Abstract

Purpose

Mental health problems disproportionately affect women, particularly during childbearing years. However, there is a paucity of research on the determinants of postpartum mental health problems using representative US populations. Taking a life course perspective, we determined the potential risk factors for postpartum mental health problems, with a particular focus on the role of mental health before and during pregnancy.

Methods

We examined data on 1,863 mothers from eleven panels of the 1996-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Poor postpartum mental health was defined using self-reports of mental health conditions, symptoms of mental health conditions, or global mental health ratings of “fair” or “poor.”

Results

9.5% of women reported experiencing postpartum mental health problems, with over half of these women reporting a history of poor mental health. Poor pre-pregnancy mental health and poor antepartum mental health both independently increased the odds of having postpartum mental health problems. Staged multivariate analyses revealed that poor antepartum mental health attenuated the relationship between pre-pregnancy and postpartum mental health problems. Additionally, significant disparities exist in women's report of postpartum mental health status.

Conclusions

While poor antepartum mental health is the strongest predictor of postpartum mental health problems, pre-pregnancy mental health is also important. Accordingly, health care providers should identify, treat, and follow women with a history of poor mental health, as they are particularly susceptible to postpartum mental health problems. This will ensure that women and their children are in the best possible health and mental health during the postpartum period and beyond.

Keywords: Pregnancy, mental health, prevalence, population-based, antepartum mental health, postpartum mental health

Introduction

Postpartum mood disorders represent a major public health issue affecting between ten to twenty percent of mothers (Beck, 2001; Chaudron et al., 2001; Mayberry, Horowitz, & Declercq, 2007). Pregnancy and stressors related to caring for a newborn may increase the risk of poor mental health among women, which in turn, may have serious detrimental effects on the health and well-being of the mother and her child. The negative effects of postpartum depression on child growth and development, both immediate and long lasting, include impaired attachment, behavior problems, social and cognitive limitations, and low self-esteem (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Grace, Evindar, & Stewart, 2003; Robertson, Grace, Wallington, & Stewart, 2004).

Many studies suggest that depression or depressive symptoms may manifest at any time during the first postpartum year and beyond (Chaudron, Kitzman, Szilagyi, Sidora-Arcoleo, & Anson, 2006; Dietz et al., 2007; Gavin et al., 2005; Gaynes et al., 2005; Gjerdingen &Yawn, 2007). Although symptoms may subside within a few months, for some mothers, postpartum depression becomes prolonged or chronic in months or years after giving birth (Goodman, 2004). Mental health problems prior to and during pregnancy are risk factors for postpartum mental health problems (Robertson et al., 2004). Additional risk factors include experiencing anxiety or stressful life events during pregnancy, poor social support, partner or marital conflict, neuroticism, low self-esteem, obstetric complications, low socioeconomic status or income, and unplanned or unwanted pregnancy (Beck, 2001; Kirpinar, Gözüm, & Pasinlioǧlu, 2010; Robertson et al., 2004). The socio-cultural environment may also influence the effects of these risk factors on postpartum mental health; however, the culturally specific components of postpartum mental health are not well understood (Huang, Wong, Ronzio, & Yu, 2007).

These factors likely accumulate over the life course such that they impact one another to increase poor postpartum outcomes. While pre-pregnancy mental health problems have been shown to predict antepartum mental health problems (Witt et al., 2010), there is a paucity of research examining the relationship among pre-pregnancy, antepartum, and postpartum mental health. In fact, no study has examined if and to what extent poor antepartum mental health mediates the relationship between pre-pregnancy mental health problems and poor postpartum mental health. To our knowledge, our study is the first to approach this research question.

Our research draws upon Misra and colleagues' (Misra, Guyer, & Allston, 2003) framework of perinatal health that integrates the life course developmental perspective (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002) with a model of health determinants (Evans & Stoddart, 1990). This model posits that perinatal health is influenced by both cumulative effects of events across the lifespan and intergenerational effects. In addition, multiple determinants and their interactions likely influence women's health during pregnancy. Central to this framework is the idea that key health determinants prior to and during pregnancy have an important impact on having poor postpartum mental health.

In summary, the purpose of our study is to determine if antepartum mental health status mediates the relationship between pre-pregnancy and postpartum mental health problems. We adopt a life course perspective, recognizing that mental health before, during and after pregnancy may be interrelated in a complex fashion and the associations between these stages may differentially affect outcomes. The current study provides nationally representative prevalence estimates and examines the independent associations of a wide variety of risk factors with poor postpartum mental health, with a particular focus on the role of mental health before and during pregnancy.

Methods

Data

MEPS

Data are from the household component of the 1996-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). The household component of the MEPS collects information about medical conditions, health status, healthcare use, and expenditures. The survey has an overlapping panel design, gathering information through five rounds of data collection over a two and a half year period. Each year, a new panel begins with a sample selected from the households who participated in the previous year's National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which yields a nationally representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized population of the United States, with oversampling for blacks and Hispanics. Data are available from eleven panels of the 1996-2006 MEPS. Detailed methodology and a description of data available in MEPS are available at http://www.meps.ahrq.gov.meps.web.

Pregnancy Detail Files

At each round of data collection, if a woman in the household was pregnant, additional data specific to pregnancy were obtained. Because the pregnancy data are not publicly available, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Data Center created a custom data set incorporating pregnancy data from each of the eleven panels that was linked to the household component data set.

Sample

Women included in the eleven panels of the Pregnancy Detail files who had pre-pregnancy, antepartum, and postpartum data associated with a livebirth were eligible for this analysis (n=2,076). Subjects were ineligible for inclusion in the study if they had missing information on age, race/ethnicity, education, marital/partner status, poverty threshold categories, or physical health status during pregnancy (n=36) or a zero person weight (n=115). Furthermore, women who reported other mental health conditions, besides depression or anxiety, and/or did not report depression, anxiety, or poor self-reported mental health (n=62) were ineligible for the study. The final sample thus includes 1,863 women. Only one pregnancy per woman was included in the analyses. If a woman had more than one eligible pregnancy based on the previous exclusion criteria (n=133), a random number generator was used to randomly select a single pregnancy for inclusion in the analysis. A flag was subsequently created to document the number of pregnancies during the MEPS period.

Variable Definitions

Reporting of Health Conditions in the MEPS

Health condition data were collected from household respondents during each round of the MEPS as verbatim text and assigned International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes by professional coders. Women's health conditions were identified through the Household Component or respondent interview of the MEPS, where household respondents were asked the following question in the Condition Enumeration Section: “We're interested in learning about health problems that may have bothered (PERSON) {since (START DATE)/between (START DATE) and (END DATE)}. Health problems include physical conditions, accidents, or injuries that affect any part of the body as well as mental or emotional health conditions, such as feeling sad, blue, or anxious about something”(AHRQ, 2010).

Dependent Variable: Postpartum Mental Health Status

Self-reported mental health conditions and subjective measures of mental health status have been associated with mental health morbidity (Fleishman & Zuvekas, 2007; Mawani & Gilmour, 2010). A woman was categorized as having poor postpartum mental health if the respondent reported any of the following at the end of the interview round in which she gave birth or in any subsequent interview rounds: 1) having a self-reported mental health condition; 2) “feeling sad, blue or anxious about something”;or 3) being in “fair” or “poor” mental health when asked, “In general, would you say that your mental health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”(Cohen et al., 1996). Respondent-reported mental health conditions were assigned truncated 3-digitICD-9codes. ICD-9 codes 296 (episodic mood disorders), 300 (anxiety state, unspecified), and 311 (depression, unspecified) were considered indicators of poor mental health. While code 296 includes major depressive disorder and other episodic mood disorders, over 96% of women with depression in the sample were identified using code 311 (depression, unspecified). Of the women reporting poor postpartum mental health, 62% self-reported fair or poor mental health, 50% reported depression (ICD-9 311), 20% reported anxiety (ICD-9 300), and 2% reported mood disorders (ICD-9 296).1

Independent Variables

Pre-pregnancy and antepartum mental health

Women were categorized as having poor pre-pregnancy or antepartum mental health if they met any of the following criteria: 1) self-reported anxiety or depression with a date of onset prior to or during their pregnancy (respectively); 2) “feeling sad, blue or anxious about something”; or 3) self-reported “fair” or “poor” mental health in any round prior to or during rounds in which they reported being pregnant (respectively). Respondent-reported mental health conditions were assigned truncated 3-digitICD-9codes. ICD-9 codes 296 (episodic mood disorders), 300 (anxiety state, unspecified), and 311 (depression, unspecified) were considered indicators of poor pre-pregnancy or antepartum mental health. The pre-pregnancy period for which women could report poor mental health was between less than one and 18 months in length. Of the women reporting poor pre-pregnancy mental health, 72% self-reported fair or poor mental health, 29% reported depression (ICD-9 311), 15% reported anxiety (ICD-9 300), and 2% reported mood disorders (ICD-9 296). Of the women reporting poor antepartum mental health, 56% self-reported fair or poor mental health, 46% reported depression (ICD-9 311), 18% reported anxiety (ICD-9 300), and 2% reported mood disorders (ICD-9 296).2

Maternal and family sociodemographic factors

Maternal and family sociodemographic variables included age (14-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, and 35+), race/ethnicity (White (non-Hispanic), Black (non-Hispanic), Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic), other (non-Hispanic), or Hispanic), education (no or some high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate or beyond), marital/partner status (married or living with partner, never married, and divorced, separated or widowed), and metropolitan statistical area (MSA). Health insurance status was grouped into the following mutually exclusive categories: no health insurance, any publicly funded health insurance (Medicaid and/or Medicare), and private health insurance only. Family incomes were classified as below 100%, 100–199%, 200–399%, and 400% or more of the federal poverty threshold. Household composition was evaluated by the number of children under 5 years of age, the number of children 5-17 years of age, and the number of additional adults in the household or family unit (other than pregnant woman and her spouse or partner).

Health-related risk factors

Pregnancy complications

In the Pregnancy Detail File of the MEPS, respondents were asked “Looking at this card, which of these complications, if any, did (PERSON) experience during this pregnancy?” The responses on the card included the following categories: 1) high blood pressure, toxemia, pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia; 2) anemia; 3) diabetes, gestational diabetes, or high blood sugar; 4) low lying placenta (placenta previa); 5) vaginal bleeding; 6) premature labor; or 7) none of these complications. A woman was considered as having a pregnancy complication if she indicated any one of the conditions (categories 1-6) during her pregnancy.

The number of pregnancies during the MEPS period, smoking status while pregnant, substance abuse, and the presence of a chronic medical condition were each evaluated as dichotomous variables. Women with substance abuse problems or chronic medical conditions were identified through the Household Component or respondent interview of the MEPS, where in the Condition Enumeration Section household respondents were asked if they had experienced “health problems…as well as mental or emotional health conditions…”(AHRQ, 2010). Self-reported substance abuse was defined as report of problems in the pre-pregnancy and antepartum period and included: alcohol dependence syndrome (ICD-9 303), drug dependence (ICD-9 304),and nondependent abuse of drugs (ICD-9 305). Self-reported chronic conditions included: diabetes (ICD-9 250), chronic bronchitis (ICD-9 491), high cholesterol (ICD-9 272), primary hypertensive disease (ICD-9 401-404), asthma (ICD-9 493), and renal disease (ICD-9 403, 404, 582, 583, 585-588).

Women who reported “fair” or “poor” health in response to the question, “In general, would you say that your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” during any round of the MEPS while pregnant were considered to be in poor physical health during pregnancy.

Analytic Approach

SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used to construct the analytic files and STATA 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used to perform all analyses, accounting for the complex design of the MEPS. The standard errors were corrected due to clustering within strata and the primary sampling unit, and applied survey weights were used to produce estimates that account for the complex survey design, unequal probabilities of selection, and survey non-response.

Descriptive Analysis

Chi-squared analyses were used to test for differences in sociodemographic and health characteristics by postpartum mental health status. If differences were found in the overall chi-square tests (at the 10% level), each subgroup was tested for statistical significance relative to all other subgroups combined, in order to identify which subgroup (s) were influencing the overall group significance.

Mediation Analysis

The Sobel test (Baron & Kenny, 1986) was used to determine if and to what extent poor antepartum mental health mediated the relationship between pre-pregnancy mental health and postpartum mental health problems. Variances were adjusted to correctly account for the dichotomous outcome and mediator.

Multivariate Analysis

For the logistic regression analysis, models were fit to identify the factors that were associated with the poor postpartum mental health status. Based on previous empirical literature, we chose to include age (five categories: 14-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35+); race/ethnicity (five categories: White (non-Hispanic), Black (non-Hispanic), Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic), other (non-Hispanic), Hispanic);education (four categories: no or some high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate or beyond); marital status (three categories: married/lives with partner, never married, divorced/separated/widowed);MSA status (two categories: urban or rural);health insurance status (three categories: private only, any publicly funded insurance, no insurance);ratio of family income to poverty threshold (four categories: below 100%, 100-199%, 200-399%, 400%+); number of adults in the household or family in addition to the parents (two categories: zero versus one or more); number of children less than 5 (three categories: zero, one, or two or more); number of children ages 5-17 years (three categories: zero, one, or two or more);any pregnancy complication (two categories: yes or no); substance abuse before or during pregnancy (two categories: yes or no); the number of pregnancies during the MEPS period (two categories: one versus two or more);and physical health status during pregnancy (two categories: excellent/very good/good, fair/poor) in the model. The presence of chronic conditions was not included in the final model due to the possible collinearity with the self-reported health status. In addition, we did not include smoking in the final analysis, since MEPS began collecting data for this variable starting in 2000, leading to inadequate sample size.

The University of Wisconsin – Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board considered this study exempt from review because the data were already collected and de-identified.

Results

Overall, 9.5% of women in the US reported poor postpartum mental health. Compared to women without postpartum mental health problems, women with postpartum mental health problems were less likely to be married and more likely to be divorced, separated, or widowed. Women with postpartum mental health problems were also more likely to be without a high school diploma, have a pregnancy complication, have a chronic medical condition, report substance abuse, report smoking during pregnancy, rate their physical health status during pregnancy as “fair” or “poor,” live below 100% of the federal poverty threshold, and have publicly funded insurance. Women with postpartum mental health problems were less likely to be Hispanic and without insurance. Women with poor postpartum mental health were more likely to have poor pre-pregnancy mental health and poor antepartum mental health than women with no postpartum mental health problems (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of US Mothers by Postpartum Mental Health Status, 1996-2006 MEPS.

| Postpartum Mental Health Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | No Mental Health Problems reported | Poor Mental Health | Chi-square P-value | P-value for Individual category v. all others | |

| TOTAL: weighted | 3,047,420 | 2,757,565 | 289,855 | ||

| % | 90.5% | 9.5% | |||

| TOTAL: unweighted | 1,863 | 1,697 | 166 | ||

| % | 90.3% | 9.7% | |||

| Pre-Pregnancy and Antepartum Mental Health | |||||

| Poor pre-pregnancy mental health | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 6.4% | 25.9% | |||

| No | 93.6% | 74.1% | |||

| Poor antepartum mental health | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 4.5% | 42.5% | |||

| No | 95.5% | 57.5% | |||

| Maternal and Family Sociodemographic Factors | |||||

| Age | 0.92 | ||||

| 14-19 | 8.6% | 10.9% | |||

| 20-24 | 25.6% | 24.9% | |||

| 25-29 | 28.1% | 26.1% | |||

| 30-34 | 25.1% | 24.3% | |||

| 35+ | 12.6% | 13.8% | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.08 | ||||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 61.1% | 66.1% | 0.30 | ||

| Black (Non-Hispanic) | 12.9% | 10.5% | 0.46 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander (Non-Hispanic) | 4.2% | 7.9% | 0.19 | ||

| Other (Non-Hispanic) | 1.5% | 3.1% | 0.17 | ||

| Hispanic | 20.3% | 12.4% | 0.01 | ||

| Education status | 0.04 | ||||

| No or some high school | 21.1% | 32.6% | 0.004 | ||

| High school graduate | 26.1% | 19.1% | 0.09 | ||

| Some college | 22.4% | 20.5% | 0.62 | ||

| College or beyond | 30.3% | 27.8% | 0.62 | ||

| Marital status | 0.02 | ||||

| Married or living with partner | 74.7% | 64.7% | 0.04 | ||

| Never married | 21.5% | 27.6% | 0.20 | ||

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 3.8% | 7.8% | 0.02 | ||

| MSA Status | 0.91 | ||||

| Urban | 85.4% | 85.0% | |||

| Rural | 14.6% | 15.0% | |||

| Health Insurance Status | 0.001 | ||||

| Private insurance only | 69.5% | 65.5% | 0.34 | ||

| Any publicly funded insurance | 19.4% | 29.6% | 0.01 | ||

| No insurance | 11.1% | 4.9% | 0.003 | ||

| Ratio of family income to poverty threshold | 0.05 | ||||

| Below 100% | 20.2% | 29.9% | 0.02 | ||

| 100-199% | 20.9% | 15.4% | 0.07 | ||

| 200-399% | 27.9% | 28.7% | 0.85 | ||

| 400%+ | 31.0% | 26.0% | 0.33 | ||

| Number of adults in household/family in addition to parents | 0.17 | ||||

| 0 | 76.7% | 71.0% | |||

| 1 or more | 23.3% | 29.0% | |||

| Number of children (< 5yrs old) | 0.65 | ||||

| 0 | 57.1% | 60.9% | |||

| 1 | 33.6% | 29.7% | |||

| 2 or more | 9.3% | 9.4% | |||

| Number of children (5-17yrs) | 0.58 | ||||

| 0 | 64.0% | 67.5% | |||

| 1 | 22.1% | 21.5% | |||

| 2 or more | 14.0% | 11.0% | |||

| Maternal Health-Related Risk Factors | |||||

| Any Pregnancy Complication | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 38.6% | 62.9% | |||

| No | 61.4% | 37.1% | |||

| Number of Pregnancies during MEPS period | 0.34 | ||||

| 1 | 93.0% | 94.8% | |||

| 2 or more | 7.0% | 5.2% | |||

| Smoked during pregnancy* | n=804 | n=85 | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 9.1% | 32.5% | |||

| No | 90.9% | 67.5% | |||

| Substance Abuse | 0.004 | ||||

| Yes | 0.8% | 4.2% | |||

| No | 99.2% | 95.8% | |||

| Chronic Medical Conditions | 0.0080 | ||||

| Yes | 5.1% | 11.4% | |||

| No | 94.9% | 88.6% | |||

| Self-reported Physical Health Status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Excellent, Very Good, or Good | 94.2% | 77.2% | |||

| Fair or Poor | 5.8% | 22.8% | |||

MSA: Metropolitan Statistical Area, MEPS: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Data from 2000-2006 only

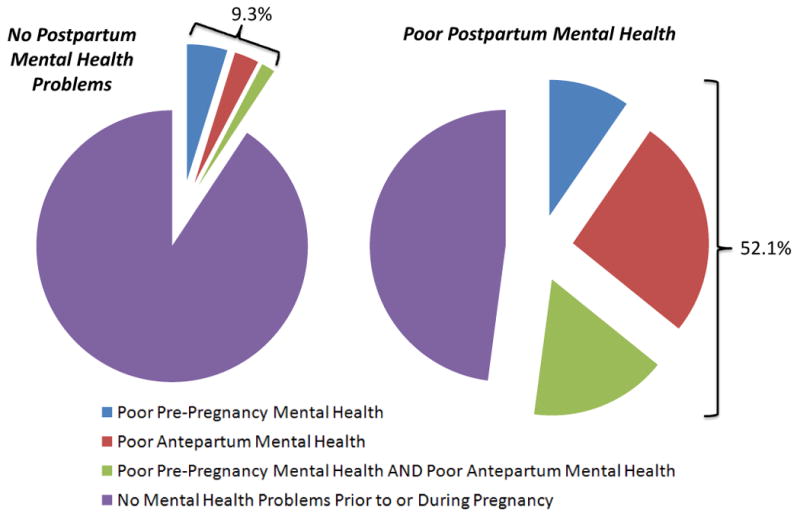

As seen in the Figure, of the women with postpartum mental health problems, 52.1% reported some history of poor mental health (poor pre-pregnancy mental health, poor antepartum mental health, or both), and 47.9% did not report any mental health problems during the study period. In contrast, of the women with no postpartum mental health problems, only 9.3% reported some history of poor mental health, and 90.7% did not report any mental health problems during the study period.

Figure.

Mental Health Problems Prior to and During Pregnancy by Postpartum Mental Health Status. Of the women with no postpartum mental health problems, 9.3% reported some history of poor mental health (4.8% reported poor pre-pregnancy mental health, 2.9% reported poor antepartum mental health, 1.6% reported both reported poor pre-pregnancy mental health and poor antepartum mental health), and 90.7% did not report any mental health problems during the study period. Of the women with postpartum mental health problems, 52.1% reported some history of poor mental health (9.6% reported poor pre-pregnancy mental health, 26.2% reported poor antepartum mental health, 16.3% reported both reported poor pre-pregnancy mental health and poor antepartum mental health), and 47.9% did not report any mental health problems during the study period.

Women with pre-pregnancy mental health problems were over 5 times more likely to experience poor postpartum mental health, not adjusting for covariates (OR [95% CI]: 5.14 [3.24 – 8.17]; Table 2, Model 1), while women with poor antepartum mental health were nearly 16 times more likely to be in poor mental health postpartum (unadjusted OR [95% CI]: 15.70 [10.26 – 24.03]; data not shown). In a single, mutually adjusted model, these odds ratios were attenuated (OR [95% CI]: 2.20 [1.20 – 4.04], 12.51 [7.96 – 19.67] for pre-pregnancy and antepartum mental health problems, respectively; Table 2 Model 2). The Sobel test for mediation between postpartum and pre-pregnancy mental health by antepartum mental health was significant (p<0.0001; data not shown).

Table 2. Multivariate Analyses of the Odds of Poor Postpartum Mental Health among US Mothers, 1996-2006 MEPS.

| Model 1 - Odds ratio of poor postpartum mental health | Model 2 - Odds ratio of poor postpartum mental health | Model 3 - Odds ratio of poor postpartum mental health | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | OR | CI | OR | CI | ||||

| Pre-Pregnancy and Antepartum Mental Health | |||||||||

| Poor pre-pregnancy mental health | |||||||||

| Yes | 5.14 | 3.24 | 8.17 | 2.20 | 1.20 | 4.04 | 1.90 | 1.02 | 3.57 |

| No | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| Poor antepartum mental health | |||||||||

| Yes | 12.51 | 7.96 | 19.67 | 11.36 | 6.45 | 19.99 | |||

| No | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||||

| Maternal and Family Sociodemographic Factors | |||||||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 14-19 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 1.23 | ||||||

| 20-24 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 1.71 | ||||||

| 25-29 | 0.74 | 0.39 | 1.41 | ||||||

| 30-34 | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| 35+ | 1.07 | 0.58 | 1.97 | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Black (Non-Hispanic) | 0.65 | 0.30 | 1.39 | ||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander (Non-Hispanic) | 2.87 | 1.09 | 7.54 | ||||||

| Other (Non-Hispanic) | 1.93 | 0.57 | 6.58 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.88 | ||||||

| Education status | |||||||||

| No or some high school | 3.72 | 1.50 | 9.23 | ||||||

| High school graduate | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Some college | 1.56 | 0.75 | 3.23 | ||||||

| College or beyond | 1.62 | 0.77 | 3.42 | ||||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married or living with partner | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Never married | 1.03 | 0.48 | 2.18 | ||||||

| Divorced / separated / widowed | 1.53 | 0.50 | 4.74 | ||||||

| MSA Status | |||||||||

| Urban | 1.03 | 0.56 | 1.93 | ||||||

| Rural | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Health Insurance Status | |||||||||

| Private insurance only | 3.83 | 1.67 | 8.82 | ||||||

| Any publicly funded insurance | 3.98 | 1.57 | 10.06 | ||||||

| No insurance | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Ratio of family income to poverty threshold | |||||||||

| Below 100% | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| 100-199% | 0.67 | 0.35 | 1.29 | ||||||

| 200-399% | 1.05 | 0.48 | 2.30 | ||||||

| 400%+ | 0.70 | 0.29 | 1.70 | ||||||

| Number of adults in household / family in addition to parents | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| 1 or more | 1.76 | 0.90 | 3.45 | ||||||

| Number of children (< 5yrs old) | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| 1 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 1.53 | ||||||

| 2 or more | 1.01 | 0.51 | 2.02 | ||||||

| Number of children (5-17yrs) | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| 1 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.14 | ||||||

| 2 or more | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.97 | ||||||

| Maternal Health-Related Risk Factors | |||||||||

| Any Pregnancy Complication | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.99 | 1.25 | 3.18 | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Substance Abuse | |||||||||

| Yes | 2.21 | 0.55 | 8.96 | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Number of Pregnancies during MEPS period | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| 2 or more | 0.47 | 0.18 | 1.24 | ||||||

| Self-reported Physical Health Status | |||||||||

| Excellent / Very Good / Good | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Fair or Poor | 2.78 | 1.27 | 6.11 | ||||||

OR: Odds ratio; CI: 95% Confidence Interval, MSA: Metropolitan Statistical Area, MEPS: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

In the final model of the multivariate analysis (Table 2, Model 3), women who had poor pre-pregnancy mental health and women who had poor antepartum mental health had a higher odds of poor postpartum mental health (OR [95% CI]: 1.90 [1.02 – 3.57], 11.36 [6.45 – 19.99], respectively) after conditioning on a large set of maternal and family sociodemographic factors and health-related risk factors. Women of Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) race, women who did not have a high school diploma, women with private insurance, and women with publicly funded insurance were more likely to experience poor postpartum mental health (OR [95% CI]: 2.87 [1.09 – 7.5], 3.72 [1.50 – 9.23], 3.83 [1.67 – 8.82], 3.98 [1.57 – 10.06], respectively). Hispanic women were less likely to have postpartum mental health problems (OR [95% CI]: 0.48 [0.27 – 0.88]). Women who experienced any pregnancy complication and women in “fair” or “poor” self-rated physical health during pregnancy were more likely to have postpartum mental health problems (OR [95% CI]: 1.99 [1.25 – 3.18] and 2.78 [1.27 – 6.11], respectively).

Discussion

This national study of women's postpartum mental health problems contributes new and important findings to the literature. Taking a life course perspective, our national, population-based study is the first to show that mental health problems both before and during pregnancy are strong predictors of postpartum mental health problems. Of note, our data show that poor mental health during pregnancy mediates the relationship between pre-pregnancy and postpartum mental health problems.

Overall, 9.5% of mothers experienced poor mental health in the postpartum period, similar to previous studies on postpartum depression (O'Hara & Swain, 1996; Robertson et al., 2004). The single most important risk factor was poor antepartum mental health, which increased the odds of poor postpartum mental health by over 11 fold. Consistent with our findings, there have been several clinic-based and non-US reports showing that approximately half of women who experience depressive symptoms during the postpartum period also displayed depressive symptoms during the antepartum period (Chaudron et al., 2001; Dietz et al., 2007; Gotlib, Whiffen, Mount, Milne, & Cordy, 1989; Yonkers et al., 2009). This suggests that screening during antepartum check-ups may be particularly useful for identifying and treating such women and thereby reducing the risk of postpartum mental health problems.

Strikingly, over 50 percent of the women with postpartum mental health problems in our study reported having a history of poor mental health, indicating a distinct opportunity for early detection and intervention to prevent postpartum mental health problems. Furthermore, access to consistent healthcare will ensure that women in poor mental health are identified, treated and monitored-- all in an effort to improve long-term maternal mental health outcomes.

Coupled with continuous care, serial screening may be the best way to enhance detection overall and to provide sufficient opportunities for interventions (Dietz et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008). Such screenings could take place during routine obstetrics and gynecology visits (Gjerdingen, Crow, McGovern, Miner, & Center, 2009; Gordon, Cardone, Kim, Gordon, & Silver, 2006; Scholle, Haskett, Hanusa, Pincus, & Kupfer, 2003; Seehusen, Baldwin, Runkle, & Clark, 2005; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999) before, during, and after pregnancy, as well as during well-child visits (Chaudron, Szilagyi, Campbell, Mounts, & McInerny, 2007). Ultimately, it will be important for screening to occur in a variety of settings over the life course in order to ensure that women are effectively screened and treated for mental health problems, regardless of where or when they interface with the healthcare system.

Educating providers about existing validated screening tools (Feinberg et al., 2006; Gjerdingen &Yawn, 2007; Gordon et al., 2006), and reimbursing them for their time both offer promising avenues for promoting the use of appropriate instruments (Feinberg et al., 2006). In fact, in the two years since the state of Illinois initiated reimbursement for maternal depression screening during prenatal visits, postpartum visits and during infant well-child or episodic visits (Feinberg et al., 2006; Murphy, 2004), the number of antepartum and postpartum women being screened for perinatal depression more than doubled (Maram, 2008). Alternatively, incorporating a mental health screening into the nursing assessment of women and mothers of infant patients would be an efficient way to include mental health screening in standard health care practice, and would not require reimbursement. Regardless of which provider conducts the screening, education about mental health screening should begin in early coursework for all providers to promote and facilitate its execution in the clinical setting.

Screening is only the first step in the process of care and will only improve outcomes when it is followed-up with effective diagnostic evaluation, appropriate and timely referrals, and effective and adequate treatment (Chaudron, Szilagyi, Kitzman, Wadkins, & Conwell, 2004; Evins, Theofrastous, & Galvin, 2000; Georgiopoulos, Bryan, Wollan, & Yawn, 2001; Gjerdingen &Yawn, 2007; Hearn et al., 1998; Heneghan, Silver, Bauman, & Stein, 2000; Kim et al., 2008; Morris-Rush, Freda, & Bernstein, 2003; Pignone et al., 2002). Several studies have implemented routine screenings in conjunction with referral services and provider education (Chaudron et al., 2004; Gordon et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2005), and findings suggest that the key to the successful application of routine screening involves the establishment of effective referral and support systems that function both for the provider and for the screen-positive women. This care coordination would facilitate referrals to appropriate mental health professionals who have the ability to determine appropriate treatment.

This study shows that significant disparities exist within women's report of mental health problems in the postpartum period, consistent with previous work (Chaudron et al., 2001; Goyal, Gay, & Lee, 2010; Mayberry et al., 2007; Mora et al., 2009; Robertson et al., 2004). Thus, our results may be useful for identifying women who are most vulnerable to postpartum mental health problems.

In our study, Asian or Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) mothers were almost three times more likely to report postpartum mental health problems as compared with their white (non-Hispanic) counterparts. In the only other existing population-based study, Hayes and colleagues (Hayes, Ta, Hurwitz, Mitchell-Box, & Fuddy, 2010) found an increased risk of postpartum depressive symptoms among Asian and Pacific Islanders in Hawaii. Asian American women may be particularly vulnerable to mental health problems due to chronic stress stemming from perceived discrimination, living as a minority, and undervaluation as a woman in traditional Asian culture (Hahm, Ozonoff, Gaumond, & Sue, 2010). Culture may be an important context in which providers examine postpartum mental health, although further research is needed to tease apart the complex relationship between culture, risk factors such as social support, and poor postpartum mental health.

Our results show that Hispanic women were less likely than white women to report poor postpartum mental health. This may be the result of underreporting due to patient beliefs and attitudes regarding mental illness (Cooper et al., 2003), or preferential diagnosis among white patients compared with Hispanic patients, as suggested by Borowsky et al., who reported that physician recognition of mental illness varies by race and ethnicity (Borowsky et al., 2000). Missed diagnoses or negative views of treatment for depression may result in delayed or forgone care, which is of particular concern for Hispanic women, who have been found to underutilize specialty mental health care (Miranda & Cooper, 2004).

Our study found that women who had less than a high school degree were over three times more likely to suffer from postpartum mental health problems. Low education is an indicator of socioeconomic status and has been associated with an increased risk for postpartum mental health problems (Goyal et al., 2010; Mayberry et al., 2007). Women of low socioeconomic status may experience increased stressors and have fewer resources to cope with them. Consequently, it is imperative for providers to understand women's psychosocial context to facilitate effective identification of women at greatest risk for postpartum mental health problems.

Our study also found that being insured increased the odds of experiencing poor postpartum mental health, which may be a reflection of access to care. Previous work has indicated that insurance coverage leads to greater access to recommended care, improved quality of care, and better health outcomes (McWilliams, 2009). Furthermore, individuals who have improved access to care, facilitated by health insurance, may be more aware of their health and mental health status and thus more likely to report experiencing health or mental health problems.

We found that women who experience pregnancy complications or who are in poor health are more likely to experience postpartum mental health problems. This result is supported by studies showing that hospitalization during pregnancy (Blom et al., 2010) or pregnancy related complications (Blom et al., 2010; Robertson et al., 2004) increase the risk of postpartum depression. Blom et al. postulate that physical and hormonal changes, physical morbidity (including pain, tiredness, and limitations), and/or feelings of worry, disappointment and failure, could explain such findings (Blom et al., 2010).

Implications for Policy and Practice

This study has important implications for policy and practice. Given the longitudinal relationship of pre-pregnancy mental health with antepartum mental health, and subsequently post-partum mental health, the virtues of screening across the life course cannot be overemphasized. However, to facilitate mental health screening over the life course, screening should be covered by insurance and providers should be adequately reimbursed for conducting screening. Furthermore, timely and effective treatment for mental health problems will be necessary to ‘break the chain’ of women's poor mental health. Many women may not be receiving adequate treatment (Witt et al., 2009) based on currently accepted guidelines, which may, in part, be caused by barriers to care. Accordingly, it is essential that health insurance policies include coverage for both mental health screening and treatment to ensure that these barriers do not prevent women from receiving adequate treatment. Accessibility of mental health services, care coordination, and provider expertise should guide the recommendation of treatment options, such as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, which are tailored to the specific needs of individual women.

Additionally, we found several important disparities exist in the report of poor postpartum mental health. Given that certain racial/ethnic groups and women of lower socioeconomic status are more vulnerable to poor postpartum mental health, practitioners need to be aware of the potential for differential risk among their patient population and policy should be directed at providing resources to these vulnerable groups to help mitigate the risk of poor postpartum mental health and the associated negative outcomes. Ultimately, women's preconception and reproductive health play an important role in ensuring optimal maternal and child health outcomes, thus reducing mental health disparities during the pre-pregnancy and antepartum period may ameliorate downstream disparities across the life course.

Limitations

Self-reported mental health items included in MEPS are not parallel to diagnostic criteria used in clinical settings. However, there is ample evidence that poor mental health is a robust phenomenon and self-reported measures are correlated with major depressive disorder (Hoff, Bruce, Kasl, & Jacobs, 1997). Due to the lack of data on lifetime mental health status in the MEPS, we had a limited ability to identify women with poor pre-pregnancy mental health. It is possible that women who have experienced poor mental health to varying degrees throughout their lives may have been coded as not having poor pre-pregnancy mental health. We were also limited by our inability to assess maternal smoking behavior. Data on smoking was not captured in the MEPS until 2000, resulting in an inadequate sample size for evaluation in our multivariate model.

Strengths

Our results are based on national, population-based data, providing policy makers and practitioners with a picture of the women at risk for postpartum mental health problems. Additionally, due to the large sample size and rich data set, several key correlates of poor postpartum mental health could be investigated together in one model, allowing for adjusted estimates of the contributing effect of each characteristic.

Conclusions

This nationally representative, population-based study showed that poor pre-pregnancy mental health and poor antepartum mental health were the most significant risk factors for postpartum mental health problems. Accordingly, health care providers should take a life course perspective in order to identify, treat, and follow women who may be particularly susceptible to postpartum mental health problems. However, screening and treatment should not be limited to high risk women but tailored to reach all women throughout the life course in a variety of settings. Furthermore, policy changes aimed at increasing access to mental health screening and treatment will be crucial for removing barriers to care and promoting adequate treatment in women at risk of postpartum mental health problems. Taken together, these steps will ensure that women and their children are in the best possible health and mental health during the postpartum period and beyond.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the generous funding that supported this research. TD was supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (3 U01 PE000003-06). EWH was supported by NIH (T32 HD049302; PI: Sarto).LEW was supported by a grant from the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin, Madison (PI: Witt) and a pre-doctoral NRSA Training Grant (T32 HS00083; PI: Smith). TM was supported by grants from the Center for Demography and Ecology (R24 HD047873) Center for Demography of Health and Aging (P30 AG17266), and a NIA Training Grant (T32 AG00129). WPW and TD received funding from the University of Wisconsin Institute for Research on Poverty to complete this research. WPW had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We would also like to thank the Editorial Office of the journal Women's Health Issues and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

Percentages may add up to more than 100% as categories are not mutually exclusive.

Percentages may add up to more than 100% as categories are not mutually exclusive.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- AHRQ Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 2010 Retrieved December 3, 2010, from http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/hc_survey/2005/CE95.htm.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nursing Research. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom EA, Jansen PW, Verhulst FC, Hofman A, Raat H, Jaddoe VWV, et al. Perinatal complications increase the risk of postpartum depression. The Generation R study. BJOG. 2010:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(6):381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Kitzman HJ, Szilagyi PG, Sidora-Arcoleo K, Anson E. Changes in maternal depressive symptoms across the postpartum year at well child care visits. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2006;6(4):221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Klein MH, Remington P, Palta M, Allen C, Essex MJ. Predictors, prodromes and incidence of postpartum depression. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;22(2):103–112. doi: 10.3109/01674820109049960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Campbell AT, Mounts KO, McInerny TK. Legal and ethical considerations: risks and benefits of postpartum depression screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):123–128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HIM, Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):551–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Monheit A, Beauregard K, Cohen S, Lefkowitz D, Potter D, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996;33(4):373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Whitlock EP, Hornbrook MC. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1515–1520. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Producing health, consuming health care. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;31(12):1347–1363. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evins GG, Theofrastous JP, Galvin SL. Postpartum depression: a comparison of screening and routine clinical evaluation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;182(5):1080–1082. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg E, Smith MV, Morales MJ, Claussen AH, Smith DC, Perou R. Improving women's health during internatal periods: developing an evidenced-based approach to addressing maternal depression in pediatric settings. Journal of Women's Health. 2006;15(6):692–703. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman JA, Zuvekas SH. Global self-rated mental health: associations with other mental health measures and with role functioning. Med Care. 2007;45(7):602–609. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes BN, Gavin NI, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 119. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. No. AHRQ Publication No. 05-E006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, Yawn BP. Routine screening for postpartum depression. The Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50(2):117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdingen D, Crow S, McGovern P, Miner M, Center B. Postpartum depression screening at well-child visits: validity of a 2-question screen and the PHQ-9. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):63–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdingen D, Yawn B. Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2007;20(3):280–288. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdingen D, Yawn BP. Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2007;20(3):280–288. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman J. Postpartum Depression Beyond the Early Postpartum Period. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2004;33(4):410–420. doi: 10.1177/0884217504266915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S, Gotlib I. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106(3):458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon TEJ, Cardone IA, Kim JJ, Gordon SM, Silver RK. Universal perinatal depression screening in an Academic Medical Center. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):342–347. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000194080.18261.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, Milne K, Cordy NI. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(2):269–274. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal D, Gay C, Lee KA. How much does low socioeconomic status increase the risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms in first-time mothers? Women's Health Issues. 2010;20(2):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2003;6(4):263–274. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Ozonoff A, Gaumond J, Sue S. Perceived discrimination and health outcomes: a gender comparison among Asian-Americans nationwide. Women's Health Issues. 2010;20(5):350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. The Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(3):433–479. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DK, Ta VM, Hurwitz EL, Mitchell-Box KM, Fuddy LJ. Disparities in self-reported postpartum depression among Asian, Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Women in Hawaii: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2004-2007. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010;14(5):765–773. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn G, Iliff A, Jones I, Kirby A, Ormiston P, Parr P, et al. Postnatal depression in the community. The British Journal of General Practice. 1998;48(428):1064–1066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneghan AM, Silver EJ, Bauman LJ, Stein RE. Do pediatricians recognize mothers with depressive symptoms? Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1367–1373. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff RA, Bruce ML, Kasl SV, Jacobs SC. Subjective ratings of emotional health as a risk factor for major depression in a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:167–172. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM. Depressive symptomatology and mental health help-seeking patterns of U.S.- and foreign-born mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2007;11(3):257–267. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Gordon TEJ, La Porte LM, Adams M, Kuendig JM, Silver RK. The utility of maternal depression screening in the third trimester. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;199(5):509.e501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirpinar I, Gözüm S, Pasinlioǧlu T. Prospective study of postpartum depression in eastern Turkey prevalence, socio-demographic and obstetric correlates, prenatal anxiety and early awareness. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(3-4):422–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maram BS. Perinatal Report in response to Public Act 93-0536. Springfield, IL: Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mawani FN, Gilmour H. Validation of self-rated mental health. Health Rep. 2010;21(3):61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LJ, Horowitz JA, Declercq E. Depression symptom prevalence and demographic risk factors among U.S. women during the first 2 years postpartum. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36(6):542–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams JM. Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: recent evidence and implications. The Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(2):443–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Cooper LA. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra DP, Guyer B, Allston A. Integrated perinatal health framework. A multiple determinants model with a life span approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora PA, Bennett IM, Elo IT, Mathew L, Coyne JC, Culhane JF. Distinct trajectories of perinatal depressive symptomatology: evidence from growth mixture modeling. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169(1):24–32. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Rush JK, Freda MC, Bernstein PS. Screening for postpartum depression in an inner-city population. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(5):1217–1219. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AM. Informational Notice: Screening for Perinatal Depression. Springfield, IL: Illinois Department of Public Aid; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara M, Swain A. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Olson AL, Dietrich AJ, Prazar G, Hurley J, Tuddenham A, Hedberg V, et al. Two approaches to maternal depression screening during well child visits. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005;26(3):169–176. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, Burchell CM, Orleans CT, Mulrow CD, et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: A Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals Internal Medicine. 2002;136(10):765–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholle S, Haskett R, Hanusa B, Pincus H, Kupfer D. Addressing depression in obstetrics/gynecology practice. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2003;25(2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehusen DA, Baldwin LM, Runkle GP, Clark G. Are family physicians appropriately screening for postpartum depression? The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18(2):104–112. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt W, Deleire T, Hagen E, Wichmann M, Wisk L, Spear H, et al. The prevalence and determinants of antepartum mental health problems among women in the USA: a nationally representative population-based study. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt W, Keller A, Gottlieb C, Litzelman K, Hampton J, Maguire J, et al. Access to Adequate Outpatient Depression Care for Mothers in the USA: A Nationally Representative Population-Based Study. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell DL, Stotland N, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]