Abstract

The selective modulation of transcription exerted by steroids depends upon recognition of signalling molecules by properly folded cytoplasmic receptors and their subsequent translocation into the nucleus. These events require a sequential and dynamic series of protein-protein interactions in order to fashion receptors that bind stably to steroids. Central to receptor maturation, therefore, are several molecular chaperones and their accessory proteins; Hsp70, Hsp40, and hip modulate the 3-dimensional conformation of steroid receptors, permitting reaction via hop with Hsp90, arguably the central protein in the process. Binding to Hsp90 leads to dissociation of some proteins from the receptor complex while others are recruited. Notably, p23 stabilizes receptors in a steroid binding state, and the immunophilins, principally CyP40 and Hsp56, arrive late in receptor complex assembly. In this review, the functions of molecular chaperones during steroid receptor maturation are explored, leading to a general mechanistic model indicative of chaperone cooperation in protein folding.

INTRODUCTION

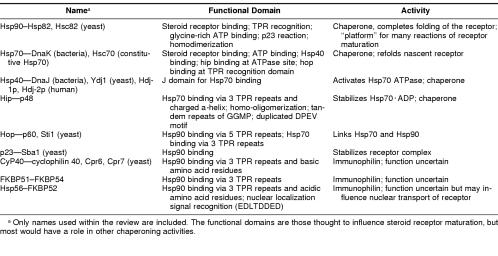

Molecular chaperones, many of which are heat shock proteins (Hsps), have several functions. They bind noncovalently to nascent and denaturing polypeptides, acting alone or in concert with other factors to promote protein folding, trafficking, multimer assembly, and signal transduction (Bukau et al 1996; Hartl 1996; Freeman et al 1996; Frydman and Höhfeld 1997; Liang and MacRae 1997; Chang et al 1997; Rassow et al 1997; Eggers et al 1997; Toft 1998; Bukau and Horwich 1998; Wang et al 1998; Kosano et al 1998; Xu et al 1999; Caplan 1999; Buchner 1999). Additionally, molecular chaperones are needed for maturation of steroid receptors, proteins that interact with steroid hormones and relay the information in these signaling molecules to the cell through transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Maturation requires the organization of molecular chaperones and associated proteins into multimeric complexes, often called heterocomplexes, that potentiate receptor interaction with steroids (Smith et al 1990; Smith and Toft 1993; Pratt and Welsh 1994; Rutherford and Zuker 1994; Chen et al 1996; Dittmar et al 1998; Kosano et al 1998). These proteins (Table 1) may either engage receptors singly or as multimers; there is a dynamic exchange of factors within complexes and they often act cooperatively, although not all are critical to maturation nor is the action of each protein known (Chen et al 1996; Dittmar et al 1998; Kosano et al 1998). Maturation of steroid receptors, therefore, provides an interesting opportunity for functional analysis of molecular chaperones. Recent advances in our understanding of steroid receptor maturation will be considered, relating where possible the characteristics of individual molecular chaperones and associated proteins with their time of entry into heterocomplexes. A model of receptor maturation is developed, and it is undoubtedly representative of chaperone cooperativity that occurs during folding of many proteins.

Table 1.

Equivalent names and important characteristics of proteins that function during steroid receptor maturation

Hsp90 is the central protein of the steroid receptor maturation pathway

The synthesis of Hsp90, recently proposed to influence the evolution of evolvability (Wagner et al 1999; Rutherford and Lindquist 1998), is either induced by stress or it is produced constitutively in physiologically normal cells. Hsp90 is an ATP-dependent molecular chaperone, although it can function without nucleotide (Panaretou et al 1998; Obermann et al 1998; Prodromou et al 1999, Grenert et al 1999), and it inhibits heat shock gene expression in Xenopus (Ali et al 1998), humans (Zou et al 1998) and yeast (Duina et al 1998) through interaction with the heat shock transcription factor, HSF1. This regulatory mechanism may also occur by way of Hsp70 (Ding et al 1998; Stephanou et al 1999; Schett et al 1999), and in yeast it involves Cpr7 (Duina et al 1998), a CyP-40-type immunophilin described in more detail later in this review. High resolution electron microscopic analysis of antibody-labeled specimens suggests that Hsp90 exists as a homodimer, formed by antiparallel linkage of monomers at their carboxy-terminal regions (Maruya et al 1999). Correspondingly, obstructing chicken Hsp90 dimerization by removing the carboxy-terminal amino acid residues 661–667 reduces its interaction with several accessory proteins (Chen et al 1998), a result that demonstrates the functional importance of dimerization. As determined by 2-hybrid screening and deletion mutagenesis, the dimerization region of mouse Hsp90 houses a TPR recognition domain (Carrello et al 1999) which recognizes degenerate consensus sequences of 34 amino acid residues, termed TPR sequences, found in accessory proteins. Specifically, CyP40, FKBP52 and hop bind competitively with a domain consisting of the carboxy-terminal 124 amino acid residues of murine Hsp90. Of this sequence, 4 residues at the extreme carboxy-terminus, EEVD, are essential to function of the TPR recognition domain. This may reflect a regulatory role for the EEVD motif.

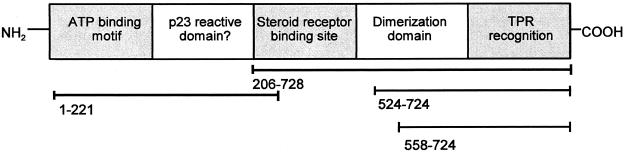

Hsp90 maintains client proteins in a folding competent condition in vitro without assistance from other chaperones (Freeman et al 1996; Bose et al 1996). In vivo, however, Hsp90 forms chaperone “machines,” protein complexes that interact with immature polypeptides, thereby promoting steroid receptor maturation and facilitating intracellular signal transduction (Freeman et al 1996; Fang et al 1996; Bose et al 1996; Grenert et al 1997; Nathan et al 1997; Dittmar and Pratt 1997; Scheibel et al 1998; Bohen 1998; Young et al 1998; Caamaño et al 1998; Dittmar et al 1998, 1997; Grenert et al 1999). In support of these ideas, reduced amounts of Hsp90 in yeast decrease glucocorticoid receptor activity (Picard et al 1990). Moreover, Hsp90 immunoadsorbed from cell-free extracts readily folds glucocorticoid receptors into a steroid reactive state but when the Hsp90 is washed with a salt-containing buffer, glucocorticoid receptor binding is lost (Scherrer et al 1992), suggesting the involvement of additional proteins in maturation. As is expected for a protein that interacts with other proteins, Hsp90 has multiple functional domains, some of which overlap. Among those identified are the dimerization region, a steroid receptor binding area, a carboxy-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) recognition domain enriched in acidic residues, a p23 reaction site, and an amino-terminal ATP binding motif containing several glycines (Fig 1) (Grenert et al 1997; Chen et al 1998; Kosano et al 1998; Prodromou et al 1999, 1997; Maruya et al 1999; Russell et al 1999a; Grenert et al 1999). The chaperone activity of Hsp90 is mediated by regions located in the N- (ATP dependent) and C-terminal regions and ATP-coupled Hsp90 may serve as a negative regulator of steroid receptor maturation because ATP/Hsp90 has low affinity for target proteins (Scheibel et al 1998). The role of the ATP-binding domain has been clarified using the antibiotics geldanamycin and radicicol, both of which interfere with Hsp90 function by interaction with the ATP-reactive site (Grenert et al 1997; Schulte et al 1999; Soga et al 1999).

Fig. 1.

Five functional domains of Hsp90 are known. These Hsp90 regions, not drawn to scale, are indicated separately in the figure but there is overlap among them. An amino terminal ATP binding motif rich in glycine occurs within amino-acids 1 to 221 and it may overlap a p23 reactive site, although this is uncertain. A carboxy terminal steroid receptor attachment site encompassed by residues 206–728 overlaps the Hsp90 dimerization region (residues 524–724) and the TPR recognition domain (residues 558–724)

Hsp90 recognizes steroid receptors at a region in its carboxy terminus (Shaknovich et al 1992; Leclerc et al 1998; Jibard et al 1999), 1 of 2 chaperone sites in the protein linked by a charged sequence that may modulate protein folding (Scheibel et al 1998, 1999). In turn, the steroid receptor binds with Hsp90 through a sequence of approximately 86 amino acid residues in its highly conserved hormone-binding domain. Within this area of the rat glucocorticoid receptor, Pro643 is necessary for effective coupling to occur (Caamaño et al 1998). Amino acid residues 547–553 of the rat glucocorticoid receptor, comprising the sequence TPTLVSL at the amino terminus of the hormone binding domain, are required for association with Hsp90 and steroid (Xu et al 1998). This observation prompted the notion that reaction of Hsp90 with TPTLVSL structurally modifies the hormone-binding domain of the receptor, allowing hydrophobic residues therein to be recognized by similar residues in Hsp90. The proposal is interesting because it implies that Hsp90 detects a discrete sequence within a target protein. In the more generally held view, Hsp90 recognizes exposed hydrophobic regions in partially folded polypeptides, without a requirement for specific amino acid residues. Perhaps the need for a defined sequence to initiate Hsp90·target binding is restricted to steroid hormone receptors. Additionally, Hsp90 may be required for maturation because steroid receptors are unstable, obligatorily changing conformation as they operate within the cell (Nathan et al 1997). In this view, Hsp90 maintains receptors in a structurally ephemeral state, suitable for the sequential series of reactions they undergo during maturation.

Hsp70 and its cochaperone Hsp40 function early in steroid receptor maturation

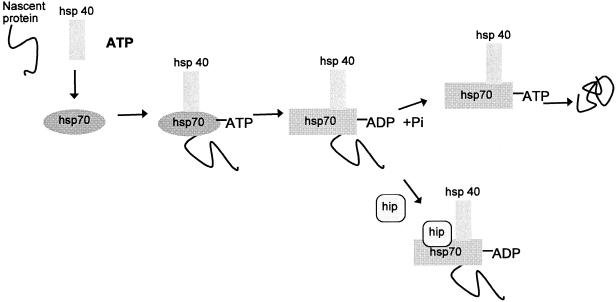

Immunoadsorption with an antibody specific to Hsp90 may yield Hsp70 (Scherrer et al 1992) and the interaction of Hsp90 with steroid receptors is inhibited by anti-Hsp70 antibodies (Smith and Toft 1993), suggesting that these proteins are functionally linked. Other reports indicate that Hsp70 binds steroid receptors prior to Hsp90 (Smith and Toft 1993; Prapapanich et al 1996a; Kosano et al 1998), showing the importance of the former early in receptor maturation. In some models, Hsp70 is the first chaperone to bind receptors, and it dissociates from the complex prior to, or concurrent with, hormone arrival (Smith 1993; Prapapanich et al 1996a, 1998), although it has been proposed that the amount of Hsp70 in the mature receptor complex varies with the experimental system under study (Dittmar et al 1998). Whatever the details, a preliminary role for Hsp70 in receptor maturation is clear and this agrees with its mechanism of action as a molecular chaperone (Fig 2) (Kimura et al 1995; Rassow et al 1997; James et al 1997; Demand et al 1998; Pierpaoli et al 1998; Lu and Cyr 1998a; Kelley 1998; Green et al 1998; Pfund et al 1998; Bukau and Horwich 1998; Wang et al 1998; Johnson and McKay 1999; Morshauser et al 1999). That is, members of the Hsp70 family bind nascent proteins in an ATP-dependent process, maintaining them in a folding competent form. For this to occur, Hsp70 engages ATP at its amino-terminus. Hsp70 then recognizes hydrophobic segments of unfolded polypeptides by way of an 18 kDa fragment on the carboxy side of the ATP binding region in a reaction that is partly stabilized by the 10 kDa carboxy-terminal domain of Hsp70 and the bound peptide. Hydrophobic interactions may be promoted by ionic linkages occurring as a consequence of conserved clusters of charged amino acid residues in Hsp70-type chaperones (Karlin and Brocchieri 1998). In conjunction with ATP hydrolysis, Hsp70 undergoes a conformational change; the substrate protein is released and folded upon exchange of ADP for ATP. Nucleotide hydrolysis by Hsp70, and thus protein folding, are modulated through binding of both client protein and Hsp40, the latter equivalent to DnaJ from bacteria (Lopez-Buesa et al 1998; Misselwitz et al 1998; Russell et al 1999b; Davis et al 1999; Laufen et al 1999; Mayer et al 1999; King et al 1999).

Fig. 2.

Preliminary role of Hsp70 in protein folding and steroid receptor maturation. Nascent proteins, including steroid receptors, are bound by Hsp70·ATP. Upon nucleotide hydrolysis, stimulated by the J-domain of Hsp40, the chaperone undergoes a conformational change. Partially folded proteins are released upon exchange of ADP for ATP on Hsp70, and they may react with other chaperones. However, for steroid receptors, hip prevents release of ADP. This increases the time a partially folded receptor associates with Hsp70 and enhances its interaction with Hsp90 in the next step of maturation.

Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp40, and other proteins associate with steroid receptors prior to their maturation (Dittmar et al 1998). To examine the role of Hsp40 in intermediate complexes, mutant yeast were constructed wherein a highly conserved carboxy-terminal glycine at position 315 in Ydj1 (yeast equivalent of Hsp40) was changed to aspartic acid (Kimura et al 1995). Glucocorticoid receptor activity in these strains, as measured by expression of a lacZ reporter gene, increased about 200-fold in the absence of hormone, and binding of mutated Ydj1 to glucocorticoid receptor complexes decreased. Because the Ydj1 mutant phenotype is specific for Hsp90 substrates, and similar effects occur when Hsp90 is prevented from interacting with steroid receptors, the results suggest that Ydj1 is required for Hsp90 association with receptors. However, using a rapid recovery chromatographic procedure, only a small amount of histidine tagged Hsp90 and Ydj1 was shown to coexist in a stable complex (Kimura et al 1995). Therefore, Ydj1 may bind glucocorticoid receptors rather than Hsp90, and this may be essential for their function. If structural conformation is only partially established when receptors first combine with chaperones, the carboxyl domain of Ydj1 could assist in recognition of unfolded receptors (Lu and Cyr 1998a, 1998b). In this context it has been proposed that Ydj1 supports luciferase folding by Ssa1, a yeast homologue of Hsp70, better than the analogous protein Sis1 because Ydj1 has a zinc finger domain that is lacking in Sis1 (Lu and Cyr 1998b). In contrast, Nagata et al 1998, failed to demonstrate coupling of either Hdj-1p or Hdj-2p, mammalian cytosolic homologues of Hsp40, to nascent polypeptides. Their findings agreed with those of Eggers et al 1997. These contradictory conclusions are difficult to reconcile, but could have arisen either through employment of different experimental techniques, functional heterogeneity within the Hsp40 family, or because glucocorticoid receptor maturation is not generally representative of other Hsp40-dependent chaperone processes. As a final mechanistic consideration, the interaction of Hdj-1p with Hsp70 is transient and it forms unstable complexes with target proteins (Nagata et al 1998). This reinforces models of maturation wherein Hsp40 activates Hsp70 ATPase, perhaps influencing substrate specificity at the same time (Misselwitz et al 1998; Russell et al 1999b; Laufen et al 1999; Mayer et al 1999), and then it is lost from chaperone complexes when the latter departs.

Hip and hop, transient cochaperones in receptor maturation

Hsp70 binds an accessory protein termed hip (Hsc70-interacting protein) (Smith 1993) which has an ATP independent chaperone activity able to discern nonnative proteins and curtail their aggregation in vitro (Höhfeld et al 1995). Hip has a molecular mass of approximately 42 kDa, although migration in SDS polyacrylamide gels produces a value closer to 48 kDa, a property attributed to amino acid residues 50–100 in human hip (Prapapanich et al 1996a). This protein is widely distributed in mammalian tissues, as demonstrated by western and northern blotting, but search of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae data base failed to disclose a hip homologue (Höhfeld et al 1995; Frydman and Höhfeld 1997; Prapapanich et al 1996a, 1998). Either hip is inessential in yeast or its role is performed by a dissimilar protein. Cloning and sequencing revealed a homo-oligomerization domain at the extreme amino terminus of hip, multiple imperfect tandem repeats of a GGMP consensus sequence perhaps recognized by the peptide binding site of Hsp70, and a duplicated DPEV motif at its carboxy terminus. Three consecutive TPR repeats are positioned at the amino terminus of hip and they interact with Hsp70, although the association of these 2 proteins is primarily dependent on the adjacent positively charged α-helix that follows the repeats (Höhfeld et al 1995; Frydman and Höfeld 1997; Irmer and Höhfeld 1997; Prapapanich et al 1996a, 1996b; 1998). Several chaperone-associated proteins possess TPR regions and they may permit sequential exchange of factors during chaperone-mediated folding of protein substrates such as the steroid receptors (Frydman and Höhfeld 1997; Irmer and Höhfeld 1997).

Hip interacts transiently at the ATPase domain of Hsp70 when Hsp40 is also bound to the chaperone, but hip and Hsp40 remain separate (Prapapanich et al 1996b; Irmer and Höhfeld 1997). Binding between Hsp70 and hip is disrupted by ATP, elevated salt concentrations, and a group of competitive antagonistic effectors known as BAG proteins, which influence cell response to glucocorticoids (Kullmann et al 1998; Takayama et al 1999). These proteins occur in phylogenetically distant organisms and they contain a conserved carboxy-terminal sequence of about 45 amino acid residues called the BAG domain (Gebauer et al 1998; Dolinski et al 1998; Takayama et al 1999). BAG proteins bind to the ATPase site of Hsp70, and when in this position they inhibit protein folding, seemingly by preventing the ATP-dependent release of substrate from the chaperone (Bimston et al 1998). Bag proteins have also been shown to down-regulate transactivation by the liganded glucocorticoid receptor, a nuclear function dependent on the motif (EEX4) which is repeated 8 times (Schneikert et al 1999). The relative importance of BAG proteins in steroid receptor maturation is uncertain, but this may soon be resolved as more attention is given to these modulators of Hsp70 action.

Hip prevents the dissociation of ADP from Hsp70, and because Hsp70·ADP binds substrate more stably than does Hsp70·ATP, the interaction of steroid receptors with Hsp90 is enhanced if hip is present (Fig 2) (Höhfeld et al 1995; Irmer and Höhfeld 1997; Frydman and Höhfeld 1997). Thus, hip facilitates intermediate complex formation and it is found in association with Hsp90, hop, and steroid receptors, but not in mature receptor complexes (Höhfeld et al 1995; Prapapanich et al 1996a, 1996b; Chen et al 1998). In support of an early role, mutations to hip prevent progesterone receptor interaction with Hsp90 and hop; that is, they inhibit the formation of intermediate complexes (Prapapanich et al 1998). For example, in rabbit reticulocyte lysate containing hip with both of its DPEV sequences modified to APAV, Hsp90 in progesterone receptor complexes decreases to background while Hsp70 increases (Prapapanich et al 1998). It was proposed that hip allows hop (described next) to engage with Hsp70 in the presence of substrate, leading to intermediate complex formation. However, a recent report states that hip is not required in vitro to maintain hormone binding by receptors, although it should be noted that the proteins used in these assays were not completely pure (Kosano et al 1998).

Based on immunoadsorption experiments (Owens-Grillo et al 1996), the reaction between Hsp90 and Hsp70 depends upon hop, an idea consistent with the observation that each of these chaperones recognizes this protein (Smith et al 1993; Chen et al 1996). Moreover, immunoprecipitation from several cell-free systems, including reticulocyte lysate supplemented with salt-stripped progesterone receptors, shows that an intermediate complex composed of Hsp90, Hsp70 and hop assembles before receptors mature (Smith et al 1993; Smith 1993). In related work, the interaction between Sti1 (yeast homologue of hop) and Hsp82 (yeast homologue of Hsp90) was examined by gene deletion studies (Chang et al 1997). Loss of Sti1 was not lethal, but it increased the amount of glucocorticoid receptor bound to Ydj1 (yeast homologue of Hsp40), suggesting an early role for hop in receptor maturation. Furthermore, Sti1 did not immunoprecipitate with Hsp90-associated immunophilins, a group of proteins discussed later in more detail. A collective interpretation of these data is that Sti1 has a transient function, a possibility supported by the work of Nair et al 1997, who describe a temporary association of hop with intermediate steroid receptor complexes.

The 3 copies of the TPR motif in hop that combine with Hsp70 are located within an amino-terminus α-helical site encompassing residues 480–640 (Ratajczak and Carrello 1996; Owens-Grillo et al 1996; Duina et al 1996; Chen et al 1996; Frydman and Höhfeld 1997; Gebauer et al 1998). The union of hop and Hsp70 is sterically hindered by mammalian Hap46, a BAG protein homologue that joins with the amino-terminal ATPase site of Hsp70, a region well separated from the hop binding domain (Gebauer et al 1998). On the other hand, 5 to 8 centrally located TPR sequences in hop are recognized by the carboxy-terminal domain of Hsp90 (Chen et al 1996; Young et al 1998; Carrello et al 1999), a reaction reduced by ATP binding to Hsp90 (Grenert et al 1999). The presence of 2 TPR motifs implies that hop, a protein lacking chaperone activity in vitro (Freeman et al 1996; Bose et al 1996), mediates receptor maturation by linking Hsp90 and Hsp70, a conclusion corroborated by the proposed role of hop in the folding of other target proteins (Bose et al 1996; Freeman et al 1996; Johnson et al 1998). To further test this possibility, the TPR domains of hop that respectively bind Hsp70 and Hsp90 were individually mutated (Chen and Smith 1998). Although the mutated hop failed to react with either chaperone in reticulocyte lysate, only Hsp90 association with progesterone receptor was prevented, indicating that hop integrates the activities of Hsp70 and Hsp90 once the receptor has bound Hsp70. Furthermore, Sti1 is a dimer in solution and it is likely to complex with Hsp90 in this form, thus occupying both TPR-recognition sites in an Hsp90 dimer (Rutherford and Zuker 1994). Attachment of Sti1 changes Hsp90 conformation and inhibits its ATPase in a manner reversed by Cpr6, a yeast immunophilin. Titration of Hsp90-Sti1 complexes with geldanamycin indicates that Sti1 blocks access of ATP to Hsp90, perhaps through direct interaction with the nucleotide binding site (Prodromou et al 1999). Displacement of Sti1 by Cpr6 thus allows ATP binding, which is important for the attachment of cochaperones such as p23 to Hsp90. Additionally, hydrolysis of the attached nucleotide is required for the folding of client proteins in mature complexes and their subsequent release. Thus, during polypeptide folding, Sti1 links Hsp70 and Hsp90, while influencing the ATPase activity of the latter chaperone such that it acts at the appropriate time during steroid receptor maturation.

p23 stabilizes receptor-chaperone complexes

Several different proteins are recovered when progesterone receptors in chick oviduct extract are purified with receptor-specific antibodies coupled to agarose (Smith et al 1990; Smith 1993). Among them is p23, which separates from receptors in a salt-dependent manner inhibited by molybdate. These findings represent the first time p23 was observed as part of a receptor complex, and subsequent immunological analyses disclosed relatively constant amounts of the protein in tissues from several organisms (Johnson et al 1994). Antibodies to p23 coprecipitated progesterone receptor, Hsp90 and Hsp70, a confirmation of results obtained with antireceptor antibodies (Johnson et al 1994). A cDNA for human p23 was characterized, yielding a deduced sequence of 160 amino acid residues enriched in aspartic acid at its carboxy terminus and 96.3% similar to this protein from chicken. p23 was shown, as a consequence of these studies, to be a highly acidic phosphoprotein lacking similarity to other known proteins (Johnson et al 1994).

A complex of Hsp90, immunophilins and p23 forms in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the absence of steroid receptors, and these proteins also associate with receptors in a p23-dependent reaction (Johnson and Toft 1994, 1995). Construction of p23-containing complexes in reticulocyte lysate, either possessing or lacking progesterone receptors, is sensitive to geldanamycin. Similarly, p23 does not interact with Hsp90 in yeast exposed to geldanamycin. Under these conditions glucocorticoid receptors fail to activate gene expression initially suggesting that p23 is required for receptor function, a possibility that was subsequently disproved (Bohen 1998). Of significance to assembly dynamics, immunoadsorption from rabbit reticulocyte lysate with antibody to hop can yield a minimal complex without p23, indicating the latter functions at an intermediate stage in receptor maturation (Johnson and Toft 1994, 1995). In later work, however, Owens-Grillo et al 1996, demonstrated that Hsp70, hop, Hsp56, CyP40, and p23 coprecipitate with Hsp90. It turns out that there is a site in Hsp90 for recognition of p23, and high affinity binding of p23 relies upon an ATP-induced conformational change in Hsp90 (Grenert et al 1999). Release of p23 depends on ATP hydrolysis (Johnson and Toft 1995; Prodromou et al 1997; Fang et al 1998; Scheibel et al 1998; Obermann et al 1998).

Other in vitro studies with rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Dittmar et al 1997, 1998; Dittmar and Pratt 1997) and with partially purified components (Kosano et al 1998) reveal that steroid-reactive glucocorticoid receptor·Hsp90 complexes assemble in the presence of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp40, hop, and p23. As part of this process, all of these factors except p23 organize into “foldosomes,” protein composites that convert receptors into the steroid-binding form by a mechanism dependent on ATP and K+. The foldosome is somewhat of a functional concept, a protein assemblage varying in composition as associated receptors mature. As such, the idea of a foldosome can be misleading if understood solely as a specific assembly of proteins, but it is very useful as a visualization of chaperone action. Glucocorticoid receptor·Hsp90 complexes formed by foldosome action dissociate quickly unless p23 is present to prevent loss of the steroid recognition site. Stabilization occurs in an ATP-independent, dynamic fashion, but p23 is not absolutely required for maturation of steroid receptors. Consistent with this conclusion, genetic studies show that signaling proteins dependent on Hsp90 to attain their final conformation fold correctly when Sba1, the yeast equivalent of p23 (also called yhp23) is absent (Bohen 1998; Fang et al 1998). A recent examination of the estrogen receptor in S cerevisiae extends these observations, indicating the presence of p23-independent and p23-dependent signal transduction pathways, the latter favored at low concentrations of estrogen receptor and estradiol (Knoblauch and Garabedian 1999).

To summarize, receptors competent to bind steroids arise independent of p23, but it seems that p23 stabilizes heterocomplexes. Energy requirements relative to these functions require clarification because ATP, essential for binding of purified Hsp90 and p23, is not needed if Hsp90 is associated with a steroid receptor. Interestingly, p23 operates as an ATP-independent molecular chaperone (Freeman et al 1996; Bose et al 1996); it slows the inactivation of target proteins in vitro and may combine transiently with intermediates early in unfolding. The relationship, if any, between chaperone activity and stabilization of receptor complexes remains a potentially fruitful avenue for the study of p23 during maturation.

The immunophilins are constituents of mature steroid receptor complexes

The 2 major types of immunophilins, Hsp56 (FKBP52) and CyP40, are ubiquitous, highly conserved proteins that possess peptidylprolyl isomerase activity and engage immunosuppressive drugs. Representatives of the former, about 56 kDa in mass, comprise the FK506 and rapamycin binding class of immunophilins; the latter, with a molecular mass of 40 kDa, are cyclosporin A reactive. The immunophilins have weak affinity for receptor complexes, such that NaCl extraction and competition with CyP40 fragments housing 3 TPR repeats remove Hsp56, while Hsp90 and Hsp70 stay in place (Owens-Grillo et al 1995, 1996; Nair et al 1997). Attachment of Hsp56 and CyP40 to the carboxy terminus of Hsp90 is mediated by TPR domains and the union of immunophilins with receptor complexes is strengthened by molybdate (Owens-Grillo et al 1995, 1996; Young et al 1998; Carrello et al 1999). Additionally, charged residues at the carboxy and amino ends of CyP40 and Hsp56, respectively, stabilize immunophilin interaction with Hsp90 (Ratajczak and Carrello 1996).

CyP40 associates less effectively than Hsp56 with the glucocorticoid receptor·Hsp90 complex, yielding assemblages with either one or the other type of immunophilin, but not both (Owens-Grillo et al 1995, 1996; Ratajczak and Carrello 1996). Why a particular immunophilin occurs in a complex, and the physiological consequences of this differentiation, are uncertain. For example, because rabbit CyP40 binds more weakly to glucocorticoid receptor·Hsp90 complexes than does Hsp56, and is therefore present in small amounts, its role in receptor maturation has been questioned (Owens-Grillo et al 1996). On the other hand, genetic evidence indicates that a yeast CyP40-type immunophilin, termed Cpr7, operates during Hsp90-dependent steroid receptor signal transduction (Duina et al 1996). This was the first clear evidence that immunophilins of the CyP40 class mediate steroid receptor maturation, and because there is mechanistic conservation across phylogenetic boundaries, these immunophilins may have the same role in mammals. One interesting twist has arisen from characterization of FKBP51 (previously FKBP54) (Nair et al 1997), a human immunophilin with a deduced amino acid sequence 55% identical to human Hsp56. In a reconstituted system, FKBP51 and Hsp56 react equally well with Hsp90, but in cell-free extracts, progesterone receptor complexes bind FKBP51 preferentially. Moreover, the reduced binding of hormone to squirrel monkey glucocorticoid receptor is a consequence of increased intracellular amounts of FKBP51 and its preferential association, as compared to FKBP52, with Hsp90 (Reynolds et al 1999). These data demonstrate the potential for competition in vivo between similar immunophilins for target proteins.

In another development, effects arising from the loss of Cpr7 in S cerevisiae were suppressed by a protein termed Cns1 (Marsh et al 1998; Dolinski et al 1998). The severe reduction in cell growth experienced when Cpr7 was eliminated, especially in conjunction with deletion of either Hsc82 or Sti1, disappeared upon synthesis of Cns1. Of equal relevance, Cns1 restored glucocorticoid receptor function in yeast lacking Cpr7, presumably binding to Hsp90, which exhibits Cpr7-dependent chaperone activity. Cns1 has homology to Sti1, the yeast equivalent to hop, and it contains 3 critical TPR motifs (Marsh et al 1998; Dolinski et al 1998). The sequence similarities suggest that the actions of Cns1 and Sti1 overlap, explaining why yeast Sti1 is a dispensable protein. Indeed, Dolinski et al 1998, make the observation that several components in the yeast Hsp90 chaperone complex are duplicated. One protein in each pair is nonessential and heat inducible (Hsp82, Cpr6, Sti1), while the second protein is expressed constitutively and acts during normal growth (Hsc82, Cpr7, Cns1). When considered in this regard, some Hsp90 associated proteins perform under regular physiological conditions, whereas others are required in cells experiencing stress. Whether these subtle differences are detectable with the contemporary biochemical and genetic approaches employed to study receptor maturation is problematic, making incorrect functional assignment of chaperones during polypeptide folding a possibility.

What is the role of immunophilins in receptor maturation? They are unlikely to be necessary for either heterocomplex assembly or folding of the receptor hormone binding domain (Czar et al 1995), although both Hsp56 and CyP40 have chaperone action in vitro independent of peptidylprolyl isomerase (Freeman et al 1996; Bose et al 1996). Steroid receptor maturation also occurs in the absence of peptidylprolyl activity (Owens-Grillo et al 1995). As an alternative, movement of steroid receptor complexes into nuclei may require immunophilins (Pratt and Welsh 1994; Czar et al 1995), but this is controversial (Nair et al 1997). Steroid receptors contain a positively charged nuclear localization signal of 8 amino acid residues (RKTKKKIK), and Hsp56 has a negatively charged complementary sequence (EDLTDDED). In a mechanism distinct from TPR-dependent Hsp90 binding, these sites may interact with one another, allowing Hsp56 to behave as a nuclear localization signal recognition protein (Owens-Grillo et al 1996; Nair et al 1997). Supporting this possibility, antibodies directed against the negatively charged amino-acid motif of Hsp56 prevent glucocorticoid receptor movement into the nucleus, a result obtained by localization of fluorescently tagged receptors. Conversely, inhibition of peptidylprolyl isomerase activity does not affect nuclear translocation, indicating this enzyme action is superfluous to receptor localization (Czar et al 1995). In addition, much of the Hsp56 in cells localizes to nuclei, while the remainder is predominately associated with microtubules and the molecular motor dynein, consistent with the idea that immunophilins influence receptor movement (Czar et al 1994, 1995; Owens-Grillo et al 1996). Perhaps interaction with microtubules in the presence of hormone heralds a change in heterocomplexes from chaperoning structures to “transportosomes.” However, disruption of microtubules and microfilaments with colcemid and cytochalasin, respectively, has no effect on the partitioning of glucocorticoid receptors (Czar et al 1995), indicating the need for more investigation of this process.

A model of chaperone function during steroid receptor maturation

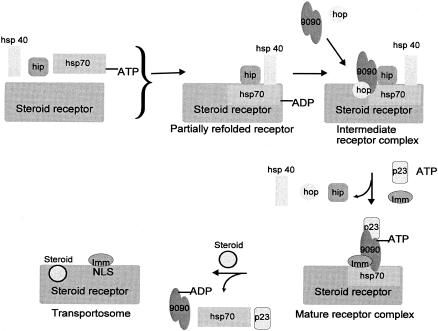

Maturation of steroid receptors is a dynamic, highly cooperative series of events and several models, differing in detail but fundamentally similar, have evolved to describe this process. The model we develop (Fig 3), has somewhat more emphasis on chaperone function than many previous models. However, like other models, it is influenced by the strengths and limitations of available data. For example, chaperones from mammals and yeast vary, even though these proteins are often interchangeable; thus information gained through work on one organism may not be completely representative of others. Several steroid receptors have been described and heterocomplex proteins may interact distinctly with each type, a difference amplified by the disparate quantities of molecular chaperones within cells. Results also vary when diverse experimental approaches are used to study steroid receptors from the same or similar organisms. For example, receptor heterocomplexes formed in rabbit reticulocyte lysate are not necessarily identical in composition and function to those reconstituted with purified proteins from the same source. Additionally, preparations of purified chaperones may include contaminating proteins that are difficult to detect, but sufficient in amount to confound experimental data. Another major consideration is nonspecific protein-protein binding; there is an absolute need to determine which of the reactions between chaperones, associated proteins, and receptors are physiologically significant, especially because many of these proteins are duplicated. Furthermore, there is a tendency in some reports to assume that all coprecipitating proteins are bound directly to the chaperone under study, but this is not always true. In spite of these problems, important steps on the path to understanding steroid receptor maturation have been achieved. Molecular chaperones and their associated proteins are clearly critical for steroid receptor activity, and while not all identified complex components are absolutely necessary for maturation, having the full complement of factors enhances efficiency. Moreover, mechanistic events of steroid receptor maturation undoubtedly apply to other proteins whose folding and translocation depend upon molecular chaperones, demonstrating the fundamental significance of these processes in the cell and the importance of their characterization.

Fig. 3.

A generalized model of mammalian steroid receptor maturation. Hsp70·ATP binds the nascent steroid receptor, nucleotide hydrolysis is promoted by the J-domain of Hsp40, and the steroid receptor is partially folded. The attachment of hip prevents release of ADP and the receptor from Hsp70. Cytosolic dimers of Hsp90 and hop join the Hsp70·Hsp40·hip·receptor complex to form an intermediate receptor complex. Hsp90 recognizes the steroid receptor hormone binding domain and also interacts with hop through its TPR recognition domain. Hop links Hsp90 to the Hsp70 complex. Hsp40, hip and hop are transient components of the receptor complex and dissociate prior to or concurrent with binding of p23 to Hsp90 which stabilizes the complex. ATP binds Hsp90 late in steroid receptor maturation and may be hydrolyzed. Dissociation of hop frees the TPR recognition domain of Hsp90 and allows association with either of the immunophilins, Hsp56 or CyP40. The role of the immunophilins is uncertain, but Hsp56 may react with the nuclear localization sequence on the steroid receptor, stimulating transport into the nucleus and subsequent activation of transcription. Steroid binding triggers the release of Hsp90, Hsp70 and p23, although some Hsp70 may remain. Imm, immunophilin

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Grant to T.H. MacRae.

REFERENCES

- Ali A, Bharadwaj S, O'Carroll R, Ovsenek N. HSP90 interacts with and regulates the activity of heat shock factor 1 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4949–4960. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimston D, Song J, Winchester D, Takayama S, Reed JC, Morimoto RI. BAG-1, anegative regulator of hsp70 chaperone activity, uncouples nucleotide hydrolysis from substrate release. EMBO J. 1998;17:6871–6878. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohen SP. Genetic and biochemical analysis of p23 and ansamycin antibiotics in the function of Hsp90-dependent signaling proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3330–3339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S, Weikl T, Bügl H, Buchner J. Chaperone function of Hsp90-associated proteins. Science. 1996;274:1715–1717. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner J. Hsp90 & Co.—a holding for folding. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Hesterkamp T, Luirink J. Growing up in a dangerous environment: a network of multiple targeting and folding pathways for nascent polypeptides in the cytosol. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:480–486. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)84946-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caamaño CA, Morano MI, Dalman FC, Pratt WB, Akil H. A conserved proline in the hsp90 binding region of the glucocorticoid receptor is required for hsp90 heterocomplex stabilization and receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20473–20480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AJ. Hsp90‘s secrets unfold: new insights from structural and functional studies. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:262–268. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrello A, Ingley E, Minchin RF, Tsai S, Ratajczak T. The common tetratricopeptide repeat acceptor site for steroid receptor-associated immunophilins and hop is located in the dimerization domain of Hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2682–2689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H-CJ, Nathan DF, Lindquist S. In vivo analysis of the Hsp90 cochaperone Sti1 (p60) Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:318–325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Smith DF. Hop as an adaptor in the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and Hsp90 chaperone machinery. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35194–35200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Sullivan WP, Toft DO, Smith DF. Differential interactions of p23 and the TPR-containing proteins Hop, Cyp40, FKBP52and FKBP51 with Hsp90 mutants. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:118–129. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0118:diopat>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Prapapanich V, Rimerman RA, Honoré B, Smith DF. Interactions of p60, amediator of progesterone receptor assembly, with heat shock proteins hsp90 and hsp70. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:682–693. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.6.8776728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czar MJ, Lyons RH, Welsh MJ, Renoir JM, Pratt WB. Evidence thagt the FK506-binding immunophilin heat shock protein 56 is required for trafficking of the glucocorticoid receptor from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1549–1560. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.11.8584032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czar MJ, Owens-Grillo JK, Yem AW, Leach KL, Deibel MR Jr, Welsh MJ, Pratt WB. The hsp56 immunophilin component of untransformed steroid receptor complexes is localized both to microtubules in the cytoplasm and to the same nonrandom regions within the nucleus as the steroid receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:1731–1741. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.12.7708060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JE, Voisine C, Craig EA. Intragenic suppressors of Hsp70 mutants: interplay between the ATPase- and peptide-binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9269–9276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demand J, Lüders J, Höhfeld J. The carboxy-terminal domain of Hsc70 provides binding sites for a distinct set of chaperone cofactors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2023–2028. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XZ, Tsokos GC, Kiang JG. Overexpression of HSP-70 inhibits the phosphorylation of HSF1 by activating protein phosphatase and inhibiting protein kinase C activity. FASEB J. 1998;12:451–459. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Banach M, Galigniana MD, Pratt WB. The role of DnaJ-like proteins in glucocorticoid receptor.hsp90 heterocomplex assembly by the reconstituted hsp90.p60.hsp70 foldosome complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7358–7366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Demady DR, Stancato LF, Krishna P, Pratt WB. Folding of the glucocorticoid receptor by the heat shock protein (hsp) 90-based chaperone machinery. The role of p23 is to stabilize receptor.hsp90 heterocomplexes formed by hsp90.p60.hsp70. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21213–21220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Pratt WB. Folding of the glucocorticoid receptor by the reconstituted hsp90-based chaperone machinery. The initial hsp90.p60.hsp70-dependent step is sufficient for creating the steroid binding conformation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13047–13054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinski KJ, Cardenas ME, Heitman J. CNS1 encodes an essential p60/Sti1 homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that suppresses cyclophilin 40 mutations and interacts with Hsp90. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7344–7352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duina AA, Kalton HM, Gaber RF. Requirement for Hsp90 and a CyP-40-type cyclophilin in negative regulation of the heat shock response. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18974–18978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duina AA, Chang HC, Marsh JA, Lindquist S, Gaber RF. A cyclophilin function in Hsp90-dependent signal transduction. Science. 1996;274:1713–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers DK, Welch WJ, Hansen WJ. Complexes between nascent polypeptides and their molecular chaperones in the cytosol of mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1559–1573. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Fliss AE, Rao J, Caplan AJ. SBA1 encodes a yeast Hsp90 cochaperone that is homologous to vertebrate p23 proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3727–3734. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Fliss AE, Robins DM, Caplan AJ. Hsp90 regulates androgen receptor hormone binding affinity in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28697–28702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BC, Toft DO, Morimoto RI. Molecular chaperone machines: chaperone activities of the cyclophilin Cyp-40 and the steroid aporeceptor-associated protein p23. Science. 1996;274:1718–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J, Höhfeld J. Chaperones get in touch: the Hip-Hop connection. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer M, Zeiner M, Gehring U. Interference between proteins Hap46 and Hop/p60, which bind to different domains of the molecular chaperone hsp70/hsc70. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6238–6244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MK, Maskos K, Landry SJ. Role of the J-domain in the cooperation of Hsp40 and Hsp70. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenert JP, Johnson BD, Toft DO. The importance of ATP binding and hydrolysis by Hsp90 in formation and function of protein heterocomplexes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17525–17533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenert JP, Sullivan WP, Fadden P, et al. The amino-terminal domain of heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) that binds geldanamycin is an ATP/ADP switch domain that regulates hsp90 conformation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23843–23850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F-U. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–580. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhfeld J, Minami Y, Hartl F-U. Hip, a novel cochaperone involved in the eukaryotic Hsc70/Hsp40 reaction cycle. Cell. 1995;83:589–598. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmer H, Höhfeld J. Characterization of functional domains of the eukaryotic co-chaperone Hip. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2230–2235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Pfund C, Craig EA. Functional specificity among Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Science. 1997;275:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jibard N, Meng X, Leclerc P, et al. Delimitation of two regions of the 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) able to interact with the glucocorticosteroid receptor (GR) Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:461–474. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ER, McKay DB. Mapping the role of active site residues for transducing an ATP-induced conformational change in the bovine 70-kDa heat shock cognate protein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10823–10830. doi: 10.1021/bi990816g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Schumacher RJ, Ross ED, Toft DO. Hop modulates Hsp70/Hsp90 interactions in protein folding. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3679–3686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Toft DO. Binding of p23 and hsp90 during assembly with the progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:670–678. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.6.8592513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Beito TG, Krco CJ, Toft DO. Characterization of a novel 23-kilodalton protein of unactive progesterone receptor complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1956–1963. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Toft DO. A novel chaperone complex for steroid receptors involving heat shock proteins, immunophilins, and p23. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24989–24993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S, Brocchiere L. Heat shock protein 70 family: multiple sequence comparisons, function, andevolution. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:565–577. doi: 10.1007/pl00006413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley WL. The J-domain family and the recruitment of chaperone power. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:222–227. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Interaction between Hsc70 and DnaJ homologues: relationship between Hsc70 polymerization and ATPase activity. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12452–12459. doi: 10.1021/bi9902788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Yahara I, Lindquist S. Role of the protein chaperone YDJ1 in establishing Hsp90-mediated signal transduction pathways. Science. 1995;268:1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.7761857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch R, Garabedian MJ. Role for Hsp90-associated cochaperone p23 in estrogen receptor signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3748–3759. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosano H, Stensgard B, Charlesworth MC, McMahon N, Toft D. The assembly of progesterone receptor-hsp90 complexes using purified proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32973–32979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann M, Schneikert J, Moll J, Heck S, Zeiner M, Gehring U, Cato AC. RAP46 is a negative regulator of glucocorticoid receptor action and hormone-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14620–14625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufen T, Mayer MP, Beisel C, Klostermeier D, Mogk A, Reinstein J, Bukau B. Mechanism of regulation of Hsp70 chaperones by DnaJ cochaperones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5452–5457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc P, Jibard N, Meng X, et al. Quantification of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of wild type and modified proteins using confocal microscopy: interaction between 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90alpha) and glucocorticosteroid receptor (GR) Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:255–264. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, MacRae TH. Molecular chaperones and the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1431–1440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.13.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Buesa P, Pfund C, Craig EA. The biochemical properties of the ATPase activity of a 70-kDa heat shock protein (HSP70) are governed by the C-terminal domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15253–15258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Cyr DM. The conserved carboxy terminus and zinc finger-like domain of the co-chaperone Ydj1 assist Hsp70 in protein folding. J Biol Chem. 1998a;273:5970–5978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Cyr DM. Protein folding activity of Hsp70 is modified differentially by the Hsp40 co-chaperones Sis1 and Ydj1. J Biol Chem. 1998b;273:27824–27830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JA, Kalton HM, Gaber RF. Cns1 is an essential protein associated with the Hsp90 chaperone complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that can restore cyclophilin 40-dependent functions in cpr7Delta cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7353–7359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruya M, Sameshima M, Nemoto T, Yahara I. Monomer arrangement in HSP90 dimer as determined by decoration with N and C-terminal region specific antibodies. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:903–907. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP, Laufen T, Paal K, McCarty JS, Bukau B. Investigation of the interaction between DnaK and DnaJ by surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:1131–1144. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misselwitz B, Staeck O, Rapoport TA. J proteins catalytically activate Hsp70 molecules to trap a wide range of peptide sequences. Mol Cell. 1998;2:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshauser RC, Hu W, Wang H, Pang Y, Flynn GC, Zuiderweg ER. High-resolution solution structure of the 18 kDa substrate-binding domain of the mammalian chaperone protein Hsc70. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:1387–1403. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata H, Hansen WJ, Freeman B, Welch WJ. Mammalian cytosolic DnaJ homologues affect the hsp70 chaperone-substrate reaction cycle, but do not interact directly with nascent or newly synthesized proteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6924–6938. doi: 10.1021/bi980164g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SC, Rimerman RA, Toran EJ, Chen S, Prapapanich V, Butts RN, Smith DF. Molecular cloning of human FKBP51 and comparisons of immunophilin interactions with Hsp90 and progesterone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:594–603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan DF, Vos MH, Lindquist S. In vivo functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90 chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12949–12956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann WMJ, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens-Grillo JK, Czar MJ, Hutchison KA, Hoffmann K, Perdew GH, Pratt WB. A model of protein targeting mediated by immunophilins and other proteins that bind to hsp90 via tetratricopeptide repeat domains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13468–13475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens-Grillo JK, Hoffmann K, Hutchison KA, Yem AW, Deibel MR Jr, Handschumacher RE, Pratt WB. The cyclosporin A-binding immunophilin CyP-40 and the FK506-binding immunophilin hsp56 bind to a common site on hsp90 and exist in independent cytosolic heterocomplexes with the untransformed glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20479–20484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou B, Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. ATP binding and hydrolysis are essential to the function of Hsp90 molecular chaperone in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17:4829–4836. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfund C, Lopez-Hoyo N, Ziegelhoffer T, Schilke BA, Lopez-Buesa P, Walter WA, Wiedmann M, Craig EA. The molecular chaperone Ssb from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a component of the ribosome-nascent chain complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:3981–3989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard D, Khursheed B, Garabedian MJ, Fortin MG, Lindquist S, Yamamoto KR. Reduced levels of hsp90 compromise steroid receptor action in vivo. Nature. 1990;348:166–168. doi: 10.1038/348166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli EV, Sandmeier E, Schönfeld HJ, Christen P. Control of the DnaK chaperone cycle by substoichiometric concentrations of the co-chaperones DnaJ and GrpE. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6643–6649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prapapanich V, Chen S, Smith DF. Mutation of Hip's carboxy-terminal region inhibits a transitional stage of progesterone receptor assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:944–952. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prapapanich V, Chen S, Nair SC, Rimerman RA, Smith DF. Molecular cloning of human p48, atransient component of progesterone receptor complexes and an Hsp70-binding protein. Mol Endocrinol. 1996a;10:420–431. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.4.8721986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prapapanich V, Chen S, Toran EJ, Rimerman RA, Smith DF. Mutational analysis of the hsp70-interacting protein Hip. Mol Cell Biol. 1996b;16:6200–6207. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Welsh MJ. Chaperone functions of the heat shock proteins associated with steroid receptors. Semin Cell Biol. 1994;5:83–93. doi: 10.1006/scel.1994.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Siligardi G, O'Brien R, et al. Regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity by tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-domain co-chaperones. EMBO J. 1999;18:754–762. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassow J, von Ahsen O, Bömer U, Pfanner N. Molecular chaperones: towards a characterization of the heat-shock protein 70 family. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:129–133. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(96)10056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak T, Carrello A. Cyclophilin 40 (CyP-40), mapping of its hsp90 binding domain and evidence that FKBP52 competes with CyP-40 for hsp90 binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2961–2965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds PD, Ruan Y, Smith DF, Scammell JG. Glucocorticoid resistance in the squirrel monkey is associated with overexpression of the immunophilin FKBP51. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1999;84:663–669. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.2.5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LC, Whitt SR, Chen M-S, Chinkers M. Identification of conserved residues required for the binding of a tetratricopeptide repeat domain to heat shock protein 90. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:20060–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R, Wali Karzai A, Mehl AF, McMacken R. DnaJ dramatically stimulates ATP hydrolysis by DnaK: Insight into targeting of Hsp70 proteins to polypeptide substrates. Biochemistry. 1999b;38:4165–4176. doi: 10.1021/bi9824036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi: 10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford SL, Zuker CS. Protein folding and the regulation of signaling pathways. Cell. 1994;79:1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel T, Siegmund HI, Jaenicke R, Ganz P, Lilie H, Buchner J. The charged region of Hsp90 modulates the function of the N-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1297–1302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel T, Weikl T, Buchner J. Two chaperone sites in Hsp90 differing in substrate specificity and ATP dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer LC, Hutchison KA, Sanchez ER, Randall SK, Pratt WB. A heat shock protein complex isolated from rabbit reticulocyte lysate can reconstitute a functional glucocorticoid receptor-Hsp90 complex. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7325–7329. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schett G, Steiner CW, Groger M, Winkler S, Graninger W, Smolen J, Xu Q, Steiner G. Activation of Fas inhibits heat-induced activation of HSF1 and up-regulation of hsp70. FASEB J. 1999;13:833–842. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.8.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneikert J, Hübner S, Martin E, Cato AC. A nuclear action of the eukaryotic cochaperone RAP46 in downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor activity. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:929–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte TW, Akinaga S, Murakata T, et al. Interaction of radicicol with members of the heat shock protein 90 family of molecular chaperones. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1435–1448. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.9.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaknovich R, Shue G, Kohtz DS. Conformational activation of a basic helix-loop-helix protein (MyoD1) by the C-terminal region of murine HSP90 (HSP84) Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5059–5068. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF. Dynamics of heat shock protein 90-progesterone receptor binding and the disactivation loop model for steroid receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1418–1429. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.11.7906860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Sullivan WP, Marion TN, Zaitsu K, Madden B, McCormick DJ, Toft DO. Identification of a 60-kilodalton stress-related protein, p60, which interacts with hsp90 and hsp70. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:869–876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Toft DO. Steroid receptors and their associated proteins. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:4–11. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.1.8446107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Faber LE, Toft DO. Purification of unactivated progesterone receptor and identification of novel receptor-associated proteins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3996–4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga S, Neckers LM, Schulte TW, et al. KF25706, anovel oxime derivative of radicicol, exhibitsin vivo antitumor activity via selective depletion of Hsp90 binding signaling molecules. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2931–2938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanou A, Isenberg DA, Nakajima K, Latchman DS. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 and heat shock factor-1 interact and activate the transcription of the Hsp-70 and Hsp-90beta gene promoters. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1723–1728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Xie Z, Reed JC. An evolutionarily conserved family of Hsp70/Hsc70 molecular chaperone regulators. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:781–786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft DO. Recent advances in the study of hsp90 structure and mechanism of action. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 1998;9:238–243. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(98)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GP, Chiu CH, Hansen TF. Is Hsp90 a regulator of evolvability? J Exp Zool. 1999;285:116–118. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19990815)285:2<116::aid-jez3>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Kurochkin AV, Pang Y, Hu W, Flynn GC, Zuiderweg ER. NMR solution structure of the 21 kDa chaperone protein DnaK substrate binding domain: a preview of chaperone-protein interaction. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7929–7940. doi: 10.1021/bi9800855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Singer MA, Lindquist S. Maturation of the tyrosine kinase c-src as a kinase and as a substrate depends on the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:109–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Dittmar KD, Giannoukos G, Pratt WB, Simons SS Jr.. Binding of hsp90 to the glucocorticoid receptor requires a specific 7-amino acid sequence at the aminoterminus of the hormone-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13918–13924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JC, Obermann WMJ, Hartl FU. Specific binding of tetratricopeptide repeat proteins to the C-terminal 12-kDa domain of hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18007–18010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Guo Y, Guettouche T, Smith DF, Voellmy R. Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by HSP90 (HSP90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell. 1998;94:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]