Abstract

O- or N-arylated aminophenol products constitute a common structural motif in various potentially useful therapeutic agents and/or drug candidates. We have developed a complementary set of Cu- and Pd-based catalyst systems for the selective O- and N-arylation of unprotected aminophenols using aryl halides. Selective O-arylation of 3- and 4-aminophenols is achieved with copper-catalyzed methods employing picolinic acid or CyDMEDA, trans-N,N′-dimethyl-1,2-cyclohexanediamine, respectively, as the ligand. The selective formation of N-arylated products of 3- and 4-aminophenols can be obtained with BrettPhos precatalyst, a biarylmonophosphine-based palladium catalyst. 2-Aminophenol can be selectively N-arylated with CuI, although no system for the selective O-arylation could be found. Coupling partners with diverse electronic properties and a variety of functional groups can be selectively transformed under these conditions.

Introduction

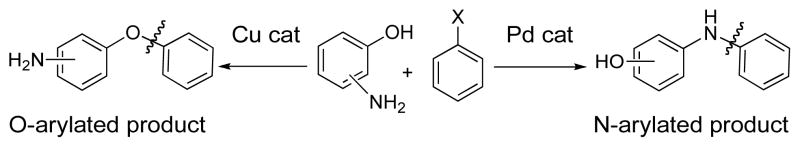

Transition metal-catalyzed carbon-heteroatom bond-forming reactions are widely used in industry and academia in pharmaceutical research, materials synthesis, and process development.1–7 Over the past few years our laboratory has focused on the development of effective and user-friendly systems for Pd- and Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.1,8,9 The substrate scope and generality of these processes has improved to the point where many chemoselective C-O, C-N and C-C coupling reactions can be performed without the need to employ protecting groups. For example, we have reported the selective N- or O-arylation of aminoalcohols10,11 and the C- or N-arylation of oxindoles.12 In this context, we considered aminophenol derivatives to be interesting targets for chemoselective metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions with aryl halides (Scheme 1) because of the difference in acidity of PhOH (pKa ~ 18 in DMSO) and PhNH2 (pKa ~ 31 in DMSO).13

Scheme 1.

Cu- and Pd-catalyzed O- and N-arylation of aminophenol

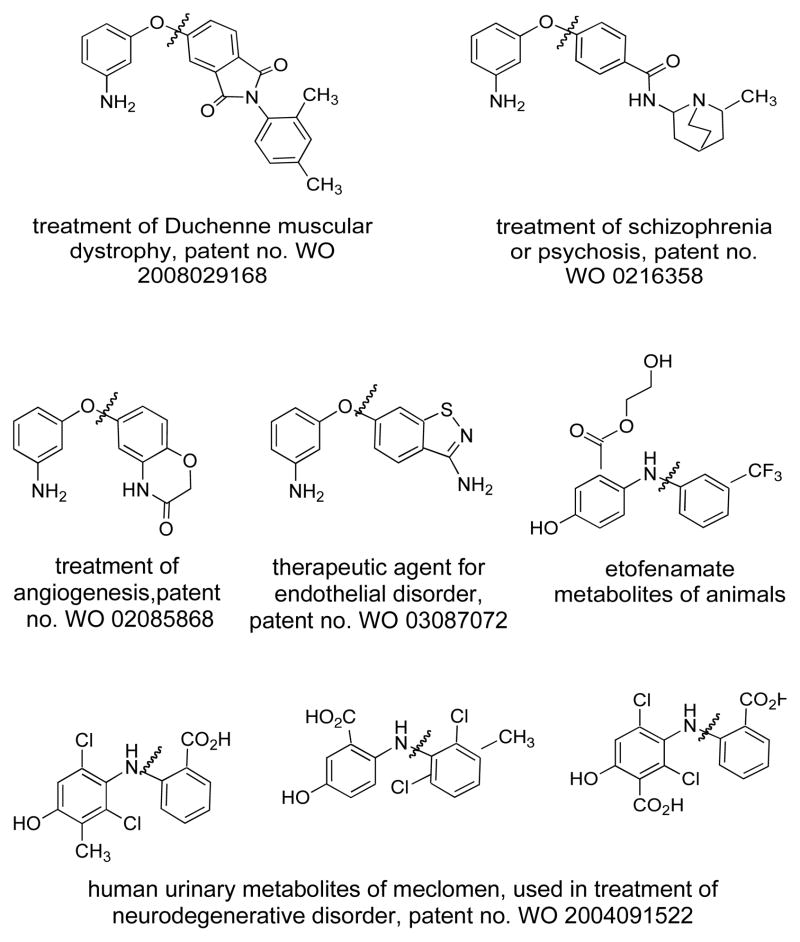

O- or N-arylated aminophenol products constitute a common structural motif in various potentially useful therapeutic agents and/or drug candidates (Figure 1).14–22 They have also been applied as building blocks for the preparation of organic materials.23 We were interested in developing a catalytic system capable of selectively arylating either the nitrogen or the oxygen of the different isomers of aminophenols.

Figure 1.

Biorelevant O- and N-arylated aminophenol derivatives

Results

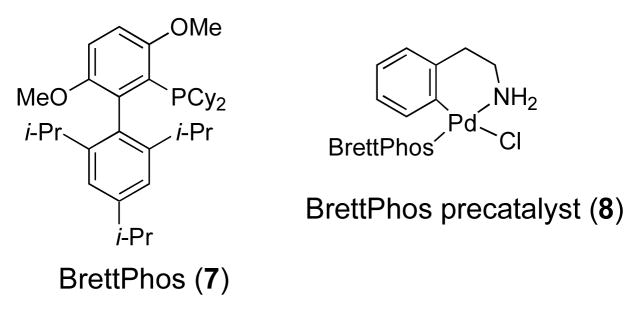

Cu-Catalyzed O-Arylation of 3-Aminophenol

We began our studies by examining the selective O- or N-arylation of 3-aminophenol. The use of previously published conditions for Cu- or Pd-catalytzed O-arylation reactions of phenols 3,4,24 met with limited success. Formation of the N-arylated product or a mixture of N- and O-arylated products was observed.

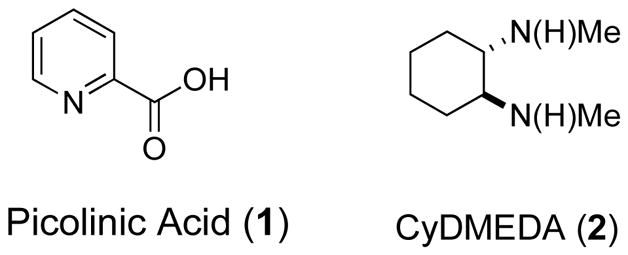

After some experimentation, we discovered that a copper catalyst derived from 5 mol% CuI, 10 mol% picolinic acid 1 (Figure 2),25,26 and 2.0 mmol K3PO4 in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) could catalyze the O-arylation of 3-aminophenols with aryl iodides in excellent yields and with high levels of chemoselectivity under mild conditions (Table 1, entry 1).

Figure 2.

Ligands used in these studies for copper catalysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of various ligands in the coupling of 3-aminophenol with iodobenzenea

1.5 mmol 3-aminophenol, 1.0 mmol iodobenzene, 2.0 mmol K3PO4, 10 mol% CuI, 20 mol% ligand, 3.0 mL DMSO, 80 °C, 23 h.

GC-yield.

Using these reaction conditions, no N-arylated products were detected by GC-MS analysis of the crude reaction mixture. Reactions employing various other ligands (Table 1) including pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid 3,27 and its derivatives 4, and 5 as well as proline 6,28 under otherwise identical reaction conditions gave N-arylated or mixtures of N- and O-arylated products.

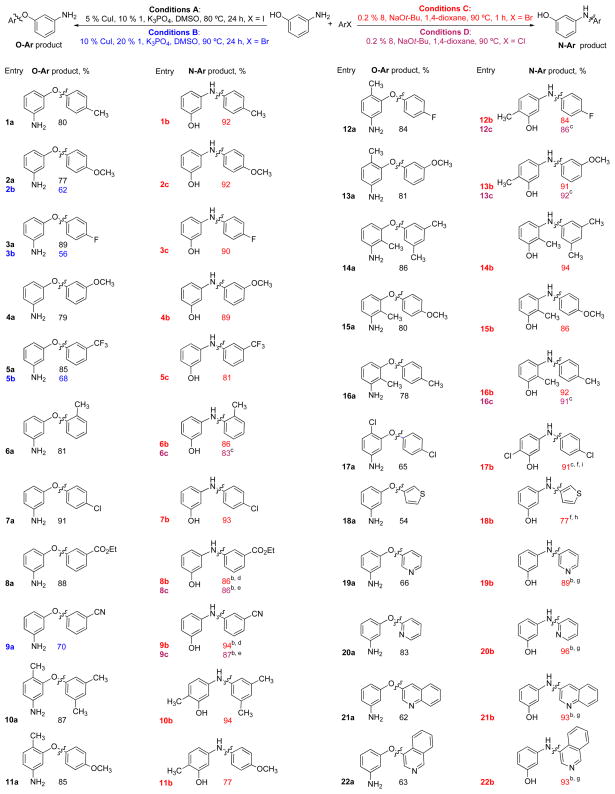

To probe the generality of this system using 1 as the ligand, we evaluated the coupling of compounds with different electronic and steric demands. Electron-rich, -deficient and -neutral aryl iodides (Table 2) were all suitable substrates and provided the corresponding diaryl ethers in good to excellent yields. In addition, the presence of an ortho methyl group on the aryl halide was well tolerated (Table 2, entry 6a). Substrates bearing ester and nitrile groups were also transformed to the desired products in good yield (Table 2, entries 8a and 9a).

Table 2.

Cu- and Pd- catalyzed arylation of 3-aminophenolsa

|

Isolated yield, average of two runs.

K2CO3, t-BuOH, 110 °C.

70 min.

80 min.

90 min.

24 h.

1 % 7, 1% 8, 24 h.

110 °C.

1 % 8

Aryl bromides could be utilized in these cross coupling reactions, albeit in lower yields (Table 2, entries 2b, 3b, 5b, 9a, 21a and 22a). Aryl chlorides were not suitable coupling partners under these conditions. The differences in reactivity allowed us to selectively couple 4-chloroiodobenzene to generate the corresponding O-arylated products (Table 2, entries 7a and 17a).

We next explored the O-arylation of both 2- and 6-substituted 3-aminophenols. We found that 5-amino-o-cresol could be efficiently O-arylated with substituted aryl iodides (Table 2, entries 10a, 11a, 12a and 13a). The efficiency of this system was further demonstrated by the selective O-arylation of 3-amino-o-cresol with several substituted aryl iodides (Table 2, entries 14a, 15a and 16a). No N-arylated products were observed in the crude reaction mixtures. The cross-coupling reactions of iodopyridines, iodothiophenes, bromoquinolines and bromoisoquinolines with 3-aminophenols were also explored. Using the standard protocol, we were able to obtain heteroaryl ethers in good yield (Table 2, entries 18a, 19a, 20a and 21a). Reduction product (ArI → ArH) was detected in some cases, e.g. pyridine (15 % GC-yield, entry 19a, Table 2) and quinoline (10 % GC-yield, entry 21a, Table 2) and constituted the major byproduct.

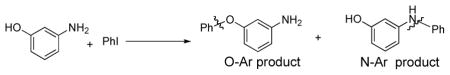

Pd-Catalyzed N-Arylation of 3-Aminophenol

Recently we reported that precatalyst 8 based on BrettPhos 7 provides a highly efficient catalyst for C-N cross-coupling reactions (Figure 3).29,30 Such catalysts have been shown to allow the coupling of anilines and aryl halides with short reaction times and low catalyst loadings. We found that employing 0.2 mol% 8 with NaOt-Bu in 1,4-dioxane at 90 °C in the reactions of aryl bromides and chlorides with 3-aminophenols cleanly led to the N-arylation products. This, combined with our above-described copper method constitutes an orthogonal set of catalysts for the selective N-(Pd) or O-(Cu) arylation of 3-aminophenols.

Figure 3.

Ligand and precatalyst used in these studies for palladium catalysis.

As shown in Table 2, electron-rich, -deficient and -neutral aryl bromides underwent N-arylation in excellent yields and with high levels of chemoselectivity using 8 (Table 2, entries 1b, 2c, 3c, 4b and 5c). The selective N-arylation of 3-aminophenol was also successful with 2-substituted aryl halides (Table 2, entry 6b). The use of NaOt-Bu precludes the presence of base-sensitive functional groups, however, the weak base K2CO3 can be used in t-BuOH with BrettPhos precatalyst 8 at a slightly higher temperature (110 °C) and with longer reaction times (80 min). A variety of functional groups were tolerated, including an ester and a nitrile (Table 2, entries 8b and 9b).

An aryl chloride could also be present in either the nucleophilic or electrophilic coupling partner (Table 2, entries 7b and 17b). As with O-arylation, substituted aminophenols were successfully N-arylated (Table 2, entries 10b, 11b, 12b, 13b, 14b, 15b, 16b and 17b), thus complementing the Cu-catalyzed O-arylation process described above. Heteroaryl bromides containing pyridines, thiophenes, quinolines and isoquinolines were all selectively N-arylated in good to excellent yields (Table 2, entry 18b, 19b, 20b and 21b).

In all of the cases examined, aryl chlorides behaved similarly to aryl bromides in their selective N-arylation with 3-aminophenols under these conditions (Table 2, entries 6c, 8c, 9c, 12c, 13c and 16c). The faster rate of oxidative addition of LPd(0) to the aryl bromide allowed for the selective amination of chlorobromo substrates (Table 2, entries 7b and 17b).

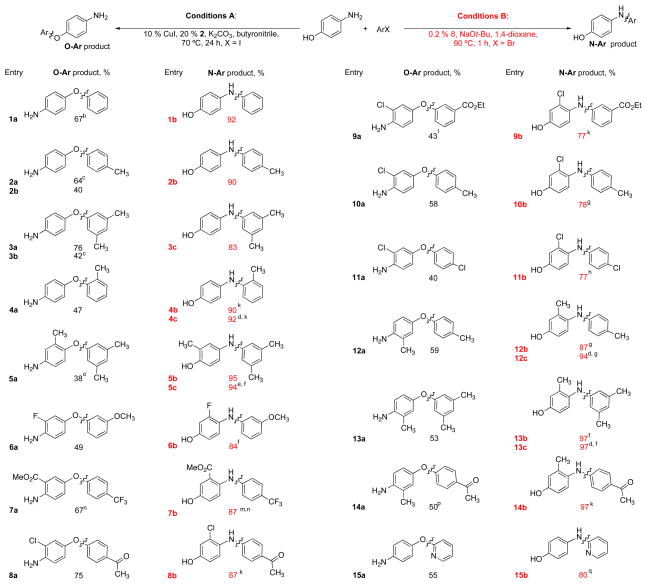

Cu-Catalyzed O-Arylation of 4-Aminophenol

Following our success with 3-aminophenol, we set out to find conditions that would allow analogous transformations of 4-aminophenol. While the combination of CuI with 1 promotes the O-arylation of 4-aminophenol in 1,4-dioxane with K3PO4 or Cs2CO3, the reactions proceed in low yield. The use of all the ligands shown in Table 1 resulted in formation of the N-arylated and N,N-diarylated products and a trace of the O-arylated products. Next, a series of ligands previously employed by our group in copper-catalyzed reactions were examined.27,31 We found that the O-arylated 4-aminophenol could be isolated as the major product with trans-N,N′-dimethyl-1,2-cyclohexanediamine (CyDMEDA 2, Figure 2),9,32–36 using a variety of solvent and base combinations. Unfortunately, formation of the reduction product (ArI → ArH, e.g, 14 % GC-yield of m-xylene in entry 3a and 16 % GC-yield of anisole in entry 6a, Table 3) and/or traces of N-arylated product could not be completely prevented in most of the cases examined. Further optimization indicated that the combination of butyronitrile as solvent and K2CO3 as base afforded the highest yield and selectivity for O-arylation. Increasing the temperature above 70 °C led to increased reduction of the aryl halide; decreasing the reaction temperature resulted in slower reaction rates. In a typical protocol, 10 mol% CuI, 20 mol% 2 and K2CO3, in butyronitrile at 70 °C were employed along with the aryl iodide and 4-aminophenol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cu- and Pd- catalyzed arylation of 4-aminophenolsa

|

Isolated yield, average of two runs.

2% of the N-arylated product was observed.

ArBr.

ArCl.

80 min.

3 h.

24 h.

K2CO3, t-BuOH.

1 % 8.

1 % 8, 24 h.

1% 8, K2CO3, t-BuOH, 24 h.

48 h.

ArCl, K2CO3, t-BuOH, 3 h.

0.5 mmol scale.

16 % of the N-arylated product was observed.

3% of the N-arylated product was observed.

1 % 7, 1% 8, K2CO3, t-BuOH, 110 °C, 24 h.

As shown in Table 3, under these conditions the reaction tolerates a number of different substituents either on the nucleophile or electrophile. Systematic variation of the substituents on the aryl halide from the para (entry 2a) to the meta (entries 3a) and ortho positions (entry 4a) provided the corresponding O-arylated products of 4-aminophenol. Functional groups such as ketones and esters, both on the aminophenol and on the aryl iodide, were tolerated (Table 3, entries 7a, 8a, 9a and 14a). Heteroaryliodides such as 2-iodopyridines could be O-arylated in good yield (Table 3, entry 15a). Substituted 4-aminophenols were shown to provide the desired products in moderate yields (Table 3, entries 5a, 6a, 7a, 8a, 9a, 10a, 11a, 12a, 13a and 14a) as did 4-aminophenols with fluoride or chloride substituents (Table 3, entry 6a, 8a, 9a, 10a and 11a). The reaction of 2-methyl-4-aminophenol (entry 5a) gave a low yield of O-arylated product and produced a significant quantity of the N-arylated compound (16%). Here an ortho methyl substituent is problematic, possibly due to reduced binding efficiency of oxygen to the Cu center owing to steric interactions. We currently have no explanation for why complete selectivity is seen with 5-amino-o-cresol (Table 2, entry 10a), but not with 2-methyl-4-aminophenol (Table 3, entry 5a).

As with 3-aminophenol, the use of aryl bromides as coupling partners (Table 3, entries 2b and 3b) resulted in lower yields of the desired products.

Pd-Catalyzed N-Arylation of 4-Aminophenol

As is the case of 3-aminophenols, we found that the use of 0.2 mol% 2 in combination with 2.5 mmol NaOt-Bu (or K2CO3) in 1,4-dioxane (or t-BuOH) at 110 °C (Table 3) catalyzed the selective N-arylation of 4-aminophenols with aryl bromides and chlorides. As can be seen, 4-aminophenol and substituted analogues could be coupled with a variety of substituted aryl halides to give the N-arylated products in excellent yields and with high levels of chemoselectivity. No products resulting from O-arylation, reduction, or homocoupling of the aryl halide were observed by GC-MS analysis of the crude reaction mixtures.

Of particular interest is entry 4b (Table 3) in which an ortho-substituted aryl halide was chemoselectively coupled at the N terminus of 4-aminophenol. This electrophile is an excellent substrate for Pd-catalyzed diaryl ether synthesis,24,37,38 emphasizing the preference of the palladium catalyst in this system for C-N over C-O bond formation. 4-Amino-3-chlorophenol could be selectively N-arylated with keto-, ester-, or chloro-substituted aryl halides (Table 3, entries 8b, 9b, 10b and 11b). The presence of an ortho fluoride group in the aminophenol moiety did little to decrease the efficiency of its coupling reaction (Table 3, entry 6b). Not surprisingly, 4-aminophenol could also be selectively N-arylated with aryl chlorides (Table 3, entries 4c, 5c, 12c and 13c).

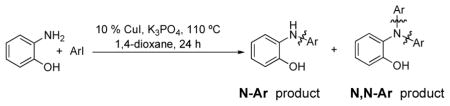

Arylation of 2-Aminophenol

The desired N-arylation reaction of 2-aminophenol could be achieved by using 2-aminophenol itself as the ligand for copper (Table 4), giving a good to excellent yield of the mono N-arylation product in 1,4-dioxane at 110 °C. The formation of 3–7% N,N-diarylated product, however, was unavoidable in most of the cases.39 In all the examples in Table 4, not only was the desired N-arylated product produced in excellent yield, but no trace of the O-arylated product was observed in the crude reaction mixture. The method was also extended to iodopyridines as electrophile (Table 4, entries 6, 7 and 8) in good to excellent yields.

Table 4.

N-arylation of 2-aminophenola

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aminophenol | arene | entry | yield (%)b N-Ar | yield (%)b N, N-Ar |

|

|

1 | 92 | 3 |

|

|

2 | 90 | 5 | |

|

|

3 | 82 | 7 | |

|

4 | 90 | 3 | |

|

5 | 95 | 3 | |

|

|

6 | 80 | ||

|

|

7 | 94 | ||

|

|

8 | 83b | ||

Isolated yield, average of two runs.

ArBr.

We were unable to find conditions for selective O-arylation of 2-aminophenols presumably due to its abiltity to form a five-membered chelate ring39 with Cu or Pd. Following screening of many combinations of ligands, solvents, and bases, we found that 10 mol% CuI in DMSO at 120 °C, with 1 equiv of 1 as a ligand for copper to outcompete 2-aminophenol as ligand, provided only a 20 % GC yield of the desired O-arylation. Note that a similar result was seen in our previous studies on the Cu-catalyzed arylation of aminoalcohols.10

Intial Studies Toward Determining the Origin of the Observed Selectivity

When we carried out a competition experiment in which we reacted a 1:1 mixture of aniline:phenol with chlorobenzene in the presence of 8 (80 °C, 30 min), diphenylamine was the sole product; no formation of diphenylether was observed. Presumably under these conditions Pd-O bond formation is faster than Pd-N bond formation. However, this step is reversible and reductive elimination to form C-N bonds is much faster than that to form C-O bonds.24,37,40–44

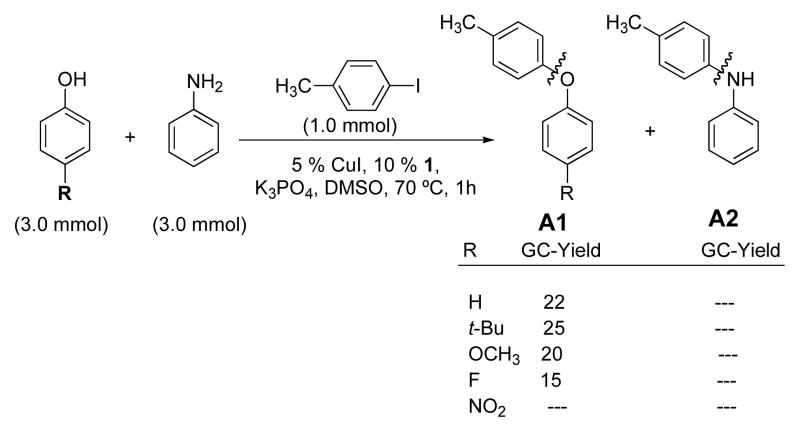

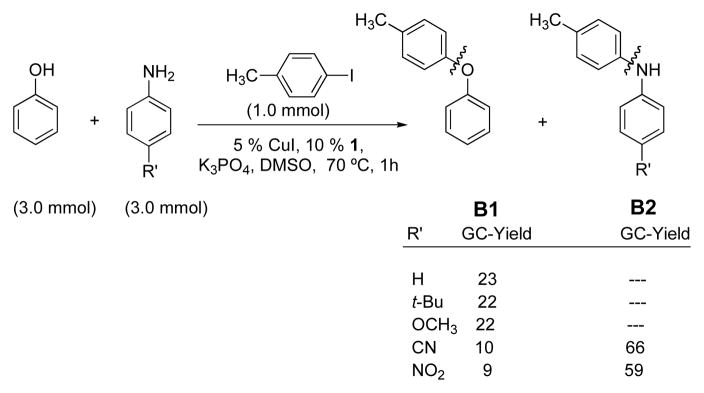

In the reaction between a 1:1 mixture of aniline:p-substituted phenol and 4-iodotoluene with a catalyst sytem based on CuI and picolinic acid 1 only diaryl ethers, p-tolOAr A1 and no N-arylation products, p-tolN(H)Ph A2, were obtained (Scheme 3). Similarly, in analogous competition experiments with a 1:1 mixture of phenol:p-substituted aniline reacting with 4-iodotoluene only diaryl ether B1 was again observed when the aniline substituent R′ = H, t-Bu and OCH3 (Scheme 4). However, in competition experiments between 1:1 phenol:electron-deficient anilines where the aniline substituent R′ = CN and NO2, (Scheme 4), diarylamines, p-tolN(H)Ar B2 were obtained as the major product (B1:B2 ~ 1:7).

Scheme 3.

Competition experiments with 1:1 aniline: substituted phenol.

Scheme 4.

Competition experiments with 1:1 phenol:p-substituted aniline.

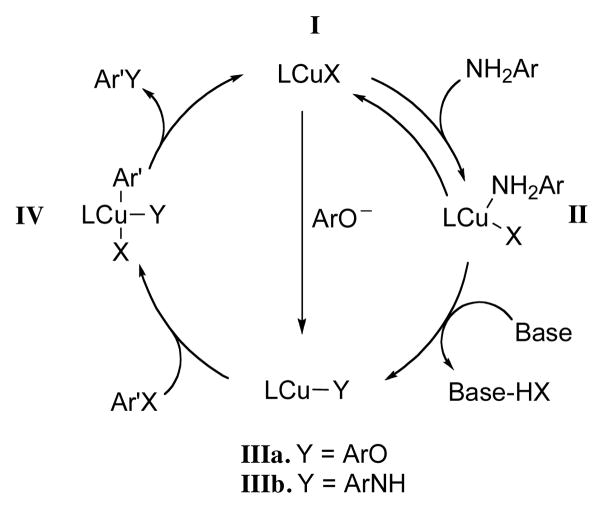

Previous studies of Cu-catalyzed C-N bond formation with amides suggest that the binding of the nucleophile to the ligand-copper complex I to form II facilitates its deprotonation to produce complex III prior to aryl halide activation (Scheme 2).45,46 Under our reaction conditions the phenol is converted to the phenoxide prior to binding to the copper center. In contrast, the free aniline is not deprotonated under these conditions. If the equilibration between IIIa and IIIb is slow relative to their rate of oxidative addition, the relative rate of formation of IIIa and IIIb should be selectivity determining. This is also consistent with our observation that in the competition experiments (see above) anilines with electron-withdrawing substituents give mainly diarylamine: once the acidity of the ArNH2 is enhanced with an electron-withdrawing group so that its pKa is comparable to that of phenol,13 the free aniline can be deprotonated under the reaction conditions and the resulting anilide ion is comparable in nucleophilicty to the phenoxide.47 In this instance, equilibration between IIIa and IIIb presumably is faster than oxidative addition. Little is known about the relative rate of oxidative addition of IIIa and IIIb. However, Paine has demonstrated that electron-deficient diaryl amines react faster than electron-rich ones.48

Scheme 2.

Catalytic cycle for Cu-mediated coupling of aryl halides and nucleophiles.

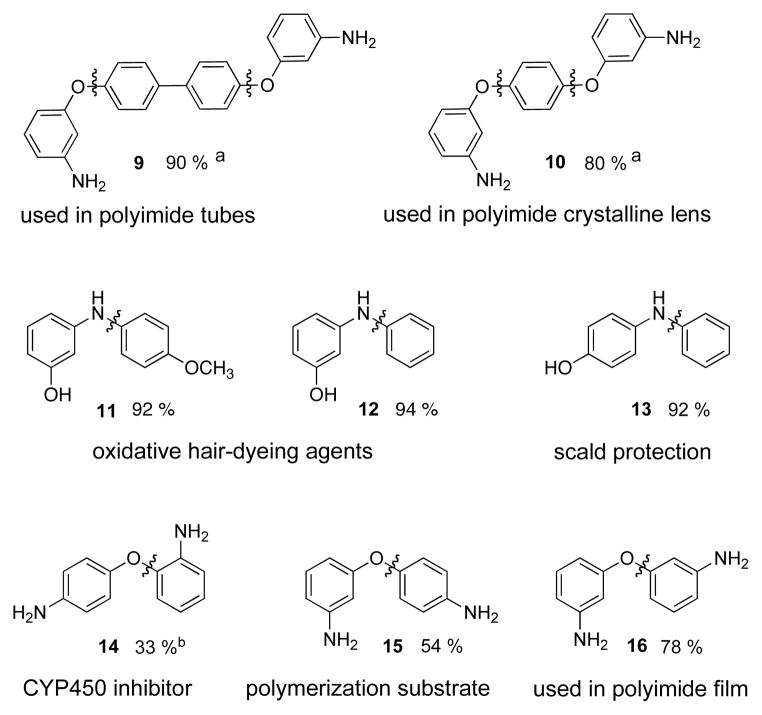

Application of This Methodology

This methodolgy is applicable to the synthesis of a number of potentially useful compounds (Figure 4). Examples of interest include 9, used in the synthesis of polyimide tubes,49 and 10, found in polyimide crystalline lenses,50 both of which can be generated in good yields by reacting 3-aminophenol and the appropriate diiodoarene. Compound 11 (Table 2, entry 2c) and 12, oxidative hair dyeing agents,51 13, protection from scald,52 14, a cytochrome P450 (CYP450) inhibitor,53 15, a polymerization substrate,50 and 16, used in polyimide films,50 were also prepared using our Cu-catalyzed O-arylation method.

Figure 4.

Application of the Cu-catalyzed selective O-arylation of aminophenols to the preparation of interesting compoundsc

a3.0 mmol 3-aminophenol, 10 mol% CuI, 20 mol% 1, 90 °C. b2.0 mmol 4-aminophenol, 10 mol% CuI, 20 mol% 2, K2CO3, butyronitrile, 70 °C. cIsolated yield, average of two runs, 1.2 mmol 3-aminophenol, 1.0 mmol aryl iodide, DMSO, 2.0 mmol K3PO4.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed an efficient and complementary set of Cu- and Pd-based catalyst systems for the selective O- and N-arylation of unprotected aminophenols using aryl halides. Selective O-arylation of 3- and 4-aminophenols is achieved with copper-catalyzed methods employing picolinic acid 1 or CyDMEDA 2, respectively, as the ligand. The selective formation of N-arylated products of 3- and 4-aminophenols could be obtained with BrettPhos precatalyst 8. 2-Aminophenol could be selectively N-arylated with CuI, although no system for the selective O-arylation could be found. Coupling partners with diverse electronic properties and a variety of functional groups can be selectively transformed under these conditions. These methods are likely to find considerable application due to the presence of both N- and O-arylated aminophenols in important organic compounds. Further studies in the chemoselective arylation of different functional groups and the origin of their selectivity are ongoing in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This activity is supported by an educational donation provided by Amgen (postdoctoral fellowship to D.M.) and by funds from the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM-58160). We are grateful to Dr. David Surry and Dr. Tom Kinzel for comments and help with this manuscript. The NMR instruments used for this study were furnished by funds from the National Science Foundation (CHE 9808061 and DBI 9729592).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new and known compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Martin R, Buchwald SL. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1461–1473. doi: 10.1021/ar800036s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang L, Buchwald SL. In: Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. 2. de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley SV, Thomas AW. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:5400–5449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beletskaya IP, Cheprakov AV. Coord Chem Rev. 2004;248:2337–2364. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartwig JF. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1534–1544. doi: 10.1021/ar800098p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma DW, Cai QA. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1450–1460. doi: 10.1021/ar8000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evano G, Blanchard N, Toumi M. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3054–3131. doi: 10.1021/cr8002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:6338–6361. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klapars A, Huang XH, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7421–7428. doi: 10.1021/ja0260465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafir A, Lichtor PA, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3490–3491. doi: 10.1021/ja068926f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Job GE, Buchwald L. Org Lett. 2002;4:3703–3706. doi: 10.1021/ol026655h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman RA, Hyde AM, Huang X, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9613–9620. doi: 10.1021/ja803179s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bordwell FG, Algrim DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:2964–2968. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bird TGC. WO 2002085868. Patent PCT Int Appl. 2002

- 15.Furusako S, Satoh T, Nakamura M, Mizuno M, Mori S. WO 2003087072. Patent PCT Int Appl. 2003

- 16.Zavitz K. WO 2004091522. Patent PCT Int Appl. 2004

- 17.Glazko AJ, Chang T, Borondy PE, Dill WA, Young R, Croskey L. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1978;23:S22–S41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuki Y, Dan J, Fukuhara K, Ito T, Nambara T. Chem Pharm Bull. 1988;36:1431–1436. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wynne GM, Wren SP, Lecci C. WO 2008029168. Patent PCT Int Appl. 2008

- 20.Walker DP, Piotrowski DW, Jacobsen JE, Acker BA, Myers JK, Groppi VE., Jr WO 2003070728. Patent PCT Int Appl. 2003

- 21.Myers JK, Groppi VEJ, Piotrowski DW. WO 2002016358. Patent PCT Int Appl. 2002

- 22.Dell HD, Fiedler J, Kamp R, Kurz J, Wunsche C. Archiv Der Pharmazie. 1982;315:416–422. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19823150506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colquhoun HM, Williams DJ, Zhu Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13346–13347. doi: 10.1021/ja027851m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgos CH, Barder TE, Huang XH, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:4321–4326. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolter M, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2001;3:3803–3805. doi: 10.1021/ol0168216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam MS, Lee HW, Chan ASC, Kwong FY. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6192–6194. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altman RA, Anderson KW, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 2008;73:5167–5169. doi: 10.1021/jo8008676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie XA, Cai GR, Ma DW. Org Lett. 2005;7:4693–4695. doi: 10.1021/ol0518838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fors BP, Watson DA, Biscoe MR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13552–13554. doi: 10.1021/ja8055358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fors BP, Davis NR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5766–5768. doi: 10.1021/ja901414u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman RA, Shafir A, Choi A, Lichtor PA, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 2008;73:284–286. doi: 10.1021/jo702024p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antilla JC, Baskin JM, Barder TE, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 2004;69:5578–5587. doi: 10.1021/jo049658b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klapars A, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14844–14845. doi: 10.1021/ja028865v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanon J, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2890–2891. doi: 10.1021/ja0299708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang L, Job GE, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2003;5:3667–3669. doi: 10.1021/ol035355c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antilla JC, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11684–11688. doi: 10.1021/ja027433h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shelby Q, Kataoka N, Mann G, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10718–10719. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarz N, Pews-Davtyan A, Alex K, Tillack A, Beller M. Synthesis. 2007:3722–3730. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang HF, Li YM, Sun FF, Feng Y, Jin K, Wang XN. J Org Chem. 2008;73:8639–8642. doi: 10.1021/jo8015488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frlan R, Kikelj D. Synthesis. 2006:2271–2285. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartwig JF. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1936–1947. doi: 10.1021/ic061926w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Backvall JE, Bjorkman EE, Pettersson L, Siegbahn P. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:4369–4373. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartwig JF. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:852–860. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann G, Incarvito C, Rheingold AL, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3224–3225. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strieter ER, Bhayana B, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:78–88. doi: 10.1021/ja0781893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tye JW, Weng Z, Johns AM, Incarvito CD, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9971–9983. doi: 10.1021/ja076668w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawyer JS, Schmittling EA, Palkowitz JA, Smith WJ. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6338–6343. doi: 10.1021/jo980800g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paine AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1496–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin Y, Chen SW, Guo XX, Fang JH, Tanaka K, Kita H, Okamoto KI. High Perform Polym. 2006;18:617–635. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamai S, Yamaguchi A, Ohta M. Polymer. 1996;37:3683–3692. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rose D, Meinigke B. 19719605. Ger Offen DE. 1998

- 52.Rudell DR, Mattheis JP, Fellman JK. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:8382–8389. doi: 10.1021/jf0512407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu XC, Liu ZQ, Li SM. Yaoxue Xuebao. 1994;29:589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.