Abstract

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, a critical signal transduction system linking oncogenes and multiple receptor classes to many essential cellular functions, is perhaps the most commonly activated signaling pathway in human cancer. This pathway thus presents both an opportunity and a challenge for cancer therapy. Even as inhibitors that target PI3K isoforms and other major nodes in the pathway including AKT and mTOR reach clinical trials, major issues remain. Here we highlight recent progress made in our understanding of the PI3K pathway and discuss both the promises and challenges for the therapeutic development of agents targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer.

Introduction

Since its discovery in the 1980s, the family of lipid kinases termed phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) has been found to play key regulatory roles in many cellular processes including cell survival, proliferation and differentiation1-3. As major effectors downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), PI3Ks transduce signals from various growth factors and cytokines into intracellular messages by generating phospholipids, which in turn activate the serine/threonine kinase AKT and other downstream effector pathways (FIG. 1). The tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted from chromosome 10) is the most important negative regulator of the PI3K signaling pathway4, 5. Recent human cancer genomic studies have revealed that many components of the PI3K pathway are frequently targeted by germline or somatic mutations in a broad spectrum of human cancers. These findings, and the fact that PI3K and other kinases in the PI3K pathway are highly suited for pharmacologic intervention, make this pathway one of the most attractive targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer6.

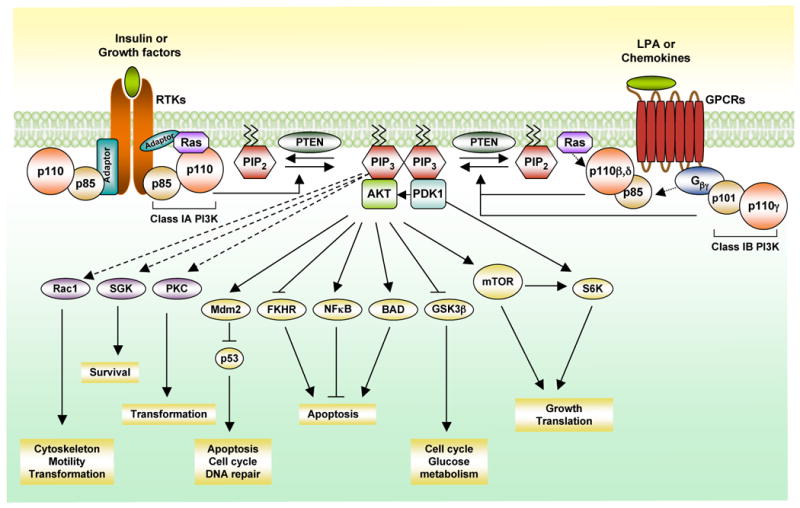

Figure 1. The Class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway.

Upon growth factor stimulation and subsequent activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), class IA PI3Ks, consisting of p110α/p85, p110β/p85 and p110δ/p85, are recruited to the membrane via interaction of the p85 subunit to the activated receptors directly (e.g.PDGFR) or to adaptor proteins associated with the receptors (e.g. insulin receptor substrate 1, IRS1). The activated p110 catalytic subunit converts phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) at the membrane, providing docking sites for signaling proteins with pleckstrin-homology (PH) domains including the phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and the Ser-Thr kinase AKT. PDK1 phosphorylates and activates AKT (also known as PKB). The activated AKT elicits a broad spectrum of downstream signaling events. Class IB PI3K (p110γ/p101) can be activated directly by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) through interacting with the Gβγ subunit of trimeric G proteins. The p110β and p110δ can also be activated by GPCRs. PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) antagonizes the PI3K action by dephosphorylating PIP3. G βγ, guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), βγ; FKHR, forkhead transcription factor; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; BAD, Bcl-2-associated death promoter protein; SGK, Serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; Rac1, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1; S6K, ribosomal protein S6 kinase; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid.

Pathway background

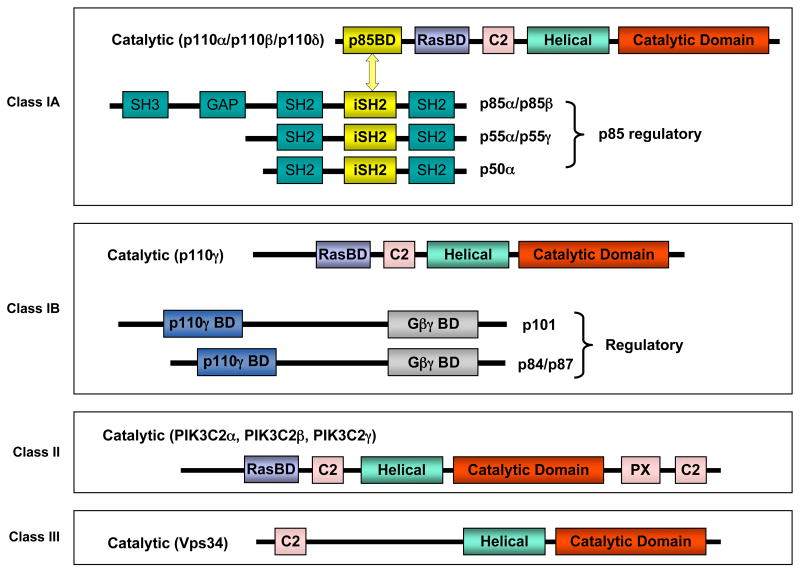

PI3Ks have been divided into three classes according to their structural characteristics and substrate specificity 7, 8(FIG. 2a). Of these, the most commonly studied are the class I enzymes that are activated directly by cell surface receptors. Class I PI3Ks are further divided into class IA enzymes, activated by RTKs, GPCRs and certain oncogenes such as the small G protein Ras, and class IB enzymes, regulated exclusively by GPCRs.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. The members of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) family. PI3Ks have been divided into three classes according to their structural characteristics and substrate specificity. Class IA PI3Ks are heterodimers consisting of a p110 catalytic subunit and a p85 regulatory subunit. In mammals, there are three genes, PIK3CA, PIK3CB and PIK3CD, encoding p110 catalytic isoforms: p110α, p110β and p110δ, respectively. While the expression of p110δ is largely restricted to the immune system, p110α and p110β are ubiquitously expressed1, 8. The p110 catalytic isoforms are highly homologous and share five distinct domains: an N-terminal p85-binding domain (p85BD) that interacts with the p85 regulatory subunit, a Ras-binding domain (RasBD) that mediates activation by members of the Ras family of small GTPases, a putative membrane-binding domain C2, the helical domain, and the C-terminal kinase catalytic domain. There are also three genes, PIK3R1, PIK3R2 and PIK3R3, encoding p85α (and its splicing variants p55α and p50 α), p85β and p55γ regulatory subunits, respectively, collectively called p85. These regulatory subunits share three core domains including a p110-binding domain (denoted as inter-SH2 or iSH2) flanked by two Src-homology 2 (SH2) domains (N-terminal nSH2 and C-terminal cSH2). The two longer isoforms, p85α and p85β, have a Src-homology 3 (SH3) domain and a BCR homology (BH) domain located in their extended N-terminal regions. In the basal state, p85 binds to the N-terminus of the p110 subunit via its iSH2 domain, inhibiting its catalytic activity7, 8. Class IB PI3K is a heterodimer composed of a catalytic subunit p110γ and a regulatory subunit p101. p110γ is mainly expressed in leukocytes and can be activated directly by GPCRs8. Class II PI3Ks are monomers with only a single catalytic subunit.There are three class II PI3K isoforms, PI3KC2α, PI3KC2β and PI3KC2γ, each of which has a divergent N-terminus followed by a Ras binding domain (RasBD), C2 domain, helical domain, and catalytic domain with PX and C2 domains at the C-termini (reviewed in REF1, 2). Class III PI3Ks consists of a single catalytic subunit Vps34 (homolog of the yeast vacuolar protein-sorting defective 34).

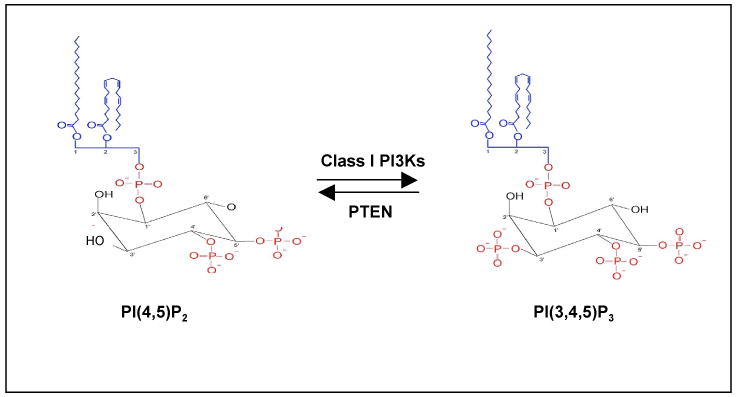

Figure 2b. The level of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate, PI(3,4,5)P3, is regulated by Class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN). PI(3,4,5)P3 is an important lipid second messenger that regulates multiple cellular processes. Class I PI3Ks phosphorylates the inositol ring of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-triphosphate, PI(4,5)P2 on the 3-position, to generate PI(3,4,5)P3. PTEN is a lipid phosphatase that removes phosphate on the 3-position of PI(3,4,5)P3 and converts it back to PI(4,5)P2.

Class IA PI3Ks

Are heterodimers consisting of a p110 catalytic subunit and a p85 regulatory subunit (FIG. 2a). The regulatory subunit mediates receptor binding, activation, and localization of the enzyme. In mammals, there are three genes, PIK3R1, PIK3R2 and PIK3R3, encoding p85α (and its splicing variants p55α and p50α), p85β and p55γ regulatory subunits, respectively, collectively called p85 (reviewed in REF1, 2). In response to growth factor stimulation and the subsequent activation of RTKs, PI3K is recruited to the membrane via interaction of its p85 subunit to tyrosine phosphate motifs on activated receptors directly (e.g. PDGFR) or to adaptor proteins associated with the receptors (e.g. insulin receptor substrate 1, IRS1). The activated p110 catalytic subunit generates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, PI(3,4,5)P3, which in turn activates multiple downstream signaling pathways (FIG. 1 and 2b).

Class IB PI3K

Is a heterodimer composed of a catalytic subunit p110γ and a regulatory subunit p1018 (FIG. 2a). Two new regulatory subunits, p84 and p87PIKAP, have been recently described 9, 10. p110γ is activated directly by GPCRs through interaction of its regulatory subunit with the Gβγ subunit of trimeric G proteins8. p110γ is mainly expressed in leukocytes but is also found in the heart, pancreas, liver and skeletal muscles 11-13.

Class II PI3Ks

Consist of a single catalytic subunit, which preferentially uses PI or PI(4)P as substrates1, 2 (FIG. 2a). There are three class II PI3K isoforms, PI3KC2α, PI3KC2β and PI3KC2γ, which can be activated by RTKs, cytokine receptors, and integrins; however, the specific cellular functions of this family remain unclear.

Class III PI3K

Consists of a single catalytic Vps34 subunit (homolog of the yeast vacuolar protein-sorting defective 34). Vps34 only produces PI(3)P, an important regulator of membrane trafficking (reviewed in REF1), and has been shown to function as a nutrient-regulated lipid kinase mediating signaling through mTOR (mammalian target of mTOR), indicating a potential role in regulating cell growth14. Interestingly, it has also been implicated as an important regulator of autophagy (reviewed in REF14), a cellular response to nutrient starvation.

PTEN

The phospholipid PI(3,4,5)P3 generated by activated class I PI3Ks is the key second messenger that drives multiple downstream signaling cascades regulating cellular processes (FIG. 1). The cellular level of PI(3,4,5)P3 is tightly regulated by the opposing activity of PTEN. PTEN, an important tumor suppressor, functionally antagonizes PI3K activity via its intrinsic lipid phosphatase activity that reduces the cellular pool of PIP3 by converting PI(3,4,5)P3 back to PI(4,5)P2 (FIG. 2b). Loss of PTEN will result in unrestrained signaling by the PI3K pathway leading to cancer (reviewed in REF5)

AKT

Also known as protein kinase B, is a serine/threonine kinase expressed as three isoforms, AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3, which are encoded by the genes PKBα, PKBβ, and PKBγ, respectively (reviewed in REF3, 15). All three isoforms possess a similar structure: an N-terminal PH domain, a central serine/threonine catalytic domain, and a small C-terminal regulatory domain. AKT activation is initiated by translocation to the plasma membrane mediated by docking of the PH domain in the N-terminal region of AKT to PI(3,4,5)P3 on the membrane, resulting in a conformational change in AKT, exposing two critical amino acid residues for phosphorylation16, 17. Both phosphorylation events, T308 by PDK1 and S473 by PDK2, are required for full activation of AKT 3,16, 17. A number of potential PDK2s have been identified, including ILK (integrin-linked kinase), PKCbII, DNA-PK (DNA-dependent protein kinase) and ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated), and AKT itself 15; however it is currently thought that mTORC2 (the mTOR/rictor complex) is the primary source of PDK2 activity under most circumstances 18. Once phosphorylated and activated, AKT phosphorylates many other proteins, e.g. GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase 3) and FOXOs (the forkhead family of transcription factors), thereby regulating a wide range of cellular processes involved in protein synthesis, cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism (reviewed in REF 15, 19).

mTOR

mTOR plays a pivotal role in the regulation of cell growth and proliferation by monitoring nutrient availability, cellular energy levels, oxygen levels, and mitogenic signals (reviewed in REF20). Notably, mTOR belongs to a group of Ser/Thr protein kinases of the PI3K superfamily referred to as class IV PI3Ks, including ATM, ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related), DNA-PK and SMG-1 (SMG1 homolog, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase). mTOR exists in two distinct complexes - mTORC1 and mTORC2. The mTORC1 complex is composed of the mTOR catalytic subunit, Raptor (regulatory associated protein of mTOR), PRAS40 (proline-rich AKT substrate 40 kDa) and the protein mLST8/GbL (reviewed in REF 20, 21). mTORC2 is composed of mTOR, Rictor (rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR), mSIN1 (mammalian stress-activated protein kinase interacting protein 1) and mLST8/GbL 21.

AKT can activate mTOR by phosphorylating both PRAS40 and TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex) to attenuate their inhibitory effects on mTORC1 22-24. The finding of the association of mTORC1 with the bipartite complex TSC1 and TSC2 of tumor suppressor proteins provided a molecular link between mTOR and cancer (reviewed in REF 25). The best characterized downstream targets of mTORC1 are S6K1 (p70S6 kinase) and 4E-BP1 (4E-binding protein), both of which are critically involved in the regulation of protein synthesis (reviewed in REF 26). Thus, activation of mTOR may provide tumor cells with a growth advantage by promoting protein synthesis. When bound to Rictor in the mTORC2 complex, mTOR functions as PDK2 to phosphorylate AKT18.

Linking the PI3K pathway to human cancers

Although PI3K was originally characterized two decades ago via its binding to oncogenes and activated RTKs (reviewed in REF27), its association with human cancer was not established until the late 1990s, when it was shown that the tumor suppressor PTEN acts as a PI3-lipid phosphatase. Recent comprehensive cancer genomic analyses have revealed that multiple components of the PI3K pathway are frequently mutated or altered in common human cancers 28-33, underscoring the importance of this pathway in cancer.

The discovery of the PTEN tumor suppressor ties PI3K to human cancer

Germline mutations in the PTEN gene cause a variety of inherited cancer predisposition syndromes including Cowden syndrome and Bannayan-Zonana syndrome34. Somatic loss of PTEN by gene mutation or deletion occurs in a high percentage of common human tumors (TABLE 1). The discovery that the tumor suppressor PTEN works by antagonizing PI3K established the first direct link between PI3K activation and human cancer. While PTEN possesses protein tyrosine phosphatase activity 35, it is also a lipid phosphatase capable of specifically removing the 3′ phosphate from PI(3,4,5)P3, an action which is essential to its function as a tumor suppressor (reviewed in REF 36, 37). Not surprisingly, PI3K signaling was found to be hyperactive in PTEN-null tumor cell lines and primary tumors4. The human disease phenotypes associated with PTEN loss have been recapitulated in mouse genetic models (reviewed in REF 36, 38). Heterozygous loss or tissue specific homozygous loss of PTEN in the mouse leads to hyperplastic proliferation and neoplastic transformation in multiple tissues 39-43.

Table 1. Incidence of genetic alterations in the PI3K pathway in cancer.

| Genetic alterations | Cancer type | Incidence of tumors with alterations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| p110a (PIK3CA) | |||

| Mutations | Breast | 27% (468/1766) | * |

| Endometrial | 24% (102/429) | * | |

| Colon | 15% (448/3024) | * | |

| upper digestive tract | 11% (38/352) | * | |

| gastric | 8% (29/362) | * | |

| Pancreas | 8% (8/104) | * | |

| Ovarian | 8% (61/787) | * | |

| Liver | 6% (19/303) | * | |

| brain | 5.9% (59/996) | *, 29, 30 | |

| Esophageal | 5% (13/239) | * | |

| Lung | 3% (28/962) | * | |

| melanoma | 9% (24/278) | * | |

| urinary tract | 17% (28/162) | * | |

| prostate | 2% (1/57) | * | |

| thyroid | 2% (7/394) | * | |

| Amplifications | Lung | ||

| SQC | 53%(40/75) | 147-149 | |

| ADC | 12.5% (15/120) | 147-149 | |

| SCC | 21.4% (3/14) | 147-149 | |

| NSC | 12.0% (11/92) | 150 | |

| Cervical | 69% (11/16) | 151 | |

| Breast | 8.7% (8/92) | 152, 153 | |

| Head and neck | 32.2% (52/161) | 146, 153, 154 | |

| Gastric | 36% (20/55) | 155 | |

| Thyroid | 9% (12/128) | 156 | |

| Esophageal | 6% (5/87) | 157 | |

| Cervical | 9% (2/22) | 158 | |

| Endometrial | 10% (3/29) | 158 | |

| Ovarian | 11.9% (16/134) | 159, 161 | |

| Glioblastoma | 6.1%(21/344) | 29, 160 | |

|

| |||

| p110b (PIK3CB) | |||

| Amplifications | Ovarian | 5% | 57 |

| Breast | 5% | 57 | |

| Increase in activity and expression | Colon | 70% (7/10) | 56 |

| Bladder | 89% (8/9) | 56 | |

|

| |||

| PDK1 | |||

| Amplification and overexpression | Breast | 20% | 57 |

|

| |||

| AKT | |||

| AKT1 mutation (E17K) | Breast | 3.7% (31/845) | 44, 58, 139, 140 |

| Colon | 2.8%(4/139) | 58, 139 | |

| Ovarian | 2% (1/50) | 58 | |

| Lung | 1.9% (2/105) | 141 | |

| AKT1 amplifications | Gastric | 20% (1/5) | 145 |

| AKT2 amplifications | Ovarian | 14.1%(30/213) | 142, 144, 151, 159 |

| Pancreas | 20% (7/35) | 143 | |

| Head and neck | 30% (12/40) | 146 | |

| Breast | 3% (3/106) | 142 | |

| AKT3 mutation (E17K) | Skin | 1.5% (2/137) | 59 |

| AKT3 amplifications | Glioblastoma | 2% (4/205) | 29 |

|

| |||

| p85a (PIK3R1) | |||

| Mutations | Glioblastoma | 9.9% (9/91); 8% (8/105) | 29, 30 |

| Ovarian | 4% (3/80); | 58 | |

| Colon | 2% (1/60); | 58 | |

|

| |||

| PTEN | |||

| Loss of heterozygosity | Gastric | 25.3% (84/332) | 155, 162, 163 |

| Breast | 24.9%(99/398) | 164-167 | |

| Melanoma | 37%(53/143) | 168-171 | |

| Prostate | 30%(70/230) | 172-176 | |

| Glioblastoma | 28% (113/404) | 29, 30, 177-179 | |

| Mutations | Endometrial | 38% (604/1569) | * |

| brain | 21%(611/2913) | *, 29, 30 | |

| skin | 17% (96/555) | * | |

| Prostate | 14% (51/371) | * | |

| large intestine | 13% (53/416) | * | |

| Ovary | 9% (55/645) | * | |

| Breast | 6% (34/561) | * | |

| Haematopoietic & lymphoid tissue | 6% (54/866) | * | |

| stomach | 6% (28/499) | * | |

| Liver | 5% (20/372) | * | |

| kidney | 5% (14/294) | * | |

| vulva | 65% (17/26) | * | |

| urinary tract | 9% (13/142) | * | |

| thyroid | 5% (27/591) | * | |

| Lung | 9% (48/548) | * | |

The values are taken from http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/.

Mutations of Class IA PI3Ks occur frequently in human tumors

The importance of PI3Ks in cancer was confirmed by the discovery that the PIK3CA gene encoding p110α is frequently mutated in some of the most common human tumors 29-32, 44 (TABLE 1). These genetic alterations of PIK3CA consist exclusively of somatic missense mutations clustered in two “hotspot” regions in exons 9 and 20, corresponding to the helical and kinase domains of p110α, respectively. Two of the most frequent PIK3CA mutations, E545K and H1047R, have been shown to enhance PI(3,4,5)P3 levels, activate AKT signaling, and induce cellular transformation 2, 45-48. While the exact molecular mechanism(s) by which these mutations activate p110α has not been determined, current data point to a model in which the negative inhibitory effect brought about by interaction of p110α with p85 is ablated 45, 49, 50. This notion was supported by two recent structural studies of the p110α/p85α complex 51, 52.

Recent cancer genomic analysis of human glioblastomas (GBM) showed that the PIK3R1gene, encoding the p85α regulatory subunit, was mutated in up to 10% of tumors analyzed, making it one of the most frequently altered GMB cancer genes 30, 31. Interestingly, while PIK3CA mutations were also found in ∼7% of GBMs in the same cohort, they were mutually exclusive with PIK3R1 mutations 30. The presence of somatic mutations in PIK3R1 was also previously reported in primary human colon and ovarian tumors and in one patient with GBM53, 54. Notably, most of these mutations are located within the iSH2 domain of p85α and are predicted to disrupt the inhibitory contact of p85α with p110, leading to constitutive PI3K activity 30, 53, 54. In contrast to PIK3CA, cancer-specific mutations have not been found in PIK3CB gene encoding p110β, even though several groups have demonstrated that it is capable of acting as an oncogene in model systems 2, 45. A recent study has shown that it may be more difficult to activate p110β than p110α by missense mutation 45, perhaps because p110β possesses much lower lipid kinase activity than p110α 55. However the PIK3CB gene, has been found to be amplified in some primary tumors and cancer cell lines56, 57.

AKT and PDK1 in human cancer

Amplification of AKT1/2 has been reported in various tumor types (TABLE 1). Recently, an activating mutation in the PH domain of AKT1 (E17K) was identified in melanoma, breast, colorectal and ovarian cancers44, 58, 59, which results in growth factor-independent membrane translocation of AKT and increased AKT phosphorylation levels 58, 59. Interestingly, the analogous mutation was also detected in AKT3 in clinical specimens of melanoma as well as in melanoma cell lines 59.

Unlike PI3K and AKT, there is only a single PDK1 isoform in mammals (reviewed in REF 60). While mutations in PDK1 are rarely found in human cancer (two cases in colorectal cancer and one in glioma have been reported thus far 61) amplification /overexpression of PDK1 was found in ∼20% of breast cancers 57.

Current nodes in the PI3K pathway being targeted in cancer

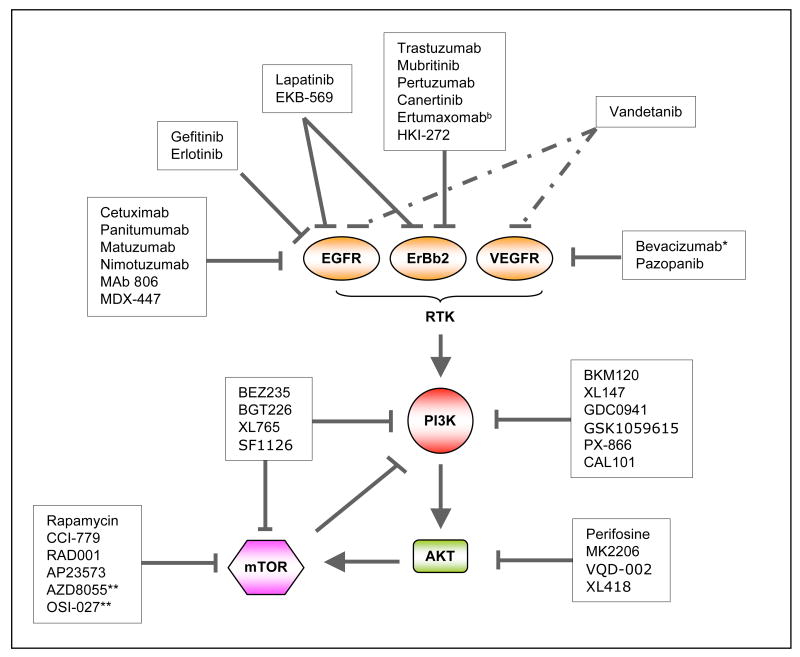

Activation of the PI3K signaling pathway contributes to cell proliferation, survival and motility as well as angiogenesis, which are responsible for all important aspects of tumorigenesis. For this reason many pharmaceutical companies and academic laboratories are actively developing inhibitors targeting PI3K and other key components in the pathway (FIG. 3a and b, TABLE 2).

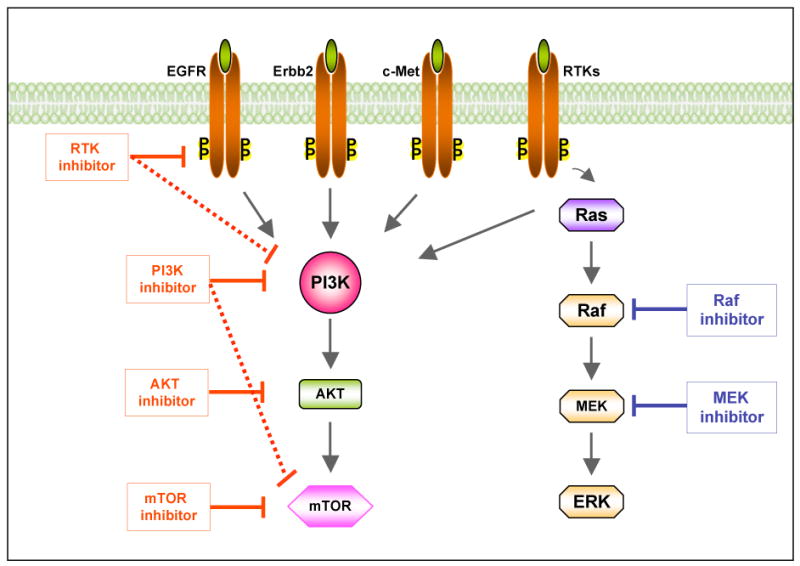

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway in cancer. Inhibitors targeting major nodes of the PI3K signaling pathway, including RTKs, PI3K, AKT and mTOR, have reached clinical trials. Dual inhibitors targeting both PI3K and RTK or PI3K and mTOR (as shown in connected solid and dashed lines) may provide more potent therapeutic effects in suppressing the PI3K signaling. Combinations of PI3K and Raf/MAPK inhibitors may achieve more effective clinical results. mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; Erbb2, Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2; c-Met, mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor Ras, a small GTPase protein, Raf, a serine/threonine kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase.

Figure 3b. Inhibitors in clinical development that target the PI3K or related pathways. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; Erbb2, Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin. *Bevacizumab targets VEGF-A instead of VEGFR directly. **Both AZD8055 and OSI027 are ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors that targets both mTORC1 and mTORC2.

Table 2. Summary of drugs targeting the PI3K pathway in clinical trials for cancer treatment*.

| Cateogory | Agent | Target | Sponsor | Phase | Cancer Type/Condition | Chemical structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

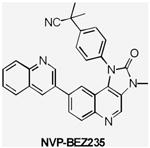

| PI3K Inhibitors | BEZ235 | Class I PI3K/mTOR | Novartis | Phase I/II | Advanced solid tumors Advanced Breast cancer |

|

|

| ||||||

| BGT226 | Class I PI3K/mTOR | Novartis | Phase I/II | Solid tumors Advanced breast cancer Cowden syndrome |

ND | |

|

| ||||||

| BKM120 | Class I PI3K | Novartis | Phase I (1st Qtr 2009) |

Solid tumors | ND | |

|

| ||||||

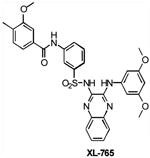

| XL765 | Class I PI3K/mTOR | Exelixis | Phase I | Solid tumors Non-Small Cell Lung Cance Malignant Gliomas |

|

|

|

| ||||||

| XL147 | Class I PI3K | Exelixis | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors Endometrial Carcinoma Ovarian Carcinoma Non-Small Cell Lung Cance |

|

|

|

| ||||||

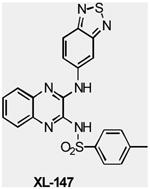

| GDC0941 | Class I PI3K | Genentech | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma |

|

|

|

| ||||||

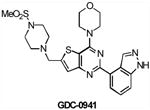

| SF1126 | pan-PI3K/mTOR | Semafore | Phase 1 | Advanced solid tumors |

|

|

|

| ||||||

| GSK1059615 | pan-PI3K | GlaxoSmithKline | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors Metastatic breast cancer Endometrial cancer Lymphoma |

ND | |

|

| ||||||

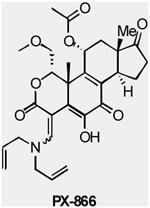

| PX-866 | PI3K (α, δ, and γ) | Oncothyreon | Phase 1 | Advanced solid tumors |

|

|

|

| ||||||

| CAL-101 | PI3K (δ) | Calistoga | Phase I | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma |

ND | |

|

| ||||||

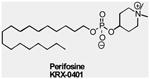

| Akt Inhibitors | Perifosine (KRX-0401) |

AKT | Keryx | Phase I/II | Advanced solid tumors Multiple myeloma Ovarian cancer Soft Tissue sarcoma Malignant melanoma |

|

|

| ||||||

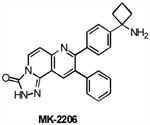

| MK2206 | AKT | Merck | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors |

|

|

|

| ||||||

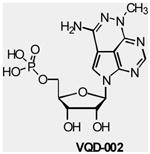

| VQD-002 (API-2/TCN) |

AKT | VioQuest | Phase I | Hematologic malignancies Leukemia Non-small cell lung cancer |

|

|

|

| ||||||

| XL418 | AKT/ S6K | Exelixis | Phase I** | Solid Tumors | ND | |

|

| ||||||

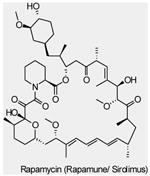

| mTOR Inhibitors | Rapamycin (Sirolimus, Rapamune®) |

mTORC1 | Wyeth | Phase I/II | Advanced solid tumors Metastatic breast cancer Myeloid leukemia |

|

|

| ||||||

| Approved | Advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) |

|

||||

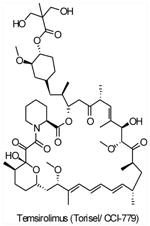

| CCI-779 (Temsirolimus,Torisel®) |

mTORC1 | Wyeth | Phase I/II/III | Advanced solid tumors Multiple myeloma Ovarian cancer Endometrial Cancer Mantle cell lymphoma Brain tumors Non-small cell lung cancer Malignant melanoma |

||

|

| ||||||

| Approved | Advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) |

|

||||

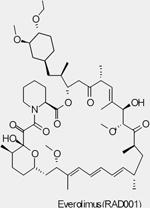

| RAD001 (Everolimus, Afinitor®) |

mTORC1 | Novartis | Phase I/II/III | Advanced solid tumors Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Bladder Cancer Head and Neck Cancer Glioma/Astrocytoma Advanced Prostate Cancer Brain tumors Advanced Gastric Cance Metastatic Breast Cancer Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer |

||

|

| ||||||

| Approved | Soft-tisse and bone sarcomas |

|

||||

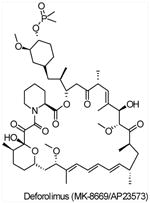

| AP23573 (Deforolimus,MK-8669) |

mTORC1 | Merck/Ariad | Phase I/II/III | Advanced malignancies Relapsed Hematologic Malignancies Progressive Glioma Endometrial Cancer Metastatic Breast Cancer Brain tumors Non-small cell lung cancer Prostate Cancer |

||

|

| ||||||

| AZD8055 | mTORC1/mTORC2 | AstraZeneca | Phase I/II | Advanced solid tumors Endometrial Carcinoma Lymphoma |

ND | |

|

| ||||||

| OSI-027 | mTORC1/mTORC2 | OSI | Phase I | Solid tumor Lymphoma |

ND | |

Information presented is compiled from company websites and from www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.fda.gov

The trial has been suspended due to low drug exposure.

ND, not disclosed

Targeting PI3K

Wortmannin and LY294002 are two well-known, first generation PI3K inhibitors. Wortmannin is a natural product isolated from Penicillium wortmannin that binds irreversibly to PI3K enzymes by covalent modification of a lysine necessary for catalytic activity. LY294002 (Lilly Research laboratories) was the first synthetic drug-like small molecule inhibitor capable of reversibly targeting PI3K family members at concentrations in the micromolar range. However, both wortmannin and LY294004 have little or no selectivity for individual PI3K isoforms and show considerable toxicity in animals (reviewed in REF 62, 63). Despite their limitations, the preclinical studies of these broad-spectrum PI3K inhibitors have greatly contributed to our understanding of the biological importance of PI3K signaling and provided a platform for the discovery of novel PI3K inhibitors.

A number of PI3K inhibitor chemotypes, some displaying differential isoform-selectivity, have been described64,63. A recent study by Knight et al 64 presented a parallel comparison of isoform-selectivity profiles among a collection of potent and structurally diverse PI3K inhibitors, which underlined a critical role of p110α insulin signaling and also provided important insights for the development of isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors. Subsequently, PI-103, a p110α-specific inhibitor, was shown to have a potent effect in blocking PI3K signaling in glioma cells via its ability to inhibit both PI3Kα and mTOR65. The seemingly off-target effects of PI-103 on mTOR complexes opened a new avenue in our search for an effective cancer therapy strategy relying on combinatorial inhibition of mTOR and PI3K.

At present, a number of PI3K-targeted compounds are being introduced into clinical trials (TABLE 2), many of which are dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors. BEZ235 (Norvatis) is an imidazaoquinazoline derivative that inhibits multiple class I PI3K isoforms and mTOR kinase activity by binding to the ATP-binding pocket66. Preclinical data show that BEZ235 possesses strong anti-proliferative activity against tumor xenografts featuring abnormal PI3K signaling including loss of PTEN function or gain of function PI3K mutations 67. BEZ235 has entered Phase I clinical trials in patients with solid tumors (reviewed in REF 68). BGT226 (Norvatis) is another potent pan-PI3K/mTOR inhibitor that has likewise entered Phase I. Distinguished from BEZ235 and BGT226, BKM120 (Norvatis) is selective for class I PI3K enzymes with no mTOR inhibitory activity that has just entered Phase I clinical trial. XL765 and XL147 are class I PI3K inhibitors from Exelixis (XL765 also targets mTOR), currently under Phase I clinical investigation for treatment of solid tumors. Both are derivatives of quinoxaline as revealed by their recently disclosed structures63. GDC0941 (Piramed/Gnenetech) is a derivative of PI-103 that is active against all isoforms of class I PI3Ks in a nanomolar range. It displayed potent antitumor activity in preclinical xenograft tumors and is under Phase I trail in patients with advanced solid tumors or lymphoma. GSK1059615 (GlaxoSmithKline), another clinical candidate targeting PI3K, has recently entered clinical trial in patients with solid tumors or lymphoma (TABLE 2).

SF1126 (Semafore) is a covalent conjugate of LY294002 with an RGD (arg-gly-asp) peptide designed for increased solubility and enhanced delivery of the active drug to the tumor 69. In preclinical studies, SF1126 has been shown to have potent inhibitory effects on cell growth, proliferation and angiogenesis with lowered toxicity compared to the parent LY294002. SF1126 has entered a Phase I clinical trial as a PI3K/mTOR inhibitor in a wide range of solid tumor cancers (TABLE 2).

A number of compounds that preferentially target selected isoforms of class I PI3Ks are also under development. For example, PX-866 (Oncothyreon) targets p110α, p110δ and p110γ with single-digit nanomolar IC50 values 70, while CAL-101 (Calistoga) is a p110 γ-selective inhibitor under Phase I clinic study in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies (TABLE 2).

Targeting AKT

As the most crucial proximal node downstream of the RTK/PI3K complex, AKT is another attractive therapeutic target. A large number of AKT inhibitors have been developed, which can be grouped into a number of classes including lipid-based phosphatidylinositol (PI) analogs, ATP competitive inhibitors, and allosteric inhibitors. The most clinically advanced inhibitor, Perifosine, is a lipid-based PI analog that targets the PH domain of AKT, thus preventing binding to PIP3 and hence its membrane translocation 71. It is currently in clinical trials as a single agent or in combination with various drugs to treat multiple types of cancers (TABLE 2). Other AKT PH domain inhibitors, including PX316 (Pro1X Pharmaceutical) 72 and PIAs (National Cancer Institute/Georgetown University, reviewed in REF 73), have shown inhibitory effects on the growth of tumor cells exhibiting high PI3K/AKT activity74.

Most ATP-competitive small molecules AKT inhibitors are non-selective, targeting all three AKT isoforms. GSK690693 (GlaxoSmithKline) is an ATP-competitive AKT kinase inhibitor, which targets all 3 AKT isoforms at low nanomolar range and is also active against additional kinases from the AGC kinase family75.

To address a major issue regarding the potential benefits of isoform specificity, a number of allosteric AKT inhibitors have recently been identified through screening of compound libraries and application of an iterative analog library synthesis. These allosteric AKT inhibitors have exhibited some level of isoform selectivity (reviewed in REF 76). AKTi-1/2 (Merck), a naphthyridinone allosteric dual inhibitor of AKT1 and AKT2, has shown potent antitumor activity in tumor xenograft models, and its analogue MK2206 (Merck) is in phase I trial in patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors (TABLE 2).

XL418 (Exelixis), a small molecule that inhibits the activity of AKT and S6K with antineoplastic activity in preclinical studies, is under Phase I clinical trails in patients with advanced solid tumors (TABLE 2). VQD-002 (triciribine phosphate monohydrate or TCN-P, VioQuest), a water-soluble tricyclic nucleotide is currently being tested in Phase I clinical trials in patients with both solid and hematologic malignancies (TABLE 2). It was recently reported that TCN-P could play a role in reversing drug resistance in ovarian cancer in patients previously treated with chemotherapy 77; however its mechanism of action is unclear.

Targeting mTOR

Though mTOR was only recently defined as a PI3K pathway member, it is the first node of the pathway targeted in the clinic. Rapamycin (also known as sirolimus, Rapamune®, Wyeth), the prototypic mTOR inhibitor, is a bacterially derived natural product originally used as an antifungal agent78and later found to have immunosuppressive79and, even more recently, antineoplastic properties (reviewed in REF 21,80,81,82). Rapamycin associates with its intracellular receptor, FK506-binding protein-12 (FKBP12), which then binds directly to mTORC1 and suppresses mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of its downstream substrates, S6K and 4EBP121,80. Analogues of rapamycin, such as CCI-779 (also known as temsirolimus, Torisel®, Wyeth), RAD001 (also known as everolimus, Afinitor®, Novartis) and AP23573 (also known as deforolimus, Merk/Ariad) have been developed as anti-cancer drugs. These rapamycin analogues, sometimes referred to as rapalogues, inhibit mTOR through the same mechanism as rapamycin, but have better pharmacological properties for clinical use in cancer. The results of many mTOR inhibitor studies in cancer patients have been described (reviewed in REF 80). AP23573 has been approved for the treatment of soft-tissue and bone sarcomas. Encouraging results from recent clinical studies with both CCI-779 and RAD001 used as single-agents showed that drugs targeting mTOR improved survival in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, leading to their clinical approval in that indication (RCC) 80, 83. However preliminary results with mTOR inhibitors in many other tumor types, including advanced breast cancer and glioma, yielded a low response rate 80.

Notably, mTOR also represents a potential second target via its mTORC2 complex that functions as a PDK2 responsible for phosphorylating the carboxyl terminus of AKT at ser473, an obligatory event necessary for full activation 18. While the clinical importance of PDK2 function in cancer is unknown, a recent study showed that mTORC2 is required for the development of prostate tumors induced by PTEN loss 84. Thus a kinase inhibitor of mTOR capable of targeting both mTORC1 and mTORC2 would be expected to block activation of the PI3K pathway more efficiently than rapamycin. Recent studies reported a few potent and selective ATP-competitive inhibitors of mTOR, TORKinibs and Torin1, that inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes and impair cell growth and proliferation more effectively than rapamycin85, 86. Interestingly, however, the enhanced activity of these mTOR kinase inhibitors may not be contributed by mTORC2 inhibition, and instead appears to be through more complete inhibition of mTORC1 activity as measured by mTORC1-dependent and rapamycin-independent 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and cap-dependent translation85, 86. Two ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors, OSI-027 (OSI Pharmaceuticals) and AZD8055 (AstraZeneca), are currently in clinical trials in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphoma (TABLE 2)

It is also worth noting that multiple kinases in the PI3K pathway are client proteins for the heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) 87,88. Thus compounds that inhibit Hsp90, such as Geldanamycin and its analogues, may have therapeutic effects at least in part through inhibition of the PI3K pathway (reviewed in REF 68, 89,90).

Ongoing issues and challenges

Unraveling the specific roles of PI3K isoforms may be important for drug development

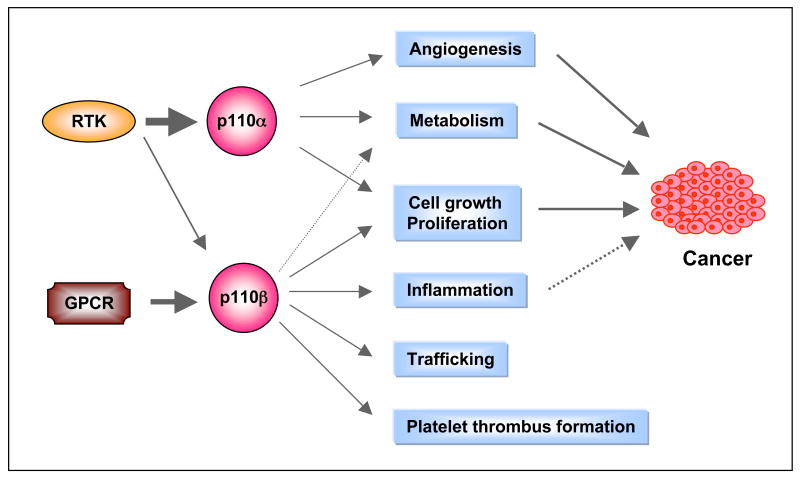

The two isoforms of class I PI3Ks most widely expressed outside of the immune system in mammals are p110α and p110β, both of which are expressed in almost all tissue and cell types. Since both isoforms need to form a complex with the p85 adaptor in order to bind to RTKs, utilize the same substrates and generate the same lipid products, it was long thought that they functioned redundantly in cellular physiology. However, over a decade ago, it was found that mice with homozygous germline deletion of either p110α or p110β die early during embryonic development 91, 92, suggesting distinct roles for each isoform during embryogenesis. More recently several groups have created mice with conditional knockout of p110α and p110β and mice with germline knockin of kinase-dead alleles of p110α or p110β 93-98 (TABLE 3). Studies with these mice have revealed that the two PI3K isoforms have markedly different roles in cellular signaling, growth, and oncogenic transformation (FIG. 4a). The p110α isoform performs most of the functions commonly assigned to PI3K in the literature. For instance, p110α is responsible for most of the signaling downstream from RTKs and oncogenes such as Ras and middle T antigen of polyoma virus 94, 99. Ablation of p110α resulted in significantly reduced AKT phosphorylation in response to stimulation by various growth factors including insulin, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)94. Cells deficient in p110α are resistant to oncogenic transformation induced by oncogenic alleles of RTKs94. Conversely, ablation of p110β has little effect on AKT phosphorylation in response to RTK signaling93. Instead, p110β, like p110γ, preferentially transduces signals from GPCRs via a mechanism yet to be elucidated 93, 95, 96. Since p110γ expression is largely limited to leukocytes, p110β with its broad tissue distribution may play an essential role in coupling GPCR signals to the PI3K pathway in cells or tissues outside of the immune system. In addition, p110β has been shown to play an important role in integrin mediated platelet adhesion and arterial thrombosis100. Interestingly, p110β also appears to possess significant kinase independent functions 93, 95.

Table 3. Gene-targeted mouse models of Class I PI3K.

| Class I PI3K | Genotype | Phenotypes | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p110 α | p110 α -/- | Embryonic lethality (E10.5) | 92 | ||

| p110 α D933A/D933A | Embryonic lethality (E10.5) E10-11; severe vascular abnormalities at E10.5 | 97, 98 | |||

| p110 α +/D933A | Defective in growth and metabolic regulation associated with hyperinsulinemia and glucose intolerance | 98 | |||

| p110 α RBD/RBD | Defective lymphatic development ; a small fraction survived into adult associated with proliferative defects and altered growth factor signaling to PI3K; protected from Kras-driven tumorigenesis in a lung cancer model | 126 | |||

| Endothelial p110 α -/- | Severe vascular abnormalities at E10.5 and died before E12.5 | 97 | |||

| Prostate p110 α -/- | Normal for prostate development; not protected from PTEN-loss induced high grade PIN | 93 | |||

| p110β | p110 β -/- | Embryonic lethality (E3.5) | 91 | ||

| p110 β K805R/K805R | Some survived to adult associated with retarded growth and mild insulin resistance with age; attenuated Erbb2-driven mammary tumor development | 95 | |||

| Liver p110 β -/- | Impaired insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis | 93 | |||

| Prostate p110 β -/- | Normal for prostate development; protected from PTEN-loss induced high grade PIN | 93 | |||

| p110δ | p110 | Viable; impaired B, NK cell development and functions; decreased immunoglobulin levels and defective humoral response; impaired neutrophil chemotaxis | 180-186 | ||

| p110 δ D910A/D910A | Viable; defective B, NK and mast cell development and function; impaired antigen receptor signaling in B and T cells, and attenuated immune and allergic response | 180-186 | |||

| p110γ |

p110

|

Viable; reduced insulin secretion; increased insulin sensitivity and β-cell mass; impaired mast cell functions and inflammatory response; reduced neutrophil and macrophage migration and oxidative burst; increased heart contractility | 10, 187-192 | ||

| p110 γ KD/KD | Viable; reduced inflammatory reactions with no alterations in cardiac contractility | 9 | |||

|

p110

|

Viable; severe defects in T and NK cell development and functions | 193-195 | |||

| p85 | p85 α -/- | Hypoglycemia and hypoinsulinemia and impaired B cell development and functions but normal T cell activation | 196, 197 | ||

| p55 α -/-p50 α -/- | Viable; enhanced insulin sensitivity | 198 | |||

| p85 α -/- p55 α -/-p50 α -/- | Perinatal death; liver necrosis and hypoglycemia; increased insulin sensitivity; impaired B cell development and functions | 199, 200 | |||

| p85 β -/- | Improved insulin sensitivity, increased T cell proliferation and accumulation in response to various stimuli | 201 | |||

|

Liver p85 α -/- p55 α -/-p50 α -/- p85 β -/- |

Defects in glucose and lipid homeostatis; hyperinsulinemia and hypolipidemia | 202 | |||

|

Muscle α -/- p55 α -/-p50 α -/- p85 β -/- |

Viable; reduced muscle growth, insulin response, and hyperlipidemia | 203 | |||

|

Endothelial p85 α -/- p55 α -/-p50 α -/- p85 β -/- |

Acute embryonic lethality at E11.5 due to hemorrhaging | 129 | |||

|

Endothelial p85 α +/- p55 α -/-p50 α -/- p85 β -/- |

Viable but with localized vascular abnormalities when challenged with pathlogical insults | 129 |

Figure 4.

Figure 4a. Differential functions of p110α and p110β isoforms. p110α is the major effector downstream of RTKs and p110β is an effector for both RTKs and GPCRs. Their differential roles in many biological functions are indicated. Many of these roles are associated with cancer (solid lines). An association between chronic inflammation and cancer has been indicated (dashed line). RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor.

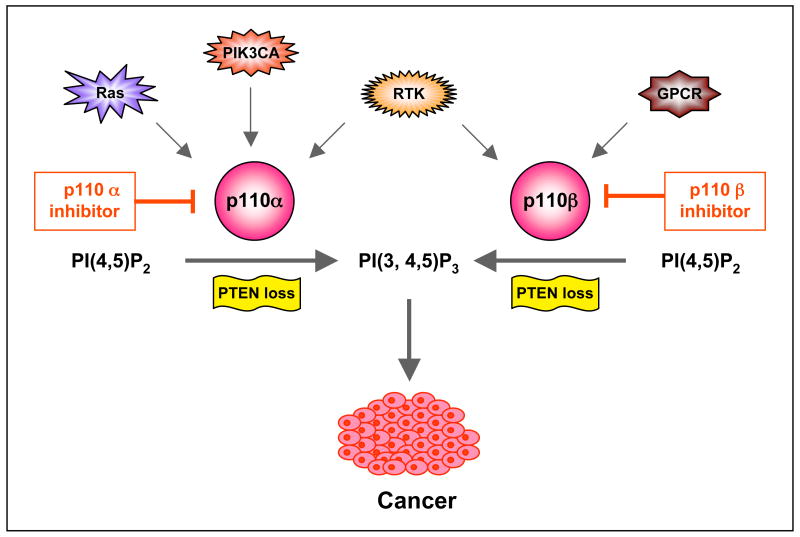

Figure 4b. Schematic of PI3K isoform-selective inhibition in the treatment of cancers featuring specific oncogenic lesions. Recent studies point to p110β as a primary target for PTEN-deficient cancers. However, in the case oncogenic lesions such as RTK amplification or mutation, Ras mutation, or activating PIK3CA mutations, the PI3K signaling largely depends on p110α, perhaps even in the absence of PTEN. RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue. PI(3,4,5)P3, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate; PI(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate.

There is considerable evidence that targeting a single isoform of PI3K (or other pathway members) may be sufficient to block a particular tumor type, suggesting the potential desirability of generating isoform specific inhibitors. By targeting single isoforms, potential drugs might avoid toxicity to the immune system, which is largely dependent on p110δ and p110γ for function. Similarly, since p110α and p110β seem to have distinct roles in multiple cellular processes (FIG.4a), it is possible that a drug aimed at either target would have fewer side effects than one that inhibits both. Since p110α is important for the growth and maintenance of a number of tumors featuring PI3K activation, several companies are already generating p110α isoform specific inhibitors (reviewed in REF 63, 68, 101). These compounds would be expected to bypass the problems of inhibiting p110γ and p110δ while targeting the PI3K pathway in many tumor types.

Interestingly, recent mouse genetic models and chemical inhibitors as well as limited shRNA experiments, suggest that tumors driven by PTEN loss may be sensitive to inhibition of p110β rather than p110α93, 102, 103. The exact mechanism by which p110β drives PTEN-null tumors has not been elucidated. Perhaps ligands such as LPA that work via GPCRs are driving PI3K activation in PTEN-null tumors, or perhaps PTEN loss allows a p110β–specific basal PIP3 synthesis mechanism to become the engine that drives tumor formation 93. It may be worthwhile considering the generation of p110β–selective compounds, especially, since p110β seems to play a smaller role in insulin action than p110α 93, 95. There are a few inhibitors, e.g. TGX-115, TGX-286 and TGX-221, which are selective for p110β relative to other PI3K enzymes except p110δ 64, 100. Among them, TGX-221 is perhaps the most commonly used p110β-selective tool compound to interrogate p110β functions. It was shown to be able to inhibit platelet aggregation and thrombosis 100, TGX-221 is also capable of suppressing the activation of PI3K and proliferation of PTEN-null cancer cells103. Further preclinical development of p110β-selective inhibitors is necessary to improve their pharmacological properties. However, there are reasons to believe that not all tumors driven by PTEN loss are dependent on p110β and the presence of other genetic alterations is likely to change the PI3K isoform dependence of these PTEN-null tumors (FIG. 4b). For instance, a number of tumor cell lines that feature loss of PTEN in conjunction with activating mutations in p110α are sensitive to loss of p110α not p110β103, 104.

Given the essential roles of p110α in cellular physiology, development of inhibitors specific for the mutant form of p110α found in tumors would be a particularly attractive route to therapy. Such inhibitors would presumably minimize side effects (i.e. alteration in insulin signaling) that will almost certainly be associated with inhibition of the wild-type p110α, especially during prolonged treatment. It remains a great challenge for researchers to identify mutant-specific small-molecule inhibitors targeting the catalytic center of the mutant but not wild-type kinase. The structure of a complex between wild-type p110α and the iSH2 domain of p85 has been recently reported 52. It reveals many features in common with well-characterized protein kinases, including a hydrophobic ATP-binding pocket. Most small-molecule inhibitors targeting PI3K lipid kinases in current development, like most protein kinase inhibitors, work by binding to the ATP pocket and thus competing with ATP. The structure of wild-type p110α suggests that the H1047R mutation in the kinase domain most likely improves substrate binding through a direct effect on the conformation of the activation loop. Given the proximity of the activation loop to the ATP binding pocket, a kinase domain mutant specific inhibitor might be feasible using existing drug scaffolds. It may be much more difficult to target the mutated helical domain of the kinase (E542K or E545), as these mutations appear to affect protein-protein interaction by eliminating an auto-inhibitory contact with the p85 iSH2 domain 51.

Feedback loops and pathway crosstalk can alter signaling circuitry, thereby changing therapeutic outcomes

A hallmark of signaling networks is the presence of multiple nodes with feedback loops and crosstalk between pathways. Two negative feedback loops have been described, involving S6K and JNK (Jun N-terminal kinase), which attenuate insulin induced PI3K activation via IRS 105-107. S6K- or JNK-knockout mice show increased insulin sensitivity in response to high-fat diets 108, 109. Perturbing these feedback loops can have dramatic effects on drug responses, as exemplified by the response of certain tumors to rapalogues. When mTOR is activated, it can initiate a signaling cascade via S6K1 that results in a feedback loop that downregulates PI3K/AKT activity. Thus, when tumors in which this loop is activated are treated with rapalogues, the net effect can be elevated AKT activity that can, in turn, ultimately enhance tumor growth 110. PI3K or AKT inhibitors should not be affected by this problem, but may suffer from issues arising from crosstalk with other pathways. Specifically, for cancers bearing mutant RTKs, or oncogenes such as Ras that activate both the Raf-MAPK and PI3K pathways, blocking the PI3K pathway can actually upregulate signaling of the Raf-MAPK pathway, since the two pathways have cross-inhibitory effects 111. Raf-MAPK pathway signaling can, in turn, drive tumor growth, defeating the effect of the PI3K pathway inhibition. Pandolfi and colleagues recently showed that mTORC1 inhibition led to the activation of MAPK in a PI3K-dependent manner, providing another example for such signaling feedback loop and crosstalk 112. As will be discussed below, combined inhibition of both pathways for therapy may possibly alleviate this problem.

Identifying biomarkers that predict drug responses

For PI3K pathway inhibitors, as with all targeted therapies, it is crucial to develop clinically tractable biomarkers predictive of drug response. Biomarkers can be divided into two categories: those that indicate drugs are reaching intended targets in the PI3K pathway, and those that can predict patients likely to respond. Readily obtainable tissues, such as skin, hair follicles and peripheral blood mononuclear (PBMCs), have been used as surrogate tissues to assess the effect of PI3K inhibitors currently undergoing clinical trials 113. The molecular markers of PI3K inhibition commonly used in the clinic are phospho-AKT and phospho-S6K1 levels in biopsies of these surrogate tissues and when possible, tumor tissue. However, there is great variability in the robustness and reproducibility of biomarkers in monitoring the efficacy of PI3K pathway inhibitors. Thus, identification of new and potentially more robust biomarkers is a critically important part of the preclinical development of PI3K inhibitors and in the conduct and interpretation of clinical studies using these inhibitors.

Preclinical studies have indicated that PI3K/AKT inhibition may be assessed by measuring blood insulin levels, which are increased due to disruption of insulin signaling through the PI3K/AKT pathway 64, 98, 114, 115. Studies in mice featuring genetic inactivation of PI3Ks or AKT 93, 95, 98, 114 also suggested that changes in blood glucose levels in response to PI3K inhibition may be exploited clinically, but early clinical results suggest that these effects may be transient and difficult to measure. Since the PI3K pathway plays a major role in insulin-mediated glucose transport and metabolism, inhibition of the PI3K pathway in tumors can be measured by scanning positron emission tomography (PET) using fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) as a probe (FDG-PET scan). A recent study demonstrated that the effect of BEZ235 on the reduction of tumor vasculature permeability could be monitored by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI)116. These types of molecular imaging offer a minimally invasive approach to determine the efficacy of targeted PI3K inhibition 117, and may possibly be predictive of clinical outcome.

Sensitivity and resistance to PI3K targeted therapies

One of the key lessons drawn from targeted therapies has been the importance of matching the therapy to the patient. Perhaps the best predictor of potential success for a kinase inhibitor has been the presence of an activating mutation or other genomic alteration in the targeted kinase. Examples include the use of imatinib (Gleveec®; Novartis) for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) patients with BCR-ABL fusions, trastuzumab (Herceptin®; Genentech) and lapatinib (Tyverb®; GlaxoSmithKline) with Her2 positive breast tumors, and gefitinib (Iressa®, AstraZeneca) and erlotinib (Tarceva®; Genentech) for lung cancer patients with mutations and/or amplification of EGFR. This logic suggests that PI3K inhibitors will be effective in tumors featuring activating mutations in p110α or loss of PTEN, while AKT mutations would be expected to sensitize a tumor to AKT inhibitors. It also seems likely that targeting a pathway just downstream from the genetic lesion will be effective. Thus, PI3K and AKT inhibitors may be useful for the treatment of tumors featuring activated RTKs or oncogenic ras (perhaps in combination with Raf/MAPK inhibitors). Finally, mTOR inhibitors and inhibitors of kinases further downstream in the pathway may likewise be effective in tumors featuring PI3K activation. However it is not clear as to how distant a mutation may be from the targeted node in the pathway and it still be sensitive to the inhibition.

Since most tumors are genetically complex, it is likely that mutations/alterations in genes other than PI3K will predispose a tumor to be sensitive or, even more likely, resistant to PI3K-targeted therapy. An obvious source of resistance is a mutation or amplification of a downstream pathway component. Just as mutations of p110α or loss of PTEN can render Her2 positive tumors resistant to trastuzumab 118, 119, it is likely that tumors with amplifications or mutations in various downstream kinases will block the action of inhibitors targeted against their upstream components. It is thus important to select patients likely to respond to PI3K-targeted cancer therapy and identify non-responder patients.

Notably, these resistance events can be either primary or acquired during therapy. For instance, so called “gatekeeper” mutations may occur after targeted protein kinase therapy (reviewed in REF 120). These mutations occur at a residue in the kinase domain of the targeted kinase and block binding of the inhibitor while allowing catalysis to proceed. Shokat and colleagues have used a functional screen against a structurally diverse panel of PI3K inhibitors and identified a potential hotspot for resistance mutations in p110α, but surprisingly found a lack of resistance mutations at the “gatekeeper” residues121. Other known resistance mechanisms include the activation of alternative pathways, such as the induced gefitinib resistance via reactivation of HER3 signaling in lung cancer as a result of incomplete HER2 inhibition or amplification of MET 122-124. A comparable mechanism in the case of PI3K inhibitors would be the activation of the Raf-MAPK pathway mentioned earlier. Current preclinical research and clinical studies will undoubtedly reveal more resistance mechanisms and facilitate the development of therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance.

Emerging candidates/approaches

The wisdom of simultaneously targeting two kinases in the pathway

A number of the early PI3K inhibitor clinical candidates are dual-specificity drugs, targeting not only multiple PI3K isoforms but also the kinase activity of mTOR (TABLE 2). Generation of this class of compounds was relatively easy since mTOR is in the PI3K superfamily and hence bears considerable structural similarity to class I PI3Ks. A strong argument can be made that by targeting two nodal points in the pathway concurrently, a compound may be more efficacious than if it has only a single target (FIG 3a and b). For example, PI-103 (Piramed) was found to be a potent inhibitor of both PI3K and mTOR and demonstrated an unexpectedly high ability to block the growth of aggressive glioma cells in vivo as well as in vitro 65. A second class of inhibitors that selectively target both particular tyrosine kinases and PI3Ks have been reported by Knight and colleagues 125. A single agent with dual specificity may have the added advantage in being less likely to induce drug resistance. Clinical resistance to a kinase inhibitor has often come via second-site mutations within the targeted kinase. With two kinases targeted simultaneously, there is a greatly diminished possibility that a given tumor can generate two resistant kinases during the course of a single drug treatment. Of course this argument assumes that both kinases being essential for tumor survival and/or growth.

The combination of PI3K pathway inhibitors with drugs targeting other pathways

While knockout of PI3K isoforms can block oncogenic transformation driven by various activated RTKs and oncogenes 94,93, targeting PI3K may not be sufficient to regress established tumors. For instance, mice in which p110α was mutated to ablate its binding to Ras are resistant to lung tumor development driven by activated K-ras 126. However, the same K-ras lung tumor model has been found to be insensitive to PI3K inhibition by BEZ235 once the tumors have formed. In this case, a combination of PI3K and Raf pathway inhibition by BEZ235 plus a MEK1/2 inhibitor (ARRY142886, also known as ADZ6244; AstraZeneca), effectively induced tumor regression 127. Consistently, activation of the MEK effector pathway downstream of Ras was found to be responsible for resistance to PI3K inhibitors in tumor cell lines harboring Ras mutations, and therefore the combination of MEK inhibitors and PI3K inhibitors synergistically blocked growth of tumor cells expressing oncogenic Ras 102,128. Recent comprehensive cancer genomic studies reveal that tumors with PI3K mutations or PTEN loss often harbor other genetic lesion(s) that can act independently to promote tumor development (reviewed in REF 129). The presence of these or other genetic alterations is likely to change the sensitivity of tumors to PI3K inhibition. Thus, combinations of PI3K inhibitors with other targeted drugs may achieve optimal clinical benefits (FIG. 3a).

Angiogenesis as a specific target of the PI3K pathway

Interestingly, inhibition of the PI3K pathway may attack tumors by two distinct directions, (a) by blocking tumor cell growth directly and (b) by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis. It is notable that the PI3K pathway plays an important role in the production of the key endothelial cell growth factor, VEGF, and in the signaling of the VEGF receptor. Rapamycin and its analogues have been studied most extensively in the clinic as anti-angiogenic agents. Rapamycin was found to have anti-angiogenic activities associated with markedly reduced production of VEGF, and it completely abrogated the response of vascular endothelial cells to stimulation by VEGF 130. When used at relatively low (minimally immunosuppressive) doses, Rapamycin significantly inhibits the growth of established vascularized tumors 130. This work suggested that Rapamycin might affect tumor growth primarily through its anti-angiogenic properties, leading to the hypothesis that it might be particularly effective in treating highly vascularized tumors. Indeed, Rapamycin significantly inhibits the progression of Kaposi's sarcoma where the driving oncogenic lesion is presumed to be activated VEGF/VEGFR signaling131. In renal cell carcinoma, loss of the VHL (von Hippel-Lindau syndrome) gene that normally inhibits HIF1A (hypoxia-induced factor 1, α subunit) leads to enhanced vascularization, and sensitizes cancer cells to the mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 132. From a mechanistic perspective, Rapamycin inhibits mTORC1-dependent translation and action of HIF1A and thus decreases VEGF production 133,134.

Preclinical data in tissue culture and mouse models suggests that an anti-angiogenic effect may well be part of the anti-tumor effects of inhibiting PI3K or AKT 97, 116, 129, 135, 136. Cantley and colleagues have recently shown that genetic ablation of class IA PI3K, specifically in the endothelium, resulted in impaired vessel integrity during development as well as tumor angiogenesis 129. Vanhaesebroeck's group further demonstrated that angiogenesis selectively requires p110α isoform, as it is critical in mediating VEGF signaling and controlling endothelial cell migration 97. Indeed, a particular blockage of tumor vasculature in xenograft tumor models by BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, was correlated with inhibition of PI3K/AKT, but not of mTORC1 116,129. It is quite possible that PI3K or AKT inhibitors may be as effective as rapamycin analogues in the treatment of highly vascularized tumors.

Conclusions and future directions

The PI3K pathway clearly presents both a great therapeutic opportunity and a tremendous challenge for cancer therapy. As compounds targeting PI3K (or AKT and mTOR) travel through various stages of clinical trials, potential issues associated with toxicity and resistance can be expected. PI3K mutants resistant to a kinase inhibitor may arise during treatment, analogously to what has been seen for BCR-ABL inhibition by imatinib in the treatment of CML. Oncogenic changes in other components in the PI3K pathway, or other parallel and/or interconnected pathways, may likewise render cancer cells resistant to PI3K inhibition. Thus it is important to identify new therapeutic targets for the development of drugs that may either be used in place of PI3K inhibitors, or may be used to enhance the efficacy of PI3K inhibitors at subtoxic doses.

Lastly, it is worth noting that reduced expression of PDK1 137, AKT1 138 or p110α (TMR and JJZ unpublished) can suppress tumor formation in animal models. This suggests that it might be possible to use low levels of inhibitors of these enzymes to block tumorigenesis in certain instances. Thus familial diseases such as Cowden disease with germline loss of PTEN might be treated in this manner. Clearly, for chemoprevention to work, it would be optimal to have the inhibitors present prior to tumor initiation. Similarly, it is possible that a chemopreventitive approach might work to block outgrowth of cells that have metastasized to distant sites after successful treatment of a primary tumor. Further experimentation will be required to determine if doses can be found that are sufficient to block tumor outgrowth but engender only minimal side effects during long-term therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Nathanael Gray and Qingsong Liu for providing compound structures and helpful discussions. We apologize to colleagues whose primary papers were not cited due to space constraints. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (CA030002, CA089021 and CA050661 to T.M.R. and CA134502-01 to J.J.Z), the Department of Defense for Cancer Research (BC051565 to J.J.Z.), the V Foundation (J.J.Z.) and the Claudia Barr Program (J.J.Z.). In compliance with Harvard Medical School guidelines, we disclose the consulting relationships: Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (T.M.R. and J.J.Z.).

References

- 1.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–19. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader AG, Kang S, Zhao L, Vogt PK. Oncogenic PI3K deregulates transcription and translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:921–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantley LC, Neel BG. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4240–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cully M, You H, Levine AJ, Mak TW. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:184–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fruman DA, Meyers RE, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:481–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katso R, et al. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:615–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voigt P, Dorner MB, Schaefer M. Characterization of p87PIKAP, a novel regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma that is highly expressed in heart and interacts with PDE3B. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9977–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suire S, et al. p84, a new Gbetagamma-activated regulatory subunit of the type IB phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110gamma. Curr Biol. 2005;15:566–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JD, et al. Deletion of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110gamma gene attenuates murine atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702663104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrucco E, et al. PI3Kgamma modulates the cardiac response to chronic pressure overload by distinct kinase-dependent and -independent effects. Cell. 2004;118:375–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasaki T, et al. Function of PI3Kgamma in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science. 2000;287:1040–6. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backer JM. The regulation and function of Class III PI3Ks: novel roles for Vps34. Biochem J. 2008;410:1–17. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheid MP, Woodgett JR. PKB/AKT: functional insights from genetic models. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:760–8. doi: 10.1038/35096067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alessi DR, et al. 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1): structural and functional homology with the Drosophila DSTPK61 kinase. Curr Biol. 1997;7:776–89. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens L, et al. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science. 1998;279:710–4. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:729–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–57. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10:151–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vander Haar E, Lee SI, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ, Kim DH. Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:316–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao JJ, Roberts TM. PI3 kinases in cancer: from oncogene artifact to leading cancer target. Sci STKE 2006. 2006:pe52. doi: 10.1126/stke.3652006pe52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood LD, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–13. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas RK, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:347–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons DW, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuels Y, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding L, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sansal I, Sellers WR. The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2954–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steck PA, et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15:356–62. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parsons R. Human cancer, PTEN and the PI-3 kinase pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knobbe CB, Lapin V, Suzuki A, Mak TW. The roles of PTEN in development, physiology and tumorigenesis in mouse models: a tissue-by-tissue survey. Oncogene. 2008;27:5398–415. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Cristofano A, De Acetis M, Koff A, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten and p27KIP1 cooperate in prostate cancer tumor suppression in the mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:222–4. doi: 10.1038/84879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet. 1998;19:348–55. doi: 10.1038/1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–21. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stambolic V, et al. High incidence of breast and endometrial neoplasia resembling human Cowden syndrome in pten+/- mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3605–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stemke-Hale K, et al. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6084–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao JJ, et al. The oncogenic properties of mutant p110alpha and p110beta phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in human mammary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18443–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508988102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isakoff SJ, et al. Breast cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations are oncogenic in mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10992–1000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samuels Y, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bader AG, Kang S, Vogt PK. Cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA are oncogenic in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1475–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510857103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JY, Engelman JA, Cantley LC. Biochemistry. PI3K charges ahead. Science. 2007;317:206–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1146073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang CH, Mandelker D, Gabelli SB, Amzel LM. Insights into the oncogenic effects of PIK3CA mutations from the structure of p110alpha/p85alpha. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1151–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miled N, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317:239–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang CH, et al. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318:1744–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizoguchi M, Nutt CL, Mohapatra G, Louis DN. Genetic alterations of phosphoinositide 3-kinase subunit genes in human glioblastomas. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:372–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Philp AJ, et al. The phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase p85alpha gene is an oncogene in human ovarian and colon tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7426–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beeton CA, Chance EM, Foukas LC, Shepherd PR. Comparison of the kinetic properties of the lipid- and protein-kinase activities of the p110alpha and p110beta catalytic subunits of class-Ia phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 2):353–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benistant C, Chapuis H, Roche S. A specific function for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase alpha (p85alpha-p110alpha) in cell survival and for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta (p85alpha-p110beta) in de novo DNA synthesis of human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:5083–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brugge J, Hung MC, Mills GB. A new mutational AKTivation in the PI3K pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:104–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carpten JD, et al. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–44. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davies MA, et al. A novel AKT3 mutation in melanoma tumours and cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1265–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vanhaesebroeck B, Alessi DR. The PI3K-PDK1 connection: more than just a road to PKB. Biochem J. 2000;346(Pt 3):561–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hunter C, et al. A hypermutation phenotype and somatic MSH6 mutations in recurrent human malignant gliomas after alkylator chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3987–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knight ZA, Shokat KM. Chemically targeting the PI3K family. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:245–9. doi: 10.1042/BST0350245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marone R, Cmiljanovic V, Giese B, Wymann MP. Targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinase: moving towards therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:159–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Knight ZA, et al. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell. 2006;125:733–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fan QW, et al. A dual PI3 kinase/mTOR inhibitor reveals emergent efficacy in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maira SM, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1851–63. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Serra V, et al. NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, prevents PI3K signaling and inhibits the growth of cancer cells with activating PI3K mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8022–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garcia-Echeverria C, Sellers WR. Drug discovery approaches targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5511–26. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garlich JR, et al. A vascular targeted pan phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor prodrug, SF1126, with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:206–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ihle NT, et al. The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibitor PX-866 overcomes resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinib in A-549 human non-small cell lung cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1349–57. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hilgard P, et al. D-21266, a new heterocyclic alkylphospholipid with antitumour activity. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:442–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)89020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meuillet EJ, et al. In vivo molecular pharmacology and antitumor activity of the targeted Akt inhibitor PX-316. Oncol Res. 2004;14:513–27. doi: 10.3727/0965040042380487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gills JJ, Dennis PA. The development of phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues as inhibitors of the serine/threonine kinase, Akt. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:787–97. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.7.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gills JJ, et al. Spectrum of activity and molecular correlates of response to phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues, novel lipid-based inhibitors of Akt. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:713–22. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]