Abstract

Many stem, progenitor and cancer cells undergo periods of mitotic quiescence from which they can be reactivated1-5. The signals triggering entry into and exit from this reversible dormant state are not well understood. In the developing Drosophila central nervous system (CNS), multipotent self-renewing progenitors called neuroblasts6-9 undergo quiescence in a stereotypical spatiotemporal pattern10. Entry into quiescence is regulated by Hox proteins and an internal neuroblast timer11-13. Exit from quiescence (reactivation) is subject to a nutritional checkpoint requiring dietary amino acids14. Organ co-cultures also implicate an unidentified signal from an adipose/hepatic-like tissue called fat body14. Here, we provide in vivo evidence that Slimfast amino-acid sensing and Target-of-Rapamycin (TOR) signalling15 activate a fat-body derived signal (FDS) required for neuroblast reactivation. Downstream of the FDS, Insulin-like receptor (InR) signalling and the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)/TOR network are required in neuroblasts for exit from quiescence. We demonstrate that nutritionally regulated glial cells provide the source of Insulin-like Peptides (Ilps) relevant for timely neuroblast reactivation but not for overall larval growth. Conversely, Ilps secreted into the hemolymph by median neurosecretory cells (mNSCs) systemically control organismal size16-18 but do not reactivate neuroblasts. Drosophila thus contains two segregated Ilp pools, one regulating proliferation within the CNS and the other controlling tissue growth systemically. Together, our findings support a model in which amino acids trigger the cell cycle re-entry of neural progenitors via a fat body→glia→neuroblasts relay. This mechanism highlights that dietary nutrients and remote organs, as well as local niches, are key regulators of transitions in stem-cell behaviour.

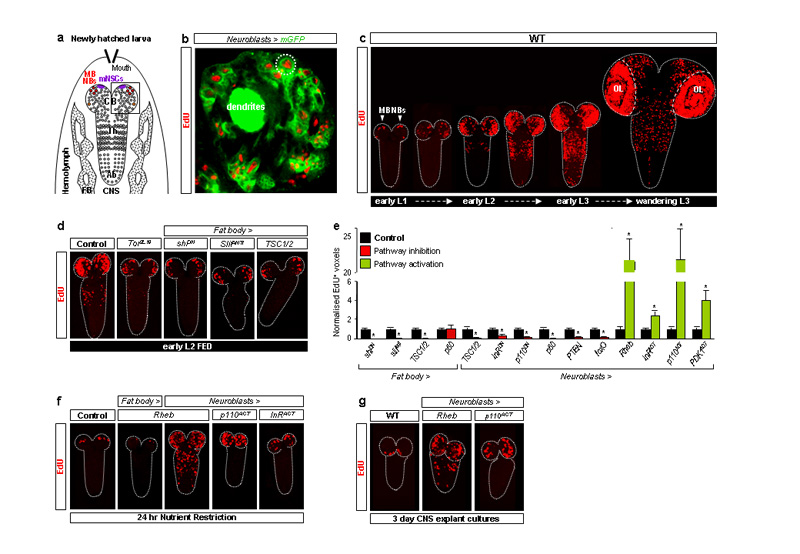

In fed larvae, Drosophila neuroblasts (Fig. 1a) exit quiescence from the late first instar (L1) stage onwards. This reactivation involves cell enlargement and entry into S-phase, monitored in this study using the thymidine analogue, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU). Consistent with a previous study10, we observed that reactivated neuroblast lineages (neuroblasts and their progeny, Fig 1b) reproducibly incorporated EdU in a characteristic spatiotemporal sequence: central brain (CB) → thoracic (Th) → abdominal (Ab) neuromeres (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Mushroom-body neuroblasts (MB NBs) and one ventrolateral neuroblast, however, are known not to undergo quiescence and to continue dividing for several days in the absence of dietary amino acids14 (Fig. 1a,c,f). This indicates that dietary amino acids are more than mere “fuel”, providing a specific signal that reactivates neuroblasts. However, explanted CNSs incubated with amino acids do not undergo neuroblast reactivation unless co-cultured with fat body from larvae raised on a diet containing amino acids14. We therefore tested the in vivo requirement for a fat-body derived signal (FDS) in neuroblast reactivation by blocking vesicular trafficking and thus signalling from this organ using a dominant-negative Shibire Dynamin (ShiDN). This strongly reduced EdU neuroblast incorporation, indicating that exit from quiescence in vivo requires a FDS (Fig. 1d,e). One candidate we tested was Ilp6, known to be expressed by the fat body19, 20, but neither fat-body specific overexpression nor RNA interference of this gene significantly affected neuroblast reactivation (Supplementary Table 1 and data not shown). Fat body cells are known to sense amino acids via the cationic amino-acid transporter Slimfast (Slif), which activates the TOR signalling pathway, in turn leading to the production of a systemic growth signal15, 21. We found that fat-body specific overexpression of the TOR activator, Ras Homologue Enriched in Brain (Rheb) or of an activated form of the p110 PI3K catalytic subunit, or of the p60 adaptor subunit, had no significant effect on neuroblast reactivation in fed animals or in larvae raised on a nutrient-restricted (NR) diet lacking amino-acids (Fig. 1e,f and data not shown). In contrast, global inactivation of Tor, fat-body specific Slif knockdown or fat-body specific expression of the TOR inhibitors Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 and 2 (TSC1/2) all strongly reduced neuroblasts from exiting quiescence (Fig. 1d,e). These results together show that a Slif/TOR-dependent FDS is required for neuroblasts to exit quiescence and that this may be equivalent to the FDS known to regulate larval growth.

Fig. 1. TOR/PI3K signalling in fat body and neuroblasts regulates reactivation.

a, Diagram depicting larval fat body (FB) and CNS with central brain (CB), thoracic (Th) and abdominal (Ab) neuromeres, mNSCs, mushroom body (MB NBs) and other neuroblasts (circles) indicated. b, Brain lobe (inset in Fig.1a), showing EdU incorporation in postembryonic neuroblasts (large cells; e.g dotted circle) and their progeny (smaller cells), labelled with nab-GAL4 driving membrane GFP (Neuroblasts>mGFP). c, EdU incorporation timecourse from first-instar (L1) to third-instar (L3) larval stages in the wild-type (WT) CNS (OL, optic lobes). d,f,g, EdU-labelled CNSs from larvae expressing TOR/PI3K components driven by Cg-GAL4 (Fat body>) or nab-GAL4 (Neuroblasts>). e, Histograms of EdU+ voxels from thoracic CNSs of fed larvae, normalized to controls. In this and all subsequent figures, error bars are s.e.m.; * p<0.05. See text, Methods and Supplementary Fig. 2 for details of molecules expressed.

We next investigated the signalling pathways essential within neuroblasts for their reactivation. Nutrient-dependent growth is regulated in many species by the interconnected TOR and PI3K pathways22-24 (Supplementary Fig. 2). In fed larvae, we found that neuroblast inactivation of TOR signalling (by overexpression of TSC1/2), or PI3K signalling (by overexpression of p60, the Phosphatase and Tensin homologue PTEN, the Forkhead box subgroup O transcription factor FoxO or dominant-negative p110), all inhibited reactivation (Fig. 1e). Conversely, stimulation of neuroblast TOR signalling (by overexpression of Rheb) or PI3K signalling (by overexpression of activated p110 or Phosphoinositide-Dependent Kinase 1, PDK1) triggered precocious exit from quiescence (Fig. 1e). Rheb overexpression had a particularly early effect, preventing some neuroblasts from undergoing quiescence even in newly hatched larvae (Supplementary Fig. 3). Hence, TOR/PI3K signalling in neuroblasts is required to trigger their timely exit from quiescence. Importantly, neuroblast overexpression of Rheb or activated p110 in NR larvae, which lack FDS activity14, was sufficient to bypass the NR block to neuroblast reactivation (Fig. 1f). Strikingly, both genetic manipulations were even sufficient to reactivate neuroblasts in explanted CNSs, cultured without fat body or any other tissue (Fig. 1g). Together with the previous results, this indicates that neuroblast TOR/PI3K signalling lies downstream of the amino-acid dependent FDS during exit from quiescence.

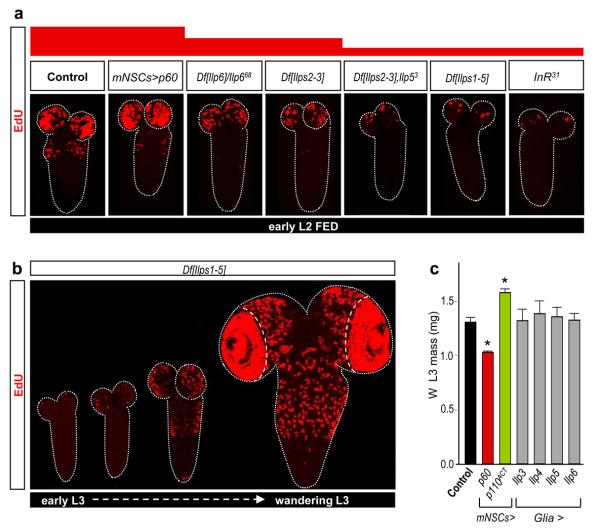

To identify the mechanism bridging the FDS with neuroblast TOR/PI3K signalling, we tested the role of the Insulin-like Receptor (InR, Supplementary Fig. 2). Importantly, a dominant-negative InR inhibited neuroblast reactivation whereas an activated form stimulated premature exit from quiescence (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, InR activation was sufficient to bypass the NR block to neuroblast reactivation (Fig. 1f). This suggests that at least one of the potential InR ligands, the seven Insulin-like peptides (Ilps), may be the neuroblast reactivating signal(s). By testing various combinations of targeted Ilp null alleles25 and genomic Ilp deficiencies25, 26, we found that neuroblast reactivation was moderately delayed in larvae deficient for both Ilp2 and Ilp3 (Df[Ilps2-3]) or lacking Ilp6 activity (Fig. 2a). Stronger delays, as severe as those observed in InR31 mutants, were observed in larvae simultaneously lacking the activities of Ilp2, Ilp3 and Ilp5 (Df[Ilps2-3],Ilp5) or Ilps1-5 (Df[Ilps1-5]) (Fig. 2a). Despite the developmental delay in Df[Ilps1-5] animals25, 26, neuroblast reactivation eventually begins in the normal spatial pattern albeit heterochronically, in larvae with L3 morphology (Fig. 2b, compare timeline with Fig. 1c). Together, the genetic analysis shows that Ilps 2, 3, 5 and 6 regulate the timing but not the spatial pattern of neuroblast exit from quiescence. However, as removal of some Ilps can induce compensatory regulation of others25, the relative importance of each cannot be assessed from loss-of-function studies alone.

Fig. 2. Insulin-like peptides but not mNSCs control neuroblast reactivation.

a, EdU-labelled CNSs from various Ilp or InR mutants show decreased reactivation whereas larvae with Ilp2-GAL4 driving UAS-p60 (mNSC>p60) do not. b, EdU incorporation timecourse in the CNS of Df[Ilps1-5] larvae. c, The mass of fed L3 larvae at the wandering (W) stage is significantly altered by Ilp2-GAL4 (mNSC>) driving PI3K signalling components but not by repo-GAL4 (Glia>) driving Ilps.

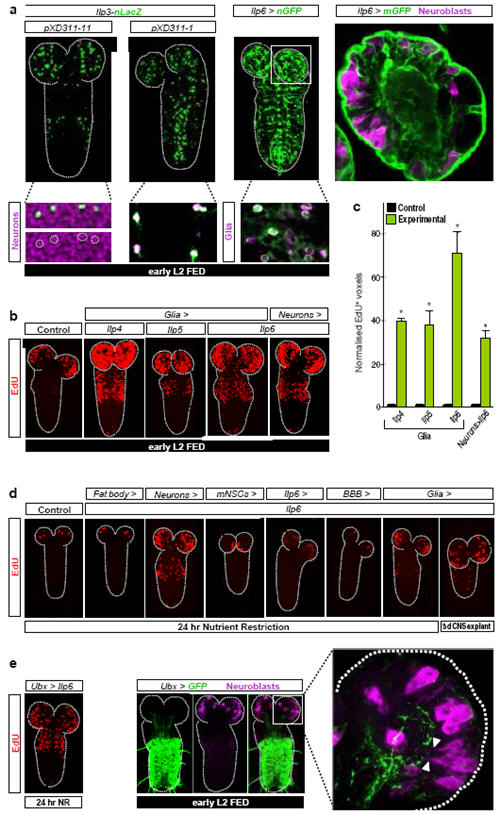

Brain mNSCs (Fig. 1a) are an important source of Ilps, secreted into the hemolymph in an FDS-dependent manner to regulate larval growth16-18, 21. They express Ilp1, Ilp2, Ilp3 and Ilp5, although not all during the same development stages16-18. However, we found that none of the seven Ilps could reactivate neuroblasts during NR when overexpressed in mNSCs (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, increasing mNSC secretion using the NaChBac sodium channel21 or altering mNSC size using PI3K inhibitors/activators, which in turn alters body growth, did not significantly affect neuroblast reactivation under fed conditions (Fig. 2a,c, Supplementary Fig. 1b and L. Cheng, A. Bailey, S. Leevers, T. Ragan, P. Driscoll & A.P.G, submitted). Surprisingly, therefore, mNSCs are not the relevant Ilp source for neuroblast reactivation. Nonetheless, Ilp3 and Ilp6 mRNAs were detected in the CNS cortex, at the early L2 stage, in a domain distinct from the Ilp2+ mNSCs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Two different Ilp3-lacZ transgenes17 suggest that Ilp3 is expressed in some glia (Repo+ cells) and neurons (Elav+ cells). An Ilp6-GAL4 insertion (see Methods) suggests that Ilp6 is also expressed in glia, including the cortex glia surrounding neuroblasts and the surface glia of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. CNS-specific Ilps are sufficient for neuroblast reactivation.

a, Panels show expression of Ilp3-nLacZ in subsets of neurons (XD311-11) and glia (XD311-1) and Ilp6-GAL4 (Ilp6>nGFP and Ilp6>mGFP) in glia, including BBB surface and cortex glia. b,d EdU-labelled CNSs from larvae overexpressing Ilps in various cell types (see Methods for GAL4 drivers used). c, Histograms of normalized EdU+ voxels in the thoracic CNS for the genotypes in b. e, Ilp6 overexpression in the Ultrabithorax domain (Ubx>Ilp6) reactivates neuroblasts in the normal spatial pattern during NR (left panel). Quiescent/enlarging neuroblasts in the central brain, far from the posterior Ubx domain (middle panels), extend cytoplasmic processes (arrowheads) towards the neuropil, close to long Ubx+ cell processes (right panel). The range of Ilp6 activity is difficult to determine from this experiment. Neurons, glia and neuroblasts are marked by Elav, Repo and Miranda respectively.

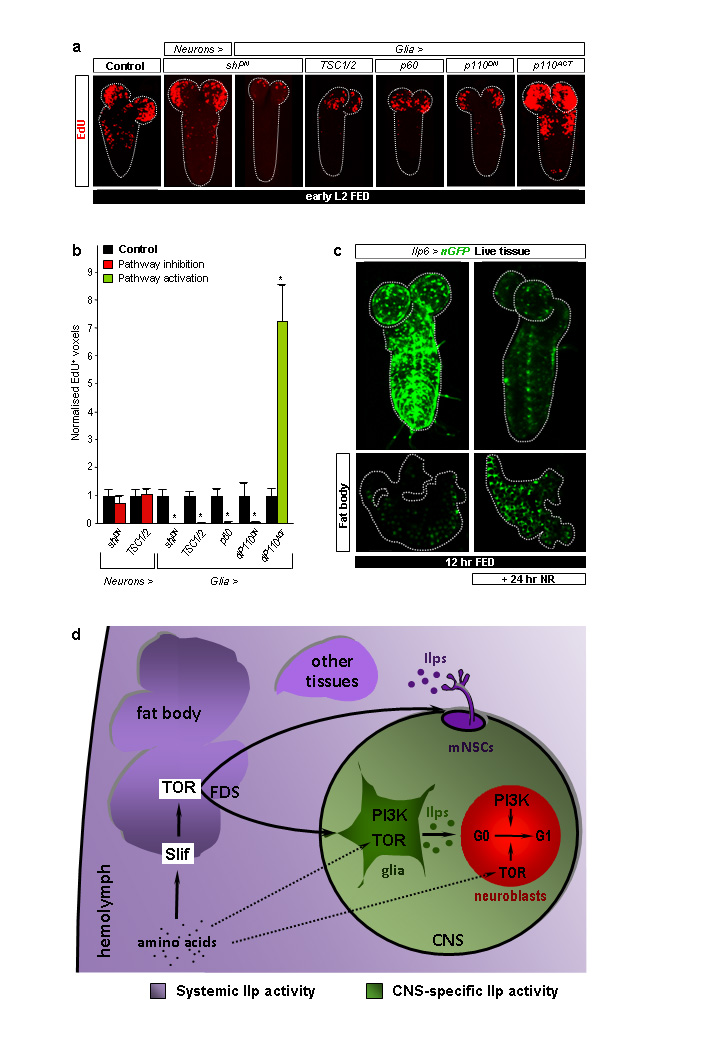

We next assessed the ability of each of the seven Ilps to reactivate neuroblasts when overexpressed in glia or in neurons (Supplementary Table 2). Pan-glial or pan-neuronal overexpression of Ilp4, Ilp5 or Ilp6 led to precocious reactivation under fed conditions (Fig. 3b,c). Each of these manipulations also bypassed the NR block to neuroblast reactivation, as did overexpression of Ilp2 in glia or in neurons, or Ilp3 in neurons (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 2). In all of these Ilp overexpressions, and even when Ilp6 was expressed in the posterior Ultrabithorax (Ubx) domain (Fig. 3e), the temporal rather than the spatial pattern of reactivation was affected. Importantly, experiments blocking cell signalling with ShiDN indicate that glia rather than neurons are critical for neuroblast reactivation (Fig. 4a,b). Interestingly, glial-specific overexpression of Ilps 3-6 did not significantly alter larval mass (Fig. 2c). Thus, in contrast to mNSC-derived Ilps, glial-derived Ilps promote CNS growth without affecting body growth.

Fig. 4. Ilp6-expressing glia are nutritionally regulated.

a, EdU-labelled CNSs from larvae expressing the components indicated. b, Histograms of normalized EdU+ voxels in the thoracic CNS for genotypes in a. c, Ilp6>nGFP expression in the CNS and fat body of fed versus NR larvae. d, Relay model for amino-acid dependent fat body regulation of CNS and body growth. CNS-restricted (green) and systemic (purple) pools of Insulin-like peptides (Ilps) are functionally segregated. Direct amino-acid sensing by glia and neuroblasts may contribute to neuroblast reactivation (dashed arrows). See text for details.

Focusing on Ilp6, we used CNS explant cultures to demonstrate directly that glial overexpression was sufficient to substitute for the FDS during neuroblast exit from quiescence (Fig. 3d). In vivo, Ilp6 was sufficient to induce reactivation during NR when overexpressed via its own promoter or specifically in cortex glia but not in the subperineurial BBB glia, nor in many other CNS cells that we tested (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 1). Hence, cortex glia possess the appropriate processing machinery and/or location to deliver reactivating Ilp6 to neuroblasts. Ilp6 mRNA is known to be up- rather than down-regulated in the larval fat body during starvation19 and, accordingly, Ilp6-GAL4 activity is increased in this tissue following NR (Fig. 4c). Conversely, we found that Ilp6-GAL4 is strongly downregulated in CNS glia during NR (Fig. 4c). Thus, dietary nutrients stimulate glia to express Ilp6 at the transcriptional level. Consistent with this, an important transducer of nutrient signals, the TOR/PI3K network, is necessary and sufficient in glia (but not in neurons) for neuroblast reactivation (Fig. 4a,b). Together, the genetic and expression analyses indicate that nutritionally regulated glia relay the FDS to quiescent neuroblasts via Ilps.

This study used an integrative physiology approach to identify the relay mechanism regulating a nutritional checkpoint in neural progenitors. A central feature of the fat body→glia→neuroblasts relay model is that glial Insulin signalling bridges the amino-acid/TOR-dependent FDS with InR/PI3K/TOR signalling in neuroblasts (Fig. 4d). The importance of glial Ilp signalling during neuroblast reactivation is also underscored by an independent study, published while this work was under revision27. As TOR signalling is also required in neuroblasts and glia, direct amino-acid sensing by these cell types may also impinge upon the linear tissue relay. This would then constitute a feed-forward persistence detector28, ensuring that neuroblasts exit quiescence only if high amino-acid levels are sustained rather than transient. We also showed that the CNS “compartment” in which glial Ilps promote growth is functionally isolated, perhaps by the blood-brain barrier, from the systemic compartment where mNSC Ilps regulate the growth of other tissues. The existence of two functionally separate Ilp pools may explain why bovine Insulin cannot reactivate neuroblasts in CNS organ culture14, despite being able to activate Drosophila InR in vitro29. Given that Insulin/PI3K/TOR signalling components are highly conserved between insects and vertebrates, it will be important to address whether mammalian adipose or hepatic tissues signal to glia and whether or not this involves an Insulin/IGF relay to CNS progenitors. In this regard, it is intriguing that brain-specific overexpression of IGF1 can stimulate cell-cycle re-entry of mammalian cortical neural progenitors30, suggesting utilization of at least part of the mechanism identified here in Drosophila.

METHODS SUMMARY

For GAL4/UAS experiments, animals were raised at 29 °C unless otherwise stated. Larvae hatching within a 2 hr window were transferred to cornmeal food (5.9% Glucose, 6.6% Cornmeal, 1.2% Baker's Yeast, 0.7% Agar in water) or NR medium (5% Sucrose, 1% Agar in PBS) and further synchronised by selecting L2 larvae morphologically from an L1/L2 moulting population. For EdU experiments, dissected CNSs were incubated for 1 hr in 10 μM EdU/PBS, fixed for 15 min in 4 % Formaldehyde/PBS and Alexa Fluor azide detected according to instructions (Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit, Invitrogen). CNS explants were cultured on 8μm pore-size inserts in Schneider's medium-10% fetal calf serum, 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco) and 1x Pen Strep (Gibco)- in 24-well Transwell plates (Costar) in a humidified chamber at 25 °C. For EdU quantifications, the “thoracic” region used corresponds to the ventral nerve cord from the level of the brain-lobes down to A1/A2 (Fig. 1a). EdU+ voxels were quantified using Volocity (Improvision) from an average of 10 CNSs per experimental genotype, normalized to controls processed in parallel (siblings or half-siblings), using Leica SP5 scans (LAS AF software) with a 1.5 μm-step z-series. For larval mass measurements, triplicates of ~50 wandering L3 male larvae per genotype were transferred to pre-weighed microfuge tubes and wet weights determined using a Precisa XB 120A balance. For all histograms, error bars represent the s.e.m. and p values are from two-tailed Student t-tests with equal sample variance. Further details can be found in full Methods section.

METHODS

Rearing and staging of Drosophila larvae

To assist larval genotyping, lethal chromosomes were re-established over Dfd-YFP balancers. For EdU experiments, crosses were performed in cages with grape-juice plates (25% (v/v) grape-juice, 1.25% (w/v) sucrose, 2.5% (w/v) agar) supplemented with live yeast paste. For GAL4/UAS experiments, larvae hatched within a 2 hr time-window were transferred to our standard cornmeal food (5.9% w/v Glucose, 6.6% Cornmeal, 1.2% Baker's Yeast, 0.7% Agar in water) or to NR medium (5% Sucrose, 1% Agar in PBS). Animals were raised at 29 °C throughout, with the following exceptions due to lethality at high temperature: tub-GAL80ts,Repo>shiDN and tub-GAL80ts,Repo>Ilp2 animals were raised at 25 °C during embryogenesis and 29 °C during larval development, other Ilp2 overexpressions were performed at 25 °C throughout. At the time of dissection, development was further synchronised by selecting L2 animals morphologically from a mixed L1/L2 moulting population. Df(3L)[Ilps2-3],Ilp5 and Df(3L)[Ilps1-5] animals develop considerably slower than controls, so EdU-incorporation experiments utilized morphological staging after the L1/L2 and L2/L3 moults. Co-expression of Dcr-2 was used to enhance knockdown efficiency for the SlifANTI antisense EP allele. As absolute numbers of reactivated neuroblasts can vary with small differences in temperature and humidity, parallel control experiments were carried out for each genetic background (using the siblings or half-siblings of experimental animals), rather than using a single control.

Drosophila strains

Stocks used in this study were: Tor2L19 (Ref. 31), InR31 (Ref. 32), Df(3L)[Ilps1-5], Df(X)[Ilp6] and Df(X)[Ilp7] (Ref. 33), Ilp11, Ilp21 Ilp31 Ilp41 Ilp51 Df(X)Ilp661, Df(X)Ilp668, Ilp71, Df(3L)[Ilps2-3], Df(3L)[Ilps2-3],Ilp53, Df(3L)[Ilps1-4],Ilp53 (Ref. 34), UAS-slifANTI (Ref. 35), UAS-TSC1/2 (Ref. 36), UAS-Rheb, UAS-InRDN = UAS-InRK1409A, UAS-InRACT = UAS-InRA1325D, FB driver = Cg-GAL4 (Ref. 37), pan-glial driver = Repo-GAL4 (Ref. 38), OK107-GAL4 (Ref. 39), eg-GAL4 (Ref. 40), DopR-GAL4 (Ref. 41), btl-GAL4 (Ref. 42), UAS-CD8::GFP, FRT82B, tub-GAL80ts, Sco/CyO,Dfd-YFP and Dr/TM6B,Sb,Dfd-YFP (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center), UAS-Dp110DN = UAS-Dp110A2860C and UAS-Dp110ACT = UAS Dp110CAAX (Ref. 43), UAS-PTEN (Ref. 44), UAS-p60 (Ref. 45), UAS-PDKACT = UAS-Pdk1A467V (Ref. 46), UAS-foxo.P (Ref. 47), UAS-Dcr2 (VDRC), UAS-Ilp7 (Ref. 48), UAS-Ilp1, UAS-Ilp2, UAS-Ilp3, UAS-Ilp4, UAS-Ilp5, UAS-Ilp6, Ilp3-nLacZpXD311-1 and Ilp3-nLacZpXD311-11 (both recapitulate endogenous Ilp3 expression in L3 mNSCs, Ref. 49), UAS-shiDN (Ref. 50), NB driver = nab-GAL4NP4604 (Ref. 51), cortex glia driver = NP577-GAL4 and ensheathing glia driver = NP6520-GAL4 (Ref. 52), Ilp6-GAL4 = NP1079-GAL4 (NIG stock centre), Subperineurial BBB glia driver = Moody-GAL4 (Ref. 53), midline glia driver = slit-GAL4 (Ref. 54), midline glia/neuronal driver = sim-GAL4 (Ref. 55), mNSC driver = Ilp2-GAL4 (Ref. 56), pan-neuronal driver = n-syb-GAL4 (Ref. 57), Ubx-GAL4 (Ref. 58), wg-GAL4 (Ref. 59), en-GAL4 was a gift from A. Brand via Jean-Paul Vincent, Repo-FLP (Ref. 60).

EdU detection, immunostaining, in situ hybridization and imaging

L1 and L2 tissues were immobilised on poly-L-Lysine-coated slides for all stainings, except for CNS explants. For EdU experiments, dissected CNSs were incubated for 1 hr in 10 μM EdU/PBS, fixed for 15 min in 4 % Formaldehyde/PBS, followed by detection of Alexa Fluor azide according to the manufacturer's instructions (Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit, Invitrogen) and washing in 0.1% Triton/PBS. Antibody staining and in situ hybridisation were performed according to standard protocols. Primary antibodies used in this study were: rabbit anti-β-Galactosidase (Molecular Probes) 1/2000; rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen) 1/1000; mouse anti-Repo 1/20; mouse anti-Miranda 1/20 and rat anti-Elav 1/100 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank); pre-adsorbed Alkaline Phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-Digoxigenin 1/2000. Secondary antibodies used were: F(ab′)2 fragments conjugated to either Alexa-Fluor-488, Alexa-Fluor-633 (Molecular Probes) or Cy3 (Jackson), used at 1/250-1/2000. Live tissues were photographed in PBS. Fixed tissues labeled for fluorescence microscopy were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) whereas those processed for in situ hybridisation were mounted in 80% Glycerol. Fluorescent images were acquired with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (LAS AF software) and bright-field images were acquired with a Zeiss Axiophot2 microsope (AxioVision software). Images of the whole CNS are projections of a 1.5 μm-step z-series. Images of fat body and of high-magnification double-labels of parts of the CNS are single sections except for the right panel of Fig. 3e, which is a projection of 13 sections from a z-series.

CNS Explant cultures

Explanted CNSs from larvae hatched within a 2hr window were cultured for 3-4 days on 8μm pore-size inserts in 10 μM EdU in Schneider's medium, 10% fetal calf serum, 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco) and 1x Pen Strep (Gibco), in 24-well Transwell plates (Costar) placed in a humidified chamber at 25 °C.

Quantification of EdU incorporation

The “thoracic” region used for EdU quantifications corresponds to the ventral nerve cord from brain-lobe level down to A1/A2, distinguishable from more posterior neuromeres by a sharp transition in neuroblast density (Fig. 1a). The numbers of EdU+ voxels per CNS were determined using Volocity (Improvision) from Leica SP5 confocal microscope scans (LAS AF software) using a 1.5 μm-step z-series. An average of 10 CNSs were quantified per experimental genotype and controls (siblings or half-siblings) were processed in parallel. Control and experimental values were normalized using the average number of control EdU+ voxels. For all histograms, error bars represent standard error of the mean (s.e.m) of normalised values and asterisks indicate p<0.05 using two-tailed Student t-tests with equal sample variance.

Larval mass measurements

Wet weights were determined for wandering L3 male larvae, sexed and genotyped in PBS, dabbed dry with tissue and transferred to pre-weighed microfuge tubes. For each data point, triplicate samples, each containing an average of 50 animals per genotype were weighed (Precisa XB 120A balance).

METHODS REFERENCES

- 31.Oldham S, et al. Genetic and biochemical characterization of dTOR, the Drosophila homolog of the target of rapamycin. Genes Dev. 2000;14(21):2689. doi: 10.1101/gad.845700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brogiolo W, et al. An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr Biol. 2001;11(4):213. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, et al. Deletion of Drosophila insulin-like peptides causes growth defects and metabolic abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(46):19617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905083106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gronke S, et al. Molecular evolution and functional characterization of Drosophila insulin-like peptides. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(2):e1000857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colombani J, et al. A nutrient sensor mechanism controls Drosophila growth. Cell. 2003;114(6):739. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tapon N, et al. The Drosophila tuberous sclerosis complex gene homologs restrict cell growth and cell proliferation. Cell. 2001;105(3):345. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hennig KM, Colombani J, Neufeld TP. TOR coordinates bulk and targeted endocytosis in the Drosophila melanogaster fat body to regulate cell growth. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(6):963. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong, et al. repo encodes a glial-specific homeo domain protein required in the Drosophila nervous system. Genes Dev. 1994;8:981. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Connolly, et al. Associative learning disrupted by impaired Gs signaling in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Science. 1996;274(5295):2104. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito K, Urban J, Technau GM. Distribution, classification, and development of Drosophila glial cells in the late embryonic and early larval ventral nerve cord. Rouxs Arch Dev Biol. 1995;204(5):284. doi: 10.1007/BF02179499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hacker U, et al. piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis in the presence of stably integrated P elements in Drosophila. PNAS. 2003;100(13):7720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230526100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiga Y, Tanaka-Matakatsu M, Hayashi S. A nuclear GFP/ beta-galactosidase fusion protein as a marker for morphogenesis in living Drosophila. Dev Growth Diff. 1996;38(1):99. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leevers SJ, et al. The Drosophila phosphoinositide 3-kinase Dp110 promotes cell growth. EMBO J. 1996;15(23):6584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang H, et al. PTEN affects cell size, cell proliferation and apoptosis during Drosophila eye development. Development. 1999;126(23):5365. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinkove D, et al. Regulation of imaginal disc cell size, cell number and organ size by Drosophila class I(A) phosphoinositide 3-kinase and its adaptor. Curr Biol. 1999;9(18):1019. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rintelen F, Stocker H, Thomas G, Hafen E. PDK1 regulates growth through Akt and S6K in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011318098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puig O, Marr MT, Ruhf ML, Tjian R. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 2003;17(16):2006. doi: 10.1101/gad.1098703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miguel-Aliaga I, Thor S, Gould AP. Postmitotic specification of Drosophila insulinergic neurons from pioneer neurons. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(3):e58. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeya T, et al. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12(15):1293. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moline MM, Southern C, Bejsovec A. Directionality of wingless protein transport influences epidermal patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1999;126(19):4375. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maurange C, Cheng L, Gould AP. Temporal transcription factors and their targets schedule the end of neural proliferation in Drosophila. Cell. 2008;133(5):891. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Awasaki T, Lai S-L, Ito K, Lee T. Organization and Postembryonic Development of Glial Cells in the Adult Central Brain of Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2008;28(51):13742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4844-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwabe T, et al. GPCR Signaling Is Required for Blood-Brain Barrier Formation in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;123(1):133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scholz H, Sadlowski E, Klaes A, Klambt C. Control of midline glia development in the embryonic Drosophila CNS. Mech Dev. 1997;64:137. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96:785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science. 2002;296(5570):1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pospisilik JA, et al. Drosophila genome-wide obesity screen reveals hedgehog as a determinant of brown versus white adipose cell fate. Cell. 2010;140(1):148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Navas LF, Garaulet DL, Sanchez-Herrero E. The ultrabithorax Hox gene of Drosophila controls haltere size by regulating the Dpp pathway. Development. 2006;133(22):4495. doi: 10.1242/dev.02609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pfeiffer S, Alexandre C, Calleja M, Vincent JP. The progeny of wingless-expressing cells deliver the signal at a distance in Drosophila embryos. Curr Biol. 2000;10(6):321. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silies M, Yuva Y, Engelen D, Aho A, Stork T, Klämbt C. Glial cell migration in the eye disc. J Neurosci. 2007;27(48):13130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3583-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Brand, Steve Cohen, Bruce Edgar, Ulrike Gaul, Ernst Hafen, Christian Klambt, Tzumin Lee, Sally Leevers, Pierre Leopold, Fumio Matsuzaki, Irene Miguel-Aliaga, Tom Neufeld, Ruth Palmer, Linda Partridge, Leslie Pick, Ernesto Sanchez-Herrero, Hugo Stocker, Nic Tapon, Tian Xu, and also to the Bloomington stock centre and Kyoto National Institute of Genetics (NIG) for fly stocks, antibodies and plasmids. We also acknowledge Iris Salecker, Jean-Paul Vincent, Andrew Bailey, Einat Cinnamon, Louise Cheng, Rami Makki, Ander Matheu, Panayotis Pachnis, Patricia Serpente and Irina Stefana for providing advice, reagents and critical reading of the manuscript. Authors were supported by the Medical Research Council (U117584237).

Footnotes

Author contributions

R.S.-N. and A.P.G. designed the experiments, R.S.-N and L.L.Y. performed the experiments and R.S.-N. and A.P.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and subscribe to the contents of the manuscript.

Competing Interest Statement: the authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dhawan J, Rando TA. Stem cells in postnatal myogenesis: molecular mechanisms of satellite cell quiescence, activation and replenishment. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:666–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coller HA. What's taking so long? S-phase entry from quiescence versus proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:667–70. doi: 10.1038/nrm2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanagida M. Cellular quiescence: are controlling genes conserved? Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen E, Finkel T. Preview. The Tortoise, the hare, and the FoxO. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:451–2. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez-Garcia I, Vicente-Duenas C, Cobaleda C. The theoretical basis of cancer-stem-cell-based therapeutics of cancer: can it be put into practice? Bioessays. 2007;29:1269–80. doi: 10.1002/bies.20679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betschinger J, Knoblich JA. Dare to be different: asymmetric cell division in Drosophila, C. elegans and vertebrates. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R674–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger B, Chell JM, Brand AH. Insights into neural stem cell biology from flies. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:39–56. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doe CQ. Neural stem cells: balancing self-renewal with differentiation. Development. 2008;135:1575–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sousa-Nunes R, Cheng LY, Gould AP. Regulating neural proliferation in the Drosophila CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:50–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truman JW, Bate M. Spatial and temporal patterns of neurogenesis in the central nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1988;125:145–57. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuji T, Hasegawa E, Isshiki T. Neuroblast entry into quiescence is regulated intrinsically by the combined action of spatial Hox proteins and temporal identity factors. Development. 2008;135:3859–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.025189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kambadur R, et al. Regulation of POU genes by castor and hunchback establishes layered compartments in the Drosophila CNS. Genes Dev. 1998;12:246–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isshiki T, Pearson B, Holbrook S, Doe CQ. Drosophila neuroblasts sequentially express transcription factors which specify the temporal identity of their neuronal progeny. Cell. 2001;106:511–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Britton JS, Edgar BA. Environmental control of the cell cycle in Drosophila: nutrition activates mitotic and endoreplicative cells by distinct mechanisms. Development. 1998;125:2149–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colombani J, et al. A nutrient sensor mechanism controls Drosophila growth. Cell. 2003;114:739–49. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brogiolo W, et al. An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr Biol. 2001;11:213–21. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeya T, Galic M, Belawat P, Nairz K, Hafen E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science. 2002;296:1118–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slaidina M, Delanoue R, Gronke S, Partridge L, Leopold P. A Drosophila insulin-like peptide promotes growth during nonfeeding states. Dev Cell. 2009;17:874–84. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto N, et al. A fat body-derived IGF-like peptide regulates postfeeding growth in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2009;17:885–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geminard C, Rulifson EJ, Leopold P. Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2009;10:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polak P, Hall MN. mTOR and the control of whole body metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neufeld TP. Body building: regulation of shape and size by PI3K/TOR signaling during development. Mech Dev. 2003;120:1283–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teleman AA. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila. Biochem J. 2010;425:13–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gronke S, Clarke DF, Broughton S, Andrews TD, Partridge L. Molecular evolution and functional characterization of Drosophila insulin-like peptides. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, et al. Deletion of Drosophila insulin-like peptides causes growth defects and metabolic abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905083106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chell JM, Brand AH. Nutrition-responsive glia control exit of neural stem cells from quiescence. Cell. 2010;143:1161–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangan S, Alon U. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11980–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Almonacid R, Rosen OM. Structure and ligand specificity of the Drosophila melanogaster insulin receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2718–27. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodge RD, D'Ercole AJ, O'Kusky JR. Insulin-like growth factor-I accelerates the cell cycle by decreasing G1 phase length and increases cell cycle reentry in the embryonic cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10201–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3246-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.