Abstract

We evaluated the facilitative effects of multiple exemplar training (MET) on the establishment of derived tact relations in typically developing children. A multiple-probe design across stimulus sets was implemented to introduce MET. Participants were first taught to conditionally relate dictated names in English to their corresponding objects (listener behavior; A-B relations), followed by tests for derived tacts (B-A relations). If participants failed these tests, MET was implemented whereby tact relations were explicitly taught with novel stimulus sets, followed by test probes with the original training set. MET continued with novel stimuli until participants met criterion for the emergence of derived tact relations or after exposure to three MET sets. Results indicated failed tests for tact relations following direct training in listener relations, and marked improvements in derived tact relations following MET across all participants.

Keywords: multiple exemplar training, verbal behavior, preschool children, second language instruction

Research conducted within the field of behavior analysis has demonstrated the importance of environmental variables in teaching a second language (Davis & O'Neill, 2004; Madrid & Torres, 1986; Petursdottir & Hafliđadóđttir, 2009; Petursdottir, Ólafsdóttir, & Aradóttir, 2008; Shimamune & Smith, 1995); including use of the instructional paradigm referred to as stimulus equivalence (Joyce & Joyce, 1993; Polson, Grabavac, & Parsons, 1997; Polson & Parsons, 2000). Despite the handful of applications conducted within this area of research, there is a need for further investigations to determine how emergent foreign language repertoires may be established when these skills are not acquired via traditional training techniques (i.e., match-to-sample). Recommendations from previous research in the area of teaching second language skills have also commented on this need (Petursdottir & Hafliđadóđttir, 2009).

One intervention to establish emergent verbal repertoires is the training of sufficient exemplars, or multiple exemplar training (MET). MET involves directly teaching a specific behavior with a variety of stimulus variations or response topographies that ultimately helps to ensure a learner acquires a desired response in the form of multiple untrained topographies. For example, MET has been employed in studies to teach generalized imitation (Garcia, Baer, & Firestone, 1971) and language skills to individuals with developmental disabilities (Guess, Sailor, Rutherford, & Firestone, 1971), including children with autism (Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Nuzzolo-Gomez & Greer, 2004), and children with language delays (Greer, Stolfi, Chavez-Brown, Rivera-Valdes, 2005; Greer, Yuan, & Gautreaux, 2005). In these and similar studies, the history of reinforcement provided during training is said to generate a higher order (Catania, 1992) or generalized operant (Barnes-Holmes & Barnes-Holmes, 2000).

Research on derived relational responding and MET specifically refers to instructional histories that are designed to establish a particular class of arbitrarily applicable responding. Relational Frame Theory (RFT) describes this interaction as “a history of reinforcement for responding in accordance with a range of contextually controlled, arbitrarily applicable relations … where derived relational responding is established by a history of reinforcement across exemplars” (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001, p. 25–26). Therefore, some direct training in combining relations may be necessary in order for individuals to demonstrate derived relations. The Naming Hypothesis (Horne & Lowe, 1996) states that naming is a bidirectional speaker-listener relation that establishes category relations between a set of stimuli such that each stimulus in a set elicits the same name. In their account of naming, Horne and Lowe describe the occurrence of repeated incidental language interactions between a child, his or her caregiver, and objects in the environment that may help establish a bidirectional listener-speaker relation. This incidental language experience may also be conceptualized as a type of MET, which helps to establish an important component of naming. Support of the Naming Hypothesis is evident in studies which have demonstrated that explicit training of common names for sets of stimuli facilitate derived responding and the formation of arbitrary stimulus classes (Lowe, Horne, Harris, & Randle, 2002; Lowe, Horne, & Hughes, 2005).

Empirical demonstrations on the effectiveness of MET, as described by RFT, have been based on basic laboratory preparations. That is, stimuli utilized typically consisted of abstract shapes or relationships among visual stimuli and actions with no educational relevance for the participants (e.g., Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Roche, & Smeets, 2001a, 2001b; Berens & Hayes, 2007; Luciano, Gomez-Becerra, & Rodriguez-Valverde, 2007). For example, Barnes-Holmes and colleagues (2001a, 2001b) investigated the effects of MET in the transformation of function in accordance with symmetry. Typically developing preschool children (4–5 years old) were recruited and initially trained to name actions and objects to be used as experimental stimuli. Participants were then exposed to action-object conditional discrimination training, and subsequently probed on tests for derived object-action (symmetry) relations. Results indicated participants did not derive symmetry relations until they had been exposed to explicit symmetry training with at least one set of stimuli. The second series of experiments excluded name training, reversed the trained and tested relations (i.e., train object-action; test action-object), and replicated these results. Gomez and colleagues (2007) extended and replicated these findings by demonstrating the effectiveness of MET for derived symmetry and equivalence relations with typically developing 4-year-old children using action-object relations.

MET has also been effective in establishing arbitrary comparative relations. Specifically, Berens and Hayes (2007) trained children to assign arbitrary “values” to colored shapes or abstract stimuli (e.g., stimulus “A” represented by a blue smiley face is “more than” stimulus “B” represented by a pink thunderbolt). The relationship between stimuli was defined by the experimenter in each trial, after which participants were asked to indicate which of the stimuli he or she would use to buy candy. Correct responses (i.e., participants selected the stimulus designated as “more” on any given trial) were differentially reinforced. Results indicated that reinforced MET facilitated derived arbitrary comparative relations. That is, participants indicated which abstract stimulus was “more than” or “less than” with stimuli that had not been directly trained in each relation only following MET.

Finally, Luciano and colleagues (2007) investigated the impact of MET on the emergence of receptive symmetry with visual-visual equivalence relations in a young typically developing child (15 months). The participant was directly taught to relate a set of objects with sounds or hand movements, and tested using a different set of stimuli with longer delays to simulate the acquisition of language in a natural context. Results of this training indicated that a history of training in bidirectional relations facilitated the emergence of visual-visual equivalence relations.

The present investigation was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of MET on the emergence of object-name (or tact) relations. This study aimed to extend previous research in the application of derived relational responding by applying MET to the acquisition of a second language with educationally relevant stimuli. The need for further applications in this area of research is sorely needed. Although basic laboratory studies are abundant in the area of derived relational responding, applied and translational studies are less often seen.

METHOD

Participants, Setting, and Stimulus Materials

Four typically developing children, aged 3 years 5 months to 3 years 11 months, were recruited from a local Head Start program. All participants' first language was Spanish. Sessions were conducted three to five times per week for 45–60 min per day in a quiet area of the participants' home or school. Short breaks (2–3 min) earned via a token system were interspersed throughout teaching sessions. During breaks, participants were provided with a choice of at least two preferred leisure items or toys that had been previously identified via a paired-choice preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992).

Three 4-item stimulus sets were used to test the emergence of derived English-language tact (B-A) relations (see Table 1). Nine additional 4-item sets were used during MET (see Table 2). All stimuli consisted of three dimensional educationally relevant objects collected for the purpose of this experiment. Names of the items used during training were of approximately equal length (e.g., 1–3 syllables in length) and not easily translated due to formal similarities (e.g., excluded the stimulus “car” because it was too similar to the Spanish word “carro”). Pictures of similar, but not identical stimuli were downloaded from the Internet via a Google® Internet search and printed in color on 3×5 in. index cards for use during stimulus generalization probes. A stimulus placement board was created for presentation of items during listener training. The stimulus placement board consisted of a white foam board with four identical rectangular shapes drawn equidistant from one another. Each of the four items used from each set were placed within one of the rectangular shapes and presented to the participants during training and testing trials. The purpose of the stimulus placement board was to present all stimuli in front of the participant at the same time; ensuring stimuli were presented equidistant from one another and equidistant from the participant in order to avoid inadvertent positional prompting.

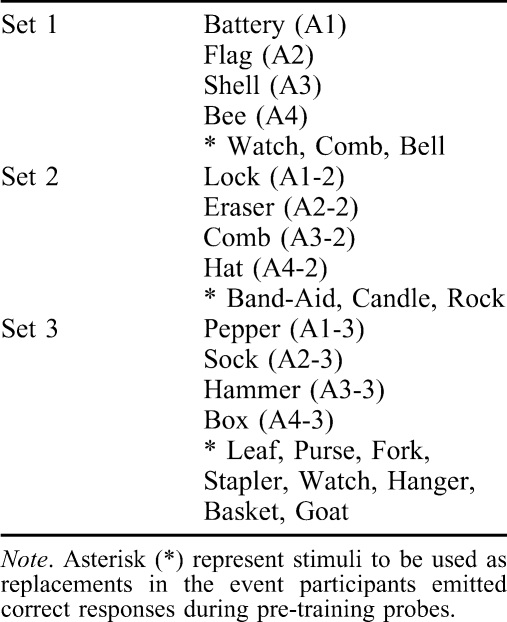

Table 1.

Names of Stimuli used During Listener Training and Testing

Table 2.

Names of Stimuli used for Multiple Exemplar Training

Experimental Design, Dependent Measure and Interobserver Agreement

A multiple-probe design across stimulus sets was employed (Horner & Baer, 1978), with stimulus sets counterbalanced across participants. Pre-training probes were conducted initially for all training sets (e.g., sets 1–3), followed by listener training in the first set selected for that participant (e.g., set 1 or 2). Only one set of stimuli was trained at a time, and only sets 1–3 were included in the training sequence to test for a functional relationship between training and performance on post-training probes. Pre-training probes were repeated for the stimulus sets yet to be trained (e.g., sets 2 and 3) following emergence of derived tact relations in the current training set (e.g., set 1), or after MET was conducted with three sets as denoted in Table 2. These probes are denoted as pre-training probes in Figures 1–4. All other stimulus sets were used only as needed during the MET phase of the study and pre-training probes for those stimulus sets were conducted only as needed.

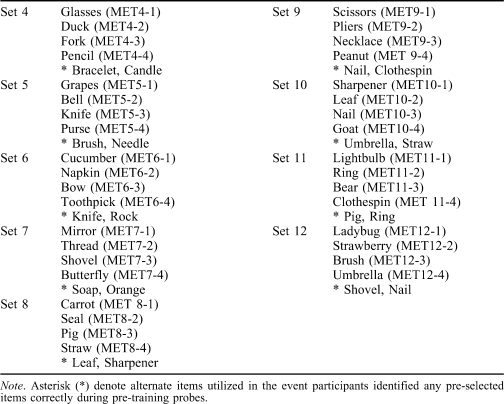

Figure 1.

Percentage of correct responses for derived tact (denoted as A-B on all graphs) and listener (denoted as B-A on all graphs) relations during pre-, post-, generalization, and maintenance probes for Lucero.

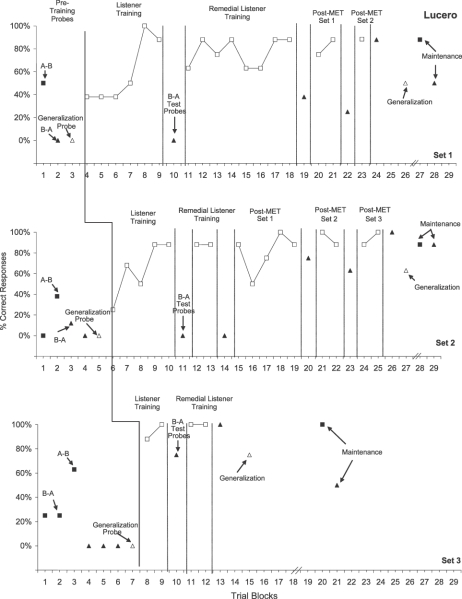

Figure 2. Percentage of correct responses for derived tact and listener relations probes for Javier.

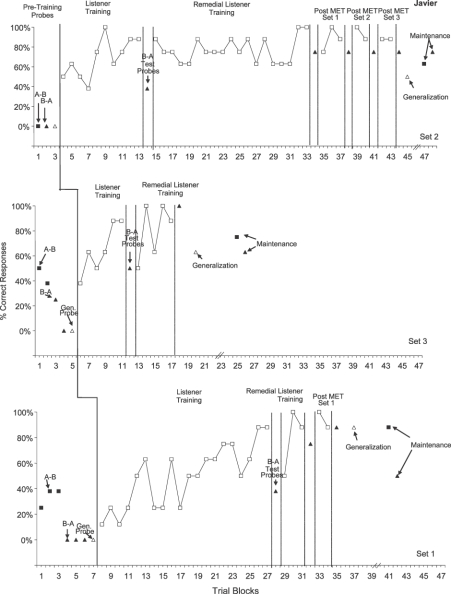

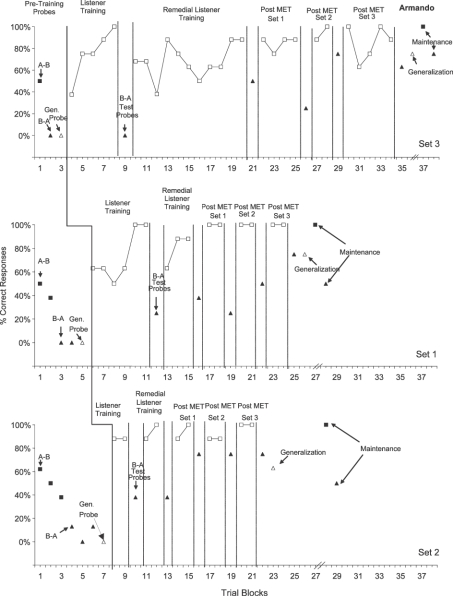

Figure 3. Percentage of correct responses for derived tact and listener relations probes for Armando.

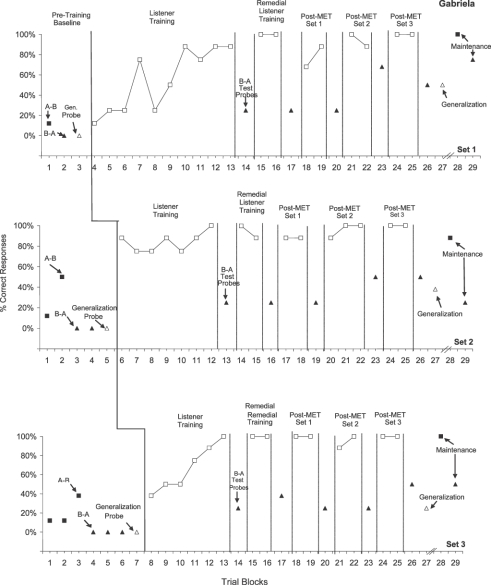

Figure 4. Percentage of correct responses for derived tact and listener relations probes for Gabriela.

The primary dependent variable for this study was the percentage of correct responses of derived intraverbal tact (B-A) relations during pre- and post-training probes. A derived relation was defined as the participant saying the name of an item correctly within 5–10 s of presentation of the item with the instruction “What is this?” by the experimenter, and in the absence of reinforcement. The presentation of an instruction to evoke a response from the participant precludes us from defining the relations to be tested as “pure” tacts as defined by Skinner (1957). However, these relations will be referred to as “tacts” for the sake of brevity throughout the manuscript. Criterion to infer the emergence of derived relations for all stimuli in a set was 7/8 trials (88%) correct responses in one trial block. All trial blocks consisted of eight trials, with each stimulus presented twice in random order.

Sessions were videotaped for the purpose of scoring interobserver (IOA) and procedural reliability. Some sessions were scored in vivo depending on the second trained observer's availability. On each trial, an agreement was scored if both observers recorded a correct or incorrect response by the participant; otherwise, a disagreement was scored. IOA was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by number of agreements plus disagreements and converting this number to a percentage. Procedural reliability was scored on a checklist created for the purpose of this study (available upon request). Procedural reliability was calculated by summing the total number of correct responses performed by the experimenter by the number of total possible responses performed by the experimenter and converting this number to a percentage.

A second trained observer recorded participant and experimenter responses during 40% of all sessions for Lucero (mean agreement 99.86%; range 88–100%); 42% of all sessions for Javier (mean agreement 99.06%; range 75–100%); 40% of all sessions for Armando (mean agreement 99.46%; range 87–100%); and 35% of all sessions for Graciela (mean agreement 96.89%; range 75–100%). The mean percentage of procedural reliability was 99.84% for Lucero (range 90–100%); 99.83% for Javier (range 96–100%), 99.83% for Armando (range 97–100%), and 99.82% for Gabriela (range 94–100%).

Procedure

Pre- and post-training probes

Participants were first assessed on correct pronunciation of all to-be-trained stimuli via echoic pre-tests (with items out of sight). If a participant failed any echoic pre-test, the item was replaced with a stimulus that the participant could pronounce correctly. Following a short break, all to-be-trained listener (A-B) and to-be-tested tact (B-A) relations were assessed in one eight-trial block probe per training set (i.e., sets 1–3). Tact probes were always presented first. Listener probes assessed relations between dictated names and their corresponding objects, and tact probes assessed oral naming of each item following an instruction presented by the experimenter. Presentation of items and trials was randomized before each session began.

The onset of listener trials was marked by the experimenter saying the name of the item for that trial or giving the instruction “Where is _______” or “Point to _______” and presenting four comparison stimuli upon the stimulus placement board in a table top simultaneous match-to-sample format. A correct response was defined as the participant pointing to or handing the item named to the experimenter. An incorrect response was defined as the participant pointing to or handing an incorrect item to the experimenter, or not responding within 5–10 s. Only the first emitted response was scored for all trials. The onset of tact trials was marked by the experimenter presenting one stimulus with the instruction “What is it?” Correct responses were defined as the participant saying the name of the item in English within 5–10 s. Incorrect responses were defined as the participant saying “I don't know,” saying the name of the item in Spanish, or the incorrect name in English. One additional probe was provided if the participant named the item correctly in Spanish. Differential consequences were not provided for correct or incorrect responses. However, in order to maintain a high density of reinforcement during testing trials, cooperative responses were reinforced and previously mastered tasks were interspersed with testing trials.

Pre-and post-generalization probes

Stimulus generalization probes were conducted in the same manner as test probes described above, with picture stimuli instead.

Listener training

Trial presentation and response definitions were the same as described for test probes above. However, programmed consequences were delivered in the following manner: Correct responses were followed by differential reinforcement in the form of descriptive praise (e.g., “That's right! That is the _______”) and delivery of a token. Tokens were exchanged for back-up reinforcers, which included a choice of several preferred items upon the conclusion of each training block. Incorrect responses were followed by corrective verbal feedback (e.g., “Try again”) and re-presentation of the trial with a model point prompt. Listener training continued until the participant demonstrated mastery criterion of 7/8 (88%) correct responses over two consecutive trial blocks. Remedial listener training was conducted in the event participants failed initial post-training probes for tact relations. Training for the remaining stimulus sets was conducted in the same manner once mastery criterion had been established for post-test probes (described below) or MET had been conducted. In addition, following training in each MET set, participants were re-exposed to listener training to ensure these relations were still within the participants' repertoire prior to conducting post-training probes for derived relations.

Multiple exemplar training

MET was implemented only if a participant failed to meet mastery criterion for all derived relations in a training set on the first two post-training probes. Each set of stimuli was designated three MET sets (see Table 2). All MET sets were trained in listener relations in the same manner described above. This was followed by tact training whereby verbal prompts were initially immediately delivered (for the first three trials) and subsequently faded. Correct and incorrect responses were defined in the same manner described above and differentially consequated with praise or corrective feedback and a model of the correct answer. Mastery criterion was set at three consecutive correct unprompted responses for each stimulus in the set currently being trained. This was followed by one trial-block conducted under extinction in order to expose participants to the contingencies under effect for the remaining post-training probes.

Maintenance probes

Follow-up probes were conducted approximately one month following the termination of all training with each respective set. Probes were conducted in the same manner described for pre- and post-training probes and the same criterion was used to infer maintenance of any derived relation.

RESULTS

All participants demonstrated emergence of derived tact relations following MET to varying degrees. As shown in Figure 1, Lucero's pre-training performance ranged from 0–50% for listener (A-B) relations. Her performance on subsequent pre-training probes indicated a slight increase in responding, but did not meet mastery criterion prior to listener training. Her scores for tact (B-A) relations ranged from 0–12%, and dropped to 0% for all subsequent pre-training probes, indicating no tacts were within her repertoire prior to training. Pre-generalization probes resulted in 0% correct responses for all training sets. Following listener training, Lucero demonstrated the emergence of derived tact relations for training set 3. Therefore, MET was implemented for training sets 1 and 2 only. For training set 1, MET was conducted with MET sets 4–5 (see Table 2). A probe conducted following training in MET set 5 indicated that Lucero met criterion for all tact (B-A) relations in set 1. For set 2, MET was conducted with MET sets 7–9, after which she met mastery criterion for tact relations in training set 2. Lucero's post-generalization scores indicated she did not meet mastery criterion, but demonstrated improvements on all training sets relative to pre-generalization scores. Maintenance probes indicated Lucero's listener relations were still within her repertoire, but tact relations had declined to 50% for all but training set 2.

Javier's results are presented in Figure 2. His performance on initial pre-training probes ranged from 0–50% for all listener (A-B) relations, and 0–25% for all tact (B-A) relations. His performance varied for subsequent pre-training listener relations, but did not meet mastery criterion prior to listener training. Javier's scores for all subsequent tact pre-training probes were at 0%. Pre-generalization probes were also 0% across all training sets. Javier met criterion for derived tact relations following listener training for training set 2. Therefore MET was implemented for training sets 1 and 3 only. For training set 1, MET was conducted with MET sets 4–6 (see Table 2). Following MET, Javier's post-training scores for training set 1 remained stable at 75%, indicating that he had not met mastery criterion. However, this was an improvement over scores following listener training. For training set 3, MET was conducted with MET set 10. Following this training, Javier scored 88% on a subsequent post-training probe, indicating all derived tact relations had emerged. Javier's post-generalization probes indicated mastery criterion was attained for training set 3 only. His performance improved for training sets 1 and 2, but did not meet mastery criterion. Maintenance data for Javier indicated only one listener relation (for training set 2) was still at mastery criterion one-month follow-up. All other scores for listener and tact relations had decreased across training sets.

Results for Armando are presented in Figure 3. Armando's pre-training probes ranged from 50–63% for listener relations, and 0–13% for tact relations. His performance decreased on all subsequent pre-training probes for both relations. Pre-generalization probes were 0% across all training sets. Armando met mastery criterion for all listener relations following listener training, and MET was conducted for all training sets to establish tact relations. For training set 1, MET was conducted with MET sets 4–6. After training in MET set 5, his post-training probe increased to 75%, and after training in MET set 6, his score dropped back to 63% indicating that two of the four relations were within his verbal repertoire (i.e., Armando consistently responded correctly for two of the four stimuli used in the training set). For training set 2, MET was conducted with MET sets 7–9. Following training in MET set 7, Armando's post-training probe was 38%, followed by a post-training probe of 50% after MET set 8 was trained. His final post-test score was 75% following training of MET set 9. This indicated two of the four relations had emerged (i.e., Armando responded correctly to a third stimuli, but only one time in the eight-trial block). For training set 3, MET was conducted with MET sets 10–12. Armando's performance following MET showed marked improvements (75%) after the first set was trained (i.e., MET set 10). Armando's performance remained at 75% following training in two additional MET sets for training set 3. Therefore, Armando did not meet mastery criterion, but demonstrated improvements following MET. Post-generalization probes indicated improvements relative to pre-generalization, but mastery criterion was not met for any training sets. Maintenance probes for both the listener and tact relations indicate correct responses on 100% for all listener relations, and 50–75% for all tact relations.

Results for Gabriela are presented in Figure 4. Gabriela's initial pre-training probes were 12% for all listener relations. These scores improved on subsequent pre-training probes, but never met mastery criterion prior to listener training. Her scores on pre-training probes for tact relations were 0% across all training sets. Pre-generalization probes were also 0% across all training sets. Gabriela met mastery criterion for all listener relations following listener training. She required MET for all training sets. For training sets 1–3 MET was conducted with MET sets 4–6; MET sets 7–9; and MET sets 10–12, respectively (see Table 2). For all training sets, MET resulted in a final post-training score of 50%, indicating two of the four relations had emerged (i.e., Gabriela responded consistently correct for two of the four stimuli in each training set). Gabriela's post-generalization scores indicated she had not met mastery criterion for any training sets, but did demonstrate improvements relative to pre-generalization scores. Finally, her follow-up scores indicated that some listener and tact relations established were still within her repertoire (with scores similar to the final post-training probe conducted one month prior for training sets 1 and 3).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present investigation was to evaluate the effects of MET across listener and speaker responses on the emergence of tact (B-A) relations in typically developing children learning English as a second language. A history with multiple exemplars appeared to make the emergence of tact relations more likely for Lucero, as evidenced by her performance in training set 3 where she met criteria without any MET. Similarly, MET was implemented with Javier for sets 1 and 3, and this appeared to facilitate the emergence of derived relations in set 3; however, derived relations were observed following listener training alone in set 2. Finally, for both Armando and Gabriela, MET was implemented across all training sets, and some derived relations emerged following this training, but neither participant met mastery criteria for all derived relations despite improvements relative to baseline performance.

These results lend support for previous studies demonstrating the effectiveness of MET with preschool children. For example, participants in the Barnes-Holmes et al. (2001a, 2001b) studies demonstrated the emergence of symmetry relations only following direct training with at least two exemplars. The objects and actions used during MET were distinct from those employed during the first part of training. Similarly, Luciano et al. (2007) demonstrated the emergence of symmetry relations following MET with different action-object and name-object relations; and results from Gomez et al. (2007) further supported these results. In addition, the effectiveness of MET with typically developing preschool children has been demonstrated for arbitrary comparative relations, which is presumably a more difficult relation to establish (Berens & Hayes, 2007). Greer and colleagues (2005) also demonstrated the effectiveness of MET by teaching 3- and 4-year-old children to match pictures of familiar items (e.g., Labrador), and then testing for the emergence of listener (point to) and speaker (name) responses for the same stimuli. After participants failed these tests, they were directly trained in all of the relations to be tested (e.g., match, point to, and name) with a different set of stimuli. Subsequent post-tests for listener and speaker repertoires resulted in the emergence of these relations with stimuli from the original training set and a third set of stimuli that were never directly trained.

RFT defines MET as a history of reinforcement responsible for responding in accordance with a range of contextually controlled arbitrarily applicable relations (Hayes et al., 2001). According to this theory, learning to name objects and events is one of the earliest and perhaps most important forms of relational responding (Barnes-Holmes & Barnes-Holmes, 2000). The present investigation lends some further support for MET as a sufficient protocol to establish derived relational responding when other training procedures are not effective. In this experiment, higher order (or overarching) operants were established as a result of MET. Higher order operants have been defined as “a class that includes within it other classes, as when generalized imitation includes all the component imitations that could be reinforced separately” (Catania, 1992, p. 377). According to this view, contingencies that are specifically arranged for some subclasses of behavior (e.g., a child imitates the experimenter clapping, jumping up and down, and spinning in a circle, and these behaviors are reinforced), may generalize to all others behaviors (e.g., any other action that the experimenter now emits is imitated by the child) as a function of a history of reinforcement for this subclass of behavior. Proponents of RFT have also defined derived relational responding as generalized operant behavior, and argue that the term generalized operant classes is a more adequate description of the functional nature of specific operant classes, of which relational framing is an example (Barnes-Holmes & Barnes-Holmes, 2000; Healy, Barnes-Holmes, & Smeets, 2000). In the present investigation, the emergence of overarching, or generalized response classes for the speaker component of verbal behavior was observed. That is, participants emitted novel responses for stimuli that had never been directly trained as a result of a history of reinforcement for responding to other stimuli within the context of the instruction “What is it?” and reinforcement provided by the experimenter for correct responses in English.

This emergent behavior may also be interpreted as the establishment of bidirectional listener-speaker component of naming, as described by Horne and Lowe (1996). Basic research to support the Naming Hypothesis has focused on describing contingencies that help to establish categorization skills for stimuli with no distinguishing physical features in common (e.g., Horne, Hughes, & Lowe, 2006). The emergence of speaker relations following training in listener relations is one important component of naming that has been described and empirically demonstrated in previous research following training with multiple exemplars (e.g., Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Greer et al., 2005; Lowe, Horne, Harris, & Randle, 2002).

Some limitations of the present investigation should be noted. First, MET was always accompanied by remedial listener training with the original training set. The rationale for this remedial training was to ensure that participants had listener relations well within their repertoire prior to presenting post-training probes for derived tact relations. However, the presentation of remedial listener training could be viewed as a potential confound for MET. That is, re-presentation of listener relations prior to probes for the speaker (tact) relations makes the emergence of the listener-speaker responses less clear. Previous studies on the effectiveness of MET have demonstrated the emergence of bidirectional relations without additional remedial training (e.g., Greer, Stolfi, et al., 2005; Greer, Yuan et al., 2005; Nuzzolo-Gomez & Greer, 2004). Similar to the present study, these investigations specifically evaluated the effectiveness of MET on the bidirectional relation rather than the emergence of learning words as a speaker and listener incidentally. To alleviate this potential confound, future investigations may stagger MET across a differing number of listener training and testing cycles via a multiple baseline across participants, or across a differing amount of training sets.

Second, there were mixed results with respect to the relationship between MET and the establishment of derived relations. Replications and extension of this methodology are needed to further evaluate the effectiveness of this procedure with typically developing children and other populations. Future studies may incorporate a more stringent mastery criterion in order to determine whether derived relations have in fact emerged. In addition, although several steps were taken in an attempt to control levels of variability and difficulty of stimuli used in the study (i.e., by counterbalancing training sets across participants, conducting echoic pre-training probes, selecting stimuli names of the same phonetic length), some within-stimulus differences may have existed across participants. It may be the case that these items were generally more difficult to pronounce or that participants consistently assigned other names to these stimuli (e.g., Javier consistently named the “knife” a “fork”). Future research should investigate a more systematic way of determining level of difficulty for stimuli selected for training such as evaluating the morphemes of words to be trained. Errors made by participants may be accounted for by the interference of first language on second language acquisition (Houmanfar, Hayes, & Herbst, 2005). Previous research on the interference of first language has demonstrated that the percentage of correct responses during testing conditions is often higher for first language than second language test trials (Houmanfar et al., 2005; Washio & Houmanfar, 2007). A longer history of reinforcement for responding in the first language and the requirement of establishing relations between verbal stimuli of the first language with the second language may help account for these differences. In the present study, some errors frequently made by Armando and Gabriela consisted of naming stimuli correctly in Spanish (e.g., consistently saying “calsetin” for “sock”).

Finally, although participants' performance was assessed for stimulus generalization and maintenance, results demonstrated that not all relations generalized or maintained at one month follow-up. Future studies might evaluate stimulus generalization using a more naturalistic approach (e.g., naming items in a picture book); and evaluate the potential explanations for the lack of maintenance of specific stimuli. Skills should also be assessed for longer periods of time.

Despite these limitations, the experiments conducted may serve as initial work in the study of second language acquisition from a behavior analytic perspective. Specifically, the use of MET to teach individuals a second language may have important implications for current language training programs. It may be the case that individuals have some listener responses (i.e., can point to objects) within their repertoire, and that MET helps to facilitate the emergence of object-name relations. The differential reinforcement implicit in MET may provide the necessary history for derived relations to emerge.

Footnotes

This project was supported by a grant awarded by the Verbal Behavior Special Interest Group, and is based on a portion of a dissertation submitted by the first author to fulfill partial requirements of a doctoral degree under supervision of the second author from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. We thank Gloria Radek and the staff at Su Casa Headstart in Cobden, IL for help with participant recruitment. We also thank Anna Pettursdotir, five anonymous reviewers, and dissertation committee members Tony Cuvo, Paula Davis, and Michael May for comments on earlier versions; and Nicole Fuscaldo and Shannon Sidener-Sayre for assistance with reliability data. Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to: Rocio Rosales, Ph.D., BCBA-D, Department of Psychology, Youngstown State University, One University Plaza, Youngstown, OH 44555 (e-mail: rrosales@ysu.edu).

REFERENCES

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y. Explaining complex behavior: Two perspectives on the concept of generalized operant classes. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Exemplar training and a derived transformation of function in accordance with symmetry. The Psychological Record. 2001a;51:287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Exemplar training and a derived transformation of function in accordance with symmetry: II. The Psychological Record. 2001b;51:589–603. [Google Scholar]

- Berens N.M, Hayes S.C. Arbitrarily applicable comparative relations: Experimental evidence for a relational operant. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:45–71. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.7-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania C.A. Learning (3rd ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.O, Heron T.E, Heward W.L. Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L.L, O'Neill R.E. Use of response cards with a group of students with learning disabilities including those for whom English is a second language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:219–222. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorile C.A, Greer D.G. The induction of naming in children with no prior tact responses as a function of multiple exemplar histories of instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2007;23:71–87. doi: 10.1007/BF03393048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia E, Baer D.M, Firestone I. The development of generalized imitation within topographically determined boundaries. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1971;4:101–112. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S, Lopez F, Baños-Martin C, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D. Exemplar training and a derived transformation of functions in accordance with symmetry and equivalence. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R.D, Stolfi L, Chavez-Brown M, Rivera-Valdes C. The emergence of the listener to speaker component of naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:123–134. doi: 10.1007/BF03393014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R.D, Yuan L, Gautreaux G. Novel dictation and intraverbal responses as a function of a multiple exemplar instructional history. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:99–116. doi: 10.1007/BF03393012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guess D, Sailor W, Rutherford G, Baer D.M. An experimental analysis of linguistic development: The productive use of plural morphemes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:297–306. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. Relational frame theory: A post Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Plenum Publishers; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy O, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M. Derived relational responding as generalized operant behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2000;74:207–227. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2000.74-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne P.J, Hughes C.H, Lowe C.F. Naming and categorization in young children: IV: Listener behavior training and transfer of function. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85:247–273. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.125-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne P.J, Lowe C.F. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:185–241. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne P.J, Lowe C.F, Randle V.R.L. Naming and categorization in young children: II. Listener behavior training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;81:267–288. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.81-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R.D, Baer D.M. Multiple-probe technique: A variation of the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:189–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmanfar R, Hayes L.J, Herbst S.A. An analog study of first language dominance and interference over second language. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:75–98. doi: 10.1007/BF03393011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce B.G, Joyce J.H. Using stimulus equivalence procedures to teach relationships between English and Spanish words. Education and Treatment of Children. 1993;16:48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C.F, Horne P.J, Harris F.D.A, Randle V.R.L. Naming and categorization in young children: Vocal tact training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:527–549. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C.F, Horne P.J, Hughes J.C. Naming and categorization in young children III: Vocal tact training and transfer of function. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2005;83:47–65. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.31-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano C, Gomez-Becerra I, Rodriguez-Valverde M. The role of multiple exemplar training and naming in establishing derived equivalence in an infant. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;87:349–365. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.08-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid D, Torres I. An experimental approach to language training in second language acquisition: Focus on negation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1986;19:203–208. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1986.19-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzolo-Gomez R, Greer R.D. Emergence of untaught mands or tacts of novel adjective-object pairs as a function of instructional history. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;20:63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03392995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettursdotir A.I, Hafliđadóđttir R.D. A comparison of four strategies for teaching a small foreign-language vocabulary. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:685–690. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petursdottir A.I, Ólafsdóttir A.R, Aradóttir B. The effects of tact and listener training on the emergence of bidirectional intraverbal relations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:411–415. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson D.A.D, Grabavac D.M, Parsons J.A. Intraverbal stimulus response reversibility: Fluency, familiarity effects, and implications for stimulus equivalence. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1997;14:19–40. doi: 10.1007/BF03392914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson D.A.D, Parsons J.A. Selection-based versus topography-based responding: An important distinction for stimulus equivalence. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2000;17:105–128. doi: 10.1007/BF03392959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamune S, Smith S.L. The relationship between pronunciation and listening discrimination when Japanese natives are learning English. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:577–578. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. Cambridge, MA: Prentice-Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Washio Y, Houmanfar R. Role of contextual control in second language performance. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2007;23:41–56. doi: 10.1007/BF03393046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]