Summary

This paper presents a new modeling strategy in functional data analysis. We consider the problem of estimating an unknown smooth function given functional data with noise. The unknown function is treated as the realization of a stochastic process, which is incorporated into a diffusion model. The method of smoothing spline estimation is connected to a special case of this approach. The resulting models offer great flexibility to capture the dynamic features of functional data, and allow straightforward and meaningful interpretation. The likelihood of the models is derived with Euler approximation and data augmentation. A unified Bayesian inference method is carried out via a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm including a simulation smoother. The proposed models and methods are illustrated on some prostate specific antigen data, where we also show how the models can be used for forecasting.

Keywords: Diffusion model, Euler approximation, Nonparametric regression, Simulation smoother, Stochastic differential equation, Stochastic velocity model

1. Introduction

With the advent of many high-throughput technologies, functional data are routinely collected. To analyze those data, we usually assume that the observations are generated from a unknown mean function with additive errors. This paper aims to use diffusion model to estimate the mean function and its derivatives under this assumption.

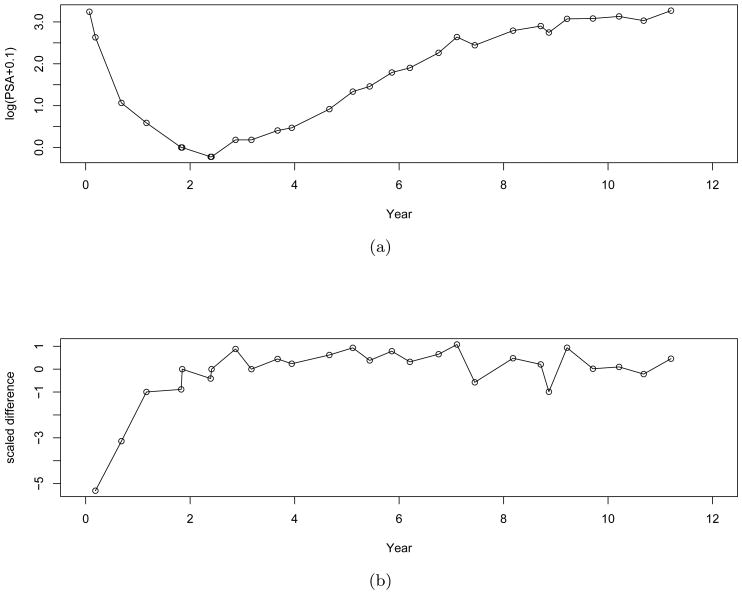

There is a rich literature on penalized methods to regulate the mean function and to incorporate smoothness assumptions by using the penalized functions, with the focus on estimation of the unknown mean function(Wahba, 1990; Green and Silverman, 1994; Ramsay and Silverman, 2005). In many practical settings, not only the mean function but also its derivatives (in general referred to as dynamics) offer useful insights regarding the underlying mechanism of a physical or biological process. For example, in the study of prostate specific antigen (PSA), an important biomarker of prostate cancer, we are not only interested in the PSA level but also the dynamics of PSA. Figure 1 displays raw data of one patient's PSA level (panel (a)) and the scaled difference (panel (b)) over time (Proust-Lima et al., 2008), where Y (t) = log(PSA(t)+0.1) and scaled difference is . It is easy to observe that the PSA level is largely driven by the behavior of the scaled difference that itself provides meaningful clinical interpretation. Modeling the process of the scaled difference will facilitate the modeling of the PSA level. However, the connection between the PSA level and the scale difference cannot be established simply by association, but instead by hierarchical models of dynamics, as the scaled difference may be regarded as the derivative of the PSA level.

Figure 1.

PSA plots: (a) the raw data; (b) the scaled difference

This paper presents a new modeling strategy in functional data analysis, where the priori smoothness assumption is specified by stochastic diffusion processes, using a set of ordinary and stochastic differential equations connected in a hierarchical fashion, in the hope that it not only models the mean function but also captures its various dynamic features. Note that this approach treats the unknown mean function and it dynamics as a sample path of stochastic processes. This treatment is different from kernel smoothing and spline smoothing, where the mean function is regarded as a deterministic unknown function. Our treatment of the mean function is similar to that considered in the Gaussian process models for nonparametric Bayesian data analysis, where the mean function is governed by a prior Gaussian process with a mean function M(t; ϕ) and a covariance function C(t, t′; ϕ) with hyperparameters ϕ (Muller and Quintana, 2004; Rasmussen and Williams, 2006). However, the hierarchical structure of the proposed model enables us to make inference of the mean function and its dynamics simultaneously, especially the method provides the estimation and inference for parameters of the stochastic differential equation from noisy data. We note that this differs from the approaches to parameter estimation for models based on ordinary differential equations as recently developed by, for example, Ramsay et al. (2007) and Liang and Wu (2008).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the proposed model and considers two special cases. For each cases, we give model interpretation and discuss several interesting relationships. Section 3 develops Bayesian inference for stochastic functional data analysis models, where the likelihood is derived using Euler approximation and data augmentation. Section 4 presents a simulation study. In Section 5, the proposed models and methods are applied to estimate the PSA profile from prostate cancer data. Concluding remarks are given in Section 6. Technical details are included in the Web Appendix.

2. Stochastic Velocity Model

2.1 Model Specification

Consider a regression model for functional data of the form:

| (1) |

where Ω is the sample space,

o is the index set of observation times, defined as

o is the index set of observation times, defined as

o ≔ {tj : t1 < t2 < … < tJ}, and U(·, ω) is an unknown function of interest to be estimated and

at each time t. The goal is to estimate the function U(·, ω) and its derivatives given time series observations, Yo = [Y (t1), Y(t2), …, Y(tJ)]T. In this paper, we develop methods based on diffusion type models for estimation of U(·, ω) and its derivatives U(p)(·, ω), p = 1, …, m − 1. Here, U(·, ω) is regarded as a realization of an underlying stochastic process U ≔ U(·, ·) and thus the observed data is the a sample path of the process plus measurement error.

o ≔ {tj : t1 < t2 < … < tJ}, and U(·, ω) is an unknown function of interest to be estimated and

at each time t. The goal is to estimate the function U(·, ω) and its derivatives given time series observations, Yo = [Y (t1), Y(t2), …, Y(tJ)]T. In this paper, we develop methods based on diffusion type models for estimation of U(·, ω) and its derivatives U(p)(·, ω), p = 1, …, m − 1. Here, U(·, ω) is regarded as a realization of an underlying stochastic process U ≔ U(·, ·) and thus the observed data is the a sample path of the process plus measurement error.

Model (1) is useful to model the PSA level of prostate cancer nonparametrically, where U(t, ω) describes the population mean PSA process. To understand the dynamics of the process, we incorporate models of rate and/or higher order derivatives into model (1). To proceed, we begin by treating U(t, ω) in model (1) as a realization of U(t) ≔ U(t, ·), which enables us to express U(t) in the form of a stochastic diffusion model. That is, the stochastic process U satisfies the following ordinary differential equation(ODE),

| (2) |

and its (m−1)th order derivative V(t) is governed by a stochastic differential equation(SDE), given as follows:

| (3) |

where W(t) is the standard Wiener process, ϕs is the parameter vector and

s ≔ {t : t0 ≤ t ≤ tJ} is a continuous index set. In addition, the initial condition at time t0 is assumed to be

. In this paper, we use continuous time stochastic processes U and V to model the underlying dynamics. Let V ≔ {V(t, ω) : t ∈

s ≔ {t : t0 ≤ t ≤ tJ} is a continuous index set. In addition, the initial condition at time t0 is assumed to be

. In this paper, we use continuous time stochastic processes U and V to model the underlying dynamics. Let V ≔ {V(t, ω) : t ∈

s, ω ∈ Ω}, defined on a probability space (Ω, ℱ

s, ω ∈ Ω}, defined on a probability space (Ω, ℱ

). We limit V to a one-dimensional continuous state space and a continuous index set

). We limit V to a one-dimensional continuous state space and a continuous index set

s. Similar definition and limitation hold for U. The SDE in (3) defines a stochastic diffusion process V, which is a Markov process with almost surely continuous sample paths. The existence and uniqueness of the process can be shown rigorously; see Grimmett and Stirzaker (2001, Chap. 13) and Feller (1970, Chap. 10).

s. Similar definition and limitation hold for U. The SDE in (3) defines a stochastic diffusion process V, which is a Markov process with almost surely continuous sample paths. The existence and uniqueness of the process can be shown rigorously; see Grimmett and Stirzaker (2001, Chap. 13) and Feller (1970, Chap. 10).

The state equations (2) and (3), along with the observation equation (1), make up a continuous-discrete state space model (CDSSM) (Jazwinski, 1970, Chap. 6). Although inference methods will be demonstrated for the stochastic velocity model(SVM), namely the CDSSM with m = 2, they are applicable to any higher order of m. For example, m = 3 corresponding to a stochastic acceleration model(SAM). For SVM, the latent process U(t) represents position, and its first derivative V(t) is the velocity of U(t). Similarly, in the SAM, the processes θ(t) ≔ [U(t), U(1) (t), V(t)]T represent the position, velocity and acceleration respectively. Coefficients a{V(t), ϕs} and b{V(t), ϕs} in (3) are typically specified according to the objectives of a given study. The drift term a{V(t), ϕs} can be interpreted as the instantaneous mean of velocity; it represents the expected conditional acceleration when V(t) denotes velocity. Likewise, b2{V(t), ϕs} measures the instantaneous variance or volatility of velocity. The diffusion model and the consideration of higher derivative in (2) allow considerable flexibility and the incorporation of various dynamic features into the two coefficients a{V(t), ϕs} ∈ ℝ and b{V(t), ϕs} ∈ ℝ+. By this model-based approach, various stochastic processes can be specified for V(t), the model fitting can be evaluated by likelihood-based model assessment, and forecasting can also be easily carried out.

Two special cases are considered in this paper. They are, (i) SVM with Wiener process V(t), denoted SVM-W, where a{V(t), ϕs} = 0, b{V(t), ϕs} = σξ and ; (ii) SVM with Ornstein-Uhlenbeck(OU) process V(t), denoted SVM-OU, where a{V(t), ϕs} = −ρ{V(t) − ν̄}, b{V(t), ϕs} = σξ and .

2.2 Wiener process for velocity

In SVM-W, V(t) follows a Wiener process, the instantaneous variance measures the disturbance of velocity and influences the smoothness of U(t). With the smaller the , V(t) will appear less wiggly and hence U(t) will be smoother. If σξ = 0, the velocity V(t) is constant over time, so U(t) becomes a straight line.

Integrating (2) and (3) for m = 2, a{V(t), ϕs} = 0 and b{V(t), ϕs} = σξ, we have

| (4) |

| (5) |

The velocity V(t) follows the Wiener process starting at V(t0). The position U(t) follows a linear trend with deviation governed by the integrated Wiener process, . As shown in the literature, there exists an interesting “equivalence” between smoothing splines and Bayesian estimation of SVM-W(Kimeldorf and Wahba, 1970; Wahba, 1978; Weinert and Sidhu, 1980). By equivalence, we mean that the two methods give the same estimate of U(t), see Web Appendix A for the detail.

2.3 Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process for velocity

The OU process originated as a model for the velocity of a particle suspended in fluid (Uhlenbeck and Ornstein, 1930). The velocity V(t) takes the form:

| (6) |

where ρ ∈ ℝ+, ν̄ ∈ ℝ, and σξ ∈ ℝ+. In contrast to the Wiener process, the OU process is a stationary Gaussian process with stationary mean ν̄ and variance . has the same interpretation as that of the Wiener process. The instantaneous mean or the expected conditional acceleration − ρ{V(t) − ν̄} describes how fast the process moves. The larger the ρ, the more rapidly the process evolves toward ν̄. The farther V(t) departs from ν̄, the faster the process moves back towards ν̄.

If the data are equally spaced, namely δj ≔ tj − tj−1 = δ, V(t) coincides with the first order autogreession(AR(1)) process with autocorrelation exp(−ρδ). The converse also holds; AR(1) converges weakly to the OU process as δj→ 0 (Cumberland and Sykes, 1982).

For the PSA data example in figure 1 it is obvious that the scaled difference is varying around a certain level after about 3 years, which is more consistent with the behavior of an OU process than a Wiener process, suggesting that the SVM-OU may fit better.

3. Estimation and Inference

Statistical inference for CDSSM is challenging because we consider a vector of stochastic processes θ(t) ≔ [U(t), U(1)(t), …, U(m−2)(t), V(t)]T simultaneously. This leads to a complex likelihood function, which may not even exist in closed form. Since an analytical solution of the SDE is rarely available, the conditional distribution of θ(t) given θ(t′), for t′ < t, which we call the exact transition density, does not have a simple closed form expression. Thus exact inference for the latent processes and its parameters is not generally possible. Hence, a numerical approximation will usually be needed. We will use the Euler approximation of the SDE to approximate the transition density, which enables us to obtain a simple closed form of the likelihood. To alleviate the errors associated with this approximation, it may be helpful to augment the observed data by adding virtual data at extra time points (Tanner and Wong, 1987), so that the interval between adjacent time points is shorter and a preciser approximation is achieved. Even when the exact transition density exists, using the approximated one will significantly simplify the estimation of parameters ϕs. A case in the point is the SVM-OU.

The resulting likelihood with this approximate method involves high-dimensional integrals, and we adopt a Bayesian approach using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC, Geman and Geman 1987, Gelfand and Smith 1990, Gilks et al. 1996) to estimate U(t), V(t) and the parameters , with the assistance of the simulation smoother(Durbin and Koopman, 2002).

Different approaches for inference for discretely observed diffusions are reviewed by Beskos et al. (2006). These includes numerical approximations to obtain likelihood functions (Aït-Sahalia, 2002) and methods based on iterated filtering (Ionides et al., 2006). The idea of Euler approximation has been applied to the stochastic volatility model in the finance literature. Pedersen (1995) applied the approximation and data augmentation to facilitate Monte Carlo integration and it was further developed by Durham and Gallant (2002). Bayesian analysis of the diffusion model, especially the stochastic volatility model, has been developed by many authors, including Elerian et al. (2001), Eraker (2001), and Roberts and Stramer (2001). Sorensen (2004) gave a survey on inference methods for stochastic diffusion models in finance. Distinctions between the models considered in financial statistics and the models considered in this paper are that we specify an observation equation to allow for the measurement errors. Most methods of inference for diffusion process do not extend easily when there is measurement error (Beskos et al., 2006). However, MCMC methods can be extended. A further distinction is that we consider the case m > 1 for the ODE, and that we apply the ODE and SDE to model various biomedical phenomena via U(t) and V(t). Thus, the SVM is focused on estimating the unknown sample paths of the latent stochastic process U(t) and V(t), whereas the diffusion models commonly used in the finance literature do not include an observation equation for measurement errors and typically focus on estimating the volatility or variance of the process of interest, for example, derivative securities.

3.1 Likelihood and Euler approximation

To develop Bayesian inference with an MCMC algorithm, we begin with the likelihood of the SVM:

where Uo ≔ [U(t1), U(t2), …, U(tJ)]T, Vo≔ [V(t1), V(t2), …, V(tJ)]T, and yo ≔ [y(t1), y(t2), …, y(tJ)]T are vectors of the latent states and observations at t ∈

o. θ0 = [U(t0), V(t0)]T is the unknown initial vector of the latent states, and [· ∣ ·] denote conditional density. The conditional density of the observations is given by

o. θ0 = [U(t0), V(t0)]T is the unknown initial vector of the latent states, and [· ∣ ·] denote conditional density. The conditional density of the observations is given by

since the observations are mutually independent given the latent states and follow a normal distribution according to model (1), where ϕ(· ∣ UG, ) is the normal density with mean UG and variance . In principle, the density of latent states Uo and Vo can be written as:

due to the Markov property. The exact transition density [U(tj), V(tj) ∣ U(tj−1), V(tj−1), ϕs) exists in a closed form only for few models with simple SDEs. Even in those cases, the exact transition density may have a complex form. For SVM-OU,

| (7) |

with

the proof of which is given by Zhu (2010). When using data augmentation, we may take the component wise first-order Taylor approximation of mOU, VOU with respected to δj and get

| (8) |

| (9) |

We note that these are the same expressions as those obtained by applying Euler approximation to SVM-OU. Thus although m̃OU and ṼOU as given in (8) and (9) are not strictly necessary for calculating [Uo, Vo ∣ θ0, ϕs] when mOU and VOU are available, they however lead to a simpler form for parameter ρ, which is much easier to update and converges much faster in the following MCMC algorithm.

For a general SDE, e.g. (3), the forms for U(t) and V(t) are:

where [U(tj), V(tj) ∣ U(tj−1), V(tj−1), ϕs] is implicitly defined but in general is not available analytically. To deal with this difficulty we use the Euler approximation to obtain a numerical approximation of the transition density in the general SDE case.

The Euler approximation is a discretization method for the SDE through the first-order strong Taylor approximation (Kloeden and Platen, 1992). The resulting discretized versions of the ODE and the SDE in (2) and (3) are given by, respectively,

| (10) |

| (11) |

where δj ≔ tj − tj−1 and ηj ≔ W(tj) − W(tj−1) ∼

(0, δj). For t ∈ [tj−1, tj], a linear interpolation takes the form

(0, δj). For t ∈ [tj−1, tj], a linear interpolation takes the form

A similar linear interpolation is applied to Ũ(J)(t). Bouleau and Lepingle (1992) showed that under some regularity conditions, with constant C, the Lp-norm of the discretization error is bounded and given by:

This indicates that if J is sufficiently large, which can be achieved when the maximum of δj is sufficiently small for fixed interval [t1, tJ], then Ṽ(J)(t) will be close to its continuous counterpart V(t) with arbitrary precision.

In the rest of this paper, we assume the δj is sufficiently small and the approximation is well achieved. To simplify notation, we replace Ṽ(J)(t) with V(t) and Ũ(J)(t) with U(t), for t ∈

s. Under these assumptions, the exact transition density, if it exists, is well approximated by the approximate transition density, as shown in the SVM-OU. Note that equations (10) and (11) imply the approximate transition densities of U(t) and V(t) are Gaussian for t ∈

s. Under these assumptions, the exact transition density, if it exists, is well approximated by the approximate transition density, as shown in the SVM-OU. Note that equations (10) and (11) imply the approximate transition densities of U(t) and V(t) are Gaussian for t ∈

o, because they are linear combinations of ηj, U(t0) and V(t0), which are all Gaussian random variables. Under the Euler approximation, [Uo, Vo ∣ θ0, ϕs] degenerates to ≺ Vo ∣ V(t0), ϕs ≻ because of equation (10), where ≺ · ∣ · ≻ denotes the approximate conditional density. Consequently, the likelihood based on the approximated processes U(t) and V(t) for t ∈

o, because they are linear combinations of ηj, U(t0) and V(t0), which are all Gaussian random variables. Under the Euler approximation, [Uo, Vo ∣ θ0, ϕs] degenerates to ≺ Vo ∣ V(t0), ϕs ≻ because of equation (10), where ≺ · ∣ · ≻ denotes the approximate conditional density. Consequently, the likelihood based on the approximated processes U(t) and V(t) for t ∈

o is given by

o is given by

where

and

3.2 Data augmentation

If observational time intervals are not short enough, the Euler approximation will not work well, because linear interpolation of V(t) and U(t) for t ∈

o is not accurate enough. A solution to reduce the approximation error is simply to add sufficiently dense virtual data in each time interval and consider the latent states at these times in addition to those at t ∈

o is not accurate enough. A solution to reduce the approximation error is simply to add sufficiently dense virtual data in each time interval and consider the latent states at these times in addition to those at t ∈

o. The corresponding values of Y(·) at added times can be regarded as missing data. They will be sampled as part of the MCMC scheme in the Bayesian analysis.

o. The corresponding values of Y(·) at added times can be regarded as missing data. They will be sampled as part of the MCMC scheme in the Bayesian analysis.

To carry out data augmentation, we add Mj equally spaced data at times tj−1,1, …, tj−1,Mj over a time interval (tj−1, tj]. Denote

. The resulting augmented index set is

ao = {tj,m : j = 0, 1, …, J, m = 0, 1, 2, …, Mj, MJ = 0}. Note that

ao = {tj,m : j = 0, 1, …, J, m = 0, 1, 2, …, Mj, MJ = 0}. Note that

ao =

ao =

o, if Mj = 0 for all j. The observed data and the augmented data are denoted by yo ≔ [y(t1,0), y(t2,0), …, y(tJ,0)]T and

, respectively, where ya,j ≔ [y(tj,1), y(tj,2), …, y(tj,Mj)]T. We also denote

where Vj ≔ [V(tj,0), V(tj,1), …, V(tj,Mj)]T. Similar notation is applied to U and Uj. For ease of exposition, we let yj,m ≔ y(tj,m), and similarly for other variables.

o, if Mj = 0 for all j. The observed data and the augmented data are denoted by yo ≔ [y(t1,0), y(t2,0), …, y(tJ,0)]T and

, respectively, where ya,j ≔ [y(tj,1), y(tj,2), …, y(tj,Mj)]T. We also denote

where Vj ≔ [V(tj,0), V(tj,1), …, V(tj,Mj)]T. Similar notation is applied to U and Uj. For ease of exposition, we let yj,m ≔ y(tj,m), and similarly for other variables.

If the exact transition densities exist, the augmented likelihood is

where

If the exact transition densities do not exist, the discretized versions of the ODE and the SDE are modified from t ∈

o to t ∈

o to t ∈

ao and given as follows:

ao and given as follows:

where t0,0 ≔ t0, tj−1,Mj+1 ≔ tj,0, and ηj−1,m ≔ W(tj−1,m) − W(tj−1,m−1) ∼

(0, δMj). The approximate transition density and the corresponding likelihood are given in Section 3.3.

(0, δMj). The approximate transition density and the corresponding likelihood are given in Section 3.3.

3.3 Bayesian inference

MCMC enables us to draw samples from the joint posterior [θ0, V, ϕo, ϕs ∣ yo] or [θ0, V, ϕo, ϕs, ya ∣ yo]. For the later case, we will augment Mj equally spaced data points between time interval (tj−1, tj]. To assess whether Mj is sufficiently large we suggest a sensitivity analysis in which Mj is increased until the parameter estimates are stable. An illustration of this is given in Section 4. We may also compare the trace plots of parameter estimates and DIC values for different Mj values to evaluate the numerical performance of MCMC and goodness-of-fit respectively.

MCMC draws samples from [θ0, V, ϕo, ϕs, ya ∣ yo] by iteratively simulating from each full conditional density of θ0, V, ϕo, ϕs, and ya. The joint posterior density is proportional to the product of the likelihood and prior densities:

where

and Vj−1,Mj+1 = Vj,0. The approximate transition density ≺ Vj−1,m ∣ Vj−1,m−1, ϕs ≻ with augmented data is given by,

and [θ0], [ϕs], [ϕo] are non-informative prior densities. See Web Appendix B for specification of the prior distr ibutions and details of MCMC algorithm. We use the simulation smoother(Durbin and Koopman, 2002) to achieve an efficient MCMC algorithm. In the simulation smoother, the latent states are recursively backward sampled in blocks instead of one state at a time. This leads to low autocorrelation between successive draws, and hence faster convergence.

3.4 Posterior forecasting with SVM

A desirable property of this approach is the ease of deriving forecasts of states at future times. To forecast the k-step future latent state given the observations yo, we simulate from the following posterior forecasting distribution,

where ya, ϕs and ϕo are drawn from [ya, ϕs, ϕo ∣ yo] by the MCMC algorithm. Given ya, ϕs and ϕo, we first discretize the SVM. For SVM-OU, this will lead to equations (B.3) and (B.4) in Web Appendix B. Let θJ denote the latent state of the last observation. Then,

(θJ) = aJ and

(θJ) = aJ and

ar(θJ) = RJ are obtained via the Kalman filter. Moreover, it follows from (B.4) that the mean and variance of

can be recursively obtained as follows:

ar(θJ) = RJ are obtained via the Kalman filter. Moreover, it follows from (B.4) that the mean and variance of

can be recursively obtained as follows:

where GJ+k−1 and ΣωJ+k−1 are specified in Web Appendix B for the SVM-OU and SVM-W, respectively. Finally, we draw from . By this way, the forecasts at future times take the variation of parameter draws into consideration.

4. Simulations

Using Euler approximation enables us to make inference for the SVMs with the analytically intractable exact transition densities. Although such flexibility seems to induce approximation errors, in practice these errors would be alleviated by applying the data augmentation. We are interested in assessing the performance of the estimation of the parameters, U(t) and V(t) as the number of data augmentation changes, so we simulate 100 replicate datasets from the SVM-OU with exact transition density (7). The parameters are chosen to be close to the ones estimated from a real dataset analyzed in the following section. Each dataset includes 40 observations, equally spaced with interval length 0.5. We fit each dataset by the SVM-OU, under the following three data augmentation schemes: (1) No augmentation; (2) one data point added in the middle of every two adjacent observations; and (3) three evenly spaced data points are inserted between every two adjacent observations. In all cases, MCMC is run for 45,000 iterations, in which the first 35,000 runs are discarded as the burn-in and every 10th draws are saved. Table 1 presents the Bias E(ϕ̃0.5 − ϕ), and mean squared error(MSE) E(ϕ̃0.5 − ϕ)2 of the posterior median ϕ̃0.5 for each parameter ϕ. These results indicate that the strategy of data augmentation, even for the single data point augmentation, would reduce estimation bias rate for variance parameter and drift parameter ρ. The estimations of other parameters and ν̄ are little affected by the data augmentation. As shown in Web Table 2, the data augmentation improves the estimation of U(t) and V(t) as well, indicated by the smaller average absolute Bias and average MSE of posterior means. We observed that the computation time of the proposed MCMC algorithm is proportional to the size of observed and augmented data, and thus the data augmentation would significantly increase the computation burden, which discourages us to add a massive number of augmented data. Those simulation results suggest that in practice we may add few augmented data and achieve accurate estimation.

Table 1. Simulation results for the estimation of SVM-OU parameters and stable rates. For data augmentation, 0, 1 and 3 data points are added between every two adjacent observations.

| No. Data points Augmented | Parameter | Truth | Bias | MSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

|

0.01 | -6.723E-04 | 1.590E-05 | |

|

|

0.2 | -9.837E-02 | 1.322E-02 | ||

| ρ | 1 | -1.863E-01 | 5.239E-02 | ||

| V̄ | 0.3 | -7.612E-03 | 1.297E-02 | ||

|

|

|||||

| 1 |

|

0.01 | 1.120E-04 | 1.521E-05 | |

|

|

0.2 | -6.089E-02 | 1.130E-02 | ||

| ρ | 1 | -6.426E-02 | 3.793E-02 | ||

| V̄ | 0.3 | -9.181E-03 | 1.304E-02 | ||

|

|

|||||

| 3 |

|

0.01 | 4.489E-04 | 1.611E-05 | |

|

|

0.2 | -3.905E-02 | 1.219E-02 | ||

| ρ | 1 | 8.856E-03 | 4.687E-02 | ||

| V̄ | 0.3 | -9.955E-03 | 1.284E-02 | ||

To compare, we analyze these simulated datasets by the SVM-W, and an ODE model, respectively. Note that the posterior mean in the SVM-W is equivalent to the smooth natural cubic spline. The ODE model used in the analysis satisfies the observation equation (1) for functional response, and the mean function U(·) is governed by the following two ODEs:

| (12) |

with boundary conditions U(t0) = β0 + β2 and V(t0) = β1 − β2β3 at t0 = 0. This formulation leads to a deterministic mean function U(t) = β0 + β1t + β2 exp(−β3t), which implies that ODE model is essentially a parametric nonlinear regression model. As shown in Table 2, the proposed SVM-OU model is superior to the ones from the other two models in the estimation of U(t) and V(t), when the SVM-OU model generates the data. We are also interested in exploring how the proposed methods perform when data are generated form other model different from the SVM-OU. For this, we further simulate another 100 replicate datasets from above the ODE model with β0 ∼

(−2.5, 0.01), β1 ∼

(−2.5, 0.01), β1 ∼

(0.3, 0.01), β2 ∼

(0.3, 0.01), β2 ∼

(9, 0.04), β3 ∼

(9, 0.04), β3 ∼

(1, 0.01) and σ2 = 0.04. The processes U(t) and V(t) are then estimated by the SVM-OU, SVM-W and ODE model, respectively. As shown Table 2 when data is generated from the ODE model, estimated U(t) and V(t) by the SVM-OU are close to those by the ODE model, and better than the SVM-W in terms of smaller average absolute bias and average MSE.

(1, 0.01) and σ2 = 0.04. The processes U(t) and V(t) are then estimated by the SVM-OU, SVM-W and ODE model, respectively. As shown Table 2 when data is generated from the ODE model, estimated U(t) and V(t) by the SVM-OU are close to those by the ODE model, and better than the SVM-W in terms of smaller average absolute bias and average MSE.

Table 2. Simulation results for the estimation of U(t) and V(t), when data simulated from SVM-OU and ODE model. For data augmentation, 0, 1 and 3 data points are added between every two adjacent observations.

| Simulation Model | Fitting Model | No. data points augmented | States | Bias | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM-OU | SVM-OU | 0 | U(t) | 0.008 | 0.005 |

| V(t) | 0.079 | 0.085 | |||

| SVM-OU | 1 | U(t) | 0.008 | 0.005 | |

| V(t) | 0.046 | 0.048 | |||

| SVM-OU | 3 | U(t) | 0.008 | 0.005 | |

| V(t) | 0.028 | 0.038 | |||

| SVM-WN | 0 | U(t) | 0.014 | 0.006 | |

| V(t) | 0.052 | 0.079 | |||

| ODE | 0 | U(t) | 0.051 | 0.099 | |

| V(t) | 0.054 | 0.133 | |||

|

|

|||||

| ODE | SVM-OU | 3 | U(t) | 0.043 | 0.026 |

| V(t) | 0.045 | 0.090 | |||

| SVM-WN | 0 | U(t) | 0.066 | 0.067 | |

| V(t) | 0.135 | 0.303 | |||

| ODE | 0 | U(t) | 0.030 | 0.018 | |

| V(t) | 0.020 | 0.018 | |||

In addtion to the above equally spaced data, we are also consider some other scenarios of datasets simulated from the SVM-OU, including: 1), the unequally spaced data resulted from uniform deletion of 15 data points from the original equally spaced data; 2), unbalanced and unequally spaced data resulted from uniform random deletion of 10 data points in the first half period (0,10] and of 5 data points in the second period (10,20] from the original equally spaced data simulated by the SVM-OU; 3), The data similar to the scenario 2) except with the reserved allocation of the unbalanced data points; 4) and 5), The 5-fold larger variance and 10 fold larger variance . Web Table 1 lists the summarized results of these five scenarios, regarding the estimation of U(t) and V(t) by the SVM-OU. The results from the first three scenarios indicate that the unbalance data distribution between the first and second half period times has different impact on the estimation of U(t) and V(t) in the average absolute bias and MSE. The second case with less data available in the first half time period is the worst. In the last two scenarios with increased measurement errors, the simulation results suggest that the estimation for U(t) and V(t) becomes a harder task.

5. Application

We now demonstrate an application where the diffusion models are used to investigate dynamic features of the PSA profile for a prostate cancer patient. We fit the SVM and SAM with the Wiener process and the OU process V(t), respectively. We also forecast the future profile of PSA for both models. The models are evaluated by the DIC model selection criterion(Speigelhalter et al., 2003). DIC = D̄ + PD, where D̄ is posterior mean of the deviance and PD is the effective number of parameters. DIC has been shown asymptotically to be a generalization of Akaikes information criterion(AIC). Similar to AIC, DIC trades off the model fitting by the model complex and can be easily computed from the MCMC output. The smaller the DIC value indicates better model-fitting. For each application, the posterior draws are from a 400, 000 iteration chain with 200, 000 burn-in, and every 100th draw is selected. Convergence was assessed by examination of trace plots and autocorrelation plots.

5.1 Prostate specific antigen

PSA is a biomarker used to monitor recurrence of prostate cancer after treatment with radiation therapy. When PSA remains low and its rate varying around zero with low volatility, the tumor is stable and the patient may be cured. If PSA increases dramatically with high rate, it is a strong sign of the tumor re-growing and that the treatment did not cure the patient. Therefore, PSA has strong prognostic significant and is important for making clinical decisions. We want to estimate dynamics of the PSA marker, including PSA level, rate and the volatility of rate. We analyzed the PSA profile of one patient using the SVM and SAM model to estimate PSA(t) nonparametrically. For these data illustrated in the introduction, the average time interval between two observations was 0.4 years with minimum 0.016 and maximum 0.731 years. We added 32 virtual data points to reduce the time span between any pairs of consecutive time points to less than 0.25 year.

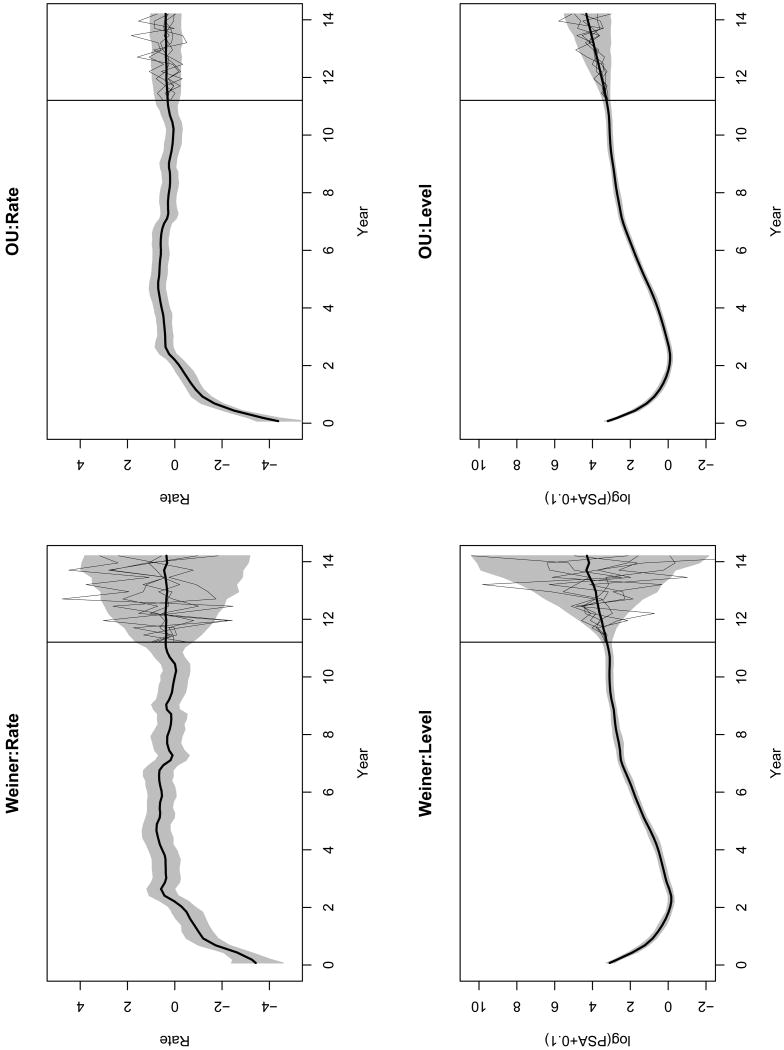

Table 3 and Web Table 2 shows the means and quantiles of the SVM and SAM parameters from the Wiener and the OU process V(t), respectively. Figure 2 and Web Figure 1 shows the posterior means and the corresponding 95% credible intervals of the latent states for SVM and SAMs. Here, the four models demonstrate similar trends of the PSA level. However, the rates in the SVMs fluctuates with higher volatility, compare to the SAMs. In addition, there are the non-zero instantaneous mean terms in the SVM-OU and SAM-OUs, whose rates evolve more stably than those in the models with Wiener process. The SVM-OU gives the smallest DIC, which indicates the best model fitting. In this model, the posterior mean of ν̄ is 0.385 with 95% credible interval [0.143, 0.626]. This stable and clearly positive rate after year 2.2 is a strong indicator of prostate cancer recurrence.

Table 3. PSA data: Posterior mean and quantiles for the SVMs.

| Wiener Process | OU Process | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D̄ = −45.1757, PD = 12.303, DIC = −32.873 | D̄ = −45.935, PD = 10.658, DIC = −35.277 | ||||||||||

| Mean | SD | 2.5% | 50% | 97.5% | Mean | SD | 2.5% | 50% | 97.5% | ||

|

|

0.014 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.036 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.024 | |

|

|

0.961 | 0.589 | 0.297 | 0.809 | 2.548 | 0.177 | 0.181 | 0.037 | 0.122 | 0.682 | |

| ν̄ | 0.385 | 0.124 | 0.143 | 0.382 | 0.626 | ||||||

| ρ | 1.150 | 0.271 | 0.756 | 1.106 | 1.798 | ||||||

Figure 2.

PSA posterior summary and forecasting: Plots of posterior means(—) and 95% credible intervals(gray shades) for the SVM with the Wiener process and OU process, respectively, till year 11.2. The future rates and levels are forecasted for the next 3 years, illustrated by the forecasting means (—) and 95% forecasting credible intervals(gray shades). The 5 randomly picked realizations for each plot are also illustrated.

Figure 2 illustrates the forecasting of the PSA latent states for the next 3 years, starting from year 11.2, by SVM-W and SVM-OU. The future states are sampled every 0.25 years and then linearly interpolated, from the posterior forecasting distribution given in Section 3.4. The SVM-OU gives a forecast with narrower credible intervals than the SVM-W. This result seems clinically more sensible, because several studies, including ours presented in Section 4.2, have found that the rate of PSA follows a stationary process. In contrast, a Wiener process corresponds to a nonstationary process for the rate of change of PSA, resulting in an unbounded variance of the forecast over time. This lacks relevant clinical interpretation. The comparison in the forecasts indicates that specification of the latent process is crucial for adequate forecasting, even though their estimates of the mean function are quite similar. A similar phenomenon has been reported by Taylor and Law (1998) in the linear mixed model of CD4 counts, where the covariance structure matters for individual level predictions, although it affects little the estimation of fixed effects.

6. Discussion

Diffusion type models are widely applied in areas such as finance, physics and ecology. However, other than through the connection with the smoothing spline, they have not played a major role in functional data analysis or nonparametric regression. In this paper we develop a framework that sheds light on more general diffusion models to be used in functional data analysis. Unlike in some applications where the form of the diffusion model is determined by the context, we specify a general form based on an ODE, a SDE and measurement error. The key advantage of the proposed diffusion model is that is addresses not only the mean function nonparametrically but also its dynamics, which are also of great interest in many application. Based on this model we adapt and develop existing ideas for estimation and inference for diffusion models. An additional attractive feature of this stochastic model approach to functional data analysis is that forecasting can be easily implemented.

As noted above, the SVM with the Wiener process corresponds to the smoothing spline with m = 2. If no augmented data are involved, the model can be rewritten as a linear mixed model for both situations of exact and approximate transition densities. As shown in the Web Appendix D, when data are equally spaced, the latter case is identical to a linear spline model with truncated line function basis (Ruppert et al., 2003). In this sense, the linear spline model can be regarded as a numerical approximation of the smoothing spline. In addition, with no data augmentation, one can easily fit the SVM with the Wiener process using existing software for the linear mixed model.

A number of extensions of the SVM and SAM are possible. Generalizing SVM and SAM to analyze discrete-valued outcomes is of interest. For the SVM, we have an explicit expression for the observation equation given by:

The observation equation can be expressed as,

| (13) |

where Φ(· ∣ UG, σG) is the normal CDF with mean UG and standard deviation σG. Then, (13) can be extended to,

where one specifies the corresponding observation distribution

in the exponential family, with state equations (2) and (3) unchanged.

in the exponential family, with state equations (2) and (3) unchanged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by National Cancer Institute grants CA110518 and CA69568. The authors are thankful to Dr. Naisysin Wang and Dr. Brisa Sanchez for the helpful discussions, and the editor, associate editor and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials: Web Appendices, Tables, and Figures referenced in Sections 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 are available under the Paper Information link at the Biometrics website http://www.biometrics.tibs.org.

References

- Aït-Sahalia Y. Maximum likelihood estimation of discretely sampled diffusions: a closed-form approximation approach. Econometrica. 2002;70:223–262. [Google Scholar]

- Beskos A, Papaspiliopoulos O, Roberts G, Fearnhead P. Exact and computationally efficient likelihood-based estimation for discretely observed diffusion processes (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 2006;68:333–382. [Google Scholar]

- Bouleau N, Lepingle D. Numerical Methods for Stochastic Process. New York: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cumberland W, Sykes Z. Weak convergence of an autoregressive process used in modeling population growth. Journal of Applied Probability. 1982;19:450–455. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin J, Koopman SJ. A simple and efficient simulation smoother for state space time series analysis. Biometrika. 2002;89:603–616. [Google Scholar]

- Durham G, Gallant A. Numerical techniques for maximum likelihood estimation of continuous-time diffusion processes. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics. 2002;20:297–338. [Google Scholar]

- Elerian O, Chib S, Shephard N. Likelihood inference for discretely observed non-linear diffusions. Econometrica. 2001;69:959–993. [Google Scholar]

- Eraker B. MCMC Analysis of Diffusion Models With Application to Finance. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics. 2001;19:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Feller W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Application. New York: Springer; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand AE, Smith AFM. Sampling-based approaches to calculating marginal densities. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1990;85:398–409. [Google Scholar]

- Geman S, Geman D. Stochastic relaxation, Gibbs distributions and the Bayesian restoration of images. Readings in Computer Vision: Issues, Problems, Principles, and Paradigms pages. 1987:564–584. doi: 10.1109/tpami.1984.4767596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks W, Richardson S, Spiegelhalter D. Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Green P, Silverman B. Nonparametric Regression and Generalized Linear Models. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmett G, Stirzaker D. Probability and Random Processes. Oxford: Oxford University press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ionides E, Breto C, King A. Inference for nonlinear dynamical systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2006;103:18438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603181103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazwinski A. Stochastic Processes and Filtering Theory. New York: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kimeldorf GS, Wahba G. A correspondence between bayesian estimation on stochastic processes and smoothing by splines. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1970;41:495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Kloeden P, Platen E. Numerical Solution of Stochastic Differential Equations. New York: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Wu H. Parameter estimation for differential equation models using a framework of measurement error in regression models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008;103:1570–1583. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Quintana F. Nonparametric Bayesian Data Analysis. Statistical Science. 2004;19:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AR. A new approach to maximum likelihood estimation for stochastic differential equations based on discrete observations. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1995;22:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Proust-Lima C, Taylor JMG, Williams S, Ankerst D, Liu N, Kestin L, Bae K, Sandler H. Determinants of change of prostate-specific antigen over time and its association with recurrence following external beam radiation therapy of prostate cancer in 5 large cohorts. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2008;72:782. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay J, Hooker G, Campbell D, Cao J. Parameter estimation for differential equations: a generalized smoothing approach. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 2007;69:741–796. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay J, Silverman B. Functional Data Analysis. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C, Williams C. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GO, Stramer O. On inference for partially observed nonlinear diffusion models using the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. Biometrika. 2001;88:603–621. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert D, Wand M, Carroll R. Semiparametric Regression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen H. Parametric inference for diffusion processes observed at discrete points in time: a survey. International Statistical Review. 2004;72:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Speigelhalter D, Best N, Carlin B, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 2003;64:583–616. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M, Wong W. The calculation of posterior distributions by data augmentation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82:528–540. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JMG, Law N. Does the covariance structure matter in longitudinal modelling for the prediction of future CD4 counts? Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:2381–2394. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981030)17:20<2381::aid-sim926>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenbeck G, Ornstein L. On the Theory of the Brownian Motion. Physical Review. 1930;36:823–841. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba G. Improper priors, spline smoothing and the problem of guarding against model errors in regression. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1978;40:364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba G. Spline Models for Observational Data. Society for Industrial Mathematics; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert H, Byrd H, Sidhu G. A stochastic framework for recursive computation of spline functions: Part ii, smoothing splines. J Optimization Theory and Applications. 1980;01:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. PhD thesis. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2010. Stochastic Dynamic Models for Functional Data. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.