Abstract

Objective

Pulmonary complications in systemic sclerosis (SSc), including pulmonary fibrosis (PF) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), are the leading cause of mortality. We compared the molecular fingerprint of SSc lung tissues and matching primary lung fibroblasts to those of normal donors, and patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH).

Methods

Lung tissues were obtained from 33 patients with SSc who underwent lung transplantation. Tissues and cells from a subgroup of SSc patients with predominantly PF or PAH were compared to those from normal donors, patients with IPF, or IPAH. Microarray data was analyzed using Efficiency Analysis for determination of optimal data processing methods. Real time PCR and immunohistochemistry were used to confirm differential levels of mRNA and protein, respectively.

Results

We identified a consensus of 242 and 335 genes that were differentially expressed in lungs and primary fibroblasts, respectively. Enriched function groups in SSc-PF and IPF lungs included fibrosis, insulin-like growth factor signaling and caveolin-mediated endocytosis. Functional groups shared by SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs included antigen presentation, chemokine activity, and IL-17 signaling.

Conclusion

Using microarray analysis on carefully phenotyped SSc and comparator lung tissues, we demonstrated distinct molecular profiles in tissues and fibroblasts of patients with SSc-associated lung disease compared to idiopathic forms of lung disease. Unique molecular signatures were generated that are disease- (SSc) and phenotype- (PF vs PAH) specific. These signatures provide new insights into pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets for SSc lung disease.

Introduction

Pulmonary complications in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are the leading cause of mortality (1). These complications include pulmonary fibrosis (PF), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), or both. Clinical evidence of interstitial lung disease is detected in about 40% of SSc patients by chest radiograph and an additional 40% by high-resolution computerized tomography (2). The prevalence of PAH in SSc is estimated between 5–48% depending on detection methods (1, 3). Current therapies for PF and PAH have modest benefit in clinical outcomes and patients often require lung transplantation (4, 5). Mechanisms that lead to development of pulmonary disease in SSc remain poorly understood.

High throughput technologies such as microarrays have proven to be a useful tool in understanding the molecular mechanisms of disease processes. A global analysis of gene expression can generate multiple insights into disease pathogenesis. Previous studies of global gene expression in SSc used dermal tissues and fibroblasts (6–9), including a study comparing dermal fibroblasts from twins discordant for SSc (10). One study examined gene expression patterns in cells derived from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with SSc and showed differences in inflammatory profiles (11). Gene expression patterns have been examined in lung tissues from patients with various forms of PF and PAH using whole lung tissues and micro-dissected fibroblastic foci in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (12–14) and lung tissues from sporadic and familial idiopathic PAH (IPAH) (15). An analysis of gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from individuals with PAH including those with idiopathic and SSc-associated PAH (16, 17) distinguished individuals with PAH from healthy donors and identified potential markers for PAH. However, no published study to date has applied microarray technology to SSc lung tissues.

In this study, we performed molecular profiling of lung tissues and primary fibroblasts cultured from these tissues. We subdivided SSc patients into those with predominantly a PF or PAH phenotype and compared their molecular profiles to those of lung tissues from patients with idiopathic forms of lung disease (IPF and IPAH). Our study generated unique molecular profiles that are shared in SSc lungs and fibroblasts (disease specific) and profiles shared between PF or PAH lungs and fibroblasts (phenotype specific). These molecular profiles provide novel insights in the pathogenesis of a devastating complication of SSc.

Methods

Study population

Lung tissues were obtained from patients with SSc, IPF and IPAH who underwent lung transplantation at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board. All patients with SSc met diagnostic criteria outlined by the American College of Rheumatology (18). Severe PF in SSc was defined as the presence of restrictive physiology with a forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 55% of predicted. SSc-related PAH was based on the hemodynamic criteria with mean PA pressure (mPAP) greater than 25 mm Hg and pulmonary capillary occlusion pressure <15 mm Hg (19). Patients with IPF were confirmed to have usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pathology without evidence of other known causes and no associated PAH. Patients with IPAH were also diagnosed using similar hemodynamic parameters with no known cause or connective tissue disorder (19). Normal lung tissues were obtained from organ donors whose lungs were not used for lung transplantation. Lung tissues were frozen prior to extraction of total RNA. In parallel, fibroblasts were cultured from the same lungs as previously described (20). Fibroblasts in passage 3 were cultured in 0.5% FBS for 24 hours prior to RNA and protein extraction.

RNA processing

Total RNA was extracted from fibroblasts and frozen lung tissues using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis as well as analysis of samples using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with a RIN score of 6 or greater. Microarray analysis was performed using HumanRef-8v3.0 BeadChips (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) containing 25,440 annotated genes. After sample hybridization, BeadChips were scanned using Illumina BeadChip Array Reader.

Data Analysis

Differentially expressed genes were identified by efficiency analysis (EA) (21) using AutoEA software (Shi and Lyons-Weiler, unpublished) that automates efficiency analysis (22). Efficiency analysis determines the optimal normalization, transformation and feature selection combination that leads to the most internally consistent gene set.

For data visualization, raw expression values were normalized to the median value and square root transformed. Average linkage clustering was performed using Cluster 3.0 software (23) using a Pearson correlation. Cluster trees and gene expression heat maps were visualized using Java TreeView software (24). Enriched functional groups were determined using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City CA) and Gene Ontology Tree Machine (GOTM) Software packages (25).

Some of the analyses were repeated using the more “classical” method Significance Analysis of Microarray (SAM) (26). The two comparisons were: 1) SScPF lung vs NL lung, and 2) SScPF fibro vs NL fibro. Data from all 18,630 genes were used. Data were median normalized and square root transformed. SAM’s delta measurement was set for each split iteration to use approximately the same number of differentially expressed genes (336) as were found by the efficiency-analysis optimized analysis. ‘n’ ranged from 100 to 345 for fibro, and 242 to 250 for lung. Efficiency analysis parameters N3 and 0% were averaged among splits to achieve the SAM fibro and lung efficiency analysis results.

Quantitative PCR

The same total RNA aliquot extracted from lung tissues and fibroblasts was used to validate gene expression. Complementary DNA was generated using High Capacity RNA-to-DNA Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed using a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with pre-designed Taqman Gene Expression Assays containing FAM™ dye-labeled probes. Gene expression levels were normalized to β-actin. Relative expression levels of diseased tissues and fibroblasts were compared to RNA levels in normal lung tissues or fibroblasts using the comparative CT method formula 2−ΔΔCt.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed on fibroblasts lysates that were collected in lysis buffer as previously described (20). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-FHL2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-sFRP-1, anti-lysyl oxidase (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), and anti-β-actin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO). Signals were detected using chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 6 μm sections of paraffin-embedded lung tissues as previously described (27). Sections were incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-IGFBP7, anti-CC10 (SCGB1a1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz CA), anti-metallothionein (Dako, Glostruo, Denmark) or isotype control (Lab Vision, Freemont, CA). After incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame CA), bound antibody was detected using Vectastain ABC kit (Vector) and AEC red (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin and images captured on Olympus Provis AX70 (Olympus Imaging, Center Valley, PA).

Results

Demographics and patient characteristics

Lung tissues were available from 33 SSc patients who underwent lung transplantation for PF and PAH (Supplement Table 1). Patients with SSc showed significant heterogeneity of clinical variables, including varying degrees of severity of PF and PAH. Fifteen SSc individuals had severe PF without PAH (FVC 18–46% of predicted, mPAP 13–26 mmHg) and 6 individuals had severe or moderately severe PF and PAH (FVC 34–59%, mPAP 30–50 mmHg). Four SSc patients had moderate PF with PAH (FVC 60–64%, mPAP 38–62 mmHg), and 7 had PAH with no evidence of PF, or PAH with mild PF (FVC 74–88%, mPAP 31–60 mmHg).

A subset of SSc patients with a predominance of severe PF (n=9) or PAH (n=9) were selected for a comparison of gene expression patterns (Table 1). Subjects in the SSc-PF group had severe PF without evidence for PAH (n=9, FVC 31.3%, mPAP 20.4 mmHg). The SSc-PAH group had severe PAH with normal or mild restrictive spirometry (n=9, FVC 76.1%, mPAP 48.0 mmHg). There were no differences in age or gender between SSc-PF or SSc-PAH groups. Consistent with previous studies, the majority of SSc-PF patients had diffuse lung disease with anti-Scl-70, Th/To or U11/U12 RNP autoantibodies that are known to be associated with PF in SSc (28). The majority of SSc-PAH individuals had limited cutaneous disease with anti-centromere or RNA polymerase antibodies. Gene expression patterns in SSc-PF and SSc-PAH lung tissues and fibroblasts were compared to the corresponding idiopathic forms of lung disease. Individuals with IPF had severe PF without PAH (n=10, FVC 42.5%, mPAP 22.7 mmHg). Individuals with IPAH had severe PAH without evidence of connective tissue disease or other known causes (n=8, FVC 80.3%, mPAP 60.0 mmHg). Primary fibroblasts were cultured from lungs of all these individuals except for the IPAH group where fibroblasts were available from 6 individuals.

Table 1.

Demographic information of study subjects by disease category

| SSc-PF | SSc-PAH | IPF | IPAH | Normal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=9 | n=9 | n=10 | n=8 | n=9 | |

| Mean age, (years) | 49.1 | 52.1 | 62.8 | 35.7 | 53.0 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 4 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 4 |

| female | 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 5 |

| Smoking history | |||||

| yes | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| no | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| n/a | 3 | ||||

| SSc variant, no. | |||||

| Limited | 2 | 6 | |||

| Diffuse | 5 | 2 | |||

| n/a | 2 | 1 | |||

| Autoantibody | |||||

| Scl-70 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Th/To | 1 | 1 | |||

| U11/U12 RNP | 1 | 2 | |||

| Centromere | 0 | 5 | |||

| RNA Polymerase | 0 | 2 | |||

| n/a | 4 | 0 | |||

| Physiologic parameters | |||||

| mean ± standard deviation | 31.3 ± 9.1 | 76.1±9.2 | 42.5±8.2 | 80.3±15.1 | n/a |

| FVC % | 25.4±7.0 | 36.3±20.5 | 36.2±13.2 | 55.6±22.7 | n/a |

| DLCO % | 1.51±0.6 | 2.51±1.0 | 1.30±0.6 | 2.02±1.9 | n/a |

| FVC %/DLCO % | 20.4±4.2 | 48.0±9.9 | 22.7±4.7 | 60.0±13.3 | n/a |

| Mean PA pressure mmHg | |||||

n/a: not available

Gene expression profiles of lung tissues

The gene expression profile of each disease group (SSc-PF, SSc-PAH, IPF and IPAH) was compared to that of normal lung tissues. Using Efficiency Analysis (21), we tested each comparison to determine the optimal methods for data transformation, normalization, and tests for differential expression. Efficiency Analysis did not reveal a single optimal method for all comparisons. Therefore, a consensus set of genes with a consensus score greater than 50% was determined by the top 20% performing methods of analysis. The ranking criterion used was the area under the efficiency curve (AU-EC).

Consensus efficiency analysis identified 242 genes that were differentially expressed (figure 1A, supplemental table 2). In SSc-PF and SSc-PAH lungs, 73 and 83 genes, respectively, were differentially expressed compared to normal lungs. The top 20 up-and down-regulated genes in SSc-PF and SSc-PAH lungs are shown in supplemental tables 3–4. Both SSc groups had concordant expression of 39 genes (figure 1C, Supplement Table 5). In IPF and IPAH lungs, 73 and 85 genes, respectively, were differentially expressed compared to normal lungs. SSc-PF and IPF lung tissues shared 53 differentially expressed genes (Supplement Table 6–7). SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs had concordant expression of 44 genes (Supplement Table 8–9).

Figure 1.

Gene expression profiles of SSc, IPF and IPAH lung tissues. (A) Efficiency analysis identified 242 genes with a consensus score greater than 50% by the top 20% performing methods. SSc samples were ordered from left to right by lowest (severe PF, no PAH) to highest FVC (no PF, severe PAH) as indicated in Table 1. All genes with J5 and fold change scores in each group can be viewed in supplement table 2. (B) The cluster patterns reveal genes that are up-regulated in SSc and IPF (Cluster 1), up-regulated in SSc-PF and IPF (Cluster 2), and up-regulated in SSc-PAH and IPAH (Cluster 3). Clusters of genes were also down-regulated in SSc-PF and IPF (Cluster 4) and down-regulated in all SSc and IPF (Cluster E). (C) Venn diagrams show number of shared and unique genes in SSc-PF, SSc-PAH, IPF and IPAH groups. Shared and unique genes are shown in supplement tables 5–9. (D) Unsupervised clustering of all lung samples using all 18,630 genes show clustering of samples by disease phenotype (PF or PAH).

We analyzed the 242 genes that were differentially expressed by a consensus efficiency analysis using unsupervised hierarchical clustering. The resulting dendrogram (figure 1D) revealed similarities in gene expression in fibrotic lungs (SSc-PF and IPF) and PAH lungs (SSc-PAH and IPAH). Some SSc-PAH lungs clustered with fibrotic lungs. This likely reflects the fact that many SSc patients had mild fibrotic changes in the lungs based on histological and physiologic evaluation (Table 1). Additionally, a cluster of genes that were up-regulated in SSc and IPF lungs but not IPAH and normal lungs (figure 1B, Cluster 1) included multiple collagen genes and other factors known to be increased in fibrosis. Genes that showed increased expression in SSc-PF and IPF lungs but not SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs (Cluster 2) included matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7, insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP) and osteopontin, which have been previously implicated in pulmonary fibrosis (12, 20). Genes that were increased in SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs (Cluster 3) included chemokines and hemoglobin genes.

Gene expression profiles were further analyzed to determine the enriched functional groups for each diseased lung compared to normal lungs using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis and GOTM (figure 3A, Supplement Table 10). The SSc-PF and IPF groups shared enriched functional groups in their gene expression profiles. As expected, fibrotic lungs were enriched for genes involved in fibrosis, which included genes for collagen types I and III, IGFBPs, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases 1 (TIMP-1) and interferon gamma receptor. Interestingly, genes involved in IGF signaling also had a significant signature in the gene expression profiles of SSc-PF and IPF. These included genes such as IGFBPs, secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor (SLPI) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (figure 3A). PAH lungs also shared functional groups that were enriched in their gene expression profiles, including interferon, IL-4, IL-17 and antigen presentation signaling. Specific genes included chemokines CCL-2, CXCL10 and HLA-DR and –A genes.

Figure 3.

Enriched functional groups of SSc, IPF and IPAH lungs (panel A) and fibroblasts (panel B). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis and Gene Ontology Tree Machine software programs identified enriched function groups in gene expression patterns of SSc-PF, SSc-PAH, IPF, and IPAH fibroblasts. Functional classes that have a –log(P-value) greater than 1.3 (or P-value of 0.05 or less), as indicated by the dotted line, signifies impacted pathways that may be involved in disease process.

Gene expression profiles of lung fibroblasts

Similarly to lung tissues, efficiency analysis of gene expression of primary lung fibroblasts did not reveal one optimal method for data analysis. Therefore, a consensus set of 335 genes was identified using the top performing methods (figure 2A, supplement table 11). In SSc-PF and SSc-PAH fibroblasts, 78 and 97 genes, respectively were differentially expressed compared to normal fibroblasts. Top up- and down-regulated genes in SSc-PF and SSc-PAH fibroblasts are listed in supplemental tables 12–13. Both SSc groups shared 31 differentially expressed genes (figure 2C, Supplement Table 14). In the IPF and IPAH fibroblasts, 96 and 83 genes, respectively, were differentially expressed compared to normal fibroblasts. The SSc-PF and IPF fibroblasts shared 19 differentially expressed genes (Supplement Table 15–16). Cluster analysis identified IGFBP-3 and -7, lysyl oxidase and sulfatase as genes up-regulated in SSc-PF and IPF fibroblasts (figure 2B, Cluster 8). SSc-PAH and IPAH fibroblasts shared 24 differentially expressed genes (Supplement Table 17–18). Genes strongly up-regulated in IPAH fibroblasts included chemokines and interleukins such as IL-6, IL-8, and IL-13 receptor (figure 2B, Cluster 6).

Figure 2.

Gene expression profiles of SSc, IPF and IPAH fibroblasts. (A) Efficiency analysis identified 335 genes with a consensus score greater than 50% by the top 20% performing methods. All genes and fold change scores in each group can be viewed in supplement table 7. (B) The clustering pattern shown in finer detail on the right panel shows clusters of genes that are up-regulated in IPAH fibroblasts (Cluster 6), in IPF, SSc-PF and IPAH fibroblasts (Cluster 7), and in IPF and SSc-PF (Cluster 8). Clusters of genes were also down-regulated in IPAH fibroblasts (Cluster 9) and coordinately down-regulated in SSc and IPF fibroblasts (Cluster 10). (C) Venn diagrams show the number of shared and unique genes in SSc-PF, SSc-PAH, IPF and IPAH fibroblast groups. Shared and unique genes are listed in supplement tables 14–18. (D) Unsupervised clustering of fibroblast samples using all 18,630 genes.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis and GOTM software programs were used to identify enriched functional groups in lung fibroblasts (figure 3B, Supplement Table 19). All 4 fibroblast groups (SSc-PF, SSc-PAH, IPF and IPAH) showed enrichment of genes involved in fibrosis, which suggests that fibroblast function is altered in these disease states. SSc lung fibroblasts shared significant functional groups in calcium, nitric oxide, and phosphodiesterase signaling. In parallel to whole lung tissues, IPAH fibroblast gene expression profiles were enriched in IL-6, -8, and -17 signaling, and had a larger number of differentially expressed genes compared to IPAH lungs, suggesting that IPAH fibroblasts may be relevant cells to examine in this disease. Genes involved in caveolar-mediated signaling were significant in SSc-PAH and IPAH fibroblasts, but not SSc-PF and IPF fibroblasts (figure 3B). This is in contrast to the lung tissue microarray dataset where SSc-PF and IPF lung tissues were significantly enriched for caveolar-mediated signaling (figure 3A).

Comparison of J5, FC and SAM via Efficiency Analysis

Efficiency analysis showed that J5 and fold change (FC) were the most internally consistent feature selection methods across all comparisons. To confirm this observation, we compared these methods to the “traditional” method SAM (21, 29) for SSc-PF vs Normal lung and SSc-PF vs Normal fibroblast comparisons (Supplement Table 20). Gene lists from J5 and FC results were also compared to SAM results (Supplement Table 21). In general, the internal consistency of SAM is less than that of J5. In both lung and fibroblast results, the percentage overlap of SAM is considerably lower than both J5 and FC. The same holds true for the gene list comparisons as the J5 and FC results were more consistent.

Confirmation of microarray results

Microarray results were confirmed by real time PCR of mRNA samples (figure 4A). Genes that were selected for confirmation by PCR were those not previously reported to be differentially expressed in SSc, IPF or IPAH. As seen in microarray analysis, all 4 diseased lungs (SSc-PF, SSc-PAH, IPF and IPAH) showed increased mRNA of secretoglobins 1a1 and 3a1 with quantitative PCR. Also IGFBP-7 expression was increased in IPF, SSc-PF and SSc-PAH lungs, but not IPAH lungs. CXCL10 (also known as IP-10) showed increased expression in all four groups with larger increases in SSc-PAH and IPAH (19.5- and 14.8-fold increased expression, respectively), whereas expression of ficolin 3 (FCN3) was decreased in IPF and SSc lung tissues, but not in IPAH lung tissues. These results demonstrate concordant increase or decrease in expression of individual genes that are unique for a lung phenotype (PF or PAH) or disease type (SSc).

Figure 4.

Validation of genes differentially expressed in lung tissues. A: Messenger RNA levels were analyzed by real time PCR. Each sample was performed in triplicate and the average was normalized to b-actin mRNA levels. The relative expression values are displayed as the fold change for each gene relative to normal lungs. B: Localization of IGFBP7, secretoglobin 1a1 (SCGB1a1) and metallothionein in lung tissues (red-brown stain). IGFBP7 has high expression in fibrotic tissues (SSc-PF and IPF) and to a lesser degree in SSc-PAH lungs. SCGB1a1 was detected in all disease groups, but not normal lungs. Metallothionein was detected in SSc-PF airway epithelium and in SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs, but not IPF or normal lungs. Images were taken at 400x.

Immunohistochemistry was used to confirm differential gene expression at the protein level (figure 4B). IGFBP-7 protein levels were notably high in fibrotic lung tissues. No IGFBP-7 was detected in IPAH and normal lungs. Secretoglobin 1a1 (also known as SCGB1a1, CC-10, CCSP, uteroglobin) showed elevated expression in all 4 disease groups compared to normal lungs. Metallothionein was detected in airway epithelium of SSc-PF lungs. SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs also had detectable metallothionein that was scattered in alveolar epithelial cells. No staining for metallothionein was observed in IPF and normal lungs.

Expression of selected genes that were aberrantly expressed in primary pulmonary fibroblasts was confirmed by quantitative PCR using the same mRNA aliquot used for microarray analysis (figure 5A). Podocan, which is a collagen-binding protein that affects cell proliferation and migration (26), was increased in SSc fibroblasts, but not in IPF or IPAH fibroblasts. SSc-PF and IPF fibroblasts showed increased expression of lysyl oxidase. Fibroblasts from IPF and SSc, but not IPAH lungs, also showed an increase in four-and-a-half-LIM-2 (FHL2) mRNA. Real time PCR findings matched mRNA expression patterns detected in the microarray analysis.

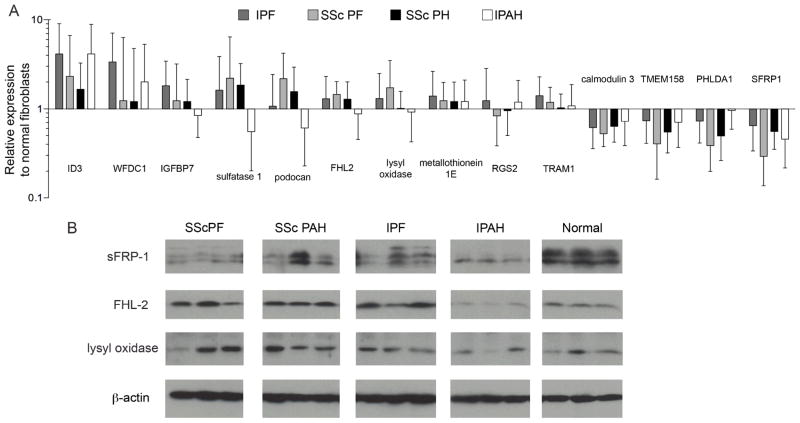

Figure 5.

Validation of genes differentially expressed fibroblasts. A: Real time PCR was performed on mRNA extracted from primary pulmonary fibroblasts. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and average values were normalized to b-actin mRNA levels. Relative expression values are displayed as the fold change compared to normal fibroblasts. B: Western Blot of fibroblast lysates reveals differential protein levels of secreted Frizzled-related protein-1 (sFRP-1), four-and-a-half-LIM-domain-2 (FHL2) and lysyl oxidase.

Further confirmation of corresponding protein levels in fibroblasts was obtained by immunoblotting of cell lysates (figure 5B). Secreted Frizzled-related protein-1 (sFRP-1) had reduced levels in SSc-PF fibroblasts compared to normal cells. FHL2 was increased in SSc-PF, SSc-PAH and IPF fibroblasts, but not IPAH fibroblasts. Lastly, lysyl oxidase was increased in SSc-PF, SSc-PAH and IPF fibroblasts, but not IPAH, compared to normal donor fibroblasts.

Discussion

Pulmonary disease in SSc can exist as a heterogeneous combination of PF and PAH. In order to examine molecular mechanisms in these two complications, we completed global gene expression analysis of lung tissues from 33 patients with SSc and further analyzed gene expression of a subset of SSc lung tissues that had either fibrosis or pulmonary hypertension, and from whom primary fibroblasts were available. We compared the SSc-PF and SSc-PAH subsets to IPF and IPAH. Although some clinical features may differ between SSc and idiopathic forms of lung disease, histopathological characteristics are similar. SSc-related pulmonary fibrosis can present with a UIP histologic pattern that is indistinguishable from IPF. Although non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is more common than UIP in SSc (30, 31), individuals with a UIP pattern have worse prognosis, which is reflected in our cohort of explanted SSc-PF lungs where all had UIP patterns. Isolated pulmonary hypertension in SSc shares similar histologic abnormalities in pulmonary vasculature to idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Therefore, comparing molecular profiles of SSc-associated pulmonary complications with their idiopathic forms identifies molecular mechanisms that are disease-specific (SSc) or phenotype-specific (PF vs. PAH).

We used Efficiency Analysis (21) in our approach to data analysis to generate a consensus list of differentially expressed genes. This method allows for the comparison of multiple testing methods and determines the internal consistency of various feature selection methods so that a consensus list of genes is generated. Although other microarray studies often select for genes that are above a certain fold-change value, we have chosen not to include or exclude genes based on the fold-change value because an arbitrary threshold may exclude biologically relevant changes in gene expression pattern. The advantages and pitfalls associated with various methods of microarray analysis have been reviewed extensively (32) and are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Our analysis of SSc lung tissues showed gene expression patterns that were also identified in skin tissues (6–10). Collagen types I and III, CTGF and thrombospondin-1 were increased in SSc lung tissues (Supplementary Table 2) as well as in SSc skin biopsies (6, 7), suggesting that these molecules are markers of fibrosis in multiple organs in SSc. Unlike skin biopsies, lung tissue is fairly limited in SSc since lung biopsies are not routinely performed. Subsequently, there are relatively few studies examining SSc lung tissues. One previous study examined gene expression in SSc lung fibroblasts stimulated with TGF-β (33). However, the total number of SSc samples was small (n=3) and characteristics of lung disease in these patients were limited. To our knowledge, our study constitutes the largest molecular profiling analysis of SSc lung tissues.

SSc-PF and IPF lungs and fibroblasts were enriched for genes involved in fibrosis such as collagens, and TIMPs (supplement table 6). Genes involved in IGF signaling, especially proteins with high affinity for IGF, such as IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 as well as low-affinity IGF binding proteins, such as IGFBP-7, CTGF and cyr61, were also aberrantly expressed in diseased lungs and fibroblasts.

Differentially expressed families of genes also included those associated with actin binding, cell contraction, motility and integrin signaling such as MYH11, ACTA2, ACTG2, and MRLC2 (supplement table 6), possibly reflecting differentiation of cells to a myofibroblastic phenotype.

Molecular profiling of primary fibroblasts derived from the same lung tissues was used as a complementary approach to identify differential gene expression contributions from a single cell type. Several of the genes aberrantly expressed in lung tissues were also identified in fibroblasts and included components of IGF signaling, fibrosis, and myofibroblast differentiation. In addition, we demonstrated increased FHL2 expression in IPF and SSc lung fibroblasts (figures 5). FHL2 is up-regulated in fibroblastic foci of IPF lungs (14), which confirms that our findings in early passage primary lung fibroblasts are consistent with disease processes in vivo. FHL2 is up-regulated in smooth muscle-actin-producing cells in wounded human skin and mediates the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts (34). Furthermore, FHL2 binds Smads and activates TGF-β-like responses independent of the TGF-β receptor (35), and binds IGFBP-5, a pro-fibrotic factor that is aberrantly expressed in fibrotic lung and skin (20, 36). Increased FHL2 expression in fibroblasts may thus contribute to the fibrotic phenotype by promoting fibroblast proliferation and migration via activation of transcription factors.

We show that sFRP-1 is decreased in fibroblasts from fibrotic lungs (figure 5). SFRP-1 acts as an antagonist to the Wnt signaling pathway. Previous studies have shown activation and up-regulation of Wnt and β-catenin in IPF lung tissues (37). Aberrant regulation of other members of this pathway such as WISP2 were also noted and suggest the presence of upregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling similar to IPF, thus further confirming coordinate expression of pulmonary fibrosis genes irrespective of the underlying disease (SSc or idiopathic). This also demonstrates a convergence at the molecular level in lung tissues with a histologic pattern of UIP.

Overall, our microarray analysis of SSc lung tissues revealed unique gene expression profiles that matched with corresponding idiopathic forms of lung disease. Both SSc-PF and IPF shared enriched functional groups in genes previously implicated in pulmonary fibrosis, such has IGFBPs and caveolin-mediated endocytosis (9, 20, 38). As well as aberrant regulation of genes such as collagens, MMPs, TIMPs, IGFBPs, that were identified in previous microarray studies of fibrotic lungs (12–14).

Analysis of gene expression in PAH lungs also revealed novel gene expression patterns that have not been previously reported (15). This difference may be due to the smaller sample size of the previous study. SSc-PAH and IPAH lung tissues were enriched for genes involved in chemokine signaling and antigen presentation pathways, suggesting the presence of inflammation in both forms of PAH. Both CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and CCL-2 are chemokines that are in the top 20 up-regulated genes in SSc-PAH lungs (Supplement Table 5). Increased fractalkine and CCL-2 expression in PAH lungs may induce vascular smooth muscle proliferation and vascular remodeling. Our data also shows aberrant mRNA expression of MHC molecules and transporter 1 (TAP1) in SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs (Supplement Table 2). Alterations in these antigen presentation genes may be a result of infiltration of immune cells and suggest that inflammation activation of innate immunity, possibly via toll-like receptors, may play a role in the development and/or progression of PAH and suggest. Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of inflammation in PAH.

Metallothioneins (MT) are a family of metal ion binding proteins that target nitric oxide, causing zinc release and modulating vascular resistance (39). Our microarray analysis shows that several metallothionein genes are up-regulated in SSc-PAH and IPAH lungs (supplemental table 2). Since metallothioneins are known to regulate hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction of pulmonary artery (40), increased MT expression in SSc-PAH and IPAH may be related to abnormal vascular responses that contribute to the development of pulmonary hypertension.

Gene expression profiles of primary fibroblasts from PAH tissues also revealed abnormal fibroblast functions that may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Although the relevance of lung fibroblasts in IPAH is not intuitive, our data show IPAH fibroblasts were highly enriched for genes involved in IL-17 signaling with a more pronounced number of IL-17 pathway genes in IPAH fibroblasts versus IPAH lungs. To date, the contribution of IL-17–mediated mechanisms to the pathogenesis of IPAH remains unexplored. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the study of fibroblasts allows for the identification of cell-specific mechanisms of disease that would be otherwise missed in the study of whole lung tissues.

In summary, we performed molecular profiling of lung tissues from individuals with SSc and compared the gene expression patterns to those from idiopathic PF or PAH and normal lungs. A similar analysis was done on primary fibroblasts cultured from the same tissues. Our identification of unique expression patterns provides additional insights to the pathogenesis of SSc-related lung disease and new directions for research in this fatal complication. One potential limitation of our study is that explanted lung tissues may represent end-stage disease. However, lung biopsy of patients with SSc is not routinely obtained, and lung tissues from early lung disease remain limited. Our study is unique not only in utilizing a relatively large sample size of SSc lung tissues, but also in that we distinguish PF and PAH in these tissues, and provide a unique analysis of whole lung and matching primary fibroblasts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Pittsburgh Genomics and Proteomics Core Laboratories and Ms. Debby Hollingshead for assistance with the microarray analysis. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 AR050840, P30 AR058910, P30 DK072506, the Simmons Fund for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, and the Scleroderma Foundation (New Investigator grant to E.H). This publication was made possible in part by Grant Number 5 UL1 RR024153 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp

References

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schurawitzki H, Stiglbauer R, Graninger W, Herold C, Polzleitner D, Burghuber OC, et al. Interstitial lung disease in progressive systemic sclerosis: high-resolution CT versus radiography. Radiology. 1990;176(3):755–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.176.3.2389033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh ET, Lee P, Gladman DD, Abu-Shakra M. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis: an analysis of 17 patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(10):989–93. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.10.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Au K, Khanna D, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Tashkin DP. Current concepts in disease-modifying therapy for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: lessons from clinical trials. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11(2):111–9. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathai SC, Hassoun PM. Therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(6):642–8. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283307dc8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitfield ML, Finlay DR, Murray JI, Troyanskaya OG, Chi JT, Pergamenschikov A, et al. Systemic and cell type-specific gene expression patterns in scleroderma skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(21):12319–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635114100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner H, Shearstone JR, Bandaru R, Crowell T, Lynes M, Trojanowska M, et al. Gene profiling of scleroderma skin reveals robust signatures of disease that are imperfectly reflected in the transcript profiles of explanted fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1961–73. doi: 10.1002/art.21894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milano A, Pendergrass SA, Sargent JL, George LK, McCalmont TH, Connolly MK, et al. Molecular subsets in the gene expression signatures of scleroderma skin. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feghali CA, Wright TM. Identification of multiple, differentially expressed messenger RNAs in dermal fibroblasts from patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(7):1451–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1451::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou X, Tan FK, Xiong M, Arnett FC, Feghali-Bostwick CA. Monozygotic twins clinically discordant for scleroderma show concordance for fibroblast gene expression profiles. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3305–14. doi: 10.1002/art.21355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luzina IG, Atamas SP, Wise R, Wigley FM, Xiao HQ, White B. Gene expression in bronchoalveolar lavage cells from scleroderma patients. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26(5):549–57. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuo F, Kaminski N, Eugui E, Allard J, Yakhini Z, Ben-Dor A, et al. Gene expression analysis reveals matrilysin as a key regulator of pulmonary fibrosis in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6292–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092134099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang IV, Burch LH, Steele MP, Savov JD, Hollingsworth JW, McElvania-Tekippe E, et al. Gene expression profiling of familial and sporadic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(1):45–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-062OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bridges RS, Kass D, Loh K, Glackin C, Borczuk AC, Greenberg S. Gene expression profiling of pulmonary fibrosis identifies Twist1 as an antiapoptotic molecular “rectifier” of growth factor signaling. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(6):2351–61. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geraci MW, Moore M, Gesell T, Yeager ME, Alger L, Golpon H, et al. Gene expression patterns in the lungs of patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: a gene microarray analysis. Circ Res. 2001;88(6):555–62. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bull TM, Coldren CD, Moore M, Sotto-Santiago SM, Pham DV, Nana-Sinkam SP, et al. Gene microarray analysis of peripheral blood cells in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):911–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1686OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grigoryev DN, Mathai SC, Fisher MR, Girgis RE, Zaiman AL, Housten-Harris T, et al. Identification of candidate genes in scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Transl Res. 2008;151(4):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(5):581–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(2):216–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilewski JM, Liu L, Henry AC, Knauer AV, Feghali-Bostwick CA. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 3 and 5 are overexpressed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and contribute to extracellular matrix deposition. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(2):399–407. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62263-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan R, Patel S, Hu H, Lyons-Weiler J. Efficiency analysis of competing tests for finding differentially expressed genes in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Inform. 2008;6:389–421. doi: 10.4137/cin.s791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel S, Lyons-Weiler J. caGEDA: a web application for the integrated analysis of global gene expression patterns in cancer. Appl Bioinformatics. 2004;3(1):49–62. doi: 10.2165/00822942-200403010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1453–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview--extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3246–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B, Schmoyer D, Kirov S, Snoddy J. GOTree Machine (GOTM): a web-based platform for interpreting sets of interesting genes using Gene Ontology hierarchies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu-Hirota R, Sasamura H, Kuroda M, Kobayashi E, Saruta T. Functional characterization of podocan, a member of a new class in the small leucine-rich repeat protein family. FEBS Lett. 2004;563(1–3):69–74. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasuoka H, Jukic DM, Zhou Z, Choi AM, Feghali-Bostwick CA. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 induces skin fibrosis: A novel murine model for dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):3001–10. doi: 10.1002/art.22084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fertig N, Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, Kuwana M, Lucas M, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Anti-U11/U12 RNP antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a new serologic marker associated with pulmonary fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(7):958–65. doi: 10.1002/art.24586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(9):5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouros D, Wells AU, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Polychronopoulos V, Pantelidis P, et al. Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(12):1581–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer A, Swigris JJ, Groshong SD, Cool CD, Sahin H, Lynch DA, et al. Clinically significant interstitial lung disease in limited scleroderma: histopathology, clinical features, and survival. Chest. 2008;134(3):601–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allison DB, Cui X, Page GP, Sabripour M. Microarray data analysis: from disarray to consolidation and consensus. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(1):55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrg1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renzoni EA, Abraham DJ, Howat S, Shi-Wen X, Sestini P, Bou-Gharios G, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals novel TGFbeta targets in adult lung fibroblasts. Respir Res. 2004;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wixler V, Hirner S, Muller JM, Gullotti L, Will C, Kirfel J, et al. Deficiency in the LIM-only protein Fhl2 impairs skin wound healing. J Cell Biol. 2007;177(1):163–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding L, Wang Z, Yan J, Yang X, Liu A, Qiu W, et al. Human four-and-a-half LIM family members suppress tumor cell growth through a TGF-beta-like signaling pathway. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(2):349–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI35930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amaar YG, Thompson GR, Linkhart TA, Chen ST, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP-5) interacts with a four and a half LIM protein 2 (FHL2) J Biol Chem. 2002;277(14):12053–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110872200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chilosi M, Poletti V, Zamo A, Lestani M, Montagna L, Piccoli P, et al. Aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(5):1495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XM, Zhang Y, Kim HP, Zhou Z, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Liu F, et al. Caveolin-1: a critical regulator of lung fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2006;203(13):2895–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.St Croix CM, Wasserloos KJ, Dineley KE, Reynolds IJ, Levitan ES, Pitt BR. Nitric oxide-induced changes in intracellular zinc homeostasis are mediated by metallothionein/thionein. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282(2):L185–92. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernal PJ, Leelavanichkul K, Bauer E, Cao R, Wilson A, Wasserloos KJ, et al. Nitric-oxide-mediated zinc release contributes to hypoxic regulation of pulmonary vascular tone. Circ Res. 2008;102(12):1575–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.