Abstract

Protein myristoylation is a means by which cells anchor proteins into membranes. The most common type of myristoylation occurs at an N-terminal glycine. However, myristoylation rarely occurs at an internal amino acid residue. Here we tested whether the α-subunit of the human large-conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel (hSlo1) might undergo internal myristoylation. hSlo1 expressed in HEK293T cells incorporated [3H]myristic acid via a posttranslational mechanism, which is insensitive to cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein biosynthesis. In-gel hydrolysis of [3H]myristoyl-hSlo1 with alkaline NH2OH (which cleaves hydroxyesters) but not neutral NH2OH (which cleaves thioesters) completely removed [3H]myristate from hSlo1, suggesting the involvement of a hydroxyester bond between hSlo1’s hydroxyl-bearing serine, threonine, and/or tyrosine residues and myristic acid; this type of esterification was further confirmed by its resistance to alkaline Tris·HCl. Treatment of cells expressing hSlo1 with 100 μM myristic acid caused alteration of hSlo1 activation kinetics and a 40% decrease in hSlo1 current density from 20 to 12 nA*MΩ. Immunocytochemistry confirmed a decrease in hSlo1 plasmalemma localization by myristic acid. Replacement of the six serines or the seven threonines (but not of the single tyrosine) of hSlo1 intracellular loops 1 and 3 with alanines decreased hSlo1 direct myristoylation by 40–44%, whereas in combination decreased myristoylation by nearly 90% and abolished the myristic acid-induced change in current density. Our data demonstrate that an ion channel, hSlo1, is internally and posttranslationally myristoylated. Myristoylation occurs mainly at hSlo1 intracellular loop 1 or 3, and is an additional mechanism for channel surface expression regulation.

Keywords: MaxiK channel, BKCa channel, posttranslational modification, traffic

The large-conductance voltage- and calcium-activated potassium channel (MaxiK, BKCa) is ubiquitously expressed regulating numerous physiological functions such as neuronal action potential firing, neurotransmitter release, and vascular smooth muscle tone (1). Four pore-forming α-subunits (Slo1, an ∼125-kDa protein) make a functional MaxiK channel. Based on structure/function studies, Slo1 protein can be separated into two main functional cassettes: the multipass transmembranous N terminus (∼40 kDa) and a large cytoplasmic C terminus (∼85 kDa). The N terminus has seven (S0–S6) transmembrane segments, together forming the voltage-sensing and the pore-conducting domains. The intracellular C terminus carries two RCK domains (RCK1, RCK2) and contains the Ca2+-sensing module as well as other amino acid residues forming docking sites for protein–protein interactions with associating partners. In addition, the C-terminal domain carries consensus sites for modulation by protein kinases or endogenous signaling molecules (2, 3). Despite the multifactorial nature of Slo1 functional regulation, the possible modification of Slo1 by the saturated intracellular lipid myristic acid has not been directly addressed.

Covalent linkage of myristic acid to proteins is prevalent at N-terminal glycine residues via an amide bond. N-terminal myristoylation is irreversible, hydroxylamine-resistant, and requires the recognition sequence G-{EDRKHPFYW}-x(2)-[STAGCN]-{P} [where G is the N-myristoylation site; Prosite no. PS00008 (http://expasy.org/prosite/); cf. ref. 4]. N-terminal (glycine) myristoylation can be either cotranslational (more common) or posttranslational (rare). The former follows cotranslational removal of the initiating methionine exposing glycine at position 2, whereas the latter involves unmasking the internal consensus recognition sequence as a result of protein proteolysis (5, 6). The role of N-terminal myristoylation is to regulate among other things protein function and protein anchoring to the internal leaflet of the plasma membrane (5). A much less studied and less frequent type of myristoylation takes place at internal amino acid residues via ester or amide bonds (7–10); it has been estimated that 0.09–0.24% of total cell protein binds to myristate using this mechanism (11). Internal myristoylation has been reported for a few mammalian proteins such as the β-subunit of the insulin receptor, the precursor of interleukin 1α, and tumor necrosis factor α (8–10). This type of myristoylation occurs preferentially in a posttranslational fashion and may involve amide, thioester, or hydroxyester chemical bonds, which can be identified based on the sensitivity of the attached myristic acid to hydroxylamine treatment (12). The role of internal myristoylation is largely unknown. Here we show that human Slo1 (hSlo1) undergoes internal myristoylation by directly incorporating myristic acid in a posttranslational fashion to serine and threonine residues located in its intracellular loop 1 or 3, and that this process correlates with myristic acid-induced modulation of hSlo1 surface expression.

Results

hSlo1 Directly Incorporates Radiolabeled Myristic Acid.

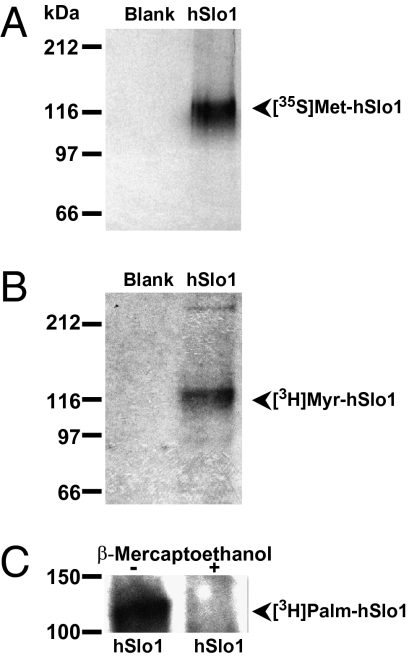

To address the possible direct myristoylation of Slo1 protein, HEK293T cells transiently expressing hSlo1 were metabolically radiolabeled with [3H]myristic acid or [35S]methionine (to confirm hSlo1 protein expression) followed by immunoprecipitation and autofluorography. As shown in Fig. 1A, a band at the expected size of ∼125 kDa was immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Myc antibody (Ab) recognizing the c-Myc-tagged 35S-labeled hSlo1. As negative control, the signal was absent in untransfected cells (blank). A band of the same molecular mass as the one radiolabeled with [35S]methionine incorporates [3H]myristic acid (Fig. 1B, lane 2) (n = 7). Because cells can metabolize myristic acid into palmitic acid (11), we sought to determine whether S-palmitoylation rather than myristoylation of hSlo1 took place in our experiments. To this end, we radiolabeled hSlo1 with tritiated palmitic and myristic acids and subjected samples to 1.4 M β-mercaptoethanol and boiling for 5 min prior to gel loading. This treatment ruptures labile thioester bonds such as those of S-palmitoylated proteins but leaves intact oxyester and amide linkages (12). Cells radiolabeled with [3H]palmitic acid confirmed the incorporation of this fatty acid into hSlo1, as reported earlier for murine Slo1 (13). As expected, when [3H]palmitate-labeled hSlo1 was treated with 1.4 M β-mercaptoethanol, the signal was almost completely removed (Fig. 1C) by 91 ± 5% (n = 3). In contrast, equivalent treatment of myristoylated samples shown in Fig. 1B and subsequent experiments did not remove the radioactive signal, indicating that palmitoylation and myristoylation of hSlo1 are two independent mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Direct myristoylation of hSlo1. Representative fluorographs of immunoprecipitates from HEK293T cells not expressing (blank) or expressing hSlo1 that were metabolically radiolabeled with either [35S]methionine (A) or [3H]myristic acid (B). (C) Fluorograph of immunoprecipitated hSlo1 metabolically radiolabeled with [3H]palmitic acid. Samples were either untreated (−) or treated (+) with 1.4 M β-mercaptoethanol.

hSlo1 Myristoylation Occurs via a Posttranslational Mechanism.

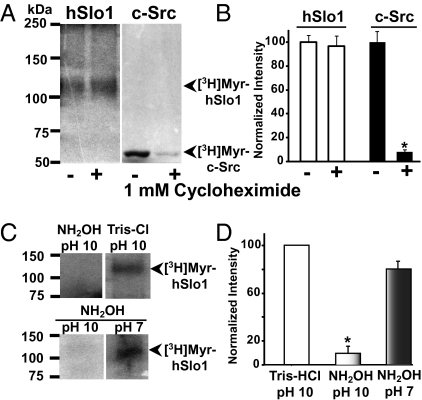

To differentiate whether myristoylation of hSlo1 occurs co- or posttranslationally, we inhibited the production of newly synthesized proteins with cycloheximide before [3H]myristic acid radiolabeling (14). We used as positive control c-Src, a prototype protein that undergoes N-myristoylation while the protein is being synthesized (7, 15). It is evident from Fig. 2A that cycloheximide has no effect on hSlo1 myristoylation, as radiolabeled signals were practically identical in control (−) and with cycloheximide (+) treatment. In contrast, c-Src myristoylation is almost abolished in the presence of cycloheximide compared with control. Mean densitometric values are shown in Fig. 2B (n = 3 under each condition). These results indicate that hSlo1 myristoylation occurs via a posttranslational process.

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity of [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 protein to cycloheximide and alkaline hydroxylamine. (A) [3H]Myristoylated (Myr) hSlo1 is insensitive to 1 mM cycloheximide treatment, showing the posttranslational nature of myristic acid's covalent attachment to hSlo1. As control, N-terminal [3H]myristoylation of c-Src is sensitive to cycloheximide and, thus, cotranslational. (B) Mean normalized intensity values for hSlo1 or for c-Src untreated (−) or treated (+) with cycloheximide. (C) Sensitivity of [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 to treatment with alkaline hydroxylamine (1 M NH2OH, pH 10) or to either 1 M Tris·HCl (pH 10) (negative control) (Upper Right) or neutral hydroxylamine (1 M NH2OH, pH 7) (Lower Right) (n = 3). (D) Mean normalized intensities under each condition. Signals for hSlo1 treated with 1 M Tris·HCl (pH 10) were taken as 100%. Each signal was referred to background signal in the same film. Alkaline hydroxylaminolysis significantly reduced [3H]myristate-labeled hSlo1 by ∼90% (n = 3 in each treatment). In this and the following figures, an asterisk marks significant differences.

Myristoylation of hSlo1 Occurs via Hydroxyester Bonds.

Fatty acids such as myristic acid covalently attach to the peptide backbone of eukaryotic proteins by one of three general mechanisms: (i) through an amide bond, (ii) by thioesterification, or (iii) via hydroxyester linkages (7, 16). These chemical bonds can be assessed based on their sensitivity to alkaline/neutral hydroxylamine hydrolysis. Amide-linked fatty acids can be distinguished from those that are ester-bound because amide bonds are resistant to alkaline hydroxylamine (1 M NH2OH, pH 9–11), whereas both thioester and hydroxyester bonds are ruptured by this treatment. In turn, thioesters are distinguished from hydroxyesters by the selective cleavage of thioesters by neutral hydroxylamine (1 M NH2OH, pH 6.6–7.5) (12). These chemical treatments were used to assess the nature of the myristoylation linkage on hSlo1. In-gel treatment of [3H]myristate-labeled hSlo1 with alkaline NH2OH (but not alkaline Tris·HCl as control) cleaves incorporated myristate (Fig. 2C Upper), indicating the presence of an ester bond, which could either be a thioester via a cysteine or a hydroxyester via serine (S), threonine (T), or tyrosine (Y) residues. Supporting the formation of a hydroxyester rather than a thioester bond, [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 signal was impervious to neutral (pH 7) NH2OH treatment (Fig. 2C Lower). Mean values are shown in Fig. 2D. The stability of [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 upon neutral NH2OH treatment is consistent with its resistance to the reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol, which readily displaces thioester-bound fatty acids such as S-palmitate (Fig. 1C) (12). Thus, [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 chemical stability is compatible with the linkage of myristic acid to hSlo1 via hydroxyester bonds, where S, T, or Y residues are potential targets.

Internal Myristoylation of hSlo1 Occurs at S/T Residues Located Within Intracellular Loop 1 or 3.

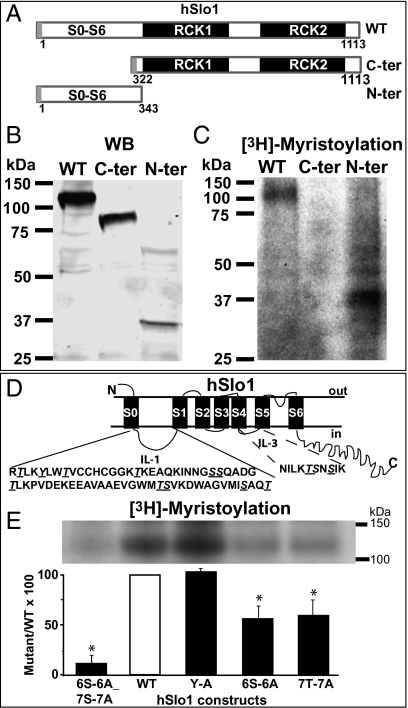

Next, we circumscribed the channel region and type of residues undergoing myristoylation. First, using truncated constructs and wild-type hSlo1 as control, we delineated which hSlo1 domain, the N-terminal third or the C terminus, is directly myristoylated. Second, using wild-type hSlo1, we made group mutants (S/T/Y to A) confined to the myristoylated domain uncovered by the truncated constructs and examined their ability to incorporate [3H]myristic acid.

For the first part of the studies, three constructs were used: the full-length wild-type hSlo1 (WT; amino acids 1–1113), the C-terminal domain (C-ter; amino acids 322–1113), and the N-terminal domain (N-ter; amino acids 1–343) (Fig. 3A). The expression of these constructs was checked by Western blot (Fig. 3B). After metabolic labeling with [3H]myristic acid, the immunoprecipitated products showed [3H]myristic acid incorporation in the WT hSlo1 as well as in the N-terminal domain (n = 3) but was under the detection limit for the C-terminal domain (n = 3) (Fig. 3C). These results pointed to the hSlo1 N-terminal domain as the main target for the hydroxyester type of myristoylation.

Fig. 3.

Serines/threonines of hSlo1 N terminus are targets for [3H]myristoylation. (A) Scheme of constructs used in B and C: full-length wild type (WT), C-terminal domain (C-ter), and N-terminal domain (N-ter). All constructs were c-Myc-tagged at the N terminus (gray bar). (B) Western blot (WB) of the same cell lysates (50 μg protein per lane) used for radiolabeling shows the expression of the three constructs at their expected sizes of 125 kDa (WT), 85 kDa (C-ter), and ∼40 kDa (N-ter). (C) [3H]Myristate is readily incorporated into hSlo1 (WT) and N-ter (n = 3) but not into the C-ter construct (no detectable signal at the size corresponding to this protein was observed; n = 3). (D) Scheme illustrating the topology of hSlo1 protein as well as the positions of the S, T, and Y residues (underlined) within IL-1 and IL-3. (E) (Lower) [3H]Myristic acid incorporation is minimal in the 6S-6A_7T-7A mutant but unaltered in the tyrosine mutant compared with WT. Mutating either the 6S or the 7T to A decreased myristoylation by ≥40%. (Upper) Fluorograph showing [3H]myristate incorporation to corresponding hSlo1 constructs.

We next examined hSlo1 N-terminal intracellular sequences, as these are most likely the ones exposed to myristoyl transferases, and located six S, seven T, and one Y in intracellular loops 1 (IL-1) and 3 (IL-3) (Fig. 3D). Four constructs were generated mutating the single Y (Y-A), the six S (6S-6A), the seven T (7T-7A), and all six S and seven T (6S-6A_7T-7A) to alanine (A), and were subjected to metabolic labeling with [3H]myristic acid. Fig. 3E shows that the Y residue in IL-1 is not a target for myristoylation, as metabolic labeling of the Y-A mutant was almost identical to hSlo1 WT (103 ± 3%, n = 4). In contrast, the 6S-6A and 7T-7A mutants showed a significant decrease in [3H]myristic acid incorporation compared with WT by 44% and 40%, respectively. The actual radioactive signals with respect to WT were 56 ± 13% for the 6S-6A mutant (n = 4) and 60 ± 15% for the 7T-7A mutant (n = 4). Further, the combined 6S-6A_7T-7A mutant caused an ∼90% decrease of [3H]myristic acid incorporation, with a remaining signal of 11.5 ± 7% (n = 3). These results demonstrate that hSlo1 myristoylation occurs mainly at S/T residues located in IL-1 or IL-3 of its N terminus, and indicate that the contribution of N-terminal S and T residues to hSlo1 myristoylation is additive.

Myristic Acid Induces Reduction of hSlo1 Channel Surface Expression and Activation Kinetics.

Protein N-myristoylation is known to control protein plasma membrane anchorage as well as protein activity (5). Thus, we wondered whether myristic acid could affect hSlo1 surface expression and/or its voltage- and/or its Ca2+-dependent activation properties.

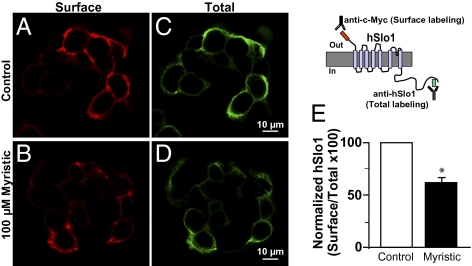

hSlo1 surface expression of control and myristic acid-treated cells was monitored by immunolabeling live cells to detect the extracellular c-Myc epitope (Fig. 4 A and B, scheme). For quantification purposes, live labeling was followed by permeabilization and labeling of total hSlo1 protein with anti-Slo1 Ab (Fig. 4 C and D, scheme) to calculate surface:total expression. Confocal images revealed that hSlo1 surface expression was significantly reduced in cells treated with 100 μM myristic acid (Fig. 4A versus Fig. 4B). Surface:total expression was normalized to control (n = 168 cells), which was set to 100%. Fig. 4E shows that myristic acid lowered surface expression to 59 ± 4% (n = 200 cells) of the control value. The 41% decrease in surface expression could be due to retention of the protein in the endoplasmic reticulum or due to internalization. Colabeling vehicle and myristic acid-treated cells for hSlo1 and for endoplasmic reticulum (ERp72), clathrin, or early endosomes (EEA-1), we observed an increase in colocalization with clathrin, suggesting that myristic acid reduces surface expression of hSlo1 by favoring its endocytosis (Figs. S1 and S2).

Fig. 4.

Myristic acid treatment of hSlo1-expressing cells causes a decrease of hSlo1 surface expression. (A and C) Surface and total labeling of control cells (treated with vehicle) expressing hSlo1. (B–D) Surface and total labeling after myristic acid treatment. Myristic acid caused a decrease in hSlo1 surface labeling. All panels are single confocal images near the middle of HEK293T cells expressing hSlo1. Images were median-filtered with a window of 128 pixels. (E) Mean % surface:total hSlo1 expression. The scheme shows the extracellular c-Myc epitope used for live labeling of the channel (red) and the intracellular epitope recognized by the hSlo1 Ab (green) used for total labeling.

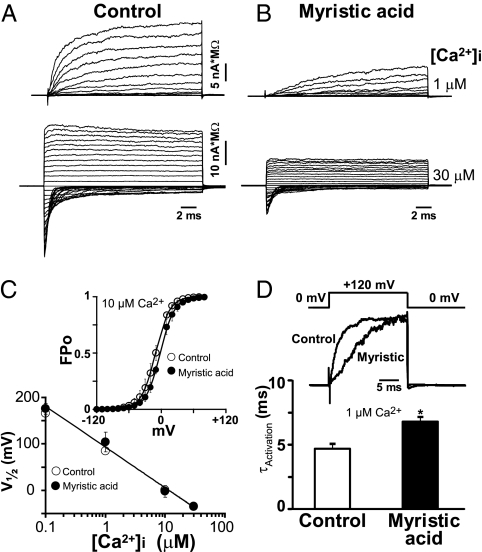

The decrease in hSlo1 surface expression induced by myristic acid treatment as assessed by immunocytochemistry would predict decreased hSlo1 macroscopic currents (I) as I = iNPo, where i = unitary current, N = number of channels, and Po = open probability. In agreement, inside-out patch-clamp recordings showed that hSlo1 macroscopic current density (expressed in nA*MΩ) generated from control cells (Fig. 5A) was larger than currents elicited in cells treated with myristic acid (Fig. 5B). Examples at two Ca2+ concentrations facing the intracellular side of the patch ([Ca2+]i) are given. Average current density–voltage relationships under both conditions are shown in Fig. 6C.

Fig. 5.

Myristic acid decreases hSlo1 functional expression and channel activation kinetics. (A and B) Currents recorded from HEK293T cells expressing hSlo1 treated overnight with vehicle (control; A) were larger than those from cells treated with 100 μM myristic acid (B). Patches were excised in bath solutions containing different Ca2+ concentrations. Currents were elicited by 20-ms test pulses to different potentials and normalized to pipette resistance. Holding potential (HP) = 0 mV. Test pulses for control and myristic acid-treated at 1 μM Ca2+ (upper traces in A and B) are from −40 to 120 mV, and at 30 μM Ca2+ are from −180 to +120 mV (lower traces in A and B). (C) Half-activation potentials (V1/2) as a function of free [Ca2+]i. V1/2 values were practically identical for control (○; n = 3–4) and myristic acid (●; n = 3–4) -treated cells. (Inset) Example of mean FPo versus voltage curve at 10 μM Ca2+ used to calculate V1/2 (Materials and Methods) for control (○) or myristic acid (●) -treated cells. (D) Myristic acid slowed down hSlo1 activation kinetics. Mean τActivation at +120 mV and 1 μM Ca2+ in paired experiments (same-day recording, same transfection) was 4.5 ± 0.3 ms in control (n = 5) and 7.1 ± 0.3 ms in myristic acid-treated cells (n = 3).

Fig. 6.

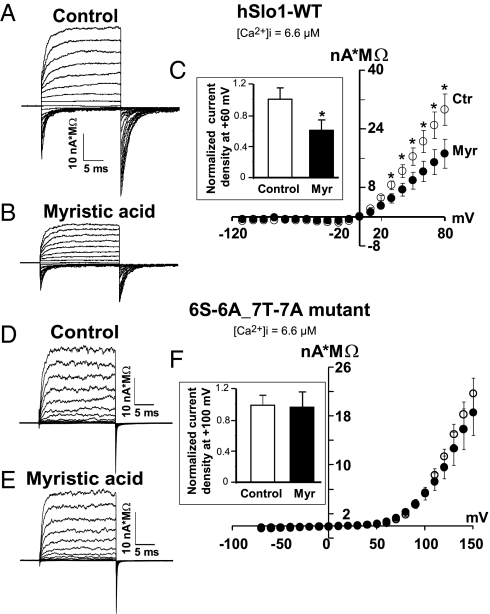

Mutation of serines and threonines in hSlo1 N terminus renders hSlo1 currents impervious to myristic acid treatment. Inside-out currents normalized to pipette resistance from cells expressing wild-type hSlo1 (hSlo1-WT) (A and B) or hSlo1 mutant 6S-6A_7T-7A (D and E) that were treated overnight with vehicle (control; A and D) or with 100 μM myristic acid (B and E). Test pulses of 20 ms were from −110 to +80 mV in A and B and from −70 to +150 mV in D and E every 10 mV. Repolarizing pulses were to −70 mV. HP = 0 mV. [Ca2+]i = 6.6 μM. (C) Mean current density as a function of voltage is decreased by myristic acid pretreatment (Myr, ●; n = 6) compared with control (Ctr, ○; n = 6) in hSlo1-WT. (Inset) Mean normalized hSlo1-WT current density recorded at +60 mV (n = 6) in control and in myristic acid-treated cells. (F) Mean current density–voltage relationships were practically the same for control (○; n = 10) and myristic acid-treated (●; n = 9) cells expressing the 6S-6A_7T-7A mutant channel. Note that the mutant channel exhibits a right shift of ∼50 mV in its activation potential from ∼10 mV in WT to ∼60 mV. (Inset) Mean normalized 6S-6A_7T-7A mutant current density recorded at +100 mV in control and myristic acid-treated cells (n = 9).

To determine whether myristic acid affects other properties of hSlo1 currents, different potentials and various [Ca2+]i (1–30 μM) were used to activate the channels from control and myristic acid-treated cells. Half-activation potentials (V1/2) as a function of free Ca2+ in the absence (control; n = 3–4) or presence of myristic acid (n = 3–4) were practically identical (Fig. 5C). The inset shows an example of fractional (F) Po versus V curves used to calculate V1/2. In this case, [Ca2+]i = 10 μM Ca2+ and V1/2 is ∼0 mV for both control and myristic acid-treated cells. Overall, the results indicate that myristic acid did not affect hSlo1 steady-state voltage/Ca2+ sensitivities.

In contrast, hSlo1 channel activation kinetics is slower after myristic acid treatment with respect to control. For easy comparison, the inset in Fig. 5D shows superimposed traces under the two conditions. The mean activation time constant (τActivation) measured at +120 mV and 1 μM Ca2+ was 1.6 times slower in myristic acid-treated patches than in control patches (Fig. 5D).

hSlo1 Mutant 6S-6A_7T-7A Resistant to Myristate Incorporation Loses Its Ability to Respond to Myristic Acid Treatment.

We next compared current density values in inside-out patches of vehicle (control) and myristic acid-treated cells expressing hSlo1-WT (Fig. 6 A–C) versus hSlo1 mutant 6S-6A_7T-7A (Fig. 6 D–F). In hSlo1-WT, myristic acid treatment showed a clear reduction in current density with respect to control (Fig. 6 A and B). Mean current density versus voltage curves under the two conditions are shown in Fig. 6C. Under conditions where the channels’ open probability reaches its limiting value (+60 mV and free [Ca2+]i of 6.6 μM), myristic acid treatment reduced the number of WT channels reaching the surface by an average of ∼39% (Fig. 6C Inset), which is close to the value of hSlo1 decrease measured by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 4). Mean current density values at +60 mV were 20 ± 3.2 nA*MΩ (n = 6) for hSlo1-WTControl and 12 ± 2.8 nA*MΩ (n = 6) for hSlo1-WTMyristic. However, when hSlo1 6S-6A_7T-7A was used, 100 μM myristic acid (n = 9) caused no significant reduction in current density compared with vehicle (n = 10) (Fig. 6 D–F). The mean current density values recorded at +100 mV and [Ca2+]i of 6.6 μM were practically identical for control (5.5 ± 0.6 nA*MΩ; n = 10) and myristic acid-treated cells (5.3 ± 1 nA*MΩ; n = 9). These results provide direct evidence that the reduction in hSlo1 surface expression by myristic acid is due to hSlo1 internal myristoylation at its IL-1 or IL-3 of its N-terminal domain.

Discussion

Several studies have reported palmitoylation and/or myristoylation of several key signaling proteins (5, 17, 18). Although ion channels are integral parts of the cell signaling machinery, only a few studies have identified ion channel palmitoylation (13, 19–22). Furthermore, no information on direct myristoylation of any ion channel has been reported yet. Classical myristoylation occurs at an N-terminal glycine residue, and another rare form takes place at an internal amino acid residue (7, 17). Only three reports were found identifying internal myristoylation in mammalian proteins (8–10). Our present study provides compelling evidence that the hSlo1 channel is internally myristoylated via a hydroxyester chemical bond in a posttranslational fashion at both serine and threonine residues located within the N-terminal third of hSlo1. The functional role of hSlo1 myristoylation is to control hSlo1 channel surface expression.

hSlo1 Direct Internal Myristoylation.

Radiolabeling of proteins with [3H]myristic or [3H]palmitic acids is commonly used to identify lipid-modified proteins. We have undertaken this approach to show that hSlo1 is indeed directly myristoylated. This direct myristoylation was performed under conditions intended to minimize the interconversion of [3H]myristic acid by cells into amino acids and other types of lipids such as [3H]palmitic acid by including Na-pyruvate (Materials and Methods) (23). This step is crucial, as palmitic acid has been shown recently to incorporate into murine Slo1 (13). In addition, we provide evidence that under our experimental conditions at least part of the [3H]myristic pool remains intact and directly incorporates into hSlo1 because treatment of radiolabeled hSlo1 with 1.4 M β-mercaptoethanol and boiling for 5 min did not remove the [3H]myristate signal, which would have been removed if its chemical nature were palmitic acid attached to the protein through a thioester chemical linkage (24). This conclusion was further supported by the efficient removal of [3H]palmitate from hSlo1 by the same treatment. Hydroxylaminolysis properties of [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 indicated that myristate is covalently attached to hSlo1 via a hydroxyester linkage and, thus, acylation could have taken place at any possible accessible intracellular threonine (T), serine (S), or tyrosine (Y).

hSlo1 has as many as 145 hydroxyl-containing residues throughout the intracellular regions of the protein and therefore potential sites for myristoylation. Intracellular loops 1 and 3 (but not loop 2) of the N-terminal domain carry 14 T/S/Y residues (1 tyrosine, 6 serines, and 7 threonines), whereas the intracellular C terminus carries 131 T/S/Y residues (24 tyrosines, 38 threonines, and 69 serines). Deletion mutants helped to circumscribe the N-terminal third as the myristoylation target, which was corroborated in the context of the whole protein by group-directed mutagenesis of IL-1 and IL-3. The data demonstrated that serine and threonine but not tyrosine residues located at hSlo1 IL-1 or IL-3 are the main targets of direct myristoylation, as their simultaneous mutation to alanines almost abolished (∼90%) channel direct myristoylation. The remaining 10% of myristoylation likely happens at its C terminus; however, when we used the C terminus in isolation, it did not show any [3H]myristate incorporation. It is possible that the truncated C terminus changes conformation, precluding us from observing the 10% of myristoylation that remains in the WT channel after mutagenesis of the N-terminal domain. Nevertheless, functional experiments showed that serines and threonines in IL-1 or IL-3 account for the changes in channel surface activity by myristic acid. Further site directed mutagenesis experiments should solve whether myristoylation at multiple or single key Ser or Thr residues in IL-1 or IL-3 mediate the observed effects.

Myristoylation of hSlo1 Regulates Channel Surface Expression.

Fatty acid acylation of proteins is involved in regulating their surface expression and/or function. For example, early studies showed that palmitoylation may regulate nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel expression (19). Recent reports indicate that palmitoylation modulates Kv1.1 channel voltage sensitivity and channel kinetics (21), whereas it modulates Kv1.5 surface expression (22). Also, palmitoylation of the mSlo1-STREX variant allows efficient plasma membrane targeting of the intracellular C terminus, supporting channel inhibition by protein kinase A phosphorylation (13). We now show that myristoylation regulates hSlo1 surface expression but does not affect the channel steady-state voltage-dependent activation. Mechanisms regulating hSlo1 surface expression comprise the inclusion of splice inserts, association with caveolin, and association with β-subunits (25–28). Interestingly, an hSlo1 N-terminal splice variant (within the first intracellular loop) expressed in myometrium produces a pore-forming proteolytic fragment that exposes a putative N-myristoylation site. Although N-myristoylation of this fragment has not been demonstrated directly, it is retained intracellularly regulating expression of functional channels (29). In summary, our findings have uncovered internal myristoylation as an additional cellular regulatory mechanism modulating hSlo1 numbers and function at the cell surface.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

[9,10(n)-3H]Myristic acid (54 Ci/mmol) and [9,10(n)-3H]palmitic acid (53 Ci/mmol) were from Amersham or PerkinElmer. L-[35S]Methionine (>1,175 Ci/mmol) was from ICN. Amplify reagent was from GE Healthcare. c-Src (GenBank accession no. J00844) is in pCDNA3. All hSlo1 (GenBank accession no. U11058) constructs were tagged with c-Myc epitope (30) at the N terminus but with the glycine at position 2 mutated to alanine. For simplicity, we do not refer to the c-Myc tag when naming the constructs. Y/S/T mutants were generated by GenScript. Cycloheximide and anti-c-Myc monoclonal Ab were from Sigma. Anti-Slo1 polyclonal Ab was from Alomone Labs (APC-021). Secondary Abs were from Molecular Probes.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (DMEM complete medium). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and used within 24–48 h. For metabolic labeling with [3H]myristic/palmitic acids or L-[35S]methionine and biochemistry experiments, cells were transfected at a density of ∼5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish, and for patch clamp or immunocytochemistry, cells were used at a density of ∼7 × 105 cells/35-mm dish. Before patch clamp, cells were plated onto poly-d-lysine (0.1 mg/mL) -coated coverslips.

Metabolic Labeling.

[35S]Methionine.

Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were incubated for 1 h in methionine-free DMEM complete medium followed by 4 h with medium containing 200 μCi L-[35S]methionine/100-mm plate.

[3H]Myristic/palmitic acid.

Before use, [3H]myristic and [3H]palmitic acids were dried under a stream of nitrogen and then reconstituted in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen), and supplemented with 100 μg/mL fatty acid-free BSA and 10 mM Na-pyruvate. Na-pyruvate acts as a source of acetyl-coA and minimizes interconversion of [3H]myristic acid to other metabolites (23). Thirty-two hours posttransfection, DMEM complete medium was replaced with Opti-MEM supplemented with 100 μg/mL fatty acid-free BSA, 10 mM Na-pyruvate, and 1 mCi [3H]myristic or [3H]palmitic acids and incubated overnight at 37 °C. For the treatment with cycloheximide, cells expressing hSlo1 or c-Src (24 h posttransfection) were treated with 1 mM cycloheximide for 6 h before incubation with 1 mCi [3H]myristic acid overnight. After metabolic labeling, cells were washed three times with ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered solution and subjected to immunoprecipitation (SI Materials and Methods) and SDS/PAGE. The gels were stained/destained, treated with Amplify, dried, and exposed with Kodak X-omat films for ∼3 wk to 2 mo for 3H and ∼1 wk for 35S at –80 °C.

In-Gel Deacylation of hSlo1.

Immunoprecipitated [3H]myristoylated hSlo1 samples were divided in two, separated on the same SDS/PAGE gel and fixed, and the duplicate lanes were cut. Each sample was treated for 18 h at room temperature in one of the following freshly prepared solutions: 1 M alkaline NH2OH (pH 10), 1 M neutral NH2OH (pH 7), or, as control, 1 M Tris·HCl (pH 10). The gels were treated for autofluorography as above.

Immunocytochemistry.

Cells expressing hSlo1 were plated onto 1 mg/mL poly-D-lysine plus 0.1 mg/mL collagen-precoated coverslips and treated overnight either with vehicle (control) or with 100 μM myristic acid from a 100 mM stock solution in 70% ethanol. For hSlo1 live surface labeling, nonpermeabilized cells were incubated (1 h on ice, under 95% air, 5% CO2 atmosphere) with 2.4 μg/mL anti-c-Myc monoclonal Ab (recognizing the hSlo1 c-Myc extracellular epitope) in culture media. Then, excess Ab was washed twice (5 min each on ice) followed by cell fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (20 min, room temperature). Cells were then “total-labeled” by permeabilizing with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS (30 min, room temperature) and labeling with anti-Slo1 polyclonal Ab (recognizing the C terminus, 3 μg/mL, overnight, 4 °C). Excess Abs were washed (three times, 5 min each at room temperature) and treated with corresponding goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 and goat anti-mouse Alexa 568 secondary Abs. After washing (three times, 5 min, room temperature), coverslips were dried and mounted with a Prolong Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes) prior to confocal imaging.

Patch Clamp.

Macroscopic currents were measured, at the end of test pulses, in inside-out patches. Pipette resistances were measured for each patch (∼3 MΩ) and used to calculate current density = I × R. Half-activation potentials were determined by fitting FPo versus potential curves to a Boltzmann distribution (SI Materials and Methods). Pipette and bath solutions were 105 mM potassium methanesulfonate, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0). Different [Ca2+]i's were adjusted using 5 mM EGTA (100 nM Ca2+) or 5 mM HEDTA (≥1 μM Ca2+); free [Ca2+]i was measured with a Ca2+ electrode (World Precision Instruments). Custom-made programs were used for current recording and data analysis. Myristic acid treatment was the same as for immunocytochemistry.

Confocal Images, Digital Processing, and Signal Quantification.

Confocal sections were acquired every 0.5 μm (z axis) at 0.115 μm/pixel (x-y plane). Unless otherwise stated, background signals were digitally removed using the median filter algorithm with a custom-made program using a window of 32 pixels prior to analysis. To evaluate levels of expression, groups of cells expressing hSlo1 were randomly selected from the field to quantify integrated pixel intensity at the surface (live labeled image) and total expression of the same cells (labeling after permeabilization) using MetaMorph (Molecular Devices) (SI Materials and Methods). Ratios (surface:total) were normalized to the control. All conditions, including optical sectioning and exposures, were identical for all experiments.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are mean ± SE. Student's t test with P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL54970 (to L.T.), HL088640 (to E.S.), and HL096740 (to E.S. and L.T.) and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowships 0825273F (to M.L.) and 10POST4230081 (to Y.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1008863108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Alioua A, et al. In: Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Squire LR, editor. Oxford: Academic; 2009. pp. 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hou S, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Modulation of BKCa channel gating by endogenous signaling molecules. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:26–35. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu R, et al. MaxiK channel partners: Physiological impact. J Physiol. 2006;570:65–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber B, Eisenhaber F. N-terminal N-myristoylation of proteins: Refinement of the sequence motif and its taxon-specific differences. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:523–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resh MD. Fatty acylation of proteins: New insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Utsumi T, Sakurai N, Nakano K, Ishisaka R. C-terminal 15 kDa fragment of cytoskeletal actin is posttranslationally N-myristoylated upon caspase-mediated cleavage and targeted to mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2003;539:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz AM, Henderson LE, Oroszlan S. Fatty acylation of proteins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedo JA, Collier E, Watkinson A. Myristyl and palmityl acylation of the insulin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:954–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson FT, Bursten SL, Fanton C, Locksley RM, Lovett DH. The 31-kDa precursor of interleukin 1α is myristoylated on specific lysines within the 16-kDa N-terminal propiece. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7245–7249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson FT, Bursten SL, Locksley RM, Lovett DH. Myristyl acylation of the tumor necrosis factor α precursor on specific lysine residues. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1053–1062. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson EN, Towler DA, Glaser L. Specificity of fatty acid acylation of cellular proteins. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3784–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bizzozero OA. Chemical analysis of acylation sites and species. Methods Enzymol. 1995;250:361–379. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)50085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian L, et al. Palmitoylation gates phosphorylation-dependent regulation of BK potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:21006–21011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armah DA, Mensa-Wilmot K. S-myristoylation of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C in Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5931–5938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilcox C, Hu JS, Olson EN. Acylation of proteins with myristic acid occurs cotranslationally. Science. 1987;238:1275–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.3685978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanley P, Koronakis V, Hughes C. Acylation of Escherichia coli hemolysin: A unique protein lipidation mechanism underlying toxin function. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:309–333. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.309-333.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutin JA. Myristoylation. Cell Signal. 1997;9:15–35. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resh MD. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson EN, Glaser L, Merlie JP. α and β subunits of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contain covalently bound lipid. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5364–5367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt JW, Catterall WA. Palmitylation, sulfation, and glycosylation of the α subunit of the sodium channel. Role of post-translational modifications in channel assembly. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:13713–13723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gubitosi-Klug RA, Mancuso DJ, Gross RW. The human Kv1.1 channel is palmitoylated, modulating voltage sensing: Identification of a palmitoylation consensus sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5964–5968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501999102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Foster K, Li Q, Martens JR. S-acylation regulates Kv1.5 channel surface expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C152–C161. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00480.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeidman R, Jackson CS, Magee AI. Analysis of protein acylation. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1402s55. Chap. 14, Unit 14.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt M, Schmidt MF, Rott R. Chemical identification of cysteine as palmitoylation site in a transmembrane protein (Semliki Forest virus E1) J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18635–18639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alioua A, et al. Slo1 caveolin-binding motif, a mechanism of caveolin-1-Slo1 interaction regulating Slo1 surface expression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4808–4817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarei MM, et al. An endoplasmic reticulum trafficking signal prevents surface expression of a voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel splice variant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10072–10077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0302919101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarei MM, et al. Endocytic trafficking signals in KCNMB2 regulate surface expression of a large conductance voltage and Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Neuroscience. 2007;147:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma D, et al. Differential trafficking of carboxyl isoforms of Ca2+-gated (Slo1) potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korovkina VP, Brainard AM, England SK. Translocation of an endoproteolytically cleaved maxi-K channel isoform: Mechanisms to induce human myometrial cell repolarization. J Physiol. 2006;573:329–341. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meera P, Wallner M, Song M, Toro L. Large conductance voltage- and calcium-dependent K+ channel, a distinct member of voltage-dependent ion channels with seven N-terminal transmembrane segments (S0-S6), an extracellular N terminus, and an intracellular (S9-S10) C terminus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14066–14071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.