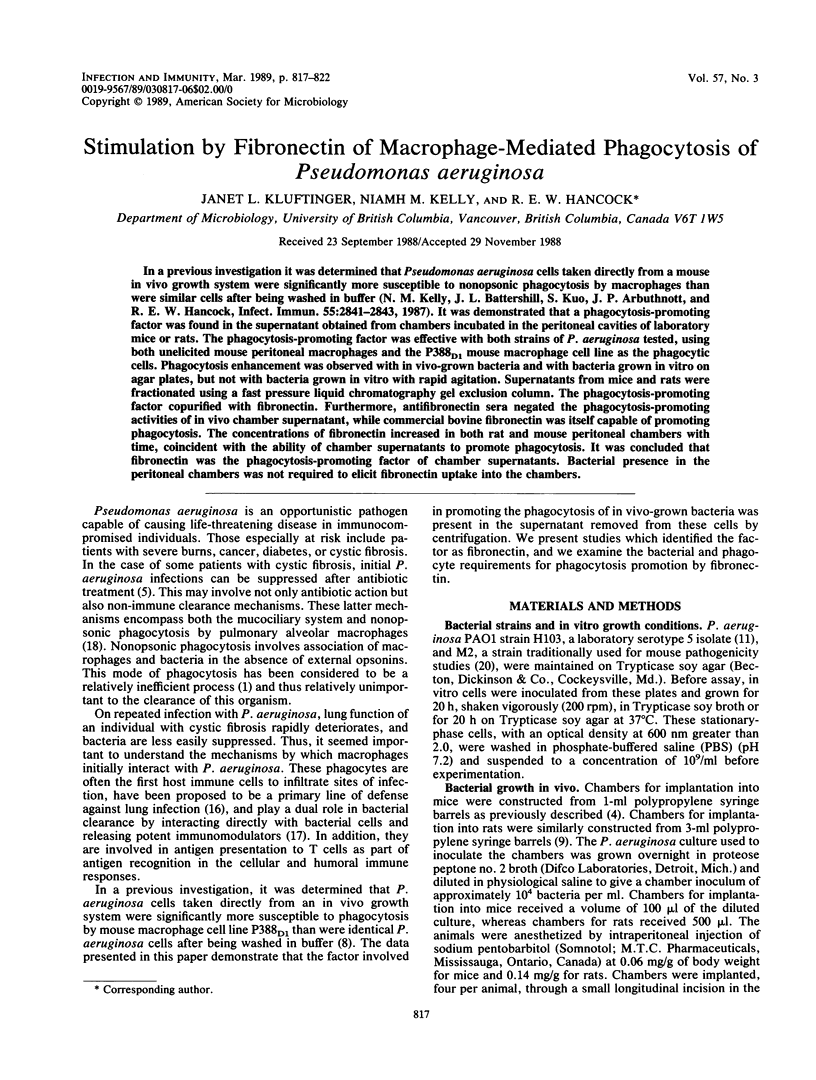

Abstract

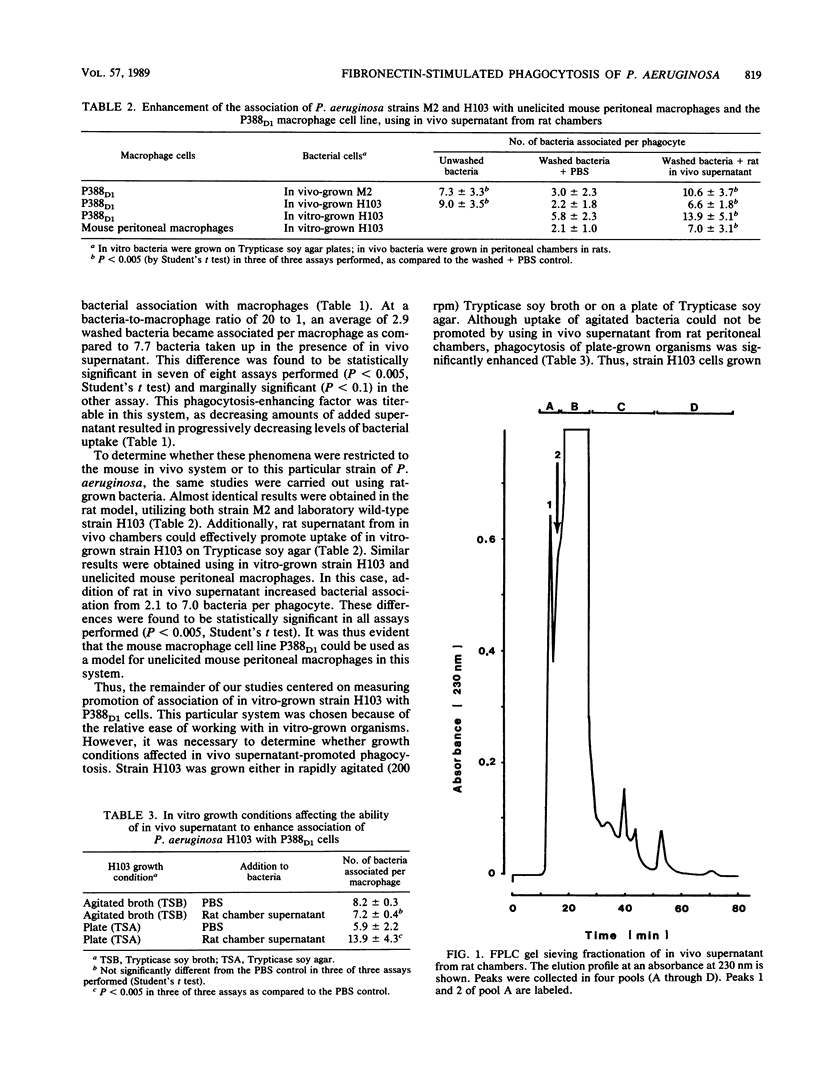

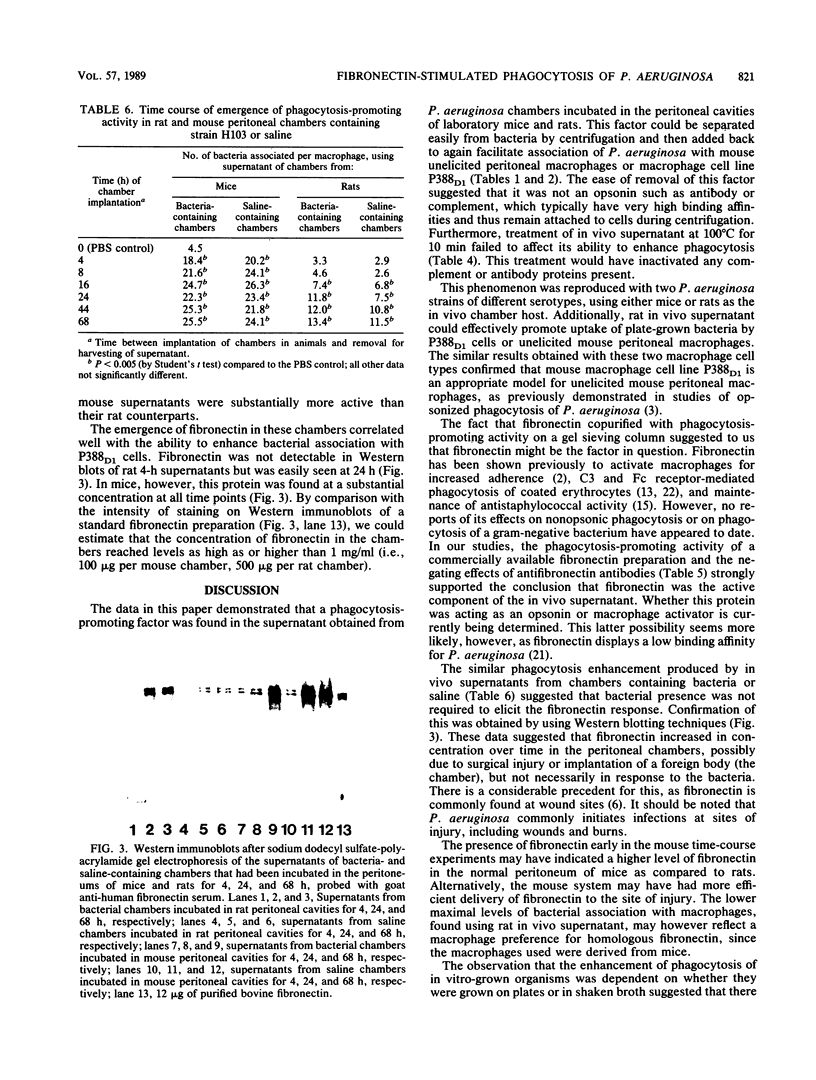

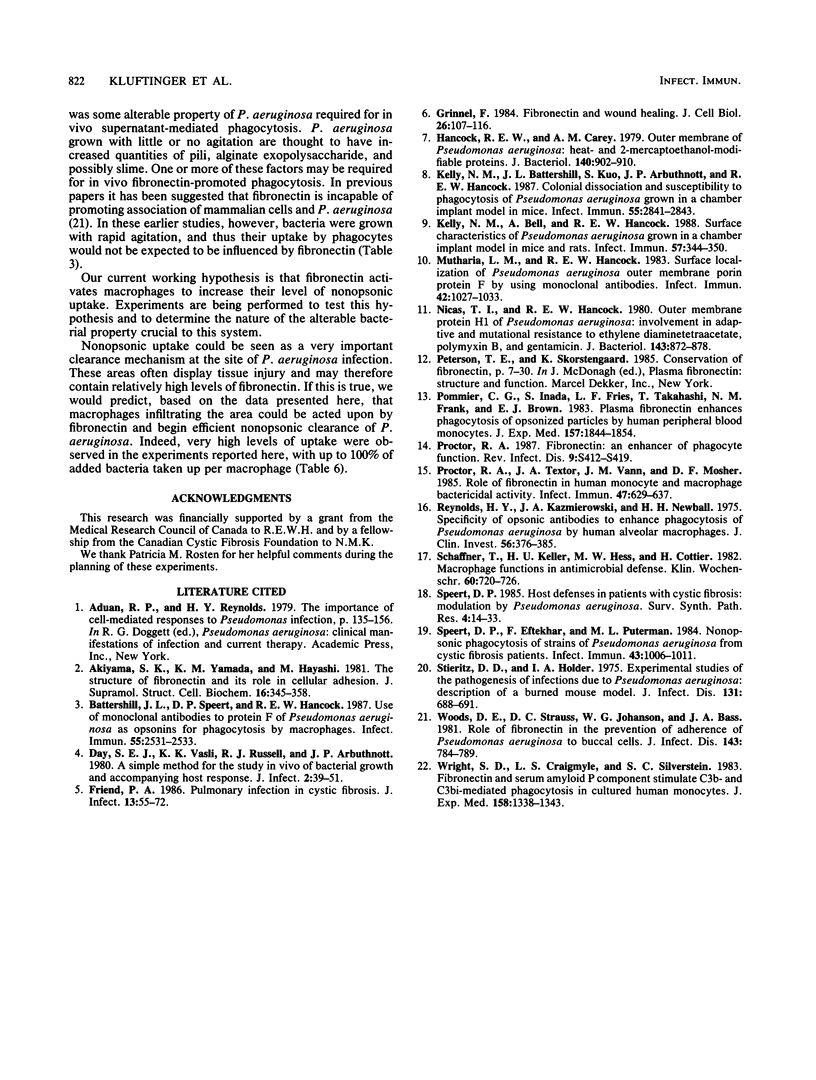

In a previous investigation it was determined that Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells taken directly from a mouse in vivo growth system were significantly more susceptible to nonopsonic phagocytosis by macrophages than were similar cells after being washed in buffer (N. M. Kelly, J. L. Battershill, S. Kuo, J. P. Arbuthnott, and R. E. W. Hancock, Infect. Immun. 55:2841-2843, 1987). It was demonstrated that a phagocytosis-promoting factor was found in the supernatant obtained from chambers incubated in the peritoneal cavities of laboratory mice or rats. The phagocytosis-promoting factor was effective with both strains of P. aeruginosa tested, using both unelicited mouse peritoneal macrophages and the P388D1 mouse macrophage cell line as the phagocytic cells. Phagocytosis enhancement was observed with in vivo-grown bacteria and with bacteria grown in vitro on agar plates, but not with bacteria grown in vitro with rapid agitation. Supernatants from mice and rats were fractionated using a fast pressure liquid chromatography gel exclusion column. The phagocytosis-promoting factor copurified with fibronectin. Furthermore, antifibronectin sera negated the phagocytosis-promoting activities of in vivo chamber supernatant, while commercial bovine fibronectin was itself capable of promoting phagocytosis. The concentrations of fibronectin increased in both rat and mouse peritoneal chambers with time, coincident with the ability of chamber supernatants to promote phagocytosis. It was concluded that fibronectin was the phagocytosis-promoting factor of chamber supernatants. Bacterial presence in the peritoneal chambers was not required to elicit fibronectin uptake into the chambers.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akiyama S. K., Yamada K. M., Hayashi M. The structure of fibronectin and its role in cellular adhesion. J Supramol Struct Cell Biochem. 1981;16(4):345–348. doi: 10.1002/jsscb.1981.380160405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battershill J. L., Speert D. P., Hancock R. E. Use of monoclonal antibodies to protein F of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as opsonins for phagocytosis by macrophages. Infect Immun. 1987 Oct;55(10):2531–2533. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.10.2531-2533.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day S. E., Vasli K. K., Russell R. J., Arbuthnott J. P. A simple method for the study in vivo of bacterial growth and accompanying host response. J Infect. 1980 Mar;2(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(80)91773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend P. A. Pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. J Infect. 1986 Jul;13(1):55–72. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(86)92325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E., Carey A. M. Outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: heat- 2-mercaptoethanol-modifiable proteins. J Bacteriol. 1979 Dec;140(3):902–910. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.902-910.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly N. M., Battershill J. L., Kuo S., Arbuthnott J. P., Hancock R. E. Colonial dissociation and susceptibility to phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in a chamber implant model in mice. Infect Immun. 1987 Nov;55(11):2841–2843. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2841-2843.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly N. M., Bell A., Hancock R. E. Surface characteristics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in a chamber implant model in mice and rats. Infect Immun. 1989 Feb;57(2):344–350. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.344-350.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutharia L. M., Hancock R. E. Surface localization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane porin protein F by using monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1983 Dec;42(3):1027–1033. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.3.1027-1033.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicas T. I., Hancock R. E. Outer membrane protein H1 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement in adaptive and mutational resistance to ethylenediaminetetraacetate, polymyxin B, and gentamicin. J Bacteriol. 1980 Aug;143(2):872–878. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.872-878.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier C. G., Inada S., Fries L. F., Takahashi T., Frank M. M., Brown E. J. Plasma fibronectin enhances phagocytosis of opsonized particles by human peripheral blood monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983 Jun 1;157(6):1844–1854. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.6.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. A. Fibronectin: an enhancer of phagocyte function. Rev Infect Dis. 1987 Jul-Aug;9 (Suppl 4):S412–S419. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_4.s412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. A., Textor J. A., Vann J. M., Mosher D. F. Role of fibronectin in human monocyte and macrophage bactericidal activity. Infect Immun. 1985 Mar;47(3):629–637. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.629-637.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds H. Y., Kazmierowski J. A., Newball H. H. Specificity of opsonic antibodies to enhance phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by human alveolar macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1975 Aug;56(2):376–385. doi: 10.1172/JCI108102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner T., Keller H. U., Hess M. W., Cottier H. Macrophage functions in antimicrobial defense. Klin Wochenschr. 1982 Jul 15;60(14):720–726. doi: 10.1007/BF01716563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speert D. P., Eftekhar F., Puterman M. L. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun. 1984 Mar;43(3):1006–1011. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1006-1011.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speert D. P. Host defenses in patients with cystic fibrosis: modulation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Surv Synth Pathol Res. 1985;4(1):14–33. doi: 10.1159/000156962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieritz D. D., Holder I. A. Experimental studies of the pathogenesis of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: description of a burned mouse model. J Infect Dis. 1975 Jun;131(6):688–691. doi: 10.1093/infdis/131.6.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods D. E., Straus D. C., Johanson W. G., Jr, Bass J. A. Role of fibronectin in the prevention of adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to buccal cells. J Infect Dis. 1981 Jun;143(6):784–790. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.6.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. D., Craigmyle L. S., Silverstein S. C. Fibronectin and serum amyloid P component stimulate C3b- and C3bi-mediated phagocytosis in cultured human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983 Oct 1;158(4):1338–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.4.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]