGAG) and AVG612 (CAGATTAAGCTTGTCGACCTACCACAGAACTCCTGCTT) using the cDNA of the 16681 infectious clone. All mutants were cloned into the plasmid pQE-30 at BamHI and HindIII sites using a method similar to that described for the wild-type (WT) protein and purified following the protocol described above.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used for overlapping PCRs

| Mutant | Mutation(s)a | Oligonucleotide |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Orientationb | Sequence | ||

| M1 | R279 K282 | For | GGGAAAGCCATAGAAGCAATAAAGCAAGAGC |

| Rev | GCTCTTGCTTTATTGCTTCTATTGCTTTCCCAATTATATC | ||

| M2 | K300 | For | ACCAAGACCACCCATACGCCACGTGGGCATAC |

| Rev | GTATGCCCACGTGGCGTATGGGTGGTCTTGGT | ||

| M3 | K311 | For | ATGGTAGCTATGAAACAGCACAGACTGGATCAGCA |

| Rev | TGCTGATCCAGTCTGTGCTGTTTCATAGCTACCAT | ||

| M4 | R325 | For | CAACGGAGTGGTCGCGCTGCTGACAAAACCTTG |

| Rev | CAAGGTTTTGTCAGCAGCGCGACCACTCCGTTG | ||

| M5 | R361 K370 | For | AAAGTGGACACGGCAACCCAAGAACCGAAAGAAGGCACGGCCAAACTAATGAAAA |

| Rev | TTTTCATTAGTTTGGCCGTGCCTTCTTTCGGTTCTTGGGTTGCCGTGTCCACTTT | ||

| M6 | K386 K388 | For | AAAGAATTAGGGGCGAAAGCGACACCCAGGATGTGCACCAGAGAA |

| Rev | TTCTCTGGTGCACATCCTGGGTGTCGCTTTCGCCCCTAATTCTTT | ||

| M7 | R391 R395 | For | GAAGAAAAAGACACCCGCGATGTGCACCGCAGAAGAATTCACAAG |

| Rev | CTTGTGAATTCTTCTGCGGTGCACATCGCGGGTGTCTTTTTCTTC | ||

| M8 | R400 K401 | For | CCAGAGAAGAATTCACAGCAGCCGTGAGAAGCAATGC |

| Rev | GCATTGCTTCTCACGGCTGCTGTGAATTCTTCTCTGG | ||

| M9 | R438 | For | TGGTTGACAAGGAAGCGAATCTCCATCTTGAAGG |

| Rev | CCTTCAAGATGGAGATTCGCTTCCTTGTCAACCA | ||

| M10 | K456 R457 | For | ACATGATGGGAGCAGCTGAGAAGAAGCTAGGGGAATTCGGCAAGGC |

| Rev | GCCTTGCCGAATTCCCCTAGCTTCTTCTCAGCTGCTCCCATCATGT | ||

| M10.1 | K456 | For | ACATGATGGGAGCAAGAGAGAAGAAGCTAGGGGAATTCGGCAAGGC |

| Rev | GCCTTGCCGAATTCCCCTAGCTTCTTCTCTCTTGCTCCCATCATGT | ||

| M10.2 | R457 | For | ACATGATGGGAAAAGCTGAGAAGAAGCTAGGGGAATTCGGCAAGGC |

| Rev | GCCTTGCCGAATTCCCCTAGCTTCTTCTCAGCTTTTCCCATCATGT | ||

| M11 | K456 R457 K459 K460 | For | TACAACATGATGGGAGCAGCTGAGGCAGCACTAGGGGAATTCGGCA |

| Rev | TGCCGAATTCCCCTAGTGCTGCCTCAGCTGCTCCCATCATGTTGTA | ||

| M12 | R481 | For | TGTGGCTTGGAGCAGCCTTCTTAGAGTTTGAAGCCCTAGGAT |

| Rev | ATCCTAGGGCTTCAAACTCTAAGAAGGCTGCTCCAAGCCACA | ||

| M13 | R519 K523 | For | GTTACATTCTAGCAGACGTGAGCGCAAAAGAGGGAGGAGCA |

| Rev | TGCTCCTCCCTCTTTTGCGCTCACGTCTGCTAGAATGTAAC | ||

| M14 | R540 | For | CCGCAGGATGGGATACAGCAATCACACTAGAAGACCTAAAAAATG |

| Rev | CATTTTTTAGGTCTTCTAGTGTGATTGCTGTATCCCATCCTG | ||

| M15 | K561 K562 | For | ATGGAAGGAGAACACGCAGCGCTAGCCGAGGCCATTTTCAAACT |

| Rev | AGTTTGAAAATGGCCTCGGCTAGCGCTGCGTGTTCTCCTTCCAT | ||

| M16 | K575 R578 R581 | For | GTACCAAAACGCGGTGGTGGCTGTGCAAGCACCAACACCAAGA |

| Rev | TCTTGGTGTTGGTGCTTGCACAGCCACCACCGCGTTTTGGTAC | ||

| M17 | R648 R651 | For | GCAAAACTGGTTAGCAGCTGTGGGGGCCGAAAGGTTATC |

| Rev | GATAACCTTTCGGCCCCCACAGCTGCTAACCAGTTTTGC | ||

| M18 | R769 | For | ACTTCCACAGAGCCGACCTCAGGCTGGCGGCAAATGCTAT |

| Rev | ATAGCATTTGCCGCCAGCCTGAGGTCGGCTCTGTGGAAGT | ||

| M19 | K840 R841 | For | AGGAAATCCCATACTTGGGGGCAGCGGAAGACCAATGG |

| Rev | CCATTGGTCTTCCGCTGCCCCCAAGTATGGGATTTCCT | ||

All residues were mutated to alanines.

For, forward; Rev, reverse.

Construction of recombinant dengue viruses.

The mutations were introduced into a DENV type 2 cDNA (19) (GenBank accession number U87411) clone by replacing the StuI-AvrII or AvrII-HpaI fragment of the wild-type plasmid with the fragment obtained by overlapping PCR.

Mobility shift assay.

RNA-protein interactions were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). Uniformly 32P-labeled RNA probes were obtained by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase and purified on 5% polyacrylamide gels and 6 M urea. Purified PCR products were used as templates for the in vitro transcription. A probe corresponding to the first 160 nucleotides of the viral genome (here, 5′ DV) was PCR amplified from the 16681 DENV cDNA with the primers AVG 213 (TAATACGACTCACTATAAG) and AVG 130 (GTTTCTCTCGCGTTTCAGCATATTG). The 5′ DV RNA with a deletion of SLA (5′ DVΔSLA) was amplified using the primers AVG 213 and AVG 130 from a plasmid containing the deletion of the first 70 nucleotides (17). Capped RNAs were transcribed using the PCR products as templates in the presence of an m7GpppA cap analog (New England BioLabs). The binding reaction mixture contained 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 3.8% glycerol, 0.12 mg/ml heparin, 0.1 nM 32P-labeled probe, and increasing concentrations of the protein. For binding competition experiments, increased concentrations of purified 5′ DV or 5′ DVΔSLA RNAs were added to the binding reaction mixture containing 20 nM NS5 and 0.1 nM radiolabeled 5′ DV probe. RNA-NS5 complexes were analyzed by electrophoresis through native 5% polyacrylamide gels supplemented with 5% glycerol. Gels were prerun for 30 min at 4°C at 120 V, and then 20 μl of sample was loaded, and electrophoresis was allowed to proceed for 5 h at constant voltage. Gels were dried and visualized by autoradiography. The macroscopic dissociation constants were estimated by nonlinear regression (Sigma Plot), fitting equation 1:

| (1) |

where Bound % is the percentage of bound RNA, Boundmax is the maximal percentage of RNA competent for binding, [Prot] is the concentration of purified NS5, and Kd is the apparent dissociation constant.

Polymerase activity assay.

The standard in vitro RdRp assay was carried out in a total volume of 25 μl in buffer containing the following: 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0); 10 mM KCl; 5 mM MgCl2; 10 mM dithiothreitol; 4 U of RNase inhibitor; 500 μM (each) ATP, CTP, and UTP; 10 μM [α-32P]GTP; 0.5 μg of template RNA; and 0.2 μg of recombinant purified protein. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min and stopped by the addition of a denaturing solution to final concentrations of 7% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; wt/vol) and 50 mM H3PO4 at 0°C. The TCA-precipitated RNAs were then collected by vacuum filtration using a V-24 apparatus, with the mixture was carefully added onto the center of a Millipore filter (type HAWP; 0.45-μm pore size). The filters were washed eight times (5 ml each time) with cold 7% (wt/vol) TCA–50 mM H3PO4 and dried, and the radioactivity was measured. The polymerase assay on homopolymeric poly(rC) template was carried out in a total volume of 25 μl in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MnCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 4 U of RNase inhibitor, 10 μM [α-32P]GTP, 3 μg of poly(rC) RNA, and 0.2 μg of recombinant purified protein. The detection method was the same as that of the standard RdRp assay. The elongation assay mixture contained 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 4 U of RNase inhibitor, 500 μM CTP and UTP, 10 μM [α-32P]ATP, 50 ng of template RNA (5′-UGUUAUAAUAUUAAUUUAGGUUCU-3′) (IDT), 10 ng of primer (AGAA; Dharmacon), and 0.2 μg of recombinant purified protein, in a total volume of 30 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 60 min. The reaction was ended by phenol extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The RNA products of the polymerase assay were resuspended in Tris-EDTA containing formamide (80%) and heated for 5 min at 65°C. The samples were then analyzed by electrophoresis on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel–6 M urea and visualized by autoradiography.

Periodate treatment and poly(A) polymerase activity.

The periodate treatment was carried out as described previously (37). Briefly, 5′ DV RNA was incubated for 1 h at room temperature in 40 mM NaOAc, pH 5.0, and 20 mM NaIO4. Then, lysine (60 mM) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 3 h at room temperature. The treated RNA was purified using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Inc.) and quantified spectrophotometrically. Its integrity was verified by electrophoresis on agarose gels. The poly(A) polymerase reaction was carried out following the manufacturer's protocol (New England BioLabs).

RNA transfection and immunofluorescence (IF).

To obtain infectious DENV RNAs, in vitro transcription by T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of an m7GpppA cap analog was used as previously described (3). BHK-21 cells were transfected with 3 μg of viral RNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The RNAs were treated with RNase-free DNase I to remove the templates and purified using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Inc.) to eliminate free nucleotides. The products were quantified spectrophotometrically, and the integrity of the RNAs was verified by electrophoresis on agarose gels.

Cells transfected with WT or mutated full-length DENV RNA were used for immunofluorescence assays. BHK-21 cells were grown in 35-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes containing a 1-cm2 coverslip inside. The coverslips were removed and directly used for IF analysis. The transfected cells were trypsinized on day 3, and two-thirds of the total cell population was reseeded onto a 35-mm diameter tissue culture dish containing a coverslip. This procedure was repeated every 3 days until a cytopathic effect was observed. At each time point, a 1:200 dilution of murine hyperimmune ascitic fluid against DENV2 in phosphate-buffered saline–0.2% gelatin was used to detect viral antigens. Cells were fixed in methanol. Alexa Fluor-488 rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugate (Molecular Probes) was used as a detector antibody at a 1:500 dilution. Photomicrographs (magnification of ×200) were acquired with an Olympus BX60 microscope coupled to a CoolSnap-Pro digital camera (Media Cybernetics) and analyzed with Image-Pro Plus software.

Viral RNA extraction and sequencing.

Viral RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) from a 300-μl aliquot of the medium from transfected cells. The RNA was reverse transcribed by Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 42°C using random primers (Promega). In each case, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) products were sequenced using an ABI 377 automated DNA sequencer and BigDye Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

NS5 binding to capped and uncapped RNA molecules.

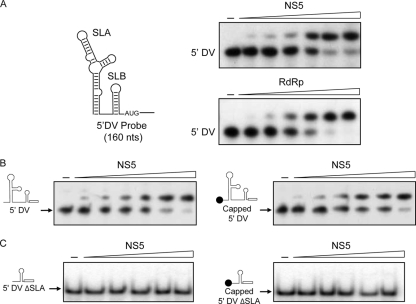

The RdRp domain of NS5 binds specifically to the DENV 5′ UTR (17, 21). In addition, the MTase domain recognizes the cap structure present at the 5′ end of the genome (12, 13). Thus, we hypothesized that NS5 could bind capped 5′ UTR molecules with higher affinity than uncapped RNAs. To investigate this possibility, we expressed the recombinant DENV NS5 and the RdRp domain and performed gel shift assays with radiolabeled RNAs corresponding to the first 160 nucleotides of the viral genome (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Specific binding of NS5 to the 5′ DV RNA. (A) EMSA showing the interaction between the 5′ DV RNA probe (schematically represented on the left) and the full-length NS5 or the RdRp domain. Uniformly 32P-labeled 5′ DV RNA (0.1 nM) was titrated with increasing concentrations of NS5 (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 nM) or the RdRp domain (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 nM). (B) EMSA showing the interaction of NS5 with the pppA-5′ DV RNA (left) or the m7G-pppA-5′ DV RNA (right). (C) EMSA showing the lack of interaction of NS5 with a pppA-5′ DVΔSLA RNA (left) or an m7G-pppA-5′ DVΔSLA RNA (right) carrying deletions of the promoter element SLA.

The 5′ DV RNA was titrated with increasing concentrations of NS5 or RdRp protein. As we previously reported, the RdRp domain bound the RNA with an apparent Kd of 12 ± 4 nM, which was similar to the affinity observed for the full-length NS5 protein (14 ± 3 nM) (Fig. 1A). Then, we analyzed the binding of NS5 to capped and uncapped 5′ DV RNA. Protein binding was similar for both RNAs (Fig. 1B), suggesting that MTase interaction with the cap structure did not contribute significantly to the RNA binding affinity of NS5. It is possible that the contribution of the MTase domain to RNA binding is not detectable due to the high affinity of the RdRp domain to the SLA. To examine this possibility, we deleted the 70-nucleotide SLA and tested the binding of NS5 to the capped and uncapped 5′ DVΔSLA RNA. Under our experimental conditions, no binding of NS5 to the RNA was observed (Fig. 1C). We conclude that binding of NS5 to capped or uncapped RNAs is mainly driven by interaction of the protein with the SLA structure.

Different requirements for NS5 RNA synthesis using specific and nonspecific templates.

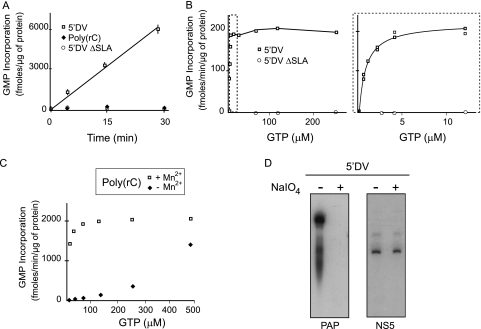

It has been previously shown that flavivirus RdRps use specific viral RNA templates carrying the SLA promoter, but they also use nonspecific poly(rC) templates (17, 29). In order to investigate the requirements for specific and nonspecific activity of the DENV RdRp, we compared RNA synthesis activity under different conditions. The presence of Mg2+ is crucial for catalysis; however, it was previously reported that poly(rC) RNA functions as a template only in the presence of Mg2+ plus Mn2+ (29). Mn2+ usually alters biochemical properties of polymerases, decreasing the stringency of the substrate selection and incorporation fidelity (5). In the presence of Mg2+ and absence of Mn2+, the DENV NS5 showed polymerase activity when the 5′ DV RNA was used as a template while it was almost undetectable when the poly(rC) RNA was used (Fig. 2A). We also analyzed RNA synthesis in the presence of Mg2+ but absence of Mn2+ at different concentrations of GTP using the viral RNA and, as control, a ΔSLA RNA (Fig. 2B). Under these conditions, the 5′ DV-dependent polymerase activity reached a maximum at 12 μM GTP (Fig. 2B). We also compared the RdRp activity using poly(rC) as a template in the presence or absence of Mn2+ and using increasing concentrations of GTP (Fig. 2C). In the presence of Mn2+, we observed high polymerase activity even at low GTP concentrations, while in the absence of Mn2+, polymerase activity was observed only at concentrations of GTP above 200 μM. The results indicate that NS5 requires either Mn2+ or a high GTP concentration for RNA synthesis when the nonspecific poly(rC) is used as a template. Although Mn2+ increases polymerase activity (29), this cation was not a requirement for RNA synthesis using the viral 5′ DV RNA carrying the promoter SLA.

Fig. 2.

In vitro polymerase activity of NS5. (A) In vitro polymerase activity of NS5 using specific (5′ DV RNA), nonspecific [poly(rC)], and negative-control (5′ DVΔSLA) templates in a reaction mixture containing 10 μM GTP in the absence of Mn2+. (B) In vitro polymerase activity of NS5 using viral RNA templates in the absence of manganese and with increasing concentrations of GTP (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 12, 30, 60, 125, and 250 μM) (left). GMP incorporation up to 12 μM GTP is shown in detail (right). (C) Polymerase activity of NS5 using poly(rC) as the template in the presence or absence of manganese and with increasing concentrations of GTP (0, 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, and 500 μM). (D) De novo polymerase activity. Poly(A) polymerase (PAP) activity using 5′ DV RNA and periodate-treated 5′ DV RNA as templates (left). Polymerase activity of NS5 using 5′ DV RNA or periodate-treated 5′DV RNA as templates (right).

It has been previously reported that in vitro RNA synthesis of flavivirus RdRps display two activities, one corresponding to de novo RNA synthesis and the second one consistent with elongation of the template (1, 26, 29, 30). To analyze whether NS5 initiated de novo RNA synthesis using the 5′ DV RNA, we treated the 5′ DV RNA with sodium periodate to block the 3-OH group of the template (37). This treatment avoids elongation of the template mediated by a terminal nucleotidyl transferase activity (32). As a control, the templates, either untreated or treated with sodium periodate, were incubated with a commercial poly(A) polymerase. This enzyme was able to elongate the untreated template efficiently but was inactive with the periodate-treated RNA (Fig. 2D, left panel), indicating that the treatment was efficient. Then, the two RNAs were used as templates for NS5. The RNAs yielded similar products (Fig. 2D, right panel). We conclude that, under our experimental conditions, the DENV NS5 carried out de novo initiation of RNA synthesis using the viral 5′ DV RNA as a template.

Identification of elements in NS5 necessary for SLA-dependent RNA synthesis.

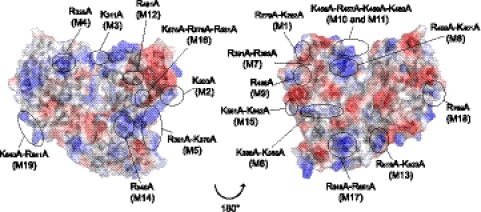

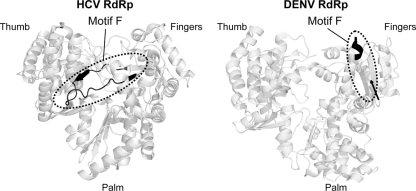

DENV NS5 binds to the SLA RNA, and this interaction promotes RNA synthesis. Specific structures of the SLA that include a top loop and a side stem-loop were found to be necessary for genome replication in infected cells and polymerase activity in vitro (16, 17, 21). Although there is substantial information about RNA elements necessary for SLA promoter function, it is still unknown which domain(s) of NS5 is responsible for promoter-dependent RNA synthesis. In a recent study, it has been proposed that binding of NS5 to the viral RNA is not sufficient for polymerase activity (16). We hypothesized that specific SLA-NS5 contacts could induce conformational changes in the protein that would facilitate initiation of RNA synthesis. To investigate whether there are amino acids in NS5 that would be involved in SLA-dependent activity, a mutational analysis was performed replacing conserved positively charged residues present on the surface of NS5 with alanines. RNA synthesis activity was analyzed in parallel using the 5′ DV RNA or the poly(rC) template. Nineteen substitutions were designed, mainly based on the crystal structure of the DENV3 RdRp (35) (Fig. 3). The mutations were introduced into a bacterial expression vector to produce the recombinant NS5 proteins and into the DENV2 infectious clone to analyze viral phenotypes.

Fig. 3.

Amino acid positions of mutations introduced in the RdRp domain of NS5. A “back” view of the structure of the DENV3 RdRp domain (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession code 2J7U) in surface representation (left) and a “front” view of the structure of the DENV3 RdRp domain rotated 180° (right) are shown. Surfaces are represented with the electrostatic potential in blue for positive charges and in red for negative charges. The figure was drawn using the PyMOL program.

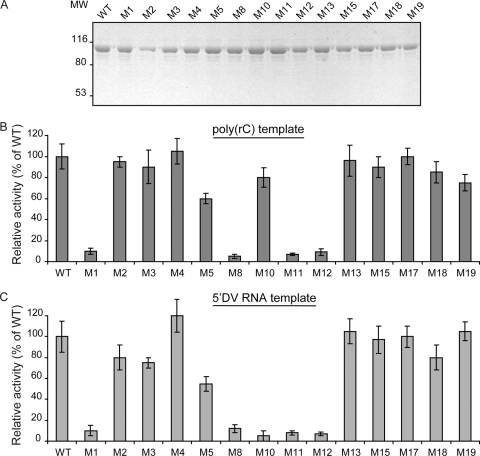

The recombinant proteins were purified using metal affinity and size exclusion chromatography. Five mutants were insoluble (M6, M7, M9, M14, and M16), while the remaining 14 NS5 mutants were soluble and stable (Fig. 4A). Eight NS5 mutants were active with both 5′ DV and the poly(rC) templates (M2, M3, M4, M13, M15, M17, M18, and M19) (Fig. 4B and C). M5 showed about 60% of the WT activity with both templates. In addition, M1, M8, M11, and M12 lacked polymerase activity. Interestingly, M10 including the K456A R457A substitutions displayed selective polymerase activity. This mutant showed almost WT levels of polymerase activity using the poly(rC) template, whereas it was unable to synthesize RNA using the 5′ DV RNA (Fig. 4B and C, compare M10 results). Amino acids K456 and R457 are located in the F1 motif of the F region, which has not been solved in the DENV3 RdRp structure (see Fig. 8) (35). It has been previously proposed that the F1 motif of viral RdRps could be involved in interacting with the RNA template and/or incoming nucleotides (8, 11, 15). This motif has also been defined in different flavivirus RdRps (22, 29). However, its functional role during RNA synthesis remains unknown. The high polymerase activity observed with the poly(rC) RNA indicated that the M10 protein was properly folded, suggesting that K456 and R457 are involved in promoter-dependent RNA synthesis.

Fig. 4.

Polymerase activity of the recombinant NS5 mutant proteins. (A) SDS-PAGE of purified WT and mutant NS5 proteins. MW, molecular weights in thousands. (B) Polymerase activity of mutated NS5 proteins using poly(rC) as a template. (C) Polymerase activity of mutated NS5 proteins using the 5′ DV RNA as a template. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of results from three experiments.

Fig. 8.

Position of the motif F on HCV and DENV RdRps. Structure of HCV (PDB 1NB6) and DENV (PDB 2J7U) RdRps (back view) in ribbon representation. The position of the F motif is indicated in black; for DENV RdRp the region of motifs F1 and F2 is missing in the structural model (from amino acids 454 to 466). The position of amino acid 453 is indicated by an arrow. The figure was drawn using the PyMOL program.

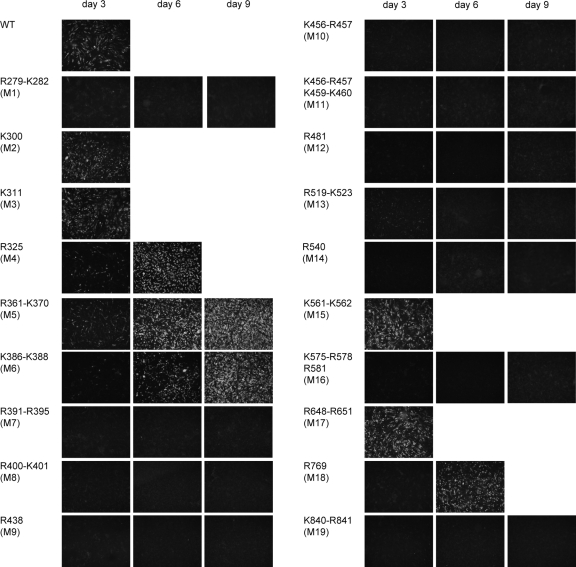

Viral replication of the 19 NS5 mutants was also analyzed in BHK cells by transfecting full-length mutated DENV RNAs. Viral replication was assessed by immunofluorescence as a function of time using specific anti-DENV2 antibodies. Cells transfected with the WT RNA were nearly 100% antigen positive at day 3 and showed cytopathic effect and cell death after day 4. The five NS5 mutants that lacked in vitro polymerase activity with the 5′ DV template (M1, M8, M10, M11, and M12) and four of the five insoluble mutants (M7, M9, M14, and M16) abolished DENV replication (Fig. 5) when they were introduced into the infectious clone. The NS5 M6 mutant that was insoluble when expressed in E. coli resulted in a virus with a delayed replication phenotype when it was introduced into the DENV genome, indicating that the protein was folded and active in mammalian cells. The lower in vitro polymerase activity observed for the mutant M5 correlated well with its slow-replication phenotype (Fig. 5). In addition, four NS5 mutants (M4, M13, M18, and M19) that were fully active in the in vitro assay were delayed or impaired in vivo, indicating that the mutations could affect other important roles of NS5 in infected cells. To investigate whether spontaneous mutations were associated with the replication of mutants with delayed propagation, viruses M4, M5, M6, and M18 were recovered at 6 and 9 days after transfection, and the purified viral RNA was used for sequencing analysis. The replicating viruses retained the original mutations within NS5 and showed wild-type sequences at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Because M10 was particularly interesting, we also searched for spontaneous mutations that would revert the phenotype by passaging the transfected cells for up to 21 days. To this end, we transfected the RNAs corresponding to the WT, the mutant M10 (K456A R457A), and the individual mutants M10.1 (K456A) and M10.2 (R457A). Viral replication was not detected with the mutated RNAs, and no revertant viruses were rescued (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Dengue viruses carrying the mutations in NS5. IF assays of transfected BHK cells with WT or NS5 mutant full-length RNAs. IF assays were performed at 3, 6, and 9 days after transfection.

Based on our mutational studies, we conclude that amino acids in the F1 motif of NS5 are necessary for SLA-dependent RNA synthesis in vitro and for viral replication in transfected cells.

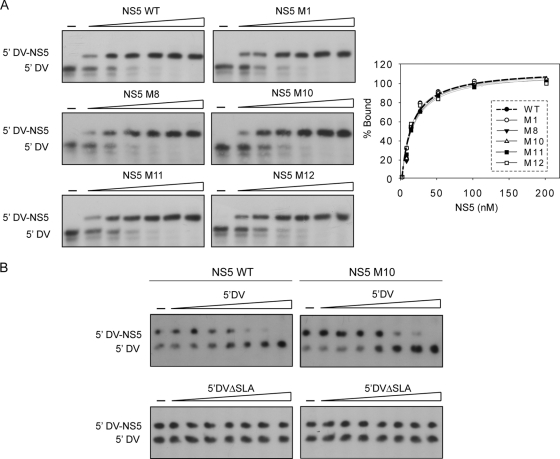

RNA binding and elongation activity of NS5 mutants with impaired RNA synthesis activity.

We further analyzed the defects of the mutants in NS5 that lacked RNA synthesis. The NS5 mutants have substitutions in basic amino acids. Because these residues could be involved in template recognition, we tested the ability of mutants M1, M8, M10, M11, and M12 to bind the viral 5′ DV RNA using gel shift assays. Increasing concentrations of each of the recombinant purified proteins was incubated with the radiolabeled 5′ DV RNA. The estimated dissociation constants were 16 ± 2 nM, 13 ± 4 nM, 14 ± 3 nM, 15 ± 2 nM, and 18 ± 2 nM for the M1, M8, M10, M11, and M12 mutants, respectively. Representative gels of EMSAs and the data fitting are shown in Fig. 6A. The estimated Kd values were similar to the value observed with the WT NS5 protein, indicating that the mutations did not affect binding to the promoter RNA. Because M10 showed a promoter-dependent defect, we further analyzed its binding specificity to the viral RNA in a competitive binding mode. To this end, we incubated a radiolabeled 5′ DV RNA with the amount of WT or M10 NS5 to bind about 50% of the probe and mixed it with increasing concentrations of competitor RNA. Two RNA molecules were used as competitors, the 5′ DV RNA, containing the first 160 nucleotides of the viral genome, and the same molecule with a deletion of the promoter SLA (5′ DVΔSLA). Mobility shift assays showed that the 5′ DV RNA competed in a concentration-dependent manner for binding the WT or the M10 protein (Fig. 6B). The 5′ DVΔSLA RNA did not compete even at 500-fold excess, indicating that the RNP complex formed between the 5′ DV and the WT or the M10 protein was specific (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

(A) EMSA showing the interaction of the 5′ DV RNA with the mutated NS5 recombinant proteins. Uniformly 32P-labeled 5′ DV RNA (0.1 nM) was titrated with increasing concentrations of proteins (0, 6, 12, 25, 50, 100, and 200 nM). Quantification of the percentage of RNA probe bound was plotted as a function of NS5 concentration, and equation 1 was fitted (see Materials and Methods). (B) Competition binding experiment with NS5 WT and NS5 M10 proteins. Uniformly 32P-labeled 5′ DV RNA-WT NS5 or 5′ DV RNA-M10 mutant complex was titrated with increasing concentrations of 5′ DV RNA or 5′ DVΔSLA RNA (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 50 nM), as indicated.

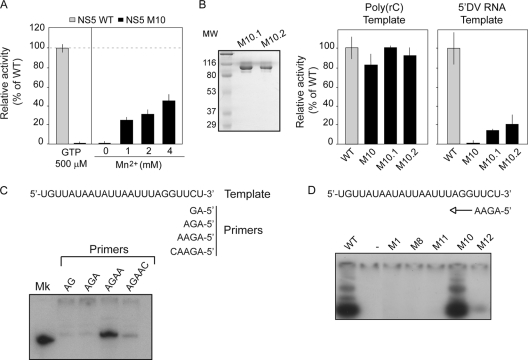

To further characterize the polymerase activity of the M10 mutant, RNA synthesis was measured using the 5′ DV RNA as a template under the optimal conditions observed for the poly(C)-dependent nonspecific activity (Fig. 2C). We determined polymerase activity using increasing GTP or Mn2+ concentrations. The M10 mutant was inactive even at 500 μM GTP (Fig. 7A). In contrast, RNA synthesis was detected in the presence of Mn2+. The highest activity was observed at 4 mM Mn2+, reaching about 40% of the activity observed for the WT protein, suggesting that the phenotype of this enzyme was partially suppressed by Mn2+ (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

(A) Polymerase activity of WT and NS5 M10 using 5′ DV RNA as a template under conditions for nonspecific activity. (B) SDS-PAGE of purified M10.1 and M10.2 NS5 proteins (left). Polymerase activity of NS5 M10 individual mutants using 5′ DV RNA or poly(rC) as a template (right). Error bars indicate the standard deviations of results from three independent experiments. MW, molecular weights in thousands. (C) Elongation activity of NS5 with RNA primers of different lengths. NS5 was incubated with a 24-nucleotide RNA template and the indicated primers. RNA products of the reaction were run in a 20% polyacrylamide gel. A 24-nt RNA mobility marker (MK) is included. (D) Elongation activity of mutated NS5 recombinant proteins. The reaction was carried out using a 4-nucleotide RNA primer (5′-UUCU-3′) and the 24-nucleotide RNA template indicated on the top panel.

The M10 mutant carries two amino acid substitutions (K456A and R457A). To investigate which residue was responsible for the defect in polymerase activity, recombinant NS5 proteins carrying the individual substitutions, mutants M10.1 (K456A) and M10.2 (R457A), were designed, expressed, and purified (Fig. 7B, left panel). The individual mutants conserved full activity using poly(rC) RNA as a template (Fig. 7B, middle panel). In contrast, using the specific 5′ DV RNA, both mutated proteins showed reduced activity (Fig. 7B, right panel), indicating that amino acid substitutions in both positions greatly decrease promoter-dependent polymerase activity.

Previous studies support a model for DENV RdRp RNA synthesis that involves an initiation step, which includes the synthesis of a short oligonucleotide primer, followed by a conformational change necessary for the elongation step (1, 23). Thus, we investigated whether the NS5 M10 mutant was able to elongate a primer. In addition, because mutations M1, M8, M11, and M12 impaired NS5 polymerase activity, they were included in the analysis. To this end, we optimized an elongation activity assay using an RNA template of 24 nucleotides and primers of different lengths (Fig. 7C). Primers of 2, 3, 4, and 5 nucleotides were used. Only the 4-nucleotide-long primer was efficiently used by the DENV NS5 protein for elongation (Fig. 7C). This result is in agreement with a previous observation (26) and indicates that the elongation activity is independent on the promoter element (SLA). Using this assay, the elongation activity of M1, M8, M10, M11, and M12 mutants together with that of the WT protein was evaluated. Interestingly, only M10 was able to elongate the primer, while the other mutants were inactive (Fig. 7D).

These studies indicate that the NS5 mutants are able to bind the 5′ DV RNA. In addition, the M10 NS5 was the only mutant with elongation activity, suggesting that amino acids in the F1 motif of NS5 are involved in a promoter-dependent preelongation step during viral RNA synthesis.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism by which flavivirus RdRps initiate RNA synthesis is still unclear. Although in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated the requirement of the SLA promoter element at the 5′ end of the genome for RNA replication, it is unknown how binding of this RNA structure to the RdRp facilitates the initiation process. It was originally proposed that the promoter would provide specificity by bringing the polymerase to the viral RNA; however, we have recently reported that binding of the SLA to the RdRp is not sufficient for polymerase activity (16). Specific contacts between the SLA and the RdRp were necessary, suggesting a postbinding activation of the polymerase. Here, we found differential cation and GTP concentration requirements when the DENV RdRp used a homopolymeric molecule or the viral RNA as a template (Fig. 2). Previous studies with the HCV RdRp revealed a specific GTP-binding site in a shallow pocket at the molecular surface of the enzyme at the interface between fingers and thumb. The position of this site suggested a possible role of GTP either in triggering a conformational change or in stabilizing an active conformation for efficient initiation (7). We found that high GTP concentration or Mn2+ was necessary for DENV NS5 RNA synthesis using poly(rC) but not with the viral RNA carrying the SLA element (Fig. 2). Previous studies showed that DENV RdRp required a 500 μM GTP concentration for de novo initiation but not for the elongation step (26). In our studies, we were able to detect initiation of RNA synthesis at 12 μM GTP concentration with the 5′ DV RNA (Fig. 2B and D).

A mutational analysis of the RdRp domain of DENV2 NS5, in which basic residues on the surface of the protein were replaced with alanines, identified NS5 mutants with high RNA synthesis activity in vitro but delayed or impaired replication in vivo (Fig. 4 and 5, M4, M13, M18, and M19). M4 included the substitution of R325, which comprises part of the α2 helix, a region that connects the fingers with the thumb subdomain. This region is part of a nuclear localization signal (NLS) of NS5, which could be affected by the mutation (9, 18, 27). M13 contains two amino acid changes (R519 and K523) which are located in the α12 helix present in the palm domain, while M18 and M19 include substitutions in the α23 and α26, respectively, for which roles in NS5 function have not been previously investigated. It is likely that these amino acid changes in NS5 that result in active enzymes in the in vitro assay alter other protein functions in the infected cell. It has been reported that during DENV infection NS5 interacts with host and viral proteins. It has been demonstrated that NS5 interferes with the innate antiviral cell response by binding and inducing STAT2 degradation (6, 24). In addition, NS5 interacts with the viral NS3 protein. NS3 has RNA helicase activity, which could modulate RNA synthesis in the replication complex. Also, in vitro studies reported that NS5 stimulates the nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) and RNA triphosphatase activities of NS3 (36). More information about the specific regions of NS5 involved in protein-protein interactions during viral replication is necessary to better understand the structural requirements of NS5.

The mutant M5 showed both delayed viral replication and reduced polymerase activity in vitro. Therefore, the slow-replication phenotype observed (Fig. 5) can be explained by a defect in the enzymatic function of the protein. However, because the mutated amino acids 361 and 370 are located in the loop connecting α5 and α6 included in the NLS region, they may also cause a defect in NS5 localization (35). Five NS5 mutants were found to lack polymerase activity in vitro and impair viral replication in transfected cells (Fig. 4 and 5, M1, M8, M10, M11, and M12). These mutants bound the viral RNA with high affinity (Fig. 6A). The lack of polymerase activity observed with M1 is in agreement with a previous report with WNV NS5, which demonstrated an important role of the region encompassing amino acids 273 to 316 for RdRp activity. Structural analysis indicated that these amino acids were involved in maintaining the integrity of a three-stranded β-sheet of the fingers domain (35). M8 contains the substitutions R400A and K401A, which are amino acids located in the α7 connecting helix between the fingers and thumb domains that could have a structural function. Importantly, mutant M10, which included the K456A R457A substitutions in the F1 motif, displayed altered promoter-dependent RNA synthesis. Amino acids 454 to 466 were not observed in the electron density map and were not included in the reported model of the DENV3 RdRp structure (35). Interestingly, the ordered part of the F region observed in the structure in DENV and WNV runs perpendicular to that observed for the F region of other related RdRps such as those of HCV and BVDV (22, 35) (Fig. 8). If we assume that this region plays a similar role in these polymerases, a conformational change would be necessary to create the proposed nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) or a template-binding site in the DENV RdRp (for a review, see reference 23).

It has been proposed that viral RdRps adopt a catalytically inactive form, which can be transformed to a catalytically competent state by binding primers, templates, divalent metal ions, and/or nucleotide triphosphates (25). Thus, two conformational changes in the protein can be associated with RNA synthesis. The first change would yield a catalytically active protein, and the second one would occur during the transition between the initiation and the elongation modes. The mutant M10 was active for elongation, indicating that the K456A R457A mutation does not affect catalysis but alters a promoter-dependent preelongation step. The defect observed with this mutant was partially suppressed by Mn2+ but not by 500 μM GTP, suggesting that Mn2+ does not function by increasing the affinity of the enzyme for GTP. It has been previously reported that Mn2+ promotes nucleotide misincorporation, which could explain the activity of the mutant (5). However, we speculate that binding of Mn2+ could facilitate a conformational change in the mutant protein that occurs naturally in the WT enzyme.

In our working model, we propose that interaction of specific nucleotides of the promoter SLA with NS5 induces a conformational change in the protein that involves the F1 motif, yielding a catalytically active enzyme. Crystallization of the SLA-RdRp complex will be necessary to provide the molecular information necessary to understand in depth this viral process. Structural and functional studies of the flavivirus NS5 protein in the last few years provided a great deal of information about viral RNA synthesis (for a review, see reference 23). However, molecular details of the specific interactions between NS5 and the viral genome during the initiation process are still missing. We have recently provided a new model for the dynamic nature of the DENV genome during viral replication (33). It is possible that structures or transient conformations in the RNA genome could facilitate or repress the initiation of RNA synthesis (33). We believe that understanding at the molecular level the process of flavivirus genome replication will provide new avenues for antiviral intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Richard Kinney for the DENV cDNA infectious clone and members of the Gamarnik laboratory for helpful discussions. We also thank Felix Rey for important suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from HHMI and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Argentina). A.V.G. and C.V.F. are members of the Argentinean Council of Investigation (CONICET). N.G.I. was funded by CONICET.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ackermann M., Padmanabhan R. 2001. De novo synthesis of RNA by the dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase exhibits temperature dependence at the initiation but not elongation phase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:39926–39937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ago H., et al. 1999. Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. Structure 7:1417–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez D. E., De Lella Ezcurra A. L., Fucito S., Gamarnik A. V. 2005. Role of RNA structures present at the 3′ UTR of dengue virus on translation, RNA synthesis, and viral replication. Virology 339:200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvarez D. E., Filomatori C. V., Gamarnik A. V. 2008. Functional analysis of dengue virus cyclization sequences located at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Virology 375:223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arnold J. J., Ghosh S. K., Cameron C. E. 1999. Poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol). Divalent cation modulation of primer, template, and nucleotide selection. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37060–37069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ashour J., Laurent-Rolle M., Shi P. Y., Garcia-Sastre A. 2009. NS5 of dengue virus mediates STAT2 binding and degradation. J. Virol. 83:5408–5418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bressanelli S., Tomei L., Rey F. A., De Francesco R. 2002. Structural analysis of the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase in complex with ribonucleotides. J. Virol. 76:3482–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bruenn J. A. 2003. A structural and primary sequence comparison of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:1821–1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buckley A., Gaidamovich S., Turchinskaya A., Gould E. A. 1992. Monoclonal antibodies identify the NS5 yellow fever virus non-structural protein in the nuclei of infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 73:1125–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butcher S. J., Grimes J. M., Makeyev E. V., Bamford D. H., Stuart D. I. 2001. A mechanism for initiating RNA-dependent RNA polymerization. Nature 410:235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi K. H., et al. 2004. The structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from bovine viral diarrhea virus establishes the role of GTP in de novo initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4425–4430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dong H., et al. 2010. Biochemical and genetic characterization of dengue virus methyltransferase. Virology 405:568–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Egloff M. P., Benarroch D., Selisko B., Romette J. L., Canard B. 2002. An RNA cap (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase in the flavivirus RNA polymerase NS5: crystal structure and functional characterization. EMBO J. 21:2757–2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrer-Orta C., Arias A., Escarmis C., Verdaguer N. 2006. A comparison of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrer-Orta C., et al. 2004. Structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and its complex with a template-primer RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279:47212–47221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Filomatori C. V., Iglesias N. G., Villordo S. M., Alvarez D. E., Gamarnik A. V. 2011. RNA sequences and structures required for the recruitment and activity of the dengue virus polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 286:6929–6939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Filomatori C. V., et al. 2006. A 5′ RNA element promotes dengue virus RNA synthesis on a circular genome. Genes Dev. 20:2238–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kapoor M., et al. 1995. Association between NS3 and NS5 proteins of dengue virus type 2 in the putative RNA replicase is linked to differential phosphorylation of NS5. J. Biol. Chem. 270:19100–19106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinney R. M., et al. 1997. Construction of infectious cDNA clones for dengue 2 virus: strain 16681 and its attenuated vaccine derivative, strain PDK-53. Virology 230:300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lesburg C. A., et al. 1999. Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from hepatitis C virus reveals a fully encircled active site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:937–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lodeiro M. F., Filomatori C. V., Gamarnik A. V. 2009. Structural and functional studies of the promoter element for dengue virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 83:993–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malet H., et al. 2007. Crystal Structure of the RNA Polymerase domain of the West Nile virus non-structural protein 5. J. Biol. Chem. 282:10678–10689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malet H., et al. 2008. The flavivirus polymerase as a target for drug discovery. Antiviral Res. 80:23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mazzon M., Jones M., Davidson A., Chain B., Jacobs M. 2009. Dengue virus NS5 inhibits interferon-alpha signaling by blocking signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 phosphorylation. J. Infect. Dis. 200:1261–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng K. K., et al. 2002. Crystal structures of active and inactive conformations of a caliciviral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1381–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nomaguchi M., et al. 2003. De novo synthesis of negative-strand RNA by dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in vitro: nucleotide, primer, and template parameters. J. Virol. 77:8831–8842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pryor M. J., et al. 2007. Nuclear localization of dengue virus nonstructural protein 5 through its importin alpha/beta-recognized nuclear localization sequences is integral to viral infection. Traffic 8:795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ray D., et al. 2006. West Nile virus 5′-cap structure is formed by sequential guanine N-7 and ribose 2′-O methylations by nonstructural protein 5. J. Virol. 80:8362–8370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Selisko B., et al. 2006. Comparative mechanistic studies of de novo RNA synthesis by flavivirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Virology 351:145–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steffens S., Thiel H. J., Behrens S. E. 1999. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of different members of the family Flaviviridae exhibit similar properties in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2583–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tao Y., Farsetta D. L., Nibert M. L., Harrison S. C. 2002. RNA synthesis in a cage—structural studies of reovirus polymerase lambda3. Cell 111:733–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teramoto T., et al. 2008. Genome 3′-end repair in dengue virus type 2. RNA 14:2645–2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Villordo S. M., Alvarez D. E., Gamarnik A. V. 2010. A balance between circular and linear forms of the dengue virus genome is crucial for viral replication. RNA 16:2325–2335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Villordo S. M., Gamarnik A. V. 2009. Genome cyclization as strategy for flavivirus RNA replication. Virus Res. 139:230–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yap T. L., et al. 2007. Crystal structure of the dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase catalytic domain at 1.85-angstrom resolution. J. Virol. 81:4753–4765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yon C., et al. 2005. Modulation of the nucleoside triphosphatase/RNA helicase and 5′-RNA triphosphatase activities of dengue virus type 2 nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) by interaction with NS5, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27412–27419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. You S., Padmanabhan R. 1999. A novel in vitro replication system for dengue virus. Initiation of RNA synthesis at the 3′-end of exogenous viral RNA templates requires 5′- and 3′-terminal complementary sequence motifs of the viral RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33714–33722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou Y., et al. 2007. Structure and function of flavivirus NS5 methyltransferase. J. Virol. 81:3891–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]