Abstract

p53 plays a critical role in tumor suppression. As a transcription factor, in response to stress signals, p53 regulates its target genes and initiates stress responses, including cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and/or senescence, to exert its function in tumor suppression. Emerging evidence has suggested that p53 is also an important but complex player in the regulation of aging and longevity in worms, flies, mice, and humans. Whereas p53 accelerates the aging process and shortens life span in some contexts, p53 can also extend life span in some other contexts. Thus, p53 appears to regulate aging and longevity in a context-dependent manner. Here, the authors review some recent advances in the study of the role of p53 in the regulation of aging and longevity in both invertebrate and vertebrate models. Furthermore, they discuss the potential mechanisms by which p53 regulates aging and longevity, including the p53 regulation of insulin/TOR signaling, stem/progenitor cells, and reactive oxygen species.

Keywords: p53, aging, longevity, TOR/insulin/IGF-1, stem cell, ROS

Introduction

As a key tumor suppressor, p53 plays a critical role in tumor prevention. In response to various stress signals, p53 selectively regulates a set of its target genes and initiates various stress responses, including cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and/or senescence, to exert its function in tumor suppression.1-4 p53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human tumors; p53 mutations occur in more than 50% of all tumors. Disruption of normal p53 function is often a prerequisite for the development and/or progression of tumors.5,6 p53 is conserved from invertebrates to vertebrates; orthologs of p53 have been identified in worms (Caenorhabditis elegans), flies (Drosophila), zebrafish and frogs, and so on.7-9 The existence of p53 in short-lived organisms that do not develop cancers in the adult, such as flies and worms, suggests that tumor suppression is not the only or original function for p53. Indeed, recent studies have shown that p53 and its family members, including p63 and p73, all play important roles in reproduction.10-13 Recent studies have also suggested that p53 plays a role as a longevity regulator. It has been well established that p53 has a profound impact on longevity in different organisms through its tumor-suppressive function. For example, whereas wild-type mice have a median life span of around 2 years and maximal life span of 3 years, respectively, p53-null mice succumb to tumors within several months, and heterozygous p53 mutant mice develop tumors over a period of a year or more.5,6 Li-Fraumeni syndrome patients who have germline p53 mutations display a 50% cancer incidence by age 30 years.14 Therefore, by preventing tumors early in life, p53 is an important longevity assurance gene. Interestingly, emerging evidence has suggested that p53 can regulate aging and longevity aside from its tumor-suppressive function. Here, we review recent advances in the study of the role of p53 in the regulation of aging and longevity.

p53 and Longevity in C. elegans

Cep-1 is a p53 ortholog in C. elegans. Recently, Arum et al.15 showed that RNA interference (RNAi) or genetic knockout of Cep-1 led to the increased life span in C. elegans. This life span extension effect by cep-1 knockdown or knockout is dependent on functional daf-16, a FOXO ortholog that plays an important role in regulating longevity. Furthermore, knockdown of cep-1 by RNAi did not further extend the life span in C. elegans that overexpresses geIn3, a Sir2 ortholog whose overexpression extends life span in C. elegans. These results indicate that decreased p53 activity promotes longevity in C. elegans, and furthermore, p53, Sir2, and FOXO act through similar pathways to regulate longevity in C. elegans.15 However, a study by Pinkston and colleagues16 suggested that p53 may play a different role in longevity in C. elegans. gld-1 is a female germline-specific tumor suppressor that is essential for oogenesis in C. elegans. gld-1 mutation causes germ cells in the early stages of oogenesis to reenter the mitotic cell cycle and overproliferate. These cells eventually break out of the gonad and fill the body, killing the animal early in life, which resembles the germline tumors in mammals. Pinkston et al. found that a number of mutations that extended the life span of C. elegans also enhanced p53 activity and conferred resistance to tumors induced by gld-1 mutation. Furthermore, the long life span of daf-2 (insulin-like receptor) mutants could not be shortened by gld-1 mutations due to the increased p53-dependent apoptosis within the tumors.16 These results strongly suggest that increased p53 activity contributes to the life span extension in C. elegans. Interestingly, in a more recent study, Ventura et al.17 reported that depending on the level of mitochondrial bioenergetic stress, Cep-1 can either increase or decrease life span in C. elegans. It has been shown that severely reduced expression of mitochondrial proteins that are involved in electron transport chain-mediated energy production can lead to arrested development and/or shortened life span, whereas mild suppression of these proteins extends life span in C. elegans. Ventura et al. found that Cep-1 mediated these opposite effects on life span in C. elegans. Although Cep-1 was required to extend life span in response to mild suppression of several bioenergetically relevant mitochondrial proteins, Cep-1 also mediated both the developmental arrest and life shortening induced by severe mitochondrial stress. Together, these seemingly conflicting results from the studies in C. elegans suggest that the role of p53 in longevity could be complex and context dependent, which has been supported by the following studies from both fly and mouse models (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Role of p53 Family Members in Longevity

| Organism | p53 Family Members Involved in Longevity | Change of p53 Activity | Impact on Longevity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caenorhabditis elegans | Cep-1 | Knockdown or knockout | Extended | 15 |

| Increased activity in gld-1 mutants | Extended in gld-1 mutants | 16 | ||

| Increased in response to mild mitochondrial stress | Extended | 17 | ||

| Increased in response to severe mitochondrial stress | Reduced | 17 | ||

| Drosophila | Dmp53 | Knockout | Reduced | 18 |

| Overexpression of dominant negative Dmp53 in neuron | Extended | 18 | ||

| Overexpression of Dmp53 in adults | Reduced in females; extended in males | 20 | ||

| Overexpression of Dmp53 in larval stage at high levels | Toxic to development | 20 | ||

| Overexpression of Dmp53 in larval stage at moderate levels | Extended | 20 | ||

| Mice | p53, p63 | Increased activity by N-terminal deleted mutant p53 | Reduced | 21 |

| Increased activity by p44 | Reduced | 23 | ||

| Increased activity in “super p53” mice | No change | 24 | ||

| Increased activity in “MDM2 hypomorphic” mice | No change | 25 | ||

| Increased activity in “p53/Arf” mice | Extended | 26 | ||

| Increased activity in “super Ink4/ARF” mice | Extended | 27 | ||

| p63+/− | Reduced | 28 | ||

| Humans | p53 | Decreased activity in individuals with the p53 P72 allele | Extended | 32, 33, 34 |

p53 and Longevity in Drosophila

Although p53 knockout led to a reduced life span in Drosophila (fly), which is probably due to the negative effects on embryonic development, recently, Bauer and colleagues18 reported that the reduction of p53 activity in specific tissues mediated by dominant negative p53 (DN dmp53) could lead to the delayed aging and extended life span in flies. Expression of DN dmp53, which significantly inhibited the transactivation activity of wild-type p53, in neuronal cells extended life span in flies by up to 58%. Furthermore, this longevity effect was tissue specific since DN Dmp53 expression in muscle or fat body cells did not extend life span in flies. It has been shown that caloric restriction, Sir2 overexpression, and treatment with resveratrol (a molecular activator of Sir2) can all extend life span in flies. Interestingly, it has been found that caloric restriction, Sir2 overexpression, or treatment with resveratrol could not further extend the life span in DN Dmp53-overexpressing flies, suggesting that DN Dmp53, caloric restriction, and Sir2 act through similar pathways of longevity extension.19

Taking advantage of the Drosophila Gene-Switch system that puts transcriptional control of a transgene under temporal control, Waskar et al.20 extensively investigated the impact of p53 on life span by conditional overexpression of both wild-type and DN dmp53 in flies. They first confirmed earlier studies by Helfand’s laboratory,18,19 which demonstrated that the expression of DN dmp53 in neuronal cells extended life span in flies. Surprisingly, they found that ubiquitous overexpression of wild-type p53 in adult flies shortened life span in females but increased life span in males. Furthermore, although overexpression of wild-type p53 at a high level in the larval stage was toxic to larval development, overexpression of p53 at a moderate level extended life span in both males and females.20 Thus, the regulation of life span by p53 in flies is context dependent; it appears to be not only p53 dose specific but also fly tissue, sex, and developmental stage specific.

p53 and Longevity in Mice

The potential role of p53 in regulating aging and longevity in mice has been recently proposed by several studies with different mouse models. The first direct link of p53 with aging in mice was reported by Tyner and colleagues.21 They generated a p53 hypermorphic mouse model, which harbored a mutant p53 allele (m p53) expressing a truncated p53 derived from its carboxyl terminus. The mutant p53 allele contained exons 7-11 and was presumed to be transcriptionally regulated by a promoter of a gene upstream of p53. Although the p53+/m mice were resistant to spontaneous cancers, the mice displayed a shortened life span (decreased by 20%-30%) and premature aging phenotypes, including organ atrophy, skin atrophy, osteoporosis, and reduced tolerance to stresses.21 These effects of mutant p53 protein were dependent on the presence of the wild-type p53 allele since the p53−/m mice developed tumors as early as p53−/− mice. Further studies showed that the mutant p53 protein facilitated the translocation of wild-type p53 into the nucleus and increased the stabilization and activation of wild-type p53.22 It appears that the mutant p53 protein interacts with wild-type p53 protein to increase the activity of wild-type p53, which in turn promotes the aging process in mice. However, there is a caveat for this mouse model since it is haploinsufficient for 24 genes upstream of p53, which might contribute to the premature aging and decreased life span observed in these mice. This potential role of p53 in promoting aging in mice was supported by the following study from Maier et al.,23 who generated a second p53 hypermorphic mouse model expressing a 44-kD truncated naturally occurring isoform of p53 (p44), which lacks the main transactivation domain of p53. The p44+/+ mice displayed enhanced activity and function of p53 and, therefore, were highly tumor resistant. Similarly, these mice displayed a dramatically shortened life span and premature aging phenotypes. Beginning as early as 16 weeks of age, p44+/+ mice showed signs of aging. At 60 weeks of age, 0% of male p44+/+ and only 30% of female p44+/+ mice were alive, whereas 85% and 95% of wild-type males and females were still alive, respectively.23 The results from these two mouse models suggest that constitutively enhanced p53 activity may accelerate the aging process and reduce life span, although it increases tumor resistance.

In contrast to the p53+/m and p44+/+ mouse models, which display that p53 activation promotes aging in mice, the following two p53 hypermorphic mouse models show a different scenario. Garcia-Cao and colleagues24 generated a mouse model with 1 or 2 extra copies of genomic p53 along with flanking regulatory sequences. These “super p53” mice showed enhanced p53 response to DNA damage and were resistant to both spontaneous and carcinogen-induced tumors. Interestingly, they had a normal life span as wild-type mice. This observation was supported by the findings from the MDM2 hypomorphic mouse model generated by Mendrysa and colleagues.25 The MDM2 hypomorphic mice harbored only 1 allele of MDM2, the most critical negative regulator of p53, and therefore had an enhanced p53 response to DNA damage and were tumor resistant. Like the “super p53” mice, the MDM2 hypomorphic mice had a normal life span and did not show premature aging compared with wild-type mice.25 These results suggest that when properly regulated, the enhanced p53 activity increases tumor resistance and does not promote aging in mice.

Recently, Matheu and colleagues26 generated “super p53/Arf” mice, which harbored an extra copy of the p19Arf allele in addition to an extra copy of the p53 allele. Tumor suppressor p19Arf is transcribed from an alternate reading frame of the INK4a/ARF locus. p19Arf inhibits MDM2, thus promoting p53 stabilization in cells. Surprisingly, these mice were not only resistant to tumors but also had an extended life span compared with normal mice and “super p53” mice.26 The same group further generated “super Ink4/Arf” mice carrying 1 or 2 intact additional copies of the Ink4/Arf locus.27 Although the increased gene dosage of Ink4/Arf impaired male fertility, these mice were resistant to tumors and, furthermore, had an extended median life span. The increased survival was also observed in cancer-free mice, indicating that cancer protection and pro-longevity are separable activities of the Ink4/Arf.27 Thus, similar to the findings from both C. elegans and flies, these results from different mouse models suggest that the role of p53 in aging and longevity is complex; it can both promote and prevent aging depending on the context. It appears that the normally regulated but enhanced p53 activity may promote longevity, whereas the aberrantly regulated and constitutively enhanced p53 activity may promote aging, although p53 enhances tumor resistance in mice under both conditions.

p63 is a more ancestral member of the p53 family during evolution. It has been shown that p63 also plays a role in the regulation of aging and longevity. Keyes and colleagues28 reported that p63+/− mice were not tumor prone but displayed features of accelerated aging and had a shortened life span. They further demonstrated that cellular senescence and organismal aging were intimately linked and that these processes were mediated by the loss of p63. Both germline and somatically induced p63 deficiency activated widespread cellular senescence. Using an inducible tissue-specific p63 conditional model, they further showed that p63 deficiency induced cellular senescence and caused accelerated aging phenotypes in the adult. These results suggest a role of p63 in delaying the aging process and promoting longevity.

p53 and Longevity in Humans

The impact of p53 on aging and longevity in humans has been recently indicated by several epidemiological studies. The p53 gene contains a functional common coding single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that results in either an arginine (R72) or a proline (P72) residue at codon 72. The distribution of this polymorphism in populations varies with racial groups. The p53 P72 allele frequency is ~60% in the African population and ~30% in the Caucasian population. It has been reported that the p53 P72 allele has a weaker activity in inducing apoptosis and suppressing cellular transformation29 and has a lower transcriptional activity toward a subset of p53 target genes involved in apoptosis and DNA repair compared with the p53 R72 allele.30 Individuals with the p53 P72 allele have been reported to have increased cancer risk compared with individuals with the p53 R72 allele.31 Recently, van Heemst et al.32 reported that the p53 codon 72 SNP affected longevity in human populations. They found that individuals homozygous for the p53 P72 alleles had a modest increase in cancer incidence compared with the p53 R72 allele (P < 0.05). Most interestingly, in a prospective study of individuals age 85 or older (n = 1226), individuals homozygous for the p53 P72 allele exhibited a significant 41% enhanced survival compared with individuals with at least one p53 R72 allele (P = 0.032), although they had a 2.5-fold increased cancer incidence (P = 0.007). In a second study carried out by Smetannikova et al.,33 the enrichment of the p53 P72 allele was observed in 131 long-livers from Novosibirsk and Tyumen regions. More recently, Ørsted et al.34 investigated the impact of codon 72 SNP on the life span in a cohort of 9219 participants ages 20 to 95 from the Danish general population. They found that the overall 12-year survival was significantly increased in individuals with one p53 P72 allele by 3% (P = 0.003) and in individuals homozygous for the p53 P72 allele by 6% (P = 0.002) compared with individuals homozygous for the p53 R72 allele. The median survival for individuals homozygous for the p53 P72 allele was increased by 3 years compared with individuals homozygous for the p53 R72 allele. They also demonstrated an increased survival after the development of cancer or even after the development of other life-threatening diseases for individuals homozygous for the p53 P72 allele versus the p53 R72 allele.34 These findings suggest that the p53 R72 allele protects against cancer but at the cost of longevity, whereas the p53 P72 allele extends life span at the cost of increased cancer incidence early in life. These results strongly suggest that SNPs in the p53 pathway, which affect p53 activity, regulate longevity in humans.

These results from above-mentioned studies from worms, flies, mice, and humans suggest that p53 is involved in the regulation of aging and longevity, but its role is complex and could be dependent on context (Table 1). The mechanisms by which p53 regulates aging and longevity remain unclear. Several potential mechanisms have been proposed, including the regulation of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and target of rapamycin (TOR) pathways, stem cells, and oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS).

p53, Insulin/IGF-1, and TOR Pathways

The insulin/IGF-1 and TOR pathways are two evolutionarily conserved pathways that play critical roles in the regulation of cell proliferation, survival, and energy metabolism (Figure 1). Studies have demonstrated that insulin/IGF-1 and TOR pathways also play important roles in regulating aging and longevity.35-37 In response to insulin and IGF-1, PI3 kinase (PI3K) is activated, which in turn leads to the activation of PDK1 and PDK2 and resultant phosphorylation and activation of AKT. AKT phosphorylates and regulates several cellular proteins, including FOXO transcription factors, BAD, MDM2, and GSK3α/β, to facilitate cell survival and cell cycle entry.38,39 The FOXO proteins play an important role in longevity regulation. The decreased insulin/IGF-1 signaling induces the translocation of FOXO proteins to the nucleus to initiate a transcription program that induces the expression of antioxidative enzymes, including MnSOD and catalase, and stress resistance inducers. FOXO proteins also play an important role in the regulation of energy metabolism and immune system. These functions all contribute to the role of FOXO in promoting longevity.40,41 On the other hand, AKT can stimulate NF-κB signaling via the activation of the IKK complex. Recent studies have shown a role of NF-κB in the regulation of age-related degenerative processes. The NF-κB pathway plays a critical role in the inhibition of apoptosis and autophagy, which may provoke inflammatory responses during the aging process because of the accumulation of waste products in cells and thus promote the senescent phenotype.42,43 It has been suggested that the decreased insulin/IGF-1 signaling activates FOXO factors and extends life span, whereas excessive and constitutive activation of insulin/IGF-1 signaling triggers NF-κB signaling and accelerates the aging process. It has been well documented that down-regulation of insulin/IGF-1 can extend the life span in different species ranging from worms to mammals. For example, mutations in daf-2 (insulin-like receptor) can extend life span in C. elegans, which requires the activity of daf-16 (FOXO transcription factor).44 Fat-specific insulin receptor knockout mice (FIRKO) or IGF-1 receptor heterozygous mice (IGF-1R+/−) live longer than their wild-type counterparts.45,46 Furthermore, caloric restriction, which reduces the levels of insulin and IGF-1 in serum, has been shown to extend life span and delay the onset of age-associated pathologies in rodents and primates.47,48

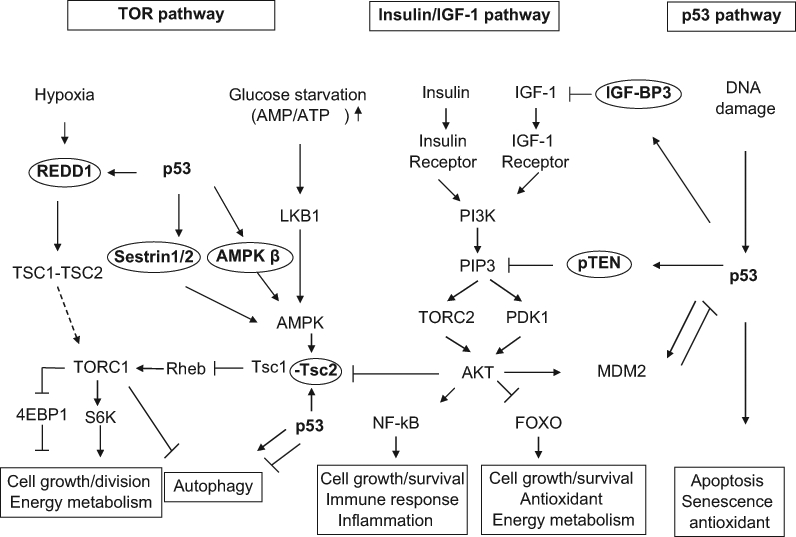

Figure 1.

The coordinated regulation of p53, target of rapamycin (TOR), and insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) pathways. The p53, TOR, and insulin/IGF-1 pathways are three important pathways that regulate aging and longevity. The decreased TOR and insulin/IGF-1 signaling promotes longevity. p53 down-regulates the insulin/IGF-1 and TOR pathways through its transcriptional induction of its target genes, including IGF-BP3, PTEN, TSC2, AMPK β1, sestrin 1/2, and REDD1. AKT-MDM2-p53 forms a negative feedback loop to negatively regulate p53, whereas p53-PTEN-AKT-MDM2 forms a positive loop to positively regulate p53. The insulin/IGF-1 pathway interacts with the TOR pathway through the regulation of TSC2 by AKT.

TOR is a serine/threonine kinase highly conserved from yeast to humans. It forms two complexes in cells, TORC1 and TORC2 (PDK2), which have distinctive physiological functions. As a main upstream kinase of the TORC1, AMPK is activated in response to glucose starvation and low intracellular ATP levels, which in turn phosphorylates and activates the TSC2 protein.49 TSC2 exerts GTPase activity to negatively regulate GTP-binding protein Rheb, which activates TORC1, thus down-regulating TORC1 signaling.50,51 Activated TORC1 promotes protein translation, increases cell mass, and promotes cell growth through the phosphorylation and regulation of two major substrates, the 4EBP1 protein (eIF4E binding protein) and the S6 kinase.52,53 Furthermore, TORC1 also negatively regulates autophagy.54,55 The insulin/IGF-1 pathway regulates TORC1 through AKT, which phosphorylates and inactivates TSC2, and in turn leads to the activation of TORC1. It has been firmly established that reduction in TORC1 activity extends life span in C. elegans and flies. In C. elegans, knockdown or mutation of let-363 (TOR) or rsks-1 (S6 kinase) extends the life span.56,57 In flies, a dominant negative allele of TOR, hypomorphic allele of TOR, and overexpression of TSC2 have all been reported to extend life span.37,58 A recent study reported that dietary supplementation with rapamycin starting at 600 days of age in mice significantly extended the life span, which strongly suggests that reduced TOR signaling can increase life span in mammals.59

p53 has been shown to interact closely with insulin/IGF-1 and TOR pathways, two critical pathways that regulate aging and longevity (Figure 1). p53 can down-regulate the activities of insulin/IGF-1 and TOR pathways by inducing the expression of a set of p53 target genes in these two pathways, including IGF-BP3, PTEN, TSC2, AMPK β1, sestrins 1 and 2, and REDD1.60-65 IGF-BP3 binds to IGF-1 and prevents its binding to IGF-1 receptors, thus down-regulating insulin/IGF-1 signaling. As a PIP3 phosphatase, PTEN degrades PIP3 to PIP2, which leads to the inactivation of PDK1 and TORC2, thus decreasing AKT activity. p53 also induces TSC2 and β-subunits of AMPK to down-regulate TORC1.60,61 p53 induces the expression of sestrin 1 and sestrin 2, which leads to the activation of AMPK and TSC2, resulting in the inhibition of TORC1 activity.62 p53 also induces the REDD1 expression to down-regulate TORC1 activity in response to hypoxia.63 Furthermore, p53 activation can also activate autophagy through the down-regulation of TORC1 signaling.60

Thus, through the transcriptional regulation of 7 different target genes, p53 negatively regulates the insulin/IGF-1 and TOR signaling, creating an inter-pathway network that permits cells to inhibit cell growth and division to avoid the introduction of errors during these processes under stress conditions. In this way, p53 increases the fidelity of these processes over the lifetime of an organism. At the same time, since decreased TOR/insulin/IGF-1 signaling extends life span, p53 may regulate aging and longevity through its down-regulation of the signaling of these two critical pathways. Recent studies suggest that the functions of TOR/insulin/IGF-1 signaling could be context dependent, and furthermore, the p53 regulation of these two pathways could be context dependent. For example, although TOR is normally associated with cell growth, recent studies reported that TOR activation is essential for some types of senescence in certain contexts.66,67 It has been suggested that IGF-1/AKT signaling enhances growth of animals during development but can potentiate the aging process later in life.68 It has also been suggested that the functions of TOR in different tissues could be different.37 Furthermore, the regulation of these two pathways by p53 could be context dependent. Previously, we found that p53 regulates aforementioned target genes in these two pathways in a cell type–specific, tissue-specific, and stress-specific manner.61 Although wild-type p53 has been shown to decrease insulin/IGF-1 signaling in many different types of cells in both humans and mice,60-62,69 DN dmp53 expression in fly neuronal cells has been reported to inhibit insulin/IGF-1 signaling in adult fly brain,70 and p44+/+ mice displayed increased insulin/IGF-1 signaling.23 Previously, we have shown that activities and functions of p53 and its upstream ATM kinase decline in aged mice, which suggests that the decline of p53 function with age could be an additional mechanism for increased tumor incidence in aged populations.71,72 The decline of p53 activity with age may result in the activation of TOR and insulin/IGF-1 signaling and potentiate the aging process late in life. Furthermore, depending on the context, p53 has been shown to be able to activate or inactive autophagy,73,74 a major outcome of TOR signaling and a biological process heavily involved in the aging process. Therefore, the context-dependent function of TOR/insulin/IGF-1 pathways in the regulation of longevity, as well as the context-dependent function of p53 in the regulation of these two pathways, may contribute to the context-dependent role of p53 in longevity regulation.

p53 and Stem Cells

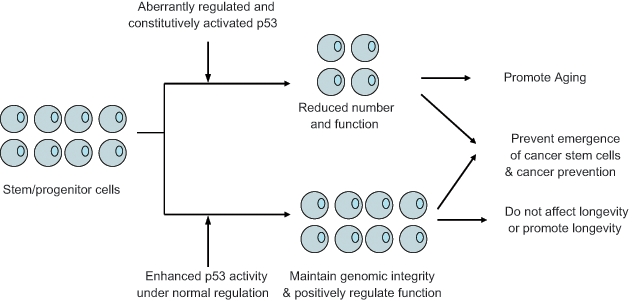

Multicellular organisms, especially mammals, are dependent on a variety of rare stem and progenitor cells that function to replace somatic cells and tissues as they get damaged, die, or otherwise lost. The “stem cell aging” hypothesis suggests that a fundamental mechanism of aging is that as stem/progenitor cells grow older, they become quiescent and/or die.75,76 Thus, the regenerative function of stem/progenitor cells to replace these lost somatic cells and tissues declines progressively with age. Stem and progenitor cells grow old because of heritable intrinsic events, such as DNA damage, and cell-extrinsic events, such as alterations in their supporting niches.75,76 Recent studies have suggested an important role of p53 in maintaining genomic stability in stem cells through coordinating the self-renewal ability and DNA damage responses of stem cells.77,78 Although the activities of p53, including apoptosis and senescence, may play an important role in preventing the emergence of cancer stem cells to prevent tumorigenesis, constitutive p53 activation may lead to the decline of self-renewal function of stem/progenitor cells and therefore contribute to aging (Figure 2). For example, p53-mediated apoptosis can irreversibly deplete stem/progenitor cells from tissues and contribute to organ degeneration. p53-mediated senescence can deplete stem/progenitor cells since senescent cells lose proliferation ability and can no longer participate in tissue renewal and repair. Furthermore, senescent cells can alter the tissue microenvironment, which promotes the degeneration of organs and stem cell niches. It has been shown that senescent cells accumulate with age in vivo.75,76 Interestingly, the p53+/m mice with accelerated aging phenotypes displayed reduced self-renewal and differentiation potential of stem cells and, furthermore, displayed an enhanced age-associated accumulation of senescent cells compared with wild-type mice.79,80 Similarly, the p44+/+ mice displaying accelerated aging also showed defects in the number and regenerative potential of neural progenitor cells.81 On the other hand, down-regulation of p53 activity leads to the enhanced stem cell regenerative capacity.80,82-84 p53 deficiency in hematopoietic multipotent progenitor cells and neural stem/progenitor cells has been shown to contribute to enhanced proliferative capacity of these cells.85,86 Together, these results demonstrate that alteration of p53 activity affects the numbers, self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells, which may contribute to the role of p53 in regulating aging and longevity (Figure 2). It has been suggested that when properly regulated, enhanced p53 activity may prevent the emergence of cancer stem cells but not inhibit the function of stem cells or even have beneficial effects on stem cells.87 As observed in “super p53” and “super p53/Arf” mice, enhanced p53 activity increases tumor resistance and does not affect life span or even increases life span. In contrast, when aberrantly regulated, constitutively enhanced p53 activity may impair the function of stem cells, thus promoting aging. As observed in p53+/m and p44+/+ mice, constitutively enhanced p53 activity increases tumor resistance but decreases life span.

Figure 2.

The regulation of stem/progenitor cells and longevity by p53. p53 may regulate longevity through its regulation of stem/progenitor cell functions. When properly regulated, enhanced p53 activity may prevent the emergence of cancer stem cells but not inhibit the function of stem cells or even have beneficial effects on stem/progenitor cells. Thus, enhanced p53 activity increases tumor resistance and does not affect life span or even extends life span in organisms, such as “super p53” mice, MDM2 hypomorphic mice, and “super p53/Arf” mice. In contrast, when aberrantly regulated, constitutively enhanced p53 activity may reduce the number of stem/progenitor cells and impair their functions, thus promoting aging, although it also increases tumor resistance, such as in p53+/m and p44 mice.

p53, Oxidative Stress, and ROS

Oxidative stress and ROS are generally believed to be an important contributor to both age-related cancer and aging. ROS are the natural by-products of the metabolism of oxygen and are highly reactive intermediates capable of modifying numerous biological substrates, including cellular lipids, proteins, and, most important, DNA. Endogenous ROS levels are the major source of DNA damage and contribute significantly to DNA mutations and chromosome instability. Increased intracellular ROS levels and loss of antioxidant defense pathways in cells have been shown to result in cancer and aging.88-92 However, some recent studies have raised questions challenging the role of oxidative stress and ROS in aging.93

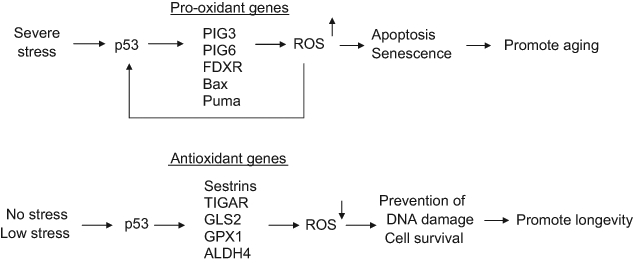

Recent studies have shown that p53 can exert both pro-oxidant and antioxidant functions in cells depending on the type and extent of stress signals that activate p53 (Figure 3), which could be a potential mechanism accounting for the dual activities of p53 in both promoting and preventing aging. It has been demonstrated that under severe oxidative stress conditions, high levels of ROS can activate p53, which in turn leads to the p53-mediated apoptosis and senescence.94,95 Furthermore, activated p53 protein induces the expression of a set of pro-oxidant genes, including PIG3, PIG6, FDXR, Bax, and Puma.95-98 The induction of these pro-oxidant genes can all increase intracellular ROS levels and further sensitize cells to oxidative stress to eliminate damaged cells through p53-mediated apoptosis and senescence. On the other hand, under conditions of nonstress or low stress, p53 can exert its antioxidant function to reduce the ROS levels in cells and prevent oxidative stress-induced DNA damage and promote cell survival. p53 induces the expression of a set of antioxidant genes to lower ROS levels, including sestrins, TIGAR, GLS2, GPX1, and ALDH4. Sestrins are a family of proteins required for regeneration of peroxiredoxins, which are a family of thiol-containing peroxidases and major reductants of endogenously produced peroxides in eukaryotes.99 TIGAR diverts glucose through the pentose phosphate pathway that produces more NADPH to lower ROS levels.100 Recently, our lab and another lab independently identified GLS2 as a p53-regulated gene involved in reducing ROS levels.101,102 GLS2 increases the levels of GSH and NADH, important antioxidants in cells, to reduce ROS levels and protect cells from oxidative stress–induced cell death.101 GPX1 is a primary antioxidant enzyme that scavenges hydrogen peroxide or organic hydroperoxides in cells. As a mitochondrial enzyme catalyzing the proline degradation pathway, ALDH4 lowers intracellular ROS levels through its regulation of proline metabolism.103 It is possible that through the modulation of ROS levels, p53 might contribute to both longevity and aging, depending on the stress conditions. Although mild stress could lead to the p53-induced antioxidant function, which decreases ROS and oxidative damage to promote longevity, strong and persistent stress could lead to persistent p53 activation, which leads to the p53-induced pro-oxidant function to promote apoptosis and senescence of stem/progenitor cells and thus aging (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The regulation of oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and longevity by p53. p53 exerts either pro-oxidant or antioxidant activity depending on the type and extent of stress signals, which may contribute to its role in both promoting and preventing aging. p53 selectively induces the expression of a group of antioxidant genes, such as sestrins, TIGAR, GLS2, GPX1, and ALDH4, to lower ROS levels in cells under the conditions of nonstress or low stress. This antioxidant function of p53 protects cells from oxidative stress–induced DNA damage and allows cell survival, which may prevent aging. In response to severe stress, p53 selectively induces the expression of a group of pro-oxidant genes, including PIG3, PIG6, FDRX, Bax, and Puma, to further increase ROS levels in cells. This pro-oxidant function of p53 leads to the p53-mediated apoptosis and senescence to eliminate damaged cells, including stem/progenitor cells, which may promote the aging process.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The results from aforementioned various worm, fly, and mouse models and human population studies have strongly suggested that p53 is an important but complex player in aging and longevity; p53 can both promote and prevent aging in a context-dependent manner. This was most clearly demonstrated by the study by Waskar et al.20 showing that p53 influences life span in flies in p53 dose-specific, fly tissue–specific, developmental stage–specific, and sex-specific manners. Furthermore, the type and extent of stress that activates p53 could also be a factor to determine whether p53 promotes aging or longevity. For example, Ventura et al.17 have shown that Cep-1 can either increase or decrease life span in C. elegans depending on the level of mitochondrial bioenergetic stress; in response to mild mitochondrial stress, Cep-1 extended life span, whereas in response to severe mitochondrial stress, Cep-1 mediated the developmental arrest and reduced life span in C. elegans. This is also consistent with the dual functions of p53 to either exert antioxidant activity and favor cell survival or exert pro-oxidant activity and promote apoptosis and senescence.92,94 It will be of interest to investigate whether p53 affects aging and longevity in mammals in a similar manner, as observed in both worms and flies. Manipulating p53 expression in mouse models in p53 dose-specific, mouse tissue–specific, developmental stage–specific, and sex-specific manners may further shed light on the role of p53 in aging and longevity in mammals.

Naturally occurring SNPs in p53 and its signaling pathway, which affect the activities of p53 and its family members, including p63 and p73, provide a good opportunity for us to study the role of p53 and its family members in the regulation of aging and longevity in humans. Studies on the p53 codon 72 SNP have suggested a potential role of p53 in the regulation of human longevity.32-34 Studying the impact of other functional SNPs in the p53 pathway in addition to p53 codon 72 SNP on longevity and combinatory effects of these SNPs on longevity will further shed light on the role of p53 in human longevity. Recently, Bond et al.104 identified a functional SNP (SNP309, a T to G change) in the regulatory region in the first intron of the MDM2 gene, a key negative regulator of p53. SNP309 creates a stronger Sp1 binding site, which results in 2- to 4-fold increased transcriptional levels of MDM2 and, therefore, the attenuation of p53.104,105 SNP309 has been shown to be associated with increased risk for cancer in both humans and SNP309 knock-in mice.104,106 It will be of interest to study whether SNP309 affects the life span in human populations and whether p53 codon 72 SNP and SNP309 have a combinatory effect on human life span.

Recent studies have demonstrated that p53 is emerging as an important but complex player in aging and longevity. Although it has been firmly established that p53 is a longevity assurance gene by preventing early tumors in life, the role and mechanisms of p53 in regulating aging and longevity independently of its tumor-suppressive function are still not well understood. Obviously, many further studies will be required to fully understand the complex role of p53 in the regulation of aging and longevity and its underlying mechanisms.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Z. Feng is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA143204-01), New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research (09-1970-CCR-EO), and the Foundation of UMDNJ.

References

- 1. Levine AJ, Hu W, Feng Z. The P53 pathway: what questions remain to be explored? Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1027-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levine AJ, Oren M. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feng Z, Levine AJ. The regulation of energy metabolism and the IGF-1/mTOR pathways by the p53 protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:427-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jin S, Martinek S, Joo WS, et al. Identification and characterization of a p53 homologue in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7301-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng R, Ford BL, O’Neal PE, et al. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) p53 tumor suppressor gene: cDNA sequence and expression during embryogenesis. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1997;6:88-97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soussi T, Caron de Fromentel C, Mechali M, May P, Kress M. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA from Xenopus laevis coding for a protein homologous to human and murine p53. Oncogene. 1987;1:71-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ. p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF. Nature. 2007;450:721-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu W. The role of p53 gene family in reproduction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suh EK, Yang A, Kettenbach A, et al. p63 protects the female germ line during meiotic arrest. Nature. 2006;444:624-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomasini R, Tsuchihara K, Wilhelm M, et al. TAp73 knockout shows genomic instability with infertility and tumor suppressor functions. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2677-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arum O, Johnson TE. Reduced expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans p53 ortholog cep-1 results in increased longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:951-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pinkston JM, Garigan D, Hansen M, Kenyon C. Mutations that increase the life span of C. elegans inhibit tumor growth. Science. 2006;313:971-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ventura N, Rea SL, Schiavi A, Torgovnick A, Testi R, Johnson TE. p53/CEP-1 increases or decreases lifespan, depending on level of mitochondrial bioenergetic stress. Aging Cell. 2009;8:380-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bauer JH, Poon PC, Glatt-Deeley H, Abrams JM, Helfand SL. Neuronal expression of p53 dominant-negative proteins in adult Drosophila melanogaster extends life span. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2063-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bauer JH, Morris SN, Chang C, Flatt T, Wood JG, Helfand SL. dSir2 and Dmp53 interact to mediate aspects of CR-dependent lifespan extension in D. melanogaster. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1:38-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waskar M, Landis GN, Shen J, et al. Drosophila melanogaster p53 has developmental stage-specific and sex-specific effects on adult life span indicative of sexual antagonistic pleiotropy. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1:903-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002;415:45-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moore L, Lu X, Ghebranious N, Tyner S, Donehower LA. Aging-associated truncated form of p53 interacts with wild-type p53 and alters p53 stability, localization, and activity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:717-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maier B, Gluba W, Bernier B, et al. Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev. 2004;18:306-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia-Cao I, Garcia-Cao M, Martin-Caballero J, et al. “Super p53” mice exhibit enhanced DNA damage response, are tumor resistant and age normally. EMBO J. 2002;21:6225-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mendrysa SM, O’Leary KA, McElwee MK, et al. Tumor suppression and normal aging in mice with constitutively high p53 activity. Genes Dev. 2006;20:16-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matheu A, Maraver A, Klatt P, et al. Delayed ageing through damage protection by the Arf/p53 pathway. Nature. 2007;448:375-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matheu A, Maraver A, Collado M, et al. Anti-aging activity of the Ink4/Arf locus. Aging Cell. 2009;8:152-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keyes WM, Wu Y, Vogel H, Guo X, Lowe SW, Mills AA. p63 deficiency activates a program of cellular senescence and leads to accelerated aging. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1986-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dumont P, Leu JI, Della Pietra AC, III, George DL, Murphy M. The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential. Nat Genet. 2003;33:357-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeong BS, Hu W, Belyi V, Rabadan R, Levine AJ. Differential levels of transcription of p53-regulated genes by the arginine/proline polymorphism: p53 with arginine at codon 72 favors apoptosis. FASEB J. 2010;24:1347-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pietsch EC, Humbey O, Murphy ME. Polymorphisms in the p53 pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:1602-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Heemst D, Mooijaart SP, Beekman M, et al. Variation in the human TP53 gene affects old age survival and cancer mortality. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:11-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smetannikova MA, Beliavskaia VA, Smetannikova NA, et al. Functional polymorphism of p53 and CCR5 genes in the long-lived of the Siberian region [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2004:25-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ørsted DD, Bojesen SE, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Tumor suppressor p53 Arg72Pro polymorphism and longevity, cancer survival, and risk of cancer in the general population. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1295-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120:449-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bishop NA, Guarente L. Genetic links between diet and lifespan: shared mechanisms from yeast to humans. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:835-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stanfel MN, Shamieh LS, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK. The TOR pathway comes of age. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1067-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bader AG, Kang S, Zhao L, Vogt PK. Oncogenic PI3K deregulates transcription and translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:921-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Calnan DR, Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van der Horst A, Burgering BM. Stressing the role of FoxO proteins in lifespan and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:440-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kriete A, Mayo KL. Atypical pathways of NF-kappaB activation and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:250-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. Glycolysis links p53 function with NF-kappaB signaling: impact on cancer and aging process. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224:1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burnell AM, Houthoofd K, O’Hanlon K, Vanfleteren JR. Alternate metabolism during the dauer stage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:850-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bluher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, et al. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature. 2003;421:182-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Al-Regaiey KA, Masternak MM, Bonkowski M, Sun L, Bartke A. Long-lived growth hormone receptor knockout mice: interaction of reduced insulin-like growth factor i/insulin signaling and caloric restriction. Endocrinology. 2005;146:851-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fontana L. The scientific basis of caloric restriction leading to longer life. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:144-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, et al. The LKB1 tumor suppressor negatively regulates mTOR signaling. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:91-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:19-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Inoki K, Guan KL. Tuberous sclerosis complex, implication from a rare genetic disease to common cancer treatment. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R94-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hannan KM, Brandenburger Y, Jenkins A, et al. mTOR-dependent regulation of ribosomal gene transcription requires S6K1 and is mediated by phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal activation domain of the nucleolar transcription factor UBF. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8862-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. 2005;123:569-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hansen M, Taubert S, Crawford D, Libina N, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Lifespan extension by conditions that inhibit translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:95-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Curran SP, Ruvkun G. Lifespan regulation by evolutionarily conserved genes essential for viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kapahi P, Zid BM, Harper T, Koslover D, Sapin V, Benzer S. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2004;14:885-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8204-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Feng Z, Hu W, de Stanchina E, et al. The regulation of AMPK beta1, TSC2, and PTEN expression by p53: stress, cell and tissue specificity, and the role of these gene products in modulating the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3043-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Budanov AV, Karin M. p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell. 2008;134:451-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM, et al. REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2002;10:995-1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Stambolic V, MacPherson D, Sas D, et al. Regulation of PTEN transcription by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;8:317-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Buckbinder L, Talbott R, Velasco-Miguel S, et al. Induction of the growth inhibitor IGF-binding protein 3 by p53. Nature. 1995;377:646-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Growth stimulation leads to cellular senescence when the cell cycle is blocked. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3355-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Maki CG. Decision-making by p53 and mTOR. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:324-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. Insulin/IGF-1 paradox of aging: regulation via AKT/IKK/NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Signal. 2010;22:573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Braunstein S, Badura ML, Xi Q, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Regulation of protein synthesis by ionizing radiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5645-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bauer JH, Chang C, Morris SN, et al. Expression of dominant-negative Dmp53 in the adult fly brain inhibits insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13355-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feng Z, Hu W, Teresky AK, Hernando E, Cordon-Cardo C, Levine AJ. Declining p53 function in the aging process: a possible mechanism for the increased tumor incidence in older populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16633-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Feng Z, Hu W, Rajagopal G, Levine AJ. The tumor suppressor p53: cancer and aging. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:842-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Balaburski GM, Hontz RD, Murphy ME. p53 and ARF: unexpected players in autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:363-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O, Malik SA, Kroemer G. Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:181-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sahin E, Depinho RA. Linking functional decline of telomeres, mitochondria and stem cells during ageing. Nature. 2010;464:520-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sharpless NE, Schatten G. Stem cell aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:202-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhao T, Xu Y. p53 and stem cells: new developments and new concerns. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:170-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Puzio-Kuter AM, Levine AJ. Stem cell biology meets p53. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:914-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gatza CE, Dumble M, Kittrell F, et al. Altered mammary gland development in the p53+/m mouse, a model of accelerated aging. Dev Biol. 2008;313:130-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dumble M, Moore L, Chambers SM, et al. The impact of altered p53 dosage on hematopoietic stem cell dynamics during aging. Blood. 2007;109:1736-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Medrano S, Burns-Cusato M, Atienza MB, Rahimi D, Scrable H. Regenerative capacity of neural precursors in the adult mammalian brain is under the control of p53. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:483-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shounan Y, Dolnikov A, MacKenzie KL, Miller M, Chan YY, Symonds G. Retroviral transduction of hematopoietic progenitor cells with mutant p53 promotes survival and proliferation, modifies differentiation potential and inhibits apoptosis. Leukemia. 1996;10:1619-28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hirabayashi Y, Matsuda M, Aizawa S, Kodama Y, Kanno J, Inoue T. Serial transplantation of p53-deficient hemopoietic progenitor cells to assess their infinite growth potential. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2002;227:474-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. TeKippe M, Harrison DE, Chen J. Expansion of hematopoietic stem cell phenotype and activity in Trp53-null mice. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:521-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Akala OO, Park IK, Qian D, Pihalja M, Becker MW, Clarke MF. Long-term haematopoietic reconstitution by Trp53−/−p16Ink4a−/−p19Arf−/− multipotent progenitors. Nature. 2008;453:228-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zheng H, Ying H, Yan H, et al. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1129-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Donehower LA. Using mice to examine p53 functions in cancer, aging, and longevity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lu W, Ogasawara MA, Huang P. Models of reactive oxygen species in cancer. Drug Discov Today Dis Models. 2007;4:67-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Nicholls D. Mitochondrial bioenergetics, aging, and aging-related disease. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2002;2002:pe12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Benhar M, Engelberg D, Levitzki A. ROS, stress-activated kinases and stress signaling in cancer. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:420-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ho YS, Xiong Y, Ma W, Spector A, Ho DS. Mice lacking catalase develop normally but show differential sensitivity to oxidant tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32804-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vigneron A, Vousden KH. p53, ROS and senescence in the control of aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:471-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Blagosklonny MV. Aging: ROS or TOR. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3344-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Bensaad K, Vousden KH. p53: new roles in metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:286-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:1-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rivera A, Maxwell SA. The p53-induced gene-6 (proline oxidase) mediates apoptosis through a calcineurin-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29346-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Lyakhov IG, Krishnamachari A, Schneider TD. Discovery of novel tumor suppressor p53 response elements using information theory. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3828-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Liu G, Chen X. The ferredoxin reductase gene is regulated by the p53 family and sensitizes cells to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:7195-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science. 2004;304:596-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hu W, Zhang C, Wu R, Sun Y, Levine A, Feng Z. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7455-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Suzuki S, Tanaka T, Poyurovsky MV, et al. Phosphate-activated glutaminase (GLS2), a p53-inducible regulator of glutamine metabolism and reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7461-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yoon KA, Nakamura Y, Arakawa H. Identification of ALDH4 as a p53-inducible gene and its protective role in cellular stresses. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:134-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bond GL, Hu W, Bond EE, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans. Cell. 2004;119:591-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hu W, Feng Z, Ma L, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene disrupts the oscillation of p53 and MDM2 levels in cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2757-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Post SM, Quintas-Cardama A, Pant V, et al. A high-frequency regulatory polymorphism in the p53 pathway accelerates tumor development. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:220-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]