Abstract

Recent studies have highlighted the histone H3K4 methylation (H3K4me)-dependent transcriptional repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae; however, the underlying mechanism remains inexplicit. Here, we report that H3K4me inhibits the basal PHO5 transcription under high-phosphate conditions by suppressing nucleosome disassembly at the promoter. We found that derepression of the PHO5 promoter by SET1 deletion resulted in a labile chromatin structure, allowing more binding of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) but not the transactivators Pho2 and Pho4. We further showed that Pho23 and Cti6, two plant homeodomain (PHD)-containing proteins, cooperatively anchored the large Rpd3 (Rpd3L) complex to the H3K4-methylated PHO5 promoter. The deacetylation activity of Rpd3 on histone H3 was required for the function of Set1 at the PHO5 promoter. Taken together, our data suggest that Set1-mediated H3K4me suppresses nucleosome remodeling at the PHO5 promoter so as to reduce basal transcription of PHO5 under repressive conditions. We propose that the restriction of aberrant nucleosome remodeling contributes to strict control of gene transcription by the transactivators.

INTRODUCTION

Chromatin, the physiological template of all eukaryotic genetic information, is made up of repeating nucleosomes, each of which consists of 147-bp DNA wrapping around a histone octamer, including two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (30). In the process of gene transcription, chromatin structure can be modulated at several levels, such as ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling (11), histone modifications (36), and nucleosome disassembly and reassembly (42). Over the past decade, cross talks between different chromatin modifications have been reported, although the blueprint for this network is still elusive (61).

Cumulative studies have demonstrated that nucleosome disassembly at gene promoters is a general characteristic of gene activation in eukaryotes (9, 35, 51, 53). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PHO5 gene is one of the best understood examples for nucleosome dynamics (1, 4, 5). The PHO5 gene encodes an acid phosphatase that mediates periplasmic phosphate hydrolysis. The expression of PHO5 is stringently controlled by intracellular Pi concentration. Under high-phosphate (Pi+) conditions, the sequence-specific activator Pho4 is retained in the cytoplasm, preventing activation of PHO5 (45). Under phosphate depletion (Pi−) conditions, Pho4 becomes localized to the nucleus, where it interacts with another activator, Pho2, and together they bind the PHO5 promoter (6, 45). Correspondingly, under Pi+ conditions, four positioned nucleosomes, including UASp2 and the TATA box, reside over the PHO5 promoter containing the Pho4 binding site (62). After the switch to Pi− conditions, the four positioned nucleosomes are gradually disassembled from the PHO5 promoter (1, 9, 51). Disassembly of the PHO5 promoter nucleosomes is dispensable for the partial recruitment of activators but is indispensable for the recruitment of general transcriptional machinery and coactivators (1, 3, 18, 66).

Rpd3 is one of the major histone deacetylases in yeast and regulates the expression of a large number of genes (70). Two known Rpd3 complexes share a core of three subunits, i.e., Rpd3, Sin3, and Ume1 (14, 26, 27, 34, 40, 49, 71). The small Rpd3 (Rpd3S) complex is targeted primarily to the transcribed region and has been found to suppress spurious intragenic transcription during elongation and is implicated in controlling promoter fidelity (24, 27, 47), while the large Rpd3 (Rpd3L) complex occupies mainly gene promoters and functions to regulate transcription initiation (54, 55). The chromatin association of the Rpd3S complex requires Set2-dependent H3K36 methylation (H3K36me) simultaneously recognized by two of its subunits, the Chromo domain-containing protein Eaf3 and the plant homeodomain (PHD)-containing protein Rco1 (37). Interestingly, there are two PHD-containing subunits in the Rpd3L complex, Pho23 and Cti6, both of which specifically recognize methylated H3K4 peptide in vitro (55, 56). However, it is still unclear whether or how Pho23 and Cti6 direct the Rpd3L complex to chromatin in vivo.

Histone H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), catalyzed by Set1, is associated predominantly with actively transcribed genes (32, 43). Nevertheless, a number of studies have highlighted the repressive role of histone H3K4 methylation in gene transcription, such as for PHO5 and GAL1 (15, 47), although the mechanism remains elusive. In this study, using the yeast PHO5 gene as a model, we elucidated the molecular mechanism by which Set1-mediated H3K4me represses gene expression. We found that histone H3K4 was hypermethylated at the PHO5 promoter independent of the activation state. Elimination of H3K4me did not affect the recruitment kinetics of Pho2 and Pho4 but led to a relatively open chromatin structure of the PHO5 promoter, suggesting that Set1-mediated H3K4me inhibits PHO5 transcription by a chromatin-based mechanism. We also showed that the Rpd3L complex was targeted to the PHO5 promoter by H3K4 di- and trimethylation (H3K4me2/3) and mediated the function of Set1. Although Rpd3 deacetylated both H3 and H4 at the PHO5 promoter, Set1 specifically affected H3 deacetylation. Therefore, we conclude that the deacetylation activity on H3 is required for the regulation of PHO5 transcription by Set1-mediated H3K4me.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, growth conditions, and antibodies.

Most yeast strains originated from Euroscarf. Strains constructed in this work are shown in Table 1. The induction of PHO5 was achieved by immediately shifting yeast cells from high-phosphate medium (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD] plus 1 g/liter KH2PO4) to synthetic phosphate-free medium (yeast nitrogen base without phosphate was bought from MP Biomedicals). Histone modification antibodies were from Upstate. The histone H4 antibody was from Abcam. The anti-myc monoclonal antibody (clone 9E10) was from Sigma.

Table 1.

Yeast strains constructed in this work

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| JQW118 | BY4742 pho2Δ::KanMX set1Δ::URA3 |

| JQW119 | BY4742 pho4Δ::KanMX set1Δ::URA3 |

| JQW120 | BY4742 pho80Δ::KanMX set1Δ::URA3 |

| JQW121 | BY4742 rpd3Δ::KanMX set1Δ::URA3 |

| JQW122 | BY4742 pho23Δ::KanMX cti6Δ::URA3 |

| JQW123 | BY4742 PHO2-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW124 | BY4742 PHO4-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW126 | BY4742 SPT6-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW128 | BY4742 RPB3-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW129 | BY4742 RPD3-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW132 | BY4742 set1Δ::URA3 PHO2-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW133 | BY4742 set1Δ::URA3 PHO4-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW134 | BY4742 set1Δ::URA3 SPT6-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW135 | BY4742 set1Δ::URA3 RPB3-13MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW136 | BY4742 set1Δ::URA3 RPD3-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW137 | BY4742 cti6Δ::KanMX RPD3-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW138 | BY4742 pho23Δ::KanMX RPD3-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW139 | BY4742 pho23Δ::KanMX cti6Δ::URA3 RPD3-MYC::HIS3 |

| JQW142 | BY4742 pRS415[LEU2 GAL1-10 HHF1-HA HHT1] |

| JQW143 | BY4742 set1Δ::URA3 pRS415 [LEU2 GAL1-10 HHF1-HA HHT1] |

| JQW144 | BY4742 rpd3Δ::KanMX pRR608 [CEN LEU2 RPD3] |

| JQW145 | BY4742 rpd3Δ::KanMX pRR609 [CEN LEU2 rpd3(H150A)] |

| JQW146 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-289 his3Δ1Δ (hhf1-hht1) (hhf2-hht2) pNS329 [CEN TRP1 HHT1K4A-HHF1] |

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay.

Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 [vol/vol], 0.1% Na-deoxycholate [wt/vol], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], protease inhibitor cocktail). Cells were lysed using glass beads and sonicated to shear the chromatin to fragment sizes of approximately 200 to 500 bp. Cross-linked chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated with antibody for 4 h. Protein G/A-Sepharose beads were then added to the samples, and samples were incubated for an additional 2 h. The immunoprecipitated complexes were washed with lysis buffer, lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, wash buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40 [vol/vol], 0.1% Na-deoxycholate), and TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA). Next, the immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted from beads with elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS [wt/vol]). Formaldehyde cross-linking was reversed by incubating the eluates at 65°C overnight. DNA from the eluates was treated with 100 μg/ml proteinase K and purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Immunoprecipitated fractions (IP) and whole-cell extracts (Input) containing DNA were analyzed by real-time PCR. Primers used in real-time PCR were as follows: for TELVIR (subtelomeric region of chromosome VI-R), CCATAATGCCTCCTATATTTAGCCTTT/GACATATCCTTCACGAATATTGTTAGA; for PHO5 UASp2, GAATAGGCAATCTCTAAATGAATCGA/GAAAACAGGGACCAGAATCATAAATT; for the PHO5 5′ open reading frame (ORF), GTTTAAATCTGTTGTTTATTCA/CCAATCTTGTCGACATCGGCTA; for the PHO5 3′ ORF, CGGACCATACTACTCTTTCCCT/CCAGACTGACAGTAGGGTATCT; and for ACT1, TGTCCTTGTACTCTTCCGGT/CCGGCCAAATCGATTCTCAA.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Total RNA was isolated from cells grown to a concentration of approximately 1.0 × 107 cells/ml with an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using a Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase system and oligo(dT) (Promega). One microliter of the RT reaction was used in the subsequent real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (Eppendorf).

Immunofluorescence of yeast cells.

Immunostaining experiments were performed as previously described (72). Confocal microscopy was performed on a Leica TCS SP2 microscope with a 63× lambda blue oil objective. Image processing, including similar filtration and threshold levels, was standardized for all images.

Peptide pulldown assay.

Biotinylated histone tail peptides were prebound to streptavidin beads (Invitrogen) at a ratio of 2 μg of peptide to 30 μl bead slurry in peptide binding buffer (PBB) (20 mM Tris-Cl at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol [vol/vol], 0.05% Tween 20 [vol/vol], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, protease inhibitors). Beads were washed 3 times with PBB and blocked with 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA). Recombinant protein or yeast whole-cell extract was then added into the prebound bead slurry in equal volumes. Reaction samples were incubated for 1.5 h at 4°C and washed twice with PBB and twice with PBB containing 200 mM NaCl. Specific proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer prior to Western blot analysis.

Nuclease digestion of yeast chromatin.

Preparation and digestion of yeast nuclei were performed as described previously (4). DNA was prepared with phenol-chloroform extraction followed ethanol precipitation.

Southern blotting.

Yeast genomic DNAs were digested with restriction enzymes as indicated in Fig. 4A, separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham). The blot was hybridized with a [32P]dCTP incorporated probe as indicated in Fig. 4A. The radioactive signal was detected and quantitated by phosphorimager.

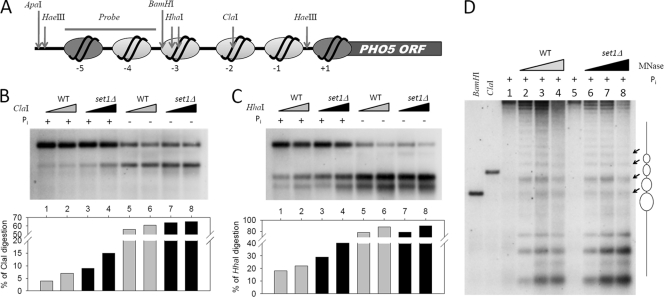

Fig. 4.

SET1 deletion leads to a more accessible chromatin structure at the PHO5 promoter. (A) Schematic of the recognition sites of the restriction enzymes used in nuclease assays and Southern blotting. (B and C) Restriction enzyme digestion of yeast nuclei. Nuclei were digested with 5 U or 50 U ClaI (B) or HhaI (C) for 120 min. To monitor the extent of cleavage, DNA was isolated, cleaved with HaeIII, separated by a 1.5% agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized with the probe indicated in panel A. Histograms represent the percentages of enzyme cleavage, quantified by phosphorimager. (D) MNase digestion of yeast nuclei. Nuclei were digested with increasing amounts of MNase for 15 min. Southern blotting was performed as described for panel B, except that the DNA was cleaved with ApaI. Black arrows denote sensitive sites representing the internucleosomal regions. Positioned nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter are represented (ovals) on the right.

Purification of recombinant proteins.

The glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused PHDs of Pho23 and Cti6 were overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified using glutathione Sepharose 4B medium (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

Histone H3K4 is hypermethylated at the PHO5 promoter irrespective of its activation state.

Since Set1-mediated H3K4me regulated PHO5 transcription (15), we first investigated how H3K4me associated with PHO5. We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), combined with real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR, in a time course experiment of PHO5 induction to detect the IP (% Input) of trimethylated H3K4 (H3K4me3) at the PHO5 promoter versus that at the subtelomeric region of chromosome VI-R (Fig. 1 A). The induction of PHO5 was achieved by immediately shifting yeast cells from high-phosphate (Pi+) to phosphate-free (Pi−) medium. The value of H3K4me3 was corrected by the histone occupancy. Consistent with a previous report (15), we found that the H3K4me3 marker was present at the repressed PHO5 promoter when cells were cultured in Pi+ medium. Unexpectedly, the level of H3K4me3 remained unchanged after Pi withdrawal (Fig. 1B). Therefore, H3K4me3 is not coupled with active gene transcription in the case of PHO5.

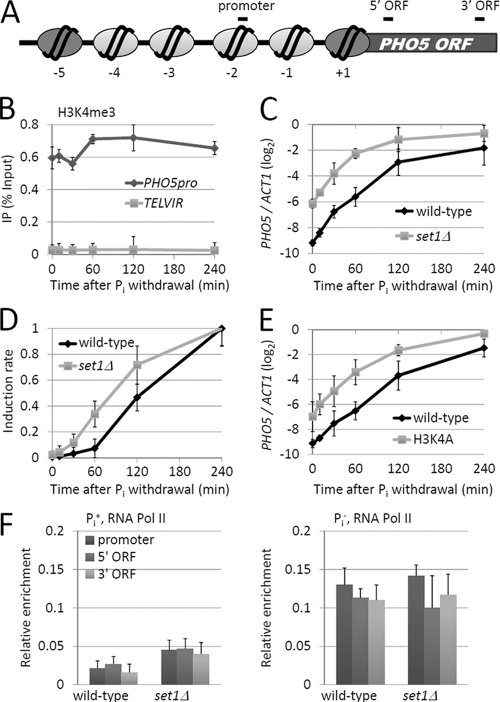

Fig. 1.

Set1-mediated H3K4 trimethylation associates with the PHO5 promoter and represses PHO5 transcription. (A) Schematic of the nucleosomal organization of the repressed promoter. The primer sets used for ChIP analysis are listed in the text. The light-gray ovals indicate nucleosomes that are removed during activation of PHO5, while the dark-gray ovals indicate nucleosomes that are not removed. (B) ChIP analysis of H3K4me3 at the promoter of PHO5. Yeast cells grown in Pi+ medium were shifted to phosphate-depleted medium, and the cells were harvested for ChIP at timed intervals. The H3K4me3 was corrected by histone H4 occupancy. The IP (% Input) at the PHO5 promoter and the subtelomeric region of chromosome VI-R are shown. (C and D) Analysis of PHO5 induction in wild-type and set1Δ cells. (C) Relative mRNA level of PHO5 at timed intervals after Pi withdrawal, normalized to ACT1. (D) The difference between the beginning and ending levels was set as 100%, and the values at the indicated times were determined. (E) Analysis of PHO5 induction in wild-type and H3K4A mutant cells. mRNA analysis was performed as described for panel C. (F) ChIP analysis of myc-tagged Rpb3 at PHO5. The corresponding regions of the PCR products are shown in panel A. Error bars represent standard errors of the means from three trials.

Elimination of H3K4me derepresses PHO5 transcription.

To investigate the effect of Set1 deletion on PHO5 induction, we performed qRT-PCR to measure the mRNA level of PHO5 at timed intervals upon Pi withdrawal. In the wild-type strain, PHO5 transcription was strongly repressed in Pi+ medium and was gradually increased upon the shift to Pi− medium. After a 240-min induction, the level of PHO5 mRNA was over 160-fold above the initial level (Fig. 1C). In the set1Δ strain, much more PHO5 mRNA was produced even under Pi+ conditions (Fig. 1C, 0 min). SET1 deletion also increased the induction rate of PHO5 (Fig. 1C and D) but had a minor effect on PHO5 transcription after growth under Pi− conditions for hours (Fig. 1C). An essentially identical result was also observed in an H3 lysine 4-to-alanine mutation strain (H3K4A strain), where H3K4 methylation by Set1 was prevented (Fig. 1E). Altogether, these data indicate that Set1-dependent H3K4me acts on PHO5 transcription both under Pi+ conditions and at early times after withdrawal of Pi.

We further investigated the effect of SET1 deletion on the action of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) at the PHO5 gene. The level of Rpb3, one of the key subunits of RNA Pol II (28), at the promoter, 5′ ORF, and 3′ ORF of PHO5 was measured in either Pi+ or Pi− medium. Consistent with the mRNA analysis results (Fig. 1C), the overall binding of Rpb3 at the PHO5 promoter in set1Δ cells was higher than that in wild-type cells (Fig. 1F). Notably, in both wild-type and set1Δ cells, Rpb3 was equally distributed at PHO5, exhibiting no 5′ or 3′ ORF bias, suggesting that Set1 does not affect the elongation efficiency of RNA Pol II.

Set1-mediated H3K4me does not affect the recruitment of Pho2 and Pho4 onto the PHO5 promoter.

Transcription of PHO5 is tightly controlled by the PHO gene regulatory cascade (Fig. 2 A). Pho2 and Pho4 are essential transactivators for PHO5 transcription. To determine whether the increase of PHO5 transcription in set1Δ cells depends on Pho2 and Pho4, we examined the PHO5 mRNA level under the wild-type, pho2Δ, or pho4Δ genetic background. Consistent with the general idea, no mRNA accumulation of PHO5 was detected in pho2Δ and pho4Δ cells (Fig. 2B). Although SET1 deletion elevated the PHO5 mRNA level under the wild-type background (Fig. 1C and 2B), it did not change the PHO5 mRNA level under the pho2Δ or pho4Δ background (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the function of H3K4me in PHO5 transcription requires the presence of the activators. Interestingly, neither PHO2 nor PHO4 deletion affected H3K4me at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 2C), indicating that the establishment of H3K4me at the PHO5 promoter does not require the activators.

Fig. 2.

Set1-mediated H3K4me does not affect the recruitment of Pho2 and Pho4 onto the PHO5 promoter. (A) Schematic of the regulatory circuit for phosphatase genes (46). (B) mRNA analysis of PHO5 in cells from different isogenic strains. Yeast cells were cultured in either Pi+ medium (top) or Pi− medium (bottom). (C) ChIP analysis of H3K4me3 at the PHO5 promoter. The conditions and the isogenic strains are indicated. ChIP experiments were performed as described for Fig. 1B. (D) Confocal images of the immunolocalization of myc-tagged Pho4 in wild-type and set1Δ cells. Pho4-myc was stained with mouse anti-Myc monoclonal antibody and detected with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. DNA is stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). (E and F) ChIP analysis of myc-tagged Pho4 and Pho2 level at the PHO5 promoter region in wild-type and set1Δ cells. Experiments were performed as described for Fig. 1B. Error bars represent standard errors of the means from three trials.

Further, we investigated the effect of SET1 deletion on PHO5 transcription when the activators constitutively bound the PHO5 promoter. We capitalized on the pho80Δ mutant, where Pho4 goes into the nucleus and constitutively activates PHO5 transcription (45). We found that the mRNA level of PHO5 in set1Δ pho80Δ cells was similar to that in pho80Δ cells (Fig. 2B), suggesting that H3K4me barely affects the PHO5 transcription when transactivators saturate the PHO5 promoter.

Since the function of Set1-mediated H3K4me in PHO5 transcription relied on the regulatory cascade, we then wondered whether H3K4 methylation influenced PHO5 transcription through affecting the recruitment of the activators. First, the cellular localizations of Pho4 were compared between wild-type and set1Δ cells. Under Pi+ conditions, the Pho4 staining was dispersed in wild-type cells, while after the depletion of Pi, the Pho4 activator was relocalized from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (45) (Fig. 2D, left). SET1 deletion did not affect the localization or the relocalization kinetics of Pho4 (Fig. 2D, right). Further, we compared the recruitments of Pho2 and Pho4 at the PHO5 promoter between wild-type and set1Δ cells. ChIP experiments were performed using anti-myc antibody to detect the binding of myc-tagged Pho2 or Pho4 at the PHO5 promoter during PHO5 induction. Upon Pi withdrawal, the abundance of both Pho2 and Pho4 at the PHO5 promoter was dramatically increased (Fig. 2E and F). Notably, the recruitment curves of Pho2 and Pho4 in set1Δ cells resembled those in wild-type cells (Fig. 2E and F), indicating that Set1-mediated H3K4me does not regulate the recruitment of the transactivators at the PHO5 promoter.

Lack of H3K4 methylation promotes nucleosome remodeling at the PHO5 promoter.

Nucleosome disruption at the PHO5 promoter, controlled by activator binding, is the key step before the loading and action of transcriptional machinery (1, 60). Since Set1-mediated H3K4me did not function through regulating activator recruitment, we hypothesized that H3K4me influences the chromatin structure of the PHO5 gene. To test this idea, we detected the histone occupancy at the promoter or ORF region of the PHO5 gene in wild-type and set1Δ cells (Fig. 1A). We used the commercially available version of anti-histone H4 antibody, which was used in a previous study establishing that nucleosomes lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter (51). As expected, nucleosome occupancy at the PHO5 promoter was high under Pi+ conditions (Fig. 3 A). After withdrawal of Pi, we observed a decrease (∼21% of original level at 240 min) in the H4 level at the promoter region of PHO5 (Fig. 3A, wild type). Strikingly, in set1Δ cells, the H4 level at the PHO5 promoter was only ∼65% of that in wild-type cells under Pi+ conditions (Fig. 3A, 0 min). SET1 deletion also accelerated the rate of nucleosome disassembly at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 3A and data not shown), However, at 240 min after withdrawal of Pi, the histone occupancy at the PHO5 promoter in set1Δ cells was comparable to that seen in wild-type cells (Fig. 3A). We also detected the histone occupancy at the 3′ ORF region of PHO5 and found that histone occupancy was not changed by Pi withdrawal in either wild-type or set1Δ cells (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data suggest that SET1 deletion reduces nucleosome occupancy of the PHO5 promoter.

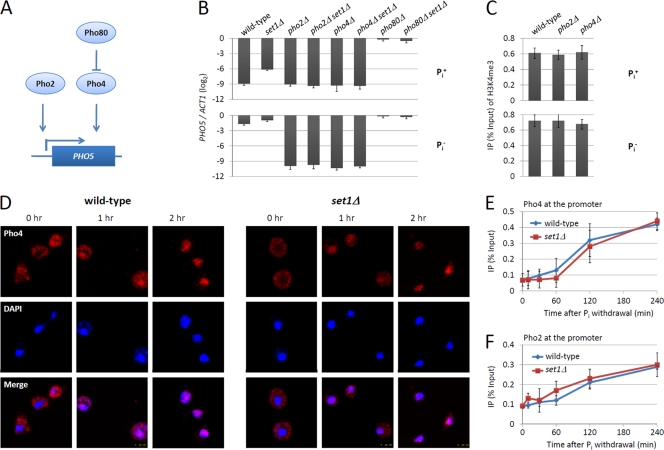

Fig. 3.

H3K4 methylation suppresses nucleosome remodeling at the PHO5 promoter. (A and B) ChIP analysis of histone H4 level at the promoter (A) and the 3′ ORF (B) of PHO5 in wild-type and set1Δ cells upon phosphate starvation. ChIP assays were performed as described for Fig. 1B. (C and D) ChIP analysis of myc-tagged Spt6 at the promoter (C) and the 3′ ORF (D) of PHO5 in wild-type and set1Δ cells upon phosphate starvation. ChIP assays were performed as described for Fig. 1B. (E) Schematic of the extrachromosomal copy of HHT1-HHF1 expressing H3 and HA-tagged H4 (H4-HA) under the control of the GAL1 promoter. (F) Schematic of the experimental procedures used to obtain results shown in panels G through I. (G to I) ChIP of H4-HA at the PHO5 promoter (G), the 3′ ORF (H), and the ACT1 ORF (I) after galactose induction and Pi withdrawal. Error bars represent standard errors of the means from three trials.

We next monitored binding of the histone chaperone Spt6, which is required for chromatin reassembly at PHO5 (2). Unexpectedly, more binding of Spt6 was detected at both the promoter and the 3′ ORF of PHO5 in set1Δ cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 3C and D), implying that SET1 deletion activates chromatin reassembly events at PHO5. To validate that chromatin reassembly events occurred in set1Δ cells, we constructed a strain into which an extra copy of HHT1-HHF1 was introduced. HHF1 was tagged with hemagglutinin (HA) epitope at its C terminus, and its promoter was replaced with a GAL1 promoter (Fig. 3E). The expression of H4-HA was induced by galactose 1 h before Pi withdrawal (Fig. 3F). By measuring the abundance of H4-HA at PHO5, we could monitor the nucleosome reassembly under Pi+ conditions and at early times after withdrawal of Pi. After long-term H4-HA expression (>2 h), chromatin in most cells was reassembled, and accordingly the abundance of H4-HA at PHO5 was reduced. The results showed that, in wild-type cells, the H4-HA was not incorporated into the PHO5 promoter throughout the process (Fig. 3G). In striking contrast, in set1Δ cells, H4-HA was incorporated into the PHO5 promoter right after galactose addition (Fig. 3G), supporting the idea that, under physiological conditions, H3K4me3 suppresses chromatin reassembly events at PHO5. In addition, we found that H4-HA was not detected at the 3′ORF of PHO5 in either wild-type or set1Δ cells (Fig. 3H). These results were expected because nucleosomes at the PHO5 ORF were well packaged even after PHO5 activation (Fig. 3B). At the control locus of ACT1, SET1 deletion did not affect nucleosome reassembly (Fig. 3I). Altogether, these data suggest that nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter in set1Δ cells are dynamically disassembled and reassembled even under Pi+ conditions.

Derepression of the PHO5 promoter by SET1 deletion leads to a relatively open chromatin structure.

To compare the chromatin structures of the PHO5 promoter between wild-type and set1Δ cells, we performed restriction endonuclease digestion experiments. As shown in the schematic in Fig. 4 A, the BamHI site falls within the linker regions between the positioned nucleosomes of the repressed promoter, whereas the ClaI and HhaI restriction enzymes have intranucleosomal sites located in the nucleosomes −2 and −3, respectively. Analyzing the accessibility of the ClaI and HhaI restriction sites at the PHO5 promoter is a reliable and quantitative way to access chromatin structure (5, 9). We isolated nuclei from wild-type and set1Δ strains grown in either Pi+ or Pi− medium, treated them with ClaI or HhaI, and then performed Southern blotting. Interestingly, in Pi+ medium, we observed a clear increase of restriction nuclease accessibility in set1Δ cells compared with that in wild-type cells (Fig. 4B and C). In Pi− medium, however, the restriction sites became equally accessible in wild-type and set1Δ strains (Fig. 4B and C). These data indicate that derepression of the PHO5 promoter by SET1 deletion increases the accessibility of nucleosomes −2 and −3.

We next performed micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion to address whether nucleosome positioning at the PHO5 promoter was changed in the set1Δ strain. Nuclei were isolated from strains in Pi+ medium and digested with MNase. Southern blotting showed that the overall chromatin organizations in wild-type and set1Δ cells were essentially the same (Fig. 4D). In addition, no detectable increase in MNase accessibility was detected in set1Δ cells (Fig. 4D). We reasoned that the modest increase of chromatin accessibility to DNA binding proteins detected by restriction endonuclease accessibility was not detectable by MNase accessibility.

The Rpd3L complex is recruited by Set1-mediated H3K4me and represses PHO5 transcription.

It has been shown that the Rpd3 complex represses PHO5 transcription and that the Rpd3S complex is involved in the Set1-mediated repression of GAL1 induction (15, 47). We proposed that Rpd3 was the effector of Set1-mediated H3K4me in the regulation of PHO5 transcription. To test this hypothesis, we first performed ChIP to investigate the dependence of Rpd3 binding at the PHO5 promoter on Set1. As a result, the Rpd3 binding level in set1Δ cells was only 13% of the wild-type level (Fig. 5 A), indicating that Set1 is required for Rpd3 recruitment at the PHO5 promoter. To validate that Rpd3 and Set1 functioned in the same genetic pathway, we compared the PHO5 mRNA levels during induction between rpd3Δ and rpd3Δ set1Δ strains. As shown in Fig. 5B, RPD3 deletion also increased the basal transcription of PHO5. Notably, the PHO5 induction curve in rpd3Δ set1Δ cells resembled that in rpd3Δ cells, suggesting that Rpd3 is responsible for the Set1-dependent transcriptional repression of PHO5.

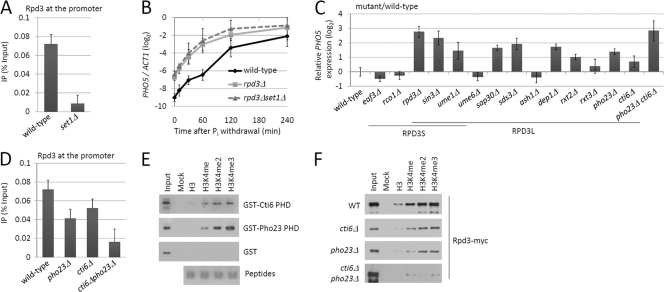

Fig. 5.

H3K4me recruits the Rpd3L complex for PHO5 repression. (A) ChIP analysis of myc-tagged Rpd3 at the PHO5 promoter in wild-type and set1Δ cells. Yeast cells were grown in Pi+ medium. (B) Analysis of PHO5 induction in wild-type, rpd3Δ, and rpd3Δ set1Δ cells. PHO5 mRNA was analyzed as described for Fig. 1C. (C) mRNA analysis of PHO5 in wild-type and Rpd3 complex mutant cells. Yeast was grown in Pi+ medium. The wild-type level of PHO5 was set as 1. The log2 values above 0 indicate increased transcription of PHO5. (D) ChIP analysis of myc-tagged Rpd3 at the PHO5 promoter in wild-type and mutant cells. ChIP was performed as described for panel A. Error bars represent standard errors of the means from three trials. (E) Pulldown assay of the PHD of either Cti6 or Pho23 with H3 N-terminal peptides. Agarose beads conjugated by peptides un-, mono-, di-, or trimethylated at H3K4 were incubated with equal amounts of recombinant proteins as indicated on the right. The peptide-bound proteins were detected by Western blotting with anti-GST antibody. “Mock” indicates a no-peptide control. Coomassie blue-stained peptides are shown at the bottom. (F) Pulldown assay of whole-cell extracts with H3 N-terminal peptides. The whole-cell extracts were derived from yeasts with the genetic backgrounds indicated on the left. The bound Rpd3-myc was detected with anti-myc antibody.

Rpd3 exists in two separate complexes: Rpd3S and Rpd3L (14, 26, 27, 34, 40, 49, 71). We wondered which complex participated in PHO5 transcriptional regulation. Therefore, we compared the PHO5 mRNA levels in Rpd3S and Rpd3L complex mutant strains with that in the wild-type strain. All strains were cultured in Pi+ medium. The relative PHO5 mRNA level of the wild-type strain was set as 1. The result showed that deletions of each of the shared subunits, RPD3, SIN3, and UME1, caused a dramatic increase in PHO5 transcription (Fig. 5C). Deletion of Rpd3S complex-specific genes EAF3 and RCO1 barely affected PHO5 transcription, while deletion of Rpd3L complex-specific genes, such as SAP30, SDS3, DEP1, RXT2, PHO23, and CTI6, increased PHO5 transcription (Fig. 5C). Therefore, we conclude that the Rpd3L complex participates in the regulation of PHO5 transcription.

Cooperative action of Pho23 and Cti6 mediates the binding of Rpd3 at the PHO5 promoter.

The binding of proteins with methylated H3K4 involves recognition of H3K4me by specific domains, such as the plant homeodomain (PHD) (55). Interestingly, there are two PHD-containing subunits, Pho23 and Cti6, in the Rpd3L complex, both of which recognize trimethylated H3K4 in vitro (55, 56). To investigate which subunit might be responsible for the Rpd3L complex recruitment to the methylated PHO5 promoter, we detected Rpd3 binding in wild-type, pho23Δ, and cti6Δ strains. The ChIP results showed that mutation of either PHO23 or CTI6 caused a modest decrease in Rpd3 binding at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 5D), suggesting that both subunits contribute to the recruitment of the Rpd3L complex to the PHO5 promoter. Notably, when we deleted both PHO23 and CTI6, the binding of Rpd3 at PHO5 was dramatically reduced (Fig. 5D), suggesting a synthetic effect of the two PHD-containing proteins on the Rpd3L complex association with the H3K4-methylated PHO5 promoter. Consistently, double deletion of PHO23 and CTI6 led to a higher mRNA level of PHO5 than single deletion did (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these data suggest that Pho23 and Cti6 cooperatively mediate the association and function of the Rpd3L complex on the PHO5 gene.

To directly assess the roles of Pho23 and Cti6 in the Rpd3L complex recognizing H3K4me, in vitro binding assays with biotinylated histone peptides were employed. First, we examined the binding affinity of the PHDs of Pho23 and Cti6 with unmodified or K4-monomethylated, -dimethylated, or -trimethylated histone H3 peptides (amino acids 1 to 27). The GST-fused recombinant PHDs were overexpressed in bacteria and purified to homogeneity (data not shown). Then, equal amounts of the recombinant proteins were incubated with peptide-conjugated agarose beads. The peptide-bound proteins were washed several times and subjected to Western blotting with anti-GST antibody. The results showed that both PHDs bound most strongly to H3K4me3 peptide, less to H3K4me2 peptide, even less to H3K4me1 peptide, and not at all to unmodified peptides (Fig. 5E), supporting the conclusion that Pho23 and Cti6 directly recognize hypermethylated H3K4. Then, we tagged Rpd3 with myc epitope in wild-type, cti6Δ, pho23Δ, and cti6Δ pho23Δ cells and examined the binding affinity of Rpd3-myc with the H3 peptides. As expected, the myc-tagged Rpd3 had a higher affinity to hypermethylated H3K4 peptides in the wild-type strain than in the mutant strains (Fig. 5F). Surprisingly, single mutation of either PHO23 or CTI6 did not affect the preference, while double deletion of PHO23 and CTI6 almost eliminated the binding of Rpd3 with methylated H3K4 (Fig. 5F). Taken together, these data support the conclusion that Pho23 and Cti6 cooperatively recruit the Rpd3L complex to H3K4-methylated chromatin.

The deacetylation activity of Rpd3 is essential for Set1-dependent suppression of nucleosome remodeling at the PHO5 promoter.

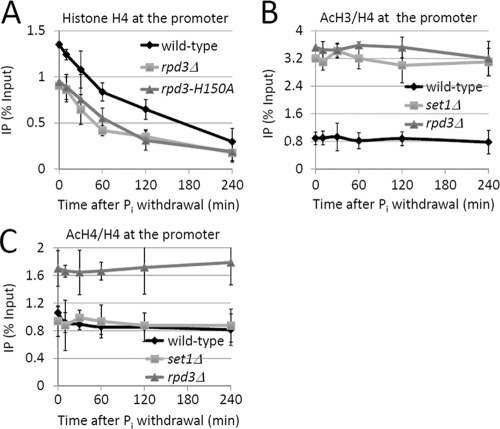

We then asked whether the deacetylation activity of Rpd3 was involved in the regulation of nucleosome remodeling by Set1. To this end, we inactivated the histone deacetylation activity of Rpd3 by mutating the histidine at amino acid 150 to alanine (25) and examined the effect on PHO5 promoter structure. The ChIP results showed that the initial nucleosome occupancy in the rpd3(H150A) mutant strain was only 68% of the wild-type level, which was similar to that in the rpd3Δ strain and the set1Δ strain (Fig. 6A and 3A). Thus, histone deacetylation by Rpd3 mostly likely mediates the Set1-dependent regulation of nucleosome disassembly.

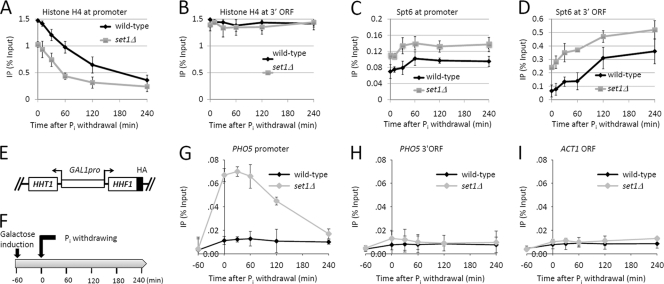

Fig. 6.

Set1 suppresses nucleosome disassembly by Rpd3-dependent H3 deacetylation. (A) ChIP analysis of histone H4 level at the promoter region of PHO5 in wild-type and rpd3 mutant cells upon phosphate starvation. ChIP assays were performed as described for Fig. 3A. (B and C) ChIP analysis of AcH3 (B) and AcH4 (C) at the promoter region of PHO5 in wild-type and mutant cells upon phosphate starvation. ChIP assays were performed as described for Fig. 1B. The IP (% Input) values of histone acetylation were then corrected by histone H4 density. Error bars represent standard errors of the means from three trials.

Set1-mediated H3K4 methylation specifically inhibits histone H3 acetylation at the PHO5 promoter.

According to the literature, the major substrates of Rpd3 on nucleosomes are the lysine residues at the N termini of histones H3 and H4 (13). To investigate how Set1 and Rpd3 affected the acetylation status of the PHO5 promoter, we used anti-acetyl-H3K9/14 (α-AcH3) antibody and anti-acetyl-H4K5/8/12/16 (α-AcH4) antibody in ChIP experiments to analyze the relative histone acetylation levels at the promoter of PHO5. Although the ChIP signals for AcH3 and AcH4 decreased upon Pi withdrawal (data not shown), the relative acetylation levels, achieved by normalizing the acetylation signals to the H4 signal, were essentially stable during the induction process (Fig. 6B and C). Consistent with a previous report (52), in rpd3Δ cells, we observed a marked increase of both AcH3 and AcH4 levels (Fig. 6B and C). However, in set1Δ cells, we found that the AcH3 level was greatly elevated (Fig. 6B) while the AcH4 level was slightly reduced (Fig. 6C). Combined with the above-described ChIP results (Fig. 6A), these data suggest that Rpd3-mediated H3 deacetylation is responsible for the restriction of nucleosome remodeling by Set1-mediated H3K4me.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized the mechanism for Set1-dependent PHO5 transcriptional repression. We found that Set1 affected PHO5 transcription through regulating chromatin structure but not the recruitment of transactivators. Notably, in set1Δ cells, the four positioned nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter were dynamically disassembled and reassembled under Pi+ conditions. We further revealed the Rpd3L complex, rather than the Rpd3S complex, as the effector of H3K4me in inhibiting PHO5 transcription. The deacetylation activity of Rpd3 on histone H3 is essential for the transcriptional repression of PHO5. Given that H3 acetylation is required for nucleosome remodeling at the PHO gene promoter (23, 50), the erasure of H3 acetylation by Rpd3 suppressed nucleosome remodeling at the PHO5 promoter. Therefore, our data suggest that the Set1-mediated H3K4me sets a nucleosomal barrier for the basal transcription of PHO5 under repressed conditions.

Repressive role of H3K4me in gene transcription.

When analyzing H3K4me distribution patterns genome-wide, one notices that H3K4me2/3 are occasionally present at transcriptionally inactive genes (48). Clearly, then, an important issue to address is how these epigenetic marks occur at inactive loci and what their functional outcomes are. One possibility is that H3K4me2/3 originate from weak cryptic noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). Indeed, antisense RNAs were detected at PHO5 as well as the PHO84 gene (12, 65). Other supportive evidence came from studies of the GAL1-10 gene cluster. In glucose, the 3′ ORF of GAL10 was trimethylated at H3K4 and generated a long ncRNA that was reciprocal to the GAL1 gene (24). The generation of ncRNA required the Reb1 transcriptional factor, whose depletion led to a decrease of H3K4me3 at the GAL1-10 locus (47). However, in the case of the PHO5 gene, the establishment of H3K4me did not require ncRNAs (65).

Despite the general idea that Set1 is associated with active transcription (31, 57, 59), an increasing number of arguments suggest that Set1-mediated H3K4me2/3 are also involved in gene repression. It was shown that Set1 was required for silencing of Ty1 retrotransposons GAL1 and PHO84 (10, 15), subsequently found to be ncRNA mediated (8, 12, 24, 47). Recently, Morillon's team provided evidence that H3K4me2/3 recruit the Rpd3S complex to GAL1 as well as many other inducible genes that showed cryptic transcription (47, 69). Paradoxically, according to the proposed model, the Rpd3S complex preferentially recognizes Set2-mediated H3K36me3 at the 3′ end of actively transcribed genes and represses promoters hidden within the coding region (37–39). It is still elusive how the Rpd3S complex is associated with H3K4me at gene promoters. In the case of PHO5, the Rpd3S complex-specific subunits had no effect on the PHO5 mRNA level (Fig. 5C). In contrast, many Rpd3L complex-specific subunits negatively regulate PHO5 transcription (16, 33, 40) (Fig. 5C). Our observations that both the Pho23 and the Cti6 subunit cooperatively recruited Rpd3 enzyme to the H3K4-methylated PHO5 promoter (Fig. 5D to F) provide a conceivable explanation for how H3K4me and the Rpd3L complex interact to repress PHO5 transcription.

Regulation of chromatin remodeling at the PHO5 promoter by histone acetylation and deacetylation.

It is generally considered that neutralization of the positive charges on lysine residues in the histone tails by acetylation disrupts electrostatic interactions between the histones and the phosphate groups in the DNA, leading to a looser configuration (58, 64). The fundamental role of histone acetylation in disruption of the promoter nucleosome structure during PHO5 induction has been revealed (7, 22, 44, 50, 51, 68). Under repressed conditions, the NuA4 acetyltransferase complex, recruited by Pho2, maintains a hyperacetylated state of the nucleosomes so as to poise the promoter for chromatin remodeling (44). The SAGA complex is recruited to the PHO5 promoter upon induction and directly regulates the opening of the nucleosome structure (7, 17, 22). However, hyperacetylation of histone H3 is detected in the absence of Swi2 only when the remodeling process is frozen subsequent to activator binding (50). If remodeling is permitted to go to completion, hyperacetylation is lost (50, 51). Thus, we propose that in the process of PHO5 activation, the promoter nucleosomes acetylated at histone H3 are quickly removed during induction. The unremodeled nucleosomes restore their initial acetylation level, probably by Rpd3-dependent histone deacetylation. In set1Δ or rpd3Δ cells, we found that histone H3 was hyperacetylated and prone to be removed from the PHO5 promoter without induction (Fig. 6A and B). This looser nucleosome confirmation potentially increased the binding of chromatin remodelers and thereby further facilitated the chromatin remodeling process (Fig. 4 and 5). Therefore, our study suggests that histone hyperacetylation at both H3 and H4 tends to be removed from the PHO5 promoter.

Interestingly, both NuA4 and the Rpd3 complex are able to recognize H3K4me (41, 55, 56). In the case of PHO5, we found that H3K4me was critical for the recruitment of Rpd3 and contributed to the recruitment of NuA4 at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 5A and data not shown). These observations are consistent with the predicted model where both histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases are associated with inactive genes primed by H3K4 methylation (67). A previous study has indicated that Rpd3 can compete with NuA4 for chromatin binding by deacetylating and destabilizing the Yng2 subunit of NuA4 (38). Indeed, we observed an increase of Esa1 binding at the PHO5 promoter in rpd3Δ cells (data not shown). Therefore, elimination of H3K4me results in a reduced binding of Esa1 as well as Rpd3, the competitor of Esa1. This could explain the discrepancy between Set1 and Rpd3 in regulating H4 acetylation at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 6C). Altogether, our work reveals a complicated cross talk among histone methylation, acetylation, and deacetylation at the PHO5 promoter that orchestrates the chromatin structure.

Cross talk between the transcriptional activators and chromatin remodeling at the PHO5 gene.

The transcription of PHO5 is tightly controlled by the PHO gene regulatory cascade. The absence of transcriptional activator Pho2 or Pho4 from the PHO5 promoter causes a complete loss of PHO5 transcription (6, 45). Recruitment of transcriptional activators is required for remodeling of the four positioned nucleosomes at PHO5 (19–21, 63). Therefore, it is not surprising to find that the regulation of PHO5 transcription by Set1 also requires the presence of Pho2 and Pho4 (Fig. 2B). Since chromatin is completely unfolded at the active PHO5 promoter (9), Set1 no longer has an effect on the transcription of activated PHO5 (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, it has been shown that nucleosome disassembly from the PHO5 promoter is a prerequisite for action of the general transcription machinery, activators, and coactivators (1, 3, 18, 29). In our study, we found that SET1 deletion altered the chromatin structure at the PHO5 promoter (Fig. 2 and 3) but did not affect the recruitment of transactivators. We reason that the chromatin structure at the PHO5 promoter, although partially relaxed in set1Δ cells, is still restrictive to activator binding. Given the fact that the activators are already present at the PHO5 promoter even under repressed conditions (44) (Fig. 2E and F), the elimination of H3K4me at the PHO5 promoter may exaggerate the activity of activators in nucleosome remodeling.

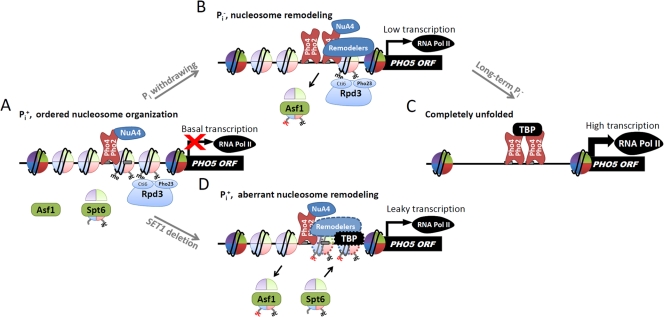

In summary, we have presented a Set1-dependent chromatin-based mechanism that prevents basal transcription of PHO5 under repressed conditions (Fig. 7). The nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter become more dynamic and more accessible to the transcription machinery even under repressive conditions when H3K4 is hypomethylated. We propose that the stringent regulation of PHO5 transcription is achieved not only by the regulatory cascade but also by the well-controlled chromatin structure at their promoters.

Fig. 7.

Predicted model for the regulation of nucleosome remodeling at the PHO5 promoter. (A) Under Pi+ conditions, the four nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter are well positioned, inaccessible to chromatin remodelers or coactivators. Histone H4 (shown as red sector) N-terminal lysines are acetylated by Pho2-recruited NuA4. H4 acetylation is required but not sufficient for initiation of promoter chromatin remodeling. Histone H3 (shown as blue sector) is hypermethylated at K4, which recruits the Rpd3L complex to maintain a hypoacetylated state of H3 lysines. At this stage, there is only basal PHO5 transcription. (B) Upon Pi withdrawal, histone modifiers and chromatin remodelers are targeted to the PHO5 promoter by the relocalized Pho4. Remodeling of the promoter nucleosomes requires acetylation of histone H3. Once acetylated, histone H3 is rapidly removed from the PHO5 promoter; otherwise, it will be deacetylated by the Rpd3L complex. Therefore, the relative acetylation level at the PHO5 promoter is essentially stable during the induction process. At this intermediate stage, the PHO5 transcript is being accumulated but still at a low level. (C) After growth in Pi− medium, nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter are completely unfolded, allowing efficient action of the transcriptional machinery. At this stage, Set1-mediated H3K4me is dispensable. (D) When SET1 is deleted, the promoter becomes partially accessible to chromatin remodelers even under Pi+ conditions. Loss of Rpd3 increases histone H3 acetylation and thereby elevates basal chromatin remodeling. The four nucleosomes are dynamically disassembled and reassembled (shown as dashed circles). Such a labile promoter structure results in high basal transcription of PHO5 even under repressed conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (90919027) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2011CB966300).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adkins M. W., Howar S. R., Tyler J. K. 2004. Chromatin disassembly mediated by the histone chaperone Asf1 is essential for transcriptional activation of the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 genes. Mol. Cell 14:657–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adkins M. W., Tyler J. K. 2006. Transcriptional activators are dispensable for transcription in the absence of Spt6-mediated chromatin reassembly of promoter regions. Mol. Cell 21:405–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adkins M. W., Williams S. K., Linger J., Tyler J. K. 2007. Chromatin disassembly from the PHO5 promoter is essential for the recruitment of the general transcription machinery and coactivators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:6372–6382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Almer A., Hörz W. 1986. Nuclease hypersensitive regions with adjacent positioned nucleosomes mark the gene boundaries of the PHO5/PHO3 locus in yeast. EMBO J. 5:2681–2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Almer A., Rudolph H., Hinnen A., Hörz W. 1986. Removal of positioned nucleosomes from the yeast PHO5 promoter upon PHO5 induction releases additional upstream activating DNA elements. EMBO J. 5:2689–2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barbaric S., Munsterkotter M., Svaren J., Hörz W. 1996. The homeodomain protein Pho2 and the basic-helix-loop-helix protein Pho4 bind DNA cooperatively at the yeast PHO5 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4479–4486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barbaric S., Reinke H., Hörz W. 2003. Multiple mechanistically distinct functions of SAGA at the PHO5 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3468–3476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berretta J., Pinskaya M., Morillon A. 2008. A cryptic unstable transcript mediates transcriptional trans-silencing of the Ty1 retrotransposon in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 22:615–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boeger H., Griesenbeck J., Strattan J. S., Kornberg R. D. 2003. Nucleosomes unfold completely at a transcriptionally active promoter. Mol. Cell 11:1587–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Briggs S. D., et al. 2001. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 15:3286–3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cairns B. R. 2005. Chromatin remodeling complexes: strength in diversity, precision through specialization. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camblong J., et al. 2009. Trans-acting antisense RNAs mediate transcriptional gene cosuppression in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 23:1534–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carmen A. A., Rundlett S. E., Grunstein M. 1996. HDA1 and HDA3 are components of a yeast histone deacetylase (HDA) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15837–15844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carrozza M. J., et al. 2005. Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123:581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carvin C. D., Kladde M. P. 2004. Effectors of lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are negative regulators of PHO5 and GAL1-10. J. Biol. Chem. 279:33057–33062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colina A. R., Young D. 2005. Raf60, a novel component of the Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex required for Rpd3 activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 280:42552–42556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dhasarathy A., Kladde M. P. 2005. Promoter occupancy is a major determinant of chromatin remodeling enzyme requirements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2698–2707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ertel F., et al. 2010. In vitro reconstitution of PHO5 promoter chromatin remodeling points to a role for activator-nucleosome competition in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:4060–4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fascher K. D., Schmitz J., Hörz W. 1990. Role of trans-activating proteins in the generation of active chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 9:2523–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fascher K. D., Schmitz J., Hörz W. 1993. Structural and functional requirements for the chromatin transition at the PHO5 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae upon PHO5 activation. J. Mol. Biol. 231:658–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gaudreau L., Schmid A., Blaschke D., Ptashne M., Hörz W. 1997. RNA polymerase II holoenzyme recruitment is sufficient to remodel chromatin at the yeast PHO5 promoter. Cell 89:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gregory P. D., et al. 1998. Absence of Gcn5 HAT activity defines a novel state in the opening of chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Mol. Cell 1:495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gregory P. D., Schmid A., Zavari M., Munsterkotter M., Hörz W. 1999. Chromatin remodelling at the PHO8 promoter requires SWI-SNF and SAGA at a step subsequent to activator binding. EMBO J. 18:6407–6414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Houseley J., Rubbi L., Grunstein M., Tollervey D., Vogelauer M. 2008. A ncRNA modulates histone modification and mRNA induction in the yeast GAL gene cluster. Mol. Cell 32:685–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kadosh D., Struhl K. 1998. Histone deacetylase activity of Rpd3 is important for transcriptional repression in vivo. Genes Dev. 12:797–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kasten M. M., Dorland S., Stillman D. J. 1997. A large protein complex containing the yeast Sin3p and Rpd3p transcriptional regulators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4852–4858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keogh M. C., et al. 2005. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 123:593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolodziej P., Young R. A. 1989. RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 is an essential component of the mRNA transcription apparatus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:5387–5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korber P., et al. 2006. The histone chaperone Asf1 increases the rate of histone eviction at the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 281:5539–5545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kornberg R. D. 1974. Chromatin structure: a repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science 184:868–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kouzarides T. 2007. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128:693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krogan N. J., et al. 2003. The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol. Cell 11:721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lau W. W., Schneider K. R., O'Shea E. K. 1998. A genetic study of signaling processes for repression of PHO5 transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150:1349–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lechner T., et al. 2000. Sds3 (suppressor of defective silencing 3) is an integral component of the yeast Sin3[middle dot]Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex and is required for histone deacetylase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40961–40966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee C. K., Shibata Y., Rao B., Strahl B. D., Lieb J. D. 2004. Evidence for nucleosome depletion at active regulatory regions genome-wide. Nat. Genet. 36:900–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li B., Carey M., Workman J. L. 2007. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128:707–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li B., et al. 2007. Combined action of PHD and chromo domains directs the Rpd3S HDAC to transcribed chromatin. Science 316:1050–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li B., et al. 2007. Infrequently transcribed long genes depend on the Set2/Rpd3S pathway for accurate transcription. Genes Dev. 21:1422–1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li B., et al. 2009. Histone H3 lysine 36 dimethylation (H3K36me2) is sufficient to recruit the Rpd3s histone deacetylase complex and to repress spurious transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 284:7970–7976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Loewith R., et al. 2001. Pho23 is associated with the Rpd3 histone deacetylase and is required for its normal function in regulation of gene expression and silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24068–24074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McManus K. J., Biron V. L., Heit R., Underhill D. A., Hendzel M. J. 2006. Dynamic changes in histone H3 lysine 9 methylations: identification of a mitosis-specific function for dynamic methylation in chromosome congression and segregation. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8888–8897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mellor J. 2006. Dynamic nucleosomes and gene transcription. Trends Genet. 22:320–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ng H. H., Robert F., Young R. A., Struhl K. 2003. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell 11:709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nourani A., Utley R. T., Allard S., Côté J. 2004. Recruitment of the NuA4 complex poises the PHO5 promoter for chromatin remodeling and activation. EMBO J. 23:2597–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Neill E. M., Kaffman A., Jolly E. R., O'Shea E. K. 1996. Regulation of PHO4 nuclear localization by the PHO80-PHO85 cyclin-CDK complex. Science 271:209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oshima Y., Ogawa N., Harashima S. 1996. Regulation of phosphatase synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae—a review. Gene 179:171–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pinskaya M., Gourvennec S., Morillon A. 2009. H3 lysine 4 di- and tri-methylation deposited by cryptic transcription attenuates promoter activation. EMBO J. 28:1697–1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pokholok D. K., et al. 2005. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell 122:517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Puig S., Lau M., Thiele D. J. 2004. Cti6 is an Rpd3-Sin3 histone deacetylase-associated protein required for growth under iron-limiting conditions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:30298–30306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reinke H., Gregory P. D., Hörz W. 2001. A transient histone hyperacetylation signal marks nucleosomes for remodeling at the PHO8 promoter in vivo. Mol. Cell 7:529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reinke H., Hörz W. 2003. Histones are first hyperacetylated and then lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter. Mol. Cell 11:1599–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schultz J. 1936. Variegation in Drosophila and the inert chromosome regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 22:27–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schwabish M. A., Struhl K. 2004. Evidence for eviction and rapid deposition of histones upon transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10111–10117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sharma V. M., Tomar R. S., Dempsey A. E., Reese J. C. 2007. Histone deacetylases RPD3 and HOS2 regulate the transcriptional activation of DNA damage-inducible genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:3199–3210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shi X., et al. 2006. ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature 442:96–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shi X., et al. 2007. Proteome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies several PHD fingers as novel direct and selective binding modules of histone H3 methylated at either lysine 4 or lysine 36. J. Biol. Chem. 282:2450–2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shilatifard A. 2006. Chromatin modifications by methylation and ubiquitination: implications in the regulation of gene expression. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:243–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shogren-Knaak M., et al. 2006. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science 311:844–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sims R. J., III, Reinberg D. 2006. Histone H3 Lys 4 methylation: caught in a bind? Genes Dev. 20:2779–2786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Straka C., Hörz W. 1991. A functional role for nucleosomes in the repression of a yeast promoter. EMBO J. 10:361–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suganuma T., Workman J. L. 2008. Crosstalk among histone modifications. Cell 135:604–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Svaren J., Hörz W. 1995. Interplay between nucleosomes and transcription factors at the yeast PHO5 promoter. Semin. Cell Biol. 6:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Svaren J., Schmitz J., Hörz W. 1994. The transactivation domain of Pho4 is required for nucleosome disruption at the PHO5 promoter. EMBO J. 13:4856–4862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Szerlong H. J., Prenni J. E., Nyborg J. K., Hansen J. C. 2010. Activator-dependent p300 acetylation of chromatin in vitro: enhancement of transcription by disruption of repressive nucleosome-nucleosome interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 285:31954–31964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Uhler J. P., Hertel C., Svejstrup J. Q. 2007. A role for noncoding transcription in activation of the yeast PHO5 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:8011–8016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Venter U., Svaren J., Schmitz J., Schmid A., Hörz W. 1994. A nucleosome precludes binding of the transcription factor Pho4 in vivo to a critical target site in the PHO5 promoter. EMBO J. 13:4848–4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wang Z., et al. 2009. Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes. Cell 138:1019–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Williams S. K., Truong D., Tyler J. K. 2008. Acetylation in the globular core of histone H3 on lysine-56 promotes chromatin disassembly during transcriptional activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9000–9005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Xu Z., et al. 2009. Bidirectional promoters generate pervasive transcription in yeast. Nature 457:1033–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yang X. J., Seto E. 2008. The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: from bacteria and yeast to mice and men. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:206–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang Y., et al. 1998. SAP30, a novel protein conserved between human and yeast, is a component of a histone deacetylase complex. Mol. Cell 1:1021–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhou J., Zhou B. O., Lenzmeier B. A., Zhou J. Q. 2009. Histone deacetylase Rpd3 antagonizes Sir2-dependent silent chromatin propagation. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:3699–3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]