Abstract

Half-lives of α-tocopherol in plasma have been reported as 2–3 d, whereas the Elgin Study required >2 y to deplete α-tocopherol, so gaps exist in our quantitative understanding of human α-tocopherol metabolism. Therefore, 6 men and 6 women aged 27 ± 6 y (mean ± SD) ingested 1.81 nmol, 3.70 kBq of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4'R, 8'R)-α-tocopherol. The levels of 14C in blood plasma and washed RBC were monitored frequently from 0 to 460 d while the levels of 14C in urine and feces were monitored from 0 to 21 d. Total fecal elimination (fecal + metabolic fecal) was 23.24 ± 5.81% of the 14C dose, so feces over urine was the major route of elimination of the ingested [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol, consistent with prior estimates. The half-life of α-tocopherol varied in plasma and RBC according to the duration of study. The minute dose coupled with frequent monitoring over 460 d and 21 d for blood, urine, and feces ensured the [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4'R, 8'R)-α-tocopherol (the tracer) had the chance to fully mix with the endogenous [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4'R, 8'R)-α-tocopherol (the tracee). The 14C levels in neither plasma nor RBC had returned to baseline by d 460, indicating that the t1/2 of [5-CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol in human blood was longer than prior estimates.

Introduction

Vitamin E is a collective term for lipid-soluble tocopherols and tocotrienols. Within the tocopherol subgroup, α-tocopherol is the most abundant in human tissues (1) due to the hepatic α-tocopherol transfer protein (α-TTP),8 and it is the only form retained at high levels to meet the nutritional needs of humans. The antioxidant role of α-tocopherol is well known and it may have additional functions such as cell signaling, gene expression, and gene regulation (2).

Ingested vitamin E is incorporated into mixed micelles in the small intestine (3, 4). The ingested vitamin E is then delivered to enterocytes by both protein-independent and -dependent mechanisms for absorption, tissue uptake, tissue efflux, and biliary secretion (5–13). In the enterocytes, α-tocopherol is packaged in chylomicra and endocytosed into the liver, where it selectively binds to the α-TTP. The α-TTP then routes α-tocopherol through export vesicles to the plasma membrane (14, 15). From the plasma membrane, α-Tocopherol is secreted by a protein-dependent mechanism prior to association with lipoproteins and delivery to peripheral tissues (16–18). α-TTP regulates systemic α-tocopherol levels by directing its traffic within the hepatocyte (19). As these transport processes of vitamin E are better understood, they will elucidate the various mechanisms of this important vitamin. Once α-tocopherol biologic functions are stipulated, the quantitative understanding of metabolism elucidated from an oral dose of [5-14CH3]-RRR-α-tocopherol can determine the amount of intake necessary to sustain optimal health.

Half-lives of α-tocopherol in plasma have been reported as 2–3 d (20–23), whereas the Elgin Study required >2 y to deplete α-tocopherol (24, 25). Although gaps exist in quantitative aspects of α-tocopherol metabolism, a recent study demonstrated the feasibility of quantifying the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of α-tocopherol with the use of a true tracer dose of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopheryl acetate in a healthy man under steady-state conditions (26). Studies that also used labeled α-tocopherol have elucidated the following 3 features of α-tocopherol metabolism (27–29). First, most ingested α-tocopherol peaked in lymph between 2 and8 h and 21–28% of ingested α-tocopherol was absorbed via lymph; second, the ingested α-tocopherol appeared in plasma within 2–4 h, peaked in 5–14 h, and disappeared from the plasma with an apparent half-life of ~2 d; third, nearly 8% of ingested α-tocopherol was eliminated via urine in 3 d. The experimental duration of these radiolabeled α-tocopherol studies (27–29) was relatively short. Consequently, the ingested radiolabeled α-tocopherol (the tracer) may not have mixed fully with the deepest and slowest turning-over pools of α-tocopherol (the tracee) in the study participants. In addition, kinetic studies that used deuterated α-tocopherol often need to administer doses that are large (21, 23, 30, 31) compared with the RDA of 15 mg/d (22.4 iu/d) of natural-source vitamin E. To obtain reliable estimates of the kinetic parameters of vitamin E metabolism, the study duration should be long enough for the tracer to fully mix with the tracee in the slowest turning-over α-tocopherol kinetic pools in the study participants. More importantly, the tracer dose should be small enough to not disturb the in vivo steady-state metabolism of the tracee. The present study reports the fate of a minute oral dose (1.81 nmol) of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol in 12 healthy adults with blood sampled over 460 d and complete collections of urine and feces made over 21 d.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol.

The [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol was synthesized as previously described (32) with 3 modifications. First, aqueous [14C]-formaldehyde containing 1.85 MBq (Sigma-Aldrich) was used instead of paraformaldehyde to form the methyl morpholino derivative of (2R, 4′R, 8′R)-γ-tocopherol. Second, a 2-step, 1-pot reaction sequence was used instead of the 3-step reaction sequence. Third, reduction was conducted using sodium cyanoborohydride in isobutanol-benzene (5:2, v:v).

The final product was purified using a C-30 column (Develosil RP Aqueous, Phenomenex) with a mobile phase consisting of 90% ethanol and 10% water at 1 mL/min flow rate. Retention time for the final product was identical to α-tocopherol standard. The purity of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol was 96.25%. The cold material was validated by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and MS to be α-tocopherol. Characteristic signal peaks of the C5-CH3 group were identified at 2.11 ppm in 1H NMR and at 11.28 ppm in 13C NMR. For the 14C-labeled material, MS analysis was performed using a Sciex API 2000 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer with positive ion atmospheric pressure chemical ionization and multiple reaction monitoring. The [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol at 0.05 μg/L in 0.1% formic acid in water:methanol (1:1, v:v) was infused into the MS at 5 μL/min. The transitions from m/z 433 ([M+H]+) to m/z 167 (formed via removal of phytyl tail) and m/z 431 ([M+H]+) to m/z 165 (nonlabeled α-tocopherol ions) were monitored and used for purity calculation. The isotopic purity of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol was 81.87%. The 14C-radioactivity was measured with a Wallac 1410 Liquid Scintillation Counter using [14C] standards. The specific activity was 1.73 TBq/mol and each dose contained an aliquot of 3.70 kBq of [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol in ethanol.

Participants.

The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards and was conducted at the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center’s Clinical Research Center (CCRC) and Ragle Human Nutrition Center (Ragle HNC). Study participants were recruited from UC Davis and from Yolo, Solano, and Sacramento counties. Informed consent was obtained from each of the 6 male and 6 female participants that were admitted into the study. Inclusion criteria were healthy, nonsmoking, not taking nutritional supplements for at least 3 mo prior to the dosing date, normolipemic, and BMI between19 and 29 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included a history of serious medical conditions, use of medications that may interfere with lipid metabolism, anemia, history of alcohol or drug abuse, and pregnancy or plans to become pregnant during the study. The volunteer’s health status was verified by laboratory tests at the UC Davis Medical Center Pathology Department. The tests included complete blood count, plasma lipid panels, and plasma α-tocopherol levels. Participants completed the 2005 Block Dietary Questionnaire self-administered FFQ (33) 6 mo after dosing to assess consistency of dietary habits.

Participants provided one 24-h urine sample and one fecal sample that served as baseline before admission into the CCRC. All urine was collected in Urisafe containers (Simport). Starting from the time of dosing, urine was collected at 6-h intervals until h 36 postdosing. From 36 to 48 h, urine was collected as one 12-h collection. From h 48 onward, all subsequent urine samples were collected in 24-h intervals until d 21 after dose. All fecal samples were collected in sterile, 4-m-thick stomacher bags (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fecal samples were collected per bowel movement starting at d −1 until d 21. The month, date, and time of each fecal collection were recorded. All blood samples were drawn into tubes containing K2EDTA (BD Vacutainer) and immediately placed on ice. All participants had ad libitum access to water throughout the study.

Participants had fasted for 12 h when they were admitted into the CCRC at 0700 h. The participants received a medical exam and then an i.v. catheter was installed in the forearm. A predose blood sample was drawn and the [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol–spiked milk was ingested at 0800 h (t = 0 h after dosing). The spiked milk was prepared by mixing [5-14CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol (0.78 μg, 3.7 kBq) with 60 g of milk (2% fat, lactose free, Lactaid, HP Hood). After consumption, the cup was rinsed with an additional 60 g of milk that was also ingested, and then breakfast was consumed promptly. The breakfast consisted of one-half (48 g) of a plain bagel (Sara Lee Foods and Beverages, Sara Lee) with 31 g [2 tablespoons (Tbsp)] of light cream cheese (Philadelphia, Kraft Foods Global). The breakfast provided 252 kcal (1056 kJ) and 8 g fat.

Lunch was served 5 h after dosing. Lunch consisted of grilled turkey breast in cranberry sauce (Healthy Choice, ConAgra Foods), 64 g of lettuce (Fresh Express Lettuce Trio, Fresh Express), 28 g (2 Tbsp) of Italian dressing (Wishbone, Unilever US), 230 g of cranberry juice (Ocean Spray, Ocean Spray Cranberries), and 1 banana. Lunch contained 623 kcal (2608 kJ) and 11 g of fat.

A snack was served 7 h after dosing. The snack consisted of 1 chewy chocolate chip granola bar (Quaker, PepsiCo) and 1 snack pack of fat-free chocolate pudding (Hunts, ConAgra Foods). The snack contained 190 kcal (795 kJ) and 3 g of fat.

Dinner was served 11 h after dosing. Dinner consisted of 1 Glazed Chicken (Stouffers Lean Cuisine Café Classics, Nestle USA), 85 g of baby arugula (Earthbound Farm Organic, Earthbound Farm), 28 g (2 Tbsp) of Italian dressing (Wishbone, Unilever US), and 230 g of pineapple-orange juice (Dole, Duo Juice). Dinner contained 450 kcal (1884 kJ) and 11 g of fat.

An evening snack was served at 12 h after dosing. The snack consisted of 1 pack of candy (Skittles, Mars Snackfood US) and 1 orange. The snack contained 300 kcal (1256 kJ) and 3 g of fat.

The following morning, breakfast was served 24 h after dosing. Breakfast consisted of 1 bagel (95g) (Sara Lee Foods and Beverages, Sara Lee) served with 31 g (2 Tbsp) of light cream cheese (Philadelphia, Kraft Foods Global) and 120 g of milk (2% fat, lactose free, Lactaid, HP Hood). The subsequent lunch, dinner, and snack menus and serving times in the day were identical to those served on the preceding day.

After being admitted for 36 h, the participants were discharged and became outpatients at the Ragle HNC. Subsequent blood samples were drawn in a fasting state on d 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 460 after dose. Final blood samples were checked for hemoglobin and packed cell volumes to confirm that participants were healthy at the end of the study. All subsequent collections of urine and feces were also received at the Ragle HNC.

Specimen analysis.

Complete blood counts and plasma lipid panels were analyzed in the Clinical Pathology Laboratory at the UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA. Total cholesterol and total TG were analyzed on the Beckman Access autoanalyzer (Beckman Instruments). LDL-cholesterol concentrations were calculated by using the Friedewald equation. HDL-cholesterol levels were analyzed using the direct HDL-cholesterol assay. The inter- and intra-assay CV for cholesterol and TG assays were <4%. Homocysteine levels were measured by using the chemiluminescent immunoassay kit on a Siemens Immulite 2000 instrument (Siemens Immulite).

Aliquots of RBC, urine, and feces specimens were dried under vacuum and analyzed for total carbon in smooth wall tin capsules (Elemental Microanalysis) and analyzed for total carbon at the UC Davis Analytical Laboratory (34). Every 10th sample was measured in duplicate. The CV (%) of total carbon was 3.5% for RBC, 1.1% for feces, and 1.6% for urine. Finally, aliquots of plasma, RBC, urine, and feces specimens were measured for their levels of 14C using accelerator MS (AMS) (35). Finally, blood α-tocopherol levels were analyzed (36).

Data analysis.

Plasma and RBC profiles were plotted by time since dose on a natural log (ln) scale using Microsoft Excel. The decrease in plasma and RBC concentration over time followed apparent first-order kinetics. The AUC was calculated by trapezoidal rule and the area under the moment curve was calculated by PKSolver (37). The mean residence time was calculated as area under the moment curve/AUC and half-life was calculated as ln2 · mean residence time. Half-life designated as t1/2 0-t was calculated using measured data points from 0-t d only (not extrapolated to infinity). Half-life designated as t1/2 0-t, ∞ was calculated from 0-t d of data that is extrapolated to infinity. The apparent absorption was calculated as (14C dose – fecal 14C from 0 to 3 d)/14C dose. The true absorption was calculated as [14C dose – (fecal 14C from 0 to 3 d – metabolic fecal 14C)]/14C dose. Metabolic fecal 14C represented the amount of 14C that was absorbed and subsequently eliminated in feces (after the first pass). The figures were drawn with StatView (SAS Institute, version 5.0.1) and transferred to Microsoft Office PowerPoint 2003. Simple regression analyses were used to assess the potential contribution of measured subject traits (BMI, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, etc.) to the observed inter-subject variation in outcome parameters [half-life, maximum concentration (Cmax), percent retained, etc.] by using StatView (SAS Institute, version 5.0.1).

Results

The study included 12 participants whose characteristics, baseline blood chemistries, and nutrient intakes are summarized in Table 1. These data indicated a healthy group of participants. The characteristics, baseline blood chemistries, and nutrient intakes for each participant are included in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Summary of participant characteristics, nutrient intakes, and baseline blood chemistries1

| Variables | |

| Participant characteristics | |

| Age, y | 27 ± 7 |

| Weight, kg | 67 ± 11 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22 ± 2 |

| Packed RBC volume, % | 41 ± 3 |

| Baseline blood chemistries | |

| Plasma HDL-cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| Plasma LDL-cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.9 ± 0.5 |

| Plasma TG, mmol/L | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

| Plasma α-tocopherol | |

| −14 d prior to dosing, μmol/L | 24 ± 3 |

| −7 d prior to dosing, μmol/L | 24 ± 3 |

| −0 d prior to dosing, μmol/L | 22 ± 3 |

| RBC α-tocopherol | |

| −14 d prior to dosing, μmol/L | 3.2 ± 0.6 |

| −7 d prior to dosing, μmol/L | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

| −0 d prior to dosing, μmol/L | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| Nutrient intake by FFQ | |

| Energy, MJ/d | 8.8 ± 3.2 |

| Total protein, g/d | 81 ± 23 |

| Fiber, g/d | 18 ± 5 |

| Saturated fat, g/d | 27 ± 14 |

| Monounsaturated fat, g/d | 31 ± 13 |

| Polyunsaturated fat, g/d | 16 ± 7 |

| (n-3) Fatty acids, g/d | 2 ± 1 |

| Cholesterol, mg/d | 233 ± 90 |

| α-Tocopherol, mg/d | 7.6 ± 2.8 |

| Vitamin C, mg/d | 84 ± 21 |

| Selenium, mg/d | 121 ± 54 |

Values are mean ± SD, = 12.

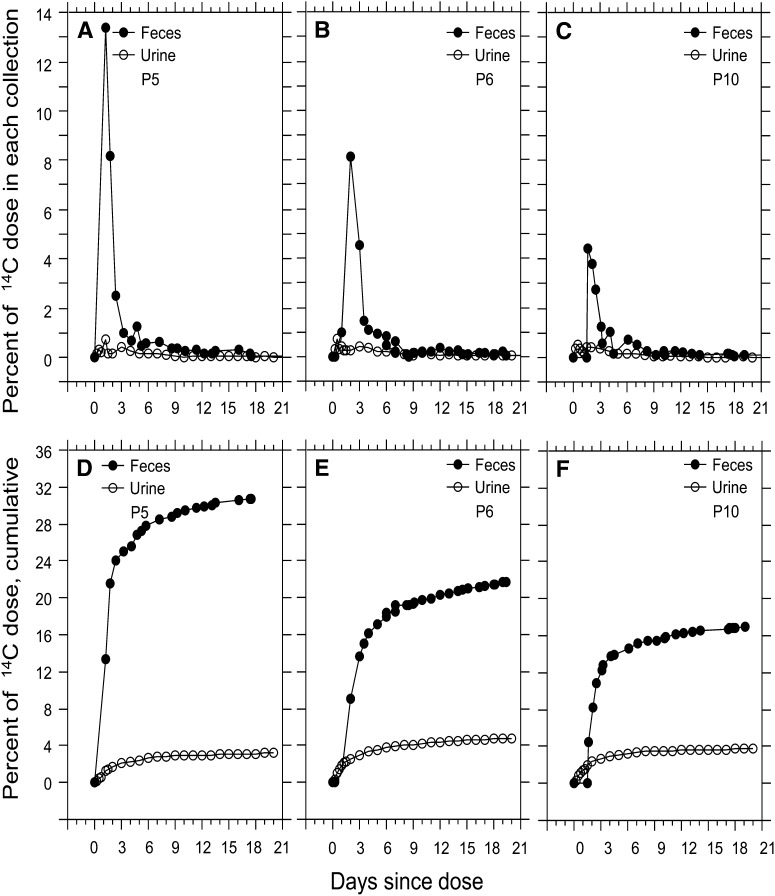

The portions of 14C that were eliminated via urine and feces from 3 representative participants (5, 6,and 10) are plotted in Figure 1A–C and the cumulative collections are plotted in respectively. Participant 5 (Fig. 1D) eliminated the most 14C (30.8%) and participant 10 (Fig. 1F) eliminated the least 14C (17%). Table 2 includes a summary of the total amount of 14C that was eliminated and its mass balance. Only 4.26 ± 1.38% was eliminated via urine, 23.2 ± 5.8% was eliminated via feces, and the mass balance was 72.5 ± 5.5% (100–4.26–23.2).

FIGURE 1.

Elimination of 14C in urine and feces of participants 5, 6, and 10.

TABLE 2.

Summary of 14C mass balance, concentration maxima (Cmax, % dose/L), time to maxima (Tmax, d) in plasma (% dose/L), RBC (% dose/L), urine (% dose/collection), and feces (% dose/collection)1

| Total eliminated |

Total retained |

|||||

| Variables | Collection duration | Plasma | RBC | Urine | Feces | Body (mass balance)2 |

| % of dose | ||||||

| Present study: RRR-α-tocopherol | 21 d urine, 21 d feces | 4.26 ± 1.38 | 23.2 ± 5.8 | 72.5 ± 5.5 | ||

| Prior study: RRR-α-tocopherol (26) | 8 d urine, 7 d feces | – | – | 6.32 | 27.9 | 65.8 |

| Prior study: all-rac-α-tocopherol (26) | 8 d urine, 7 d feces | – | – | 16.5 | 31.5 | 52.0 |

| Prior study: all-rac-α-tocopherol (28) | 12 d urine, 12 d feces | – | – | <6.00 | 27.6 | 66.4 |

| Prior study: all-rac-α-tocopherol (29) | 3 d urine, 6 d feces | – | – | 8.21 | 31.4 | 60.4 |

| Cmax, | % dose/L | % dose/collection | ||||

| Present study: RRR-α-tocopherol | 5.39 ± 1.58a | 1.59 ± 0.31b | 0.72 ± 0.41c | 10.2 ± 3.64d | – | |

| Prior study: RRR-α-tocopherol (21) | 5.92 ± 1.90 | 1.09 ± 0.32 | – | – | – | |

| Tmax | d | |||||

| Present study: RRR-α-tocopherol | 0.58 ± 0.17e | 0.94 ± 0.13f | 1.42 ± 1.12g | 2.12 ± 0.77h | – | |

| Prior study: RRR-α-tocopherol (21) | 0.53 ± 0.24 | 1.06 ± 0.41 | – | – | – | |

Values are mean ± SD. Letters indicate that the labeled means differ: a-b, c-d < 0.0001; e-f, g-h P < 0.0002.

Mass balance (%) = 100 – 4.26 (urine) – 23.2 (feces).

Table 2 also includes a summary of the Cmax and the time to maximum (Tmax) for plasma, RBC, urine, and feces. The plasma Cmax was higher (P < 0.0001) than the RBC Cmax. The plasma Cmax was lower in males than in females (P < 0.0111). The urine Cmax was lower than that of feces (P < 0.0001). Plasma Tmax occurred sooner than did the RBC Tmax (P < 0.0002). Urine Tmax also occurred sooner than did the fecal Tmax (P < 0.0002). Finally, the total amount of 14C that was eliminated, its mass balance, the Cmax and Tmax for plasma, RBC, urine, and feces for each participant is included in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

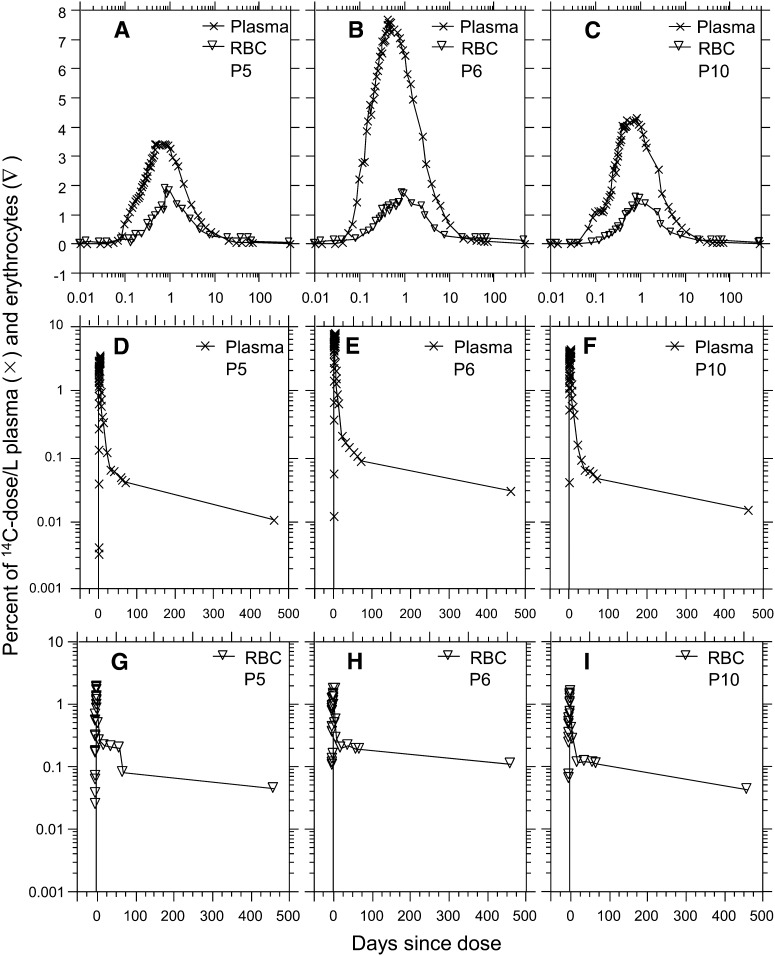

The profiles of the 14C tracer in plasma and RBC by time since dosing the 3 representative participants (5, 6, and 10) are plotted in Figure 2A–C. The 14C first appeared in plasma and RBC at ~0.05 and ~0.1 d, respectively. The 14C peaked in plasma and RBC plasma at ~0.5 and ~1.0 d, respectively. The plasma AUC for participants 5 and 10 were similar to each other (~35% dose/L), whereas the AUC for participant 6 was twice as large (69% dose/L). RBC AUC for participants 5 and 10 were similar to each other (57% dose/L), whereas that for participant 6 was ~2.5 times larger (154% dose/L). Figure 2D-F showed that plasma t1/2 0–460,∞ for participants 5 and 10 were similar to each other (~104 d), whereas that for participant 6 was 24% longer (129 d). Figure 2G–I showed that RBC t1/2 0–460,∞ for participants 5 and 10 were similar to each other (~215 d), whereas that for participant 6 was twice longer (455 d). The AUC and t1/2 for the 14C in plasma and RBC from each participant over the following durations of time (0–2, 0–4, 0–5, 0–70, and 0–460 d) are included in Table 3. The detailed data on each participant are included in Supplemental Tables 5 and 6.

FIGURE 2.

Profiles of 14C in plasma (X) and RBC (▿) of participants 5, 6, and 10.

TABLE 3.

Summary half-life and AUC of dose in plasma and RBC of present and prior study1

| AUC |

t1/2 |

|||

| Plasma | RBC | Plasma | RBC | |

| % dose/L·d | d | |||

| Nonextrapolated | ||||

| 0–2 d, 0-t | 8.78 ± 2.68 | 2.49 ± 0.58 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.07 |

| 0–4 d, 0-t | 11.9 ± 3.3 | 3.62 ± 0.85 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 1.26 ± 0.10 |

| 0–5 d, 0-t | 13.3 ± 3.7 | 4.32 ± 1.01 | 1.32 ± 0.07 | 1.50 ± 0.17 |

| 0–70 d, 0-t | 24.2 ± 7.5 | 14.6 ± 3.6 | 7.46 ± 0.50 | 15.2 ± 3.0 |

| 0–460 d, 0-t | 36.7 ± 9.5 | 42.4 ± 21.5 | 44.0 ± 12.0 | 95.7 ± 41.9 |

| Extrapolated | ||||

| 0–2 d, 0-∞ | 17.1 ± 6.0 | 5.52 ± 2.04 | 2.18 ± 0.66 | 2.64 ± 0.78 |

| Prior study (21) | 1.79 ± 0.88 | 2.13 ± 0.58 | ||

| Prior study (20) | 2.15 ± 0.73 | |||

| 0–4 d, 0-∞ | 15.8 ± 4.7 | 5.44 ± 1.03 | 1.95 ± 0.21 | 2.47 ± 0.46 |

| Prior study (23) | 3.36 ± 0.80 | 9.3 ± 2.37 | ||

| Prior study (22) | 1.83 ± 0.78 | |||

| 0–5 d, 0-∞ | 16.9 ± 5.3 | 5.56 ± 1.30 | 2.24 ± 0.26 | 2.48 ± 0.49 |

| 0–70 d, 0-∞ | 27.6 ± 8.4 | 32.9 ± 18.0 | 18.3 ± 5.2 | 96.2 ± 80.6 |

| 0–460 d, 0-∞ | 41.6 ± 10.7 | 63.8 ± 47.0 | 105 ± 67 | 217 ± 123 |

Values are mean ± SD, = 12.

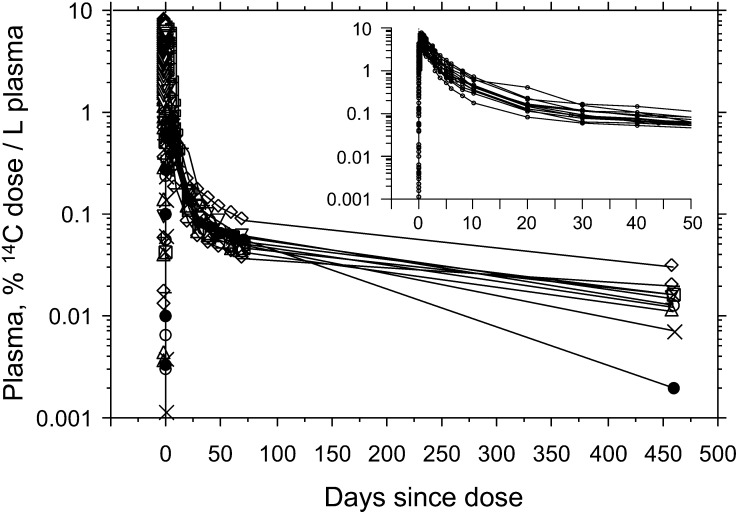

The 14C tracer in participants 5, 6, and 10 first appeared in plasma between d 0.03 (min 40) and d 0.07 (min 100) and peaked there between d 0.42 (h 10) and d 0.83 (h 20), whereas the 14C tracer first appeared in RBC at ~d 0.05 and peaked there between d 0.83 (h 20) and d 0.92 (h 22) (Fig. 2A–C). The 14C levels in neither plasma (Fig. 2D–F) nor RBC (Fig. 2G-I) returned to baseline by d 460, indicating the t1/2 of [5-CH3]-(2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol in human blood was longer than prior estimates. The 14C profiles in plasma until ~d 460 are illustrated in Figure 3 and the AUC of each participant is calculated from Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Plasma 14C profile for all participants from 0 to 460 d and 0 to 50 d (insert).

Discussion

The fate of the 14C (the tracer) was quantified in urine and feces until d 21 and in blood (plasma and RBC) until d 460. The complete collections of urine and feces until d 21 and blood draws until d 460 were needed for accurate mass balance data, because the longer duration of the study, the greater the chance for the tracer to fully mix with the tracee in the slowest turning-over pools of α-tocopherol. Full mixing of tracer with tracee can become the key determinant of α-tocopherol metabolism late in studies. Short duration was a limitation of prior single-dose in studies (20–23, 28, 29).

Baseline levels of α-tocopherol in plasma and RBC were reached at d 0 and −7, respectively (Table 1). The baseline blood levels of α-tocopherol were comparable to those of Americans ≥ 20 y old who did not use supplements or supplements containing vitamin E (38). In addition, the dietary intake of α-tocopherol was 7.6 ± 2.8 mg/d (Table 1), an intake close to the RDA (7.3 mg/d for men, 5.4 mg/d for women) and vitamin E intakes in the US (39). Finally, the ratio of vitamin E:PUFA in the diet was 0.48 ± 0.06, which was also close to the desirable ratio of ≥0.4 (40). So the participants were considered to be stable with respect to their α-tocopherol status and to be characterized as healthy and well nourished.

The amount of 14C eliminated over a 21-d period via urine and feces were 4.26 ± 1.38% and 23.2 ± 5.8%, respectively. The amount retained as body mass balance [72.5 ± 5.5% (100–4.26–23.2%)] was close to intestinal absorption of α-tocopherol as previously reported (28,29,26) (Table 2). The major route of elimination for α-tocopherol is in feces, which is consistent with the current literature (41).

Prior tracer studies referenced in Table 2 administered 3H- or 14C-labeled α-tocopherol; 555–740 kBq 3H in 0.46 μmol all-rac-α-tocopherol (28), 444–925 kBq 3H in 2.32 mmol all-rac-α-tocopherol (29), and (in a test and retest design) 3.76 kBq 14C in 1.82 nmol (2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol acetate and 3.70 kBq 14C in 1.67 nmol all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate (26). These 3 prior studies, whose duration was ≤12 d, reported that the apparent absorption of α-tocopherol was 72.4% with a range of 51–86% (28), 68.6% with a range of 55.0–78.6% (29), 77.5% for (2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol (26), and 77.5% for all-rac-α-tocopherol (26). Our study finding was consistent with these referenced studies of 79.2%. More details on the absorption are in Supplemental Table 3.

The Cmax and Tmax for plasma (5.39% of dose/L plasma and 0.58 d) and RBC (1.59% of dose/L RBC and 0.94 d) were consistent with prior values (27) referenced in Table 2. The Cmax for plasma was 3-fold higher than for RBC. Tmax for RBC was delayed for 12 h compared with that for plasma. The delay may reflect a transfer from plasma to RBC that may have involved more than simple diffusion (42, 43). More details on the Cmax and Tmax are in Supplemental Table 4.

A total of 23.24% of the dose was eliminated in feces over 21 d, whereas only 4.26% was eliminated via urine. Only 0.03% (0.51 ± 0.25%/17 d) of the dose was eliminated per day via urine and only 0.14% (2.43 ± 0.87%/17 d) of the dose was eliminated per day via feces. The data agreed with prior studies that reported the body mass balance of α-tocopherol was not readily accessible for metabolism or elimination under normal conditions, because only a total of 0.17% (0.03% from urine + 0.14% from feces) of the dose was eliminated per day (44–46).

The half-life based on measured data was always smaller than the half-life extrapolated to infinity over the same duration. This was especially obvious in the 0–70 and 0–460 d data. The differences between nonextrapolated and extrapolated half-lives demonstrated the importance of conducting studies long enough to capture the α-tocopherol metabolism in the slow turning-over pools. Thus, the longer the study duration, the better the estimate of the true half-life. The half-lives over 0–2, 0–4, 0–5, 0–70, and 0–460 d (Table 3) demonstrated the effect of duration on the calculation of α-tocopherol half-life.

The rate of disappearance of 14C from plasma in and Table 3 showed that the nonextrapolated half-life from 0 to 70 d (t1/2 0–70) was 7.46 ± 0.50 d and the extrapolated half-life (t1/2 0–70, ∞) was 18.34 ± 5.24 d. These t1/2 values were ~8 times greater than the prior values referenced in Table 3 (20–23). The t1/2 0–460 d and its extrapolated half-life (t1/2 0–460, ∞) were 44.03 ± 12.03 and 104.80 ± 67.63 d, respectively (Table 3). Based on the 0–70 d data, participant 7 had the shortest t1/2 0–70,∞ of 9.75 d and participant 9 had the longest at 26.81 d, a 2.7-fold difference between the 2 participants. The same study with a shorter analysis time had a 1.5-fold difference between these 2 participants.

In general, the half-life of 14C-tracer for RBC and plasma shared similar trends, but the half-life was longer for RBC, especially over long periods of time. Based on 0–70 d of data, participants 9 and 10 had the shortest and longest RBC t1/2 0–70, ∞ of 10.19 and 219.78 d, respectively, which corresponded to a 22-fold difference.

The short half-lives based on ≤5 d may reflect the turnover of lipoprotein particles that (2R, 4′R, 8′R)-α-tocopherol relied on for transport. The α-tocopherol was packaged in chylomicra, endocytosed, and delivered to α-TTP to associate with lipoproteins for delivery to peripheral tissues (16–18). The lipoprotein half-lives of LDL apo-B particles, HDL apoA-I, and HDL apoA-II half-lives were 1.7, 2.7, and 3 d, respectively (47, 48).

The long half-life values based on ≥20 d of data may reflect recycling of RRR-α-tocopherol to plasma from peripheral tissues such as adipose tissue, where ≤10% of adipocytes were removed annually (44). Very little α-tocopherol was mobilized from adipose tissue (45). Based on the present data, the half-life of plasma α-tocopherol seemed to be longer than prior estimates, primarily due to the long duration of the present study. Quantifying the fraction of the 14C-dose in the plasma lipoprotein fractions over time since dosing and constructing a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model will provide new insights into RRR-α-tocopherol metabolism as it occurred in vivo in healthy humans.

Contributions of participant traits (LDL-cholesterol) to the 14C outcome parameters were detailed as follows. High levels of LDL-cholesterol were associated with increased elimination of 14C dose from 0 to 21 d in urine (r = 0.7897; P = 0.0022). High levels of HDL-cholesterol were associated with reduced elimination of the 14C-dose over a 4- to 21-d period in feces (r = −0.7224; P = 0.0080) and a longer half-life of the 14C-dose (t1/2 0–460, ∞) in plasma (r = 0.6386; P = 0.0469). Finally, the increased intakes of vitamin D were associated with a shorter half-life of the 14C-dose (t1/2 0–70, ∞) in RBC (r = −0.7252; P = 0.0076). BMI and vitamin C and E intakes were not associated with the outcome parameters of 14C in plasma, RBC, urine, or feces.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.C.C. and A.J.C. designed research; J.C.C. conducted research; J.C.C., J.G.F., and A.J.C. analyzed and interpreted the data; A.J.C. and J.C.C. wrote the paper; A.J.C. had primary responsibility for the final content; S.K. advised on AMS target sample preparation for 14C-AMS; and H.D.M., K.P.N., J.C.C., and D.M.H. synthesized and characterized the [5-14CH3]-RRR-α-tocopherol. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant R01 DK 081551, USDA Regional Research W-2002, the California Agricultural Experiment Station, and grant UL1 RR024146 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Aspects of this work were performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract DE-AC52-07NA27344 and NIH National Center for Research Resources grant RR13461.

Supplemental Tables 1–6 are available from the “Online Supporting Material” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at jn.nutrition.org.

Abbreviations used: AMS, accelerator MS; CCRC, Clinical and Translational Science Center’s Clinical Research Center; Cmax, maximum concentration; HNC, Human Nutrition Center; t1/2 0-t, half-life calculated using measured data points from 0-t d only; t1/2 0-t,∞, half-life calculated from 0-t d, extrapolated to infinity; Tbsp, tablespoon; Tmax time to maximum; α-TTP, α-tocopherol transfer protein.

Literature Cited

- 1.Cohn W. Bioavailability of vitamin E. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51 Suppl 1:S80–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricciarelli R, Zingg JM, Azzi A. Vitamin E reduces the uptake of oxidized LDL by inhibiting CD36 scavenger receptor expression in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2000;102:82–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo-Torres HE. Obligatory role of bile for the intestinal absorption of vitamin E. Lipids. 1970;5:379–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokol RJ, Heubi JE, Iannaccone S, Bove KE, Balistreri WF. Mechanism causing vitamin E deficiency during chronic childhood cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1172–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orso E, Broccardo C, Kaminski WE, Bottcher A, Liebisch G, Drobnik W, Gotz A, Chambenoit O, Diederich W, et al. Transport of lipids from golgi to plasma membrane is defective in tangier disease patients and Abc1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2000;24:192–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oram JF, Vaughan AM, Stocker R. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 mediates cellular secretion of alpha-tocopherol. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39898–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shichiri M, Takanezawa Y, Rotzoll DE, Yoshida Y, Kokubu T, Ueda K, Tamai H, Arai H. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 is involved in hepatic alpha-tocopherol secretion. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:451–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reboul E, Trompier D, Moussa M, Klein A, Landrier JF, Chimini G, Borel P. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 is significantly involved in the intestinal absorption of alpha- and gamma-tocopherol but not in that of retinyl palmitate in mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:177–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mardones P, Strobel P, Miranda S, Leighton F, Quinones V, Amigo L, Rozowski J, Krieger M, Rigotti A. Alpha-tocopherol metabolism is abnormal in scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI)-deficient mice. J Nutr. 2002;132:443–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reboul E, Klein A, Bietrix F, Gleize B, Malezet-Desmoulins C, Schneider M, Margotat A, Lagrost L, Collet X, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is involved in vitamin E transport across the enterocyte. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4739–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narushima K, Takada T, Yamanashi Y, Suzuki H. Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 mediates alpha-tocopherol transport. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:42–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustacich DJ, Shields J, Horton RA, Brown MK, Reed DJ. Biliary secretion of alpha-tocopherol and the role of the mdr2 P-glycoprotein in rats and mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;350:183–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takada T, Suzuki H. Molecular mechanisms of membrane transport of vitamin E. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:616–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arita M, Nomura K, Arai H, Inoue K. alpha-Tocopherol transfer protein stimulates the secretion of alpha-tocopherol from a cultured liver cell line through a brefeldin A-insensitive pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12437–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian J, Morley S, Wilson K, Nava P, Atkinson J, Manor D. Intracellular trafficking of vitamin E in hepatocytes: the role of tocopherol transfer protein. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2072–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traber MG, Kayden HJ. Vitamin E is delivered to cells via the high affinity receptor for low-density lipoprotein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40:747–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rigotti A. Absorption, transport, and tissue delivery of vitamin E. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:423–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balazs Z, Panzenboeck U, Hammer A, Sovic A, Quehenberger O, Malle E, Sattler W. Uptake and transport of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and HDL-associated alpha-tocopherol by an in vitro blood-brain barrier model. J Neurochem. 2004;89:939–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakur V, Morley S, Manor D. Hepatic alpha-tocopherol transfer protein: ligand-induced protection from proteasomal degradation. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9339–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall WL, Jeanes YM, Lodge JK. Hyperlipidemic subjects have reduced uptake of newly absorbed vitamin E into their plasma lipoproteins, erythrocytes, platelets, and lymphocytes, as studied by deuterium-labeled alpha-tocopherol biokinetics. J Nutr. 2005;135:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeanes YM, Hall WL, Lodge JK. Comparative (2)H-labelled alpha-tocopherol biokinetics in plasma, lipoproteins, erythrocytes, platelets and lymphocytes in normolipidaemic males. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:92–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traber MG, Ramakrishnan R, Kayden HJ. Human plasma vitamin E kinetics demonstrate rapid recycling of plasma RRR-alpha-tocopherol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10005–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferslew KE, Acuff RV, Daigneault EA, Woolley TW, Stanton PE., Jr Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the RRR and all racemic stereoisomers of alpha-tocopherol in humans after single oral administration. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;33:84–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwitt MK. Vitamin E and lipid metabolism in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1960;8:451–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horwitt MK, Harvey CC, Duncan GD, Wilson WC. Effects of limited tocopherol intake in man with relationships to erythrocyte hemolysis and lipid oxidations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1956;4:408–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clifford AJ, de Moura FF, Ho C, Chuang JC, Follett JR, Fadel JG, Novotny JA. A feasibility study quantifying in vivo human alpha-tocopherol metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1430–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blomstrand R, Forger L. Labelled tocopherols in man. Intestinal absorption and thoracic-duct lymph transport of dl-alpha-tocopheryl-3,4–14C2 acetate dl-alpha-tocopheramine-3,4–14C2 dl-alpha-tocopherol-(5-methyl-3H) and N-(methyl-3H)-dl-gamma-tocopheramine. Int Z Vitaminforsch. 1968;38:328–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelleher J, Losowsky MS. The absorption of alpha-tocopherol in man. Br J Nutr. 1970;24:1033–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacMahon MT, Neale G. The absorption of alpha-tocopherol in control subjects and in patients with intestinal malabsorption. Clin Sci. 1970;38:197–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acuff RV, Thedford SS, Hidiroglou NN, Papas AM, Odom TA., Jr Relative bioavailability of RRR- and all-rac-alpha-tocopheryl acetate in humans: studies using deuterated compounds. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheeseman KH, Holley AE, Kelly FJ, Wasil M, Hughes L, Burton G. Biokinetics in humans of RRR-alpha-tocopherol: the free phenol, acetate ester, and succinate ester forms of vitamin E. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:591–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Netscher T, Mazzini F, Jestin R. Tocopherols by hydride reduction of dialkylamino derivatives. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;1176–83 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block G, Wakimoto P, Block T. A revision of the Block Dietary Questionnaire and Database, based on NHANES III data [cited 2011 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.nutritionquest.com/products/B98_DEV.pdf.

- 34.Microchemical determination of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen, automated method. In AOAC official methods of analysis, 18th edition Gaithersburg, MD: AOAC International; 2006. Chapter 12, pp. 5–6 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SH, Kelly PB, Clifford AJ. Biological/biomedical accelerator mass spectrometry targets. 1. optimizing the CO2 reduction step using zinc dust. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7651–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siluk D, Oliveira RV, Esther-Rodriguez-Rosas M, Ling S, Bos A, Ferrucci L, Wainer IW. A validated liquid chromatography method for the simultaneous determination of vitamins A and E in human plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44:1001–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Huo M, Zhou J, Xie S. PKSolver: an add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;99:306–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford ES, Schleicher RL, Mokdad AH, Ajani UA, Liu S. Distribution of serum concentrations of alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:375–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy SP, Subar AF, Block G. Vitamin E intakes and sources in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:361–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Food and Nutrition Board Recommended Dietary Allowances. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium and carotenoids. Report of the Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitabchi AE, Wimalasena J. Specific binding sites for D-alpha-tocopherol on human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;684:200–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitabchi AE, Wimalasena J. Demonstration of specific binding sites for 3H-RRR-alpha-tocopherol on human erythrocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;393:300–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, Bernard S, Buchholz BA, Bergmann O, Blomqvist L, Hoffstedt J, Naslund E, et al. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature. 2008;453:783–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schaefer EJ, Woo R, Kibata M, Bjornsen L, Schreibman PH. Mobilization of triglyceride but not cholesterol or tocopherol from human adipocytes during weight reduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;37:749–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Traber MG, Kayden HJ. Tocopherol distribution and intracellular localization in human adipose tissue. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:488–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Proteggente AR, Turner R, Majewicz J, Rimbach G, Minihane AM, Kramer K, Lodge JK. Noncompetitive plasma biokinetics of deuterium-labeled natural and synthetic alpha-tocopherol in healthy men with an apoE4 genotype. J Nutr. 2005;135:1063–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millar JS, Duffy D, Gadi R, Bloedon LT, Dunbar RL, Wolfe ML, Movva R, Shah A, Fuki IV, et al. The potent and selective PPAR-α agonist LY518674 upregulates both apoA-I production and catabolism in human subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:140–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.