Summary

In pancreatic β cells, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an important cellular compartment for insulin biosynthesis, which accounts for half of total protein production in these cells. Protein flux through the ER must be carefully monitored to prevent dysregulation of ER homeostasis and stress. ER stress elicits a signaling cascade known as the unfolded protein response (UPR) which influences both cellular life and death decisions. β cell loss is a pathological component of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and recent findings suggest that ER stress is involved. In this review, we address the transition from the physiological ER stress response to the pathological response and explore the mechanisms of ER stress-mediated β cell loss during the progression of diabetes.

Protein homeostasis in the β cell

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the synthesis and folding site for membrane and secretory proteins, and is responsible for several important cellular functions including Ca2+ storage and cell signaling. In the β cell, the ER has an essential role in the assembly and processing of insulin. The ER houses a specialized environment, including complexes of chaperones and foldases, as well as high fidelity quality control mechanisms to ensure the crucial maintenance of ER homeostasis in these cells. ER homeostasis is defined as the unique equilibrium between the cellular demand for protein synthesis and the ER folding capacity to promote protein transport and maturation. β cells often undergo conditions that cause a disruption to ER homeostasis: fluctuations in blood glucose levels lead to a high demand for insulin biosynthesis via increasing both insulin transcription and translation [1, 2]. Glucose rapidly stimulates up to a 20-fold increase in insulin synthesis and total protein synthesis [3]. It has been proposed that this increase in proinsulin biosynthesis generates a heavy load of unfolded/misfolded proteins in the ER lumen [4]. This disruption in homeostasis and accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proinsulin in the ER lumen, causes ER stress [5]. Metabolic dysregulation associated with obesity, such as excess nutrients and insulin resistance, has also been implicated in the secretory burden of the β cell leading to ER stress and severely compromising cell function [6, 7]

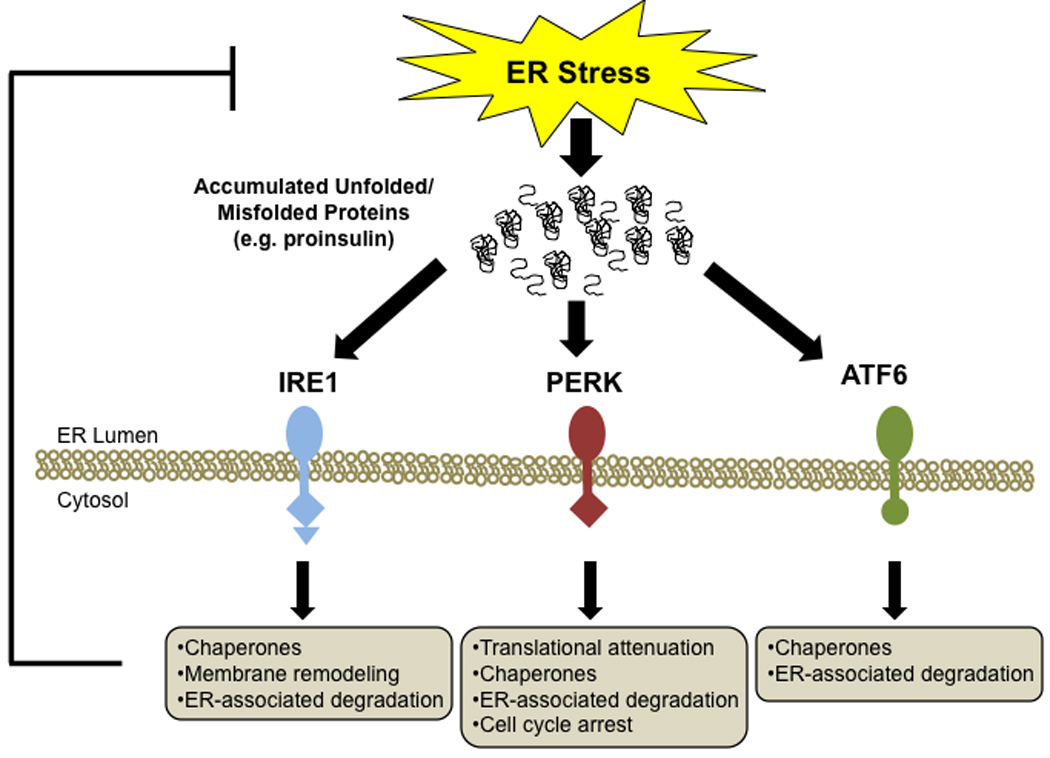

ER stress is sensed by the luminal domains of three ER transmembrane proteins: Inositol Requiring 1 (IRE1), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and Activating Transcription Factor 6 (ATF6). Once activated, these stress sensors transduce a complex ER-to-nucleus signaling cascade termed the unfolded protein response (UPR) [8] (Figure 1). The UPR regulates several downstream effectors that function in adaptation, feedback control, and cell fate regulation [9]. Initially the UPR triggers the adaptive response: enhancement of folding activity through upregulation of molecular chaperones and protein processing enzymes. This is followed by reduction of ER workload through translational attenuation and mRNA degradation, and an increase in the expression of ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) and autophagy components to promote clearance of unwanted proteins.

Figure 1. The ER stress signaling network.

There are three main regulators of the unfolded protein response (UPR): IRE1, PERK, and ATF6. Each of these stress transducers activates downstream targets which mitigate ER stress.

IRE1 is an ER transmembrane kinase with endoribonuclease activity. In response to ER stress, IRE1 oligomerizes and undergoes transautophosphorylation, leading to activation of its endoribonuclease activity and unconventional splicing of transcription factor X-box protein binding 1 (XBP1) mRNA, which regulates chaperone and ERAD protein expression.

Like IRE1, PERK is a transmembrane kinase which dimerizes and autophosphorylates when stress is sensed. Its main function is to regulate protein synthesis through phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α). This inhibits general protein synthesis, while preferentially increasing translation of selected UPR mRNAs such as activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which is involved in regulating genes important for resting ER homeostasis.

ATF6, the third UPR transducer, is unique in that it is part of a family of ER transmembrane sensors which function in a cell-/tissue-specific manner. For example, one family member, cAMP responsive element-binding protein 3-like protein 1 (OASIS), is a putative ER stress sensor in astrocytes [10, 11]. Unlike IRE1 and PERK, ATF6 is a transcription factor which gets shuttled to the Golgi for its ER stress-mediated activation. Translocation of the processed form of ATF6 to the nucleus results in the upregulation of UPR homeostatic effectors involved in protein folding, processing, and degradation.

All three UPR transducer responses are critical in β cells to alleviate ER stress and restore ER homeostasis, ensuring the proper production of high quality proteins, especially insulin, which accounts for approximately half of total protein production in these cells [12]. This sensitive stress-sensing program, the UPR, has built-in feedback control mechanisms to switch off the UPR master regulators and their downstream targets, thus preventing harmful UPR hyperactivation [13]. The UPR, therefore, is not only responsible for regulating the expression and activation of adaptation/survival effectors, but it can also promote cell death [9, 14–16]. It is also evident that conditions associated with severe ER stress can compromise β cell function [7].

Causes of ER-stressed β cells

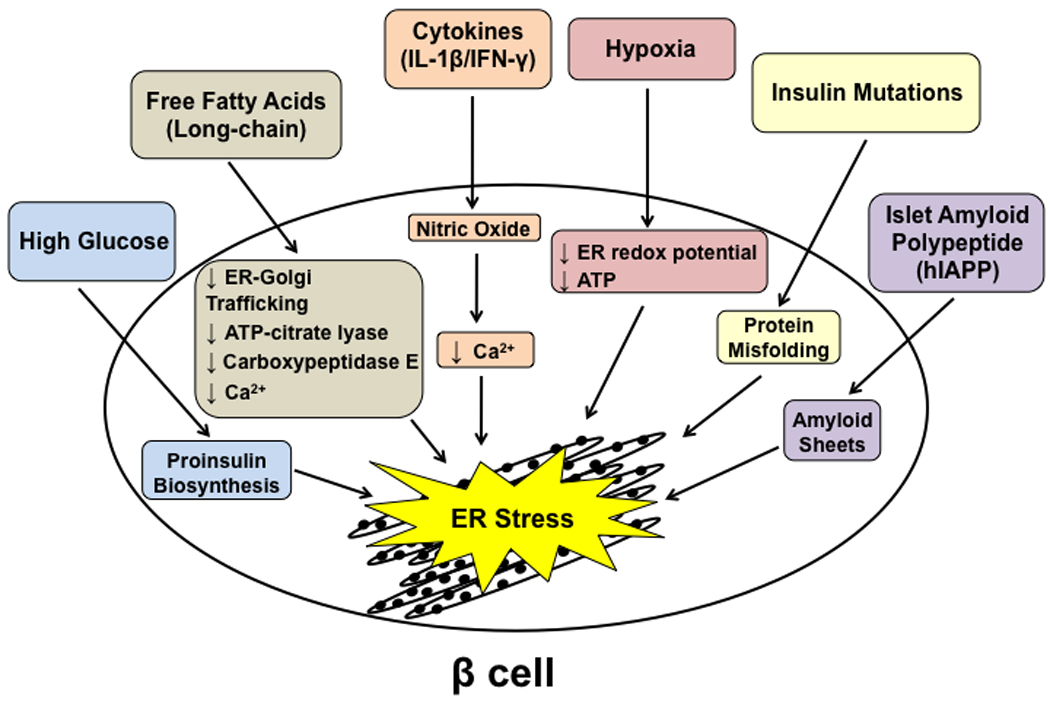

There are several proposed physiological, environmental, and genetic causes of ER stress activation specific for β cells (Figure 2). One form of physiological stress, which can become a pathological stress, occurs when these cells are exposed to high glucose [17]. Under high glucose conditions, increased insulin biosynthesis can overwhelm the ER folding capacity, causing an imbalance in homeostasis and leading to ER stress. Both acute (1–3 hours) and chronic (≥ 24 hours) high glucose (≥16.7 mM) have been shown to induce activation of IRE1α in vivo and in isolated rat and mouse islets [18, 19]. In one study, transient activation of IRE1α by high glucose was shown to enhance proinsulin biosynthesis via minimal splicing of XBP-1, whereas other studies have shown that prolonged activation of IRE1α by chronic high glucose, a pathological condition, leads to insulin mRNA degradation, profuse XBP-1 splicing, and induction of pro-apoptotic effectors, such as Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), causing β cell dysfunction and death [19–22]. It should be noted that the handling of primary rodent islets seems to be critical in determining the level of UPR activation from chronic, high glucose treatment [18]. In in vivo rodent models, exposure of islets to a hyperglycemic environment causes suppression of genes needed to optimize glucose-induced insulin secretion and maintain β cell differentiation [23]. In rodent diabetic db/db islets, there is also evidence of ER stress signaling activation [24]. Chronically elevated glucose, referred to as glucose toxicity, is associated with increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can also induce ER stress, in addition to other cellular effects [25–27]. Chronically elevated ER stress, therefore, may also play a role in glucose toxicity which contributes to potentially irreversible β cell damage leading to diabetes. However, while ER stress seems to somehow be involved in chronic hyperglycemia, it must be noted that the cellular response to glucotoxicity is complicated. Interestingly, tribbles homolog 3 (TRB3), may be the link between glucotoxicity and ER stress-mediated apoptosis. TRB3, which inhibits Akt/PKB signaling, is upregulated in hyperglycemic Goto-Kakizaki rat islets and has been implicated in ER stress-induced apoptosis, as well as negative regulation of insulin exocytosis [28, 29].

Figure 2. Causes of ER stress in the β cell.

There are several causes of ER stress in the β cell ranging from physiological stress, such as high glucose levels which follow meal intake, to pathological causes such as the expression of mutant insulin protein.

Free fatty acids (FFAs), specifically long-chain FFAs, have also been implicated in induction of ER stress in β cells [13, 30]. Treatment of rodent islets with the saturated FFA, palmitate, causes ER distension as well as activation of all three UPR stress sensors. Overexpression of the ER-resident chaperone, binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), in β cells protects against FFA-induced lipo-apoptosis [24].The mechanism behind this ER stress-induced lipo-apotosis is complicated and may involve several factors, including depletion of ER calcium levels [31]. It has also been proposed that FFAs, such as palmitate, reduces ER-to-Golgi trafficking, contributing to ER stress through protein overload in the ER lumen [32]. Other proposed mechanisms include alterations in ATP-citrate lyase expression, as well as carboxypeptidase E (CPE) levels. The UPR may also contribute to FFA-induced β cell death through upregulation of the proapoptic effector CHOP, and activation of JNK and caspase-12 [33]. Interestingly, a study in human islets showed that ER stress is involved in lipotoxicity, but not in gluco-lipotoxicity. Palmitate treatment led to severe ER stress and induction of apoptosis, but the palmitate-induced ER stress response was not modified by high glucose concentrations [34].

Inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and γ-interferon (IFN-γ), can also cause ER stress and UPR activation in β cells [35]. While it is controversial whether or not cytokine-induced β cell death is dependent or independent of ER stress signaling, IL-1β in combination with IFN-γ has been shown to induce nitric oxide (NO) in β cells, leading to β cell dysfunction and death in type 1 diabetes [36, 37]. It has been shown that NO-induced β cell apoptosis is mediated by ER stress [38]. NO production decreases expression of the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b (SERCA2b), leading to a decrease in Ca2+ in the ER. This Ca2+ depletion causes a high level of ER stress in β cells which may play a role in cytokine-induced cell death in type 1 diabetes [35, 39].

Hypoxia has also been shown to cause ER stress in β cells. The ER lumen maintains an oxidizing environment to promote disulfide bond formation in newly synthesized proteins, which is particularly important for proinsulin which requires three disulphide bonds for proper folding [40]. In addition, the ER has high concentrations of ATP, which contributes to the folding efficiency of molecular chaperones. Hypoxia negatively impacts both ER redox potential and ATP concentrations, causing ER stress. Islets are normally highly vascularized, which is important for their ability to quickly secrete insulin in response to changes in blood glucose levels [41]. Hypoxia-mediated ER stress may play a role in the death of transplanted pancreatic islets [15]. Transplanted islet grafts experience hypoxia for several days post-transplantation. In addition, they are less vascularized and have a lower oxygen tension than endogenous islets in the pancreas, even after revascularization is complete, thus rendering them susceptible to hypoxia-mediated ER stress [42–44]. In addition to islet graft loss by immunological factors, a substantial portion of the transplanted cells are no longer able to cope with the deleterious effects of hypoxia and eventually undergo apoptosis. Indeed, a recent study shows that human islet grafts transplanted into SCID mice exhibited signs of ER stress, which was thought to be a protective response [45]. It was speculated that the majority of islet cells would have a protective ER stress response, while a subgroup of vulnerable cells undergo apoptosis due to activation of the proapototic UPR branch. Thus, ER stress-mediated β cell death may play an important role in death of transplanted islets.

It has been shown that β cell failure is also associated with mutations in murine and human proinsulin that cause misfolding and accumulation of proinsulin in the ER lumen [46, 47]. Expression of mutant insulin has been associated with ER stress activation. The Akita diabetic mouse model carries a mutation in the insulin 2 gene [48], which results in a cysteine96 to tyrosine substitution. Cysteine96 is involved in the formation of one of the three disulfide bonds between the A and B chains of mature insulin [49]. These mice develop diabetes, which may result from both β cell dysfunction and death, as this mutation causes incorrect folding of proinsulin in the ER of β cells [50, 51]. Recent genetic studies have uncovered several mutations in the human insulin gene, specifically mutations occurring in critical regions of proinsulin folding, termed MIDY (Mutant INS-gene-induced Diabetes of Youth) that result in early-onset diabetes and may lead to impairment of normal proinsulin folding. While these mutants induce ER stress and the UPR, it remains controversial whether this alone is sufficient to activate apoptosis [52–54]. Interestingly, one of the mutations found is the exact mutation from the Akita mouse [21].

It is also hypothesized that misfolded islet amyloid precursor protein (IAPP) may accumulate in the β cell ER lumen and cause ER-induced apoptosis [55, 56]. Islet amyloid expression is a common characteristic in type 2 diabetes and may play a role in β cell dysfunction and death during the progression of the disease [57]. Islet amyloid is composed of a 37-residue amyloidogenic polypeptide derived from IAPP. IAPP spontaneously forms ER membrane-damaging sheets of amyloid [58]. While one study has shown a disconnect between human IAPP and ER stress [59], others have shown that high expression of human IAPP induces ER stress and subsequent death of β cells [55, 60]. Therefore, IAPP could be one of the links between ER stress and β cell death in type 2 diabetes.

Life and death decisions

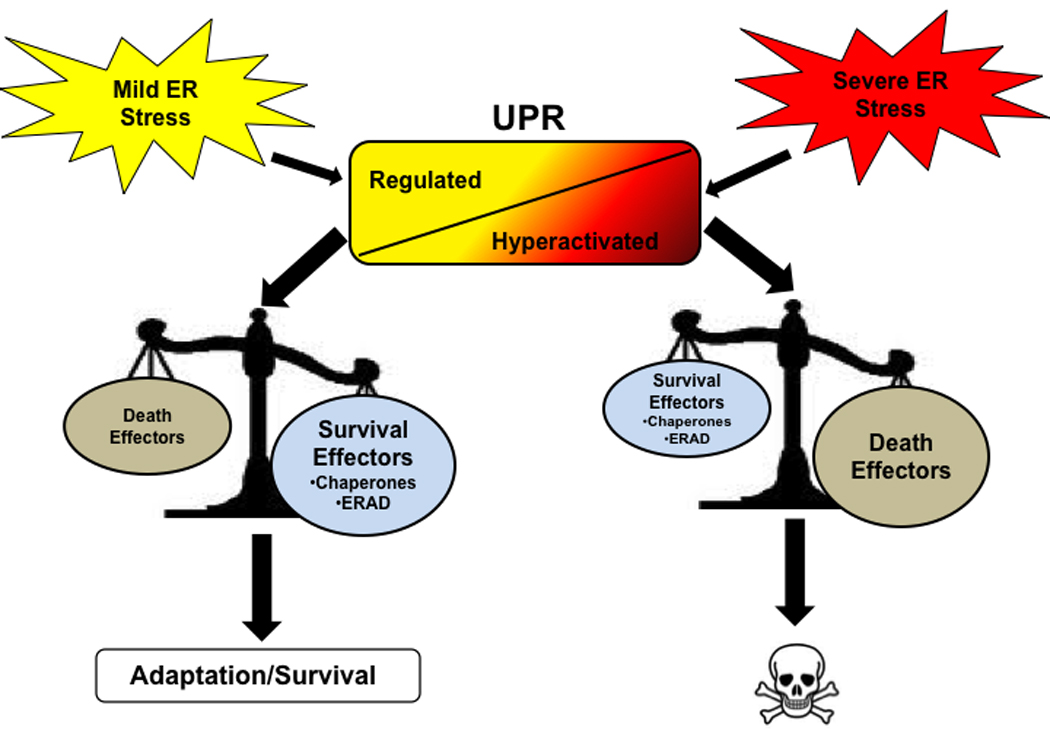

The ultimate cell fate decision of life or death is dependent on the nature and severity of ER stress that the β cell is exposed to. Thus, there are two types of ER stress conditions: resolvable and unresolvable. When ER stress can be resolved, the UPR promotes β cell survival. In contrast, under unresolvable ER stress conditions, the UPR activates death effectors, leading to β cell apoptosis.

When β cells are exposed to conditions that induce mild ER stress (e.g. physiological exposure to glucose fluctuations following a meal), the ER can facilitate stress mitigation and restore protein homeostasis, thus “priming” cells for future ER stress insult and promoting cell survival. It has been shown that IRE1α and PERK are the primary transducers for regulating insulin production under these conditions, thus promoting activation of UPR pro-survival pathways [4, 5, 19, 61, 62]. Unresolvable ER stress conditions occur when an insufficient UPR response fails to restore ER homeostasis, leading to the induction of pro-apoptotic pathways. This can be attributed to several factors from genetic mutations to chronic exposure to high glucose, as well as dysregulation of the UPR itself. Thus, the UPR behaves like a binary switch between life and death in β cells.

This binary switch is regulated by the three master UPR transducers: IRE1, PERK, and ATF6. Both adaptive/survival and death effectors are simultaneously expressed during UPR activation, and it is the delicate balance between these effectors which determines the fate of the cell (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The balance between death and survival.

The UPR acts as a binary switch between cell survival and death decisions when ER stress is present in the cell. Mild stress induces a regulated UPR, in which survival effectors outweigh death effectors, leading to adaption and survival of the cell. When severe stress is present, on the other hand, the UPR becomes hyperactivated, a situation in which the death effectors outweigh survival effectors, ultimately leading to apoptosis.

The IRE1-XBP1 pathway regulates the expression of homeostatic components of the UPR such as chaperones and components of the ERAD machinery. In addition to cleavage of XBP1, IRE1 also plays a role in the cleavage of other ER-associated mRNAs, such as insulin mRNA, thus relieving the workload placed on the ER [20, 63–66]. In β cells, mild activation of IRE1 is particularly important for enhancement of insulin biosynthesis. While this may be an XBP1-independent process, other components of this pathway, such as oxidoreductase endoplasmic oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1) enzymes may also be involved [3]. ERO1 enzymes are responsible for oxidizing protein disulphide isomerase (PDI) during disulfide bond formation and appear to be important for proinsulin folding. Recent studies show that disruption of the pancreatic-selective isoform of ERO1, ERO1β, compromises oxidative folding of proinsulin and leads to glucose intolerance in mice [67]. Enhancement of insulin biosynthesis is an adaptive mechanism, which is beneficial not only to β cell function, but also survival. While IRE1 has a role in promoting cell survival, it acts as a binary switch and has additional functions in promoting cell death through two mechanisms: (1) endoribonuclease activity and (2) kinase activity. IRE1’s endoribonuclease function may regulate cell death by downregulating mRNAs involved in β cell homeostasis and survival, such as the redox protein, PDI, the ER-resident chaperone, BiP, while its kinase function plays a role in activation of UPR death effectors [66, 68]. There are two IRE1-dependent pathways which promote cell death through its kinase activity: (1) phosphorylation of JNK via IRE1-dependent recruitment of TNF-receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and (2) activation of murine caspase-12 (caspase-4 and caspase-11 in humans) [69, 70]. In β cells, chronic hyperglycemia leads to IRE1 hyperactivation and consequent activation of UPR death effectors [19]. This hyperactivation leads to higher levels of XBP1 splicing, which may be harmful to the cell. It has been shown that overexpression of spliced XBP1 can suppress insulin expression and inhibit β cell function, ultimately leading to cell death [71].

PERK also acts as a binary switch in the UPR. PERK is highly expressed in β cells and its activation negatively regulates insulin biosynthesis. PERK’s role in attenuating protein production has been shown to protect β cells from ER stress-mediated apoptosis. Complimentary to its role in protecting the cell by initiating a global reduction in protein synthesis, PERK also has been found to upregulate an anti-apoptotic effector, apoptosis antagonizing transcription factor (AATF), which is responsible for mediating β cell survival in part through transcriptional regulation of AKT1 [72]. PERK, however, can also activate proapoptotic effectors. Reducing PERK activity has been shown to ameliorate the progression of the insulin Akita mutant mice towards diabetes [73]. It has been shown that continuous activation of eIF2α induces β cell apoptosis, through ATF4 activation [13]. ATF4 promotes cell death under conditions of unresolvable ER stress through transcription of CHOP [74, 75]. CHOP promotes cell death through five outputs: (1) promoting hyper-oxidizing environment in the ER, (2) increasing the client protein load in the ER through GADD34 activation, (3) increasing the expression of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member PUMA, (4) increasing the expression of the Akt inhibitor, TRB3, and (5) activating calcium release through inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor [76–80]. Thus, like IRE1, PERK also plays a critical role in balancing life and death decisions.

The third binary switch of the UPR, ATF6, serves a protective role and promotes cell survival by increasing the folding capacity of the ER. However, like IRE1 and PERK, ATF6 can also act as a binary switch between survival and death, which in part may be determined by one of its downstream effectors, CHOP. In β cells, hyperactivation of ATF6 suppresses insulin gene expression and has been shown to cause β cell dysfunction and death [81]. The exact mechanism for this suppression of insulin expression is currently unknown.

It is clear that each of the UPR master transducers must be under tight control due to their dual roles as regulators of both survival and cell death. ER stressors trigger both protective and proapoptotic outputs simultaneously, so the question is how cell fate is determined by the UPR? This is where the distinction of resolvable and unresolvable ER stress comes into play. When ER stress is resolvable, the master regulators and their downstream effectors are properly switched off, thus restoring ER homeostasis. However, this stress becomes unresolvable when this feedback regulation is bypassed, resulting in hyperactivation of the UPR. This hyperactivation redirects the cell into an apoptotic fate, via upregulation of death effectors. Important targets involved in this feedback process include BiP, GADD34, p58IPK, RACK1, and WFS1 [39–43]. The ER-resident chaperone, BiP, binds to IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 to keep them in an inactive state in the ER membrane. As mentioned previously, GADD34 restores translation by dephosphorylating eIF2α, thus turning off the PERK pathway. Another regulator of the PERK pathway is p58IPK, which inhibits eIF2α signaling. Interestingly, Dnajc3 (p58IPK) knockout mice exhibit a gradual onset of hyperglycemia associated with an increase in apoptosis of islet cells. Receptor of activated protein kinase C 1 (RACK1) has been recently shown to be an important regulator of the IRE1 pathway. With mild ER stress, such as acute glucose treatment of β cells, RACK1 recruits protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) to IRE1, thereby turning off its activation. Wolfram syndrome 1 (WFS1), on the other hand, plays an important role in regulating the third master regulator, ATF6. WFS1 prevents ATF6 activation by recruiting ATF6 to the proteasome for ubiquitin-mediated degradation. It has been shown that a lack of functional WFS1, leads to hyperactivation of ATF6 signaling, inducing β cell death [43].

UPR survival outputs (i.e. the feedback regulators), if functioning properly, outweigh any of the death effectors, thus favoring cell survival. This may be due to the increased mRNA and protein stability of these feedback targets over apoptotic proteins, which provides the cell with an opportunity to adapt to stress. Further research is needed to better understand what is the exact turning point which favors the apoptotic fate and how the UPR can bypass the feedback regulation put in place to prevent this from occurring.

ER stress-mediated diabetes: Genetic evidence

Clinical and genetic evidence suggest that ER stress is one of the molecular mechanisms involved in β cell dysfunction and death which occurs in diabetes. In diet-induced and genetic rodent models of insulin resistance, it has been shown that knockout of the proapoptotic ER stress gene, CHOP, improves glycemic control and expansion of β cell mass [82].

This relationship of ER stress-induced β cell dysfunction and death was first revealed in a form of hereditary diabetes, the Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. In this syndrome, inactivating mutations in the EIF2AK3 gene encoding PERK have been reported [44]. It has become evident that PERK plays a critical role in the life of the β cell, as in Eif2ak3 (PERK) knockout models, β cells fail to expand during neonatal development due to decreased proliferation, causing diabetes [45][61]. PERK is also important for β cell differentiation, as Eif2ak3 knockout islets are deficient in key markers of differentiation [61]. Interestingly, when Eif2ak3−/− islets are cultured in high glucose, insulin production is more vigorous than wild type islets, promoting ER stress and the accumulation of electron dense material in the ER lumen [4]. As mentioned previously, phosphorylation of PERK’s primary target, eIF2α, is essential to regulating the UPR and insulin synthesis. In agreement with this, mice carrying a heterozygous mutation in the phosphorylation site of eIF2α (Eif2s1+//tm1Rjk) show severe β cell deficiency and develop diabetes when fed a high-fat diet. These mice show abnormal β cell ER morphology, defective insulin trafficking, and reduced secretory granule number [5]. Thus, dysregulation in the UPR contributes to diabetes found in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome most likely through a loss in β cell mass caused by a lack in β cell proliferation and potentially a vulnerability to ER stress-induced apoptosis.

Permanent neonatal diabetes or MIDY is another example of the involvement of excessive ER stress in diabetes. This form of diabetes, which occurs within the first month of life, can be caused by several types of mutations, including mutations in the critical regions of preproinsulin. Mouse models of this disease, the Munich and Akita mouse which both have dominant missense mutations in the Ins2 (insulin) gene, reveal that progressive hyperglycemia associated with the mutations is accompanied by elevated levels of ER stress markers such as BiP and CHOP [46, 48]. While these mutants exhibit high levels of ER stress and develop diabetes, as previously mentioned, it is controversial whether this alone is sufficient to activate apoptosis [52, 54].

Wolfram syndrome, a rare disorder characterized by diabetes mellitus and optical atrophy, is another example of a genetic link between ER stress and β cell death and diabetes [46]. Here there is a selective loss of β cells which has been attributed to mutations in WFS1, a gene encoding an ER transmembrane protein that is localized to β cells. It has recently been shown that WFS1 is a key feedback regulator of the ATF6 branch of the UPR. Presumably, patients with Wolfram syndrome have UPR hyperactivation in their β cells, leading to cell death. Recent genome-wide association studies reveal WFS1 polymorphisms are associated with impaired β cell function and risk for type 2 diabetes [83–85]. Thus, WFS1 seems to be a β cell-specific prosurvival component of the UPR.

ER stress: Link between β cell loss and impaired function in common forms of diabetes

Recent evidence indicates that β cell death is a major pathogenic component in most forms of diabetes [30]. Type 1 diabetes is a condition of absolute insulin deficiency due to β cell death by autoimmunity. Type 2 diabetes is a condition of relative insulin deficiency due to β cell dysfunction and death as the combined consequence of increased circulating glucose, saturated fatty acids, and inflammation. Despite in vitro and in vivo findings in rodent models which show a link between ER stress and β cell dysfunction and death, the role of ER stress-induced diabetes in humans remains controversial. In some of the genetic forms of diabetes outlined above, such as Wolfram syndrome and permanent neonatal diabetes, protein misfolding and dysregulated ER homeostasis can contribute to β cell death. Evidence of ER stress in the β cells of patients with type 2 diabetes has also been documented in several studies [24, 56]. However, the extent of UPR induction in patients seems to be variable. Autopsy samples from type 2 diabetic patients exhibit higher levels of ER stress, while isolated islets only show signs of ER stress when cultured at high glucose, raising the possibility of multiple factors playing a role in β cell death, including oxidative stress [86, 87]. Gene profiling studies also do not show a marked difference in ER stress levels in type 2 diabetic patients, however, this could be a sign of chronic compensation [88, 89].

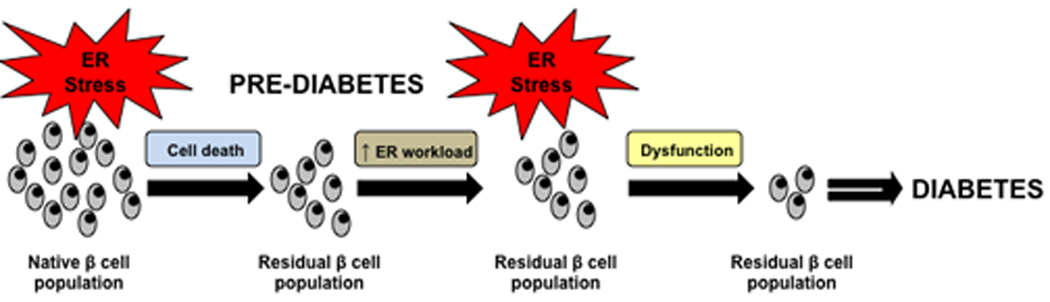

One more factor must be kept in mind when looking at the relationship between ER stress and diabetes: the role of β cell dysfunction. It has been reported that patients with impaired fasting glucose, a group at high risk of developing overt diabetes, have a 40% deficit in relative β cell volume compared with comparable obese control subjects with normal fasting glucose concentration, while patients with overt diabetes had a 60% deficit [90]. This has also been documented in other studies, however it remains unclear whether or not the decline in β cell mass by itself can cause diabetes, as human studies have proven to be somewhat variable [91, 92]. The question remains whether it is a decline in β cell mass, deteriorating β cell function, or both which cause type 2 diabetes. Despite this, it is intriguing to think that the tipping point between pre-diabetes and overt diabetes could lie in an additional 20% loss of β cells. Interestingly, it has been shown that β cell mass further declines with duration of clinical diabetes [92]. We propose that ER stress-mediated β cell dysfunction plays an important role in the transition from pre-diabetes to overt diabetes, since this further decline in cell mass is likely not to be the cause of diabetes in the absence of β cell dysfunction. When patients have lost 40 % of β cells, increased workload for production of insulin on residual β cells may cause chronic ER stress, leading to translational attenuation of proinsulin and degradation of insulin mRNA. This “adaptive” response exacerbates chronic hyperglycemia, leading to unresolvable ER stress and ER stress-mediated apoptosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. ER stress: The tipping point between β cell death and dysfunction.

ER stress mediated β cell dysfunction plays an important role in the transition from a pre-diabetic state to an overt diabetic state. In the pre-diabetic state some β cell loss has already occurred and residual β cells have to work harder to keep up with insulin output. This leads to additional ER stress, causing β cell dysfunction. This dysfunction is the tipping point leading to additional cell loss and the progression to a diabetic state.

UPR: Target for diabetes therapy

We propose that discovering methods that could reduce ER stress to a tolerable state and/or modulating the UPR to preferentially activate survival over death pathways could lead to novel and efficient therapeutic modalities for diabetes. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a good candidate for targeting this type of therapy. As described above, mild activation of the UPR by tolerable ER stress or specific activation of anti-apoptotic pathways of the UPR has beneficial effects on β cell function and survival. GLP-1, which is a gut-derived peptide secreted from intestinal L-cells after a meal, has numerous physiological actions, including enhancement of β cell growth and survival [93]. GLP-1 is also a physiological activator of the UPR. Activation of GLP-1 signaling improves β cell function and survival through the mild activation of the UPR [19, 94]. We predict that other endogenous factors, like GLP-1, or chemical compounds that can mildly activate the UPR could be used to increase the viability of β cells.

Conclusions and future directions

The prevalence of diabetes has risen dramatically world-wide. In type 1 diabetes, it has been established that β cell death is a major pathogenic component. Recent discoveries in human genetics have revealed that genes important for β cell survival, proliferation, and function are also involved in type 2 diabetes [95–100]. These findings point to the importance of developing therapies able to preserve or restore depleted numbers of β cells for type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Increasing clinical, experimental, and genetic evidence indicates that ER stress and the UPR has a role in β cell dysfunction and death during the progression of type 1, type 2, and genetic forms of diabetes. It is currently believed that the UPR behaves as a binary switch between life and death of the β cell. The complete understanding of how the UPR regulates cell fate will provide us with new insights into mechanisms of β cell death and shed light on future diabetes prevention or treatment. Prevention of diabetes could be improved by preventing unresolvable ER stress in β cells. It would also be important to study the associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the UPR genes and individuals’ predispositions to β cell death and diabetes. Advances in pharmacogenomics may allow us to target critical molecules regulating the UPR binary switch for preventing β cell death. We propose that understanding and regulation of the UPR binary switch in β cells will lead to a novel therapeutic modalities and prevention for most forms of diabetes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Melloul D, et al. Regulation of insulin gene transcription. Diabetologia. 2002;45:309–326. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0728-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poitout V, et al. Regulation of the insulin gene by glucose and fatty acids. J Nutr. 2006;136:873–876. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.4.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodge KA, Hutton JC. Translational regulation of proinsulin biosynthesis and proinsulin conversion in the pancreatic beta-cell. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:235–242. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding HP, et al. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Molecular Cell. 2001;7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheuner D, et al. Control of mRNA translation preserves endoplasmic reticulum function in beta cells and maintains glucose homeostasis. Nat Med. 2005;11:757–764. doi: 10.1038/nm1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eizirik DL, et al. The role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocrine reviews. 2008;29:42–61. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response: a pathway that links insulin demand with beta-cell failure and diabetes. Endocrine reviews. 2008;29:317–333. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nature reviews. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oslowski CM, Urano F. The binary switch between life and death of endoplasmic reticulum-stressed beta cells. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010 doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283372843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vellanki RN, et al. OASIS/CREB3L1 induces expression of genes involved in extracellular matrix production but not classical endoplasmic reticulum stress response genes in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4146–4157. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo S, et al. OASIS, a CREB/ATF-family member, modulates UPR signalling in astrocytes. Nature cell biology. 2005;7:186–194. doi: 10.1038/ncb1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuit FC, et al. Glucose stimulates proinsulin biosynthesis by a dose-dependent recruitment of pancreatic beta cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:3865–3869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cnop M, et al. Selective inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha dephosphorylation potentiates fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:3989–3997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oslowski CM, Urano F. The binary switch that controls the life and death decisions of ER stressed beta cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oslowski CM, Urano F. A switch from life to death in endoplasmic reticulum stressed beta-cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12 Suppl 2:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szegezdi E, et al. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prentki M, Nolan CJ. Islet beta cell failure in type 2 diabetes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:1802–1812. doi: 10.1172/JCI29103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elouil H, et al. Acute nutrient regulation of the unfolded protein response and integrated stress response in cultured rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1442–1452. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipson KL. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell Metab. 2006;4:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipson KL, et al. The Role of IRE1alpha in the Degradation of Insulin mRNA in Pancreatic beta-Cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou ZQ, et al. Involvement of chronic stresses in rat islet and INS-1 cell glucotoxicity induced by intermittent high glucose. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;291:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonas JC, et al. Glucose regulation of islet stress responses and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11 Suppl 4:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laybutt DR, et al. Influence of diabetes on the loss of beta cell differentiation after islet transplantation in rats. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2117–2125. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0749-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laybutt DR, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:752–763. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0590-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson RP, et al. Glucose toxicity of the beta-cell. In: LeRoith D, et al., editors. Diabetes Mellitus. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson RP, et al. Glucose toxicity in beta-cells: type 2 diabetes, good radicals gone bad, and the glutathione connection. Diabetes. 2003;52:581–587. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress: a vicious cycle or a double-edged sword? Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2007;9:2277–2293. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liew CW, et al. The pseudokinase tribbles homolog 3 interacts with ATF4 to negatively regulate insulin exocytosis in human and mouse beta cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:2876–2888. doi: 10.1172/JCI36849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian B, et al. TRIB3 [corrected] is implicated in glucotoxicity- and endoplasmic reticulum-stress-induced [corrected] beta-cell apoptosis. J Endocrinol. 2008;199:407–416. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karaskov E, et al. Chronic palmitate but not oleate exposure induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, which may contribute to INS-1 pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3398–3407. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gwiazda KS, et al. Effects of palmitate on ER and cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis in beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E690–E701. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90525.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preston AM, et al. Reduced endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-to-Golgi protein trafficking contributes to ER stress in lipotoxic mouse beta cells by promoting protein overload. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2369–2373. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharroubi I, et al. Free fatty acids and cytokines induce pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by different mechanisms: role of nuclear factor-kappaB and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5087–5096. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunha DA, et al. Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:2308–2318. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardozo AK, et al. Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:452–461. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eizirik DL, et al. The harmony of the spheres: inducible nitric oxide synthase and related genes in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 1996;39:875–890. doi: 10.1007/BF00403906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akerfeldt MC, et al. Cytokine-induced beta-cell death is independent of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. Diabetes. 2008;57:3034–3044. doi: 10.2337/db07-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oyadomari S, et al. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10845–10850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191207498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cardozo AK, et al. A comprehensive analysis of cytokine-induced and nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent genes in primary rat pancreatic beta-cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:48879–48886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu BP, Weissman JS. Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:341–346. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brissova M, Powers AC. Revascularization of transplanted islets: can it be improved? Diabetes. 2008;57:2269–2271. doi: 10.2337/db08-0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlsson PO, et al. Markedly decreased oxygen tension in transplanted rat pancreatic islets irrespective of the implantation site. Diabetes. 2001;50:489–495. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlsson PO, et al. Low revascularization of experimentally transplanted human pancreatic islets. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2002;87:5418–5423. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattsson G, et al. Decreased vascular density in mouse pancreatic islets after transplantation. Diabetes. 2002;51:1362–1366. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennedy J, et al. Protective unfolded protein response in human pancreatic beta cells transplanted into mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herbach N, et al. Dominant-negative effects of a novel mutated Ins2 allele causes early-onset diabetes and severe beta-cell loss in Munich Ins2C95S mutant mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:1268–1276. doi: 10.2337/db06-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colombo C, et al. Seven mutations in the human insulin gene linked to permanent neonatal/infancy-onset diabetes mellitus. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:2148–2156. doi: 10.1172/JCI33777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, et al. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:27–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masharani U, Karam JH. Pancreatic Hormones and Diabetes Mellitus. In: Greenspan FS, Gardner DG, editors. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 623–698. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshioka M, et al. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:887–894. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kayo T, Koizumi A. Mapping of murine diabetogenic gene mody on chromosome 7 at D7Mit258 and its involvement in pancreatic islet and beta cell development during the perinatal period. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:2112–2118. doi: 10.1172/JCI1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steiner DF, et al. A brief perspective on insulin production. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11 Suppl 4:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hodish I, et al. Misfolded proinsulin affects bystander proinsulin in neonatal diabetes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:685–694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu M, et al. Mutant INS-gene induced diabetes of youth: proinsulin cysteine residues impose dominant-negative inhibition on wild-type proinsulin transport. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang CJ, et al. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced beta-cell apoptosis and accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins by human islet amyloid polypeptide. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1656–E1662. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00318.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang CJ, et al. High expression rates of human islet amyloid polypeptide induce endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated beta-cell apoptosis, a characteristic of humans with type 2 but not type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2016–2027. doi: 10.2337/db07-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritzel RA, et al. Human islet amyloid polypeptide oligomers disrupt cell coupling, induce apoptosis, and impair insulin secretion in isolated human islets. Diabetes. 2007;56:65–71. doi: 10.2337/db06-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sawaya MR, et al. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 2007;447:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hull RL, et al. Amyloid formation in human IAPP transgenic mouse islets and pancreas, and human pancreas, is not associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1102–1111. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1329-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matveyenko AV, et al. Successful versus failed adaptation to high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance: the role of IAPP-induced beta-cell endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetes. 2009;58:906–916. doi: 10.2337/db08-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W, et al. PERK EIF2AK3 control of pancreatic beta cell differentiation and proliferation is required for postnatal glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scheuner D, et al. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Molecular Cell. 2001;7:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hollien J, et al. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science (New York, N.Y. 2006;313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pirot P, et al. Global profiling of genes modified by endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta cells reveals the early degradation of insulin mRNAs. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1006–1014. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han D, et al. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zito E, et al. ERO1-beta, a pancreas-specific disulfide oxidase, promotes insulin biogenesis and glucose homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:821–832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishitoh H, et al. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.992302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urano F, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science (New York, N.Y. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoneda T, et al. Activation of caspase-12, an endoplastic reticulum (ER) resident caspase, through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2-dependent mechanism in response to the ER stress. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:13935–13940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allagnat F, et al. Sustained production of spliced X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) induces pancreatic beta cell dysfunction and apoptosis. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1120–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishigaki S, et al. AATF mediates an antiapoptotic effect of the unfolded protein response through transcriptional regulation of AKT1. Cell death and differentiation. 2010;17:774–786. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta S, et al. PERK (EIF2AK3) regulates proinsulin trafficking and quality control in the secretory pathway. Diabetes. 2010;59:1937–1947. doi: 10.2337/db09-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harding HP, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zinszner H, et al. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marciniak SJ, et al. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galehdar Z, et al. Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16938–16948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ohoka N, et al. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. Embo J. 2005;24:1243–1255. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bromati CR, et al. UPR induces transient burst of apoptosis in islets of early lactating rats through reduced AKT phosphorylation via ATF4/CHOP stimulation of TRB3 expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R92–R100. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00169.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li G, et al. Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:783–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seo HY, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced activation of activating transcription factor 6 decreases insulin gene expression via up-regulation of orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3832–3841. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Song B, et al. Chop deletion reduces oxidative stress, improves beta cell function, and promotes cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3378–3389. doi: 10.1172/JCI34587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Franks PW, et al. Replication of the association between variants in WFS1 and risk of type 2 diabetes in European populations. Diabetologia. 2008;51:458–463. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0887-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schafer SA, et al. A common genetic variant in WFS1 determines impaired glucagon-like peptide-1-induced insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sparso T, et al. Impact of polymorphisms in WFS1 on prediabetic phenotypes in a population-based sample of middle-aged people with normal and abnormal glucose regulation. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1646–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marchetti P, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta cells of type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2486–2494. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marselli L, et al. Gene expression profiles of Beta-cell enriched tissue obtained by laser capture microdissection from subjects with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lin JH, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science (New York, N.Y. 2007;318:944–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1146361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rutkowski DT, et al. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS biology. 2006;4:e374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Butler AE, et al. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sakuraba H, et al. Reduced beta-cell mass and expression of oxidative stress-related DNA damage in the islet of Japanese Type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s125-002-8248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rahier J, et al. Pancreatic beta-cell mass in European subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10 Suppl 4:32–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drucker DJ, et al. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yusta B, et al. GLP-1 receptor activation improves beta cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2006;4:391–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Voight BF, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:579–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dupuis J, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42:105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sladek R, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zeggini E, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science (New York, N.Y. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saxena R, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science (New York, N.Y. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scott LJ, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science (New York, N.Y. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]