Abstract

Intergenic regions often contain regulatory elements that control the expression of flanking genes. Using a deep-sequencing approach, we identified numerous new transcription start sites in Escherichia coli, yielding a new thermosensing regulatory RNA and seven genes previously unknown to be under the control of the global regulator CRP.

TEXT

The recognition sequences of several sigma factors, which direct RNA polymerase to the appropriate sites of transcription, have been experimentally characterized in Escherichia coli, opening the possibility to predict their occurrence based solely on sequence features (10, 15). However, computational methods will falsely identify transcription start sites (TSSs) due to the abundance of promoter-like motifs throughout the genome and will also fail to recognize actual promoters due to low signal strength (14). Such difficulties necessitate the application of experimental methods to identify and validate TSSs throughout the genome. Traditionally, TSSs have been identified by gene-by-gene approaches, but the advent of high-throughput methods has greatly accelerated their identification (13, 14, 19). Currently, over 2,000 TSSs of the ≈3,400 transcriptional units in E. coli that have been catalogued have been experimentally validated (4), suggesting that many more are yet to be discovered in this genome.

cis-Acting regulatory RNAs control the expression of many bacterial genes. These RNAs usually occur in the 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) and regulate gene expression by attaining alternate structures in response to specific environmental cues (17). In addition, gene regulation can be modulated by transcription factors. In E. coli, the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) is a global transcription factor that regulates numerous genes by binding to a 22-bp DNA sequence (3). Here, we investigated the E. coli transcriptome and report the identification of (i) 39 new TSSs, (ii) a novel temperature-sensing RNA, and (iii) additional genes that are part of the CRP regulon.

To interrogate the transcriptome, we grew E. coli K-12 MG1655 in N-minimal medium to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.4). Total RNA was isolated and treated with DNase, and rRNAs were removed with a MICROBExpress kit (ABI). Sequencing libraries were constructed and sequenced using an Illumina genome analyzer. Sequencing reads (36 nucleotides [nt]) were plotted onto the E. coli genome using MAQ (11). Of the 31.2 and 30.4 million high-quality reads obtained from our two samples, 7% (2.2 and 2.1 million reads, respectively) mapped to the 3,683 intergenic regions (IGRs), providing ≈145-fold coverage. Because this methodology does not divulge the DNA strand on which transcripts are carried, we considered only the 673 IGRs that are flanked by divergently transcribed genes in E. coli (18).

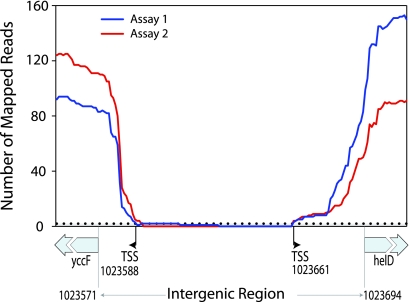

To identify new TSSs, we focused on 129 divergent IGRs that are ≥25 nt and do not contain any predicted or experimentally verified TSSs (4). Of these, 32 lacked mapped reads in the center of the IGR, which allows differentiation of opposing transcriptional units associated with the flanking genes (Fig. 1). From these 32 IGRs, we removed 25 of the 64 (2 × 32) possible flanking genes due to low or uneven coverage, leaving 39 genes whose TSSs have not previously been observed but were readily identifiable by our methods (Table 1). To pinpoint TSSs, we considered only those sites that had at least two sequencing reads in both assays (Fig. 1). (This strategy was tested on 10 known TSSs, and our predictions fell within 10 nt of experimentally detected TSSs.) The newly identified leader sequences ranged from 9 to 349 nt in length, most being between 20 to 40 nt (Table 1), as previously shown (14).

Fig. 1.

Transcription start sites mapped with RNA-Seq. Reads from two sequencing assays mapped to the intergenic region and first 20 bases of flanking genes (yccF and helD) are shown. Locations of putative TSSs are marked where the number of reads on both samples crosses below 2 (dotted line). Numbering is according to the E. coli MG1655 genome (GenBank accession number NC_000913.2).

Table 1.

Newly identified transcription start sites

| TSSa | Downstream gene | Length of leader (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| 118663 | nadC | 17 |

| 118703 | ampD | 29 |

| 146745 | panD | 50 |

| 214187 | yaeP | 61 |

| 214280 | yaeQ | 10 |

| 398678 | yaiZ | 138 |

| 507415 | ybaQ | 26 |

| 515047 | qmcA | 49 |

| 515127 | ybbL | 15 |

| 852321 | mntR | 84 |

| 855009 | ybiS | 41 |

| 855170 | ybiT | 15 |

| 1023588 | yccF | 16 |

| 1023661 | helD | 32 |

| 1168067 | ycfQ | 11 |

| 1168256 | bhsA | 39 |

| 1438855 | ydbK | 46 |

| 1439053 | ydbJ | 28 |

| 1493158 | ydcI | 62 |

| 1630747 | ydfK | 349 |

| 1667696 | ynfM | 26 |

| 1839456 | ynjF | 28 |

| 1875681 | yeaP | 57 |

| 2228417 | dusC | 9 |

| 2228531 | yohJ | 114 |

| 2263352 | yeiW | 34 |

| 2263439 | yeiP | 32 |

| 2583599 | narQ | 153 |

| 2588992 | ypfM | 103 |

| 2627275 | yfgG | 36 |

| 2967015 | rppH | 15 |

| 3180455 | zupT | 116 |

| 3296919 | yraR | 50 |

| 3387452 | aaeX | 92 |

| 3387518 | aaeR | 23 |

| 3542880 | bioH | 13 |

| 4273187 | yjcB | 122 |

| 4273441 | yjcC | 52 |

| 4276344 | yjcD | 157 |

Location of TSSs according to nucleotide positions in E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome sequence (GenBank accession number NC_000913.2).

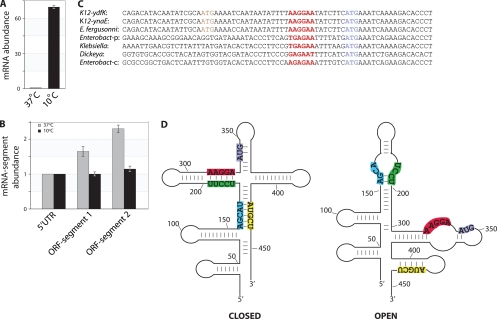

The longest observed 5′ leader sequence was for ydfK, a Qin prophage gene of unknown function that has been shown to be upregulated during cold shock treatment (16). Using quantitative PCR (qPCR), we quantified ydfK transcripts from E. coli grown at 37°C and from cells that were shifted from 37°C to 10°C for 1 h. We observed a 70-fold increase in transcript abundance in cold-shifted cells (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the abundances of regions within the transcript differed at the two temperatures. At 10°C, the transcript was stable across its length, whereas at 37°C, regions of the RNA were detected at different levels (Fig. 2B). Similar to these results, the transcripts from cspA, the major cold-shock protein gene in E. coli, have been shown to be more stable at 10°C due to a conformation change triggered by a long upstream UTR, which allows increased access to ribosomes and renders the mRNA resistant to nucleolytic degradation (5).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of ydfK mRNA. (A) Abundance of ydfK mRNA at 10°C relative to that at 37°C. (B) Abundances of ydfK mRNA segments at 37°C and 10°C (5′ UTR, 1630760–1630863; segment 1, 1631155–1631269; and segment 2, 1631205–1631306); numbering is according to E. coli MG1655 genome sequence). ORF, open reading frame. (C) The alignment of the following ydfK homologs is shown: ynaE gene in E. coli K-12; ydfK genes in Escherichia fergusonii; Enterobacter sp. 638 plasmid pENTE01 and another copy on the chromosome; Klebsiella pneumoniae 342; and Dickeya dadantii Ech586. Aligned start codons are shown in purple, the putative ribosome binding sites in red, and wrongly annotated start codons in brown. (D) Predicted alternate secondary structures of ydfK mRNA. Sequences from nt 1630750 to 1631250 are depicted. The ribosome binding site is shown in red, anti-RBS in green, anti-anti-RBS in blue, and the sequence that can bind to anti-anti-RBS in yellow. The start codon is shown in purple. In the “closed” structure, RBS is bound by anti-RBS, whereas in the “open” structure, part of anti-RBS pairs with anti-anti-RBS and is buried within a long hairpin, making the RBS and start codon accessible to ribosomes on single-stranded regions.

We first noted that the length of the IGR containing the long 5′ UTR of ydfK is conserved in other enteric bacteria, suggesting the presence of a functional region. Moreover, this comparison allowed us to correctly annotate the translation start site of the ydfK gene in E. coli (Fig. 2C). We then used RNAz (7) to identify a conserved structural RNA within ydfK mRNA at region −280 to +120 (with respect to the translation start site). Due to the rapid rate at which thermosensing RNAs evolve (2), we were able to detect homologs of this structural RNA only in very close relatives of E. coli K-12 (i.e., other sequenced E. coli strains and E. fergusonii). When we analyzed the secondary structure of ydfK mRNA predicted by Mfold (21) at 37°C and at 10°C, it became evident that the regions surrounding the ribosome binding site (RBS) and the start codon could attain alternate structures (Fig. 2D). In the “closed” conformation, the RBS and the start codon are sequestered within hairpins, whereas in an alternate “open” structure, the RBS and the start codon are in single-stranded regions and are presumably more accessible to ribosomes. Other ligand-binding riboswitches have been shown to employ a similar mechanism of translational control (17).

Since the TSSs identified in this study were expressed under a single growth condition, it is likely that some are coregulated by the same transcription factor. To identify putative DNA binding sites for regulatory proteins, we used a motif-recognition program (BioProspector [12]) previously used successfully (13) to search the sequences 80-nt upstream to 15-nt downstream of the 39 TSSs. A motif sequence identified in seven IGRs was similar to the binding sequence of CRP (Table 2). To test whether CRP regulates these genes, we isolated RNA from a strain of E. coli K-12 with crp deleted (JW5702-4) and its isogenic parent strain (BW25113) (1) grown in N-minimal media supplemented with 0.4% fructose (6). The expression of each gene in the wild-type parent relative to that in the strain lacking crp was calculated using 16S rRNA as a control in qPCR experiments. The expression levels of six genes (nadC, yaeQ, ycfQ, yeiP, aaeX, and aaeR) were significantly higher in the wild-type strain, whereas yeiW expression was significantly reduced in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). These genes were not previously known to be under the control of CRP, and in line with earlier studies, more genes were observed to be upregulated rather than downregulated by CRP (8, 20). The CRP binding site in the ybiS-ybiT IGR had been previously shown to repress ybiS in vitro but not in vivo (20), as observed here. Not all CRP-bound sites control gene expression (9), and it has been proposed that CRP can act as a chromosome-compacting protein due to its ability to bend DNA (6). These genes represent new targets in the CRP global regulatory network, and because many of them are hypothetical genes, this information may serve as the initial step in elucidating their functions.

Table 2.

Putative CRP binding sites

| Flanking genesa | Locationb | Sequencec |

|---|---|---|

| nadC and ampD | 118698–118719 | ATATGTGGTGCTAATACCCGGT |

| yaeP and yaeQ | 214196–214217 | GAGTGTGGTATAGTCACCTTGC |

| ybiS and ybiT | 855062–855083 | AAATGTGATTTCGTACACATCT |

| ycfQ and bhsA | 1168209–1168230 | GTATGTGATCCAGATCACATCT |

| yeiW and yeiP | 2263384–2263405 | GCAAGTGGTATTCGCACTTTTG |

| aegA and narQ | 2583588–2583609 | ATGAGTGTTGTTATTACCCGAC |

| aaeX and aaeR | 3387505–3387526 | AAAAGTGATTTAGATCACATAA |

| Consensus | AAATGTGATCTAGATCACATTT |

Consensus CRP binding site (3) is also shown.

Genomic region encompassing the putative CRP binding site in the corresponding intergenic region. Numbering is according to nucleotide positions in E. coli K-12.

MG1655 genome sequence (GenBank accession number NC_000913.2). Nucleotides where the CRP homodimer makes contact are in bold.

Fig. 3.

Regulation of gene expression by CRP. Transcript abundance in wild-type E. coli relative to that in an isogenic strain with crp deleted (normalized to 1; dotted line). Data represent means (± standard deviations) of three experiments. Statistically significant differences from expression in the strain lacking crp are indicated by asterisks (**, P ≤ 0.005; *, P ≤ 0.05 [unpaired t test]).

Acknowledgments

We thank Eduardo Groisman and Kerry Hollands for helpful discussions and Sun-Yang Park for providing the 16S PCR primers. We are grateful to Kim Hammond for assistance with figures and to the Genetic Stock Center at Yale University for proving E. coli strains.

This research was supported in part by NIH grant GM74738 to H.O.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baba T., et al. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breaker R. R. 2010. RNA switches out in the cold. Mol. Cell 37:1–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ebright R. H., Ebright Y. W., Gunasekera A. 1989. Consensus DNA site for the Escherichia coli catabolite gene activator protein (CAP): CAP exhibits a 450-fold higher affinity for the consensus DNA site than for the E. coli lac DNA site. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:10295–10305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gama-Castro S., et al. 2008. RegulonDB (version 6.0): gene regulation model of Escherichia coli K-12 beyond transcription, active (experimental) annotated promoters and Textpresso navigation. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D120–D124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giuliodori A. M., et al. 2010. The cspA mRNA is a thermosensor that modulates translation of the cold-shock protein CspA. Mol. Cell 37:21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grainger D. C., Hurd D., Harrison M., Holdstock J., Busby S. J. 2005. Studies of the distribution of Escherichia coli cAMP-receptor protein and RNA polymerase along the E. coli chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:17693–17698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gruber A. R., Neuböck R., Hofacker I. L., Washietl S. 2007. The RNAz web server: prediction of thermodynamically stable and evolutionarily conserved RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W335–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harari O., Park S.-Y., Huang H., Groisman E. A., Zwir I. 2010. Defining the plasticity of transcription factor binding sites by deconstructing DNA consensus sequences: the PhoP-binding sites among gamma/enterobacteria. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6:e1000862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hollands K., Busby S. J., Lloyd G. S. 2007. New targets for the cyclic AMP receptor protein in the Escherichia coli K-12 genome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 274:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huerta A. M., Collado-Vides J. 2003. Sigma70 promoters in Escherichia coli: specific transcription in dense regions of overlapping promoter-like signals. J. Mol. Biol. 333:261–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li H., Ruan J., Durbin R. 2008. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 18:1851–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu X., Brutlag D. L., Liu J. S. 2001. BioProspector: discovering conserved DNA motifs in upstream regulatory regions of co-expressed genes. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2001:127–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGrath P. T., et al. 2007. High-throughput identification of transcription start sites, conserved promoter motifs and predicted regulons. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:584–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mendoza-Vargas A., et al. 2009. Genome-wide identification of transcription start sites, promoters and transcription factor binding sites in E. coli. PLoS One 4:e7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mulligan M. E., Hawley D. K., Entriken R., McClure W. R. 1984. Escherichia coli promoter sequences predict in vitro RNA polymerase selectivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:789–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Polissi A., et al. 2003. Changes in Escherichia coli transcriptome during acclimatization at low temperature. Res. Microbiol. 154:573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roth A., Breaker R. R. 2009. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:305–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rudd K. E. 2000. EcoGene: a genome sequence database for Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:60–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tjaden B., et al. 2002. Transcriptome analysis of Escherichia coli using high-density oligonucleotide probe arrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3732–3738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zheng D., Constantinidou C., Hobman J. L., Minchin S. D. 2004. Identification of the CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:5874–5893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zucker M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]