Abstract

The insect-vectored disease malaria is a major world health problem. New control strategies are needed to supplement the current use of insecticides and medications. A genetic approach can be used to inhibit development of malaria parasites (Plasmodium spp.) in the mosquito host. We hypothesized that Pantoea agglomerans, a bacterial symbiont of Anopheles mosquitoes, could be engineered to express and secrete anti-Plasmodium effector proteins, a strategy termed paratransgenesis. To this end, plasmids that include the pelB or hlyA secretion signals from the genes of related species (pectate lyase from Erwinia carotovora and hemolysin A from Escherichia coli, respectively) were created and tested for their efficacy in secreting known anti-Plasmodium effector proteins (SM1, anti-Pbs21, and PLA2) in P. agglomerans and E. coli. P. agglomerans successfully secreted HlyA fusions of anti-Pbs21 and PLA2, and these strains are under evaluation for anti-Plasmodium activity in infected mosquitoes. Varied expression and/or secretion of the effector proteins was observed, suggesting that the individual characteristics of a particular effector may require empirical testing of several secretion signals. Importantly, those strains that secreted efficiently grew as well as wild-type strains under laboratory conditions and, thus, may be expected to be competitive with the native microbiota in the environment of the mosquito midgut.

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is one of the most important insect-vectored diseases, with an estimated 360 million diagnoses and 1 million deaths annually (19, 48). There has been a recent reduction in new cases of malaria due to the renewed success of mosquito vector control and drug treatment for infected individuals (6, 39, 49). The positive effects from insecticides and drugs are not a permanent solution, however, since mosquitoes and Plasmodium species have evolved resistances to them in the past and can be expected to do so in the future; thus, alternate strategies are needed to supplement these methods (12, 29).

One alternative to traditional methods of malarial control involves the use of transgenic mosquitoes expressing antimalarial effector proteins (31). Laboratory strains of such mosquitoes have been demonstrated to disrupt Plasmodium development in the gut of the insects, but this approach has some serious drawbacks, including fitness costs to the transgenic insects carrying the effector transgenes (22, 25, 34). Perhaps most importantly, introgressing effector protein genes to high frequency in natural mosquito populations is complicated and remains largely theoretical (21).

Alternatively, paratransgenesis, or the engineering of a bacterial symbiont to deliver effector proteins to combat diseases vectored by their eukaryotic host, can be employed. Developing a paratransgenesis strategy involves several steps, including the isolation of a suitable bacterial species, identification of effector proteins that can interfere with the disease agent, and the secretion of those effectors from the symbiont (7). Modifying a resident bacterial species of the mosquito gut to produce effector proteins antagonistic to Plasmodium could prove to be an efficient tool against the spread of Plasmodium to humans during a mosquito blood meal (41). There are several encouraging examples of paratransgenesis used to combat different pathogens in either an insect host or in mammalian cells (2, 4, 11, 40).

The candidate species for malaria paratransgenesis presented here is Pantoea (= Enterobacter) agglomerans, a Gram-negative gammaproteobacterium (14). This isolate originated from adult blood-fed female Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes and has been selected for longer survival periods in the gut environment (42). Other P. agglomerans strains have been isolated from plant matter as well as from different insect species (1, 10, 27, 28). The P. agglomerans strain E325 has been used in orchards to combat fire blight through a competitive displacement strategy (38). For these reasons, in addition to malaria, P. agglomerans may prove to be a paratransgenic tool in the fight against other diseases (38, 43).

Many antimalarial effector proteins are known to interfere with the development of the parasite in mosquito midguts. For this study, we tested three structurally diverse effectors for their ability to be secreted via the pelB or hlyA protein secretion pathways from P. agglomerans. The effector proteins included the dodecapeptide SM1 (salivary and midgut peptide 1), an anti-Pbs21 single-chain variable-fragment (scFv) antibody, and phospholipase A2 (PLA2). SM1 (8 kDa) is structurally similar to an epitope of the Plasmodium TRAP protein, a target used by the parasite to invade mosquito salivary glands and midgut epithelium (16, 17). Anti-Pbs21 scFv (21 kDa) binds to a sexual-stage surface protein of Plasmodium berghei and has been shown to block oocyst development from gametocytes and ookinetes in the mosquito midgut (54). PLA2 (23 kDa) is believed to intercalate in the mosquito midgut lining, preventing Plasmodium from migrating to the salivary glands (35). In earlier studies, Escherichia coli expressed and/or surface displayed these effector proteins inside the mosquito gut, but E. coli is not able to survive for long periods of time in the gut environment (53), thus the need to move to a species like P. agglomerans, which normally inhabits mosquito midguts (42, 53).

For a paratransgenic P. agglomerans strain to be most effective against Plasmodium, the effector proteins should be secreted within the mosquito gut environment, where Plasmodium undergoes the critical sexual stage of its life cycle (15). We report here the successful test of two distinct bacterial secretion pathways to deliver three structurally distinct antimalarial effector proteins in the paratransgenesis candidate species P. agglomerans. Importantly, strains that secreted effectors efficiently grew as well as wild-type strains under laboratory conditions, suggesting that they may be competitive with natural microbiota in the midgut environment of the mosquito.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media.

Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani broth or agar (LB). S. cerevisiae cells were grown on yeast extract-peptone-dextrase (YPD) agar or minimal drop-out media excluding uracil (2% glucose) when selecting for yeast recombinants. Antibiotic concentrations were as follows: ampicillin (Amp), 150 μg/ml; apramycin (Apr), 80 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Chl), 30 μg/ml; gentamicin (Gen), 10 μg/ml; nalidixic acid (Nal), 30 μg/ml; rifampin (Rif), 30 μg/ml; streptomycin sulfate (Str), 100 μg/ml; tetracycline (Tc), 15 μg/ml.

Plasmid construction.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. With the exception of pDB36 and the hlyA plasmid group, plasmids were constructed using a yeast gap repair method (47). Inserts were amplified using primers that added 40 bp of homology to the vector cut site. Vector (∼20 to 200 ng) and inserts (50 to 500 ng) were cotransformed into S. cerevisiae INVSc-1 (Invitrogen). Total DNA from transformed yeast cells that grew on uracil drop-out medium was purified using the “yeast smash and grab DNA miniprep” protocol (44). Fifty nanograms of total yeast DNA was transformed into E. coli, and restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing verified resultant clones.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| E. coli Top10 F′ | Top10 with F′[lacIq Tn10 (Tcr)] | Invitrogen |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae INVSc-1 | Sc1; MATahis3D1leu2 trp1-289 ura3-52 MATα his3D1 leu2 trp1-289 ura3-52 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli BW25113 | lacIqrrnBΔlacZ hsdR514ΔaraBADΔrhaBAD | 9 |

| E. coli ET12567 | dam-13::Tn9 dcm-6 hsdM hsdR recF143 zjj201::Tn10 galK2 galT22 ara-14 lacY1 xyl-5 leuB6 thi-1 tonA31 rpsL136 hisG4 tsx-78 mtl-1 glnV44 F− | 30 |

| E. coli LL308 | Δ(pro-lac) recA nalA supE thi/′F pro+lacIqlacZΔM15 | 55 |

| E. coli HB2151 | Δlac-pro ara Nalrthi F′ (proAB lacIqlacZΔM15) | 51 |

| P. agglomerans | Wild-type strain isolated from Johns Hopkins University mosquitoes | 42 |

| P. agglomerans E325 | Commercial strain isolated from plant matter; Rifr | 38 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ790 | Camr; λ red (gambetexo) araC rep101(Ts) | 18 |

| pIJ799 | Aprr; source of aac(3)IV-oriT cassette flanked by bla homology sites | 18 |

| pUZ8002 | Kanr; RK2 derivative, nontransmissible plasmid in E. coli | 37 |

| pMQ64 | Genr; yeast recombination vector containing colE1 ori | 47 |

| pDB27 | Camr; source of malE-anti-BSA scFv | D. C. Bisi, unpublished |

| pHA-2-5-1 | Source of SM1 effector gene (encodes two tandem copies) | 17 |

| pDL200.3 | Source of anti-Pbs21 effector gene | D. J. Lampe, unpublished |

| pTOPO-PLA2-H67N | Source of PLA2 effector gene (H67N mutant) | 35 |

| PelB | ||

| pIT2-scFv | Ampr; pIT2 with anti-BSA scFv incorporated between pelB and epitope tags | 51 |

| pDB36 | Aprr; pIT2-scFv with bla gene replaced with aac(3)IV | This study |

| pDB48 | Genr; pelB-AscI-6His-myc-STOP cloned into MCS in pMQ64 | This study |

| pDB52 | Genr; pDB48/SM1 | This study |

| pDB53 | Genr; pDB48/anti-Pbs21 | This study |

| pDB54 | Genr; pDB48/PLA2 | This study |

| HlyA | ||

| pVDL9.3 | Camr; production of HlyB and HlyD transporters | 50 |

| pEHLYA2-SD | Ampr; polylinker for cloning ORFs in frame with E-tagged ′hlyA (23-kDa C-terminal domain of HlyA) | 13 |

| pDB47 | Aprr; pEHLYA2-SD with bla gene replaced with aac(3)IV | This study |

| pDB49 | Aprr; pDB47/anti-BSA scFv | This study |

| pDB50 | Aprr; pDB47malE-anti-BSA scFv | This study |

| pDB58 | Aprr; pDB47/SM1 | This study |

| pDB59 | Aprr; pDB47/anti-Pbs21 | This study |

| pDB60 | Aprr; pDB47/PLA2 | This study |

Ampr, ampicillin resistant; Aprr, apramycin resistant; Camr, chloramphenicol resistant; Genr, gentamicin resistant; Nalr, nalidixic acid resistant; Rifr, rifampin resistant; Strr, streptomycin resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant.

pelB plasmid construction.

Because P. agglomerans is naturally ampicillin resistant, the bla gene in pIT2-scFv was replaced with the aac(3)IV gene using “recombineering” (18) techniques, resulting in pDB36, which is apramycin resistant (9, 18). Briefly, E. coli BW25113 cells containing pIJ790 and pIT2-scFv were collected at log phase and electroporated with 500 ng of the aac(3)IV-oriT cassette from pIJ799. After amplification in LB, aliquots were plated on LB agar containing apramycin and incubated overnight at 30°C.

To eliminate pIT2-scFv (Ampr) background, a subsequent conjugation transferred pDB36 into E. coli LL308 (37). BW25113(pDB36) plasmid DNA was used to transform the donor strain E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002). Overnight cultures of ET12567(pUZ8002) and LL308 were diluted (1:100) and incubated until they reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 to 0.5 (1 to 2 h). Aliquots (500 μl) of each strain were resuspended in fresh LB, combined, and incubated for 20 min at 37°C with aeration. The aeration speed was increased, and the incubation continued for an additional 1 h. Aliquots were plated on LB agar containing nalidixic acid and apramycin, and the resulting colonies were grown in LB broth containing apramycin or ampicillin to ensure loss of the pIT2-scFv plasmid.

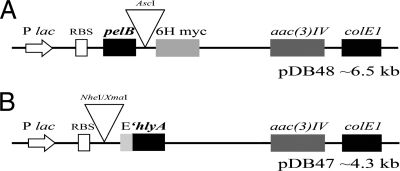

To make the pelB secretion construct pDB48 (Fig. 1 A), pMQ64 was digested with HindIII and the entire multiple-cloning site (MCS) was replaced with pelB-AscI-6His-myc-STOP by yeast gap repair (47). The two inserts, pelB (PelB, MKYLLPTAAAGLLLLAAQPA) and the epitope tags, were amplified from pIT2-scFv with 60-mer oligonucleotides containing 40 bp of homology to the pMQ64 site of insertion (20 bp used to amplify pelB: forward, 5′ATGAAATACCTATTGCCTAC; reverse, 5′GGCCGGCTGGGCCGCGAGTAATAAC). The forward primer for the epitope tags contained the AscI sequence. pDB52 through pDB54 were made by cloning each effector gene (those for SM1, anti-Pbs21 scFv, and PLA2, respectively) into pDB48/AscI using yeast gap repair.

Fig. 1.

PelB and HlyA secretion constructs used in this study. (A) pDB48 contains the pelB signal and 6His and myc epitope tags (6H myc). (B) pDB47 contains the 3′ end of E. coli hemolysin A (′hlyA) and the E-tag epitope (E). pDB47 is coexpressed with pVDL9.3, which provides the membrane proteins HlyB and HlyD. Both plasmids carry the colE1 origin of replication and aac(3)IV as a drug marker (apramycin resistance). RBS, ribosome binding site.

hlyA plasmid construction.

Replacing the bla gene in pEHLYA2-SD with aac(3)IV resulted in the hlyA secretion construct pDB47 (Fig. 1B) (13). This was done using recombineering and a conjugation as described for pDB36.

To make pDB49, pDB50, and pDB58-60, the vector pDB47 was digested with NheI/XmaI and treated with calf intestinal phosphatase according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England BioLabs). The inserts (anti-bovine serum albumin [BSA] scFv, malE-anti-BSA scFv, SM1, anti-Pbs21 scFv, and PLA2) were amplified from the corresponding pelB-effector construct (or in the case of malE-anti-BSA scFv, from pDB27) to include the 6His and myc epitopes with 20-mer oligonucleotides that incorporated NheI and XmaI recognition sites on the 5′ and 3′ ends of the amplicons, respectively. Ligation reaction mixtures containing ∼150 ng of vector, various amounts of NheI/XmaI-digested insert (∼300 to 800 ng), and T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs) were incubated overnight at 16°C, followed by electrotransformation into Top10 E. coli cells.

Secretion of recombinant proteins from P. agglomerans and E. coli.

Individual colonies were used to inoculate 5 ml of LB broth containing antibiotics and 1% glucose (glucose is needed only for E. coli HB2151, as P. agglomerans is Lac−) and grown at 30°C overnight (12 to 16 h). The next day, a 5-ml culture containing antibiotics and glucose was inoculated with 50 μl of the overnight culture and grown to an OD600 of 0.5. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 5 ml of LB containing 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and incubated at 30°C overnight (12 to 16 h). Constructs in P. agglomerans are expressed constitutively since LacI is absent.

Cells were collected from 100 μl of an overnight culture of E. coli HB2151 or P. agglomerans. The resultant supernatant (75 μl) was combined with 25 μl of 3× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad). The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 3× Laemmli buffer. Samples were boiled for 10 min and analyzed by 10% (vol/vol) SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using standard Western blot procedures. PVDF membranes were washed in TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) and blocked with 1% (wt/vol) BSA for 3 h at room temperature. After incubating overnight with an anti-myc antibody (1 μg/ml or 1:10,000; Invitrogen 46-0603) at 4°C, the membranes were washed in TBST (four 15-min washes) and incubated in horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (0.01 μg/100 ml or 1:100,000; Pierce 1858413) for 1 h at room temperature. The washing steps were repeated, and the bound antibody-HRP conjugate was detected using chemiluminescence (Pierce) and autoradiographic film.

ELISAs using spent growth medium from induced E. coli or P. agglomerans.

The activity of the secreted anti-BSA scFv was tested using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For each sample analyzed, duplicate MaxiSorp wells (Nunc) were coated with 100 μl of BSA (2 mg/ml) along with two negative-control wells (100 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] and one empty well) and stored overnight at 4°C (ca. 12 h). Each well was washed three times with 200 μl of 1× PBS and blocked for 2 h at room temperature with 2% dry milk in 1× PBS. The washes were repeated, and 100 μl of clarified spent growth medium from an induced overnight culture was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After eight washes of each well with 200 μl of 1× PBS-0.1% Tween 20, the HRP-conjugated anti-myc antibody (1:2,000 diluted in blocking buffer; Roche 11-814-15-0001) was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The eight washes were repeated, and the antibody was detected using 50 μl/well of the chromogenic substrate 1-Step Ultra TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine; Pierce). When a sufficient signal was reached, the reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 2 M H2SO4 and the A450 with the background subtracted at 650 nm was determined with a Bio-Rad 3550 plate reader.

Measurement of growth rates of P. agglomerans wild-type and secretion strains.

For P. agglomerans strains that expressed recombinant proteins, duplicate cultures for each strain were grown as described above. The optical density (600 nm) for each culture was determined spectrophotometrically at hourly intervals (with the exception of the readings at 2 h and 4 h). Growth curves were plotted using the average of the duplicate value without transformation of the data (8). The slope of each sequential pair of time points along each curve was calculated to determine the maximum growth rate. The maximum growth rate (corresponding to the maximum hourly slope along the entire growth curve) of each line was used to compare the different strains. Once the maximum growth rate was found, the standard error of that slope was also calculated (3). All statistical values were generated using the linear regression function of the SPSS statistical package (IBM, Inc.).

RESULTS

Secretion constructs.

A schematic of the pelB anti-Plasmodium effector construct pDB48 is shown in Fig. 1A. Effector genes were recombined into the unique AscI site that sits between the PelB signal and epitope tags. Yeast recombination was used to ensure that each construct was identical, with the exception of the effector gene open reading frame (ORF). The IPTG-inducible lac promoter drives expression of the ORF. In the case of P. agglomerans, IPTG is not needed to induce expression because this species is Lac− and does not produce the LacI protein. Therefore, in this species effector proteins are constitutively expressed. pDB48 replicates using the narrow-host-range colE1 origin and confers resistance to apramycin [aac(3)IV].

The HlyA anti-Plasmodium effector construct pDB47 is shown in Fig. 1B. Effector genes, tagged with 6His and myc at the C terminus, were cloned by restriction digestion (NheI/XmaI) between the lac promoter and the 3′ end of hlyA (′hlyA). An E-tag epitope was included for immunodetection purposes. As with pDB48, pDB47 replicates using the colE1 origin and was modified from its parent plasmid to confer resistance to apramycin. It must be coexpressed with pVDL9.3, which provides the membrane channel hemolysin proteins HlyB and HlyD.

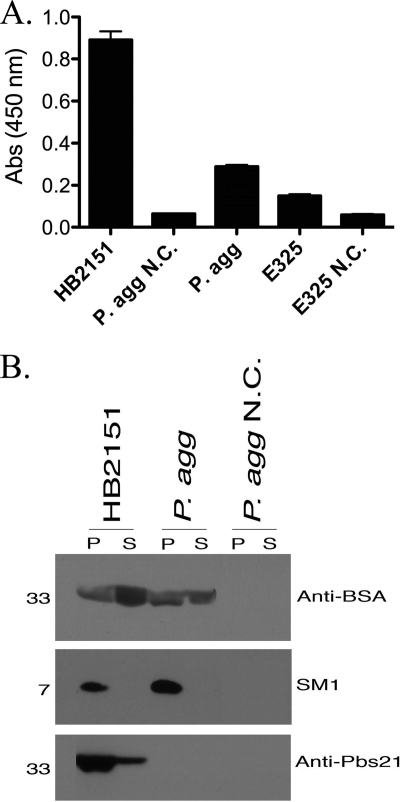

Expression and secretion using the PelB leader.

The PelB leader allowed for secretion of an active anti-BSA scFv from P. agglomerans and E. coli (HB2151) expressing pDB36 as shown by Western blot analysis and an ELISA (Fig. 2 A and B). The P. agglomerans E325 strain expressing pDB36 also secreted an active anti-BSA scFv (Fig. 2A). The results were mixed for the three anti-Plasmodium effectors tested (Fig. 2B). The anti-Pbs21 scFv was expressed and secreted only by E. coli. SM1 was expressed by both species but was not secreted. Finally, PLA2 was neither expressed nor secreted by either species. These data are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Secretion of proteins using the PelB leader. (A) Graphical representation of ELISA results for strains expressing anti-BSA scFv (DB36). (B) Western blotting for detection of anti-Plasmodium effector proteins in the cell pellet (P) or spent growth medium supernatant (S). HB2151, E. coli; P. agg, P. agglomerans; E325, P. agglomerans commercial strain; N.C., negative control.

Table 2.

Summary of expression and secretion results using all signals and effector proteins in E. coli and P. agglomerans

| Organism | Protein | Resulta for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PelB |

HlyA |

||||

| Exp. | Secr. | Exp. | Secr. | ||

| E. coli | Anti-BSA | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| P. agglomerans | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| E. coli | SM1 | Y | N | N | N |

| P. agglomerans | Y | N | N | N | |

| E. coli | Anti-Pbs21 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| P. agglomerans | N | N | Y | Y | |

| E. coli | PLA2 | N | N | Y | Y |

| P. agglomerans | N | N | Y | Y | |

Exp., expression of the protein as visualized by Western blotting; Secr., secretion of the protein as visualized by Western blotting; Y, yes; N, no.

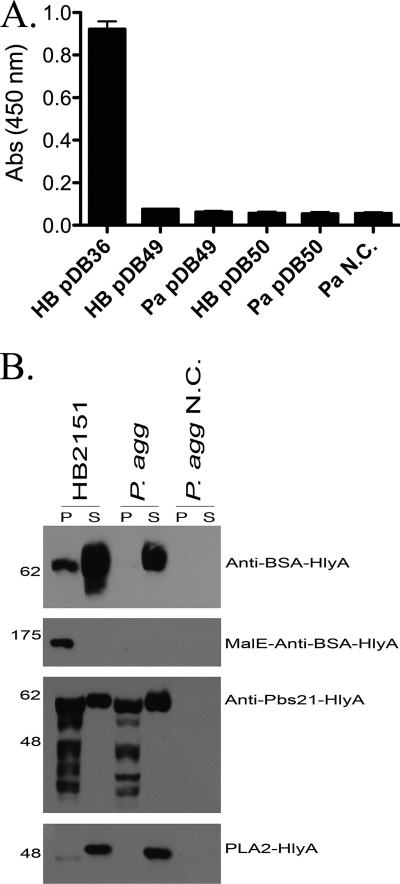

Expression and secretion using the C terminus of HlyA.

The anti-BSA scFv-HlyA fusion protein was expressed in both P. agglomerans and E. coli. Both species secreted the protein at high levels; however, neither antibody was active in an ELISA compared to anti-BSA scFv antibodies secreted by E. coli expressing the pelB construct, pDB36 (Fig. 3 A). A maltose binding protein-anti-BSA scFv fusion was made (pDB50) in order to promote stability and folding of the scFv, but this fusion protein was expressed only in E. coli and was not secreted from either species (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Secretion of HlyA fusion proteins. (A) Graphical representation of ELISA results for strains expressing anti-BSA scFv-HlyA (DB49) or MalE-anti-BSA scFv-HlyA (DB50). E. coli expressing anti-BSA scFv is included as a positive control (HB DB36). (B) Western blotting for detection of anti-Plasmodium effector proteins in the cell pellet (P) or spent growth medium supernatant (S) collected from E. coli HB2151 or P. agglomerans (P. agg). N.C., negative control.

The HlyA-mediated secretion results for the anti-Plasmodium effectors are shown in Fig. 3B. The anti-Pbs21 scFv and PLA2 were both expressed and secreted at high levels in P. agglomerans and E. coli; however, the SM1-HlyA fusion protein was not expressed or secreted by either species. Generally speaking, the HlyA system was very efficient at mediating secretion when the proteins were expressed, except for the extremely large MBP-scFv fusion (ca. 175 kDa) (Table 2).

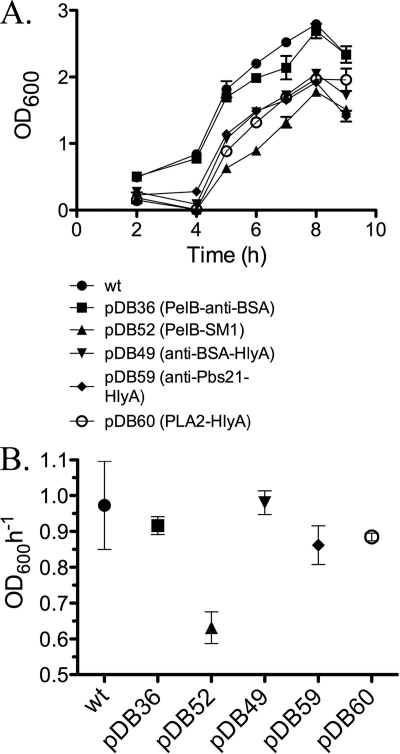

Growth rates of strains expressing recombinant proteins from P. agglomerans.

Since we propose to use P. agglomerans in a paratransgenic strategy, we attempted to assess how fit the strains were that were expressing and/or secreting recombinant protein. If the strains were impaired in terms of fitness (as measured by maximum growth rate in culture) then their utility as paratransgenic strains is in question. Bacteria in culture follow a complex growth pattern, typically consisting of lag, log, and stationary growth phases. We chose to focus on maximum growth rate as one measure of fitness that is relevant for paratransgenic strains, since there is rapid bacterial growth in the midgut of female mosquitoes following a blood meal (42). There was a strong correlation between maximum growth rate and the ability of a recombinant protein to be secreted from P. agglomerans (Fig. 4). In every case, when a protein was translated and secreted, the maximum growth rate of the strain was similar to that of the wild-type strain. The strain that had the slowest maximum growth rate (PelB-SM1 in P. agglomerans) did not secrete at all. This result suggests that accumulation of recombinant protein in the cytoplasm is toxic and that efficient secretion relieves this toxic effect, allowing the strain to grow with kinetics similar to that of wild-type P. agglomerans.

Fig. 4.

Growth curves and calculated maximum growth rates of P. agglomerans strains expressing recombinant proteins. (A) Growth kinetics of strains that expressed and/or secreted recombinant proteins. (B) Maximum growth rates calculated from growth curves in panel A. Each strain showed a maximum growth rate between 4 and 5 h of growth in culture. Results for wild-type P. agglomerans (wt) are shown for comparison. Error bars indicate the standard error of the estimated maximum growth rate.

DISCUSSION

There is widespread recognition of the fact that successful control and eventual eradication of malaria will require the development of multiple complementary control strategies to supplement the time-tested methods of vector control and drug treatment of infected people (6, 39, 49). We report here the development of strains of P. agglomerans that secrete known antimalarial effector proteins and a separate test protein that may be suitable in a strategy to block parasite development in the mosquito gut.

The anti-BSA scFv was successfully secreted from P. agglomerans using the PelB leader. This antibody is used in our laboratory as an initial test for secretion because the activity of the secreted antibody can easily be assessed in an ELISA using clarified supernatant from an overnight culture expressing the plasmid. Proof of a secreted and active scFv is encouraging for downstream secretion tests with anti-Plasmodium scFvs. The scFv is an attractive antibody form because these proteins are relatively small (∼25 kDa) and stable and can be expressed from a single gene (33).

We hypothesized that the anti-Plasmodium effector proteins (SM1, anti-Pbs21 scFv, PLA2) would behave similarly to the anti-BSA scFv under the PelB signal. Previously, each of these effectors was expressed and/or surface displayed by E. coli while inside the mosquito gut (42, 53). Thus, we hypothesized that P. agglomerans and E. coli could express the SM1, anti-Pbs21 scFv, and PLA2 proteins without difficulty. However, the results showed that not all of these proteins were expressed and/or secreted by either species.

SM1 was expressed by both species but not detected in the spent growth medium. Only E. coli was able to secrete the anti-Pbs21 scFv. This was an unexpected result, because this protein is an scFv similar to the anti-BSA scFv, which was secreted by P. agglomerans without any difficulty. It is also curious that PLA2 was not expressed by either species, as previous studies showed expression of this protein in E. coli without incident (42). Unpublished data indicate that completely resynthesizing the PLA2 gene to codon optimize the sequence for expression in bacteria alleviates this failure of expression (M. Jacobs-Lorena and S. Wang, personal communication).

PelB directs secretion in a type II fashion, which involves passage through the periplasm before export via the Sec translocation machinery in the outer membrane (45). Proteins are folded into their final conformation, and the PelB leader is removed in the periplasm (5). Problems in the periplasm may have been encountered, such as periplasmic inclusion bodies, errors in folding or disulfide bond formation, or degradation (24, 46). Any of these problems could explain why SM1 was detected in the cell pellet and not in the supernatant and why the anti-Pbs21 scFv was not detected in P. agglomerans.

Within the oxidizing environment of the periplasm, disulfide bond formation is carried out by the Dsb (disulfide bond formation) family of proteins (36). Considerable success has been achieved with the coexpression of Dsb proteins and recombinant proteins (23, 26, 52). There are also periplasmic chaperone proteins that can facilitate proper folding of the secreted protein. For example, seventeen-kilodalton protein (Skp) has been coexpressed and shown to improve the production, yield, and activity of scFvs (20, 32). Mavrangelos et al. (32) also employed an alternate Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of the scFv gene that resulted in tighter ribosome binding and enhanced expression.

As with all of these modifiers, the optimal combination for each recombinant protein has to be determined empirically.

In comparison, the C-terminal HlyA signal results in type I secretion, where proteins are exported from the cell in one step across both cell membranes. Although the anti-BSA scFv test protein fused to the HlyA signal was secreted in high levels in both species, neither was active in an ELISA (Fig. 3). It may be that fusion to the 30-kDa HlyA signal abolished function of the scFv or caused misfolding of the scFv. It may also be that secretion via the periplasm (where essential disulfide bonds in the structure of an scFv can be formed) is a requirement for activity, although there is one report in the literature of secretion of a functional scFv fused to the HlyA C terminus (13).

Regardless, HlyA was the most successful signal in terms of delivery of anti-Plasmodium effector proteins to the extracellular space and in terms of the number of different proteins that it was capable of secreting. Most importantly, both the anti-Pbs21 scFv and PLA2 were expressed and secreted as HlyA fusions by P. agglomerans (Fig. 3B). The testing of these strains for their inhibition of Plasmodium development is under way and, in preliminary experiments, has been found to significantly reduce the number of parasites that are able to develop when mosquitoes take an infective blood meal, indicating that functionality is retained (unpublished results). As with the PelB signal, SM1-HlyA was not detected in the spent growth medium. As additional antimalarial effector proteins are developed, it may be that those that do not require disulfide bond formation could be secreted by the type I pathway (e.g., antimalarial peptides) while effectors with disulfide bonds would necessarily be secreted via the PelB-mediated type II system.

Finally, we note that there was a strong correlation between maximum growth rate of the P. agglomerans secretion strains and the relative success in secreting the effector proteins. The fact that strains that successfully secrete effectors grow similarly to wild-type strains is important for the overall success of any paratransgenic antimalarial strategy, since the recombinant strains must compete with bacteria already present in the gut of the mosquito, where bacterial growth is extremely rapid after the intake of an Plasmodium-infected blood meal (42).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank J. McCormick for technical advice in performing the recombineering experiments needed to produce the pDB36 and pDB47 plasmids. We also thank P. Pusey for the gift of P. agglomerans strain E325 and M. Jacobs-Lorena for sharing the plasmids that encode SM1, PLA2, and the anti-Pbs21 scFv. We thank M. Jacobs-Lorena and S. Wang for allowing us to cite unpublished data. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments.

This work was supported by grants from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Universal Research Enhancement program and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrews J. H., Harris R. F. 2000. The ecology and biogeography of microorganisms on plant surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38: 145–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beard C. B., et al. 2001. Bacterial symbiosis and paratransgenic control of vector-borne Chagas disease. Int. J. Parasitol. 31: 621–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breidt F., Romick T. L., Fleming H. P. 1994. A rapid method for the determination of bacterial growth kinetics. J. Rapid Methods Autom. Microbiol. 3: 59–68 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang T. L., et al. 2003. Inhibition of HIV infectivity by a natural human isolate of Lactobacillus jensenii engineered to express functional two-domain CD4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100: 11672–11677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi J. H., Lee S. Y. 2004. Secretory and extracellular production of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64: 625–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corbel V., Henry M. C. 2011. Prevention and control of malaria and sleeping sickness in Africa: where are we and where are we going? Parasit. Vectors 4: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coutinho-Abreu I. V., Zhu K. Y., Ramalho-Ortigao M. 2010. Transgenesis and paratransgenesis to control insect-borne diseases: current status and future challenges. Parasitol. Int. 59: 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalgaard P., Koutsoumanis K. 2001. Comparison of maximum specific growth rates and lag times estimated from absorbance and viable count data by different mathematical models. J. Microbiol. Methods 43: 183–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97: 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dillon R., Charnley K. 2002. Mutualism between the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria and its gut microbiota. Res. Microbiol. 153: 503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Durvasula R. V., et al. 1997. Prevention of insect-borne disease: an approach using transgenic symbiotic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94: 3274–3278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feachem R. G., et al. 2010. Shrinking the malaria map: progress and prospects. Lancet 376: 1566–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fernandez L. A., Sola I., Enjuanes L., de Lorenzo V. 2000. Specific secretion of active single-chain Fv antibodies into the supernatants of Escherichia coli cultures by use of the hemolysin system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66: 5024–5029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gavini F., et al. 1989. Transfer of Enterobacter agglomerans (Beijerinck 1888) Ewing and Fife 1972 to Pantoea gen. nov. as Pantoea agglomerans comb. nov. and description of Pantoea dispersa sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39: 337–345 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghosh A., Edwards M. J., Jacobs-Lorena M. 2000. The journey of the malaria parasite in the mosquito: hopes for the new century. Parasitol. Today 16: 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghosh A. K., et al. 2009. Malaria parasite invasion of the mosquito salivary gland requires interaction between the Plasmodium TRAP and the anopheles saglin proteins. PLoS Pathog. 5: e1000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghosh A. K., Ribolla P. E., Jacobs-Lorena M. 2001. Targeting Plasmodium ligands on mosquito salivary glands and midgut with a phage display peptide library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98: 13278–13281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gust B., et al. 2004. Lambda red-mediated genetic manipulation of antibiotic-producing Streptomyces. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 54: 107–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hay S. I., Guerra C. A., Tatem A. J., Atkinson P. M., Snow R. W. 2005. Urbanization, malaria transmission and disease burden in Africa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3: 81–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayhurst A., Harris W. J. 1999. Escherichia coli skp chaperone coexpression improves solubility and phage display of single-chain antibody fragments. Protein Expr. Purif. 15: 336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoy M. A. 2000. Transgenic arthropods for pest management programs: risks and realities. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 24: 463–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito J., Ghosh A., Moreira L. A., Wimmer E. A., Jacobs-Lorena M. 2002. Transgenic anopheline mosquitoes impaired in transmission of a malaria parasite. Nature 417: 452–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joly J. C., Leung W. S., Swartz J. R. 1998. Overexpression of Escherichia coli oxidoreductases increases recombinant insulin-like growth factor-I accumulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95: 2773–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kolaj O., Spada S., Robin S., Wall J. G. 2009. Use of folding modulators to improve heterologous protein production in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Fact. 8: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lambrechts L., Koella J. C., Boete C. 2008. Can transgenic mosquitoes afford the fitness cost? Trends Parasitol. 24: 4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee D. H., Kim M. D., Lee W. H., Kweon D. H., Seo J. H. 2004. Consortium of fold-catalyzing proteins increases soluble expression of cyclohexanone monooxygenase in recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 63: 549–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindow S. E., Brandl M. T. 2003. Microbiology of the phyllosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69: 1875–1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Loncaric I., et al. 2009. Typing of Pantoea agglomerans isolated from colonies of honey bees (Apis mellifera) and culturability of selected strains from honey. Apidologie 40: 40–54 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez C., Saravia C., Gomez A., Hoebeke J., Patarroyo M. A. 2010. Mechanisms of genetically-based resistance to malaria. Gene 467: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MacNeil D. J., et al. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111: 61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marshall J. M., Taylor C. E. 2009. Malaria control with transgenic mosquitoes. PLoS Med. 6: e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mavrangelos C., et al. 2001. Increased yield and activity of soluble single-chain antibody fragments by combining high-level expression and the Skp periplasmic chaperonin. Protein Expr. Purif. 23: 289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maynard J., Georgiou G. 2000. Antibody engineering. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2: 339–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Menge D. M., et al. 2005. Fitness consequences of Anopheles gambiae population hybridization. Malar. J. 4: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moreira L. A., et al. 2002. Bee venom phospholipase inhibits malaria parasite development in transgenic mosquitoes. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 40839–40843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakamoto H., Bardwell J. C. 2004. Catalysis of disulfide bond formation and isomerization in the Escherichia coli periplasm. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694: 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paget M. S., Chamberlin L., Atrih A., Foster S. J., Buttner M. J. 1999. Evidence that the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor sigmaE is required for normal cell wall structure in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 181: 204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pusey P. L. 2002. Biological control agents for fire blight of apple compared under conditions limiting natural dispersal. Plant Dis. 86: 639–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raghavendra K., Barik T. K., Reddy B. P., Sharma P., Dash A. P. 2011. Malaria vector control: from past to future. Parasitol. Res. 108: 757–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rao S., et al. 2005. Toward a live microbial microbicide for HIV: commensal bacteria secreting an HIV fusion inhibitor peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 11993–11998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Riehle M. A., Jacobs-Lorena M. 2005. Using bacteria to express and display anti-parasite molecules in mosquitoes: current and future strategies. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35: 699–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Riehle M. A., Moreira C. K., Lampe D., Lauzon C., Jacobs-Lorena M. 2007. Using bacteria to express and display anti-Plasmodium molecules in the mosquito midgut. Int. J. Parasitol. 37: 595–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rio R. V., Hu Y., Aksoy S. 2004. Strategies of the home-team: symbioses exploited for vector-borne disease control. Trends Microbiol. 12: 325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rose M. D., Winston F., Hieter P. 1990. Methods in yeast genetics: a laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sandkvist M. 2001. Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40: 271–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schlapschy M., Grimm S., Skerra A. 2006. A system for concomitant overexpression of four periplasmic folding catalysts to improve secretory protein production in Escherichia coli. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19: 385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shanks R. M., Caiazza N. C., Hinsa S. M., Toutain C. M., O'Toole G. A. 2006. Saccharomyces cervisiae-based molecular tool kit for manipulation of genes from gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 5027–5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Snow R. W., Guerra C. A., Noor A. M., Myint H. Y., Hay S. I. 2005. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 434: 214–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Takken W., Knols B. G. 2009. Malaria vector control: current and future strategies. Trends Parasitol. 25: 101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tzschaschel B. D., Guzman C. A., Timmis K. N., de Lorenzo V. 1996. An Escherichia coli hemolysin transport system-based vector for the export of polypeptides: export of Shiga-like toxin IIeB subunit by Salmonella typhimurium aroA. Nat. Biotechnol. 14: 765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Winter G., Griffiths A. D., Hawkins R. E., Hoogenboom H. R. 1994. Making antibodies by phage display technology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12: 433–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wulfing C., Rappuoli R. 1997. Efficient production of heat-labile enterotoxin mutant proteins by overexpression of dsbA in a degP-deficient Escherichia coli strain. Arch. Microbiol. 167: 280–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yoshida S., Ioka D., Matsuoka H., Endo H., Ishii A. 2001. Bacteria expressing single-chain immunotoxin inhibit malaria parasite development in mosquitoes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 113: 89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yoshida S., et al. 1999. A single-chain antibody fragment specific for the Plasmodium berghei ookinete protein Pbs21 confers transmission blockade in the mosquito midgut. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 104: 195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zengel J. M., Mueckl D., Lindahl L. 1980. Protein L4 of the E. coli ribosome regulates an eleven gene r protein operon. Cell 21: 523–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]