Abstract

Iron homeostasis is highly regulated in organisms across evolutionary time scale as iron is essential for various cellular processes. In a computational screen, we identified the Yap/bZIP domain family in Candida clade genomes. Cap2/Hap43 is essential for C. albicans growth under iron-deprivation conditions and for virulence in mouse. Cap2 has an amino-terminal bipartite domain comprising a fungal-specific Hap4-like domain and a bZIP domain. Our mutational analyses showed that both the bZIP and Hap4-like domains perform critical and independent functions for growth under iron-deprivation conditions. Transcriptome analysis conducted under iron-deprivation conditions identified about 16% of the C. albicans ORFs that were differentially regulated in a Cap2-dependent manner. Microarray data also suggested that Cap2 is required to mobilize iron through multiple mechanisms; chiefly by activation of genes in three iron uptake pathways and repression of iron utilizing and iron storage genes. The expression of HAP2, HAP32, and HAP5, core components of the HAP regulatory complex was induced in a Cap2-dependent manner indicating a feed-forward loop. In a feed-back loop, Cap2 repressed the expression of Sfu1, a negative regulator of iron uptake genes. Cap2 was coimmunoprecipitated with Hap5 from cell extracts prepared from iron-deprivation conditions indicating an in vivo association. ChIP assays demonstrated Hap32-dependent recruitment of Hap5 to the promoters of FRP1 (Cap2-induced) and ACO1 (Cap2-repressed). Together our data indicates that the Cap2-HAP complex functions both as a positive and a negative regulator to maintain iron homeostasis in C. albicans.

Keywords: Fungi, Iron, Transcription Factors, Transcription Regulation, Transcription Repressor, Iron Homeostasis

Introduction

The generality and evolutionary conservation of transcriptional regulatory networks is a vital issue that can now be addressed with the availability of a multitude of genome sequences. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been a workhorse for understanding major transcriptional regulatory paradigms including cellular responses to various stress. Several recent examples, however, showed a divergence of transcriptional regulatory networks between S. cerevisiae and other fungal genomes (1, 2). Thus the lessons from the S. cerevisiae transcriptional programs would have to be re-evaluated as new genomes are sequenced and annotated.

Iron homeostasis is a highly regulated process as iron is essential for various cellular processes, but becomes toxic at high levels (3, 4). The regulation of iron homeostasis in the yeast S. cerevisiae occurs both at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (5, 6). The S. cerevisiae transcriptional activator Aft1 and its paralog Aft2 regulate expression of genes encoding reductive iron assimilatory system FRE1–FRE6, FET3, FTR1, iron-siderophore importers ARN1–ARN4, and the low-affinity transporter encoded by FET4 during iron starvation (7, 8). Aft1 expression is constitutive and its nuclear localization occurs upon iron depletion (9). Because iron-dependent deactivation of Aft1/Aft2 is abrogated in cells defective for mitochondrial iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster biogenesis, it was concluded that iron sensing by Aft1/Aft2 is dependent on mitochondrial Fe-S export (10). During iron deprivation, Aft1/Aft2 also induces the expression of CTH2, encoding a zinc-finger domain protein, which in turn binds to the AU-rich elements in the mRNAs of iron-utilizing genes and targets them for degradation (11).

Although a functional homolog of Aft1/Aft2 has not been found in fungi other than Saccharomyces (12), the AFT2-like gene in Candida albicans, although not required for ferric reductase activity under iron deprivation conditions, was required for optimal ferric reductase activity at high and low pH conditions (13). A GATA family transcription factor Sfu1 in C. albicans (14), or its orthologs in other organisms, function as a negative regulator of iron uptake genes in high iron medium (reviewed in Refs. 15 and 16). In addition, the regulation of iron homeostasis in fungal genomes, including C. albicans, is dependent on the HAP regulatory complex (17–21). In S. cerevisiae, the HAP complex components Hap2, Hap3, and Hap5, are homologous to mammalian NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC subunits, respectively, of the trimeric CCAAT box binding regulator NF-Y (22). Although the trimeric complex is sufficient to regulate gene expression in mammalian cells, the Hap4 regulatory subunit associates with Hap2/Hap3/Hap5 in S. cerevisiae to form the HAP complex, a transcriptional activator of respiratory pathway genes (23, 24). In S. cerevisiae, however, the HAP complex does not function in iron homeostasis (25).

Barring Saccharomyces genomes, other fungal genomes studied (17, 21, 26, 27) lacked a full-length Hap4 protein. Instead, HapX from A. nidulans (17) and Php4 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe (18) contained the short 17-amino acid HAP4-like (HAP4L) domain. These proteins have been shown to regulate iron homeostasis by a mechanism involving transcriptional repression of iron utilizing genes (reviewed in Refs. 16 and 28). The S. cerevisiae Hap5 protein contains a conserved Hap4 interaction domain, required for interaction with Hap4 (29). The interaction of Hansenula polymorpha Hap4a and Hap4b proteins with Hap5 has also been demonstrated using the yeast two-hybrid assay (21). Furthermore, HapX interaction has also been uncovered with the HAP2-HAP3-HAP5 complex using bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (17). Together these reports showed that HAP4L family proteins interact with the entire HAP complex, in a manner dependent on the HAP4L domain in Hap4, and the Hap4 interaction domain in Hap5.

C. albicans is an opportunistic human fungal pathogen that causes Candidiasis. Because iron is sequestered by ferritin, transferrin, and lactoferrin, the mammalian host is an iron-poor environment. Moreover, C. albicans also competes with the host microbiome in biofilms and the gut for the limited iron supply (30). Thus, the ability of C. albicans to acquire iron becomes critical for its survival as well as for pathogenesis (31). As in S. cerevisiae, there are multiple pathways for iron uptake in C. albicans as well, including high-affinity uptake, siderophore uptake, and heme uptake (32–35). Previous reports showed that FTR1 is required for C. albicans pathogenesis (33).

The C. albicans genome contains genes encoding siderophore transporter, four iron permeases, five multicopper oxidases, a family of 17 putative ferric reductases, as well as heme uptake components indicating the multiplicity of iron acquisition pathways (28, 32). C. albicans can also acquire iron from ferritin in a manner dependent on the Als3 protein (36), but, iron acquisition through Als3/ferritin does not exist in S. cerevisiae. Thus a complete understanding of the regulatory network governing iron homeostasis is required to assess its full impact on C. albicans pathogenesis. In this study, we demonstrate that the Cap2-HAP complex is a critical transcriptional regulator that has dual but contrasting functions to maintain iron homeostasis in C. albicans.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Media and Growth Conditions

C. albicans strains were cultured in synthetic complete limited iron medium (SC-LIM)3 containing 1.7 g/liter of yeast nitrogen base without iron and copper (MP Biomedicals LLC), 5 g/liter of ammonium sulfate, 20 g/liter of dextrose, complete amino acid supplements, and 2.5 μm CuSO4. Iron-depleted medium contained SC-LIM plus BPS (Sigma) and iron-replete medium contained SC-LIM plus FeCl3 (100 μm) alone or FeCl3 and BPS together.

Strains and Plasmids

Plasmids and C. albicans strains used in this study are listed under supplemental Tables S1 and S2. The C. albicans strain SN152 (37), a kind gift from Suzanne Noble and A. D. Johnson, was used as the parental strain for all strains derived in this study. The list of oligonucleotides is provided under supplemental Table S3. Details of strain and plasmid constructions are available on request.

The cap2Δ mutant strains RPC51 and RPC75 were constructed in C. albicans strain SN152 background using the PCR fusion strategy (37) by electroporation (38). Correct integration was confirmed by PCR, and the absence of the CAP2 ORF in strain RPC75 was confirmed by PCR.

Plasmid pRC20 was constructed by replacing the CaURA3 in CIp10 (39) with the C.d.ARG4 gene (37), and contained the CAP2 ORF flanked by 631 bp upstream and 323 bp downstream regions. The 2859-bp insert was sequenced completely by primer walking with oligonucleotides ONC213, ONC10, ONC56, ONC57, ONC58, and ONC81. The sequencing data revealed that the clone contained the CAP2 allele orf19.8289 sequence, and showed eight nucleotide differences compared with the CAP2/orf19.681 sequence in CGD (Assembly 19). The cloned gene contained additional changes A774G, C1279T, and T1848C; of the three, the first and third resulted in silent mutations, whereas C1279T led to the Pro to Ser change. These nucleotide differences in pRC20 did not cause a measurable reduction in CAP2 function, as judged by growth of strain RPC192 in BPS-containing medium. Isogenic wild-type strains RPC132 (His+ Leu+) and RPC206 (His+ Arg+) were constructed by transforming C.d.ARG4 (37) and C.d.HIS1 (40) DNA fragments.

The cap2 mutant plasmids bearing amino acid substitutions in the bZIP domain (cap2–1; pRC62) or a deletion of the HAP4L domain (cap2–2; pRC53) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using primers ONC230/ONC231 (cap2–1 allele) or ONC214/ONC215 (cap2-2 allele) and pRC20 as template. The coding region in the resultant plasmids were sequenced completely and all mutagenic changes were confirmed. Plasmids pRC62 and pRC53 were linearized with Stu1 and integrated at the RPS1 locus in strain RPC75 to create strains RPC309 (cap2–1) and RPC286 (cap2–2). Because the bZIP domain mutation could not be discerned by the PCR product size alone, we used primers ONC101/ONC315 or ONC101/ONC316 that specifically amplify the wild-type and bZIP mutant sequences, respectively.

Plasmids pNA7, pNA17, and pNA13 bearing the CAP2, cap2–1, and cap2–2 alleles, respectively, contained the caSAT1 gene (38), in lieu of the C.d.ARG4 marker gene in plasmids pRC20, pRC62, and pRC53. Strains RPC506 (cap2–2 CAP2) and RPC517 (cap2–2 cap2–1) were created by integrating DraIII-cut pNA7 and pNA17, respectively, into strain RPC286. Strains RPC511 (cap2–1 CAP2) and RPC521 (cap2–1 cap2–2) were similarly created by integrating DraIII-cut pNA7 and pNA13 into strain RPC326. The control strain RPC510 was constructed by integrating pNA7 into RPC278, which was generated by integrating CIp10-C.d.ARG4 into strain RPC75. The presence of the various CAP2 alleles was confirmed by diagnostic PCR using primers ONC101/ONC315 or ONC101/ONC316 (data not shown).

C. albicans hap32Δ mutant strain RPC 431 was constructed using the split-marker strategy (41). Strains RPC445 (hap31Δ/Δ) and RPC434 (sfu1Δ/Δ) were produced in SN152 by sequentially introducing PCR amplicons generated using locus-specific long oligonucleotides and pFA-CdHIS1 and pFA-CmLEU2 (42) as templates. The strain RPC449 (hap31Δ/Δ hap32Δ/Δ) was constructed in the RPC445 background. C. albicans hap2Δ/Δ and hap5Δ/Δ mutant strains (20) were obtained from Fungal Genetics Stock Center (43).

The cap2Δ/Δ mutation was constructed in strain RPC434 (sfu1Δ/Δ) using pRC11, which contained the cap2Δ::SAT1 flipper cassette flanked by CAP2 upstream (−432 to +32) and downstream (+1872 to +2233) sequences. The cap2Δ::SAT1 flipper cassette in pRC11 was excised by KpnI-SacI digestion and transformed by electroporation. The various strains described above were confirmed using locus-specific and ORF-specific PCR primers.

TAP tag plasmids Ip21 and Ip22 contained C.m.LEU2 and C.d.HIS1 marker genes, respectively (37), and the ACT1 terminator region (44) and the BamHI-EcoRV TAP tag fragment from pPK335 (45). The SFU1-TAP tagging cassettes were generated by PCR using primers ONC257/ONC258 and Ip21 and Ip22 as template. The targeted integration of the tagging cassettes was confirmed by diagnostic PCR and the expression of Sfu1-TAP was confirmed by Western blot using rabbit polyclonal anti-TAP antibody (Open Biosystems). The HAP5-TAP strains RPC453 (wild-type) and RPC562 (hap32Δ) were constructed and verified using the same strategies as mentioned above for the SFU1-TAP.

The HIS6-FLAG3-tagged HAP5 was constructed from plasmid pSH26-5 (caSAT1-FLIP cassette) and split-marker strategy. The HAP5 sequence was PCR amplified as the up-split (∼2640 bp) and down-split (∼3100 bp) fragments using primers ONC460/ONC140 and ONC141/ONC461. The up-split and down-split amplicons, bearing ∼1 kb overlap, contained 60-bp homology to either side of the HAP5 stop codon. The amplicons were transformed into SN152 and correct integration of the tagging cassette in RPC552 was confirmed by diagnostic PCR and expression of tagged Hap5 was confirmed by Western blot using affinity purified mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma).

Production of Anti-Cap2 Polyclonal Antibody

Plasmid Ip9 contained truncated CAP2 (+1 to +542 with respect to ATG) in pET28b+ vector (Novagen). The recombinant Cap2-His6 protein was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbit. The anti-Cap2 antibody was affinity purified using recombinant Cap2.

Virulence Assay

C. albicans strains RPC206, RPC278, and RPC192 were grown overnight in YEPD, inoculated into fresh YEPD medium to a starting A600 of 0.5, and grown for 4 h at 30 °C. The cells were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in sterile normal saline, cells were counted, and ∼2 × 106 cells in 100 μl were injected into the lateral tail vein of 8–10-week-old BALB/c mice with 5–7 mice per group. The mice were fed water and food ad libitum and monitored daily for vital signs and activity. When mice appeared moribund (hunched posture and minimal motor activity), they were euthanized, organs were dissected, and the fungal burden in kidney and brain was examined. The mice were handled humanely as per protocols for animal experiments approved by the Jawaharlal Nehru University Institutional Animal Ethics Committee.

Immunoblotting

C. albicans strains were grown overnight in SC-LIM medium and inoculated to a starting A600 of 0.25 (CAP2) or 0.5 (cap2Δ) into fresh SC-LIM medium with BPS alone or with BPS plus FeCl3 or FeCl3 alone. Cultures were grown at 30 °C for different time periods and harvested, pellets were resuspended in 300 μl of extraction buffer (46) and cells were lysed by vortexing. The lysate was spun at 18,500 × g at 4 °C for 15 min, the supernatant was centrifuged again and the cleared lysate collected. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) using BSA as standard. About 60 μg of whole cell extract was resolved by 6–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to HybondTM-ECLTM nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). The blot was probed with primary antibody, followed by a secondary HRP-conjugated antibody and detected using ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare).

RNA Extraction and RT-PCR Analysis

C. albicans strains were grown as described under “Immunoblotting.” Cells equivalent to A600 ∼ 10 were harvested rapidly by filtration and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen vapors. Total RNA was isolated using hot phenol method (47) and the concentration was determined using Nanodrop spectrophotometer.

For all RT-PCR experiments, total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen) to remove any residual DNA. About 150 ng of DNase I-treated RNA was used for single-stranded cDNA synthesis in 7.5 μl of reaction mixture using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). For semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis, 1.0 μl of 10-fold dilution of cDNA reaction mixture was used as a template using Taq DNA polymerase. SCR1 RNA, an RNA polymerase III transcript (48), was used as endogenous control. Real-time qRT-PCR was carried out in Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-time PCR system, where each 10 μl of reaction mixture contained 4 μl of 500-fold diluted cDNA, 0.1 μm gene-specific primers and SYBR Green PCR master mixture (Applied Biosystems). The comparative CT method (2−ΔΔCT) was used to determine the relative gene expression (49). Control reactions without reverse transcriptase were carried out for each cDNA preparation and ascertained that no amplification was obtained as judged by high CT (>39) values and gel analysis.

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was isolated by the hot phenol method from control SN152 (CAP2) and RPC75 (cap2Δ) strains grown in SC-LIM medium plus 100 μm BPS for 5 h. C. albicans microarrays (50) were obtained from the Washington University Microarray Core facility. All steps in microarray analysis including image quantitation and data normalization steps are detailed in GEO entry GSE 28429. The microarray hybridization was repeated with two independent sets of RNA preparations. The data were filtered for good spots in GenePix Pro 6.0 as described before (51), data were normalized, and the log2 ratio (CAP2/cap2Δ) for each spot obtained. The data for triplicate spots (with log2 ratio <1 S.D.) for each gene in each array was merged and used for further statistical analysis. Significance analysis of microarrays (52) was performed as described previously (53), with the exception of 1000 permutations to get differentially expressed genes with low false discovery rate. Gene Ontology analysis of the differentially expressed genes was carried out using Bingo 2.42 (54) in Cytoscape version 2.7 visualization and analysis software (55) with CGD Candida GO annotation (downloaded August 10, 2010) and overrepresented biological processes with high statistical significance (p value ≤ 0.05) obtained using a hypergeometric test and Benjamini and Hochberg FDR correction. Heat map of the differentially expressed genes was constructed using the R Bioconductor package running under Linux. The microarray data has been deposited under GEO entry GSE 28429.

Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

C. albicans strains SN152 and RPC552 were cultivated in BPS containing medium at 30 °C for 5 h, and whole cell extracts were prepared as described under “Immunoblotting.” About 1.2 mg each of the whole cell extracts were mixed with 10 μl of anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma, A-2220), and incubated on a rotating platform at 4 °C for 4 h. After IP, beads were collected, washed, and resuspended in 25 μl of 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The entire immunoprecipitated sample and 100 μg of input protein extracts were separated in a gradient 6–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to Hybond-ECLTM nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare), and immunoblotting was performed. The following antibodies were used to probe the immunoblots: affinity purified monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (1:1000; Sigma), affinity purified polyclonal anti-Cap2 antibody (1:2500), and as control anti-yeast glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (1:500; Sigma).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

HAP5-TAP strains RPC453 (HAP32/HAP32) and RPC562 (hap32Δ/hap32Δ) were grown in SC-LIM containing 0.1 mm BPS or 0.1 mm BPS plus iron for 5 h at 30 °C to an A600 of 0.8–1.0. Formaldehyde (1% v/v) was added to the cultures and cross-linked for 20 min at 30 °C and cells were spheroplasted in a buffer containing 1 m sorbitol, 50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.03 mg/ml of zymolyase (ICN). Spheroplasts were resuspended in 50 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 140 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS plus protease inhibitors (1 mm PMSF and 1 mg/ml each of leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin) and sheared by sonication using Bioruptor (model UCD 300, Diagenode), at high power for 30 cycles (30 s on and 30 s off). The average chromatin size obtained was ∼0.25 kb. About 25 μl of pre-blocked IgG-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) was used for immunoprecipitation from the sheared chromatin extract equivalent to ∼20 A600 cells and the ChIP assay was carried out essentially as described previously (56). Whole cell extracts (Input) and the IP eluate were treated for reversal of cross-links, DNA purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, and analyzed by qPCR. ChIP-qPCR data analysis was done as described previously (49).

RESULTS

C. albicans Cap2 Is a HAP4L-bZIP Bipartite Domain Protein

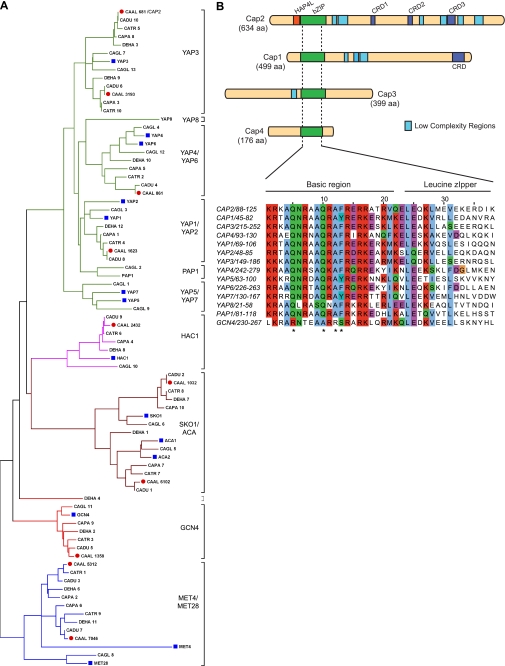

We identified the complete repertoire of bZIP domain containing sequences from S. cerevisiae, Candida glabrata, and 10 Candida clade species (Fig. 1A, and supplemental Fig. S1). The 124 bZIP domain sequences identified were used to construct multiple sequence alignment (supplemental Fig. S1) of a minimal region of 38 amino acids and a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Fig. 1A). The phylogenetic tree revealed clustering of the bZIP domains into distinct clusters occupied by the S. cerevisiae Yap1–Yap8, Hac1, Sko1/Aca1–2, Gcn4, and Met4–Met28-proteins, respectively (Fig. 1A). Analysis of the tree revealed that the Candida clade genomes had four Yap/bZIP proteins named CAP1 through CAP4, compared with the eight in S. cerevisiae and C. glabrata (Fig. 1B). The Yap/bZIP domain of each of the four C. albicans Cap proteins contained the four Yap-specific residues described previously (57), and are indicated in Fig. 1B. CAP1 has been previously characterized as a functional ortholog of the S. cerevisiae YAP1 gene (58), and CAP3/FCR3 upon overexpression conferred fluconazole resistance to the S. cerevisiae pdr1Δpdr3Δ mutant (59, 60). However, thus far no function has been attributed to the CAP4 gene.

FIGURE 1.

Bioinformatics of Candida clade bZIP domain sequences. A, comparative phylogeny of bZIP domains from Candida and Saccharomyces clade genomes. Neighbor-joining tree (1000 bootstrap replicates) was constructed based on the multiple sequence alignment of Candida clade, S. cerevisiae, and C. glabrata bZIP domains using MEGA4 software. The known bZIP subfamily proteins from S. cerevisiae (blue box) are indicated by their gene names as given in the Saccharomyces Genome Database. The putative orthologs from C. albicans (red circle) and other organisms are indicated. The unique identifiers of proteins/fungal species are provided under supplemental Table S4A. B, structural features of C. albicans Cap proteins. Top, schematic diagram of the predicted domains in the CAP proteins: HAP4L domain, bZIP domain, cysteine-rich domains (CRD-1, -2, and -3) and the low complexity regions (mostly serine-rich) identified using SMART and Motif Scan software. Bottom, multiple sequence alignment of the bZIP domain sequence from Cap1–4, Yap1–8, S. pombe Pap1, and S. cerevisiae Gcn4. Characteristic Yap-specific residues found in all Yap-like proteins but not in Gcn4 are indicated (*).

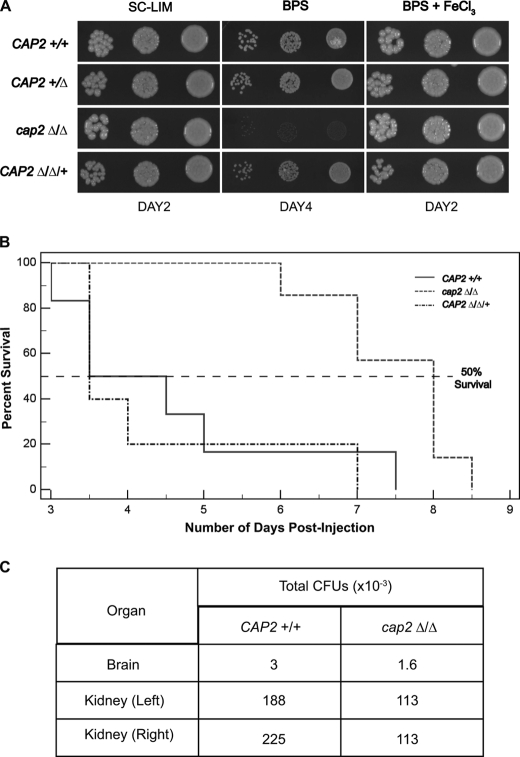

Our mutational analyses showed that the CAP2/HAP43 gene was required for growth of C. albicans under iron deprivation conditions (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the cap2Δ mutant showed delayed virulence in a mouse model of C. albicans virulence (Fig. 2B). Analysis of the fungal burden from infected mice showed at least 50% recovery of cap2Δ cells as compared with wild-type from the kidney and brain as determined by colony forming units (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of cap2Δ mutation on C. albicans growth and virulence. A, the growth phenotype of cap2Δ/Δ mutant in iron-deplete medium. C. albicans strains SN152 (CAP2+/+), RPC51 (cap2+/Δ), RPC75 (cap2Δ/Δ), and RPC192 (cap2Δ/Δ/+) were grown overnight in SC-LIM liquid medium at 30 °C. About 5 μl each from 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 A600 equivalent cell suspensions were spotted onto SC-LIM, SC-LIM + 50 μm BPS, or SC-LIM + 50 μm BPS plus 100 μm FeCl3 plates and incubated at 30 °C. B, the cap2Δ/Δ mutant showed delayed virulence in mouse. Strains RPY206 (CAP2+/+), RPC278 (cap2Δ/Δ), and RPC192 (cap2Δ/Δ/+) were injected into BALB/c mice (n = 5–7) and the percentage of surviving mice was plotted for each group. Kaplan-Meier test yielded a p value 0.004 between wild-type and cap2Δ/Δ mutant. C, the fungal burden in the brain and kidneys of the dead or moribund mice were determined by plating aliquots of appropriate dilutions of tissue homogenates on YPD containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and gentamycin (0.8 mg/ml). The recovered colonies were tested for their auxotrophic markers to confirm the identity of the strains.

Sequence analysis showed that the Cap2 contains the 17-amino acid HAP4L domain (Pfam accession PF10297) at its amino-terminal region. Because the bZIP and HAP4L domains are located next to each other, we have named them the bipartite domain. Cap2 was of great interest to us because Cap2 orthologs found in multiple fungal genomes have been shown to be required for growth under iron-deprivation conditions and for regulation of iron homeostasis (17, 19–21, 61–63). Although a point mutation in the HAP4L domain of Hap4a impaired the growth of Histoplasma capsulatum in glycerol medium (26), the requirement of the HAP4L domain or the bZIP domain for Cap2 function was not understood.

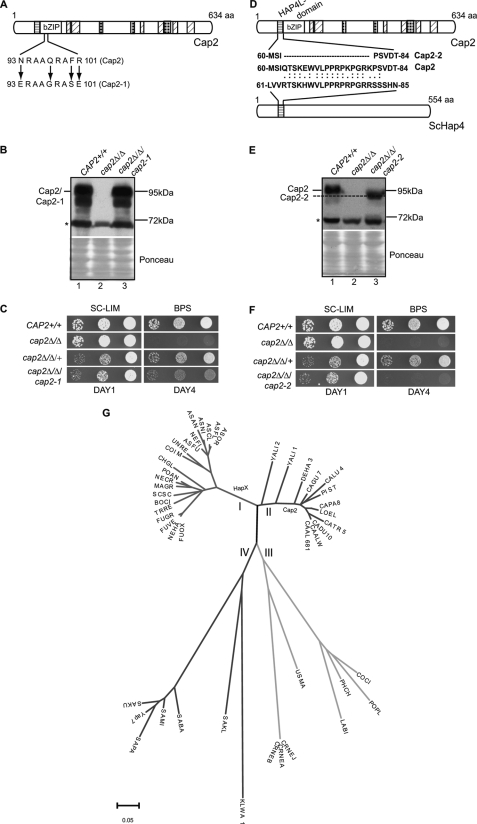

Both bZIP and HAP4-like Domains Are Required for CAP2 Function

To examine the requirement of bZIP domain for Cap2 function in vivo, we carried out site-directed mutagenesis. Previous high resolution crystal structure of the S. pombe Pap1 Yap/bZIP domain had revealed that the basic region motif NXXAQXXFR makes direct contacts with the 5′-TTACGTAA-3′ DNA element (64). Moreover, mutational analysis had also established the requirement of basic region residues in the Gcn4 bZIP domain for DNA interaction (57, 65). Therefore we constructed strains bearing the cap2–1 allele containing substitutions in four of the five critical amino acid residues, Asn-93, Gln-97, Phe-100, and Arg-101 (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis showed that expression of Cap2–1 protein was comparable with the wild-type (Fig. 3B). The cap2–1 allele was unable to fully complement the BPS-sensitive growth defect of the cap2Δ strain (Fig. 3C). These data indicated that the bZIP domain is critical for Cap2 function under iron limiting conditions.

FIGURE 3.

Both bZIP and the HAP4L domains are required for Cap2 function. A, schematic diagram of Cap2 protein showing amino acid residues within the basic region of the bZIP domain. The wild-type (Cap2) residues from 93 to 101 are shown above and the corresponding quadruple mutant (Cap2–1) residues, generated by site-directed mutagenesis, are shown below. B, Western blot analysis of the Cap2–1 protein. Whole cell extracts prepared from strains grown in iron-limiting conditions (SC-LIM plus 0.1 mm BPS for 5 h) were blotted and probed with affinity-purified rabbit anti-Cap2 polyclonal antibody (1:2500). The position of the ∼95-kDa Cap2 band is indicated; a nonspecific band (*) below the 72-kDa marker was consistently observed in all the extracts and served as a loading control. The cap2Δ extract only contained the 72-kDa nonspecific band, establishing the identity of the 95-kDa Cap2 protein band. C, the cap2–1 mutant strain is growth impaired under iron-limiting conditions (50 μm BPS). D, schematic diagram showing the evolutionarily conserved HAP4L domain in Cap2 and the S. cerevisiae Hap4 (ScHap4) proteins. The amino acid residues deleted in Cap2–2 protein are depicted by dotted lines. E, Western blot analysis of Cap2–2 protein expression. F, deletion of the HAP4L domain abrogated growth under iron-depleted conditions. Strains used were CAP2+/+ (SN152), cap2Δ/Δ (RPC75), RPC309 (cap2Δ/Δ/cap2–1), and RPC286 (cap2Δ/Δ/cap2–2). G, the bipartite HAP4L-bZIP domain was identified in 46 fungal genomes. The multiple sequence alignment of the HAP4L-bZIP bipartite domain, created using MUSCLE 3.0 software, was edited by removing gaps in the alignment between the HAP4L and bZIP domains. A core 60-amino acid region was obtained comprising a highly conserved 20-amino acid HAP4L domain, an insert of 7 amino acids, and 33 amino acids of the bZIP domain. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA4 software. The clustering represented Pezizomycotina sequences including A. nidulans HapX (I), Saccharomycotina sequences including Cap2 (II), Agaricomycotina and Ustilaginomycotina sequences (III), and a second subset of the Saccharomycotina (IV) branch occupied by Yap7. The scale bar shows the number of amino acid differences per site. The details of the unique identifiers of proteins and that of the fungal species are provided under supplemental Table S4B.

To investigate the requirement of the HAP4L domain for Cap2 function, we constructed the cap2–2 allele, lacking the HAP4L domain (residues 63 to 79) (Fig. 3D). Although the Cap2–2 expression was not impaired (Fig. 3E, lane 3), the cap2-2 strain was unable to grow in BPS-containing medium (Fig. 3F). Thus the HAP4L domain is critically required for Cap2 function under iron limiting conditions. We carried out a systematic identification and phylogeny analyses of hapX and Cap2-like protein sequences bearing the bipartite domain and identified 47 sequences, the bulk of them not previously studied, from 46 of the 62 fungal genomes analyzed (supplemental Table S4B), indicating that this protein family is highly pervasive in the fungal kingdom (Fig. 3G). Multiple sequence alignment of the 47 bipartite domain sequences revealed the Yap-like amino acid residues in the bZIP domain of all sequences.

Next, we wished to test if the bZIP and HAP4L domains perform independent functions in Cap2. Because Yap proteins form homodimers (64), we carried out trans-complementation assays by co-expressing the two cap2 alleles, cap2–1 (bZIP mutant) and cap2–2 (HAP4L deletion mutant). Results of the trans-complementation assay showed that the strains expressing both cap2–1 and cap2–2 did not confer BPS resistance, indicating that the two defective copies did not complement each other (rows 6 and 9, Table 1). Together these data demonstrated that both bZIP and HAP4L domains are required for Cap2 function, and the lack of trans-complementation by the two mutant proteins suggests that the two domains perform independent functions in vivo.

TABLE 1.

Trans-complementation assay to examine the requirement of HAP4L-bZIP bipartite domain

The caSAT1-marked plasmids bearing CAP2, cap2–2, and cap2–1 were integrated into RPC278 (cap2Δ), RPC286 (cap2–2), or RPC326 (cap2–1) to generate strains expressing wild-type and/or mutant cap2 in all combinations shown. The strains bearing the constructs were verified by PCR and spot assay carried out in SC-LIM or SC-LIM + 50 μm BPS plates. Plates were incubated at 30 °C and relative growth scored by visual examination. − indicates no growth.

| S. No. | Strain | CAP2 allele 1 | CAP2 allele 2 | Growth on BPS plate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SN152 | CAP2 | CAP2 | 2.0+ |

| 2 | RPC278 | cap2Δ | cap2Δ | − |

| 3 | RPC510 | cap2Δ | CAP2 | 1.5+ |

| 4 | RPC286 | cap2Δ | cap2–2 | − |

| 5 | RPC506 | cap2–2 | CAP2 | 1.5+ |

| 6 | RPC517 | cap2–2 | cap2–1 | − |

| 7 | RPC326 | cap2Δ | cap2–1 | − |

| 8 | RPC511 | cap2–1 | CAP2 | 2.0+ |

| 9 | RPC521 | cap2–1 | cap2–2 | − |

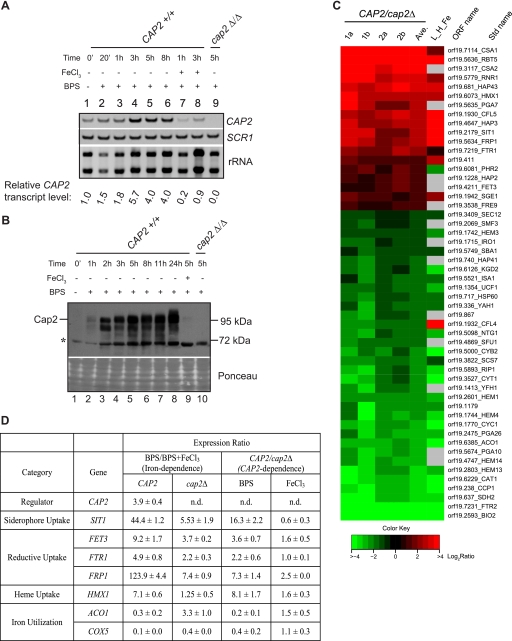

Transcriptome Profiling and Gene Ontology Analysis of Cap2 Regulon

Because the CAP2 gene is required for growth under iron-deprivation conditions, we examined if the CAP2 mRNA and protein levels were regulated by iron availability. RT-PCR analysis showed that iron deprivation led to up-regulation of CAP2 mRNA in a time-dependent manner, with a maximum induction of 5.7-fold after 3 h of BPS addition (Fig. 4A). Addition of iron to BPS-containing medium led to repression of CAP2 mRNA levels (Fig. 4A, lanes 7 and 8). Western blot analysis also showed that the Cap2 protein was highly induced upon BPS treatment and was undetectable in cell extracts from iron-containing medium (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

CAP2-dependent transcriptome profiling. A, time course of CAP2 mRNA induction in iron-limiting medium. Total RNA isolated from C. albicans strain CAP2+/+ (SN152) and cap2Δ/Δ (RPC75) were used for first strand cDNA synthesis. 10-fold dilution of the cDNA preparation was used as a template for PCR using CAP2 and endogenous control SCR1 primers and the PCR products were resolved on a native polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Total rRNA profile obtained in the agarose gel is shown. The relative expression level of CAP2 mRNA, normalized to SCR1 RNA (an RNA polymerase III transcript (48)), was expressed for each time point with reference to the 0 min sample. B, Western blot analysis of Cap2 expression. Whole cell extracts from CAP2+/+ (SN152) and cap2Δ/Δ (RPC75) strains were used for immunoblot analysis. C, heat map of iron-related genes differentially expressed in a CAP2-dependent manner. Two-color microarray data expressed as log2 CAP2/cap2Δ ratio (four replicates 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b and average of the four replicates, Ave) is plotted as heat map. The L_H_Fe data (14) is also shown for comparison. The color scale at the bottom indicates the log2 ratio (CAP2/cap2Δ). D, qRT-PCR analysis of selected genes differentially expressed in CAP2/cap2Δ microarray data. For relative quantification, ΔCT values were derived after normalization to SCR1 transcript levels (endogenous control), and ΔΔCT values were derived using either BPS + FeCl3 sample as calibrator for iron dependence or cap2Δ sample as calibrator for CAP2-dependence. Fold-change (2−ΔΔCT) was calculated from the average of at least three RNA preparations, and S.D. was determined.

To identify Cap2-regulated genes, we carried out transcriptome profiling (66, 67) using the C. albicans whole genome microarray (50). We compared the mRNA profiles of wild-type and cap2Δ cells cultured in BPS-containing medium and identified 420 up-regulated and 509 down-regulated genes (total 15.8% of the ORFs examined) that showed statistically significant differential expression (supplemental Table S5). To identify Cap2-regulated biological processes, we carried out Gene Ontology analysis of the differentially expressed genes using Bingo 2.42 software. We obtained several overrepresented, statistically significant GO functional processes. Ten genes were found to be associated with the transition metal ion transport including several genes in the iron uptake pathway and will be discussed later. Moreover, seven up-regulated genes were associated with the pyruvate metabolic process. Interestingly, pyruvate production and increased glycolysis has also been observed during iron deprivation in S. cerevisiae (68). Our microarray data also revealed several transcriptional regulator genes that showed Cap2 dependence, of which 25 genes were up-regulated, and 15 were down-regulated. The differential regulation of these transcriptional regulator genes would likely amplify the signal perceived by CAP2 during the iron deprivation response and account for the large Cap2 transcriptome, thus indicating that Cap2 is a master regulator of iron homeostasis in C. albicans.

GO analysis of the down-regulated genes also identified several biological processes including generation of precursor metabolites and energy, aerobic respiration, respiratory chain complex assembly, mitochondrial ATP synthesis-coupled electron transport, heme and other cofactor metabolism, de novo NAD biosynthesis, 2-oxoglutarate metabolism, and protein targeting to peroxisomes (data not shown). The bulk of these processes require iron, and their down-regulation can be viewed as a mechanism geared to reduce iron utilization. Of the six superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes, SOD1–SOD6 in C. albicans genome (69), the manganese superoxide dismutase genes, SOD2 and SOD3, are repressed in a Cap2-dependent manner. There are previous reports that deletion of CuZn and/or manganese SOD genes leads to accumulation of free iron in S. cerevisiae cells (70, 71). Thus it appears that Cap2-mediated repression of SOD gene expression could additionally mobilize iron in vivo.

Cap2-dependent Differential Expression of Genes Regulated by Iron Availability

To obtain insights into Cap2 regulation of iron homeostasis, we analyzed our microarray data in the context of genes involved in iron homeostasis. We retrieved the low iron_versus_high iron (L_H_Fe) microarray data of Lan et al. (14), and a list of all 133 genes annotated in CGD (downloaded April 21, 2010) bearing the keyword “iron,” plus five additional genes CSA1, CSA2, PGA7, FRE9, and orf19.867, related to iron homeostasis (32). Comparison of the three datasets showed that 33 genes were up-regulated in L_H_Fe data and showed Cap2 dependence. Twelve of these genes were annotated as iron-related and included genes involved in three iron uptake pathways. Of the 48 down-regulated genes in both the experimental data, 25 were annotated in CGD as iron-related.

To examine the behavior of the Cap2-dependent iron-related genes, we generated a heat map for the above discussed 12 up-regulated and 25 down-regulated genes (Fig. 4C). The L_H_Fe data (14) for these genes was also included in the heat map for comparison. We also included an additional 15 iron-related genes that showed Cap2-dependent up-regulation (six genes) or down-regulation (nine genes), for which the L_H_Fe data were not available. Interestingly, eight of the 18 up-regulated genes in the CAP2/cap2Δ data have been shown experimentally to be involved in iron uptake pathways, viz., SIT1 encoding siderophore transporter (72), FET3, FTR1, FRP1, CFL5, and FRE9 encoding reductive iron uptake (73, 74), and RBT5 and HMX1 being part of heme uptake (35, 75, 76) pathways (Fig. 4C). Our microarray data also identified Cap2-dependent up-regulation of CSA2, PGA7 (predicted GPI anchored cell wall protein), PHR2, FET3, and FRE9 not found in the L_H_Fe data (Fig. 4C). We also found that HAP2 and HAP32, two components of the trimeric DNA-binding HAP complex, were induced in a CAP2-dependent manner.

Iron-sulfur containing genes BIO2, SDH2, ACO1, CYC1, ISA1, and heme containing genes HEM1, HEM3, HEM4, HEM13, and HEM14 were down-regulated in a CAP2-dependent manner. There were indications that Cap2 also facilitated iron mobilization by down-regulating SMF3 and YFH1, shown previously to be involved in iron storage in S. cerevisiae (77, 78). The heat map also showed that several respiratory pathway genes including ACO1, CYC1, SDH2, ISA1, RIP1, and YAH1 were down-regulated in a Cap2-dependent manner upon iron deprivation. The behavior of these genes can be expected because iron is an essential cofactor for their activity.

Cap2-dependent Activation of Three Iron-acquisition Pathways and Repression of Iron-requiring Enzymes

Expression of key genes involved in iron homeostasis, identified in our microarray data, was validated by qRT-PCR. The CAP2 mRNA was highly induced in iron-depleted versus iron-repleted media (Fig. 4D) confirming the RT-PCR data (Fig. 4A). The data also showed that the expression of genes encoding three different iron uptake pathways, viz., siderophore, reductive, and heme uptake, were highly induced upon iron deprivation in the wild-type strain, but substantially impaired in the cap2Δ strain (iron dependence, Fig. 4D). Iron deprivation induced the expression of FRP1 and SIT1 to ∼124- and 44-fold, respectively, in the wild-type strain; their induction in the cap2Δ strain, however, was substantially reduced but not completely lost. Among the induced genes analyzed, only the induction of HMX1 showed absolute Cap2 dependence. Whereas the activation of other genes showed unmistakable Cap2 dependence, the activation of FRP1 and SIT1 was still retained in the cap2Δ strain indicating an additional means of regulation of expression.

The two iron utilization genes ACO1 and COX5 also showed CAP2-dependent strong repression in iron-depleted medium compared with iron-replete medium (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, the expression of ACO1 was higher by ∼3-fold in the cap2Δ strain. Analysis of the data also showed Cap2 dependence for activation and repression of the same genes only in iron limited but not in high iron medium. Taken together, the qRT-PCR data demonstrated Cap2-dependent activation, and repression of selected iron homeostasis genes under iron-deprivation conditions.

Expression of ACO1 and other iron utilizing genes is repressed by CTH2 in S. cerevisiae. Therefore we examined the requirement of C. albicans CTH2/19.5334 for repression of ACO1 and found that its expression was derepressed ∼1.5-fold in the cth2Δ strain (data not shown). Moreover, growth of the cth2Δ strain was also not compromised in BPS medium. Thus CaCTH2/19.5334 does not seem to have a pronounced effect in repressing ACO1 expression.

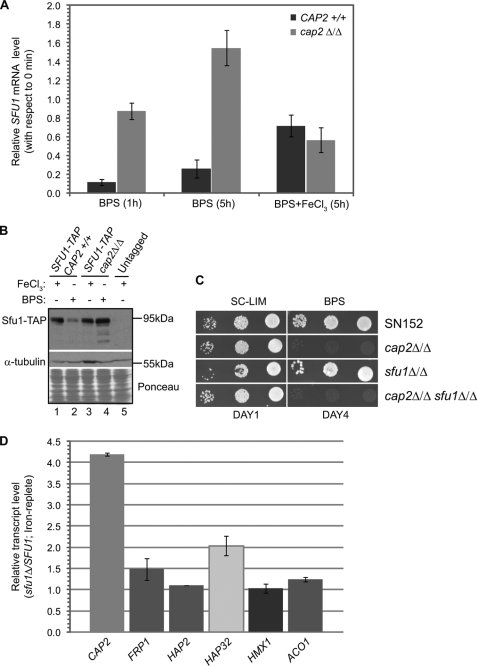

Cap2-dependent Repression of the Negative Regulator Sfu1

Sfu1 was previously shown to be a repressor of iron uptake genes and of Cap2 under iron-replete conditions (14). Moreover, our CAP2/cap2Δ microarray data (Fig. 4C) revealed that under iron-deprivation conditions, SFU1 expression was repressed in a CAP2-dependent manner. To confirm this, we carried out real-time qPCR analysis of SFU1 transcript from wild-type and cap2Δ cells. The data showed that SFU1 was repressed ∼5–10-fold by 1 and 5 h of BPS treatment (Fig. 5A). Significantly, this down-regulation of SFU1 mRNA was completely abrogated in cap2Δ cells (Fig. 5A), indicating that Cap2 is required to repress SFU1 in BPS medium. In iron-replete medium, however, SFU1 expression was derepressed in both wild-type and cap2Δ cells (Fig. 5A). In agreement with mRNA analysis, Sfu1 protein expression was repressed in BPS medium in the wild-type strain but derepressed in the cap2Δ strain (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 and 4).

FIGURE 5.

Reciprocal regulation of Cap2 and Sfu1 expression. A, qRT-PCR analysis of SFU1 mRNA expression. For relative quantification, ΔCT values were derived after normalization to SCR1 transcript levels, and ΔΔCT values were derived with the 0-h sample as calibrator in CAP2+/+ (SN152) and cap2Δ/Δ (RPC75) backgrounds. The average SFU1 mRNA expression ratio was derived from two independent RNA preparations and S.D. of the measurements shown as error bars. B, Western blot analysis of Sfu1 protein expression. Cell extracts from C. albicans SFU1-TAP strains RPC391 (CAP2+/+), RPC422 (cap2Δ/Δ), and untagged control (SN152) cultured in either iron-deplete (SC-LIM plus 100 μm BPS) or in iron-replete (SC-LIM plus 100 μm FeCl3) media were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with 1:1000 dilution of rabbit anti-TAP polyclonal antibody (Open Biosystems; top panel), or with 1:1000 dilution of monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma; middle panel). The Ponceau S stain of the blot is also shown (bottom panel). C, the sfu1Δ/Δ cap2Δ/Δ double mutant showed the same phenotype as cap2Δ/Δ mutant in iron-depleted medium. C. albicans strains SN152, RPC75, RPC434 (sfu1Δ/Δ), and RPC474 (sfu1Δ/Δ cap2Δ/Δ) were used for the spot assay. D, qRT-PCR analysis of Cap2 target genes in wild-type (SN152) and sfu1Δ/Δ mutant (RPC434) strains grown under iron-replete (SC-LIM plus 100 μm FeCl3) medium for 5 h.

Together the data presented here showed that Cap2 and Sfu1 regulate expression of each other in a reciprocal manner in iron-deprived and iron-containing media, respectively. Moreover, repression of SFU1 mRNA by Cap2 during iron-limited conditions would further relieve the negative regulatory loop and maximize iron acquisition. To further probe the regulatory interaction between SFU1 and CAP2, we carried out epistasis analysis. We constructed the cap2Δ sfu1Δ double deletion strain and tested its ability to grow in BPS-containing medium. The phenotype test showed that the cap2Δ sfu1Δ double mutant strain displayed the same phenotype as the cap2Δ strain, indicating that CAP2 is epistatic to SFU1 under iron-depleted conditions (Fig. 5C).

We hypothesized that if SFU1 had a role in repression of CAP2 in the iron-replete medium, as indicated previously by microarray analysis (14), the attendant derepression of CAP2 upon sfu1 deletion could result in induction of Cap2-target genes. Our qRT-PCR analysis showed that indeed the CAP2 mRNA level was derepressed ∼4.0-fold in the sfu1Δ strain compared with the level in the wild-type strain in high iron medium (Fig. 5D). However, the mRNA level of Cap2 up-regulated genes FRP1, HAP2, HAP32, and HMX1 was not substantially altered indicating that expression of CAP2 mRNA was not sufficient to activate its target genes in high iron medium (Fig. 5D). Moreover, expression of ACO1 (Fig. 5D) and CYC1 (data not shown), down-regulated in a Cap2-dependent manner in low iron medium, was unchanged in the sfu1Δ strain in high iron medium. Western blot analysis showed that the Cap2 protein level was only slightly elevated in the sfu1Δ extract compared with the wild-type extract from the high iron medium (data not shown), indicating that regulation of CAP2 expression likely occurs at both mRNA and protein levels.

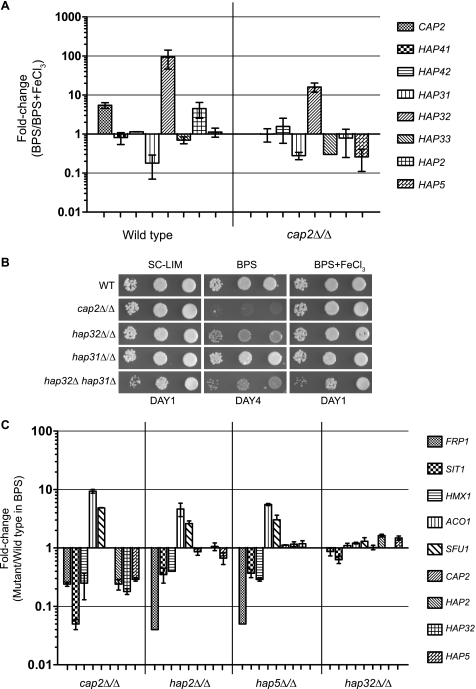

Cap2-dependent Up-regulation of Components of the HAP Regulatory Complex

There are previous reports that Cap2 or its orthologs likely function in a complex with Hap2-Hap3-Hap5 (19, 21, 29). In a previous study, three HAP4-like genes and two HAP3-like genes were identified in the C. albicans genome (27). Our bioinformatic analyses further showed that the Candida clade genomes had three each of HAP3 (HAP31, HAP32, and orf19.5825 named HAP33), HAP4 (HAP41, HAP42, and HAP43/CAP2), and HAP5 (orf19.1973/HAP5, orf19.3063 named HFL1, and orf19.2736 named HFL2) but only a single HAP2 sequence. Although the three C. albicans Hap5-like sequences each had a histone-fold domain like that of the S. cerevisiae Hap5, only Hap5 is likely to be a functional ortholog of Hap5 due to the presence of the Hap4-interaction domain (data not shown).

As discussed previously, CAP2/HAP43 was induced in iron-depleted versus iron-repleted media in the wild-type strain. Therefore we investigated which of the multiple HAP genes were also induced under iron-deprivation conditions. The expression of HAP41 and HAP42 were unaffected (Fig. 6A), whereas of the HAP3-like genes, only HAP32 mRNA expression was highly induced upon iron deprivation (∼93.5-fold) in a Cap2-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). HAP31 was repressed in iron-depleted conditions but this repression was not Cap2-dependent. The expression of HAP33 was unchanged in the wild-type strain but was down-regulated in the cap2Δ mutant. Thus only HAP32 expression was up-regulated by low iron as well as Cap2. The HAP2 mRNA was induced 4.5-fold in iron-depleted relative to iron-replete conditions, and this induction was completely lost in the cap2Δ strain (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, although HAP5 expression was not induced by iron deprivation in the wild-type strain, HAP5 expression was reduced in the cap2Δ strain (Fig. 5A), indicating that Cap2 was required to maintain HAP5 expression in iron-deprivation conditions. Whereas activation of HAP2 expression was almost entirely dependent on Cap2, the activation of HAP32 expression, although reduced ∼10-fold, was still maintained in the cap2Δ mutant indicating other forms of regulation.

FIGURE 6.

Cap2-dependent differential expression of HAP genes. A, qRT-PCR analysis of HAP gene transcripts. For relative quantification, ΔCT values were derived after normalization to the SCR1 transcript levels, and ΔΔCT values were derived using the BPS + FeCl3 sample as calibrator. The bar graph shows the fold-change (BPS versus BPS+ FeCl3) of HAP gene transcripts in wild-type and cap2Δ/Δ background from two RNA preparations. B, HAP32 but not HAP31 is required for growth under iron-depleted medium. Strains WT (SN152), cap2Δ/Δ (RPC75), hap32Δ/Δ (RPC432), hap31Δ/Δ (RPC445), and hap32Δ/Δ hap31Δ/Δ (RPC449) were used. C, qRT-PCR analysis of Cap2 target genes in cap2Δ/Δ (RPC75), hap2Δ/Δ (087), hap5Δ/Δ (093), and hap32Δ/Δ (RPC432) and expressed as fold-change. Data are the average values from 2–3 RNA preparations and replicate assays.

We carried out mutational analysis to examine the requirement of HAP3-like genes and found that the hap32Δ mutant but not the hap31Δ mutant was impaired for growth in BPS medium (Fig. 6B), but the defective phenotype was not as tight as that of the cap2Δ mutant (Fig. 6B). The phenotype of the hap32Δ hap31Δ double mutant could not be accurately assessed in BPS medium due to the growth defect of the double mutant in BPS + FeCl3 medium (Fig. 6B). It needs to be seen if HAP33 has any role in growth of C. albicans in BPS conditions, and if that contributed to the residual growth seen in the hap32Δ mutant. In any case, our data showed that HAP32, but not HAP31, had a predominant role for growth under iron-deprivation conditions. Recent reports showed that orf19.1973/HAP5 (19, 20) and orf19.1228/HAP2 (20) are required for growth of C. albicans in BPS-containing medium. Thus all three core HAP components HAP2, HAP32, and HAP5, are required for growth of C. albicans under iron-deprivation conditions.

Cap2 Target Gene Regulation Is Dependent on Core HAP Components

To investigate the requirement of the core HAP complex in the regulation of Cap2-target gene expression, we also measured transcript levels in hap2Δ, hap5Δ, and hap32Δ strains under iron-deprivation conditions. Data showed that in both hap2Δ and hap5Δ strains, FRP1, SIT1, and HMX1 expression was impaired, and ACO1 expression was elevated (Fig. 6C), indicating that both Hap5 and Hap2 subunits, in addition to Cap2 are required for the regulation. However, the expression of these mRNAs was only slightly affected in the hap32Δ strain. We also investigated the requirement of the HAP complex components for activation of the expression of HAP2, HAP32, and HAP5 genes. Data showed that only cap2Δ but not the hap mutants impaired the expression of the mRNA encoding HAP components in iron-deprived medium (Fig. 6C). These data suggests that Cap2 alone was required for activation of expression of HAP complex core components. Interestingly, regulation of SFU1 expression was dependent on both Cap2 and the HAP complex core components.

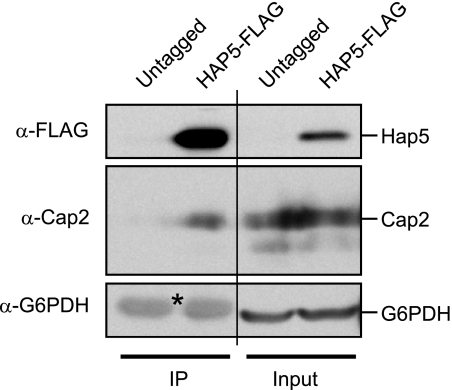

Cap2 Associates with HAP Complex in Whole Cell Extracts

We hypothesized that the subset of Cap2/HAP43, Hap2, Hap32, and Hap5, by virtue of their functional requirements under iron-deprivation conditions, likely interacted in a complex to regulate iron homeostasis in C. albicans. To test this possibility, we chromosomally tagged one allele of HAP5 at its carboxyl terminus using a dual epitope tag comprising His6-FLAG3 and performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Immunoprecipitation of Hap5-His6-FLAG3 with anti-FLAG beads could efficiently pulldown Hap5 from tagged cell extracts but not from untagged control cell extracts (Fig. 7). Upon probing the blot with affinity-purified anti-Cap2 antibody, we found that a significant fraction of Cap2 was coimmunoprecipitated specifically from the tagged HAP5 strain but not from untagged control strain. Comparison of the band intensities in the input and the immunoprecipitated samples indicated that Cap2 and Hap5 proteins were not recovered in equivalent proportions in the immunoprecipitated sample suggesting either a weaker association of Cap2 with Hap5 or that a fraction of Cap2 exists outside of Hap5 in cell extracts. We also probed the blot with control glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody and found that the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase band was detectable only in the input but not in immunoprecipitated samples (Fig. 7). These data led us to conclude that Cap2 associated with Hap5 in vivo under iron-deprivation conditions.

FIGURE 7.

Cap2 interacts with Hap5 in cell extracts. Protein extracts from untagged (SN152) and HAP5-FLAG (HAP5::His6-FLAG3; RPC552), cultured in iron-limiting condition, were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel. The IP and input (100 μg) samples were analyzed by Western blotting. The bands marked with an asterisk in the IP lanes are nonspecific bands and correspond to signals of IgG eluted from the IP beads; note that the size of this species is also larger than the glyceraldehyde-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) in the input lanes.

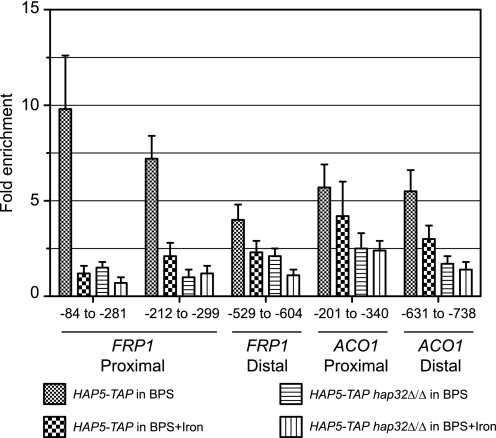

Hap5 Is Recruited to Cap2 Target Gene Promoters in a Hap32-dependent Manner

To assess promoter occupancy of the HAP complex using ChIP assay, we constructed a HAP5-TAP strain in wild-type and hap32Δ backgrounds. We ascertained that introduction of TAP tag did not disrupt HAP5 function by examining growth of the HAP5-TAP/HAP5-TAP strain on BPS medium (data not shown). The HAP5-TAP strains were grown in BPS or BPS plus iron containing medium for 5 h and the Hap5-TAP-bound chromatin was immunoprecipitated. The immunopurified DNA was analyzed for Hap5 target promoters by qRT-PCR. The data showed that the FRP1 promoter (−84 to −281 with respect to ATG) was efficiently precipitated, ∼9.8-fold, as compared with a control nonspecific region in BPS medium but not in iron-supplemented medium (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the Hap5-TAP occupancy was completely abolished in the hap32Δ background. The −84 to −281 sequence contained the 5′-CCAAT-3′ box at −138, shown previously to be important for activation of the FRP1-lacZ reporter (19).

FIGURE 8.

Hap5 is recruited to FRP1 and ACO1 promoters. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed using HAP5-TAP strains RPC453 (HAP32/HAP32) and RPC562 (hap32Δ/hap32Δ) cultured in BPS or in BPS plus iron medium as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Total input DNA and immunoprecipitated DNA from multiple locations of the two target promoters FRP1 and ACO1, and a control non-coding region from chromosome 1 (ca21chr1_1573500–1574000) were analyzed by qRT-PCR. The ΔCT values were derived after normalization to input samples separately for the target and control regions, and ΔΔCT values were derived using the control region as a calibrator. The fold-enrichment (calculated as 2−ΔΔCT) for Hap5-TAP at each location was expressed relative to that of the control location. Control ChIP reactions using untagged strain chromatin extracts yielded undetectable signal demonstrating the specificity of the chromatin IP reactions.

Examination of the FRP1 promoter sequence showed two additional CCAAT box motifs at −241 and −532 in the upstream region (data not shown). Therefore we examined Hap5-TAP occupancy at these locations as well. The data showed ∼7.2- and ∼4.0-fold enrichment at both locations in the FRP1 promoter (Fig. 8), indicating Hap5 recruitment to multiple locations in this promoter. Furthermore, higher occupancy was seen at the two proximal (−138, −241) FRP1 promoter regions compared with the distal region examined.

We also examined Hap5-TAP occupancy at the ACO1 promoter in the same ChIP assay. The data showed high levels of Hap5 occupancy at two ACO1 upstream regions bearing CCAAT motifs at positions −250 and −658 (Fig. 8). The Hap5 occupancy at this promoter was also Hap32-dependent (Fig. 8). Interestingly, Hap5 occupancy, although elevated in BPS medium, was not abrogated in iron-supplemented medium. Thus Hap5 binding at FRP1 and ACO1 promoters responded differently to iron status. These data demonstrated that Hap5 is recruited to both FRP1 and ACO1 promoters in vivo in a Hap32-dependent manner, providing a mechanistic framework for a direct role for the Cap2-HAP complex in activation and repression of transcription of iron homeostasis genes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that the Cap2-HAP complex is the central and a critical regulator of iron homeostasis in C. albicans. First, CAP2 is required for growth of C. albicans in iron-limited medium in vitro and for virulence in the mouse model. The requirement of CAP2, also called HAP43, for growth under iron-deprivation conditions was independently identified in other studies (19, 20, 61). Our mutational analyses showed that both bZIP and HAP4L domains are required for Cap2 function. Second, CAP2 expression is up-regulated in iron-limited medium and repressed in iron-replete medium. Third, transcriptome profiling indicated that CAP2 regulates iron homeostasis chiefly by transcriptional activation of genes in three iron uptake pathways and repression of iron utilizing and iron storage pathway genes. Fourth, several lines of evidence indicated that Cap2 functions in a complex with the core HAP complex, namely Cap2-dependent up-regulation of HAP32, HAP2, and HAP5, requirement of the HAP components for regulation of Cap2 target genes, and association of Cap2 with Hap5 in cell extracts. Finally, iron deprivation elicited Hap5 recruitment to FRP1 (Cap2-induced) and ACO1 (Cap2-repressed) promoters in a Hap32-dependent manner, indicating a direct role in vivo for the Cap2-HAP complex for regulation of iron homeostasis.

Transcriptional Regulation of Cap2 Expression

Iron deprivation lead to expression and activation of Cap2, which has a Yap-like bZIP domain and the fungal-specific HAP4-like domain (Fig. 9). The iron-dependent regulation of CAP2 expression was first noted in a C. albicans microarray study (14), and indeed for CAP2 orthologs in other systems as well (17, 21, 79). In iron-replete media, although the CAP2 mRNA level was diminished to a low basal level, the Cap2 protein level was reduced to an undetectable level (Fig. 4B), indicating a tighter control of Cap2 protein expression. However, the mechanism(s) controlling the expression of Cap2 in iron-depleted or iron-replete conditions are not understood. Examination of the Cap2 amino acid sequence showed multiple Cys-rich regions (Fig. 1B); it needs to be determined if one or more of the Cys-rich regions are required for Cap2 activity in vivo. In any case, because Cap2 expression is tightly controlled at both mRNA and protein levels, together our data suggests that regulation of Cap2 expression is the primary step in the iron-deprivation response by C. albicans.

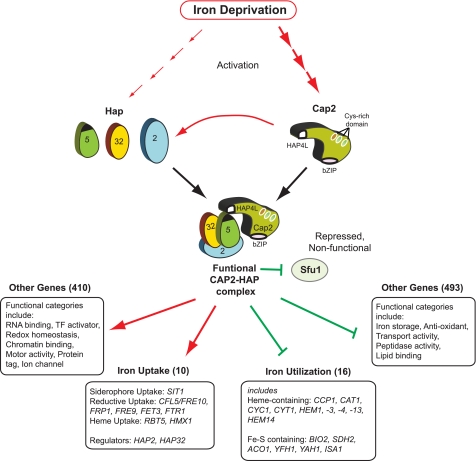

FIGURE 9.

Summary of the Cap2-HAP-mediated regulation of iron homeostasis in C. albicans. Iron deprivation strongly elicited the induction of Cap2 mRNA and protein expression (thick broken arrows); in contrast, in iron containing medium the Cap2 expression was repressed. Both HAP4L and bZIP domains are required for Cap2 function. Mutational analyses showed that HAP32, HAP2, and HAP5 are required for C. albicans growth in iron-depleted medium. Expression analysis showed Cap2-dependent activation of HAP2 and HAP32 expression; additionally, HAP5 expression was also dependent on Cap2. Iron deprivation also elicited partial induction (thin broken arrows) of HAP32 expression in the cap2Δ mutant strain indicating a role for other transcriptional regulator(s). Cap2, but not Hap2, Hap5, and Hap32, was required for induction of HAP2, HAP32, and HAP5 expression in low iron medium. Cap2 functions in association with the HAP complex as Cap2 was coimmunoprecipitated with Hap5 from cell extracts. Furthermore, SFU1 mRNA expression was repressed in a Cap2-HAP complex dependent manner. Because sfu1Δ mutation led to derepression of CAP2 mRNA expression but did not induce the Cap2 target genes, Sfu1 seems to primarily mediate Cap2 repression, and in its wake leading to the repression of iron uptake gene expression in high iron medium. Transcriptome profiling showed Cap2-dependent up-regulation of 10 iron uptake genes and about 410 genes in several functional categories. Additionally, the transcriptome data also identified Cap2-dependent down-regulation of 16 genes involved in iron utilization or that require iron for its activity, and 493 other genes representing several functional categories. Chromatin IP assays showed Hap5 occupancy to the promoters of both Cap2-induced (FRP1) and Cap2-repressed (ACO1) genes, thus indicating that Cap2-HAP complex functions by direct promoter binding to up- or down-regulate gene expression to maintain iron homeostasis.

Cap2-dependent Regulation of Iron Homeostasis Transcriptome

Microarray data revealed Cap2-dependent up-regulation of numerous genes including eight iron-uptake genes belonging to three pathways, viz., siderophore, reductive iron, and heme uptake. Although most of the Cap2-induced iron uptake genes were also induced upon iron depletion (14), our data identified Cap2-dependent induction of additional genes in the iron uptake pathway. Interestingly, at least three of the iron uptake genes, FRE1, FRE2, and FTH1, that were induced upon iron deprivation in a wild-type strain did not show Cap2 dependence indicating other modes of regulation of this subset of genes. Our microarray data also revealed that genes encoding iron-utilizing proteins such as Fe-S proteins and heme proteins and numerous other genes are repressed in a Cap2-dependent manner (Fig. 9). Moreover, iron storage genes are also repressed in a Cap2-dependent manner, likely contributing to mobilization of iron from endogenous pools.

Cap2-HAP Regulatory Network

Feedback Regulation of the Sfu1 Negative Regulator

How do cells deal with the negative regulator Sfu1 under iron-deprivation conditions? First, in a feedback loop, the expression of SFU1 is repressed in a Cap2-dependent manner (Fig. 9). The Cap2 control seems to be limited to iron-deprivation conditions because under high iron conditions SFU1 mRNA and protein levels were comparable in wild-type and cap2Δ strains. Second, it seems likely that any residual Sfu1 protein could also be inactive in the absence of iron, as shown previously for its ortholog Sre1 in H. capsulatum (80). Although deletion of SFU1 led to 4-fold higher expression of CAP2 mRNA (Fig. 5D), but not Cap2 protein levels, the CAP2 target genes are not induced. These data suggest that regulation of Cap2 expression and function operate at multiple levels possibly to enforce stringent regulation of iron homeostasis. Furthermore, expression analysis suggested that Sfu1 seems to exert its repressive activity predominantly at the Cap2 promoter, but not at the promoters of the core HAP complex components.

Feed-forward Regulation and Cap2-HAP Complex Formation

We obtained several lines of evidence indicating that Cap2 functions in a complex with the Hap2-Hap32-Hap5 complex in vivo. Iron deprivation led to Cap2-dependent activation of HAP2 and HAP32 and expression of HAP5 genes (Fig. 9). Although low iron-elicited up-regulation of HAP32 expression was previously found (14), Cap2 dependence was not known. Our data also showed that although HAP5 expression was not regulated by iron availability in wild-type cells, Cap2 protein was required to maintain HAP5 mRNA levels during iron-deprivation conditions. Second, mutational analyses showed that both bZIP and HAP4L domains are required for Cap2 function in iron-deprivation response. Remarkably, only Cap2, but not the HAP core subunits, was required for low iron-elicited activation of core HAP components revealing an additional facet of Cap2 function. Third, we showed that Cap2 could be efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with Hap5 from cell extracts prepared from cultures grown under iron-deprivation conditions. Although previous studies indicated an interaction of Hap4-like proteins with Hap2-Hap3-Hap5 proteins from C. albicans (19, 27), our study is the first biochemical demonstration of Cap2-HAP interaction in cell extracts under iron-deprivation conditions. A recent yeast two-hybrid study also showed interaction between H. polymorpha Hap4b and Hap5 (21). Thus the HAP4L domain alone could be sufficient to mediate Cap2 interaction with Hap5. In this respect, the C. albicans Hap5/orf19.1973 also contains the Hap4-interaction domain previously identified in S. cerevisiae (29).

Genetic studies showed a requirement of HAP32, HAP2, and HAP5 for the growth of C. albicans in iron-limited medium (Fig. 4B) (19, 20). Moreover, the core HAP complex components were also required for the expression of Cap2 target genes, thereby providing functional support for HAP components in iron homeostasis regulation (Fig. 9). Structural studies using mammalian NF-YB and NF-YC heterodimers, the orthologs of Hap3 and Hap5 proteins, respectively, showed that their interaction occurred through histone H2A/H2B-like histone-fold domains (81). Moreover, the Hap32 and Hap5 proteins also could heterodimerize through their histone-fold domains (as reviewed in Ref. 82), and in association with Hap2 could constitute the core HAP regulatory complex. Such a mechanism for complex formation has previously been reported for the S. cerevisiae Hap2-Hap3-Hap5 complex (29). Although previous studies showed that interaction between S. cerevisiae Hap4 and Hap5-Hap3-Hap2 required DNA (24), data from the present study and from H. polymorpha (21) indicated that DNA may not be an absolute requirement at least for the HAP4L domain protein interaction with Hap5.

Dual Regulation by Cap2-HAP Complex Involves Direct Promoter Binding

Previous studies on Cap2-HAP orthologs indicated a mechanism of repression of genes encoding iron-utilizing proteins under iron-deprivation conditions such as Aspergillus nidulans HapX (17) and S. pombe Php4 (79). Therefore to understand the mechanism of Cap2-HAP function, we carried out a in vivo ChIP assay and demonstrated promoter occupancy of Hap5 to the CCAAT box containing regions of the ACO1 gene promoter in vivo under both iron-depleted and iron-replete media. Thus although HAP complex binding to the ACO1 promoter is not regulated by iron availability, the expression of this promoter is differentially regulated. In this respect Cap2 association with the HAP complex in iron-depleted medium is the key regulatory switch to repress ACO1 expression. This conclusion is also strengthened by our data that CaCTH2/19.5334 does not have a substantial role in ACO1 repression.

A previous study showed that the CCAAT box is required for activated expression of FRP1-lacZ reporter in C. albicans (19). Moreover, EMSA studies have shown that one or more Hap5-containing complexes can interact with CCAAT box containing promoters (19, 27). Indeed using ChIP analysis, we have demonstrated Hap32-dependent occupancy of Hap5 in vivo to FRP1 promoter regions bearing CCAAT box in iron-deprived medium. Interestingly, the Hap5 occupancy at FRP1 was not found in iron-replete medium. Thus, in contrast to the ACO1 promoter, Hap5 occupancy at the FRP1 promoter is differentially regulated by iron availability. Herein Hap32 was important for Hap5 promoter occupancy. At odds with the Hap32 requirement for Hap5 occupancy, the Cap2-stimulated expression of FRP1 was weakly dependent on Hap32. It is conceivable that absence of Hap32 weakened Hap5 occupancy, but the Hap5 association was sufficient to drive FRP1 expression, albeit at reduced levels.

A simplistic model from our data is that under iron-deprivation conditions, the Cap2-HAP complex binds to and activates the FRP1 promoter by direct recruitment of the transcriptional machinery. An alternative model is that Cap2-HAP functions as an anti-repressor by promoter binding, which could lead to destabilization of a putative repressor under low-iron conditions and consequent assembly of the transcriptional machinery. In any case, Cap2-dependent expression of the core HAP complex components HAP5, HAP32, and HAP2, and repression of the negative regulator Sfu1, and the large scope of the Cap2 regulon together indicate that Cap2 functions as a master regulator of iron homeostasis. Thus regulation of Cap2 expression by iron availability appears to be a pivotal step in the Cap2/HAP regulatory cascade to mediate iron homeostasis in C. albicans. Moreover, the dual but contrasting regulation of iron acquisition and iron storage pathways by the Cap2-HAP regulatory complex suggests a robust coordination of the cellular machinery to maintain iron homeostasis during iron deprivation in this important human fungal pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. S. Noble and A. D. Johnson, Dr. J. Morschhauser, Dr. J. Wendland, Dr. A. J. Brown, and Dr. P. Koetter for plasmids and strains; Dr. S. Noble for advice on fusion PCR protocol; Dr. K. Ganesan for reagents and advice; Dr. M. Heinz and Chris Sawyer, Washington University, for supply of the C. albicans microarray slides and advice; Ankhee Dutta for assistance with the microarray heat map. We thank Dr. C. C. Philpott for advice and helpful comments, Dr. R. S. Gokhale and Dr. A. Bhattacharya for stimulating discussions and suggestions on the manuscript, Dr. A. Datta for encouragement and support, and all members of the lab for discussions and reading of the manuscript, and the three anonymous reviewers for constructive suggestions.

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, and the UPOE and DST-PURSE grants from Jawaharlal Nehru University.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Results,” Fig. S1, and Tables S1–S5.

- SC-LIM

- synthetic complete limited iron medium

- BPS

- bathophenanthroline-disulfonic acid

- HAP4L

- HAP4-like

- CGD

- Candida Genome Database

- GEO

- Gene Expression Omnibus

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase

- qRT

- quantitative RT.

REFERENCES

- 1. Martchenko M., Levitin A., Hogues H., Nantel A., Whiteway M. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 1007–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsong A. E., Tuch B. B., Li H., Johnson A. D. (2006) Nature 443, 415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wessling-Resnick M. (1999) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 34, 285–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moye-Rowley W. S. (2003) Eukaryot. Cell 2, 381–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Massé E., Arguin M. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Philpott C. C. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 636–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rutherford J. C., Jaron S., Winge D. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27636–27643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Philpott C. C., Protchenko O. (2008) Eukaryot. Cell 7, 20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Ueta R., Fukunaka A., Sasaki R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18914–18918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rutherford J. C., Ojeda L., Balk J., Mühlenhoff U., Lill R., Winge D. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10135–10140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Puig S., Askeland E., Thiele D. J. (2005) Cell 120, 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haas H., Eisendle M., Turgeon B. G. (2008) Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 149–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liang Y., Wei D., Wang H., Xu N., Zhang B., Xing L., Li M. (2010) Microbiology 156, 2912–2919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lan C. Y., Rodarte G., Murillo L. A., Jones T., Davis R. W., Dungan J., Newport G., Agabian N. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1451–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutherford J. C., Bird A. J. (2004) Eukaryot. Cell 3, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Labbé S., Pelletier B., Mercier A. (2007) Biometals 20, 523–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hortschansky P., Eisendle M., Al-Abdallah Q., Schmidt A. D., Bergmann S., Thön M., Kniemeyer O., Abt B., Seeber B., Werner E. R., Kato M., Brakhage A. A., Haas H. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 3157–3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mercier A., Watt S., Bähler J., Labbé S. (2008) Eukaryot. Cell 7, 493–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baek Y. U., Li M., Davis D. A. (2008) Eukaryot. Cell 7, 1168–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Homann O. R., Dea J., Noble S. M., Johnson A. D. (2009) PLoS Genet. 5, e1000783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sybirna K., Petryk N., Zhou Y. F., Sibirny A., Bolotin-Fukuhara M. (2010) Yeast 27, 941–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mantovani R. (1999) Gene 239, 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forsburg S. L., Guarente L. (1989) Genes Dev. 3, 1166–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNabb D. S., Xing Y., Guarente L. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaplan J., McVey Ward D., Crisp R. J., Philpott C. C. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 646–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sybirna K., Guiard B., Li Y. F., Bao W. G., Bolotin-Fukuhara M., Delahodde A. (2005) Curr. Genet. 47, 172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson D. C., Cano K. E., Kroger E. C., McNabb D. S. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 1662–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kornitzer D. (2009) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McNabb D. S., Pinto I. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 1829–1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schaible U. E., Kaufmann S. H. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 946–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sutak R., Lesuisse E., Tachezy J., Richardson D. R. (2008) Trends Microbiol. 16, 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Almeida R. S., Wilson D., Hube B. (2009) FEMS Yeast Res. 9, 1000–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramanan N., Wang Y. (2000) Science 288, 1062–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu C. J., Bai C., Zheng X. D., Wang Y. M., Wang Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30598–30605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weissman Z., Kornitzer D. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1209–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Almeida R. S., Brunke S., Albrecht A., Thewes S., Laue M., Edwards J. E., Filler S. G., Hube B. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noble S. M., Johnson A. D. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 298–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reuss O., Vik A., Kolter R., Morschhäuser J. (2004) Gene 341, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murad A. M., Lee P. R., Broadbent I. D., Barelle C. J., Brown A. J. (2000) Yeast 16, 325–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gola S., Martin R., Walther A., Dünkler A., Wendland J. (2003) Yeast 20, 1339–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fairhead C., Llorente B., Denis F., Soler M., Dujon B. (1996) Yeast 12, 1439–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schaub Y., Dünkler A., Walther A., Wendland J. (2006) J. Basic Microbiol. 46, 416–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McCluskey K., Wiest A., Plamann M. (2010) J. Biosci. 35, 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Park Y. N., Morschhäuser J. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 1328–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Corvey C., Koetter P., Beckhaus T., Hack J., Hofmann S., Hampel M., Stein T., Karas M., Entian K. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 25323–25330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu P. Y., Winston F. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5367–5379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kohrer K., Domdey H. (1991) in Methods in Enzymology: Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology (Guthrie C., Fink G. R. eds) Vol. 194, pp. 398–405, Academic Press, Inc., San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marck C., Kachouri-Lafond R., Lafontaine I., Westhof E., Dujon B., Grosjean H. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 1816–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008) Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brown V., Sexton J. A., Johnston M. (2006) Eukaryot. Cell 5, 1726–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yatskou M., Novikov E., Vetter G., Muller A., Barillot E., Vallar L., Friederich E. (2008) BMC Res. Notes 1, 80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5116–5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kadosh D., Johnson A. D. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2903–2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maere S., Heymans K., Kuiper M. (2005) Bioinformatics 21, 3448–3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cline M. S., Smoot M., Cerami E., Kuchinsky A., Landys N., Workman C., Christmas R., Avila-Campilo I., Creech M., Gross B., Hanspers K., Isserlin R., Kelley R., Killcoyne S., Lotia S., Maere S., Morris J., Ono K., Pavlovic V., Pico A. R., Vailaya A., Wang P. L., Adler A., Conklin B. R., Hood L., Kuiper M., Sander C., Schmulevich I., Schwikowski B., Warner G. J., Ideker T., Bader G. D. (2007) Nat. Protoc. 2, 2366–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zordan R. E., Miller M. G., Galgoczy D. J., Tuch B. B., Johnson A. D. (2007) PLoS Biol. 5, e256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fernandes L., Rodrigues-Pousada C., Struhl K. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6982–6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alarco A. M., Raymond M. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 700–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alarco A. M., Balan I., Talibi D., Mainville N., Raymond M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 19304–19313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yang X., Talibi D., Weber S., Poisson G., Raymond M. (2001) Yeast 18, 1217–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hsu P. C., Yang C. Y., Lan C. Y. (2011) Eukaryot. Cell 10, 207–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jung W. H., Saikia S., Hu G., Wang J., Fung C. K., D'Souza C., White R., Kronstad J. W. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schrettl M., Beckmann N., Varga J., Heinekamp T., Jacobsen I. D., Jöchl C., Moussa T. A., Wang S., Gsaller F., Blatzer M., Werner E. R., Niermann W. C., Brakhage A. A., Haas H. (2010) PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fujii Y., Shimizu T., Toda T., Yanagida M., Hakoshima T. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 889–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pu W. T., Struhl K. (1991) Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 4918–4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Natarajan K., Marton M. J., Hinnebusch A. G. (2007) in Methods for General and Molecular Microbiology (Reddy C. A., Beveridge T. J., Breznak J. A., Snyder L., Schmidt T. M., Marzluf G. A. eds) pp. 978–994, ASM Press, Washington, D. C [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bowtell D., Sambrook J. (2003) DNA Microarrays: A Molecular Cloning Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 68. Shakoury-Elizeh M., Protchenko O., Berger A., Cox J., Gable K., Dunn T. M., Prinz W. A., Bard M., Philpott C. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14823–14833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Martchenko M., Alarco A. M., Harcus D., Whiteway M. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 456–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]