Abstract

Tandemly arranged paralogous genes lbe and lbl are members of the Drosophila NK homeobox family. We analyzed population samples of Drosophila melanogaster from Africa, Europe, North and South America, and single strains of D. sechellia, D. simulans, and D. yakuba within two linked regions encompassing partial sequences of lbe and lbl. The evolution of lbe and lbl is highly constrained due to their important regulatory functions. Despite this, a variety of forces have shaped the patterns of variation in lb genes: recombination, intragenic gene conversion and natural selection strongly influence background variation created by linkage disequilibrium and dimorphic haplotype structure. The two genes exhibited similar levels of nucleotide diversity and positive selection was detected in the noncoding regions of both genes. However, synonymous variability was significantly higher for lbe: no nonsynonymous changes were observed in this gene. We argue that balancing selection impacts some synonymous sites of the lbe gene. Stability of mRNA secondary structure was significantly different between the lbe (but not lbl) haplotype groups and may represent a driving force of balancing selection in epistatically interacting synonymous sites. Balancing selection on synonymous sites may be the first, or one of a few such observations, in Drosophila. In contrast, recurrent positive selection on lbl at the protein level influenced evolution at three codon sites. Transcription factor binding-site profiles were different for lbe and lbl, suggesting that their developmental functions are not redundant. Combined with our previous results on nucleotide variation in esterase and other homeobox genes, these results suggest that interplay of balancing and directional selection may be a general feature of molecular evolution in Drosophila and other eukaryote genomes.

Introduction

Genetic changes in the genes that encode transcription factor (TF) proteins can produce fundamental phenotypic differences between species [for review, see 1–4]. Moreover, changes in TF coding sequences can result in profound modifications of the body plan [5], [6]. In order to understand how complex phenotypes evolve, we need to understand how genes involved in transcriptional regulation evolve. A global genomic approach has revealed general trends in gene evolution and showed that positive Darwinian selection is an important factor driving molecular evolution [e.g., 7–9). An important limitation of large-scale genomic studies is that they were unable to identify small-scale, within-gene variation that may directly influence protein function and corresponding phenotypic characteristics. Also, whole genome approaches are unable to reveal population level variation necessary for a better understanding of TF sequence evolution. Quantification of segregating variation within populations at TF loci is necessary to infer selective pressures and to ascertain the functional effects of naturally occurring allelic variation and sequence divergence among orthologs.

The available data on between-species TF variation indicate high rates of sequence evolution among regulatory genes [e.g., 10,11]. Studies of intra-specific nucleotide variation in Drosophila have revealed that regulatory genes tend to be less polymorphic than structural genes [12]. In contrast, homeobox genes from the 93DE cluster of D. melanogaster exhibit high sequence variation in bagpipe (but not in adjacent tinman) genes [13]. Also the TFs involved in olfactory pathways in Caenorhabditis exhibited more between- and within-species variation than structural chemosensory genes [14]. These data indicate that even adjacent regulatory genes can differ greatly in the level and pattern of sequence variation. This suggests that different members of a regulatory gene cluster may be subject to distinct evolutionary forces [15].

Here we focus on two homeobox genes, ladybird early (lbe) and ladybird late (lbl), tandemly-arranged paralogs in Drosophila. We analyze the level and pattern of the lbe and lbl segregating nucleotide variation in natural populations and divergence between close Drosophila species in attempt to reveal evolutionary forces governing the evolution of these genes. Both lbe and lbl genes are members of the NK homeobox gene family that consists of closely linked interacting regulatory genes (in 5′ to 3′ order: tinman (tin), bagpipe (bap), lbe, lbl, C15, and slouch (S59)), located on the right arm of D. melanogaster chromosome 3 at cytological map position 93DE [16], [17]. The coding region of lbe is 4,124 bp long and consists of two exons (1,008 and 432 bp) and one intron (2,684 bp). The lbe gene encodes a protein of 479 amino acids: the lbe homeodomain is located within exon II. The lbl coding region is 23,419 bp long and consists of three exons (702, 180, and 237 bp) and two introns (22,012 and 571 bp). The lbl gene is alternatively spliced, with three different LBL protein isoforms deduced from the sequence of cDNA clones [18], consisting of 342, 372, and 411 amino acids. The first part of the lbl homeodomain is in exon II and the rest in exon III, with a 571-bp intron that interrupts the lbl homeodomain. The transcription start site of lbl is 8.0 kb downstream of the lbe terminal stop codon. No ORF has been recorded in the region between the two genes and both genes are transcribed from the same DNA strand. The two genes show high similarity in the regions extending downstream and immediately upstream from the homeodomain [18], [19]. The deduced LBE and LBL amino acid sequences are 97% identical in the homeodomain, 61–81% identical in the upstream conserved region and 77% identical downstream of the homeodomain [17].

The lbe and lbl genes encode transcription regulators, which play an important role in neurogenesis, myogenesis, and cardiogenesis [17], [18], [20]. These genes have almost identical expression patterns, although lbe, located at the 5′ end, is activated slightly earlier than lbl; another difference concerns the trunk epidermis, where lbe transcripts are much more abundant [18]. Based upon their similar amino acid composition and expression patterns, both genes are often jointly referred to as “ladybird (lb)” [17], [20]. Analyses of lb gain-of-function phenotypes and rescue experiments have led to the conclusion that lbe and lbl are functionally redundant [17], [18]. In addition to Drosophila, lb-like genes have been detected in the sponge Sycon raphanus [21] and the mollusk Loligo opalescens [22], and orthologous genes have been found in mouse, chicken, and human genomes [23]–[25]. It is currently thought that the ladybird genes have an evolutionarily conserved role in development.

We previously investigated nucleotide variability in the tin and bap homeobox genes, located on the right arm of chromosome 3 of D. melanogaster within the 93DE cluster [13]. We now analyze nucleotide variation in lbe and lbl homeobox genes in 70 strains of D. melanogaster in four populations from East Africa (Zimbabwe), Europe (Spain), North (California) and South (Venezuela) America. We sequenced 4,482 bp covering the homologous coding (including the homeodomain) and noncoding (intron and 3′-flanking) regions for both genes (2,044 bp for lbe and 2,438 bp for lbl). The lbe and lbl genes display distinctive transcription factor binding-site profiles, suggesting that they are not redundant in developmental function. Negative selection and demography are major factors shaping the pattern of nucleotide polymorphism in the two genes. However there are clear indications of positive selection in the coding and noncoding regions of both genes, as well as balancing selection at synonymous sites in the lbe gene.

Results

Nucleotide Polymorphism

We detected similar total nucleotide diversity for lbe and lbl (Tables 1 and 2) close to the levels observed for tin and bap from the same 93DE gene cluster [13]. These estimates were within the range found in highly recombining gene regions of D. melanogaster [12] and in other regulatory genes [e.g., 15]. Figures S1 and S2 show the polymorphisms observed in 70 lines of lbe and lbl, including length polymorphisms. No nonsynonymous variability was detected in the lbe gene, but three nonsynonymous polymorphic sites were found in lbl (exon III, Fig. S2). While silent nucleotide diversity for lbe and lbl was similar (Tables 1 and 2), the level of synonymous polymorphism was 4.9 times higher in lbe than lbl (P<0.001). Synonymous variability of lbe was 4.4 times higher than noncoding variation (Table 1), a difference statistically significant in simulations even without recombination (P = 0.01), but the observed difference was not significant for lbl. There were five polymorphic sites within the lbe homeodomain (positions 1045, 1055, 1058, 1088, and 1121, Fig. S1), with π = 0.0086, slightly higher than for the whole lbe coding region (π = 0.0057). In contrast, there were two polymorphic sites in the lbl homeodomain (exon II, positions 837 and 903, Fig. S2), with π = 0.0013.

Table 1. Nucleotide diversity and divergence in the lbe gene region of D. melanogaster.

| lbe exon II | Full sequence | |||||||

| Intron I | Syn | Nsyn | Total | 3′-fl. region | Ncod | Silent | All sites | |

| N | 948 | 100 | 329 | 429 | 568 | 1516 | 1616 | 1945 |

| S | 21 (7) | 8 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (0) | 23 (5) | 44 (12) | 52 (12) | 52 (12) |

| π | 0.0035 | 0.0244 | 0 | 0.0057 | 0.0090 | 0.0055 | 0.0067 | 0.0056 |

| θ | 0.0046 | 0.0166 | 0 | 0.0039 | 0.0084 | 0.0060 | 0.0068 | 0.0056 |

| Kmel-sim | 0.0257 | 0.1425 | 0 | 0.0309 | 0.0632 | 0.0393 | 0.0454 | 0.0374 |

| Kmel-sec | 0.0330 | 0.1425 | 0 | 0.0309 | 0.0705 | 0.0469 | 0.0526 | 0.0433 |

| Kmel-yak | 0.0792 | 0.1791 | 0 | 0.0382 | 0.1333 | 0.0986 | 0.1035 | 0.0845 |

Note. — Calculations based on 70 D. melanogaster lines from three populations: Barcelona, El Rio (California) and Venezuela, plus three lines from Zimbabwe and one lbe sequence from GenBank (accession number NT_033777.2). N, number of sites (indels excluded); S, polymorphic sites (number of singletons in parentheses); π, average number of nucleotide differences per site among all pairs of sequences [104, p. 256]; θ, average number of segregating nucleotide sites among all sequences, based on the expected distribution of neutral variants in a panmictic population at equilibrium [105]; Kmel-sim, Kmel-sec, and Kmel-yak refer to nucleotide differences between D. melanogaster and D. simulans, D. sechellia or D. yakuba, respectively; Syn, synonymous sites; Nsyn, nonsynonymous sites; Ncod, noncoding (intronic and flanking regions); Silent, silent sites (synonymous and noncoding sites).

Table 2. Nucleotide diversity and divergence in the lbl gene region of D. melanogaster.

| lbl exon II + exon III | Full sequence | ||||||||

| Intron I | Syn | Nsyn | Total | Intron II | 3′-fl. region | Ncod | Silent | All sites | |

| N | 725 | 94 | 311 | 405 | 264 | 643 | 1632 | 1726 | 2037 |

| S | 16 (3) | 3 (1) | 3 (0) | 6 (1) | 24 (6) | 25 (11) | 65 (20) | 68 (21) | 71 (21) |

| π | 0.0053 | 0.0049 | 0.0025 | 0.0031 | 0.0220 | 0.0069 | 0.0086 | 0.0084 | 0.0075 |

| θ | 0.0046 | 0.0066 | 0.0020 | 0.0031 | 0.0189 | 0.0081 | 0.0083 | 0.0082 | 0.0072 |

| Kmel-sim | 0.0357 | 0.0585 | 0.0099 | 0.0209 | 0.1200 | 0.0674 | 0.0599 | 0.0598 | 0.0517 |

| Kmel-sec | 0.0299 | 0.0760 | 0.0112 | 0.0257 | 0.1223 | 0.0781 | 0.0623 | 0.0631 | 0.0547 |

| Kmel-yak | 0.0736 | 0.1496 | 0.0140 | 0.0452 | 0.2772 | 0.1885 | 0.1411 | 0.1416 | 0.1186 |

See Table 1, Note.

Synonymous variation of lbe was higher than in Est-6 and ψEst-6 (for the same population samples), which were among the most polymorphic genes in D. melanogaster [26], [27]. High synonymous variability within lbe exon II was associated with the highest level of pair-wise divergence between D. melanogaster and three other Drosophila species (Table 1), which was several times higher than the divergence of the noncoding region (0.143–0.179 vs. 0.039–0.099). Functional significance could account for the fixation of favored codons, increasing the synonymous divergence in lbe exon II. The high variability of lbe exon II cannot be accounted for by relaxation of functional constraints, since it contains a functionally important homeodomain (180 bp at position 999–1178, our coordinates), which is conserved within a wide phylogenetic scale [17].

Variability of lbl exon III (π = 0.0045) was 3.5 times higher than exon II (π = 0.0013); a significant difference (P<0.01) in coalescent simulations. Increased total variability within lbl exon III was accompanied by decreased silent divergence between D. melanogaster and D. simulans, which was 4.3 times lower in exon III than in exon II (0.0237 vs. 0.1020). Relaxation of functional constraints is one possible explanation for the prevalence of replacement substitutions in lbl exon III. However, these patterns indicated that the lbl coding region was under strong negative selection (see below), possibly imposed by alternative splicing [28] described for this gene [17]. Elevated replacement substitutions may indicate a functional shift of the lbl coding region evolving under positive selection. Below, we used neutrality tests and codon models to test this hypothesis. There was also a significant difference in population variability between lbl introns, 4.2 times higher in intron II than in intron I (π = 0.0220 vs. 0.0053, Table 2). A parallel difference in species divergence was observed between these two introns (see Kmel-sim and Kmel-sec in Table 2). The elevated divergence in the lbl intron II is puzzling. The region is rich with transcription factor binding sites (see below the section “Binding Site Profile”) and its complex architecture might be related to the specific evolutionary dynamic of intron enhancers that can evolve beyond recognizable sequence similarity while retaining function [e.g., 29]. For more details concerning nucleotide polymorphism, see Text S1 and Tables S1, S2, S3.

Recombination and Gene Conversion

The method of Hudson and Kaplan [30] revealed a minimum of 10 recombination events for lbe, 14 for lbl, and one between them. Estimates of the recombination rate ρ and the ρ/θ ratio were higher for lbl than for lbe (ρ = 0.016 and 0.006, respectively; Table S4). Previously we found a large difference (∼33 times) in recombination rate between tin (ρ = 0.001) and bap (ρ = 0.026), within the 93DE cluster [13]. For esterase genes on the left arm of D. melanogaster chromosome 3 at cytological map position 68F7-F8, the rate was nearly three times higher for Est-6 than for ψEst-6 (0.021 vs. 0.008) [26], [27]. This suggests that noticeably different recombination rates are common in tandemly associated paralogs. The recombination rate was similar for European and North American samples, but much lower for South America (Table S4). A similar trend was observed for Est-6 and ψEst-6 [26], [27].

Sawyer's method [31] detected gene conversion events within lbe (except Venezuela) and lbl, but the number of significant events was considerably higher for lbl (Table S5). The average fragment length was 1,202 bp for lbe but 703 bp for lbl. Previously, we observed similar differences in average fragment length for tin (1,396 bp) and bap (665 bp) [13]. There was no evidence of intergenic gene conversion, likely due to low nucleotide similarity between lbe and lbl (53.5%), insufficient for efficient intergenic conversion.

Haplotype Structure

The lbe haplotype structure (excluding recombinants, see Fig. S1) is shown in Fig. 1, left. Due to recombination and gene conversion, this tree is not good reflection of the genealogical process, but serves to show the genetic structure of the data. There were two main lbe haplotype groups (1 and 2 in Fig. 1) and two sub-groups (1a and 2a). The main haplotype groups exhibited 19 nucleotide differences: 14 fixed within noncoding regions and five almost fixed within coding regions (excepting two recombinant variants detected for Ven-S-21F and Zim-S-44F; Fig. S1). The groups were differentially associated with indels. Group 2 was completely associated with three deletions (1-, 4-, and 30-bp, within intron I and the 3′-flanking region; ▴1, ▴4, and ▴6, Fig. S1). Group 1 was associated with two polymorphic indels (22-bp insertion and 8-bp deletion within the 3′-flanking region; ▾1 and ▴7; Fig. S1). These five indels were not found in the lbe sequences of D. simulans and D. sechellia, suggesting that they may represent a derived condition after the split of D. melanogaster from the other two species. The difference between the two lbe haplotype groups was highly significant (Fst = 0.84; K st = 0.75; P<0.001).

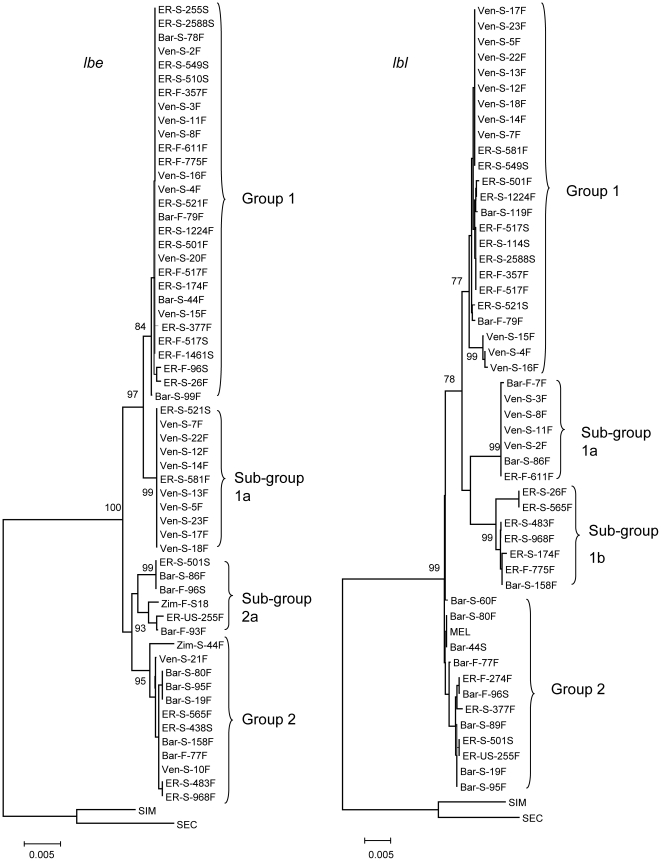

Figure 1. Neighbor-joining tree of lbe (left) and lbl (right) haplotypes of D. melanogaster, excluding recombinant sequences.

The tree is based on Kimura 2-parameter distance. Numbers at the nodes are bootstrap percent support values based on 10,000 replications. Strains as in Fig. S1. Haplotype groups are encompassed in brackets. SEC, D. sechellia; SIM, D. simulans.

There were two lbe haplotype sub-groups (1a and 2a); related respectively to group 1 and to group 2 (Fig. 1, left). Sub-group 1a had seven nearly fixed differences from group 1 (excepting one recombinant variant, ER-S-26F), all within noncoding regions (Fig. S1). The coding regions were identical for all lbe group 1. Sub-group 2a differed from group 2 by nine fixed nucleotide differences (excepting one recombinant variant, Zim-S-44F), all within the 3′-flanking region. There were six polymorphic sites within the coding region with different frequencies for group 2 and sub-group 2a; however, none of these differences were fixed. Sub-group 2a was associated with two indels (2-bp deletion and 10-bp insertion within the 3′-flanking region; ▴8 and ▾2; Fig. S1).

Strong haplotype structure was also observed for lbl, with two main haplotype groups (1 and 2), and two sub-groups, 1a and 1b (Fig. 1, right). The lbl haplotype groups were differentially associated with indels: sub-group 1a was fully associated with a 12-bp insertion and a 26-bp deletion within intron II (▾2 and ▴2, Fig. S2); sub-group 1b was associated with a 9-bp deletion within exon III (▴6); group 2 was associated with two deletions (78- and 237-bp long) and a 24-bp insertion (▴1, ▾3, and ▴3); there were no indels within group 1. The difference between the lbl haplotype groups was highly significant (Fst = 0.86; K st = 0.54; P<0.001). Total sequence divergence (D xy) among the lbl haplotype lineages was 0.0106 (ignoring indels), similar to lbe (0.0081).

Group 1 lbe haplotypes were most frequent in our data set, but variability was low (π, total = 0.0002), 5.5 times lower than in group 2. Group 2 haplotypes were less frequent and more variable (π, total = 0.0011). Group 2 is likely the ancestral state, consistent with the higher polymorphism of group 2 haplotypes, and supported by the comparison with D. simulans and D. sechellia. Group 1 may have evolved under directional selection (high frequency and low variability haplotype profile). For the North American sample (excluding recombinants), there were 37 polymorphic sites, and there was a subset of 17 sequences (haplotype group 1) with only four polymorphic sites (Fig. S1). The haplotype test [32] was significant (P = 0.02) with recombination rate ρ = 0.015. For the South American sample, the test was also significant (P<0.01), as it was significant for the total dataset, contrasting group 1 with all available sequences (P = 0.02). The haplotype test was not significant for the full length of the lbl gene region, which could be explained by elevated number of polymorphic sites within intron I and 3′-flanking region (Fig. S2). However the test was significant (P = 0.025) for the lbl region including exon II, intron II, and exon III for the total dataset. Thus, the main haplotype group 1 might evolve under the influence of directional selection in both the lbe and lbl genes. For more details concerning haplotype structure, see Text S2.

Sliding Window Analysis

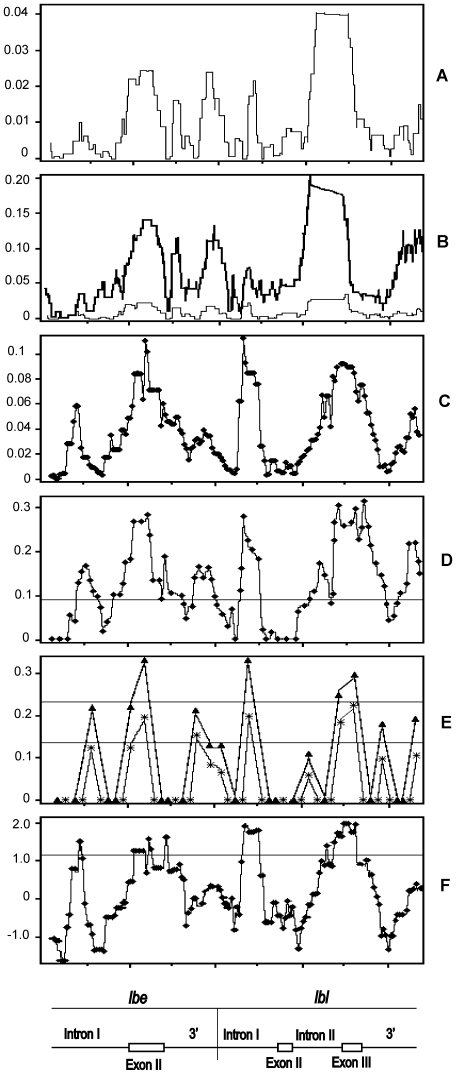

There were noticeable peaks of nucleotide variability along the lbe and lbl genes (Fig. 2). For lbe, bursts of variability were observed for intron I, exon II, and the 3′-flanking region with the most pronounced peak of silent polymorphism in exon II (midpoint coordinates 1073–1254; Fig. 2A). For lbl, there were three significant peaks within noncoding regions with the most pronounced peak observed for intron II, 3 – 4 times more polymorphic than other noncoding regions of lbl. The coding region of lbl also showed a significant peak of nucleotide variability in exon III accompanied by decrease of divergence that strongly contrasted with the high divergence in the adjacent regions (Fig. 2B). Peaks of nucleotide diversity were accompanied by increased levels of linkage disequilibrium (Fig. 2C) and significant values of Kelly's [33], Wall's [34], and Tajima's [35] neutrality test statistics (Fig. 2D, E, and F), suggesting that positive (balancing or diversifying) selection may overcome the dominant effect of negative selection in this highly constrained functional region.

Figure 2. Sliding window plots along the lbe and lbl genes of D. melanogaster.

A, silent nucleotide diversity; B, silent nucleotide diversity (thin line) and divergence (thick line); C, linkage disequilibrium measured by D; D, E, and F, neutrality test statistics of Kelly's ZnS [33], Wall's B and Q [34], and Tajima's D [35], respectively. Window sizes are 100 nucleotides with one-nucleotide increments for A and B; 250 nucleotides with 25-nucleotide increments for C; 250 nucleotides with 30-nucleotide increments for D and F; and 250 nucleotides with 150-nucleotide increments for E. A schematic representation of the region investigated is displayed at bottom. 99% confident intervals for neutrality test statistics (D, E, and F plots) are marked by thin horizontal lines (there are two horizontal lines in E: Top is for the B statistic and bottom is for the Q statistic of Wall's [34] test) obtained by coalescent simulations conditioned on the number of polymorphic sites with the recombination rate equal to 0.015.

Patterns of polymorphism and divergence were different in lbe and lbl. For lbe the highest silent polymorphism and divergence were observed in exon II, but for lbl in a noncoding region, intron II. We suggest that there may be multiple targets of positive selection within the noncoding and coding regions of both genes. Despite the absence of replacement substitutions in lbe, the most pronounced lbe peak of variability was located within exon II, seven and three times more polymorphic than intron I and the 3′-flanking region, respectively. One explanation is that balancing selection acts on synonymous sites of lbe (additional support for this premise below).

Two types of selection might be involved in the evolution of the lb genes: balancing selection that creates elevated nucleotide variation around target polymorphic sites, and directional selection that creates significant excesses of very similar sequences exhibiting very low levels of variation. A similar scenario was inferred to explain patterns of nucleotide polymorphism for Est-6 and bagpipe in D. melanogaster [13], [26], [36].

Tests of Neutrality and Maximum Likelihood Analysis of Selective Pressures

Neutrality tests detected significant deviations from neutrality in the lb region (Table S7), based on linkage disequilibrium (LD) between segregating sites with recombination (ρ = 0.015, see above). When applied to the full ladybird gene region, Kelly's [33] ZnS and Wall's [34] B and Q tests were highly significant for the whole dataset, and for each population separately (Table S7). The tests were also significant separately for the lbe and lbl genes (except the European sample) as well as for the coding and flanking regions of both genes (Table S7). Significant values of Kelly's and Wall's statistics were grouped around the peaks of linkage disequilibrium (Fig. 2), and centered around the coding and noncoding regions of lbe and lbl, which supporting the hypothesis that these sites were targets of balancing selection. For more detailed information concerning LD, see Text S3, Fig. S3, and Table S6.

However, neutrality tests are typically affected by demography and so may be difficult to interpret [37], [38]. We applied model-based maximum likelihood (ML) methods to confirm the observations made above (results summarized in Table 3). All results from the ML analyses revealed below held for the full sample and for the D. melanogaster strains separately, whether or not recombinant sequences were removed.

Table 3. Likelihood ratio tests LRTs based on codon models of evolution.

| LRTs null vs. alternative | Genesa | LRT statisticb | P-valueb | Estimates of interestc |

| M0 vs. M3 | lbe | 0 | 1 | ω = 0, κ = 2.09, t = 0.37, d S = 0.80, d N = 0 |

| lbl | 45.37 | <0.001 | ω = 0.22, κ = 3.72, t = 0.27, d S = 0.22, d N = 0.05 | |

| Est-6 | 164.50 | <0.001 | ω = 0.23, κ = 3.14, t = 0.44, d S = 0.33, d N = 0.08 | |

| ψEst-6 | 184.62 | <0.001 | ω = 0.29, κ = 1.64, t = 0.61, d S = 0.44, d N = 0.13 | |

| bap | 50.43 | <0.001 | ω = 0.10, κ = 4.77, t = 0.22, d S = 0.24, d N = 0.02 | |

| tin | 0 | 1 | ω = 0.13, κ = 3.23, t = 0.12, d S = 0.13, d N = 0.02 | |

| M3* vs. Dual | lbe | 54.64 | <0.001 | CVS = 3.59, CVN = 0 |

| lbl | 19.47 | <0.001 | CVS = 2.27, CVN = 6.00 | |

| Est-6 | 130.38 | <0.001 | CVS = 2.29, CVN = 4.42 | |

| ψEst-6 | 132.06 | <0.001 | CVS = 2.05, CVN = 2.13 | |

| bap | 28.08 | <0.001 | CVS = 2.33, CVN = 5.77 | |

| tin | 1.08 | 0.90 | CVS = 0, CVN = 0 | |

| FMutSel0 vs. FMutSel | lbe | 101.37 | <0.001 | P+ = 0.22, S+ = 0.73, S– = – 3.53 |

| lbl | 75.21 | <0.001 | P+ = 0.04, S+ = 2.27, S– = – 4.60 | |

| Est-6 | 128.93 | <0.001 | P+ = 0.25, S+ = 0.83, S– = –1.47 | |

| ψEst-6 | 109.21 | <0.001 | P+ = 0.31, S+ = 0.64, S– = – 0.96 | |

| M7 vs. M8 | lbl | 21.14 | <0.001 | p = 8.84, q = 99, p 0 = 0.978, ω = 24.52, p 1 = 0.022 |

| Est-6 | 63.15 | <0.001 | p = 0.33, q = 2.24, p 0 = 0.986, ω = 9.20, p 1 = 0.014 | |

| ψEst-6 | 27.21 | <0.001 | p = 0.01, q = 0.03, p 0 = 0.994, ω = 9.05, p 1 = 0.006 | |

| bap | 11.47 | 0.003 | p = 0.01, q = 0.13, p 0 = 0.992, ω = 9.90, p 1 = 0.008 | |

| Selection on noncoding regions ζ = 1 vs. ζ≥1 | lbe | 178.86 | <0.001 | ζ 0 = 0.20, p 0 = 0.95, ζ 1 = 6.55, p 1 = 0.05 |

| lbl | 25.11 | <0.001 | ζ 0 = 0.08, p 0 = 0.86, ζ 1 = 2.81, p 1 = 0.14 |

M3* is the HYPHY implementation of model M3 [98]. Tests comparing M3* vs. Dual and M7 vs. M8 were performed only for genes where M0 vs. M3 was significant. The test FMutSel0 vs. FMutSel was performed only for genes with large samples.

Results for lb genes are shown for full samples. However, all LRT results remain the same when only D. melanogaster was analyzed (with or without the recombinants).

LRT statistic is double the difference between the likelihood values optimized under the alternative and null models: 2(???alt – ???null). P-value is computed using the χ2-distribution with d.f. = 4 for LRTs of M0 vs. M3, and M3* vs. Dual. For LRT of M7 vs. M8 d.f. = 2, and for FMutSel0 vs. FMutSel d.f. = 41. For the LRT of positive selection on noncoding regions d.f. = 1. Significant P-values in bold.

Estimates under M0: ω = d N/d S; tree length t is measured by number of expected nucleotide substitutions per codon over the tree; transition/transversion ratio κ (estimated under M3, or under M0 if the test M0 vs. M3 is not significant); d S, tree length for synonymous substitutions , d N, tree length for nonsynonymous sites. Estimates under Dual model: coefficients of variation ( = standard deviation/mean) for distributions of synonymous and nonsynonymous rates, CVS and CVN respectively. Estimates under mutation-selection model FMutSel: P+ is the proportion of mutations with advantageous effect (S = 2Ns>0); S+ is mean selection coefficient of all advantageous mutations; S– is mean selection coefficient of all deleterious mutations. Estimates under M8: p, q are parameters controlling the shape of the Beta-distribution; p 0 is proportion of sites in the sequence with ω-values from beta-distribution (between 0 and 1); ω = d N/d S, with discrete class allowed to be >1 (under positive selection); p 1 is proportion of sites in the discrete class. In the combined coding and noncoding model [102], sites in the noncoding region come from two categories: proportion p 0 are under negative selection with ζ 0<1, and p 1 are under positive selection or evolving neutrally with ζ 1≥1; ζ 0 and ζ 1 are estimates of the ratio of substitution rate in the noncoding region to average synonymous rate in the coding region for the two categories.

The test for variability of diversifying selection on the protein was not significant for lbe (M0 vs. M3) [39] as stringent purifying selection prohibited nonsynonymous changes. In contrast, this test was highly significant for lbl (Table 3). The test for positive selection (M7 vs. M8, Table 3) was significant for lbl, suggesting that 2% of sites evolved under strong diversifying selection (ω≈24.5), while the remaining sites were very conserved (ω≈0.1). Sites 118Q, 122S and 131L (in bold in Fig. S2) in lbl were subject to positive selection at the protein level (posterior probability >0.99). Lower, but significant, levels of positive selection were detected in other genes (Table 3), with 7, 3, and 1 sites under positive selection, respectively for Est-6, ψEst-6, and bap (posterior probability >0.99), consistent with previous results [13], [40].

The synonymous rate d S in the coding sequence varied significantly for both lbe and lbl (M3 vs. M3-Dual in Table 3). Coefficient of variation (CV) was used to compare the variability of nonsynonymous and synonymous rates estimated under the M3-Dual model. Synonymous variation was higher in lbe with CVS = 3.59, compared to 2.27 in lbl. Interestingly, the synonymous variation in lbl was similar to that in other genes, such as Est-6, ψEst-6 and bap with CVS = 2.29, 2.05, and 2.33, respectively. In these genes, the nonsynonymous rate variation (CVN) was much higher than for the synonymous rate, with CVN 4.4 – 6 and CVS 2 – 2.3. For ψEst-6 and tin the variation in d N and d S was similar. In contrast, synonymous variation was not only higher in lbe comparatively to other genes, but was accompanied by a total absence of nonsynonymous substitutions (CVN = 0). Seven percent of sites in lbe evolved with unusually high d S = 14.3, whereas at the remaining sites the rate was constrained to d S 0.01 – 0.08.

Widespread positive selection in synonymous sites was previously reported for mammalian genes [41] where selection may act through mRNA destabilization affecting mRNA levels and translation [42], [43]. Since protein folding is thought to occur simultaneously with protein translation from mRNA, the use of preferred and unpreferred codons may affect protein translation rates [44]. All polymorphic sites in the lbe coding region (Fig. S1) showed anomalously high rates of synonymous substitutions (posterior probabilities >0.99). These sites may be responding to diversifying selection on synonymous codons, perhaps affecting the speed of translation, with possible implications for protein folding (see below “mRNA Secondary Structure Stability” for details).

Synonymous codon usage is typically high in Drosophila [e.g., 45,46]. In our data, the test comparing selection-mutation models FMutSel0 vs. FMutSel was highly significant for both lb genes and all other members of the 93DE gene cluster (Table 3), suggesting that natural selection was a driving force in the evolution of synonymous codons.

Finally, the LRT for positive selection in noncoding regions (see "Materials and Methods") was significant for both lb genes (Table 3). For lbe, 5% sites in the noncoding region were estimated to evolve by positive selection, with a substitution rate more than six times higher than the average d S in the coding region of lbe (ζ1 = 6.55). For lbl, a larger proportion of sites (14%) was estimated to be under positive selection, although the estimated selection pressure was lower, with ζ1 = 2.81. Such differences in estimated positive selection pressure on noncoding regions are especially striking considering that the average d S is much higher for lbe than for lbl (estimates from M0, Table 3). For more detailed information concerning ML analyses, see Text S4.

mRNA Secondary Structure Stability

We calculated RNA secondary structure free energy for the representative sequences of the main lbe and lbl haplotype groups (Table 4) using the program RNAstructure [47]. The major lbe haplotype groups (I and II, Fig. 1) significantly differed (P = 0.0001) with respect to mRNA secondary structure while the lbe group I haplotypes were less stable than group II. In contrast to lbe, the difference in mRNA stability between lbl haplotypes was small and not statistically significant (P>0.5). Predicted mRNA stability was much higher for lbe than for lbl (Mann-Whitney test P<0.0001) for both haplotype groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Free energy (ΔG, kcal/mol) of lbe and lbl mRNA base pairing.

| Group I (ER-S-2588S) | Group II (ER-S-565F) | ||||

| Mean | St. dev | Mean | St. dev | P | |

| lbe | −144.639 | 1.6323 | −146.734 | 2.0640 | 0.0001 |

| lbl | −90.061 | 2.4110 | −89.676 | 2.3594 | N.S. |

St. dev.: standard deviation.

Thus, lbe haplotypes divergent in only synonymous changes exhibited significant differences in mRNA stability. This observation highlights the potential significance of lbe synonymous variation, providing indirect evidence for the functional basis of balancing selection maintaining synonymous variation in this gene. Given the evidence from other studies that differences in mRNA secondary structure stability can affect mRNA decay [48], gene expression [49], [50], and level of protein translation [51], [52], we propose that lbe synonymous polymorphisms may be important contributors to adaptive variation in D. melanogaster. Because there was no difference in secondary structure stability between lbl mRNA transcripts representing two main haplotype groups, mRNA secondary structure for this gene may not be a target for positive selection. We showed above (section “Tests of Neutrality and Maximum Likelihood Analysis of Selective Pressures”) that for the lbl gene, positive selection operated on the protein level.

Predicted mRNA stability was much higher for lbe than for lbl (Table 4; Mann-Whitney test P<0.0001), consistent with the GC difference between the genes. Total GC content was significantly higher in lbe than lbl (59.5% vs. 51.3%; Wilcoxon test P = 0.0001; Mann-Whitney test P = 0.0001). It was shown previously that increased levels of GC in coding sequences have a stabilizing effect on mRNA secondary structure [e.g., 53]. Accordingly, lbe evolution was associated with increased stability and balancing selection on mRNA secondary structure whereas lbl evolution was accompanied by lower mRNA stability and positive selection at the protein level.

Binding Site Profile

Drosophila transcription factor motifs were obtained from FlyReg database curated motifs [54], and we used ClusterDraw2 [55] to scan for binding site matches and binding site clusters. The program uses a polynomial model to determine statistical significance of binding site clusters. The cluster significance cutoff was set to 3, corresponding to a significance level of P = 0.001. We analyzed 44 transcription factor motifs and detected significant clusters for 30 motifs (Table S8). The spatial distribution of clusters was not uniform along lb genes because the vast majority of significant clusters were located within non-coding sequences. The deviation from equal proportion of significant clusters was highly significant for both lbe (χ2 = 29.13, d.f. = 1, P<0.001) and lbl (χ2 = 32.30, d.f. = 1, P<0.001). Twelve of 30 motifs were significant for both genes. Ten clusters were significant only for lbe (part of a specific component of the lbe regulatory profile). Eight clusters were significant only for lbl (specific component of the lbl regulatory profile). In lbe and lbl, these clusters coincided for 40% of the binding sites, whereas the remaining clusters were gene-specific. The distribution of significant binding-site clusters for lbe and lbl was highly asymmetric, with a proportion of specific clusters >50%. The difference in binding-site profiles suggests that the genes are not redundant in developmental function.

Discussion

Our analyses revealed a dimorphic haplotype structure for both lb genes. Despite similar levels of total nucleotide diversity in lb genes, synonymous nucleotide variability and the variation in the synonymous rate of change were much higher in lbe than in lbl and other genes from the 93DE cluster (tin and bap) as well as Est-6 and ψEst-6 that are among the most polymorphic genes of D. melanogaster [13], [26], [27]. We attribute this high synonymous variation to balancing selection on lbe synonymous sites. Resch et al. [41] showed for mammalian genes that positive selection at synonymous sites may act through mRNA destabilization affecting mRNA levels and translation. This observation is in accordance with widespread compensatory evolution at the molecular level, caused by epistatic selection maintaining mRNA secondary structures [56]. The mechanism underlying epistatic selection is based on a model of compensatory fitness interactions [57], which suggests that mutations in RNA helices are individually deleterious but become neutral in appropriate combinations. The presence of significant excess of synonymous variation and clear influence of this variation on mRNA secondary structure stability suggests adaptive compensatory evolution in the lbe gene.

There are numerous studies devoted to synonymous site evolution in Drosophila [recent reviews in 43,58-60]. The main focus of these investigations is codon usage bias where different synonymous codons are used with different frequencies. It was shown that codon usage is tuned to optimize for expression and is adapted to tRNA pools of the organism. This is a type of purifying selection on synonymous sites preserving the usage of optimal codons [e.g., 42,45,61].

Analysis of the Notch locus in D. melanogaster has identified a region with accelerated synonymous site divergence [62]–[64]. The authors found an excess of fixed unpreferred codons and concluded that directional selection on synonymous sites had driven the fixation of these unpreferred codons. Later Holloway et al. [65] detected similar patterns for 64 genomic elements, a majority of which reside in protein-coding regions in the D. melanogaster genome. A genome-wide computational analysis showed that some unpreferred codons were fixed by directional selection in both bacteria and flies [66], [67]. Thus selection on synonymous sites is not limited to the preferential fixation of mutations that enhance the speed or accuracy of translation because in some situations selection for unpreferred codons can impede translation efficiency. Neafsey and Galagan [66] found that regulatory genes are particularly likely to be subject to selection for unpreferred codon usage. They suggested that low translational efficiency can be favored by reducing expressional noise through regulatory cascades [66]. Holloway et al. [65] hypothesized that ribosomal pausing for proper protein folding is a more tenable mechanism for explaining the preferable fixation of unpreferred codons than the alternative of reducing translation efficiency. However it was demonstrated that translational initiation of the ribosome can locally destabilize secondary structures and move along the mRNA without any significant delays [68] suggesting that the protein conformation alone cannot explain non-uniformity in translation elongation.

On the inter-specific level, we also found prevalent fixation of unpreferred codons in the lbe exon II (in D. melanogaster – D. simulans or D. sechellia comparisons, six out of eight synonymous changes lead to unpreferred codons). This pattern could not be explained by changes in mutation rates and/or low levels of recombination (see the section "Tests of Neutrality and Maximum Likelihood Analysis of Selective Pressures"). It is reasonable to suggest that directional selection on synonymous sites has driven the fixation of these unpreferred codons as in case with Notch and some other loci in Drosophila [62]–[67]. However intra-specific patterns of synonymous site variability in the lbe exon II suggest the involvement of balancing selection maintaining two different forms of mRNA molecules. Using site-specific codon models [69], [70], specifically developed to analyze site-specific variation, we detected a few sites in the lbe exon II where, despite strong codon bias due to negative selection on the whole gene, we observed very high rates of synonymous change consistent with balancing selection on those precise sites. Thus we found a site-specific phenomenon that cannot be explained by the influence of codon usage bias alone because divergent lbe coding haplotypes could not be a by-product of the selection on codon bias. Our data indicate that different mechanisms are involved in evolution of synonymous sites in the lbe gene compared to loci that have recent acceleration synonymous site divergence like Notch and some others (see references above). We argue that lbe intra-specific synonymous polymorphism is due to balancing selection maintaining two mRNA forms that can provide necessary functional flexibility [51], [58].

We detected contrasting patterns in nonsynonymous variation and rates in the lbe and lbl genes. While nonsynonymous mutations in lbe are prohibited, supposedly due to their strong detrimental effects on the LBE protein, three nonsynonymous mutations observed in lbl are predicted to have occurred under the influence of recurrent diversifying selection on the LBL protein. The level of the lbl nonsynonymous variability and d N rate variation was much higher than its level of synonymous variability. The excess of replacement substitutions cannot be due to relaxation of functional constraints, because this region contains the homeobox region, which is highly conserved on a wide phylogenetic scale [17]. Moreover, strong selective constraints on the lbl coding region may be imposed by the alternative splicing described for this gene [17]. We suggest that the lbl gene may pass through evolutionary periods of functional transformation marked by the prevalence of replacement substitutions within lbl exon III, against a background of intensive negative selection.

Thus the two lb homeobox genes show contrasting patterns of nucleotide and codon evolution. Moreover, we have found a highly asymmetric distribution of significant binding-site clusters, with >50 % of binding-site clusters specific for either lbe and lbl. The distinct binding-site profiles of lbe and lbl suggest that the genes are not redundant in developmental function. On the contrary, Jagla et al. [17], [18], [20], assert that lbe and lbl are functionally redundant.

We have previously suggested that the pattern of nucleotide variability of the Est-6 and bap coding regions in D. melanogaster are shaped by the influence of both directional and balancing selection [13], [26], [36]. Here, directional selection accounts for the excess of nearly identical sequences, and balancing selection prevents the complete fixation of haplotypes and increases the level of nucleotide variation. The present data show that both type of selection are involved in lbe and lbl evolution of D. melanogaster. A similar account has been proposed for the Adh and TFL1 loci of Arabidopsis thaliana [71], [72], the Acp29AB locus of D. melanogaster [73], the Pan I locus of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua [74], the MHC DQB1 locus of marine mammals Orcinus orca, Tursiops truncates, and T. aduncus [75], and the human AVPRIB gene [76]. Therefore, the operation and interaction of balancing and directional selection appears to be a general feature of molecular evolution in Drosophila and other eukaryote genomes.

The interaction between selective and neutral processes, nevertheless, should be cautiously interpreted given the modest sample size of sequences and the relatively short sequence lengths [e.g., 77]. Moreover, non-selective factors such as demography could partly account for the patterns of the polymorphisms. Demographic and selective forces shaping nucleotide polymorphism patterns in a species like D. melanogaster are difficult to disentangle because of its complicated history, including both recent worldwide migration and adaptation to drastically new environments [see, e.g., 78–80]. Patterns of polymorphism should be influenced by both of these evolutionary forces and is apparent in our data obtained for Sod, Est-6, ψEst-6, tin, bap, lbe, and lbl located on the third chromosome from four natural D. melanogaster populations (Africa, Europe, North and South America). Comparative analysis showed significant peaks of variability in the Est-6 region observed both in African and non-African samples, but dimorphic structure was detected only in non-African samples [26]. This observation supports the hypothesis that dimorphic haplotype structure is generated by demographic process during the recent history of D. melanogaster caused by admixture of differentiated populations\. Significant peaks of increased nucleotide variability accompanied by peaks of LD and centered on the functionally important sites may reflect the effects of balancing selection [13], [26], [36], [40], [81] – this hypothesis was predicted by theoretical analysis [82]–[86].

Each gene family has its own evolutionary history. Consequently, a full understanding of their evolution may require comprehensive data be obtained for all multigene families in the genome. Distinguishing between demography and selection, or establishing the relative importance of these evolutionary factors in the patterning of molecular variation may not be sufficient to achieve a deeper understanding of the whole nature of molecular variation evolving under multidirectional evolutionary forces. Consequently, future investigations are needed in other species and genes of Drosophila in order to resolve these problems.

Materials and Methods

The D. melanogaster strains derive from wild flies collected in Europe (Barcelona, Spain; 19 strains), North America (California; 28 strains), and South America (Caracas, Venezuela; 19 strains). The strains were made fully homozygous for the third chromosome by crosses with balancer stocks, as described by Seager and Ayala [87]. Chung-I Wu kindly provided the isofemale D. melanogaster strains from East Africa (Sengwa, Zimbabwe). The three African strains included in our analysis were homozygous for the lbe and lbl gene regions. The strains used in the present study were previously investigated for the β-esterase gene cluster [26], [27], [36] and the homeobox genes tin and bap [13]. The lb sequences of D. melanogaster, as well as those of D. sechellia, D. simulans, and D. yakuba were obtained from GenBank (accession numbers: NT_033777.2, AAKO01001614, AAEU02001386, AAEU02001382, AAGH01024581, and AAKO01001614).

DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted using the tissue protocol of the QIAamp Tissue Kit (QIAGEN®). The primers used for the lbe PCR amplification reactions were: 5′-aacgtgctcgagata-acaaatgacc-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-agaagaaccatcgattgctaagaag-3′ (reverse primer). The primers used for the lbl PCR amplification reactions were: 5′-atttccgttgatactttggctgag-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-tgttggcgaaatagtgaatatctg-3′ (reverse primer). Methods are as previously described [36]. The sequences of both strands were determined for each line, using 12 overlapping internal primers spaced, on average, 500 nucleotides. At least two independent PCR amplifications were sequenced for each polymorphic site in all D. melanogaster strains to prevent possible PCR and sequencing errors. The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences are FJ754496 – FJ754564 and FJ754565 – FJ754633.

DNA Sequence Analysis

The lbe and lbl sequences were assembled using the program SeqMan (Lasergene, DNASTAR, Inc.). Multiple alignment was carried out manually and using the program CLUSTAL W [88]. The "sliding window" method of Hudson and Kaplan [83] and most intra-specific analyses were performed using DnaSP v. 4.10.9 [89] and PROSEQ v. 2.9 [90]. Departures from neutral expectations were investigated using HKA [91], Tajima's [35], McDonald and Kreitman's [92], Kelly's [33], and Wall's [34] tests. Simulations based on the coalescent process with or without recombination [93]–[95] were performed with DnaSP and PROSEQ to estimate the probabilities of the observed values of Tajima's D, Kelly's ZnS and Wall's B and Q statistics and confidence intervals of the nucleotide diversity values. Simulations with 10,000 replicates were conditional on the sample size, the observed number of segregating sites, and the DNA alignment length, with the population recombination rate parameter (ρ = 4N0r) set to the gene estimates. The permutation approach of Hudson et al. [96] was used to estimate the significance of sequence differences between populations and haplotype families and the method of Sawyer [31] to detect gene conversion events. The population recombination rate was analyzed with a permutation-based approach [97].

Codon-Based Sequence Analyses

Probabilistic Markov codon-substitution models were fitted to coding alignments. Model parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood. These models measure selective pressure using the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates ω = d N/d S, which may vary among sites. Positive or negative selection is evidenced by significant deviations of the ω-ratio from 1. We used models that assume constant synonymous rates M0, M3, M7, M8 [98] and FMutSel0, FMutSel [99] as implemented in PAML v. 4 [100], and a model accounting for variability of synonymous rate over sites GYxHKY Dual GDD 3×3 of [70], later referred as M3-Dual and implemented in HYPHY [69]. Hypotheses concerning selection, codon bias, and rate variability were tested using likelihood ratio tests (LRTs). For a review on the application of codon models see [101]. Models combining coding and noncoding sequences were used to test for positive selection on noncoding regions, as implemented in EvoNC [102]. The strength of selection on noncoding regions was measured by ζ, the ratio of the substitution rate in noncoding regions relative to the synonymous rate in coding regions. Under neutrality, these rates are expected to be similar (ζ≈1). Significant deviations from 1 may be considered as evidence of positive (ζ>1) or negative (ζ<1) selection on noncoding regions. Consequently, the null model allowed two classes of sites in noncoding regions: a neutral class with ζ = 1 and a class of sites evolving under negative selection where the average exonic synonymous rate was higher than the substitution rate in the noncoding regions (ζ<1). The alternative model also allowed two classes of sites, but the rate ratio was estimated for both classes under constraints: ζ≥1 for positive and neutral selection class, and ζ<1 for the negatively selected class. A Bayesian approach was used to predict sites affected by positive selection in both coding and noncoding regions [70], [98], [102], [103].

Supporting Information

DNA polymorphism in the lbe gene of 70 strains of Drosophila melanogaster . Symbols for strains: ER, El Rio; Ven, Venezuela; Bar, Barcelona; letters before and after the number refer to the electrophoretic allele observed in earlier studies at two loci: esterase-6, before the hyphen, and superoxide dismutase, after the hyphen (S, Slow; F, Fast; US, Ultra Slow). MEL, the lbe sequence obtained from GenBank (accession number, NT 033777.2). Lines are arranged successively according to genetic similarity. Numbers on top represent the position of segregating sites and the start of a deletion or insertion. Nucleotides are numbered from the beginning of our sequence. Coding regions of the genes are underlined below the top, reference sequence. Dots indicate same nucleotide as reference sequence. A hyphen represents deleted nucleotides. ▴ denotes a deletion; † absence of a deletion; ▾ insertion; ‡ absence of an insertion. Numbers after symbols for the deletions and insertions refer to the particular deletions and insertions. ▴1, a single nucleotide deletion of G (position 676); ▴2, a single nucleotide deletion of T (position 812); ▴3, a 5-bp deletion of TGGAA (position 1710–1714); ▴4, a 4-bp deletion of TAAA (position 1829–1832); ▴5, a 29-bp deletion of TTCAAATGAAGGTGTTTCGTATAATATCA (position 1876–1904); ▴6, a 30-bp deletion of TCGTATAATATCAATATTCCAACACTACA-A (position 1892–1921); ▾1, a 22-bp insertion of TAGTTGCTCCATGTAACCATGT (position 1953-1974); ▴7, a 8-bp deletion of AGCAACTA (position 1975–1982); ▴8, a 2-bp deletion of AA (position 2006–2007); ▾2, a 10-bp insertion of TGATTTTTTT (position 2008–2017). Coordinates for functional regions of genes are: 1–950 (lbe, intron I), 951–1382 (lbe, exon II), 1383–2044 (lbe, 3′-flanking region).

(DOC)

DNA polymorphism in the lbl gene of 70 strains of Drosophila melanogaster . Amino acid replacement polymorphisms are marked with asterisks (nucleotide under selection is in boldface). Coordinates for the functional regions of the gene are: 1–738 (lbl, intron I), 738–918 (lbl, exon II), 919–1523 (lbl, intron II), 1524–1766 (lbl, exon III), 1767–2438 (lbl, 3′-flanking region). ▾1, a single nucleotide insertion of A (position 973); ▴1, a 78-bp deletion of AATATATTTTTTTGCTGCAAATCTGCTGTTTTTCGCTTTTCTCAGCGAAAT-ATGTACTATTTTCAGTTAAAATATAAT (position 1059–1136); ▾2, a 12-bp insertion of ATAATAAAATAT (position 1132–1143); ▾3, a 24-bp insertion of AAAATATTAATTAATT-TATTATTA (position 1137–1160); ▴2, a 26-bp deletion of CACAAAAGATATCCATTTCTG-GATAT (position 1161–1186); ▴3, a 237-bp deletion of CACAAAAGATATCCATTTCTGG-ATATGAATGAAGTGCATCTTATTCCGACTGACAATTTTGTAGGGAAATGGTAGAGTCGCCTGGCAGTGACTATTTATTTTTCAGTCAACATGTATATAATGTGCATTGTTTTTCCTTTGGCTGAGTAAATGTATCTCGAACTCGACTACAACTCTCTGTTGTTTTTTCTAACCATTTTGTTCTAATGTCAGCAAATTAATAAATATATGCGTCCT (position 1161–1398); ▴4, a single nucleotide deletion of T (position 1263); ▴5, a single nucleotide deletion of A (position 1349); ▴6, a 9-bp deletion of ACACCAGCA (position 1719–1727); ▴7, a 6-bp deletion of GCACCA (1728–1733); ▴8, a 32-bp deletion of CGTTCGCCGTTGAGAATAA-TCGTAAACCATTC (position 2347–2378). Other comments: see Figure S1.

(DOC)

Fisher exact test of nonrandom associations between pairs of lbe and lbl polymorphisms. Singleton mutations are excluded from the analysis. Each box in the matrix represents the comparison of two polymorphic sites. Location of the segregating sites on lbe and lbl genes is shown on the diagonal, which indicates the position of the 5′-flanking, coding, and 3′-flanking regions. 0.01<P<0.05 (grey); 0.001<P<0.01 (dark grey); P<0.001 (black). Intergenic associations are boxed.

(TIF)

Nucleotide diversity and divergence in the lbe gene region of D. melanogaster .

(DOC)

Nucleotide diversity and divergence in the lbl gene region of D. melanogaster .

(DOC)

Nucleotide diversity and divergence in the ladybird gene region of D. melanogaster .

(DOC)

Recombination estimates ( ρ ).

(DOC)

Gene conversion events in the lbe and lbl genes of D. melanogaster .

(DOC)

Linkage disequilibrium between functional regions of the lbe and lbl genes.

(DOC)

Kelly's (Kelly 1997) and Wall’s (Wall 1999) tests of neutrality for the lbe and lbl gene regions.

(DOC)

Statistical significance of the binding site cluster for the lbe and lbl genes.

(DOC)

Nucleotide polymorphism.

(DOC)

Haplotype structure.

(DOC)

Linkage disequilibrium.

(DOC)

Neutrality and maximum likelihood (ML) analysis of selective pressures.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena Balakireva and Andrei Tatarenkov for encouragement and help; and three anonymous reviewers for valuable comments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This study was supported by Bren Professor Funds at the University of California, Irvine to F. J. Ayala and E. S. Balakirev and Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich to Maria Anisimova. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prud'homme B, Gompel N, Carroll SB. Emerging principles of regulatory evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(Suppl 1):8605–8612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700488104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wray GA. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:206–216. doi: 10.1038/nrg2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll SB. Evo-devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: A genetic theory of morphological evolution. Cell. 2008;134:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch VJ, Wagner GP. Resurrecting the role of transcription factor change in developmental evolution. Evolution. 2008;62:2131–2154. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galant R, Carroll SB. Evolution of a transcriptional repression domain in an insect Hox protein. Nature. 2002;415:910–913. doi: 10.1038/nature717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronshaugen M, McGinnis N, McGinnis W. Hox protein mutation and macroevolution of the insect body plan. Nature. 2002;415:914–917. doi: 10.1038/nature716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huff CD, Harpending HC, Rogers AR. Detecting positive selection from genome scans of linkage disequilibrium. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavlidis P, Jensen JD, Stephan W. Searching for footprints of positive selection in whole-genome SNP data from nonequilibrium populations. Genetics. 2010;185:907–922. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.116459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong M, Lange K, Papp JC, Fan R. A powerful score test to detect positive selection in genome-wide scans. Europ J Human Genet. 2010;18:1148–1159. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark AG, Eisen MB, Smith DR, Bergman CM, Oliver B, et al. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haerty W, Artieri C, Khezri N, Singh RS, Gupta BP. Comparative analysis of function and interaction of transcription factors in nematodes: Extensive conservation of orthology coupled to rapid sequence evolution. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moriyama EN, Powell JR. Intraspecific nuclear DNA variation in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:261–277. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balakirev ES, Ayala FJ. Nucleotide variation in the tinman and bagpipe homeobox genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2004a;166:1845–1856. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jovelin R, Dunham JP, Sung FS, Phillips PC. High nucleotide divergence in developmental regulatory genes contrasts with the structural elements of olfactory pathways in Caenorhabditis. Genetics. 2009;181:1387–1397. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purugganan MD. The molecular population genetics of regulatory genes. Mol Ecol. 2000;9:1451–1461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim Y, Nirenberg N. Drosophila NK-homeobox genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7716–7720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagla K, Bellard M, Frasch M. A cluster of Drosophila homeobox genes involved in mesoderm differentiation program. BioEssays. 2001;23:125–133. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200102)23:2<125::AID-BIES1019>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagla K, Jagla T, Heitzler P, Dretzen G, Bellard F, et al. ladybird, a tandem of homeobox genes that maintain late wingless expression in terminal and dorsal epidermis of the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1997;124:91–100. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagla K, Stanceva I, Dretzen G, Bellard F, Bellard M. A distinct class of homeodomain proteins is encoded by two sequentially expressed Drosophila genes from the 93D/E cluster. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:1202–1207. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.7.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Graeve F, Jagla T, Daponte J-P, Rickert C, Dastugue B, et al. The ladybird homeobox genes are essential for the specification of a subpopulation of neural cells. Dev Biol. 2004;270:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manuel M, Le Parco Y. Homeobox gene diversification in the calcareous sponge, Sycon raphanus. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2000;17:97–107. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SE, Gates RD, Jacobs DK. Gene fishing: the use of a simple protocol to isolate multiple homeodomain classes from diverse invertebrate taxa. J Mol Evol. 2003;56:509–516. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagla K, Dollé P, Mattei M-G, Jagla T, Schuhbaur B, et al. Mouse Lbx1 and human LBX1 define a novel mammalian homeobox gene family related to the Drosophila lady bird genes. Mech Dev. 1995;53:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietrich S, Schubert FR, Healy C, Sharpe PT, Lumsden A. Specification of the hypaxial musculature. Development. 1998;125:2235–2249. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanamoto T, Terada K, Yoshikawa H, Furukawa T. Cloning and expression pattern of lbx3, a novel chick homeobox gene. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balakirev ES, Ayala FJ. Nucleotide variation of the Est-6 gene region in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;165:1901–1914. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balakirev ES, Ayala FJ. The β-esterase gene cluster of Drosophila melanogaster: Is ψEst-6 a pseudogene, a functional gene, or both? Genetica. 2004b;121:165–179. doi: 10.1023/b:gene.0000040391.27307.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing Y, Lee C. Evidence of functional selection pressure for alternative splicing events that accelerate evolution of protein subsequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13526–13531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501213102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meireles-Filho ACA, Stark A. Comparative genomics of gene regulation-conservation and divergence of cis-regulatory information. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudson RR, Kaplan N. Statistical properties of the number of recombination events in the history of a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics. 1985;111:147–164. doi: 10.1093/genetics/111.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawyer SA. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:526–538. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hudson RR, Bailey K, Skarecky D, Kwiatowski J, Ayala FJ. Evidence for positive selection in the superoxide dismutase Sod region of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1994;136:1329–1340. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.4.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly JK. A test of neutrality based on interlocus associations. Genetics. 1997;146:1197–1206. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wall JD. Recombination and the power of statistical tests of neutrality. Genet Res. 1999;74:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balakirev ES, Balakirev EI, Ayala FJ. Molecular evolution of the Est-6 gene in Drosophila melanogaster: Contrasting patterns of DNA variability in adjacent functional regions. Gene. 2002;288:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wayne ML, Simonsen K. Statistical tests of neutrality in the age of weak selection. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:1292–1299. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen R. Statistical tests of selective neutrality in the age of genomics. Heredity. 2001;86:641–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anisimova M, Bielawski JP, Yang Z. Accuracy and power of the likelihood ratio test in detecting adaptive molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1585–1592. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balakirev ES, Anisimova M, Ayala FJ. Positive and negative selection in the β-esterase gene cluster of the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. J Mol Evol. 2006;62:496–510. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Resch AM, Carmel L, Mariño-Ramírez L, Ogurtsov AY, Shabalina SA, et al. Widespread positive selection in synonymous sites of mammalian genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1821–1831. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parmley JL, Chamary JV, Hurst LD. Evidence for purifying selection against synonymous mutations in mammalian exonic splicing enhancers. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:301–309. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamary JV, Parmley JL, Hurst LD. Hearing silence: non-neutral evolution at synonymous sites in mammals. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:98–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:603–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akashi H. Synonymous codon usage in Drosophila melanogaster: natural selection and translational accuracy. Genetics. 1994;136:927–935. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duret L. Evolution of synonymous codon usage in metazoans. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:640–649. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00353-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reuter JS, Mathews DH. RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ling SH, Cheng Z, Song H. Structural aspects of RNA helicases in eukaryotic mRNA decay. Biosci Rep. 2009;29:339–349. doi: 10.1042/BSR20090034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klaff P, Riesner D, Steger G. RNA structure and the regulation of gene expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:89–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00039379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Floris M, Mahgoub H, Lanet E, Robaglia C, Menand B. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in plants during abiotic stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:3168–3185. doi: 10.3390/ijms10073168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nackley AG, Shabalina SA, Tchivileva IE, Satterfield K, Korchynskyi O, et al. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science. 2006;314:1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1131262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kudla G, Murray AW, Tollervey D, Plotkin JB. Coding-sequence determinants of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Science. 2009;324:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1170160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basak S, Mukhopadhyay P, Gupta SK, Ghosh TC. Genomic adaptation of prokaryotic organisms at high temperature. Bioinformation. 2010;4:352–356. doi: 10.6026/97320630004352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Down TA, Bergman CM, Hubbard TJP. Large-scale discovery of promoter motifs in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;31:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papatsenko D. ClusterDraw web server: a tool to identify and visualize clusters of binding motifs for transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1032–1034. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirby DA, Muse SV, Stephan W. Maintenance of pre-mRNA secondary structure by epistatic selection. Proc Natl Acad U S A. 1995;92:9047–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimura M. The role of compensatory neutral mutations in molecular evolution. J Genet. 1985;64:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parmley JL, Hurst LD. How do synonymous mutations affect fitness? BioEssays. 2007;29:515–519. doi: 10.1002/bies.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hershberg R, Petrov DA. Selection on codon bias. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:287–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plotkin JB, Kudla G. Synonymous but not the same: the causes and consequences of codon bias. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akashi H. Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at “silent” sites in Drosophila DNA. Genetics. 1995;139:1067–1076. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauer DuMont VL, Fay JC, Calabrese PP, Aquadro CF. DNA variability and divergence at the Notch locus in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: A case of accelerated synonymous site divergence. Genetics. 2004;167:171–185. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bauer DuMont VL, Singh ND, Wright MH, Aquadro CF. Locus-specific decoupling of base composition evolution at synonymous sites and introns along the Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila sechellia lineages. Genome Biol Evol. 2009;2009:67–74. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen R, Bauer DuMont VL, Hubisz MJ, Aquadro CF. Maximum likelihood estimation of ancestral codon usage bias parameters in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:228–235. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holloway AK, Begun DJ, Siepel A, Pollard KS. Accelerated sequence divergence of conserved genomic elements in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 2008;18:1592–1601. doi: 10.1101/gr.077131.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neafsey DE, Galagan JE. Positive selection for unpreferred codon usage in eukaryotic genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-119. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh ND, Bauer DuMont VL, Hubisz MJ, Nielsen R, Aquadro CF. Patterns of mutation and selection at synonymous sites in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2687–2697. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leibhaber SA, Cash FE, Shakin SH. Translationally associated helix-destabilizing activity in rabbit reticulocyte lysate. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:15597–15602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Muse SV. Site-to-site variation of synonymous substitution rates. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2375–2385. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hanfstingl U, Berry A, Kellogg EA, Costa JT, Rüdiger W W, et al. Haplotype divergence coupled with lack of diversity at the Arabidopsis thaliana alcohol dehydrogenase locus: roles for both balancing and directional selection? Genetics. 1994;138:811–828. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olsen KM, Womack A, Garrett AR, Suddith JI, Purugganan MD. Contrasting evolutionary forces in the Arabidopsis thaliana floral developmental pathway. Genetics. 2002;160:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aguadé M. Positive selection drives the evolution of the Acp29AB accessory gland protein in Drosophila. Genetics. 1999;152:543–551. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pogson GH. Nucleotide polymorphism and natural selection at the Pantophysin Pan I locus in the Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua L. Genetics. 2001;157:317–330. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vassilakos D, Natoli A, Dahlheim M, Hoelzel R. Balancing and directional selection at exon-2 of the MHC DQB1 locus among populations of odontocete cetaceans. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:681–689. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cagliani R, Fumagalli M, Pozzoli U, Riva S, Cereda M, et al. A complex selection signature at the human AVPRIB gene. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jensen JD, Thornton KR, Aquadro CF. Inferring selection in partially sequenced regions. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:438–446. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lachaise D, Silvain JF. How two Afrotropical endemics made two cosmopolitan human commensals: the Drosophila melanogaster-D. simulans palaeogeographic riddle. Genetica. 2004;120:17–39. doi: 10.1023/b:gene.0000017627.27537.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haddrill PR, Thornton KR, Charlesworth B, Andolfatto P. Multilocus patterns of nucleotide variability and the demographic and selection history of Drosophila melanogaster populations. Genome Res. 2005;15:790–799. doi: 10.1101/gr.3541005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stephan W, Li H. The recent demographic and adaptive history of Drosophila melanogaster. Heredity. 2007;98:65–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Balakirev ES, Balakirev EI, Rodriguez-Trelles F, Ayala FJ. Molecular evolution of two linked genes, Est-6 and Sod, in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;153:1357–1369. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.3.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Strobeck C. Expected linkage disequilibrium for a neutral locus linked to a chromosomal arrangement. Genetics. 1983;103:545–555. doi: 10.1093/genetics/103.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hudson RR, Kaplan N. The coalescent process in models with selection and recombination. Genetics. 1988;120:831–840. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaplan NL, Darden T, Hudson RR. The coalescent process in models with selection. Genetics. 1988;120:819–29. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Charlesworth D. Balancing selection and its effects on sequences in nearby genome regions. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(4):e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020064. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Charlesworth B, Nordborg M, Charlesworth D. The effects of local selection, balanced polymorphism and background selection on equilibrium patterns of genetic diversity in subdivided populations. Genet Res. 1997;70:155–174. doi: 10.1017/s0016672397002954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seager RD, Ayala FJ. Chromosome interactions in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Viability studies. Genetics. 1982;102:467–483. doi: 10.1093/genetics/102.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Filatov DA. PROSEQ: a software for preparation and evolutionary analysis of DNA sequence data sets. Mol Ecol Notes. 2002;2:621–624. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hudson RR, Kreitman M, Aguadé M. A test of neutral molecular evolution based on nucleotide data. Genetics. 1987;116:153–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/116.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hudson RR. Properties of a neutral allele model with intragenic recombination. Theor Popul Biol. 1983;23:183–201. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(83)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hudson RR. Gene genealogies and the coalescent process. Oxf Surv Biol. 1990;7:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hudson RR. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:337–338. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hudson RR, Boos D, Kaplan NL. A statistical test for detecting geographic subdivision. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:138–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McVean G, Awadalla P, Fearnhead P. A coalescent-based method for detecting and estimating recombination from gene sequences. Genetics. 2002;160:1231–1241. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.3.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]