Abstract

We describe the methods used in our laboratory for the analysis of single nucleic acid molecules with protein nanopores. The technical section is preceded by a review of the variety of experiments that can be done with protein nanopores. The end goal of much of this work is single-molecule DNA sequencing, although sequencing is not discussed explicitly here. The technical section covers the equipment required for nucleic acid analysis, the preparation and storage of the necessary materials, and aspects of signal processing and data analysis.

1. Background: Analysis of Nucleic Acids with Nanopores

Nanopores have been used to detect and analyze single molecules (Bayley and Cremer, 2001; Branton et al., 2008; Deamer and Branton, 2002; Dekker, 2007) and to investigate reaction mechanisms at the single-molecule level (Bayley et al., 2008b). In this article, we focus on the analysis of nucleic acids with the protein pore formed by staphylococcal α-hemolysin (αHL). First, we present background on the wide variety of experiments that can be performed on nucleic acids. Second, we enlarge on technical aspects of these experiments that have proved useful in our laboratory.

In a nanopore experiment, a single pore is located in a thin barrier that separates two compartments (here called cis and trans) containing aqueous electrolyte. An electrical potential is applied across the barrier and the flow of ions through the nanopore is monitored. Molecules of interest are investigated by analyzing the associated modulation of the ionic current when the molecules pass through the pore or interact with the lumen (Fig. 1A). In this way, information about the length of nucleic acid molecules and their base compositions is gathered. Duplex formation and dissociation, including unzipping in an applied potential, can be examined. The properties of enzymes and binding proteins associated with nucleic acids can also be determined. Stemming from this work, there is the potential to develop a cheap and fast technology to sequence single DNA molecules (Branton et al., 2008), but we do not emphasize the latter here.

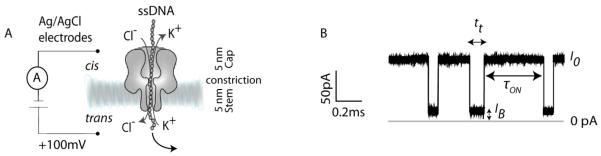

Figure 1.

Nanopore analysis of DNA. (A) Ag/AgCl electrodes are used to apply a potential (e.g. +100 mV) to drive DNA through an αHL nanopore and to measure the ionic current. (B) Typical trace for DNA translocating through a WT-αHL nanopore showing the translocation times (tt), the residual current value (IB), and the interevent intervals (tON) for individual DNA translocation events.

The two most common classes of nanopores are protein pores in lipid bilayers (Fig. 1) or synthetic nanopores formed in a variety of thin films, including Si-based materials, PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane) and polycarbonate (Dekker, 2007; Rhee and Burns, 2007; Sexton et al., 2007). Among the advantages of synthetic nanopores are that their dimensions can be adjusted during manufacture and that they can be produced as nanopore arrays. Protein nanopores also have significant advantages; in contrast with synthetic nanopores, their dimensions can be readily reproduced and their structures can be precisely manipulated by site-directed mutagenesis and targeted chemical modification. The stability of solid-state pores in harsh environments is often mentioned as a key advantage, but it should be noted that the αHL pore can withstand denaturants (Japrung et al.), extremes of pH (Maglia et al., 2009b) and temperatures up to ~95°C (Kang et al., 2005), conditions adequate for the analysis of DNA.

Although we focus on the analysis of nucleic acids with the αHL nanopore, progress on DNA analysis with alternative protein pores is being made, notably MspA from Mycobacterium smegmatis (Butler et al., 2008). The experimental principles developed for αHL are valid in other cases.

1.1. Structure of the αHL Nanopore

αHL is a heptameric protein that consists of a stem domain and a cap domain (Fig. 1) (Song et al., 1996). The stem domain comprises 14 anti-parallel β strands (two per protomer) that form a roughly cylindrical water-filled pore of ~2-nm internal diameter. The internal cavity, or vestibule, within the cap domain is roughly spherical with an internal diameter of ~4.5 nm. The narrowest part of the interior of the pore is the constriction (1.4 nm in diameter), which is located between the cap and the stem domains. Under an applied potential, ions flow through the pore and the addition of ssDNA to one side of the bilayer (typically the cis side) produces current blockades during the periods when the DNA molecules enter the pore (Fig. 1). Entry can result in a brief visit and then exit from the same side or translocation from the cis to the trans side of the bilayer. The dimensions of the pore are such that dsDNA cannot pass through it (Kasianowicz et al., 1996), although dsDNA can penetrate as far as the constriction when presented from the cis side (Maglia et al., 2009b; Vercoutere et al., 2001). While we most often refer to DNA in this review, the same principles apply to RNA analysis.

1.2. Nucleic Acid Analysis with αHL Nanopores

In electrical recordings from planar bilayers, it is important that sign conventions are followed consistently. We use the following. The cis chamber is that to which the protein nanopore is added. The cis chamber is at ground and the transmembrane potential is given as the potential on the trans side (i.e. the trans potential minus the cis potential; the latter is “zero” in the present case). A positive current is one in which positive charge (e.g. K+) moves through the bilayer from the trans to the cis side, or negative charge (e.g. Cl−) from the cis to the trans side.

The information that can be extracted from a typical electrical recording of DNA translocation through an αHL nanopore is the mean translocation time (t̄t), the residual current level during translocation (I%RES) and the mean interevent interval (t̄ON), which is the inverse of the frequency of events (f), when t̄ON is >> t̄t (Fig. 1B).

Translocation times of short single-stranded oligonucleotides (less than 100 nt) are described well by a Gaussian distribution with an exponential tail. The most probable translocation time (tP) is given by the peak of the distribution (Meller et al., 2000). At +120 mV and 25°C, the DNA moves through the pore at a speed of 1 to 6 μs per base (tP divided by the number of bases). The speed depends on the base composition of the nucleic acid, with purine bases showing the shortest translocation times (Meller, 2003). In addition, tP decreases exponentially with the temperature or the applied potential (Meller et al., 2000).

The frequency of occurrence of DNA translocation events increases with increased applied potential (Henrickson et al., 2000), temperature (Meller et al., 2000) or salt concentration (Bonthuis et al., 2006). In addition, a threshold potential must be exceeded to observe DNA capture (Henrickson et al., 2000) and even then capture is inefficient. Rough estimates suggest that, at voltages close to the threshold, about one DNA molecule in every 1,000 that collide with the WT-αHL pore is captured (Meller, 2003). By contrast, at the highest accessible applied potentials (around +300 mV), ~20% of the collisions results in DNA translocation (Nakane et al., 2002). However, the frequency of DNA capture can be improved by increasing the number of internal positive charges within the pore by site-directed mutagenesis, which also reduces the threshold for DNA translocation through both the αHL (Maglia et al., 2008) and MspA (Butler et al., 2008) nanopores. The most likely mechanisms for the increased frequency of translocation are a strengthened interaction when DNA molecules sample the interior of the pore, increased electroosmotic flow, or a combination of the two that depends on the applied potential (Maglia et al., 2008).

If nanopores are to be used to sequence DNA, single bases will most likely be identified at a recognition point within the nanopore by the extent to which they reduce the ionic current, rather than their dwell times (Bayley, 2006). Therefore, if a large current flows during DNA translocation (IB), the recognition of the bases is likely to be improved. The percent residual current (I%RES = IB/IO × 100) shows less experiment-to-experiment variation than the residual current (IB) and therefore it is the descriptor of choice. ΔI%RES, the difference in I%RES between residual currents (e.g. for two different DNAs), shows less variation still (Stoddart et al., 2010). WT-αHL nanopores generally show relatively low I%RES values (typically 10% in 1 M KCl, at +120 mV), which depend on the nucleic acid used, with RNA generally blocking more current than DNA (Meller, 2003). I%RES increases with increased applied potential (Stoddart et al., 2009) and salt concentration (Bonthuis et al., 2006). Recent studies have shown that I%RES also depends on the amino acid side chains that project into the lumen of the pore (Maglia et al., 2008; Stoddart et al., 2009). At +120 mV, additional positively charged residues in the barrel decrease IB by 60 to 80% relative to WT αHL depending on the positioning of the charge (Maglia et al., 2008), while the elimination of ionic interactions and the reduction of side-chain volume at the constriction, in the mutant E111N/K147N, increase IB by more than two-fold (Stoddart et al., 2009).

1.3. Homopolymeric Strand Analysis with Protein Nanopores

Homopolymeric ssDNA or ssRNA blockades can be discriminated with WT-αHL nanopores by means of their residual currents (IB) and translocation times (tP). In 1 M KCl and at +120 mV, poly rA blockades show an I%RES of 15% and a tP value of 22 μs per base, which are readily distinguished from poly rC blockades (I%RES = 9% and 5%, and tP = 22 μs per base) and from poly rU blockades (I%RES = 15% and tP = 1.4 μs per base) (Akeson et al., 1999). The DNAs, poly dA and poly dC, show different translocation times (tP = 1.9 and 0.8 μs per base, respectively), but similar I%RES values (12.6% and 13.4%, respectively) (Meller et al., 2000), while poly dU shows longer blockades than both poly dC and poly dA (Butler et al., 2007). Although a fully convincing explanation has yet to be proposed, differences in translocation times and IB value of homopolymeric strands through αHL nanopores have been associated with differences in base pair-independent secondary structure and base stacking (Akeson et al., 1999; Meller et al., 2000).

The different extents of current blockade associated with homopolymeric RNA strands was exploited to detect the transition from poly rA to poly rC segments within the same molecule. When the translocation of poly rA30C70 through the WT-αHL nanopore was investigated, ~50% of the events exhibited current steps that reflected the transition (Akeson et al., 1999).

The translocation speed is constant for short DNAs (from 12 to 100 bases) (Meller and Branton, 2002; Meller et al., 2001) and for poly rU from 100 to 500 bases (Kasianowicz et al., 1996). For oligonucleotides shorter than the length of the barrel (N <12), the translocation speed decreases with increasing nucleotide length in a non-linear fashion. Polynucleotides longer than 500 bases have not yet been carefully characterized.

1.4. Recognition of Specific Sequences and Single Base Mismatches through Duplex Formation

αHL pores have been used to recognize specific DNA sequences and single nucleotide mismatches through duplex formation. Howorka et al. covalently attached an 8-base oligonucleotide within the vestibule of an αHL pore. The complementary strand was then recognized by measuring the current blockade provoked by strand hybridization (Howorka et al., 2001). Single nucleotide mismatches were identified because they produced shorter current blockades. Based on duplex lifetimes, the DNA-nanopores were able to discriminate mismatches between the oligonucleotide tethered to the pore and complementary 8-base sequences within DNA strands of up to 30 nucleotides. In addition, the last three bases in a nine-base DNA attached to the pore were sequenced by the sequential addition of known oligonucleotides (Howorka et al., 2001). Vercoutere et al. detected single-base differences in short, blunt-ended DNA hairpin molecules with up to 9 complementary bases. The entry of the hairpins into the vestibule of the αHL pore was accompanied by a characteristic current blockade. Once in the vestibule, the hairpins spontaneously dissociated and a current spike signaled the translocation of the DNA strand through the pore. Single-base mismatches were detected by reduced duplex life-times, which reflected the stabilities of the duplexes in solution (Vercoutere et al., 2001). Nakane et al. used streptavidin to immobilize a biotinylated probe DNA molecule within the αHL pore (Fig. 3). The untethered end of the DNA strand entered the trans compartment at positive potentials, where it bound a complementary oligonucleotide to form a rotaxane. Reversal of the applied potential exerted a force on the duplex. A shorter mean time for dissociation by comparison with the value for a fully complementary pair was used to recognize single mismatches in probe-oligonucleotide duplexes (Nakane et al., 2004).

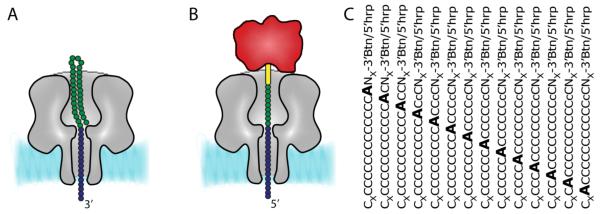

Figure 3.

Single base recognition in immobilized DNA strands. (A) The translocation of a DNA strand can be arrested by using a terminal DNA hairpin. (B) Alternatively, the translocation of a biotinylated (yellow cylinder) DNA strand can be halted by pre-incubating the ssDNA with streptavidin (red). The green circles indicate the DNA that is in the vestibule and the blue circles are the DNA bases that span the barrel of the pore. (C) The barrel of the pore can be sampled by measuring the current blockades provoked by DNA sequences in which the location of a single base is moved within an otherwise identical background. Hrp, hairpin; Btn, biotinylated linker; NX, nucleotides that are in the vestibule of the pore; CX, nucleotides that protrude through the trans entrance of the pore.

1.5. Individual Base Recognition by αHL Nanopores

The recognition of individual DNA bases during translocation is crucial if the sequencing of DNA molecules is to be achieved by using nanopores. However, at present, the translocation of nucleic acids through αHL nanopores is so rapid (1 to 6 μs per base) that only artificially bulky bases (Mitchell and Howorka, 2008) or the transition between homopolymer stretches of ~30 nt can be detected (Akeson et al., 1999). Therefore, to test the feasibility of base detection, DNA strands have been immobilized within the αHL pore by using terminal hairpins (Ashkenasy et al., 2005) (Fig. 3). Because the hairpin might interfere with recognition (Fig. 3A), recent work has exploited the interaction between a biotinylated oligonucleotide and streptavidin to immobilize DNA strands (Purnell and Schmidt, 2009; Stoddart et al., 2009) (Fig. 3B). In our work, the ability of the αHL pore to discriminate individual bases was investigated by sampling several DNA molecules in which the position of a single base was altered in an otherwise identical homopolymeric background (Fig. 3). While Ghadiri and co-workers were able to identify a recognition point at the trans entrance of the nanopore that could discriminate a single dA in a poly dC background (Ashkenasy et al., 2005), the biotinylated oligonucleotides were used to sample the entire length of the pore (Stoddart et al., 2009). αHL was found to contain three broad recognition sites. When an engineered pore (E111N/K147N) was used, with enhanced current flow when DNA occupies the pore (IB), all four DNA bases could be distinguished in a poly dC background. Individual base differences could also be detected in a heteropolymeric DNA strand (Stoddart et al., 2009).

1.6. Control of DNA Translocation through Nanopores

Controlling the speed at which DNA translocates through a pore is perhaps the single most important challenge that has to be overcome in nanopore sequencing (Branton et al., 2008). At high sampling rates, noise levels are too high for base discrimination. A recent paper estimates that 98% of the small current differences observed for the four DNA nucleotides could be discriminated by an αHL nanopore assuming a mean dwell time of 10 ms (Clarke et al., 2009), but this is at least three orders of magnitude longer than the transit time for individual bases in freely translocating ssDNA. Several attempts have been made to reduce the translocation speed. For example, it has been shown recently that increasing the viscosity of the sample solution by adding 63% (v/v) glycerol to the aqueous electrolyte can slow down DNA translocation through αHL nanopores by more than an order of magnitude, but at the expense of a ten-fold decrease in the unitary conductance of the pore (Kawano et al., 2009). In efforts to increase the local viscosity, but preserve the conductance of the pore, a positively charged dendrimer with a hydrodynamic volume of 4.2 nm (Martin et al., 2007) and uncharged PEG molecules of similar size (G. Maglia, unpublished) were covalently attached inside the vestibule of the αHL pore. The modified nanopores showed a conductance that was roughly half that of the WT-αHL pore. However, both polymers almost completely inhibited the passage of nucleic acids through the pore, rather than slow their movement. Attempts to engineer the internal positive charge of the αHL pore to form “molecular brakes” to reduce the speed of ssDNA translocation have also been made (Rincon-Restrepo, in preparation). Modified versions of the pore were prepared with up to seven internal rings of seven arginine residues. Although the translocation speed was reduced by more than two orders of magnitude, the resulting IB values were too low to allow discrimination of individual bases. Optical and magnetic traps have also been used to move DNA strands through solid state nanopores (Keyser et al., 2006; Peng and Ling, 2009), but so far these have been long double-stranded DNAs. Due to the instability of the lipid bilayer and the diffusion of nanopores within it, these techniques cannot be easily implemented with biological nanopores.

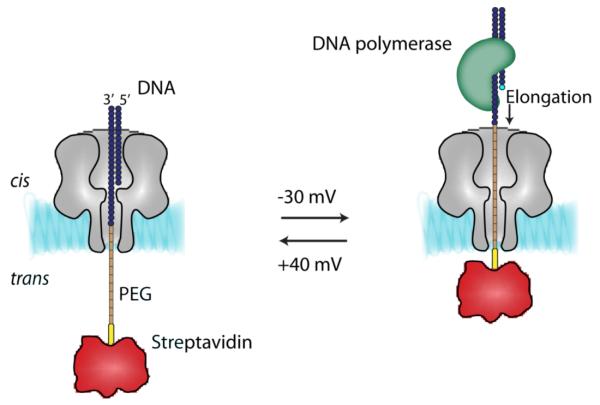

Ultimately, DNA processing enzymes will most likely be used to control DNA translocation through biological pores. ExoI·ssDNA complexes gave current blockades that were approximately five-fold longer and showed a higher IB value than the current blockades produced by free ssDNA under the same conditions (+180 mV, 1 M KCl) (Hornblower et al., 2007). The disappearance of the long current blockades after the addition of Mg2+, which triggers the activity of the enzyme, confirmed that these blockades were due to DNA in ExoI·ssDNA complexes entering the nanopore. But, the enzymatically driven movement of DNA was not demonstrated in this work. In a similar approach, the interaction of RNA with the αHL pore was monitored in the presence of P4 ATPase, a motor protein from bacteriophage φ8, but again the movement of the nucleic acid could not be shown (Astier et al., 2007). Recently, the activity of a DNA polymerase was monitored with single base resolution by using an αHL nanopore (Cockroft et al., 2008). A DNA strand was immobilized within the pore by threading a streptavidin·biotin-phosphoPEG-ssDNA polymer through the trans entrance in a negative potential (Fig. 4). DNA primers (to form a rotaxane) and TopoTaq DNA polymerase were then added to the cis side and single-nucleotide primer extensions were identified by the current changes caused by the movement of phospho-PEG into the barrel of the pore after the addition of dNTPs (Fig. 4). Up to nine successive steps were observed by switching the potential between −30 mV (a potential at which elongation was possible) and +40 mV (the potential used to monitor the elongation steps). Future efforts will be directed towards combining such an elongation device with an engineered αHL pore capable of base identification.

Figure 4.

Single nucleotide extension monitored with a protein nanopore. (Left) The monitoring configuration. A phospho-PEG sequence occupies a fraction of the barrel of the αHL pore and modulates the ionic current to a level that depends on the extent to which the primer has been elongated. (Right) Elongation configuration. dsDNA is accessible to the DNA polymerase. Elongation by a single nucleotide (light blue circle) is controlled by the identity of the dNTPs in solution. The activity of the DNA polymerase can be monitored by stepping the potential between +40 mV and −30 mV.

2. Methods: Electrical Recording with Planar Lipid Bilayers

Protein nanopores employed for DNA analysis must be reconstituted into artificial bilayers that mimic biological membranes. We carry out our experiments with planar lipid bilayers, examining single channels under in vitro conditions where all the constituents of the system are carefully controlled. Single-channel experiments require sensitive equipment to measure the small currents passed by single protein pores. There is a wealth of good literature detailing the various aspects of setting up such equipment and carrying out experiments on single protein channels and pores (The Axon guide: www.moleculardevices.com/pages/instruments/axon_guide.html) (Hanke and Schlue, 1993; Miller, 1986; Sakmann and Neher, 1995), so here we just cover the specific apparatus and procedures employed in our laboratory for examining the interaction of DNA with the αHL pore.

2.1. Electrical Equipment

Single-channel electrical measurements can be carried out with a range of equipment, both commercial and custom built. We use Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifiers (Molecular Devices) with 16-bit digitizers (132x or 1440A, Molecular Devices). DNA measurements are typically acquired in voltage-clamp mode using resistive WHOLE-CELL (β = 1) headstage settings. In voltage-clamp mode, the applied voltage is fixed, and the transmembrane current required to maintain that voltage is measured. Voltage clamping does not mimic a process found in nature, but many of the interactions of DNA with the αHL pore are voltage dependent, so it is imperative to control the applied potential. Furthermore, in this mode no capacitive transients are produced (except when changing the applied voltage), and the current flow is proportional to the conductance of the channels.

The Axopatch 200B has a recording bandwidth of 100 kHz, and the digitizers have a maximum sampling rate of 250 kHz (4 μs) per channel, which determines the maximum temporal resolution. Amplitude resolution is primarily limited by the noise in the system. Planar bilayers are prone to relatively high background current noise (e.g. >1pA RMS at 10 kHz) that can obscure small current steps (The Axon guide) (Mayer et al., 2003; Wonderlin et al., 1990). Signal-to-noise can be improved by applying low-pass filtering, at the expense of a loss of temporal resolution. Therefore, although theoretically the electronics can acquire in the microsecond regime (freely translocating DNA passes at ~1 to 6 μs per base), in practice there is a balance between acquiring fast enough to observe the events of interest, and low-pass filtering to observe small amplitude current differences.

There are three main sources of internal noise in a planar bilayer system, in increasing order of magnitude (The Axon guide) (Mayer et al., 2003; Wonderlin et al., 1990): (A) noise originating in the acquisition electronics; (B) noise from clamping the thermal noise currents in the access resistance (i.e. the resistance of the solutions and electrodes in series with the bilayer) across a large capacitance bilayer; and (C) noise from the nanopore itself. There are various strategies for reducing noise that are well covered in the literature (The Axon guide) (Mayer et al., 2003; Wonderlin et al., 1990). Access resistance can account for substantial noise in planar bilayer systems in the absence of a pore (Wonderlin et al., 1990). The access resistance can be reduced by (1) using higher salt solutions in the cis and trans compartments; (2) using larger area electrodes; and (3) reducing the resistance of the agar bridges (discussed later). The use of suitable aperture materials is also important for reducing dielectric noise (e.g. PTFE films produce lower noise than some other plastics (Mayer et al., 2003; Wonderlin et al., 1990). However, the single most effective means of reducing noise in the absence of a pore is to reduce the size of the bilayer and hence its capacitance (The Axon guide) (Mayer et al., 2003; Wonderlin et al., 1990). Nevertheless, the largest source of noise is from the protein pore itself. Protein-derived noise arises from extremely fast fluctuations in conformation and charge states inside a pore (Bezrukov and Kasianowicz, 1993; Korchev et al., 1997). The noise is dependent on physical conditions (pH, temperature, salt concentration, etc.), but for αHL we typically observe RMS noise that is two to three times greater than the noise from the bilayer alone.

2.2. Faraday Enclosure

Electrical recording experiments should be carried out in a conducting enclosure (a Faraday cage) to isolate the sensitive measurements from external radiative electrical noise. We typically use steel or aluminum boxes ~50×50×50 cm in dimensions with rigid side walls >1 mm thick. The boxes are grounded via the common ground in the patch clamp amplifiers (www.moleculardevices.com). Vibration isolation is an important consideration (The Axon guide). External noise (e.g. from heavy machinery) can be transmitted through a laboratory bench into the box and result in substantial noise in the signal. Therefore, we mount our Faraday boxes on pneumatic anti-vibration tables or soft supports (e.g. partially inflated soft rubber tubing). Unfortunately, anti-vibration tables do little to prevent sensitivity to environmental noise (i.e. loud noises, or even talking), as the large surfaces of the boxes pick up vibrations in the air. Although the Faraday cage might be housed inside an acoustically isolated enclosure, this source of noise can simply be eliminated by using a box with absorbent walls that are well damped against vibrations. Finally, it is essential that the electrodes within the box are (a) as short as possible (to reduce access resistance, input capacitance and the reception of radiated noise) and (b) firmly secured to prevent their vibration.

While a Faraday cage is effective at isolating the system from external noise, care must be taken not to introduce internal sources of noise. As a result, any internal equipment (e.g. stirrers, peltier heaters, etc.) needs to be carefully shielded and should ideally run off a DC battery inside the Faraday cage.

2.3. Preparation of Electrodes

Ag/AgCl electrodes are the most commonly employed in bilayer recording due to their long-term chemical stability, reversible electrochemical behavior, predictable junction potentials and superior low noise electrical performance. However, it should be noted that Ag/AgCl electrodes only perform well in solutions containing chloride ions. For experiments involving asymmetric solutions (where the chambers contain chloride ions at different concentrations) an agar bridge (as discussed later) is recommended to prevent substantial liquid junction potential offsets (The Axon guide).

Ag/AgCl electrodes are typically prepared from Ag wire by either (a) electroplating in HCl solution, (b) dipping in molten AgCl, or (c) treatment with a weak hypochlorite solution (The Axon guide) (Purves, 1981). Our preferred approach is an overnight treatment with hypochlorite, as this produces long lasting electrodes with a thick coating of AgCl. We make our electrodes from 1.5 mm diameter silver wire (>99.99%, Sigma Aldrich), using lengths of ~10 mm (Fig. 5). These electrodes have a large reactive surface area, which prolongs their working life and minimizes the access resistance. Before treatment, the electrodes are thoroughly cleaned and roughened by abrasion (e.g. with a wire brush or glass paper), and then immersed in 1 to 5% NaClO in water. After treatment, the electrodes are rinsed with distilled water. The electrodes are prepared and stored in the dark to prevent UV conversion of AgCl back to Ag. In our experience, good electrodes have a rough texture and a dull grey color (Fig. 5).

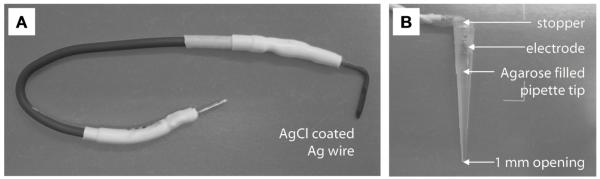

Figure 5.

Ag/AgCl electrodes A) Photograph of a Ag/AgCl electrode, prepared by hypochlorite treatment of a short piece (~10 mm) of 1.5 mm-diameter Ag wire (soldered onto standard electrical wire). B) When agar bridges are required, we incorporate our electrodes into 200 μL pipette tips filled with agar (3% w/v, 3 M KCl in unbuffered ddH2O), sealing the top with a rubber stopper and parafilm.

The use of a 3 M KCl/ agar bridge between an electrode and the chamber solution is recommended for all experiments, but in particular for experiments carried out under asymmetric salt conditions to reduce junction potential offsets. The 3 M KCl filling solution also reduces the access resistance. Another advantage of the agar bridge is that it prevents Ag+ ions from the electrode leaching into the solution, which can adversely affect the activity of some protein pores. To create the agar bridges, we incorporate our 1.5 mm Ag/AgCl electrodes into 200 μL pipette tips (Gilson, U.S.A.) filled with (initially) molten agar (3% w/v low melt agarose in 3 M KCl in pure water), with a rubber stopper as a seal (Fig. 5). In addition, the opening of the pipet connecting to the bulk chamber solution should not be too small (we recommend an opening of >1 mm diameter).

Immediately before use, the electrodes are electrically balanced in symmetric solutions of the experimental buffer (e.g. 1 M KCl, 25 mM Tris.HCl, pH 8.0) by using the pipet offset function on the patch-clamp amplifier. Little to no potential adjustment is required for good electrodes. A sign of poor or degraded electrodes is the development of white patches and a requirement to re-balance the potential offset.

2.4. Chambers

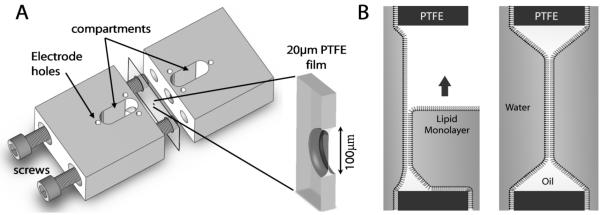

We use open planar bilayer chambers for the majority of our DNA experiments. However, in some cases, in particular where limited quantities of reagents are available, we also make use of droplet interface bilayers that have solution volumes of <200 nL (Bayley et al., 2008a). Open chambers come in a wide variety of shapes and formats, with vertical or horizontal bilayers and solution volumes ranging from 50 μL to 1 mL. Although commercial options are available (e.g. Warner Instruments), we use custom vertical bilayer devices machined from Delrin (Fig. 6), where the two compartments of 0.5 to 1.0 mL are separated by a 20 μm-thick PTFE film (Goodfellow UK). In this format, both the cis and trans solutions are easily accessed for the purposes of adding reagents or perfusion.

Figure 6.

Planar bilayer formation. A) We use custom vertical planar bilayer chambers, with two 1 mL compartments separated by a 20-μm PTFE film, shown here in an exploded view. The two halves are fastened together with screws, clamping the PTFE film between them. The apparatus is sealed with silicone glue (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) at to ensure water-tightness. The PTFE film contains a central aperture ~100 μm diameter, across which the bilayer is formed. B) The bilayer is formed by the Montal-Mueller method. The aperture is pre-treated with an oil (e.g. hexadecane), and the bilayer is then formed by flowing Langmuir-Blodgett lipid monolayers over both sides of the aperture.

The only path between the two compartments is a central aperture in the PTFE film across which the bilayer is formed (Fig. 6A, enlargement). The diameter depends on the size of bilayer required, and is typically ~100 μm. While there are many approaches for producing small apertures (Wonderlin et al., 1990), we favor ‘zapping’ the films with a custom high-voltage spark generator (producing a spark ~15 mm long at a frequency of ~1 Hz). Commercial products are available (e.g. Daedelon, USA). To control the location of the aperture, the Teflon film is weakened at the desired point by gently pricking with a sharp needle. The spark passes through this weakness, and the high temperature causes localized melting, which produces a perfectly round aperture. The aperture is sparked several times until the desired diameter is achieved (as measured under a microscope with a graticule). This technique produces high quality apertures with reproducible dimensions (typically >50 μm and ±10 μm) (Mayer et al., 2003).

Reducing bilayer size, and hence capacitance, reduces noise. However, this must be balanced against the practical necessity of creating bilayers reproducibly (bilayers that are too small are often occluded by enlargement of the annulus) and the difficulty of inserting channels into overly small bilayers. A good compromise is to use bilayers with a capacitance of ~60-100 pF, which corresponds to a diameter of ~105-135 μm (DPhPC/hexadecane, assuming a specific capacitance of 0.70 μF cm−2, (Peterman et al., 2002)).

2.5. Preparing Bilayers

Planar bilayers are typically created across small apertures in a plastic film by variants of two main approaches (White, 1986). In the first, the membrane is created by directly painting a lipid/oil solution (e.g. 5% w/v of DPhPC in hexadecane) around the aperture before adding the aqueous solution. This thick lipid/oil film spontaneously thins and after a few minutes forms a bilayer due to Plateau-Gibbs suction (Niles et al., 1988). In the second approach, the aperture is first pre-treated with the oil (e.g. hexadecane), and then the bilayer is formed by flowing Langmuir-Blodgett lipid monolayers across both sides of the aperture (Fig. 6B) (Montal and Mueller, 1972; White et al., 1976). In both approaches, the oil (e.g. an n-alkane such as decane or hexadecane) is extremely important, as it creates an annulus around the rim of the aperture, which allows the bilayer to form an interface with the plastic film (Plateau-Gibbs border). We favor the second “Montal-Mueller” approach. The primary advantages of this technique are that the bilayers are quick to form (with the painting approach it can take tens of minutes for the bilayer to spontaneously thin), and asymmetric bilayers can be created if the two compartments contain lipids of a different composition.

Briefly, we pre-treat the aperture with hexadecane by the direct application of a single drop (~5 μL) of 10% hexadecane in pentane. After the pentane has evaporated, both compartments of the chamber are filled with the buffered aqueous electrolyte and the electrodes are connected. The aperture should be free of excess oil, so that an electrical current can be measured between the compartments. (At zero applied potential on the amplifier, there remains a very small potential difference between the compartments). In the case of blockage, excess oil can be removed by gently pipetting solution at the aperture. A small drop (~5 μL) of lipid in pentane solution (e.g. DPhPC, 10 mg mL−1) is then applied directly to the top of the aqueous phase. After waiting ~1 min for the pentane to evaporate fully, solution is pipetted from the bottom of a compartment to lower the lipid monolayer at the water-air interface past the aperture level. The solution level is then slowly raised back above the aperture. After repeating this procedure several times in each compartment, a bilayer forms, and the electrical current drops to zero. We measure the capacitance, as described later, to judge the size and quality of the bilayer.

We use DPhPC bilayers with hexadecane as the oil in most of our studies. DPhPC has ideal bilayer forming properties. It exists in the fluid lamellar phase across a wide temperature range (−120°C to +120°C) (Hung et al., 2000; Lindsey et al., 1979), and it is stable to oxidation. Planar bilayers can however be prepared from a wide range of phospholipids or phospholipid mixtures. These can have zwitterionic or charged headgroups, and may contain additives such as cholesterol. The correct lipid mixture may be essential for certain proteins to function (e.g. mechano-sensitive channels (Phillips et al., 2009)). The phospholipid mixture usually, but not always (Krasne et al., 1971), has fluid lamellar properties under the conditions of the experiment. Many oils can be used to interface the bilayer with the aperture (n-alkanes, squalene etc), but experimentalists should be aware that the shorter chain n-alkanes (e.g. decane) interdigitate into the bilayer leading to increased bilayer thickness (White, 1975; White, 1986). Although this is not important for a robust pore such as α-hemolysin, bilayer thickness differences can affect the properties of membrane proteins (Phillips et al., 2009). Hexadecane produces bilayers with little oil content (White, 1975; White, 1986).

A standard cleaning routine is used between experiments: first rinsing with large amounts of water, then repeated steps of distilled water rinses followed by 100% ethanol rinses. Finally, the chambers are thoroughly dried under a stream of nitrogen. When required, we also employ detergent washing steps, NaOH (1 M) or HCl (1 M) washes, or rinsing with an EDTA solution (e.g. 10 mM) to remove traces of divalent metal ions.

2.5.1. Bilayer Stability

The planar bilayers we have described typically have lifetimes of a few hours and can withstand constant applied potentials of 200 to 300 mV. Smaller bilayers (<100 μm diameter) are much less susceptible to pressure variations and mechanical shock, and are therefore longer lived. DPhPC bilayers are stable up to ~100°C (Kang et al., 2005). In certain cases, alternative oils should be used. For example, hexadecane is frozen below 18°C, and hexadecene or shorter chains alkanes can be employed at low temperatures. Planar bilayers are also able to withstand substantial osmotic gradients arising from the use of asymmetric salt conditions (we often use asymmetric solutions of 150 mM /1 M salt to measure ionic charge selectivity), although the solutions can be balanced if instability occurs by the addition of an osmolyte (e.g. sucrose) to the low-salt compartment.

2.5.2. Measuring Bilayer Capacitance

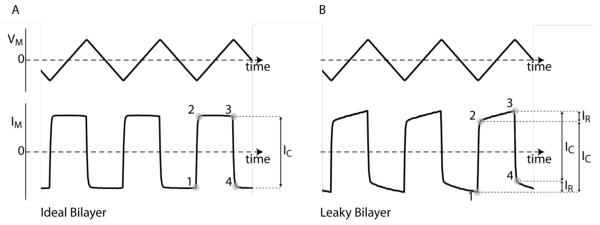

It is important to measure bilayer capacitance, because pores will not insert into misformed bilayers. There are a number of ways of determining capacitance (for reviews see (Gillis, 1995; Kado, 1993). One of the most versatile and straightforward is the application of voltage ramps to elicit constant capacitive currents (Fig. 7). Since current (I) is proportional to the rate of change of voltage (dV/dt) for a capacitor (I = C×dV/dt), an applied triangular voltage waveform produces a square-wave current output (i.e. dV/dt = constant, for each sweep), which can be used to determine bilayer capacitance (IC in Fig. 7). We use commercial analog waveform generators, inputing a triangular wave (~20 Hz) into the patch-clamp amplifier (front-switched input on an Axopatch 200B amplifier). We directly calibrate the input waveform by using a 100 pF bilayer model cell (MCB-1U, Molecular Devices), so that 100 pA = 100 pF. This approach provides a visual measurement of capacitance, which is useful for determining the quality of a bilayer seal (leaks are readily apparent as a triangular deviation from the ideal square wave output (IR in Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Measuring bilayer capacitance. A triangular-wave voltage input applied across a capacitor produces a square-wave current output. (A) Bilayer capacitance can be determined by measuring the peak-to-peak magnitude of the square-wave current output (IC). (B) A leak in the bilayer is visualized by the triangular ohmic deviation (IR) from the ideal square-wave (a small leak current is shown in this example).

2.6. Inserting Pores and Adding DNA

In the case of αHL, there are several ways to insert the pore into a planar bilayer. αHL is a toxin that assembles spontaneously from water-soluble monomers, so pores can be formed by adding monomeric αHL directly to the chamber. However, it is often difficult to obtain a single channel by using this approach (many pores tend to insert if the monomer remaining after a single pore has formed is not removed by perfusion), and we also find that the αHL pores formed from monomers have substantial pore-to-pore variability (discussed later). We therefore prefer to use pre-oligomerized protein in a detergent-solubilized form (e.g. after extraction from an SDS-polyacrylamide gel as described below). Typically ~0.2 μL of SDS-solubilized heptamer (~1 ng μL−1) is manually ejected from a pipette very close to the bilayer beneath the surface of the solution in the cis compartment. The solution in the compartment is then stirred gently with a small magnetic stirrer bar until a single insertion event is observed. Electrical recordings are noisy while stirring, as the changing magnetic field produced by the rotating stirrer and stirrer bar induces currents in the electrodes, and stirring is discontinued for the rest of the experiment, unless additions are made to a compartment. Although the protein concentration can be reduced to improve the chances of obtaining a single insertion event, this often requires waiting a considerable length of time. Alternatively, a higher concentration of protein can be added to reduce the time to insertion, followed by prompt perfusion (see below) to remove free protein.

Two other methods of inserting protein employed in our laboratory are vesicle fusion (better suited to proteins that are unstable in detergent) (Morera et al., 2007) and direct introduction with probes (Holden and Bayley, 2005; Holden et al., 2006), which is also suited to unstable proteins or proteins of which only small quantities are available.

DNA, RNA or other analytes are added directly to the chamber solutions from stocks (typically 100 μM in ddH2O or TE buffer, pH 8.0) by pipet. Mixing is achieved by stirring the chamber solution for up to 1 min (using a 5 mm stirrer bar in the bottom of the compartment). Depending on the experiment, we typically add oligonucleotides to the 1 mL compartment solution from 100 μM stocks to give final concentrations of 10 nM to 2 μM. The electrode compartments may represent an appreciable dead volume (e.g. 5% of the total volume), which must be taken into account for quantitative work. Better still, the concentration of a DNA or RNA in a compartment should be checked after an experiment, e.g. by UV spectrometry.

2.7. Perfusion

We use perfusion to remove free protein from the bulk solution once a single pore has inserted, and to change the solution conditions or analytes in the system while retaining the same pore in the bilayer. We perfuse our devices by manual pipetting (removing some solution and replacing it with fresh solution) or with push-pull syringe drivers (e.g. PHD 2000, Harvard Apparatus) that exchange the solution at rates of ~1 mL min−1. It should be noted that solution-filled perfusion tubing entering the Faraday cage acts as an antenna and picks up radiative noise that can prevent useful recording while the perfusion equipment is connected. If this is a problem, drip-feed perfusion can be employed, where the air pocket breaks the electrical continuity in the tubing.

3. Nanopores

3.1. Nanopore Preparation

While monomeric αHL can be obtained commercially, we recommend the use of heptamers carefully prepared in the laboratory. This is of course essential for heteroheptamers with defined subunit combinations (Miles et al., 2002), but we have also found that pre-assembled homoheptamers give more consistent results than monomers in bilayer experiments.

In our laboratory, αHL homoheptamers used in single channel recording experiments are usually prepared from αHL monomers expressed by in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT). Heptamers are formed by incubating the monomers with rabbit red blood cell membranes and purified by SDS-PAGE (Cheley et al., 1999). The concentration of heptamer after purification is typically ~1 ng μL−1. Alternatively, if a higher concentration of protein is required (e.g. for a protein that inserts poorly (Maglia et al., 2009a)), αHL monomers can be expressed in E. coli or S. aureus bacterial expression systems (Cheley et al., 1997). In these cases, monomers are purified by ion exchange chromatography before incubation a surfactant (e.g. 6.25 mM DOC (Bhakdi et al., 1981; Tobkes et al., 1985)) to trigger the heptamerization process. Heptamers are then separated from monomers by size-exclusion chromatography (Cheley et al., 1997). These procedures are more laborious, but αHL heptamers at concentrations of 1 to 5 mg mL−1 can be obtained.

3.2. Nanopore Storage

αHL heptamers are usually stored at −80°C in 10 mM Tris.HCl buffer at pH 8.0, containing 100 μM EDTA. Heptamers prepared from monomers produced from bacterial expression systems will also contain surfactants (usually 1.25 mM DOC), while heptamers prepared from αHL monomers obtained by IVTT are likely to contain small amounts of polyacrylamide and SDS that are carried over from the SDS-PAGE purification. Polyacrylamide can be removed by using a small size-exclusion column (e.g. P30 Micro Bio-Spin chromatography columns, Bio-Rad), but it usually does not interfere with single-channel recording experiments.

To obtain single channels, protein solutions obtained after IVTT expression, assembly and electrophoretic purification are usually diluted ten-fold in buffer or ddH20, and 0.2 μL is added to the buffer in the planar bilayer chamber. At this point, residual SDS is well below its CMC. During an experiment, solutions containing αHL proteins are kept on ice. αHL preparations can be stored at 4°C for short-term use (less than a week), but the protein slowly loses activity. Multiple freeze/thaw cycles also reduce protein activity. When a reactive group is present (e.g. a cysteine residue), the protein must be handled with particular care and long-term storage at −80°C is usually limited to a few months.

3.3. Measurements with Nanopores

Purified WT heptamers form pores that have a high unitary conductance (~1 nS at +100 mV in 1 M KCl solution). WT-αHL pores show no gating events, openings and closings of the pore, unless the applied potential is high (more than ±180 mV), and even then the events are rare (generally less than 1 per minute). Pore-to-pore variation of the unitary conductance is generally within 5% of the mean. However, very occasionally (<5% of the cases), the pores show a high level of gating or have a dramatically reduced conductance. These cases probably arise from misfolded or misassembled heptamers and are discarded. αHL monomers, rather than purified heptamers, can also be used in single-channel recordings. However, a much greater number of the pores formed from monomers (from 20% to 50%, depending on the batch) show a reduced conductance or gating events. The use of heptamers purified by SDS-PAGE is therefore recommended. Over the course of long experiments (>30 min), the open pore current can drift due to evaporation of the solutions or exhaustion of the Ag/AgCl electrodes. It is recommended, therefore, always to use agarose bridges around the electrodes and to minimize the surface area of the solutions. If lids are used, care must be taken to prevent a short circuit through a film of electrolyte. Layers of oil can be placed on the surfaces of the chamber solutions, but then a complete clean-up will be required if the bilayer is reformed.

The αHL pore can be altered by site-directed mutagenesis to give improvements in f and IB. Alteration of the lumen of the αHL pore by site-directed mutagenesis generally produces nanopores that have similar unitary conductance values to that of WT αHL (Gu et al., 2001; Stoddart et al., 2009). Additional charges in the barrel, however, can alter the unitary conductance (IO) and rectification properties (Maglia et al., 2008), while the introduction of aromatic residues near the constriction (e.g. M113W and M113Y), or positively charged residues near the trans entrance (e.g. T129R and T125R) can produce pores that show a high frequency of gating (M. Rincon-Restrepo, unpublished data). In some cases, the gating events observed with nanopores that have additional positive charge in the barrel might be due to the binding of contaminants to the protein pore (Cheley et al., 2002) as they are more frequent at low salt concentrations when the charges within the pore are less well screened.

3.4. Nanopore Stability

αHL heptamers in bilayers are stable under extreme conditions of salt concentration, temperature (Kang et al., 2005) and pH (Gu and Bayley, 2000; Maglia et al., 2009b), and in the presence of denaturants (Japrung et al.). Pores can insert into bilayers and remain open over a wide range of ionic strengths (from 0.001 to 4 M KCl). Throughout this range, the conductance of the pore varies linearly with the ionic concentration of the solution, except at very low salt concentrations where there is a small deviation from linearity (Oukhaled et al., 2008).

Electrical recordings of αHL pores have been carried out from 4°C to 93°C (Kang et al., 2005). Over this range, the conductance of the pore increases roughly linearly, largely reflecting the temperature dependence of the conductivity of the electrolyte. DNA translocation experiments are usually carried out at room temperature, but lower temperatures can be used to reduce the speed of DNA translocation through the pore, by an order of magnitude over a range of 25°C at +120 mV (Meller et al., 2000), and high temperatures might be useful for denaturing DNA during translocation experiments.

Current recordings from αHL pores in symmetric solutions have been performed from pH 4 to pH 13 (Gu and Bayley, 2000; Maglia et al., 2009b). However, the rate of insertion of pre-assembled heptamers decreases dramatically at pH values greater than 11 and at pH > 11.7 αHL can no longer be transferred into planar lipid bilayers. CD and fluorescence experiments revealed that the cap domain of the protein is unfolded in 0.3% w/v SDS at pH 12, suggesting that correct folding of the cap is important for the insertion of αHL heptamers. Once in lipid bilayers, however, αHL pores appear to be more stable than in SDS solution and there is no evidence to suggest that the protein unfolds within the pH range tested. Therefore, to examine αHL at pH >11, the pores must be reconstituted at lower pH and the pH of the solution brought to the desired pH by adding small portions of 1 M KOH with stirring. The pH of the cis compartment (ground) can be monitored by using a pH electrode. However, measurement of the pH in the trans compartment provokes breaking of the bilayer, unless the trans electrode is removed or a conducting bridge is first formed with a Pt wire between the two compartments.

αHL pores are also stable in high concentrations of denaturants (e.g. up to 8 M urea), which has been used, for example, to investigate the translocation of unfolded polypeptides (Oukhaled et al., 2007) or to reduce the secondary structure of DNA for translocation (Japrung et al.). Since the insertion of αHL occurs only at concentrations of urea lower than 3 M, higher concentrations of denaturants are attained by replacing the buffer after a pore has inserted into a planar bilayer.

4. Materials

4.1. Buffer Components

Typically, DNA translocation experiments are carried out in 1 M KCl. Because of possible contaminants, the KCl and other buffer components should be of the highest possible purity. We use KCl from Fluka (catalog no. 05257) which contains less than 0.0005% of trace metals.

4.2. Preparation of DNA

In many experiments, synthetic DNAs and RNAs of 50 to 100 nt are used. The capture of these nucleic acids is relatively inefficient (e.g. ~4 s−1μM−1 at +120 mV with WT-αHL) (Henrickson et al., 2000; Maglia et al., 2008; Meller, 2003; Nakane et al., 2002). Therefore, DNA or RNA is usually presented at relatively high concentrations (more than 100 nM) and the use of small chambers can help conserve materials (Akeson et al., 1999). Nucleic acids, especially RNA, should be manipulated under nuclease-free conditions. Materials including water, tips and tubes should be autoclaved prior to use and the experimental area should be cleaned with a product such as RNaseZap (Ambion), to inactivate RNAse. RNaseZap may also be used on the chamber provided it is thoroughly rinsed afterwards. Purified RNA can be be stored in 50% formamide, which is known to protect RNA from degradation (Chomczynski, 1992).

4.3. Short Single-Stranded DNA or RNA

Several companies, such as Sigma Genesis, Integrated DNA Technologies and Bio-Synthesis, carry out the custom synthesis of nucleic acids of up to 200 nt in length for ssDNA and up to 50 nt for RNA at the micromole level. An advantage of using synthetic oligonucleotides is that they can be chemically modified at their 5′ or 3′ ends and that additional bases, such as 5′-methylcytosine, can be incorporated at specific sites. Pure oligonucleotides are essential for nanopore investigations and therefore they are usually desalted by the company, purified by HPLC or PAGE as appropriate for the length, and delivered as dried ethanol precipitates. We have also purified desalted short ssDNA (50-100 nt) and ssRNA (<50 nt) from Sigma Genesis in 8% polyacrylamide gels containing 7 M urea. After electrophoresis, the ssDNA and ssRNA is stained with ethidium bromide (10 μg mL−1) and visualized under a UV transilluminator 2000 (Bio-Rad). The desired band of polyacrylamide is cut out and crushed in water (100 μL). The nucleic acid is separated from the eluted ssDNA by using a P6 Micro-Spin chromatography columns (Bio-Rad). Purity is checked by running an analytical gel.

4.4. Long Single-Stranded DNA

The preparation of long ssDNA molecules (>200 nt) is usually achieved by using asymmetric PCR. dsDNA templates of the desired length (200 to 8,000 bp) and sequence are prepared by cutting a plasmid DNA with the requisite restriction enzymes. The desired dsDNA is purified from the plasmid DNA by PAGE. The template (e.g. ~0.4 μg of a 1 kb fragment) is then mixed with a 50 to 100-fold excess of a single synthetic primer that is complementary to a specific sequence in the dsDNA template, and 95 asymmetric PCR cycles are carried out (Screaton et al., 1993). Since only one primer is present, ssDNA is generated, which is then separated from the dsDNA template by PAGE. Alternatively, the primer that is used in the asymmetric PCR reaction can be biotinylated, and the ssDNA can be purified by chromatography with immobilized streptavidin (Kai et al., 1997; Pagratis, 1996). Asymmetric PCR produces only one copy of the template in each cycle and the final yield of ssDNA is generally poor (e.g. ~0.2 μg for the 1 kb template). The DNA was purified by using a 0.8% low-melt agarose gel.

In an alternative method, a dsDNA template (0.4 μg) is amplified in 35 PCR cycles by using two primers, one of which is protected at the 5′ end (e.g. with a covalently-attached biotin). In this case, amplification is exponential. After 35 cycles, the resulting dsDNA (~25 μg from a 50 μL reaction) is desalted by using a gel filtration column (Micro Bio-Spin P30 Column, Bio-Rad), and concentrated to 300 to 500 ng μL−1 with a centrifugal vacuum concentrator (SpeedVac, Savant). Then, to obtain ssDNA, the dsDNA is incubated with λ-exonuclease (~2 units per μg of DNA) for 3 h at 37°C, which digests the unprotected DNA strand. After further purification by PAGE, up to 2 μg of ssDNA from 5 μg of the dsDNA.

4.5. Long RNA Preparation

Long RNA molecules can be prepared by transcribing a dsDNA template with an RNA polymerase. RNA molecules up to 8000 nt long can be synthesized. Several companies including Promega and Ambion produce in vitro transcription (IVT) kits. For example, the T7 RiboMAX™ Express Large Scale RNA Production System kit (Promega) contains materials sufficient for 12 reactions and can synthesize up to 5 μg of RNA per reaction. When using this kit, the dsDNA template must contain the T7 promoter sequence that is recognized by T7 RNA polymerase. A typical reaction contains linear dsDNA template (8 μL, ~4 μg), 2X buffer (20 μL, with rNTPs), RNase free water (10 μL) and T7 RNA polymerase (2 μL). The mixture is incubated at 37°C for 1 h to produce the desired RNA and then the dsDNA template is digested with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (4 μL, 1 U μL−1) for 15 min. The digest is loaded onto a silica-based membrane column from an RNAeasy kit (Qiagen), which is washed with 70% ethanol in water (500 μL). The desired RNA is eluted with “double sterile” water (50 μL, RNAeasy kit). The RNA can be purified in a 5 or 8% polyacrylamide gel, or in a 0.8% agarose gel.

4.6. Short dsDNA Preparation

dsDNA can be prepared by mixing equimolar amounts of two synthetic complementary ssDNA in exonuclease I reaction buffer (67 mM glycine-KOH, 6.7 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 9.4; New England BioLabs, UK). To facilitate the annealing process, the temperature is brought to 95°C for one minute and then decreased stepwise to room temperature. At around the calculated annealing temperature (/www.basic.northwestern.edu/biotools/oligocalc.html), the temperature is decreased in small steps (e.g. 2°C, each held for one minute). Excess ssDNA is digested by incubation with E. coli exonuclease I (20 U, New England BioLabs) for 30 min at 37°C. The dsDNA is ethanol precipitated by first adding 0.1 volumes of 3.0 M sodium acetate at pH 5.2, and then 2.5 volumes of cold 95% ethanol. The mixture is left at −20°C for 1 h and then centrifuged at 25,000 Xg for 20 min. The white pellet is washed several times with cold 95% ethanol and after drying taken up in 10 mM Tris.HCl, pH 7.5. Residual low molecular weight contaminants can be removed by passing the DNA solution (maximum 75 μL) through a Bio-Spin® 30 column (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd, UK). The purity of dsDNA is checked by SDS-PAGE by using dyes that stain both single and double stranded nucleic acids, e.g. Stains-All (Sigma).

5. Methods: Data Acquisition and Analysis

5.1. Data Digitization

The ionic current that flows through a nanopore can be measured by using commercial instruments such as the Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier. These instruments transform the continuous analog current signal into an analog voltage signal, which is then fed to a digitizer that converts it into binary numbers with finite resolution (digitization). The digitizer is connected to a computer that converts and displays the digitized current information. We use 132x or 1440A 16-bit digitizers (Molecular Devices), with a dynamic input range of ±10 V, which divides the signal into 216 (65536) values (bins), providing a resolution of 0.305 mV per bin (20 V/216). If no output gain is applied, this corresponds to a dynamic range of ±10 nA and a resolution of 0.305 pA per bin. However, the output gain can be changed (by up to 500X) to increase the resolution (decreased binwidth), at the expense of dynamic range. Typically, when measuring the translocation of DNA molecules through a single αHL nanopore the output gain is set to at least 10X, which corresponds to a dynamic range of 1 nA and a resolution of 0.0305 pA per bin.

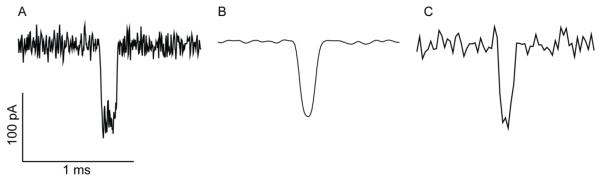

5.2. Filtering and Sampling

The signal collected by the amplifier must be filtered to remove high frequency electrical noise. The most common filtering is low-pass filtering, which limits the bandwidth of the data by eliminating signals above the corner frequency (or cut-off frequency) of the filter. Bessel filters, rather than Butterworth filters, are usually applied for time-domain analyses such as these, as Bessel filters are better at preserving the shape of the single channel response (The Axon Guide) (Silberberg and Magleby, 1993). It is important to select the correct corner frequency and in order to keep errors in estimates of current levels to <3%, the applied filter cut-off should be greater than five times the inverse of the mean event time (Silberberg and Magleby, 1993). For example, the most probable translocation time for a 92-nt DNA strand through the WT αHL, at +120 mV in 1 M KCl, 25 mM Tris.HCl at pH 8, is 0.141 ms (2008 Maglia PNAS). Therefore, the cut-off frequency should be ~35 kHz or higher (Figure 8A). Over-filtering of the signal can lead to inaccurate estimates of IB (Figure 8B). As well the appropriate filtering rate, it is important to select the correct sampling rate. The Nyquist Sampling Theorem states that the sampling rate should be twice the cut-off frequency of the applied filter (The Axon Guide). In practice however, it is preferable to oversample (i.e. sample at a rate that exceeds the Nyquist minimum) (Sakmann and Neher, 1995). A sampling rate of ten times that of the cut-off frequency of the filter is desirable, but five times the cut-off frequency is usually sufficient.

Figure 8.

The effects of the filter cut-off frequency and sampling rate on the recording of DNA translocation events. The tT for each event is ~0.14 ms suggesting a filter cut-off of ~35 kHz (see the text). (A) Signal filtered at 40 kHz with a low-pass 8-pole Bessel filter, and sampled at 250 kHz. The filtering and sampling allow faithful reproduction of the translocation event. (B) The event shown in panel A is filtered at 5 kHz. The sampling rate remains 250 kHz. IB can no longer be determined accurately. (C) In this case, although the correct level of filtering has been applied (40 kHz), the signal is sampled at the sub-optimal rate of 40 kHz.

5.3. Acquisition Protocols

The software we use to collect and display the current signals is Clampex from Molecular Devices, however, other software such as QuB (www.qub.buffalo.edu) and WinEDR (spider.science.strath.ac.uk/sipbs/page.php?show=software_winEDR) can be used. Clampex can also control the 132x or 1440A digitizer to apply a potential through the amplifier (see below). Although Clampex has five data acquisition modes, the most commonly used during DNA translocation experiments, are the “Gap Free”, “Variable-Length Events” and “Episodic Stimulation” modes.

In the Gap Free protocol, data are passively and continuously digitized, displayed and saved. There are no interruptions to the data record, which make it a useful protocol to use when preparing data for publication. However, it should not be used routinely when acquiring with a high sampling rate, or for a long period of time, as the file sizes can become very large (e.g. acquiring at 250 kHz for 1 h will produce a 1.7 GB file).

The Variable-Length Events protocol is ideal for collecting data from a fully characterized system where the frequency of events is very low, and there are long periods of inactivity. Data are visualized as in the gap free protocol, but are acquired only for as long as an input signal has passed a threshold level (which is set manually), so only the “events” and small sections on either side of them are recorded. The file sizes are therefore more manageable, although the data record is interrupted.

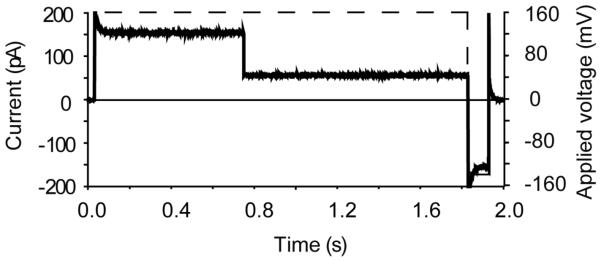

The Episodic Stimulation protocol can be used to output a voltage signal from the digitizer, which can be applied to the bilayer system, while simultaneously acquiring the resulting current signal. This mode is used to apply voltage steps (e.g. when producing I-V curves) or voltage ramps (Dudko et al., 2007). It can also be used when is it laborious to apply different voltages manually with the patch-clamp amplifier, for example, when studying the repeated immobilization of DNA molecules inside the αHL pore. In this case, a voltage bias can be applied, for a fixed amount of time, to drive a DNA into the pore. The bias is then reversed to eject the molecule from the pore (Fig. 9) (Stoddart et al., 2009; Stoddart et al., 2010). The changes in the current level that occur as a result of the voltage protocol are simultaneously acquired. The protocol can be repeated hundreds of times per run and therefore many DNA blockade events can be recorded. The output waveform can be set manually to apply different voltage steps, for different times, and it does not have to be the same for each sweep during a run.

Figure 9.

Episodic stimulation mode allows both an output voltage (red dashed line) to be applied, while simultaneously recording the resulting changes in ionic current (black trace). In this example, a positive potential bias of +160 mV is applied to the system, resulting in an open pore current level of ~160 pA. Under the applied potential, a DNA molecule is driven into the pore and becomes immobilized (through a terminal biotin·streptavidin complex), and the current level is reduced. The potential bias is reversed (−140 mV) and the DNA molecule is ejected. The bias is then removed. The protocol can be repeated numerous times.

5.4. Analysis of Single DNA/RNA Molecules

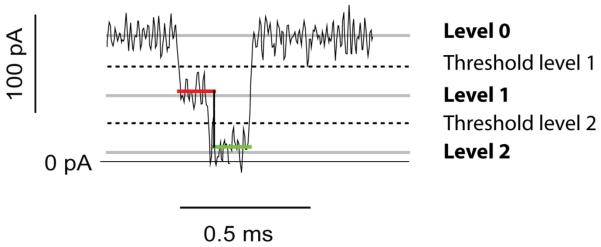

The current traces recorded by the digitizer can be analyzed by using the “single channel search” option in the Clampfit software package (Molecular Devices). In doing so, the user must assign the value of the open pore current (level 0) and a second level (level 1), which corresponds to the blocked pore level. If a DNA molecule provokes several types of current blockade, of differing amplitude, additional levels can be assigned (levels 2, 3… etc.). Every time the ionic current crosses a threshold (the half distance between two levels), the software recognizes it as an “event” (red and green lines, Fig. 10) and records its characteristics such as the mean amplitude, the dwell time and the interevent interval in a results window. Generally, for short DNA molecules, the average current amplitudes, dwell times and interevent intervals of numerous events are plotted as histograms. Gaussian fits to the events histogram of the amplitudes and dwell times are used to determine IB and tP, respectively; while t̄ON is determined from an exponential fit to the histogram of the interevent intervals. The dwell times (tD) are described by a Gaussian distribution with an exponential tail; the peak of the Gaussian (tP) is generally used to describe the most likely dwell time, which often represents the translocation time, tt (Meller et al., 2000). In the case of DNA strands immobilized within a nanopore, IB values are the only meaningful features of the events (Ashkenasy et al., 2005; Purnell and Schmidt, 2009; Stoddart et al., 2009).

Figure 10.

Typical DNA translocation event analysed by the Clampfit software. Levels 0, 1 and 2 are set manually and the software automatically assigns data points to level 1 (red line) or level 2 (green line).

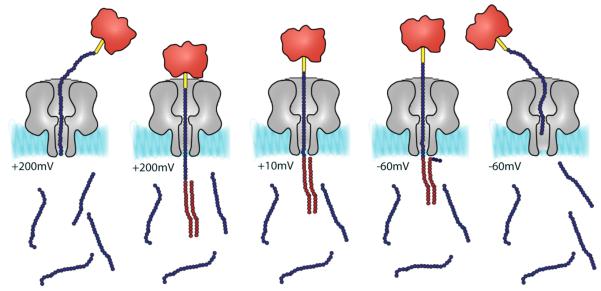

Figure 2.

Detection of a ssDNA by hybridization. From left to right: A high applied potential (e.g. +200 mV) is used to capture a biotinylated DNA probe (complexed with streptavidin) within the αHL pore. The target DNA strand emerges on the opposite side of the bilayer where it forms a duplex, if it is recognized by a complementary strand. The voltage is lowered to +10 mV. If a duplex has been formed, the probe DNA remains in the pore as a rotaxane. If a duplex has not formed the probe DNA escapes under the low applied potential. To measure the strength of the duplex, eject the probe DNA and begin a new cycle, the applied potential is stepped to −60 mV.

Abbreviations

- ddH2O

distilled, deionized water

- f

normalized frequency of DNA interactions with pore (e.g. translocation events) in s−1μM−1

- IO

open pore current

- IB

current through partially blocked pore

- IF

fractional residual current, i.e. IB/IO

- I%RES

residual current as percentage of IO, i.e. IB/IO × 100

- ΔI%RES

difference in I%RES between residual currents (e.g. for two different DNAs)

- tt

time taken for translocation of an individual nucleic acid molecule

- t̄t

mean time taken for translocation of a nucleic acid molecule

- tD

dwell time of a nucleic acid molecule (not necessarily for a translocation event)

- t̄D

mean dwell time

- tP

most probable dwell time or translocation time taken from the peak of a dwell time or translocation time histogram

- tON

interevent interval (e.g. time between translocation events)

- t̄ON

mean interevent interval

References

- Akeson M, et al. Microsecond time-scale discrimination among polycytidylic acid, polyadenylic acid and polyuridylic acid as homopolymers or as segments within single RNA molecules. Biophys.J. 1999;77:3227–3233. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenasy N, et al. Recognizing a single base in an individual DNA strand: a step toward nanopore DNA sequencing. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed.Engl. 2005;44:1401–1404. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astier Y, et al. Stochastic detection of motor protein-RNA complexes by single-channel current recording. ChemPhysChem. 2007;8:2189–2194. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200700179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley H. Sequencing single molecules of DNA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:628–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley H, Cremer PS. Stochastic sensors inspired by biology. Nature. 2001;413:226–230. doi: 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley H, et al. Droplet interface bilayers. Mol. BioSystems. 2008a;4:1191–1208. doi: 10.1039/b808893d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley H, et al. Single-molecule covalent chemistry in a protein nanoreactor. In: Rigler R, Vogel H, editors. Single Molecules and Nanotechnology. Springer; Heidelberg: 2008b. pp. 251–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bezrukov SM, Kasianowicz JJ. Current noise reveals protonation kinetics and number of ionizable sites in an open protein ion channel. Phys.Rev.Lett. 1993;70:2352–2355. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakdi S, et al. Staphylococcal a-toxin: oligomerization of hydrophilic monomers to form amphiphilic hexamers induced through contact with deoxycholate micelles. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1981;78:5475–5479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthuis DJ, et al. Self-energy-limited ion transport in subnanometer channels. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:128104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.128104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branton D, et al. The potential and challenges of nanopore sequencing. Nature Biotechnology. 2008;26:1146–1153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler TZ, et al. Ionic current blockades from DNA and RNA molecules in the alpha-hemolysin nanopore. Biophys J. 2007;93:3229–40. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler TZ, et al. Single-molecule DNA detection with an engineered MspA protein nanopore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20647–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807514106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheley S, et al. A functional protein pore with a “retro” transmembrane domain. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1257–1267. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheley S, et al. Stochastic sensing of nanomolar inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate with an engineered pore. Chem.Biol. 2002;9:829–838. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheley S, et al. Spontaneous oligomerization of a staphylococcal a-hemolysin conformationally constrained by removal of residues that form the transmembrane b barrel. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1433–1443. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.12.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P. Solubilization in formamide protects RNA from degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3791–2. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J, et al. Continuous base identification for single-molecule nanopore DNA sequencing. Nature Nanotechnology. 2009;4:265–270. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockroft SL, et al. A single-molecule nanopore device detects DNA polymerase activity with single-nucleotide resolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:818–20. doi: 10.1021/ja077082c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deamer DW, Branton D. Characterization of nucleic acids by nanopore analysis. Acc.Chem.Res. 2002;35:817–825. doi: 10.1021/ar000138m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker C. Solid-state nanopores. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:209–15. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudko OK, et al. Extracting Kinetics from Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy: Nanopore Unzipping of DNA Hairpins. Biophys J. 2007;92:4188–4195. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.102855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis X. Techniques for membrane capacitance measurements. In: Sackmann X, Neher X, editors. Single-channel recording. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gu L-Q, Bayley H. Interaction of the non-covalent molecular adapter, b-cyclodextrin, with the staphylococcal a-hemolysin pore. Biophys.J. 2000;79:1967–1975. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76445-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L-Q, et al. Prolonged residence time of a noncovalent molecular adapter, b-cyclodextrin, within the lumen of mutant a-hemolysin pores. J.Gen.Physiol. 2001;118:481–494. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.5.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke W, Schlue W-R. Planar lipid bilayers. Academic Press; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Henrickson SE, et al. Driven DNA transport into an asymmetric nanometer-scale pore. Phys.Rev.Lett. 2000;85:3057–3060. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MA, Bayley H. Direct introduction of single protein channels and pores into lipid bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6502–6503. doi: 10.1021/ja042470p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MA, et al. Direct transfer of membrane proteins from bacteria to planar bilayers for rapid screening by single-channel recording. Nature Chemical Biology. 2006;2:314–318. doi: 10.1038/nchembio793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornblower B, et al. Single-molecule analysis of DNA-protein complexes using nanopores. Nat Methods. 2007;4:315–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howorka S, et al. Sequence-specific detection of individual DNA strands using engineered nanopores. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:636–639. doi: 10.1038/90236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung WC, et al. Order-disorder transition in bilayers of diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2000;1467:198–206. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japrung D, et al. Urea facilitates the translocation of single-stranded DNA and RNA through the α-hemolysin nanopore. Biophys J. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4333. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado RT. Membrane area and electrical capacitance. Methods Enzymol. 1993;221:273–99. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)21024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai E, et al. Novel DNA detection system of flow injection analysis (2). The distinctive properties of a novel system employing PNA (peptide nucleic acid) as a probe for specific DNA detection. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1997:321–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X, et al. Single protein pores containing molecular adapters at high temperatures. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed.Engl. 2005;44:1495–1499. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasianowicz JJ, et al. Characterization of individual polynucleotide molecules using a membrane channel. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano R, et al. Controlling the translocation of single-stranded DNA through alpha-hemolysin ion channels using viscosity. Langmuir. 2009;25:1233–7. doi: 10.1021/la803556p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyser UF, et al. Direct force measurements on DNA in a solid-state nanopore. Nature Physics. 2006;2:473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Korchev YE, et al. A novel explanation for fluctuations of ion current through narrow pores. Faseb J. 1997;11:600–608. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.7.9212084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasne S, et al. Freezing and melting of lipid bilayers and the mode of action of nonactin, valinomycin, and gramidicin. Science. 1971;174:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.174.4007.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey H, et al. Physicochemical characterization of 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine in model membrane systems. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1979;555:147–167. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglia G, et al. Droplet networks with incorporated protein diodes show collective properties. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009a;4:437–40. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglia G, et al. Enhanced translocation of single DNA molecules through α-hemolysin nanopores by manipulation of internal charge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19720–19725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808296105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglia M, et al. DNA strands from denatured duplexes are translocated through engineered protein nanopores at alkaline pH. Nano Letters. 2009b;9:3831–3836. doi: 10.1021/nl9020232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin H, et al. Nanoscale protein pores modified with PAMAM dendrimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9640–9. doi: 10.1021/ja0689029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M, et al. Microfabricated teflon membranes for low-noise recordings of ion channels in planar lipid bilayers. Biophys.J. 2003;85:2684–2695. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74691-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller A. Dynamics of polynucleotide transport through nanometre-scale pores. J.Phys.: Condens.Matter. 2003;15:R581–R607. [Google Scholar]

- Meller A, Branton D. Single molecule measurements of DNA transport through a nanopore. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2583–2591. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:16<2583::AID-ELPS2583>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller A, et al. Rapid nanopore discrimination between single polynucleotide molecules. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 2000;97:1079–1084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller A, et al. Voltage-driven DNA translocations through a nanopore. Phys.Rev.Lett. 2001;86:3435–3438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles G, et al. Properties of Bacillus cereus hemolysin II: a heptameric transmembrane pore. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1813–1824. doi: 10.1110/ps.0204002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, editor. Ion channel reconstitution. Plenum; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]