Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells exposed to cisplatin (CIS) displayed a dramatic ATM-dependent phosphorylation of ΔNp63α that leads to the transcriptional regulation of downstream mRNAs. Here, we report that phospho (p)-ΔNp63α transcriptionally deregulates miRNA expression after CIS treatment. Several p-ΔNp63α-dependent microRNA species (miRNAs) were deregulated in HNSCC cells upon CIS exposure, including miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a (downregulated) and miR-630 (upregulated). Deregulation of miRNA expression led to subsequent modulation of mRNA expression of several targets (TP53-S46, HIPK2, ATM, CDKN1A and 1B, CASP3, PARP1 and 2, DDIT1 and 4, BCL2 and BCL2L2, TP73, YES1, and YAP1) that are involved in the apoptotic process. Our data support the notion that miRNAs are critical downstream targets of p-ΔNp63α and mediate key pathways implicated in the response of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs.

Keywords: p63, cisplatin, squamous cell carcinomas, DICER1, microRNA

Cisplatin (CIS) is a chemotherapeutic agent often used in the treatment of human cancers because of its ability to induce cell death in neoplastic cells.1 However, tumors eventually become resistant to platinum chemotherapy.1, 2 CIS induces DNA damage, leading to the accumulation of activated members of the tumor protein (TP) 53 family (TP53, TP63, and TP73).3, 4, 5, 6, 7 When induced, TP53, TP63, and TP73 alter the transcription of a large set of downstream target genes, controlling cell-cycle arrest, cell death, increased DNA repair, inhibition of angiogenesis, and so on.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 MicroRNA species (miRNAs) are small 18–24-nucleotide non-coding RNAs that act through the RNA interference pathway and repress target gene expression largely by modulating translation and mRNA stability.13, 14 miRNA precursors (pri-miRNAs) are processed in the nucleus, and the hairpin products are then cleaved by the double-stranded ribonuclease, DICER1, in the cytoplasm to generate mature miRNAs.14, 15 Altered expression of miRNA genes has been found in a variety of tumor types and has shown the oncogenic, tumor-suppressive, or apoptotic potential of specific miRNAs.16, 17, 18, 19 Certain miRNAs were shown to mediate the induction of cell death, cell cycle arrest, and senescence and contribute to epithelial stem cell maturation.18, 19, 20

We previously observed that the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells exposed to CIS displayed a dramatic downregulation of ΔNp63α through an ATM-dependent phosphorylation mechanism.21, 22 We also showed that phospho (p)-ΔNp63α is critical for the transcriptional regulation of downstream mRNAs in HNSCC cells.21, 22 In the current study, we present evidence that p-ΔNp63α regulates miRNA expression in CIS-treated HNSCC cells through both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms.

Results

CIS induces the p-ΔNp63α-dependent expression of DICER1

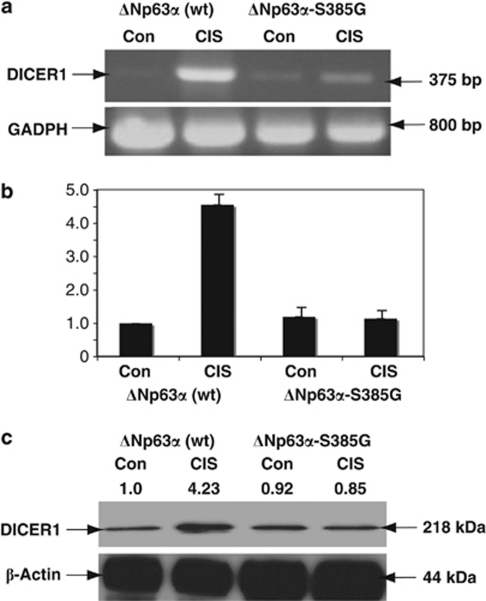

We employed the JHU-029 stable clones, which have been shown to exclusively produce wild-type ΔNp63α or ΔNp63α-S385G with an altered ability to be phosphorylated by ATM kinase.21, 22 Using mRNA expression and ChIP-on-chip arrays, we previously showed that exposure of wild-type ΔNp63α cells to 10 μg/ml CIS for 16 h led to an approximately fivefold upregulation of the double-stranded RNA-specific endoribonuclease, DICER1.22 We found here that upon CIS exposure, the DICER1 expression level is higher (∼4.0- to 4.2-fold) in wild-type ΔNp63α cells than in ΔNp63α-S385G cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

p-ΔNp63α upregulates DICER1 expression upon CIS exposure. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells (p63wt) or ΔNp63α-S385G cells (p63mut) were exposed to Con (−) or 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for 24 h. Total RNA and protein were isolated and analyzed for DICER1 expression. (a) PCR assay. (b) qPCR assay of DICER1 expression. Data were normalized against GAPDH levels and plotted as relative units (RU), with measurements obtained from wild-type ΔNp63α cells treated with Con set as 1. Experiments were performed in triplicate with±S.D. as indicated (P<0.01). (c) Immunoblotting with anti-DICER1 antibodies (levels of DICER1 were quantified and normalized against β-actin protein level, and the values obtained from untreated wild-type ΔNp63α cells are designated as (1)). As loading controls, we used the GAPDH mRNA levels for PCR and the β-actin protein levels for immunoblotting

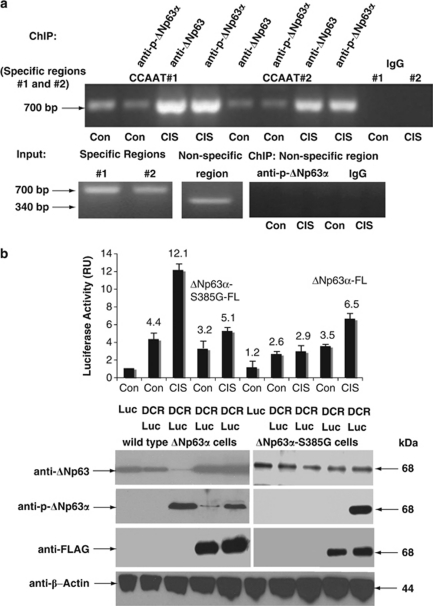

CIS was previously shown to induce binding of the NF-Y/p-ΔNp63α protein complexes to the CCAAT promoter elements.22 The specific CCAAT elements (1, 2, and 3) along with the responsive elements (REs) for p63 (see ref. 23) were found in the 2700-bp human DICER1 promoter identified in the UCSC server using the TFSEARCH software (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html; Computational Biology Research Center, Parallel Application Laboratory, RWCP, Tokyo, Japan). A few cognate REs for various transcription factors (e.g. E2F, C/EBPβ, STAT, Oct-1, and P53) were found present in the DICER1 promoter (Supplementary Figure S1). Using antibodies against both ΔNp63 and p-ΔNp63α for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay, we found that ΔNp63α (in its phosphorylated form) binds to the NF-Y-REs, CCAAT elements 1 and 2 of the DICER1 promoter, whereas no detectable binding was found to the nonspecific region (Figure 2a). We further examined the effect of endogenous p-ΔNp63α on the DICER1 (DCR) promoter (+49 to −871, containing p63RE and CCAAT element 3, Supplementary Figure S1) in wild-type ΔNp63α and ΔNp63α-S385G cells by monitoring luciferase activity from the pDCR-Luc reporter plasmid. We found that the CIS exposure led to a dramatic ∼2.7-fold increase in the DCR-driven luciferase activity in wild-type ΔNp63α cells, whereas no significant changes were observed in ΔNp63α-S385G cells (Figure 2b, graph panel, sample 3 versus 2). Next, wild-type ΔNp63α and ΔNp63α-S385G cells were transfected with the exogenous ΔNp63α-S385G-FL and ΔNp63α-FL constructs, respectively. In contrast to ΔNp63α-S385G-FL, ΔNp63α-FL has undergone the CIS-induced phosphorylation, which was detected with the anti-p-ΔNp63α antibody (Figure 2b, immunoblot panel). We further showed that the competition of exogenous ΔNp63α-S385G with endogenous p-ΔNp63α decreased the CIS-mediated DCR-Luc activity by ∼2.3-fold in wild-type ΔNp63α cells (Figure 2b, graph panel, sample 5 versus 3). However, exogenous p-ΔNp63α-FL increased the CIS-mediated DCR-Luc activity in ΔNp63α-S385G cells, supporting the competition of exogenous p-ΔNp63α with endogenous ΔNp63α-S385G (Figure 2b, graph panel, sample 10 versus 8). Altogether, these data strongly support that the DICER1 promoter is a potential transcriptional target for p-ΔNp63α in HNSCC cells upon CIS exposure.

Figure 2.

p-ΔNp63α binds to the DICER1 promoter sequences and activates the DICER1 promoter activity upon CIS exposure. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were exposed to Con or 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. (a) ChIP assay for the DICER1 promoter was performed using both anti-ΔNp63 and anti-p-ΔNp63α antibodies. A rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG) was used as a negative control for ChIP. CCAAT elements 1 and 2 were amplified using primers covering the specific regions (−1892 to −1191) and (−1421 to −721), respectively, and yielding the 700-bp PCR fragments. Positive controls (Inputs) and a negative control (ChIP using primers for the DICER1 promoter nonspecific region −2639 to −2301 yielding the 340-bp PCR product) were shown. (b) Luciferase reporter activity assay. Wild-type and mutated cells were transfected with 100 ng of the promoterless pGL3 plasmid or pGL3-DCR-Luc plasmid along with 1 ng of the Renilla luciferase plasmid. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were also transfected with 100 ng of the ΔNp63α-S385G-FL expression cassette, whereas ΔNp63α-S385G cells were transfected with 100 ng of the ΔNp63α-FL expression cassette, as indicated. Cells were exposed to Con and 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. Luciferase reporter assays were conducted in triplicate (±S.D., P<0.01). Firefly luciferase activity values were normalized against Renilla luciferase values and resulting values obtained from wild-type ΔNp63α cells with the promoterless pGL3 plasmid and exposed to Con were designated as 1, while fold changes are shown as numerical values. Samples were also tested by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies

CIS deregulates the p-ΔNp63α-dependent expression of miRNAs

Given that DICER1 is a well-known regulator of miRNA biosynthesis and has a central role in the maturation of the miRNAs that contribute to apoptosis15 and tumor suppression,24 we examined the miRNA signature of HNSCC cells exposed to CIS. First, we tested whether the exposure of HNSCC cells to CIS affects the expression of specific miRNAs. Second, we questioned whether p-ΔNp63α is involved in transcriptional regulation of certain miRNAs. We suggest that any overlapping results between these two sets of experiments may indicate which miRNAs are induced by CIS through a p-ΔNp63α-dependent mechanism.

To answer the first question, we exposed wild-type ΔNp63α cells to control medium (Con) or 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. Using total RNA from both cell lines, we performed an miRNA-chip microarray analysis using a chip containing probes to 842 human miRNAs.25 We found that CIS downregulated seven miRNAs (miR-519a, miR-181a, miR-374a, miR-29c, miR-98, miR-22, and miR-18b) from −1.7- to 3.7-fold, and upregulated eight miRNAs (miR-760, miR-185, miR-574, miR-453, miR-297, miR-194, miR-885-3p, and miR-630) from +1.8- to +4.9-fold in HNSCC cells (Supplementary Table SI).

To answer the second question, we utilized the isogenic wild-type ΔNp63α and ΔNp63α-S385G cells.21, 22 Both cell lines were treated with CIS, which has previously been shown to increase the p-ΔNp63α levels.21, 22 Using the miRNA array chip, we thus found dramatic differences in the miRNA expression levels (Supplementary Table SII). miRNAs exhibiting a threefold or greater change in expression were chosen for further study. After CIS exposure, ∼20 miRNA species were upregulated in wild-type ΔNp63α cells (ranging from 3.3- to 7.4-fold, Supplementary Table SII) when compared with ΔNp63α-S385G cells. At the same time, ∼33 miRNAs were downregulated (ranging from 3.4- to 19.2-fold, Supplementary Table SII) in wild-type ΔNp63α cells compared with ΔNp63α-S385G cells after CIS exposure. We found that certain miRNAs were common to both sets (e.g. miR-519a, miR-181a, miR-374a, miR-885-3p, and miR-630), suggesting that these miRNAs were regulated by a CIS-mediated/p-ΔNp63α-dependent transcriptional mechanism. We found no significant differences in miRNA levels between wild-type ΔNp63α cells and ΔNp63α-S385G cells treated with Con (data not shown).

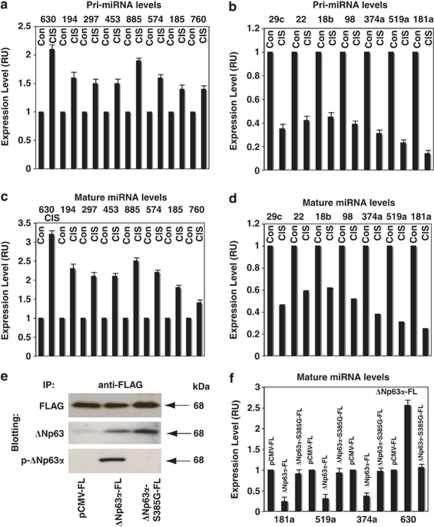

We further tested the pri-miRNA levels in wild-type ΔNp63α cells upon CIS exposure using qPCR analysis. We thus found that the precursors for miR-630, miR-194, miR-297, miR-885-3p, miR-574, miR-185, and miR-760 were upregulated in wild-type ΔNp63α cells upon CIS exposure (Figure 3a), whereas precursors for miR-29c, miR-519a, miR-181a, miR-374a, miR-98, miR-22, and miR-18b were downregulated (Figure 3b). We then found that mature miR-630, miR-194, miR-297, miR-885-3p, miR-574, miR-185, and miR-760 were upregulated (Figure 3c) to a greater extent than their pri-mRNAs (Figure 3a) in wild-type ΔNp63α cells upon CIS exposure. However, mature miR-29c, miR-519a, miR-181a, miR-374a, miR-98, miR-22, and miR-18b were downregulated (Figure 3d) to a lesser degree than their pri-mRNA (Figure 3b) in wild-type ΔNp63α cells upon CIS exposure.

Figure 3.

CIS modulates the expression of the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were exposed to Con or 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. Precursor pri-miRNA (a and b) and mature miRNA (c–e) levels were examined by qPCR assay using TaqMan analysis, and the data were plotted as relative units (RU), using the measurements obtained from the cells treated with Con as 1. Fold changes are presented as numerical values. Experiments were performed in triplicate with±S.D. as indicated (<0.05). (a) Upregulated miRNAs (miR-630, miR-194, miR-297, miR-453, miR-885-3p, miR-574, miR-185, and miR-760). (b) Downregulated miRNAs (miR-29c, miR-519a, miR-181a, miR-374a, miR-98, miR-22, and miR-18b). (c) Upregulated miRNAs (miR-630, miR-194, miR-297, miR-453, miR-885-3p, miR-574, miR-185, and miR-760). (d) Downregulated miRNAs (miR-29c, miR-519a, miR-181a, miR-374a, miR-98, miR-22, and miR-18b). (e and f) ΔNp63α-S385G cells were transfected with an empty pCMV-FL vector, ΔNp63α-FL and ΔNp63α-S385G-Fl expression constructs. Resulting cells were exposed to 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. (e) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of FLAG-tagged ΔNp63α (wt) and (S385G) proteins using anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoblotting with antibodies against the FLAG epitope, ΔNp63 or p-ΔNp63α. (f) Expression levels of indicated mature miRNA (miR-181a, miR-519a, miR-374a and miR-630) were examined by qPCR assay

Interestingly, the mature miRNA/pri-miRNA ratio for individual miRNAs affected by CIS exposure varied as follows: 1.49 for miR-630, 1.42 for miR-194, 1.37 for miR-297, 1.39 for miR-453, 1.59 for miR-885-3p, 1.36 for miR-574, 1.26 for miR-185 and 1.02 for miR-760 (Figures 3a and c), and 1.39 for miR-29c, 1.44 for miR-22, 1.41 for miR-18b, 1.41 for miR-98, 1.31 for miR-374a, 1.35 for miR-519a, and 1.78 for miR-181a (Figures 3b and d). These data suggest that the CIS-induced DICER1 upregulation (Figure 1) is likely to contribute to these intriguing differences in expression levels of pri-miRNAs and mature miRNAs. Although the qPCR data (Figures 3a–d) supported the notion that CIS exposure leads to modulation of certain miRNAs in HNSCC cells, direct evidence of p-ΔNp63α's contribution to the modulation of miRNA expression was missing. ΔNp63α-3385G cells were chosen (to avoid an endogenous p-ΔNp63α background) for a subsequent transfection with an empty pCMV-FL vector and ΔNp63α-FL and ΔNp63α-S385G-FL constructs. Cells were exposed to 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h to ensure the phosphorylation of exogenous ΔNp63α-FL, and the miRNA expression was then quantified using qPCR. We showed that ΔNp63α-FL (recognized by anti-p-ΔNp63α antibody, Figure 3e) decreased the miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a levels, while it increased the miR-630 level (Figure 3f). However, ΔNp63α-S385G-FL (not recognized by anti-p-ΔNp63α antibody, Figure 3e) failed to change the expression levels of these miRNAs compared with control vector (Figure 3f).

p-ΔNp63α transcriptionally regulates miRNA expression upon CIS exposure

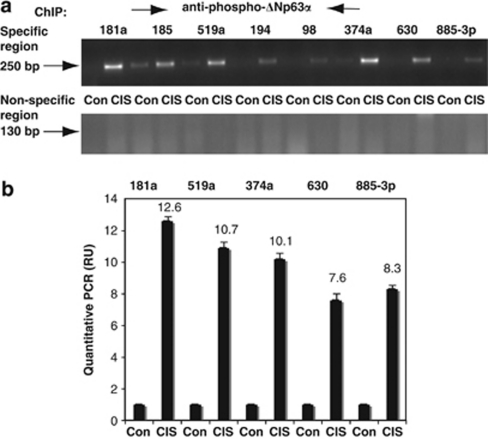

Using ChIP analysis, we found that p-ΔNp63α binds to the promoter sequences of certain miRNAs (miR-181a, miR-519a, miR-374a, miR-630, and miR-885-3p) containing the p63RE and CCAAT elements (Figure 4a, upper panel and Supplementary Figures S2–S6), whereas no detectable binding was observed in nonspecific regions of the miRNA promoters (Figure 4a, lower panel). By qPCR assay, we further showed that the CIS exposure induced binding of p-ΔNp63α to specific regions of the miRNA promoters (miR-181a, miR-519a, miR-374a, miR-630, and miR- 885-3p) to various extents (Figure 4b). We then examined whether global ΔNp63α or p-ΔNp63α was responsible for the transcriptional regulation of miRNA expression in wild-type ΔNp63α cells and ΔNp63α-S385G cells. Using qPCR assay, we quantified the ChIP-PCR data obtained after precipitation of the specific promoter regions with antibodies against both ΔNp63 and p-ΔNp63 (Supplementary Figure S7). ChIP assays performed on wild-type ΔNp63α cells with both antibodies showed that the CIS treatment dramatically induced ΔNp63α binding to the promoters of DICER1, miR-630, and miR-885-3p (Supplementary Figure 7SA), and miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a (Supplementary Figure S7B). However, ChIP assays performed on ΔNp63α-S385G cells showed no such increase in binding of ΔNp63α-S385G to the same promoter sequences (Supplementary Figures S7C and D), suggesting that the altered ability of ΔNp63α to be phosphorylated by ATM kinase substantially impaired the capacity of ΔNp63α to bind specific promoter sequences. Thus, these data support the notion that p-ΔNp63α is likely to regulate transcription of specific miRNAs in HNSCC cells upon CIS exposure.

Figure 4.

ChIP analysis of the p-ΔNp63α protein binding to the miRNA promoters upon CIS exposure. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were exposed to Con or 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. Samples were incubated with the anti-p-ΔNp63α antibody. Precipitated DNAs were amplified with primers for the specific region (a, upper panel, 250-bp PCR product) and nonspecific region (a, lower panel, 130-bp PCR product) for the indicated miRNA promoters. (b) qPCR assay. Using the same primers for specific regions as referred to in Supplementary Figures S2–S6, we assessed the quantitative changes in the p-ΔNp63α protein binding to the indicated miRNA promoter sequences after exposure of cells to Con or 10 μg/ml CIS for 24 h. qPCR experiments were performed in triplicate with ±S.D. as indicated (<0.05). Values obtained with Con were designated as 1, and fold changes are presented as numerical values

DICER1 knockdown attenuates the CIS-mediated response

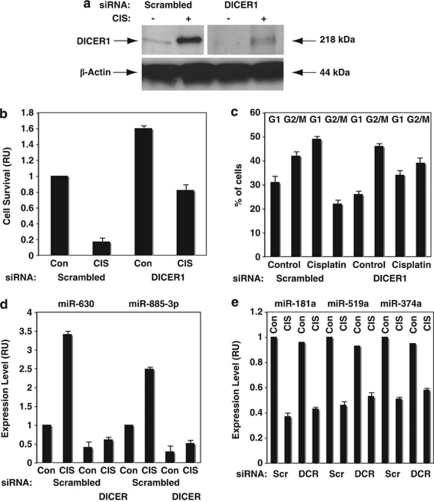

Using DICER1 siRNA, we next substantially knocked down the DICER1 expression (Figure 5a) in wild-type ΔNp63α cells exposed to the Con or 10 μg/ml of CIS for 24 h.

Figure 5.

DICER1 silencing modulates the expression of the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs upregulated after CIS exposure. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (Scr) and DICER1 (DCR) siRNA for 24 h and exposed to Con (−, Con) or 10 μg/ml CIS (+, CIS) for an additional 24 h. (a) DICER1 expression was analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Borders between images indicate that the data were obtained from separate experiments. Loading levels were assessed with anti-β-actin antibody. (b) Cell survival assay. (c) FACS analysis of cells. (d) Expression of mature miR-630 and miR-885-3p. (e) Expression of mature miR-181a, miR-519a and miR-374a. miRNA levels were examined by qPCR assay using TaqMan analysis and the data were plotted as relative units (RU). Values obtained with Con (−, Con) were designated as 1, with fold changes presented as numerical values. Experiments were performed in triplicate with ±S.D. as indicated (<0.05)

We further examined the effect of the DICER1 silencing on the cell survival assessed by MTT assay and showed that the CIS-mediated DICER1 increase led to a dramatic cell death (Figure 5b), whereas DICER1 siRNA almost entirely rescued wild-type ΔNp63α cells from CIS-induced cell death (Figure 5b). FACS analysis further showed that the CIS exposure led to a marked increase in G1 cell population and a corresponding decrease of G2/M cells at 48 h after transfection with scrambled siRNA (Figure 5c). However, when cells were transfected with DICER1 siRNA, G1 cell population decreased, whereas G2/M cell population increased, suggesting the role for DICER1 in cell cycle arrest regulation (Figure 5c).

We next showed that DICER1 siRNA dramatically upregulated miR-630 and miR-885-3p compared with a scrambled siRNA (Figure 5d). This finding suggests a cumulative or synergistic effect of the DICER1-dependent miRNA maturation after the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNA transcriptional activation. However, the expression levels of miR-181a, miR-519a, or miR-374a appeared to be minimally affected by siRNA against DICER1 (Figure 5e), suggesting an opposing (antagonistic) effect of DICER1-dependent miRNA maturation after the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNA transcriptional repression.

Potential mRNA targets of the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs under CIS treatment

Taking into consideration that miRNAs bind to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) ‘seed' sequences of mRNA, leading to changes in their expression levels, we examined the potential mRNA targets of tested miRNAs.26 Using the pMiRTarget-luciferase reporter assay, we further found that several mRNA 3′-UTRs acted as direct targets of tested miRNAs, including those for DICER1 (miR-519a, miR-374a), DDIT1 (miR-374a) and DDIT4 (miR-181a), YES1 (miR-519a), homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 (HIPK2) (miR-181a), ATM (miR-181a, miR-374a), BCL2 (miR-630), BCL2L2 (miR-630), and YAP1 (miR-630). Corresponding miRNA mimics were shown to repress the luciferase reporter activities driven by the specific pMiR-Target plasmids (Supplementary Figures S8–S16). Moreover, CIS exposure led to an increase in the luciferase reporter activities of the pMiR-Target plasmids modulated by miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a. Meanwhile, there was a decrease in the luciferase activities of the pMiR-Target plasmids, which were modulated by miR-630 (Supplementary Figures S8–S16). Using qPCR assay, we further observed that the CIS exposure and inhibitors for miR-181a, miR-519a, miR-374a increased the DDIT4, YES1 and DDIT1 mRNA levels, whereas CIS treatment and the miR-630 mimic decreased BCL2 mRNA levels (Supplementary Figure S17).

CIS induces p53-dependent and caspase-dependent apoptosis through deregulation of p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs

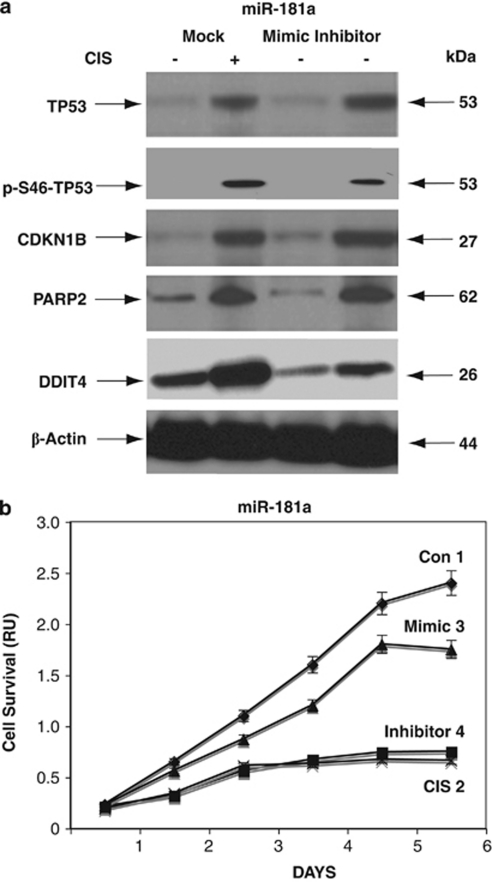

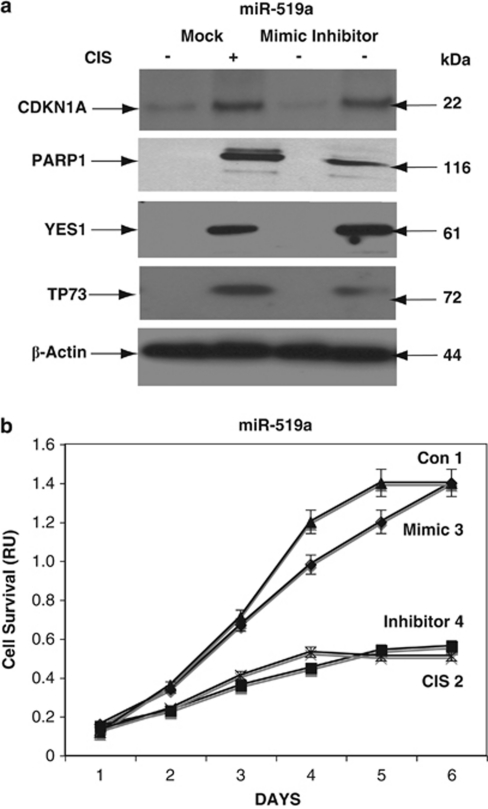

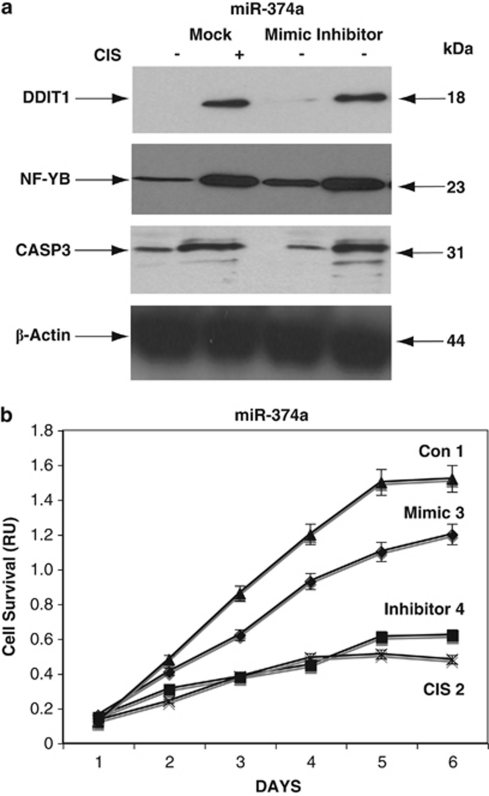

To further examine the miRNA-dependent mRNA targets that were potentially affected by CIS, we tested the expression of these targets at the protein level. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock), mimic, or inhibitor for miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a for 24 h and exposed to Con (−) and 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for an additional 24 h and examined by immunoblotting. We found that the CIS exposure induced the accumulation of total TP53, S46-p-TP53, PARP2, CDKN1B, and DDIT4 (Figure 6a), CDKN1A, PARP1, YES1, and TP73 (Figure 7a), and DDIT1 and 4, YES1, and CASP3 (Figure 8a). In contrast to miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a inhibitors and the mock control, mimics for miR-181a, miR-519a, and miR-374a decreased the levels of these cell cycle arrest and pro-apoptotic markers in wild-type ΔNp63α cells (Figures 6a, 7a and 8a).

Figure 6.

CIS-induced modulation of miR-181a expression leads to the activation of cell cycle arrest and apoptotic markers. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock), mimic, or inhibitor for miR-181a for 24 h and then exposed to Con (−) or 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for an additional 24 h. (a) Protein levels of TP53, p-TP53, PARP2, CDKN1B, and DDIT4 were examined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies and loading levels were tested with an anti-β-actin antibody. (b) CIS-induced modulation of cell survival by miR-181a. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock, curves 1 and 2), miR-181a mimic (curve 3), or miR-181a inhibitor (curve 4) and then exposed to Con (curves 1, 3, and 4) or 10 μg/ml CIS (curve 2) for 0–120 h. Cell survival was assessed at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h by MTT cell proliferation assay. Absorbance readings were taken using a SpectraMax M2e Microplate fluorescence reader (Molecular Devices) at 570 and 650 nm wavelengths. All samples were run in triplicate. Experiments were performed in triplicate with ±S.D. as indicated (<0.05)

Figure 7.

CIS-induced modulation of miR-519a expression leads to the activation of cell cycle arrest and apoptotic markers. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock), mimic, or inhibitor for miR-519a for 24 h and then exposed to Con (−) or 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for an additional 24 h. (a) Protein levels of PARP1, CDKN1A, YES1, and TP73 were examined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies, and loading levels were tested with an anti-β-actin antibody. (b) CIS-induced modulation of cell survival by miR-519a. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock, curves 1 and 2), miR-519a mimic (curve 3), or miR-519a inhibitor (curve 4) and then exposed to Con (curves 1, 3, and 4) or 10 μg/ml CIS (curve 2) for 0–120 h. Cell survival was assessed at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h by MTT assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate with ±S.D. as indicated (<0.05)

Figure 8.

CIS-induced modulation of miR-374a expression leads to the activation of apoptotic markers. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock), mimic, or inhibitor for miR-374a for 24 h and then exposed to Con (−) or 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for an additional 24 h. (a) Protein levels of DDIT4, CASP3, and NF-YB were examined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies and loading levels were tested with an anti-β-actin antibody. (b) CIS-induced modulation of cell survival by miR-374a. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock, curves 1 and 2), miR-374a mimic (curve 3), or miR-374a inhibitor (curve 4) and then exposed to Con (curves 1, 3, and 4), or 10 μg/ml CIS (curve 2) for 0–120 h. Cell survival was assessed at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h by MTT assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate with ±S.D. as indicated (<0.05)

We further assessed the ability of specific miRNAs to modulate cell survival. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells transfected with mimic or inhibitors for specific miRNAs were exclusively exposed to Con. Cells transfected with the mock vector were incubated with Con and 10 μg/ml CIS. We found that CIS (Figures 6b, 7 and 8b, curve 2) and inhibitors for miR-181a, miR-519a and miR-374a (Figures 6b, 7b and 8b, curve 4) dramatically decreased cell survival, whereas mimics for miR-181a (Figure 6b, curve 3), miR-519a (Figure 7b, curve 3), and miR-374a (Figure 8b, curve 3) minimally decreased the survival of cells compared with incubation of cells in the Con (Figures 6b, 7b and 8b, curve 1) or CIS (Figures 6b, 7b and 8b, curve 2). This finding suggests that the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs are critically involved in the CIS-induced apoptotic process.

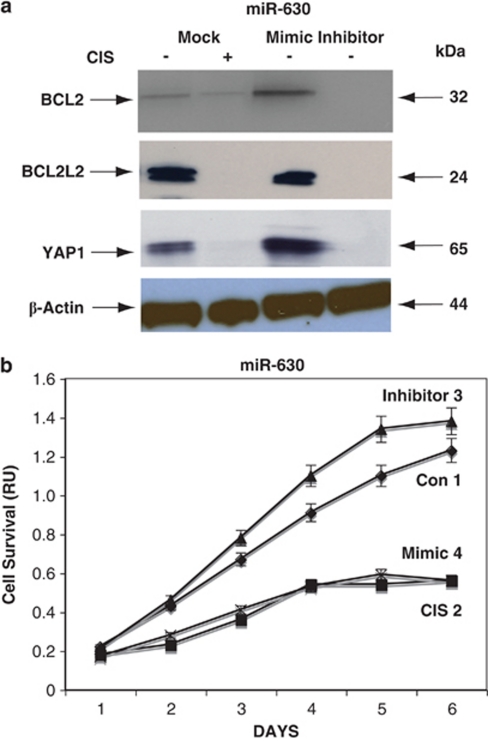

CIS induces apoptosis through deregulation of p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs targeting BCL2 and BCL2L2

Of the p-ΔNp63α-dependent miRNAs upregulated in HNSCC cells upon CIS exposure, miR-630 stood out. After inspection of the mRNA targets for miR-630 on http://www.microrna.org and monitoring of their miRNA-binding activities (Supplementary Figures S14, S15 and S16), we focused on critical apoptotic activators (YAP1) and apoptotic inhibitors (BCL2 and BCL2L2). Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock), mimic, or inhibitor for miR-630 for 24 h and exposed to Con (−) and 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for an additional 24 h. We found that CIS and the miR-630 mimic decreased the expression of YAP1, BCL2, and BCL2L2, whereas the miR-630 inhibitor increased the protein levels of these apoptotic regulators (Figure 9a). For cell survival study, cells transfected with mimic or inhibitors for specific miRNAs were exposed to Con, while cells transfected with the mock vector were incubated with Con and 10 μg/ml CIS. We then found that CIS (Figure 9b, curve 2) and miR-630 mimic (Figure 9b, curve 4) dramatically decreased cell survival, whereas the miR-630 inhibitor (Figure 9b, curve 3) increased cell survival compared with the Con (Figure 9b, curve 1).

Figure 9.

CIS-induced activation of miR-630 expression leads to the modulation of apoptotic markers. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock), mimic, or inhibitor for miR-630 for 24 h and then exposed to Con (−) or 10 μg/ml CIS (+) for an additional 24 h. (a) Protein levels of BCL2, BCL2L2, and YAP1 were examined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies, and loading levels were tested with an anti-β-actin antibody. (b) CIS-induced modulation of cell survival by miR-630. Wild-type ΔNp63α cells were transfected with control (mock, curves 1 and 2), miR-630 inhibitor (curve 3),37 or miR-630 mimic (curve 4) and then exposed to Con (curve 1, 3, and 4) or 10 μg/ml CIS (curve 2) for 0–120 h. Cell survival was assessed at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h by MTT assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate with ±S.D. as indicated (<0.05)

Discussion

Given that the miRNA expression is maintained by RNA polymerase II and III transcription machinery, it is likely that the potential regulatory role of p-ΔNp63α is intimately intertwined with the role of other transcription factors, co-activators/co-repressors, histone acetyl-transferases/deacetylases, histone and DNA methyltransferases, and other chromatin-accessory proteins.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Moreover, because miRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts, a complex RNA-processing machinery26, 33 may also be involved in the regulation of miRNA expression and may be potentially affected by CIS exposure. However, this study was exclusively focused on the CIS/p-ΔNp63α functional relationship regarding the miRNA expression in HNSCC cells.

In the current study, we attempted to understand the role for p-ΔNp63α in the regulation of the miRNA signature of HNSCC cells exposed to CIS treatment. (1) Which miRNAs are affected by CIS exposure and (2) which miRNAs affected by CIS exposure are potentially regulated by the p-ΔNp63α transcription factor? We found that the exposure of wild-type ΔNp63α cells to CIS induced the expression of DICER1, which is a critical component of the RNA-induced silencing microprocessor complex (RISC) implicated in miRNA maturation.15 Recently, Elsa Flores' research team elegantly showed that p63 coordinately regulates DICER1 and miR-130b transcription, while suppressing the tumor cell metastatic potential.24 We, however, showed that p-ΔNp63α induced DICER1 transcription in wild-type ΔNp63α cells upon CIS exposure. We found that p-ΔNp63α deregulated a number of miRNAs in wild-type ΔNp63α cells upon CIS exposure, ultimately changing the landscape of mRNA expression controlled by miRNAs. Among many miRNAs differentially regulated by p-ΔNp63α, a few (181a, 519a, and 374a) showed the highest degree of inhibition, whereas miR-630 showed the highest degree of activation. We further found that although p-ΔNp63α induces upregulation and downregulation of miRNA expression, the profound effect of DICER1 is seen in miRNA expression upregulated*** by CIS-mediated and p-ΔNp63α-dependent mechanism. This observation supports the cumulative effect of the DICER1 on the p-ΔNp63α-dependent upregulated miRNAs and antagonistic effect of DICER1 on the p-ΔNp63α-dependent downregulated miRNAs. We then showed that p-ΔNp63α directly affects miRNA transcription by binding to specific miRNA promoters and regulating miRNA expression levels accordingly. Finally, we showed that the downstream targets affected by the p-ΔNp63α-dependent modulation of miRNA expression in wild-type ΔNp63α cells include critical regulators of TP53-dependent and TP53-independent apoptotic genes.2, 34, 35, 36

Our data strongly suggest that following CIS exposure, the p-ΔNp63α transcription factor is likely to play a decisive role in the regulation of certain miRNAs leading to the activation of pro-apoptotic pathways in HNSCC cells. There are two potential mechanisms by which p-ΔNp63α can regulate miRNA expression: through the DICER1 transcriptional upregulation and subsequent maturation of miRNAs, and/or through direct transcriptional regulation of miRNA gene promoters via formation of protein complexes with other transcriptional and chromatin-associated factors. On one hand, the expression of mRNA target genes is maintained through a coupling mechanism that includes transcription factors and miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional machinery.14, 32, 37 On the other hand, the miRNA expression levels in cells under various experimental conditions are controlled by dual regulation through transcription factors and by post-transcriptional regulation by RISC components, as suggested by the data from this study. It is likely that both mechanisms play specific roles in the CIS-induced microRNAome deregulation in HNSCC cells. Certain miRNAs whose expression is altered after exposure of wild-type ΔNp63α cells to CIS can induce pro-apoptotic signaling pathways (e.g. ATM-HIPK2-TP53-HMGA1, SIRT1-PARP, caspase cascade, TP73-YES1-YAP1, DDIT1 and 4, and BCL2, etc.), while activating cell cycle regulators (CDKN1A, CDKN1B, CDKN2C, and CDKN3).

Numerous reports have shown that TP53 protein accumulates rapidly upon DNA damage through a post-translational phosphorylation mechanism, leading to its activation as a transcriptional factor and subsequently to programmed cell death.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 CIS has been shown to increase the expression and activity of HIPK2, whose activation subsequently leads to CIS-dependent apoptosis through TP53 phosphorylation at Serine-46 (S46-p-TP53), which in turn activates certain apoptotic gene promoters and modulates the TP53-dependent protein–protein interactions.34, 35, 36 Forced HIPK2 expression in U2OS cells increased the apoptotic response to CIS and potentiated the tumor suppressive activity of TP53 and TP73 through their protein–protein interactions.34, 35, 36 Moreover, HMGA1 overexpression promoted HIPK2 import from the nucleus to the cytoplasm with the subsequent inhibition of TP53 apoptotic function.36 A recent report by other investigators also showed that specific miRNAs regulate TP53, PARP, and CDKNA1 upon DNA damage through deregulation of miR-181a and miR-630 in non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells upon CIS exposure.38

We found here that mRNAs for many proteins involved in cell cycle arrest and cell death are direct targets for miRNA whose expression is altered by the CIS/p-ΔNp63α-dependent regulation in HNSCC cells (Supplementary Figures S8–S17). We showed that p-ΔNp63α is implicated in the tight regulation of the miRNA landscape, which in turn modulates downstream mRNA targets that contribute to critical cellular decisions about cell survival or cell death. Our study establishes a new functional link between p-ΔNp63α and the deregulated miRNAome during CIS-induced tumor cell death, suggesting novel mechanisms (transcriptional regulation and DICER1-dependent pri-miRNA maturation) through which p-ΔNp63α could potentially act as a regulator of death or survival for HNSCC cells during chemotherapy.

Many fundamental questions remain regarding the transcriptional function of p53 family members in general and particularly in p-ΔNp63α. How does p63 activate or repress gene transcription, specifically the miRNA gene transcription? What molecular regulators (e.g. other transcription factors, co-activators/co-repressors, histone acetyltransferases/deacetylases, histone and DNA methyltransferases) determine the binding of p-ΔNp63α to specific gene promoters and its transactivational activity towards the RNA polymerase II initiation complex and define the outcome leading to gene activation versus gene repression? Although p-ΔNp63α is supposed to control miRNA expression through the CCAAT box in both positive (upregulated miRNAs) and negative (downregulated miRNAs) manners, we can only speculate why p-ΔNp63α activated some miRNA promoters and repressed others. Potential interactions of p-ΔNp63α with other transcription factors (e.g. TP53, NF-Y, E2F, STAT, C/EBPβ, Oct-1, and Sox-5) and chromatin modifiers (e.g. p300, PCAF, HDAC, and DNMT) might provide the necessary support (Supplementary Figures S1–S6).27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Recent report showed that HDAC1/2 are present at the promoter regions of ΔNp63-repressed targets in keratinocytes, indicating a direct requirement for HDAC1/2 in ΔNp63-mediated repression.39

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

TheHNSCC cell line JHU-029 (expressing wild-type p53 and p63) was isolated from primary tissue at the Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.21, 22 The Flp-In approach used to generate the JHU-029 clones allowed us to introduce the S385G mutation into the genomic DNA.21, 22 Accordingly, these cells exclusively expressed the ΔNp63α-S385G protein, which was confirmed by sequencing the individual mRNA-amplified clones obtained from wild-type and mutated cells. These stable clones were designated as wild-type ΔNp63α cells and ΔNp63α-S385G cells. Cells were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 and 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated with Con or 10 μg/ml CIS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for the indicated time periods. Cells were lysed with buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% Brij-50, 1 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 2 × complete protease inhibitor cocktail), sonicated five times for 10-s intervals, and centrifuged for 30 min at 15 000 × g. Supernatants were analyzed by immunoblotting.21, 22 Immunoblots were scanned using a PhosphorImager and quantified using Image Quant software version 3.3 (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and the levels of tested proteins were normalized against β-actin levels. Values were expressed as fold change compared with a control sample (defined as 1).

Antibodies

We used a mouse anti-YAP1 polyclonal antibody (ab22144), a mouse anti-p73α/β monoclonal antibody (clone ER-15, ab17230), a mouse anti-YES1 monoclonal antibody (ab61206), a mouse anti-BCL2 polyclonal antibody (clone 124, ab694), a rabbit monoclonal anti-CDKN1B antibody (Ab32034), a rat monoclonal anti-BCL2L2 antibody (clone 16H12, ab54313), and a rabbit polyclonal anti-NF-YB antibody (ab6559), which were all purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). A rabbit anti-DICER1 polyclonal antibody (NPB1-06521) was purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA), whereas a rabbit anti-CASP3 polyclonal antibody (H00000836-D01P) and a mouse anti-CDKN1A monoclonal (H000001026-MO2) were obtained from Abnova Corporation (Taipei, Taiwan). We used a rabbit anti-PARP1 monoclonal antibody (LS-C38096) and a rabbit anti-PARP2 polyclonal antibody (LS-C40697) obtained from Lifespan Biosciences (Seattle, WA, USA). A rabbit anti-human TP53-S46 (p-Ser46) polyclonal antibody (sc-101764) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). A rabbit anti-human polyclonal GADD45A (DDIT1) antibody (#3518) and a rabbit anti-human DDIT4 polyclonal antibody (#2516) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). We also used a monoclonal antibody against human β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), a monoclonal antibody anti-human wild-type TP53 antibody (clone DO-1, #554293, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), and a mouse monoclonal antibody against the FLAG epitope (Clone 29E4.G7, #200-301-B13, Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against ΔNp63 (anti-p40, PC373, residues 5–17 epitope) was purchased from EMD/Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). A custom rabbit polyclonal antibody against a phosphorylated peptide encompassing the ΔNp63α protein sequence (ATM motif, NKLPSV-pS-QLINPQQ, residues 379–392) was prepared and purified against the phosphorylated peptide versus non-phosphorylated peptide.21

Reverse transcription-PCR

The First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for reverse transcription. PCR was performed with recombinant Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) as follows: 24–30 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s, as described elsewhere.22 As an internal loading control, we amplified a region from GAPDH mRNA using the following primers: sense primer, 5′-CTACATGGTTTACATGT-3′ (121) and antisense primer, 5′-TGCCCTCAACGACCACT-3′ (920). These primers give rise to an 800-bp PCR product. For the DICER1 amplification, we used the following primers: sense primer, 5′-GGTCTTAGACAGGTATACTTCT-3′ (961) and antisense primer, 5′-TGCCTCACTTGACCTTG-3′ (1336). These primers produce a 375-bp PCR product. PCR products were resolved by 2% agarose electrophoresis. For each set of primers the number of amplification cycles was predetermined to achieve the exponential phase of the PCR reaction. PCR amplification results were analyzed digitally by Kodak 1D 3.5 software (Kodak Scientific Imaging, Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). The net intensity of PCR bands was measured and normalized against the net intensity of GAPDH bands.22 The same primers were used for qPCR amplification of DICER1 and GAPDH mRNA transcripts.

ChIP

First, 5 × 106 cell equivalents of chromatin (2–2.5kb in size) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with 10 μg of anti-p-ΔNp63 antibody or anti-ΔNp63 antibody, as essentially described elsewhere.22, 23 After reversal of formaldehyde crosslinking, RNase A and proteinase K treatments, IP-enriched DNAs were used for PCR amplification. PCR consisted of 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s using Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The relative enrichment (Bound) measurements for the indicated regions of tested promoters were shown as percentage of Input (Supplementary Figure S7). PCR primers used for amplification of the DICER1 promoter and miRNA promoters are listed in Supplementary Figures S1–S6.

Luciferase reporter assay

We used the pGL3-DICER1 (S109038) promoter-luciferase reporter plasmid (encompassing −870 to +50 bp of the DICER promoter) and 3′-UTR luciferase reporter constructs for DICER1 (S214311), DDIT1 (S204414), DDIT4 (S206522), and YES1 (S211786) obtained from SwitchGear Genomics (Menla Park, CA, USA), whereas 3′-UTR luciferase reporter plasmids for HIPK1 (SC221730) and BCL2 (SC222289) were purchased from Origene Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA). A total of 5 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate were transfected with 100 ng of the pGL3 luciferase reporter constructs plus 1 ng of the Renilla luciferase plasmid pRL-SV40 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using FuGENE 6 (Roche-Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), as previously described.22, 23 Cells were also transfected with 100 ng of the mimics or inhibitors of tested miRNAs. At 24 h, cells were also treated with 10 μg/ml CIS or Con and then, after an additional 24 h, luciferase assays were performed using the Dual luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) for the promoter plasmid, and the Luc-Pair miR Luciferase Assay kit (Gene Copoeia, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) for the 3′-UTR plasmids. For each experiment, the wells were transfected in triplicate and each well was assayed in triplicate. To 50 μl of Firefly luciferase substrate was added 10 μl of cleared cell lysate, and light units were measured in a luminometer. Renilla luciferase activity was measured in the same tube after addition of 50 μl of Stop and Glo reagent. The values for Firefly luciferase activity were normalized against the Renilla luciferase activity values for each transfected well.

miRNA microarray analysis

miRNA microarray chips for 874 human miRNAs were synthesized by Combimatrix, and miRNA array analysis was performed as described elsewhere.13 Probes containing two mismatches were included for all miRNAs. Arrays were prehybridized at 37°C for 1 h in 3 × SSC, 0.1% SDS, and 0.2% bovine serum albumin. Ten micrograms of total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen), labeled with Cy3 and hybridized to arrays at 37°C overnight in 400 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 0.8% BSA, 5% SDS, and 12% formamide. Arrays were washed once at room temperature in 2 × SSC, 0.25% SDS, three times at room temperature in 1.6 × SSC, and twice in ice-cold 0.8 × SSC. Hybridized arrays were then scanned using a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Axon, Inc., Darien, CT, USA), and signal intensities were extracted using the Combimatrix Microarray Imager software (Combimatrix Diagnostics, Irvine, CA, USA). The background value was determined by calculating the median signal from the mismatch probes, and this value was subtracted from all perfect match probes. Signals that were less than 1.5 times stronger than the background were removed, and data sets were median centered prior to calculation of fold-change values. No significant differences in miRNA levels between wild-type ΔNp63α cells and ΔNp63α -S385G cells treated with Con were found, with these levels being significantly lower than in cells exposed to CIS.

Validation of miRNA array data by qPCR

To validate the differential expression of miRNAs, we isolated total small RNAs using a miRVana miRNA isolation kit (#AM1560, Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We then used the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (#4374966, Applied Biosystems) to produce single-stranded cDNA probes. Next, we performed a qPCR using the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay Kit TaqMan U47 (#4380911) and TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, 1-Pack (#4369016), both obtained from Applied Biosystems.19 For precursor pri-miRNAs, we used the following individual kits: pri-hsa-miR-181a (Hs03302966_pri), pri-hsa-miR-517a (Hs03302632_pri), pri-hsa-miR-374a (Hs03304235_pri), pri-hsa-miR-630 (Hs03304713_pri), and pri-hsa-miR-885-3p (Hs03305150_pri). For mature miRNAs, we also used the following: hsa-miR-181a (#000480), hsa-miR-519a (#002415), hsa-miR-374a (#000563), hsa-miR-630 (#001563), hsa-miR-194 (#000493), and hsa-miR-885-3p (#002372). The reaction conditions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min with a sample volume of 20 μl. The independent biological experiments were performed twice. Each RNA sample was amplified in triplicate, and obtained values used for statistical analysis. Expression was normalized to the U47 expression (gene ID 26802), and expression levels were determined as the average Ct of the U47 control. This averaged value was then used to normalize the sample's Ct. The average miRNA expression was determined using the Mann–Whitney U-test.19

miRNA mimics and inhibitors and transfection

Individual miRNA mimics (precursors) (hsa-miR-181a (PM10381), hsa-miR-519a (PM12922), hsa-miR-374a (PM12702), and hsa-miR-630 (PM11552)), and inhibitors: (hsa-miR-181a (AM10381), hsa-miR-519a (AM12922), hsa-miR-374a (AM12702), and hsa-miR-630 (AM11552)) were purchased from Ambion/Applied Biosystems (Austin, TX, USA). Cells were transfected for 24 h in a six-well plate with 100 pmol of the mimic, inhibitor or control in 500 μl serum-free medium with 5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Each experiment was performed independently at least three times and in triplicate. To test the effect of DICER1 on miRNA expression in HNSCC cells after CIS exposure, we used scrambled siRNA (5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) and DICER1 siRNA (5′-AAGGCTTACCTTCTCCAGGCT-3′) obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA), as previously described.40

To maximally inhibit DICER1 expression and keep the cells at optimal density, ΔNp63α cells were transfected with two rounds of DICER1 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (each at 100 nM). Cells were split 48 h after the first round of DICER1 siRNAs transfection and were transfected again with the same siRNAs for another 24 h along with exposure to Con or 10 μg/ml CIS. After the last treatment, cells were collected for PCR or immunoblotting with antibodies to DICER1 or β-actin.

Cell survival assay

Cells were plated at 20–30% confluency in each well of a six-well plate. Growth was assayed at 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h by MTT cell proliferation assay (American Tissue Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA). Absorbance readings were taken using a SpectraMax M2e Microplate fluorescence reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 570 and 650 nm wavelengths. All samples were run in triplicate.21, 22

FACS cell cycle analysis

Cells were harvested, washed in PBS, and fixed in MetOH:acetic acid solution (4 : 1) for 60 min at +4 °C. Cells were then incubated in 500 μl of staining solution (50 μg/μl of propidium iodide, 50 μg/μl of RNase, 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1 × PBS for 1 h at +4 °C and analyzed by flow cytometry performed on the FACS Calibur instrument (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired Student's t-test. P-values of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant 5R01DE13561 (DS, ER and BT).

Glossary

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- ATM

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- DDIT

DNA-damage-inducible transcript

- CIS

cisplatin

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- BCL

B-cell CLL/lymphoma

- NF

nuclear factor

- CDKN

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor

- HIPK

homeodomain interacting protein kinase

- YES

Yamaguchi sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- YAP

YES-associated protein

- HMG

high-mobility group

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing microprocessor complex

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- p

phospho

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by M Oren

Supplementary Material

References

- Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangen R, Ratovitski E, Sidransky D. Np63α levels correlate with clinical tumor response to cisplatin. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1313–1315. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz L, Unsal-Kaccmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banin S, Moyal L, Shieh S, Taya Y, Anderson CW, Chessa L, et al. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science. 1998;281:1677–1679. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tsai K, Crowley D, Sengupta S, Yang A, McKeon F, et al. P63 and p73 are required for p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2002;416:560–564. doi: 10.1038/416560a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocco J, Leong C, Kuperwasser N, DeYoung M, Ellisen L. P63 mediates survival in squamous cell carcinoma by suppression of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walensky L. BCL-2 in the crosshairs: tipping the balance of life and death. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1339–1350. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Caspase function in programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:32–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh W, Nam S, Sabapathy K. An essential role for p73 in regulating mitotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:787–800. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. The Yes-associated protein 1 stabilizes p73 by preventing Itch-mediated ubiquitination of p73. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:743–751. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Jausdal V, Haun R, Seth R, Shah S, Kaushal G. Transcriptional activation of caspase-6 and -7 genes by cisplatin-induced p53 and its functional significance in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:530–544. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Kim J, Han K, Yeom S, Lee S, Baek SH, et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Rajewsky N. The evolution of gene regulation by transcription factors and micro-RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:93–103. doi: 10.1038/nrg1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt A, MacRae I. The RNA-induced silencing complex: a versatile gene-silencing machine. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17897–17901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volinia S, Calin G, Liu C, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Jiang W, Smith I, Poeta L, Begum S, Glazer C, et al. MicroRNA alterations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2791–2797. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melino G, Knight R. MicroRNAs meet cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:189–190. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T, Wentzel E, Kent O, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena A, Shalom-Feuerstein R, Rivetti di Val Cervo P, Aberdam D, Knight RA, Melino G, et al. miR-203 represses ‘stemness' by repressing DeltaNp63. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1187–1195. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Sen T, Nagpal J, Kim M, Upadhyay S, Trink B, et al. ATM kinase is a master switch for the ΔNp63α protein phosphorylation/degradation in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells upon DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2846–2855. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Chuang A, Romano R, Wu G, Sinha S, Trink B, et al. Phospho-ΔNp63αNF-Y protein complex transcriptionally regulates DDIT3 expression in squamous cell carcinoma cells upon cisplatin exposure. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:332–342. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.2.10432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada M, Yamashita K, Park H, Fomenkov A, Kim M, Wu G, et al. Differential recognition of response elements determines target gene specificity for p53 and p63. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6077–6089. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6077-6089.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Chakravarti D, Cho M, Liu L, Gi Y, Lin YL, et al. TAp63 suppresses metastasis through coordinate regulation of Dicer and miRNAs. Nature. 2010;467:986–990. doi: 10.1038/nature09459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Calin G, Volinia S, Croce C. MicroRNA expression profiling using microarrays. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:563–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai E. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′-UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet. 2002;30:363–364. doi: 10.1038/ng865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynoird N, Schwartz B, Delvecchio M, Sadoul K, Meyers D, Mukherjee C, et al. Oncogenesis by sequestration of CBP/p300 in transcriptionally inactive hyperacetylated chromatin domains. EMBO J. 2010;29:2943–2952. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strano S, Monti O, Pediconi N, Baccarini A, Fontemaggi G, Lapi E, et al. The transcriptional coactivator Yes-associated protein drives p73 gene-target specificity in response to DNA Damage. Mol Cell. 2005;18:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Aggarwal A, Glass C, Rose D, Rosenfeld M. A corepressor/coactivator exchange complex required for transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors and other regulated transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:511–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pediconi N, Guerrieri F, Vossio S, Bruno T, Belloni L, Schinzari V, et al. SIRT1-dependent regulation of the PCAF-E2F1-p73 apoptotic pathway in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1989–1998. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00552-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Orphanides G, Sun X, Yang X, Ogryzko V, Lees E, et al. A human RNA polymerase II complex containing factors that modify chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2153–2163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeser M, Iggo R. Promoter-specific p53-dependent histone acetylation following DNA damage. Oncogene. 2004;23:4007–4013. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Hagedorn C, Cullen B. Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:1957–1966. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong C, Vidnovic N, DeYoung M, Sgroi D, Ellisen L. The p63/p73 network mediates chemosensitivity to cisplatin in a biologically defined subset of primary breast cancers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1370–1380. doi: 10.1172/JCI30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Orazi G, Cecchinelli B, Bruno T, Manni I, Higashimoto Y, Saito S, et al. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 phosphorylates p53 at Ser 46 and mediates apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:11–19. doi: 10.1038/ncb714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierantoni G, Rinaldo C, Mottolese M, Di Benedetto A, Esposito F, Soddu S, et al. High-mobility group A1 inhibits p53 by cytoplasmic relocalization of its proapoptotic activator HIPK2. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:693–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI29852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Shalgi R, Brosh R, Oren M, Pilpel Y, Rotter V. Coupling transcriptional and post-transcriptional miRNA regulation in the control of cell fate. Aging. 2009;1:762–770. doi: 10.18632/aging.100085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Vitale I, Kepp O, Senovilla L, Criollo A, et al. MiR-181a and miR-630 regulate cisplatin-induced cancer cell death. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1793–1803. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf M, Terrell A, Trivedi S, Sinha S, Epstein J, Olson EN, et al. Hdac1 and Hdac2 act redundantly to control p63 and p53 functions in epidermal progenitor cells. Dev Cell. 2010;19:807–818. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K, Ren H, Cao J, Zeng G, Xie J, Chen M, et al. Decreased Dicer expression elicits DNA damage and up-regulation of MICA and MICB. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:233–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.