Abstract

Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) has an important role in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced NF-κB activation. Using a functional genomic approach, we have identified ubiquitin-specific peptidase 4 (USP4) as a deubiquitinase for TAK1. USP4 deubiquitinates TAK1 in vitro and in vivo. TNFα induces association of USP4 with TAK1 to deubiquitinate TAK1 and downregulate TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation. Overexpression of USP4 wild type, but not deuibiquitinase-deficient C311A mutant, inhibits both TNFα- and TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and NF-κB activation. Notably, knockdown of USP4 in HeLa cells enhances TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination, IκB kinase phosphorylation, IκBα phosphorylation and ubiquitination, as well as NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Moreover, USP4 negatively regulates IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation. Together, our results demonstrate that USP4 serves as a critical control to downregulate TNFα-induced NF-κB activation through deubiquitinating TAK1.

Keywords: TAK1, NF-κB, USP4, deubiquitination, TNFα

Transcription factor NF-κB is involved in the regulation of a broad range of cellular responses such as inflammation, immunity, development, cell proliferation and apoptosis by controlling the expression of NF-κB-dependent survival factors, cytokines and proinflammatory molecules.1, 2, 3 In its resting state, NF-κB exists in a stable cytosolic complex with a member of the inhibitor κB (IκB) family. Activation of an intracellular signal transduction pathway induced by various stimuli leads to the IκB phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subsequent degradation through the 26S proteasome.4, 5, 6 The degradation of IκBα exposes a nuclear translocation sequence facilitating translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and activates the expression of the target genes.7

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), a proinflammatory cytokine, exerts its function through activating NF-κB along with other transcription factors.8, 9 On binding of TNFα, TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) recruits TNF-receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 1/2 (cIAP1/2) E3 ligases to form a complex that subsequently leads to Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) and TRAF2.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Some evidence shows that TRAF2 does not possess E3 ligase activity and acts as a scaffold protein to recruit cIAP1/2 E3 ligases to ubiquitinate RIPK1, whereas others suggest that TRAF2 acts as an E3 ligase with cofactor sphingosine-1-phosphate to ubiquitinate RIPK1.15, 16, 17 However, the molecular mechanism of TRAF2 and cIAP1/2 functional interaction remains uncertain.

On TNFα binding, TRAF2- and cIAP1/2-mediated Lys63-linked RIPK1 and TRAF2 polyubiquitination further recruits and activates transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) through binding of the TAK1 regulatory subunits TAB2 and TAB3 to the Lys63-polyubiquitinated chains. After recruiting TAK1 to the complex, TAK1 is polyubiquitinated and activated to recruit IκB kinase (IKK) complex via Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated TAK1 and RIPK1.18 Then the activated TAK1 triggers the activation of the IKK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK,19, 20, 21, 22, 23 which lead to activation of transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1.24 Interestingly, genetic evidence shows that TAK1 but not RIPK1 is essential for TNFα-induced NF-κB activation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs).25, 26 It is possible that TRAF2 and cIAP1/2 can mediate Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination and activation in a RIPK1-independent manner.

TAK1, a member of the MAPKKK family, is essential in TNFα-mediated activation of NF-κB, JNK and p38.22, 25, 27, 28 TAK1 regulatory subunits including TAB1, TAB2, TAB3 and TAB4 are involved in the regulation of TAK1 activity in response to TNFα stimulation. TAB1 is a TAK1-interacting protein and induces TAK1 kinase activity through promoting autophosphorylation of key serine/threonine sites of the kinase activation loop.29 TAB1 is an inactive pseudophosphatase sharing homology with members of the PPM family of protein serine/threonine phosphatases.30 TAB2, TAB3 and TAB4 are involved in the regulation of TAK1 activation through binding to polyubiquitinated proteins and promoting a larger complex formation during TNFα-induced TAK1 activation.22, 31

Protein ubiquitination has an essential role in the positive and negative regulation of TNFα-mediated NF-κB signal transduction pathway.11 Recently, TRAF6-mediated Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination has been shown to correlate with TAK1 activation in TGF-β signaling.32, 33 TRAF2- and TRAF6-mediated TAK1 Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination have been suggested to be essential for TNFα- and IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation.18, 34, 35 However, the molecular mechanism of TAK1 deubiquitination in the negative regulation of TNFα-induced NF-κB activation remains poorly understood.

Protein ubiquitination can be reversed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which specifically cleave the isopeptide bond at the C-terminus of ubiquitin (Ub). The human genome encodes ∼95 putative DUBs that are divided into five subclasses based on their Ub-protease domains.36 The Ub-specific peptidases (USPs) represent the largest subclass of DUBs. In this study, we used a functional genomic approach to identify the USPs that are involved in the deubiquitination of TAK1 by screening a library of USPs whose overexpression inhibits TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation. In this study, we present evidence that USP4 functions as a TAK1 deubiquitinase that deubiquitinates TAK1 and downregulates TNFα-induced NF-κB activation.

Results

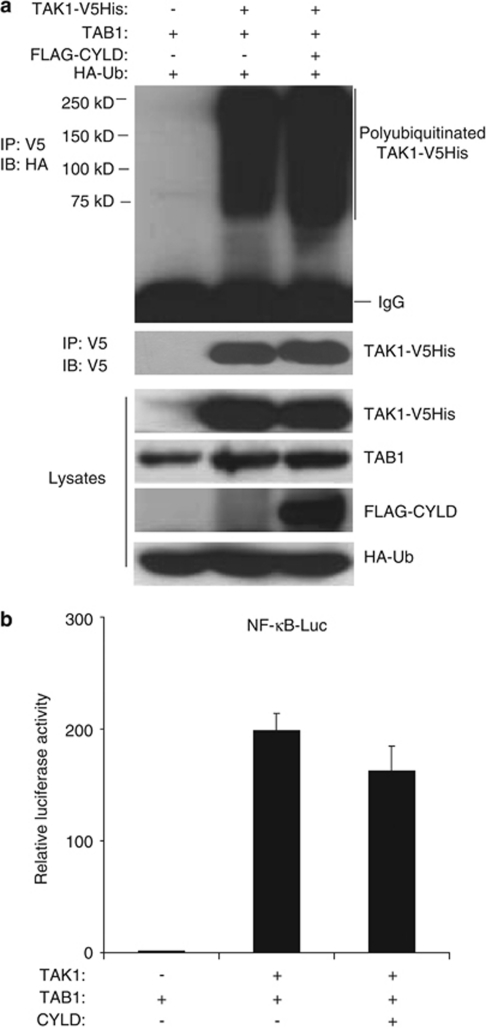

CYLD does not inhibit TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination

Growing evidence suggests that protein ubiquitination and deubiquitination have an essential role in the tight regulation of the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation.37 TRAF2-mediated Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination is critical for the TNFα-induced TAK1 activation.18, 34 Previously, CYLD has been suggested to have a critical role in regulation of TAK1 deubiquitination in T cells.38 However, CYLD knockout has no effect in TNFα-induced NF-κB activation in macrophages, whereas CYLD-knockout karatinocytes show elevated NF-κB activation in response to TNFα stimulation.39, 40, 41 To clarify the role of CYLD in TAK1 deubiquitination, we co-transfected expression vectors encoding HA–Ub, TAK1-V5His and TAB1 with vector control or expression vector encoding FLAG–CYLD into HEK-293T cells. TAK1-V5His proteins were then immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Surprisingly, we found that overexpression of FLAG–CYLD failed to inhibit TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination (Figure 1a). Consistent with this result, we also found that overexpression of CYLD did not inhibit TAK1 and TAB1 co-overexpression-induced NF-κB activation in a reporter assay (Figure 1b). Together, these results suggest that another DUB other than CYLD acts as a major DUB for TAK1.

Figure 1.

CYLD does not inhibit TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and NF-κB activation. (a) CYLD has no inhibitory effect on TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination. HA–Ub, TAK1–V5His and TAB1 expression vectors were cotransfected with empty vector or FLAG–CYLD expression vector into HEK-293T cells. TAK1–V5His in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibodies to detect the presence of ubiquitinated TAK1–V5His. (b) CYLD has no significant inhibitory effect on TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced NF-κB activation. TAK1 and TAB1 expression vectors were cotransfected with empty vector or CYLD expression vector along with NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors into HEK-293T cells for 36 h. Cells were then lysed and the relative luciferase activity in the cell lysates was measured and normalized with the Renilla activity. Error bars indicate ± S.D. in triplicate experiments

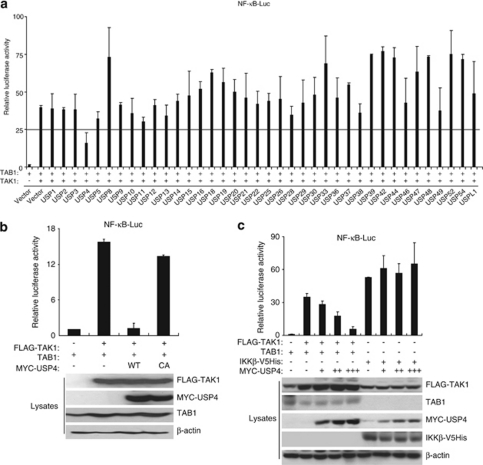

USP4 inhibits TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-mediated NF-κB activation

To explore whether a member of DUBs in the USP sub-class is involved in the deubiquitination of TAK1 and downregulation of TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation, we generated a library of mammalian expression vectors that encode 38 USPs. To avoid the potential inhibitory effect of tag sequence on deubiquitinase enzymatic activity, we did not put any tag into the deubiquitinase protein coding sequence in this USP expression library. Then we used an NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter assay to assess the effects of overexpression of each USP on the TAK1-induced NF-κB luciferase reporter activity. In this screen, USP4 significantly inhibited the TAK1-induced NF-κB luciferase reporter activity, whereas other USPs had no or less effects (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

USP4 inhibits TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced NF-κB activation. (a) The effect of overexpression of members of USP subclass of deubiquitinase on TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced NF-κB activation. TAK1 and TAB1 expression vectors were cotransfected with empty vector or expression vectors encoding different USPs along with NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors into HEK-293T cells for 36 h. (b) USP4 deubiquitinase activity is required for its inhibitory effect on TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced NF-κB activation. FLAG–TAK1 and TAB1 expression vectors were cotransfected with empty vector or expression vectors encoding USP4-WT or -C311A mutant along with NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors into HEK-293T cells for 36 h. FLAG–TAK1, MYC–USP4 and TAB1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoblotted with respective antibodies and β-actin is a loading control. (c) USP4 inhibits TAK1/TAB1 but not IKKβ overexpression-induced NF-κB activation. FLAG–TAK1/TAB1 or IKKβ–V5His expression vectors were cotransfected with empty vector or increasing amount of MYC–USP4 expression vectors along with NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors into HEK-293T cells for 36 h. FLAG–TAK1, IKKβ–V5His, MYC–USP4 and TAB1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoblotted with respective antibodies indicated and β-actin is a loading control

To examine whether the inhibitory effect of overexpression of USP4 on the TAK1-induced NF-κB reporter activity is due to their deubiquitinase activity, we generated an expression vector encoding MYC-tagged USP4 deubiquitinase-deficient mutant by substitution of a cysteine residue in the USP active site with an alanine (C311A) and found that only USP4 wild type (USP4-WT), but not deubiquitinase-deficient C311A mutant, inhibited the TAK1-induced NF-κB activation in a reporter assay in HEK-293T cells (Figure 2b). We also found that overexpression of USP4 inhibited TAK1 but not IKKβ-induced NF-κB activation in a reporter assay (Figure 2c). Furthermore, we found that overexpression of USP4-WT inhibited TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1, IKK and MAPK phosphorylation in HEK-293T cells, whereas TAK1 C311A mutant and CYLD had no any inhibitory effect (Supplementary Figure S1). Consistent with the above results, USP4-WT significantly inhibited TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced NF-κB-dependent reporter, whereas USP4-C311A mutant and CYLD had no significant inhibitory effect (Supplementary Figure S2). This result suggests that USP4 acts as a TAK1 deubiquitinase to inhibit TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation.

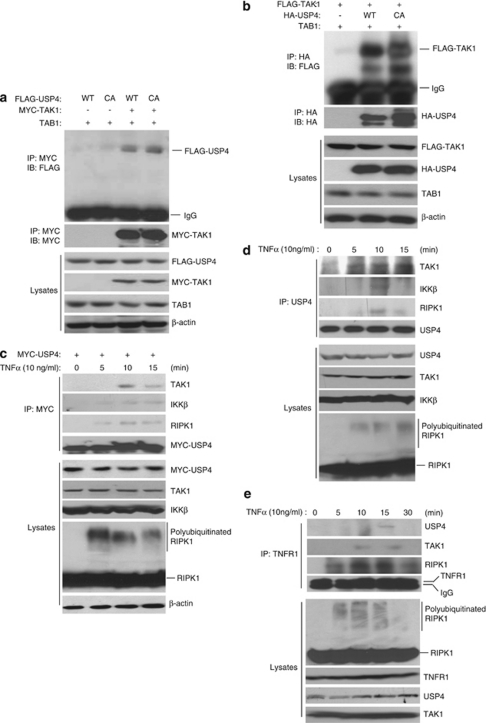

USP4 binds to overexpressed TAK1 with TAB1 and TNFα induces association of USP4 with TAK1

To determine the molecular mechanism of USP4 function in TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation, we cotransfected TAB1 and MYC–TAK1 expression vectors along with FLAG–USP4-WT and -C311A mutant expression vectors in HEK-293T cells. In this assay, we found that MYC–TAK1 proteins co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG–USP4-WT and -C311A mutant (Figure 3a). The association between USP4 and TAK1 were also confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation of overexpressed FLAG–TAK1/TAB1 and HA–USP4 in HEK-293T cells (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

USP4 binds to activated TAK1. (a) Co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG–USP4 and MYC–TAK1 proteins. Expression vectors encoding TAB1 and FLAG–USP4-WT or -C311A mutant were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells with control vectors, or expression vectors encoding MYC–TAK1. MYC–TAK1 in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (b) Co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG–TAK1 and HA–USP4 proteins. Expression vectors encoding TAB1 and FLAG–TAK1 were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells with control vectors, or expression vectors encoding HA–USP4-WT or -C311A mutant, respectively. HA–USP4 in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (c) Co-immunoprecipitation of MYC–USP4 and endogenous TAK1, IKKβ, RIPK1 proteins. HEK-293T cells, transfected with MYC–USP4, treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. MYC–USP4 in the cell lysates from the transfected HEK-293T cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-TAK1, anti-IKKβ and anti-RIPK1 antibodies, respectively. (d) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous USP4 and TAK1, IKKβ, RIPK1 proteins. HeLa cells treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. Endogenous USP4 in the HeLa cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-USP4 antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-TAK1, anti-IKKβ and anti-RIPK1 antibodies, respectively. (e) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous TNFR1 and USP4 proteins. HeLa cells treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. Endogenous TNFR1 in the HeLa cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-TNFR1 antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-USP4, anti-TAK1 and anti-RIPK1 antibodies, respectively

To further determine the molecular interaction of USP4 and TAK1 in TNFα-induced signal transduction, we overexpressed expression vector encoding MYC–USP4 in HEK-293T cells and treated with TNFα for the time points as indicated (Figure 3c). We found that TNFα induced co-immunoprecipitation of MYC–USP4 and TAK1 as well as IKKβ and RIPK1 within 10 min of stimulation (Figure 3c). Consistently, we also found that TNFα induced co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous USP4 and TAK1 as well as KKβ and RIPK1 (Figure 3d). Furthermore, TNFα induced recruitment of USP4, TAK1 and RIPK1 to TNFR1 (Figure 3e). These results suggest that TNFα induces association of USP4 with TAK1.

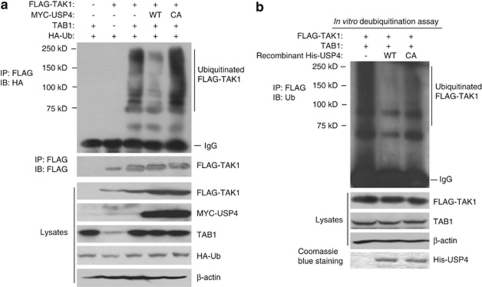

USP4 deubiquitinates TAK1 in vivo and in vitro

The Lys63-linked ubiquitination of TAK1 has an essential role in TNFα-induced NF-κB activation.18 Our results suggest that inhibitory effect of USP4 on the TAK1-induced NF-κB activation could be through its deubiquitinase activity toward TAK1. To test this hypothesis, expression vectors encoding FLAG–TAK1, TAB1 and HA–Ub were cotranfected with vector control or expression vectors encoding MYC–USP4-WT or -C311A mutant into the HEK-293T cells. Cell lysates from the transfected cells were heated in the presence of 1% SDS and diluted with lysis buffer in order to disrupt non-covalent protein–protein interactions. Then FLAG–TAK1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-HA for the detection of the ubiquitinated TAK1. As shown in Figure 4a, overexpression of USP4-WT but not deubiquitinase-deficient C311A mutant abrogated TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination. In contrast, USP4-WT failed to deubiquitinate cIAP1 (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 4.

USP4 deubiquitinates TAK1 in vivo and in vitro. (a) USP4 inhibits TAK1 polyubiquitination. Expression vectors encoding FLAG–TAK1, TAB1 and HA–Ub were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells with control vectors or expression vectors encoding MYC–USP4-WT or -C311A mutant, respectively. The cell lysates from the transfected cells were heated in the presence of 1% SDS and diluted with lysis buffer in order to disrupt non-covalent protein–protein interactions. FLAG–TAK1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibodies to detect the presence of ubiquitinated FLAG–TAK1. (b) Recombinant USP4 deubiquitinates TAK1 in vitro. HEK-293T cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding FLAG–TAK1 and TAB1. Cells were lysed in the lysis buffer only with PMSF as a protease inhibitor. FLAG–TAK1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and co-incubated with purified recombinant His-USP4-WT or -C311A mutant for 2 h in the deubiquitnation buffer before being analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-Ub antibodies. The recombinant His-USP4 proteins used in above assays were detected by Coomassie Blue staining

To further confirm the above result, we analyzed the role of USP4 in the deubiquitination of TAK1 in vitro. In this assay, FLAG–TAK1 proteins from HEK-293T cells with co-overexpression of TAB1 were immunoprecipitated by FLAG antibodies and then co-incubated with recombinant His-USP4-WT or -C311A mutant in the deubiquitination reaction buffer. The ubiquitination level of immunoprecipitated FLAG–TAK1 was found to be significantly decreased by co-incubation with recombinant His-USP4-WT but not -C311A mutant proteins (Figure 4b). These results demonstrate that USP4 acts as a TAK1 deubiquitinase.

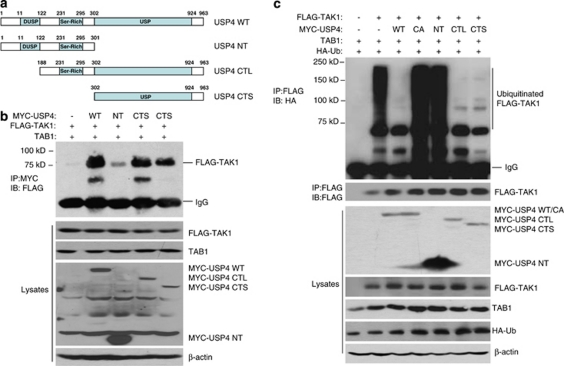

Carboxyl terminal USP domain is required for USP4 to bind to and deubiquitinate TAK1

To further determine the specificity of association of USP4 with TAK1, we cotransfected FLAG–TAK1 and TAB1 expression vectors into HEK-293T cells along with vector control, expression vectors encoding MYC–USP4 full length (USP4-WT), N-terminal regulatory domain (1–301 aa, USP4-NT), N-terminal serine-rich domain and USP domain (188–963 aa, USP4-CTL) or C-terminal USP domain (302–963 aa, USP4-CTS), respectively (Figure 5a). MYC–USP4 full length or deletion mutant proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. In this assay, we found that MYC–USP4-CTL and -CTS but not -NT were able to pull down similar amounts of FLAG–TAK1 compared with MYC–USP4-WT (Figure 5b). Furthermore, consistent with the above binding assay, overexpression of USP4-WT, -CTL and -CTS but not -NT abolished TAK1 and TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination (Figure 5c). These results indicate that carboxyl terminal USP domain is mainly responsible for USP4 to bind to and deubiquitinate TAK1.

Figure 5.

Carboxyl terminal USP domain is required for USP4 to bind to and deubiquitinate TAK1. (a) Schematic representation of USP4-WT and deletion mutants. (b) USP domain of USP4 binds to TAK1. Expression vectors encoding FLAG–TAK1, TAB1 were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells with control vectors or expression vectors encoding MYC–USP4-WT, -NT, -CTL or -CTS mutant, respectively. MYC–USP4 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (c) USP domain of USP4 deubiquitinates TAK1. Expression vectors encoding FLAG–TAK1, TAB1 and HA–Ub were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells with control vectors or expression vectors encoding MYC–USP4-WT, -C311A, -NT, -CTL and -CTS, respectively. FLAG–TAK1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies under denaturing conditions and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibodies to detect the presence of ubiquitinated FLAG–TAK1

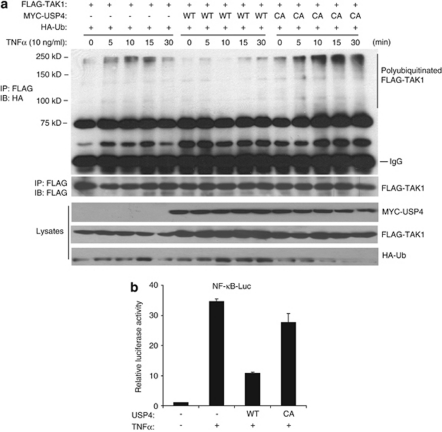

Overexpression of USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination

To determine whether USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination, we overexpressed MYC–USP4-WT and -C311A mutant with HA–Ub in HEK-293T cells and treated with TNFα for the time points indicated. In this assay, we found that TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination was inhibited by USP4-WT but not -C311A mutant (Figure 6a). Consistent with this result, overexpression of USP4-WT but not -C311A mutant inhibited TNFα-induced NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter activity (Figure 6b). Taken together, these results suggest that USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced IKK/NF-κB activation through suppressing TAK1 polyubiquitination.

Figure 6.

Overexpress USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and NF-κB activation. (a) USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination. Expression vectors encoding FLAG–TAK1 and HA–Ub were cotransfected into HEK-293T cells with expression vectors encoding MYC–USP4-WT or -C311A mutant, respectively. Transfected cells were treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. FLAG–TAK1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibodies to detect the presence of ubiquitinated FLAG–TAK1. (b) USP4 inhibits TNFα induced NF-κB activation. Expression vectors encoding USP4-WT or -C311A mutant were transfected along with NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors into HEK-293T cells for 36 h. Cells treated with TNFα (2 ng/ml) for 6 h

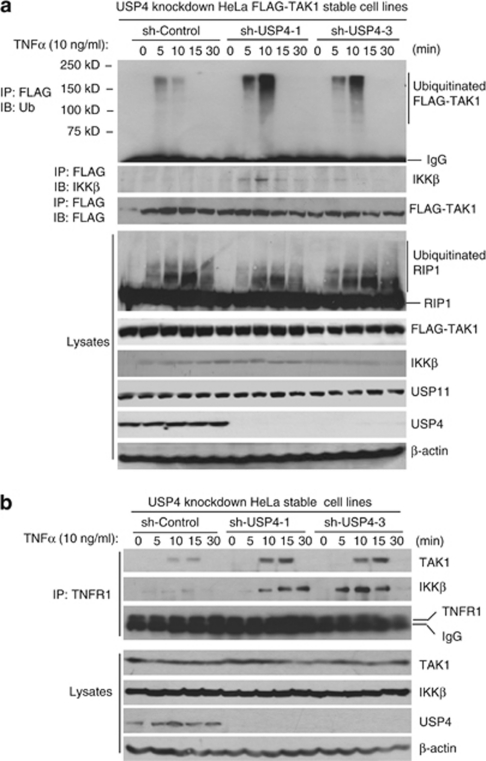

Suppression of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and IKK/NF-κB activation

To determine whether USP4 is involved in the negative regulation of TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination, we generated USP4 stable knockdown HeLa cell lines using a retroviral transduction system (Figure 7a). We then analyzed the effect of USP4 knockdown on the TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination. In this assay, we found that TNFα induced a higher level of TAK1 polyubiquitination and IKKβ recruitment at the early time points in the USP4-knockdown cells compared with the control cells, whereas TNFα-induced RIPK1 polyubiquitination was comparable in both USP4-knockdown cells and control cells (Figure 7a). Furthermore, knockdown of USP4 enhances TNFα-induced recruitment of TAK1 and IKKβ to TNFR1 complex (Figure 7b). This result suggests that USP4 is involved in the downregulation of TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and recruitment of downstream signaling components.

Figure 7.

Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and association of TNFR1 with TAK1 and IKKβ. (a) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances the TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination in the cells. USP4-knockdown HeLa cell lines were first generated after transduction of the HeLa–FLAG–TAK1 cells with the retrovirus expressing small hairpin RNA against USP4 and selected by puromycin. The knockdown effect of USP4 expression was examined by immunoblotting with anti-USP4 antibodies. Then the sh-control and two sh-USP4 HeLa cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. FLAG–TAK1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-IKKβ antibodies or anti-Ub antibodies, respectively. (b) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances the TNFα-induced TNFR1 associated TAK1 and IKKβ. The sh-control and two sh-USP4 HeLa cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. TNFR1 complex in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-TNFR1 antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-TAK1 antibodies or anti-IKKβ antibodies, respectively

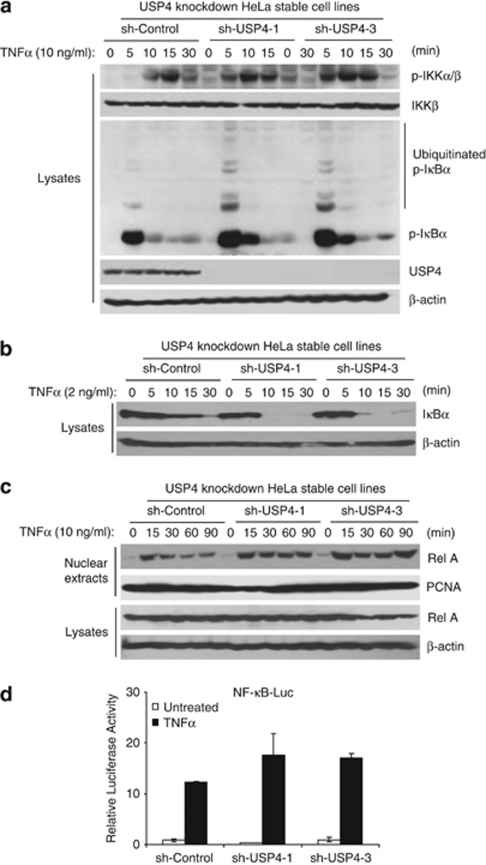

TAK1 mediates TNFα-induced NF-κB activation via IKK phosphorylation and activation.42 Therefore, we further analyzed the effect of USP4 knockdown on the TNFα-induced IKK phosphorylation, IκBα phosphorylation, ubiquitination and degradation. As shown in Figure 8a, TNFα induced an increased level of IKK phosphorylation at the early time points of stimulation, an increased level of IκBα phosphorylation and ubiquitination and rapid IκBα degradation in the USP4-knockdown cells compared with the control cells (Figures 8a and b).

Figure 8.

Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced IKK/NF-κB activation. (a) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances the TNFα-induced IKK phosphorylation, IκBα ubiquitination in the cells. The sh-control and two sh-USP4 HeLa cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated and subsequently immunoblotted with the antibodies indicated. (b) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances the degradation of IκBα. The sh-control and two sh-USP4 HeLa cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (2 ng/ml) for the time points indicated and subsequently immunoblotted with the antibodies indicated. (c) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced RelA translocation. The sh-control and two sh-USP4 HeLa cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. Nuclear extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies indicated. PCNA was used as a loading control for nuclear extracts. (d) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase plasmids were cotransfected into sh-control and two sh-USP4 HeLa cell lines for 36 h, and then the cells were either untreated or treated with TNFα (2 ng/ml) for 6 h

Consistent with the above results, TNFα also induced a higher level of RelA nuclear translocation and the NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter activity in the USP4-knockdown cells compare with the control cells (Figures 8c and d). The purity of nuclear/cytoplasmic extracts is proved by anti-SP1 and anti-HSP90, respectively (Supplementary Figure S4). Taken together, these results suggest that USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced IKK/NF-κB activation through suppressing TAK1 polyubiquitination.

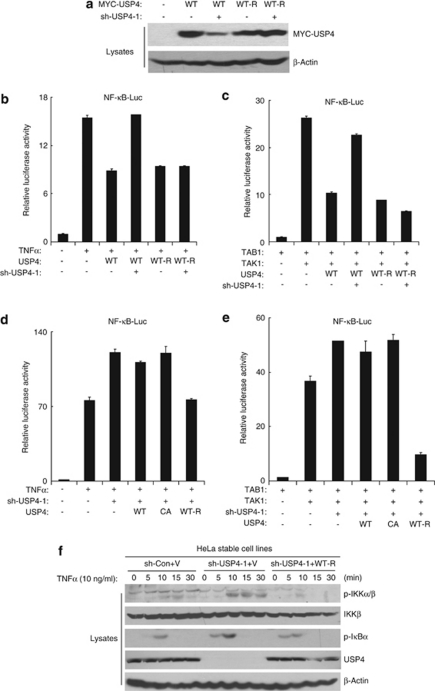

Ectopic expression of sh-RNA-resistant USP4 reverses the effect of USP4 knockdown

To rule out the possible off-target effect of shUSP4, we generated a sh-RNA-resistant USP4 expression vector (USP4-WT-R) to reverse sh-USP4-1-knockdown effect. As shown in Figure 9a, this sh-RNA-resistant USP4-WT-R rescued the knockdown effect of sh-USP4-1 on USP4 expression. Consistently, shUSP4-1 blocked the inhibitory effect of USP4-WT but not USP4-WT-R on TNFα-and TAK1/TAB1-induced NF-κB activation (Figures 9b–e). To further confirm the rescue effect of USP4-WT-R, we stably expressed USP4-WT-R in HeLa USP4 stable knockdown cells. USP4-WT-R rescued the expression of USP4 in the cells (Figure 9f). Also USP4-WT-R rescued the effect of USP4 knockdown on TNFα-induced IKK phosphorylation and IκBα phosphorylation (Figure 9f). These results suggest that specific suppression of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced NF-κB activation.

Figure 9.

The sh-RNA-resistant USP4 reverses the effect of USP4 knockdown. (a) The sh-RNA resistant USP4 cDNA (USP4-WT-R) rescues the expression of USP4 in the presence of sh-USP4. Wild type or a sh-RNA-resistant USP4 cDNA was transfected into 293T cells with empty vector or sh-USP4-1, respectively. Cell lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-MYC antibodies. (b) Sh-USP4-1 reversed the effect of USP4-WT but not USP4-WT-R on TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. (c) Sh-USP4-1 reversed effect of USP4-WT but not USP4-WT-R on TAK1/TAB1-induced NF-κB activation. (d) USP4-WT-R rescued the effect of USP4 knockdown on TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. (e) USP4-WT-R rescued the effect of USP4 knockdown on TAK1/TAB1-induced NF-κB activation. (f) Stable expression of USP4-WT-R rescued the effect of USP4 stable knockdown. HeLa sh-control and sh-USP4-1 stable cells were transfected with vector or USP4-WT-R, respectively. Transfected cells were selected by G418 (3 mg/ml) for 10 days. Established stable cells were either non-treat or treated with TNFα and immunobloted with antibodies indicated

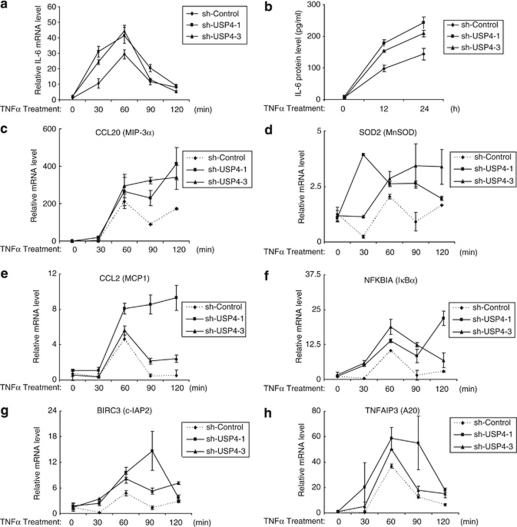

USP4 inhibits TNFα-induced NF-κB-dependent gene expression

NF-κB activation is required for TNFα-induced IL-6 expression. To determine the role of USP4 in the regulation of TNFα-induced IL-6 gene expression, we extracted total RNAs from the control and USP4-knockdown HeLa cell lines treated with TNFα for the time points indicated and performed quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR to examine the effect of USP4 knockdown on TNFα-induced IL-6 expression. TNFα induced a higher level of the IL-6 expression in USP4 knockdown cells compared with the control cells (Figure 10a). Consistent with this, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed a higher IL-6 protein level in USP4-knockdown cells compared with the controls cells (Figure 10b). To further explore the role of USP4 on NF-κB target gene expression, we examined the effect of USP4 knockdown on the expression of other TNFα-induced NF-κB target genes. We found that USP4 knockdown enhanced TNFα-induced expression of MIP3α, MnSoD, MCP-1, IκBα, cIAP2 and A20 in HeLa cells (Figures 10c–h). These results suggest that USP4 downregulates TNFα-induced gene expression via inhibiting TNFα-induced Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination.

Figure 10.

USP4 negatively regulates TNFα-induced gene expression. The sh-control and two sh-USP4 cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for the time points indicated. Total RNAs from these cells were harvested. IL-6 (a), MIP3α (c), MnSOD (d), MCP-1 (e), IκBα (f), cIAP2 (g), A20 (h), transcript levels in the sh-control and two sh-USP4 cell lines were measured using quantitative RT-PCR normalized to GAPDH. The data is presented as the average of three separate experiments with standard deviation. (b) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances TNFα-induced IL-6 production. The sh-control and two sh-USP4 cell lines were either untreated or treated with TNFα (2 ng/ml) for indicated time. The supernatants from these cell cultures were collected and subjected to the human IL-6 ELISA analysis according to the manufacturer's instructions

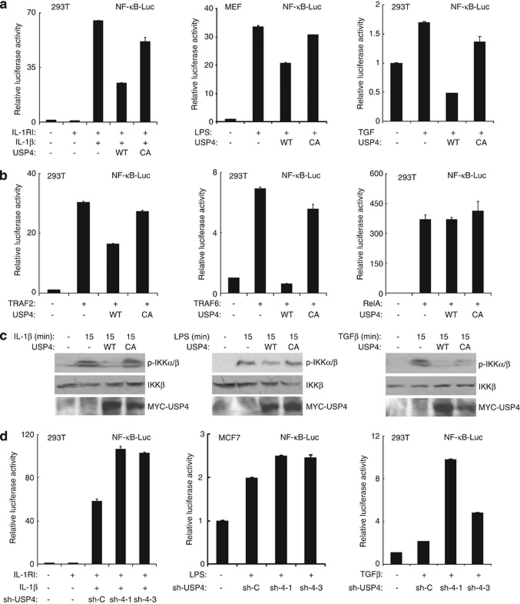

USP4 inhibits IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation

Our above findings suggest that USP4 functions as a TAK1 deubiquitinase to downregulate TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. Furthermore, we also tested the role of USP4 in IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation. We found that overexpression of USP4-WT but not -C311A mutant inhibited IL-1β-, LPS-, and TGFβ-induced NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter activity (Figure 11a). Consistent with this finding, overexpression of USP4-WT but not -C311A mutant inhibited TRAF2- and TRAF6-induced NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter activity (Figure 11b). The inhibitory effect of USP4 on TRAF2 and TRAF6 is specific, because USP4 failed to inhibit RelA-induced NF-κB activation. (Figure 11b). To further confirm the inhibitory effect of USP4 on IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation, we examined the level of IKK phosphorylation induced by IL-1β, LPS and TGFβ, respectively. In this assay, we found that overexpression of USP4-WT but not -C311A mutant inhibited IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced IKK phosphorylation (Figure 11c). Consistent with above results, knockdown of USP4 expression enhanced IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation (Figure 11d).

Figure 11.

USP4 inhibits IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation. (a) USP4 inhibits IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation. Expression vectors encoding USP4-WT or C311A mutant were transfected along with NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter and control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors into indicated cells for 36 h. Cells were treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml), LPS (100 ng/ml) and TGFβ (2 ng/ml) for 6 h. (b) USP4 inhibits TRAF2- and TRAF6- but not RelA-induced NF-κB activation. NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter, control Renilla luciferase reporter vectors and expression vectors encoding USP4-WT or -C311A mutant were transfected along with TRAF2, TRAF6 or RelA, respectively. (c) USP4 inhibits IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced IKK phosphorylation. Empty vector, MYC–USP4-WT or -C311A mutant contructs were transfected into MEF cells for 36 h. Cells were then lysed and cell lysates were immunoblotted with respective antibodies. (d) Knockdown of USP4 expression enhances IL-1β-, LPS- and TGFβ-induced NF-κB activation. NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid and Renilla luciferase plasmid were cotransfected along with sh-control or sh-USP4 plasmids into the indicated cell lines for 36 h, and then the cells were either untreated or treated with IL-1β (2 ng/ml), LPS (100 ng/ml) and TGFβ (2 ng/ml) for 6 h

Discussion

Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 is an essential step in the TNFα-induced IKK/NF-κB activation.18, 34, 35 TNFα rapidly induces TRAF2-mediated TAK1 polyubiquitination at Lys-158. However, the molecular regulation of TAK1 deubiquitination process to attenuate TNFα-induced TAK1 ubiquitination and downstream IKK/NF-κB activation remains to be clearly defined. In this study, we have identified USP4 as a TAK1 deubiquitinase in the TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation. By using a combination of functional genomic screening and molecular approach, we demonstrate that USP4 has a critical role in the attenuation of TNFα-induced Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination as well as downstream IKK/NF-κB activation through inducible association with TAK1 and suppression of Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination. Our study suggests that USP4 serves as a critical Yin-Yang regulatory mechanism to fine-tune TNFα-mediated inflammatory responses by targeting TAK1.

Interestingly, in T cells, CYLD has been implicated in the regulation of TCR-mediated TAK1 ubiqutination.38 However, despite its essential role in spontaneous activation of TAK1 in T cells, the loss of CYLD in Jurkat T cells did not appreciably prolong the IKK activation induced by TNFα.38 In this work, we found that USP4 knockdown enhanced and prolonged TNFα-induced IKK/NF-κB activation in HeLa cells (Figure 8). Furthermore, unlike CYLD, binding of USP4 with TAK1 is induced by TNFα stimulation in the cells (Figures 3c–e). These results indicate that USP4 mainly inhibits inducible TAK1 polyubiquitination and activation, whereas CYLD mainly inhibits basal level of TAK1 polyubiquitination and activation. More interestingly, CYLD-deficient macrophages show normal TNFα-induced NF-κB activation, whereas CYLD-deficient keratinocytes display elevated NF-κB activation.39, 40, 41 These results suggest a cell type-specific function of CYLD in NF-κB activation. In this investigation, we found that CYLD failed to inhibit TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination and NF-κB activation (Figure 1, Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). Together, these results suggest that CYLD may not be a main TAK1 deubiquitinase in TNFα signaling. Future studies are needed to determine the functional difference between USP4 and CYLD in TAK1-mediated NF-κB signaling.

In this study, we found that knockdown of USP4 expression enhanced TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination (Figure 7a). However, TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination peaked at 15 min of stimulation and went down rapidly in USP4-knockdown cells (Figure 7b). It is likely that TNFα induces both Lys63- and Lys48-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination, and Lys48-linked polyubiquitination eventually leads to degradation of TAK1. Furthermore, if TNFα induces Lys48-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination, future studies are needed to identify the lysine residue on TAK1 for mediating Lys48-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination and E3 ligase for catalyzing TAK1 polyubiquitination with Lys48-linkage type.

In our study, we found that USP4 overexpression inhibited TAK1/TAB1 overexpression-induced TAK1 phosphorylation and TAK1-mediated IKK and MAPK activation (Supplementary Figure S1). These results suggest that TAK1 polyubiquitination has an essential role in TAK1 activation and TAK1-mediated IKK and MAPK activation. However, we found that overexpression of PPM1B, a TAK1 phosphatase, inhibited TAK1/TAB1 co-overexpression-induced TAK1 polyubiquitination (Supplementary Figure S5). These results suggest that TAK1 phosphorylation also has an important role in TAK1 polyubiquitination. Therefore, it is highly likely that TAK1 Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and phosphorylation are inter-dependent and both are required for TNFα-induced TAK1 activation.

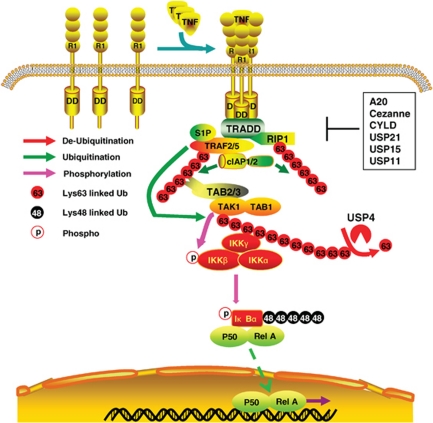

In conclusion, our results provide evidence that TNFα induces association of USP4 with TAK1, which leads to TAK1 deubiquitination in the TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation. In view of the data presented here and previous reports, we propose a working model (Figure 12), in which that TNFα rapidly induces Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitnation and binding of USP4 to TAK1, Lys63-linked TAK1 would be rapidly deubiquitinated by USP4 to attenuate the magnitude of TNFα-induced Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination and TAK1-mediated IKK/NF-κB activation.

Figure 12.

A working model for the role of USP4 in the negative regulation of TNFα-induced TAK1 polyubiquitnation and NF-κB activation. On binding of TNFα, TNFR1 recruits several adaptor proteins including TRAF2, cIAP1/2 and RIPK1 to form a complex that subsequently leads to Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of TRAF2 and RIPK1. Possibly, the Lys63-linked TRAF2 polyubiquitination further recruits and activates TAK1 through binding of the TAK1 regulatory subunits TAB2 and TAB3 to the Lys63-polyubiquitinated chains. After recruitment of TAK1 to the TNFR1 complex, TRAF2 along with its cofactor S1P polyubiquitinate and activates TAK. Then, TNFR1 complex recruits IKK complex via Lys63-polyubiquitinated TAK1 and RIPK1. Activated TAK1 triggers the activation of the IKK, JNK and p38 MAPK, which leads to activation of NF-κB and AP-1. After TNFα stimulation, USP4 binds to the activated TAK1 and deubiquitinates TAK1 to disrupt TAK1/IKKs complex and inhibits TAK1-mediated downstream signaling pathway. Besides USP4, other deubiquitinases (A20, Cezanne, CYLD, USP21, USP15 and USP11) have been suggested to negatively regulate TNFα-induced NF-κB activation

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and transfection

In all, 38 human USPs cDNA clones were purchased from Open Biosystems Company (Huntsville, AL, USA). Full-length cDNA sequence for each USP containing opening reading frame was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter plasmid and pCMV promoter-dependent Renilla luciferase reporter were purchased from Clontech Co. (Mountain View, CA, USA). Mammalian expression vectors for USP4 and TAK1 were constructed by subcloning cDNAs encoding the full-length WT human proteins into the pcDNA3.1 vectors with an N-terminal MYC, FLAG or HA tag. The USP4-C311A and USP4-WT-R expression constructs were generated using site-directed mutagenesis Quikchange kit (Stratgene, CA, USA). The pSUPER-retro vector was used to generate sh-RNA plasmids for USP4. HEK-293T cells, HeLa cells, MCF7 cells and MEF cells were transfected with expression plasmids using FuGene 6, FuGene HD (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse monoclonal anti-MYC (sc-40), anti-RelA (sc-8008), anti-HA (sc-7392), anti-Ub (sc-8017), anti-TNFR1 (sc-8436), anti-SP1 (sc-59), anti-HSP90α/β (sc-7947), anti-PCNA (sc-56) antibodies and protein A-agarose were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Goat polyclonal anti-TAB1 (sc-6052) antibodies were from Santa Cruz. Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-TAK1 (4536S), anti-TAK1 (4505), anti-phospho-IKKα/β (2681), anti-IKKβ (2684), anti-IκBα (9242) antibodies and secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-actin (A2228) and anti-FLAG (F3165) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against RIPK1 were purchased from BD Bioscience (Sparks, MD, USA). Antibodes against USP4 (A300-830A-1) and USP11 (A301-613A-1) were purchased from Bethyl (Montgomery, TX, USA). Recombinant human and mouse TNFα were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). MG132 was from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Cell culture medium was obtained from Invitrogen. Nitrocellulose membrane was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA).

Establishment of the stable USP4-knockdown HeLa cell lines

The pSuper-Control and sh-USP4 retroviral vectors were transfected into the HEK-293T cells with retrovirus packing vector Pegpam 3e and RDF vector using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche) according to manufacturer's instructions. Viral supernatants were collected after 48 and 72 h. HeLa cells were incubated with retroviral supernatant in the presence of 4 μg/ml polybrene. After incubation for 48 h, stable cell lines were established after 10 days of puromycin (2 μg/ml) selection and knockdown of the target gene was confirmed by western blot. Established USP4-knockdown cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 expression vectors and selected by G418 (3 mg/ml) for 10 days for stable expression.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

To determine the interaction of the proteins, co-immunoprecipitation and western blots were performed as following. Targeted cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS on ice, then whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysing cells in lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.7), 135 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM benzamidine, 20 mM disodium p-nitrophenylphosphate, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail A and B). After collecting the lysate by 15 000 × g centrifuge for 15 min at 4 °C, primary antibodies were added to the supernatant and incubated with rotation for 3 h at 4 °C. After adding a protein A-agarose bead suspension, the mixture was further incubated with rotation for 3 h at 4 °C. The precipitates were washed three times using pre-cold washing buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.7), 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.05% Triton X-100), then the beads were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. The immunoprecipitates or the whole cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed with appropriate antibodies. The IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were used as the secondary antibodies. The proteins were detected using the ECL-Plus Western blotting detection system (GE Health Care, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Luciferase reporter assay

Targeted cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells per well and cultured overnight in six-well plates. The cells were transfected with indicated plasmids, together with NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase construct and Renilla luciferase construct, which was used to normalize firefly luciferase activity. The control plasmids were added to sustain equal amounts of total DNA. At 36 h after transfection, 2 ng/ml of TNFα was added to the media. The cells were incubated for another 6 h before they were collected for dual specific luciferase reporter gene assays. Luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's protocol. The relative luciferase activity was calculated by dividing the firefly luciferase activity by the Renilla luciferase activity. Data represent three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

RT and quantitative RT-PCR

Cells were collected using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and RNA extracted according to manufacturer's protocol. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed on 1 ug of RNA using SuperScript III Gene Expression Tools and oligo dT (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative Real-time PCR was performed using specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) and SYBR Green ROX Mix (ABgene , Epsom, UK), analyzed using an Applied Biosystems 7300 real time PCR system. Data were normalized to housekeeping GAPDH gene and the relative abundance of transcripts was calculated by the Ct models.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

HeLa cell lines with stable knockdown of USP4 and control cells were plated in 12-well plates. Cells were either left untreated or treated with 2 ng/ml of TNFα and incubated for different time points. Medium was then taken and cleared of cells and debris by centrifugation and assayed using the OptEIA Mouse IL-6 ELISA kit (BD Biosciences) as the manufacturer's instruction. Assays were performed in triplicate for three independent times.

In vitro deubiquitination assay

His-USP4-WT, His-USP4-C311A proteins were expressed in BL-21 Escherichia coli. After the induction with 0.5 M isopropyl-β--thiogalactopyranoside at 30 °C for 4 h, bacteria were pelleted and lysed with extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 50 mg/ml lysozyme, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin and 1 mM PMSF) for 45 min on ice. The bacteria were sonicated at 4 °C in 1% Sarcosyl (Sigma), and then 1% Triton X-100, 5 μg/ml DNase and 5 μg/ml RNase were added. The lysates were centrifuged at 15 000 × g for 15 min in a Sorvall SS34 rotor and the supernatants containing His fusion protein were collected. A total of 150 ul His-SelectTM Nickel Affinity gel (Sigma) was incubated with each bacterial lysate supernatant at 4 °C overnight. The beads were washed three times in extraction buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, one time in extraction buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Proteins were eluted in elution buffer (250 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 300 mM NaCl) and dialyzed in dialyzing buffer (20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 150 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol). The protein concentrations were determined with a Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) and proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

To perform in vitro deubiquitination assay, FLAG–TAK1 expression vectors were transfected into HEK-293T cells with the vectors encoding TAB1. FLAG–TAK1 proteins in the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and co-incubated with purified recombinant His-USP4-WT or -C311A mutant for 2 h at 30 °C in a final volume of 20 μl of deubiquitnation buffer (30 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 5 mM DTT and 2 mM ATP). The reaction mixtures were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-Ub antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Dr. Lin Xin for providing TAB1 and TAK1 expression constructs. This work was supported in part by the grants from the NIH/NCI 1R21CA106513-01A2 (to JY), the American Cancer Society grant RSG-06-070-01-TBE (to JY), the Virginia and LE Simmons Family Foundation Collaborative Research Fund (to JY), and DLDCC Pilot study from NIH/NCI grant 5P30CA125123-03 (to JY).

Glossary

- TAK1

transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

- USP4

ubiquitin-specific peptidase 4

- IκB

inhibitor κB

- TNFR1

TNF receptor 1

- TRAF2

TNF-receptor associated factor 2

- cIAP1/2

cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 1/2

- RIPK1

receptor interacting protein kinase 1

- IKK

IκB kinase

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- DUB

deubiquitinating enzyme

- Ub

ubiquitin

- USP

ubiquitin-specific peptidase

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by J Silke

Supplementary Material

References

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud V, Karin M. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and its relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:372–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Baldwin AS., Jr The I kappa B proteins: multifunctional regulators of Rel/NF-kappa B transcription factors. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2064–2070. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AS., Jr The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109:81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe M, Wong SC, Henzel WJ, Goeddel DV. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1994;78:681–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H, Huang J, Shu HB, Baichwal V, Goeddel DV. TNF-dependent recruitment of the protein kinase RIP to the TNF receptor-1 signaling complex. Immunity. 1996;4:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince JE, Pantaki D, Feltham R, Mace PD, Cordier SM, Schmukle AC, et al. TRAF2 must bind to cellular inhibitors of apoptosis for tumor necrosis factor (tnf) to efficiently activate nf-{kappa}b and to prevent tnf-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35906–35915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ea CK, Deng L, Xia ZP, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol Cell. 2006;22:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Wang L, Dorf ME. PKC phosphorylation of TRAF2 mediates IKKalpha/beta recruitment and K63-linked polyubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2009;33:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Mrad RL, Plenchette S, Simard C, Enwere E, et al. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate TNFalpha-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11778–11783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand MJ, Milutinovic S, Dickson KM, Ho WC, Boudreault A, Durkin J, et al. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2008;30:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Blackwell K, Shi Z, Habelhah H. The RING domain of TRAF2 plays an essential role in the inhibition of TNFalpha-induced cell death but not in the activation of NF-kappaB. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Q, Lamothe B, Darnay BG, Wu H. Structural basis for the lack of E2 interaction in the RING domain of TRAF2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10558–10567. doi: 10.1021/bi901462e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez SE, Harikumar KB, Hait NC, Allegood J, Strub GM, Kim EY, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature. 2010;465:1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/nature09128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Yu Y, Shi Y, Sun W, Xie M, Ge N, et al. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at lysine 158 is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-1beta-induced IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5347–5360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, et al. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell. 2000;103:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaesu G, Kishida S, Hiyama A, Yamaguchi K, Shibuya H, Irie K, et al. TAB2, a novel adaptor protein, mediates activation of TAK1 MAPKKK by linking TAK1 to TRAF6 in the IL-1 signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell. 2000;5:649–658. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Qian Y, Matsumoto K, Li X. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor-associated kinase-dependent IL-1-induced signaling complexes phosphorylate TAK1 and TAB2 at the plasma membrane and activate TAK1 in the cytosol. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7158–7167. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7158-7167.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. 2001;412:346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Kobayashi M, Blonska M, You Y, Lin X. Ubiquitination of RIP is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13636–13643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600620200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JH, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, et al. TAK1, but not TAB1 or TAB2, plays an essential role in multiple signaling pathways in vivo. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2668–2681. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WW, Gentle IE, Nachbur U, Anderton H, Vaux DL, Silke J. RIPK1 is not essential for TNFR1-induced activation of NF-kappaB. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:482–487. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-I kappaB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, et al. Essential function for the kinase TAK1 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1087–1095. doi: 10.1038/ni1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya H, Yamaguchi K, Shirakabe K, Tonegawa A, Gotoh Y, Ueno N, et al. TAB1: an activator of the TAK1 MAPKKK in TGF-beta signal transduction. Science. 1996;272:1179–1182. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner SH, Kular G, Peggie M, Shepherd S, Schuttelkopf AW, Cohen P, et al. TAK1-binding protein 1 is a pseudophosphatase. Biochem J. 2006;399:427–434. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prickett TD, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Broglie P, Muratore-Schroeder TL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, et al. TAB4 stimulates TAK1-TAB1 phosphorylation and binds polyubiquitin to direct signaling to NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19245–19254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800943200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino A, Thakur N, Grimsby S, Marcusson A, von Bulow V, Schuster N, et al. The type I TGF-beta receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1199–1207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao R, Fan Y, Mou Y, Zhang H, Fu S, Yang J. TAK1 lysine 158 is required for TGF-beta-induced TRAF6-mediated Smad-independent IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. Cell Signal. 2010;23:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Gohda J, Kanayama A, Miyamoto Y, Sakurai H, Yamamoto M, et al. Two mechanistically and temporally distinct NF-kappaB activation pathways in IL-1 signaling. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra66. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Yu Y, Mao R, Zhang H, Yang J. TAK1 Lys-158 but not Lys-209 is required for IL-1beta-induced Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination and IKK/NF-kappaB activation. Cell Signal. 2010;23:660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, et al. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–765. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiley WW, Jin W, Lee AJ, Wright A, Wu X, Tewalt EF, et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD negatively regulates the ubiquitin-dependent kinase Tak1 and prevents abnormal T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1475–1485. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Stirling B, Temmerman ST, Ma CA, Fuss IJ, Derry JM, et al. Impaired regulation of NF-kappaB and increased susceptibility to colitis-associated tumorigenesis in CYLD-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3042–3049. doi: 10.1172/JCI28746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiley WW, Zhang M, Jin W, Losiewicz M, Donohue KB, Norbury CC, et al. Regulation of T cell development by the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:411–417. doi: 10.1038/ni1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoumi R, Chmielarska K, Hennecke K, Pfeifer A, Fassler R. Cyld inhibits tumor cell proliferation by blocking Bcl-3-dependent NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2006;125:665–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IkappaB kinase activity through IKKbeta subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.