Abstract

Maple syrup is made by boiling the sap collected from certain maple (Acer) species. During this process, phytochemicals naturally present in tree sap are concentrated in maple syrup. We previously reported 23 phytochemicals from a butanol extract of Canadian maple syrup (MS-BuOH). Here we report the isolation and identification of 30 additional compounds (1–30) from its ethyl acetate extract (MS-EtOAc) not previously reported from MS-BuOH. Of these, 4 compounds are new (1–3, 18) and 20 compounds (4–7, 10–12, 14–17, 19–20, 22–24, 26, 28–30) are being reported from maple syrup for the first time. The new compounds include 3 lignans and 1 phenylpropanoid: 5-(3″,4″-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-3-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxybenzyl)-4-hydroxymethyl-dihydrofuran-2-one (1), (erythro, erythro)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (2), (erythro, threo)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (3) and 2,3-dihydroxy-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone (18), respectively. In addition, 25 other phenolic compounds were isolated including (threo, erythro)-1-[4-[(2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (4), (threo, threo)-1-[4-[(2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (5), threo-guaiacylglycerol-β-O-4′-dihydroconiferyl alcohol (6), erythro-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-[4-(3-hydroxypropyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy]-1,3-propanediol (7), 2-[4-[2,3-dihydro-3-(hydroxymethyl)-5-(3-hydroxypropyl)-7-methoxy-2-benzofuranyl]-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy]-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanediol (8), acernikol (9), leptolepisol D (10), buddlenol E (11), (1S,2R)-2-[2,6-dimethoxy-4-[(1S,3aR,4S,6aR)-tetrahydro-4-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-1H,3H-furo[3,4-c]furan-1-yl]phenoxy]-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanediol (12), syringaresinol (13), isolariciresinol (14), icariside E4 (15), sakuraresinol (16), 1,2-diguaiacyl-1,3-propanediol (17), 2,3-dihydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-1-propanone (19), 3-hydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-1-one (20), dihydroconiferyl alcohol (21), 4-acetylcatechol (22), 3′,4′,5′-trihydroxyacetophenone (23), 3,4-dihydroxy-2-methylbenzaldehyde (24), protocatechuic acid (25), 4-(dimethoxymethyl)-pyrocatechol (26), tyrosol (27), isofraxidin (28) and 4-hydroxycatechol (29). One sesquiterpene, phaseic acid (30), which is a known metabolite of the phytohormone, abscisic acid, was also isolated from MS-EtOAc. The antioxidant activities of MS-EtOAc (IC50 = 75.5 μg/mL), and the pure isolates (IC50 ca. 68–3000 μM) were comparable to vitamin C (IC50 = 40 μM) and the synthetic commercial antioxidant, butylated hydroxytoluene (IC50 = 3000 μM), in the diphenylpicrylhydrazyl radical scavenging assay. The current study advances scientific knowledge of maple syrup constituents and suggest that these diverse phytochemicals may impart potential health benefits to this natural sweetener.

Keywords: maple syrup, phenylpropanoids, lignans, sesquiterpene, phenolics, antioxidant

INTRODUCTION

Maple syrup is a premium natural sweetener obtained by concentrating the sap collected from certain maple (genus, Acer) species, primarily the sugar (A. saccharum Marsh.) and red (A. rubrum L.) maples. Both of these maple species are native to North America and thus, the northeastern region of North America, primarily the province of Quebec in Canada, leads the worldwide production of maple syrup (1, 2).

The maple trees are tapped in the late winter to early spring months when freeze/thaw cycles of cold night and warm days facilitate abundant flow of tree sap (1). The sap is collected and boiled to concentrate the sugar producing a 66° Brix maple syrup. Apart from sucrose which is its major sugar, the natural sap contains minerals, oligosaccharides, amino acids, organic acids, and phenolic compounds (1, 2). Because of the worldwide popularity, consumption, and economical importance of maple syrup, identification of its phytochemical constituents is of great scientific interest (3). This is relevant from a human health perspective given that plant derived compounds, such as phenolics, have attracted immense attention for their biological effects and potential human health benefits.

Our laboratory recently embarked on a research program to investigate the chemical and biological properties of maple syrup from Canada. To that end, we recently identified several phenolic compounds, for the first time, from its butanol extract (MS-BuOH) (4, 5). While our overall aim was to increase scientific knowledge of maple syrup constituents, we did not examine its ethyl acetate extract (MS-EtOAc) primarily because it had already been studied by other groups (6, 7). However, since our published studies (4, 5), we have been intrigued by striking differences in biological activities between MS-BuOH and MS-EtOAc (8, and other unpublished observations) prompting us to initiate the current study.

The main objective of the current study was to comprehensively isolate and identify compounds present in MS-EtOAc which would complement previous studies from our laboratory and others (4, 5, and references cited therein) to give an overall picture of the chemical constituents present in maple syrup. Here we report the isolation and identification of 30 compounds from MS-EtOAc not previously reported from MS-BuOH (4, 5). In addition, the antioxidant activities of MS-EtOAc and the pure isolates were evaluated in the diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay and these activities are also reported here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Experimental Procedures

All 1D proton and carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H and 13C-NMR) and 2D NMR experiments, 1H-1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY), HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence), HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Coherence), and NOE (Nuclear Overhauser Effect), were acquired either on a Bruker 400 MHz or on a Varian 500 MHz instrument. Unless otherwise stated, deuterated methanol (CD3OD) was used as solvent. High resolution electrospray ionization mass spectral (HRESIMS) data were acquired on a Q-Star Elite (Applied Biosystems MDS) mass spectrometer equipped with a Turbo Ionspray source and was obtained by direct infusion of the pure compounds. Analytical and semi-preparative high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) were performed on a Hitachi Elite LaChrom system consisting of a L2130 pump, L-2200 autosampler, and a L-2455 Diode Array Detector all operated by EZChrom Elite software. Medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) was carried out on prepacked C18 columns connected to a DLC-10/11 isocratic liquid chromatography pump (D-Star Instruments, Manassas, VA) with a fixed-wavelength detector. Optical rotation was performed on an Auto Pol III Automatic Polarimeter (Rudolph Research, Flanders, NJ, USA) with samples dissolved in methanol at 22 °C using a 1 dm pathway cell.

Chemicals and Reagents

All solvents were of ACS or HPLC grade and were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich through Wilkem Scientific (Pawcatuck, RI). Sephadex LH-20, ascorbic acid, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), and diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) reagent were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Extraction and Isolation of Maple Syrup Ethyl Acetate (MS-EtOAc) Compounds

Maple syrup (grade C, 20 L) was provided by the Federation of Maple Syrup Producers of Quebec (Canada) as previously reported (4). The maple syrup was shipped and kept frozen in our lab upon delivery. The maple syrup was subjected to liquid-liquid partitioning with ethyl acetate (10 L × 3) to yield a dried ethyl acetate extract (MS-EtOAc; 4.7 g) after solvent removal in vacuo. The MS-EtOAc (4.5 g) was initially purified on a Sephadex LH-20 column (4 × 65 cm) with a gradient system of MeOH/H2O (3:7 to 1:0, v/v) to afford seven fractions, A1-A7. Fraction A1 (2.08 g) was then chromatographed on a C18 MPLC column (4 × 37 cm) eluting with a gradient system of MeOH/H2O (3:7 to 1:0, v/v) to afford sixteen subfractions, B1-B16. These sub-fractions were individually subjected to a series of semi-preparative HPLC separations using a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (250 × 10 mm i.d., 5 μm, flow = 2 mL/min) with different isocratic elution systems of MeOH/H2O to afford compounds 2 (0.9 mg), 3 (2.5 mg), 4 (0.8 mg), 5 (0.5 mg), 6 (17.5 mg), 7 (0.7 mg), 8 (1.1 mg), 9 (3.9 mg), 10 (1.1 mg), 11 (2.1 mg), 12 (2.8 mg), 13 (3.2 mg), 15 (2.4 mg), 16 (5.2 mg), 17 (0.8 mg), and 30 (0.5 mg). Similarly, fraction A3 (0.71 g) was purified by semi-preparative HPLC using a Waters XBridge Prep C18 column (250 × 19 mm i.d., 5 μm; flow = 3.5 mL/min) and a gradient solvent system of MeOH/H2O to afford four subfractions C1-C4. These subfractions were separately subjected to semi-preparative HPLC with isocratic solvents systems of MeOH/H2O to afford compounds 1 (2.2 mg), 14 (4.5 mg), 19 (4.5 mg), 20 (2.2 mg), 21 (4.2 mg), 27 (3.7 mg), and 28 (1.1 mg). Similarly, fraction A4 (0.097 g) was purified by semi-preparative HPLC to afford compounds 18 (1.4 mg), 22 (2.6 mg), 23 (8.0 mg), 24 (0.4 mg), and 26 (3.2 mg) and subfraction A5 (0.022 g) yielded compounds 25 (3.6 mg) and 29 (1.1 mg).

Structural Elucidation of MS-EtOAc Compounds

All of the isolated compounds were identified by examination of their 1H and/or 13C NMR and mass spectral data, and by comparison of these to published literature reports, when available. Table 1 shows the literature references for the known compounds for which previously published NMR data are available and thus these spectral data are not provided here. However, the NMR data for the four new compounds (i.e. 1, 2, 3 and 18), and six of the known compounds (i.e. 8, 10, 21, 23, 24, and 26) which are not available in the literature, are reported here for the first time as follows:

Table 1.

Total Compounds isolated from an Ethyl Acetate Extract of Canadian Maple Syrup (MS-EtOAc)

| compd | identification | references of NMR data |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5-(3″,4″-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-3-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxybenzyl)-4-hydroxymethyl-dihydrofuran-2-one* | - |

| 2 | (erythro, erythro)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol* | - |

| 3 | (erythro, threo)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol* | - |

| 4 | (threo, erythro)-1-[4-[(2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriola | 9 |

| 5 | (threo, threo)-1-[4-[(2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriola | 9 |

| 6 | threo-guaiacylglycerol-β-O-4′-dihydroconiferyl alcohol | 10 |

| 7 | erythro-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-[4-(3-hydroxypropyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy]-1,3-propanediola | 11 |

| 8 | 2-[4-[2,3-dihydro-3-(hydroxymethyl)-5-(3-hydroxypropyl)-7-methoxy-2-benzofuranyl]-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy]-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanediol b | - |

| 9 | acernikol | 12 |

| 10 | leptolepisol D a,b | - |

| 11 | buddlenol E a | 13 |

| 12 | (1S, 2R)-2-[2,6-dimethoxy-4-[(1S,3aR,4S,6aR)-tetrahydro-4-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-1H,3H-furo[3,4-c]furan-1-yl]phenoxy]-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanediola | 14 |

| 13 | syringaresinol | 15 |

| 14 | isolariciresinola | 16 |

| 15 | icariside E4a | 17 |

| 16 | sakuraresinola | 18 |

| 17 | 1,2-diguaiacyl-1,3-propanediola | 19 |

| 18 | 2,3-dihydroxy-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone* | - |

| 19 | 2,3-dihydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-1-propanone a | 20 |

| 20 | 3-Hydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-1-onea | 21 |

| 21 | dihydroconiferyl alcoholb | - |

| 22 | 4-acetylcatechola | 22 |

| 23 | 3′,4′,5′-trihydroxyacetophenone a,b | - |

| 24 | 3,4-dihydroxy-2-methylbenzaldehydea,b | - |

| 25 | protocatechuic acid | 23 |

| 26 | 4-(dimethoxymethyl)-pyrocatechola,b | - |

| 27 | tyrosol | 24 |

| 28 | isofraxidina | 25 |

| 29 | 4-hydroxycatechola | 26 |

| 30 | phaseic acida | 27 |

First report from maple syrup

NMR data provided for the first time herein

New compounds

5-(3″, 4″-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-3-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxybenzyl)-4-hydroxymethyl-dihydrofuran-2-one (1)

colorless amorphous powder; [α]D25 +17° (c 1.5 mg/mL, MeOH); (+) HRESIMS, m/z 427.1239 [M + Na]+, calcd. for C21H24O8Na 427.1369; the 1H and 13C-NMR data are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

1H-NMR [δ, (multiplicity, JHH in Hz)] Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 1–3 and 18

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 18a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 6.88 (s) | 6.99 (s) | 6.91 (s) | 7.45 (s) |

| 5 | 6.74 (brs) | 6.74 (d, overlapped) | 6.64 (d, 8.5) | 7.47 (d, 8.0) |

| 6 | 6.74 (brs) | 6.77 (d, overlapped) | 6.77 (d, 8.5) | 6.85 (d, 8.0) |

| 7a | 3.01 (dd, 13.0, 1.5) | 4.91 (d, 4.5) | 4.89 (d, 7.0) | - |

| 7b | 3.38 (d, 12.5) | - | - | |

| 8 | - | 4.21 (m) | 3.92 (m) | 5.09 (brs) |

| 9a | - | 3.90 (m) | 3.30 (m) | 3.88 (d, 8.8) |

| 9b | - | 3.50 (m) | 3.66 (dd, 12.0, 4.0) | 3.73 (m) |

| 2′ | 6.23 (brs) | 6.75 (s) | 6.66 (s) | - |

| 5′ | 6.82 (dd, 8.0, 1.5) | - | - | - |

| 6′ | 6.68 (d, 8.0) | 6.75 (s) | 6.66 (s) | - |

| 7′ | 5.08 (dd, 9.5, 1.5) | 4.60 (d, 5.5) | 4.51 (d, 5.5) | - |

| 8′ | 2.5 (m) | 3.68 (m) | 3.68 (m) | - |

| 9a′ | 3.92 (m) | 3.5 (m) | 3.58 (m) | - |

| 9b′ | 3.61 (m) | 3.4 (m) | 3.45 (dd, 12.0, 4.0) | |

| 3-OCH3 | 3.84 (s) | 3.82 (s) | 3.73 (s) | - |

| 3′-OCH3 | 3.60 (s) | 3.82 (s) | 3.77 (s) | - |

| 4′-OCH3 | 3.82 (s) | - | - | - |

| 5′-OCH3 | - | 3.82 (s) | 3.77 (s) | - |

NMR data for all compounds acquired at 500 MHZ except 18 which was acquired at 400 MHz

Table 3.

13C-NMR (δ values) Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 1–3 and 18

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3a | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 126.94 | 132.40 | 133.53 | 122.08 |

| 2 | 113.92 | 110.00 | 111.82 | 114.91 |

| 3 | 147.47 | 147.28 | 148.88 | 145.27 |

| 4 | 145.31 | 145.41 | 147.50 | 151.29 |

| 5 | 114.84 | 114.30 | 115.98 | 114.48 |

| 6 | 123.27 | 119.15 | 121.04 | 122.08 |

| 7 | 41.17 | 72.57 | 74.71 | 198.08 |

| 8 | 78.16 | 86.09 | 89.28 | 74.00 |

| 9 | 178.28 | 60.08 | 61.83 | 64.85 |

| 1′ | 130.93 | 138.50 | 140.20 | - |

| 2′ | 108.45 | 103.80 | 105.20 | - |

| 3′ | 149.36 | 152.89 | 154.15 | - |

| 4′ | 149.55 | 134.50 | 136.50 | - |

| 5′ | 110.82 | 152.89 | 154.15 | - |

| 6′ | 119.80 | 103.80 | 105.20 | - |

| 7′ | 81.46 | 73.74 | 75.22 | - |

| 8′ | 49.88 | 75.90 | 77.45 | - |

| 9′ | 57.19 | 63.00 | 64.33 | - |

| 3-OCH3 | 54.92 | 55.20 | 56.44 | - |

| 3′-OCH3 | 54.87 | 54.94 | 56.73 | - |

| 4′-OCH3 | 55.00 | - | - | - |

| 5′-OCH3 | - | 54.94 | 56.73 | - |

NMR data for all compounds acquired at 125 MHz except 3 which was acquired at 100 MHz

(erythro, erythro)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl) ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (2)

colorless amorphous powder; [α]D25 0° (c 0.3 mg/mL, MeOH); (+) HRESIMS, m/z 463.1138 [M + Na]+, calcd. for C21H28O10Na 463.1580; the 1H and 13C NMR data are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

(erythro, threo)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (3)

colorless amorphous powder; [α]D25 +6° (c 2.0 mg/mL, MeOH); (+) HRESIMS, m/z 463.1693 [M + Na]+, calcd. for molecular formula C21H28O10Na 463.1580; the 1H and 13C NMR data are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

2-[4-[2,3-dihydro-3-(hydroxymethyl)-5-(3-hydroxypropyl)-7-methoxy-2-benzofuranyl]-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy]-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanediol (8)

yellowish amorphous powder; (+) HRESIMS, m/z 609.1852 [M + Na]+, calcd. for molecular formula C31H38O11; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 7.00 (1H, s, H-2), 6.86 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5), 6.74 (4H, s, H-2′, 6′, 2″, 6″), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-7′), 4.99 (1H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-7), 4.07 (1H, m, H-8), 3.89 (3H, s, 3″-OCH3), 3.84 (9H, s, 3, 3′, 5′-OCH3), 3.80 (2H, m, H-9″), 3.58 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, H-9′), 3.48 (1H, m, H-8′), 2.64 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, H-7″), 1.83 (2H, m, H-8″); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ 154.47 (C-3′, 5′), 149.00 (C-3), 147.51 (C-4″), 147.22 (C-4), 145.51 (C-3″), 139.99 (C-1′), 137.51 (C-1″), 137.00 (C-4′), 135.53 (C-1), 129.63 (C-5″), 120.95 (C-6), 118.06 (C-6″), 115.92 (C-5), 114.20 (C-2″), 111.71 (C-2), 103.88 (C-2′, 6′), 89.06 (C-8), 88.65 (C-7′), 88.65 (C-7′), 74.60 (C-7), 65.14 (C-9′), 62.31 (C-9″), 61.85 (C-9), 56.74 (3′, 3, 5′, 7′-OCH3), 56.41 (3″-OCH3), 55.95 (C-8′), 36.97 (C-8″), 33.03 (C-7″).

Leptolepisol D (10)

yellowish amorphous powder; (+) HRESIMS, m/z 539.1623 [M + Na]+, calcd. for molecular formula C27H32O10; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 7.02 (1H, s, H-2), 6.82 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), 6.81 (1H, s, H-2′), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6′), 6.68 (1H, s, H-2″), 6.64 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5′, 5″), 6.57 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6″), 4.93 (1H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, H-7′), 4.80 (1H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, H-7), 4.30 (1H, m, H-8), 3.86 (1H, m, H-9′a), 3.84 (1H, m, H-9a), 3.82, 3.75, 3.66 (9H, s, 3, 3′, 5′-OCH3), 3.76 (1H, m, H-9b), 3.70 (1H, m, H-9′a), 2.89 (1H, m, H-8′); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 149.89 (C-3′), 147.29 (C-3), 146.94 (C-3″), 146.64 (C-4′), 145.56 (C-4), 144.80 (C-4″), 137.95 (C-1′), 132.78 (C-1), 130.58 (C-1″), 121.79 (C-6″), 119.46 (C-6), 118.78 (C-2′), 116.90 (C-5), 114.25 (C-5′), 114.22 (C-2″), 113.15 (C-5′), 110.98 (C-6′), 110.40 (C-2), 84.86 (C-8), 73.72 (C-7), 72.62 (C-7′), 62.97 (C-9′), 60.72 (C-9), 55.22 (C-8′), 54.94, 54.93, 54.90 (3, 3′, 5′-OCH3).

2,3-dihydroxy-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone (18)

yellowish amorphous powder; [α]D25 +267° (c 0.15 mg/ml, MeOH); (−) HRESIMS, m/z 197.0423 [M - H]−, calcd. for molecular formula C9H9O5 197.0450; the 1H and 13C NMR data are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Dihydroconiferyl alcohol (21)

white amorphous powder; (+) HRESIMS, m/z 183.1470 [M + H]+, calcd. for molecular formula C10H15O3; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.76 (1H, s, H-2), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), 6.61 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5), 3.82 (3H, s, 3-OCH3), 3.58 (2H, t, J = 5.0 Hz, H-9), 2.51 (2H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, H-7), 1.78 (2H, m, H-8); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 147.41 (C-3), 144.20 (C-4), 133.53 (C-1), 120.36 (C-6), 114.78 (C-5), 111.74 (C-2), 60.83 (C-9), 34.31 (C-8), 31.24 (C-7).

3′, 4′, 5′-trihydroxyacetophenone (23)

pale yellow amorphous powder; (−) HRESIMS, m/z 167.0409 [M - H]−, calcd. for molecular formula C8H7O4; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 7.09 (2H, s, H-2, 6), 2.53 (3H, s, CH3).

3, 4-dihydroxy-2-methylbenzaldehyde (24)

pale yellow amorphous powder; (−)HRESIMS, m/z 151.0444 [M - H]−, calcd. for molecular formula C8H7O3; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 9.96 (1H, s, CHO), 7.27 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5), 2.53 (3H, s, CH3).

4-(dimethoxymethyl)-pyrocatechol (26)

white amorphous powder; (+) HRESIMS, m/z 183.0999 [M - H]−, calcd. for molecular formula C9H11O4; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) δ 6.84 (1H, s, H-2), 6.75 (2H, s, H-5, 6), 5.23 (1H, s, H-7), 3.30 (6H, s, OCH3); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) δ 146.81 (C-3), 146.26 (C-4), 131.22 (C-1), 119.57 (C-6), 115.92 (C-5), 114.93 (C-2), 104.95 (C-7), 50.00 (OCH3).

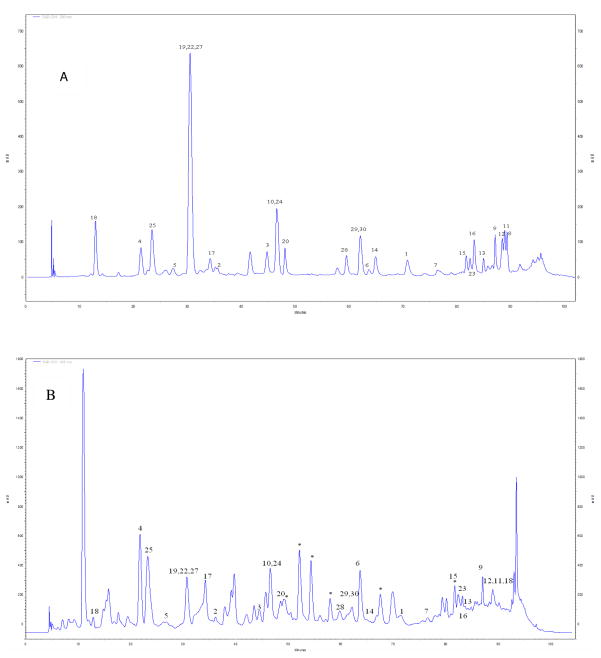

Analytical HPLC-UV

All analyses were conducted on a Luna C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μM; Phenomenex) with a flow rate at 0.75 mL/min and injection volume of 20 μL. A gradient solvent system consisting of solvent A (0.1 % aqueous trifluoroacetic acid) and solvent B (methanol) was used as follows: 0–10 min, from 10 to 15 % B; 10–20 min, 15 % B; 20–40 min, from 15 to 30 % B; 40–55 min, from 30 to 35 % B; 55–65 min, 35 % B; 65–85 min, from 35 to 60 % B; 85–90 min, from 60 to 100 % B; 90–93 min, 100 % B; 93–94 min, from 100 to 10 % B; 94–104 min, 10 % B. Figure 2 shows the HPLC-UV chromatograms of all of the isolated compounds (combined into one single injection; 2A) and the total MS-EtOAc extract (50 mg/mL in DMSO; 2B). Unfortunately, due to limited sample quantity, we were not able to include pure compounds 21 and 26 in the HPLC-UV injection shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

HPLC-UV chromatogram (at 280 nm) of (A) 30 compounds isolated and identified from an ethyl acetate extract of Canadian maple syrup (MS-EtOAc) combined in a single injection and, (B) the whole MS-EtOAc extract. Compounds 21 and 26 were excluded because of limited sample quantity.*overlapping compounds also present in a butanol extract of Canadian Maple syrup (MS-BuOH) as previously reported (4).

Antioxidant Assay

The antioxidant potential of the Canadian maple syrup ethyl acetate extract (MS-EtOAc) and the pure compounds were determined on the basis of the ability to scavenge the DPPH radical as previously reported (4). The DPPH radical scavenging activity of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and the synthetic commercial antioxidant, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) were also assayed as positive controls (see Table 4). The assay was conducted in a 96-well format using serial dilutions of 100 μL aliquots of test compounds (ranging from 2500 to 26 μg/mL), ascorbic acid (1000–10.4 μg/mL), and BHT (250,000–250 μg/mL). After this, DPPH (150 μL) was added to each well to give a final DPPH concentration of 137 μM. Absorbance was determined after 30 min at 515 nm, and the scavenging capacity (SC) was calculated as SC%=[(A0-A1/A0)] × 100, where A0 is the absorbance of the reagent blank and A1 is the absorbance of the test samples. The control contained all reagents except the compounds, and all tests were performed in triplicate. IC50 values denote the concentration of sample required to scavenge 50 % DPPH free radicals.

Table 4.

Antioxidant Activities of Pure Compounds Isolated from an Ethyl Acetate Extract of Canadian Maple Syrup Showing 50% Inhibitory Concentrations (IC50) in the Diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Assay.a

| No. | IC50 (μM) | No. | IC50(μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 946.37 ± 58.5 | 18 | 111.78 ± 5.1 |

| 2 | 1540.91 ± 0.5 | 19a | 258.40 ± 33.8 |

| 3 | 925 ± 179.0 | 20 | 321.53 ± 31.9 |

| 7 | 740.20 ± 3.4 | 22 | 138.16 ± 28.2 |

| 8 | 655.29 ± 14.4 | 23 | 10125 ± 1668.0 |

| 9 | 478.95 ± 42.1 | 24 | 254.17 ± 32.5 |

| 10 | 578.49 ± 1.3 | 25 | 97.83 ± 24.0 |

| 11 | 422.94 ± 2.4 | 27 | 163.93 ± 15.2 |

| 12 | 207.93 ± 41.3 | 28 | 813.81 ± 37.7 |

| 13 | 68.90 ± 5.7 | 29 | 139.42 ± 13.3 |

| 14 | 694.44 ± 110.2 | 30b | 903.57 |

| 15 | 1810.28 ± 265.6 | Ascorbic acid | 40.23 ± 13.4 |

| 16 | 2876.44 ± 44.0 | BHT | 3000.98 ± 1122.2 |

| 17 | 703.12 ± 141.4 |

values are mean ± Standard deviation.

Only tested once because of the limited sample quantity. BHT, a synthetic commercial antioxidant, butylated hydroxytoluene.

Because of limited sample quantity all compounds were evaluated except 4, 5, 6, 21 and 26.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural Elucidation of Compounds from MS-EtOAc

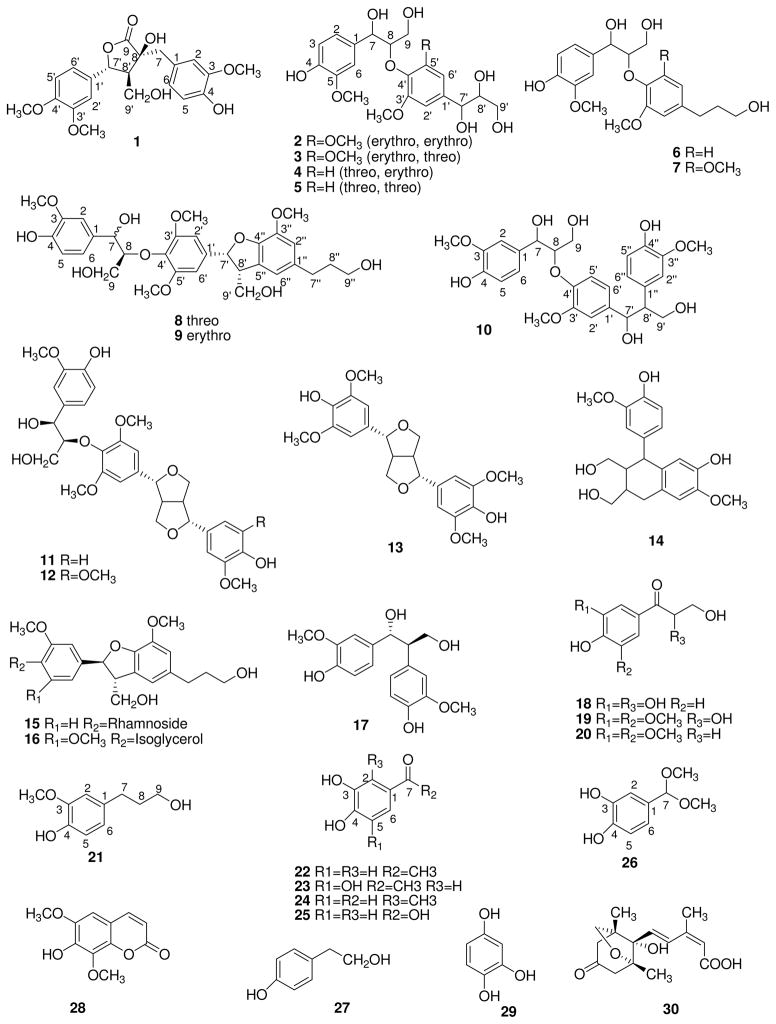

In the current study, 30 compounds were isolated and identified from an ethyl acetate extract of Canadian maple syrup (MS-EtOAc) that have not been previously reported from its butanol extract (MS-BuOH) (4, 5). The structures of the compounds (Figure 1) were derived through detailed NMR and mass spectral analyses and by comparison of these to literature data when available (see Table 1). Figure 2A shows the HPLC-UV profile of the 30 compounds isolated from MS-EtOAc, all combined into a single injection, and Fig. 2B shows the chromatogram of the total MS-EtOAc extract.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds (1–30) isolated and identified from an ethyl acetate extract of Canadian maple syrup (MS-EtOAc).

Four of the isolates are new compounds and thus detailed structural elucidations of these molecules are being reported here for the first time. These are for 3 new lignans (compounds 1–3) and a new phenylpropanoid (compound 18) and are described below.

Elucidation of Compound 1

Compound 1 was identified as the lignan, 5-(3″,4″-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-3-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxybenzyl)-4-hydroxymethyl-dihydrofuran-2-one (1). The 1H and 13C NMR data (Tables 2 and 3, respectively) of compound 1 revealed that it was the aglycon of the known lignan, 3-[4-[(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)oxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]methyl]-5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)dihydro-3-hydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)-2(3H)-furanone previously isolated by our laboratory from MS-BuOH extract (4). The gross structure of 1 was elucidated by comparison of its NMR data to that of its previously reported rhamnosidic form and its structure was confirmed by detailed 2D-NMR analysis (see Online Supporting Information, Figures S3–S6) and examination of its HRESIMS data: m/z 427.1239 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C21H24O8Na 427.1369). The rhamnosidic derivative of compound 1 has also been isolated from the hardwood of sugar maple and the relative stereochemistry of that compound was established therein (28). Thus, while we did not determine the absolute stereochemistry of compound 1, we were able to deduce its relative configuration based on comparison of our NOE analyses to that published for its rhamnosidic derivative (28). The NOEs between H-7′/H9′a, H-7′/H-9′b, H-8′/H-2, H-6, H-2′, and H-6′ indicated the β-orientations of OH-8 and H-5, and the α-orientation of H-8′. Three methoxyl groups located on two 1,3,4-trisubstituted aromatic rings could also be confirmed at the C-3, C-3′, and C-4′ positions from the NOEs between H-2/OMe (δ 3.84), H-2′/OMe (δ 3.60), and H-5′/OMe (δ 3.82), respectively. Thus, from the above findings, the structure of 1 was deduced as shown in Figure 1.

Elucidation of Compound 2

Compound 2 was identified as the lignan, (erythro, erythro)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (2). The positive HRESIMS data exhibited a molecular peak at m/z 463.1138 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C21H28O10Na 463.1580). The 1H NMR data of 2 (Table 2) indicated the presence of a 1, 3, 4, 5-tetrasubstituted benzene ring [6.75 (2H, s, H-2′, 6′)], a 1, 3, 4-trisubstituted benzene moiety [δH: 6.99 (1H, s H-2), 6.74 (1H, d, overlapping, H-5), 6.77 (1H, d, overlapping, H-6)], three methoxyl groups [δH 3.82 (3,3′, 5′-OCH3)], four oxymethines and two oxymethylenes which were all confirmed by the 13C NMR data (Table 3). The 1H-1H COSY suggested two partial structures, [-CH(OH)CH(O)CH2OH] and [-CH(OH)CH(OH)CH2OH]. In the HMBC spectrum (see Online Supporting Information, Fig. S12), the correlations from δH 4.91 (1H, d, J = 4.5 Hz, H-7) to C-1 (δ 132.40), C-2 (δ 110.0) and C-6 (δ 119.15), from δH 4.60 (1H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, H-7′) to C-1′ (δ 138.50) and C-2′, C-6′ (δ 103.80 equivalent) indicated the presence of one guaiacylglycerol moiety and one syringylglycerol moiety, respectively. Since the C-8 in compound 2 was downfield compared to its C-8′ (δ 86.09 and δ 75.9, respectively), this suggested that the connection of C-8 was to C-4′. This was confirmed by comparison of the 13C-NMR data with the known compound 4 which contains one less methoxyl group than compound 2. Therefore, the gross structure of compound 2 was elucidated as 1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol. It has been previously reported that for syringoylglycerols and guaiacylglycerol derivatives, the coupling constant (J value) between H-7 and H-8 is ≤ 5 Hz for the erythro isomer and ≥ 7 Hz for the threo isomer (29). Thus, the lower coupling constant between H-7 (J = 4.5 Hz) and H-7′ (J = 5.5 Hz) of compound 2 suggested that it is the erythro, erythro isomer.

Elucidation of Compound 3

Compound 3 was identified as the lignan, (erythro, threo)-1-[4-[2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (3). The positive HRESIMS exhibited a molecular peak at m/z 463.1138 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for molecular formula C21H28O10Na 463.1580). The 1H and 13C NMR data of this compound closely resembled that of compound 2 (shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Comparison of the 1H-NMR spectrum of these two compounds showed that the coupling constant of H-7 (δ 4.89, d, J = 7.0 Hz) of compound 3 is greater than that of compound 2 (δ 4.89, d, J = 4.5 Hz). From the HPLC-UV analysis (Fig. 2A), it was also evident that compounds 2 and 3 had different retention times under the same chromatographic methods.

It should be noted that the two new lignans isolated in this study, namely, compounds 2 and 3, can be regarded as methoxylated derivatives of the known lignans, (threo, erythro)-1-[4-[(2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (4), and (threo, threo)-1-[4-[(2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,2,3-propanetriol (5), respectively, but with different stereochemistry. While the known lignans 4 and 5 have been previously reported from Zantedeschia aethiopica (9), this is the first report of all four of these compounds in maple syrup (see Table 1). Interestingly, these four lignans elute with distinct retention times under our HPLC conditions (shown in Fig. 2A) which would be useful for future quantification of these compounds in different grades of maple syrup and its products.

Elucidation of Compound 18

Compound 18 was identified as the phenlypropanoid, 2,3-dihydroxy-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone (18). The 1H-NMR data of 18 (see Table 2) indicated the presence of a 1,3,4-trisubstituted benzene moiety [δH: 7.47 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H-5), 7.45 (1H, s H-2), 6.85 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H-6)] and a –CH(OH)-CH2OH moiety [5.09 (1H, brs, H-8), 3.88 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-9a) and 3.73 (1H, m, H-9b)] which was supported by the 13C NMR data (Table 3). According to the NMR data, on comparison with compound 20, 3-hydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-1-one, previously isolated from Ficus beecheyana (20), the H-8 in compound 18 was shifted downfield from δH 3.20 to 5.09. This indicated that compound 18 was a hydroxyl derivative of compound 20 which was confirmed by the HRESIMS data of m/z 197.0423 suggesting a molecular formula of C9H9O5. It should be noted that the absolute stereochemistry of compound 18 (viz. chiral center at position 8,) was not determined in this study due to limited sample quantity. Thus, further studies would be required to confirm the absolute sterochemistry of compound 18

Other Compounds

Apart from the 4 new compounds described above, an additional 26 other compounds were also isolated from MS-EtOAc that have not been previously reported from MS-BuOH (4, 5). The structures of these compounds were elucidated based on detailed NMR and mass spectral data and by comparison with literature data when available (see Table 1). Since the NMR spectral data for compounds 8, 10, 21, 23, 24, and 26 are not available in the literature, they are being reported here for the first time (provided in the Methods section).

Based on their chemical structures, the 30 isolates from MS-EtOAc can be classified into various phytochemical sub-classes including lignans (1–16), phenylpropanoids (17–21), coumarins (28), simple phenolics (22–26, 27, 29), and a sesquiterpene (30). Among these classes, lignans and phenylpropanoids were the main types of compounds found in MS-EtOAc which is consistent with our earlier findings of MS-BuOH constituents (4).

It should be noted that this is the first report of 23 of these phenolic compounds, namely, compounds 1–7, 10–12, 14–20, 22–24, 26, 28–29, in maple syrup. However, while phenolic compounds are common to maple syrup, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first published report of a sesquiterpene, namely phaseic acid (30), therein. Phaseic acid is a known oxidative metabolite of the plant hormone, abscisic acid, which has previously been reported from the natural maple sap (30), and also from Canadian maple syrup (personal communication, Professor Yves Desjardins, Laval University, Québec, Canada). The occurrence of an ABA metabolite in maple syrup is interesting considering that this phytohormone has attracted significant research attention for its efficacy in the treatment of diabetes and inflammation (31, 32).

Based on the chromatogram shown in Fig. 2B, it was apparent that there were several other peaks at 280 nm characteristic of phenolic compounds in the maple syrup extract. Here it should be noted that apart from the 30 compounds isolated from MS-EtOAc in this study, we also isolated seven additional compounds that were previously obtained from MS-BuOH (see Fig. 2B with the marked overlapping peaks). These compounds included erythro-guaiacylglycerol-β-O-4′-dihydroconiferyl alcohol, lyoniresinol, secoisolariciresinol, C-veratroylglycol, scopoletin, vanillin and syringic acid (4). Also, while not isolated from MS-EtOAc, based on HPLC-UV comparisons with compounds isolated from MS-BuOH (4), we were able to identify three additional compounds: syringaldehyde, syringenin and (E)-coniferol in MS-EtOAc (data not shown). Thus, apart from the 30 compounds described from MS-EtOAc in this study, an additional 10 compounds previously isolated from MS-BuOH (4), are also present therein as overlapping compounds (Fig. 2B). Moreover, it should be noted that similar to previous observations (4–7), a number of compounds in maple syrup remain un-identified due to low yields and/or degradation of compounds during extraction and isolation procedures.

ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY

We have previously reported that phenolic compounds identified from MS-BuOH show antioxidant activity in the DDPH free radical scavenging assay (4). Therefore, MS-EtOAc and the pure isolates, along with vitamin C and the synthetic commercial antioxidant, BHT, were evaluated for antioxidant potential in the DPPH assay (Table 4). Consistent with our previous report (4), vitamin C and BHT showed IC50 values of 40 μM (ca. 7.08 μg/mL) and 3000 μM (ca. 660 μg/mL), respectively, and the antioxidant activity of the MS-EtOAc (IC50 = 77.5 μg/mL) and several of the pure isolates were comparable to vitamin C and superior to BHT.

In summary, 30 compounds were isolated from MS-EtOAc that have not been previously reported from MS-BuOH (4, 5). Among these, four of the isolates are new compounds and 24 others are being reported from maple syrup for the first time. In addition, MS-EtOAc contains 10 additional/overlapping compounds that are also present in MS-BuOH. The results reported here advances current knowledge of maple syrup constituents and confirm that this plant derived natural sweetener contains a wide diversity of phytochemicals, among which phenolic compounds predominate. Thus, the biological properties of these maple syrup constituents may impart potential health benefits to this natural sweetener but further in vivo research using animal models and human subjects would be needed to confirm this.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Conseil pour le développement de l’agriculture du Québec (CDAQ), with funding provided by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Advancing Canadian Agriculture and Agri-Food (ACAAF) program. The Federation of Quebec Maple Syrup Producers participated in the financing, collection and donation of maple syrup samples from Quebec, Canada. Mass spectral data were acquired from an instrument located in the RI-INBRE core facility located at the University of Rhode Island (Kingston, RI, USA) obtained from Grant # P20RR016457 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Perkins TD, van den Berg AK. Maple syrup-production, composition, chemistry, and sensory characteristics. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2009;56:101–143. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(08)00604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball DW. The chemical composition of maple syrup. J Chem Ed. 2007;84:1647–1650. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter TL, Fagerson IS. Phenolic compounds in maple sap. In: Ho CT, Lee CY, Huang MT, editors. Phenolic compounds and their effects on health; ACS Symposium Series; Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1992. p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L, Seeram NP. Maple syrup phytochemicals include lignans, coumarins, a stilbene and other previously unreported antioxidant phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:11673–11679. doi: 10.1021/jf1033398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li L, Seeram NP. Quebecol, a novel phenolic isolated from Canadian maple syrup. J Fun Foods. 2011;3:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kermasha S, Goetghebeur M, Dumont J. Determination of phenolic compound profiles in maple products by high performance liquid chromatography. J Agric Food Chem. 1995;43:708–716. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abou-Zaid MM, Nozzolillo C, Tonon A, Coppens M, Lombardo ADA. High performance liquid chromatography characterization and identification of antioxidant polyphenols in maple syrup. Pharm Biol. 2008;46:117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apostolidis E, Li L, Lee C, Seeram NP. In vitro evaluation of phenolic-enriched maple syrup extracts for inhibition of carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes relevant to type 2 diabetes management. J Fun Foods. 2011;3:100–106. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Della-Grace M, Ferrara M, Fiorentino A, Monaco P, Previtera L. Antialgal compounds from Zantedeschia aethiopica. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:1299–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, Wong M, Wang N, Chan S, Yao X. Lignans from the stems of Sambucus williamsii and their effects on osteoblastic UMR106 cells. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2007;9:583–591. doi: 10.1080/10286020500530433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jutiviboonsuk A, Zhang H, Tan G, Ma C, Van H, Manh C, Bunyapraphatsara N, Soejarto D, Fong H. Bioactive constituents from roots of Bursera tonkinensis. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2745–2751. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morikawa T, Tao J, Ueda K, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M. Medicinal foodstuffs. XXXI. Structures of new aromatic constituents and inhibitors of degranulation in RBL-2H3 cells from a Japanese folk medicine, the stem bark of Acer nikoense. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51:62–67. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houghton P. Lignans and neolignans from Buddleja davidii. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:819–826. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiorentino A, DellaGreca M, D’Abrosca B, Oriano P, Golino A, Izzo A, Zarrelli A, Monaco P. Lignans, neolignans and sesquilignans from Cestrum parqui l’Her. Biochem Syst Eco. 2007;35:392–396. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai X, Lee I, Dat N, Shen G, Kang J, Kim D, Kim Y. Inhibitory lignans against NFAT transcription factor from Acanthopanax koreanum. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:738–741. doi: 10.1007/BF02980142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erdemoglu N, Sener B, Ozcan Y, Ide S. Structural and spectroscopic characteristics of two new dibenzylbutane type lignans from Taxus baccata L. J Mol Struct. 2003;655:459–466. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakanishi T, Iida N, Inatomi Y, Murata H, Inada A, Murata J, Lang F, Iinuma M, Tanaka T. Neolignan and flavonoid glycosides in Juniperus communis vardepressa. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshinari K, Shimazaki N, Sashida Y, Mimaki Y. Flavanone xyloside and lignans from Prunus jamasakura bark. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:1675–1678. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshikawa K, Mimura N, Arihara S. Isolation and absolute structures of enantiomeric 1, 2-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1, 3-propanediol 1-O-glucosides from the bark of Hovenia trichocarpa. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:1137–1139. doi: 10.1021/np980003d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee T, Kuo Y, Wang G, Kuo Y, Chang C, Lu C, Lee C. Five new phenolics from the roots of Ficus beecheyana. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:1497–1500. doi: 10.1021/np020154n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones L, Bartholomew B, Latif Z, Sarker SD, Nash RJ. Constituents of Cassia laevigata. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:580–583. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao Z, Shi D, Li H, Zhang L, Xu C, Zhu H. Polyphenols based on isoflavones as inhibitors of Helicobacter pylori urease. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;V15:3703–3710. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Nagatsu A, Okuyama H, Mizukami H, Sakakibara J. Sesquiterpene glycosides from cotton oil cake. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:665–668. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takaya Y, Furukawa T, Miura S, Akutagawa T, Hotta Y, Ishikawa N, Niwa M. Antioxidant constituents in distillation residue of Awamori spirits. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:75–79. doi: 10.1021/jf062029d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okuyama E, Hasegawa T, Matsushita T, Fujimoto H, Ishibashi M, Yamazaki M. Analgesic components of Saposhnikovia root (Saposhnikovia divaricata) Chem Pharm Bull. 2001;49:154–160. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiramoto K, Li X, Makimoto M, Kato T, Kikugawa K. Identification of hydroxyhydroquinone in coffee as a generator of reactive oxygen species that break DNA single strands. Mutat Res Gene Toxicol Envir Mutagen. 1998;419:43–51. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(98)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirai N, Kondo S, Ohigashi H. Deuterium-labeled phaseic acid and dihydrophaseic acids for internal standards. Bios Biotechnol and Biochem. 2003;67:2408–2415. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshikawa K, Kawahara Y, Arihara S, Hashimoto T. Aromatic compounds and their antioxidant activity from Acer saccaharum. J Nat Med. 2010;65:191–193. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuima K, Otsuka H, Ogimi C, Hirata E, Takushi A, Takeda Y. Sesquiterpene glycosides and sesquilignan glycosides from stems of Alangium premnifolium. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:669–676. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davison RM, Young H. Abscisic-acid content of xylem sap. Planta (Berl) 1973;109:95–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00385455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guri AJ, Hontecillas R, Si H, Liu D, Bassaganya-Riera J. Dietary abscisic acid ameliorates glucose tolerance and obesity-related inflammation in db/db mice fed high-fat diets. Clin Nutr. 2007;1:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bassaganya-Riera J, Guri AJ, Lu P, Climent M, Carbo A, Sobral BW, Horne WT, Lewis SN, Bevan DR, Hontecillas R. Abscisic acid regulates inflammation via ligand-binding domain-independent activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2504–2516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.